Cognitive Load Theory: A teacher's guide

Discover how Cognitive Load Theory can transform your teaching by managing working memory, using worked examples, and applying proven strategies to boost student learning outcomes.

Discover how Cognitive Load Theory can transform your teaching by managing working memory, using worked examples, and applying proven strategies to boost student learning outcomes.

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), developed by educational psychologist John Sweller in the late 1980s, explains how the architecture of human memory affects learning. The theory has become one of the most influential frameworks in education, providing practical guidance for instructional design and forming a cornerstone of cognitive learning theory.

The central insight of CLT is that working memory, where conscious processing occurs, has strict capacity limits. We can only hold and manipulate approximately four to seven new items simultaneously. When instructional materials demand more processing than working memory can handle, learning fails regardless of student motivation or ability. However, information stored in long-term memory through schema construction can be processed as single units, effectively expanding working memory capacity. Developing cognitive skills and metacognitive awareness of cognitive load helps students recognise when they're approaching these li mits.

teacher's guide" loading="lazy">

teacher's guide" loading="lazy">Long-term memory, by contrast, has essentially unlimited capacity. Information stored in long-term memory can be retrieved into working memory as schemas, organised knowledge structures that help us process new information efficiently. This connects to schema theory, which explains how mental frameworks shape learning. Well-developed schemas allow experts to process complex information as single units, bypassing the processing limits that constrain new information. Effective teaching helps students build schemas that transfer knowledge from fragile working memory to durable long-term memory.

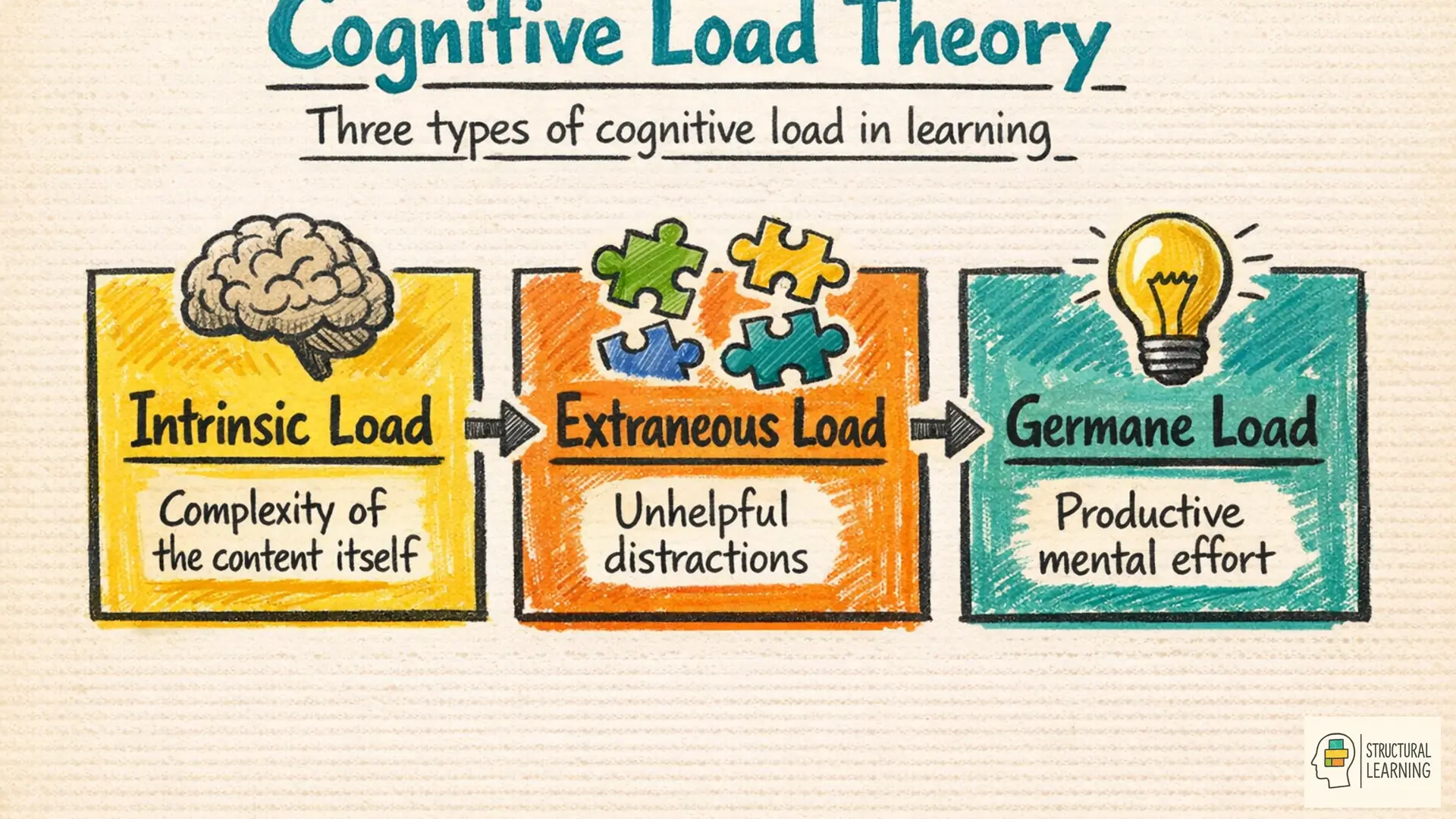

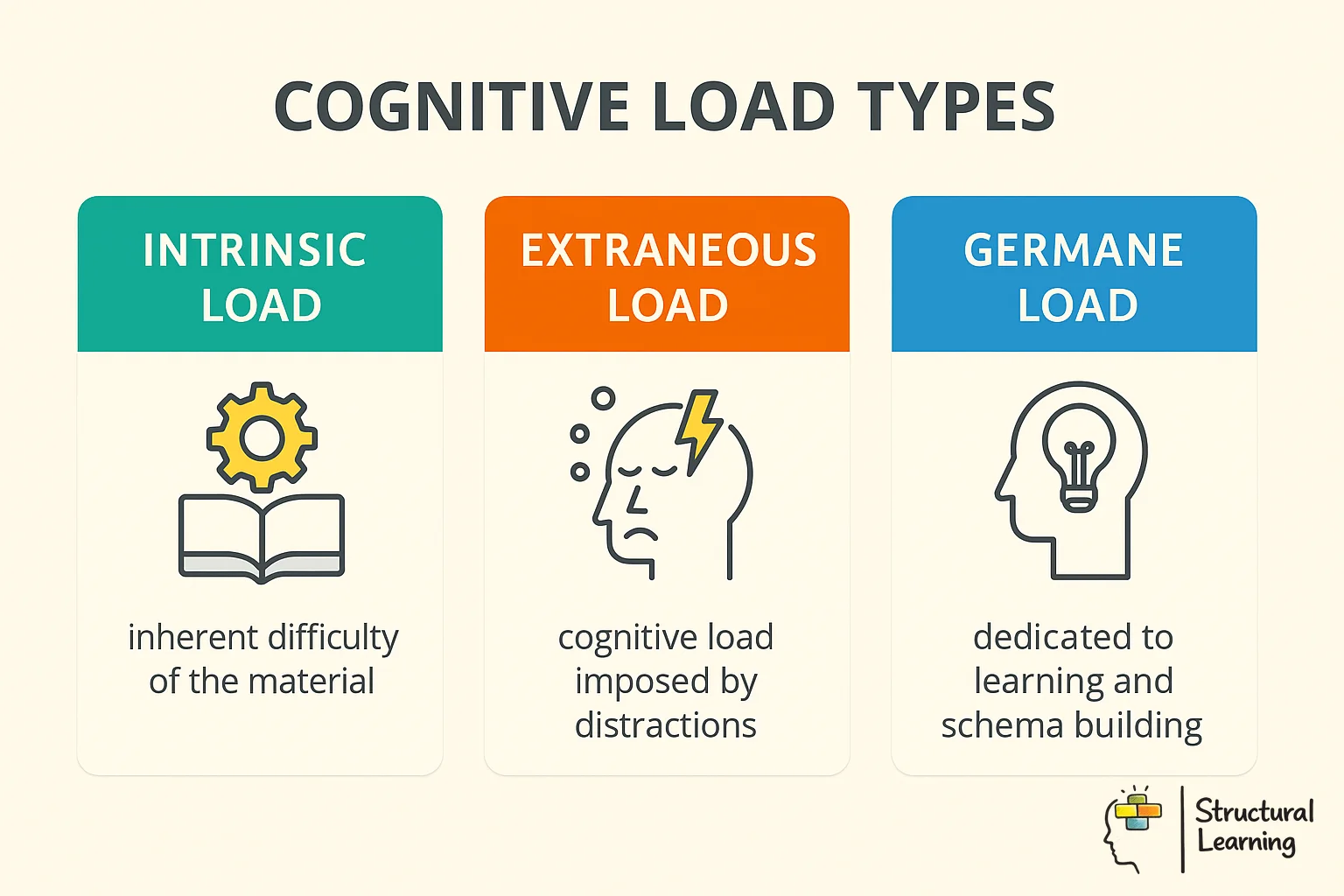

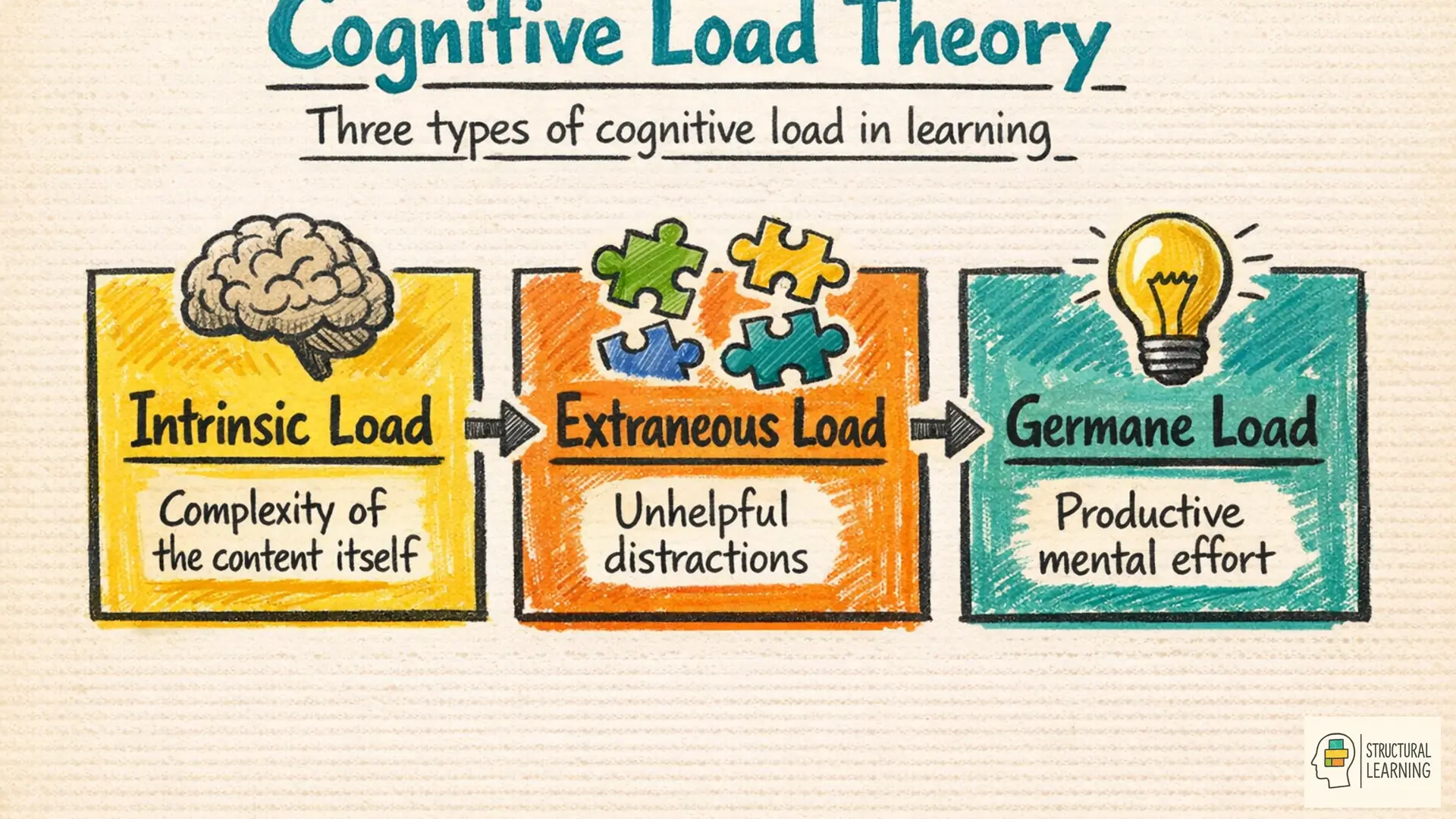

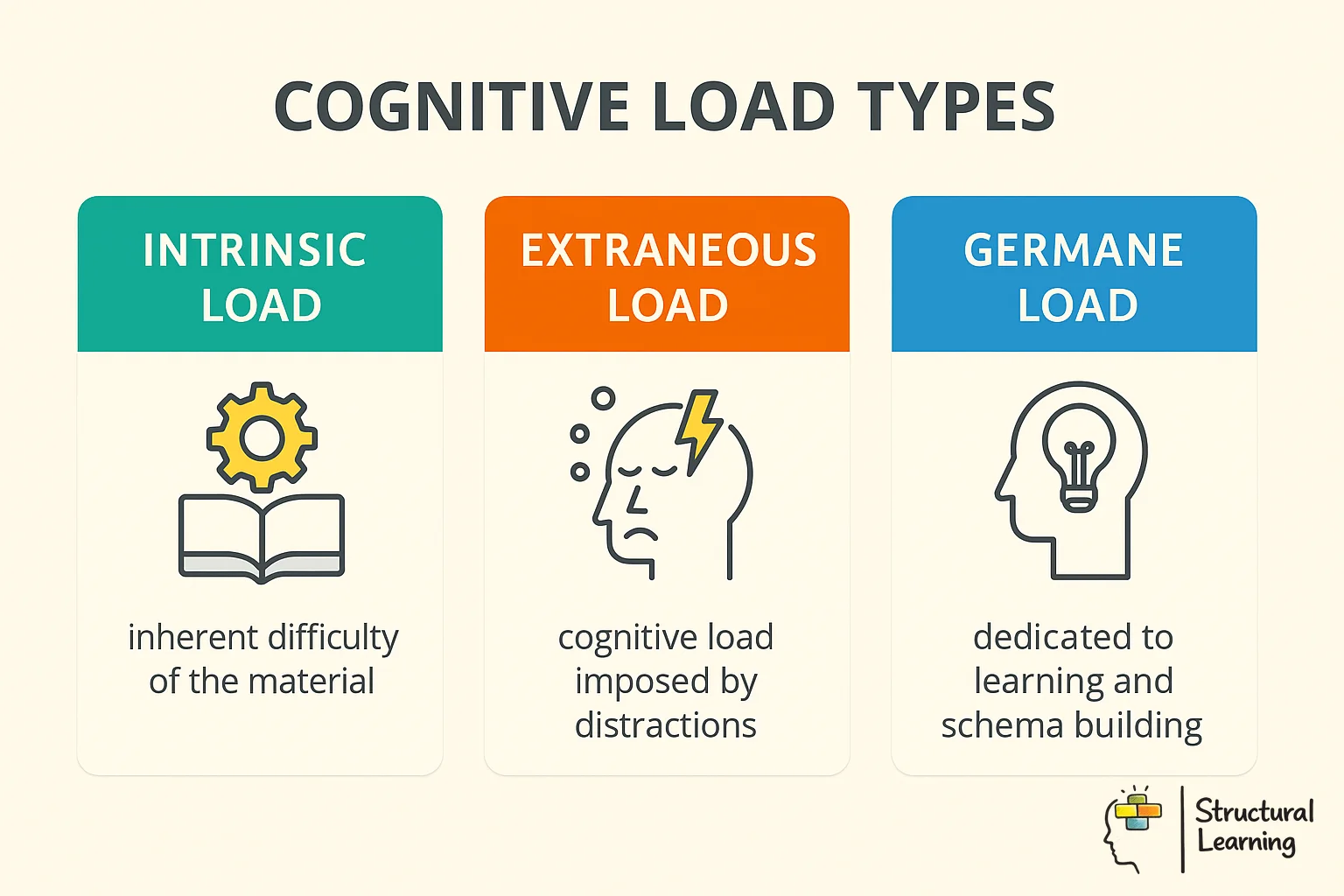

Understanding the three types of cognitive load is fundamental to applying CLT effectively in classrooms. Each type plays a distinct role in the learning process, and teachers must manage them differently to improve learning outcomes.

Intrinsic load is determined by the complexity of the material being learned and the learner's prior knowledge. A topic with many interacting elements that must be processed simultaneously imposes high intrinsic load. For example, understanding how photosynthesis works requires simultaneously considering light energy, chlorophyll, carbon dioxide, water, glucose production, and oxygen release, these elements interact and cannot be learned in complete isolation.

Intrinsic load cannot be eliminated because it is inherent to the content itself. However, it can be managed through careful instructional sequencing, teaching component skills before combining them, and building prior knowledge that reduces the novelty of new material. A Year 8 science teacher might first teach about chemical reactions in isolation, then plant cell structure separately, before combining these concepts to explain photosynthesis. This approach reduces the number of novel elements students must process simultaneously.

Subject-specific intrinsic load considerations:

Extraneous load results from poor instructional design that requires mental effort unrelated to learning objectives. This includes searching for relevant information in cluttered materials, mentally integrating spatially separated text and diagrams, processing redundant information, and decoding unnecessarily complex language.

Extraneous load can and should be minimised. Every unit of working memory capacity consumed by extraneous processing is unavailable for genuine learning. Much of CLT research focuses on identifying and eliminating sources of extraneous load through evidence-based design principles.

Common sources of extraneous load in classrooms:

Germane load is the productive cognitive effort dedicated to constructing and automating schemas. This is the "good" cognitive work that leads to meaningful learning. When extraneous load is minimised and intrinsic load is appropriately managed, more working memory capacity becomes available for germane processing.

The total of all three types of load cannot exceed working memory capacity. The instructional design goal is to minimise extraneous load and manage intrinsic load through appropriate sequencing so that sufficient capacity remains for germane processing. Teachers should actively promote germane load through activities that encourage deep processing: self-explanation, making connections to prior knowledge, comparing and contrasting examples, and elaborative rehearsal.

Strategies to promote germane load:

Recognising when cognitive load exceeds working memory capacity is essential for responsive teaching. Watch for these warning signs:

When you notice these signs: Pause instruction, break content into smaller components, remove extraneous information, provide worked examples, or activate relevant prior knowledge before continuing.

Decades of research have identified specific effects that guide practical application of CLT in educational settings. Understanding these effects enables teachers to design more effective instruction across all subjects and year groups.

Studying worked examples is more effective for novices than solving equivalent problems independently. Problem-solving imposes high cognitive load as learners search for solutions through trial and error, leaving less capacity for learning the underlying procedures. Worked examples show the solution path directly, allowing learners to focus cognitive resources on understanding the method rather than discovering it.

As learners gain expertise, the balance shifts. Eventually, studying examples becomes redundant and problem-solving becomes more effective. This transition can be managed by gradually fading scaffolding from fully worked examples through partially completed problems to independent problem-solving.

Worked example implementation across subjects:

Mathematics (Year 7 Algebra): Rather than asking students to immediately solve "3x + 7 = 22", first display a complete worked example: "To solve 2x + 5 = 13, we first subtract 5 from both sides: 2x + 5 - 5 = 13 - 5, giving us 2x = 8. Then we divide both sides by 2: 2x ÷ 2 = 8 ÷ 2, therefore x = 4. Notice how we perform the same operation on both sides to maintain the equation balance." Students study this complete solution before attempting similar problems, building schemas for equation-solving procedures.

English (Analytical Writing): Provide a model paragraph with annotations showing how topic sentences, evidence selection, quotation integration, and analysis work together: "The writer uses the metaphor of 'caged bird' to represent oppression [identification]. In the line 'his wings are clipped and his feet are tied' [evidence], the physical restraint symbolises the systematic denial of freedom [explanation]. This vivid imagery evokes both sympathy and anger in readers [effect]." Students study this structure before writing their own analytical paragraphs.

Science (Experimental Method): Show a fully worked investigation with hypothesis, variables, method, results, and conclusion explicitly stated and explained. Walk through each section: "We hypothesised that increasing light intensity would increase photosynthesis rate because plants need light energy to drive the reaction. Our independent variable was light intensity (controlled by distance from lamp). Our dependent variable was oxygen bubble count. Our controlled variables included water temperature, plant type, and CO2 concentration." Students examine this complete example before designing their own investigations.

When learners must mentally integrate information from multiple sources that are physically or temporally separated, cognitive load increases unnecessarily. Looking at a diagram and then searching for the relevant text explanation in a separate paragraph consumes working memory capacity that could otherwise support genuine learning.

The solution is to physically integrate related information. Place labels directly on diagrams rather than in separate legends. Present text explanations immediately adjacent to the images they describe. Synchronise audio explanations with visual demonstrations rather than presenting them sequentially.

Practical applications:

When identical information is presented in multiple forms simultaneously, learners waste cognitive resources processing redundant material. Reading text whilst simultaneously hearing the same text spoken adds load without adding learning value because students must process the same information through both channels.

This has immediate implications for classroom practice. Displaying bullet points on slides whilst reading them aloud word-for-word is redundant. Either show the text for students to read silently or speak the explanation whilst showing relevant images, diagrams, or demonstrations, not both together.

Avoiding redundancy in teaching:

Working memory has partially separate processing channels for visual and auditory information. Presenting words as spoken audio alongside visual images uses both channels, effectively expanding working memory capacity. Presenting words as on-screen text alongside visual images uses only the visual channel, creating potential overload as both compete for the same limited resources.

The implication: when presenting diagrams, animations, or demonstrations, accompany them with spoken explanation rather than written text. However, if learners need to process complex text carefully or reference information repeatedly, visual presentation may be preferable because students can control pacing through re-reading.

Strategic use of dual modality:

Instructional techniques that help novices may hinder experts, and vice versa. Worked examples benefit novices but become redundant for experts who already possess relevant schemas. Integrated formats help novices avoid split attention but may add extraneous load for experts who can easily mentally integrate separated elements.

This effect has profound implications for differentiation. High-achieving students may need less scaffolding, not just harder content. Continuing to provide detailed worked examples to students who have moved past needing them can actually impede their learning by forcing them to process information they've already automated.

Differentiation based on expertise reversal:

Traditional problem-solving requires learners to work backwards from goals, creating cognitive load through means-ends analysis. Goal-free problems reduce this load by asking students to "find what you can" rather than targeting specific solutions. This allows learners to focus on applying procedures and recognising patterns rather than strategic planning.

For example, instead of "Calculate the area of this triangle" (specific goal), try "Calculate as many measurements as you can for this triangle" (goal-free). Students might find area, perimeter, angles, and height, practising multiple procedures without the cognitive load of working backwards from a predetermined target.

Goal-free problems work particularly well during initial skill acquisition when students are learning procedures but haven't yet developed strategic schemas for selecting which procedure to apply in different contexts.

Completion problems bridge the gap between fully worked examples and independent problem-solving. By providing partially completed solutions where students fill in missing steps, teachers create productive cognitive load without overwhelming working memory.

Example progression in Year 9 Mathematics:

This gradual fading of support manages cognitive load whilst building towards independence, ensuring students don't experience abrupt transition from complete support to none.

Practical, research-backed techniques for minimising cognitive overload:

Before the Lesson:

During Instruction:

During Practice:

When Students Struggle:

Schema theory forms the theoretical foundation of Cognitive Load Theory, explaining how our minds organise and store knowledge in long-term memory. A schema is a cognitive framework that helps us organise and interpret information, acting like a mental filing system that groups related concepts, procedures, and facts into meaningful units.

The relationship between schemas and cognitive load is significant for learning. When students lack relevant schemas, every element of new information must be processed individually in working memory, quickly overwhelming its limited capacity of approximately four to seven items. However, when students possess well-developed schemas, complex information can be processed as single units, dramatically reducing cognitive load and freeing up mental resources for deeper learning.

Consider teaching photosynthesis to Year 7 students. Without schemas, students must simultaneously process multiple disconnected elements: chlorophyll, sunlight, carbon dioxide, water, glucose, and oxygen. This exceeds working memory capacity, leading to confusion and poor retention. However, students with well-established schemas for 'chemical reactions' and 'plant structure' can integrate these new elements into existing frameworks, reducing cognitive load and enabling meaningful learning.

Sweller's research in the 1990s demonstrated that schemas enable 'chunking', where multiple information elements are grouped into single cognitive units. This process is largely automatic and occurs below conscious awareness, but its effects on learning are profound. A novice mathematics student solving algebraic equations must consciously manipulate each symbol and operation separately. An expert, however, recognises equation patterns instantly, processing entire equation types as single chunks.

This chunking effect explains why expertise appears almost magical to novices. Expert teachers recognise classroom management patterns, reading difficulties, or misconceptions immediately, whilst beginning teachers struggle to process the same information simultaneously. The expert's schemas have automated routine cognitive processes, freeing working memory for higher-level thinking and responsive teaching decisions.

For example: A novice teacher observing a struggling reader might notice: (1) slow pace, (2) frequent hesitations, (3) skipped words, (4) self-corrections, (5) lack of expression. Processing these five separate elements overwhelms working memory, making diagnosis difficult. An experienced literacy teacher instantly recognises this pattern as a single chunk: "developing fluency but strong comprehension monitoring skills", freeing cognitive capacity to plan appropriate interventions.

Teachers can systematically help students develop strong schemas through deliberate instructional strategies. Research by Paas and van Merriënboer suggests that explicit schema construction should precede complex problem-solving activities.

Identify key schemas for your subject: In history, essential schemas include 'causation', 'chronology', 'change and continuity', and 'source evaluation'. In science, fundamental schemas include 'fair testing', 'variables', 'observation versus inference', and 'research-informed argument'. In mathematics, core schemas include 'proportional reasoning', 'algebraic structure', and 'geometric relationships'. Make these thinking frameworks explicit rather than assuming students will develop them independently through exposure.

Use worked examples to demonstrate expert schemas: When teaching essay writing, don't just provide the final product; show students how you categorise evidence, link ideas, and structure arguments. Think aloud as you work: "I'm looking for evidence that shows change over time.. This quotation works because it demonstrates the character's development.. I'll link this paragraph to the previous one using 'Furthermore' to show I'm building my argument.." Making your expert schemas visible helps novice learners understand how to organise their own thinking.

Provide multiple, varied examples: Present the same concept through different contexts to help students abstract essential features from surface details. When teaching fractions, present the concept through pizzas, number lines, rectangular shapes, sets of objects, and real-world measurement problems. This variation helps students develop flexible schemas that recognise "fraction" as a relationship between parts and wholes, regardless of representation.

Gradually increase complexity as schemas strengthen: Begin with simple, clear examples that isolate core features before introducing complications or exceptions. When teaching persuasive writing, start with straightforward arguments on familiar topics before tackling nuanced positions on complex issues. Once students have automated basic persuasive structures (claim, evidence, reasoning), their working memory capacity increases, allowing them to handle sophisticated rhetorical techniques.

Provide regular schema activation opportunities: Brief retrieval practice, concept mapping, comparing and contrasting, and making explicit connections betw een topics all strengthen existing schemas whilst preparing students to integrate new information efficiently. Start lessons by activating relevant schemas: "Remember when we learned about chemical bonds? Today's topic on molecular reactions builds on that foundation.."

Different subjects present unique cognitive load challenges based on their characteristic content structures, thinking processes, and element interactivity. Understanding these subject-specific considerations enables teachers to apply CLT principles more effectively within their disciplines.

Mathematics imposes particularly high intrinsic load due to its abstract symbol systems and complex procedural sequences. Students must simultaneously process symbols, operations, and mathematical relationships, creating substantial element interactivity.

Reducing cognitive load in mathematics:

Example, Teaching Algebraic Expansion (Year 9):

High cognitive load approach: "Expand these brackets: (2x + 5)(3x - 4), (x - 7)(x + 2), (4x + 1)(x - 9)." Students must simultaneously recall expansion rules, manage multiple terms, coordinate signs, and combine like terms.

Reduced cognitive load approach: First, show fully worked example: "(x + 3)(x + 4) = x(x + 4) + 3(x + 4) = x² + 4x + 3x + 12 = x² + 7x + 12. Notice how we multiply each term in the first bracket by each term in the second, then combine like terms." Then provide completion problems with scaffolding before independent practice.

Reading comprehension and literary analysis require students to simultaneously process vocabulary, syntax, inferences, themes, and author techniques, creating high cognitive load, particularly for struggling readers.

Reducing cognitive load in English:

Example, Teaching Poetry Analysis (Year 8):

High cognitive load approach: "Read this poem and write three paragraphs analysing how the poet uses language and structure to convey meaning." Students must simultaneously decode text, identify techniques, consider effects, plan writing, and compose analytical prose.

Reduced cognitive load approach: First reading focuses only on understanding what the poem describes. Second reading identifies language patterns using a checklist. Third reading considers effects of specific identified techniques. Then provide a model analytical paragraph showing the structure. Students write their own paragraphs using sentence stems. Finally, students write independently after these scaffolds are removed.

Science requires students to connect observable phenomena with abstract theoretical models, manage unfamiliar terminology, and understand complex causal systems, creating substantial intrinsic load.

Reducing cognitive load in science:

Example, Teaching States of Matter (Year 7):

High cognitive load approach: Presenting particle theory, state changes, energy transfer, and practical applications simultaneously creates overwhelming element interactivity.

Reduced cognitive load approach: Begin with observable demonstrations of solids, liquids, and gases. Then introduce particle models for each state separately. Next, show particle movement during state changes one at a time (solid to liquid, then liquid to gas). Finally, connect energy to particle movement. Each component is mastered before combining into integrated understanding.

History requires students to consider multiple causes, evaluate evidence reliability, understand chronology, and construct arguments, creating high cognitive load when these processes occur simultaneously.

Reducing cognitive load in history:

Example, Teaching Causation of World War I (Year 9):

High cognitive load approach: "Explain the causes of World War I" requires students to simultaneously recall multiple events, understand their interactions, categorise causes, and construct a coherent explanation.

Reduced cognitive load approach: First, establish chronological timeline of key events. Then examine each major cause separately (alliance system, imperialism, militarism, nationalism). Next, categorise causes as long-term versus short-term using a graphic organiser. Provide a model paragraph explaining one cause. Students write about other causes using the same structure. Finally, students synthesise understanding by explaining how causes interconnected.

Teachers apply cognitive load theory by breaking complex topics into smaller chunks, using worked examples before practice problems, and presenting diagrams with integrated text rather than separate captions. Start lessons with simple concepts and gradually increase complexity whilst removing scaffolds as students gain expertise. Use dual coding by combining verbal explanations with visual aids to distribute load across both processing channels.

Practical implementation strategies:

| CLT Principle | Classroom Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Limit new information | Introduce concepts one at a time. Check understanding before adding complexity. | Teach adjectives before adverbs. Master nouns before introducing abstract noun categories. |

| Use worked examples | Model problem-solving processes explicitly. Think aloud whilst demonstrating. | Show complete long division solution with every step explained before students practise. |

| Reduce split attention | Integrate text into diagrams. Point to relevant parts whilst explaining. | Label parts of a plant cell directly on the diagram rather than using numbered key. |

| Eliminate redundancy | Do not read slides aloud. Either speak or display text, not both simultaneously. | Show diagram whilst verbally explaining, rather than text and identical speech. |

| Use dual coding | Pair verbal explanations with relevant images, diagrams, or demonstrations. | Describe historical events whilst showing timeline, map, or contemporary images. |

| Sequence carefully | Teach component skills before combining them. Build from simple to complex. | Master simple sentences before compound sentences before complex sentences. |

| Build prior knowledge | Activate and develop relevant schemas before introducing new material. | Review chemical bonding before teaching molecular structures and reactions. |

| Fade scaffolding | Gradually remove support as expertise develops. Adjust for individual progress. | Worked example → completion problem → independent practice with decreasing guidance. |

Design explanations by presenting information in small steps, using clear language without unnecessary details, and connecting new concepts to prior knowledge. Integrate words and visuals spatially and temporally, avoiding split attention between different sources of information. Signal important relationships between elements and provide worked examples that show the problem-solving process explicitly.

Teacher explanations are the primary means of managing cognitive load in classrooms. Effective explanations present information in digestible chunks, use concrete examples before abstract principles, check understanding frequently, and provide processing time.

The "I do, we do, you do" structure aligns perfectly with CLT principles:

Key principles for CLT-informed explanations:

These practical steps will help you manage your pupils' cognitive load and improve student achievement across all subjects.

A Year 5 teacher introducing long multiplication strategically reduces cognitive load through carefully designed instruction:

Step 1, Activate prior knowledge: "We've mastered times tables and single-digit multiplication. Long multiplication uses those same skills. Let's review 6 × 8.." This ensures foundational schemas are accessible.

Step 2, Demonstrate worked example: On the board, show 24 × 3 completely worked with explicit explanation: "First, we multiply 3 × 4 ones = 12 ones. We write 2 in the ones column and carry 1 ten. Then we multiply 3 × 2 tens = 6 tens, plus our carried 1 ten = 7 tens. Answer: 72." Students observe complete solution path without solving themselves.

Step 3, Provide completion problems: Show 35 × 4 with first step completed: "4 × 5 = 20, so we write 0 and carry 2. Now you complete the next step.." Students fill in missing steps with scaffolding.

Step 4, Independent practice with similar problems: Once competent with single-digit multipliers, only then introduce 23 × 14 (two-digit multiplier), again using worked examples before practice. Complexity increases only after foundational skills are secure.

Step 5, Monitor for overload: Teacher circulates, watching for signs of confusion. When several students struggle, pauses class to reteach rather than allowing persistent failure.

This systematic approach manages intrinsic load through sequencing, minimises extraneous load through clear presentation, and promotes germane load through worked examples and appropriately challenging practice.

No. Germane load, the productive effort of learning, is desirable and necessary. The goal is to minimise wasted effort (extraneous load) and manage intrinsic load appropriately so that sufficient working memory capacity remains for meaningful cognitive work. Appropriately challenging tasks that require thinking about content are valuable; confusing or poorly designed tasks that require thinking about how to work through the task itself are not. Challenge should come from engaging with content, not from deciphering unclear instructions or managing split attention.

CLT research does not support learning styles theory. The modality effect concerns working memory architecture, which is essentially the same across individuals. Presenting information in a student's preferred "style" does not improve learning; presenting it in a format that improves cognitive load does. Content type, not learner preference, should determine presentation format. Diagrams benefit from spoken explanation (modality effect) for all learners, not just "auditory learners". Teaching should be guided by how human memory works, not by unvalidated learning style preferences.

These approaches can impose high extraneous load on novices who lack the schemas to guide their discovery efficiently. Research consistently shows that direct instruction is more effective for novice learners. Problem-solving requires means-ends analysis, which consumes working memory capacity that novices need for understanding content. As expertise develops through explicit instruction and worked examples, more open-ended approaches become appropriate because students possess schemas that make exploration productive rather than overwhelming. The key is matching instructional approach to learner expertise: high guidance for novices, decreasing guidance as expertise grows.

Signs of overload include confusion, inability to answer basic questions about just-presented content, copying without understanding, abandoning tasks quickly, and increasing off-task behaviour. Checking for understanding frequently helps identify when load exceeds capacity before students become frustrated. If many students struggle simultaneously, the instructional design likely needs adjustment, break content into smaller chunks, remove extraneous information, provide worked examples, or activate missing prior knowledge. Individual struggle might indicate insufficient prior knowledge; widespread struggle suggests excessive cognitive load in the lesson design.

CLT principles apply across all ages and abilities because working memory limitations are universal. However, the expertise reversal effect means that instructional techniques must adapt to expertise level. More knowledgeable students possess schemas that effectively expand their working memory, allowing them to handle greater complexity. These students need less scaffolding, can integrate separated information sources independently, and benefit from problem-solving rather than worked examples. High-ability students still experience cognitive overload when too many novel elements are presented simultaneously, their threshold is simply higher. Differentiation should adjust scaffolding levels and complexity whilst maintaining CLT principles.

Yes, through metacognitive awareness and strategic learning behaviours. Teach students to recognise when they feel overwhelmed and employ strategies like breaking tasks into steps, using worked examples as references, creating diagrams to organise information, and pausing to consolidate before continuing. Explicitly teach note-taking methods that reduce split attention, chunking strategies for memorising information, and self-explanation techniques that promote germane load. Students who understand their working memory limitations can make informed decisions about pacing, resource use, and help-seeking.

No. Reducing cognitive load eliminates unnecessary difficulty whilst preserving productive challenge. Struggling with split attention or unclear instructions doesn't build resilience, it wastes mental resources. Germane load, the effortful processing that builds understanding, should be maximised by removing extraneous and managing intrinsic load. Well-designed instruction is appropriately challenging because students can dedicate full cognitive capacity to understanding content rather than wrestling with presentation format. Difficulty should come from engaging with complex ideas, not from poor instructional design.

| Load Type | Definition | Classroom Examples | Teacher Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Load | Inherent complexity of the material being learned; depends on element interactivity and learner expertise | Learning simultaneous equations (high); learning vocabulary words (low); understanding photosynthesis (moderate) | Sequence content from simple to complex; isolate elements before combining; build foundational knowledge first |

| Extraneous Load | Unnecessary cognitive effort caused by poor instructional design; does NOT contribute to learning | Split attention between diagram and text; decorative images; confusing layouts; unclear instructions | Integrate text with visuals; remove seductive details; simplify presentations; use clear, direct language |

| Germane Load | Productive effort dedicated to schema construction and automation; the "good" cognitive work | Self-explaining why steps work; comparing examples; connecting to prior knowledge; elaborative practice | Use worked examples; prompt self-explanation; vary practice contexts; encourage elaboration and connections |

Based on Sweller's Cognitive Load Theory (1988, updated 2019). The goal of instruction is to minimise extraneous load, manage intrinsic load, and maximise germane load within working memory's limited capacity.

The field of Cognitive Load Theory continues to evolve, with researchers exploring new applications and refining our understanding of how working memory constraints affect learning. These developments offer fresh insights for educators seeking empirically supported approaches to instructional design.

Recent research by Kirschner, Paas, and Kirschner (2009) has extended CLT beyond individual cognition to examine how groups share cognitive resources. The concept of collective working memory suggests that when students collaborate effectively, they can pool their working memory capacities and distribute cognitive load across team members. For instance, in a science investigation, one student might focus on data collection whilst another analyses patterns, allowing each to dedicate full working memory to their specific task rather than managing everything simultaneously.

This research has profound implications for classroom practice. Rather than viewing group work as simply motivational, teachers can strategically design collaborative tasks where different students handle distinct cognitive processes. However, this requires careful orchestration to ensure students don't merely divide labour without meaningful cognitive engagement. Effective collaborative tasks distribute cognitive load whilst ensuring all students engage in germane processing.

Practical applications: In complex problem-solving tasks, assign complementary roles: one student manages information organisation, another focuses on strategy generation, another evaluates progress. Rotate roles across different tasks to ensure all students develop complete skill sets. This distribution prevents individual cognitive overload whilst maintaining productive challenge.

Manu Kapur's productive failure framework challenges traditional CLT applications by suggesting that initial struggle with complex problems, even without success, can improve subsequent learning. This approach deliberately allows students to experience cognitive overload during exploration phases, followed by consolidation through direct instruction.

In mathematics, for example, students might first attempt to solve complex ratio problems without formal instruction, generating multiple solution attempts. Though these initial efforts often fail, they prime students' working memory for subsequent teacher explanations, making the formal algorithms more meaningful. The struggle activates relevant schemas and creates productive confusion that makes later instruction more impactful.

This research suggests that strategic, temporary cognitive overload may actually benefit learning when properly scaffolded and followed by explicit instruction. However, this contradicts traditional CLT guidance about minimising cognitive load, creating ongoing debate about optimal timing and implementation.

Contemporary CLT research increasingly focuses on digital learning contexts. Van Merriënboer and Sweller's recent work (2020) explores how interactive simulations, virtual reality, and adaptive learning systems can manage cognitive load more dynamically than traditional materials.

Digital environments offer unique opportunities for adaptive cognitive load management. Educational software can monitor student performance and automatically adjust complexity, removing extraneous elements when learners struggle or adding challenge when they demonstrate mastery. Virtual laboratories can eliminate irrelevant visual details that might overload novice students whilst maintaining essential features for skill development.

However, digital tools also introduce new sources of extraneous load. Poor interface design, unnecessary animations, complex navigation systems, or distracting interactive elements can overwhelm working memory. Teachers must evaluate educational technology through a CLT lens, ensuring digital enhancements genuinely support rather than hinder learning. The seductive appeal of multimedia doesn't guarantee learning effectiveness.

Recent developments have also influenced assessment practices. Traditional tests often impose significant extraneous cognitive load through complex formatting, ambiguous instructions, or irrelevant context. CLT-informed assessment design focuses on reducing these barriers to allow genuine measurement of student understanding.

For example, rather than embedding mathematics problems within lengthy word problems featuring irrelevant details ("Sarah has 47 red marbles, 23 blue marbles, and 15 green marbles in her collection that she started on her birthday in June.."), assessments might present information more directly whilst still testing application skills ("Sarah has 47 red marbles, 23 blue marbles, and 15 green marbles. How many marbles in total?"). Similarly, providing reference sheets for formulas allows students to focus working memory on problem-solving processes rather than memorisation during high-stakes assessments.

These developments collectively demonstrate CLT's continued relevance and evolution, offering educators increasingly sophisticated tools for improving learning experiences across diverse educational contexts.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into cognitive load theory and its application in educational settings.

Cognitive Load Theory and Instructional Design: Recent Developments High impact

Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. (2019)

This thorough review by the theory's founder traces the evolution of CLT from its origins to contemporary applications. It synthesises decades of research on worked examples, split attention, modality effects, and expertise reversal, providing teachers with essential theoretical background and practical guidance for instructional design.

Relationship between cognitive load and motivation in healthcare education 15 citations

Patel et al. (2024)

This paper examines how cognitive load theory intersects with student motivation and emotions, particularly in healthcare education settings. It helps teachers understand that managing cognitive load isn't just about information processing, but also involves considering how mental workload affects student engagement and emotional responses during learning.

Flipped classroom models in online learning 18 citations

Diningrat et al. (2023)

This study investigates how flipped classroom approaches work in fully online environments and how individual differences in working memory capacity affect student reading comprehension outcomes. It provides teachers with practical insights into adapting flipped classroom models for different learning contexts whilst considering that students have varying cognitive capacities.

The comparative impacts of portfolio-based assessment, self-assessment, and scaffolded peer assessment on reading comprehension 11 citations

Al-Rashidi et al. (2023)

This research compares different assessment methods and their effectiveness based on students' working memory capacity, focusing on language educational results. It offers teachers research-backed guidance on selecting appropriate assessment strategies that account for individual cognitive differences amongst students.

Working memory and collaborative learning 12 citations

Du et al. (2022)

This experimental study examines how students' working memory capacity influences the effectiveness of collaborative learning activities in elementary classrooms. It provides teachers with important insights into when and how to use group work, showing that cognitive capacity differences can significantly impact collaborative learning gains.

Cognitive Load Theory provides a scientifically strong framework for understanding why some teaching approaches work better than others. The fundamental insight, that working memory has severe limitations of approximately four to seven chunks of novel information, must inform every instructional decision we make. By systematically reducing extraneous load, carefully managing intrinsic load through sequencing and prior knowledge development, and promoting germane load through meaningful processing activities, teachers can dramatically improve academic progress without changing content difficulty.

The evidence is compelling: worked examples outperform problem-solving for novices, integrated materials reduce split attention, dual modality expands effective working memory capacity, and scaffolding must fade as expertise develops. These aren't theoretical abstractions but practical tools that translate directly into classroom practice across all subjects and year groups.

However, CLT is not a rigid prescription but a flexible framework requiring professional judgement. Teachers must assess student expertise levels, identify sources of cognitive load in their materials, recognise signs of overload during instruction, and adjust responsively. The expertise reversal effect reminds us that effective instruction for novices differs fundamentally from effective instruction for experts, differentiation must account for cognitive capacity, not just content difficulty.

Implementing CLT successfully requires deliberate practice: analysing your explanations for extraneous load, designing worksheets with integrated text and diagrams, creating worked example sequences with systematic scaffold fading, and monitoring students for signs of cognitive overload. Start with one principle, perhaps eliminating split attention in your worksheets, master it, then add another. Over time, CLT-informed design becomes intuitive, and you'll instinctively create materials that work with students' cognitive architecture rather than against it.

The ultimate goal is simple: ensure that every unit of students' limited working memory capacity is dedicated to genuine learning rather than wasted on poor instructional design. When we achieve this, we give students the best possible chance to build the rich schemas that define expertise and enable independent, flexible thinking. That's the promise of Cognitive Load Theory, not to make learning easy, but to make it efficient, effective, and focused on what truly matters.

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), developed by educational psychologist John Sweller in the late 1980s, explains how the architecture of human memory affects learning. The theory has become one of the most influential frameworks in education, providing practical guidance for instructional design and forming a cornerstone of cognitive learning theory.

The central insight of CLT is that working memory, where conscious processing occurs, has strict capacity limits. We can only hold and manipulate approximately four to seven new items simultaneously. When instructional materials demand more processing than working memory can handle, learning fails regardless of student motivation or ability. However, information stored in long-term memory through schema construction can be processed as single units, effectively expanding working memory capacity. Developing cognitive skills and metacognitive awareness of cognitive load helps students recognise when they're approaching these li mits.

teacher's guide" loading="lazy">

teacher's guide" loading="lazy">Long-term memory, by contrast, has essentially unlimited capacity. Information stored in long-term memory can be retrieved into working memory as schemas, organised knowledge structures that help us process new information efficiently. This connects to schema theory, which explains how mental frameworks shape learning. Well-developed schemas allow experts to process complex information as single units, bypassing the processing limits that constrain new information. Effective teaching helps students build schemas that transfer knowledge from fragile working memory to durable long-term memory.

Understanding the three types of cognitive load is fundamental to applying CLT effectively in classrooms. Each type plays a distinct role in the learning process, and teachers must manage them differently to improve learning outcomes.

Intrinsic load is determined by the complexity of the material being learned and the learner's prior knowledge. A topic with many interacting elements that must be processed simultaneously imposes high intrinsic load. For example, understanding how photosynthesis works requires simultaneously considering light energy, chlorophyll, carbon dioxide, water, glucose production, and oxygen release, these elements interact and cannot be learned in complete isolation.

Intrinsic load cannot be eliminated because it is inherent to the content itself. However, it can be managed through careful instructional sequencing, teaching component skills before combining them, and building prior knowledge that reduces the novelty of new material. A Year 8 science teacher might first teach about chemical reactions in isolation, then plant cell structure separately, before combining these concepts to explain photosynthesis. This approach reduces the number of novel elements students must process simultaneously.

Subject-specific intrinsic load considerations:

Extraneous load results from poor instructional design that requires mental effort unrelated to learning objectives. This includes searching for relevant information in cluttered materials, mentally integrating spatially separated text and diagrams, processing redundant information, and decoding unnecessarily complex language.

Extraneous load can and should be minimised. Every unit of working memory capacity consumed by extraneous processing is unavailable for genuine learning. Much of CLT research focuses on identifying and eliminating sources of extraneous load through evidence-based design principles.

Common sources of extraneous load in classrooms:

Germane load is the productive cognitive effort dedicated to constructing and automating schemas. This is the "good" cognitive work that leads to meaningful learning. When extraneous load is minimised and intrinsic load is appropriately managed, more working memory capacity becomes available for germane processing.

The total of all three types of load cannot exceed working memory capacity. The instructional design goal is to minimise extraneous load and manage intrinsic load through appropriate sequencing so that sufficient capacity remains for germane processing. Teachers should actively promote germane load through activities that encourage deep processing: self-explanation, making connections to prior knowledge, comparing and contrasting examples, and elaborative rehearsal.

Strategies to promote germane load:

Recognising when cognitive load exceeds working memory capacity is essential for responsive teaching. Watch for these warning signs:

When you notice these signs: Pause instruction, break content into smaller components, remove extraneous information, provide worked examples, or activate relevant prior knowledge before continuing.

Decades of research have identified specific effects that guide practical application of CLT in educational settings. Understanding these effects enables teachers to design more effective instruction across all subjects and year groups.

Studying worked examples is more effective for novices than solving equivalent problems independently. Problem-solving imposes high cognitive load as learners search for solutions through trial and error, leaving less capacity for learning the underlying procedures. Worked examples show the solution path directly, allowing learners to focus cognitive resources on understanding the method rather than discovering it.

As learners gain expertise, the balance shifts. Eventually, studying examples becomes redundant and problem-solving becomes more effective. This transition can be managed by gradually fading scaffolding from fully worked examples through partially completed problems to independent problem-solving.

Worked example implementation across subjects:

Mathematics (Year 7 Algebra): Rather than asking students to immediately solve "3x + 7 = 22", first display a complete worked example: "To solve 2x + 5 = 13, we first subtract 5 from both sides: 2x + 5 - 5 = 13 - 5, giving us 2x = 8. Then we divide both sides by 2: 2x ÷ 2 = 8 ÷ 2, therefore x = 4. Notice how we perform the same operation on both sides to maintain the equation balance." Students study this complete solution before attempting similar problems, building schemas for equation-solving procedures.

English (Analytical Writing): Provide a model paragraph with annotations showing how topic sentences, evidence selection, quotation integration, and analysis work together: "The writer uses the metaphor of 'caged bird' to represent oppression [identification]. In the line 'his wings are clipped and his feet are tied' [evidence], the physical restraint symbolises the systematic denial of freedom [explanation]. This vivid imagery evokes both sympathy and anger in readers [effect]." Students study this structure before writing their own analytical paragraphs.

Science (Experimental Method): Show a fully worked investigation with hypothesis, variables, method, results, and conclusion explicitly stated and explained. Walk through each section: "We hypothesised that increasing light intensity would increase photosynthesis rate because plants need light energy to drive the reaction. Our independent variable was light intensity (controlled by distance from lamp). Our dependent variable was oxygen bubble count. Our controlled variables included water temperature, plant type, and CO2 concentration." Students examine this complete example before designing their own investigations.

When learners must mentally integrate information from multiple sources that are physically or temporally separated, cognitive load increases unnecessarily. Looking at a diagram and then searching for the relevant text explanation in a separate paragraph consumes working memory capacity that could otherwise support genuine learning.

The solution is to physically integrate related information. Place labels directly on diagrams rather than in separate legends. Present text explanations immediately adjacent to the images they describe. Synchronise audio explanations with visual demonstrations rather than presenting them sequentially.

Practical applications:

When identical information is presented in multiple forms simultaneously, learners waste cognitive resources processing redundant material. Reading text whilst simultaneously hearing the same text spoken adds load without adding learning value because students must process the same information through both channels.

This has immediate implications for classroom practice. Displaying bullet points on slides whilst reading them aloud word-for-word is redundant. Either show the text for students to read silently or speak the explanation whilst showing relevant images, diagrams, or demonstrations, not both together.

Avoiding redundancy in teaching:

Working memory has partially separate processing channels for visual and auditory information. Presenting words as spoken audio alongside visual images uses both channels, effectively expanding working memory capacity. Presenting words as on-screen text alongside visual images uses only the visual channel, creating potential overload as both compete for the same limited resources.

The implication: when presenting diagrams, animations, or demonstrations, accompany them with spoken explanation rather than written text. However, if learners need to process complex text carefully or reference information repeatedly, visual presentation may be preferable because students can control pacing through re-reading.

Strategic use of dual modality:

Instructional techniques that help novices may hinder experts, and vice versa. Worked examples benefit novices but become redundant for experts who already possess relevant schemas. Integrated formats help novices avoid split attention but may add extraneous load for experts who can easily mentally integrate separated elements.

This effect has profound implications for differentiation. High-achieving students may need less scaffolding, not just harder content. Continuing to provide detailed worked examples to students who have moved past needing them can actually impede their learning by forcing them to process information they've already automated.

Differentiation based on expertise reversal:

Traditional problem-solving requires learners to work backwards from goals, creating cognitive load through means-ends analysis. Goal-free problems reduce this load by asking students to "find what you can" rather than targeting specific solutions. This allows learners to focus on applying procedures and recognising patterns rather than strategic planning.

For example, instead of "Calculate the area of this triangle" (specific goal), try "Calculate as many measurements as you can for this triangle" (goal-free). Students might find area, perimeter, angles, and height, practising multiple procedures without the cognitive load of working backwards from a predetermined target.

Goal-free problems work particularly well during initial skill acquisition when students are learning procedures but haven't yet developed strategic schemas for selecting which procedure to apply in different contexts.

Completion problems bridge the gap between fully worked examples and independent problem-solving. By providing partially completed solutions where students fill in missing steps, teachers create productive cognitive load without overwhelming working memory.

Example progression in Year 9 Mathematics:

This gradual fading of support manages cognitive load whilst building towards independence, ensuring students don't experience abrupt transition from complete support to none.

Practical, research-backed techniques for minimising cognitive overload:

Before the Lesson:

During Instruction:

During Practice:

When Students Struggle:

Schema theory forms the theoretical foundation of Cognitive Load Theory, explaining how our minds organise and store knowledge in long-term memory. A schema is a cognitive framework that helps us organise and interpret information, acting like a mental filing system that groups related concepts, procedures, and facts into meaningful units.

The relationship between schemas and cognitive load is significant for learning. When students lack relevant schemas, every element of new information must be processed individually in working memory, quickly overwhelming its limited capacity of approximately four to seven items. However, when students possess well-developed schemas, complex information can be processed as single units, dramatically reducing cognitive load and freeing up mental resources for deeper learning.

Consider teaching photosynthesis to Year 7 students. Without schemas, students must simultaneously process multiple disconnected elements: chlorophyll, sunlight, carbon dioxide, water, glucose, and oxygen. This exceeds working memory capacity, leading to confusion and poor retention. However, students with well-established schemas for 'chemical reactions' and 'plant structure' can integrate these new elements into existing frameworks, reducing cognitive load and enabling meaningful learning.

Sweller's research in the 1990s demonstrated that schemas enable 'chunking', where multiple information elements are grouped into single cognitive units. This process is largely automatic and occurs below conscious awareness, but its effects on learning are profound. A novice mathematics student solving algebraic equations must consciously manipulate each symbol and operation separately. An expert, however, recognises equation patterns instantly, processing entire equation types as single chunks.

This chunking effect explains why expertise appears almost magical to novices. Expert teachers recognise classroom management patterns, reading difficulties, or misconceptions immediately, whilst beginning teachers struggle to process the same information simultaneously. The expert's schemas have automated routine cognitive processes, freeing working memory for higher-level thinking and responsive teaching decisions.

For example: A novice teacher observing a struggling reader might notice: (1) slow pace, (2) frequent hesitations, (3) skipped words, (4) self-corrections, (5) lack of expression. Processing these five separate elements overwhelms working memory, making diagnosis difficult. An experienced literacy teacher instantly recognises this pattern as a single chunk: "developing fluency but strong comprehension monitoring skills", freeing cognitive capacity to plan appropriate interventions.

Teachers can systematically help students develop strong schemas through deliberate instructional strategies. Research by Paas and van Merriënboer suggests that explicit schema construction should precede complex problem-solving activities.

Identify key schemas for your subject: In history, essential schemas include 'causation', 'chronology', 'change and continuity', and 'source evaluation'. In science, fundamental schemas include 'fair testing', 'variables', 'observation versus inference', and 'research-informed argument'. In mathematics, core schemas include 'proportional reasoning', 'algebraic structure', and 'geometric relationships'. Make these thinking frameworks explicit rather than assuming students will develop them independently through exposure.

Use worked examples to demonstrate expert schemas: When teaching essay writing, don't just provide the final product; show students how you categorise evidence, link ideas, and structure arguments. Think aloud as you work: "I'm looking for evidence that shows change over time.. This quotation works because it demonstrates the character's development.. I'll link this paragraph to the previous one using 'Furthermore' to show I'm building my argument.." Making your expert schemas visible helps novice learners understand how to organise their own thinking.

Provide multiple, varied examples: Present the same concept through different contexts to help students abstract essential features from surface details. When teaching fractions, present the concept through pizzas, number lines, rectangular shapes, sets of objects, and real-world measurement problems. This variation helps students develop flexible schemas that recognise "fraction" as a relationship between parts and wholes, regardless of representation.

Gradually increase complexity as schemas strengthen: Begin with simple, clear examples that isolate core features before introducing complications or exceptions. When teaching persuasive writing, start with straightforward arguments on familiar topics before tackling nuanced positions on complex issues. Once students have automated basic persuasive structures (claim, evidence, reasoning), their working memory capacity increases, allowing them to handle sophisticated rhetorical techniques.

Provide regular schema activation opportunities: Brief retrieval practice, concept mapping, comparing and contrasting, and making explicit connections betw een topics all strengthen existing schemas whilst preparing students to integrate new information efficiently. Start lessons by activating relevant schemas: "Remember when we learned about chemical bonds? Today's topic on molecular reactions builds on that foundation.."

Different subjects present unique cognitive load challenges based on their characteristic content structures, thinking processes, and element interactivity. Understanding these subject-specific considerations enables teachers to apply CLT principles more effectively within their disciplines.

Mathematics imposes particularly high intrinsic load due to its abstract symbol systems and complex procedural sequences. Students must simultaneously process symbols, operations, and mathematical relationships, creating substantial element interactivity.

Reducing cognitive load in mathematics:

Example, Teaching Algebraic Expansion (Year 9):

High cognitive load approach: "Expand these brackets: (2x + 5)(3x - 4), (x - 7)(x + 2), (4x + 1)(x - 9)." Students must simultaneously recall expansion rules, manage multiple terms, coordinate signs, and combine like terms.

Reduced cognitive load approach: First, show fully worked example: "(x + 3)(x + 4) = x(x + 4) + 3(x + 4) = x² + 4x + 3x + 12 = x² + 7x + 12. Notice how we multiply each term in the first bracket by each term in the second, then combine like terms." Then provide completion problems with scaffolding before independent practice.

Reading comprehension and literary analysis require students to simultaneously process vocabulary, syntax, inferences, themes, and author techniques, creating high cognitive load, particularly for struggling readers.

Reducing cognitive load in English:

Example, Teaching Poetry Analysis (Year 8):

High cognitive load approach: "Read this poem and write three paragraphs analysing how the poet uses language and structure to convey meaning." Students must simultaneously decode text, identify techniques, consider effects, plan writing, and compose analytical prose.

Reduced cognitive load approach: First reading focuses only on understanding what the poem describes. Second reading identifies language patterns using a checklist. Third reading considers effects of specific identified techniques. Then provide a model analytical paragraph showing the structure. Students write their own paragraphs using sentence stems. Finally, students write independently after these scaffolds are removed.

Science requires students to connect observable phenomena with abstract theoretical models, manage unfamiliar terminology, and understand complex causal systems, creating substantial intrinsic load.

Reducing cognitive load in science:

Example, Teaching States of Matter (Year 7):

High cognitive load approach: Presenting particle theory, state changes, energy transfer, and practical applications simultaneously creates overwhelming element interactivity.

Reduced cognitive load approach: Begin with observable demonstrations of solids, liquids, and gases. Then introduce particle models for each state separately. Next, show particle movement during state changes one at a time (solid to liquid, then liquid to gas). Finally, connect energy to particle movement. Each component is mastered before combining into integrated understanding.

History requires students to consider multiple causes, evaluate evidence reliability, understand chronology, and construct arguments, creating high cognitive load when these processes occur simultaneously.

Reducing cognitive load in history:

Example, Teaching Causation of World War I (Year 9):

High cognitive load approach: "Explain the causes of World War I" requires students to simultaneously recall multiple events, understand their interactions, categorise causes, and construct a coherent explanation.

Reduced cognitive load approach: First, establish chronological timeline of key events. Then examine each major cause separately (alliance system, imperialism, militarism, nationalism). Next, categorise causes as long-term versus short-term using a graphic organiser. Provide a model paragraph explaining one cause. Students write about other causes using the same structure. Finally, students synthesise understanding by explaining how causes interconnected.

Teachers apply cognitive load theory by breaking complex topics into smaller chunks, using worked examples before practice problems, and presenting diagrams with integrated text rather than separate captions. Start lessons with simple concepts and gradually increase complexity whilst removing scaffolds as students gain expertise. Use dual coding by combining verbal explanations with visual aids to distribute load across both processing channels.

Practical implementation strategies:

| CLT Principle | Classroom Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Limit new information | Introduce concepts one at a time. Check understanding before adding complexity. | Teach adjectives before adverbs. Master nouns before introducing abstract noun categories. |

| Use worked examples | Model problem-solving processes explicitly. Think aloud whilst demonstrating. | Show complete long division solution with every step explained before students practise. |

| Reduce split attention | Integrate text into diagrams. Point to relevant parts whilst explaining. | Label parts of a plant cell directly on the diagram rather than using numbered key. |

| Eliminate redundancy | Do not read slides aloud. Either speak or display text, not both simultaneously. | Show diagram whilst verbally explaining, rather than text and identical speech. |

| Use dual coding | Pair verbal explanations with relevant images, diagrams, or demonstrations. | Describe historical events whilst showing timeline, map, or contemporary images. |

| Sequence carefully | Teach component skills before combining them. Build from simple to complex. | Master simple sentences before compound sentences before complex sentences. |

| Build prior knowledge | Activate and develop relevant schemas before introducing new material. | Review chemical bonding before teaching molecular structures and reactions. |

| Fade scaffolding | Gradually remove support as expertise develops. Adjust for individual progress. | Worked example → completion problem → independent practice with decreasing guidance. |

Design explanations by presenting information in small steps, using clear language without unnecessary details, and connecting new concepts to prior knowledge. Integrate words and visuals spatially and temporally, avoiding split attention between different sources of information. Signal important relationships between elements and provide worked examples that show the problem-solving process explicitly.

Teacher explanations are the primary means of managing cognitive load in classrooms. Effective explanations present information in digestible chunks, use concrete examples before abstract principles, check understanding frequently, and provide processing time.

The "I do, we do, you do" structure aligns perfectly with CLT principles:

Key principles for CLT-informed explanations:

These practical steps will help you manage your pupils' cognitive load and improve student achievement across all subjects.

A Year 5 teacher introducing long multiplication strategically reduces cognitive load through carefully designed instruction:

Step 1, Activate prior knowledge: "We've mastered times tables and single-digit multiplication. Long multiplication uses those same skills. Let's review 6 × 8.." This ensures foundational schemas are accessible.

Step 2, Demonstrate worked example: On the board, show 24 × 3 completely worked with explicit explanation: "First, we multiply 3 × 4 ones = 12 ones. We write 2 in the ones column and carry 1 ten. Then we multiply 3 × 2 tens = 6 tens, plus our carried 1 ten = 7 tens. Answer: 72." Students observe complete solution path without solving themselves.

Step 3, Provide completion problems: Show 35 × 4 with first step completed: "4 × 5 = 20, so we write 0 and carry 2. Now you complete the next step.." Students fill in missing steps with scaffolding.

Step 4, Independent practice with similar problems: Once competent with single-digit multipliers, only then introduce 23 × 14 (two-digit multiplier), again using worked examples before practice. Complexity increases only after foundational skills are secure.

Step 5, Monitor for overload: Teacher circulates, watching for signs of confusion. When several students struggle, pauses class to reteach rather than allowing persistent failure.

This systematic approach manages intrinsic load through sequencing, minimises extraneous load through clear presentation, and promotes germane load through worked examples and appropriately challenging practice.

No. Germane load, the productive effort of learning, is desirable and necessary. The goal is to minimise wasted effort (extraneous load) and manage intrinsic load appropriately so that sufficient working memory capacity remains for meaningful cognitive work. Appropriately challenging tasks that require thinking about content are valuable; confusing or poorly designed tasks that require thinking about how to work through the task itself are not. Challenge should come from engaging with content, not from deciphering unclear instructions or managing split attention.

CLT research does not support learning styles theory. The modality effect concerns working memory architecture, which is essentially the same across individuals. Presenting information in a student's preferred "style" does not improve learning; presenting it in a format that improves cognitive load does. Content type, not learner preference, should determine presentation format. Diagrams benefit from spoken explanation (modality effect) for all learners, not just "auditory learners". Teaching should be guided by how human memory works, not by unvalidated learning style preferences.

These approaches can impose high extraneous load on novices who lack the schemas to guide their discovery efficiently. Research consistently shows that direct instruction is more effective for novice learners. Problem-solving requires means-ends analysis, which consumes working memory capacity that novices need for understanding content. As expertise develops through explicit instruction and worked examples, more open-ended approaches become appropriate because students possess schemas that make exploration productive rather than overwhelming. The key is matching instructional approach to learner expertise: high guidance for novices, decreasing guidance as expertise grows.

Signs of overload include confusion, inability to answer basic questions about just-presented content, copying without understanding, abandoning tasks quickly, and increasing off-task behaviour. Checking for understanding frequently helps identify when load exceeds capacity before students become frustrated. If many students struggle simultaneously, the instructional design likely needs adjustment, break content into smaller chunks, remove extraneous information, provide worked examples, or activate missing prior knowledge. Individual struggle might indicate insufficient prior knowledge; widespread struggle suggests excessive cognitive load in the lesson design.

CLT principles apply across all ages and abilities because working memory limitations are universal. However, the expertise reversal effect means that instructional techniques must adapt to expertise level. More knowledgeable students possess schemas that effectively expand their working memory, allowing them to handle greater complexity. These students need less scaffolding, can integrate separated information sources independently, and benefit from problem-solving rather than worked examples. High-ability students still experience cognitive overload when too many novel elements are presented simultaneously, their threshold is simply higher. Differentiation should adjust scaffolding levels and complexity whilst maintaining CLT principles.

Yes, through metacognitive awareness and strategic learning behaviours. Teach students to recognise when they feel overwhelmed and employ strategies like breaking tasks into steps, using worked examples as references, creating diagrams to organise information, and pausing to consolidate before continuing. Explicitly teach note-taking methods that reduce split attention, chunking strategies for memorising information, and self-explanation techniques that promote germane load. Students who understand their working memory limitations can make informed decisions about pacing, resource use, and help-seeking.

No. Reducing cognitive load eliminates unnecessary difficulty whilst preserving productive challenge. Struggling with split attention or unclear instructions doesn't build resilience, it wastes mental resources. Germane load, the effortful processing that builds understanding, should be maximised by removing extraneous and managing intrinsic load. Well-designed instruction is appropriately challenging because students can dedicate full cognitive capacity to understanding content rather than wrestling with presentation format. Difficulty should come from engaging with complex ideas, not from poor instructional design.

| Load Type | Definition | Classroom Examples | Teacher Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Load | Inherent complexity of the material being learned; depends on element interactivity and learner expertise | Learning simultaneous equations (high); learning vocabulary words (low); understanding photosynthesis (moderate) | Sequence content from simple to complex; isolate elements before combining; build foundational knowledge first |

| Extraneous Load | Unnecessary cognitive effort caused by poor instructional design; does NOT contribute to learning | Split attention between diagram and text; decorative images; confusing layouts; unclear instructions | Integrate text with visuals; remove seductive details; simplify presentations; use clear, direct language |

| Germane Load | Productive effort dedicated to schema construction and automation; the "good" cognitive work | Self-explaining why steps work; comparing examples; connecting to prior knowledge; elaborative practice | Use worked examples; prompt self-explanation; vary practice contexts; encourage elaboration and connections |

Based on Sweller's Cognitive Load Theory (1988, updated 2019). The goal of instruction is to minimise extraneous load, manage intrinsic load, and maximise germane load within working memory's limited capacity.

The field of Cognitive Load Theory continues to evolve, with researchers exploring new applications and refining our understanding of how working memory constraints affect learning. These developments offer fresh insights for educators seeking empirically supported approaches to instructional design.

Recent research by Kirschner, Paas, and Kirschner (2009) has extended CLT beyond individual cognition to examine how groups share cognitive resources. The concept of collective working memory suggests that when students collaborate effectively, they can pool their working memory capacities and distribute cognitive load across team members. For instance, in a science investigation, one student might focus on data collection whilst another analyses patterns, allowing each to dedicate full working memory to their specific task rather than managing everything simultaneously.

This research has profound implications for classroom practice. Rather than viewing group work as simply motivational, teachers can strategically design collaborative tasks where different students handle distinct cognitive processes. However, this requires careful orchestration to ensure students don't merely divide labour without meaningful cognitive engagement. Effective collaborative tasks distribute cognitive load whilst ensuring all students engage in germane processing.

Practical applications: In complex problem-solving tasks, assign complementary roles: one student manages information organisation, another focuses on strategy generation, another evaluates progress. Rotate roles across different tasks to ensure all students develop complete skill sets. This distribution prevents individual cognitive overload whilst maintaining productive challenge.

Manu Kapur's productive failure framework challenges traditional CLT applications by suggesting that initial struggle with complex problems, even without success, can improve subsequent learning. This approach deliberately allows students to experience cognitive overload during exploration phases, followed by consolidation through direct instruction.

In mathematics, for example, students might first attempt to solve complex ratio problems without formal instruction, generating multiple solution attempts. Though these initial efforts often fail, they prime students' working memory for subsequent teacher explanations, making the formal algorithms more meaningful. The struggle activates relevant schemas and creates productive confusion that makes later instruction more impactful.

This research suggests that strategic, temporary cognitive overload may actually benefit learning when properly scaffolded and followed by explicit instruction. However, this contradicts traditional CLT guidance about minimising cognitive load, creating ongoing debate about optimal timing and implementation.

Contemporary CLT research increasingly focuses on digital learning contexts. Van Merriënboer and Sweller's recent work (2020) explores how interactive simulations, virtual reality, and adaptive learning systems can manage cognitive load more dynamically than traditional materials.

Digital environments offer unique opportunities for adaptive cognitive load management. Educational software can monitor student performance and automatically adjust complexity, removing extraneous elements when learners struggle or adding challenge when they demonstrate mastery. Virtual laboratories can eliminate irrelevant visual details that might overload novice students whilst maintaining essential features for skill development.

However, digital tools also introduce new sources of extraneous load. Poor interface design, unnecessary animations, complex navigation systems, or distracting interactive elements can overwhelm working memory. Teachers must evaluate educational technology through a CLT lens, ensuring digital enhancements genuinely support rather than hinder learning. The seductive appeal of multimedia doesn't guarantee learning effectiveness.

Recent developments have also influenced assessment practices. Traditional tests often impose significant extraneous cognitive load through complex formatting, ambiguous instructions, or irrelevant context. CLT-informed assessment design focuses on reducing these barriers to allow genuine measurement of student understanding.

For example, rather than embedding mathematics problems within lengthy word problems featuring irrelevant details ("Sarah has 47 red marbles, 23 blue marbles, and 15 green marbles in her collection that she started on her birthday in June.."), assessments might present information more directly whilst still testing application skills ("Sarah has 47 red marbles, 23 blue marbles, and 15 green marbles. How many marbles in total?"). Similarly, providing reference sheets for formulas allows students to focus working memory on problem-solving processes rather than memorisation during high-stakes assessments.