High Functioning Autism

Discover what high-functioning autism means for teachers, learn to recognise hidden support needs, and find practical classroom strategies that help pupils thrive.

Discover what high-functioning autism means for teachers, learn to recognise hidden support needs, and find practical classroom strategies that help pupils thrive.

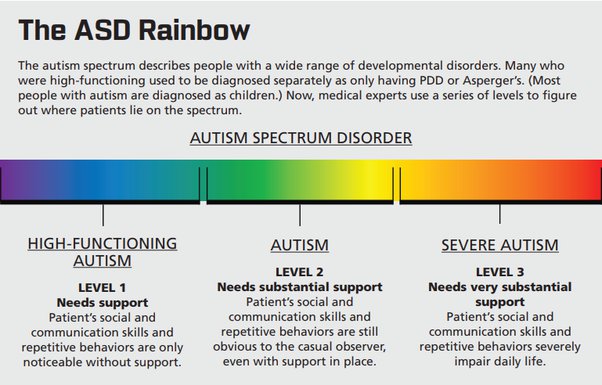

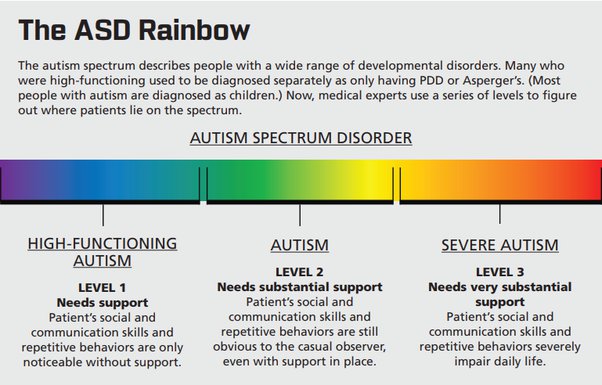

High functioning autism, often referred to within the context of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), presents a complex and multifaceted picture that challenges conventional understanding. According to the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders v.5 ( DSM-V), autism is characterised by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, along with restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities.

High functioning autism, specifically, is a term often applied to autistic individuals who may not exhibit intellectual disabilities but still face significant challenges in adaptive behaviours. This can include difficulties in understanding emotional sensitivity, managing sensory overload, and coping with emotional distress.

For example, a child with high functioning autism might excel academically but struggle with understanding social cues or experience intense anxiety in social situations. This form of autism in adults and children often requires a nuanced medical diagnosis, considering factors beyond the intelligence quotient (IQ).

High functioning autism is not merely a medical condition but a complex interplay of cognitive, emotional, and sensory experiences that requires a complete understanding.

A relevant statistic to consider is that approximately 1 in 54 childrenis diagnosed with ASD, reflecting the broad spectrum and diversity within this diagnosis.

Key Insights:

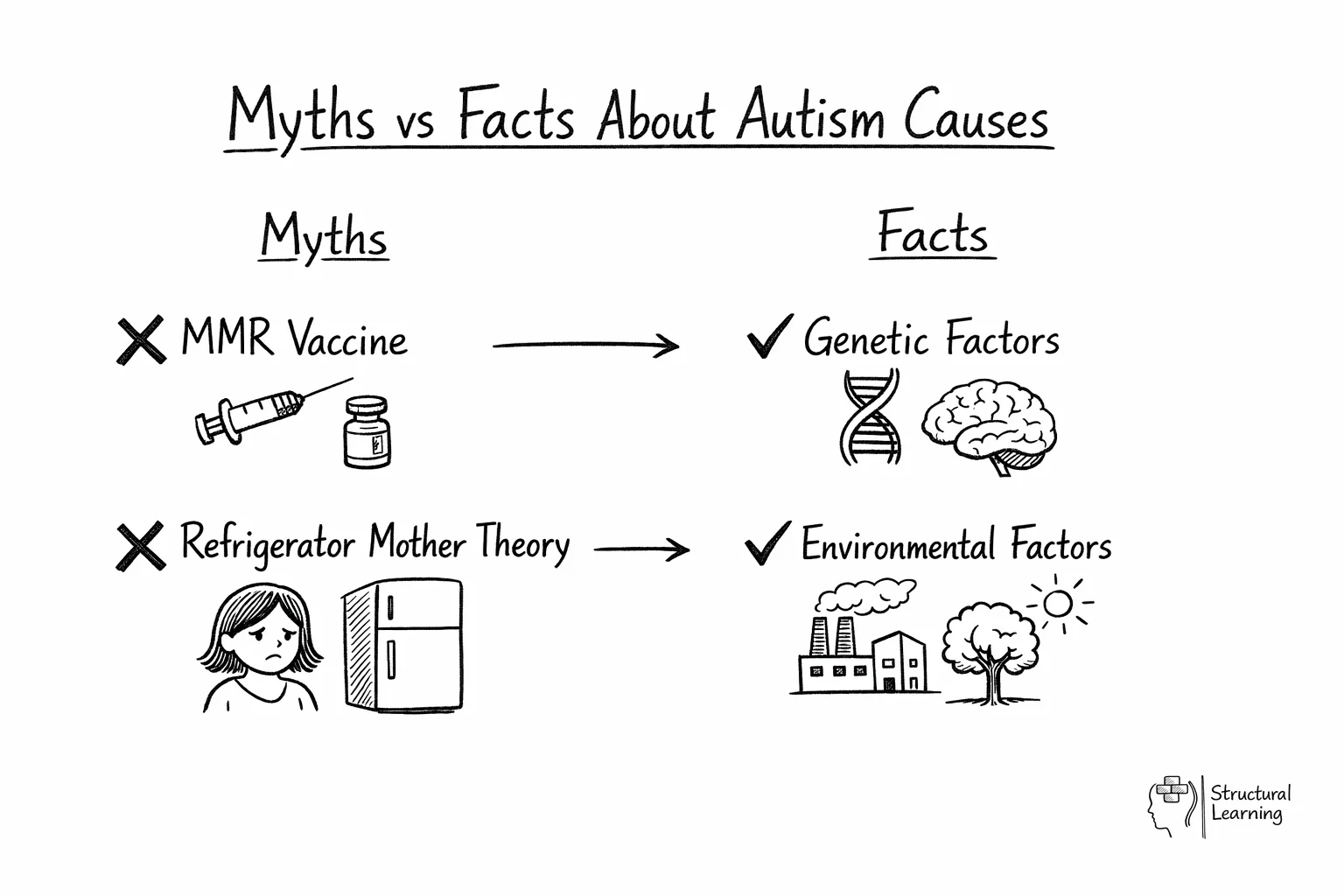

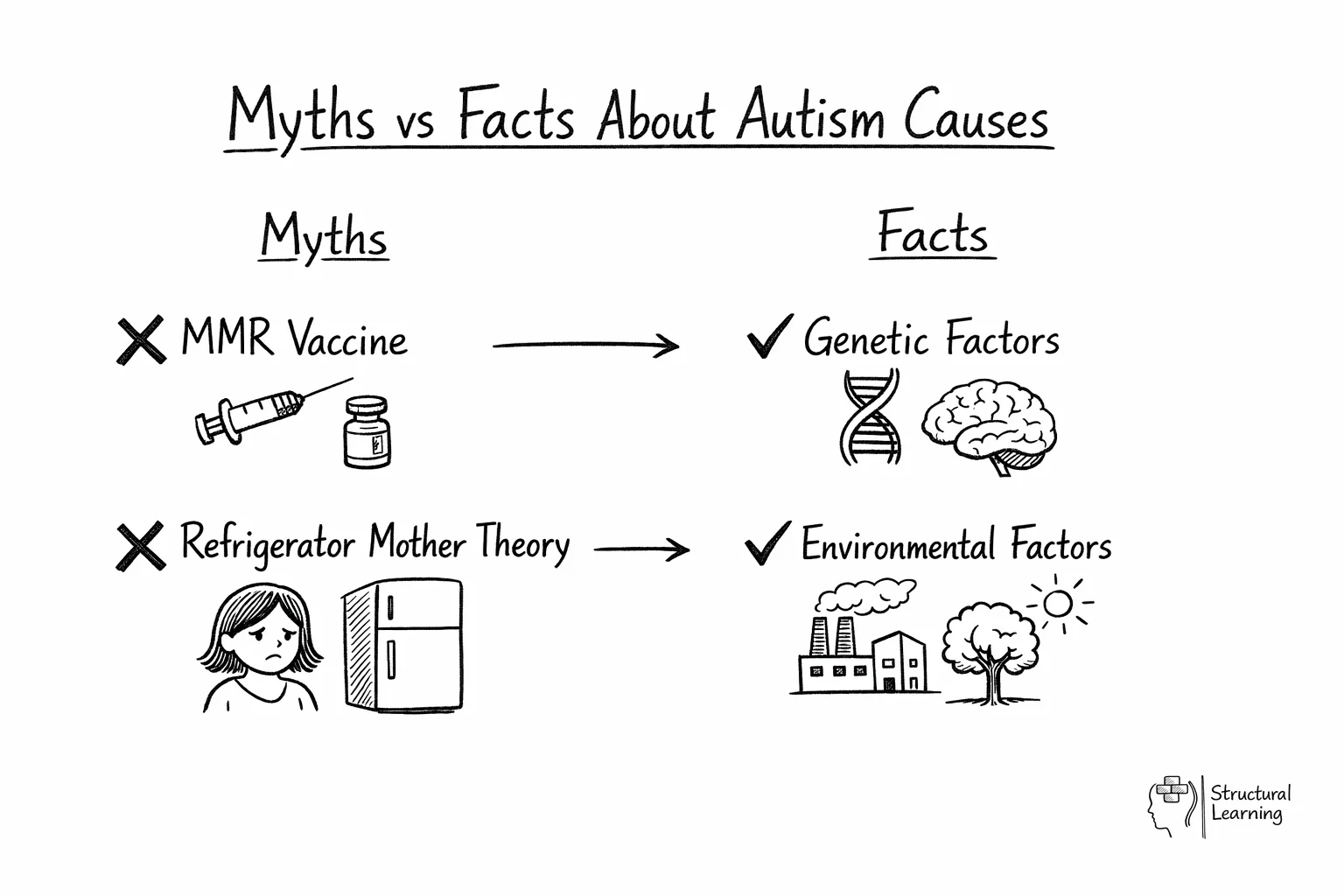

The exact cause of autism is still unknown, but it is widely thought that autism is thought to have a combination of genetic and environmental factors. There are a few genetic conditions where autism appears to be frequently co-morbid, including Fragile X Syndrome and Prader-Willi Syndrome, but most of the time, there is no known cause. It also appears that there is a genetic link as families with one autistic child are more likely to have another autistic child, though this does not mean that autism is hereditary.

In 1998, Andrew Wakefield and some of his colleagues published a study in the medical journal, The Lancet, where they suggested that the Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR) vaccine was linked to autism. Despite a small sample size (n=12), unstructured design and speculative conclusions, the study received a lot of publicity and led to a large number of parents not vaccinating their children. Shortly after the publication, The Lancet published various other studies that refuted the link between the vaccine and autism. Eventually, 10 out of the original 12 co-authors admitted that, "no causal link was established between MMR vaccine and autism as the data were insufficient".

The Lancet completely retracted the Wakefield et al. Paper in February 2010, admitting that several elements in the paper were incorrect, contrary to the findings of the earlier investigation. Wakefield et al. Were held guilty of ethical violations and scientific misrepresentation and also found guilty of deliberate fraud as they picked and chose the data that supported their case and falsified facts.

It was also once thought that autism was caused by a poor home environment or cold, stand-offish parenting styles. Kanner (1943) proposed the " refrigerator mother" theory which stated that, although Kanner believed that autism was probably innate in the child, he also noted an apparent coldness on the part of his patients' mothers and assumed that this added to the problem. Again, this theory has also been debunked and it is widely accepted that parenting style is not related to autism.

In earlier literature, you may have come across the term 'high-functioning autistic'. This is an out-dated term and realistically should no longer be used as people from the autistic community feel that this language diminishes the daily struggles they have to navigate.

It is the same for using terms like 'higher ability' and 'lower ability'; it is inflammatory language and can lead to assumptions being made about a child's current and future ability level. Understand how people who are autistic want to be addressed or spoken about, but for the purposes of this article, we will discuss in depth what it means to be 'high-functioning' and how their support needs may differ.

High-functioning autism isn't a clinical diagnosis but it is often referred to individuals who have lower support needs. The characteristics of a person who is high-functioning autistic are very similar to those who have Asperger Syndrome.

understand what high-functioning autism actually means in terms of symptoms and everyday life.

Creating meaningful support for pupils with high functioning autism requires understanding their unique learning profile. Whilst these pupils may excel academically, they often require specific accommodations to manage sensory sensitivities, social interactions, and executive functioning challenges. The key lies in recognising that high academic achievement does not equate to ease in all areas of school life.

Many pupils with high functioning autism experience heightened sensory sensitivity. Simple classroom modifications can significantly improve their learning environment. Consider providing noise-reducing headphones during independent work time, allowing pupils to sit away from fluorescent lighting, or creating a quiet corner with soft furnishings for sensory breaks. One Year 6 teacher in Manchester found that simply replacing harsh overhead lighting with softer LED strips reduced her autistic pupil's anxiety-related behaviours by approximately 40%.

Visual schedules prove particularly effective for these pupils. Display the day's timetable prominently and provide individual copies that pupils can tick off as activities are completed. This reduces anxiety about transitions and unexpected changes. When alterations to routine are necessary, provide advance warning wherever possible, explaining what will happen and why.

Social situations often present the greatest challenge for pupils with high functioning autism. Rather than expecting intuitive understanding of social rules, explicitly teach these skills through structured activities. Create social stories that break down common scenarios, such as joining a playground game or asking for help. Role-play exercises during PSHE lessons can help all pupils develop empathy whilst providing autistic pupils with concrete examples of social interactions.

Peer mentoring programmes have shown remarkable success in UK schools. Pairing autistic pupils with understanding classmates for specific activities, such as lunchtime clubs or paired reading, provides structured social opportunities without the overwhelming nature of unstructured playtime.

Effective partnership with parents is crucial for supporting pupils with high functioning autism. These parents often feel frustrated when their child's challenges are minimised due to strong academic performance. Establishing clear, regular communication channels helps build trust and ensures consistency between home and school strategies.

Begin parent meetings by acknowledging the pupil's strengths before discussing areas for development. Many parents report feeling that meetings focus solely on deficits, which can damage the collaborative relationship. Use specific examples rather than generalisations. Instead of saying "Jamie struggles socially", explain "Jamie finds it difficult to interpret facial expressions during group work, which sometimes leads to misunderstandings with peers".

Create a simple daily communication system, such as a home-school diary focusing on positives and any sensory or emotional challenges. This helps parents prepare for potential after-school meltdowns, which often result from pupils maintaining control throughout the school day. One Birmingham primary school introduced emoji cards that pupils could discreetly show teachers to indicate their emotional state, with results shared with parents via a simple app.

Meltdowns in pupils with high functioning autism differ fundamentally from tantrums. Whilst tantrums are goal-oriented behaviours, meltdowns represent a complete loss of emotional regulation, often triggered by sensory overload, unexpected changes, or accumulated stress. Understanding this distinction transforms how teachers respond to these challenging moments.

Prevention remains the most effective strategy. Watch for early warning signs such as increased stimming behaviours, withdrawal from activities, or heightened sensitivity to sensory input. When you notice these signs, offer a break before the situation escalates. Develop a personalised "escape plan" with the pupil and parents, identifying a safe space and calming strategies that work for that individual.

During a meltdown, prioritise safety over compliance. Reduce sensory input by dimming lights, minimising noise, and clearing space around the pupil. Avoid excessive talking or demands. Once the pupil has calmed, avoid immediate discussion of the incident. Many autistic individuals experience profound exhaustion following meltdowns and need recovery time before they can process what happened. Document triggers and effective responses to identify patterns and refine prevention strategies.

Supporting a pupil with high-functioning autism involves understanding their strengths and challenges. They may excel academically but struggle with social interactions, sensory sensitivities, or emotional regulation. Here are some strategies to consider:

Remember, every pupil with autism is unique, so tailor your approach to meet their individual needs. By providing a supportive and understanding environment, you can help pupils with high-functioning autism thrive academically, socially, and emotionally.

understanding high functioning autism requires moving beyond simple labels and recognising the complex interplay of strengths and challenges that individuals on the spectrum face. By focusing on individualised support, clear communication, and a deep understanding of sensory and emotional needs, educators can create inclusive environments where all pupils can thrive. The journey of understanding autism is ongoing, and continuous learning and adaptation are key to providing the best possible support.

Embracing neurodiversity and celebrating the unique talents of autistic pupils enriches the entire educational community. By developing empathy, patience, and a commitment to inclusive practices, we can helps these individuals to reach their full potential and contribute their unique perspectives to the world.

Recognising high-functioning autism in the classroom requires careful observation of subtle behavioural patterns that may initially appear as typical childhood quirks or learning difficulties. Autistic pupils often demonstrate exceptional abilities in specific subjects whilst struggling with social interactions, executive function, or sensory processing. Teachers might notice a student who excels academically but has difficulty with group work, becomes distressed by unexpected schedule changes, or displays repetitive behaviours during stressful periods.

Key indicators include rigid thinking patterns, where pupils may struggle to understand implied instructions or become upset when established routines are disrupted. Wing and Gould's research on the "triad of impairments" highlights how difficulties with social communication manifest differently in high-functioning individuals, often appearing as overly formal speech, literal interpretation of language, or challenges reading non-verbal cues. These students may also exhibit intense interests in specific topics, discussing them extensively regardless of social context.

Effective identification involves collaborative observation with colleagues and parents to establish patterns across different environments. Document specific examples of behaviours rather than making general assumptions, and consider how sensory factors in the classroom environment might influence a pupil's responses. When multiple indicators are present and impacting learning or social development, early discussion with your school's special educational needs coordinator can facilitate appropriate support strategies.

Sensory processing differences are fundamental to understanding how autistic pupils experience the classroom environment, often determining their ability to access learning effectively. Research by Ayres and subsequent occupational therapy studies demonstrates that many autistic learners experience either hypersensitivity or hyposensitivity to sensory input, creating significant barriers to concentration and participation. A flickering fluorescent light may cause overwhelming distress for one pupil, whilst another may seek intense sensory input through movement or touch to regulate their nervous system.

Creating a sensory-friendly classroom requires systematic consideration of multiple environmental factors. Lighting should be consistent and adjustable where possible, with natural light preferred over harsh fluorescents. Sound management through soft furnishings, designated quiet zones, and clear acoustic boundaries helps reduce auditory overwhelm. Visual clutter should be minimised on walls and displays, whilst providing defined spaces for different activities helps autistic pupils predict and navigate their environment successfully.

Practical modifications can be implemented immediately with minimal disruption to other learners. Consider offering alternative seating options such as cushions or standing desks, providing noise-cancelling headphones during independent work, and establishing clear sensory break protocols. Regular consultation with pupils about their sensory needs demonstrates respect for their self-advocacy whilst building essential environmental awareness skills for their future educational journey.

Autistic pupils with high-functioning autism often display a distinctive academic profile characterised by significant strengths alongside specific challenges. These students frequently excel in areas requiring systematic thinking, pattern recognition, and detailed analysis, particularly in subjects like mathematics, science, and technology. Tony Attwood's research highlights how many autistic learners demonstrate exceptional abilities in logical reasoning and can achieve remarkable depth of knowledge in their areas of interest.

However, executive functioning difficulties can significantly impact academic performance across all subjects. Challenges with organisation, time management, and task switching often mask intellectual capabilities, whilst sensory processing differences may affect concentration and participation. Temple Grandin's work emphasises how traditional teaching methods may not align with autistic thinking patterns, potentially creating barriers to demonstrating true academic potential.

Effective classroom support involves using individual strengths whilst providing targeted scaffolding for areas of difficulty. Practical strategies include offering visual schedules, breaking complex tasks into manageable steps, and allowing extra processing time for instructions. Teachers should consider providing alternative assessment methods that accommodate different learning styles, such as written responses instead of verbal presentations, enabling autistic pupils to demonstrate their knowledge more effectively.

Developing social skills in pupils with high-functioning autism requires systematic, explicit instruction rather than expecting these abilities to emerge naturally through peer interaction. Carol Gray's Social Stories™ methodology demonstrates how structured narratives can effectively teach social expectations and appropriate responses in specific situations. These evidence-based approaches work by breaking down complex social scenarios into manageable components, allowing autistic pupils to understand the unwritten rules that neurotypical children instinctively grasp.

Successful peer interactions often depend on creating structured opportunities within the classroom environment. Teachers should establish clear social scripts for common situations such as group work, playground activities, and collaborative learning tasks. Visual supports, including social cue cards and interaction prompts, help pupils navigate these situations independently. Additionally, implementing peer buddy systems or circle time discussions can creates understanding amongst all pupils whilst providing natural opportunities for social skill practice.

Regular assessment of social progress ensures interventions remain effective and responsive to individual needs. Consider establishing specific social learning objectives within Individual Education Plans, focusing on measurable goals such as initiating conversations, taking turns in discussions, or recognising emotional cues. Create quiet retreat spaces where pupils can decompress when social demands become overwhelming, recognising that social interaction can be cognitively exhausting for autistic learners.

High functioning autism, often referred to within the context of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), presents a complex and multifaceted picture that challenges conventional understanding. According to the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders v.5 ( DSM-V), autism is characterised by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, along with restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities.

High functioning autism, specifically, is a term often applied to autistic individuals who may not exhibit intellectual disabilities but still face significant challenges in adaptive behaviours. This can include difficulties in understanding emotional sensitivity, managing sensory overload, and coping with emotional distress.

For example, a child with high functioning autism might excel academically but struggle with understanding social cues or experience intense anxiety in social situations. This form of autism in adults and children often requires a nuanced medical diagnosis, considering factors beyond the intelligence quotient (IQ).

High functioning autism is not merely a medical condition but a complex interplay of cognitive, emotional, and sensory experiences that requires a complete understanding.

A relevant statistic to consider is that approximately 1 in 54 childrenis diagnosed with ASD, reflecting the broad spectrum and diversity within this diagnosis.

Key Insights:

The exact cause of autism is still unknown, but it is widely thought that autism is thought to have a combination of genetic and environmental factors. There are a few genetic conditions where autism appears to be frequently co-morbid, including Fragile X Syndrome and Prader-Willi Syndrome, but most of the time, there is no known cause. It also appears that there is a genetic link as families with one autistic child are more likely to have another autistic child, though this does not mean that autism is hereditary.

In 1998, Andrew Wakefield and some of his colleagues published a study in the medical journal, The Lancet, where they suggested that the Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR) vaccine was linked to autism. Despite a small sample size (n=12), unstructured design and speculative conclusions, the study received a lot of publicity and led to a large number of parents not vaccinating their children. Shortly after the publication, The Lancet published various other studies that refuted the link between the vaccine and autism. Eventually, 10 out of the original 12 co-authors admitted that, "no causal link was established between MMR vaccine and autism as the data were insufficient".

The Lancet completely retracted the Wakefield et al. Paper in February 2010, admitting that several elements in the paper were incorrect, contrary to the findings of the earlier investigation. Wakefield et al. Were held guilty of ethical violations and scientific misrepresentation and also found guilty of deliberate fraud as they picked and chose the data that supported their case and falsified facts.

It was also once thought that autism was caused by a poor home environment or cold, stand-offish parenting styles. Kanner (1943) proposed the " refrigerator mother" theory which stated that, although Kanner believed that autism was probably innate in the child, he also noted an apparent coldness on the part of his patients' mothers and assumed that this added to the problem. Again, this theory has also been debunked and it is widely accepted that parenting style is not related to autism.

In earlier literature, you may have come across the term 'high-functioning autistic'. This is an out-dated term and realistically should no longer be used as people from the autistic community feel that this language diminishes the daily struggles they have to navigate.

It is the same for using terms like 'higher ability' and 'lower ability'; it is inflammatory language and can lead to assumptions being made about a child's current and future ability level. Understand how people who are autistic want to be addressed or spoken about, but for the purposes of this article, we will discuss in depth what it means to be 'high-functioning' and how their support needs may differ.

High-functioning autism isn't a clinical diagnosis but it is often referred to individuals who have lower support needs. The characteristics of a person who is high-functioning autistic are very similar to those who have Asperger Syndrome.

understand what high-functioning autism actually means in terms of symptoms and everyday life.

Creating meaningful support for pupils with high functioning autism requires understanding their unique learning profile. Whilst these pupils may excel academically, they often require specific accommodations to manage sensory sensitivities, social interactions, and executive functioning challenges. The key lies in recognising that high academic achievement does not equate to ease in all areas of school life.

Many pupils with high functioning autism experience heightened sensory sensitivity. Simple classroom modifications can significantly improve their learning environment. Consider providing noise-reducing headphones during independent work time, allowing pupils to sit away from fluorescent lighting, or creating a quiet corner with soft furnishings for sensory breaks. One Year 6 teacher in Manchester found that simply replacing harsh overhead lighting with softer LED strips reduced her autistic pupil's anxiety-related behaviours by approximately 40%.

Visual schedules prove particularly effective for these pupils. Display the day's timetable prominently and provide individual copies that pupils can tick off as activities are completed. This reduces anxiety about transitions and unexpected changes. When alterations to routine are necessary, provide advance warning wherever possible, explaining what will happen and why.

Social situations often present the greatest challenge for pupils with high functioning autism. Rather than expecting intuitive understanding of social rules, explicitly teach these skills through structured activities. Create social stories that break down common scenarios, such as joining a playground game or asking for help. Role-play exercises during PSHE lessons can help all pupils develop empathy whilst providing autistic pupils with concrete examples of social interactions.

Peer mentoring programmes have shown remarkable success in UK schools. Pairing autistic pupils with understanding classmates for specific activities, such as lunchtime clubs or paired reading, provides structured social opportunities without the overwhelming nature of unstructured playtime.

Effective partnership with parents is crucial for supporting pupils with high functioning autism. These parents often feel frustrated when their child's challenges are minimised due to strong academic performance. Establishing clear, regular communication channels helps build trust and ensures consistency between home and school strategies.

Begin parent meetings by acknowledging the pupil's strengths before discussing areas for development. Many parents report feeling that meetings focus solely on deficits, which can damage the collaborative relationship. Use specific examples rather than generalisations. Instead of saying "Jamie struggles socially", explain "Jamie finds it difficult to interpret facial expressions during group work, which sometimes leads to misunderstandings with peers".

Create a simple daily communication system, such as a home-school diary focusing on positives and any sensory or emotional challenges. This helps parents prepare for potential after-school meltdowns, which often result from pupils maintaining control throughout the school day. One Birmingham primary school introduced emoji cards that pupils could discreetly show teachers to indicate their emotional state, with results shared with parents via a simple app.

Meltdowns in pupils with high functioning autism differ fundamentally from tantrums. Whilst tantrums are goal-oriented behaviours, meltdowns represent a complete loss of emotional regulation, often triggered by sensory overload, unexpected changes, or accumulated stress. Understanding this distinction transforms how teachers respond to these challenging moments.

Prevention remains the most effective strategy. Watch for early warning signs such as increased stimming behaviours, withdrawal from activities, or heightened sensitivity to sensory input. When you notice these signs, offer a break before the situation escalates. Develop a personalised "escape plan" with the pupil and parents, identifying a safe space and calming strategies that work for that individual.

During a meltdown, prioritise safety over compliance. Reduce sensory input by dimming lights, minimising noise, and clearing space around the pupil. Avoid excessive talking or demands. Once the pupil has calmed, avoid immediate discussion of the incident. Many autistic individuals experience profound exhaustion following meltdowns and need recovery time before they can process what happened. Document triggers and effective responses to identify patterns and refine prevention strategies.

Supporting a pupil with high-functioning autism involves understanding their strengths and challenges. They may excel academically but struggle with social interactions, sensory sensitivities, or emotional regulation. Here are some strategies to consider:

Remember, every pupil with autism is unique, so tailor your approach to meet their individual needs. By providing a supportive and understanding environment, you can help pupils with high-functioning autism thrive academically, socially, and emotionally.

understanding high functioning autism requires moving beyond simple labels and recognising the complex interplay of strengths and challenges that individuals on the spectrum face. By focusing on individualised support, clear communication, and a deep understanding of sensory and emotional needs, educators can create inclusive environments where all pupils can thrive. The journey of understanding autism is ongoing, and continuous learning and adaptation are key to providing the best possible support.

Embracing neurodiversity and celebrating the unique talents of autistic pupils enriches the entire educational community. By developing empathy, patience, and a commitment to inclusive practices, we can helps these individuals to reach their full potential and contribute their unique perspectives to the world.

Recognising high-functioning autism in the classroom requires careful observation of subtle behavioural patterns that may initially appear as typical childhood quirks or learning difficulties. Autistic pupils often demonstrate exceptional abilities in specific subjects whilst struggling with social interactions, executive function, or sensory processing. Teachers might notice a student who excels academically but has difficulty with group work, becomes distressed by unexpected schedule changes, or displays repetitive behaviours during stressful periods.

Key indicators include rigid thinking patterns, where pupils may struggle to understand implied instructions or become upset when established routines are disrupted. Wing and Gould's research on the "triad of impairments" highlights how difficulties with social communication manifest differently in high-functioning individuals, often appearing as overly formal speech, literal interpretation of language, or challenges reading non-verbal cues. These students may also exhibit intense interests in specific topics, discussing them extensively regardless of social context.

Effective identification involves collaborative observation with colleagues and parents to establish patterns across different environments. Document specific examples of behaviours rather than making general assumptions, and consider how sensory factors in the classroom environment might influence a pupil's responses. When multiple indicators are present and impacting learning or social development, early discussion with your school's special educational needs coordinator can facilitate appropriate support strategies.

Sensory processing differences are fundamental to understanding how autistic pupils experience the classroom environment, often determining their ability to access learning effectively. Research by Ayres and subsequent occupational therapy studies demonstrates that many autistic learners experience either hypersensitivity or hyposensitivity to sensory input, creating significant barriers to concentration and participation. A flickering fluorescent light may cause overwhelming distress for one pupil, whilst another may seek intense sensory input through movement or touch to regulate their nervous system.

Creating a sensory-friendly classroom requires systematic consideration of multiple environmental factors. Lighting should be consistent and adjustable where possible, with natural light preferred over harsh fluorescents. Sound management through soft furnishings, designated quiet zones, and clear acoustic boundaries helps reduce auditory overwhelm. Visual clutter should be minimised on walls and displays, whilst providing defined spaces for different activities helps autistic pupils predict and navigate their environment successfully.

Practical modifications can be implemented immediately with minimal disruption to other learners. Consider offering alternative seating options such as cushions or standing desks, providing noise-cancelling headphones during independent work, and establishing clear sensory break protocols. Regular consultation with pupils about their sensory needs demonstrates respect for their self-advocacy whilst building essential environmental awareness skills for their future educational journey.

Autistic pupils with high-functioning autism often display a distinctive academic profile characterised by significant strengths alongside specific challenges. These students frequently excel in areas requiring systematic thinking, pattern recognition, and detailed analysis, particularly in subjects like mathematics, science, and technology. Tony Attwood's research highlights how many autistic learners demonstrate exceptional abilities in logical reasoning and can achieve remarkable depth of knowledge in their areas of interest.

However, executive functioning difficulties can significantly impact academic performance across all subjects. Challenges with organisation, time management, and task switching often mask intellectual capabilities, whilst sensory processing differences may affect concentration and participation. Temple Grandin's work emphasises how traditional teaching methods may not align with autistic thinking patterns, potentially creating barriers to demonstrating true academic potential.

Effective classroom support involves using individual strengths whilst providing targeted scaffolding for areas of difficulty. Practical strategies include offering visual schedules, breaking complex tasks into manageable steps, and allowing extra processing time for instructions. Teachers should consider providing alternative assessment methods that accommodate different learning styles, such as written responses instead of verbal presentations, enabling autistic pupils to demonstrate their knowledge more effectively.

Developing social skills in pupils with high-functioning autism requires systematic, explicit instruction rather than expecting these abilities to emerge naturally through peer interaction. Carol Gray's Social Stories™ methodology demonstrates how structured narratives can effectively teach social expectations and appropriate responses in specific situations. These evidence-based approaches work by breaking down complex social scenarios into manageable components, allowing autistic pupils to understand the unwritten rules that neurotypical children instinctively grasp.

Successful peer interactions often depend on creating structured opportunities within the classroom environment. Teachers should establish clear social scripts for common situations such as group work, playground activities, and collaborative learning tasks. Visual supports, including social cue cards and interaction prompts, help pupils navigate these situations independently. Additionally, implementing peer buddy systems or circle time discussions can creates understanding amongst all pupils whilst providing natural opportunities for social skill practice.

Regular assessment of social progress ensures interventions remain effective and responsive to individual needs. Consider establishing specific social learning objectives within Individual Education Plans, focusing on measurable goals such as initiating conversations, taking turns in discussions, or recognising emotional cues. Create quiet retreat spaces where pupils can decompress when social demands become overwhelming, recognising that social interaction can be cognitively exhausting for autistic learners.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/high-functioning-autism#article","headline":"High Functioning Autism","description":"A teacher's introduction to high-functioning autism and what classroom support might be useful.","datePublished":"2022-08-18T16:29:12.919Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/high-functioning-autism"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69690922325dce018920f658_6969091dc8dada17c088ada0_high-functioning-autism-illustration.webp","wordCount":3953},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/high-functioning-autism#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"High Functioning Autism","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/high-functioning-autism"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is high functioning autism?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"High functioning autism, often referred to within the context of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), presents a complex and multifaceted picture that challenges conventional understanding. According to the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders v.5 ( DSM-V), autism is characterised by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, along with restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the causes of autism spectrum disorder?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The exact cause of autism is still unknown, but it is widely thought that autism is thought to have a combination of genetic and environmental factors. There are a few genetic conditions where autism appears to be frequently co-morbid, including Fragile X Syndrome and Prader-Willi Syndrome, but most of the time, there is no known cause. It also appears that there is a genetic link as families with one autistic child are more likely to have another autistic child, though this does not mean that a"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What does it mean to be 'high-functioning' autistic?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"In earlier literature, you may have come across the term 'high-functioning autistic'. This is an out-dated term and realistically should no longer be used as people from the autistic community feel that this language diminishes the daily struggles they have to navigate."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Can Teachers Create Effective Support Strategies for Pupils with High Functioning Autism?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Creating meaningful support for pupils with high functioning autism requires understanding their unique learning profile. Whilst these pupils may excel academically, they often require specific accommodations to manage sensory sensitivities, social interactions, and executive functioning challenges. The key lies in recognising that high academic achievement does not equate to ease in all areas of school life."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Communication Strategies Work Best with Parents of Autistic Pupils?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Effective partnership with parents is crucial for supporting pupils with high functioning autism. These parents often feel frustrated when their child's challenges are minimised due to strong academic performance. Establishing clear, regular communication channels helps build trust and ensures consistency between home and school strategies."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why Do Meltdowns Occur and How Should Teachers Respond?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Meltdowns in pupils with high functioning autism differ fundamentally from tantrums. Whilst tantrums are goal-oriented behaviours, meltdowns represent a complete loss of emotional regulation, often triggered by sensory overload, unexpected changes, or accumulated stress. Understanding this distinction transforms how teachers respond to these challenging moments."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can I best support a pupil who is high-functioning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Supporting a pupil with high-functioning autism involves understanding their strengths and challenges. They may excel academically but struggle with social interactions, sensory sensitivities, or emotional regulation. Here are some strategies to consider:"}}]}]}