Effective questioning in teaching

Master effective classroom questioning techniques with our guide, designed to engage students and stimulate critical thinking.

Master effective classroom questioning techniques with our guide, designed to engage students and stimulate critical thinking.

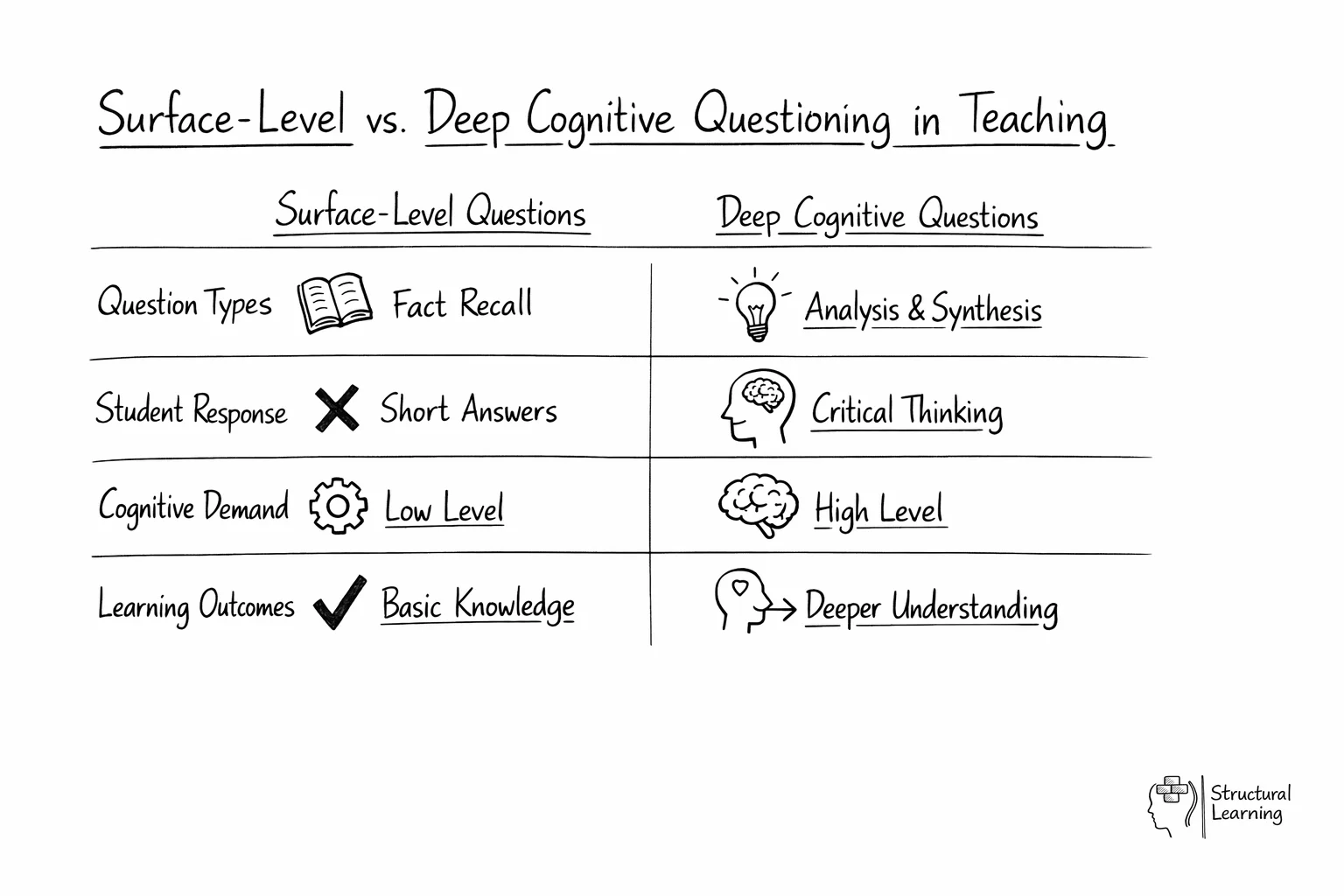

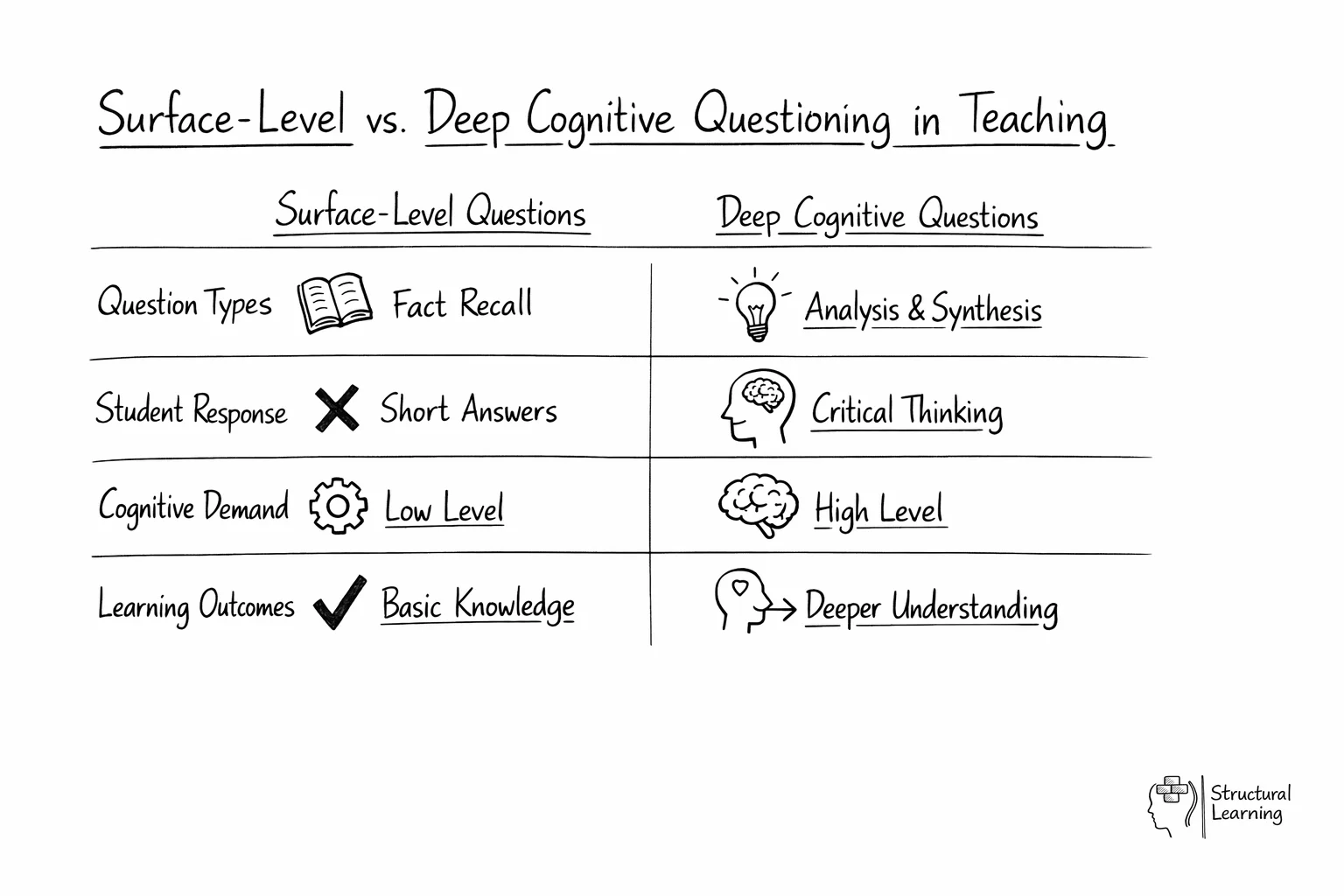

Teachers in 2025 face a persistent challenge. They ask questions (AI-generated hinge questions) but rarely use them to stretch student thinking. Questions often fail to engage because they stay at surface level. The gap between checking facts and developing deep understanding remains wide.

Teacher questioning refers to the deliberate use of questions to assess understanding, promote thinking, and guide learning. Too many classroom questions focus on recall. They check if students remember information rather than whether they can apply, analyse, or evaluate it. This challenge is particularly evident in subjects like mathematics, where examination questioning in maths can transform procedural learning into conceptual understanding.

Build better questions with question stems, examples by subject, and the Question Upgrader tool.

From Structural Learning, structural-learning.com

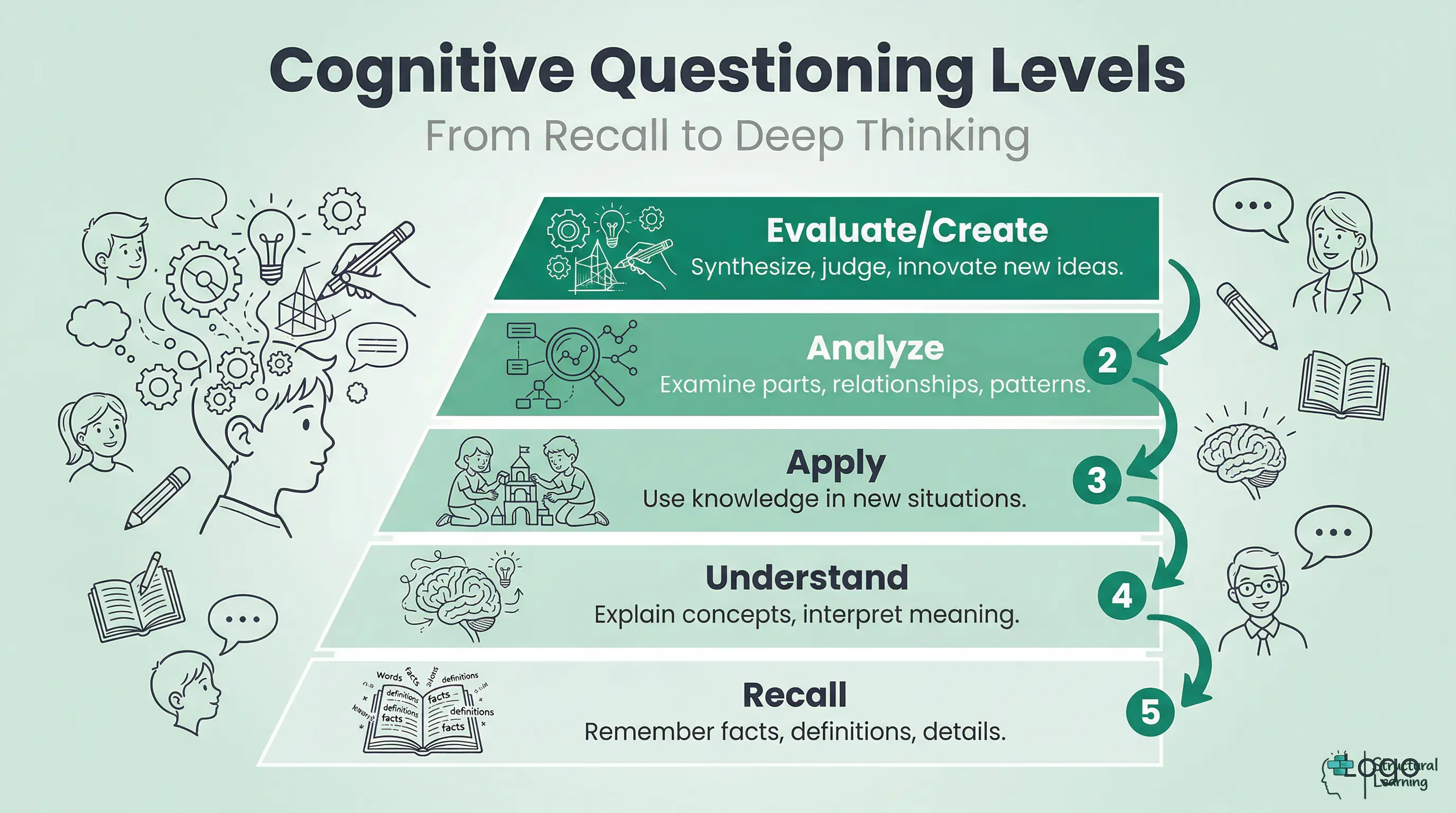

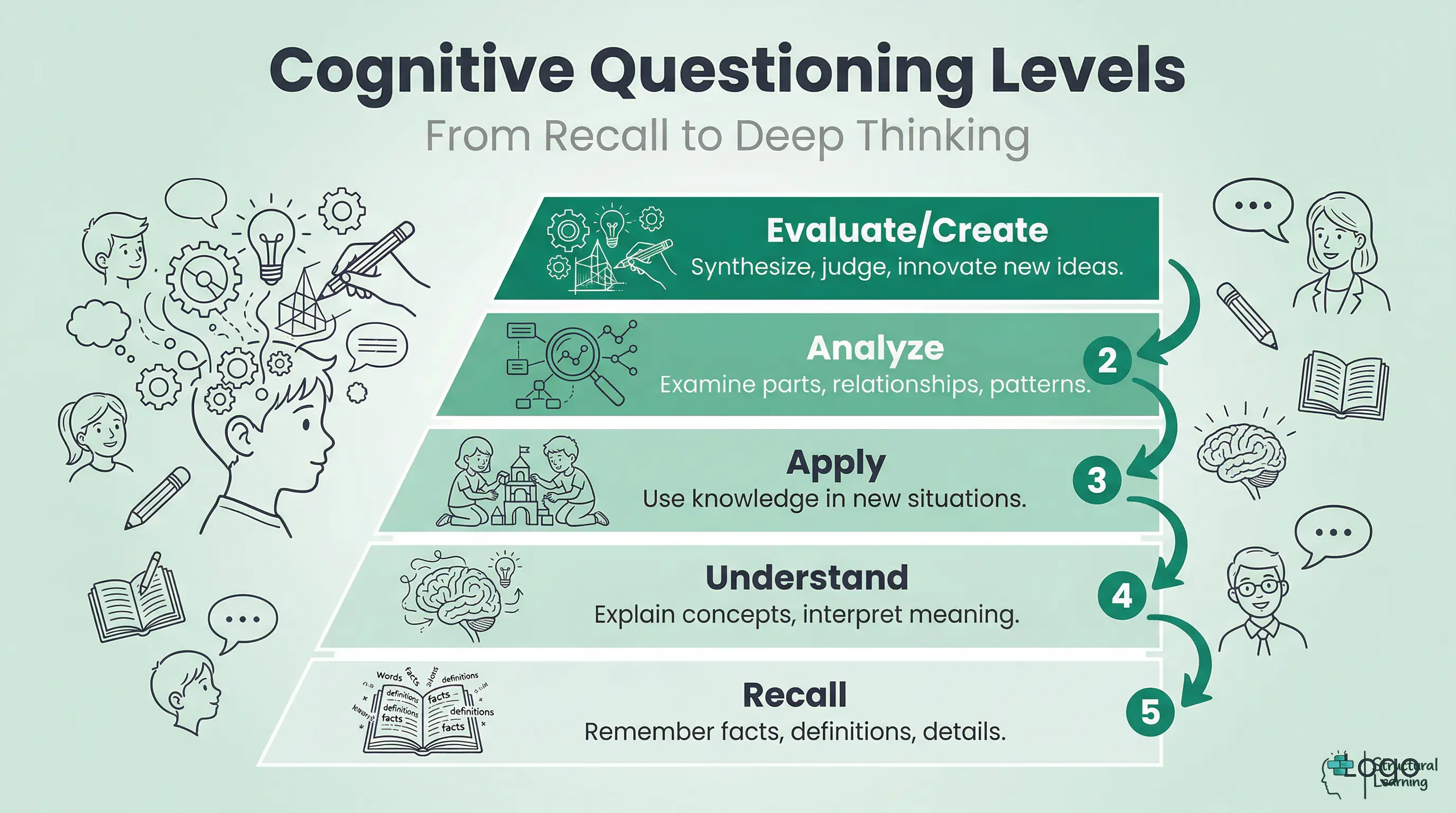

Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive skills provides a useful framework. The revised taxonomy identifies si x levels of cognitive learning. Each level requires different thinking processes. Classification taxonomies have evolved to guide teacher questioning, from early work by Krathwohl (1964) and Wilen (1986) to Morgan and Saxton (1991). Hannel and Hannel (2005) demonstrated how teacher questions promote student engagement. Dekker-Groen (2015) examined how sequences of teacher and student questions influence classroom dialogue, emphasising the role of questioning to develop oracy.

These frameworks help, but they need careful application. Each classroom situation is unique. Not every student needs questions at multiple cognitive levels in every lesson.

Schons's (1983) model of reflection offers three critical questions for teachers:

Being able to categorise questions is a starting point for improving practice.

Questions are integral to classroom life. They form a core part of every teacher's pedagogical repertoire. Yet they often serve merely to check facts. Black et al. (2003) stated that higher-order probing questions enable teachers to be better informed about student progress. This knowledge leads to more individualized and differentiated support. Questions that probe for deeper meaning creates critical thinking skills. They encourage the flexible learners and problem-solvers needed in modern classrooms.

Questioning forces students to think critically about content. When teachers ask questions, students must process information and generate solutions. They cannot rely on memorized responses.

Teacher questions function as feedback mechanisms. Feedback allows teachers to determine whether their methods work. This matters particularly in subjects like mathematics, where problems can be solved through trial and error. Rather than simply providing correct answers, teachers should offer multiple choices and let students determine which solution works.

This approach is called open-ended questioning. It requires students to use critical thinking and problem-solving abilities. Open-ended questioning appears across science, social studies, and language arts lessons.

Choose questions based on your learning objective and students' current understanding level. Use recall questions to check foundational knowledge, then progress to application and analysis questions to deepen thinking. Match question complexity to student readiness while gradually increasing cognitive demand throughout the lesson.

Creating effective cognitive questions is simpler than it sounds. Some classrooms display question walls as reference points for quick thinking. A question matrix can help generate divergent questions both in the moment and during planning.

The Thinking Framework thinking skills cards provide a practical tool for generating questions on the spot. These 30 cards are organised into five colored categories: Green (Extract..), Blue (Categorise..), Yellow (Explain..), Orange (Target Vocabulary..), and Red (Combine..). Each card prompts a specific type of cognitive response. Teachers can select a card that matches their learning objective and use it to frame questions during a lesson. Students can also use these cards to generate questions for peers, turning questioning into a collaborative learning activity rather than a teacher-led exercise.

The key to eliciting comprehensive student responses is focusing on questions from the bottom right corner of a cognitive matrix. Questions beginning with "Why did..?" or "How might..?" produce answers requiring detailed explanation. Complex questions demand more student thinking than simple yes-no responses.

Tom Sherrington recently argued that depth of knowledge shows in the ability to explain something. This type of deep learning emerges through sophisticated student responses. These responses are nurtured and articulated through well-designed cognitive questions.

Within the Thinking Framework, Socratic questioning is categorised according to desired learning outcomes. Teachers think about the learning experience and consider how they want learners to think. The cognitive response you want to nurture determines the way you talk about content.

This dialogic approach describes learning through talk, not learning to talk. The Thinking Framework includes response structures that equip teachers with talk moves that shift from simple recall to evaluative judgement.

Effective questioning hinges on careful planning and execution. Consider these strategies to enhance your questioning techniques:

The goal is to ask questions and to creates a classroom environment where questioning is a tool for deep learning and critical thinking.

Consider using visual aids, such as diagrams or mind maps, to support questioning. These tools can help students organise their thoughts and provide more structured responses. Regularly assess your questioning strategies through reflection and feedback from colleagues or students. Continuously refine your approach to meet the evolving needs of your learners.

By adopting these strategies, teachers can transform their classrooms into vibrant hubs of inquiry, where students actively engage with content and develop the critical thinking skills needed for success in the 21st century.

Effective questioning is more than just asking questions; it's about creating a culture of inquiry that promotes deep learning. By shifting from surface-level recall to higher-order thinking, teachers can helps students to become critical thinkers and problem-solvers.

Embracing strategies such as the Question Matrix, thoughtful wait time, and the Pause, Pounce, Bounce technique, educators can transform their classrooms into environments where students actively engage with content and develop the skills necessary to thrive in an ever-changing world. The power of questioning lies in the answers it elicits and in the thinking it provokes.

Wait time represents one of the most powerful yet underutilised strategies in UK classrooms. Mary Budd Rowe's groundbreaking research revealed that teachers typically wait less than one second after asking a question before calling for an answer. This rushed approach prevents deeper thinking and excludes students who need processing time. Rowe identified two critical wait periods: Wait Time 1 (after asking the question) and Wait Time 2 (after a student responds). Extending both to 3-5 seconds transforms classroom dynamics dramatically.

The benefits of proper wait time extend beyond individual thinking. Research shows that when teachers implement adequate wait time, student responses become longer and more thoughtful, participation increases across all ability levels, and the quality of discourse improves significantly. In a Year 8 science lesson exploring photosynthesis, rather than accepting the first hand raised after asking "Why do plants need different types of light?", effective teachers pause, scan the room, and allow thinking time before selecting respondents strategically.

Implementing wait time requires deliberate practice and systems. Many teachers find success using silent counting techniques or physical cues like placing a hand on their desk during wait periods. The "no hands up" approach works particularly well with extended wait time, as it removes the pressure for immediate responses. For younger pupils in KS1 and KS2, visual countdown timers or "thinking pose" instructions help establish wait time routines. Secondary teachers often combine wait time with think-pair-share structures, allowing students to process individually before discussing with partners.

Different question types require adjusted wait times. Factual recall questions may need only 1-2 seconds, whilst analytical or evaluative questions about GCSE texts or A-Level concepts benefit from 5-7 seconds minimum. Teachers working with EAL students or those with processing difficulties should extend wait times further, recognising that language translation and cognitive processing occur simultaneously. The key lies in communicating expectations clearly whilst maintaining the productive tension that encourages deep thinking.

Mathematics questioning in UK classrooms requires a fundamental shift from procedural verification to conceptual exploration. Instead of asking "What is 15% of 80?", effective maths teachers pose questions like "How many different ways can you calculate 15% of 80, and which method reveals the most about percentage relationships?" This approach aligns with the mastery curriculum emphasis on depth over breadth. Key Stage 3 algebra lessons benefit from questions such as "What would happen if we changed this coefficient?" rather than simply "Solve for x". A-Level mathematics teachers use questioning to expose mathematical reasoning: "Explain why integration and differentiation are inverse processes using this specific example."

English literature questioning moves beyond comprehension checks toward analytical thinking. Rather than "What happens in Act 2?", GCSE English teachers ask "How does Shakespeare use Lady Macbeth's language in Act 2 to reveal her changing psychological state?" Effective literature questioning often employs the AP3 framework (Author's Purpose, Perspective, and Presentation) familiar to many UK English departments. For younger readers in KS2, questions like "What do you notice about how the author describes the setting when the character feels afraid?" develop critical reading skills progressively.

Science questioning emphasises investigative thinking and hypothesis formation. Primary science benefits from "What if?" and "How could we test?" questions that encourage scientific method thinking. "What would happen if we changed the angle of this ramp?" transforms a simple forces demonstration into inquiry-based learning. Secondary science teachers use questioning to develop practical investigation skills required for GCSE practicals: "Based on your observations, what relationship do you predict between temperature and reaction rate?" Chemistry teachers particularly benefit from questions that link molecular behaviour to observable phenomena.

History questioning develops source evaluation and contextual thinking skills essential for GCSE and A-Level success. Instead of "When did World War I begin?", effective history teachers ask "What can this propaganda poster tell us about civilian attitudes in 1916, and what might it not reveal?" Geography teachers combine factual knowledge with analytical skills through questions like "How might climate change affect this coastal management strategy differently in 20 years?" These subject-specific approaches ensure questioning serves both knowledge building and skill development simultaneously.

Bloom's Taxonomy provides a structured framework for questioning that moves students from basic know ledge recall to higher-order thinking skills. The six progressive levels (Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analysing, Evaluating, and Creating) help teachers design questions that develop increasingly complex cognitive skills.

Approximately 80 per cent of all questions teachers ask are factual, literal, or knowledge-based, resulting in classrooms where little creative thinking takes place. Bloom's Taxonomy addresses this problem by providing explicit question stems for each cognitive level. Rather than focusing on rote memorisation, the taxonomy encourages students to analyse, evaluate, and create, developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills that extend far beyond simple recall.

At the Remembering level, questions prompt retrieval of basic facts: 'What is..?', 'When did..?', 'Who were..?'. Understanding questions require explanation: 'How would you summarise..?', 'What is the main idea of..?', 'Can you explain this in your own words?'. These foundational levels establish baseline knowledge necessary for more complex thinking.

Applying questions bridge theory and practice: 'How would you use..?', 'What examples can you find to..?', 'How would you solve..?'. Analysing questions require breaking concepts into component parts: 'What evidence can you identify..?', 'How do these ideas compare?', 'What is the relationship between..?'. These mid-level questions develop students' capacity to work with information rather than simply receive it.

Evaluating questions demand judgment based on criteria: 'What is your opinion of..?', 'How would you prioritise..?', 'What choice would you have made..?'. Creating questions, at the highest level, require synthesis of knowledge to produce something new: 'What would happen if..?', 'Can you design a..?', 'How could you improve..?'. According to García, Pacheco, and Aguilar (2018), incorporating Bloom's Taxonomy into lesson planning led to a 19.6 per cent improvement in students' academic performance.

Teachers can support their own development by colour-coding question stems on index cards for each level, keeping these cards on a key ring in different learning centres or in pockets for quick reference. Many educators assume primary-level students cannot handle higher-level questions, but challenging all students through higher-order questioning represents one of the best ways to stimulate learning and enhance brain development, regardless of age. The goal is to build students' thinking muscles gradually, creating classroom environments where students feel comfortable making mistakes as they grapple with increasingly complex questions.

Wait time (the pause between asking a question and soliciting an answer) typically averages 0.7 to 1.5 seconds in classrooms, but extending this pause to 3-5 seconds produces remarkable improvements in student engagement, response quality, and critical thinking. Two distinct types exist: Wait Time 1 (after the question) and Wait Time 2 (after a student response).

In 1972, Mary Budd Rowe coined the phrase 'wait time' after discovering that teachers typically waited less than two seconds before speaking after asking a question. This rushed pace prevents students from formulating thoughtful responses. Robert Stahl later expanded this concept by coining 'think time', emphasising that these pauses provide uninterrupted silence for both teachers and students to reflect on and process their thoughts, feelings, and reactions.

When teachers extend wait time beyond three seconds, significant positive changes occur in both student and teacher discourse. Students engage more actively in class through increased student talk and questions, longer responses, and more idea exchange between peers. They also exhibit enhanced critical thinking, offering higher-quality utterances. Specifically, the number of unsolicited responses increases (even from students reluctant to speak), the number of appropriate answers increases, student responses become lengthier and delivered in full correct sentences, and student confidence rises.

Wait time provides necessary opportunity for student brains to organise the complex tasks involved in thinking and reflecting after a question is asked. Even the fastest student brain needs time to hear the teacher's question, reflect about possible answers, select an appropriate answer, and then raise their hand to share. This processing time proves particularly crucial for students learning in a second language, students with processing differences, or students from cultures where reflection before speaking is valued.

Wait Time 2, the pause after a student response, proves equally important though often overlooked. This silence signals that you value thinking over quick closure, invites other students to build on the response, and models intellectual patience. During Wait Time 2, resist the urge to immediately evaluate, rephrase, or elaborate on student answers. Instead, maintain an expectant expression that communicates you are still processing their thinking. Other students will often jump in to add, challenge, or question their peer's ideas.

The bigger and better the question, the longer the wait time should be. Some educators use 'Think Time' rather than 'Wait Time' to emphasise what is really occurring. For truly complex questions, consider incorporating written reflection time before oral responses, giving students one to two minutes to jot initial thoughts. This scaffold supports all learners whilst maintaining high cognitive demand.

Cold calling (calling on students who have not raised their hands) increases participation equity, ensures all students remain cognitively engaged, and when implemented supportively, reduces rather than increases student anxiety. Research shows cold calling increases voluntary participation rates for both male and female students, with particularly strong effects for women.

Traditional 'hands-up' questioning creates inequitable participation patterns where the same confident, articulate, enthusiastic students answer questions every lesson whilst other students avoid engaging and rely on peers to answer on their behalf. Cold calling addresses this by distributing talk equitably across the room, signalling that every student's thinking matters. Research by Dallimore, Hertenstein, and Platt indicates that in high cold-calling classrooms, women answer the same number of volunteer questions as men, and cold calling increases voluntary participation rates over time.

Research indicates there is a right and wrong way to use cold calling. Teachers using a warmer approach quickly check for understanding whilst ameliorating students' fears and anxiety, resulting in richer, more productive discussions where students feel safe to take risks. Teachers who try to catch students off-guard, however, creates heightened anxiety. The difference lies in implementation approach rather than the technique itself.

Effective cold calling begins with building supportive classroom culture. Establish norms emphasising that mistakes are part of learning, that thinking aloud helps everyone learn, and that supporting each other is expected. Set these expectations explicitly before beginning cold calling: 'In this class, I'll call on people whose hands aren't raised. This isn't to catch you out; it's because everyone's thinking matters. If you're unsure, that's fine. We'll figure it out together.' This framing transforms cold calling from threatening to inclusive.

Build in adequate wait time after asking your question. Counting to five in your head establishes a solid baseline before calling on anyone. For complex questions, use 'turn-and-talk' first, allowing students to discuss with partners before you cold call. This provides rehearsal time and ensures students have at least one idea to share. Consider using participation cards or popsicle sticks with student names to randomise selection fairly, making the process feel systematic rather than arbitrary.

Support struggling students through 'phone a friend' protocols where stuck students can consult a classmate before responding. Alternatively, offer multiple-choice scaffolds: 'Jordan, which of these three interpretations seems strongest to you?' Track participation equitably through simple tallying systems, ensuring you do not inadvertently call on the same students repeatedly whilst skipping over shy students. Studies examining cold calling's impact found that significantly more students answer questions voluntarily in classes with high cold calling, and the number of students voluntarily answering increases over time, suggesting that cold calling ultimately builds rather than diminishes confidence.

Effective questioning follows intentional sequences that scaffold student thinking from accessible entry points to increasingly complex analysis. The funnel approach (broad to specific) and the reverse funnel (specific to broad) serve different pedagogical purposes, whilst follow-up questioning techniques deepen initial responses.

The funnel sequence begins with open, divergent questions that invite multiple perspectives: 'What do you notice about this diagram?', 'What questions does this raise for you?', 'What different interpretations are possible?'. As discussion progresses, questions become more focused, directing attention to specific elements or relationships. This sequence works well when introducing new topics, as it honours students' initial observations whilst gradually guiding them toward disciplinary ways of thinking.

The reverse funnel begins with focused, convergent questions establishing specific knowledge before opening to broader application: 'What is the definition of photosynthesis?', 'What are the inputs and outputs?', 'Now, how might climate change affect this process?'. This sequence proves effective when building systematically from foundational concepts toward complex applications, particularly in mathematics and sciences where precise understanding of terms and relationships matters.

Follow-up questioning deepens initial student responses. Probing questions ask for elaboration: 'Can you say more about that?', 'What makes you think that?', 'What evidence supports your claim?'. These invitations communicate genuine interest in student thinking. Redirecting questions invite other students to engage: 'Who can add to that?', 'Does anyone see it differently?', 'Can someone build on Alex's idea?'. This technique positions students as intellectual resources for each other rather than making the teacher the sole arbiter of correctness.

Uptake questions explicitly incorporate students' language into subsequent questions: 'Ahmed said it was chaotic. Let's explore that word. What makes this situation chaotic rather than simply disorganised?'. This validation demonstrates that you listened carefully and value their contributions. Challenging questions push students beyond initial thinking: 'What would someone who disagreed with you say?', 'What assumptions are we making?', 'What's the limitation of that approach?'. These moves develop meta-cognitive awareness and intellectual humility.

Resist the urge to answer your own questions when students struggle. Instead, rephrase, provide analogies, or break complex questions into smaller components. If a question falls completely flat, acknowledge it: 'That question didn't land well. Let me try a different angle.' This models intellectual flexibility and prevents wasted time on unproductive questioning paths.

Different instructional purposes require different types of questions. Diagnostic questions assess prior knowledge, convergent questions check understanding of taught content, divergent questions promote creative thinking, and evaluative questions develop judgment. Skilled teachers orchestrate these question types strategically throughout lessons.

Diagnostic questions, used at lesson beginnings, reveal what students already know, believe, or misunderstand about topics: 'What have you heard about..?', 'Where have you encountered this before?', 'What do you think you know about..?'. These questions guide instructional decisions, helping teachers identify necessary groundwork or areas where students already have strong foundations. Importantly, diagnostic questions should be low-stakes, with responses used to inform teaching rather than evaluate students.

Convergent questions guide students toward specific understandings or skills: 'What is the capital of..?', 'What happened after..?', 'How do you calculate..?'. These questions serve essential purposes in direct instruction, skills practice, and comprehension checking. Whilst convergent questions should not dominate classroom discourse, they play important roles in establishing shared knowledge foundations and monitoring whether students grasp key concepts before going forward.

Divergent questions invite multiple acceptable responses, promoting creative thinking and revealing diverse perspectives: 'What are all the possible ways to..?', 'How many solutions can you generate?', 'What would happen if..?'. These questions communicate that thinking matters more than single correct answers. In mathematics, divergent questions might ask students to generate different strategies for solving a problem; in history, to consider alternative outcomes if different decisions had been made; in art, to envision multiple design solutions.

Evaluative questions require students to make and defend judgments using criteria: 'Which approach is most effective and why?', 'What would be the best solution given these constraints?', 'How do these two arguments compare in strength?'. These questions develop students' capacity to move beyond personal preference toward reasoned judgment. Make criteria explicit or ask students to generate criteria themselves, making evaluation processes transparent rather than mysterious.

Process-focused questions develop meta-cognitive awareness by asking students to reflect on their thinking: 'How did you figure that out?', 'What made this difficult?', 'What strategy did you use?', 'If you were starting over, what would you do differently?'. These questions help students develop awareness of their own cognitive processes, enabling them to become more strategic, self-directed learners. Research consistently shows that meta-cognitive skills strongly predict academic success across domains.

Incorrect answers represent valuable learning opportunities rather than classroom obstacles. Research consistently shows that productive struggle through mistakes enhances long-term retention and understanding. UK teachers increasingly recognise that how they respond to incorrect answers determines whether students develop resilience or avoidance behaviours. The key lies in treating wrong answers as thinking made visible, providing insights into student reasoning processes that correct answers often conceal.

The "dignified correction" approach maintains student confidence whilst addressing misconceptions directly. Rather than immediately correcting or moving to another student, effective teachers probe the reasoning: "Talk me through your thinking process" or "What made you consider that approach?" This technique, particularly powerful in mathematics, reveals whether errors stem from conceptual misunderstanding, procedural mistakes, or simple calculation errors. A Year 10 student incorrectly solving quadratic equations might have sound algebraic reasoning but struggle with arithmetic, requiring different instructional responses.

Building on incorrect answers creates teachable moments that benefit entire classes. When a student suggests that plants breathe like humans during a KS3 biology lesson, skilled teachers might respond: "That's an interesting connection. How is plant respiration similar to human breathing, and where might that comparison break down?" This approach validates the student's thinking whilst guiding toward accurate understanding. The "partial credit" method acknowledges correct elements within incorrect responses: "You've identified the key historical period correctly. Now, what additional evidence would strengthen your interpretation?"

Systematic approaches to handling incorrect answers include the "error analysis" strategy popular in UK maths departments. Teachers explicitly examine common mistakes, asking students to identify errors in worked examples and explain correct approaches. This method, aligned with Assessment for Learning principles, helps students develop self-correction skills. For sensitive topics or vulnerable students, private correction through written feedback or quiet individual discussion maintains dignity whilst ensuring misconceptions don't persist. The goal remains creating classroom cultures where intellectual risk-taking is encouraged and mistakes become stepping stones to understanding.

Teachers in 2025 face a persistent challenge. They ask questions (AI-generated hinge questions) but rarely use them to stretch student thinking. Questions often fail to engage because they stay at surface level. The gap between checking facts and developing deep understanding remains wide.

Teacher questioning refers to the deliberate use of questions to assess understanding, promote thinking, and guide learning. Too many classroom questions focus on recall. They check if students remember information rather than whether they can apply, analyse, or evaluate it. This challenge is particularly evident in subjects like mathematics, where examination questioning in maths can transform procedural learning into conceptual understanding.

Build better questions with question stems, examples by subject, and the Question Upgrader tool.

From Structural Learning, structural-learning.com

Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive skills provides a useful framework. The revised taxonomy identifies si x levels of cognitive learning. Each level requires different thinking processes. Classification taxonomies have evolved to guide teacher questioning, from early work by Krathwohl (1964) and Wilen (1986) to Morgan and Saxton (1991). Hannel and Hannel (2005) demonstrated how teacher questions promote student engagement. Dekker-Groen (2015) examined how sequences of teacher and student questions influence classroom dialogue, emphasising the role of questioning to develop oracy.

These frameworks help, but they need careful application. Each classroom situation is unique. Not every student needs questions at multiple cognitive levels in every lesson.

Schons's (1983) model of reflection offers three critical questions for teachers:

Being able to categorise questions is a starting point for improving practice.

Questions are integral to classroom life. They form a core part of every teacher's pedagogical repertoire. Yet they often serve merely to check facts. Black et al. (2003) stated that higher-order probing questions enable teachers to be better informed about student progress. This knowledge leads to more individualized and differentiated support. Questions that probe for deeper meaning creates critical thinking skills. They encourage the flexible learners and problem-solvers needed in modern classrooms.

Questioning forces students to think critically about content. When teachers ask questions, students must process information and generate solutions. They cannot rely on memorized responses.

Teacher questions function as feedback mechanisms. Feedback allows teachers to determine whether their methods work. This matters particularly in subjects like mathematics, where problems can be solved through trial and error. Rather than simply providing correct answers, teachers should offer multiple choices and let students determine which solution works.

This approach is called open-ended questioning. It requires students to use critical thinking and problem-solving abilities. Open-ended questioning appears across science, social studies, and language arts lessons.

Choose questions based on your learning objective and students' current understanding level. Use recall questions to check foundational knowledge, then progress to application and analysis questions to deepen thinking. Match question complexity to student readiness while gradually increasing cognitive demand throughout the lesson.

Creating effective cognitive questions is simpler than it sounds. Some classrooms display question walls as reference points for quick thinking. A question matrix can help generate divergent questions both in the moment and during planning.

The Thinking Framework thinking skills cards provide a practical tool for generating questions on the spot. These 30 cards are organised into five colored categories: Green (Extract..), Blue (Categorise..), Yellow (Explain..), Orange (Target Vocabulary..), and Red (Combine..). Each card prompts a specific type of cognitive response. Teachers can select a card that matches their learning objective and use it to frame questions during a lesson. Students can also use these cards to generate questions for peers, turning questioning into a collaborative learning activity rather than a teacher-led exercise.

The key to eliciting comprehensive student responses is focusing on questions from the bottom right corner of a cognitive matrix. Questions beginning with "Why did..?" or "How might..?" produce answers requiring detailed explanation. Complex questions demand more student thinking than simple yes-no responses.

Tom Sherrington recently argued that depth of knowledge shows in the ability to explain something. This type of deep learning emerges through sophisticated student responses. These responses are nurtured and articulated through well-designed cognitive questions.

Within the Thinking Framework, Socratic questioning is categorised according to desired learning outcomes. Teachers think about the learning experience and consider how they want learners to think. The cognitive response you want to nurture determines the way you talk about content.

This dialogic approach describes learning through talk, not learning to talk. The Thinking Framework includes response structures that equip teachers with talk moves that shift from simple recall to evaluative judgement.

Effective questioning hinges on careful planning and execution. Consider these strategies to enhance your questioning techniques:

The goal is to ask questions and to creates a classroom environment where questioning is a tool for deep learning and critical thinking.

Consider using visual aids, such as diagrams or mind maps, to support questioning. These tools can help students organise their thoughts and provide more structured responses. Regularly assess your questioning strategies through reflection and feedback from colleagues or students. Continuously refine your approach to meet the evolving needs of your learners.

By adopting these strategies, teachers can transform their classrooms into vibrant hubs of inquiry, where students actively engage with content and develop the critical thinking skills needed for success in the 21st century.

Effective questioning is more than just asking questions; it's about creating a culture of inquiry that promotes deep learning. By shifting from surface-level recall to higher-order thinking, teachers can helps students to become critical thinkers and problem-solvers.

Embracing strategies such as the Question Matrix, thoughtful wait time, and the Pause, Pounce, Bounce technique, educators can transform their classrooms into environments where students actively engage with content and develop the skills necessary to thrive in an ever-changing world. The power of questioning lies in the answers it elicits and in the thinking it provokes.

Wait time represents one of the most powerful yet underutilised strategies in UK classrooms. Mary Budd Rowe's groundbreaking research revealed that teachers typically wait less than one second after asking a question before calling for an answer. This rushed approach prevents deeper thinking and excludes students who need processing time. Rowe identified two critical wait periods: Wait Time 1 (after asking the question) and Wait Time 2 (after a student responds). Extending both to 3-5 seconds transforms classroom dynamics dramatically.

The benefits of proper wait time extend beyond individual thinking. Research shows that when teachers implement adequate wait time, student responses become longer and more thoughtful, participation increases across all ability levels, and the quality of discourse improves significantly. In a Year 8 science lesson exploring photosynthesis, rather than accepting the first hand raised after asking "Why do plants need different types of light?", effective teachers pause, scan the room, and allow thinking time before selecting respondents strategically.

Implementing wait time requires deliberate practice and systems. Many teachers find success using silent counting techniques or physical cues like placing a hand on their desk during wait periods. The "no hands up" approach works particularly well with extended wait time, as it removes the pressure for immediate responses. For younger pupils in KS1 and KS2, visual countdown timers or "thinking pose" instructions help establish wait time routines. Secondary teachers often combine wait time with think-pair-share structures, allowing students to process individually before discussing with partners.

Different question types require adjusted wait times. Factual recall questions may need only 1-2 seconds, whilst analytical or evaluative questions about GCSE texts or A-Level concepts benefit from 5-7 seconds minimum. Teachers working with EAL students or those with processing difficulties should extend wait times further, recognising that language translation and cognitive processing occur simultaneously. The key lies in communicating expectations clearly whilst maintaining the productive tension that encourages deep thinking.

Mathematics questioning in UK classrooms requires a fundamental shift from procedural verification to conceptual exploration. Instead of asking "What is 15% of 80?", effective maths teachers pose questions like "How many different ways can you calculate 15% of 80, and which method reveals the most about percentage relationships?" This approach aligns with the mastery curriculum emphasis on depth over breadth. Key Stage 3 algebra lessons benefit from questions such as "What would happen if we changed this coefficient?" rather than simply "Solve for x". A-Level mathematics teachers use questioning to expose mathematical reasoning: "Explain why integration and differentiation are inverse processes using this specific example."

English literature questioning moves beyond comprehension checks toward analytical thinking. Rather than "What happens in Act 2?", GCSE English teachers ask "How does Shakespeare use Lady Macbeth's language in Act 2 to reveal her changing psychological state?" Effective literature questioning often employs the AP3 framework (Author's Purpose, Perspective, and Presentation) familiar to many UK English departments. For younger readers in KS2, questions like "What do you notice about how the author describes the setting when the character feels afraid?" develop critical reading skills progressively.

Science questioning emphasises investigative thinking and hypothesis formation. Primary science benefits from "What if?" and "How could we test?" questions that encourage scientific method thinking. "What would happen if we changed the angle of this ramp?" transforms a simple forces demonstration into inquiry-based learning. Secondary science teachers use questioning to develop practical investigation skills required for GCSE practicals: "Based on your observations, what relationship do you predict between temperature and reaction rate?" Chemistry teachers particularly benefit from questions that link molecular behaviour to observable phenomena.

History questioning develops source evaluation and contextual thinking skills essential for GCSE and A-Level success. Instead of "When did World War I begin?", effective history teachers ask "What can this propaganda poster tell us about civilian attitudes in 1916, and what might it not reveal?" Geography teachers combine factual knowledge with analytical skills through questions like "How might climate change affect this coastal management strategy differently in 20 years?" These subject-specific approaches ensure questioning serves both knowledge building and skill development simultaneously.

Bloom's Taxonomy provides a structured framework for questioning that moves students from basic know ledge recall to higher-order thinking skills. The six progressive levels (Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analysing, Evaluating, and Creating) help teachers design questions that develop increasingly complex cognitive skills.

Approximately 80 per cent of all questions teachers ask are factual, literal, or knowledge-based, resulting in classrooms where little creative thinking takes place. Bloom's Taxonomy addresses this problem by providing explicit question stems for each cognitive level. Rather than focusing on rote memorisation, the taxonomy encourages students to analyse, evaluate, and create, developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills that extend far beyond simple recall.

At the Remembering level, questions prompt retrieval of basic facts: 'What is..?', 'When did..?', 'Who were..?'. Understanding questions require explanation: 'How would you summarise..?', 'What is the main idea of..?', 'Can you explain this in your own words?'. These foundational levels establish baseline knowledge necessary for more complex thinking.

Applying questions bridge theory and practice: 'How would you use..?', 'What examples can you find to..?', 'How would you solve..?'. Analysing questions require breaking concepts into component parts: 'What evidence can you identify..?', 'How do these ideas compare?', 'What is the relationship between..?'. These mid-level questions develop students' capacity to work with information rather than simply receive it.

Evaluating questions demand judgment based on criteria: 'What is your opinion of..?', 'How would you prioritise..?', 'What choice would you have made..?'. Creating questions, at the highest level, require synthesis of knowledge to produce something new: 'What would happen if..?', 'Can you design a..?', 'How could you improve..?'. According to García, Pacheco, and Aguilar (2018), incorporating Bloom's Taxonomy into lesson planning led to a 19.6 per cent improvement in students' academic performance.

Teachers can support their own development by colour-coding question stems on index cards for each level, keeping these cards on a key ring in different learning centres or in pockets for quick reference. Many educators assume primary-level students cannot handle higher-level questions, but challenging all students through higher-order questioning represents one of the best ways to stimulate learning and enhance brain development, regardless of age. The goal is to build students' thinking muscles gradually, creating classroom environments where students feel comfortable making mistakes as they grapple with increasingly complex questions.

Wait time (the pause between asking a question and soliciting an answer) typically averages 0.7 to 1.5 seconds in classrooms, but extending this pause to 3-5 seconds produces remarkable improvements in student engagement, response quality, and critical thinking. Two distinct types exist: Wait Time 1 (after the question) and Wait Time 2 (after a student response).

In 1972, Mary Budd Rowe coined the phrase 'wait time' after discovering that teachers typically waited less than two seconds before speaking after asking a question. This rushed pace prevents students from formulating thoughtful responses. Robert Stahl later expanded this concept by coining 'think time', emphasising that these pauses provide uninterrupted silence for both teachers and students to reflect on and process their thoughts, feelings, and reactions.

When teachers extend wait time beyond three seconds, significant positive changes occur in both student and teacher discourse. Students engage more actively in class through increased student talk and questions, longer responses, and more idea exchange between peers. They also exhibit enhanced critical thinking, offering higher-quality utterances. Specifically, the number of unsolicited responses increases (even from students reluctant to speak), the number of appropriate answers increases, student responses become lengthier and delivered in full correct sentences, and student confidence rises.

Wait time provides necessary opportunity for student brains to organise the complex tasks involved in thinking and reflecting after a question is asked. Even the fastest student brain needs time to hear the teacher's question, reflect about possible answers, select an appropriate answer, and then raise their hand to share. This processing time proves particularly crucial for students learning in a second language, students with processing differences, or students from cultures where reflection before speaking is valued.

Wait Time 2, the pause after a student response, proves equally important though often overlooked. This silence signals that you value thinking over quick closure, invites other students to build on the response, and models intellectual patience. During Wait Time 2, resist the urge to immediately evaluate, rephrase, or elaborate on student answers. Instead, maintain an expectant expression that communicates you are still processing their thinking. Other students will often jump in to add, challenge, or question their peer's ideas.

The bigger and better the question, the longer the wait time should be. Some educators use 'Think Time' rather than 'Wait Time' to emphasise what is really occurring. For truly complex questions, consider incorporating written reflection time before oral responses, giving students one to two minutes to jot initial thoughts. This scaffold supports all learners whilst maintaining high cognitive demand.

Cold calling (calling on students who have not raised their hands) increases participation equity, ensures all students remain cognitively engaged, and when implemented supportively, reduces rather than increases student anxiety. Research shows cold calling increases voluntary participation rates for both male and female students, with particularly strong effects for women.

Traditional 'hands-up' questioning creates inequitable participation patterns where the same confident, articulate, enthusiastic students answer questions every lesson whilst other students avoid engaging and rely on peers to answer on their behalf. Cold calling addresses this by distributing talk equitably across the room, signalling that every student's thinking matters. Research by Dallimore, Hertenstein, and Platt indicates that in high cold-calling classrooms, women answer the same number of volunteer questions as men, and cold calling increases voluntary participation rates over time.

Research indicates there is a right and wrong way to use cold calling. Teachers using a warmer approach quickly check for understanding whilst ameliorating students' fears and anxiety, resulting in richer, more productive discussions where students feel safe to take risks. Teachers who try to catch students off-guard, however, creates heightened anxiety. The difference lies in implementation approach rather than the technique itself.

Effective cold calling begins with building supportive classroom culture. Establish norms emphasising that mistakes are part of learning, that thinking aloud helps everyone learn, and that supporting each other is expected. Set these expectations explicitly before beginning cold calling: 'In this class, I'll call on people whose hands aren't raised. This isn't to catch you out; it's because everyone's thinking matters. If you're unsure, that's fine. We'll figure it out together.' This framing transforms cold calling from threatening to inclusive.

Build in adequate wait time after asking your question. Counting to five in your head establishes a solid baseline before calling on anyone. For complex questions, use 'turn-and-talk' first, allowing students to discuss with partners before you cold call. This provides rehearsal time and ensures students have at least one idea to share. Consider using participation cards or popsicle sticks with student names to randomise selection fairly, making the process feel systematic rather than arbitrary.

Support struggling students through 'phone a friend' protocols where stuck students can consult a classmate before responding. Alternatively, offer multiple-choice scaffolds: 'Jordan, which of these three interpretations seems strongest to you?' Track participation equitably through simple tallying systems, ensuring you do not inadvertently call on the same students repeatedly whilst skipping over shy students. Studies examining cold calling's impact found that significantly more students answer questions voluntarily in classes with high cold calling, and the number of students voluntarily answering increases over time, suggesting that cold calling ultimately builds rather than diminishes confidence.

Effective questioning follows intentional sequences that scaffold student thinking from accessible entry points to increasingly complex analysis. The funnel approach (broad to specific) and the reverse funnel (specific to broad) serve different pedagogical purposes, whilst follow-up questioning techniques deepen initial responses.

The funnel sequence begins with open, divergent questions that invite multiple perspectives: 'What do you notice about this diagram?', 'What questions does this raise for you?', 'What different interpretations are possible?'. As discussion progresses, questions become more focused, directing attention to specific elements or relationships. This sequence works well when introducing new topics, as it honours students' initial observations whilst gradually guiding them toward disciplinary ways of thinking.

The reverse funnel begins with focused, convergent questions establishing specific knowledge before opening to broader application: 'What is the definition of photosynthesis?', 'What are the inputs and outputs?', 'Now, how might climate change affect this process?'. This sequence proves effective when building systematically from foundational concepts toward complex applications, particularly in mathematics and sciences where precise understanding of terms and relationships matters.

Follow-up questioning deepens initial student responses. Probing questions ask for elaboration: 'Can you say more about that?', 'What makes you think that?', 'What evidence supports your claim?'. These invitations communicate genuine interest in student thinking. Redirecting questions invite other students to engage: 'Who can add to that?', 'Does anyone see it differently?', 'Can someone build on Alex's idea?'. This technique positions students as intellectual resources for each other rather than making the teacher the sole arbiter of correctness.

Uptake questions explicitly incorporate students' language into subsequent questions: 'Ahmed said it was chaotic. Let's explore that word. What makes this situation chaotic rather than simply disorganised?'. This validation demonstrates that you listened carefully and value their contributions. Challenging questions push students beyond initial thinking: 'What would someone who disagreed with you say?', 'What assumptions are we making?', 'What's the limitation of that approach?'. These moves develop meta-cognitive awareness and intellectual humility.

Resist the urge to answer your own questions when students struggle. Instead, rephrase, provide analogies, or break complex questions into smaller components. If a question falls completely flat, acknowledge it: 'That question didn't land well. Let me try a different angle.' This models intellectual flexibility and prevents wasted time on unproductive questioning paths.

Different instructional purposes require different types of questions. Diagnostic questions assess prior knowledge, convergent questions check understanding of taught content, divergent questions promote creative thinking, and evaluative questions develop judgment. Skilled teachers orchestrate these question types strategically throughout lessons.

Diagnostic questions, used at lesson beginnings, reveal what students already know, believe, or misunderstand about topics: 'What have you heard about..?', 'Where have you encountered this before?', 'What do you think you know about..?'. These questions guide instructional decisions, helping teachers identify necessary groundwork or areas where students already have strong foundations. Importantly, diagnostic questions should be low-stakes, with responses used to inform teaching rather than evaluate students.

Convergent questions guide students toward specific understandings or skills: 'What is the capital of..?', 'What happened after..?', 'How do you calculate..?'. These questions serve essential purposes in direct instruction, skills practice, and comprehension checking. Whilst convergent questions should not dominate classroom discourse, they play important roles in establishing shared knowledge foundations and monitoring whether students grasp key concepts before going forward.

Divergent questions invite multiple acceptable responses, promoting creative thinking and revealing diverse perspectives: 'What are all the possible ways to..?', 'How many solutions can you generate?', 'What would happen if..?'. These questions communicate that thinking matters more than single correct answers. In mathematics, divergent questions might ask students to generate different strategies for solving a problem; in history, to consider alternative outcomes if different decisions had been made; in art, to envision multiple design solutions.

Evaluative questions require students to make and defend judgments using criteria: 'Which approach is most effective and why?', 'What would be the best solution given these constraints?', 'How do these two arguments compare in strength?'. These questions develop students' capacity to move beyond personal preference toward reasoned judgment. Make criteria explicit or ask students to generate criteria themselves, making evaluation processes transparent rather than mysterious.

Process-focused questions develop meta-cognitive awareness by asking students to reflect on their thinking: 'How did you figure that out?', 'What made this difficult?', 'What strategy did you use?', 'If you were starting over, what would you do differently?'. These questions help students develop awareness of their own cognitive processes, enabling them to become more strategic, self-directed learners. Research consistently shows that meta-cognitive skills strongly predict academic success across domains.

Incorrect answers represent valuable learning opportunities rather than classroom obstacles. Research consistently shows that productive struggle through mistakes enhances long-term retention and understanding. UK teachers increasingly recognise that how they respond to incorrect answers determines whether students develop resilience or avoidance behaviours. The key lies in treating wrong answers as thinking made visible, providing insights into student reasoning processes that correct answers often conceal.

The "dignified correction" approach maintains student confidence whilst addressing misconceptions directly. Rather than immediately correcting or moving to another student, effective teachers probe the reasoning: "Talk me through your thinking process" or "What made you consider that approach?" This technique, particularly powerful in mathematics, reveals whether errors stem from conceptual misunderstanding, procedural mistakes, or simple calculation errors. A Year 10 student incorrectly solving quadratic equations might have sound algebraic reasoning but struggle with arithmetic, requiring different instructional responses.

Building on incorrect answers creates teachable moments that benefit entire classes. When a student suggests that plants breathe like humans during a KS3 biology lesson, skilled teachers might respond: "That's an interesting connection. How is plant respiration similar to human breathing, and where might that comparison break down?" This approach validates the student's thinking whilst guiding toward accurate understanding. The "partial credit" method acknowledges correct elements within incorrect responses: "You've identified the key historical period correctly. Now, what additional evidence would strengthen your interpretation?"

Systematic approaches to handling incorrect answers include the "error analysis" strategy popular in UK maths departments. Teachers explicitly examine common mistakes, asking students to identify errors in worked examples and explain correct approaches. This method, aligned with Assessment for Learning principles, helps students develop self-correction skills. For sensitive topics or vulnerable students, private correction through written feedback or quiet individual discussion maintains dignity whilst ensuring misconceptions don't persist. The goal remains creating classroom cultures where intellectual risk-taking is encouraged and mistakes become stepping stones to understanding.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/questioning-in-teaching#article","headline":"Effective questioning in teaching","description":"Master effective classroom questioning techniques with our guide, designed to engage students and stimulate critical thinking.","datePublished":"2022-07-26T14:09:37.867Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/questioning-in-teaching"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a4528161b5c32bcfb2af2_696a45220c544e34c56dd580_questioning-in-teaching-illustration.webp","wordCount":3475},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/questioning-in-teaching#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Effective questioning in teaching","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/questioning-in-teaching"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is Teacher Questioning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teacher questioning refers to the deliberate use of questions to assess understanding, promote thinking, and guide learning. Too many classroom questions focus on recall. They check if students remember information rather than whether they can apply, analyse, or evaluate it. This challenge is particularly evident in subjects like mathematics, where examination questioning in maths can transform procedural learning into conceptual understanding."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Does Teacher Questioning Promote Student Learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Questioning forces students to think critically about content. When teachers ask questions, students must process information and generate solutions. They cannot rely on memorized responses ."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Do You Choose the Right Type of Question for Students?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Choose questions based on your learning objective and students' current understanding level. Use recall questions to check foundational knowledge, then progress to application and analysis questions to deepen thinking. Match question complexity to student readiness while gradually increasing cognitive demand throughout the lesson."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Practical Strategies for Effective Questioning Effective questioning hinges on careful planning and execution. Consider these strategies to enhance your questioning techniques: Plan Questions in Advance : Integrate targeted questions into your lesson plans. Align these questions with learning objectives and desired cognitive outcomes. Use Wait Time : Provide students with sufficient time to formulate their responses. Increase wait time to at least five seconds after asking a question. This allows more students to participate. Vary Question Types : Move beyond simple recall questions. Incorporate open-ended, analytical, and evaluative questions to promote deeper thinking. Encourage Student Questions : Create a classroom culture where students feel comfortable asking questions. Model effective questioning techniques. Active Listening : Pay close attention to student responses. Provide constructive feedback and encourage further exploration of ideas. The Pause, Pounce, Bounce Technique : Ask a question (pause), nominate a student to answer (pounce), and then ask other students to comment on the initial answer (bounce). This gets everyone involved. The goal is to ask questions and to creates a classroom environment where questioning is a tool for deep learning and critical thinking. Consider using visual aids, such as diagrams or mind maps, to support questioning. These tools can help students organise their thoughts and provide more structured responses. Regularly assess your questioning strategies through reflection and feedback from colleagues or students. Continuously refine your approach to meet the evolving needs of your learners. By adopting these strategies, teachers can transform their classrooms into vibrant hubs of inquiry, where students actively engage with content and develop the critical thinking skills needed for success in the 21st century. Conclusion Effective questioning is more than just asking questions; it's about creating a culture of inquiry that promotes deep learning. By shifting from surface-level recall to higher-order thinking, teachers can helps students to become critical thinkers and problem-solvers. Embracing strategies such as the Question Matrix, thoughtful wait time, and the Pause, Pounce, Bounce technique, educators can transform their classrooms into environments where students actively engage with content and develop the skills necessary to thrive in an ever-changing world. The power of questioning lies in the answers it elicits and in the thinking it provokes. How Do You Create Effective Wait Time in Questioning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Wait time represents one of the most powerful yet underutilised strategies in UK classrooms. Mary Budd Rowe's groundbreaking research revealed that teachers typically wait less than one second after asking a question before calling for an answer. This rushed approach prevents deeper thinking and excludes students who need processing time. Rowe identified two critical wait periods: Wait Time 1 (after asking the question) and Wait Time 2 (after a student responds). Extending both to 3-5 seconds tr"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Are Subject-Specific Questioning Strategies for UK Classrooms?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Mathematics questioning in UK classrooms requires a fundamental shift from procedural verification to conceptual exploration. Instead of asking \"What is 15% of 80?\", effective maths teachers pose questions like \"How many different ways can you calculate 15% of 80, and which method reveals the most about percentage relationships?\" This approach aligns with the mastery curriculum emphasis on depth over breadth. Key Stage 3 algebra lessons benefit from questions such as \"What would happen if we cha"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Should Teachers Handle Incorrect Answers?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Incorrect answers represent valuable learning opportunities rather than classroom obstacles. Research consistently shows that productive struggle through mistakes enhances long-term retention and understanding. UK teachers increasingly recognise that how they respond to incorrect answers determines whether students develop resilience or avoidance behaviours. The key lies in treating wrong answers as thinking made visible, providing insights into student reasoning processes that correct answers o"}}]}]}