The Extended Mind Theory: How Our Environment Shapes Thinking

Explore how the extended mind thesis reveals that tools, environments, and other people extend our cognitive capacities beyond the brain for better learning.

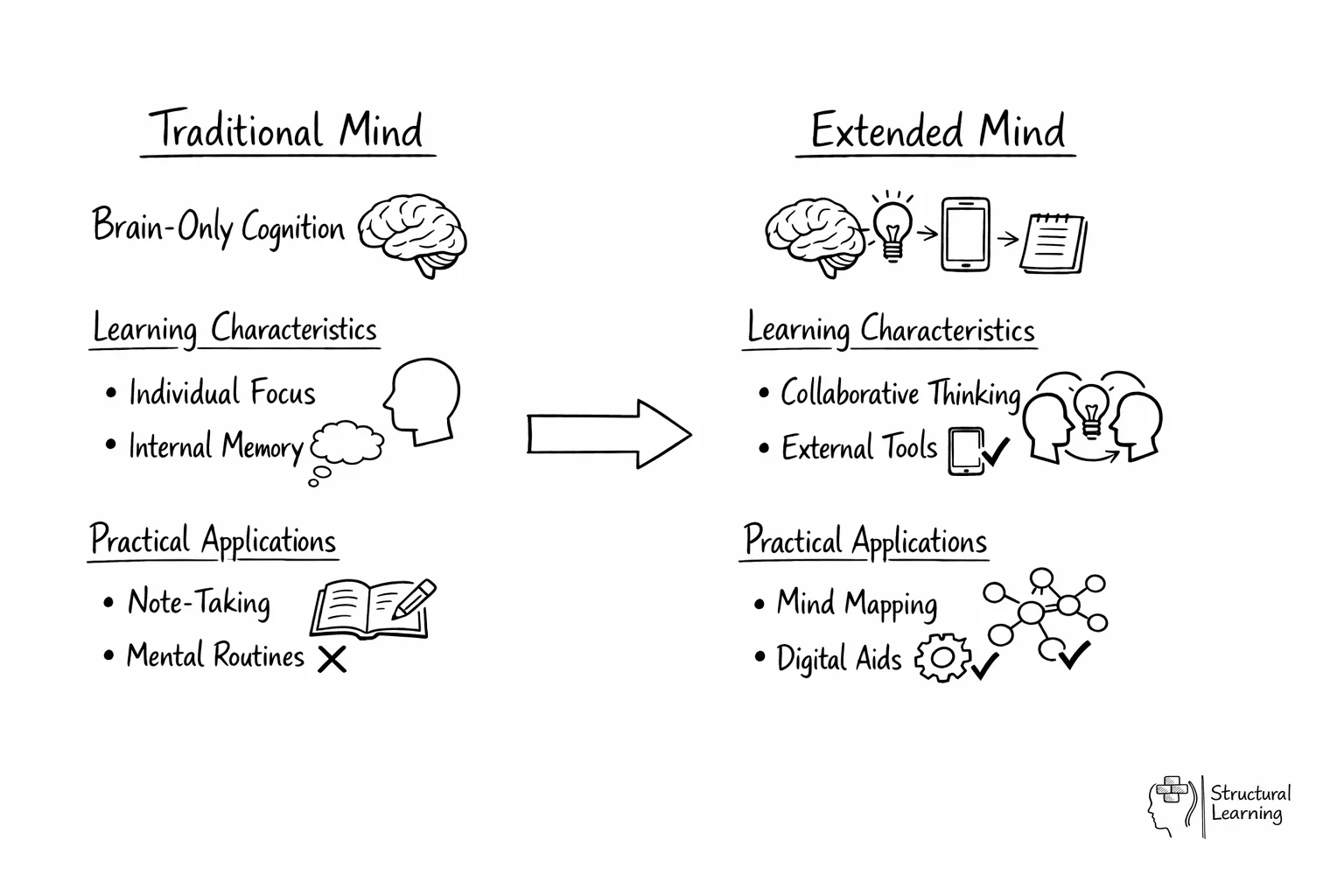

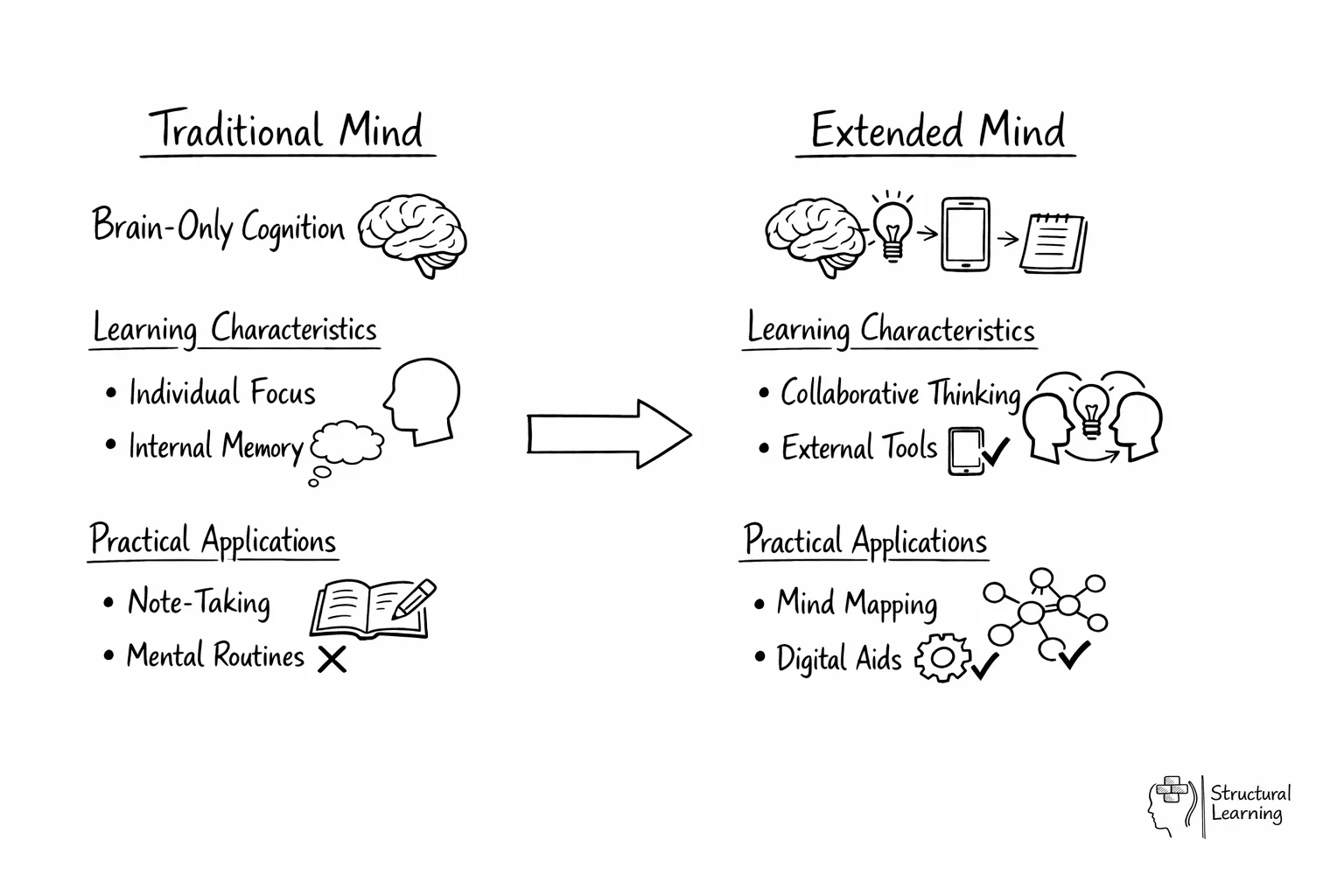

The extended mind thesis, proposed by philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers in 1998, challenges the assumption that cognition happens only inside the brain. They argued that tools, technologies, and environments can become genuine parts of our cognitive systems. A notebook that reliably stores information functions as part of memory; a calculator extends mathematical reasoning. For educators, this theory has profound implications: the classroom environment, available tools, and collaborative relationships do not merely support thinking but can constitute part of the thinking process itself.

The extended cognition theory (Clark and Chalmers) states that we think not only with our brains, but with our bodies, the tools and technologies we use and the spaces in which we learn and work. Cognition is essentially shaped by action and experience. Our brain-centric culture, where intelligence is believed to be innate, individual, and internal, makes this theory particularly relevant for children. Children don't always conjure up new thoughts, action plays a central role in developing our cognitive processes.

Extended cognition is something we all embrace. Whether it be using our fingers to count with or writing down our ideas onto paper, we are extending the bounds of cognition by using an external resource. Cognitive processes are complicated and human intelligence has become increasingly entangled in technology. This cognitive integration is at the very centre of the extended mind hypothesis. Where exactly does the mind finish?

We cannot command the brain at will to learn, to pay attention, or to remember. It is instead a very specific and limited organ, one that evolved to perform tasks very distinct from those we ask of it today. It is not a matter of individual differences in intelligence, but of the limits of everyone's brain.

The biological brain excels at a number of things: sensing and moving the body, manipulating material objects, navigating through space, and interacting with others. By using these natural strengths we will be able to facilitate and improve learning.

The brain isn't naturally adept at grasping abstract or counterintuitive ideas, ignoring distracting stimuli, or remembering information accurately and without error for a long period of time. As part of these functions, the brain needs "outside the brain" help, like the body, physical space, and tools, like social interactions.

When you're learning or studying, you don't want to sit in one spot, not moving, not talking, just pushing your brain to work harder. Distress and disappointment result from such an approach.

Gesturing is an integral part of a cognitive loop in which our hand motions influence our thoughts, and vice versa. The more gestures we make, the more fluent our thinking and speaking will be; the greater nuance and sophistication of our understanding. Have you ever watched someone give directions (without being able to hear them)? It's an impossible task to do without pointing or tracing your fingers. Here are some ways you can encourage the making of gestures:

In school, we do way too much “in our heads”; we would all be thinking more efficiently and effectively if we offloaded our cognitive processes more often. A quick look at the cognitive load theorywould suggest that 'freeing up' our cognitive resources plays an active role in enabling us to learn more effectively. This is a skill that can be cultivated, here are some ways I try to do so:

Experts who have difficulty teaching novices have "the curse of knowledge," which is when knowledge has become so automatic in their minds that they cannot explain it clearly to others. I am trying to keep in mind, as a teacher, that the curse of expertise applies to me. Chip and Dan Heathwrite about this topic in detail, once you are aware of the phenomenon, you'll immediately change your classroom practice.

1. What is the Extended Mind Theory?

The Extended Mind Theory, proposed by David Chalmers, suggests that human minds and mental processes are not confined within our brains but can extend into the environment. This cognitive extension implies that tools, objects, and even other people can become part of our minds. Research has explored this fascinating concept in depth.

2. How does the Extended Mind Hypothesis relate to social cognition?

The Extended Mind Hypothesis has significant implications for social cognition. It suggests that our understanding of others' minds can be influenced by our continuous interaction with them and our shared environment. This perspective can offer novel explanations of cognition in social contexts.

3. What does mental extension mean in the context of the Extended Mind Thesis?

Mental extension refers to the idea that our mental processes can extend beyond our brains into the external world. This could include using a notebook as an extension of our memory or a computer as an extension of our problem-solving abilities.

4. How does the Extended Mind Theory impact teaching and learning?

The Extended Mind Theory can transform our understanding of teaching and learning. It suggests that learning is not just an internal process but involves continuous interaction with others and the environment. This perspective can inform the development of teaching strategies that use these external resources.

5. What are the criticisms of the Extended Mind Theory?

While the Extended Mind Theory offers a unique perspective on cognition, it's not without criticism. Some argue that it overstates the role of external factors in cognition. Others question whether tools and objects can truly become part of our minds. Despite these debates, the Extended Mind Theory continues to stimulate thought-provoking discussions in cognitive science.

For a deeper dive into the Extended Mind Theory, you may refer to these research articles: Pressing the Flesh: A Tension in the Study of the Embodied, Embedded Mind?*, Extended emotion, From Wide Cognition to Mechanisms: A Silent Revolution, and The extended cognition thesis: Its significance for the philosophy of (cognitive) science.

scaffolding cognitive processes">

scaffolding cognitive processes">

The extended mind hypothesis, as proposed by Andy Clark and David Chalmers, has significant implications for understanding cognition. Key studies defend the hypothesis against criticisms, explore the nature of cognitive coupling with the environment, and discuss the broader implications for cognitive science. These studies highlight the importance of considering external objects and environments as integral parts of cognitive processes.

1. Extended Mind as a Different Way to realise Cognition

This paper responds to criticisms of the extended mind hypothesisby addressing the objections related to the distinctiveness of external cognitive states and the claim that the extended mind is not as groundbreaking as initially thought. It argues that the significance of the extended mind hypothesis lies in its rethinking of cognition and its relationship to the external environment (Meriç, 2022).

2. The Mark of the Cognitive and the Coupling-Constitution Fallacy: A defence of the Extended Mind Hypothesis

This study defends the extended mind hypothesis against criticisms that it conflates coupling with constitution and lacks a clear mark of the cognitive. It argues that coupling relations between agents and environmental resources are central to understanding cognitive systems and that the criticisms fail to undermine the extended cognition thesis (Piredda, 2017).

3. What is the Extension of the Extended Mind?

This paper explores the details of functional coupling between organisms and external entities in the environment, drawing parallels with theories in biology such as environmental constructivism and niche construction. It argues that instances of environmental coupling are constitutive of cognitive functions and that natural environmental features play a crucial role in extended cognition (Greif, 2015).

4. Intrinsic Content, Active Memory and the Extended Mind

This work addresses the criticism that external structures cannot support intrinsic content, a key mark of cognitive processes. It argues that concerns about intrinsic content are unfounded and do not compromise the extended mind hypothesis. The paper also discusses the broader implications of extended mind theory for understanding cognition (Clark, 2005).

5. Extended Cognition and the Extended Mind: Introduction

This introduction to a special issue on extended cognition and the extended mind provides an overview of the extended mind thesis by Andy Clark and David Chalmers. It discusses various aspects of the extended mind hypothesis and its implications, arguing for a broader understanding of cognitive processes that includes external structures and environments (Bartlett, 2016).

These studies provide the philosophical and cognitive science foundation for the extended mind thesis and its educational implications.

The Extended Mind 8,500+ citations

Clark, A. and Chalmers, D. J. (1998)

This seminal paper introduces the extended mind hypothesis, arguing that cognitive processes can extend beyond the brain into the external environment. Using the famous Otto and Inga thought experiment, Clark and Chalmers demonstrate that notebooks, tools, and technologies can function as genuine components of the mind. For educators, this challenges the assumption that learning must happen entirely "in the head."

Supersizing the Mind: Embodiment, Action, and Cognitive Extension 2,200+ citations

Clark, A. (2008)

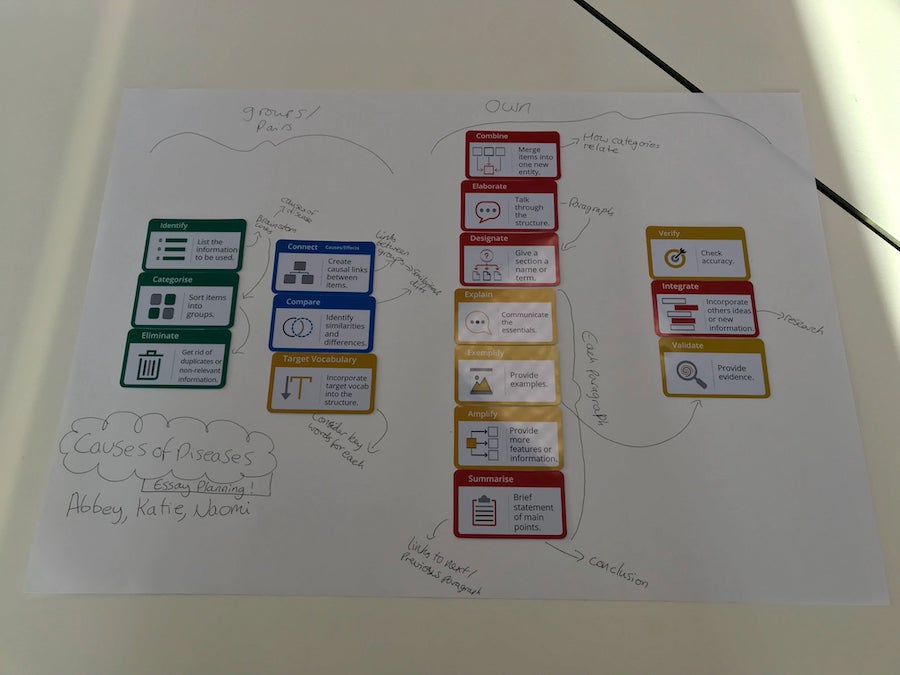

Clark expands the extended mind thesis, providing extensive evidence from cognitive science, robotics, and neuroscience. The book argues that human cognition is fundamentally designed to integrate with tools and environments. Teachers can apply this insight by recognising that graphic organisers, manipulatives, and collaborative discussions are cognitive tools that genuinely extend student thinking rather than mere aids.

The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain 350 citations

Paul, A. M. (2021)

Annie Murphy Paul translates the extended mind research into practical applications, demonstrating how thinking with the body, physical spaces, and other people produces better outcomes than thinking in isolation. The book draws on classroom research showing that movement, gesture, and environmental design directly affect learning quality. Teachers will find the chapters on collaborative cognition particularly relevant.

Embodied Cognition and Education: Possibilities and Limitations 1,400+ citations

Wilson, M. (2002)

Wilson's review examines six claims about embodied cognition, evaluating the evidence for each. The paper demonstrates that cognition is situated, time-pressured, and offloaded onto the environment. For classroom practice, this supports the use of physical manipulatives, collaborative problem-solving, and learning environments designed to support rather than hinder cognitive processes.

Distributed Cognition as a Framework for Understanding Learning 1,800+ citations

Hutchins, E. (1995)

Hutchins' landmark work shows that cognitive processes are distributed across individuals, tools, and social structures. His research on ship navigation demonstrates that group cognition can accomplish what no individual mind could manage alone. Teachers can apply this by designing collaborative tasks where the thinking is genuinely distributed across the group rather than replicated by each member individually.

The Extended Mind Theory, proposed by philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers in 1998, argues that cognition doesn't only happen inside the brain but can extend into our tools, technologies, and environments. For educators, this means that classroom environments, available tools, and collaborative relationships don't merely support thinking but can actually become part of the thinking process itself. Understanding this theory helps teachers recognise that a calculator or notebook isn't 'cheating' but rather a genuine extension of a child's cognitive abilities.

Research shows that gesturing creates a cognitive loop where hand motions influence thoughts and vice versa, making thinking more fluent and sophisticated. Teachers can model this by using their hands to explain their thinking and encouraging students to 'add shape to their thoughts' or 'use your hands to explain your thinking.' Having relevant artefacts nearby naturally encourages more gesturing, so tools like visual scaffolds can help students explain their cognitive processes whilst reducing mental burden.

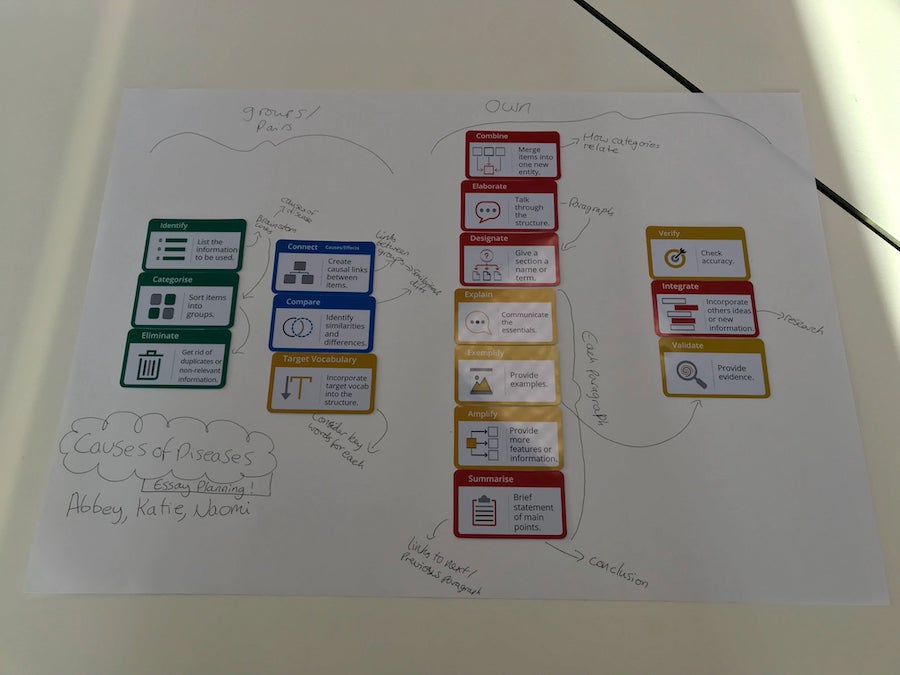

Cognitive offloading involves moving mental processes outside our heads to free up brain capacity for higher-level thinking like analysis and reflection. Teachers can implement this by explicitly teaching about cognitive load theory and using graphic organisers and diagrams to help students externalise their thoughts into shared spaces. This approach recognises that the brain evolved for specific tasks and needs external support for abstract thinking and long-term memory retention.

The curse of expertise occurs when teachers' knowledge has become so automatic that they struggle to explain it clearly to novices, as described by Chip and Dan Heath. Teachers can overcome this by making their thinking processes visible through cognitive apprenticeship, explicitly explaining their thought processes when modelling tasks like editing work. Breaking learning into small, manageable steps and naming internal learning processes helps students understand what to do and how to think about it.

The theory challenges the brain-centric culture that views intelligence as innate, individual, and internal by showing that cognition is shaped by action, experience, and external tools. This perspective recognises that apparent differences in ability often reflect the limits of everyone's brain rather than individual intelligence differences. For educators, this means focusing on using the brain's natural strengths in sensing, moving, and social interaction rather than forcing it to work harder in isolation.

Simple examples include using fingers to count, writing ideas on paper, or using calculators for mathematical reasoning, all of which extend cognitive boundaries through external resources. Teachers can encourage the use of Writer's Block scaffolding tools to help students explain their thinking processes and provide opportunities for improvisation, which naturally increases gesturing and cognitive offloading. The key is recognising these tools as genuine parts of the thinking process rather than mere aids or shortcuts.

Classroom environments should provide relevant artefacts and tools that naturally encourage gesturing and externalising thoughts, such as visual organisers and collaborative spaces. The physical space should support movement and social interaction, using the brain's natural strengths rather than forcing students to sit still and work in isolation. Creating shared spaces where students can work with their externalised thoughts more effectively transforms the environment into an active part of the cognitive process.

The extended mind thesis, proposed by philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers in 1998, challenges the assumption that cognition happens only inside the brain. They argued that tools, technologies, and environments can become genuine parts of our cognitive systems. A notebook that reliably stores information functions as part of memory; a calculator extends mathematical reasoning. For educators, this theory has profound implications: the classroom environment, available tools, and collaborative relationships do not merely support thinking but can constitute part of the thinking process itself.

The extended cognition theory (Clark and Chalmers) states that we think not only with our brains, but with our bodies, the tools and technologies we use and the spaces in which we learn and work. Cognition is essentially shaped by action and experience. Our brain-centric culture, where intelligence is believed to be innate, individual, and internal, makes this theory particularly relevant for children. Children don't always conjure up new thoughts, action plays a central role in developing our cognitive processes.

Extended cognition is something we all embrace. Whether it be using our fingers to count with or writing down our ideas onto paper, we are extending the bounds of cognition by using an external resource. Cognitive processes are complicated and human intelligence has become increasingly entangled in technology. This cognitive integration is at the very centre of the extended mind hypothesis. Where exactly does the mind finish?

We cannot command the brain at will to learn, to pay attention, or to remember. It is instead a very specific and limited organ, one that evolved to perform tasks very distinct from those we ask of it today. It is not a matter of individual differences in intelligence, but of the limits of everyone's brain.

The biological brain excels at a number of things: sensing and moving the body, manipulating material objects, navigating through space, and interacting with others. By using these natural strengths we will be able to facilitate and improve learning.

The brain isn't naturally adept at grasping abstract or counterintuitive ideas, ignoring distracting stimuli, or remembering information accurately and without error for a long period of time. As part of these functions, the brain needs "outside the brain" help, like the body, physical space, and tools, like social interactions.

When you're learning or studying, you don't want to sit in one spot, not moving, not talking, just pushing your brain to work harder. Distress and disappointment result from such an approach.

Gesturing is an integral part of a cognitive loop in which our hand motions influence our thoughts, and vice versa. The more gestures we make, the more fluent our thinking and speaking will be; the greater nuance and sophistication of our understanding. Have you ever watched someone give directions (without being able to hear them)? It's an impossible task to do without pointing or tracing your fingers. Here are some ways you can encourage the making of gestures:

In school, we do way too much “in our heads”; we would all be thinking more efficiently and effectively if we offloaded our cognitive processes more often. A quick look at the cognitive load theorywould suggest that 'freeing up' our cognitive resources plays an active role in enabling us to learn more effectively. This is a skill that can be cultivated, here are some ways I try to do so:

Experts who have difficulty teaching novices have "the curse of knowledge," which is when knowledge has become so automatic in their minds that they cannot explain it clearly to others. I am trying to keep in mind, as a teacher, that the curse of expertise applies to me. Chip and Dan Heathwrite about this topic in detail, once you are aware of the phenomenon, you'll immediately change your classroom practice.

1. What is the Extended Mind Theory?

The Extended Mind Theory, proposed by David Chalmers, suggests that human minds and mental processes are not confined within our brains but can extend into the environment. This cognitive extension implies that tools, objects, and even other people can become part of our minds. Research has explored this fascinating concept in depth.

2. How does the Extended Mind Hypothesis relate to social cognition?

The Extended Mind Hypothesis has significant implications for social cognition. It suggests that our understanding of others' minds can be influenced by our continuous interaction with them and our shared environment. This perspective can offer novel explanations of cognition in social contexts.

3. What does mental extension mean in the context of the Extended Mind Thesis?

Mental extension refers to the idea that our mental processes can extend beyond our brains into the external world. This could include using a notebook as an extension of our memory or a computer as an extension of our problem-solving abilities.

4. How does the Extended Mind Theory impact teaching and learning?

The Extended Mind Theory can transform our understanding of teaching and learning. It suggests that learning is not just an internal process but involves continuous interaction with others and the environment. This perspective can inform the development of teaching strategies that use these external resources.

5. What are the criticisms of the Extended Mind Theory?

While the Extended Mind Theory offers a unique perspective on cognition, it's not without criticism. Some argue that it overstates the role of external factors in cognition. Others question whether tools and objects can truly become part of our minds. Despite these debates, the Extended Mind Theory continues to stimulate thought-provoking discussions in cognitive science.

For a deeper dive into the Extended Mind Theory, you may refer to these research articles: Pressing the Flesh: A Tension in the Study of the Embodied, Embedded Mind?*, Extended emotion, From Wide Cognition to Mechanisms: A Silent Revolution, and The extended cognition thesis: Its significance for the philosophy of (cognitive) science.

scaffolding cognitive processes">

scaffolding cognitive processes">

The extended mind hypothesis, as proposed by Andy Clark and David Chalmers, has significant implications for understanding cognition. Key studies defend the hypothesis against criticisms, explore the nature of cognitive coupling with the environment, and discuss the broader implications for cognitive science. These studies highlight the importance of considering external objects and environments as integral parts of cognitive processes.

1. Extended Mind as a Different Way to realise Cognition

This paper responds to criticisms of the extended mind hypothesisby addressing the objections related to the distinctiveness of external cognitive states and the claim that the extended mind is not as groundbreaking as initially thought. It argues that the significance of the extended mind hypothesis lies in its rethinking of cognition and its relationship to the external environment (Meriç, 2022).

2. The Mark of the Cognitive and the Coupling-Constitution Fallacy: A defence of the Extended Mind Hypothesis

This study defends the extended mind hypothesis against criticisms that it conflates coupling with constitution and lacks a clear mark of the cognitive. It argues that coupling relations between agents and environmental resources are central to understanding cognitive systems and that the criticisms fail to undermine the extended cognition thesis (Piredda, 2017).

3. What is the Extension of the Extended Mind?

This paper explores the details of functional coupling between organisms and external entities in the environment, drawing parallels with theories in biology such as environmental constructivism and niche construction. It argues that instances of environmental coupling are constitutive of cognitive functions and that natural environmental features play a crucial role in extended cognition (Greif, 2015).

4. Intrinsic Content, Active Memory and the Extended Mind

This work addresses the criticism that external structures cannot support intrinsic content, a key mark of cognitive processes. It argues that concerns about intrinsic content are unfounded and do not compromise the extended mind hypothesis. The paper also discusses the broader implications of extended mind theory for understanding cognition (Clark, 2005).

5. Extended Cognition and the Extended Mind: Introduction

This introduction to a special issue on extended cognition and the extended mind provides an overview of the extended mind thesis by Andy Clark and David Chalmers. It discusses various aspects of the extended mind hypothesis and its implications, arguing for a broader understanding of cognitive processes that includes external structures and environments (Bartlett, 2016).

These studies provide the philosophical and cognitive science foundation for the extended mind thesis and its educational implications.

The Extended Mind 8,500+ citations

Clark, A. and Chalmers, D. J. (1998)

This seminal paper introduces the extended mind hypothesis, arguing that cognitive processes can extend beyond the brain into the external environment. Using the famous Otto and Inga thought experiment, Clark and Chalmers demonstrate that notebooks, tools, and technologies can function as genuine components of the mind. For educators, this challenges the assumption that learning must happen entirely "in the head."

Supersizing the Mind: Embodiment, Action, and Cognitive Extension 2,200+ citations

Clark, A. (2008)

Clark expands the extended mind thesis, providing extensive evidence from cognitive science, robotics, and neuroscience. The book argues that human cognition is fundamentally designed to integrate with tools and environments. Teachers can apply this insight by recognising that graphic organisers, manipulatives, and collaborative discussions are cognitive tools that genuinely extend student thinking rather than mere aids.

The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain 350 citations

Paul, A. M. (2021)

Annie Murphy Paul translates the extended mind research into practical applications, demonstrating how thinking with the body, physical spaces, and other people produces better outcomes than thinking in isolation. The book draws on classroom research showing that movement, gesture, and environmental design directly affect learning quality. Teachers will find the chapters on collaborative cognition particularly relevant.

Embodied Cognition and Education: Possibilities and Limitations 1,400+ citations

Wilson, M. (2002)

Wilson's review examines six claims about embodied cognition, evaluating the evidence for each. The paper demonstrates that cognition is situated, time-pressured, and offloaded onto the environment. For classroom practice, this supports the use of physical manipulatives, collaborative problem-solving, and learning environments designed to support rather than hinder cognitive processes.

Distributed Cognition as a Framework for Understanding Learning 1,800+ citations

Hutchins, E. (1995)

Hutchins' landmark work shows that cognitive processes are distributed across individuals, tools, and social structures. His research on ship navigation demonstrates that group cognition can accomplish what no individual mind could manage alone. Teachers can apply this by designing collaborative tasks where the thinking is genuinely distributed across the group rather than replicated by each member individually.

The Extended Mind Theory, proposed by philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers in 1998, argues that cognition doesn't only happen inside the brain but can extend into our tools, technologies, and environments. For educators, this means that classroom environments, available tools, and collaborative relationships don't merely support thinking but can actually become part of the thinking process itself. Understanding this theory helps teachers recognise that a calculator or notebook isn't 'cheating' but rather a genuine extension of a child's cognitive abilities.

Research shows that gesturing creates a cognitive loop where hand motions influence thoughts and vice versa, making thinking more fluent and sophisticated. Teachers can model this by using their hands to explain their thinking and encouraging students to 'add shape to their thoughts' or 'use your hands to explain your thinking.' Having relevant artefacts nearby naturally encourages more gesturing, so tools like visual scaffolds can help students explain their cognitive processes whilst reducing mental burden.

Cognitive offloading involves moving mental processes outside our heads to free up brain capacity for higher-level thinking like analysis and reflection. Teachers can implement this by explicitly teaching about cognitive load theory and using graphic organisers and diagrams to help students externalise their thoughts into shared spaces. This approach recognises that the brain evolved for specific tasks and needs external support for abstract thinking and long-term memory retention.

The curse of expertise occurs when teachers' knowledge has become so automatic that they struggle to explain it clearly to novices, as described by Chip and Dan Heath. Teachers can overcome this by making their thinking processes visible through cognitive apprenticeship, explicitly explaining their thought processes when modelling tasks like editing work. Breaking learning into small, manageable steps and naming internal learning processes helps students understand what to do and how to think about it.

The theory challenges the brain-centric culture that views intelligence as innate, individual, and internal by showing that cognition is shaped by action, experience, and external tools. This perspective recognises that apparent differences in ability often reflect the limits of everyone's brain rather than individual intelligence differences. For educators, this means focusing on using the brain's natural strengths in sensing, moving, and social interaction rather than forcing it to work harder in isolation.

Simple examples include using fingers to count, writing ideas on paper, or using calculators for mathematical reasoning, all of which extend cognitive boundaries through external resources. Teachers can encourage the use of Writer's Block scaffolding tools to help students explain their thinking processes and provide opportunities for improvisation, which naturally increases gesturing and cognitive offloading. The key is recognising these tools as genuine parts of the thinking process rather than mere aids or shortcuts.

Classroom environments should provide relevant artefacts and tools that naturally encourage gesturing and externalising thoughts, such as visual organisers and collaborative spaces. The physical space should support movement and social interaction, using the brain's natural strengths rather than forcing students to sit still and work in isolation. Creating shared spaces where students can work with their externalised thoughts more effectively transforms the environment into an active part of the cognitive process.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/what-is-the-extended-mind#article","headline":"The Extended Mind Theory: How Our Environment Shapes Thinking","description":"Explore the extended mind thesis and its implications for education. Discover how tools, environments, and other people extend our cognitive capacities...","datePublished":"2021-06-07T17:06:15.369Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/what-is-the-extended-mind"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a3bb63a45c50be280173a_696a3bb1d328a91d213daae4_what-is-the-extended-mind-illustration.webp","wordCount":2464},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/what-is-the-extended-mind#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"The Extended Mind Theory: How Our Environment Shapes Thinking","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/what-is-the-extended-mind"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/what-is-the-extended-mind#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is the Extended Mind Theory and why should educators care about it?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The Extended Mind Theory, proposed by philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers in 1998, argues that cognition doesn't only happen inside the brain but can extend into our tools, technologies, and environments. For educators, this means that classroom environments, available tools, and collaborativ"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers use gestures and movement to enhance student learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Research shows that gesturing creates a cognitive loop where hand motions influence thoughts and vice versa, making thinking more fluent and sophisticated. Teachers can model this by using their hands to explain their thinking and encouraging students to 'add shape to their thoughts' or 'use your ha"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What is cognitive offloading and how can it be implemented in the classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Cognitive offloading involves moving mental processes outside our heads to free up brain capacity for higher-level thinking like analysis and reflection. Teachers can implement this by explicitly teaching about cognitive load theory and using graphic organisers and diagrams to help students external"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What is the 'curse of expertise' and how does it affect teaching?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The curse of expertise occurs when teachers' knowledge has become so automatic that they struggle to explain it clearly to novices, as described by Chip and Dan Heath. Teachers can overcome this by making their thinking processes visible through cognitive apprenticeship, explicitly explaining their "}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How does Extended Mind Theory challenge traditional views about intelligence and ability?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The theory challenges the brain-centric culture that views intelligence as innate, individual, and internal by showing that cognition is shaped by action, experience, and external tools. This perspective recognises that apparent differences in ability often reflect the limits of everyone's brain rat"}}]}]}