Neurodiversity in the classroom

Discover practical strategies to support neurodiverse learners and create an inclusive, responsive classroom for every student.

Discover practical strategies to support neurodiverse learners and create an inclusive, responsive classroom for every student.

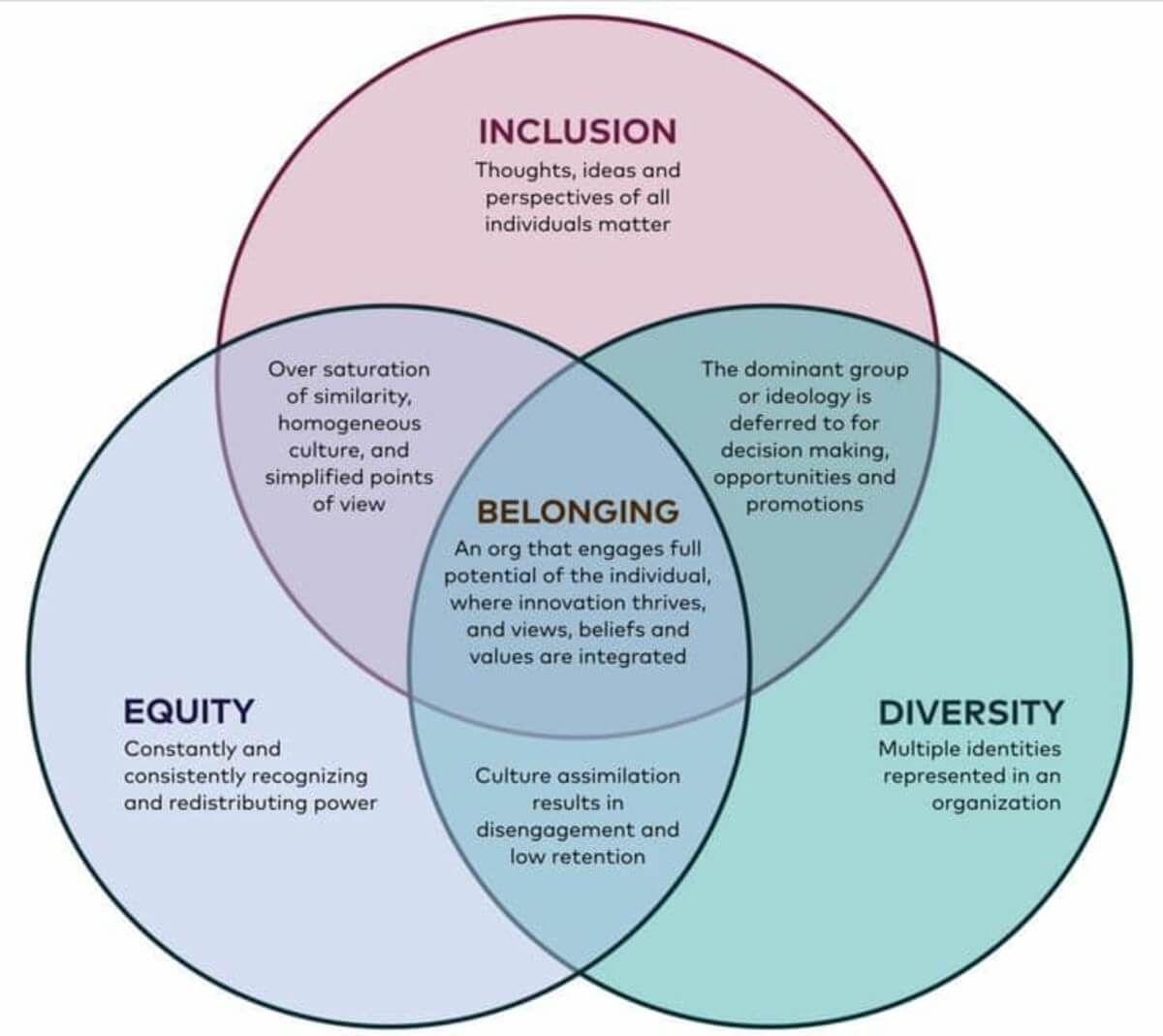

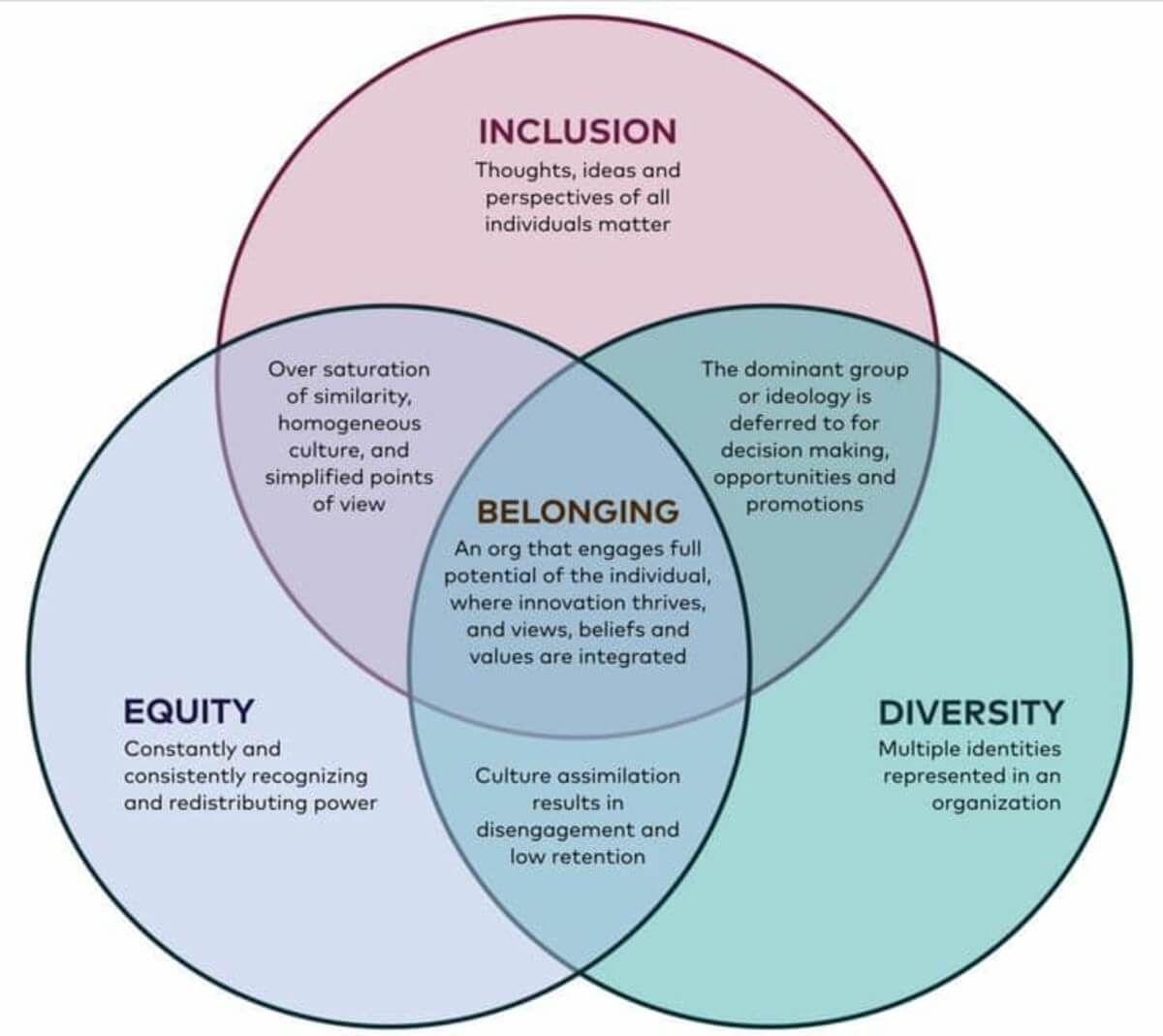

Education is no longer about a one-size-fits-all model; it's about adapting to the varied learning needs of every student. Embracing neurodiversity (AI tools for neurodiverse learners) in education not only benefits neurodivergent students but enriches the learning experience for all students by promoting creativity, innovation, and empathy. As classrooms become more inclusive, they creates environments where every student's uniqueness is celebrated and encouraged to flourish.

This article explores transformative classroom practices that can redefine how we perceive education through a neurodiverse lens. From shifting mindsets about diverse learning styles to implementing flexible teaching strategies, educators have the tools to cultivate inclusive environments. Join us as we examine into how these practices not just reshape classroom dynamics but also prepare students for a world that values diverse perspectives.

Neurodiversity celebrates the natural variations in how people think and process information. This concept includes conditions like autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, and dyslexia. Understanding neurodiversity and SEN emphasises recognising and appreciating these neurological differences.

Key Features of Neurodiversity:

The goal is to accept individual needs without judgment. By acknowledging both the differences and challenges, we can better support neurodivergent people. This involves celebrating their unique strengths and creating supportive and inclusive environments.

In schools, this means tailoring education to meet diverse learning needs. An inclusive classroom benefits everyone by reflecting a wide range of human diversity. Cultivating an inclusive environment can improve the learning experience for both neurodivergent learners and neurotypical students. This approach creates a supportive school community, enhancing each student's opportunity to succeed.

Neurodiversity in education benefits all students by creating inclusive environments that celebrate different learning styles and cognitive approaches. When teachers embrace neurodivergent students' unique strengths, it promotes creativity, innovation, and empathy throughout the entire classroom. This approach moves beyond traditional one-size-fits-all models to unlock every student's potential.

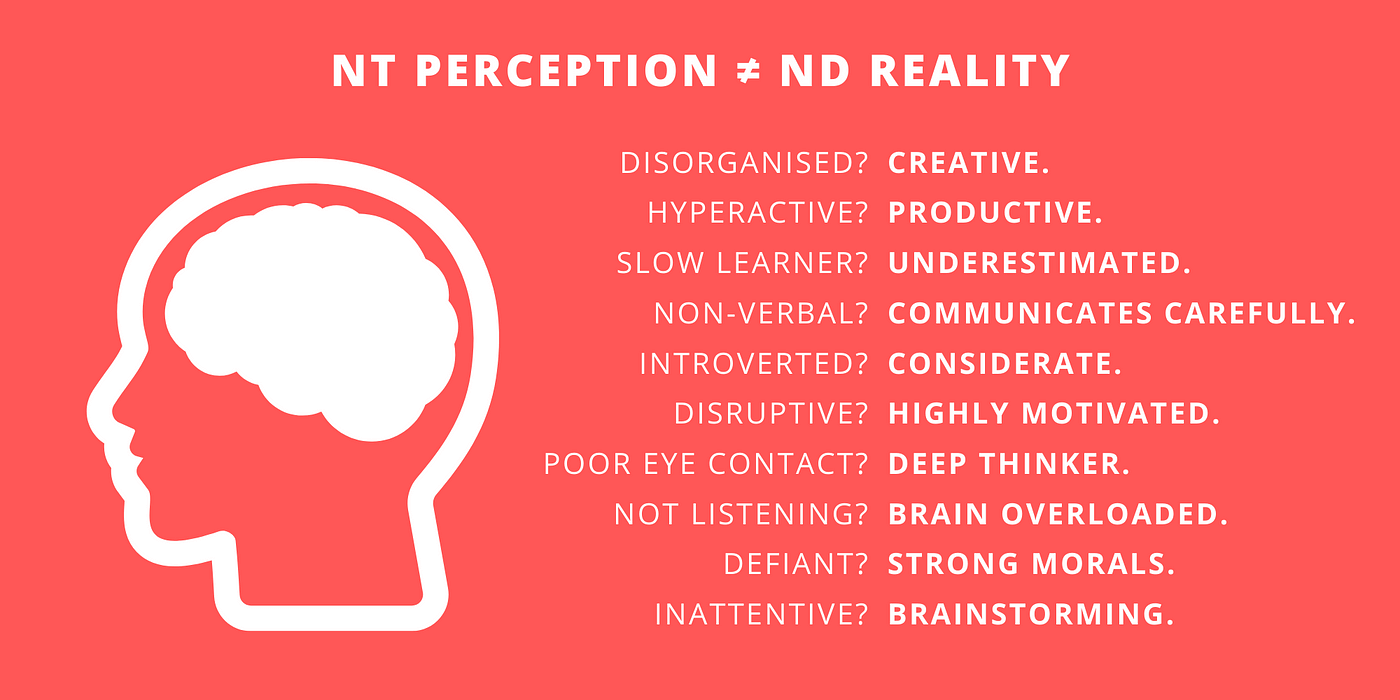

Embracing neurodiversity in education acknowledges the unique strengths and challenges of individuals with neurological differences, such as autism, ADHD, and dyslexia. The neurodiversity movement advocates for recognising neurological differences as natural variations, rather than deficits, akin to categories like ethnicity and gender.

Thomas Armstrong’s work emphasises that embracing neurodiversity can lead to recognising and unleashing the unique contributions of individuals with differently-wired brains. Effective inclusive classroom management relies on understanding and integrating neurodiversity to address the diverse needs of all learners. Creating a classroom environment that values neurodiversity requires proactive measures, such as involving social scaffolding to support neurodivergent students, particularly during social activities.

Teaching about neurodiversity in the classroom helps neurodivergent students feel included and understood by their peers, reducing social isolation. This understanding encourages a sense of camaraderie and acceptance, which can be pivotal for their emotional well-being. Implementing relaxation exercises and creating a calming classroom atmosphere can significantly alleviate anxiety for neurodivergent students, developing better learning readiness. These strategies help provide a nurturing space that supports learning.

Recognizing and nurturing the unique strengths and talents of neurodivergent students, such as creativity and problem-solving abilities, helps build their self-confidence and engagement. Encouraging these skills allows them to shine in areas they feel passionate about. Tailoring teaching strategies to fit the diverse needs of neurodivergent students promotes an inclusive classroom environment that values each student's potential. This personalized approach can make learning more effective and enjoyable.

The neurodiversity paradigm promotes the acceptance of neurological differences as natural variations, helping neurodivergent students to thrive by emphasising their individual strengths. By shifting focus from limitations to possibilities, educators can unlock the full potential of each student, allowing them to contribute meaningfully to the classroom setting.

Embracing neurodiversity in the classroom encourages educators to recognise the unique strengths and contributions of individuals with neurological differences, promoting a more inclusive learning environment. This teaching approach supports all learners by introducing them to varied perspectives and problem-solving methods. Recognizing neurodiversity allows all students to be appreciated for their distinctive abilities, developing a sense of belonging and validating diverse learning and behavioral styles. It helps to affirm that diversity enriches the learning community.

Understanding neurodiversity can help overcome the challenges that neurodiverse students face, enabling them to thrive in educational settings that traditionally did not accommodate their needs. This environment supports a positive educational journey for everyone involved. Educators who adopt neurodiversity principles in teaching practices contribute to societal change by valuing human diversity, potentially improving academic and social outcomes for all students.

Addressing the unique needs of neurodiverse students by creating accommodating environments can enhance the overall classroom experience. Both neurodiverse and neurotypical students benefit from exposure to diverse perspectives and teaching methods. This inclusive approach prepares students for real-world situations, where working alongside a diverse group is often required and valued.

Teachers can recognise neurodiversity through careful observation of learning patterns, social interactions, and sensory responses without waiting for formal diagnoses. Key indicators include different processing speeds, unique problem-solving approaches, and varied attention spans or focus preferences. Effective recognition focuses on identifying strengths and learning profiles rather than deficits.

Neurodivergence shows up in many forms, and recognising these profiles helps educators respond to the individual rather than rely on labels. By observing how different learners engage with tasks, communicate, and navigate their environments, teachers can adapt support to build on strengths and address challenges. Below are common neurodivergent profiles educators may encounter, along with tailored strategies to promote inclusion and growth.

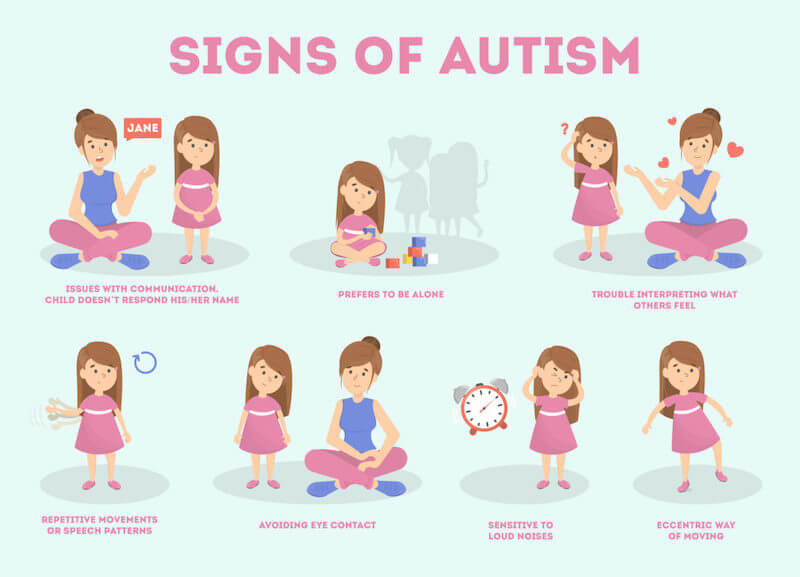

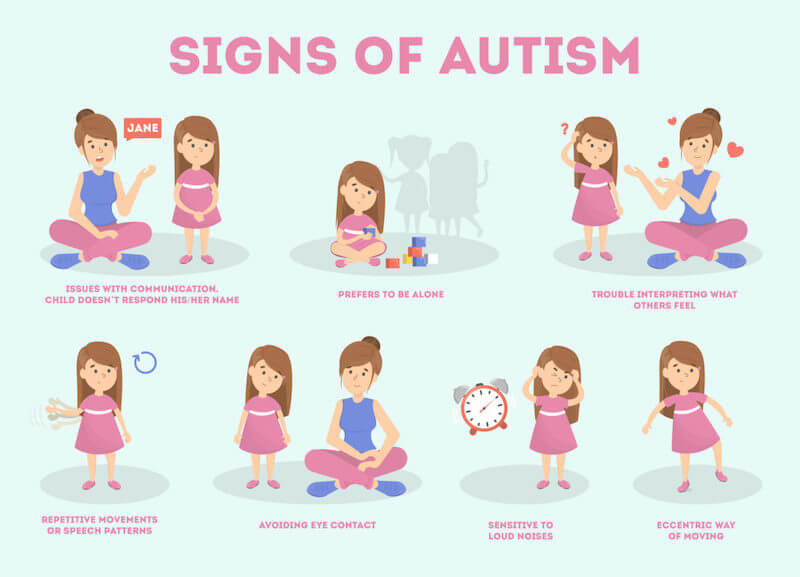

1. Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC)

Students with ASC may prefer predictable routines, benefit from low-stimulus environments, and find abstract language or group dynamics challenging. Structured visuals, sensory rooms, and predictable transitions reduce anxiety. Lego therapy and sand tray therapy can support social interaction and emotional expression through play and storytelling.

2. Attention DeficitHyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

ADHD affects impulse control, focus, and working memory. Learners may need movement, novelty, and clear boundaries. Use trauma-informed sensory circuits, visual timers, and task chunking to support regulation and productivity. Seating near the teacher and flexible task completion options help maintain engagement.

3. Dyslexia

Dyslexia impacts reading and spelling but is often paired with creative thinking and oral storytelling strengths. Use multisensory phonics, coloured overlays, and audio tools to support literacy. Colourful semantics can also support sentence construction and comprehension through visual scaffolds.

4. Dyspraxia (DCD)

Students with dyspraxia may struggle with motor planning and coordination. Visual step-by-step guides, concrete task modelling, and breaking activities into manageable chunks can reduce overload. Allow alternative ways to record work (e.g. Voice notes or typing) and provide tools like pencil grips or sloped boards.

5. Dyscalculia

Learners with dyscalculia benefit from tangible, abstract-to-concrete learning approaches. Use number lines, counting cubes, and real-life contexts to build number sense. Consistent visual models and hands-on practice are key to developing confidence and fluency.

6. Dysgraphia

This profile affects handwriting and the organisation of written work. Offer speech-to-text tools, graphic organisers, and extra time for tasks. Incorporate multisensory pre-writing activities, and focus on reducing cognitive loadby separating planning and transcription stages.

7. Tourette Syndrome

Tics are involuntary and often exacerbated by stress. Maintain a calm, understanding tone and avoid drawing attention to them. Provide private breaks if needed and educate peers to creates acceptance. Offer quiet corners or sensory toolkits to help with self-regulation.

8. Sensory Processing Differences

These learners may be over- or under-responsive to stimuli. Introduce sensory rooms, flexible seating, and trauma-informed sensory circuits for grounding. Fidget tools, noise-cancelling headphones, and dimmable lights can make the classroom more accessible.

9. Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA)

PDA learners experience anxiety in response to demands. Avoid power struggles by using low-arousal communication, humour, and collaborative choices. Sand tray and play-based methods like Lego therapy can offer indirect but meaningful routes to learning.

By recognising and supporting neurodiverse learners through flexible, sensory-aware, and play-based strategies, educators create inclusive classrooms where every student can thrive, academically and socially and emotionally too.

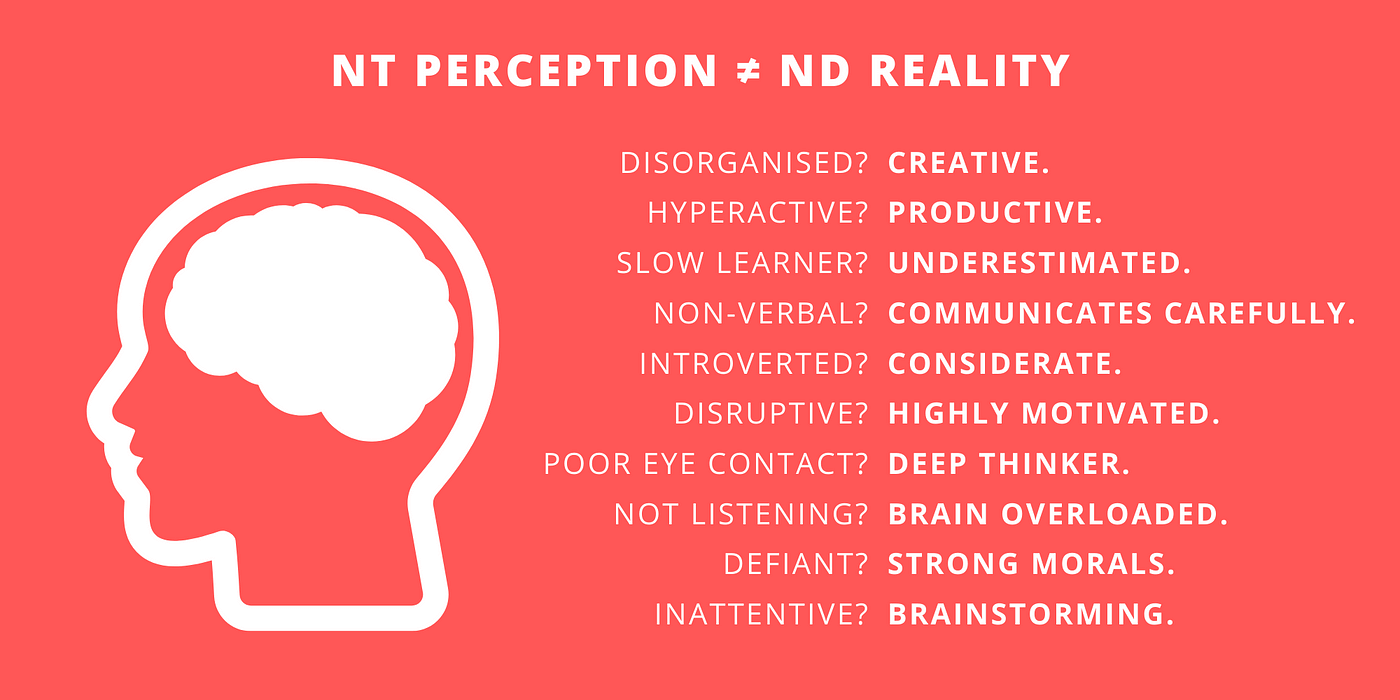

Teachers need to shift from viewing neurodivergent traits as problems to fix toward celebrating them as natural variations that bring valuable perspectives. This involves moving beyond deficit-based thinking to strength-based approaches that recognise hidden talents and alternative ways of learning. The key change is seeing diversity as an advantage rather than a challenge to overcome.

In recent years, educational practices have embraced a shift towards recognising the uniqueness of every brain. This mindset change is crucial for creating classroom environments where all students, including neurodiverse students, can thrive. Instead of viewing accommodations as optional extras, they should be seen as beneficial for everyone. This encourages educators to view all students as capable learners with unique strengths and potential.

By developing an inclusive environment, schools can enhance inclusivity in education and promote a sense of belonging. Implementing systems for nonverbal assistance and alternatives to public speaking helps reduce anxiety. This promotes independence and adaptability, allowing neurodivergent learners to feel more comfortable and engaged. Embracing neurodiversity means moving beyond mere accommodations; it celebrates differences and improves educational experiences for all students.

Traditional compliance-based assessment methods can sometimes hinder the potential of neurodivergent students. These methods often focus too much on memorization and standardised tests. Moving beyond this approach means recognising the individuality of students and finding alternative assessment strategies. Portfolio assessments, project-based learning, and self-reflection give students the chance to demonstrate their knowledge in diverse ways.

This not only highlights their unique strengths but also provides a richer understanding of their abilities. In an inclusive education setting, neurodivergent and neurotypical students alike benefit from these varied assessment methods. They creates creativity, critical thinking, and self-confidence. Shifting the focus towards these methods not only aids neurodivergent people but enhances the classroom experience for all, creating a truly inclusive classroom environment.

Effective strategies include flexible instruction methods, multi-sensory learning approaches, and providing multiple ways for students to demonstrate knowledge. Visual aids, structured routines, and choice in learning activities help accommodate different processing styles and attention spans. These adaptations benefit all learners while specifically supporting neurodivergent students' success.

Transformative teaching strategies prioritise personalized learning, which emphasises the talents and problem-solving skills of neurodivergent individuals. These approaches cultivate a growth mindset, enhancing motivation and engagement for students with autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other neurological conditions. An inclusive classroom doesn't just support neurodivergent learners but enriches the learning process for everyone by promoting human diversity. Through these methods, educators creates a supportive environment that values every student's contributions.

Visual supports are essential tools in an inclusive learning environment. They aid neurodivergent learners in grasping and retaining concepts by illustrating information visually. Pictures, diagrams, and color-coding help make abstract ideas more tangible. These tools can improve comprehension by linking structured language with engaging visuals. Offering information in multiple formats, verbal, written, and visual, is vital for reinforcing learning for all students. This approach caters to different learning styles and enhances everyone's understanding. For neurodivergent students, using a graphic syllabus, as well as charts and graphs, can make complex ideas stick. Visual learning tools, like multimedia presentations, can engage students who might struggle with auditory information, ensuring that the learning environment is truly inclusive.

Flexible seating arrangements contribute to an inclusive classroom setting by addressing the sensory needs of neurodivergent students. Standing desks, exercise balls, and beanbags allow for gentle movement, which can be crucial for focus and comfort. Allowing students to choose between different seating options helps cater to diverse sensory needs, decreasing behavioral issues and enhancing engagement. Preferential seating enables neurodivergent students to sit where they can focus best, such as closer to the teacher or away from distractions. Employing universal design principles, including flexible seating, benefits all students. It caters to both diagnosed and undiagnosed needs, providing an environment that supports a wide range of learning preferences and needs.

Multi-modal teaching approaches enhance inclusivity in neurodiverse classrooms by integrating various learning techniques. These methods include visual, auditory, and kinesthetic approaches, providing alternatives to traditional learning. Incorporating different teaching methods can reduce anxiety for neurodivergent students, making learning more engaging. By offering nonverbal communication options and personalized learning supports, teachers can create a more predictable and stable learning environment. Multi-modal strategies help develop organisational skills and time management by tailoring tasks to individual learningstyles. By embracing these approaches, educators creates a classroom culture that not only accommodates but celebrates neurodiversity. This enriching environment benefits all students, acknowledging and embracing human diversity in education.

Create inclusive environments by establishing clear routines, reducing sensory overload, and offering quiet spaces for students who need breaks. Flexible seating options, visual schedules, and calm-down corners help accommodate different sensory and attention needs. Small environmental changes like adjusting lighting and minimising distractions can significantly impact all students' learning experiences.

An inclusive learning environment embraces the diversity of our student population. It recognises a natural range of variations in how people think and learn. This is essential for supporting neurodiverse students. Effective classroom strategies involve understanding these differences. Neurotypical and neurodivergent students may differ in how they process information and interact socially.

By focusing on the strengths and challenges each student has, we can create supportive spaces. Flexible management strategies, like positive reinforcement, help students thrive. In places like the UK, resources such as LEANS raise awareness about neurodiversity. They work to integrate this understanding into schools, helping all students appreciate individual differences.

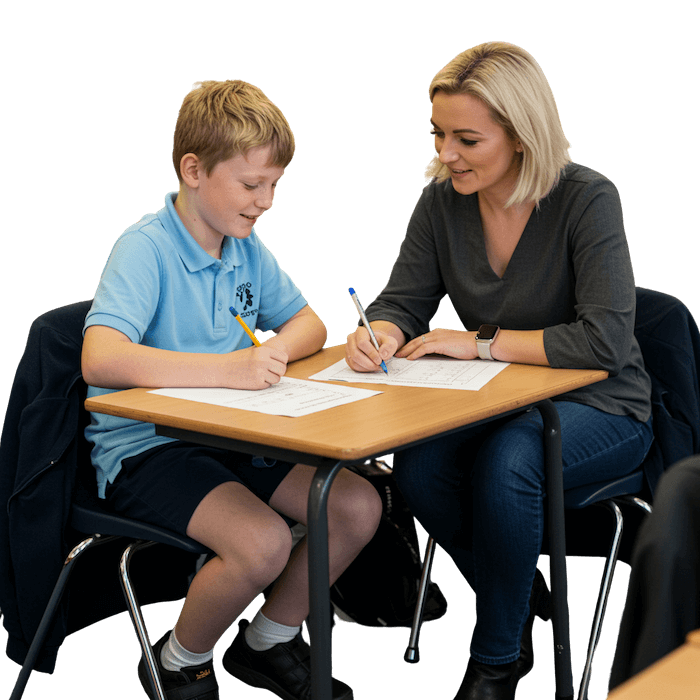

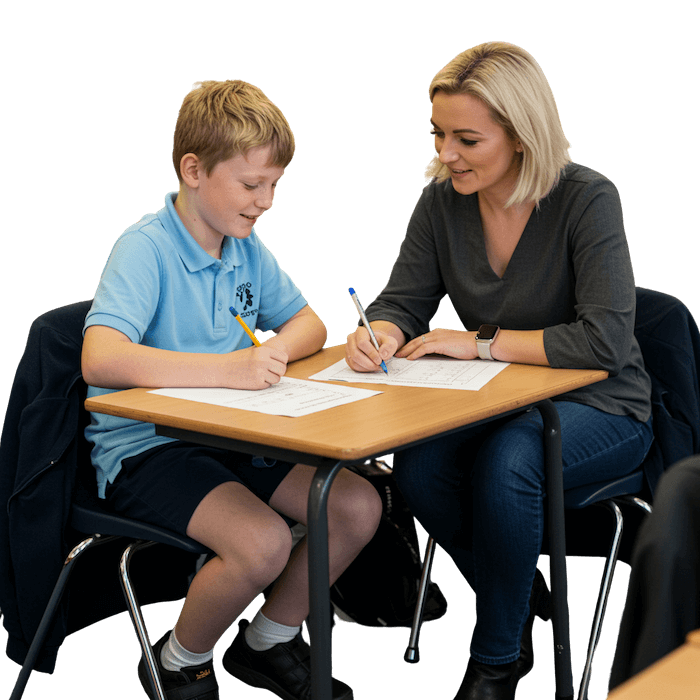

Teachers play a crucial role in developing inclusive education. They should work with students, families, and colleagues to craft supportive environments. Recognizing diverse strengths is vital for students’ success. Professional learning offers teachers a chance to adapt and create accommodations suited for neurodivergent learners.

Collaborating in teams, with both general and special education teachers, can enhance learning through peer support. Teachers can benefit from including statements about accommodations in their syllabi. This practice emphasises accessibility and ensures neurodivergent students know the support available. By being adaptable and aware, teachers create classrooms where all students can excel.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) provides a comprehensive framework that offers multiple means of representation, engagement, and expression. The SAMR model helps integrate technology to support diverse learning needs and processing styles. These frameworks emphasise proactive planning that anticipates and accommodates learning differences from the start.

Educators play a crucial role in creating an inclusive classroom setting. A practical framework tailored to neurodiverse students can enhance their educational encounter. Educators can use manipulatives and interactive lessons, which help in understanding and retention for neurodivergent learners. Establishing predictable routines is essential for neurodivergent children, especially those with ADHD, as it helps them stay focused during the school day. Flexible seating arrangements and movement breaks are also vital. They assist in maintaining engagement and concentration. Incorporating universal design features and flexibility creates an inclusive environment. This approach supports neurodivergent people effectively. Building positive relationships with students and involving parents strengthens support systems for neurodivergent learners. Such practices ensure that neurodivergent students have a fulfiling opportunity in their education.

Developing personalized learning plans is key to meeting the unique needs of neurodiverse learners. These plans should consider each student's social cues and triggers to prevent distress. Tailored lesson plans ensure educational content accommodates various neurodivergent conditions. Educators should work closely with students, parents, and staff to create inclusive environments. This collaboration recognises each student's learning preferences and strengths. Adjusting curricula by modifying workloads can boost engagement and accessibility. Personalized instruction helps neurodivergent learners thrive. By adapting teaching strategies to align with wide-ranging learning styles, educators can develop effective plans. This approach enables students, including autistic students, to reach their full potential and enjoy a more enriching school experience.

Encouraging peer support systems in schools creates an inclusive atmosphere for neurodivergent students. Collaborative team teaching can be effective. It unites general and special education teachers to creates inclusive learning environments. Group work also encourages collaboration among students. These activities make learning meaningful and increase student engagement. Positive reinforcement is another tool that enhances peer support. Recognizing achievements boosts self-esteem and motivation among neurodiverse learners. This recognition enriches classroom dynamics, promoting supportive peer interactions. Teachers can further aid students by matching those with complementary skills. This method allows learners to benefit from each other's strengths. Such collaborations make classroom environments more inclusive and supportive, offering equal learning opportunities to all students.

Address resistance by sharing research on improved outcomes for all students when neurodiversity practices are implemented. Start with small, manageable changes that demonstrate clear benefits before introducing larger systemic shifts. Professional developmentand peer collaboration help build confidence and competence in inclusive teaching methods.

In the educational landscape, embracing neurodiversity involves a significant shift in understanding. This paradigm recognises neurological differences as natural and valuable. However, implementing this shift in schools presents challenges. Educators must overcome resistance and misconceptions that arise. Ensuring meaningful inclusion requires everyone, teachers, students, and staff, to appreciate diverse experiences. This approach reduces barriers like bullying and isolation. Additionally, effective collaboration among school staff is crucial. Co-teachers must build relationships based on respect and trust to address diverse learning needs. A neurodiversity-affirming classroom demands a gradual change in mindset. It involves valuing both the strengths and struggles of neurodiverse students. Creating such an environment is not immediate and requires shared commitment from educators.

Neurodiversity shifts the focus from seeing neurological differences as deficits to celebrating them as natural variations. This approach challenges traditional views, promoting a more inclusive understanding. The movement de-stigmatizes neurodivergence, developing acceptance and self-awareness. Recognizing neurodiversity as part of human diversity is crucial. It is akin to how society views ethnicity or gender, encouraging inclusive practices. Educators are key players in this transformation. By valuing the strengths of neurodivergent students, they counter stigma and prejudice. Such efforts are vital in developing an environment where all learners thrive.

Measure success through multiple indicators including student engagement levels, academic progress across different learning styles, and classroom climate surveys. Track both quantitative data like test scores and qualitative observations such as student confidence and participation rates. Regular feedback from students, parents, and colleagues provides comprehensive insight into program effectiveness.

Embracing neurodiversity in the classroom creates a positive environment for all students. It allows each student to use their unique strengths, making them feel valued and supported. Teachers and school staff must share a commitment to these practices for them to be effective. Recognizing both the strengths and challenges of neurodiverse students is crucial in promoting their academic success. By nurturing skills like creativity and problem-solving, students build self-confidence and feel they belong.

Neurodiverse students often face unique challenges that can affect their classroom engagement. Sensory overload and social skills difficulties may hinder their participation in class activities. Teachers can employ strategies like positive reinforcement to boost self-esteem. This increases motivation and improves engagement. Group activities that pair complementary skills, such as creative and analytical thinkers, can also enhance learning. Educators play a pivotal role in accommodating diverse learning styles. Their efforts, combined with those of students, parents, and staff, create supportive environments. This teamwork results in improved engagement and academic success for neurodiverse students.

Neurodivergent students may encounter social challenges that impact their long-term development. Teachers who develop strong bonds with these students creates an inclusive environment. Such support can encourage self-acceptance and improve relationships. Structured routines in class help students with ADHD focus better and enhance their academic performance. When schools collaborate with parents, they gain insights into a child's unique needs. This partnership bridges home and school, supporting student growth. Incorporating diverse learning materials also enriches comprehension and creates a love for learning. These practices contribute to the overall development of neurodiverse students, supporting them throughout their education.

Essential resources include research-based books on Universal Design for Learning, professional development courses on inclusive education, and guidance from special education specialists. Online communities and educational organisations provide current strategies and peer support for implementing neurodiversity practices. Academic journals and case studies offer evidence-based approaches for different classroom contexts.

The following studies show how increasing awareness, building inclusive curricula, and promoting peer understanding can help neurodivergent children better adapt and succeed in school settings.

1. Learning About Neurodiversity at School (LEANS Programme)

Alcorn et al. (2024) evaluated the LEANS classroom programme, designed to teach mainstream primary pupils about neurodiversity. The programme significantly improved children’s understanding of neurodiversity and increased positive attitudes and intentions toward neurodivergent peers. This study demonstrates how structured whole-class interventions can create more inclusive and supportive classroom cultures.

2. Promoting Social-Inclusion Through the 'In My Shoes' Programme

Littlefair et al. (2024) adapted the Australian "In My Shoes" intervention for UK primary schools to enhance participation and school connectedness for neurodivergent students. Stakeholder feedback supported linking the programme to the PSHE curriculum and emphasised its role in developing emotional and social development among children aged 8-10.

3. Neurodiversity and Inclusive Education Through Music Therapy

Moya-Pérez et al. (2024) conducted a systematic review showing that music therapy interventions in early childhood education promote emotional regulation, communication, and social integration for neurodivergent students. The review supports the use of therapeutic and pedagogical strategies to enhance classroom inclusion and academic success.

4. Neurodivergent Students in English Language Lessons

Ubaque-Casallas (2024) reflected on teacher education practices supporting neurodivergent learnersin English language classrooms. The study highlights the shift from instrumental lesson planning to a more humanizing, inclusive pedagogy that acknowledges autism as a unique neurocognitive perspective.

5. Adolescents Advocating for Neurodiversity Through Design Thinking

Schuck and Fung (2024) studied a summer camp where high school students used Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Design Thinking to create neurodiversity advocacy projects. Results showed reduced stigma, especially toward autism, and increased knowledge, empathy, and peer collaboration among participants.

Neurodiversity celebrates natural variations in how people think and process information, including conditions like autism, ADHD, and dyslexia. Rather than viewing these differences as deficits to be 'fixed', neurodiversity emphasises recognising and appreciating neurological differences as natural variations similar to ethnicity and gender.

Teachers can identify neurodiversity through careful observation of learning patterns, social interactions, and sensory responses in the classroom. Key indicators include different processing speeds, unique problem-solving approaches, varied attention spans, and distinctive ways students engage with tasks and navigate their environment.

Teachers can implement relaxation exercises, create calming classroom atmospheres, and manage cognitive load to reduce anxiety for neurodivergent students. These small changes, such as providing flexible teaching strategies and tailored support, actually improve learning outcomes for the entire class whilst developing an inclusive environment.

Neurotypical students benefit from exposure to diverse perspectives, varied problem-solving methods, and different teaching approaches when neurodiversity is embraced. This inclusive environment promotes creativity, innovation, and empathy throughout the entire classroom whilst preparing all students for real-world situations where working alongside diverse groups is valued.

Neurodivergent students frequently demonstrate exceptional creativity, unique problem-solving abilities, and effective thinking approaches that can enrich classroom discussions and activities. Recognising and nurturing these distinctive talents helps build their self-confidence and engagement whilst contributing meaningfully to the learning community.

Teachers can move away from trying to 'fix' neurodivergent students by instead focusing on identifying and building upon their unique strengths and learning profiles. This approach involves emphasising individual potential rather than limitations, creating supportive environments that allow each student's distinctive abilities to flourish and contribute to classroom dynamics.

Social scaffolding provides structured support during social activities, helping neurodivergent students navigate peer interactions and group work more successfully. This proactive approach reduces social isolation and promotes inclusion by creating frameworks that enable neurodivergent students to participate meaningfully in collaborative learning experiences.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into neurodiversity in the classroom and its application in educational settings.

Navigating the liminal space: Enhancing film teaching through anonymous feedback, digital collages, and advocacy

Cayir et al. (2024)

This paper examines how a Graduate Teaching Assistant used anonymous feedback, digital collages, and advocacy strategies to create more inclusive seminars that accommodate diverse student needs and learning difficulties. It provides practical insights for educators working in challenging teaching environments to creates belonging and inclusivity. Teachers will find valuable strategies for adapting their approaches to better support neurodivergent students in their classrooms.

Differentiated Instruction as a Viable Framework for Meeting the Needs of Diverse Adult Learners in Health Professions Education 3 citations

Colbert et al. (2023)

This paper explores how differentiated instruction can be used as a framework to meet the diverse learning needs of adult learners in health professions education. It demonstrates how tailoring teaching methods to accommodate different learning styles and abilities can improve educational outcomes. Teachers can apply these differentiated instruction principles to create more inclusive classrooms that support neurodivergent students alongside their neurotypical peers.

A multi-perspective study of Perceived Inclusive Education for students with Neurodevelopmental Disorders 11 citations

Leifler et al. (2022)

This study investigates the perspectives of autistic and neurodivergent students, their caregivers, and teachers regarding educational inclusion by examining seventeen student-caregiver-teacher triads. The research explores areas of consensus and disagreement about what constitutes effective inclusive education for neurodivergent students. Teachers will gain valuable insights into how different stakeholders view inclusion, helping them understand multiple perspectives when designing support strategies for neurodivergent learners.

Research exploring neurodivergent student experiences in higher education 14 citations (Author, Year) through an ecological systems theory perspective reveals important insights into how autism and ADHD students navigate access and inclusion challenges within university environments, highlighting the complex interplay between individual needs and institutional support systems.

Butcher et al. (2024)

This paper examines the experiences of neurodivergent students with autism and ADHD in higher education, identifying systemic barriers that create challenges for accessibility and inclusivity in learning environments. The study uses ecological systems theory to understand how various environmental factors impact neurodivergent students' educational experiences. Teachers can learn about the specific challenges neurodivergent students face and discover evidence-based accommodations and staff approaches that improve accessibility and inclusion.

This systematic review examining Universal Design for Learning in teacher education 11 citations (Author, Year) analyses how UDL principles are integrated into teacher preparation programmes and their effectiveness in developing inclusive pedagogical practices amongst pre-service educators.

Fuente-González et al. (2025)

This systematic review examines how Universal Design for Learning is being integrated into teacher education programs and its effectiveness in preparing educators to support all students. UDL is an educational approach that aims to improve learning for all students by providing multiple means of engagement, representation, and expression without requiring significant curriculum modifications. Teachers will understand how UDL principles can be applied in their practice to create naturally inclusive classrooms that benefit neurodivergent students and all learners.

Education is no longer about a one-size-fits-all model; it's about adapting to the varied learning needs of every student. Embracing neurodiversity (AI tools for neurodiverse learners) in education not only benefits neurodivergent students but enriches the learning experience for all students by promoting creativity, innovation, and empathy. As classrooms become more inclusive, they creates environments where every student's uniqueness is celebrated and encouraged to flourish.

This article explores transformative classroom practices that can redefine how we perceive education through a neurodiverse lens. From shifting mindsets about diverse learning styles to implementing flexible teaching strategies, educators have the tools to cultivate inclusive environments. Join us as we examine into how these practices not just reshape classroom dynamics but also prepare students for a world that values diverse perspectives.

Neurodiversity celebrates the natural variations in how people think and process information. This concept includes conditions like autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, and dyslexia. Understanding neurodiversity and SEN emphasises recognising and appreciating these neurological differences.

Key Features of Neurodiversity:

The goal is to accept individual needs without judgment. By acknowledging both the differences and challenges, we can better support neurodivergent people. This involves celebrating their unique strengths and creating supportive and inclusive environments.

In schools, this means tailoring education to meet diverse learning needs. An inclusive classroom benefits everyone by reflecting a wide range of human diversity. Cultivating an inclusive environment can improve the learning experience for both neurodivergent learners and neurotypical students. This approach creates a supportive school community, enhancing each student's opportunity to succeed.

Neurodiversity in education benefits all students by creating inclusive environments that celebrate different learning styles and cognitive approaches. When teachers embrace neurodivergent students' unique strengths, it promotes creativity, innovation, and empathy throughout the entire classroom. This approach moves beyond traditional one-size-fits-all models to unlock every student's potential.

Embracing neurodiversity in education acknowledges the unique strengths and challenges of individuals with neurological differences, such as autism, ADHD, and dyslexia. The neurodiversity movement advocates for recognising neurological differences as natural variations, rather than deficits, akin to categories like ethnicity and gender.

Thomas Armstrong’s work emphasises that embracing neurodiversity can lead to recognising and unleashing the unique contributions of individuals with differently-wired brains. Effective inclusive classroom management relies on understanding and integrating neurodiversity to address the diverse needs of all learners. Creating a classroom environment that values neurodiversity requires proactive measures, such as involving social scaffolding to support neurodivergent students, particularly during social activities.

Teaching about neurodiversity in the classroom helps neurodivergent students feel included and understood by their peers, reducing social isolation. This understanding encourages a sense of camaraderie and acceptance, which can be pivotal for their emotional well-being. Implementing relaxation exercises and creating a calming classroom atmosphere can significantly alleviate anxiety for neurodivergent students, developing better learning readiness. These strategies help provide a nurturing space that supports learning.

Recognizing and nurturing the unique strengths and talents of neurodivergent students, such as creativity and problem-solving abilities, helps build their self-confidence and engagement. Encouraging these skills allows them to shine in areas they feel passionate about. Tailoring teaching strategies to fit the diverse needs of neurodivergent students promotes an inclusive classroom environment that values each student's potential. This personalized approach can make learning more effective and enjoyable.

The neurodiversity paradigm promotes the acceptance of neurological differences as natural variations, helping neurodivergent students to thrive by emphasising their individual strengths. By shifting focus from limitations to possibilities, educators can unlock the full potential of each student, allowing them to contribute meaningfully to the classroom setting.

Embracing neurodiversity in the classroom encourages educators to recognise the unique strengths and contributions of individuals with neurological differences, promoting a more inclusive learning environment. This teaching approach supports all learners by introducing them to varied perspectives and problem-solving methods. Recognizing neurodiversity allows all students to be appreciated for their distinctive abilities, developing a sense of belonging and validating diverse learning and behavioral styles. It helps to affirm that diversity enriches the learning community.

Understanding neurodiversity can help overcome the challenges that neurodiverse students face, enabling them to thrive in educational settings that traditionally did not accommodate their needs. This environment supports a positive educational journey for everyone involved. Educators who adopt neurodiversity principles in teaching practices contribute to societal change by valuing human diversity, potentially improving academic and social outcomes for all students.

Addressing the unique needs of neurodiverse students by creating accommodating environments can enhance the overall classroom experience. Both neurodiverse and neurotypical students benefit from exposure to diverse perspectives and teaching methods. This inclusive approach prepares students for real-world situations, where working alongside a diverse group is often required and valued.

Teachers can recognise neurodiversity through careful observation of learning patterns, social interactions, and sensory responses without waiting for formal diagnoses. Key indicators include different processing speeds, unique problem-solving approaches, and varied attention spans or focus preferences. Effective recognition focuses on identifying strengths and learning profiles rather than deficits.

Neurodivergence shows up in many forms, and recognising these profiles helps educators respond to the individual rather than rely on labels. By observing how different learners engage with tasks, communicate, and navigate their environments, teachers can adapt support to build on strengths and address challenges. Below are common neurodivergent profiles educators may encounter, along with tailored strategies to promote inclusion and growth.

1. Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC)

Students with ASC may prefer predictable routines, benefit from low-stimulus environments, and find abstract language or group dynamics challenging. Structured visuals, sensory rooms, and predictable transitions reduce anxiety. Lego therapy and sand tray therapy can support social interaction and emotional expression through play and storytelling.

2. Attention DeficitHyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

ADHD affects impulse control, focus, and working memory. Learners may need movement, novelty, and clear boundaries. Use trauma-informed sensory circuits, visual timers, and task chunking to support regulation and productivity. Seating near the teacher and flexible task completion options help maintain engagement.

3. Dyslexia

Dyslexia impacts reading and spelling but is often paired with creative thinking and oral storytelling strengths. Use multisensory phonics, coloured overlays, and audio tools to support literacy. Colourful semantics can also support sentence construction and comprehension through visual scaffolds.

4. Dyspraxia (DCD)

Students with dyspraxia may struggle with motor planning and coordination. Visual step-by-step guides, concrete task modelling, and breaking activities into manageable chunks can reduce overload. Allow alternative ways to record work (e.g. Voice notes or typing) and provide tools like pencil grips or sloped boards.

5. Dyscalculia

Learners with dyscalculia benefit from tangible, abstract-to-concrete learning approaches. Use number lines, counting cubes, and real-life contexts to build number sense. Consistent visual models and hands-on practice are key to developing confidence and fluency.

6. Dysgraphia

This profile affects handwriting and the organisation of written work. Offer speech-to-text tools, graphic organisers, and extra time for tasks. Incorporate multisensory pre-writing activities, and focus on reducing cognitive loadby separating planning and transcription stages.

7. Tourette Syndrome

Tics are involuntary and often exacerbated by stress. Maintain a calm, understanding tone and avoid drawing attention to them. Provide private breaks if needed and educate peers to creates acceptance. Offer quiet corners or sensory toolkits to help with self-regulation.

8. Sensory Processing Differences

These learners may be over- or under-responsive to stimuli. Introduce sensory rooms, flexible seating, and trauma-informed sensory circuits for grounding. Fidget tools, noise-cancelling headphones, and dimmable lights can make the classroom more accessible.

9. Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA)

PDA learners experience anxiety in response to demands. Avoid power struggles by using low-arousal communication, humour, and collaborative choices. Sand tray and play-based methods like Lego therapy can offer indirect but meaningful routes to learning.

By recognising and supporting neurodiverse learners through flexible, sensory-aware, and play-based strategies, educators create inclusive classrooms where every student can thrive, academically and socially and emotionally too.

Teachers need to shift from viewing neurodivergent traits as problems to fix toward celebrating them as natural variations that bring valuable perspectives. This involves moving beyond deficit-based thinking to strength-based approaches that recognise hidden talents and alternative ways of learning. The key change is seeing diversity as an advantage rather than a challenge to overcome.

In recent years, educational practices have embraced a shift towards recognising the uniqueness of every brain. This mindset change is crucial for creating classroom environments where all students, including neurodiverse students, can thrive. Instead of viewing accommodations as optional extras, they should be seen as beneficial for everyone. This encourages educators to view all students as capable learners with unique strengths and potential.

By developing an inclusive environment, schools can enhance inclusivity in education and promote a sense of belonging. Implementing systems for nonverbal assistance and alternatives to public speaking helps reduce anxiety. This promotes independence and adaptability, allowing neurodivergent learners to feel more comfortable and engaged. Embracing neurodiversity means moving beyond mere accommodations; it celebrates differences and improves educational experiences for all students.

Traditional compliance-based assessment methods can sometimes hinder the potential of neurodivergent students. These methods often focus too much on memorization and standardised tests. Moving beyond this approach means recognising the individuality of students and finding alternative assessment strategies. Portfolio assessments, project-based learning, and self-reflection give students the chance to demonstrate their knowledge in diverse ways.

This not only highlights their unique strengths but also provides a richer understanding of their abilities. In an inclusive education setting, neurodivergent and neurotypical students alike benefit from these varied assessment methods. They creates creativity, critical thinking, and self-confidence. Shifting the focus towards these methods not only aids neurodivergent people but enhances the classroom experience for all, creating a truly inclusive classroom environment.

Effective strategies include flexible instruction methods, multi-sensory learning approaches, and providing multiple ways for students to demonstrate knowledge. Visual aids, structured routines, and choice in learning activities help accommodate different processing styles and attention spans. These adaptations benefit all learners while specifically supporting neurodivergent students' success.

Transformative teaching strategies prioritise personalized learning, which emphasises the talents and problem-solving skills of neurodivergent individuals. These approaches cultivate a growth mindset, enhancing motivation and engagement for students with autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other neurological conditions. An inclusive classroom doesn't just support neurodivergent learners but enriches the learning process for everyone by promoting human diversity. Through these methods, educators creates a supportive environment that values every student's contributions.

Visual supports are essential tools in an inclusive learning environment. They aid neurodivergent learners in grasping and retaining concepts by illustrating information visually. Pictures, diagrams, and color-coding help make abstract ideas more tangible. These tools can improve comprehension by linking structured language with engaging visuals. Offering information in multiple formats, verbal, written, and visual, is vital for reinforcing learning for all students. This approach caters to different learning styles and enhances everyone's understanding. For neurodivergent students, using a graphic syllabus, as well as charts and graphs, can make complex ideas stick. Visual learning tools, like multimedia presentations, can engage students who might struggle with auditory information, ensuring that the learning environment is truly inclusive.

Flexible seating arrangements contribute to an inclusive classroom setting by addressing the sensory needs of neurodivergent students. Standing desks, exercise balls, and beanbags allow for gentle movement, which can be crucial for focus and comfort. Allowing students to choose between different seating options helps cater to diverse sensory needs, decreasing behavioral issues and enhancing engagement. Preferential seating enables neurodivergent students to sit where they can focus best, such as closer to the teacher or away from distractions. Employing universal design principles, including flexible seating, benefits all students. It caters to both diagnosed and undiagnosed needs, providing an environment that supports a wide range of learning preferences and needs.

Multi-modal teaching approaches enhance inclusivity in neurodiverse classrooms by integrating various learning techniques. These methods include visual, auditory, and kinesthetic approaches, providing alternatives to traditional learning. Incorporating different teaching methods can reduce anxiety for neurodivergent students, making learning more engaging. By offering nonverbal communication options and personalized learning supports, teachers can create a more predictable and stable learning environment. Multi-modal strategies help develop organisational skills and time management by tailoring tasks to individual learningstyles. By embracing these approaches, educators creates a classroom culture that not only accommodates but celebrates neurodiversity. This enriching environment benefits all students, acknowledging and embracing human diversity in education.

Create inclusive environments by establishing clear routines, reducing sensory overload, and offering quiet spaces for students who need breaks. Flexible seating options, visual schedules, and calm-down corners help accommodate different sensory and attention needs. Small environmental changes like adjusting lighting and minimising distractions can significantly impact all students' learning experiences.

An inclusive learning environment embraces the diversity of our student population. It recognises a natural range of variations in how people think and learn. This is essential for supporting neurodiverse students. Effective classroom strategies involve understanding these differences. Neurotypical and neurodivergent students may differ in how they process information and interact socially.

By focusing on the strengths and challenges each student has, we can create supportive spaces. Flexible management strategies, like positive reinforcement, help students thrive. In places like the UK, resources such as LEANS raise awareness about neurodiversity. They work to integrate this understanding into schools, helping all students appreciate individual differences.

Teachers play a crucial role in developing inclusive education. They should work with students, families, and colleagues to craft supportive environments. Recognizing diverse strengths is vital for students’ success. Professional learning offers teachers a chance to adapt and create accommodations suited for neurodivergent learners.

Collaborating in teams, with both general and special education teachers, can enhance learning through peer support. Teachers can benefit from including statements about accommodations in their syllabi. This practice emphasises accessibility and ensures neurodivergent students know the support available. By being adaptable and aware, teachers create classrooms where all students can excel.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) provides a comprehensive framework that offers multiple means of representation, engagement, and expression. The SAMR model helps integrate technology to support diverse learning needs and processing styles. These frameworks emphasise proactive planning that anticipates and accommodates learning differences from the start.

Educators play a crucial role in creating an inclusive classroom setting. A practical framework tailored to neurodiverse students can enhance their educational encounter. Educators can use manipulatives and interactive lessons, which help in understanding and retention for neurodivergent learners. Establishing predictable routines is essential for neurodivergent children, especially those with ADHD, as it helps them stay focused during the school day. Flexible seating arrangements and movement breaks are also vital. They assist in maintaining engagement and concentration. Incorporating universal design features and flexibility creates an inclusive environment. This approach supports neurodivergent people effectively. Building positive relationships with students and involving parents strengthens support systems for neurodivergent learners. Such practices ensure that neurodivergent students have a fulfiling opportunity in their education.

Developing personalized learning plans is key to meeting the unique needs of neurodiverse learners. These plans should consider each student's social cues and triggers to prevent distress. Tailored lesson plans ensure educational content accommodates various neurodivergent conditions. Educators should work closely with students, parents, and staff to create inclusive environments. This collaboration recognises each student's learning preferences and strengths. Adjusting curricula by modifying workloads can boost engagement and accessibility. Personalized instruction helps neurodivergent learners thrive. By adapting teaching strategies to align with wide-ranging learning styles, educators can develop effective plans. This approach enables students, including autistic students, to reach their full potential and enjoy a more enriching school experience.

Encouraging peer support systems in schools creates an inclusive atmosphere for neurodivergent students. Collaborative team teaching can be effective. It unites general and special education teachers to creates inclusive learning environments. Group work also encourages collaboration among students. These activities make learning meaningful and increase student engagement. Positive reinforcement is another tool that enhances peer support. Recognizing achievements boosts self-esteem and motivation among neurodiverse learners. This recognition enriches classroom dynamics, promoting supportive peer interactions. Teachers can further aid students by matching those with complementary skills. This method allows learners to benefit from each other's strengths. Such collaborations make classroom environments more inclusive and supportive, offering equal learning opportunities to all students.

Address resistance by sharing research on improved outcomes for all students when neurodiversity practices are implemented. Start with small, manageable changes that demonstrate clear benefits before introducing larger systemic shifts. Professional developmentand peer collaboration help build confidence and competence in inclusive teaching methods.

In the educational landscape, embracing neurodiversity involves a significant shift in understanding. This paradigm recognises neurological differences as natural and valuable. However, implementing this shift in schools presents challenges. Educators must overcome resistance and misconceptions that arise. Ensuring meaningful inclusion requires everyone, teachers, students, and staff, to appreciate diverse experiences. This approach reduces barriers like bullying and isolation. Additionally, effective collaboration among school staff is crucial. Co-teachers must build relationships based on respect and trust to address diverse learning needs. A neurodiversity-affirming classroom demands a gradual change in mindset. It involves valuing both the strengths and struggles of neurodiverse students. Creating such an environment is not immediate and requires shared commitment from educators.

Neurodiversity shifts the focus from seeing neurological differences as deficits to celebrating them as natural variations. This approach challenges traditional views, promoting a more inclusive understanding. The movement de-stigmatizes neurodivergence, developing acceptance and self-awareness. Recognizing neurodiversity as part of human diversity is crucial. It is akin to how society views ethnicity or gender, encouraging inclusive practices. Educators are key players in this transformation. By valuing the strengths of neurodivergent students, they counter stigma and prejudice. Such efforts are vital in developing an environment where all learners thrive.

Measure success through multiple indicators including student engagement levels, academic progress across different learning styles, and classroom climate surveys. Track both quantitative data like test scores and qualitative observations such as student confidence and participation rates. Regular feedback from students, parents, and colleagues provides comprehensive insight into program effectiveness.

Embracing neurodiversity in the classroom creates a positive environment for all students. It allows each student to use their unique strengths, making them feel valued and supported. Teachers and school staff must share a commitment to these practices for them to be effective. Recognizing both the strengths and challenges of neurodiverse students is crucial in promoting their academic success. By nurturing skills like creativity and problem-solving, students build self-confidence and feel they belong.

Neurodiverse students often face unique challenges that can affect their classroom engagement. Sensory overload and social skills difficulties may hinder their participation in class activities. Teachers can employ strategies like positive reinforcement to boost self-esteem. This increases motivation and improves engagement. Group activities that pair complementary skills, such as creative and analytical thinkers, can also enhance learning. Educators play a pivotal role in accommodating diverse learning styles. Their efforts, combined with those of students, parents, and staff, create supportive environments. This teamwork results in improved engagement and academic success for neurodiverse students.

Neurodivergent students may encounter social challenges that impact their long-term development. Teachers who develop strong bonds with these students creates an inclusive environment. Such support can encourage self-acceptance and improve relationships. Structured routines in class help students with ADHD focus better and enhance their academic performance. When schools collaborate with parents, they gain insights into a child's unique needs. This partnership bridges home and school, supporting student growth. Incorporating diverse learning materials also enriches comprehension and creates a love for learning. These practices contribute to the overall development of neurodiverse students, supporting them throughout their education.

Essential resources include research-based books on Universal Design for Learning, professional development courses on inclusive education, and guidance from special education specialists. Online communities and educational organisations provide current strategies and peer support for implementing neurodiversity practices. Academic journals and case studies offer evidence-based approaches for different classroom contexts.

The following studies show how increasing awareness, building inclusive curricula, and promoting peer understanding can help neurodivergent children better adapt and succeed in school settings.

1. Learning About Neurodiversity at School (LEANS Programme)

Alcorn et al. (2024) evaluated the LEANS classroom programme, designed to teach mainstream primary pupils about neurodiversity. The programme significantly improved children’s understanding of neurodiversity and increased positive attitudes and intentions toward neurodivergent peers. This study demonstrates how structured whole-class interventions can create more inclusive and supportive classroom cultures.

2. Promoting Social-Inclusion Through the 'In My Shoes' Programme

Littlefair et al. (2024) adapted the Australian "In My Shoes" intervention for UK primary schools to enhance participation and school connectedness for neurodivergent students. Stakeholder feedback supported linking the programme to the PSHE curriculum and emphasised its role in developing emotional and social development among children aged 8-10.

3. Neurodiversity and Inclusive Education Through Music Therapy

Moya-Pérez et al. (2024) conducted a systematic review showing that music therapy interventions in early childhood education promote emotional regulation, communication, and social integration for neurodivergent students. The review supports the use of therapeutic and pedagogical strategies to enhance classroom inclusion and academic success.

4. Neurodivergent Students in English Language Lessons

Ubaque-Casallas (2024) reflected on teacher education practices supporting neurodivergent learnersin English language classrooms. The study highlights the shift from instrumental lesson planning to a more humanizing, inclusive pedagogy that acknowledges autism as a unique neurocognitive perspective.

5. Adolescents Advocating for Neurodiversity Through Design Thinking

Schuck and Fung (2024) studied a summer camp where high school students used Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Design Thinking to create neurodiversity advocacy projects. Results showed reduced stigma, especially toward autism, and increased knowledge, empathy, and peer collaboration among participants.

Neurodiversity celebrates natural variations in how people think and process information, including conditions like autism, ADHD, and dyslexia. Rather than viewing these differences as deficits to be 'fixed', neurodiversity emphasises recognising and appreciating neurological differences as natural variations similar to ethnicity and gender.

Teachers can identify neurodiversity through careful observation of learning patterns, social interactions, and sensory responses in the classroom. Key indicators include different processing speeds, unique problem-solving approaches, varied attention spans, and distinctive ways students engage with tasks and navigate their environment.

Teachers can implement relaxation exercises, create calming classroom atmospheres, and manage cognitive load to reduce anxiety for neurodivergent students. These small changes, such as providing flexible teaching strategies and tailored support, actually improve learning outcomes for the entire class whilst developing an inclusive environment.

Neurotypical students benefit from exposure to diverse perspectives, varied problem-solving methods, and different teaching approaches when neurodiversity is embraced. This inclusive environment promotes creativity, innovation, and empathy throughout the entire classroom whilst preparing all students for real-world situations where working alongside diverse groups is valued.

Neurodivergent students frequently demonstrate exceptional creativity, unique problem-solving abilities, and effective thinking approaches that can enrich classroom discussions and activities. Recognising and nurturing these distinctive talents helps build their self-confidence and engagement whilst contributing meaningfully to the learning community.

Teachers can move away from trying to 'fix' neurodivergent students by instead focusing on identifying and building upon their unique strengths and learning profiles. This approach involves emphasising individual potential rather than limitations, creating supportive environments that allow each student's distinctive abilities to flourish and contribute to classroom dynamics.

Social scaffolding provides structured support during social activities, helping neurodivergent students navigate peer interactions and group work more successfully. This proactive approach reduces social isolation and promotes inclusion by creating frameworks that enable neurodivergent students to participate meaningfully in collaborative learning experiences.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into neurodiversity in the classroom and its application in educational settings.

Navigating the liminal space: Enhancing film teaching through anonymous feedback, digital collages, and advocacy

Cayir et al. (2024)

This paper examines how a Graduate Teaching Assistant used anonymous feedback, digital collages, and advocacy strategies to create more inclusive seminars that accommodate diverse student needs and learning difficulties. It provides practical insights for educators working in challenging teaching environments to creates belonging and inclusivity. Teachers will find valuable strategies for adapting their approaches to better support neurodivergent students in their classrooms.

Differentiated Instruction as a Viable Framework for Meeting the Needs of Diverse Adult Learners in Health Professions Education 3 citations

Colbert et al. (2023)

This paper explores how differentiated instruction can be used as a framework to meet the diverse learning needs of adult learners in health professions education. It demonstrates how tailoring teaching methods to accommodate different learning styles and abilities can improve educational outcomes. Teachers can apply these differentiated instruction principles to create more inclusive classrooms that support neurodivergent students alongside their neurotypical peers.

A multi-perspective study of Perceived Inclusive Education for students with Neurodevelopmental Disorders 11 citations

Leifler et al. (2022)

This study investigates the perspectives of autistic and neurodivergent students, their caregivers, and teachers regarding educational inclusion by examining seventeen student-caregiver-teacher triads. The research explores areas of consensus and disagreement about what constitutes effective inclusive education for neurodivergent students. Teachers will gain valuable insights into how different stakeholders view inclusion, helping them understand multiple perspectives when designing support strategies for neurodivergent learners.

Research exploring neurodivergent student experiences in higher education 14 citations (Author, Year) through an ecological systems theory perspective reveals important insights into how autism and ADHD students navigate access and inclusion challenges within university environments, highlighting the complex interplay between individual needs and institutional support systems.

Butcher et al. (2024)

This paper examines the experiences of neurodivergent students with autism and ADHD in higher education, identifying systemic barriers that create challenges for accessibility and inclusivity in learning environments. The study uses ecological systems theory to understand how various environmental factors impact neurodivergent students' educational experiences. Teachers can learn about the specific challenges neurodivergent students face and discover evidence-based accommodations and staff approaches that improve accessibility and inclusion.

This systematic review examining Universal Design for Learning in teacher education 11 citations (Author, Year) analyses how UDL principles are integrated into teacher preparation programmes and their effectiveness in developing inclusive pedagogical practices amongst pre-service educators.

Fuente-González et al. (2025)

This systematic review examines how Universal Design for Learning is being integrated into teacher education programs and its effectiveness in preparing educators to support all students. UDL is an educational approach that aims to improve learning for all students by providing multiple means of engagement, representation, and expression without requiring significant curriculum modifications. Teachers will understand how UDL principles can be applied in their practice to create naturally inclusive classrooms that benefit neurodivergent students and all learners.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/neurodiversity-in-the-classroom-a-teachers-guide#article","headline":"Neurodiversity in the classroom","description":"Discover practical strategies to support neurodiverse learners and create an inclusive, responsive classroom for every student.","datePublished":"2021-11-09T12:59:52.888Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/neurodiversity-in-the-classroom-a-teachers-guide"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69441b070fcf4d8cc5e65e9d_67ea70b2bf79e85a336dbc6e_Supporting%2520neurodiverse%2520learners.jpeg","wordCount":4231},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/neurodiversity-in-the-classroom-a-teachers-guide#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Neurodiversity in the classroom","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/neurodiversity-in-the-classroom-a-teachers-guide"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/neurodiversity-in-the-classroom-a-teachers-guide#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What exactly is neurodiversity and how does it differ from traditional views of learning differences?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Neurodiversity celebrates natural variations in how people think and process information, including conditions like autism, ADHD, and dyslexia. Rather than viewing these differences as deficits to be 'fixed', neurodiversity emphasises recognising and appreciating neurological differences as natural "}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers recognise neurodivergent students without formal diagnoses or labels?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can identify neurodiversity through careful observation of learning patterns, social interactions, and sensory responses in the classroom. Key indicators include different processing speeds, unique problem-solving approaches, varied attention spans, and distinctive ways students engage with"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What specific classroom adjustments can teachers make to support both neurodivergent and neurotypical learners?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can implement relaxation exercises, create calming classroom atmospheres, and manage cognitive load to reduce anxiety for neurodivergent students. These small changes, such as providing flexible teaching strategies and tailored support, actually improve learning outcomes for the entire clas"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How does embracing neurodiversity benefit neurotypical students, not just those who are neurodivergent?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Neurotypical students benefit from exposure to diverse perspectives, varied problem-solving methods, and different teaching approaches when neurodiversity is embraced. This inclusive environment promotes creativity, innovation, and empathy throughout the entire classroom whilst preparing all student"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the key strengths that neurodivergent students often bring to the classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Neurodivergent students frequently demonstrate exceptional creativity, unique problem-solving abilities, and innovative thinking approaches that can enrich classroom discussions and activities. Recognising and nurturing these distinctive talents helps build their self-confidence and engagement whils"}}]}]}