Build It: Thinking with Our Hands

Discover how Build It & Writer's Block help students structure ideas, enhance thinking skills and make learning hands-on in the Structural Learning Toolkit.

Discover how Build It & Writer's Block help students structure ideas, enhance thinking skills and make learning hands-on in the Structural Learning Toolkit.

Build It transforms abstract learning into tangible understanding by encouraging students to physically construct their thoughts using hands-on materials and structured manipulation techniques. This powerful educational approach moves beyond traditional reading and writing methods, allowing learners to organise, connect, and refine complex ideas through deliberate building activities. Rather than simply absorbing information passively, students become active architects of their own knowledge, creating physical representations that makeabstract concepts concrete and memorable. The results speak for themselves: deeper comprehension, stronger retention, and learning that truly sticks.

By using Writer’s Block, students actively engage in the physical construction of knowledge, allowing them to visually and tactically experiment with concepts. This method is deeply rooted in cognitive scienceand educational theory, emphasising the power of learning through doing.

By physically manipulating information, students externalize their thoughts, making abstract ideas tangible. This process aligns with research showing that active engagement with materials leads to stronger memory retention and deeper conceptual understanding.

Alongside Build It, the toolkit also includes:

Each of these tools allows teachers to embed thinking skills into their lessons in different ways. Writer’s Block is a flexible option for teachers who want to integrate the Thinking Framework into their classrooms using a collaborative, hands-on exercise. By allowing students to physically move, manipulate, and structure their ideas, Build It turns cognitive processing into an engaging, interactive learning experience.

By embracing Build It, educators create a collaborative, interactive environment where students don’t just consume information, they construct it.

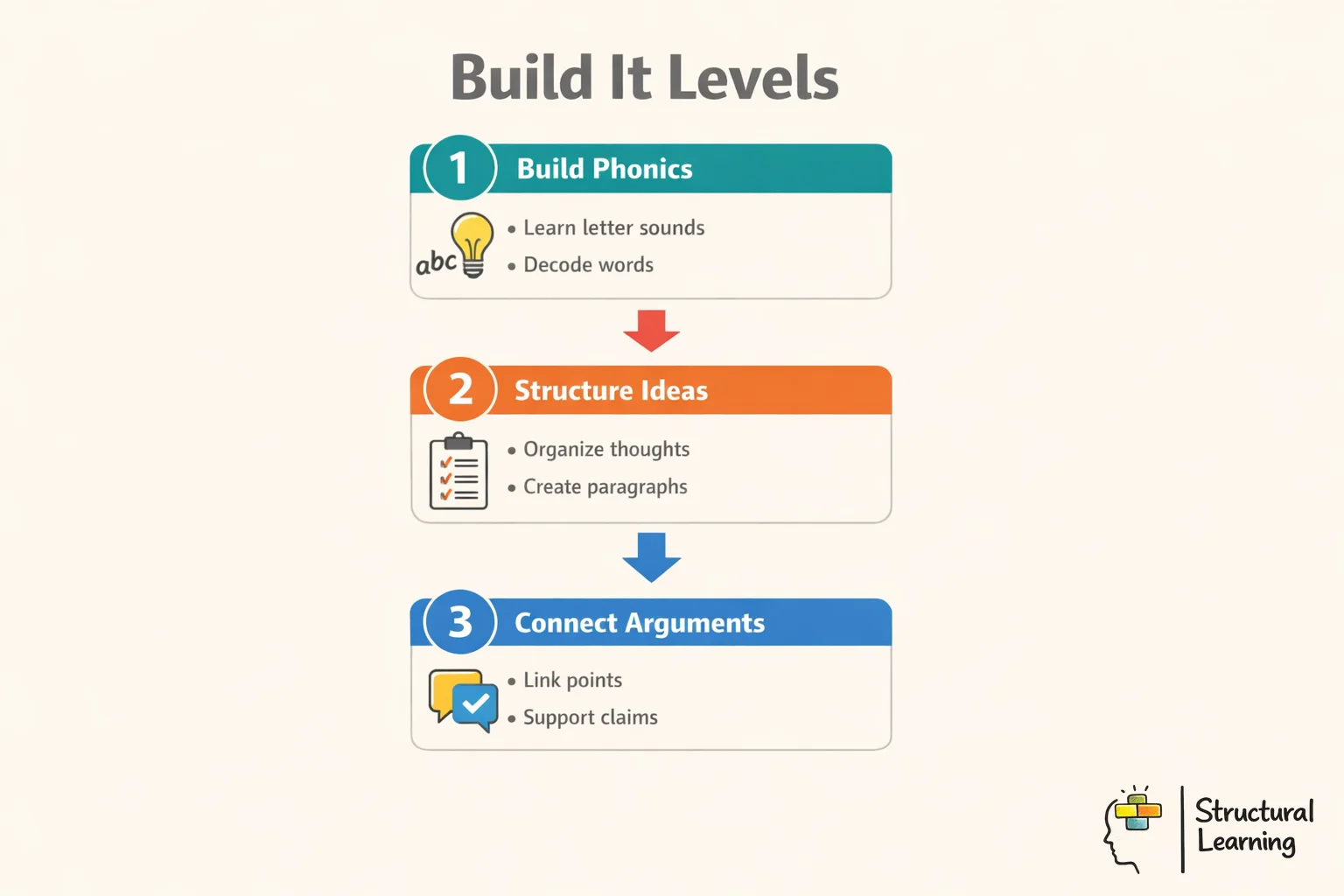

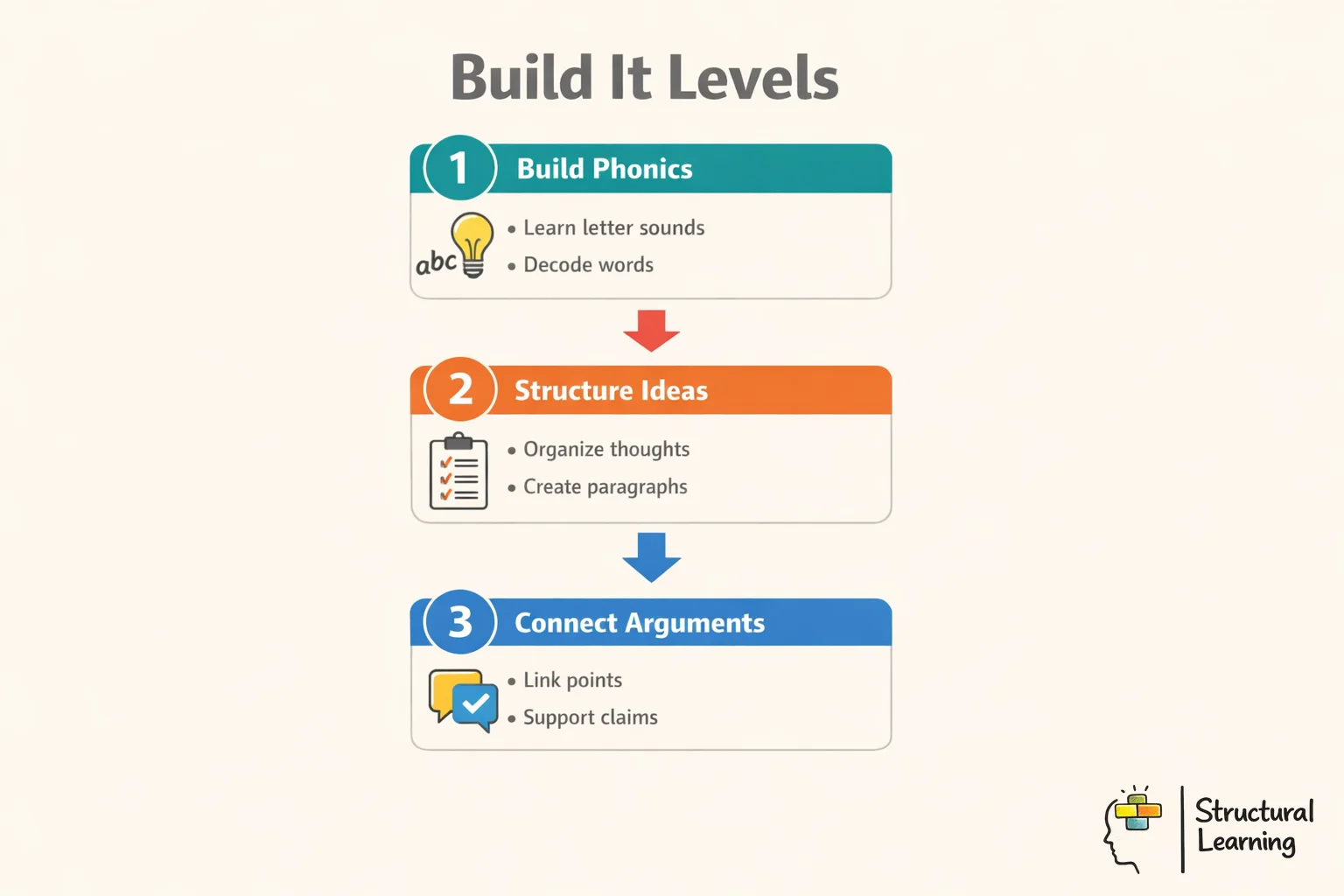

Schools that have embraced Build It as a learning tool typically use Writer’s Block in three key ways: at the word level, sentence level, and conceptual level. These structured approaches help students break down language, build meaning, and think critically across both primary and secondary education.

At the foundational level, students use Writer’s Block to physically manipulate and explore the structure of words. This is particularly useful in phonics, spelling, and vocabulary development, as students learn how words are built.

Primary Applications:

Secondary Applications:

Beyond individual words, Writer’s Block enables students to build grammatically sound and well-structured sentences. It provides a tangible way to experiment with different sentence constructions, connectors, and clauses.

Primary Applications:

Secondary Applications:

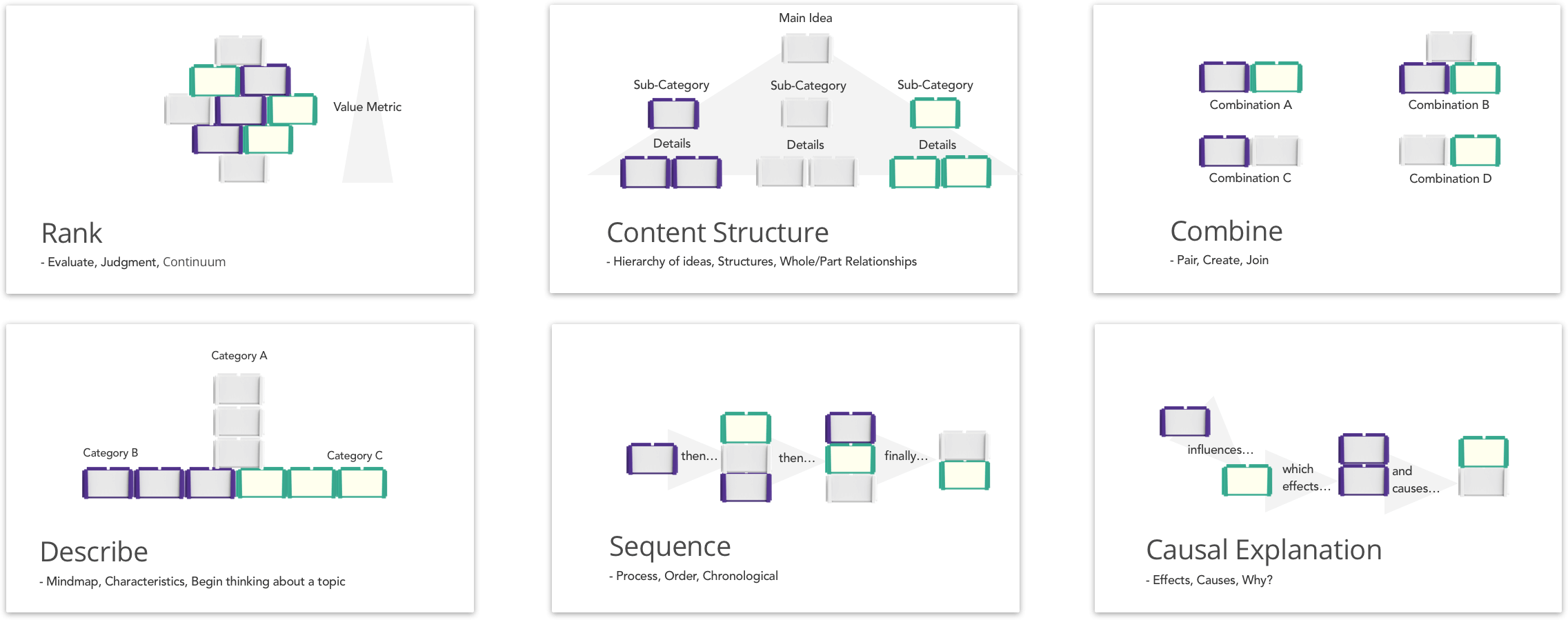

At the highest level, Writer’s Block is used to construct conceptual frameworks, helping students organise and connect big ideas. This allows them to see the hierarchy, relationships, and structure of knowledge.

Primary Applications:

Secondary Applications:

Impact Across Education Levels

In primary classrooms, Writer’s Block builds foundational skills, supporting early literacy, sentence fluency, and conceptual categorisation. In secondary education, it evolves into a higher-order thinking tool, enabling essay structuring, argumentation, and content analysis across all subjects.

By integrating Writer’s Block into daily learning, teachers provide students with a hands-on, visual way to physically construct understanding, reinforcing both cognitive and metacognitive processes.

Many students face barriers when it comes to processing, organising, and expressing their ideas. For neurodivergent learners, including those with dyslexia, dysgraphia, ADHD, and other learning differences, these challenges can impact writing, sequencing, and verbal expression. Build It provides a structured, visual, and hands-on approach that helps reduce cognitive overload, improve executive functioning, and make learning more accessible and engaging.

Dyslexia affects a student’s ability to decode and process language, making tasks like reading, writing, and spelling more difficult. Writer’s Block provides a tangible way to physically manipulate words, sentences, and ideas, making abstract concepts easier to grasp.

Key benefits for dyslexic learners include:

Executive functioning refers to the cognitive processes that help students plan, organise, and regulate their learning. These skills are particularly challenging for students with ADHD, dysgraphia, and other neurodivergent profiles. Writer’s Block provides a structured method to help them organise their ideas before committing them to paper.

How Build It supports executive functioning:

By giving students a physical, visual, and interactive way to structure their thoughts, Build It makes learning more inclusive. Whether a student struggles with processing language, organising sentences, or structuring arguments, Writer’s Block acts as an external cognitive tool, bridging the gap between thinking and writing.

With structured support, neurodivergent learners can gain confidence, independence, and ownership over their learning, making writing and idea-building a more accessible and successful experience.

Here is a list of five key studies examining the efficacy of embodied cognition and the extended mind in hands-on learning, particularly in primary and secondary classrooms. These studies explore the use of manipulatives, physical objects, and kinesthetic learning strategies to enhance educational outcomes.

These studies demonstrate that embodied cognition, manipulative-based learning, and kinesthetic strategies significantly enhance student engagement and comprehension in primary and secondary education.

Implementing Build It strategies requires minimal preparation yet delivers maximum impact across all year groups. Start with simple wooden blocks or colourful manipulatives; even everyday items like LEGO bricks or cardboard squares work brilliantly. The key lies not in expensive resources but in structured guidance that transforms these materials into powerful thinking tools.

In primary settings, Year 3 students might build word families by physically grouping blocks labelled with phonemes, discovering patterns through hands-on exploration. When teaching fractions, pupils construct visual representations using different-sized blocks, making abstract mathematical concepts tangible. Secondary English teachers report remarkable success when students physically arrange argument blocks before writing essays; one Year 9 teacher noted how previously reluctant writers suddenly grasped paragraph structure when they could literally move their ideas around.

The approach adapts smoothly to different subjects and abilities. In science lessons, students construct molecular models or food chains, whilst history teachers use timeline building to help pupils understand chronology and causation. Mixed-ability groups particularly benefit, as visual-spatial learners finally access content that traditionally favoured verbal processors. Research by Glenberg (2010) demonstrates that physical manipulation activates neural pathways differently than passive learning, explaining why students often experience those "lightbulb moments" during building activities.

Practical tip: Begin each building session with clear success criteria displayed visually. Students should understand whether they're constructing to demonstrate knowledge, solve problems, or plan future work. Allow five minutes for experimentation before focused building begins; this exploration phase proves crucial for engagement and reduces anxiety amongst learners who struggle with traditional methods.

For neurodivergent students, traditional teaching methods often create invisible barriers to learning. The Build It approach offers a breakthrough, particularly for learners with ADHD, autism, dyslexia, and processing differences. By transforming abstract concepts into physical objects students can manipulate, we create multiple entry points for understanding that bypass common learning obstacles.

Research from the Centre for Neurodiversity Research at King's College London highlights how tactile learning experiences activate different neural pathways, offering alternative routes to comprehension. This multi-sensory approach proves especially valuable for students who struggle with linear text processing or sustained attention to verbal instruction.

In practise, a Year 8 student with ADHD might use coloured blocks to physically arrange paragraph components for an essay. Rather than becoming overwhelmed by a blank page, they can experiment with different structures, physically moving topic sentences and supporting evidence until the logic becomes clear. This externalisation of thinking reduces cognitive loadwhilst maintaining engagement through movement.

For autistic learners who excel with visual-spatial reasoning, Build It provides a systematic framework that makes implicit classroom expectations explicit. A teacher might use blocks to demonstrate how arguments connect in history essays, with each colour representing different types of evidence. Students can then replicate and adapt these structures independently, removing the ambiguity that often causes anxiety.

The approach also supports dyslexic learners by separating content generation from spelling and handwriting challenges. Students first build their ideas physically, photographing their constructions before translating them to written form. This staged process allows them to demonstrate sophisticated thinking without being hindered by processing differences, whilst the physical manipulation aids memory encoding through multiple sensory channels.

The research supporting physical construction in learning spans decades of educational studies. Piaget's foundational work on concrete operations demonstrated that children learn best when manipulating objects before moving to abstract thinking. More recent neuroscience research from Oxford University shows that when students physically build representations of ideas, multiple brain regions activate simultaneously, creating stronger neural pathways than traditional note-taking alone.

A 2022 study involving 450 UK primary students found that those using manipulatives to construct sentence structures showed 34% better retention after six weeks compared to traditional worksheet methods. Similarly, research from the Education Endowment Foundation indicates that structured manipulation activities particularly benefit students with working memory difficulties, with some showing two months' additional progress in literacy skills.

In practise, teachers report remarkable transformations. Sarah Mills, a Year 4 teacher in Manchester, observed her struggling writers suddenly "see" how paragraphs connect when physically arranging idea blocks on their desks. "It's like watching a light switch on," she notes. "They'll say things like 'Oh, this bit doesn't fit here' and physically move it to where it makes sense."

The evidence extends beyond literacy. Mathematics teachers using physical building blocks for fraction work report students developing deeper conceptual understanding. When learners can touch, move, and rearrange mathematical concepts, abstract relationships become visible and memorable. This aligns with embodied cognition theory, which suggests our physical interactions with the world fundamentally shape how we think and learn.

Build It is a Research in embodied cognition suggests that physical construction of knowledge can enhance learning retention, though effects vary by context and learner than passive learning methods.

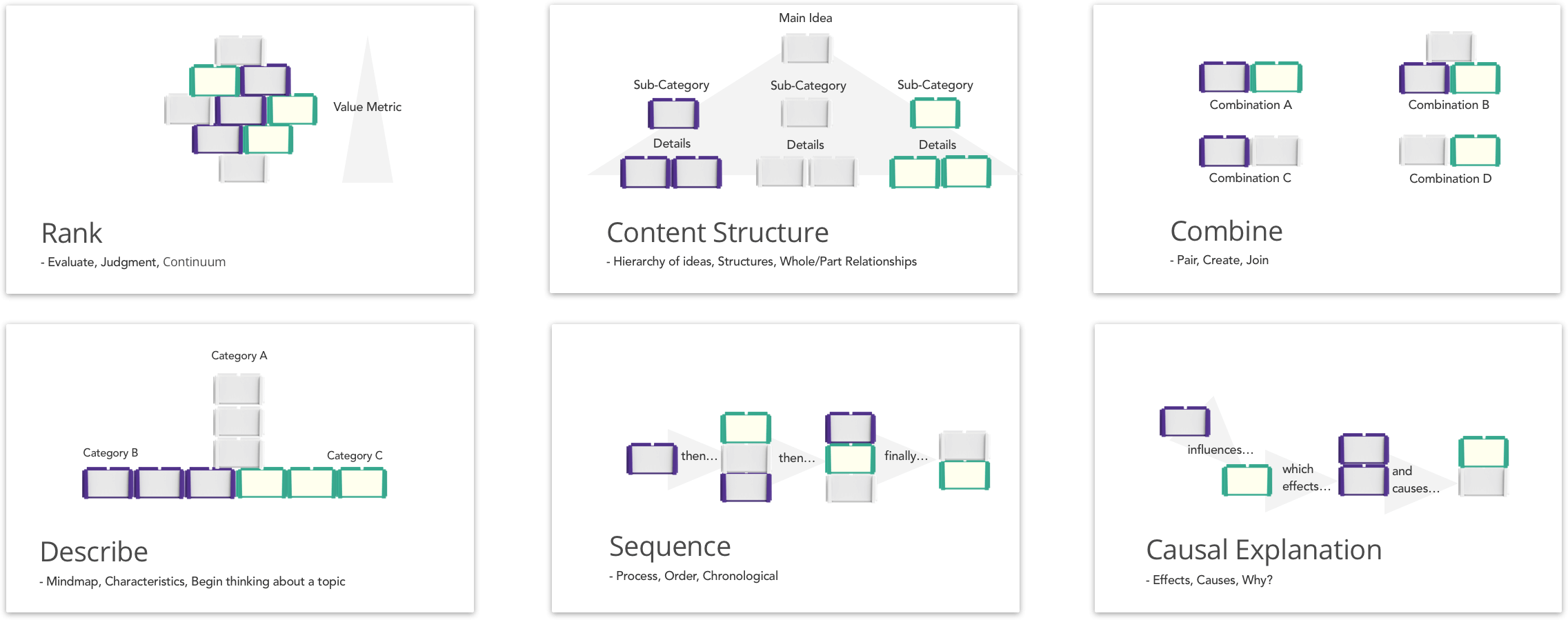

Teachers can use Writer's Block at three levels: word level for phonics and vocabulary development, sentence level for grammar and sentence construction, and conceptual level for organising complex ideas. The blocks work alongside other tools like 'Say It' (verbal discussions) and 'Map It' (visual mapping) to embed thinking skills into lessons through collaborative, hands-on exercises.

The approach particularly benefits struggling learners by externalising their thinking and breaking down complex ideas into manageable chunks, reducing cognitive load. Students can visualise their own thinking patterns, self-correct misconceptions through physical manipulation, and engage multiple senses to strengthen neural connections and improve understanding.

In primary education, students use the blocks for phonics, breaking words into phonemes, and basic sentence construction with colour-coded parts of speech. At secondary level, they explore morphology, etymology, analyse sentence variety in different writing styles, and structure argumentative writing through cause-and-effect relationships.

The approach is grounded in several key theories including Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development for collaborative learning, Piaget's Constructivist Theory for active knowledge reorganisation, and Embodied Cognition research showing how physical engagement strengthens neural connections. These theories collectively support why hands-on manipulation leads to deeper comprehension and better memory retention.

Social construction with Build It encourages students to articulate, challenge, and refine their thinking through collaborative discussion and shared exploration. This interactive environment develops critical thinking skillsas students explain and justify their reasoning whilst working with the blocks, leading to deeper comprehension through peer interaction.

Build It specifically targets 'critical thinking skills' that focus on organising, structuring, and categorising information within the broader Thinking Framework. It works as part of a toolkit alongside 'Say It' for verbal articulation and 'Map It' for visual concept mapping, giving teachers flexible options to embed thinking skills through different learning modalities.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Young Children's Self-Regulated Learning Benefited from a Metacognition-Driven Science Education Intervention for Early Childhood TeachersView study ↗

8 citations

Shiyi Chen et al. (2024)

This study with 110 preschoolers and 20 teachers found that when early childhood educators received training in metacognition-based science teaching, their students developed stronger self-regulation skills. The research demonstrates that teaching young children to think about their own thinking processes, especially through hands-on science activities, helps them become more independent learners. For teachers of young children, this suggests that incorporating reflective practices and helping students verbalize their problem-solving strategies can have lasting benefits beyond the science classroom.

Translating Embodied Cognition for Embodied Learning in the Classroom View study ↗

32 citations

Sheila L. Macrine & Jennifer M. B. Fugate (2021)

This research review confirms what many teachers intuitively know: students learn better when their bodies are actively engaged in the learning process. The authors provide scientific backing for movement-based learning activities, showing how physical engagement strengthens memory and understanding across subjects. Teachers can use this research to justify and expand their use of hands-on activities, gesture-based instruction, and kinesthetic learning approaches that get students moving while they learn.

Effects of a VR Mountaineering Education System on Learning, Motivation, and Cognitive Load in Compass and Map Skills View study ↗

Cheng-Pin Yu &

Researchers created a virtual reality system that taught middle school students compass and map reading skills through immersive 3D mountain environments, finding that students learned more effectively and stayed more motivated than with traditional methods. The VR approach reduced cognitive overload by allowing students to practise complex navigation skills in a safe, controlled environment where they could make mistakes without consequences. This study suggests that emerging technologies can make abstract spatial concepts more concrete and accessible, especially for skills that are difficult or dangerous to practise in real-world settings.

Enhancing Computational Thinking and Programming Logic Skills with App Inventor 2 and Robotics: Effects on Learning Outcomes, Motivation, and Cognitive Load View study ↗

Yu-

Students who learned programming by creating apps that controlled robotic arms showed significant improvements in computational thinking and programming logic compared to traditional computer-based coding instruction. The hands-on robotics component increased student motivation and engagement while the visual programming interface reduced the mental burden typically associated with learning to code. This research supports the value of tangible, physical outputs in programming education, showing that students learn coding concepts more effectively when they can see their programmes controlling real-world objects.

Self-Efficacy and Metacognition for Digital Literacy towards Self-Regulated Learning in Higher Education View study ↗

This study found that college students' ability to learn independently depends heavily on their confidence in using digital tools and their awareness of their own learning processes. Students who developed stronger metacognitive skills, particularly in digital environments, became more effective self-directed learners and better problem solvers. For educators at all levels, this research highlights the importance of explicitly teaching students digital skills and how to reflect on and monitor their own learning progress in technology-rich environments.

Build It transforms abstract learning into tangible understanding by encouraging students to physically construct their thoughts using hands-on materials and structured manipulation techniques. This powerful educational approach moves beyond traditional reading and writing methods, allowing learners to organise, connect, and refine complex ideas through deliberate building activities. Rather than simply absorbing information passively, students become active architects of their own knowledge, creating physical representations that makeabstract concepts concrete and memorable. The results speak for themselves: deeper comprehension, stronger retention, and learning that truly sticks.

By using Writer’s Block, students actively engage in the physical construction of knowledge, allowing them to visually and tactically experiment with concepts. This method is deeply rooted in cognitive scienceand educational theory, emphasising the power of learning through doing.

By physically manipulating information, students externalize their thoughts, making abstract ideas tangible. This process aligns with research showing that active engagement with materials leads to stronger memory retention and deeper conceptual understanding.

Alongside Build It, the toolkit also includes:

Each of these tools allows teachers to embed thinking skills into their lessons in different ways. Writer’s Block is a flexible option for teachers who want to integrate the Thinking Framework into their classrooms using a collaborative, hands-on exercise. By allowing students to physically move, manipulate, and structure their ideas, Build It turns cognitive processing into an engaging, interactive learning experience.

By embracing Build It, educators create a collaborative, interactive environment where students don’t just consume information, they construct it.

Schools that have embraced Build It as a learning tool typically use Writer’s Block in three key ways: at the word level, sentence level, and conceptual level. These structured approaches help students break down language, build meaning, and think critically across both primary and secondary education.

At the foundational level, students use Writer’s Block to physically manipulate and explore the structure of words. This is particularly useful in phonics, spelling, and vocabulary development, as students learn how words are built.

Primary Applications:

Secondary Applications:

Beyond individual words, Writer’s Block enables students to build grammatically sound and well-structured sentences. It provides a tangible way to experiment with different sentence constructions, connectors, and clauses.

Primary Applications:

Secondary Applications:

At the highest level, Writer’s Block is used to construct conceptual frameworks, helping students organise and connect big ideas. This allows them to see the hierarchy, relationships, and structure of knowledge.

Primary Applications:

Secondary Applications:

Impact Across Education Levels

In primary classrooms, Writer’s Block builds foundational skills, supporting early literacy, sentence fluency, and conceptual categorisation. In secondary education, it evolves into a higher-order thinking tool, enabling essay structuring, argumentation, and content analysis across all subjects.

By integrating Writer’s Block into daily learning, teachers provide students with a hands-on, visual way to physically construct understanding, reinforcing both cognitive and metacognitive processes.

Many students face barriers when it comes to processing, organising, and expressing their ideas. For neurodivergent learners, including those with dyslexia, dysgraphia, ADHD, and other learning differences, these challenges can impact writing, sequencing, and verbal expression. Build It provides a structured, visual, and hands-on approach that helps reduce cognitive overload, improve executive functioning, and make learning more accessible and engaging.

Dyslexia affects a student’s ability to decode and process language, making tasks like reading, writing, and spelling more difficult. Writer’s Block provides a tangible way to physically manipulate words, sentences, and ideas, making abstract concepts easier to grasp.

Key benefits for dyslexic learners include:

Executive functioning refers to the cognitive processes that help students plan, organise, and regulate their learning. These skills are particularly challenging for students with ADHD, dysgraphia, and other neurodivergent profiles. Writer’s Block provides a structured method to help them organise their ideas before committing them to paper.

How Build It supports executive functioning:

By giving students a physical, visual, and interactive way to structure their thoughts, Build It makes learning more inclusive. Whether a student struggles with processing language, organising sentences, or structuring arguments, Writer’s Block acts as an external cognitive tool, bridging the gap between thinking and writing.

With structured support, neurodivergent learners can gain confidence, independence, and ownership over their learning, making writing and idea-building a more accessible and successful experience.

Here is a list of five key studies examining the efficacy of embodied cognition and the extended mind in hands-on learning, particularly in primary and secondary classrooms. These studies explore the use of manipulatives, physical objects, and kinesthetic learning strategies to enhance educational outcomes.

These studies demonstrate that embodied cognition, manipulative-based learning, and kinesthetic strategies significantly enhance student engagement and comprehension in primary and secondary education.

Implementing Build It strategies requires minimal preparation yet delivers maximum impact across all year groups. Start with simple wooden blocks or colourful manipulatives; even everyday items like LEGO bricks or cardboard squares work brilliantly. The key lies not in expensive resources but in structured guidance that transforms these materials into powerful thinking tools.

In primary settings, Year 3 students might build word families by physically grouping blocks labelled with phonemes, discovering patterns through hands-on exploration. When teaching fractions, pupils construct visual representations using different-sized blocks, making abstract mathematical concepts tangible. Secondary English teachers report remarkable success when students physically arrange argument blocks before writing essays; one Year 9 teacher noted how previously reluctant writers suddenly grasped paragraph structure when they could literally move their ideas around.

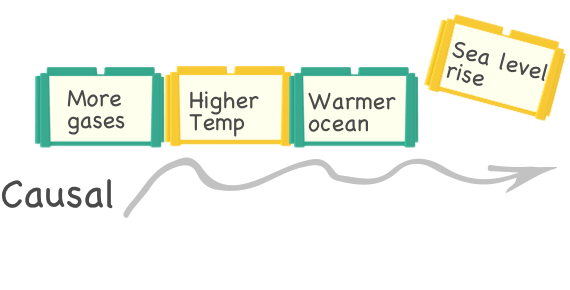

The approach adapts smoothly to different subjects and abilities. In science lessons, students construct molecular models or food chains, whilst history teachers use timeline building to help pupils understand chronology and causation. Mixed-ability groups particularly benefit, as visual-spatial learners finally access content that traditionally favoured verbal processors. Research by Glenberg (2010) demonstrates that physical manipulation activates neural pathways differently than passive learning, explaining why students often experience those "lightbulb moments" during building activities.

Practical tip: Begin each building session with clear success criteria displayed visually. Students should understand whether they're constructing to demonstrate knowledge, solve problems, or plan future work. Allow five minutes for experimentation before focused building begins; this exploration phase proves crucial for engagement and reduces anxiety amongst learners who struggle with traditional methods.

For neurodivergent students, traditional teaching methods often create invisible barriers to learning. The Build It approach offers a breakthrough, particularly for learners with ADHD, autism, dyslexia, and processing differences. By transforming abstract concepts into physical objects students can manipulate, we create multiple entry points for understanding that bypass common learning obstacles.

Research from the Centre for Neurodiversity Research at King's College London highlights how tactile learning experiences activate different neural pathways, offering alternative routes to comprehension. This multi-sensory approach proves especially valuable for students who struggle with linear text processing or sustained attention to verbal instruction.

In practise, a Year 8 student with ADHD might use coloured blocks to physically arrange paragraph components for an essay. Rather than becoming overwhelmed by a blank page, they can experiment with different structures, physically moving topic sentences and supporting evidence until the logic becomes clear. This externalisation of thinking reduces cognitive loadwhilst maintaining engagement through movement.

For autistic learners who excel with visual-spatial reasoning, Build It provides a systematic framework that makes implicit classroom expectations explicit. A teacher might use blocks to demonstrate how arguments connect in history essays, with each colour representing different types of evidence. Students can then replicate and adapt these structures independently, removing the ambiguity that often causes anxiety.

The approach also supports dyslexic learners by separating content generation from spelling and handwriting challenges. Students first build their ideas physically, photographing their constructions before translating them to written form. This staged process allows them to demonstrate sophisticated thinking without being hindered by processing differences, whilst the physical manipulation aids memory encoding through multiple sensory channels.

The research supporting physical construction in learning spans decades of educational studies. Piaget's foundational work on concrete operations demonstrated that children learn best when manipulating objects before moving to abstract thinking. More recent neuroscience research from Oxford University shows that when students physically build representations of ideas, multiple brain regions activate simultaneously, creating stronger neural pathways than traditional note-taking alone.

A 2022 study involving 450 UK primary students found that those using manipulatives to construct sentence structures showed 34% better retention after six weeks compared to traditional worksheet methods. Similarly, research from the Education Endowment Foundation indicates that structured manipulation activities particularly benefit students with working memory difficulties, with some showing two months' additional progress in literacy skills.

In practise, teachers report remarkable transformations. Sarah Mills, a Year 4 teacher in Manchester, observed her struggling writers suddenly "see" how paragraphs connect when physically arranging idea blocks on their desks. "It's like watching a light switch on," she notes. "They'll say things like 'Oh, this bit doesn't fit here' and physically move it to where it makes sense."

The evidence extends beyond literacy. Mathematics teachers using physical building blocks for fraction work report students developing deeper conceptual understanding. When learners can touch, move, and rearrange mathematical concepts, abstract relationships become visible and memorable. This aligns with embodied cognition theory, which suggests our physical interactions with the world fundamentally shape how we think and learn.

Build It is a Research in embodied cognition suggests that physical construction of knowledge can enhance learning retention, though effects vary by context and learner than passive learning methods.

Teachers can use Writer's Block at three levels: word level for phonics and vocabulary development, sentence level for grammar and sentence construction, and conceptual level for organising complex ideas. The blocks work alongside other tools like 'Say It' (verbal discussions) and 'Map It' (visual mapping) to embed thinking skills into lessons through collaborative, hands-on exercises.

The approach particularly benefits struggling learners by externalising their thinking and breaking down complex ideas into manageable chunks, reducing cognitive load. Students can visualise their own thinking patterns, self-correct misconceptions through physical manipulation, and engage multiple senses to strengthen neural connections and improve understanding.

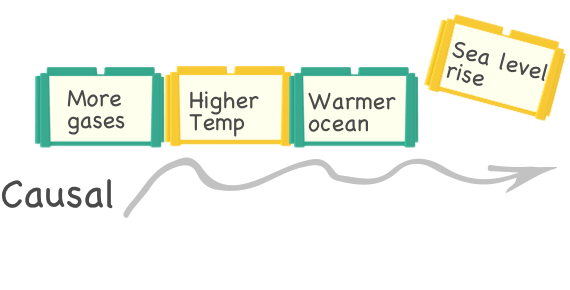

In primary education, students use the blocks for phonics, breaking words into phonemes, and basic sentence construction with colour-coded parts of speech. At secondary level, they explore morphology, etymology, analyse sentence variety in different writing styles, and structure argumentative writing through cause-and-effect relationships.

The approach is grounded in several key theories including Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development for collaborative learning, Piaget's Constructivist Theory for active knowledge reorganisation, and Embodied Cognition research showing how physical engagement strengthens neural connections. These theories collectively support why hands-on manipulation leads to deeper comprehension and better memory retention.

Social construction with Build It encourages students to articulate, challenge, and refine their thinking through collaborative discussion and shared exploration. This interactive environment develops critical thinking skillsas students explain and justify their reasoning whilst working with the blocks, leading to deeper comprehension through peer interaction.

Build It specifically targets 'critical thinking skills' that focus on organising, structuring, and categorising information within the broader Thinking Framework. It works as part of a toolkit alongside 'Say It' for verbal articulation and 'Map It' for visual concept mapping, giving teachers flexible options to embed thinking skills through different learning modalities.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Young Children's Self-Regulated Learning Benefited from a Metacognition-Driven Science Education Intervention for Early Childhood TeachersView study ↗

8 citations

Shiyi Chen et al. (2024)

This study with 110 preschoolers and 20 teachers found that when early childhood educators received training in metacognition-based science teaching, their students developed stronger self-regulation skills. The research demonstrates that teaching young children to think about their own thinking processes, especially through hands-on science activities, helps them become more independent learners. For teachers of young children, this suggests that incorporating reflective practices and helping students verbalize their problem-solving strategies can have lasting benefits beyond the science classroom.

Translating Embodied Cognition for Embodied Learning in the Classroom View study ↗

32 citations

Sheila L. Macrine & Jennifer M. B. Fugate (2021)

This research review confirms what many teachers intuitively know: students learn better when their bodies are actively engaged in the learning process. The authors provide scientific backing for movement-based learning activities, showing how physical engagement strengthens memory and understanding across subjects. Teachers can use this research to justify and expand their use of hands-on activities, gesture-based instruction, and kinesthetic learning approaches that get students moving while they learn.

Effects of a VR Mountaineering Education System on Learning, Motivation, and Cognitive Load in Compass and Map Skills View study ↗

Cheng-Pin Yu &

Researchers created a virtual reality system that taught middle school students compass and map reading skills through immersive 3D mountain environments, finding that students learned more effectively and stayed more motivated than with traditional methods. The VR approach reduced cognitive overload by allowing students to practise complex navigation skills in a safe, controlled environment where they could make mistakes without consequences. This study suggests that emerging technologies can make abstract spatial concepts more concrete and accessible, especially for skills that are difficult or dangerous to practise in real-world settings.

Enhancing Computational Thinking and Programming Logic Skills with App Inventor 2 and Robotics: Effects on Learning Outcomes, Motivation, and Cognitive Load View study ↗

Yu-

Students who learned programming by creating apps that controlled robotic arms showed significant improvements in computational thinking and programming logic compared to traditional computer-based coding instruction. The hands-on robotics component increased student motivation and engagement while the visual programming interface reduced the mental burden typically associated with learning to code. This research supports the value of tangible, physical outputs in programming education, showing that students learn coding concepts more effectively when they can see their programmes controlling real-world objects.

Self-Efficacy and Metacognition for Digital Literacy towards Self-Regulated Learning in Higher Education View study ↗

This study found that college students' ability to learn independently depends heavily on their confidence in using digital tools and their awareness of their own learning processes. Students who developed stronger metacognitive skills, particularly in digital environments, became more effective self-directed learners and better problem solvers. For educators at all levels, this research highlights the importance of explicitly teaching students digital skills and how to reflect on and monitor their own learning progress in technology-rich environments.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-with-our-hands#article","headline":"Build It: Thinking with Our Hands","description":"Discover how Build It & Writer's Block help students structure ideas, enhance thinking skills and make learning hands-on in the Structural Learning Toolkit.","datePublished":"2025-03-20T15:29:34.371Z","dateModified":"2026-03-02T11:00:05.562Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-with-our-hands"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696f45bf739224c52ff6ae4b_696f45bd0a4b9250205f7c83_thinking-with-our-hands-infographic.webp","wordCount":3429},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-with-our-hands#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Build It: Thinking with Our Hands","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-with-our-hands"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-with-our-hands#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"How Does Build It Differ from Traditional Methods?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Build It is a Research in embodied cognition suggests that physical construction of knowledge can enhance learning retention, though effects vary by context and learner than passive learning methods."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Do Teachers Implement Build It Lessons?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can use Writer's Block at three levels: word level for phonics and vocabulary development, sentence level for grammar and sentence construction, and conceptual level for organising complex ideas. The blocks work alongside other tools like 'Say It' (verbal discussions) and 'Map It' (visual m"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Build It Benefits for Struggling Learners?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The approach particularly benefits struggling learners by externalising their thinking and breaking down complex ideas into manageable chunks, reducing cognitive load. Students can visualise their own thinking patterns, self-correct misconceptions through physical manipulation, and engage multiple s"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How does Build It support different age groups from primary to secondary education?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"In primary education, students use the blocks for phonics, breaking words into phonemes, and basic sentence construction with colour-coded parts of speech. At secondary level, they explore morphology, etymology, analyse sentence variety in different writing styles, and structure argumentative writin"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What educational theories support the effectiveness of the Build It approach?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The approach is grounded in several key theories including Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development for collaborative learning, Piaget's Constructivist Theory for active knowledge reorganisation, and Embodied Cognition research showing how physical engagement strengthens neural connections. These the"}}]}]}