Special Educational Needs

Discover how to support pupils with Special Educational Needs through inclusive teaching strategies that unlock potential and remove learning barriers.

Every child in the world has strengths and weaknesses, and each child will prosper under different conditions. Understanding neurodiversity helps us recognise that these differences are natural variations in human development. There is a lot of debate about special education needs students. Are these children incapable of learning as well as their mainstream peers and can specialised educational provision and high-quality teaching really remove the progress barriers they face? We shall discuss specific educational needs in full in this article and hopefully provide an overall big picture of this complex domain.

When a child has an additional learning difficulty or disability, which creates additional barriers to learning based on their age range. This is referred to as Special Education Needs (SEN). Some children may have trouble coping with their regular school day activities, such as finishing their schoolwork, communicating with others, or acting improperly due to social emotional mental health issues or conditions like ADHD or dyspraxia, which may require specialised assessments such as dyspraxia testing. Many autistic learners also face these challengesand dyslexia and they may require education health care plans plans to meet their needs.

Special Educational Needs with examples and icons" loading="lazy">

Special Educational Needs with examples and icons" loading="lazy">In this article, we will discuss what inclusive education means and how every classroom can make learning accessible. We will explore strategies for creating inclusive classrooms that support all learners, including autistic learners. We will begin the article by outlining the wide range of additional learning needs. Being able to provide suitable SEN provision requires us to have a good conceptual understanding of the sheer breadth of access needs. The class teacher, along with the SENDCo, often have to dig a bit deeper to get to the underlying issue the child is facing. The classroom behaviours don't always tell us the true picture and that's why involve specialists from the outset.

The most common types of SEN include specific learning difficulties like dyslexia and dyscalculia, communication and interaction needs such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), social emotional and mental health difficulties including ADHD, and sensory or physical needs like hearing or visual impairments. Many children experience overlapping conditions across these categories rather than fitting neatly into one area. Understanding the full range of a child's needs, rather than focusing on a single label, is essential for providing effective support.

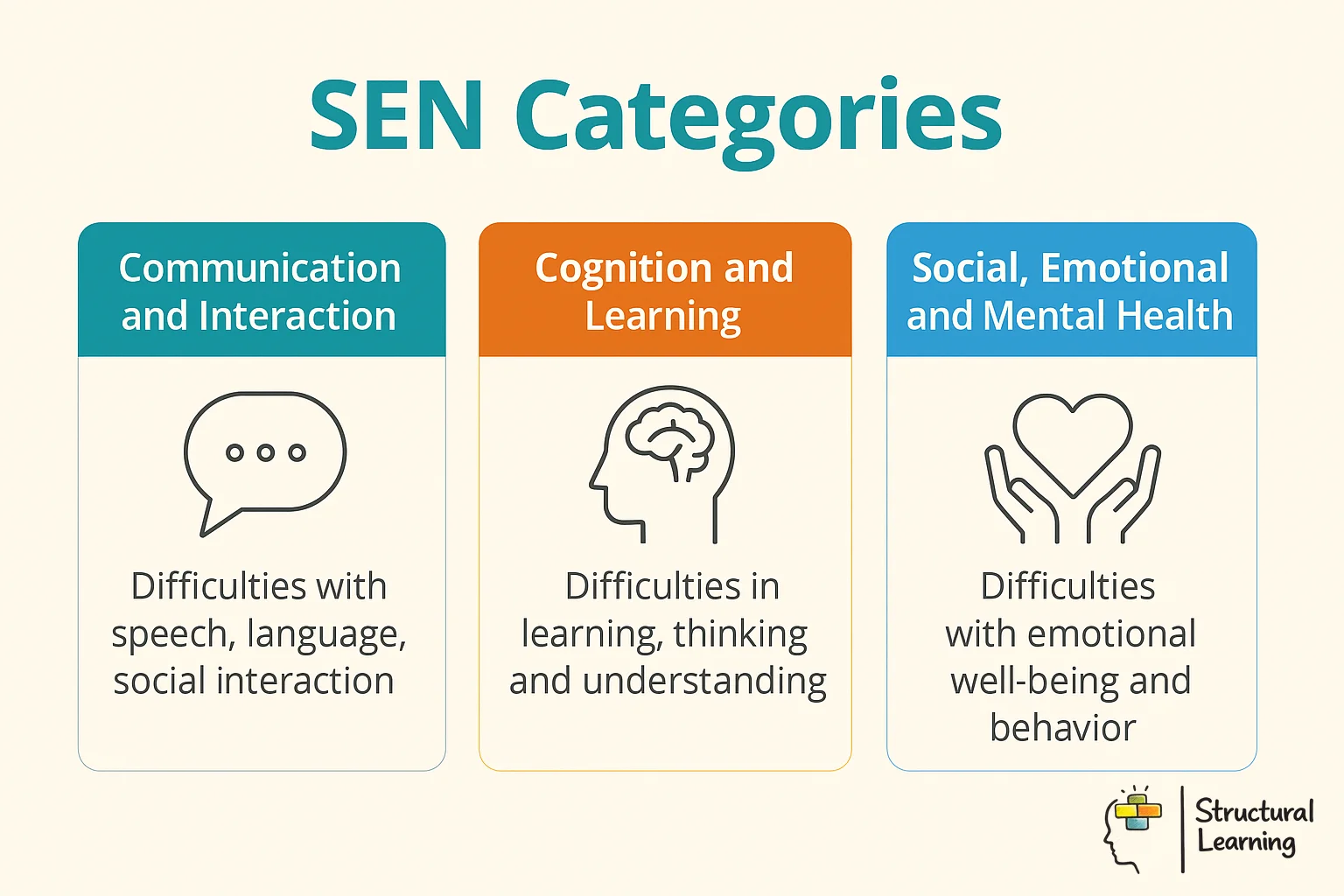

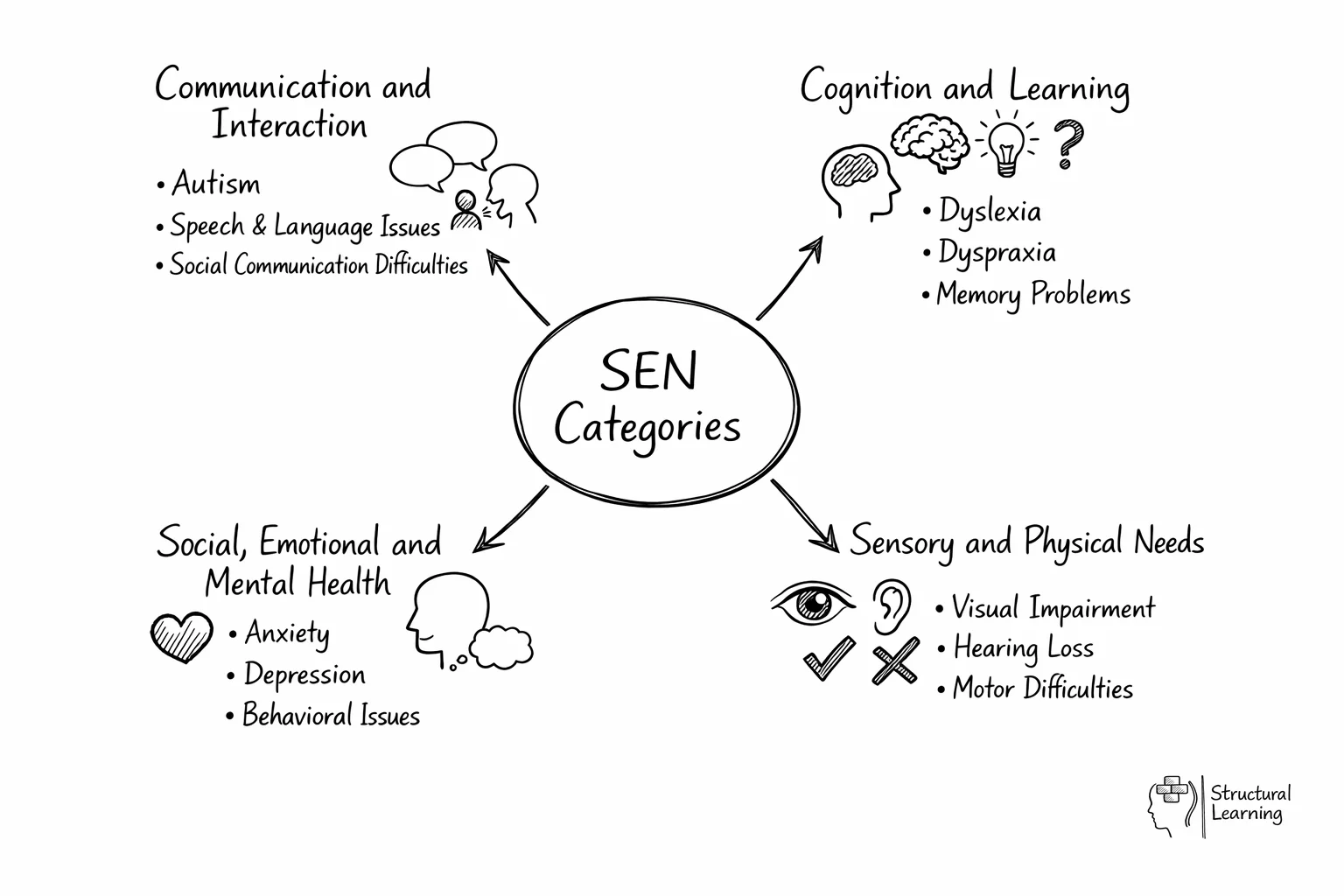

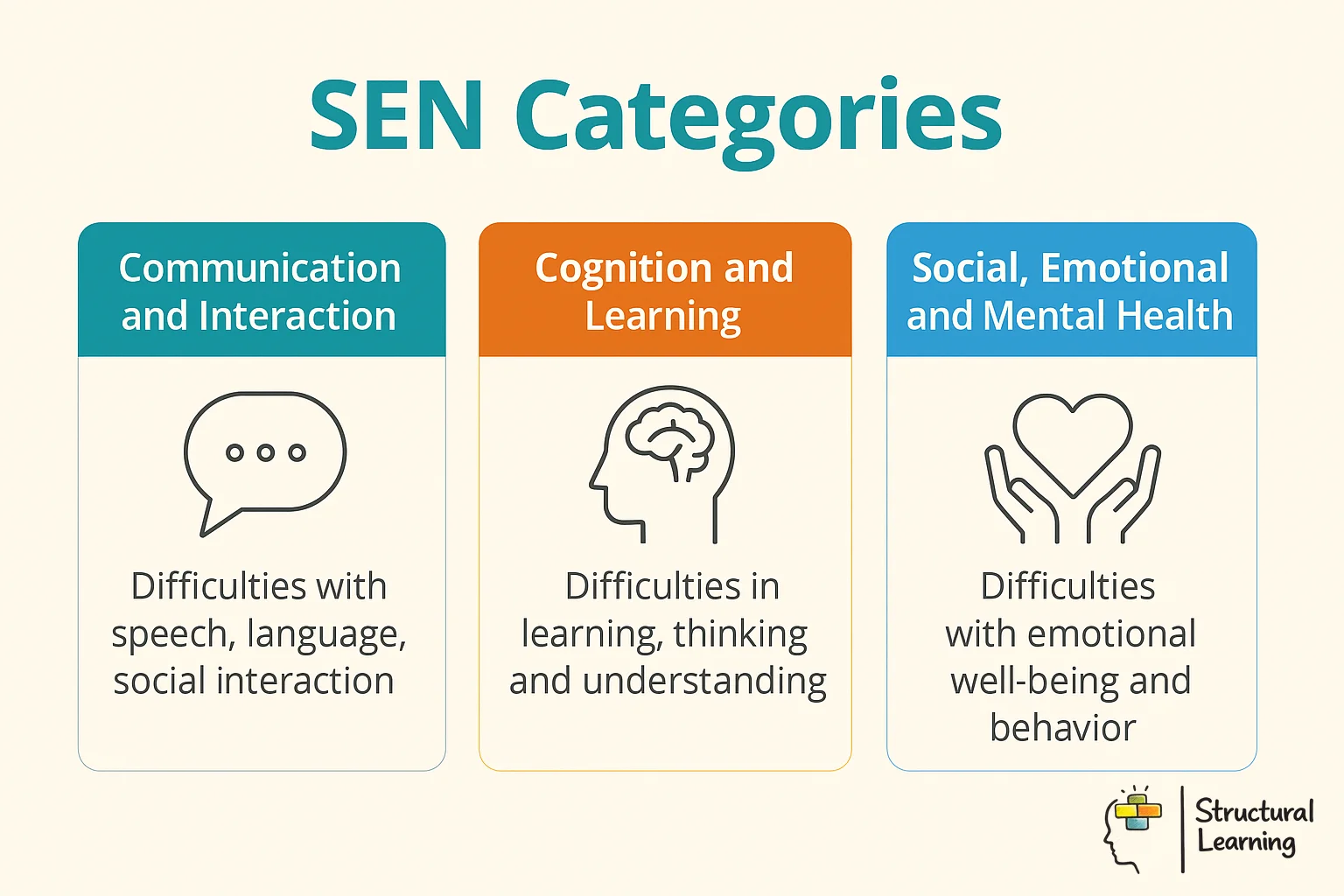

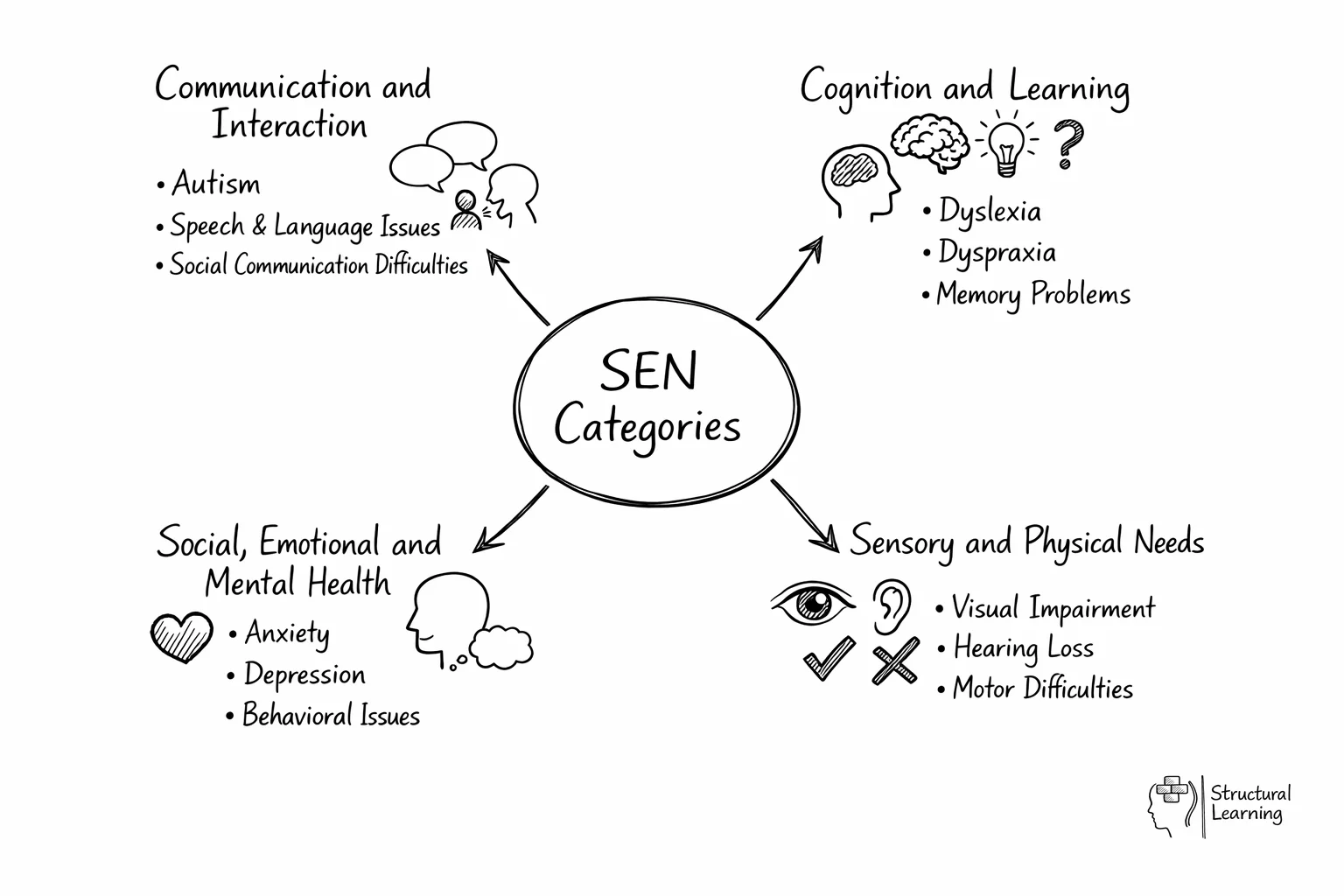

A person with SEN may fall into at least one of these four groups, according to the Children and Families Act (DfE, 2014a):

1. Communication and Interaction: problems interacting with, reacting to, and understanding spoken language, such as speech problems or autism.

2. Cognition and Learning needs: It is primarily a problem with the taught curriculum, such as dyslexia (reading and spelling), dyscalculia (mathematics), dyspraxia (coordination), or dysgraphia (writing). Which may requires different types of scaffolding such as one-to-one support or group support.

3. Social, mental, and emotional health: attention deficit disorder (ADD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or autism, for example, cause problems in managing and expressing emotions and behavioural difficulties. These students may struggle with attention and require additional support with self-regulation.

4. Sensory and/or Physical Needs: physical and sensory difficulties such as visual impairment (VI), hearing impairment (HI), multi-sensory impairment (MSI), or physical disability.

Additionally, some children who are regarded as 'gifted and talented' may require SEN additional SEN support to suit their needs. Effective teaching approaches, including the use of graphic organisers and regular feedback, can help maintain engagement for all learners. Special education needs include not justengagement. Special education needs include not just those who require additional support but also those who may benefit from advanced learning opportunities and tailored teaching methodologies.

Teachers can support pupils with SEN by implementing inclusive teaching strategies and creating a supportive learning environment. Some useful teaching strategies for use with students with SEN may include:

These strategies are designed to address the unique needs of pupils with SEN, enabling them to participate fully in the classroom and achieve their full potential. Regular monitoring and assessment are crucial to ensure that interventions are effective and adjustments can be made as needed.

Creating an inclusive classroom environment requires careful consideration of physical space and learning resources. Arrange seating to minimise distractions whilst ensuring all students can access teaching materials and interact with peers. Consider using visual timetables, clear labelling systems, and designated quiet spaces where students can retreat when feeling overwhelmed. Establish consistent routines and give advance notice of any changes, as predictability helps many SEN students feel secure and ready to learn.

Building strong relationships with parents and carers is crucial for effective SEN support. Regular communication through home-school diaries, informal conversations, or structured meetings ensures everyone understands the child's current needs and progress. Parents often have valuable insights about strategies that work at home, whilst teachers can share successful classroom approaches for use in other settings. This collaborative partnership creates a unified support network that reinforces learning and development across all environments where the child spends time.

Identifying special educational needs requires a systematic approach that combines classroom observation, assessment data, and collaborative professional judgement. Teachers are often the first to notice when a pupil is struggling to make expected progress despite receiving quality first teaching and targeted interventions. This identification process should focus on understanding the barriers to learning rather than simply labelling difficulties, ensuring that any assessment leads directly to appropriate educational provision.

The graduated approach, as outlined in the SEN Code of Practice, provides a clear framework for assessment through the cycle of 'Assess, Plan, Do, Review'. During the assessment phase, teachers should gather evidence from multiple sources including standardised assessments, work samples, parental input, and the pupil's own voice. Collaboration with the school's Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCo) is essential, as they can provide expertise in interpreting assessment data and coordinating additional specialist assessments when needed.

In the classroom, effective identification relies on ongoing formative assessment rather than waiting for formal testing. Teachers should document patterns of difficulty, note which teaching strategies are most effective for individual pupils, and maintain clear records of interventions and their outcomes. This evidence-based approach ensures that any special educational provision is tailored to meet genuine individual needs and can be regularly reviewed for effectiveness.

The Children and Families Act 2014 fundamentally transformed how schools approach special educational needs, establishing clear statutory duties that every educator must understand. This legislation, supported by the SEN Code of Practice, places the child's needs at the centre of all decision-making whilst emphasising the importance of parental involvement and multi-agency collaboration. Schools are legally required to use their best endeavours to ensure pupils with SEN receive appropriate educational provision, making every teacher responsible for identifying and supporting individual needs within their classroom.

The statutory framework introduces a graduated approach to SEN support, moving from universal Quality First Teaching through targeted interventions to specialist provision where necessary. Research by Norwich and Lewis demonstrates that this tiered model maximises inclusive opportunities whilst ensuring intensive support reaches those who need it most. Schools must maintain detailed records of interventions, regularly review progress, and involve parents as equal partners in planning. The legislation also strengthens transition planning, requiring schools to prepare pupils for adulthood from Year 9 onwards.

In practice, these legal obligations translate into daily classroom responsibilities that support genuinely inclusive education. Teachers must differentiate instruction as standard practice, maintain ongoing assessment of pupil progress, and collaborate effectively with SENCOs when concerns arise. Understanding these legal frameworks helps educators to advocate confidently for their pupils whilst ensuring compliance with statutory requirements.

Building meaningful partnerships with parents and carers forms the cornerstone of effective special educational needs provision. Research by Epstein and Sheldon consistently demonstrates that when families are genuinely involved in their child's education, outcomes improve significantly across academic, social, and behavioural domains. For children with SEN, this collaboration becomes even more critical, as parents possess invaluable insights into their child's strengths, challenges, and successful strategies used at home.

Effective communication must be regular, honest, and solution-focused rather than limited to crisis management. Establish structured opportunities for dialogue through termly review meetings, informal check-ins, and shared communication books or digital platforms. When discussing concerns, frame conversations around the child's progress and next steps, acknowledging parental expertise whilst sharing your professional observations. This approach builds trust and ensures that educational provision remains responsive to the child's evolving needs.

Practical strategies include creating visual progress summaries that parents can easily understand, offering flexible meeting times to accommodate work schedules, and providing clear explanations of interventions being used in school. Encourage parents to share successful home strategies and consider how these might be adapted for the classroom environment. Remember that some families may feel overwhelmed by educational jargon, so prioritise clear, accessible language that focuses on their child's individual journey rather than deficit-based terminology.

Creating effective Individual Education Plans (IEPs) begins with comprehensive assessment and collaborative planning involving teachers, parents, and relevant specialists. The most successful IEPs focus on specific, measurable outcomes rather than broad aspirations, establishing clear targets that can be monitored and adjusted throughout the academic year. Research by Zigmond and Kloo demonstrates that well-structured individual planning significantly improves educational outcomes when goals are directly linked to classroom learning and daily activities.

Implementation requires systematic tracking and regular review cycles, typically every six to eight weeks, to ensure provisions remain relevant and challenging. Teachers should establish consistent monitoring systems that capture both academic progress and social development, recognising that special educational needs often encompass multiple areas of learning. The most effective approach involves breaking down annual targets into manageable short-term objectives that can be integrated smoothly into everyday lesson planning and differentiated instruction.

Successful IEP implementation relies on clear communication channels between all stakeholders and flexible adaptation of teaching strategies based on ongoing assessment data. Consider establishing weekly check-ins with teaching assistants and monthly discussions with parents to maintain momentum and address emerging challenges promptly. Remember that quality individual planning is an evolving process, not a static document, requiring continuous refinement to meet each pupil's changing needs and circumstances.

The physical classroom environment serves as the foundation for inclusive learning, directly impacting how effectively pupils with special educational needs can access the curriculum. Research by Karen Mapp emphasises that environmental factors significantly influence student engagement and academic outcomes, particularly for learners with sensory processing differences or attention difficulties. Creating an accessible space requires careful consideration of lighting, acoustics, seating arrangements, and visual displays to minimise distractions whilst maximising learning opportunities.

Sensory considerations are paramount when designing inclusive classrooms. Fluorescent lighting can cause distress for pupils with autism or visual processing disorders, making natural light or softer alternatives preferable. Similarly, excessive wall displays may overwhelm students with ADHD or sensory sensitivities, suggesting that strategic use of visual aids is more effective than cluttered environments. Acoustic modifications, such as carpet areas or sound-absorbing materials, can significantly benefit pupils with hearing impairments or auditory processing difficulties.

Practical accessibility extends beyond sensory adjustments to include flexible furniture arrangements and clear pathways for pupils with mobility needs. Designated quiet spaces allow learners to self-regulate when overwhelmed, whilst varied seating options accommodate different physical and concentration requirements. Regular environmental audits, ideally conducted with input from pupils themselves, ensure that classroom modifications continue to meet evolving individual needs effectively.

Supporting pupils with Special Educational Needs is a multifaceted endeavour that requires a deep understanding of individual needs, effective teaching strategies, and collaborative partnerships. By moving beyond labels and embracing a complete approach, educators can create inclusive classrooms where all pupils feel valued, supported, and helped to succeed. High-quality teaching, coupled with targeted interventions and appropriate accommodations, can remove barriers to learning and unlock the potential of every pupil, regardless of their challenges.

Ultimately, the goal is to creates a learning environment that celebrates neurodiversity and promotes equity for all. By investing in training, resources, and support systems, schools can create a culture of inclusion where pupils with SEN thrive academically, socially, and emotionally, and are well-prepared for future success. This commitment not only benefits individual pupils but also enriches the entire school community, developing empathy, understanding, and a shared sense of belonging.

Every child in the world has strengths and weaknesses, and each child will prosper under different conditions. Understanding neurodiversity helps us recognise that these differences are natural variations in human development. There is a lot of debate about special education needs students. Are these children incapable of learning as well as their mainstream peers and can specialised educational provision and high-quality teaching really remove the progress barriers they face? We shall discuss specific educational needs in full in this article and hopefully provide an overall big picture of this complex domain.

When a child has an additional learning difficulty or disability, which creates additional barriers to learning based on their age range. This is referred to as Special Education Needs (SEN). Some children may have trouble coping with their regular school day activities, such as finishing their schoolwork, communicating with others, or acting improperly due to social emotional mental health issues or conditions like ADHD or dyspraxia, which may require specialised assessments such as dyspraxia testing. Many autistic learners also face these challengesand dyslexia and they may require education health care plans plans to meet their needs.

Special Educational Needs with examples and icons" loading="lazy">

Special Educational Needs with examples and icons" loading="lazy">In this article, we will discuss what inclusive education means and how every classroom can make learning accessible. We will explore strategies for creating inclusive classrooms that support all learners, including autistic learners. We will begin the article by outlining the wide range of additional learning needs. Being able to provide suitable SEN provision requires us to have a good conceptual understanding of the sheer breadth of access needs. The class teacher, along with the SENDCo, often have to dig a bit deeper to get to the underlying issue the child is facing. The classroom behaviours don't always tell us the true picture and that's why involve specialists from the outset.

The most common types of SEN include specific learning difficulties like dyslexia and dyscalculia, communication and interaction needs such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), social emotional and mental health difficulties including ADHD, and sensory or physical needs like hearing or visual impairments. Many children experience overlapping conditions across these categories rather than fitting neatly into one area. Understanding the full range of a child's needs, rather than focusing on a single label, is essential for providing effective support.

A person with SEN may fall into at least one of these four groups, according to the Children and Families Act (DfE, 2014a):

1. Communication and Interaction: problems interacting with, reacting to, and understanding spoken language, such as speech problems or autism.

2. Cognition and Learning needs: It is primarily a problem with the taught curriculum, such as dyslexia (reading and spelling), dyscalculia (mathematics), dyspraxia (coordination), or dysgraphia (writing). Which may requires different types of scaffolding such as one-to-one support or group support.

3. Social, mental, and emotional health: attention deficit disorder (ADD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or autism, for example, cause problems in managing and expressing emotions and behavioural difficulties. These students may struggle with attention and require additional support with self-regulation.

4. Sensory and/or Physical Needs: physical and sensory difficulties such as visual impairment (VI), hearing impairment (HI), multi-sensory impairment (MSI), or physical disability.

Additionally, some children who are regarded as 'gifted and talented' may require SEN additional SEN support to suit their needs. Effective teaching approaches, including the use of graphic organisers and regular feedback, can help maintain engagement for all learners. Special education needs include not justengagement. Special education needs include not just those who require additional support but also those who may benefit from advanced learning opportunities and tailored teaching methodologies.

Teachers can support pupils with SEN by implementing inclusive teaching strategies and creating a supportive learning environment. Some useful teaching strategies for use with students with SEN may include:

These strategies are designed to address the unique needs of pupils with SEN, enabling them to participate fully in the classroom and achieve their full potential. Regular monitoring and assessment are crucial to ensure that interventions are effective and adjustments can be made as needed.

Creating an inclusive classroom environment requires careful consideration of physical space and learning resources. Arrange seating to minimise distractions whilst ensuring all students can access teaching materials and interact with peers. Consider using visual timetables, clear labelling systems, and designated quiet spaces where students can retreat when feeling overwhelmed. Establish consistent routines and give advance notice of any changes, as predictability helps many SEN students feel secure and ready to learn.

Building strong relationships with parents and carers is crucial for effective SEN support. Regular communication through home-school diaries, informal conversations, or structured meetings ensures everyone understands the child's current needs and progress. Parents often have valuable insights about strategies that work at home, whilst teachers can share successful classroom approaches for use in other settings. This collaborative partnership creates a unified support network that reinforces learning and development across all environments where the child spends time.

Identifying special educational needs requires a systematic approach that combines classroom observation, assessment data, and collaborative professional judgement. Teachers are often the first to notice when a pupil is struggling to make expected progress despite receiving quality first teaching and targeted interventions. This identification process should focus on understanding the barriers to learning rather than simply labelling difficulties, ensuring that any assessment leads directly to appropriate educational provision.

The graduated approach, as outlined in the SEN Code of Practice, provides a clear framework for assessment through the cycle of 'Assess, Plan, Do, Review'. During the assessment phase, teachers should gather evidence from multiple sources including standardised assessments, work samples, parental input, and the pupil's own voice. Collaboration with the school's Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCo) is essential, as they can provide expertise in interpreting assessment data and coordinating additional specialist assessments when needed.

In the classroom, effective identification relies on ongoing formative assessment rather than waiting for formal testing. Teachers should document patterns of difficulty, note which teaching strategies are most effective for individual pupils, and maintain clear records of interventions and their outcomes. This evidence-based approach ensures that any special educational provision is tailored to meet genuine individual needs and can be regularly reviewed for effectiveness.

The Children and Families Act 2014 fundamentally transformed how schools approach special educational needs, establishing clear statutory duties that every educator must understand. This legislation, supported by the SEN Code of Practice, places the child's needs at the centre of all decision-making whilst emphasising the importance of parental involvement and multi-agency collaboration. Schools are legally required to use their best endeavours to ensure pupils with SEN receive appropriate educational provision, making every teacher responsible for identifying and supporting individual needs within their classroom.

The statutory framework introduces a graduated approach to SEN support, moving from universal Quality First Teaching through targeted interventions to specialist provision where necessary. Research by Norwich and Lewis demonstrates that this tiered model maximises inclusive opportunities whilst ensuring intensive support reaches those who need it most. Schools must maintain detailed records of interventions, regularly review progress, and involve parents as equal partners in planning. The legislation also strengthens transition planning, requiring schools to prepare pupils for adulthood from Year 9 onwards.

In practice, these legal obligations translate into daily classroom responsibilities that support genuinely inclusive education. Teachers must differentiate instruction as standard practice, maintain ongoing assessment of pupil progress, and collaborate effectively with SENCOs when concerns arise. Understanding these legal frameworks helps educators to advocate confidently for their pupils whilst ensuring compliance with statutory requirements.

Building meaningful partnerships with parents and carers forms the cornerstone of effective special educational needs provision. Research by Epstein and Sheldon consistently demonstrates that when families are genuinely involved in their child's education, outcomes improve significantly across academic, social, and behavioural domains. For children with SEN, this collaboration becomes even more critical, as parents possess invaluable insights into their child's strengths, challenges, and successful strategies used at home.

Effective communication must be regular, honest, and solution-focused rather than limited to crisis management. Establish structured opportunities for dialogue through termly review meetings, informal check-ins, and shared communication books or digital platforms. When discussing concerns, frame conversations around the child's progress and next steps, acknowledging parental expertise whilst sharing your professional observations. This approach builds trust and ensures that educational provision remains responsive to the child's evolving needs.

Practical strategies include creating visual progress summaries that parents can easily understand, offering flexible meeting times to accommodate work schedules, and providing clear explanations of interventions being used in school. Encourage parents to share successful home strategies and consider how these might be adapted for the classroom environment. Remember that some families may feel overwhelmed by educational jargon, so prioritise clear, accessible language that focuses on their child's individual journey rather than deficit-based terminology.

Creating effective Individual Education Plans (IEPs) begins with comprehensive assessment and collaborative planning involving teachers, parents, and relevant specialists. The most successful IEPs focus on specific, measurable outcomes rather than broad aspirations, establishing clear targets that can be monitored and adjusted throughout the academic year. Research by Zigmond and Kloo demonstrates that well-structured individual planning significantly improves educational outcomes when goals are directly linked to classroom learning and daily activities.

Implementation requires systematic tracking and regular review cycles, typically every six to eight weeks, to ensure provisions remain relevant and challenging. Teachers should establish consistent monitoring systems that capture both academic progress and social development, recognising that special educational needs often encompass multiple areas of learning. The most effective approach involves breaking down annual targets into manageable short-term objectives that can be integrated smoothly into everyday lesson planning and differentiated instruction.

Successful IEP implementation relies on clear communication channels between all stakeholders and flexible adaptation of teaching strategies based on ongoing assessment data. Consider establishing weekly check-ins with teaching assistants and monthly discussions with parents to maintain momentum and address emerging challenges promptly. Remember that quality individual planning is an evolving process, not a static document, requiring continuous refinement to meet each pupil's changing needs and circumstances.

The physical classroom environment serves as the foundation for inclusive learning, directly impacting how effectively pupils with special educational needs can access the curriculum. Research by Karen Mapp emphasises that environmental factors significantly influence student engagement and academic outcomes, particularly for learners with sensory processing differences or attention difficulties. Creating an accessible space requires careful consideration of lighting, acoustics, seating arrangements, and visual displays to minimise distractions whilst maximising learning opportunities.

Sensory considerations are paramount when designing inclusive classrooms. Fluorescent lighting can cause distress for pupils with autism or visual processing disorders, making natural light or softer alternatives preferable. Similarly, excessive wall displays may overwhelm students with ADHD or sensory sensitivities, suggesting that strategic use of visual aids is more effective than cluttered environments. Acoustic modifications, such as carpet areas or sound-absorbing materials, can significantly benefit pupils with hearing impairments or auditory processing difficulties.

Practical accessibility extends beyond sensory adjustments to include flexible furniture arrangements and clear pathways for pupils with mobility needs. Designated quiet spaces allow learners to self-regulate when overwhelmed, whilst varied seating options accommodate different physical and concentration requirements. Regular environmental audits, ideally conducted with input from pupils themselves, ensure that classroom modifications continue to meet evolving individual needs effectively.

Supporting pupils with Special Educational Needs is a multifaceted endeavour that requires a deep understanding of individual needs, effective teaching strategies, and collaborative partnerships. By moving beyond labels and embracing a complete approach, educators can create inclusive classrooms where all pupils feel valued, supported, and helped to succeed. High-quality teaching, coupled with targeted interventions and appropriate accommodations, can remove barriers to learning and unlock the potential of every pupil, regardless of their challenges.

Ultimately, the goal is to creates a learning environment that celebrates neurodiversity and promotes equity for all. By investing in training, resources, and support systems, schools can create a culture of inclusion where pupils with SEN thrive academically, socially, and emotionally, and are well-prepared for future success. This commitment not only benefits individual pupils but also enriches the entire school community, developing empathy, understanding, and a shared sense of belonging.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/special-educational-needs#article","headline":"Special Educational Needs","description":"Creating inclusive learning environments for children with Special Educational Needs.","datePublished":"2022-08-18T15:09:53.921Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/special-educational-needs"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a5e2b227f25034f8d7eb2_696a5e2a63b35b989105a383_special-educational-needs-infographic.webp","wordCount":2543},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/special-educational-needs#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Special Educational Needs","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/special-educational-needs"}]}]}