Schema Building: beyond Piaget and into the classroom

Discover how schema theory transforms classroom learning. Paul Cline reveals practical strategies to build student knowledge systematically and improve understanding.

Discover how schema theory transforms classroom learning. Paul Cline reveals practical strategies to build student knowledge systematically and improve understanding.

| Stage | What Happens | Learning Activity | Teacher Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation | Existing knowledge retrieved | Brainstorming, KWL charts | Connect to prior learning |

| Assimilation | New info fits existing schema | Examples, comparisons | Use familiar contexts |

| Accommodation | Schema modified for new info | Challenging examples | Address misconceptions |

| Organisation | Knowledge structured | Concept maps, categories | Show relationships |

| Consolidation | Schema strengthened | Retrieval practice | Spaced review |

Imagine you are travelling abroad by plane. You book a taxi to take you to the airport. When you arrive you find a trolley to carry your luggage and then go look for the check-in desk. You’ll have your passport and tickets at the ready and get given a boarding pass. You’ll drop your luggage off, go through security, and then see how long you can eke out the remaining time browsing in duty-free. Regardless of where you are going, with which airline and from which airport, the story is going to be pretty much the same. If you’ve travelled by plane a few times, you’ve developed a pretty strong schema for airports and plane travel (and even people who haven't will do so if they read about it in books and see it in films and television).

| Key Concept | Definition/Description | Example | Classroom Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schema | Mental model of connected ideas/concepts stored in long-term memory that help organise information through structured frameworks. Graphic organisers support schema construction by providing visual scaffolds for knowledge organizationtured frameworks - graphic organisers support schema construction by providing visual structures for semantic memory - schemas reduce working memory load by chunking related concepts together-term memory - graphic organisers support schema construction by helping visualize these connections-term semantic memory | Airport travel routine (check-in, security, boarding) | Help students build organised knowledge structures |

| Procedural Schema | Knowledge about processes and how to do things | The process of travelling by plane | Teach step-by-step procedures explicitly |

| Declarative Schema | Factual knowledge about concepts | Facts about planes, airports, or travel | Connect facts to create meaningful knowledge networks |

| Assimilation | Adding new information to an existing schema | Learning about a new airline using existing travel knowledge | Build on students' prior knowledge |

| Accommodation | Changing pre-existing schema or creating new ones | Adjusting travel schema for different transportation modes | Address misconceptions and provide contrasting examples |

| Prior Knowledge | Key predictor of learning success | Subject experts have rich, complex schemas | Use advance organisers to connect new to existing knowledge |

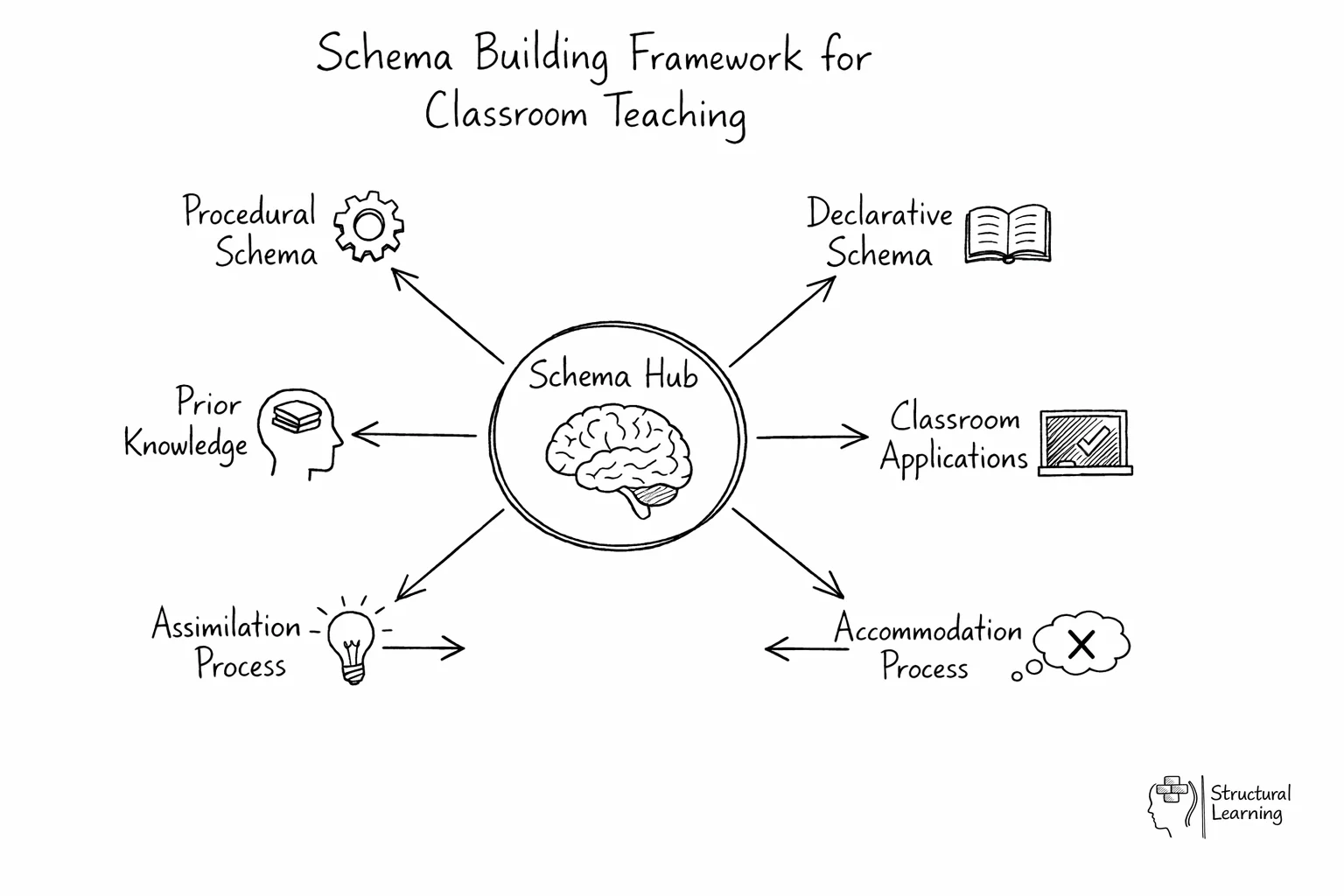

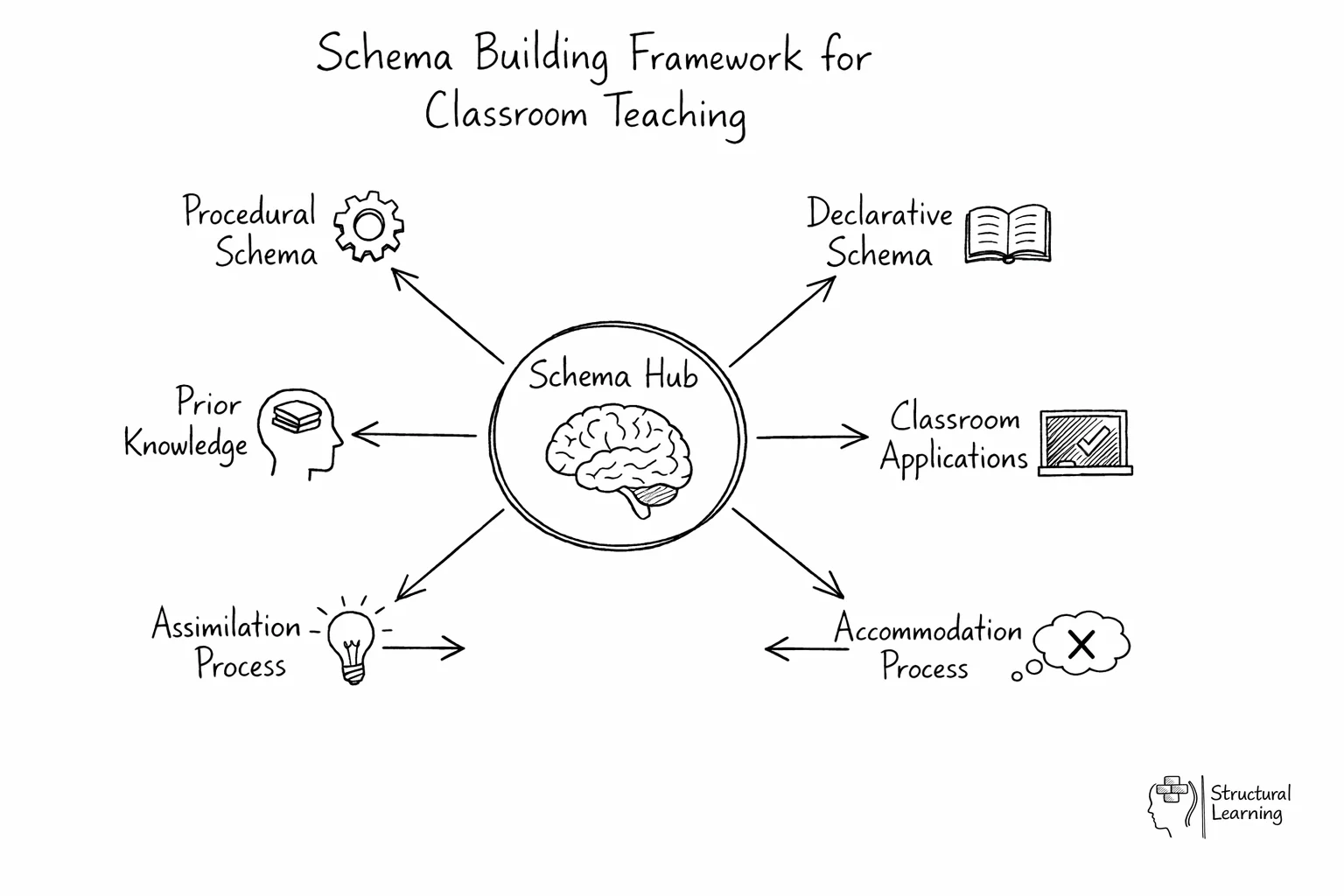

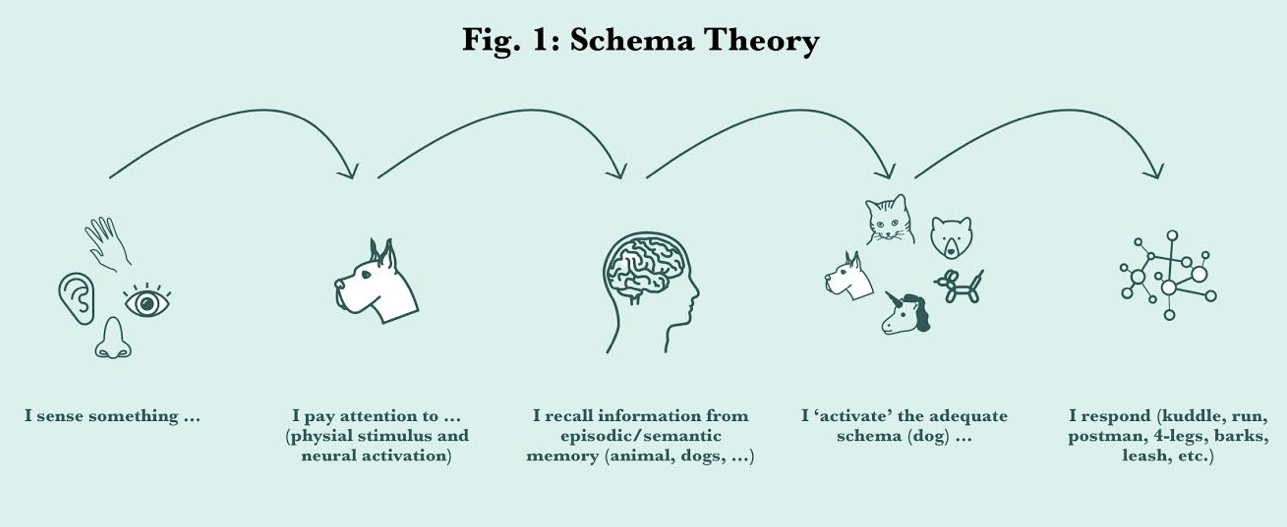

A schema is a mental model of connected ideas or concepts stored in long-term memory that has a particular significance for the development of long-term memories. You might have learned about these if you've studied the work of Swiss Child psychologist Jean Piaget but it’s possible you’ve not really thought (or learned) about them since, or considered how they might apply to classroom teaching. However, they form a cornerstone of Cognitive Science, which has contributed much to the discourse around classroom pedagogy recently.

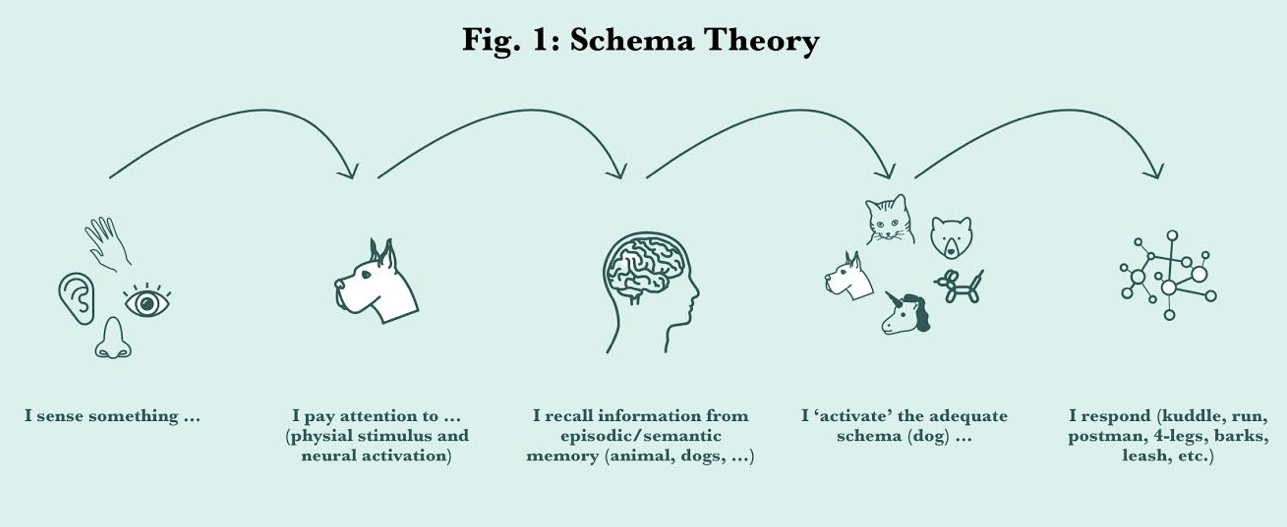

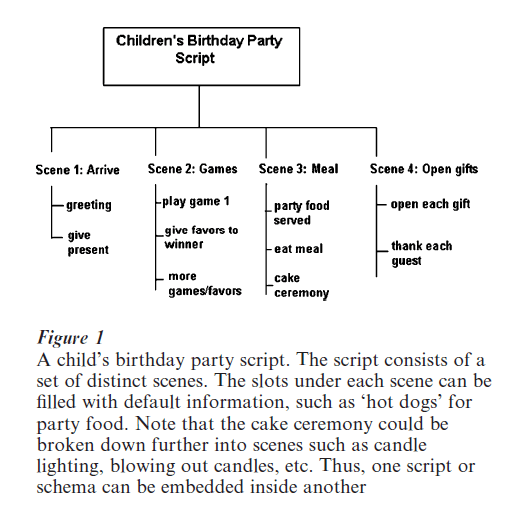

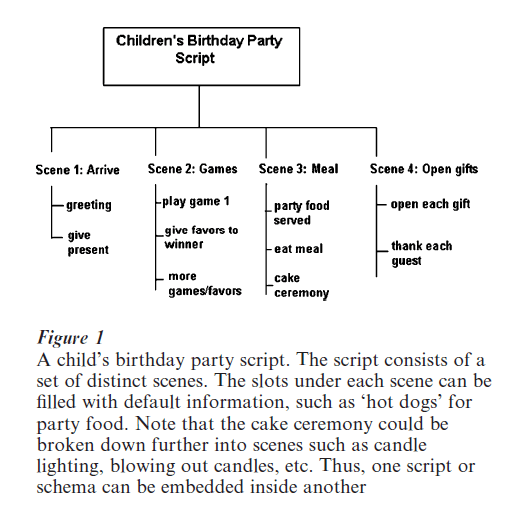

According to Piaget, knowledge is built through the adaptation of schemas (or schemata) through processes such as assimilation (we add new information to an existing schema) or accommodation (we change our pre-existing schema in light of new information, or create new schemas). There are different types of schemas, so when you think about air travel you automatically activate a range of related ideas including the process of travelling by plane (procedural schemas), but also myriad facts related to planes, airports or travel in general (declarative schemas).

Schemas allow us to deal with the world more efficiently by having this mental structure comprised of automated chunks of knowledge. If you decide to go on holiday you know what to expect, even if it’s an airport you’ve never been to, or an airline you’ve never flown with. If someone else has a roughly similar schema for something then there will be shared understanding which means we don’t have to keep explaining everything to each other all of the time.

Schemas are the building blocks of knowledge, and our job as teachers is as much to help students build their own schemas as anything else. As subject experts we hold large, complex and rich schemas in our minds which we need to expose, disentangle and make sense of to our students. Psychologists have shown that what makes us subject experts isn’t because we are just better at it, it’s because we just have huge amounts of knowledge already stored in long-term memory (eg Simon, 1973). Prior knowledge is also key predictor of learning; new information is easier to understand and remember if it can be connected to what we already know (eg Recht & Leslie, 1983).

Understanding the role of schemas has clear applications to our classrooms. I will consider three different ideas in more detail here, with an example of an application for each:

Idea and Application

Connecting new information to what students already know > Advance organisers

Building understanding of conceptual ideas > Examples and non-examples

Assessing the content and organisation of students’ schemas > Multiple choice questions

On its most basic level, the human mind needs to build different types of schema in order to retain and understand new information. We can use the concept of Schema to change our perspectives on how we teach curriculum content.

If we think about the learning journey as a series of blocks of cognition then this helps us think about the process of learning as a constructivist activity. Our aim, as teachers, is to help students build cognitive structures containing the facts and relationships of the different elements of a body of knowledge. Approaching instructional tasks this way enables us to see understanding as the result of a series of active cognitive processes.

Schema Theory" id="" width="auto" height="auto">

Schema Theory" id="" width="auto" height="auto">

Students connect new information by actively linking it to their existing mental schemas through comparison, categorisation, and finding relationships. Teachers facilitate this by explicitly referencing prior knowledge before introducing new concepts and using familiar examples as bridges. This process strengthens memory retention and deepens understanding of new material.

Having clear schemas means that students understand not only the ideas themselves, but their relationship with each other. Everything slots into place, forming rich, interconnected webs of knowledge in long-term memory. Therefore setting each new set of content in its place is key. I’ve been using advance organisers* for some time to help with this. These are often diagrammatic (although lists and tables work too) and help students to see the overview of what they are learning and where the current material fits within the bigger picture.

This is an example I’ve created for the Criminal Psychology topic. It’s important to note that the first time I show this I would animate it to allow me to introduce and explain each section at a time, slowly building up the bigger picture. After that, I show it at some point pretty much every lesson and often use it as a prompt for some retrieval practice activities.

Being able to root new learning in what they already know makes new content more easily understood and remembered (for more on the use of advance organisers I’d highly recommend teacher & author David Goodwin’s post here).

*These are not the same thing as Knowledge Organisers which are far more detailed and serve a different purpose.

Students build conceptual understanding by examining multiple examples and non-examples that highlight critical features of a concept. Teachers should present contrasting cases that reveal what makes something part of a category versus what excludes it. This approach helps students develop flexible, accurate mental models rather than rigid memorization.

I’m sure most teachers use examples to teach new concepts; we all have what we think of as a perfect example we use for a particular topic that we’re sure helps make the abstract concrete, and brings a concept to life for students. And until relatively recently I’d have presumed that this was enough to help my students learn. But the problem with this approach is that one example just isn’t enough.

Examples rely on domain-specific prior knowledge

It may be that the specific example relies on some wider prior knowledge which the students don’t have. For example, I always used to introduce the concept of validity in relation to the well known Ronseal TM advertising slogan (“Does exactly what it says on the tin”) until I realised that it wasn’t as well known as I thought; most students had never seen the advert so I just had to explain that as well too. My example made things less clear because I was adding extraneous, irrelevant material.

Single examples are not sufficient to clarify conceptual ideas

Students may be confused about the underlying conceptual ideas because they focus on the surface features of the example. For example if you only refer to Romeo & Juliet when teaching students about Shakespearean tragedies then they might wrongly presume that a tragedy must include an ill-fated love story.

Examples need to be contrasted with non-examples

Students may not fully grasp what else should be in the same category or group as the original example. Letting students see the ‘boundary conditions’ of a particular idea or concept by exposing them to multiple things which do or don’t fit the category is a much more concrete way for them to truly learn the distinction between different concepts. Using the Shakespeare example again, providing a list of Shakespearean tragedies as well as comedies and dramas, and highlighting which is which, will help them generate a more global conception of what the category ‘tragedy’ actually means than a mere definition or list of criteria would alone.

Since new learning is mediated by prior knowledge, determining what students know is important before we decide to move on. It’s also important to find out, as much as possible, how students' knowledge is organised to identify any significant misconceptions or problems before they get too deeply ingrained. A well designed multiple choice question (MCQ) can be really valuable here.

Good MCQs require that students have to think hard about which is the correct answer; the distractor options should be both plausible and related to the sorts of typical misconceptions that students have in their knowledge (if you’re familiar with the quiz show “Who wants to be a millionaire” then think of this as the million pound question, not the £500 question). For example, here is a question I might ask my Psychology students:

Which of these neurotransmitters is primarily associated with aggression?

Of course, it’s also possible that they just guessed and having a strategy to determine that is useful here too (in class mine typically answer on mini-whiteboards so I might get them to just put a ? next to their answer if it’s a guess). Either way, once you have your responses, taking time to unpack both the correct and incorrect answers is useful in helping to figure out what they currently think, and correct or reinforce their conceptual understanding.

Final thoughts on Schema Building

I don’t pretend that the strategies I’ve outlined here are in any way revolutionary; many teachers will be familiar with and use them already. But I think seeing the underpinning connections, the importance of trying to help students build strong schemas, provides a useful mental structure (a schema!) in which to consider how best to help our students learn. Cognitive processes remain hidden inside our mind and this makes them abstract for students (and teachers) to understand. The human mind is a complex place and understanding a few basic principles of cognition can have a significant impact in the classroom.

Here's how to systematically build and strengthen student schemas across any subject area.

A Year 8 English teacher introducing persuasive techniques starts by asking students about adverts they've seen. She maps their existing knowledge on the board, then introduces a graphic organiser showing ethos, pathos and logos. Students analyse both effective adverts and deliberately weak examples, completing the organiser as they identify techniques. A follow-up quiz includes wrong answers that reveal common misconceptions about audience and purpose.

Schemas are mental models of connected ideas or concepts stored in long-term memory that help us organise and understand information efficiently. They are crucial for learning because new information is easier to understand and remember when it can be connected to existing knowledge structures. As teachers, helping students build rich, interconnected schemas is fundamental to developing deep understanding rather than isolated facts.

Advance organisers are diagrammatic overviews that show students where new content fits within the bigger picture of their learning. Teachers should introduce these gradually, animating sections to build up understanding, then reference them regularly in lessons for retrieval practice. This helps students see relationships between concepts and root new learning in what they already know.

Examples show what belongs to a concept, whilst non-examples demonstrate what doesn't belong, helping students identify the critical features that define a concept. Using contrasting cases prevents students from developing misconceptions and helps them build flexible, accurate understanding. One perfect example isn't enough - students need multiple varied examples and clear non-examples to truly grasp conceptual boundaries.

Well-designed multiple choice questions can expose students' thinking patterns and reveal hidden misconceptions about how they've organised concepts in their schemas. Rather than simply testing right or wrong answers, strategic distractors can show teachers exactly where students' understanding breaks down. This allows teachers to address specific schema gaps and misconceptions more effectively.

Subject experts have vast, interconnected knowledge networks that need to be deliberately unpacked and made explicit for students. Break down your expert understanding into smaller, connected pieces and show students the relationships between concepts step by step. Remember that your expertise comes from having rich schemas built over time, not natural ability, so be patient as students construct their own knowledge networks.

Assimilation occurs when students add new information to existing schemas, like learning about a new airline using their existing travel knowledge. Accommodation happens when students must change their existing schemas or create entirely new ones, such as adjusting their travel schema for different transportation modes. Teachers need to recognise when students need to accommodate rather than just assimilate, often requiring explicit attention to misconceptions.

Procedural schemas involve knowledge about processes and how to do things, whilst declarative schemas contain factual knowledge about concepts. Both types work together - for example, airport travel involves procedural knowledge of the check-in process and declarative knowledge about planes and airports. Teachers should explicitly teach step-by-step procedures whilst connecting factual knowledge into meaningful networks rather than isolated pieces.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into schema building: beyond piaget and into the classroom and its application in educational settings.

Moving from Novice to Expertise and Its Implications for Instruction 151 citations

Persky et al. (2017)

This paper examines how learners progress from novice to expert status, identifying key differences in knowledge organisation and cognitive processing between these stages. For teachers working on schema building, it provides crucial insights into how students' developing expertise affects their ability to integrate new information into existing knowledge structures, helping educators design instruction that matches students' current level of schema development.

Using cognitive load theory to evaluate and improve preparatory materials and study time for the flipped classroom View study ↗17 citations

Fischer et al. (2023)

This study applies cognitive load theoryto improve flipped classroom materials in medical education, focusing on how to design preparatory content that doesn't overwhelm students' cognitive capacity. Teachers interested in schema building can learn how to structure learning materials to support gradual schema construction without causing cognitive overload, ensuring students can effectively process and integrate new information.

Expert-Novice Differences in Teaching: A Cognitive Analysis and Implications for Teacher Education 276 citations

Livingston et al. (1989)

This research analyses the cognitive differences between novice and expert teachers, examining how experienced educators organise and apply their professional knowledge differently than beginners. The findings help teachers understand how their own professional schemas develop over time and how this impacts their ability to recognise and respond to student learning needs during schema-building activities.

Professional Vision and the Compensatory Effect of a Minimal Instructional Intervention: A Quasi-Experimental Eye-Tracking Study With Novice and Expert Teachers 22 citations

Grub et al. (2022)

This eye-tracking study investigates how novice and expert teachers differ in their ability to quickly identify potential learning disruptions in classroom environments. For educators focused on schema building, this research highlights the importance of developing professional vision skills to recognise when students are struggling to construct or modify their mental schemas, enabling more timely instructional interventions.

Research on knowledge sharing and psychological empowerment 52 citations (Author, Year) demonstrates how organisational memory serves as a crucial mediating factor in higher education institutions, revealing the pathways through which collaborative information exchange enhances staff empowerment and institutional effectiveness.

Feiz et al. (2019)

This paper explores how knowledge sharing practices in higher education institutions can psychologically helps faculty members through enhanced organisational memory systems. While not directly about student learning, it offers insights for teachers on how collaborative knowledge building and schema sharing among educators can improve instructional effectiveness and support better schema-building approaches in their classrooms.

| Stage | What Happens | Learning Activity | Teacher Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation | Existing knowledge retrieved | Brainstorming, KWL charts | Connect to prior learning |

| Assimilation | New info fits existing schema | Examples, comparisons | Use familiar contexts |

| Accommodation | Schema modified for new info | Challenging examples | Address misconceptions |

| Organisation | Knowledge structured | Concept maps, categories | Show relationships |

| Consolidation | Schema strengthened | Retrieval practice | Spaced review |

Imagine you are travelling abroad by plane. You book a taxi to take you to the airport. When you arrive you find a trolley to carry your luggage and then go look for the check-in desk. You’ll have your passport and tickets at the ready and get given a boarding pass. You’ll drop your luggage off, go through security, and then see how long you can eke out the remaining time browsing in duty-free. Regardless of where you are going, with which airline and from which airport, the story is going to be pretty much the same. If you’ve travelled by plane a few times, you’ve developed a pretty strong schema for airports and plane travel (and even people who haven't will do so if they read about it in books and see it in films and television).

| Key Concept | Definition/Description | Example | Classroom Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schema | Mental model of connected ideas/concepts stored in long-term memory that help organise information through structured frameworks. Graphic organisers support schema construction by providing visual scaffolds for knowledge organizationtured frameworks - graphic organisers support schema construction by providing visual structures for semantic memory - schemas reduce working memory load by chunking related concepts together-term memory - graphic organisers support schema construction by helping visualize these connections-term semantic memory | Airport travel routine (check-in, security, boarding) | Help students build organised knowledge structures |

| Procedural Schema | Knowledge about processes and how to do things | The process of travelling by plane | Teach step-by-step procedures explicitly |

| Declarative Schema | Factual knowledge about concepts | Facts about planes, airports, or travel | Connect facts to create meaningful knowledge networks |

| Assimilation | Adding new information to an existing schema | Learning about a new airline using existing travel knowledge | Build on students' prior knowledge |

| Accommodation | Changing pre-existing schema or creating new ones | Adjusting travel schema for different transportation modes | Address misconceptions and provide contrasting examples |

| Prior Knowledge | Key predictor of learning success | Subject experts have rich, complex schemas | Use advance organisers to connect new to existing knowledge |

A schema is a mental model of connected ideas or concepts stored in long-term memory that has a particular significance for the development of long-term memories. You might have learned about these if you've studied the work of Swiss Child psychologist Jean Piaget but it’s possible you’ve not really thought (or learned) about them since, or considered how they might apply to classroom teaching. However, they form a cornerstone of Cognitive Science, which has contributed much to the discourse around classroom pedagogy recently.

According to Piaget, knowledge is built through the adaptation of schemas (or schemata) through processes such as assimilation (we add new information to an existing schema) or accommodation (we change our pre-existing schema in light of new information, or create new schemas). There are different types of schemas, so when you think about air travel you automatically activate a range of related ideas including the process of travelling by plane (procedural schemas), but also myriad facts related to planes, airports or travel in general (declarative schemas).

Schemas allow us to deal with the world more efficiently by having this mental structure comprised of automated chunks of knowledge. If you decide to go on holiday you know what to expect, even if it’s an airport you’ve never been to, or an airline you’ve never flown with. If someone else has a roughly similar schema for something then there will be shared understanding which means we don’t have to keep explaining everything to each other all of the time.

Schemas are the building blocks of knowledge, and our job as teachers is as much to help students build their own schemas as anything else. As subject experts we hold large, complex and rich schemas in our minds which we need to expose, disentangle and make sense of to our students. Psychologists have shown that what makes us subject experts isn’t because we are just better at it, it’s because we just have huge amounts of knowledge already stored in long-term memory (eg Simon, 1973). Prior knowledge is also key predictor of learning; new information is easier to understand and remember if it can be connected to what we already know (eg Recht & Leslie, 1983).

Understanding the role of schemas has clear applications to our classrooms. I will consider three different ideas in more detail here, with an example of an application for each:

Idea and Application

Connecting new information to what students already know > Advance organisers

Building understanding of conceptual ideas > Examples and non-examples

Assessing the content and organisation of students’ schemas > Multiple choice questions

On its most basic level, the human mind needs to build different types of schema in order to retain and understand new information. We can use the concept of Schema to change our perspectives on how we teach curriculum content.

If we think about the learning journey as a series of blocks of cognition then this helps us think about the process of learning as a constructivist activity. Our aim, as teachers, is to help students build cognitive structures containing the facts and relationships of the different elements of a body of knowledge. Approaching instructional tasks this way enables us to see understanding as the result of a series of active cognitive processes.

Schema Theory" id="" width="auto" height="auto">

Schema Theory" id="" width="auto" height="auto">

Students connect new information by actively linking it to their existing mental schemas through comparison, categorisation, and finding relationships. Teachers facilitate this by explicitly referencing prior knowledge before introducing new concepts and using familiar examples as bridges. This process strengthens memory retention and deepens understanding of new material.

Having clear schemas means that students understand not only the ideas themselves, but their relationship with each other. Everything slots into place, forming rich, interconnected webs of knowledge in long-term memory. Therefore setting each new set of content in its place is key. I’ve been using advance organisers* for some time to help with this. These are often diagrammatic (although lists and tables work too) and help students to see the overview of what they are learning and where the current material fits within the bigger picture.

This is an example I’ve created for the Criminal Psychology topic. It’s important to note that the first time I show this I would animate it to allow me to introduce and explain each section at a time, slowly building up the bigger picture. After that, I show it at some point pretty much every lesson and often use it as a prompt for some retrieval practice activities.

Being able to root new learning in what they already know makes new content more easily understood and remembered (for more on the use of advance organisers I’d highly recommend teacher & author David Goodwin’s post here).

*These are not the same thing as Knowledge Organisers which are far more detailed and serve a different purpose.

Students build conceptual understanding by examining multiple examples and non-examples that highlight critical features of a concept. Teachers should present contrasting cases that reveal what makes something part of a category versus what excludes it. This approach helps students develop flexible, accurate mental models rather than rigid memorization.

I’m sure most teachers use examples to teach new concepts; we all have what we think of as a perfect example we use for a particular topic that we’re sure helps make the abstract concrete, and brings a concept to life for students. And until relatively recently I’d have presumed that this was enough to help my students learn. But the problem with this approach is that one example just isn’t enough.

Examples rely on domain-specific prior knowledge

It may be that the specific example relies on some wider prior knowledge which the students don’t have. For example, I always used to introduce the concept of validity in relation to the well known Ronseal TM advertising slogan (“Does exactly what it says on the tin”) until I realised that it wasn’t as well known as I thought; most students had never seen the advert so I just had to explain that as well too. My example made things less clear because I was adding extraneous, irrelevant material.

Single examples are not sufficient to clarify conceptual ideas

Students may be confused about the underlying conceptual ideas because they focus on the surface features of the example. For example if you only refer to Romeo & Juliet when teaching students about Shakespearean tragedies then they might wrongly presume that a tragedy must include an ill-fated love story.

Examples need to be contrasted with non-examples

Students may not fully grasp what else should be in the same category or group as the original example. Letting students see the ‘boundary conditions’ of a particular idea or concept by exposing them to multiple things which do or don’t fit the category is a much more concrete way for them to truly learn the distinction between different concepts. Using the Shakespeare example again, providing a list of Shakespearean tragedies as well as comedies and dramas, and highlighting which is which, will help them generate a more global conception of what the category ‘tragedy’ actually means than a mere definition or list of criteria would alone.

Since new learning is mediated by prior knowledge, determining what students know is important before we decide to move on. It’s also important to find out, as much as possible, how students' knowledge is organised to identify any significant misconceptions or problems before they get too deeply ingrained. A well designed multiple choice question (MCQ) can be really valuable here.

Good MCQs require that students have to think hard about which is the correct answer; the distractor options should be both plausible and related to the sorts of typical misconceptions that students have in their knowledge (if you’re familiar with the quiz show “Who wants to be a millionaire” then think of this as the million pound question, not the £500 question). For example, here is a question I might ask my Psychology students:

Which of these neurotransmitters is primarily associated with aggression?

Of course, it’s also possible that they just guessed and having a strategy to determine that is useful here too (in class mine typically answer on mini-whiteboards so I might get them to just put a ? next to their answer if it’s a guess). Either way, once you have your responses, taking time to unpack both the correct and incorrect answers is useful in helping to figure out what they currently think, and correct or reinforce their conceptual understanding.

Final thoughts on Schema Building

I don’t pretend that the strategies I’ve outlined here are in any way revolutionary; many teachers will be familiar with and use them already. But I think seeing the underpinning connections, the importance of trying to help students build strong schemas, provides a useful mental structure (a schema!) in which to consider how best to help our students learn. Cognitive processes remain hidden inside our mind and this makes them abstract for students (and teachers) to understand. The human mind is a complex place and understanding a few basic principles of cognition can have a significant impact in the classroom.

Here's how to systematically build and strengthen student schemas across any subject area.

A Year 8 English teacher introducing persuasive techniques starts by asking students about adverts they've seen. She maps their existing knowledge on the board, then introduces a graphic organiser showing ethos, pathos and logos. Students analyse both effective adverts and deliberately weak examples, completing the organiser as they identify techniques. A follow-up quiz includes wrong answers that reveal common misconceptions about audience and purpose.

Schemas are mental models of connected ideas or concepts stored in long-term memory that help us organise and understand information efficiently. They are crucial for learning because new information is easier to understand and remember when it can be connected to existing knowledge structures. As teachers, helping students build rich, interconnected schemas is fundamental to developing deep understanding rather than isolated facts.

Advance organisers are diagrammatic overviews that show students where new content fits within the bigger picture of their learning. Teachers should introduce these gradually, animating sections to build up understanding, then reference them regularly in lessons for retrieval practice. This helps students see relationships between concepts and root new learning in what they already know.

Examples show what belongs to a concept, whilst non-examples demonstrate what doesn't belong, helping students identify the critical features that define a concept. Using contrasting cases prevents students from developing misconceptions and helps them build flexible, accurate understanding. One perfect example isn't enough - students need multiple varied examples and clear non-examples to truly grasp conceptual boundaries.

Well-designed multiple choice questions can expose students' thinking patterns and reveal hidden misconceptions about how they've organised concepts in their schemas. Rather than simply testing right or wrong answers, strategic distractors can show teachers exactly where students' understanding breaks down. This allows teachers to address specific schema gaps and misconceptions more effectively.

Subject experts have vast, interconnected knowledge networks that need to be deliberately unpacked and made explicit for students. Break down your expert understanding into smaller, connected pieces and show students the relationships between concepts step by step. Remember that your expertise comes from having rich schemas built over time, not natural ability, so be patient as students construct their own knowledge networks.

Assimilation occurs when students add new information to existing schemas, like learning about a new airline using their existing travel knowledge. Accommodation happens when students must change their existing schemas or create entirely new ones, such as adjusting their travel schema for different transportation modes. Teachers need to recognise when students need to accommodate rather than just assimilate, often requiring explicit attention to misconceptions.

Procedural schemas involve knowledge about processes and how to do things, whilst declarative schemas contain factual knowledge about concepts. Both types work together - for example, airport travel involves procedural knowledge of the check-in process and declarative knowledge about planes and airports. Teachers should explicitly teach step-by-step procedures whilst connecting factual knowledge into meaningful networks rather than isolated pieces.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into schema building: beyond piaget and into the classroom and its application in educational settings.

Moving from Novice to Expertise and Its Implications for Instruction 151 citations

Persky et al. (2017)

This paper examines how learners progress from novice to expert status, identifying key differences in knowledge organisation and cognitive processing between these stages. For teachers working on schema building, it provides crucial insights into how students' developing expertise affects their ability to integrate new information into existing knowledge structures, helping educators design instruction that matches students' current level of schema development.

Using cognitive load theory to evaluate and improve preparatory materials and study time for the flipped classroom View study ↗17 citations

Fischer et al. (2023)

This study applies cognitive load theoryto improve flipped classroom materials in medical education, focusing on how to design preparatory content that doesn't overwhelm students' cognitive capacity. Teachers interested in schema building can learn how to structure learning materials to support gradual schema construction without causing cognitive overload, ensuring students can effectively process and integrate new information.

Expert-Novice Differences in Teaching: A Cognitive Analysis and Implications for Teacher Education 276 citations

Livingston et al. (1989)

This research analyses the cognitive differences between novice and expert teachers, examining how experienced educators organise and apply their professional knowledge differently than beginners. The findings help teachers understand how their own professional schemas develop over time and how this impacts their ability to recognise and respond to student learning needs during schema-building activities.

Professional Vision and the Compensatory Effect of a Minimal Instructional Intervention: A Quasi-Experimental Eye-Tracking Study With Novice and Expert Teachers 22 citations

Grub et al. (2022)

This eye-tracking study investigates how novice and expert teachers differ in their ability to quickly identify potential learning disruptions in classroom environments. For educators focused on schema building, this research highlights the importance of developing professional vision skills to recognise when students are struggling to construct or modify their mental schemas, enabling more timely instructional interventions.

Research on knowledge sharing and psychological empowerment 52 citations (Author, Year) demonstrates how organisational memory serves as a crucial mediating factor in higher education institutions, revealing the pathways through which collaborative information exchange enhances staff empowerment and institutional effectiveness.

Feiz et al. (2019)

This paper explores how knowledge sharing practices in higher education institutions can psychologically helps faculty members through enhanced organisational memory systems. While not directly about student learning, it offers insights for teachers on how collaborative knowledge building and schema sharing among educators can improve instructional effectiveness and support better schema-building approaches in their classrooms.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/schema-building#article","headline":"Schema Building: beyond Piaget and into the classroom","description":"Paul Cline explains the significance of Schema formation and what it means for classroom practitioners. ","datePublished":"2022-07-04T16:36:52.061Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/schema-building"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a3ea4ee0a09e3fe5dedbb_696a3e9fa0912a9f452c3113_schema-building-illustration.webp","wordCount":2603},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/schema-building#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Schema Building: beyond Piaget and into the classroom","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/schema-building"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/schema-building#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers use advance organisers to help students build schemas?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Advance organisers are diagrammatic overviews that show students where new content fits within the bigger picture of their learning. Teachers should introduce these gradually, animating sections to build up understanding, then reference them regularly in lessons for"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What's the difference between examples and non-examples, and why should I use both?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Examples show what belongs to a concept, whilst non-examples demonstrate what doesn't belong, helping students identify the critical features that define a concept. Using contrasting cases prevents students from developing misconceptions and helps them build flexible, accurate understanding. One per"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can multiple choice questions reveal how students organise their knowledge?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Well-designed multiple choice questions can expose students' thinking patterns and reveal hidden misconceptions about how they've organised concepts in their schemas. Rather than simply testing right or wrong answers, strategic distractors can show teachers exactly where students' understanding brea"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"As a subject expert, how do I make my complex schemas accessible to students?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Subject experts have vast, interconnected knowledge networks that need to be deliberately unpacked and made explicit for students. Break down your expert understanding into smaller, connected pieces and show students the relationships between concepts step by step. Remember that your expertise comes"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What's the difference between assimilation and accommodation in schema building?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Assimilation occurs when students add new information to existing schemas, like learning about a new airline using their existing travel knowledge. Accommodation happens when students must change their existing schemas or create entirely new ones, such as adjusting their travel schema for different "}}]}]}