Kolb's Learning Cycle: The Four Stages of Experiential Learning

Master Kolb's experiential learning cycle: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation stages.

Master Kolb's experiential learning cycle: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation stages.

David Kolb's experiential learning cycle is one of the most widely used models in education and training. The cycle proposes that effective learning involves four stages: having a concrete experience, reflecting on that experience, forming abstract concepts, and actively experimenting with new ideas. While the associated learning styles have been criticised, the cycle itself provides a useful framework for designing learning experiences that move beyond passive reception to active engagement with material.

The idea is simple but powerful: learners don't just absorb information, they make sense of it by doing, reflecting, thinking, and applying. Kolb's cycle captures this process, helping educators understand how students engage with content, reflect on their understanding, form concepts through cognitive development, and test new ideas in real contexts and social learning theory.

In an era where evidence-informed teaching is reshaping educational practise, Kolb's work offers a grounded framework for designing learning that is active, reflective, and deeply connected to real-world experiences. Whether you're working in early years, secondary, or higher education, understanding how experience becomes learning is vital for improving student outcomes.

Experiential learning is no longer confined to internships or vocational training. With the rise of project-based learning, flipped classrooms, and real-world simulation strong>, Kolb's cycle offers a valuable lens for designing meaningful, student-centred experiences that go beyond rote learning. For an immersive approach to this topic, explore Mantle of the Expert, a drama-based inquiry method.

By understanding Kolb's framework, teachers can create more dynamic and responsive learning environments, ones that help students engage more deeply, think more critically, and apply knowledge with confidence.

First published in 1984, Kolb's learning styles are widely used as one of the most renowned learning styles theories. Kolb's theory focuses on the learner's personal development and perspective. Unlike the conventional, didactic method, the learner is responsible to guide his learning process in experiential learning. Experiential learning is a great way to learn because it allows students to apply knowledge in real life situations. Experiential learning encourages active participation, critical thinking, creativity, problem solving, collaboration, and communication skills.

Conventional, didactic methods include lectures, textbooks, and homework assignments. These methods teach facts and concepts, but not necessarily how to apply them in real world situations.

While these two types of teaching styles work well for different purposes, there is no denying that experiential learning is superior when it comes to helping students retain information.

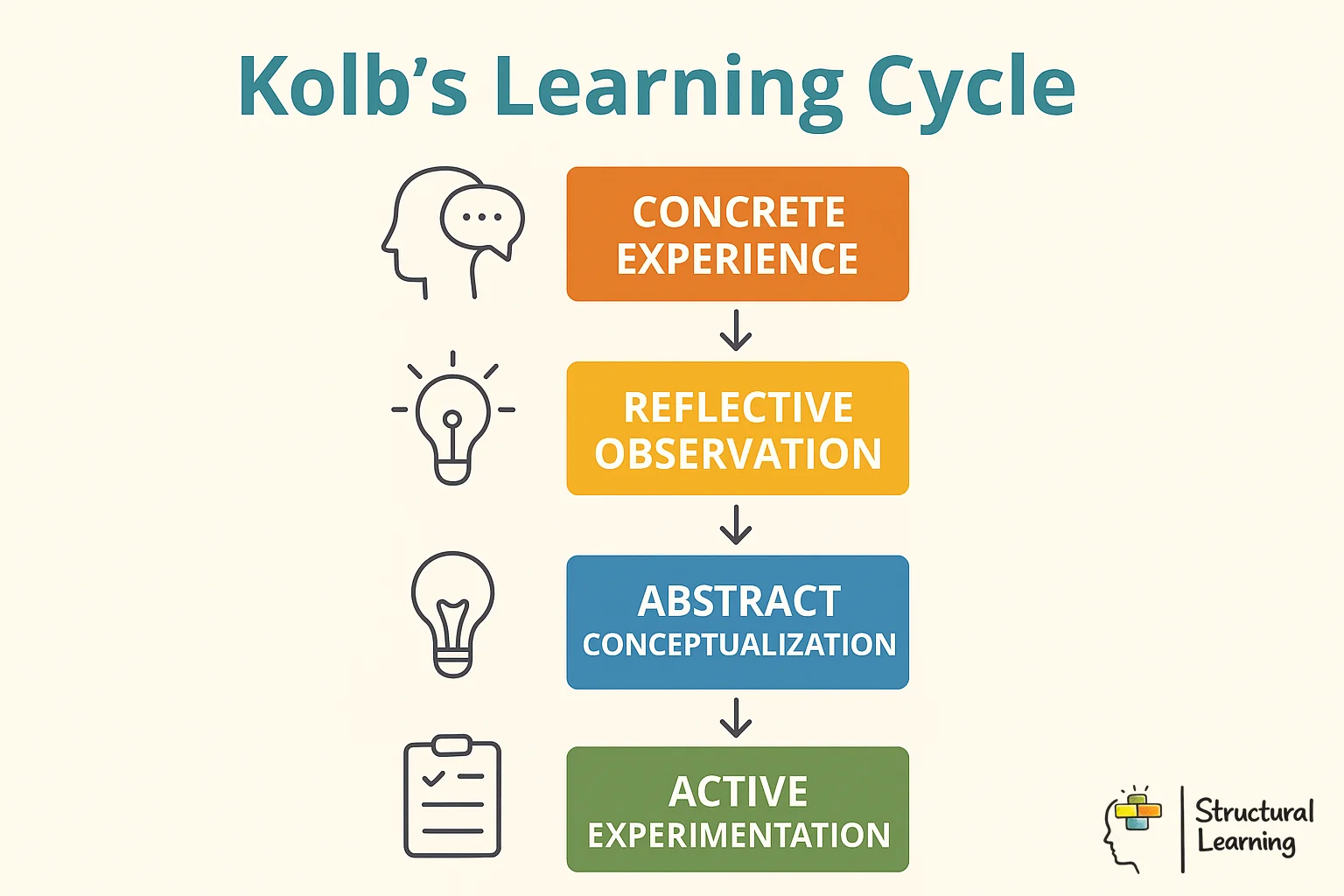

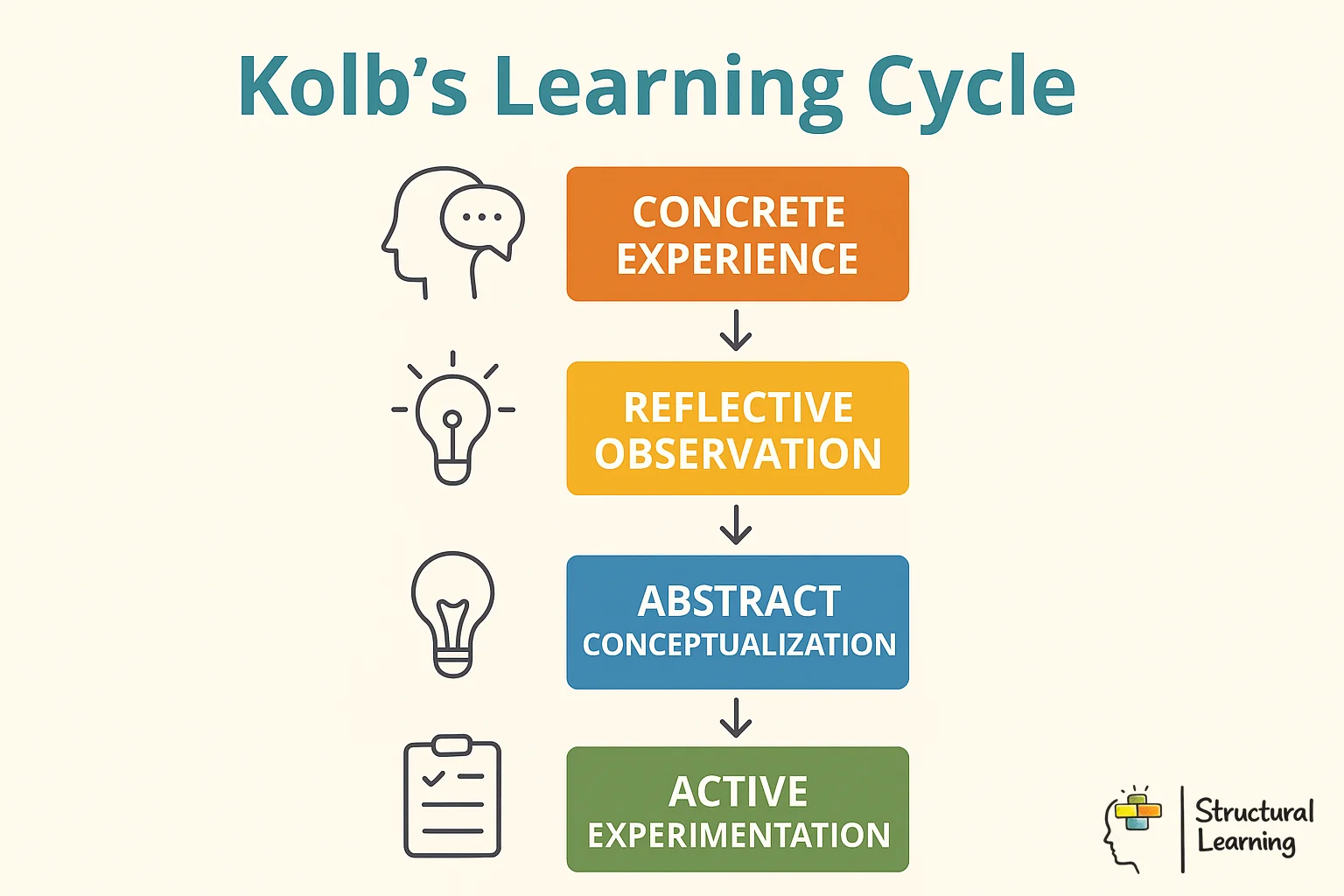

When teaching students, we often use Kolb's Learning Cycle to help them understand the importance of experiential learning. The following model helps illustrate this process:

1. Orientation, Students become familiar with the subject matter through experience (real world) and reflection.

2. Cognitive Processing, Students actively engage in the material through hands-on activities.

3. Retrieval, Students recall the content through memory and repetition.

4. Consolidation, Students integrate the new information into long term memory.

5. Motivation & Evaluation, Students evaluate whether the activity was worthwhile.

6. Integration, Students synthesize the new information into existing knowledge.

7. Application, Students apply the new information to solve problems.

8. Exploration, Students continue to explore the topic further.

If you're looking for ways to improve your online presence, consider adding some experiential learning to your curriculum.

Here is a quick overview of the 4-stages of the Kolb learning styles:

Incorporating Kolb's Learning Cycle into your teaching can transform your classroom into a dynamic, experiential learning centre. Here are some practical strategies to help you implement each stage of the cycle effectively:

By intentionally designing learning experiences that encompass all four stages of Kolb's Learning Cycle, you can create a more engaging, effective, and memorable learning environment for your students. Remember, the goal is to move students beyond passive reception of information to active engagement, reflection, and application.

While Kolb's Learning Cycle provides a valuable framework, implementing it effectively can present some challenges. Here are a few common hurdles and strategies for overcoming them:

Kolb's Learning Cycle offers a powerful framework for designing learning experiences that are deeply engaging, meaningful, and relevant to students' lives. By understanding the four stages of the cycle, concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation, educators can create dynamic learning environments that creates critical thinking, problem-solving, and a lifelong love of learning.

By moving beyond traditional didactic methods and embracing experiential learning, teachers can helps students to become active participants in their own education. This not only enhances their understanding of the subject matter but also equips them with the skills and dispositions needed to succeed in an ever-changing world. Kolb's cycle isn't just a theory; it's a practical guide to creating learning that sticks.

Understanding how Kolb's cycle works in practise transforms it from abstract theory into a powerful teaching tool. Consider a Year 7 science lesson on plant growth. Rather than starting with textbook definitions, students plant seeds in different conditions (concrete experience). They observe and record changes over two weeks, discussing patterns with partners (reflective observation). From their observations, they develop hypotheses about what plants need to thrive (abstract conceptualisation). Finally, they design new experiments to test their theories, perhaps investigating whether music affects growth (active experimentation).

In primary mathematics, the cycle naturally fits hands-on learning. When teaching fractions, pupils might share pizza slices equally among groups (concrete experience), then discuss what they notice about the portions (reflective observation). They work out the mathematical relationships between parts and wholes (abstract conceptualisation), before solving real problems about sharing resources fairly (active experimentation). This approach grounds abstract concepts in tangible experiences that pupils remember.

The cycle proves equally valuable in secondary English. Students might perform scenes from Shakespeare (concrete experience), then write reflective journals about character motivations (reflective observation). Through group analysis, they identify themes and literary techniques (abstract conceptualisation), before creating modern adaptations that demonstrate their understanding (active experimentation). This progression moves students from surface-level reading to deep textual analysis.

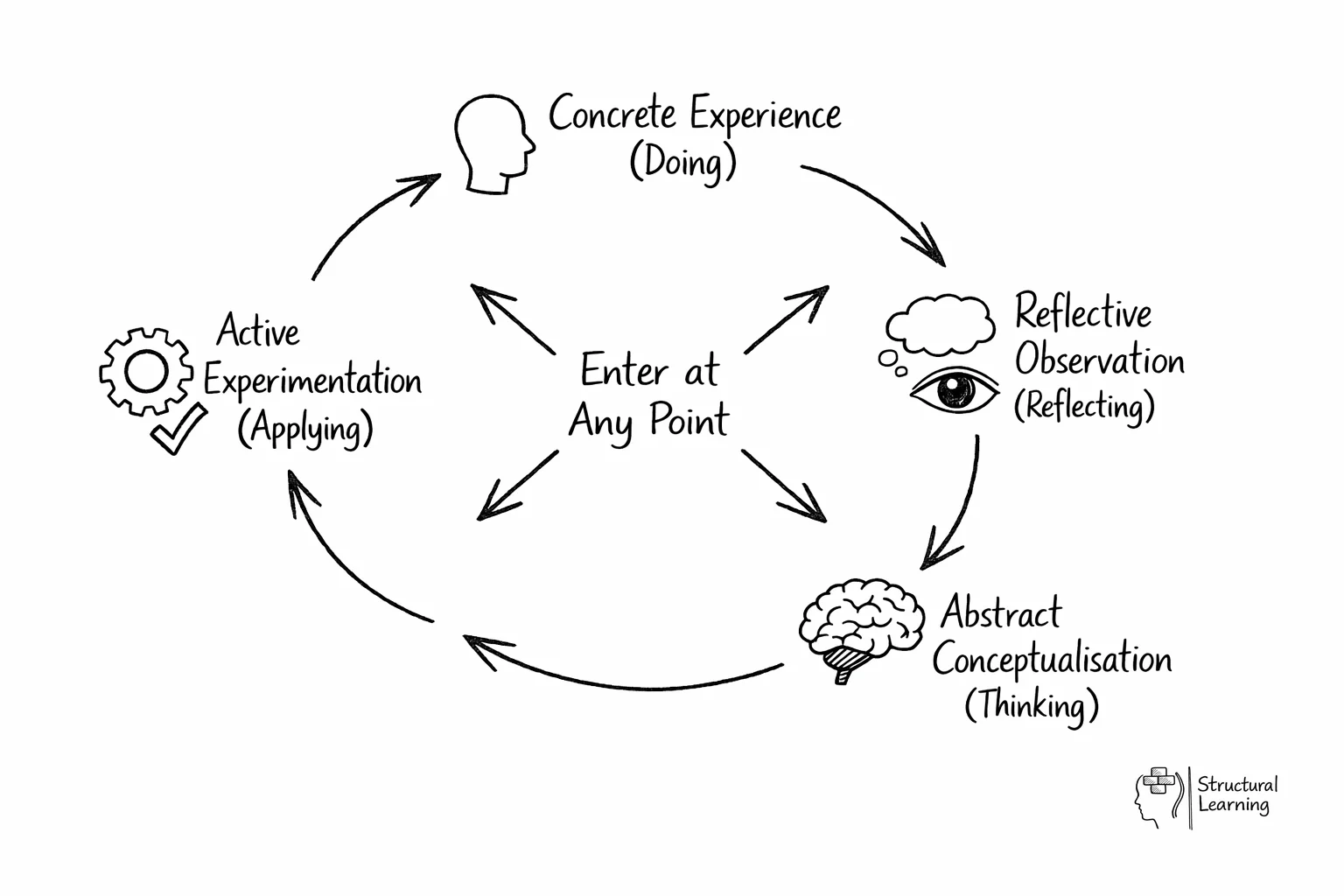

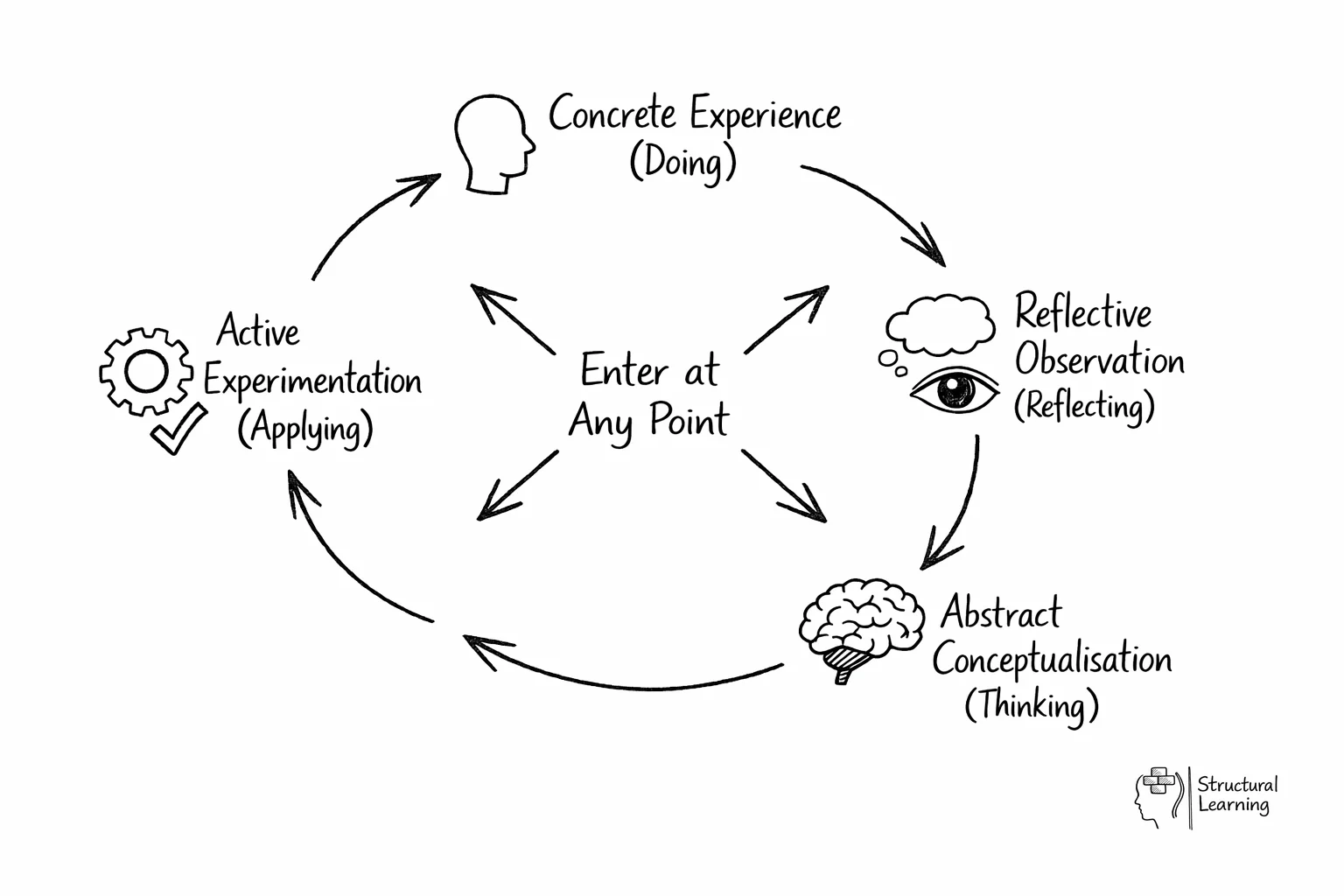

What makes these examples effective is their recognition that learning isn't linear. A history teacher might begin with primary source analysis (starting at reflective observation) or launch straight into role-play debates (beginning with active experimentation). The key is ensuring students complete the full cycle, transforming isolated activities into connected learning experiences that build lasting understanding.

David Kolb, an American educational theorist born in 1939, revolutionised how we think about learning by challenging the traditional lecture-and-memorise approach. Working as a professor at Case Western Reserve University, Kolb drew inspiration from earlier educational pioneers like John Dewey, Jean Piaget, and Kurt Lewin to develop his experiential learning theory in the 1970s.

Kolb's breakthrough came from observing that students retained far more when they actively engaged with material rather than passively receiving it. His doctoral work at Harvard, combined with his experience in organisational behaviour, led him to recognise that effective learning mirrors how we naturally acquire skills outside the classroom: through experience, reflection, conceptualisation, and experimentation.

For teachers, understanding Kolb's background reveals why his cycle works so well in practise. As someone who studied both psychology and social work, Kolb understood that learning isn't just cognitive; it involves emotions, social interactions, and physical experiences. This explains why a Year 7 science student might grasp photosynthesis better after growing plants, observing changes, theorising about causes, and testing different light conditions, rather than simply reading textbook definitions.

Kolb's research with adult learners in professional settings also offers valuable insights for classroom teachers. He discovered that people enter the learning cycle at different points based on their preferences and prior experiences. This finding suggests practical strategies: when teaching fractions, some pupils benefit from starting with concrete manipulatives (concrete experience), whilst others prefer beginning with the abstract concept before moving to hands-on activities. Recognising these entry points helps teachers differentiate instruction more effectively, ensuring all students complete the full learning cycle regardless of where they begin.

Whilst Kolb's learning cycle describes how learning occurs, his Learning Styles Inventory (LSI) suggests that individuals have preferences for different stages of the cycle. According to Kolb, these preferences shape four distinct learning styles: Diverging (feeling and watching), Assimilating (watching and thinking), Converging (thinking and doing), and Accommodating (doing and feeling).

It's crucial to understand that modern research has largely discredited the notion that teaching to specific learning styles improves outcomes. However, recognising that students may have different entry points into the learning cycle remains valuable for classroom practise. A student with strong reflective tendencies might naturally begin with observation, whilst another might prefer jumping straight into hands-on experimentation.

Rather than labelling students or restricting activities, use this knowledge to ensure your lessons provide multiple access points. For instance, when teaching fraction multiplication, you might simultaneously offer manipulatives for those who prefer concrete experience, worked examples for those who favour abstract conceptualisation, and reflection prompts for observers. This isn't about matching teaching to mythical fixed styles; it's about providing rich, varied experiences that allow all students to engage with the full cycle.

Consider using learning journals where students identify which stage of the cycle feels most natural to them in different subjects. A Year 8 student might discover they prefer starting with experimentation in science but need concrete examples first in languages. This metacognitive awareness helps students recognise when they need to push themselves through less comfortable stages, building more complete understanding. The goal isn't to cater to preferences but to help students recognise and work through all four stages, regardless of their starting point.

Transforming Kolb's theoretical framework into classroom practise requires thoughtful planning and a willingness to reshape traditional lesson structures. The key lies in creating opportunities for students to move through all four stages, rather than jumping straight from instruction to assessment.

In primary science, for example, begin with hands-on experiments (concrete experience) before introducing scientific concepts. When teaching plant growth, students might first observe seeds sprouting over several days, documenting changes in a journal. The reflective observation stage follows naturally as children discuss what they noticed, comparing observations with peers. Only then do you introduce abstract concepts like photosynthesis, connecting theory to what students have already seen. Finally, students apply this understanding by designing their own growing conditions, testing variables like light and water.

Secondary history teachers can structure units around historical inquiries that mirror Kolb's cycle. Start with primary sources; letters, photographs, or artefacts that students can examine directly. Rather than immediately explaining historical context, allow time for students to reflect on what these sources reveal and what questions they raise. Guide them towards forming hypotheses about the period before introducing historical interpretations. The cycle completes when students create their own historical arguments using evidence, actively experimenting with the historian's craft.

Professional development sessions benefit from the same approach. Instead of lecture-heavy INSET days, begin with teachers trying new techniques in micro-teaching scenarios. Build in structured reflection time where colleagues share observations without immediate judgement. Connect these experiences to educational research and theory, then provide supported opportunities for teachers to adapt and test strategies in their own classrooms. This approach transforms CPD from passive listening into active professional learning that changes classroom practise.

Kolb's learning cycle comprises four distinct stages that learners progress through, either sequentially or by entering at any point depending on their preferred learning style. Each stage serves a unique purpose in the learning process, and effective educators deliberately incorporate activities that address all four stages to maximise student engagement and understanding. The cycle begins with Concrete Experience, where learners encounter new situations or reframe existing experiences, followed by Reflective Observation, where they step back to consider what occurred from multiple perspectives.

Concrete Experience forms the foundation of the learning cycle, representing the "doing" phase where students actively participate in an activity or encounter new material firsthand. In a Year 7 science lesson exploring density, for example, students might physically handle objects of different weights and sizes, dropping them into water tanks to observe which items float or sink. This hands-on engagement provides the raw material for learning, creating vivid memories and emotional connections that enhance retention. Teachers can facilitate concrete experiences through practical experiments, role-playing exercises, field trips, or case study analyses that immerse students in real-world scenarios.

The Reflective Observation stage encourages learners to step back from their immediate experience and consider what they observed, felt, and noticed. Following the density experiment, students might work in pairs to discuss their observations, noting patterns in which materials floated versus those that sank. This stage is crucial for processing experiences before jumping to conclusions. Teachers can support reflective observation through structured discussion questions, learning journals, peer interviews, or guided observation sheets. Research by Gibbs (1988) emphasises that reflection without structure often lacks depth, making teacher guidance essential during this contemplative phase.

Abstract Conceptualisation represents the theoretical stage where learners connect their experiences and reflections to broader principles, theories, or models. Students examining their density observations might now learn the scientific principle that objects float when their density is less than water's density, understanding the mathematical relationship between mass, volume, and buoyancy. This stage transforms concrete experiences into generalisable knowledge. Teachers facilitate abstract conceptualisation through mini-lectures, research assignments, concept mapping, or guided reading that helps students link their experiences to established theories and frameworks.

Active Experimentation completes the cycle as learners apply their newfound understanding to new situations, testing theories and hypotheses in different contexts. Students who grasp density principles might predict whether various mystery objects will float before testing them, or design boats using different materials to explore practical applications. This stage builds confidence and deepens understanding through purposeful practise. Teachers can create opportunities for active experimentation through problem-solving challenges, design projects, simulations, or real-world applications that allow students to test their learning.

Effective implementation of Kolb's cycle requires teachers to consciously plan activities for each stage while recognising that different students may naturally gravitate towards certain stages based on their learning preferences. A well-structured lesson might begin with concrete experience, allow time for reflection, introduce relevant theory, and conclude with opportunities for experimentation. This cyclical approach ensures comprehensive learning that accommodates diverse learning styles whilst building both practical skills and theoretical understanding across all curriculum areas.

Assessment should match each stage: observe student engagement during concrete experiences, use reflective journals or discussion for reflective observation, check conceptual understanding through mind maps or explanations, and evaluate practical application through real-world tasks. This varied approach provides a comprehensive picture of learning progress across all four stages.

Try think-pair-share discussions, exit tickets with reflection questions, or simple learning logs where students write three things they noticed during the experience. Video diaries, peer feedback sessions, or guided questioning can also help students process their concrete experiences effectively.

There's no fixed timing as it depends on the complexity of the topic and age of students. A single lesson might focus on one or two stages, whilst a complete cycle could span several lessons or even weeks for complex topics. The key is ensuring all stages are eventually covered rather than rushing through each one.

Yes, online platforms can support all four stages effectively. Virtual simulations provide concrete experiences, online discussion boards facilitate reflection, collaborative documents help build abstract concepts, and digital projects enable active experimentation. The key is adapting activities to the digital environment whilst maintaining the cycle's interactive nature.

Whilst Kolb's cycle works across all subjects, it's particularly effective in science (experiments and observations), humanities (role-play and case studies), and practical subjects like design technology. However, even traditionally theoretical subjects like mathematics can benefit from concrete experiences such as real-world problem-solving scenarios.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

The Effectiveness of the 5E Learning Cycle Model in Students' Mathematics Engagement Learning View study ↗

M. Ghunaimat & E. Alawneh (2025)

This recent study demonstrates that the 5E Learning Cycle Model (Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, Evaluate) significantly increases student engagement in mathematics across behavioural, emotional, and cognitive dimensions compared to traditional teaching methods. For math teachers struggling with student motivation, this research provides evidence that structuring lessons around these five phases can help students become more actively involved in their learning. The findings suggest that moving beyond lecture-based instruction to this cyclical approach creates more meaningful mathematical experiences for students.

Student-Centred Active Learning Improves Performance in Solving Higher-Level Cognitive Questions in Health Sciences Education View study ↗

11 citations

N. Martín-Alguacil & L. Avedillo (2024)

Researchers found that when health science students participated in student-centred active learning environments, particularly flipped classrooms, they performed significantly better on complex thinking tasks that required analysis and application rather than just memorization. This study is particularly valuable for educators because it shows that active learning strategies don't just improve engagement, they actually help students develop the critical thinking skills needed for real-world problem solving. The research provides concrete evidence that shifting from teacher-centred to student-centred approaches produces measurable improvements in higher-order thinking abilities.

The Effectiveness of Teaching Derivatives in Vietnamese High Schools Using APOS Theory and ACE Learning Cycle View study ↗

12 citations

N. Thi et al. (2023)

This study successfully combined APOS theory (which focuses on how students build mathematical understanding through Actions, Processes, Objects, and Schemas) with the ACE learning cycle (Activities, Classroom discussion, and Exercises) to teach calculus derivatives more effectively. Vietnamese high school students showed improved conceptual understanding and mathematical competency when teachers used this structured approach rather than traditional methods. The research offers math teachers a practical framework for helping students grasp abstract mathematical concepts by building understanding step by step through hands-on activities and guided discussion.

Interactive Peer Instruction Method Applied to Classroom Environments Considering a Learning Engineering Approach to Innovate the Teaching-Learning Process View study ↗

20 citations

Jessica Rivadeneira & Esteban Inga (2023)

This research explores how peer instruction, a method that uses strategic questioning and student discussion to promote active learning, can transform classrooms where traditional lectures have left students passive and unmotivated. The study shows that when teachers incorporate interactive question and answer dynamics that encourage students to learn from each other, participation and engagement increase dramatically. For educators looking to move away from one-way instruction, this research provides a roadmap for implementing peer-based learning strategies that make students active contributors to their own education.

A Hybrid Classroom Instruction in Second Language Teacher Education (SLTE): A Critical Reflection of Teacher Educators View study ↗

32 citations

Nani Solihati & Herri Mulyono (2017)

Two teacher educators share their honest reflections on combining face-to-face classroom instruction with virtual activities using Google Classroom in their language teacher training programme. Their experiences reveal both the benefits and challenges of hybrid instruction, providing practical insights into what works and what doesn't when blending digital and traditional teaching methods. This research is especially valuable for teacher educators and professional development coordinators who are considering how to effectively integrate technology into adult learning environments while maintaining meaningful human interaction.

David Kolb's experiential learning cycle is one of the most widely used models in education and training. The cycle proposes that effective learning involves four stages: having a concrete experience, reflecting on that experience, forming abstract concepts, and actively experimenting with new ideas. While the associated learning styles have been criticised, the cycle itself provides a useful framework for designing learning experiences that move beyond passive reception to active engagement with material.

The idea is simple but powerful: learners don't just absorb information, they make sense of it by doing, reflecting, thinking, and applying. Kolb's cycle captures this process, helping educators understand how students engage with content, reflect on their understanding, form concepts through cognitive development, and test new ideas in real contexts and social learning theory.

In an era where evidence-informed teaching is reshaping educational practise, Kolb's work offers a grounded framework for designing learning that is active, reflective, and deeply connected to real-world experiences. Whether you're working in early years, secondary, or higher education, understanding how experience becomes learning is vital for improving student outcomes.

Experiential learning is no longer confined to internships or vocational training. With the rise of project-based learning, flipped classrooms, and real-world simulation strong>, Kolb's cycle offers a valuable lens for designing meaningful, student-centred experiences that go beyond rote learning. For an immersive approach to this topic, explore Mantle of the Expert, a drama-based inquiry method.

By understanding Kolb's framework, teachers can create more dynamic and responsive learning environments, ones that help students engage more deeply, think more critically, and apply knowledge with confidence.

First published in 1984, Kolb's learning styles are widely used as one of the most renowned learning styles theories. Kolb's theory focuses on the learner's personal development and perspective. Unlike the conventional, didactic method, the learner is responsible to guide his learning process in experiential learning. Experiential learning is a great way to learn because it allows students to apply knowledge in real life situations. Experiential learning encourages active participation, critical thinking, creativity, problem solving, collaboration, and communication skills.

Conventional, didactic methods include lectures, textbooks, and homework assignments. These methods teach facts and concepts, but not necessarily how to apply them in real world situations.

While these two types of teaching styles work well for different purposes, there is no denying that experiential learning is superior when it comes to helping students retain information.

When teaching students, we often use Kolb's Learning Cycle to help them understand the importance of experiential learning. The following model helps illustrate this process:

1. Orientation, Students become familiar with the subject matter through experience (real world) and reflection.

2. Cognitive Processing, Students actively engage in the material through hands-on activities.

3. Retrieval, Students recall the content through memory and repetition.

4. Consolidation, Students integrate the new information into long term memory.

5. Motivation & Evaluation, Students evaluate whether the activity was worthwhile.

6. Integration, Students synthesize the new information into existing knowledge.

7. Application, Students apply the new information to solve problems.

8. Exploration, Students continue to explore the topic further.

If you're looking for ways to improve your online presence, consider adding some experiential learning to your curriculum.

Here is a quick overview of the 4-stages of the Kolb learning styles:

Incorporating Kolb's Learning Cycle into your teaching can transform your classroom into a dynamic, experiential learning centre. Here are some practical strategies to help you implement each stage of the cycle effectively:

By intentionally designing learning experiences that encompass all four stages of Kolb's Learning Cycle, you can create a more engaging, effective, and memorable learning environment for your students. Remember, the goal is to move students beyond passive reception of information to active engagement, reflection, and application.

While Kolb's Learning Cycle provides a valuable framework, implementing it effectively can present some challenges. Here are a few common hurdles and strategies for overcoming them:

Kolb's Learning Cycle offers a powerful framework for designing learning experiences that are deeply engaging, meaningful, and relevant to students' lives. By understanding the four stages of the cycle, concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation, educators can create dynamic learning environments that creates critical thinking, problem-solving, and a lifelong love of learning.

By moving beyond traditional didactic methods and embracing experiential learning, teachers can helps students to become active participants in their own education. This not only enhances their understanding of the subject matter but also equips them with the skills and dispositions needed to succeed in an ever-changing world. Kolb's cycle isn't just a theory; it's a practical guide to creating learning that sticks.

Understanding how Kolb's cycle works in practise transforms it from abstract theory into a powerful teaching tool. Consider a Year 7 science lesson on plant growth. Rather than starting with textbook definitions, students plant seeds in different conditions (concrete experience). They observe and record changes over two weeks, discussing patterns with partners (reflective observation). From their observations, they develop hypotheses about what plants need to thrive (abstract conceptualisation). Finally, they design new experiments to test their theories, perhaps investigating whether music affects growth (active experimentation).

In primary mathematics, the cycle naturally fits hands-on learning. When teaching fractions, pupils might share pizza slices equally among groups (concrete experience), then discuss what they notice about the portions (reflective observation). They work out the mathematical relationships between parts and wholes (abstract conceptualisation), before solving real problems about sharing resources fairly (active experimentation). This approach grounds abstract concepts in tangible experiences that pupils remember.

The cycle proves equally valuable in secondary English. Students might perform scenes from Shakespeare (concrete experience), then write reflective journals about character motivations (reflective observation). Through group analysis, they identify themes and literary techniques (abstract conceptualisation), before creating modern adaptations that demonstrate their understanding (active experimentation). This progression moves students from surface-level reading to deep textual analysis.

What makes these examples effective is their recognition that learning isn't linear. A history teacher might begin with primary source analysis (starting at reflective observation) or launch straight into role-play debates (beginning with active experimentation). The key is ensuring students complete the full cycle, transforming isolated activities into connected learning experiences that build lasting understanding.

David Kolb, an American educational theorist born in 1939, revolutionised how we think about learning by challenging the traditional lecture-and-memorise approach. Working as a professor at Case Western Reserve University, Kolb drew inspiration from earlier educational pioneers like John Dewey, Jean Piaget, and Kurt Lewin to develop his experiential learning theory in the 1970s.

Kolb's breakthrough came from observing that students retained far more when they actively engaged with material rather than passively receiving it. His doctoral work at Harvard, combined with his experience in organisational behaviour, led him to recognise that effective learning mirrors how we naturally acquire skills outside the classroom: through experience, reflection, conceptualisation, and experimentation.

For teachers, understanding Kolb's background reveals why his cycle works so well in practise. As someone who studied both psychology and social work, Kolb understood that learning isn't just cognitive; it involves emotions, social interactions, and physical experiences. This explains why a Year 7 science student might grasp photosynthesis better after growing plants, observing changes, theorising about causes, and testing different light conditions, rather than simply reading textbook definitions.

Kolb's research with adult learners in professional settings also offers valuable insights for classroom teachers. He discovered that people enter the learning cycle at different points based on their preferences and prior experiences. This finding suggests practical strategies: when teaching fractions, some pupils benefit from starting with concrete manipulatives (concrete experience), whilst others prefer beginning with the abstract concept before moving to hands-on activities. Recognising these entry points helps teachers differentiate instruction more effectively, ensuring all students complete the full learning cycle regardless of where they begin.

Whilst Kolb's learning cycle describes how learning occurs, his Learning Styles Inventory (LSI) suggests that individuals have preferences for different stages of the cycle. According to Kolb, these preferences shape four distinct learning styles: Diverging (feeling and watching), Assimilating (watching and thinking), Converging (thinking and doing), and Accommodating (doing and feeling).

It's crucial to understand that modern research has largely discredited the notion that teaching to specific learning styles improves outcomes. However, recognising that students may have different entry points into the learning cycle remains valuable for classroom practise. A student with strong reflective tendencies might naturally begin with observation, whilst another might prefer jumping straight into hands-on experimentation.

Rather than labelling students or restricting activities, use this knowledge to ensure your lessons provide multiple access points. For instance, when teaching fraction multiplication, you might simultaneously offer manipulatives for those who prefer concrete experience, worked examples for those who favour abstract conceptualisation, and reflection prompts for observers. This isn't about matching teaching to mythical fixed styles; it's about providing rich, varied experiences that allow all students to engage with the full cycle.

Consider using learning journals where students identify which stage of the cycle feels most natural to them in different subjects. A Year 8 student might discover they prefer starting with experimentation in science but need concrete examples first in languages. This metacognitive awareness helps students recognise when they need to push themselves through less comfortable stages, building more complete understanding. The goal isn't to cater to preferences but to help students recognise and work through all four stages, regardless of their starting point.

Transforming Kolb's theoretical framework into classroom practise requires thoughtful planning and a willingness to reshape traditional lesson structures. The key lies in creating opportunities for students to move through all four stages, rather than jumping straight from instruction to assessment.

In primary science, for example, begin with hands-on experiments (concrete experience) before introducing scientific concepts. When teaching plant growth, students might first observe seeds sprouting over several days, documenting changes in a journal. The reflective observation stage follows naturally as children discuss what they noticed, comparing observations with peers. Only then do you introduce abstract concepts like photosynthesis, connecting theory to what students have already seen. Finally, students apply this understanding by designing their own growing conditions, testing variables like light and water.

Secondary history teachers can structure units around historical inquiries that mirror Kolb's cycle. Start with primary sources; letters, photographs, or artefacts that students can examine directly. Rather than immediately explaining historical context, allow time for students to reflect on what these sources reveal and what questions they raise. Guide them towards forming hypotheses about the period before introducing historical interpretations. The cycle completes when students create their own historical arguments using evidence, actively experimenting with the historian's craft.

Professional development sessions benefit from the same approach. Instead of lecture-heavy INSET days, begin with teachers trying new techniques in micro-teaching scenarios. Build in structured reflection time where colleagues share observations without immediate judgement. Connect these experiences to educational research and theory, then provide supported opportunities for teachers to adapt and test strategies in their own classrooms. This approach transforms CPD from passive listening into active professional learning that changes classroom practise.

Kolb's learning cycle comprises four distinct stages that learners progress through, either sequentially or by entering at any point depending on their preferred learning style. Each stage serves a unique purpose in the learning process, and effective educators deliberately incorporate activities that address all four stages to maximise student engagement and understanding. The cycle begins with Concrete Experience, where learners encounter new situations or reframe existing experiences, followed by Reflective Observation, where they step back to consider what occurred from multiple perspectives.

Concrete Experience forms the foundation of the learning cycle, representing the "doing" phase where students actively participate in an activity or encounter new material firsthand. In a Year 7 science lesson exploring density, for example, students might physically handle objects of different weights and sizes, dropping them into water tanks to observe which items float or sink. This hands-on engagement provides the raw material for learning, creating vivid memories and emotional connections that enhance retention. Teachers can facilitate concrete experiences through practical experiments, role-playing exercises, field trips, or case study analyses that immerse students in real-world scenarios.

The Reflective Observation stage encourages learners to step back from their immediate experience and consider what they observed, felt, and noticed. Following the density experiment, students might work in pairs to discuss their observations, noting patterns in which materials floated versus those that sank. This stage is crucial for processing experiences before jumping to conclusions. Teachers can support reflective observation through structured discussion questions, learning journals, peer interviews, or guided observation sheets. Research by Gibbs (1988) emphasises that reflection without structure often lacks depth, making teacher guidance essential during this contemplative phase.

Abstract Conceptualisation represents the theoretical stage where learners connect their experiences and reflections to broader principles, theories, or models. Students examining their density observations might now learn the scientific principle that objects float when their density is less than water's density, understanding the mathematical relationship between mass, volume, and buoyancy. This stage transforms concrete experiences into generalisable knowledge. Teachers facilitate abstract conceptualisation through mini-lectures, research assignments, concept mapping, or guided reading that helps students link their experiences to established theories and frameworks.

Active Experimentation completes the cycle as learners apply their newfound understanding to new situations, testing theories and hypotheses in different contexts. Students who grasp density principles might predict whether various mystery objects will float before testing them, or design boats using different materials to explore practical applications. This stage builds confidence and deepens understanding through purposeful practise. Teachers can create opportunities for active experimentation through problem-solving challenges, design projects, simulations, or real-world applications that allow students to test their learning.

Effective implementation of Kolb's cycle requires teachers to consciously plan activities for each stage while recognising that different students may naturally gravitate towards certain stages based on their learning preferences. A well-structured lesson might begin with concrete experience, allow time for reflection, introduce relevant theory, and conclude with opportunities for experimentation. This cyclical approach ensures comprehensive learning that accommodates diverse learning styles whilst building both practical skills and theoretical understanding across all curriculum areas.

Assessment should match each stage: observe student engagement during concrete experiences, use reflective journals or discussion for reflective observation, check conceptual understanding through mind maps or explanations, and evaluate practical application through real-world tasks. This varied approach provides a comprehensive picture of learning progress across all four stages.

Try think-pair-share discussions, exit tickets with reflection questions, or simple learning logs where students write three things they noticed during the experience. Video diaries, peer feedback sessions, or guided questioning can also help students process their concrete experiences effectively.

There's no fixed timing as it depends on the complexity of the topic and age of students. A single lesson might focus on one or two stages, whilst a complete cycle could span several lessons or even weeks for complex topics. The key is ensuring all stages are eventually covered rather than rushing through each one.

Yes, online platforms can support all four stages effectively. Virtual simulations provide concrete experiences, online discussion boards facilitate reflection, collaborative documents help build abstract concepts, and digital projects enable active experimentation. The key is adapting activities to the digital environment whilst maintaining the cycle's interactive nature.

Whilst Kolb's cycle works across all subjects, it's particularly effective in science (experiments and observations), humanities (role-play and case studies), and practical subjects like design technology. However, even traditionally theoretical subjects like mathematics can benefit from concrete experiences such as real-world problem-solving scenarios.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

The Effectiveness of the 5E Learning Cycle Model in Students' Mathematics Engagement Learning View study ↗

M. Ghunaimat & E. Alawneh (2025)

This recent study demonstrates that the 5E Learning Cycle Model (Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, Evaluate) significantly increases student engagement in mathematics across behavioural, emotional, and cognitive dimensions compared to traditional teaching methods. For math teachers struggling with student motivation, this research provides evidence that structuring lessons around these five phases can help students become more actively involved in their learning. The findings suggest that moving beyond lecture-based instruction to this cyclical approach creates more meaningful mathematical experiences for students.

Student-Centred Active Learning Improves Performance in Solving Higher-Level Cognitive Questions in Health Sciences Education View study ↗

11 citations

N. Martín-Alguacil & L. Avedillo (2024)

Researchers found that when health science students participated in student-centred active learning environments, particularly flipped classrooms, they performed significantly better on complex thinking tasks that required analysis and application rather than just memorization. This study is particularly valuable for educators because it shows that active learning strategies don't just improve engagement, they actually help students develop the critical thinking skills needed for real-world problem solving. The research provides concrete evidence that shifting from teacher-centred to student-centred approaches produces measurable improvements in higher-order thinking abilities.

The Effectiveness of Teaching Derivatives in Vietnamese High Schools Using APOS Theory and ACE Learning Cycle View study ↗

12 citations

N. Thi et al. (2023)

This study successfully combined APOS theory (which focuses on how students build mathematical understanding through Actions, Processes, Objects, and Schemas) with the ACE learning cycle (Activities, Classroom discussion, and Exercises) to teach calculus derivatives more effectively. Vietnamese high school students showed improved conceptual understanding and mathematical competency when teachers used this structured approach rather than traditional methods. The research offers math teachers a practical framework for helping students grasp abstract mathematical concepts by building understanding step by step through hands-on activities and guided discussion.

Interactive Peer Instruction Method Applied to Classroom Environments Considering a Learning Engineering Approach to Innovate the Teaching-Learning Process View study ↗

20 citations

Jessica Rivadeneira & Esteban Inga (2023)

This research explores how peer instruction, a method that uses strategic questioning and student discussion to promote active learning, can transform classrooms where traditional lectures have left students passive and unmotivated. The study shows that when teachers incorporate interactive question and answer dynamics that encourage students to learn from each other, participation and engagement increase dramatically. For educators looking to move away from one-way instruction, this research provides a roadmap for implementing peer-based learning strategies that make students active contributors to their own education.

A Hybrid Classroom Instruction in Second Language Teacher Education (SLTE): A Critical Reflection of Teacher Educators View study ↗

32 citations

Nani Solihati & Herri Mulyono (2017)

Two teacher educators share their honest reflections on combining face-to-face classroom instruction with virtual activities using Google Classroom in their language teacher training programme. Their experiences reveal both the benefits and challenges of hybrid instruction, providing practical insights into what works and what doesn't when blending digital and traditional teaching methods. This research is especially valuable for teacher educators and professional development coordinators who are considering how to effectively integrate technology into adult learning environments while maintaining meaningful human interaction.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/kolbs-learning-cycle#article","headline":"Kolb's Learning Cycle: The Four Stages of Experiential Learning","description":"Master Kolb's experiential learning cycle: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation stages.","datePublished":"2022-09-09T15:53:19.099Z","dateModified":"2026-02-06T11:06:19.823Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/kolbs-learning-cycle"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a5da2e731428e5e09fd4c_696a5da0b66ed01ff02f65d6_kolbs-learning-cycle-infographic.webp","wordCount":4427},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/kolbs-learning-cycle#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Kolb's Learning Cycle: The Four Stages of Experiential Learning","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/kolbs-learning-cycle"}]}]}