VR in Education

Discover the advantages of using VR applications in education! This post explores how virtual reality can enhance learning experiences and engage students.

Discover the advantages of using VR applications in education! This post explores how virtual reality can enhance learning experiences and engage students.

Virtual Reality (VR) is a digital technology using visual, auditory and other sensory stimuli provided through a head-mounted display, to create the illusion that a learner is present in a different environment and context. The benefits of virtual reality in education have been widely documented and This guide covers how this technology can be used to develop practical knowledge in the classroom. VR education is a growing field, and its applications within tertiary, secondary and primary education are beginning to be understood.

VR in education offers an immersive learning experience that allows students to interact with their environment in a way that was previously impossible. The technology can be used to create simulations of real-world scenarios, allowing students to practice skills in a safe and controlled environment. For example, VR can be used to simulate a science experiment or a historical event, allowing students to experience it firsthand. This immersive learning experience can lead to increased engagement and retention of information, as students are more likely to remember what they have experienced rather than what they have simply read or heard about.

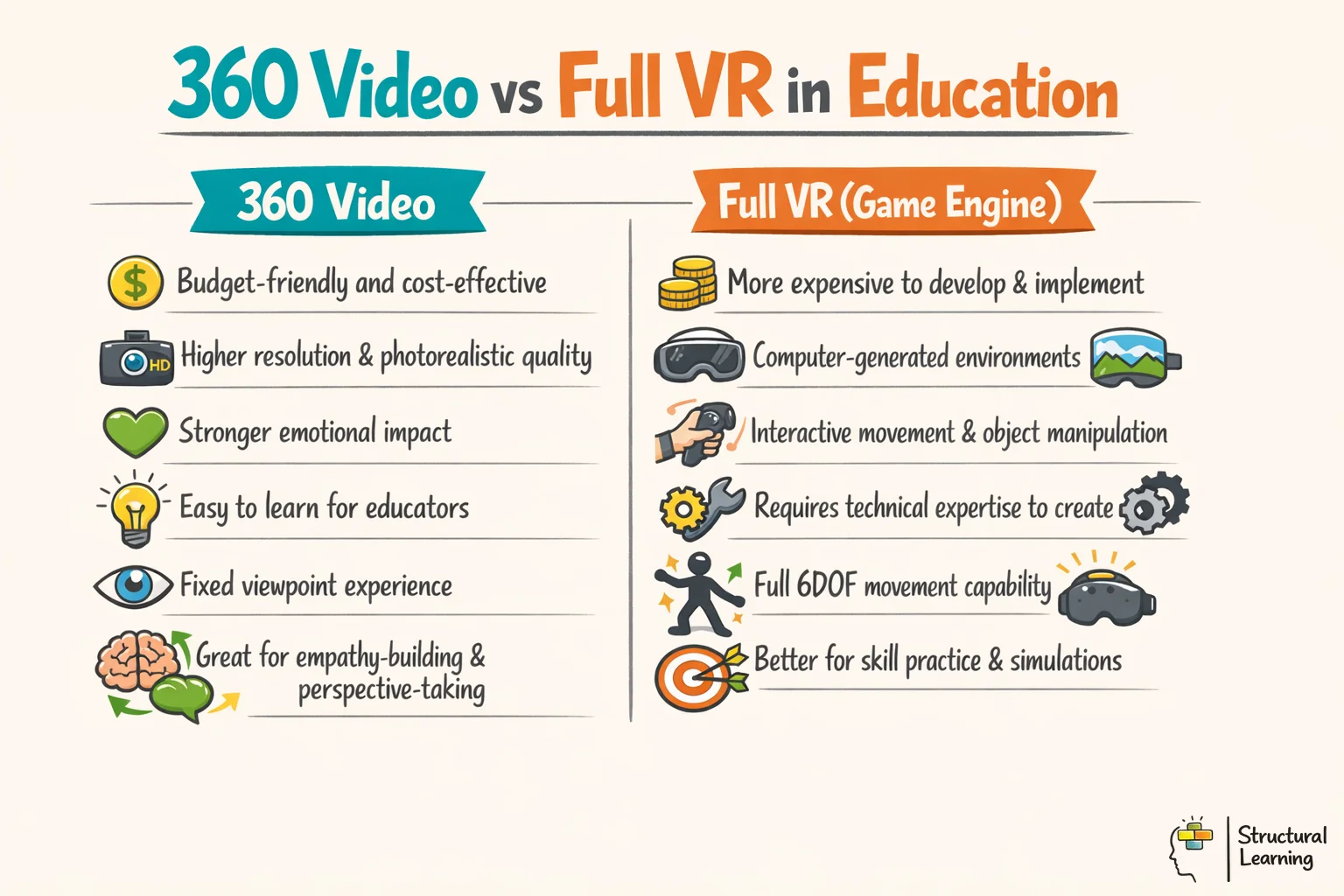

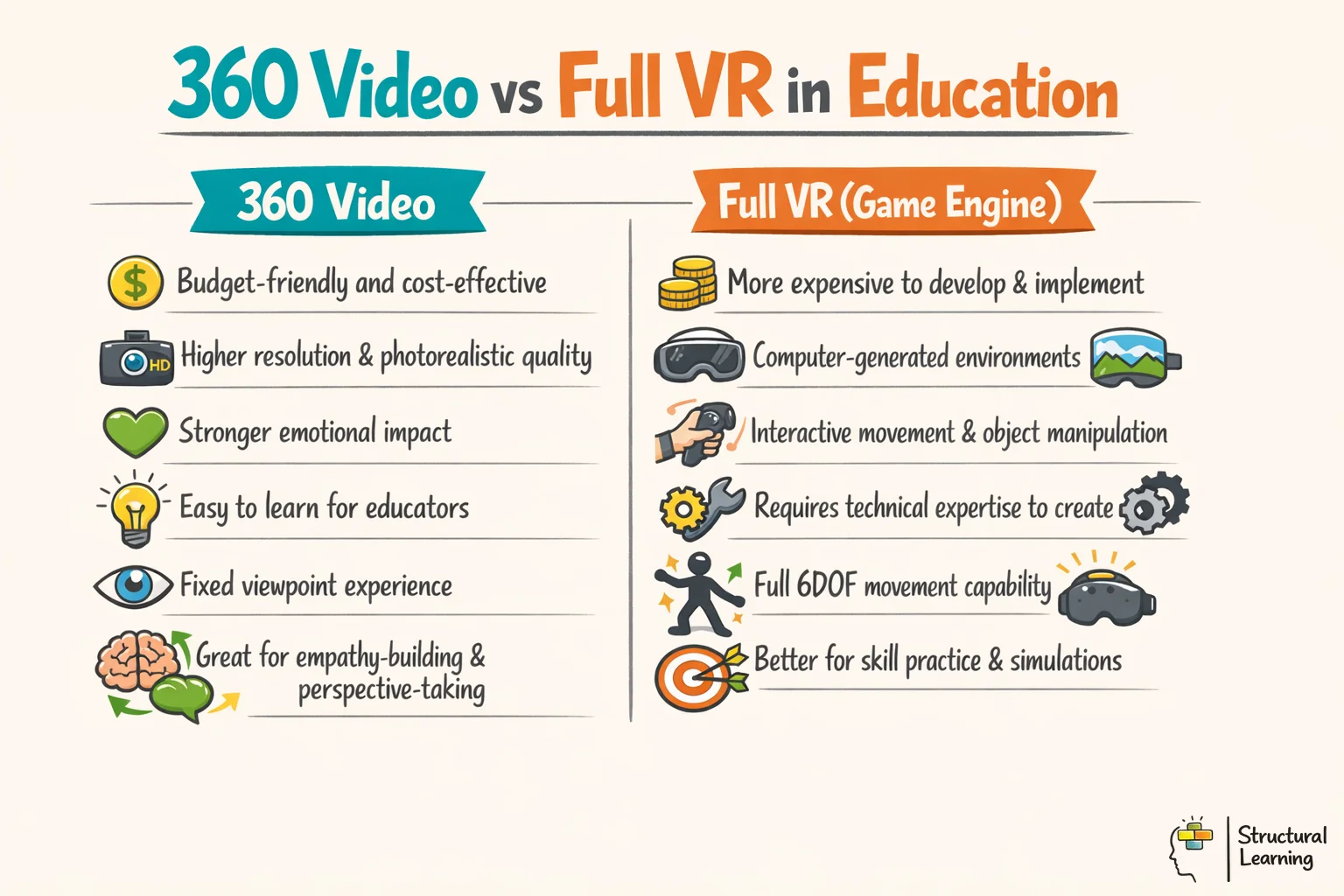

These virtual environments are created in two ways primarily, either the virtual reality environment is artificially created inside software (i.e. A game engine such as Unity and Unreal) allowing users to move around and interact in a computer-generated scenario creating an immersive experience. Alternatively, a more cost-effective alternative is to use 360 video where a camera uses multiple lenses to capture video in all directions, stitching the multiple video feeds together to create a sphere allowing the learner to stand in the position of the camera in the scene and look around from a fixed point. When using 360 video, a new environment can be captured or a scenario can be acted out to convey a learning experience to a viewer.

VR in education increases student engagement and retention by allowing learners to experience content firsthand rather than just reading about it. The technology creates safe, controlled environments where students can practice dangerous scenarios and build real-world skills without risk. Short 3-4 minute VR sessions deliver maximum learning impact while avoiding health risks associated with longer exposure.

360 video can create a deep sense of presence and immersion in a situation, and this has particular applications for education. Good 360 video cameras offer high resolution resulting in a higher sense of realism in comparison to game engine generated environments.

This medium is ideal for transferring emotion and allowing a learner to feel the emotion in a scenario as well as develop empathy by taking the perspective of someone different to themselves. 360 video allows for the learner to be placed in a new simulated environment that may be inaccessible, unsafe or expensive to experience in real-life, allowing for contextual learning and visualision of concepts and context. For educators and creators of educational content, 360 video is relatively easy to learn and a nice entry point into VR and immersive technology.

Opportunities for students using VR in education are endless. With 360 videos, students can explore places and situations that they may never have the chance to experience in real life. For example, students can visit historical sites, travel to different parts of the world, or even experience the effects of climate change. This type of immersive learning allows students to engage with their subjects in a more meaningful and memorable way. Additionally, VR in education can help students develop skills such as Critical thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making, all while having fun and experiencing the benefits of this exciting technology. As VR continues to advance, the possibilities for educational opportunities will only continue to grow.

Another benefit of using VR in education is the development of creative Thinking skills. With VR, students can explore and create their own virtual worlds, allowing them to Think outside the box and come up with unique solutions to problems. This type of learning encourages creativity and innovation, which can be applied to other areas of their lives. Additionally, VR can help students visualize abstract concepts and ideas, making it easier for them to understand and apply their knowledge. The technology also supports different learning needs, making education more Inclusive for diverse learners. By incorporating VR into education, students can develop a range of skills that will benefit them in their academic and professional careers.

The most effective VR applications include empathy-building exercises that place students in others' perspectives and simulation-based learning for dangerous scenarios like science experiments or historical events. 360-degree video content often delivers stronger emotional impact than expensive game engines for most classroom purposes. VR works best for experiential learning where students need to practice procedural skills in realistic but controlled environments.

As an educational technology, 360 video is great for placing learners in a different environment outside of the classroom allowing learners to experience a context and visualize concepts and situations in an immersive way. Perhaps most importantly, 360 video allows the learner to experience a situation or environment in the first person, allowing for delivery of emotion and encouraging agency as well as personal, real and active learning.

VR has been used for induction to pre-experience a new workplace as well as in diversity training to take a perspective of the other. In addition, 360 video is great for learning about cultural nuances through intercultural encounters as well as providing authentic cultural experiences and virtual tours of historic sites. These experiences can help develop emotional intelligence through perspective-taking activities. 360 video is also good for experiencing dangerous or risky situations that can be difficult to experience in reality, helping students build resilience when facing challenging scenarios.

As a result it is a natural fit for safety training as well as provide demonstrations and training in a simulated environment.

While VR in education offers many benefits, there are also challenges to consider. One challenge is the cost of the technology. VR headsets and software can be expensive, which may make it difficult for some schools to adopt. Another challenge is the potential for motion sickness or eye strain, which can occur with prolonged use of VR. Implement shorter VR experiences (around 3-4 minutes) to maximise learning impact without health risks.

Additionally, educators need to be trained on how to effectively use VR in the classroom. This includes understanding how to select appropriate VR experiences, how to integrate VR into the curriculum, and how to manage the technology. It also means being aware of the potential distractions and finding effective ways to overcome them. Ensuring accessibility for all learners is also crucial, as some students may require accommodations to fully participate in VR activities.

Virtual reality is transforming education by providing immersive, interactive learning experiences. From practicing skills in safe, controlled environments to developing empathy through perspective-taking, VR offers unparalleled opportunities for student engagement and knowledge retention. While challenges such as cost and potential health concerns exist, the benefits of VR in education are undeniable.

As VR technology continues to evolve, its applications in education will only expand. By embracing VR, educators can create dynamic, engaging learning experiences that prepare students for success in a rapidly changing world. The key is to focus on shorter, targeted VR sessions that deliver maximum learning impact, coupled with effective integration into the curriculum and appropriate training for educators.

Ultimately, VR in education is not just about using new technology; it's about creating meaningful learning experiences that helps students to explore, discover, and connect with the world around them. By carefully considering the benefits and challenges, educators can harness the power of VR to create a truly transformative learning environment.

Virtual Reality (VR) is a digital technology using visual, auditory and other sensory stimuli provided through a head-mounted display, to create the illusion that a learner is present in a different environment and context. The benefits of virtual reality in education have been widely documented and This guide covers how this technology can be used to develop practical knowledge in the classroom. VR education is a growing field, and its applications within tertiary, secondary and primary education are beginning to be understood.

VR in education offers an immersive learning experience that allows students to interact with their environment in a way that was previously impossible. The technology can be used to create simulations of real-world scenarios, allowing students to practice skills in a safe and controlled environment. For example, VR can be used to simulate a science experiment or a historical event, allowing students to experience it firsthand. This immersive learning experience can lead to increased engagement and retention of information, as students are more likely to remember what they have experienced rather than what they have simply read or heard about.

These virtual environments are created in two ways primarily, either the virtual reality environment is artificially created inside software (i.e. A game engine such as Unity and Unreal) allowing users to move around and interact in a computer-generated scenario creating an immersive experience. Alternatively, a more cost-effective alternative is to use 360 video where a camera uses multiple lenses to capture video in all directions, stitching the multiple video feeds together to create a sphere allowing the learner to stand in the position of the camera in the scene and look around from a fixed point. When using 360 video, a new environment can be captured or a scenario can be acted out to convey a learning experience to a viewer.

VR in education increases student engagement and retention by allowing learners to experience content firsthand rather than just reading about it. The technology creates safe, controlled environments where students can practice dangerous scenarios and build real-world skills without risk. Short 3-4 minute VR sessions deliver maximum learning impact while avoiding health risks associated with longer exposure.

360 video can create a deep sense of presence and immersion in a situation, and this has particular applications for education. Good 360 video cameras offer high resolution resulting in a higher sense of realism in comparison to game engine generated environments.

This medium is ideal for transferring emotion and allowing a learner to feel the emotion in a scenario as well as develop empathy by taking the perspective of someone different to themselves. 360 video allows for the learner to be placed in a new simulated environment that may be inaccessible, unsafe or expensive to experience in real-life, allowing for contextual learning and visualision of concepts and context. For educators and creators of educational content, 360 video is relatively easy to learn and a nice entry point into VR and immersive technology.

Opportunities for students using VR in education are endless. With 360 videos, students can explore places and situations that they may never have the chance to experience in real life. For example, students can visit historical sites, travel to different parts of the world, or even experience the effects of climate change. This type of immersive learning allows students to engage with their subjects in a more meaningful and memorable way. Additionally, VR in education can help students develop skills such as Critical thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making, all while having fun and experiencing the benefits of this exciting technology. As VR continues to advance, the possibilities for educational opportunities will only continue to grow.

Another benefit of using VR in education is the development of creative Thinking skills. With VR, students can explore and create their own virtual worlds, allowing them to Think outside the box and come up with unique solutions to problems. This type of learning encourages creativity and innovation, which can be applied to other areas of their lives. Additionally, VR can help students visualize abstract concepts and ideas, making it easier for them to understand and apply their knowledge. The technology also supports different learning needs, making education more Inclusive for diverse learners. By incorporating VR into education, students can develop a range of skills that will benefit them in their academic and professional careers.

The most effective VR applications include empathy-building exercises that place students in others' perspectives and simulation-based learning for dangerous scenarios like science experiments or historical events. 360-degree video content often delivers stronger emotional impact than expensive game engines for most classroom purposes. VR works best for experiential learning where students need to practice procedural skills in realistic but controlled environments.

As an educational technology, 360 video is great for placing learners in a different environment outside of the classroom allowing learners to experience a context and visualize concepts and situations in an immersive way. Perhaps most importantly, 360 video allows the learner to experience a situation or environment in the first person, allowing for delivery of emotion and encouraging agency as well as personal, real and active learning.

VR has been used for induction to pre-experience a new workplace as well as in diversity training to take a perspective of the other. In addition, 360 video is great for learning about cultural nuances through intercultural encounters as well as providing authentic cultural experiences and virtual tours of historic sites. These experiences can help develop emotional intelligence through perspective-taking activities. 360 video is also good for experiencing dangerous or risky situations that can be difficult to experience in reality, helping students build resilience when facing challenging scenarios.

As a result it is a natural fit for safety training as well as provide demonstrations and training in a simulated environment.

While VR in education offers many benefits, there are also challenges to consider. One challenge is the cost of the technology. VR headsets and software can be expensive, which may make it difficult for some schools to adopt. Another challenge is the potential for motion sickness or eye strain, which can occur with prolonged use of VR. Implement shorter VR experiences (around 3-4 minutes) to maximise learning impact without health risks.

Additionally, educators need to be trained on how to effectively use VR in the classroom. This includes understanding how to select appropriate VR experiences, how to integrate VR into the curriculum, and how to manage the technology. It also means being aware of the potential distractions and finding effective ways to overcome them. Ensuring accessibility for all learners is also crucial, as some students may require accommodations to fully participate in VR activities.

Virtual reality is transforming education by providing immersive, interactive learning experiences. From practicing skills in safe, controlled environments to developing empathy through perspective-taking, VR offers unparalleled opportunities for student engagement and knowledge retention. While challenges such as cost and potential health concerns exist, the benefits of VR in education are undeniable.

As VR technology continues to evolve, its applications in education will only expand. By embracing VR, educators can create dynamic, engaging learning experiences that prepare students for success in a rapidly changing world. The key is to focus on shorter, targeted VR sessions that deliver maximum learning impact, coupled with effective integration into the curriculum and appropriate training for educators.

Ultimately, VR in education is not just about using new technology; it's about creating meaningful learning experiences that helps students to explore, discover, and connect with the world around them. By carefully considering the benefits and challenges, educators can harness the power of VR to create a truly transformative learning environment.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/vr-education#article","headline":"VR in Education","description":"Discover the advantages of using VR applications in education! This post explores how virtual reality can enhance learning experiences and engage students.","datePublished":"2022-08-24T11:15:42.388Z","dateModified":"2026-01-30T12:40:35.998Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/vr-education"},"wordCount":1551},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/vr-education#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"VR in Education","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/vr-education"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"Understanding VR: What is Virtual Reality in Education?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Virtual Reality (VR) is a digital technology using visual, auditory and other sensory stimuli provided through a head-mounted display, to create the illusion that a learner is present in a different environment and context. The benefits of virtual reality in education have been widely documented and This guide covers how this technology can be used to develop practical knowledge in the classroom. VR education is a growing field, and its applications within tertiary, secondary and primary educati"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Are the Main Benefits of Using VR in Education?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"VR in education increases student engagement and retention by allowing learners to experience content firsthand rather than just reading about it. The technology creates safe, controlled environments where students can practice dangerous scenarios and build real-world skills without risk. Short 3-4 minute VR sessions deliver maximum learning impact while avoiding health risks associated with longer exposure."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Are the Most Effective Uses of VR in the Classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The most effective VR applications include empathy-building exercises that place students in others' perspectives and simulation-based learning for dangerous scenarios like science experiments or historical events. 360-degree video content often delivers stronger emotional impact than expensive game engines for most classroom purposes. VR works best for experiential learning where students need to practice procedural skills in realistic but controlled environments."}}]}]}