Declarative Memory

Explore the facets of declarative memory, including semantic and episodic types, and their roles in cognitive processing and recall.

Explore the facets of declarative memory, including semantic and episodic types, and their roles in cognitive processing and recall.

| Memory Type | Description | Examples | Teaching Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic Memory | Facts and concepts | Capitals, multiplication tables | Requires repetition and elaboration |

| Episodic Memory | Personal experiences | First day of school, field trips | Enhanced by emotional connections |

| Procedural Memory | Skills and actions | Reading, solving equations | Requires practice to automaticity |

| Explicit Memory | Conscious recall | Definitions, dates | Benefits from retrieval practice |

| Implicit Memory | Unconscious recall | Grammar rules in speech | Develops through exposure |

Declarative memory is the type of memory that allows us to consciously recall facts, experiences, and concepts we can verbally describe. It works by storing information in two main forms: episodic memory for personal experiences and semantic memory for factual knowledge. This memory system relies on the hippocampus to bind different pieces of information together for later conscious retrieval.

| Memory Type | What It Stores | Conscious Recall | Examples in Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Declarative (Explicit) Memory | Facts, events, and knowledge that can be consciously recalled | Yes - requires conscious effort to retrieve | Historical dates, vocabulary definitions, personal experiences |

| Episodic Memory (Type of Declarative) | Personal experiences and specific events in time | Yes - "mental time travel" to remember events | Remembering a school trip, what happened in yesterday's lesson, personal life events |

| Semantic Memory (Type of Declarative) | General knowledge and facts about the world | Yes - but without remembering when/where learned | Knowing London is the capital of England, understanding what photosynthesis is, vocabulary knowledge |

| Procedural (Implicit) Memory | Skills, habits, and how to do things | No - automatic, unconscious performance | Riding a bike, touch-typing, reading fluency, mathematical procedures |

Memory retrieval is influenced not just by the content itself but by the context in which it was learned. The principles of context-dependent learning explain why students sometimes struggle to recall information in unfamiliar testing environments. Understanding this phenomenon helps teachers design learning experiences that either match assessment contexts or deliberately vary contexts to build more flexible memory access through retrieval practice.

Declarative memory, often juxtaposed with procedural memory, is a critical element in our cognitive architecture. Understanding how declarative and working memory systemsinteract is essential for effective teaching, as it, facilitating the retrieva l of experiences, facts, and concepts. This type of memory is integral to our understanding of the world and ourselves, shaping our current perspective and guiding our interactions.

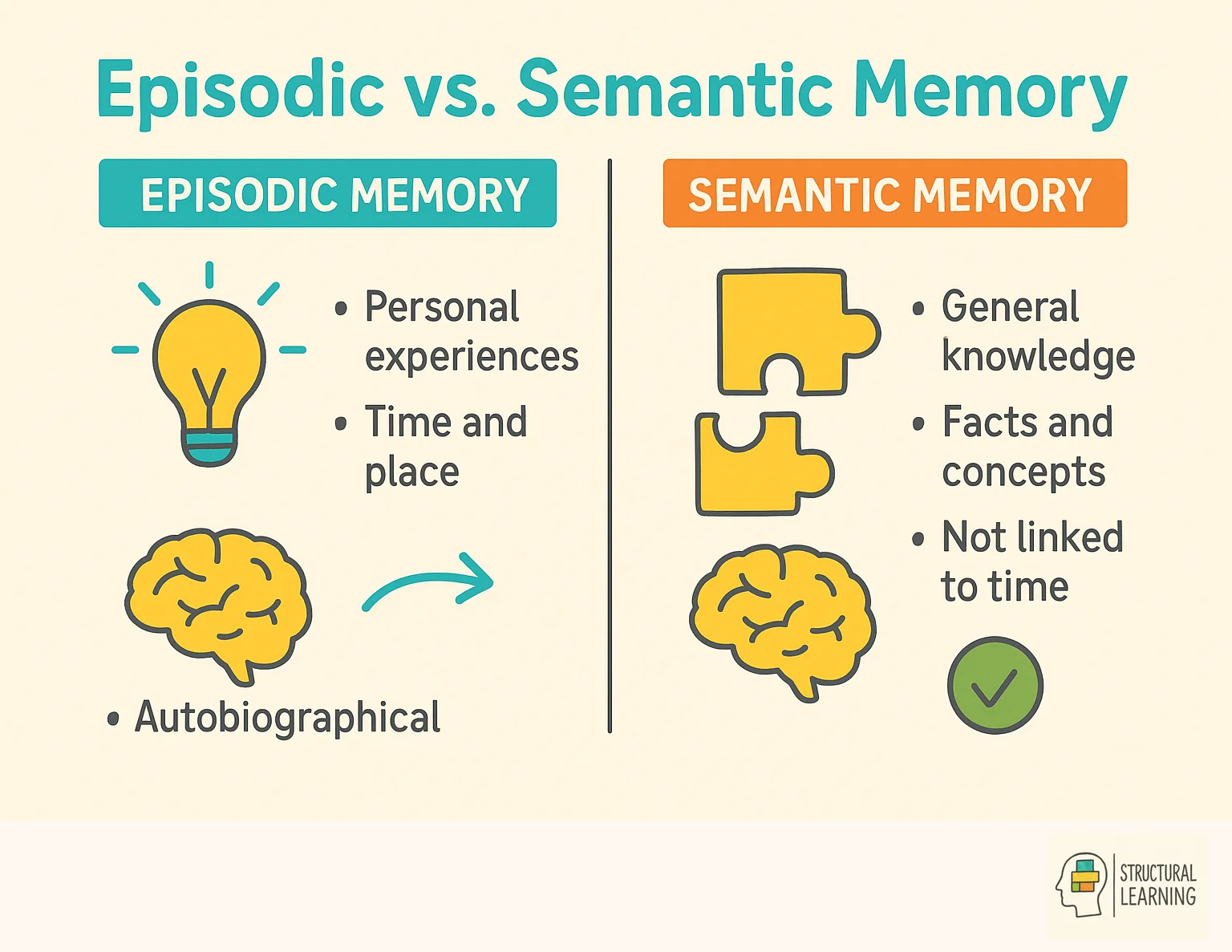

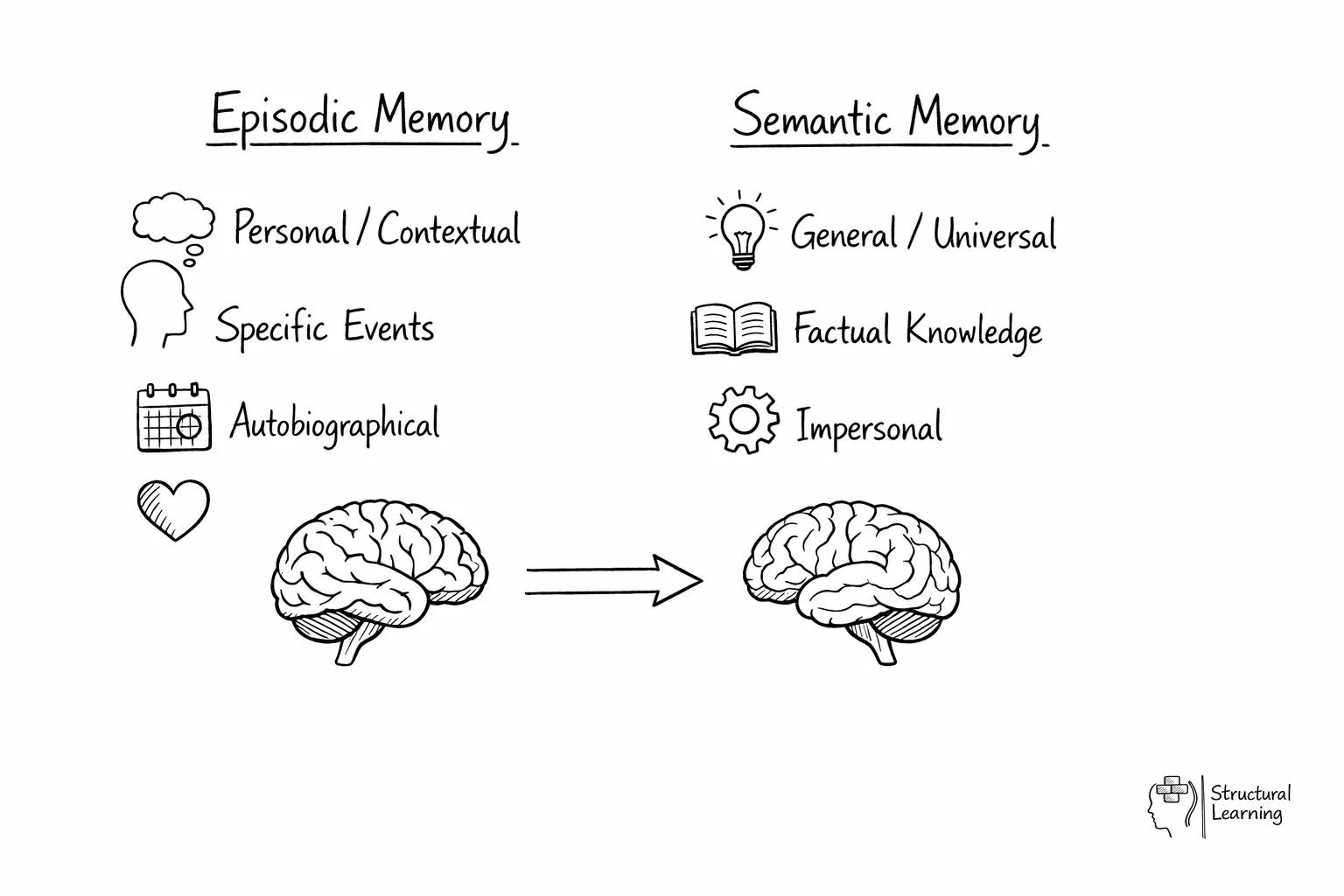

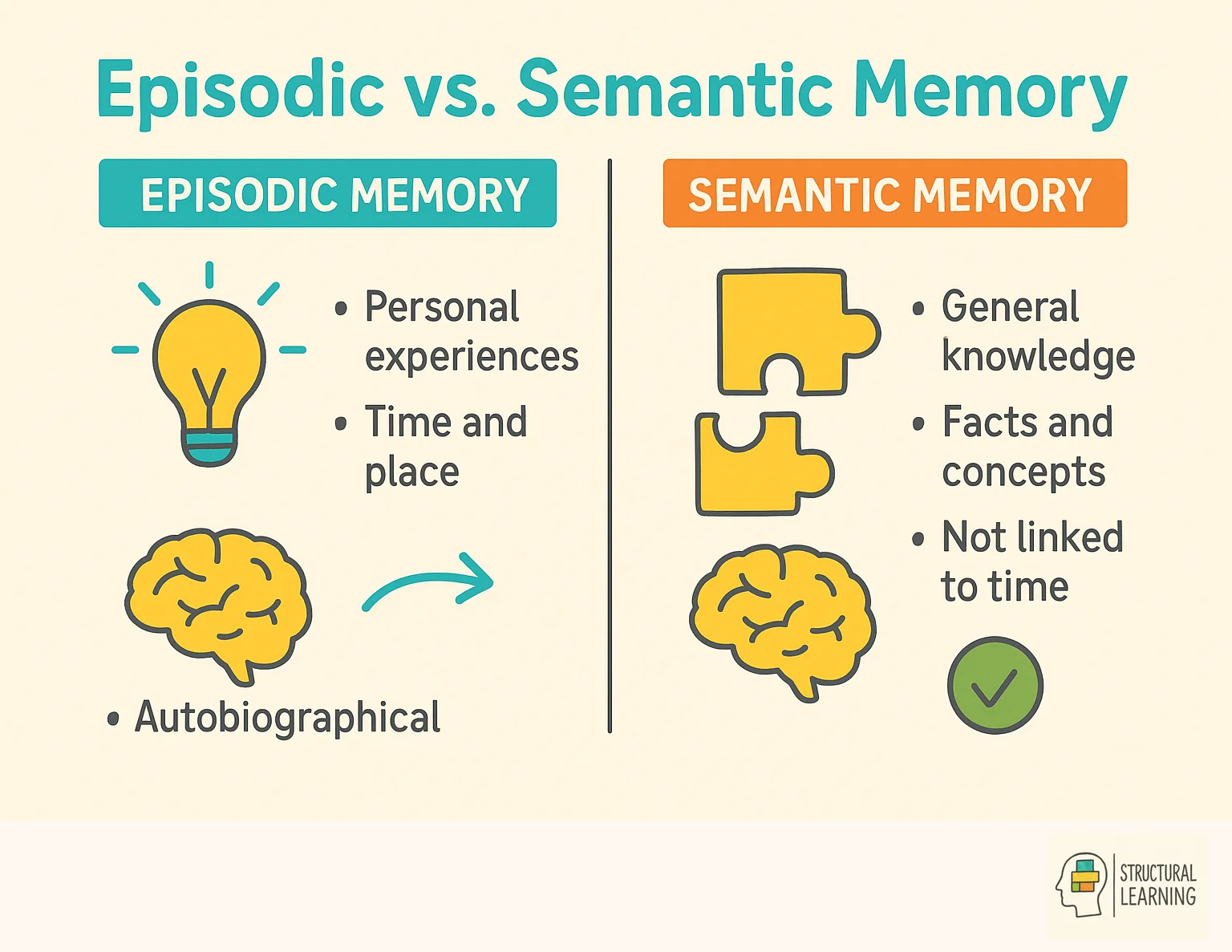

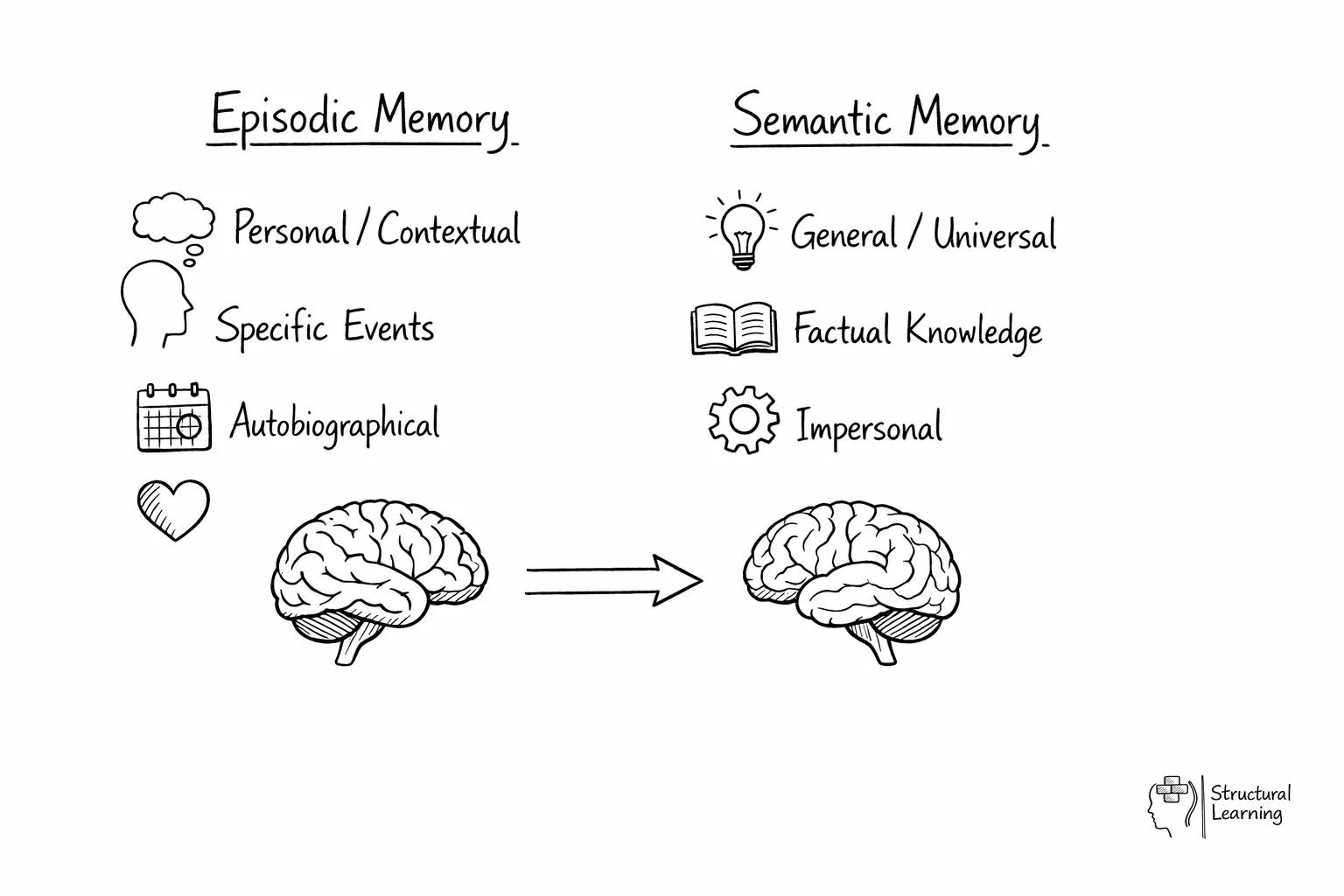

At its core, declarative memory is divided into two subtypes: episodic and semantic memory. Episodic memory is akin to a personal narrative, enabling us to revisit specific events, like the joy of a childhood birthday or the serene ambience of a family holiday.

It's a tapestry of personal experiences, woven with the threads of individual context and subjective interpretation. Semantic memory, in contrast, is the repository of our factual knowledge, the bedrock of our understanding of universal truths and concepts. It's where we store the fact that Paris is the capital of France or the principles of gravity.

These two strands, while under the declarative memory umbrella, differ in their essence. Episodic memory is about reliving unique, personal moments, while semantic memory is about accessing impersonal, general knowledge. They collectively enable us to navigate the complex world, providing a multifaceted framework for critical thinking.

Declarative memory's role extends beyond mere recollection. It involves intricate cognitive functions, engaging areas like the prefrontal and temporal cortex. It plays a part in spatial memory, influencing how we perceive and remember locations and spaces. In the field of speech-sound learning and emotional learning, declarative memory contributes significantly, impacting how we process and retain linguistic and emotional information. Understanding these processes helps teachers develop effective questioning strategies that activate both episodic and semantic knowledge.

In children, the development of declarative-memory skills is crucial. It shapes their learning, allowing them to accumulate and apply knowledge effectively. This is particularly important when considering sen students who may require differentiation strategies to support their memory development. This memory space is not static; it evolves with our experiences and cognitive growth, reflecting our ever-changing understanding of the world. Teachers can support this development through spaced practice and by helping students understand how their own metacognition influences memory formation.

Key Insights:

Declarative memory, thus, is not just a storehouse of past events and facts. It's a dynamic, evolving construct that shapes our perception, learning, and interaction with the world, highlighting the intricate organisation of memory within our cognitive system. Teachers can use techniques like dual coding to strengthen memory formation, while understanding that student attention and motivation play crucial roles in how well declarative memories are formed and retrieved. Without proper reinforcement, information stored in declarative memory follows the forgetting curve, making systematic review essential for long-term retention.

ata-rt-dimensions="854:480">Declarative memory, therefore, is far more than just recalling facts; it's about crafting a coherent and meaningful narrative of the world around us. By understanding its nuances, teachers can create learning experiences that resonate deeply, transforming information into lasting, accessible knowledge for their students.

Here are some practical strategies that teachers can implement to enhance the development and utilisation of declarative memory in their students:

The distinction between semantic and episodic memory is fundamental to understanding how students process and store different types of information. Semantic memory contains our general knowledge about the world - facts, concepts, and meanings that exist independently of when or where we learned them. In contrast, episodic memory stores our personal experiences and specific events, complete with contextual details about time, place, and circumstances. This difference has profound implications for how teachers present information and design learning experiences.

In the classroom, semantic memory encompasses the factual knowledge students need to master across subjects. For example, knowing that the Battle of Hastings occurred in 1066, understanding photosynthesis as the process plants use to convert sunlight into energy, or recognising that Shakespeare wrote Hamlet are all examples of semantic memory. Students can recall these facts without necessarily remembering the specific lesson where they learned them. This type of memory forms the foundation of academic knowledge and is heavily emphasised in many areas of the UK National Curriculum.

Episodic memory, however, captures the rich experiential context of learning. A Year 7 student might have episodic memories of conducting their first science experiment, the excitement of a particular poetry lesson, or the specific moment when a mathematical concept finally 'clicked' during group work. These memories include the content learned and the emotions, sensory details, and social context surrounding the learning experience. Research shows that when episodic and semantic memories are linked, recall becomes more robust and meaningful.

Understanding this distinction helps teachers use both memory systems effectively. While semantic memory is essential for building knowledge, episodic memories can serve as powerful retrieval cues. When students struggle to recall semantic information, teachers can prompt them to remember the specific context in which they learned it: "Remember when we acted out the water cycle in the playground?" This approach helps bridge the gap between experiential learning and factual recall, making abstract concepts more memorable and accessible.

Strengthening declarative memory requires deliberate instructional strategies that align with how the brain naturally processes and consolidates information. Retrieval practice stands as one of the most effective evidence-based approaches. Rather tha n simply re-reading notes or reviewing materials passively, students need regular opportunities to actively recall information from memory. This might involve low-stakes quizzes at the start of lessons, exit tickets requiring students key points, or collaborative recall activities where pupils work together to reconstruct yesterday's learning without looking at their books.

Spaced repetition amplifies the benefits of retrieval practice by strategically timing when information is revisited. Instead of cramming all related content into one intensive session, teachers can distribute learning across multiple lessons with increasing intervals between reviews. For instance, introducing fractions in mathematics, then revisiting the concept after three days, then a week later, then three weeks later. This spacing effect helps transfer information from short-term to long-term memory more effectively than massed practice. Many schools now build this principle into their curriculum planning, ensuring key concepts resurface regularly across terms.

Elaborative rehearsal strengthens declarative memory by encouraging students to connect new information with existing knowledge structures. When teaching about the Roman invasion of Britain, for example, teachers might ask students to compare Roman military tactics with modern warfare they've seen in films, or link Roman road building to contemporary infrastructure projects. This approach activates schema theory principles, where new information is more readily encoded when it can be meaningfully connected to prior knowledge. The process of creating these connections deepens understanding and provides multiple pathways for later retrieval.

Teachers can also enhance declarative memory through dual coding strategies that engage both verbal and visual processing systems. This might involve creating mind maps that combine keywords with images, using graphic organisers to represent relationships between concepts, or encouraging students to draw diagrams while explaining processes aloud. Additionally, varying the context in which information is encountered helps build flexible retrieval pathways. Teaching the same historical concept through role-play, documentary analysis, and written sources ensures students can access the information regardless of how it's later assessed.

Sleep plays a crucial role in memory consolidation, the process by which newly acquired information is stabilised and integrated into long-term memory stores. During sleep, particularly during slow-wave sleep phases, the brain actively rehearses and strengthens the neural connections formed during daytime learning. The hippocampus, which initially holds new declarative memories, communicates with the neocortex to gradually transfer information for permanent storage. This process means that what students learn today becomes more firmly embedded in memory after a good night's sleep, making adequate rest an essential component of effective learning.

Research demonstrates that students who get sufficient sleep show significantly better retention of classroom material compared to their sleep-deprived peers. The consolidation process is particularly important for declarative memory because it helps organise factual information and personal experiences into coherent, retrievable knowledge structures. When students consistently lack adequate sleep, this consolidation process is disrupted, leading to fragmented memory formation and increased forgetting. This has direct implications for academic performance across all subjects, from remembering historical dates to retaining mathematical procedures.

For teachers, understanding sleep's role in memory consolidation can inform both pedagogy and pastoral care. Timing of learning activities becomes important - introducing complex new concepts earlier in the day when students are more alert, and using later lessons for review and application rather than initial acquisition. Teachers can also educate students and parents about healthy sleep hygiene, emphasising that consistent bedtimes and sufficient sleep duration (typically 9-10 hours for secondary school students) directly impact academic success. Some schools now incorporate sleep education into their PSHE curriculum, recognising its fundamental importance for learning.

The implications extend beyond individual study habits to whole-school policies. Early school start times can be particularly problematic for adolescents, whose natural circadian rhythms shift towards later sleep and wake times. Schools that have implemented later start times often report improved attendance, better academic performance, and enhanced student wellbeing. Additionally, teachers can be mindful of homework timing, ensuring that demanding cognitive tasks aren't scheduled immediately before bedtime, as this can interfere with both sleep onset and the natural memory consolidation processes that occur during rest.

Declarative memory is a cornerstone of learning and cognition, enabling us to consciously recall facts, events, and concepts. By understanding its two key components, episodic and semantic memory, educators can tailor their teaching strategies to enhance students' ability to encode, store, and retrieve information effectively. Using techniques like contextual learning, storytelling, and spaced repetition can significantly improve declarative memory skills.

Furthermore, recognising the influence of context, emotion, and sensory input on memory formation allows teachers to create more engaging and memorable learning experiences. By focusing on active recall, linking new information to existing knowledge, and promoting metacognitive awareness, educators can helps students to become more effective and self-regulated learners. Ultimately, a deep understanding of declarative memory not only enriches teaching practices but also cultivates a lifelong love of learning in students.

| Memory Type | Description | Examples | Teaching Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic Memory | Facts and concepts | Capitals, multiplication tables | Requires repetition and elaboration |

| Episodic Memory | Personal experiences | First day of school, field trips | Enhanced by emotional connections |

| Procedural Memory | Skills and actions | Reading, solving equations | Requires practice to automaticity |

| Explicit Memory | Conscious recall | Definitions, dates | Benefits from retrieval practice |

| Implicit Memory | Unconscious recall | Grammar rules in speech | Develops through exposure |

Declarative memory is the type of memory that allows us to consciously recall facts, experiences, and concepts we can verbally describe. It works by storing information in two main forms: episodic memory for personal experiences and semantic memory for factual knowledge. This memory system relies on the hippocampus to bind different pieces of information together for later conscious retrieval.

| Memory Type | What It Stores | Conscious Recall | Examples in Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Declarative (Explicit) Memory | Facts, events, and knowledge that can be consciously recalled | Yes - requires conscious effort to retrieve | Historical dates, vocabulary definitions, personal experiences |

| Episodic Memory (Type of Declarative) | Personal experiences and specific events in time | Yes - "mental time travel" to remember events | Remembering a school trip, what happened in yesterday's lesson, personal life events |

| Semantic Memory (Type of Declarative) | General knowledge and facts about the world | Yes - but without remembering when/where learned | Knowing London is the capital of England, understanding what photosynthesis is, vocabulary knowledge |

| Procedural (Implicit) Memory | Skills, habits, and how to do things | No - automatic, unconscious performance | Riding a bike, touch-typing, reading fluency, mathematical procedures |

Memory retrieval is influenced not just by the content itself but by the context in which it was learned. The principles of context-dependent learning explain why students sometimes struggle to recall information in unfamiliar testing environments. Understanding this phenomenon helps teachers design learning experiences that either match assessment contexts or deliberately vary contexts to build more flexible memory access through retrieval practice.

Declarative memory, often juxtaposed with procedural memory, is a critical element in our cognitive architecture. Understanding how declarative and working memory systemsinteract is essential for effective teaching, as it, facilitating the retrieva l of experiences, facts, and concepts. This type of memory is integral to our understanding of the world and ourselves, shaping our current perspective and guiding our interactions.

At its core, declarative memory is divided into two subtypes: episodic and semantic memory. Episodic memory is akin to a personal narrative, enabling us to revisit specific events, like the joy of a childhood birthday or the serene ambience of a family holiday.

It's a tapestry of personal experiences, woven with the threads of individual context and subjective interpretation. Semantic memory, in contrast, is the repository of our factual knowledge, the bedrock of our understanding of universal truths and concepts. It's where we store the fact that Paris is the capital of France or the principles of gravity.

These two strands, while under the declarative memory umbrella, differ in their essence. Episodic memory is about reliving unique, personal moments, while semantic memory is about accessing impersonal, general knowledge. They collectively enable us to navigate the complex world, providing a multifaceted framework for critical thinking.

Declarative memory's role extends beyond mere recollection. It involves intricate cognitive functions, engaging areas like the prefrontal and temporal cortex. It plays a part in spatial memory, influencing how we perceive and remember locations and spaces. In the field of speech-sound learning and emotional learning, declarative memory contributes significantly, impacting how we process and retain linguistic and emotional information. Understanding these processes helps teachers develop effective questioning strategies that activate both episodic and semantic knowledge.

In children, the development of declarative-memory skills is crucial. It shapes their learning, allowing them to accumulate and apply knowledge effectively. This is particularly important when considering sen students who may require differentiation strategies to support their memory development. This memory space is not static; it evolves with our experiences and cognitive growth, reflecting our ever-changing understanding of the world. Teachers can support this development through spaced practice and by helping students understand how their own metacognition influences memory formation.

Key Insights:

Declarative memory, thus, is not just a storehouse of past events and facts. It's a dynamic, evolving construct that shapes our perception, learning, and interaction with the world, highlighting the intricate organisation of memory within our cognitive system. Teachers can use techniques like dual coding to strengthen memory formation, while understanding that student attention and motivation play crucial roles in how well declarative memories are formed and retrieved. Without proper reinforcement, information stored in declarative memory follows the forgetting curve, making systematic review essential for long-term retention.

ata-rt-dimensions="854:480">Declarative memory, therefore, is far more than just recalling facts; it's about crafting a coherent and meaningful narrative of the world around us. By understanding its nuances, teachers can create learning experiences that resonate deeply, transforming information into lasting, accessible knowledge for their students.

Here are some practical strategies that teachers can implement to enhance the development and utilisation of declarative memory in their students:

The distinction between semantic and episodic memory is fundamental to understanding how students process and store different types of information. Semantic memory contains our general knowledge about the world - facts, concepts, and meanings that exist independently of when or where we learned them. In contrast, episodic memory stores our personal experiences and specific events, complete with contextual details about time, place, and circumstances. This difference has profound implications for how teachers present information and design learning experiences.

In the classroom, semantic memory encompasses the factual knowledge students need to master across subjects. For example, knowing that the Battle of Hastings occurred in 1066, understanding photosynthesis as the process plants use to convert sunlight into energy, or recognising that Shakespeare wrote Hamlet are all examples of semantic memory. Students can recall these facts without necessarily remembering the specific lesson where they learned them. This type of memory forms the foundation of academic knowledge and is heavily emphasised in many areas of the UK National Curriculum.

Episodic memory, however, captures the rich experiential context of learning. A Year 7 student might have episodic memories of conducting their first science experiment, the excitement of a particular poetry lesson, or the specific moment when a mathematical concept finally 'clicked' during group work. These memories include the content learned and the emotions, sensory details, and social context surrounding the learning experience. Research shows that when episodic and semantic memories are linked, recall becomes more robust and meaningful.

Understanding this distinction helps teachers use both memory systems effectively. While semantic memory is essential for building knowledge, episodic memories can serve as powerful retrieval cues. When students struggle to recall semantic information, teachers can prompt them to remember the specific context in which they learned it: "Remember when we acted out the water cycle in the playground?" This approach helps bridge the gap between experiential learning and factual recall, making abstract concepts more memorable and accessible.

Strengthening declarative memory requires deliberate instructional strategies that align with how the brain naturally processes and consolidates information. Retrieval practice stands as one of the most effective evidence-based approaches. Rather tha n simply re-reading notes or reviewing materials passively, students need regular opportunities to actively recall information from memory. This might involve low-stakes quizzes at the start of lessons, exit tickets requiring students key points, or collaborative recall activities where pupils work together to reconstruct yesterday's learning without looking at their books.

Spaced repetition amplifies the benefits of retrieval practice by strategically timing when information is revisited. Instead of cramming all related content into one intensive session, teachers can distribute learning across multiple lessons with increasing intervals between reviews. For instance, introducing fractions in mathematics, then revisiting the concept after three days, then a week later, then three weeks later. This spacing effect helps transfer information from short-term to long-term memory more effectively than massed practice. Many schools now build this principle into their curriculum planning, ensuring key concepts resurface regularly across terms.

Elaborative rehearsal strengthens declarative memory by encouraging students to connect new information with existing knowledge structures. When teaching about the Roman invasion of Britain, for example, teachers might ask students to compare Roman military tactics with modern warfare they've seen in films, or link Roman road building to contemporary infrastructure projects. This approach activates schema theory principles, where new information is more readily encoded when it can be meaningfully connected to prior knowledge. The process of creating these connections deepens understanding and provides multiple pathways for later retrieval.

Teachers can also enhance declarative memory through dual coding strategies that engage both verbal and visual processing systems. This might involve creating mind maps that combine keywords with images, using graphic organisers to represent relationships between concepts, or encouraging students to draw diagrams while explaining processes aloud. Additionally, varying the context in which information is encountered helps build flexible retrieval pathways. Teaching the same historical concept through role-play, documentary analysis, and written sources ensures students can access the information regardless of how it's later assessed.

Sleep plays a crucial role in memory consolidation, the process by which newly acquired information is stabilised and integrated into long-term memory stores. During sleep, particularly during slow-wave sleep phases, the brain actively rehearses and strengthens the neural connections formed during daytime learning. The hippocampus, which initially holds new declarative memories, communicates with the neocortex to gradually transfer information for permanent storage. This process means that what students learn today becomes more firmly embedded in memory after a good night's sleep, making adequate rest an essential component of effective learning.

Research demonstrates that students who get sufficient sleep show significantly better retention of classroom material compared to their sleep-deprived peers. The consolidation process is particularly important for declarative memory because it helps organise factual information and personal experiences into coherent, retrievable knowledge structures. When students consistently lack adequate sleep, this consolidation process is disrupted, leading to fragmented memory formation and increased forgetting. This has direct implications for academic performance across all subjects, from remembering historical dates to retaining mathematical procedures.

For teachers, understanding sleep's role in memory consolidation can inform both pedagogy and pastoral care. Timing of learning activities becomes important - introducing complex new concepts earlier in the day when students are more alert, and using later lessons for review and application rather than initial acquisition. Teachers can also educate students and parents about healthy sleep hygiene, emphasising that consistent bedtimes and sufficient sleep duration (typically 9-10 hours for secondary school students) directly impact academic success. Some schools now incorporate sleep education into their PSHE curriculum, recognising its fundamental importance for learning.

The implications extend beyond individual study habits to whole-school policies. Early school start times can be particularly problematic for adolescents, whose natural circadian rhythms shift towards later sleep and wake times. Schools that have implemented later start times often report improved attendance, better academic performance, and enhanced student wellbeing. Additionally, teachers can be mindful of homework timing, ensuring that demanding cognitive tasks aren't scheduled immediately before bedtime, as this can interfere with both sleep onset and the natural memory consolidation processes that occur during rest.

Declarative memory is a cornerstone of learning and cognition, enabling us to consciously recall facts, events, and concepts. By understanding its two key components, episodic and semantic memory, educators can tailor their teaching strategies to enhance students' ability to encode, store, and retrieve information effectively. Using techniques like contextual learning, storytelling, and spaced repetition can significantly improve declarative memory skills.

Furthermore, recognising the influence of context, emotion, and sensory input on memory formation allows teachers to create more engaging and memorable learning experiences. By focusing on active recall, linking new information to existing knowledge, and promoting metacognitive awareness, educators can helps students to become more effective and self-regulated learners. Ultimately, a deep understanding of declarative memory not only enriches teaching practices but also cultivates a lifelong love of learning in students.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/declarative-memory#article","headline":"Declarative Memory","description":"Explore the facets of declarative memory, including semantic and episodic types, and their roles in cognitive processing and recall.","datePublished":"2023-11-16T15:56:29.615Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/declarative-memory"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69513cc90043b996c963571a_8m1570.webp","wordCount":4289},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/declarative-memory#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Declarative Memory","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/declarative-memory"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What Is the Difference Between Semantic and Episodic Memory?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The distinction between semantic and episodic memory is fundamental to understanding how students process and store different types of information. Semantic memory contains our general knowledge about the world - facts, concepts, and meanings that exist independently of when or where we learned them. In contrast, episodic memory stores our personal experiences and specific events, complete with contextual details about time, place, and circumstances. This difference has profound implications for"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Can Teachers Strengthen Students' Declarative Memory?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Strengthening declarative memory requires deliberate instructional strategies that align with how the brain naturally processes and consolidates information. Retrieval practice stands as one of the most effective evidence-based approaches. Rather tha n simply re-reading notes or reviewing materials passively, students need regular opportunities to actively recall information from memory. This might involve low-stakes quizzes at the start of lessons, exit tickets requiring students key points, or"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why Does Sleep Matter for Memory Consolidation?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Sleep plays a crucial role in memory consolidation , the process by which newly acquired information is stabilised and integrated into long-term memory stores. During sleep, particularly during slow-wave sleep phases, the brain actively rehearses and strengthens the neural connections formed during daytime learning. The hippocampus , which initially holds new declarative memories, communicates with the neocortex to gradually transfer information for permanent storage. This process means that wha"}}]}]}