Educational psychologists in schools

Explore the vital role of educational psychologists in schools and how their expertise enhances student learning and support systems.

Explore the vital role of educational psychologists in schools and how their expertise enhances student learning and support systems.

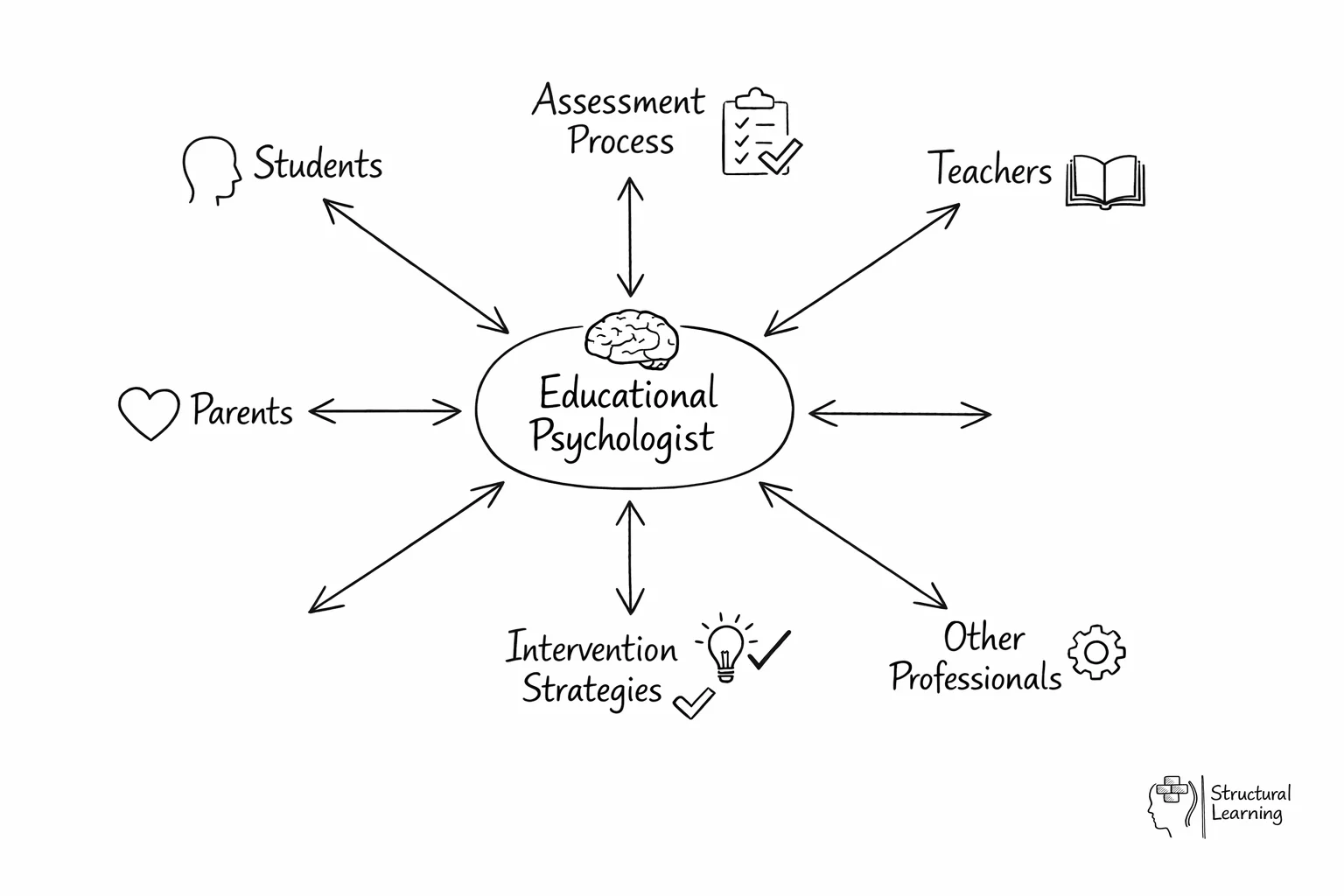

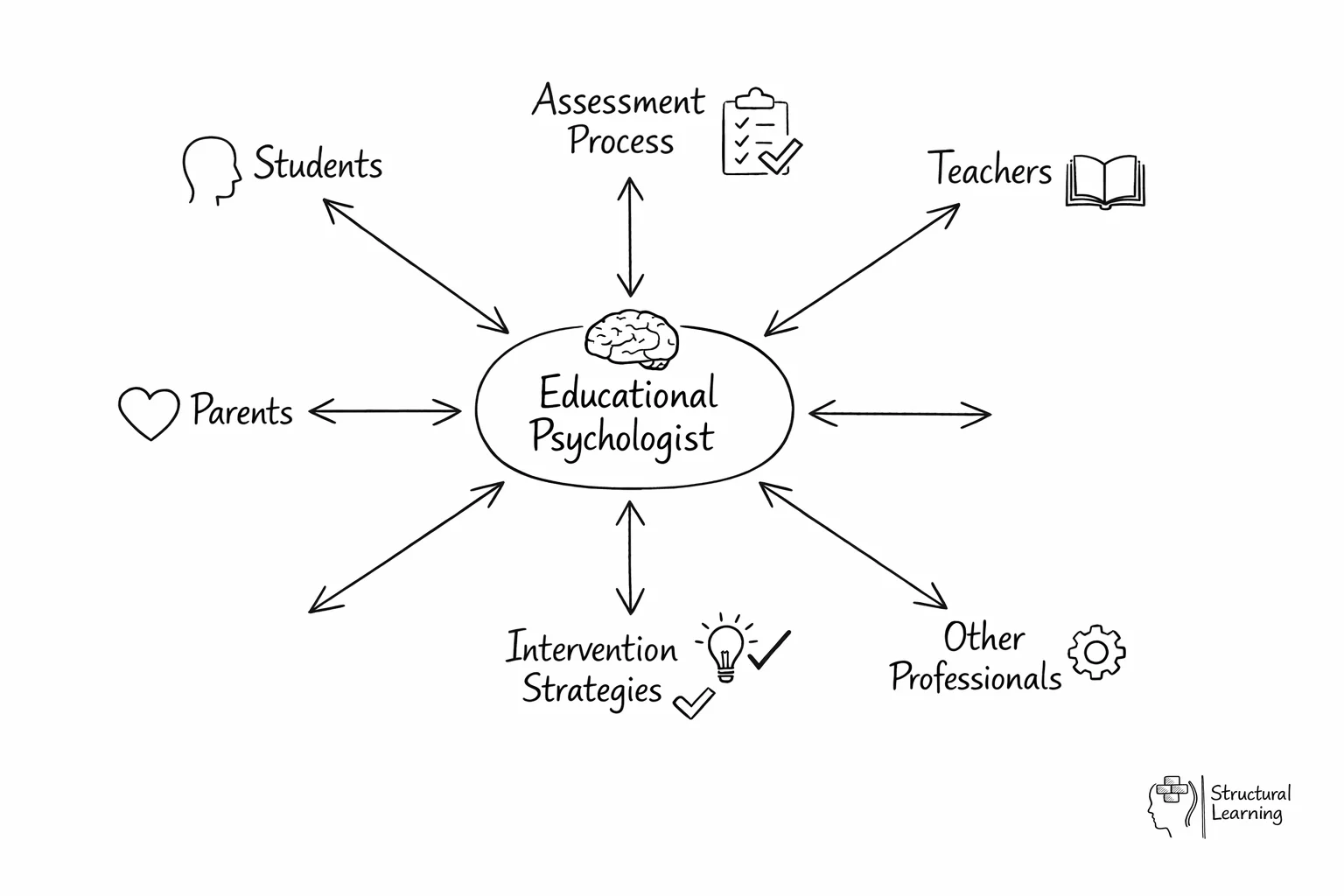

Educational psychologists assess how children learn and identify barriers to their educational progress through cognitive, social, and emotional evaluations. They work with students of all ages to diagnose learning difficulties, behavioral issues, and developmental challenges that impact academic performance. Their assessments help create targeted intervention strategies that teachers and parents can implement to support student success.

Educational psychologists deal with children of all ages and how they learn. While analysing how children process cognitive, social and emotional stimuli, educational psychologists make assessments on basis of the children's responses towards stimuli. This analysis helps in the identification of children's social, behavioral and learning issues that impede their learning process.

In current times, the field of educational psychology has expanded beyond elementary and preschool school classrooms to help adults in educational settings. Educational psychologists have greatly benefited adults with special educational needs.

Although educational psychologists have helped people of all ages, still their role is different from general psychologists. Educational psychology is a branch of Psychology; whereas, general psychologists have a vast overview of the study of psychology as it deals with the study of psychological functioning and mental health. In this article, we will look at the critical role that these professionals have in the assessment of children in educational environments. Your local authority psychologist may well be able to provide a new perspective on the difficulties children are facing.

As well as the assessment of children, they may well have some ideas about how to improve the education of children who are struggling in class. This might involve practical support such as improving the behavioural skills or attention skills of the child. The duties of school psychologists are quite wide and in recent times, the demand has outgrown their supply. Most teachers will have a child in class who they believe could well do with the support of mental health professionals, unless an institution wants to turn to a private practice for advice, we are often left with our local authorities expertise.

Educational psychologists support schools by conducting assessments, developing intervention plans, and training teachers in evidence-based strategies for diverse learners. They observe students in classroom settings to identify learning barriers and collaborate with teaching staff to implement practical solutions. Their role extends beyond individual assessments to include whole-school approaches for improving learning outcomes and mental health support.

The educational system of the 21st century is highly complex and there is no single learning strategythat works for every student.

For this reason, psychologists working in the area of education are focused on identifying and studying the learning strategies to better understand how persons learn and retain new knowledge.

Educational psychologists working in Educational Psychology Service apply human development theories to understand individual children learning styles and inform the teaching process. Although interaction with learners and teachers in educational settings is a major part of their work, it isn't the only aspect of their job. Learning is a lifelong process. School is not the only place where people learn, people learn from social situations, at work, and even when they are doing simple household chores. Through examining how persons learn in various settings, educational psychologists endeavour to identify strategies and approaches to make the learning process more effective.

Educational psychologists primarily work in schools, local education authorities, and specialist assessment centers, serving students from preschool through adult education. They split their time between direct student assessments, classroom observations, and consultations with teachers and parents. Many also work in private practice, children's services, or research institutions focusing on learning and development.

Educational psychologists often work with students who have various learning challenges, including autism, ADHD, and dyslexia. They also focus on enhancing engagement and motivation in learning environments. Additionally, these professionals contribute to developing constructivist approaches and supporting wellbeing initiatives in schools. They may also assist teachers in improving literacy instruction and implementing social-emotional learning programs.

Educational psychologists can work in many environments. These mainly include:

These psychologists work with students, families, teachers, and other professionals to create supportive and effective learning environments for all children. Their broad skill set ensures they can adapt to various educational needs and settings, making them invaluable assets in developing student development and academic success.

Educational psychologists in the UK typically complete an undergraduate degree in psychology, followed by postgraduate training in educational psychology. This includes a doctorate or professional training course accredited by the British Psychological Society (BPS). Trainees gain experience through placements in schools and other educational settings, learning to apply psychological principles to real-world educational challenges.

To become a qualified educational psychologist in the UK, several steps must be followed. First, a bachelor's degree in psychology is required, providing a foundation in psychological theories and research methods. Following this, individuals must gain practical experience, often through working in educational settings such as schools or child development centres. This experience helps them understand the challenges and needs of students and educators.

Next, aspiring educational psychologists undertake postgraduate training in educational psychology. This typically involves completing a doctorate (DEdPsy) or a professional training course accredited by the BPS. These programmes provide advanced knowledge in areas such as child development, learning theories, and assessment techniques. Trainees also participate in supervised placements, where they apply their knowledge in real-world settings, working with students, teachers, and families to address educational and developmental issues. Upon completion of their training, graduates can register with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) and practice as qualified educational psychologists.

Knowing when to make that referral can feel like walking a tightrope. You don't want to overreact to temporary struggles, but waiting too long might mean missing crucial intervention windows. Generally, if you've tried differentiated strategies for at least six weeks without meaningful progress, it's time to document your concerns and start the referral process.

The key indicators that warrant a referral go beyond academic struggles. Watch for persistent difficulties with social interactions, emotional regulation that disrupts learning for the student and others, or significant gaps between ability and achievement. Perhaps you've noticed a bright student who can articulate complex ideas verbally but struggles to write a simple paragraph, or a child whose behaviour completely changes in certain learning situations.

Before making the referral, gather concrete evidence. Keep dated observations, work samples showing the difficulty patterns, and records of interventions you've already tried. This isn't just bureaucracy - it helps the educational psychologist understand the full picture and speeds up the assessment process. Your detailed classroom observations often provide insights that formal testing alone might miss.

Those precious consultation hours with an educational psychologist need careful planning to yield the best results. Start by preparing a focused list of your most pressing concerns, but don't just list problems - include what you've already tried and what seemed to help, even slightly. Educational psychologists aren't there to judge your teaching; they're collaborative partners who value your classroom expertise.

During the consultation, be specific about when and where behaviours occur. Instead of saying "Jamie can't concentrate," you might explain that "Jamie focuses well during hands-on science activities but loses focus within five minutes during independent writing tasks." These specifics help the EP identify patterns and suggest targeted strategies rather than generic advice.

Ask for demonstration and modelling, not just verbal advice. If the EP suggests a particular intervention technique, request to see it in action or ask for coaching while you try it. Many educational psychologists are happy to model strategies with your students, which gives you a chance to observe and ask questions in real time. This practical approach means you're more likely to implement strategies correctly and confidently.

The waiting period between referral and assessment often stretches for months, but this time doesn't have to be wasted. Use it to build a comprehensive picture of the student's needs through systematic observation. Create a simple tracking sheet noting triggers, successful strategies, and patterns in the student's learning and behaviour. This documentation becomes invaluable when the EP finally arrives.

Communication with parents during this waiting period requires particular sensitivity. They're often anxious about the assessment and what it might reveal. Regular updates about their child's progress and the strategies you're trying can help maintain trust. Share specific positives alongside concerns - perhaps their child shows remarkable creativity despite literacy struggles, or demonstrates strong problem-solving skills when working with peers.

While waiting, implement evidence-based interventions that don't require a formal diagnosis. Many strategies that help students with specific learning difficulties actually benefit the whole class. For instance, breaking instructions into smaller chunks, using visual schedules, or incorporating movement breaks can support various learners. Document how the student responds to these universal strategies, as this information helps the EP understand what might work in a more targeted intervention plan.

Knowing when to refer a pupil for an educational psychology assessment can feel like walking a tightrope. You don't want to overreact to temporary struggles, but equally, you can't afford to let genuine needs go unidentified. The key is recognising patterns rather than isolated incidents. If a child consistently struggles despite quality-first teaching and targeted interventions over at least two terms, it's probably time to have that conversation with your SENCO.

Look for clusters of concerns that persist across different contexts. Perhaps you've noticed a Year 4 pupil who can articulate complex ideas verbally but produces barely legible written work, struggles to copy from the board, and frequently loses their place when reading. Or maybe there's a secondary student whose behaviour deteriorates specifically during tasks requiring sustained concentration, who seems to understand concepts but can't demonstrate this in tests. These patterns often point to underlying processing difficulties that an educational psychologist can help unpick.

Before making a referral, document everything. Keep samples of work showing the gap between ability and output, note specific triggers for behavioural concerns, and record which strategies you've already tried. This evidence isn't just bureaucracy - it helps the educational psychologist understand the child's needs more quickly and makes their limited time with your pupil count. Remember, with waiting lists often stretching to six months or more, your detailed observations might be the difference between a useful assessment and a missed opportunity.

The reality of lengthy waiting lists means you'll often need to support pupils for months before an educational psychologist arrives. Rather than viewing this as lost time, treat it as an opportunity to gather rich data about what works. Start with simple environmental adjustments - you'd be surprised how many children transform when given a wobble cushion, noise-reducing headphones, or simply moved away from the window. These low-cost tweaks can provide immediate relief whilst building evidence for formal recommendations.

Create your own informal assessment toolkit. Use free online screeners for dyslexia indicators, observe processing speed during different tasks, and note discrepancies between verbal and written responses. Try different presentation methods for the same content - some children who struggle with traditional worksheets might excel when information is presented through diagrams or hands-on activities. Document everything in a simple spreadsheet: date, intervention tried, outcome. This becomes invaluable data for the educational psychologist and might reveal patterns you hadn't noticed.

Collaborate with parents to build a fuller picture. Send home simple observation sheets focusing on homework behaviours, sleep patterns, and social interactions. Many parents don't realise that taking three hours to complete 20 minutes of homework isn't typical, or that their child's anxiety about school starts on Sunday afternoon. These insights from home often provide crucial pieces of the puzzle that classroom observations alone might miss.

When that precious appointment finally arrives, preparation is everything. Two weeks before the visit, create a one-page summary highlighting your key concerns, strategies attempted, and specific questions you need answered. Educational psychologists typically have just 2-3 hours per child, including report writing time, so clarity about your priorities helps them focus their assessment where it's most needed.

Arrange the timetable strategically on assessment day. Avoid scheduling PE immediately before (when children might be physically tired) or right after lunch (when attention naturally dips). If possible, ensure the child has had a successful experience earlier that day - perhaps starting with their favourite subject. Brief the educational psychologist about any recent events that might affect performance: a bereavement, friendship troubles, or even just recovering from illness can significantly impact assessment results.

After the assessment, don't just file away the report. Schedule a follow-up meeting to clarify recommendations and create an action plan. Ask specific questions: "When you suggest 'multi-sensory teaching methods,' what exactly would that look like in Year 7 science?" or "How can I adapt this strategy for whole-class teaching rather than one-to-one work?" The best educational psychologist reports include practical strategies, but you might need to push for the detail that makes them workable in your specific context. Remember, their expertise combined with your classroom knowledge creates the most effective support plan.

Educational psychologists play a crucial role in schools and educational settings, offering support to students, teachers, and parents. Their expertise in understanding learning processes and addressing barriers to education makes them invaluable assets in developing positive learning environments. By conducting thorough assessments, developing targeted interventions, and providing training and consultation, they contribute significantly to improving student outcomes and promoting overall wellbeing.

As the field of education continues to evolve, the role of educational psychologists will remain vital. Their ability to adapt to changing educational needs, implement evidence-based strategies, and collaborate with various stakeholders ensures that students receive the support they need to thrive academically and emotionally. By prioritising early intervention and promoting inclusive practices, educational psychologists help create a more equitable and effective educational system for all learners.

Educational psychologists assess how children learn and identify barriers to their educational progress through cognitive, social, and emotional evaluations. They work with students of all ages to diagnose learning difficulties, behavioral issues, and developmental challenges that impact academic performance. Their assessments help create targeted intervention strategies that teachers and parents can implement to support student success.

Educational psychologists deal with children of all ages and how they learn. While analysing how children process cognitive, social and emotional stimuli, educational psychologists make assessments on basis of the children's responses towards stimuli. This analysis helps in the identification of children's social, behavioral and learning issues that impede their learning process.

In current times, the field of educational psychology has expanded beyond elementary and preschool school classrooms to help adults in educational settings. Educational psychologists have greatly benefited adults with special educational needs.

Although educational psychologists have helped people of all ages, still their role is different from general psychologists. Educational psychology is a branch of Psychology; whereas, general psychologists have a vast overview of the study of psychology as it deals with the study of psychological functioning and mental health. In this article, we will look at the critical role that these professionals have in the assessment of children in educational environments. Your local authority psychologist may well be able to provide a new perspective on the difficulties children are facing.

As well as the assessment of children, they may well have some ideas about how to improve the education of children who are struggling in class. This might involve practical support such as improving the behavioural skills or attention skills of the child. The duties of school psychologists are quite wide and in recent times, the demand has outgrown their supply. Most teachers will have a child in class who they believe could well do with the support of mental health professionals, unless an institution wants to turn to a private practice for advice, we are often left with our local authorities expertise.

Educational psychologists support schools by conducting assessments, developing intervention plans, and training teachers in evidence-based strategies for diverse learners. They observe students in classroom settings to identify learning barriers and collaborate with teaching staff to implement practical solutions. Their role extends beyond individual assessments to include whole-school approaches for improving learning outcomes and mental health support.

The educational system of the 21st century is highly complex and there is no single learning strategythat works for every student.

For this reason, psychologists working in the area of education are focused on identifying and studying the learning strategies to better understand how persons learn and retain new knowledge.

Educational psychologists working in Educational Psychology Service apply human development theories to understand individual children learning styles and inform the teaching process. Although interaction with learners and teachers in educational settings is a major part of their work, it isn't the only aspect of their job. Learning is a lifelong process. School is not the only place where people learn, people learn from social situations, at work, and even when they are doing simple household chores. Through examining how persons learn in various settings, educational psychologists endeavour to identify strategies and approaches to make the learning process more effective.

Educational psychologists primarily work in schools, local education authorities, and specialist assessment centers, serving students from preschool through adult education. They split their time between direct student assessments, classroom observations, and consultations with teachers and parents. Many also work in private practice, children's services, or research institutions focusing on learning and development.

Educational psychologists often work with students who have various learning challenges, including autism, ADHD, and dyslexia. They also focus on enhancing engagement and motivation in learning environments. Additionally, these professionals contribute to developing constructivist approaches and supporting wellbeing initiatives in schools. They may also assist teachers in improving literacy instruction and implementing social-emotional learning programs.

Educational psychologists can work in many environments. These mainly include:

These psychologists work with students, families, teachers, and other professionals to create supportive and effective learning environments for all children. Their broad skill set ensures they can adapt to various educational needs and settings, making them invaluable assets in developing student development and academic success.

Educational psychologists in the UK typically complete an undergraduate degree in psychology, followed by postgraduate training in educational psychology. This includes a doctorate or professional training course accredited by the British Psychological Society (BPS). Trainees gain experience through placements in schools and other educational settings, learning to apply psychological principles to real-world educational challenges.

To become a qualified educational psychologist in the UK, several steps must be followed. First, a bachelor's degree in psychology is required, providing a foundation in psychological theories and research methods. Following this, individuals must gain practical experience, often through working in educational settings such as schools or child development centres. This experience helps them understand the challenges and needs of students and educators.

Next, aspiring educational psychologists undertake postgraduate training in educational psychology. This typically involves completing a doctorate (DEdPsy) or a professional training course accredited by the BPS. These programmes provide advanced knowledge in areas such as child development, learning theories, and assessment techniques. Trainees also participate in supervised placements, where they apply their knowledge in real-world settings, working with students, teachers, and families to address educational and developmental issues. Upon completion of their training, graduates can register with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) and practice as qualified educational psychologists.

Knowing when to make that referral can feel like walking a tightrope. You don't want to overreact to temporary struggles, but waiting too long might mean missing crucial intervention windows. Generally, if you've tried differentiated strategies for at least six weeks without meaningful progress, it's time to document your concerns and start the referral process.

The key indicators that warrant a referral go beyond academic struggles. Watch for persistent difficulties with social interactions, emotional regulation that disrupts learning for the student and others, or significant gaps between ability and achievement. Perhaps you've noticed a bright student who can articulate complex ideas verbally but struggles to write a simple paragraph, or a child whose behaviour completely changes in certain learning situations.

Before making the referral, gather concrete evidence. Keep dated observations, work samples showing the difficulty patterns, and records of interventions you've already tried. This isn't just bureaucracy - it helps the educational psychologist understand the full picture and speeds up the assessment process. Your detailed classroom observations often provide insights that formal testing alone might miss.

Those precious consultation hours with an educational psychologist need careful planning to yield the best results. Start by preparing a focused list of your most pressing concerns, but don't just list problems - include what you've already tried and what seemed to help, even slightly. Educational psychologists aren't there to judge your teaching; they're collaborative partners who value your classroom expertise.

During the consultation, be specific about when and where behaviours occur. Instead of saying "Jamie can't concentrate," you might explain that "Jamie focuses well during hands-on science activities but loses focus within five minutes during independent writing tasks." These specifics help the EP identify patterns and suggest targeted strategies rather than generic advice.

Ask for demonstration and modelling, not just verbal advice. If the EP suggests a particular intervention technique, request to see it in action or ask for coaching while you try it. Many educational psychologists are happy to model strategies with your students, which gives you a chance to observe and ask questions in real time. This practical approach means you're more likely to implement strategies correctly and confidently.

The waiting period between referral and assessment often stretches for months, but this time doesn't have to be wasted. Use it to build a comprehensive picture of the student's needs through systematic observation. Create a simple tracking sheet noting triggers, successful strategies, and patterns in the student's learning and behaviour. This documentation becomes invaluable when the EP finally arrives.

Communication with parents during this waiting period requires particular sensitivity. They're often anxious about the assessment and what it might reveal. Regular updates about their child's progress and the strategies you're trying can help maintain trust. Share specific positives alongside concerns - perhaps their child shows remarkable creativity despite literacy struggles, or demonstrates strong problem-solving skills when working with peers.

While waiting, implement evidence-based interventions that don't require a formal diagnosis. Many strategies that help students with specific learning difficulties actually benefit the whole class. For instance, breaking instructions into smaller chunks, using visual schedules, or incorporating movement breaks can support various learners. Document how the student responds to these universal strategies, as this information helps the EP understand what might work in a more targeted intervention plan.

Knowing when to refer a pupil for an educational psychology assessment can feel like walking a tightrope. You don't want to overreact to temporary struggles, but equally, you can't afford to let genuine needs go unidentified. The key is recognising patterns rather than isolated incidents. If a child consistently struggles despite quality-first teaching and targeted interventions over at least two terms, it's probably time to have that conversation with your SENCO.

Look for clusters of concerns that persist across different contexts. Perhaps you've noticed a Year 4 pupil who can articulate complex ideas verbally but produces barely legible written work, struggles to copy from the board, and frequently loses their place when reading. Or maybe there's a secondary student whose behaviour deteriorates specifically during tasks requiring sustained concentration, who seems to understand concepts but can't demonstrate this in tests. These patterns often point to underlying processing difficulties that an educational psychologist can help unpick.

Before making a referral, document everything. Keep samples of work showing the gap between ability and output, note specific triggers for behavioural concerns, and record which strategies you've already tried. This evidence isn't just bureaucracy - it helps the educational psychologist understand the child's needs more quickly and makes their limited time with your pupil count. Remember, with waiting lists often stretching to six months or more, your detailed observations might be the difference between a useful assessment and a missed opportunity.

The reality of lengthy waiting lists means you'll often need to support pupils for months before an educational psychologist arrives. Rather than viewing this as lost time, treat it as an opportunity to gather rich data about what works. Start with simple environmental adjustments - you'd be surprised how many children transform when given a wobble cushion, noise-reducing headphones, or simply moved away from the window. These low-cost tweaks can provide immediate relief whilst building evidence for formal recommendations.

Create your own informal assessment toolkit. Use free online screeners for dyslexia indicators, observe processing speed during different tasks, and note discrepancies between verbal and written responses. Try different presentation methods for the same content - some children who struggle with traditional worksheets might excel when information is presented through diagrams or hands-on activities. Document everything in a simple spreadsheet: date, intervention tried, outcome. This becomes invaluable data for the educational psychologist and might reveal patterns you hadn't noticed.

Collaborate with parents to build a fuller picture. Send home simple observation sheets focusing on homework behaviours, sleep patterns, and social interactions. Many parents don't realise that taking three hours to complete 20 minutes of homework isn't typical, or that their child's anxiety about school starts on Sunday afternoon. These insights from home often provide crucial pieces of the puzzle that classroom observations alone might miss.

When that precious appointment finally arrives, preparation is everything. Two weeks before the visit, create a one-page summary highlighting your key concerns, strategies attempted, and specific questions you need answered. Educational psychologists typically have just 2-3 hours per child, including report writing time, so clarity about your priorities helps them focus their assessment where it's most needed.

Arrange the timetable strategically on assessment day. Avoid scheduling PE immediately before (when children might be physically tired) or right after lunch (when attention naturally dips). If possible, ensure the child has had a successful experience earlier that day - perhaps starting with their favourite subject. Brief the educational psychologist about any recent events that might affect performance: a bereavement, friendship troubles, or even just recovering from illness can significantly impact assessment results.

After the assessment, don't just file away the report. Schedule a follow-up meeting to clarify recommendations and create an action plan. Ask specific questions: "When you suggest 'multi-sensory teaching methods,' what exactly would that look like in Year 7 science?" or "How can I adapt this strategy for whole-class teaching rather than one-to-one work?" The best educational psychologist reports include practical strategies, but you might need to push for the detail that makes them workable in your specific context. Remember, their expertise combined with your classroom knowledge creates the most effective support plan.

Educational psychologists play a crucial role in schools and educational settings, offering support to students, teachers, and parents. Their expertise in understanding learning processes and addressing barriers to education makes them invaluable assets in developing positive learning environments. By conducting thorough assessments, developing targeted interventions, and providing training and consultation, they contribute significantly to improving student outcomes and promoting overall wellbeing.

As the field of education continues to evolve, the role of educational psychologists will remain vital. Their ability to adapt to changing educational needs, implement evidence-based strategies, and collaborate with various stakeholders ensures that students receive the support they need to thrive academically and emotionally. By prioritising early intervention and promoting inclusive practices, educational psychologists help create a more equitable and effective educational system for all learners.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/educational-psychologists-in-schools#article","headline":"Educational psychologists in schools","description":"Explore the vital role of educational psychologists in schools and how their expertise enhances student learning and support systems.","datePublished":"2022-02-09T14:00:50.844Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/educational-psychologists-in-schools"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6870dda67eb371f27ae6f6e2_6203c2f920e4ebfa91bbba8e_What%2520does%2520an%2520educational%2520psychologist%2520do.jpeg","wordCount":2118},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/educational-psychologists-in-schools#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Educational psychologists in schools","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/educational-psychologists-in-schools"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/educational-psychologists-in-schools#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What specific conditions can educational psychologists diagnose, and when should schools refer to medical professionals instead?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Educational psychologists can diagnose dyspraxia and dyslexia but cannot formally diagnose autism spectrum disorders, which require medically trained healthcare professionals. For ADHD, their diagnostic ability varies by local authority, so schools should first contact a SENCO or GP. This distinctio"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How do educational psychologists support teachers in the classroom beyond individual student assessments?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Educational psychologists observe students in classroom settings to identify learning barriers and collaborate with teaching staff to implement evidence-based strategies for diverse learners. They also train teachers in practical approaches and develop whole-school interventions for improving learni"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What should schools do when facing long waiting lists for educational psychology assessments?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Schools can explore private practice options or work with their local authority to find practical alternatives while waiting for formal assessments. Teachers should document classroom observations and collaborate with SENCOs to implement initial support strategies. Educational psychologists often pr"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can educational psychologists help students experiencing mental health issues that affect their learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Educational psychologists identify mental health concerns such as anxiety and depression that create"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What practical support do educational psychologists provide for children struggling with behaviour or attention in class?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Educational psychologists assess the underlying causes of behavioural issues and develop specific strategies to improve children's behavioural skills and active listening abilities. They provide teachers with evidence-based techniques tailored to individual learning styles and needs. Their intervent"}}]}]}