Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development: The Four Stages Explained

Learn about Piaget's four stages of cognitive development. Understand schemas, assimilation, accommodation, and how to apply Piaget's theory in the classroom.

Learn about Piaget's four stages of cognitive development. Understand schemas, assimilation, accommodation, and how to apply Piaget's theory in the classroom.

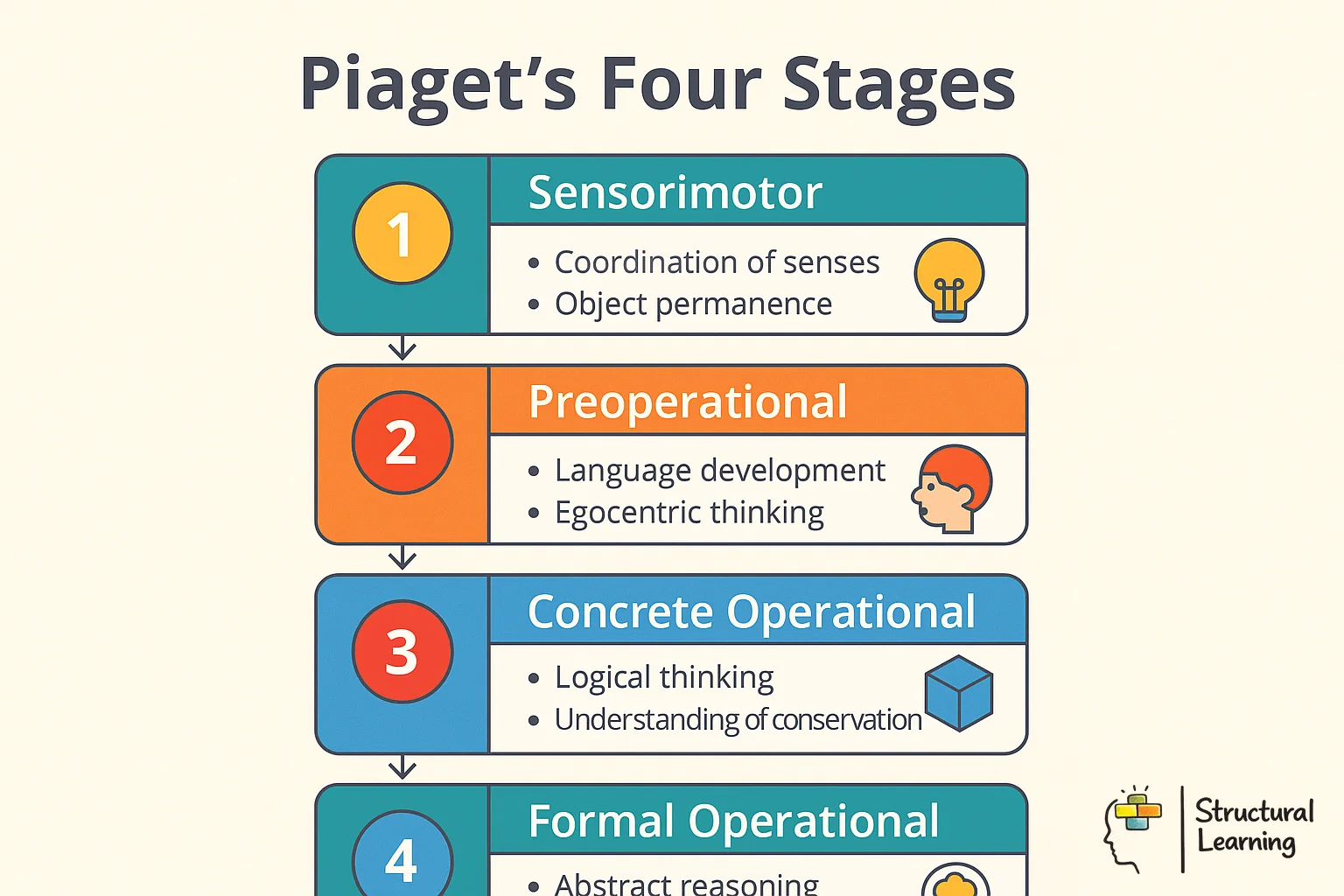

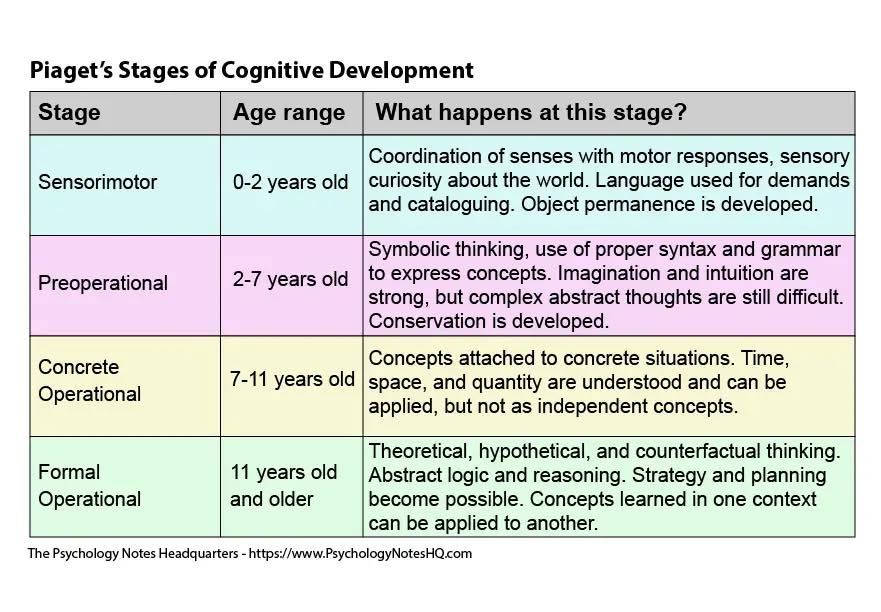

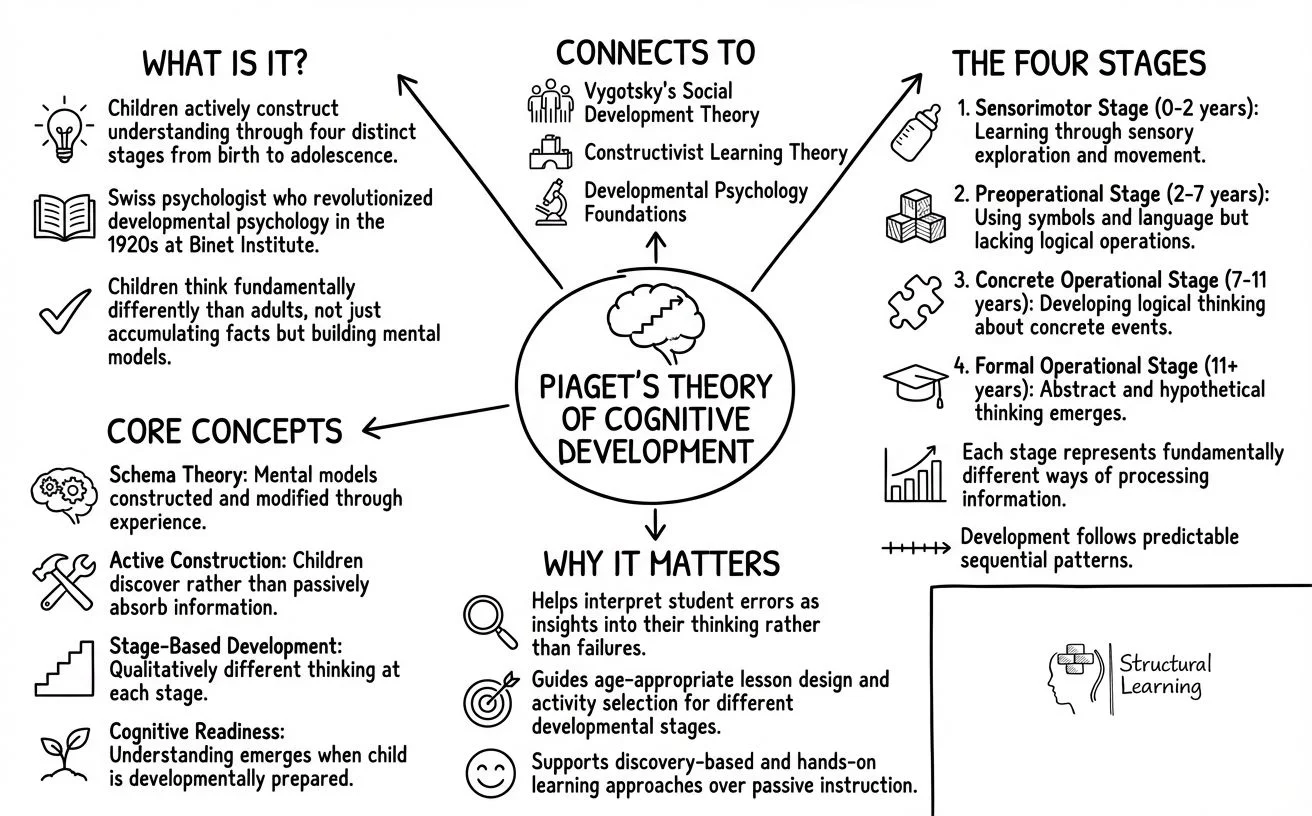

Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development explains how children actively construct their understanding of the world through four distinct stages from birth to adolescence. The theory proposes that children's thinking develops through predictable stages: sensorimotor (0-2 years), preoperational (2-7 years), concrete operational (7-11 years), and formal operational (11+ years). Each stage represents a fundamentally different way of processing informationand understanding reality.

Jean Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development has profoundly shaped how educators and psychologists understand children's thinking. This influential framework suggests that children don't simply accumulate facts as they grow, they actively build mental models of the world through experience. Piaget's schema theory explains how these mental models are constructed and modified over time. Piaget's research remains a cornerstone of developmental psychologyand continues to inform daily teaching. Piaget's developmental stages provide a framework that helps educators understand how children's cognitive abilities evolve over time.

While working at the Binet Institute in the 1920s, Piaget noticed something intriguing: when children gave "wrong" answers on intelligence tests, their mistakes were consistent and revealed unique ways of reasoning. Rather than seeing these answers as failures, he realised they were clues to how children's minds develop.

Both Piaget and Vygotsky transformed our understanding of child development, but they offer distinctly different approaches to classroom learning. Understanding these differences helps teachers choose the most effective strategies for their pupils' developmental needs.

| Aspect | Piaget | Vygotsky |

|---|---|---|

| Core Focus | Individual cognitive development through fixed stages (sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete, formal operational) | Social interaction and cultural context driving cognitive development through Zone of Proximal Development |

| Teacher's Role | Facilitator providing discovery-based activities matched to developmental stage | Active guide using scaffolding techniques and collaborative learning structures |

| Classroom Application | Hands-on exploration, concrete materials, age-appropriate tasks based on cognitive readiness | Peer collaboration, guided practice, think-alouds, and gradual release of responsibility |

| Learning Process | Children construct knowledge independently through experience and equilibration | Learning occurs through social interaction before becoming internalised individual knowledge |

| Assessment Focus | Observing stage-appropriate behaviours and cognitive readiness indicators | Measuring progress within Zone of Proximal Development and scaffolding effectiveness |

| Best Used When | Planning developmentally appropriate activities and understanding cognitive limitations by age | Designing collaborative learning experiences and providing targeted instructional support |

| Key Limitation | May underestimate children's abilities and overlook cultural influences on development | Less specific about age-related capabilities and requires intensive teacher preparation |

Whilst Piaget emphasises individual readiness and stage-based learning, Vygotsky highlights the power of social interaction and guided support. Most effective teachers blend both approaches, using Piaget's stages to inform developmental expectations whilst applying Vygotsky's scaffolding techniques to accelerate learning through collaboration.

Piaget proposed that children are not miniature adults. Instead:

Unlike traditional IQ testing, Piaget was fascinated by how core ideas, like time, number, and fairness, gradually emerge. Through observations, interviews, and meticulous studies of his own children, he charted this growth in detail.

Piaget's model describes four key developmental stages:

This stage-based approachcontinues to guide how teachers design activities that match children's evolving abilities.

Piaget's theory identifies four distinct stages of cognitive development: the sensorimotor stage, preoperational stage, concrete operational stage, and formal operational stage.

The four stages of cognitive development are the sensorimotor stage (0-2 years), preoperational stage (2-7 years), concrete operational stage (7-11 years), and formal operational stage (11+ years).

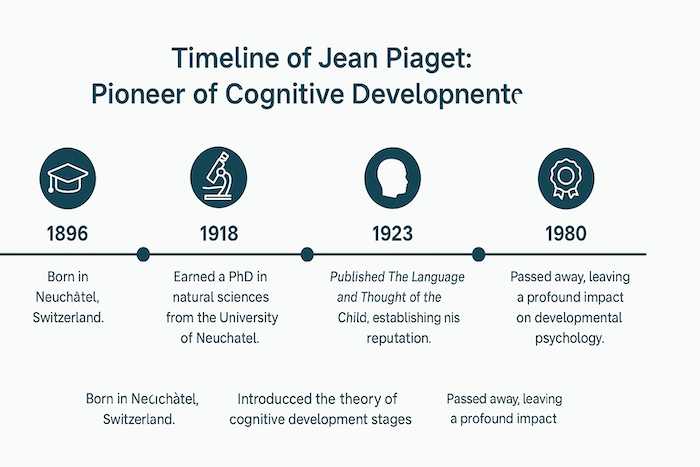

Jean Piaget was a Swiss psychologist who transformed developmental psychology through his groundbreaking research on children's cognitive development. Born in 1896, Piaget developed his influential four-stage theory whilst working at the Binet Institute in the 1920s, where he studied children's reasoning patterns.

Jean Piaget was a Swiss psychologist who transformed our understanding of children's thinking while working at the Binet Institute in the 1920s. He noticed that children's wrong answers on intelligence tests followed consistent patterns, leading him to realise that children think in fundamentally different ways than adults. His observations of his own children and thousands of others formed the basis of his groundbreaking cognitive development theory.

Jean Piaget was born on August 9, 1896, in Neuchâtel, Switzerland. His early life was marked by an intense curiosity and passion for the natural world, leading him to publish his first scientific paper on mollusks at the age of 10. After finishing high school, Piaget initially pursued studies in natural sciences at the University of Neuchâtel, where he earned his doctorate in zoology. However, his academic interests soon shifted to psychology, driven by a fascination with the development of human knowledge and cognition.

During World War I, Piaget worked as an army doctor, an experience that broadened his understanding of human behaviour under stress and change. After the war, he studied psychology and philosophy in Zurich and Paris, where he worked with prominent psychologists such as Alfred Binet at the Binet Institute. This period marked the beginning of his detailed look into child development and experimental psychology.

In 1923, Piaget married Valentine Châtenay, and together they had three children. Observing their development provided Piaget with invaluable insights that formed the foundation of his theories on cognitive development. By the age of 30, Piaget had published his first significant work, "The Language and Thought of the Child," which established his reputation as a leading thinker in developmental psychology.

Piaget's career was distinguished by his association with several prestigious institutions. He held professorships at the University of Geneva and the University of Lausanne and collaborated with many international scholars. His major works, published by leading academic presses such as Harvard University Press, Oxford University Press, and Cambridge University Press, include "The Origins of Intelligence in Children" and "The Construction of Reality in the Child."

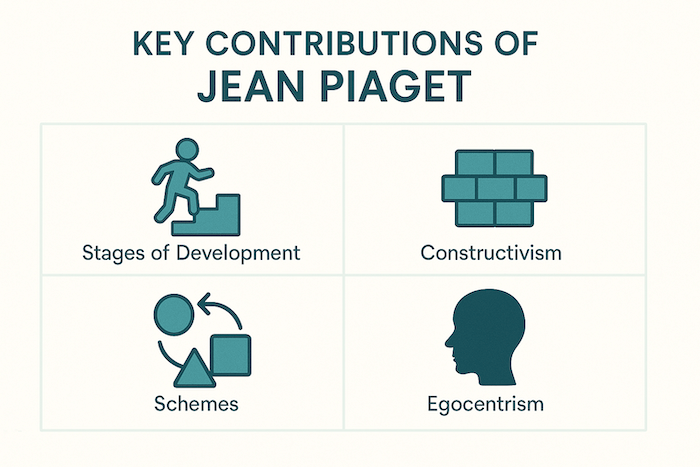

Piaget's contributions to developmental psychology are profound. He introduced the concept of stage theory, proposing that children move through distinct stages of development: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational. His research into the mental structures underlying these stages has significantly influenced educational practices and the understanding of child development. He also explored how children actively construct their understanding of the world through processes that involve assimilation, accommodation, and equilibration.

In addition to his theoretical work, Piaget was a proponent of active learning, advocating that children learn best through interaction with their environment rather than passive reception of information. His insights into language development, logical thinking, and the unique ways preoperational children perceive the world have become foundational in both psychology and education.

Piaget founded the International Centre for Genetic Epistemology in Geneva and was honoured with numerous accolades throughout his career. His legacy continues through the Jean Piaget Society, an organisation dedicated to advancing research in developmental psychology and promoting his ideas.

Jean Piaget passed away on September 16, 1980, but his influence endures. His pioneering work on cognitive development and the stages of development remains a cornerstone of scientific knowledge in psychology, shaping how we understand the growth of human intelligence and learning.

Piaget's four stages of cognitive development are the sensorimotor stage (0-2 years), preoperational stage (2-7 years), concrete operational stage (7-11 years), and formal operational stage (11+ years).

The four stages are: sensorimotor (0-2 years) where infants learn through senses and movement; preoperational (2-7 years) where symbolic thinking emerges but logic is limited; concrete operational (7-11 years) where logical thinking about concrete objects develops; and formal operational (11+ years) where abstract reasoning begins. Each stage builds on the previous one, with children unable to skip stages. Teachers can identify stages by observing specific behaviours like object permanence, conservation understanding, and hypothetical reasoning.

According to Jean Piaget, stages of developmenttakes place via the interaction between natural capacities and environmental happenings, and children experience a series of stages (Wellman, 2011). The sequence of these stages remains same across cultures. Each child goes through the same stages of cognitive development in life but with a different rate. The following are Piaget's stages of intellectual development:

The infants use their actions and senses to explore and learn about their surrounding environment.

During this stage, children develop object permanence, which means they understand that objects continue to exist even when they can't see them. This is a crucial milestone in cognitive development as it allows children to start forming mental representations of the world around them. As they progress through the following stages, they will continue to build on this foundation of knowledge, ultimately developing more complex cognitive abilities.

A variety of cognitive abilities develop at this stage; which mainly include representational play, object permanence, deferred imitation and self-recognition.

At this stage, infants live only in present. They do not have anything related to this world stored in their memory. At age of 8 months, the infant will understand different objects' permanence and they will search for them when they are not present.

Towards the endpoint of this stage, infants' general symbolic function starts to appear and they can use two objects to stand for each other. Language begins to appear when they realise that they can use words to represent feelings and objects. The child starts to store information he knows about the world, label it and recall it.

Piaget identified four distinct stages of cognitive development that children progress through: the sensorimotor stage, preoperational stage, concrete operational stage, and formal operational stage.

From 2 to 7 years

The pre-operational stage is a crucial period in children's cognitive development. During this stage, children's thinking is not yet logical or concrete, and they struggle with concepts like cause and effect. They also have difficulty understanding other people's perspectives, which is why their thinking is egocentric. Additionally, their reasoning is based on intuition rather than logic, which can lead to errors in judgement. Despite these limitations, children in the pre-operational stage are still capable of incredible growth and learning, and for parents and teachers to provide them with the support and guidance they need to thrive.

Young children and Toddlers gain the ability to represent the world internally through mental imagery and language. At this stage, children symbolically think about things. They are able to make one thing, for example, an object or a word, stand for another thing different from itself.

A child mostly thinks about how the world appears, not how it is. At the preoperational stage, children do not show problem-solving or logical thinking. Infants in this age also show animism, which means that they think that toys and other non-living objects have feelings and live like a person.

By an age of 2 years, toddlers can detach their thought process from the physical world. But, they are still not yet able to develop operational or logical thinking skills of later stages.

Their thinking is still egocentric (centred on their own world view) and intuitive (based on children's subjective judgements about events).

7 to 11 years

At this stage, children start to show logical thinkingabout concrete events. They start to grasp the concept of conservation. They understand that, even if things change in appearance but some properties still remain the same. Children at this stage can reverse things mentally. They start to think about other people's feelings and thinking and they also become less egocentric.

This stage is also known as concrete as children begin to think logically. According to Piaget, this stage is a significant turning point of a child's cognitive development because it marks the starting point of operational or logical thinking. At this stage, a child is capable of internally working things out in their head (rather than trying things out in reality).

Another key characteristic of the Concrete Operational Stage is the development of deductive reasoning. Children at this stage can use logic to draw conclusions and solve problems. They are able to understand that if A equals B and B equals C, then A must equal C. This type of reasoning allows them to understand more complex concepts and ideas, setting them up for success in their academic and personal lives.

Children at this stage may become overwhelmed or they may make mistakes when they are asked to reason about hypothetical or abstract problems. Conservation means that the child understands that even if some things change in appearance but their properties may remain the same. At age 6 children are able to conserve number, at age 7 they can conserve mass and at age 9 they can conserve weight. But logical thinking is only used if children ask to reason about physically present materials.

Age 12 and above

At this stage, individuals perform concrete operations on things and they perform formal operations on ideas. Formal logical thinking is totally free from perceptual and physical barriers. During this stage, adolescents can understand abstract concepts. They are able to follow any specific kind of argument without thinking about any particular examples.

During the Formal Operational Stage, children begin to develop the ability to think abstractly and use symbolic reasoning. This means they can think beyond concrete, physical objects and concepts and start to understand more complex and abstract ideas. They can solve hypothetical problems and understand metaphors, analogies, and other abstract concepts. This stage typically occurs between the ages of 11 and 16, but can vary depending on the individual child's development.

Adolescents are capable of dealing with hypothetical problems with several possible outcomes.This stage allows the emergence of scientific reasoning, formulating hypotheses and abstract theories as and whenever needed.

Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development made no claims about any specific age-associated with any of the particular stage but his description provides an indication of the age at which an average child would reach a certain stage.

Piaget's theory emphasises individual cognitive development through stages, whilst Vygotsky's theory focuses on social interaction and cultural influence. Piaget believed children construct knowledge independently, whereas Vygotsky argued that learning occurs through collaborative social experiences within the zone of proximal development.

While Piaget emphasised individual discovery and universal stages, Vygotsky stressed social interaction and cultural influence on development. Piaget believed children must reach certain cognitive stages before learning specific concepts, whereas Vygotsky argued that social guidance could accelerate learning through the Zone of Proximal Development. Both theories value active learning but differ on whether development drives learning (Piaget) or learning drives development (Vygotsky).

In the field of child development and cognition, theories often intersect, each providing a unique lens to understand the intricate processes that govern a child's growth. Renowned psychologists like Jean Piaget have made significant contributions, laying the foundation for further exploration. The following table outlines several prominent psychologists and their theories, highlighting the cooperation with Piaget's ideas. The intertwined nature of these theories underscores the multifaceted nature of cognitive development, painting a comprehensive picture of how children learn, adapt, and evolve.

1. Lev Vygotsky: A Russian psychologist, Vygotsky proposed the Sociocultural Theory, emphasising the significant influence of social interaction on cognitive development. His ideas resonate with Piaget's in the sense that both underscore the importance of active engagement in learning.

However, Vygotsky places a stronger emphasis on social factors in shaping cognitive schemas.

2. Erik Erikson: Erikson's theory of psychosocial developmentaligns with Piaget's ideas in its stage-based approach. While Piaget focuses on cognitive development, Erikson provides a broader view of social and emotional development, complementing the understanding of a child's evolving abilities.

3. Lawrence Kohlberg: Known for his stages of moral development, Kohlberg's work parallels Piaget's understanding of how children progress through distinct stages. Both theories underscore the idea that children's abilities and understanding evolve with time and experience.

5. Albert Bandura: Bandura's Social Learning Theoryposits that children learn by observing and imitating others. This theory aligns with Piaget's emphasis on active engagement in learning, but adds a social aspect to the learning process, complementing Piaget's focus on individual exploration and discovery.

6. Howard Gardner: Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences proposes that there are multiple ways to be intelligent, going beyond the traditional IQ concept. His theory doesn't directly align with Piaget's work, but offers a different lens to view cognitive abilities of children, thereby enriching our understanding of child development.

Assimilation and accommodation are the two core learning processes in Piaget's theory that explain how children acquire and modify knowledge through interaction with their environment. Children use schemas to understand new experiences by either assimilating information into existing schemas or accommodating by modifying schemas. Schemas evolve continuously as children interact with their environment.Schemas are mental frameworks that organise and interpret information in Piaget's cognitive development theory. Children use schemas to understand new experiences by either assimilating information into existing schemas or accommodating by modifying schemas. Schemas evolve continuously as children interact with their environment.

Schemas are mental frameworks that children use to organise and interpret information about the world. Children develop schemas through assimilation (fitting new experiences into existing schemas) and accommodation (modifying schemas when new information doesn't fit). For example, a child with a 'dog schema' might initially call all four-legged animals dogs, then accommodate by creating separate schemas for cats, horses, and other animals.

If we talk about learning as something that needs to be built then the idea of cognitive schemas makes perfect sense. These hidden worlds of the learner are what we as teachers are trying to develop. In many ways our ability to build on our schemas is a fundamental aspect of intelligence. This could be where metacognition plays a central role.

Piaget believes that a schema involves a category of knowledge and the procedure to obtain that knowledge. As individuals gain new experiences, the new information is modified, and gets added to, or alter pre-existing schemas.

Teachers can apply Piaget's theory in classrooms by aligning instructional methods with students' developmental stages and providing developmentally appropriate learning activities. Activities should encourage active exploration rather than passive reception, such as using manipulatives for math concepts or science experiments for hypothesis testing. Assessment should focus on understanding students' reasoning processes, not just right or wrong answers, to identify their current stage and design appropriate learning experiences.Teachers should match instruction to students' cognitive stages by providing hands-on, discovery-based learning for preoperational and concrete operational learners. Activities should encourage active exploration rather than passive reception, such as using manipulatives for math concepts or science experiments for hypothesis testing. Assessment should focus on understanding students' reasoning processes, not just right or wrong answers, to identify their current stage and design appropriate learning experiences.

Although, later researchers have demonstrated how Piaget's theory is applicable for learning and teaching but Piaget (1952) does not clearly relate his theory to learning.

Piaget was very influential in creating teaching practices and educational policy. For instance, in 1966 a primary education review by the UK government was based upon Piaget's theory. Also, the outcome of this review provided the foundation for publishing Plowden report (1967).

Discovery learning, the concept that children learn best through actively exploring and doing, was viewed as central to the primary school curriculum transformation.

Piaget believes that children must not be taught certain concepts until reaching the appropriate cognitive development stage. Also, accommodation and assimilation are requirements of an active learner only, because problem-solving skills must only be discovered they cannot be taught. The learning inside the classrooms must be student-centred and performed via active discovery learning. The primary role of an instructor is to facilitate learning, rather than direct teaching. Hence, teachers need to ensure the following practices within the classroom:

Here are a list of potential activities thatare designed to align with the cognitive abilities typical of each developmental stage according to Piaget's theory.

| Stage of Development | Activity |

|---|---|

| Sensorimotor Stage (Birth to ~2 years) | Playing peekaboo games to help the child understand object permanence. |

| Exploring different textures (soft, hard, rough, smooth) to stimulate sensory experiences. | |

| Preoperational Stage (~2 to 7 years) | Engaging in pretend play to encourage imagination and symbolic thinking. |

| Drawing or painting to encourage representation of objects and people. | |

| Concrete Operational Stage (~7 to 11 years) | Solving real-world problems using objects to facilitate understanding of conservation and reversibility. |

| Classifying objects by characteristics (colour, size, shape) to build logic and reasoning skills. | |

| Formal Operational Stage (11 years and up) | Discussing hypothetical scenarios to promote abstract thinking. |

| Encouraging debates or persuasive essays to develop skills in systematic planning and deductive reasoning. |

Piaget's theory helps teachers understand why students at different ages struggle with certain concepts and provides a framework for age-appropriate instruction. It explains why abstract concepts fail with younger children and why hands-on learning is essential in primary years. The theory's emphasis on active construction of knowledge supports modern constructivist teaching approaches and helps teachers interpret student errors as windows into their thinking processes.

Jean Piaget's contributions to the field of psychology have had profound and lasting implications for those working in child development. His pioneering work in cognitive development has provided a framework that informs educational practices, child psychology, and the broader scientific community. Here are seven of the most significant implications of Piaget's work for professionals in child development roles:

Piaget's legacy extends beyond theoretical contributions, offering practical guidance that supports teachers in child development roles to enhance their practise, support children's learning, and contribute to the advancement of scientific knowledge in developmental psychology.

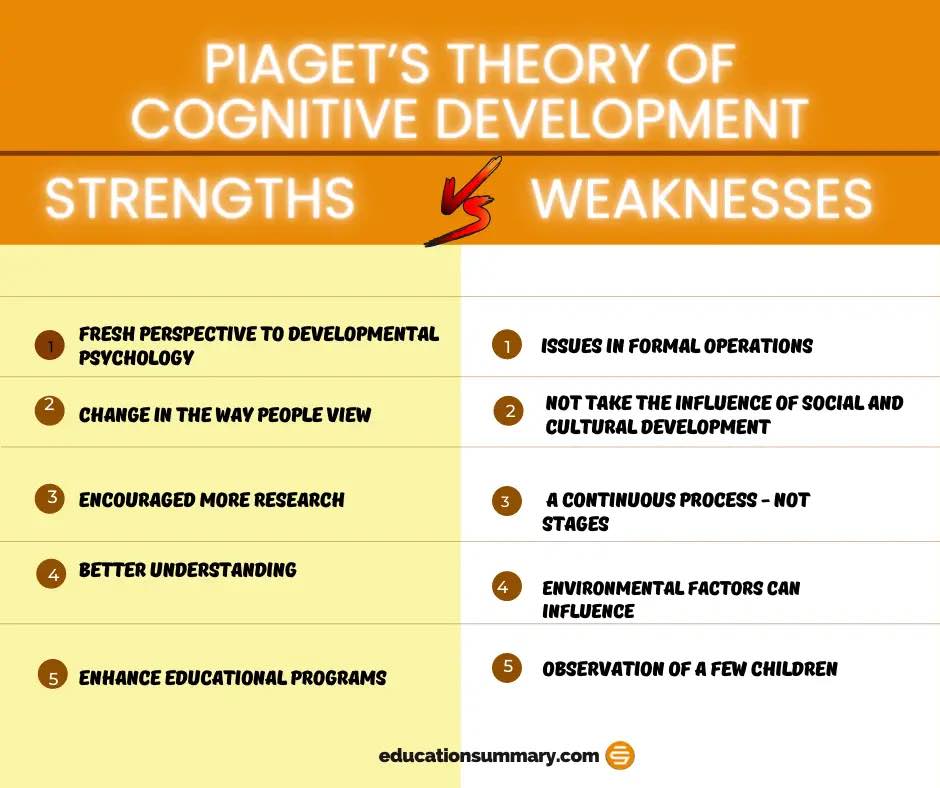

Piaget's theory faces criticism for underestimating children's cognitive abilities and overemphasising stage-based development. Critics argue that children demonstrate logical thinking earlier than Piaget suggested and that cultural factors significantly influence cognitive development. Modern research shows greater variability in developmental timelines than Piaget's fixed stages propose.

Critics argue that Piaget underestimated children's abilities and that development is more continuous than stage-like. Research shows children can demonstrate higher-level thinking earlier than Piaget suggested when tasks are simplified or made more relevant to their experience. Modern neuroscience also reveals that cognitive development varies more by individual and culture than Piaget's universal stages suggest.

Piaget's ideas have enormous influence on developmental psychology. His theories changed methods of teaching and changed people's perceptions about a child's world.

Piaget (1936) was the foremost psychologist whose ideas enhanced people's understanding of cognitive development. His concepts have been of practical use in communicating with and understanding children, specially in the field of education (Discovery Learning).

Piaget's main contributions include thorough observational studies of cognition in children, stage theory of children's cognitive development, and a series of ingenious but simple tests to evaluate multiple cognitive abilities.

Do stages really exist? Critiques of Formal Operation Thinking believe that the final stage of formal operations does not provide correct explanation of cognitive development. Not every person is capable of abstract reasoning and many adults do not even reach level of formal operations. For instance, Dasen (1994) mentioned that only less than half of adults ever reach the stage of formal operation. Maybe they are not distinct stages? Piaget was extremely focused on the universal stages of biological maturation and cognitive development that he failed to address the effect of culture and social setting on cognitive development.

Piaget's conservation experiments demonstrate how children in different stages understand that quantity remains constant despite changes in appearance, using tasks with water, clay, and coins. His Three Mountains Task reveals preoperational children's egocentrism by showing they cannot imagine perspectives different from their own. The pendulum problem illustrates formal operational thinking, where adolescents systematically test variables to determine what affects swing speed.

Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development has profoundly influenced the field of developmental psychology, offering a comprehensive framework for understanding how children develop cognitive structures and mental stages. His work on human development, including his four stages of cognitive growth, has been widely discussed and critiqued in academic literature. Below are five key studies exploring Piaget's theory, each providing insights into different aspects of his work and its implications for education and developmental psychology.

1. Barrouillet, P. (2015). Theories of cognitive development: From Piaget to today. Developmental Review, 38, 1-12.

Summary: This study revisits Piaget's cognitive developmental theory and examines its evolution over the past four decades. It highlights how contemporary developmental psychology has built upon and diverged from Piaget's original constructs, particularly in understanding cognitive structures and human development.

2. Sidik, F. (2020). Actualization of Jean Piaget's Cognitive Development Theoryin Learning. JURNAL PAJAR (Pendidikan dan Pengajaran).

Summary: This article explores the application of Piaget's theory in modern educational settings, emphasising the importance of aligning teaching methods with students' developmental stages. It underscores the theory's influence on effective educational practices and the understanding of child development.

Summary: Xiao's paper discusses the practical applications of Piaget's stages of cognitive development in classroom teaching. It provides examples of how teachers can design lesson content and methodologies that align with students' cognitive stages, enhancing their classroom activities.

4. Sanghvi, P. (2020). Piaget's theory of cognitive development: A review. International Journal of Modern Humanities, 7, 90-96.

Summary: Sanghvi provides a comprehensive review of Piaget's theory, detailing the four cognitive stages and their characteristics. The article also critiques Piaget's contributions to developmental psychology and discusses their educational implications, particularly for understanding cognitive structures.

5. Ghazi, S., Khan, U., Shahzada, G., & Ullah, K. (2014). Formal Operational Stage of Piaget's Cognitive Development Theory: An Implication in Learning Mathematics. Journal of Educational Research, 17, 71.

Summary: This study examines the application of Piaget's formal operational stage in teaching mathematics. It highlights how understanding cognitive stages can improve instructional strategies and enhance students' problem-solving and scientific inquiry skills, thus bridging knowledge gaps in math education.

These studies collectively emphasise the enduring relevance of Piaget's theory in educational psychology, providing valuable insights into how his ideas can be applied to improve teaching and learning processes.

Parents, educators, and students frequently ask questions about Piaget's cognitive development stages, particularly regarding age ranges, characteristics of each stage, and practical applications in education and child-rearing. This framework helps educators understand that children think in fundamentally different ways than adults and process information differently at each stage. It provides crucial insights for designing age-appropriate activities and interpreting children's responses in the classroom.Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development explains how children actively construct their understanding of the world through four distinct stages from birth to adolescence: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational. This framework helps educators understand that children think in fundamentally different ways than adults and process information differently at each stage. It provides crucial insights for designing age-appropriate activities and interpreting children's responses in the classroom.

Teachers can identify cognitive stages by observing specific behaviours such as object permanence in the sensorimotor stage, symbolic thinking in the preoperational stage, understanding of conservation in the concrete operational stage, and hypothetical reasoning in the formal operational stage. These observable behaviours reveal each child's cognitive readiness and help teachers pitch lessons appropriately. The article emphasises creating a 'Stage Assessment Toolkit' to master these indicators for better lesson planning.

Piaget discovered that children's mistakes are not failures but reveal unique ways of reasoning and provide clues to how their minds develop. These 'wrong' answers follow consistent patterns that show children are thinking in fundamentally different ways appropriate to their developmental stage. Teachers can use these insights to design differentiated hands-on tasks rather than simply correcting errors.

The preoperational stage (2-7 years) involves children using symbols and language but lacking logical operations, which the article calls 'the preoperational trap'. Children at this stage think symbolically but cannot yet perform concrete logical operations. Teachers need to understand that misunderstanding symbolic thought in Years 1-2 can lead to frustrated learners, so they must adapt their approaches specifically for this crucial developmental phase.

Piaget's framework shows that children are active learners who construct knowledge through interaction and discovery rather than passively absorbing information. The theory demonstrates exactly why discovery-based approaches work and when direct instruction can backfire. This supports moving beyond passive learning to create 'Active Construction Classrooms' where children learn through experience and exploration.

No, children cannot skip stages according to Piaget's theory, as each stage builds on the previous one and represents a fundamentally different way of processing information. This means teachers must ensure children have mastered the cognitive skills of their current stage before introducing concepts from higher stages. Understanding this progression helps educators avoid frustrating children with developmentally inappropriate tasks.

Teachers can use Piaget's stage-based approach to design activities that match children's evolving cognitive abilities, from sensory exploration for younger children to abstract reasoning tasks for adolescents. The theory provides a framework for understanding how core concepts like time, number, and fairness gradually emerge at different stages. This enables teachers to create developmentally appropriate learning experiences that align with children's natural cognitive progression.

Conservation tasks assess children's ability to understand that quantities remain constant despite changes in appearance, marking their entry into Piaget's concrete operational stage of cognitive development. When children encounter new information that conflicts with existing schemas, disequilibrium occurs, prompting cognitive growth. Equilibration drives progression through Piaget's four developmental stages.Equilibration is the process of balancing assimilation and accommodation to achieve cognitive stability in Piaget's theory. When children encounter new information that conflicts with existing schemas, disequilibrium occurs, prompting cognitive growth. Equilibration drives progression through Piaget's four developmental stages.

Piaget's theory rests on four interconnected mechanisms that explain how children actively transform their understanding of the world: schemas, assimilation, accommodation, and equilibration. These processes work together as children encounter new experiences, creating a dynamic system of learning that goes far beyond simple memorisation. Understanding these mechanisms transforms how educators interpret pupil responses and design learning experiences.

Schemas serve as mental blueprints that children use to organise and interpret information. A young child might develop a "dog schema" that includes four legs, fur, and barking. When this child encounters a cat, they face a cognitive challenge that activates Piaget's other mechanisms. Assimilation occurs when new information fits into existing schemas, whilst accommodation happens when schemas must be modified or created to handle contradictory information. This distinction proves crucial in classroom settings, as Wellington (2006) notes in his analysis of secondary education concepts, where teachers must recognise when pupils are struggling to accommodate new ideas that conflict with their existing mental models.

Equilibration, the drive to maintain cognitive balance, motivates learning when children experience disequilibrium, that uncomfortable feeling when new information doesn't fit existing schemas. Recent research by Kania et al. (2025) on preservice mathematics teachers reveals how cognitive obstacles emerge when learners cannot effectively accommodate abstract algebraic concepts into their existing numerical schemas. This finding underscores why rushing through mathematical concepts without allowing time for schema modification leads to persistent misconceptions.

In physics education, where abstract concepts frequently challenge existing schemas, Sari et al. (2025) demonstrate that integrating cognitive science principles with practical applications significantly improves both high-order thinking skills and science literacy. Their systematic review reveals that when teachers explicitly address schema construction and modification, pupils move beyond rote memorisation to genuine conceptual understanding. For instance, when teaching forces, acknowledging pupils' existing "push-pull" schemas before introducing Newton's laws allows for more effective accommodation of complex concepts.

Practical application of these concepts transforms daily teaching. During a Year 3 science lesson on plants, rather than correcting a pupil who insists "all plants have flowers," recognise this as an incomplete schema requiring accommodation. Guide discovery through examining ferns, mosses, and conifers, allowing the cognitive conflict to drive schema modification. Track equilibration by observing pupils' questions and confusions, these indicate active schema reconstruction rather than passive acceptance. Create "schema mapping" activities where pupils draw concept webs before and after lessons, making their cognitive development visible and celebrating the messy, non-linear nature of genuine learning.

Understanding the precise cognitive abilities that emerge at each developmental stage transforms how teachers recognise learning readinessand design appropriate activities. Each of Piaget's four stages contains landmark achievements that signal fundamental shifts in how children process information, solve problems, and understand their world. These milestones serve as observable markers that help educators identify where pupils are in their cognitive process, rather than simply relying on chronological age.

The sensorimotor stage (0-2 years) centres on the development of object permanence, where infants gradually understand that objects continue to exist even when hidden from view. This milestone typically emerges around 8 months and marks the beginning of mental representation. In the preoperational stage (2-7 years), children develop symbolic thinking but struggle with conservation tasks, believing that pouring water from a short, wide glass into a tall, thin one changes the amount of water. This stage also features pronounced egocentrism, where children cannot easily adopt another person's perspective, as demonstrated in Piaget's famous three-mountain task.

The concrete operational stage (7-11 years) brings revolutionary changes in logical thinking. Children master conservation, understand reversibility, and can classify objects along multiple dimensions simultaneously. Recent research by Yan Qiu (2025) highlights how cognitive conflict during this stage can be used to develop critical thinking skills, particularly in reading comprehension. When children encounter ideas that challenge their existing schemas, they must actively reconstruct their understanding, a process that mirrors Piaget's concepts of assimilation and accommodation. This finding suggests that deliberately introducing age-appropriate cognitive conflicts can accelerate intellectual development.

The formal operational stage (11+ years) introduces abstract reasoning and hypothetical thinking. Adolescents can now manipulate ideas mentally without concrete objects, solve problems systematically, and think about thinking itself (metacognition). However, not all individuals fully develop formal operational thinking, and cultural factors significantly influence its emergence. Understanding these stage-specific characteristics helps explain why certain teaching methods succeed or fail at different developmental levels.

For classroom practise, teachers can use these milestones as assessment checkpoints. In Key Stage 1, observe whether pupils can engage in pretend play (symbolic thinking) but struggle when asked to see situations from a classmate's viewpoint (egocentrism). In Key Stage 2, test conservation understanding by having pupils predict and explain what happens when clay balls are reshaped. For secondary students, introduce abstract concepts through concrete examples first, then gradually remove the scaffolding as formal operational thinking develops. This stage-aware approach ensures that cognitive demands match developmental capabilities, reducing frustration and maximising learning potential.

Translating Piaget's stages into classroom practise requires more than recognising developmental milestones. Recent research emphasises adapting teaching methods to match children's cognitive readiness whilst avoiding the trap of rigid stage-based limitations. Subotnik et al. (2023) highlight that talent development frameworks must account for individual variations within developmental stages, suggesting that Piaget's theory serves best as a flexible guide rather than a prescriptive formula.

For sensorimotor learners in nursery settings, object permanence activities transform abstract concepts into tangible experiences. Hide-and-seek games with favourite toys build memory skills, whilst texture boards and sensory bins develop schema through physical exploration. These activities align with Piaget's emphasis on learning through direct interaction with the environment, where thinking literally happens through movement and sensation.

Preoperational stage pupils benefit from symbolic play integrated into core subjects. When teaching maths, use role-play shops where children handle toy money, bridging the gap between concrete objects and abstract numbers. For literacy, puppet shows allow pupils to explore perspective-taking despite their egocentric tendencies. Science lessons incorporating simple experiments, like growing beans in transparent containers, satisfy their curiosity whilst respecting their inability to reverse mental operations.

Teachers often misinterpret Piaget's stages as strict boundaries, leading to underestimation of pupils' capabilities. Research on gifted education (Subotnik et al., 2023) demonstrates that exceptional learners may display formal operational thinking years before the typical age range, necessitating differentiated approaches. Similarly, culturally relevant pedagogy research by Prayitno et al. (2024) reveals how cultural backgrounds influence cognitive development patterns, challenging universal stage assumptions.

Concrete operational pupils excel with hands-on classification activities that use their newfound logical thinking. Create maths centres where children sort objects by multiple attributes, progressing from simple colour sorting to complex Venn diagrams. Geography lessons using scale models of local areas help pupils understand conservation of distance and spatial relationships. History timelines with moveable cards allow exploration of sequential thinking without requiring abstract reasoning.

For formal operational learners, hypothesis-testing becomes central to engagement. Science practicals where pupils design their own experiments cultivate abstract thinking skills. Literature discussions exploring multiple interpretations of texts exercise their ability to consider hypothetical scenarios. Debates on ethical dilemmas in citizenship lessons harness their emerging capacity for abstract moral reasoning, though Li and Wu (2025) caution that even advanced cognitive tools require careful scaffolding to support genuine understanding rather than surface-level engagement.

The key insight for educators lies in recognising that Piaget's stages describe typical progressions, not rigid prescriptions. Effective teaching observes individual readiness cues rather than chronological age, using stage-appropriate activities as starting points whilst remaining alert to signs that pupils are ready for greater cognitive challenges. This flexible application ensures that Piaget's framework enhances rather than constrains learning opportunities.

Four essential cognitive development terms define Piaget's theory: schemas, assimilation, accommodation, and equilibration work as interconnected mechanisms explaining how children actively construct knowledge. These concepts, schemas, assimilation, accommodation, and equilibration, work together as a dynamic system that drives cognitive growth. Understanding these mechanisms transforms how educators interpret pupil responses and design learning experiences.Piaget's theory rests on four interconnected mechanisms that explain how children actively transform their understanding rather than passively absorbing information. These concepts, schemas, assimilation, accommodation, and equilibration, work together as a dynamic system that drives cognitive growth. Understanding these mechanisms transforms how educators interpret pupil responses and design learning experiences.

Schemas form the foundation of Piaget's framework, representing organised mental structures that children use to understand their world. Unlike static knowledge banks, schemas are living frameworks that constantly evolve through experience. A Year 2 pupil's schema for "dog" might initially include only their pet Labrador, but expands to encompass different breeds, sizes, and eventually abstract categories like "mammals". When children encounter new information, they either assimilate it into existing schemas or accommodate their schemas to fit the new data. Recent research by Kania et al. (2025) demonstrates how preservice mathematics teachers' persistent difficulties with abstract concepts often stem from inadequate schema development in earlier stages, highlighting the long-term impact of these foundational structures.

Equilibration, Piaget's most sophisticated concept, describes the self-regulating mechanism that drives cognitive development forwards. When children experience cognitive conflict between their existing schemas and new information, they enter a state of disequilibrium. This uncomfortable state motivates them to either assimilate the new information or accommodate their thinking. Wellington (2006) emphasises that this process explains why simply correcting errors rarely leads to deep understanding, pupils must actively resolve the conflict themselves. Consider a Year 4 pupil who believes heavier objects always fall faster. Dropping a feather and hammer in a vacuum chamber creates productive disequilibrium that standard textbook explanations cannot achieve.

These mechanisms reveal why certain teaching approaches succeed whilst others falter. Physics education research by Sari et al. (2025) shows that rote memorisation fails precisely because it bypasses the assimilation-accommodation cycle, preventing genuine schema development. Effective teachers orchestrate experiences that challenge existing schemas without overwhelming pupils' current cognitive capacity. For instance, when teaching fractions, presenting pizza-sharing scenarios activates and gradually extends pupils' division schemas rather than introducing abstract notation immediately. This approach respects the natural equilibration process whilst guiding it towards curriculum objectives. Teachers who understand these mechanisms recognise that pupil "mistakes" often reflect necessary transitional schemas rather than failures, transforming assessment from judgement to diagnosis.

Piaget's development theory emphasises individual cognitive construction through stages, whilst Vygotsky's theory prioritises social interaction and cultural tools as the primary drivers of cognitive development. Each stage features distinct characteristics that directly impact how children process information, solve problems, and interact with their environment. These aren't simply age brackets, they represent fundamentally different ways of thinking that require specific teaching strategies.Understanding the precise cognitive milestones within each of Piaget's stages transforms how teachers recognise learning readiness and adjust their instructional approaches. Each stage features distinct characteristics that directly impact how children process information, solve problems, and interact with their environment. These aren't simply age brackets, they represent fundamentally different ways of thinking that require specific teaching strategies.

During the sensorimotor stage (0-2 years), infants develop object permanence around 8 months, understanding that objects continue to exist when hidden. This milestone explains why peek-a-boo captivates babies and why separation anxiety peaks during this period. Teachers in early yearssettings can support this development through games that involve hiding and revealing objects, building the foundation for later symbolic thinking. The preoperational stage (2-7 years) introduces symbolic thought but reveals striking limitations. Children demonstrate egocentrism, struggling to see perspectives beyond their own, which explains why Year 1 pupils might insist the moon follows them home. They also lack conservation understanding, believing that pouring water into a taller, thinner glass creates "more" water. These aren't deficits to correct but natural cognitive states that inform how we present learning materials.

The concrete operational stage (7-11 years) marks a crucial shift where children master conservation and develop logical thinking about concrete objects. Research by Yan Qiu (2025) highlights how cognitive conflict, the discomfort when new information challenges existing beliefs, can effectively develop critical thinking skills during this stage. When Year 4 pupils discover that a flattened ball of clay weighs the same as a rolled one, this cognitive conflict drives deeper understanding. Teachers can deliberately create such conflicts through hands-on experiments that challenge preconceptions, encouraging the mental restructuring Piaget called accommodation.

The formal operational stage (11+ years) enables abstract reasoning and hypothetical thinking. Secondary pupils can now engage with "what if" scenarios and understand metaphors beyond literal interpretation. This explains why algebra becomes accessible around Year 7 and why literature analysis deepens in secondary school. However, not all adolescents reach this stage uniformly, which has significant implications for differentiation. Teachers observing pupils struggling with abstract concepts shouldn't assume lack of ability, they may simply need more concrete representations as cognitive bridges.

Recognising these stage-specific characteristics prevents common teaching missteps. Asking preoperational children to "imagine how your friend feels" frustrates both teacher and pupil when egocentrism naturally limits perspective-taking. Similarly, introducing abstract grammatical rules before the formal operational stage often results in rote memorisation rather than genuine understanding. Instead, teachers who align activities with cognitive capabilities see dramatically improved engagement: using physical manipulatives for maths until pupils demonstrate conservation readiness, or introducing historical empathy exercises only when formal operational thinking emerges. This stage-awareness transforms seemingly resistant learners into successful ones by matching instruction to their actual cognitive toolkit.

Jean Piaget was a Swiss psychologist who pioneered cognitive development theory by systematically studying how children's thinking processes evolve from birth through adolescence. Originally trained as a biologist, Piaget's fascination with molluscs led him to explore how organisms adapt to their environment; a perspective that later shaped his revolutionary approach to child psychology.Jean Piaget (1896-1980) transformed our understanding of how children think and learn through groundbreaking research that began in 1920s Switzerland. Originally trained as a biologist, Piaget's fascination with molluscs led him to explore how organisms adapt to their environment; a perspective that later shaped his revolutionary approach to child psychology.

Working at the Binet Institute in Paris, Piaget made his career-defining observation: children's incorrect answers on intelligence tests weren't random but followed predictable patterns based on age. This insight challenged the prevailing view that children were simply "mini-adults" with less knowledge. Instead, Piaget proposed that children think in fundamentally different ways at different developmental stages.

His methodology broke new ground by combining careful observation with clinical interviews. Rather than testing children in laboratories, Piaget observed his own three children in natural settings, documenting how they interacted with objects, solved problems, and developed language. This approach revealed that children actively construct knowledge through experience, not passive absorption.

For today's teachers, Piaget's background offers crucial insights. His biological training explains why he viewed learning as adaptation, helping us understand why pupils need time to assimilate new concepts. When teaching fractions in Year 4, for instance, students benefit from manipulating physical objects before moving to abstract representations, mirroring Piaget's observation methods. Similarly, his emphasis on children's reasoning processes reminds us to ask "How did you work that out?" rather than simply marking answers right or wrong. This approach transforms assessment from a judgement tool into a window into pupils' cognitive development, enabling more targeted support.

During the sensorimotor stage, infants and toddlers learn primarily through their senses and physical actions. Piaget observed that children in this stage develop from reflexive responses to purposeful experimentation, gradually building an understanding that objects exist even when out of sight, a concept known as object permanence.

The sensorimotor stage unfolds through six substages, beginning with simple reflexes (0-1 month) and progressing to early symbolic thought (18-24 months). Initially, babies engage with the world through sucking, grasping, and looking. By four months, they begin repeating pleasurable actions, such as shaking a rattle. Around eight months, intentional behaviour emerges; infants will move obstacles to reach desired toys, demonstrating early problem-solving abilities.

For early years practitioners, understanding this stage transforms how we structure learning environments. Rather than attempting verbal instruction, effective teaching involves creating rich sensory experiences. Setting up treasure baskets filled with natural materials of varying textures, weights, and temperatures allows infants to explore through touch and manipulation. Peek-a-boo games directly support object permanence development, whilst cause-and-effect toys like pop-up boxes help children understand their impact on the environment.

Research by Renée Baillargeon (1987) expanded Piaget's findings, revealing that object permanence may develop earlier than originally thought, sometimes by 3.5 months. This insight encourages practitioners to provide challenging materials even for very young infants. Simple activities like hiding toys under cloths or using transparent containers can scaffold this crucial cognitive milestone.

Understanding the sensorimotor stage helps explain why babies repeatedly drop objects from highchairs; they're conducting physics experiments, not being difficult. This perspective shift enables more patient, developmentally appropriate responses from caregivers and educators.

During the preoperational stage, children begin to represent the world through words, images, and drawings, marking a significant leap from the sensorimotor period. However, their thinking remains intuitive and egocentric, creating unique challenges and opportunities in the classroom.

The hallmark of this stage is symbolic function; children can now use one object to represent another. A cardboard box becomes a spaceship, a stick transforms into a magic wand, and marks on paper represent people and objects. This symbolic thinking enables pretend play, early literacy development, and mathematical understanding. Yet children at this stage struggle with logic and taking another person's perspective.

Three key characteristics define preoperational thinking. First, egocentrism means children cannot easily see situations from others' viewpoints. Second, centration causes them to focus on one aspect of a situation whilst ignoring others. Third, they lack conservation; they don't understand that quantity remains constant despite changes in appearance.

In practise, teachers can support preoperational learners through specific strategies. Use role-play activities to gradually develop perspective-taking skills; for instance, acting out stories where children play different characters helps them consider multiple viewpoints. When teaching maths concepts, provide hands-on materials rather than abstract symbols. Children need to physically manipulate objects before understanding numerical relationships.

Language development accelerates dramatically during this stage, but children often engage in collective monologues rather than true conversations. Circle time discussions work best when structured around concrete objects or shared experiences. Visual aids, props, and real-world examples help bridge the gap between their symbolic thinking and abstract concepts.

Understanding these limitations helps teachers set appropriate expectations and design effective learning experiences that honour children's current capabilities whilst gently expanding their cognitive horizons.

During the sensorimotor stage, infants and toddlers learn exclusively through their senses and physical actions. Piaget observed that babies don't yet have the ability to form mental representations; instead, they understand their world through touching, tasting, looking, listening, and moving. This stage spans from birth to approximately two years and represents the foundation of all future cognitive development.

The hallmark achievement of this stage is object permanence, typically developing around 8-12 months. Before this milestone, when you hide a toy under a blanket, the baby acts as though it has ceased to exist. Once object permanence develops, the child understands that objects continue to exist even when out of sight. This cognitive leap marks a crucial transition in how infants perceive their environment.

For early years practitioners, understanding the sensorimotor stage shapes effective provision. Create treasure baskets filled with natural materials of different textures, weights, and temperatures; wooden spoons, silk scarves, metal chains, and pine cones offer rich sensory exploration. During nappy changes or feeding times, maintain eye contact and use exaggerated facial expressions to support early social cognition. Simple games like peek-a-boo aren't just entertaining; they actively build understanding of object permanence.

Piaget identified six sub-stages within this period, each building upon the previous one. Reflexive behaviours (0-1 month) gradually give way to intentional actions (8-12 months), and finally to mental representation (18-24 months). By the end of this stage, toddlers begin using symbols, such as pretending a block is a phone, signalling their readiness to enter the preoperational stage. This progression from purely sensory exploration to symbolic thinking forms the bedrock of all subsequent learning.

The preoperational stage marks a dramatic shift in children's cognitive abilities as they begin to use language and symbols to represent their world. During this period, typically spanning Reception through Year 2, children develop the capacity for symbolic thought but still struggle with logical reasoning and perspective-taking.

Children in this stage display characteristic thinking patterns that directly impact classroom learning. They engage in parallel play rather than truly cooperative activities, struggle to see situations from others' viewpoints, and often attribute human qualities to inanimate objects. Their thinking remains egocentric; when asked why the sun shines, a preoperational child might respond "to keep me warm" rather than understanding it as a natural phenomenon affecting everyone.

Understanding these limitations helps teachers design more effective lessons. For instance, when teaching maths concepts, use concrete manipulatives before introducing abstract symbols. A Year 1 pupil learning addition benefits more from physically combining groups of counters than from memorising number facts. Similarly, role-play activities help develop perspective-taking skills; having children act out different characters in a story gradually builds their ability to understand multiple viewpoints.

Language development during this stage follows predictable patterns. Children move from using single words to complex sentences, but their understanding remains literal. Metaphors and abstract concepts often confuse them. When reading "The Gruffalo", preoperational children focus on the concrete details of the monster rather than understanding the mouse's clever deception strategy.

Teachers can support learning by providing hands-on experiences before introducing symbolic representations. When teaching about plant growth, let children plant seeds and observe changes before introducing diagrams or written explanations. This concrete-to-abstract progression aligns with their developing cognitive abilities and builds stronger conceptual understanding.

The concrete operational stage marks a significant leap in children's cognitive abilities. During these primary school years, pupils develop logical thinking skills that transform how they understand the world around them. Most notably, children master conservation; they finally grasp that water poured from a tall thin glass into a short wide glass remains the same amount, even though it looks different.

This stage introduces several crucial cognitive abilities. Children can now classify objects using multiple criteria simultaneously, such as sorting shapes by both colour and size. They understand reversibility, recognising that 3 + 4 = 7 means 7, 4 = 3. Seriation becomes possible too; pupils can arrange items in order from smallest to largest or lightest to darkest. These skills form the foundation for mathematical reasoning and scientific thinking.

In the classroom, concrete operational learners thrive with hands-on materials and real-world examples. When teaching fractions, use physical objects like pizza slices or chocolate bars that children can manipulate. For science lessons, conduct experiments where pupils predict outcomes, test hypotheses, and draw conclusions based on observable evidence. History timelines work brilliantly at this stage; children can sequence events logically and understand cause-and-effect relationships.

However, abstract concepts still pose challenges. While a Year 5 pupil might excel at solving maths problems with concrete numbers, they may struggle with algebra where letters represent unknown values. Teachers should bridge this gap by starting with tangible examples before gradually introducing more abstract ideas. Remember that "concrete" doesn't mean simplistic; these learners can tackle complex problems as long as they relate to real, observable phenomena.

Translating Piaget's theory into classroom practise requires moving beyond traditional worksheet activities to create learning experiences that match children's cognitive capabilities. Research by Subotnik et al. (2023) on talent development frameworks emphasises how understanding developmental readiness transforms educational outcomes, particularly when activities align with students' current cognitive stage. Rather than forcing abstract concepts onto preoperational learners or limiting formal operational thinkers to concrete examples, effective Piagetian practise involves crafting stage-appropriate challenges that promote genuine cognitive growth.

For sensorimotor and early preoperational learners, successful activities centre on manipulative materials and sensory exploration. Water play with measuring cups naturally introduces conservation concepts without requiring verbal explanation. Building with blocks develops spatial reasoning through direct manipulation, whilst sorting activities using real objects (not pictures) establish classification skills. These hands-on experiences create the foundation for later abstract thinking, as children physically construct their understanding before moving to mental representations.

Concrete operational learners thrive when abstract concepts connect to tangible experiences. Fractions become comprehensible through pizza-sharing scenarios, whilst scientific method emerges naturally from cooking experiments where children measure, mix, and observe results. History transforms from memorising dates to creating physical timelines using string and photographs. The key lies in providing concrete anchors for abstract ideas, allowing pupils to build mental operations from real-world foundations. As Prayitno et al. (2024) note regarding culturally relevant pedagogy, incorporating students' lived experiences into these concrete examples significantly enhances comprehension and engagement.

Formal operational thinkers require fundamentally different approaches that challenge hypothetical reasoning. Debate activities exploring "what if" scenarios in literature or history engage abstract thinking skills. Science lessons can introduce controlled experiments where students generate and test multiple hypotheses. Mathematical proofs and philosophical discussions become accessible as learners manipulate ideas mentally without requiring physical props. Recent research by Li and Wu (2025) suggests that digital tools, including large language models, can support formal operational thinking by providing platforms for exploring complex hypothetical scenarios and receiving immediate feedback on logical reasoning.

The most effective Piagetian classrooms recognise that developmental stages aren't rigid boundaries but flexible frameworks. Mixed-ability groups benefit from activities with multiple entry points: a bridge-building challenge allows preoperational children to explore balance through trial and error, concrete operational learners to systematically test weight distribution, and formal operational students to calculate load-bearing ratios. This differentiated approach ensures all pupils work within their zone of proximal development whilst observing more advanced thinking strategies modelled by peers, naturally scaffolding cognitive growth through collaborative discovery.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Theory Of Cognitive Development By Jean Piaget

74 citations

Farida Hanum Pakpahan & Marice Saragih (2022)

This paper provides an overview of Piaget's four stages of cognitive development (sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational) and their impact on understanding how children think and learn. Teachers can use this foundational knowledge to recognise that students at different ages have distinct cognitive capabilities, helping them design age-appropriate lessons and set realistic learning expectations for their classrooms.

Piaget's Theory and Stages of Cognitive Development- An Overview

37 citations

Rabindran & Darshini Madanagopal (2020)

This review explains Piaget's core concepts of assimilation and accommodation, which describe how children integrate new information with existing knowledge and adjust their thinking when faced with conflicting information. Teachers benefit from understanding these processes because they reveal how students actively construct knowledge through experience, suggesting that hands-on learning activities and opportunities for discovery are essential for effective teaching.

Piaget’s Cognitive Developmental Theory: Critical Review

112 citations

Z. Babakr et al. (2019)

This paper examines both the significant contributions and limitations of Piaget's theory, acknowledging that while his stage-based model has greatly influenced developmental psychology, it has not been universally accepted or fully validated. Teachers should understand that Piaget's stages provide a useful framework but may not apply rigidly to every student, encouraging educators to remain flexible and consider individual differences in cognitive development.

Practical Application of Piaget’s Cognitive Theory and Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory in Classroom Pedagogy

3 citations

Michael Kwarteng (2025)

This study bridges theory and practise by examining how teachers can actually implement Piaget's cognitive development principles and Vygotsky's sociocultural theory in their daily instruction and classroom environment. Teachers will find this particularly valuable because it moves beyond abstract concepts to provide concrete guidance on aligning teaching strategies with developmental theories, helping them create more effective learning experiences that match students' cognitive abilities and social learning needs.

Estudo sobre a Teoria da Aprendizagem de Jean Piaget

2 citations

Cliciano Vieira da Silva et al. (2024)

This paper emphasises Piaget's key mechanisms of learning, including assimilation, accommodation, and equilibration, explaining how children actively construct knowledge rather than passively receive it. Teachers can apply these insights by creating learning environments that challenge students' existing understanding in productive ways, encouraging them to question, explore, and reorganize their thinking to achieve deeper comprehension.

Contextual Learning as a Means to Improve Elementary School Students' Mathematical Literacy Skills View study ↗

4 citations

R. A. Hidayana & Nestia Lianingsih (2025)

This research demonstrates how connecting math lessons to real-world contexts significantly improves elementary students' ability to solve practical mathematical problems, moving beyond traditional textbook exercises. The study is particularly valuable for teachers because it shows how Piaget's concrete operational stage can guide math instruction, helping educators design lessons that match how elementary students naturally think and learn. Teachers will find practical strategies for making math more meaningful and accessible to young learners.

Constructivist Approach to Language Learning: Linking Piaget's Theory to Modern Educational Practise View study ↗

9 citations

Lalu Idham & Halid (2024)

This study reveals how applying Piaget's constructivist principles to language teaching creates more engaging and effective learning experiences, where students actively build language skills through hands-on interaction rather than passive memorization. Teachers benefit from concrete examples of how to transform traditional language lessons into student-centred activities that align with natural cognitive development patterns. The research provides a bridge between educational theory and practical classroom techniques that can immediately improve student engagement and language acquisition.

Piano Enlightenment Education within Piaget's Theory of Children's Cognitive Development View study ↗

1 citations

Zhuying Li (2024)

This research explores how early childhood piano instruction can be designed around Piaget's developmental stages, offering age-appropriate teaching methods that match young children's cognitive abilities. Music educators and classroom teachers will appreciate the practical teaching strategies that respect children's natural learning progression, making music education more accessible and enjoyable for young learners. The study demonstrates how understanding cognitive development can transform specialised instruction, providing insights applicable to any subject area involving young children.

An Applied Analysis of Piaget's Theory in Cognitive Development and Educational Practise View study ↗

Shuyu Jiang (2025)

This comprehensive analysis shows teachers exactly how to translate Piaget's theoretical concepts into practical classroom strategies, including techniques for creating productive cognitive challenges and hands-on learning experiences. The research bridges the often confusing gap between educational theory and daily teaching practise, providing concrete examples that teachers can implement immediately. Educators will find valuable guidance on how to design lessons that naturally support students' cognitive growth while maintaining engagement and understanding.

The Learning Situation According to the Constructivist Theory and the Social Constructivist Theory in the Curricula of the Second Generation for Primary Education (From Conception to Application) View study ↗

Makhloufi Ali (2025)

This study examines how modern primary education curricula incorporate both Piaget's individual learning theory and Vygotsky's social learning approaches, providing teachers with a comprehensive framework for understanding how children learn best. The research emphasises why teachers need to understand these foundational theories to be truly effective in their classroom practise, rather than simply following curriculum guidelines without deeper understanding. Primary educators will gain valuable insights into balancing individual cognitive development with collaborative learning opportunities.