Learning Styles

Explore whether learning styles improve outcomes in education. Research suggests limited evidence for tailoring teaching to preferences.

Explore whether learning styles improve outcomes in education. Research suggests limited evidence for tailoring teaching to preferences.

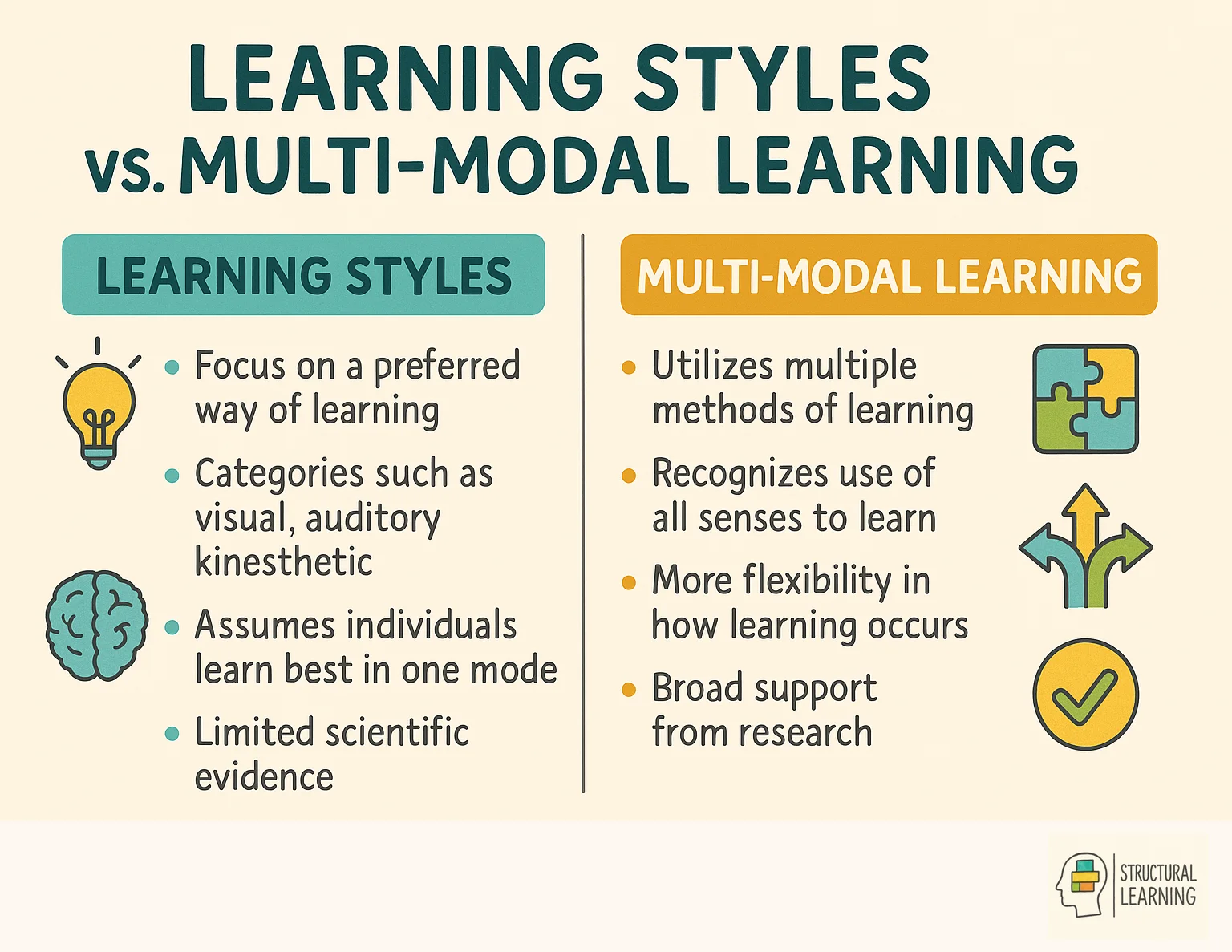

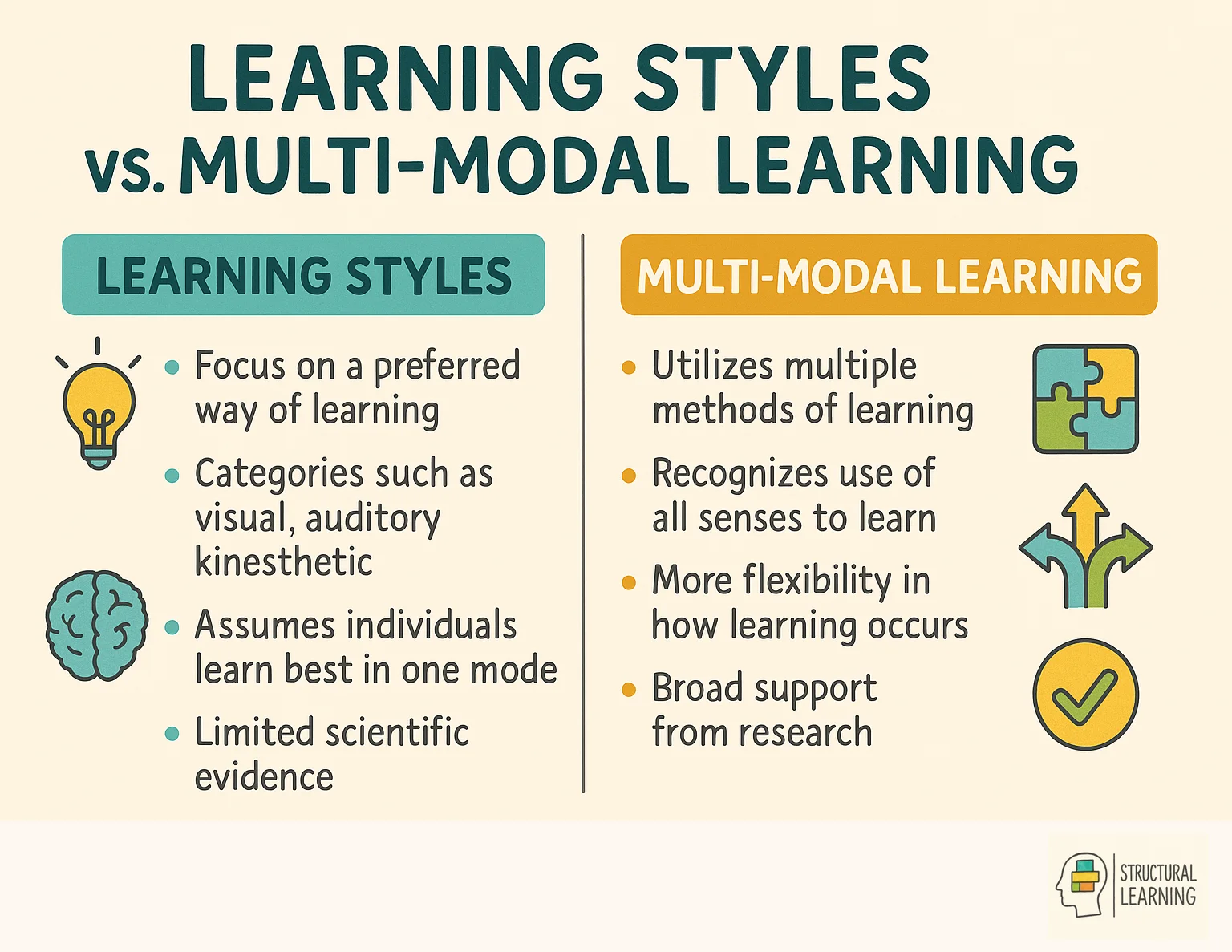

The concept of learning styles suggests that individuals learn best when taught according to their preferred sensory modality, most commonly visual, auditory, or . For example, a "visual learner" might be thought to benefit more from diagrams and charts, while an "auditory learner" might be better served by listening to explanations. This idea became particularly popular in the early 2000s and was widely embraced by schools and teacher training programmes.

However, despite its popularity, the empirical evidence supporting learning styles is limited. Numerous studies have failed to show that matching instruction to a learner's self-reported style leads to better outcomes. In fact, labelling students by type can be detrimental, potentially narrowing their learning experiences and undermining self-efficacy. As a result, the idea of learning styles has increasingly been classified as a neuromyth, a widely held belief not supported by robust or educational research.

That said, the debate is not entirely straightforward. The rise of , dual coding theory, and oracy-based learning has introduced compelling evidence that multi-modal and interactive learning experiences do have a significant impact on memory and understanding. These approaches, unlike learning styles, do not seek to categorise learne rs, but rather enrich learning by engaging multiple pathways in the brain.

In this article, we aim to unpack the theory of learning styles, explore the origins of its appeal, and clarify where it stands in light of current evidence. While some elements of the theory may overlap with sen, separate what feels intuitively right from what research supports.

Learning styles theory suggests that individuals have preferred sensory modalities for processing information, typically categorised as visual, auditory, or kinesthetic learners. The theory proposes that matching teaching methods to these preferences will improve learning outcomes and engagement. This concept gained widespread popularity in education during the early 2000s despite limited empirical support.

While the latest research implies that matching instructional techniques to the learning styles model has no impact on engagement, the theory of learning styles continues to be extremely popular.

Learning styles model are a well-known education and concept and are meant to specify how individuals show retention of material and the best of their learning.

The idea behind the theory is that to effectively utilise learning styles, also consider that align with each style. For example, students with an auditory learning style may benefit from recording lectures or reading aloud, while those with a kinesthetic learning style may prefer hands-on activities and interactive classroom experiences.

The concept implies to identify your own learning style through a Learning Style Inventory, which is a tool that assesses your preferred learning style. The inventory may include questions about your preferred study environment, how you process information, and what types of activities you enjoy.

Once you know your learning style, you can tailor your study strategies to better suit your individual needs and preferences. The theory being that this can lead to more effective learningand better .

have been developed based on the theory of learning styles. For example, teachers can incorporate visual aids for visual learners, hands-on activities for kinesthetic learners, and discussions for auditory learners. By understanding the background and theory of learning styles, educators can better cater to the diverse needs of their students and create a more inclusive

The VARK Model of Learning Styles

In 1987, Neil Fleming designed The VARK model of learning styles. According to The VARK model of learning styles, there are 4 basic styles of learning: auditory, visual, kinesthetic, and reading/writing.

Visual learnerstend to learn the best through pictures and other forms of vi suals. Teachers were encouraged to teach according to the students 'preferred Personal Preference' using graphic displays like diagrams, charts, videos, handouts, and illustrations.

It is because visual learners show retention of material through the learning process involving visual resources as visual learners would rather see knowledge provided in a visual form than in an auditory or written style.

Teachers may assess learner behaviour or carry out Learning Style Assessment and identify a student as a visual learner if the student has the following Study Habits:

The most effective teaching and retention of material occurs through these Visual Learning methods.

Auditory learners learn the best through sound and music. Auditory learners show better information retention by utilising sounds and recordings. The VARK model of learning would encourage teachers to identify students who are auditory learners and let them make recordings of lessons that they can listen to at a later time.

Teachers may evaluate student conduct or transport outperforming our learning style assessment and identifying abits:

Kinaesthetic learners learn the best through touching and doing. Teachers can determine whether students are kinaesthetic learners when the students learn through physical activities, for example, through role-playing, hands-on activities, and physical movement.

It's the use of physical movement that makes these learners retain information and engage better with the learning process. According to the VARK model, kinesthetic learners would rather engage in physical activity than listen to a lecture or watch a video.

Teachers may evaluate student conduct or transport exceeding our learning style evaluation and determining abits:

Given the lack of empirical support for learning styles, what should teachers take away from this discussion? The key is to focus on providing a rich and varied learning environment that caters to different learning preferences without pigeonholing students into fixed categories.

Embrace multi-modal approaches that incorporate visual aids, auditory explanations, hands-on activities, and opportunities for discussion. Encourage students to explore different learning strategies and discover what works best for them, but avoid suggesting that they are limited to a particular "style." Promoting flexible and adaptable learning habits will serve students far better in the long run.

Rather than categorising students into learning style groups, focus on using multiple teaching methods because different content requires different approaches. For instance, teaching mathematical concepts benefits from visual representations, whilst developing listening skills requires auditory practice - regardless of students' supposed 'learning styles'.

Instead of asking 'What's this student's learning style?', ask 'What's the best way to teach this particular concept?' This shift moves attention from fixed student labels to flexible, content-appropriate instruction. Research by cognitive scientists like Daniel Willingham demonstrates that matching teaching methods to content type, rather than student preferences, leads to better learning outcomes.

Consider also that when students struggle, the solution isn't to identify their learning style, but to examine whether your instruction provides sufficient practice, clear explanations, and appropriate scaffolding. This evidence-based approach serves all students more effectively than learning style categorisation.

For educators seeking deeper understanding of learning science, several key resources provide evidence-based alternatives to learning styles theory. 'Why Don't Students Like School?' by Daniel Willingham offers accessible explanations of how students actually learn, grounded in cognitive science research. The Education Endowment Foundation's Teaching and Learning Toolkit provides comprehensive reviews of educational interventions, including learning styles, with clear evidence ratings to help teachers identify which approaches genuinely improve student outcomes.

Pashler, McDaniel, Rohrer, and Bjork's influential research paper 'Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence' provides a thorough academic review of learning styles research, whilst cognitive load theorists like John Sweller offer practical frameworks for designing effective instru ction based on how human memory actually functions. Research supports focusing on evidence-based teaching methods such as retrieval practice, spaced repetition, and dual coding theory, which demonstrate measurable benefits for student learning across diverse classroom contexts.

Despite the widespread popularity of learning styles theory in educational settings, research evidence consistently fails to support its effectiveness. Comprehensive reviews by researchers such as Pashler and colleagues (2008) found virtually no empirical evidence that matching teaching methods to preferred learning styles improves student outcomes. Similarly, Willingham's extensive analysis demonstrates that whilst students may express preferences for certain types of information presentation, these preferences do not translate into enhanced learning when instruction is tailored accordingly.

The persistence of learning styles theory in classroom practice appears to stem from its intuitive appeal rather than scientific rigour. Research supports the notion that different teaching methods work better for different content areas, but this relates to the nature of the material being taught rather than individual student characteristics. For instance, spatial information is naturally better conveyed through visual means, whilst sequential processes benefit from step-by-step verbal explanation, regardless of students' supposed learning preferences.

Educational practitioners can better serve their students by focusing on evidence-based teaching strategies that benefit all learners. Rather than categorising students into learning style groups, effective classroom practice involves employing varied instructional methods based on curriculum content, providing multiple pathways to understanding, and using formative assessment to adjust teaching approaches based on actual learning outcomes rather than perceived preferences.

Rather than focusing on supposed learning preferences, research supports several evidence-based approaches that genuinely enhance student learning outcomes. Cognitive load theory, developed by John Sweller, demonstrates how teachers can improve info rmation presentation by managing the mental effort required for learning. This involves breaking complex tasks into smaller components and providing worked examples before independent practice.

Similarly, retrieval practice and spaced repetition have robust empirical support for improving long-term retention. Hermann Ebbinghaus's pioneering research on memory, later refined by cognitive scientists like Henry Roediger, shows that students learn more effectively when they actively recall information rather than simply re-reading material. Teachers can implement this through regular low-stakes testing, flashcards, or brief recap activities.

In classroom practice, these approaches prove far more beneficial than tailoring content to perceived learning styles. Consider incorporating dual coding techniques that combine verbal and visual information for all students, as Allan Paivio's research suggests this enhances comprehension universally. Additionally, providing multiple examples and encouraging students to explain their reasoning aloud supports deeper understanding across diverse learners, regardless of their preferred modalities.

Despite decades of research, several persistent myths about learning styles continue to influence classroom practice. The most prevalent misconception is that students learn best when instruction matches their preferred learning style. However, extensive research consistently demonstrates that matching teaching methods to supposed learning preferences does not improve student outcomes. Pashler and colleagues' comprehensive review found no credible evidence supporting this matching hypothesis across hundreds of studies.

Another common myth suggests that students have fixed learning styles that determine their academic potential. This belief can inadvertently limit educational opportunities and create self-fulfiling prophecies. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that effective learning depends more on how information is structured and presented than on individual style preferences. Research supports the view that successful learning emerges from evidence-based teaching methods rather than personalised style accommodations.

For classroom practice, focus on proven educational approaches rather than learning style categorisation. Vary your teaching methods to present content through multiple channels, but do this because diverse instructional techniques benefit all learners, not because you're targeting specific styles. This approach ensures every student encounters information through different modalities whilst avoiding the trap of limiting learners to supposedly preferred methods.

The concept of learning styles suggests that individuals learn best when taught according to their preferred sensory modality, most commonly visual, auditory, or . For example, a "visual learner" might be thought to benefit more from diagrams and charts, while an "auditory learner" might be better served by listening to explanations. This idea became particularly popular in the early 2000s and was widely embraced by schools and teacher training programmes.

However, despite its popularity, the empirical evidence supporting learning styles is limited. Numerous studies have failed to show that matching instruction to a learner's self-reported style leads to better outcomes. In fact, labelling students by type can be detrimental, potentially narrowing their learning experiences and undermining self-efficacy. As a result, the idea of learning styles has increasingly been classified as a neuromyth, a widely held belief not supported by robust or educational research.

That said, the debate is not entirely straightforward. The rise of , dual coding theory, and oracy-based learning has introduced compelling evidence that multi-modal and interactive learning experiences do have a significant impact on memory and understanding. These approaches, unlike learning styles, do not seek to categorise learne rs, but rather enrich learning by engaging multiple pathways in the brain.

In this article, we aim to unpack the theory of learning styles, explore the origins of its appeal, and clarify where it stands in light of current evidence. While some elements of the theory may overlap with sen, separate what feels intuitively right from what research supports.

Learning styles theory suggests that individuals have preferred sensory modalities for processing information, typically categorised as visual, auditory, or kinesthetic learners. The theory proposes that matching teaching methods to these preferences will improve learning outcomes and engagement. This concept gained widespread popularity in education during the early 2000s despite limited empirical support.

While the latest research implies that matching instructional techniques to the learning styles model has no impact on engagement, the theory of learning styles continues to be extremely popular.

Learning styles model are a well-known education and concept and are meant to specify how individuals show retention of material and the best of their learning.

The idea behind the theory is that to effectively utilise learning styles, also consider that align with each style. For example, students with an auditory learning style may benefit from recording lectures or reading aloud, while those with a kinesthetic learning style may prefer hands-on activities and interactive classroom experiences.

The concept implies to identify your own learning style through a Learning Style Inventory, which is a tool that assesses your preferred learning style. The inventory may include questions about your preferred study environment, how you process information, and what types of activities you enjoy.

Once you know your learning style, you can tailor your study strategies to better suit your individual needs and preferences. The theory being that this can lead to more effective learningand better .

have been developed based on the theory of learning styles. For example, teachers can incorporate visual aids for visual learners, hands-on activities for kinesthetic learners, and discussions for auditory learners. By understanding the background and theory of learning styles, educators can better cater to the diverse needs of their students and create a more inclusive

The VARK Model of Learning Styles

In 1987, Neil Fleming designed The VARK model of learning styles. According to The VARK model of learning styles, there are 4 basic styles of learning: auditory, visual, kinesthetic, and reading/writing.

Visual learnerstend to learn the best through pictures and other forms of vi suals. Teachers were encouraged to teach according to the students 'preferred Personal Preference' using graphic displays like diagrams, charts, videos, handouts, and illustrations.

It is because visual learners show retention of material through the learning process involving visual resources as visual learners would rather see knowledge provided in a visual form than in an auditory or written style.

Teachers may assess learner behaviour or carry out Learning Style Assessment and identify a student as a visual learner if the student has the following Study Habits:

The most effective teaching and retention of material occurs through these Visual Learning methods.

Auditory learners learn the best through sound and music. Auditory learners show better information retention by utilising sounds and recordings. The VARK model of learning would encourage teachers to identify students who are auditory learners and let them make recordings of lessons that they can listen to at a later time.

Teachers may evaluate student conduct or transport outperforming our learning style assessment and identifying abits:

Kinaesthetic learners learn the best through touching and doing. Teachers can determine whether students are kinaesthetic learners when the students learn through physical activities, for example, through role-playing, hands-on activities, and physical movement.

It's the use of physical movement that makes these learners retain information and engage better with the learning process. According to the VARK model, kinesthetic learners would rather engage in physical activity than listen to a lecture or watch a video.

Teachers may evaluate student conduct or transport exceeding our learning style evaluation and determining abits:

Given the lack of empirical support for learning styles, what should teachers take away from this discussion? The key is to focus on providing a rich and varied learning environment that caters to different learning preferences without pigeonholing students into fixed categories.

Embrace multi-modal approaches that incorporate visual aids, auditory explanations, hands-on activities, and opportunities for discussion. Encourage students to explore different learning strategies and discover what works best for them, but avoid suggesting that they are limited to a particular "style." Promoting flexible and adaptable learning habits will serve students far better in the long run.

Rather than categorising students into learning style groups, focus on using multiple teaching methods because different content requires different approaches. For instance, teaching mathematical concepts benefits from visual representations, whilst developing listening skills requires auditory practice - regardless of students' supposed 'learning styles'.

Instead of asking 'What's this student's learning style?', ask 'What's the best way to teach this particular concept?' This shift moves attention from fixed student labels to flexible, content-appropriate instruction. Research by cognitive scientists like Daniel Willingham demonstrates that matching teaching methods to content type, rather than student preferences, leads to better learning outcomes.

Consider also that when students struggle, the solution isn't to identify their learning style, but to examine whether your instruction provides sufficient practice, clear explanations, and appropriate scaffolding. This evidence-based approach serves all students more effectively than learning style categorisation.

For educators seeking deeper understanding of learning science, several key resources provide evidence-based alternatives to learning styles theory. 'Why Don't Students Like School?' by Daniel Willingham offers accessible explanations of how students actually learn, grounded in cognitive science research. The Education Endowment Foundation's Teaching and Learning Toolkit provides comprehensive reviews of educational interventions, including learning styles, with clear evidence ratings to help teachers identify which approaches genuinely improve student outcomes.

Pashler, McDaniel, Rohrer, and Bjork's influential research paper 'Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence' provides a thorough academic review of learning styles research, whilst cognitive load theorists like John Sweller offer practical frameworks for designing effective instru ction based on how human memory actually functions. Research supports focusing on evidence-based teaching methods such as retrieval practice, spaced repetition, and dual coding theory, which demonstrate measurable benefits for student learning across diverse classroom contexts.

Despite the widespread popularity of learning styles theory in educational settings, research evidence consistently fails to support its effectiveness. Comprehensive reviews by researchers such as Pashler and colleagues (2008) found virtually no empirical evidence that matching teaching methods to preferred learning styles improves student outcomes. Similarly, Willingham's extensive analysis demonstrates that whilst students may express preferences for certain types of information presentation, these preferences do not translate into enhanced learning when instruction is tailored accordingly.

The persistence of learning styles theory in classroom practice appears to stem from its intuitive appeal rather than scientific rigour. Research supports the notion that different teaching methods work better for different content areas, but this relates to the nature of the material being taught rather than individual student characteristics. For instance, spatial information is naturally better conveyed through visual means, whilst sequential processes benefit from step-by-step verbal explanation, regardless of students' supposed learning preferences.

Educational practitioners can better serve their students by focusing on evidence-based teaching strategies that benefit all learners. Rather than categorising students into learning style groups, effective classroom practice involves employing varied instructional methods based on curriculum content, providing multiple pathways to understanding, and using formative assessment to adjust teaching approaches based on actual learning outcomes rather than perceived preferences.

Rather than focusing on supposed learning preferences, research supports several evidence-based approaches that genuinely enhance student learning outcomes. Cognitive load theory, developed by John Sweller, demonstrates how teachers can improve info rmation presentation by managing the mental effort required for learning. This involves breaking complex tasks into smaller components and providing worked examples before independent practice.

Similarly, retrieval practice and spaced repetition have robust empirical support for improving long-term retention. Hermann Ebbinghaus's pioneering research on memory, later refined by cognitive scientists like Henry Roediger, shows that students learn more effectively when they actively recall information rather than simply re-reading material. Teachers can implement this through regular low-stakes testing, flashcards, or brief recap activities.

In classroom practice, these approaches prove far more beneficial than tailoring content to perceived learning styles. Consider incorporating dual coding techniques that combine verbal and visual information for all students, as Allan Paivio's research suggests this enhances comprehension universally. Additionally, providing multiple examples and encouraging students to explain their reasoning aloud supports deeper understanding across diverse learners, regardless of their preferred modalities.

Despite decades of research, several persistent myths about learning styles continue to influence classroom practice. The most prevalent misconception is that students learn best when instruction matches their preferred learning style. However, extensive research consistently demonstrates that matching teaching methods to supposed learning preferences does not improve student outcomes. Pashler and colleagues' comprehensive review found no credible evidence supporting this matching hypothesis across hundreds of studies.

Another common myth suggests that students have fixed learning styles that determine their academic potential. This belief can inadvertently limit educational opportunities and create self-fulfiling prophecies. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that effective learning depends more on how information is structured and presented than on individual style preferences. Research supports the view that successful learning emerges from evidence-based teaching methods rather than personalised style accommodations.

For classroom practice, focus on proven educational approaches rather than learning style categorisation. Vary your teaching methods to present content through multiple channels, but do this because diverse instructional techniques benefit all learners, not because you're targeting specific styles. This approach ensures every student encounters information through different modalities whilst avoiding the trap of limiting learners to supposedly preferred methods.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/learning-styles#article","headline":"Learning Styles","description":"Explore whether learning styles improve outcomes in education. Research suggests limited evidence for tailoring teaching to preferences.","datePublished":"2022-11-15T18:03:22.158Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/learning-styles"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/695265bff0d57128c38a8432_695265bd718a22a385624c5c_learning-styles-infographic.webp","wordCount":3313},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/learning-styles#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Learning Styles","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/learning-styles"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"Understanding Learning Styles: What Are They?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The concept of learning styles suggests that individuals learn best when taught according to their preferred sensory modality, most commonly visual, auditory, or . For example, a \"visual learner\" might be thought to benefit more from diagrams and charts, while an \"auditory learner\" might be better served by listening to explanations. This idea became particularly popular in the early 2000s and was widely embraced by schools and teacher training programmes."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Is the Theory Behind Learning Styles?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Learning styles theory suggests that individuals have preferred sensory modalities for processing information, typically categorised as visual, auditory, or kinesthetic learners. The theory proposes that matching teaching methods to these preferences will improve learning outcomes and engagement. This concept gained widespread popularity in education during the early 2000s despite limited empirical support."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"So, What Does This Mean for Teachers?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Given the lack of empirical support for learning styles, what should teachers take away from this discussion? The key is to focus on providing a rich and varied learning environment that caters to different learning preferences without pigeonholing students into fixed categories."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Does the Research Say About Learning Styles?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Despite the widespread popularity of learning styles theory in educational settings, research evidence consistently fails to support its effectiveness . Comprehensive reviews by researchers such as Pashler and colleagues (2008) found virtually no empirical evidence that matching teaching methods to preferred learning styles improves student outcomes. Similarly, Willingham's extensive analysis demonstrates that whilst students may express preferences for certain types of information presentation,"}}]}]}