Cognitive Distortions

Understanding Cognitive Distortions: Why Addressing Negative Thinking in the Classroom Supports Student Growth and Resilience

Understanding Cognitive Distortions: Why Addressing Negative Thinking in the Classroom Supports Student Growth and Resilience

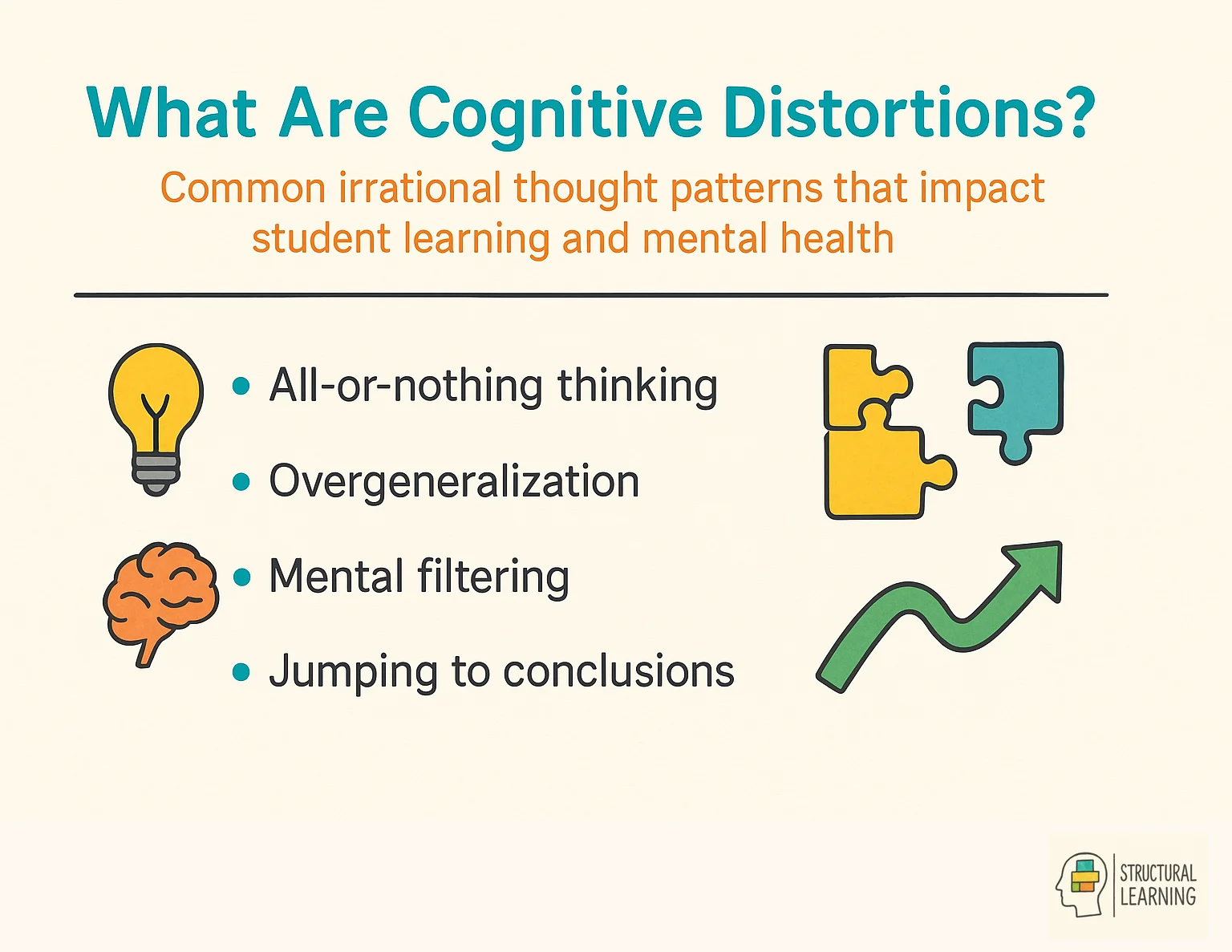

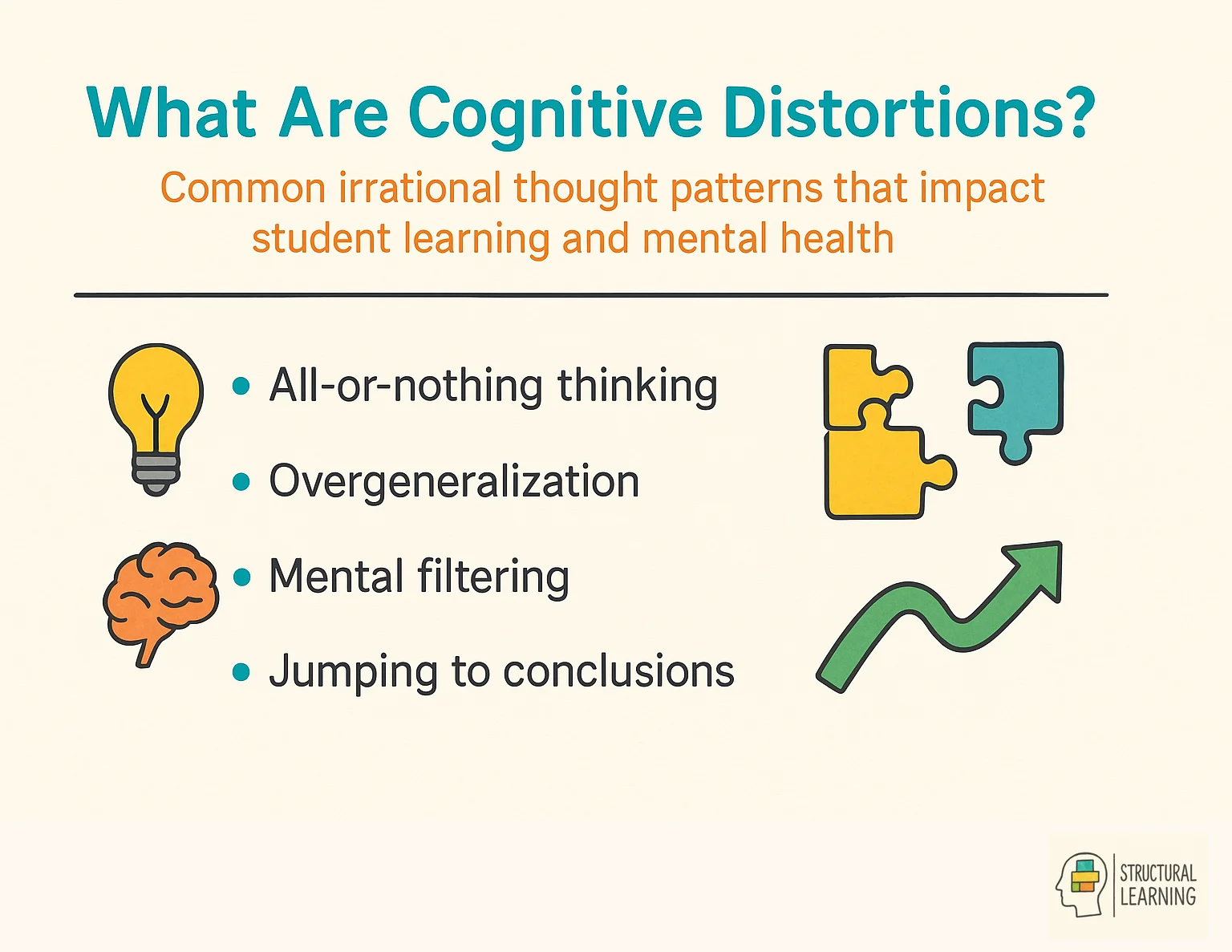

Cognitive distortions are irrational thoughts or biased perspectives that can have a significant impact on mental health. These distorted thinking patterns can lead to psychological damage, low self-esteem, and exacerbate symptoms of various mental illnesses.

These aren't just fleeting thoughts; they're deeply ingrained styles of thinking that can become the architects of our emotional turmoil. Understanding how cognitive skills develop is crucial for recognising these patterns. Take "Polarized Thinking," for instance, an extreme form of "black-and-white" or "Dichotomous Thinking," where the world is seen in absolutes, leaving no room for the nuanced shades of grey that define most of life. Or consider "Mental Filtering," a cognitive trap where only the negative details of a situation are magnified, while positive events are conveniently ignored or trivialized.

But it doesn't stop there. "Overgeneralization" is another culprit, a form of overgeneralization where one isolated incident is blown out of proportion to predict future events, often leading to sweeping and unfounded conclusions about oneself or others.

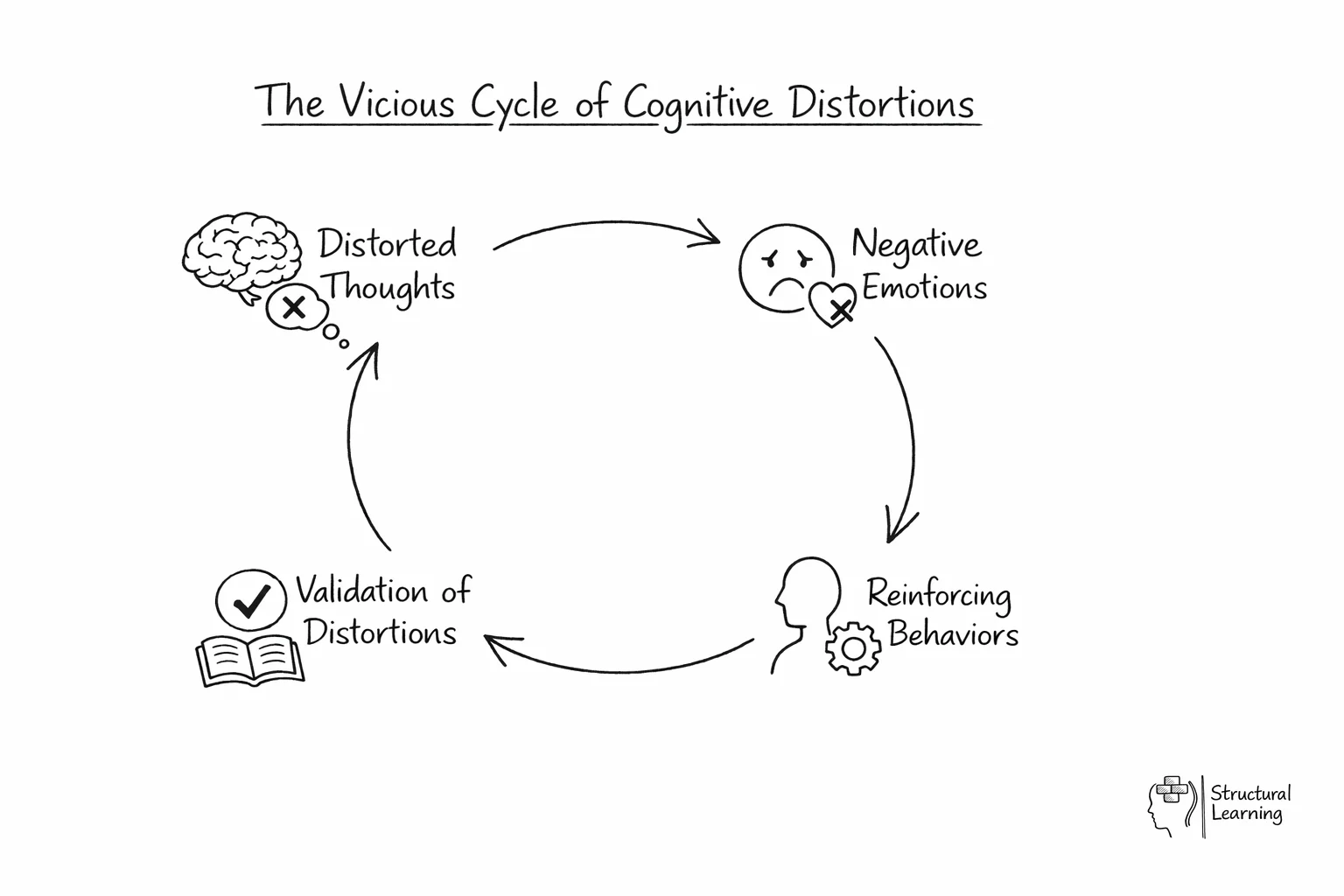

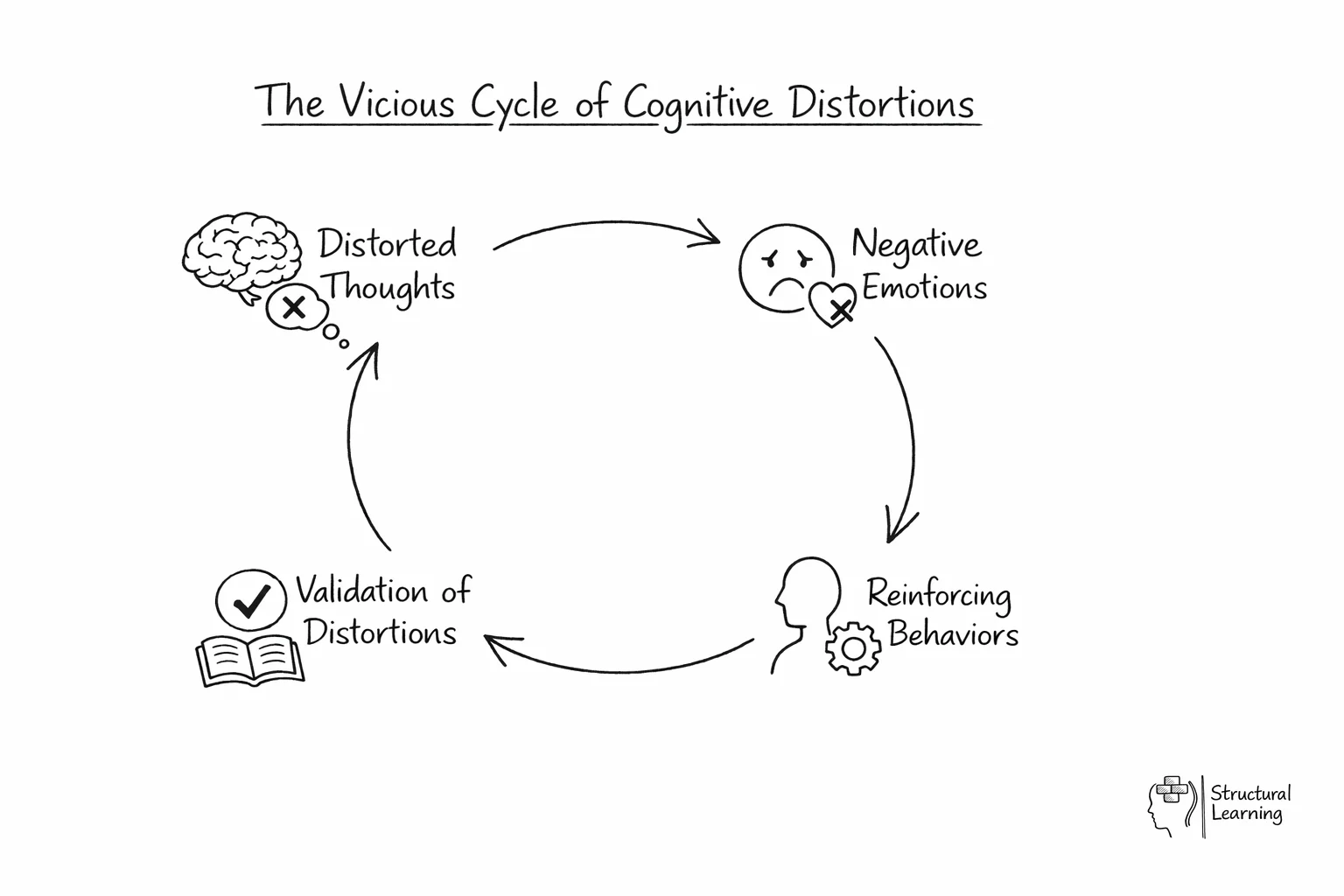

These errors in thinking can become self-fulfiling prophecies, reinforcing the very distortions that created them. The cycle is vicious: distorted thoughts lead to negative emotions, which in turn fuel behaviours that serve to validate and perpetuate these cognitive distortions.

The good news? While cognitive therapy, pioneered by psychologists like Aaron Beck and David Burns, has been instrumental in helping individuals recognise and challenge cognitive distortions, there are also many proactive steps that educators can take within the classroom to support students in reframing their thinking. Teachers play a vital role in breaking the cycle of negative self-perception by developing an environment that encourages resilience, self-reflection, and a growth mindset.

Simple classroom strategies, such as reinforcing positive self-talk, modelling cognitive reframing, encouraging reflective questioning, and providing constructive, strengths-based feedback, can help students recognise when they are engaging in distorted thinking. Activities that promote metacognition, such as journaling about learning experiences or discussing alternative perspectives, also helps students to become more aware of their thought patterns. Additionally, a supportive and inclusive classroom culture, where mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities rather than failure s, can help prevent these distortions from taking hold.

As we explore this topic further, we will examine both the psychological foundations of cognitive distortions and the practical, evidence-based strategies that teachers can use to help students develop healthier, more balanced ways of thinking. By integrating these approaches, educators can create a learning environment that not only addresses negative thinking but actively promotes confidence, curiosity, and resilience.

Key Insights:

The most common cognitive distortions include all-or-nothing thinking, mental filtering, overgeneralization, and catastrophizing. These distorted thinking patterns involve seeing situations in extremes, focusing only on negatives, making broad conclusions from single events, or expecting the worst outcomes. Understanding these patterns is the first step in helping students recognise and challenge their negative thought processes.

In his book, "Feeling Good Handbook" (1989), David Burns identified 11 common cognitive distortions that can affect our thinking patterns. These distorted thinking styles can have a significant impact on our emotions, behaviours, and overall mental well-being. Teachers who understand how to maintain attention and boost student engagement can better help students recognise these patterns. Here are the 11 common cognitive distortions with explanations and examples:

1. All-or-Nothing Thinking: This distortion involves believing that things are either all good or all bad, with no shades of grey. For example, thinking that getting a bad grade on an exam means you are a complete failure.

2. Overgeneralization: This distortion involves forming negative beliefs based on a single incident or piece of evidence. For example, believing that one rejection in a relationship means you will never find love.

3. Mental Filtering: With this distortion, individuals focus only on the negative details of a situation, while ignoring any positive aspects. Supporting self-regulated learning can help students recognise when they are engaging in mental filtering. For example, dwelling on a single criticism and dismissing numerous compliments. For example, dwelling on a single criticism and dismissing numerous compliments.

4. Disqualifying the Positive: This distortion involves rejecting positive experiences by insisting they don't count for some reason. For example, believing that getting a good grade was just luck and doesn't reflect your abilities.

5. Jumping to Conclusions: This distortion involves making negative interpretations or assumptions without sufficient evidence. There are two subtypes:

- Mind Reading: Assuming you know what others are thinking without checking it out. For example, assuming that your teacher thinks you're not trying hard enough.

- Fortune Telling: Predicting that things will turn out badly, without any realistic evidence. For example, believing you'll fail a test before you even start studying.

6. Magnification (Catastrophizing) or Minimization: This distortion involves exaggerating the importance of negative events or minimising the significance of positive ones. For example, blowing a small mistake out of proportion or downplaying your achievements.

7. Emotional Reasoning: This distortion involves believing that your negative feelings necessarily reflect the way things really are. For example, assuming that you must be worthless because you feel worthless.

8. "Should" Statements: This distortion involves using "should," "ought to," or "must" statements to motivate yourself, which can lead to feelings of guilt and frustration when you don't meet these expectations. For example, thinking you should always be the best student in the class.

9. labelling: This distortion involves assigning a negative label to yourself or others based on a single event or characteristic. For example, calling yourself a "loser" because you made a mistake.

10. Personalization: This distortion involves taking responsibility for negative events that are not entirely your fault. For example, blaming yourself for a classmate's bad mood.

11. Blame: Conversely, blame involves holding other people responsible for the pain you experience or taking the other tack and blaming yourself for every problem, instead of accepting that life experiences always involve many separate influences.

Understanding these cognitive distortions is essential, but applying this knowledge in the classroom is where teachers can make a real difference. Here are some practical strategies to help students challenge and reframe their negative thinking:

1. Promote Awareness: Educate students about cognitive distortions. Help them recognise these patterns in their own thoughts and behaviours through discussions and examples.

2. Encourage Self-Reflection: Use journaling and reflective exercises to help students identify and challenge their distorted thoughts. Guiding questions can prompt them to consider alternative perspectives and evidence.

3. Model Cognitive Reframing: Share your own experiences with challenging negative thoughts. Demonstrate how to identify and reframe distorted thinking patterns in everyday situations.

4. Provide Constructive Feedback: Offer specific, strengths-based feedback that focuses on effort and progress rather than fixed abilities. This helps students develop a growth mindset and challenge beliefs about their limitations.

5. Facilitate Group Discussions: Create a safe and supportive classroom environment where students can share their experiences and learn from one another. Encourage respectful dialogue and collaborative problem-solving.

6. Teach Coping Strategies: Equip students with practical coping strategies, such as deep breathing exercises, mindfulness techniques, and positive self-talk, to manage negative emotions and prevent distorted thinking.

7. Integrate Metacognitive Activities: Design learning activities that promote metacognition, encouraging students to reflect on their thinking processes and identify areas for im provement.

8. Use Visual Aids: Display posters or infographics that illustrate common cognitive distortions and strategies for challenging them. These visual reminders can help students stay aware of their thinking patterns.

By incorporating these strategies into your teaching practice, you can assist students in cultivating更为健康且平衡的生活方式 of thinking and build resilience in the face of challenges.

Cognitive distortions can significantly impact students' mental health and academic performance. By understanding these distorted thinking patterns and implementing practical strategies to challenge them, educators can create a supportive learning environment that creates resilience, self-awareness, and a growth mindset. Together, we can enable students to encourage更为健康且均衡的发展途径 of thinking, helping them to thrive both inside and outside the classroom.

Ultimately, addressing cognitive distortions is not just about improving students' mental well-being; it's about equipping them with essential life skills that will benefit them throughout their academic journey and beyond. By integrating these approaches into our educational practices, we can helps students to become more confident, curious, and resilient learners, ready to face any challenge with a positive and balanced mindset.

Cognitive distortions are irrational thoughts or biased perspectives that can have a significant impact on mental health. These distorted thinking patterns can lead to psychological damage, low self-esteem, and exacerbate symptoms of various mental illnesses.

These aren't just fleeting thoughts; they're deeply ingrained styles of thinking that can become the architects of our emotional turmoil. Understanding how cognitive skills develop is crucial for recognising these patterns. Take "Polarized Thinking," for instance, an extreme form of "black-and-white" or "Dichotomous Thinking," where the world is seen in absolutes, leaving no room for the nuanced shades of grey that define most of life. Or consider "Mental Filtering," a cognitive trap where only the negative details of a situation are magnified, while positive events are conveniently ignored or trivialized.

But it doesn't stop there. "Overgeneralization" is another culprit, a form of overgeneralization where one isolated incident is blown out of proportion to predict future events, often leading to sweeping and unfounded conclusions about oneself or others.

These errors in thinking can become self-fulfiling prophecies, reinforcing the very distortions that created them. The cycle is vicious: distorted thoughts lead to negative emotions, which in turn fuel behaviours that serve to validate and perpetuate these cognitive distortions.

The good news? While cognitive therapy, pioneered by psychologists like Aaron Beck and David Burns, has been instrumental in helping individuals recognise and challenge cognitive distortions, there are also many proactive steps that educators can take within the classroom to support students in reframing their thinking. Teachers play a vital role in breaking the cycle of negative self-perception by developing an environment that encourages resilience, self-reflection, and a growth mindset.

Simple classroom strategies, such as reinforcing positive self-talk, modelling cognitive reframing, encouraging reflective questioning, and providing constructive, strengths-based feedback, can help students recognise when they are engaging in distorted thinking. Activities that promote metacognition, such as journaling about learning experiences or discussing alternative perspectives, also helps students to become more aware of their thought patterns. Additionally, a supportive and inclusive classroom culture, where mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities rather than failure s, can help prevent these distortions from taking hold.

As we explore this topic further, we will examine both the psychological foundations of cognitive distortions and the practical, evidence-based strategies that teachers can use to help students develop healthier, more balanced ways of thinking. By integrating these approaches, educators can create a learning environment that not only addresses negative thinking but actively promotes confidence, curiosity, and resilience.

Key Insights:

The most common cognitive distortions include all-or-nothing thinking, mental filtering, overgeneralization, and catastrophizing. These distorted thinking patterns involve seeing situations in extremes, focusing only on negatives, making broad conclusions from single events, or expecting the worst outcomes. Understanding these patterns is the first step in helping students recognise and challenge their negative thought processes.

In his book, "Feeling Good Handbook" (1989), David Burns identified 11 common cognitive distortions that can affect our thinking patterns. These distorted thinking styles can have a significant impact on our emotions, behaviours, and overall mental well-being. Teachers who understand how to maintain attention and boost student engagement can better help students recognise these patterns. Here are the 11 common cognitive distortions with explanations and examples:

1. All-or-Nothing Thinking: This distortion involves believing that things are either all good or all bad, with no shades of grey. For example, thinking that getting a bad grade on an exam means you are a complete failure.

2. Overgeneralization: This distortion involves forming negative beliefs based on a single incident or piece of evidence. For example, believing that one rejection in a relationship means you will never find love.

3. Mental Filtering: With this distortion, individuals focus only on the negative details of a situation, while ignoring any positive aspects. Supporting self-regulated learning can help students recognise when they are engaging in mental filtering. For example, dwelling on a single criticism and dismissing numerous compliments. For example, dwelling on a single criticism and dismissing numerous compliments.

4. Disqualifying the Positive: This distortion involves rejecting positive experiences by insisting they don't count for some reason. For example, believing that getting a good grade was just luck and doesn't reflect your abilities.

5. Jumping to Conclusions: This distortion involves making negative interpretations or assumptions without sufficient evidence. There are two subtypes:

- Mind Reading: Assuming you know what others are thinking without checking it out. For example, assuming that your teacher thinks you're not trying hard enough.

- Fortune Telling: Predicting that things will turn out badly, without any realistic evidence. For example, believing you'll fail a test before you even start studying.

6. Magnification (Catastrophizing) or Minimization: This distortion involves exaggerating the importance of negative events or minimising the significance of positive ones. For example, blowing a small mistake out of proportion or downplaying your achievements.

7. Emotional Reasoning: This distortion involves believing that your negative feelings necessarily reflect the way things really are. For example, assuming that you must be worthless because you feel worthless.

8. "Should" Statements: This distortion involves using "should," "ought to," or "must" statements to motivate yourself, which can lead to feelings of guilt and frustration when you don't meet these expectations. For example, thinking you should always be the best student in the class.

9. labelling: This distortion involves assigning a negative label to yourself or others based on a single event or characteristic. For example, calling yourself a "loser" because you made a mistake.

10. Personalization: This distortion involves taking responsibility for negative events that are not entirely your fault. For example, blaming yourself for a classmate's bad mood.

11. Blame: Conversely, blame involves holding other people responsible for the pain you experience or taking the other tack and blaming yourself for every problem, instead of accepting that life experiences always involve many separate influences.

Understanding these cognitive distortions is essential, but applying this knowledge in the classroom is where teachers can make a real difference. Here are some practical strategies to help students challenge and reframe their negative thinking:

1. Promote Awareness: Educate students about cognitive distortions. Help them recognise these patterns in their own thoughts and behaviours through discussions and examples.

2. Encourage Self-Reflection: Use journaling and reflective exercises to help students identify and challenge their distorted thoughts. Guiding questions can prompt them to consider alternative perspectives and evidence.

3. Model Cognitive Reframing: Share your own experiences with challenging negative thoughts. Demonstrate how to identify and reframe distorted thinking patterns in everyday situations.

4. Provide Constructive Feedback: Offer specific, strengths-based feedback that focuses on effort and progress rather than fixed abilities. This helps students develop a growth mindset and challenge beliefs about their limitations.

5. Facilitate Group Discussions: Create a safe and supportive classroom environment where students can share their experiences and learn from one another. Encourage respectful dialogue and collaborative problem-solving.

6. Teach Coping Strategies: Equip students with practical coping strategies, such as deep breathing exercises, mindfulness techniques, and positive self-talk, to manage negative emotions and prevent distorted thinking.

7. Integrate Metacognitive Activities: Design learning activities that promote metacognition, encouraging students to reflect on their thinking processes and identify areas for im provement.

8. Use Visual Aids: Display posters or infographics that illustrate common cognitive distortions and strategies for challenging them. These visual reminders can help students stay aware of their thinking patterns.

By incorporating these strategies into your teaching practice, you can assist students in cultivating更为健康且平衡的生活方式 of thinking and build resilience in the face of challenges.

Cognitive distortions can significantly impact students' mental health and academic performance. By understanding these distorted thinking patterns and implementing practical strategies to challenge them, educators can create a supportive learning environment that creates resilience, self-awareness, and a growth mindset. Together, we can enable students to encourage更为健康且均衡的发展途径 of thinking, helping them to thrive both inside and outside the classroom.

Ultimately, addressing cognitive distortions is not just about improving students' mental well-being; it's about equipping them with essential life skills that will benefit them throughout their academic journey and beyond. By integrating these approaches into our educational practices, we can helps students to become more confident, curious, and resilient learners, ready to face any challenge with a positive and balanced mindset.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cognitive-distortions#article","headline":"Cognitive Distortions","description":"Understanding Cognitive Distortions: Why Addressing Negative Thinking in the Classroom Supports Student Growth and Resilience","datePublished":"2023-11-02T09:57:49.358Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cognitive-distortions"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69518b8ada687eeca87f7ad7_69518b88b910a03f742921bf_cognitive-distortions-infographic.webp","wordCount":4307},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cognitive-distortions#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Cognitive Distortions","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cognitive-distortions"}]}]}