Skinner's Theories

Explore B.F. Skinner's groundbreaking theories on behaviorism and their profound impact on child development and psychology in this insightful article.

Explore B.F. Skinner's groundbreaking theories on behaviorism and their profound impact on child development and psychology in this insightful article.

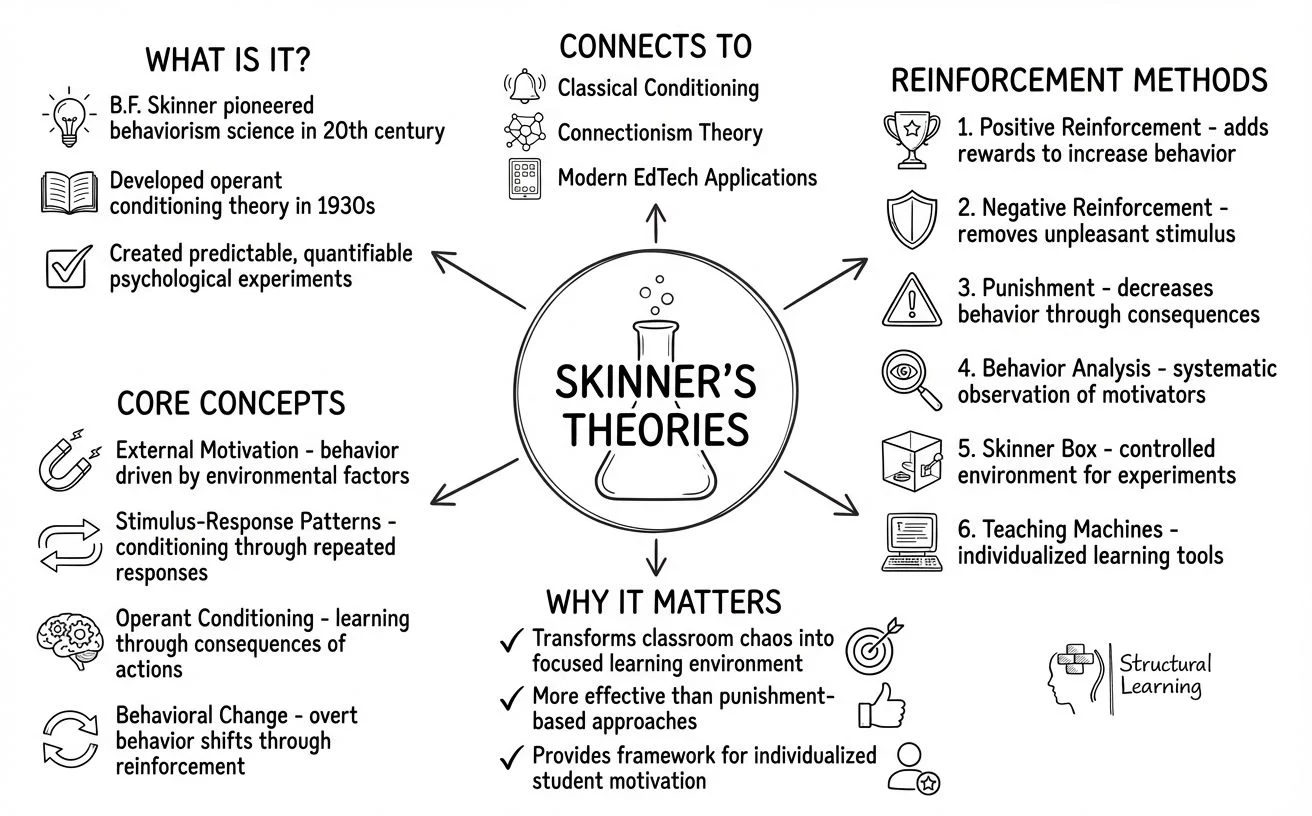

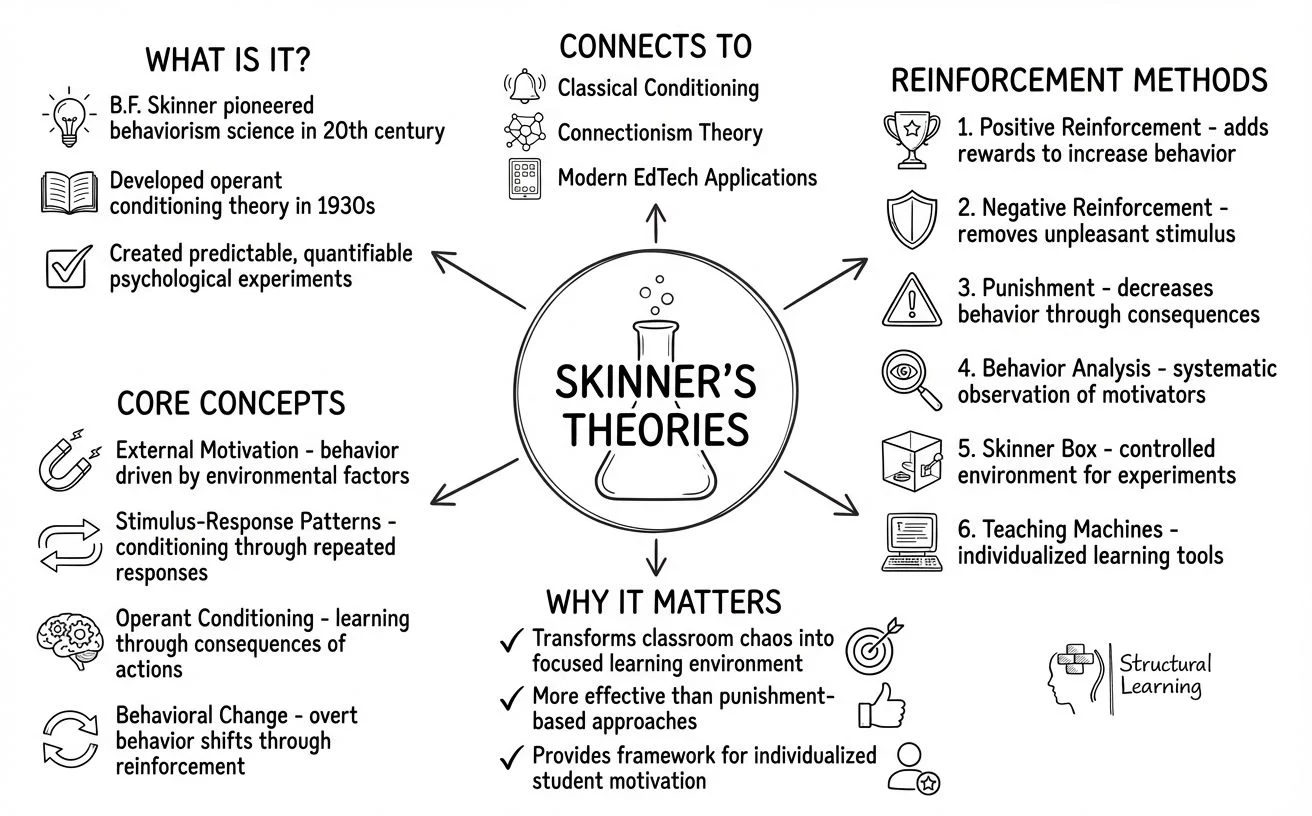

The American psychologist and social scientist B.F. Skinner was one the most influential psychologists of the 20th century. Skinner pioneered the science of behaviorism, discovered the power of positive reinforcement in education, invented the Skinner Box, as well as designed the foremost psychological experiments that gave predictable and quantitatively repeatable outcomes.

| Component/Concept | Type | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Reinforcement | Primary Reinforcer | Increases likelihood of desired behaviour through classroom rewards like praise, good grades, or sense of accomplishment | Use verbal praise, rewards, and recognition to encourage repetition of desired behaviours |

| Negative Reinforcement | Secondary Reinforcer | Increases behaviour by removing unpleasant stimulus (not punishment) | Remove obstacles or stressors when students demonstrate desired behaviours |

| Punishment | behaviour Reducer | Decreases likelihood of behaviour through negative consequences | Less effective than positive reinforcement; avoid overuse in classroom management |

| behaviour Analysis | Assessment Tool | Systematic observation and identification of reinforcers that influence specific behaviours | Observe students to identify what motivates them individually |

| External Motivation | behavioural Driver | behaviour change occurs through external stimuli and reinforcement, not internal factors | Focus on environmental factors and rewards rather than assuming internal student motivation |

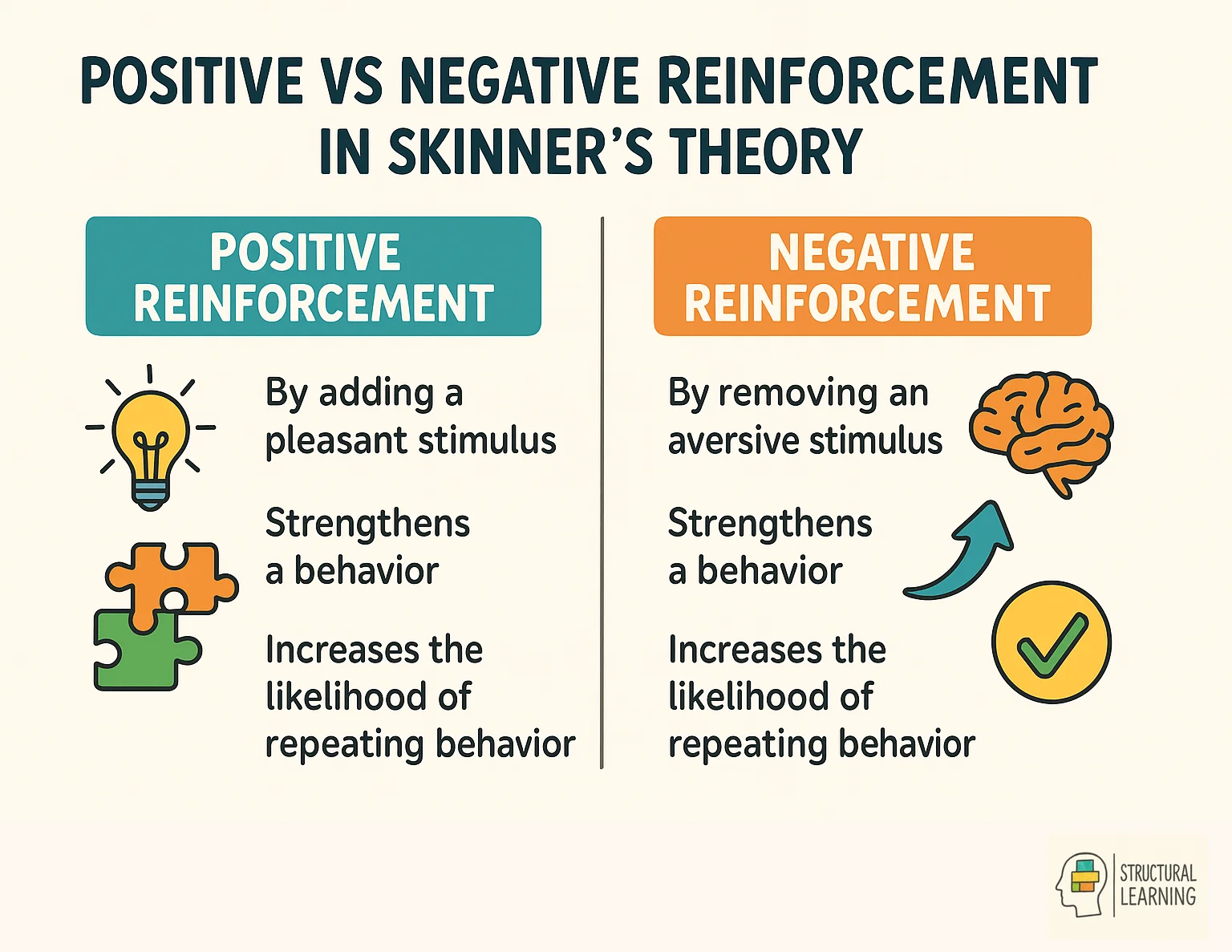

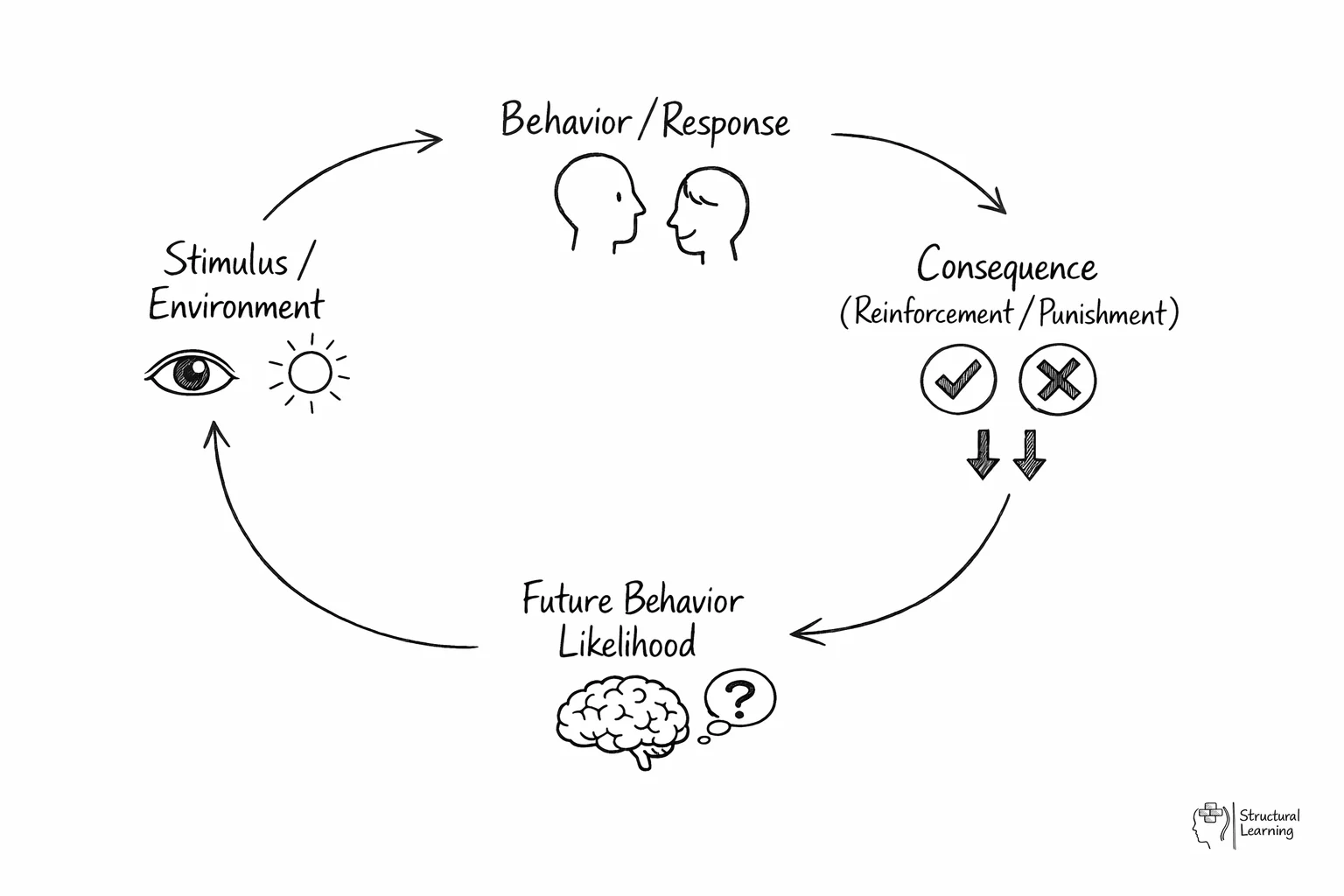

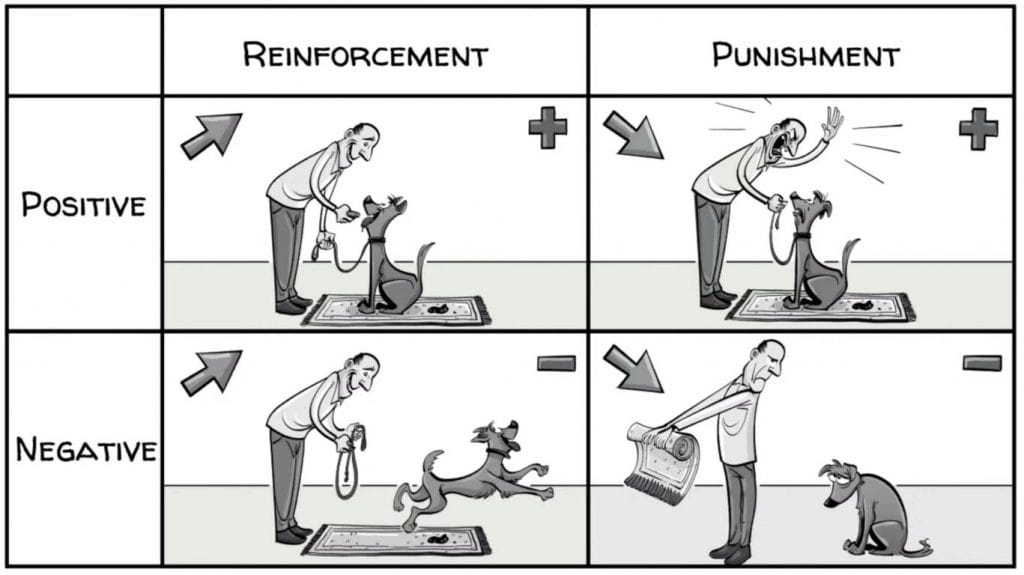

During the 1930s, B. F. Skinner proposed the theory of operant conditioning, which states that behaviour change and learning occur as the outcomes or effects of punishment and reinforcement. A response is strengthened by reinforcement, as it increases the likelihood that a desired behaviour will be repeated again in the future.

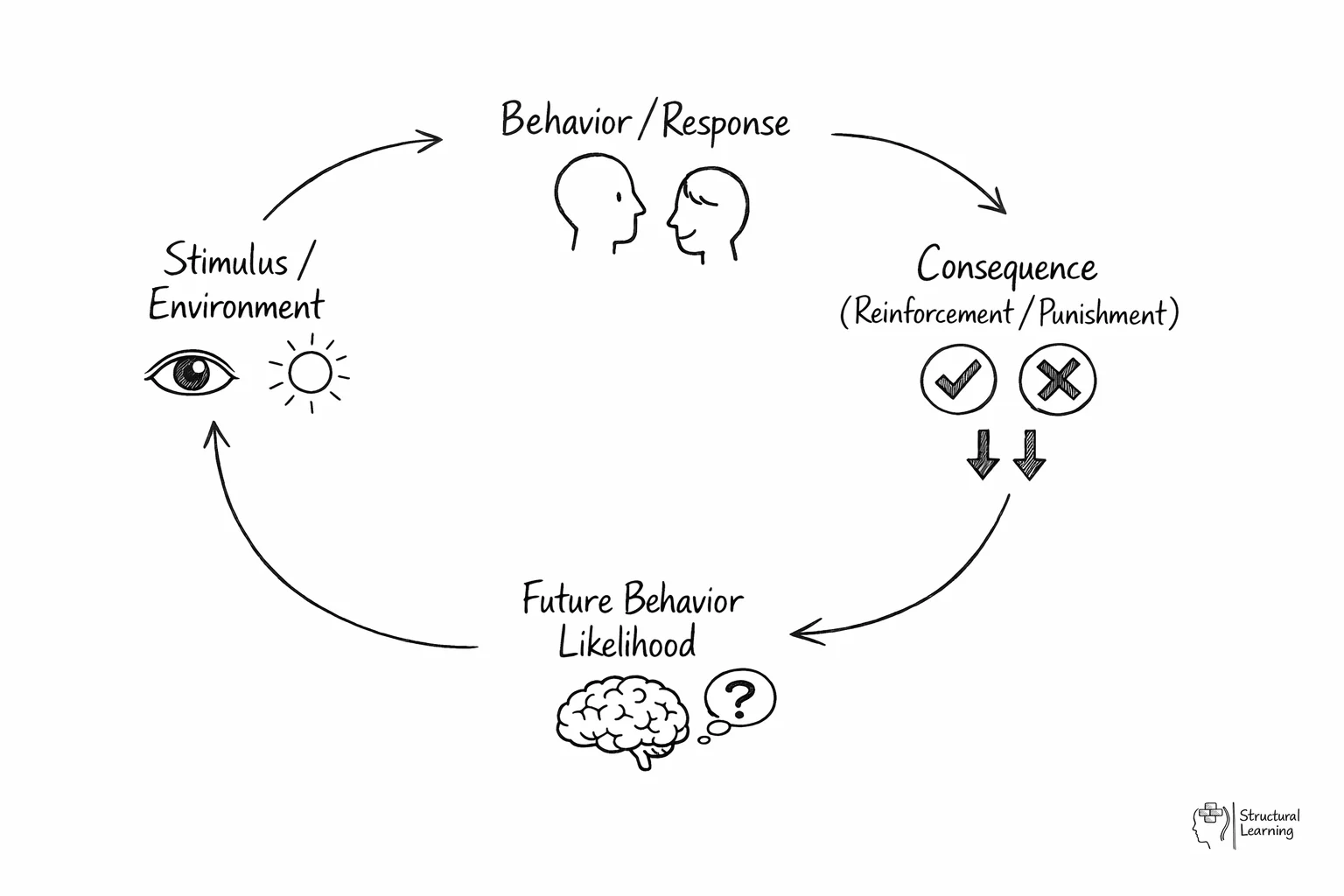

B. F. Skinner believes that learning involves shift in overt behaviour. A change in human behaviour occurs as the outcome of an person's response to stimuli (events) that take place in the surrounding. A response creates an outcome such as solving a mathematical problem, or explaining a word.

When an individual is rewarded for a specific Stimulus-Response pattern, he is conditioned to react. The unique aspect of operant conditioning by Frederic Skinner compared to previous types of behaviorism (for example: or connectionism) is that the individual may emit responses rather than only eliciting a reaction because of an external stimulus.

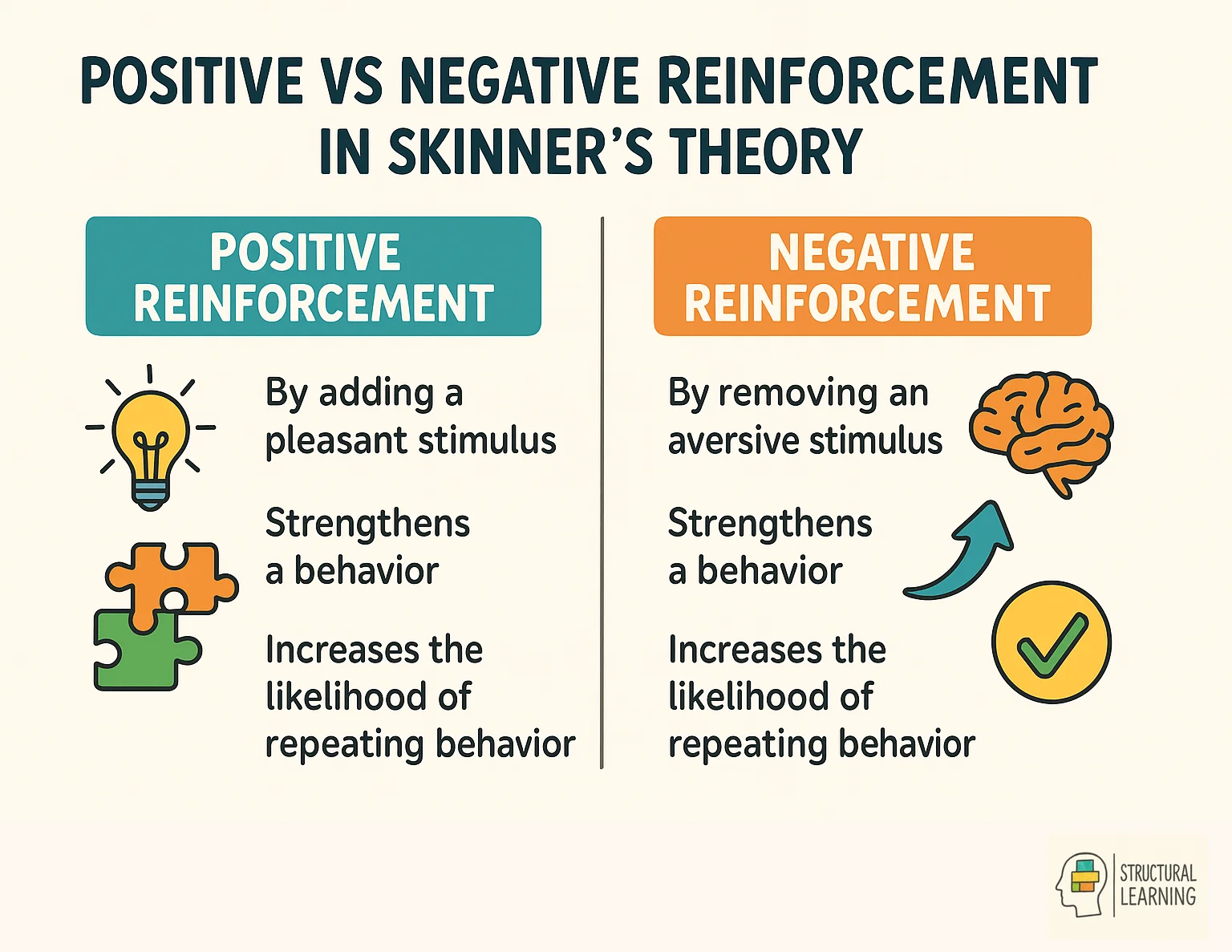

Skinner's positive reinforcement theory states that behaviours followed by pleasant consequences are more likely to be repeated (Fujii, 2024). This involves adding a desirable stimulus immediately after a behaviour occurs, such as giving praise, rewards, or privileges when students demonstrate desired behaviours. The key is that the reinforcement must be meaningful to the individual and delivered consistently to strengthen the behaviour.

Reinforcement is the main component of B. F. Skinner's Stimulus-Response theory. Anything that reinforces the a specific response is a reinforcer.

It might be in the form of a good percentage, verbal praise, or satisfaction or accomplishment. The operant conditioning theory by Frederic Skinner also includes negative reinforcers, any impulse that leads to the high occurrence of a reaction after its withdrawal (unlike negative stimulus, punishment, that leads to a decreased response).

behaviour analysis is a key component of Skinner's theory of positive reinforcement. By analysing the behaviour of individuals, Skinner believed that it was possible to identify the positive reinforcers that would lead to increased occurrence of that behaviour (Sivaraman et al., 2023).

This analysis can be used to develop effective strategies for shaping behaviour in individuals, as well as in groups and organisations (Asshdiqi, 2024). By focusing on positive reinforcement and identifying the behaviours that lead to success, Skinner's theory can be a powerful tool for creating positive change in a wide range of contexts.

One unique aspect of B.F. Skinner's theory is that it explains behavioural science and explanations for cognitive development and phenomena. For instance, Skinner described drive (motivation) with respect to reinforcement and deprivation schedules (Li et al., 2025).

Skinner (1957) explained language and verbal learning in terms of the operant conditioning approach, but his explanations were strongly criticised by psycholinguists and linguists. B. F. Skinner (1971) also explained the issues of social control and free will.

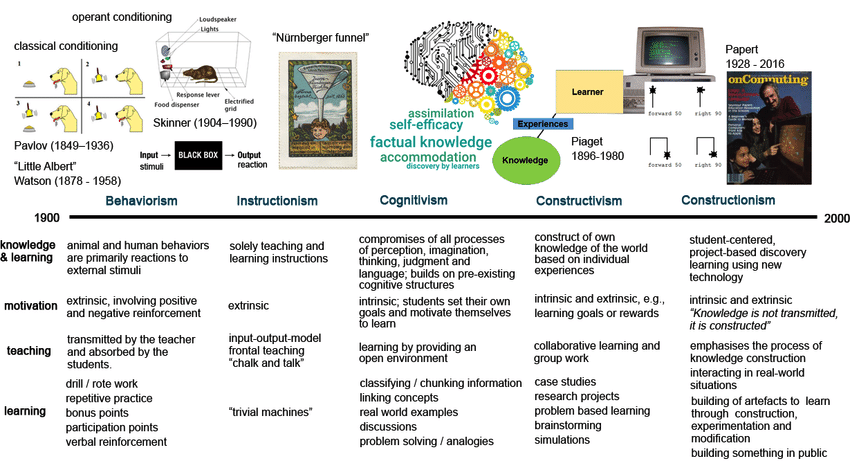

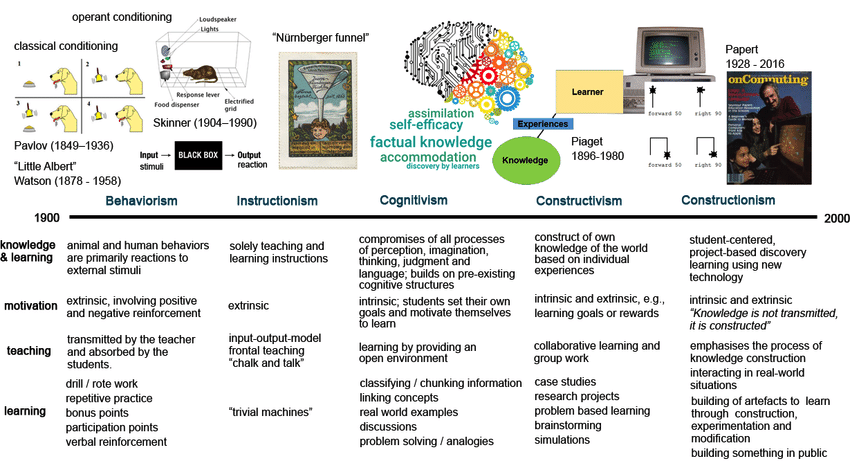

While Skinner built upon earlier behaviorist work, his approach differed significantly from predecessors like Pavlov and Watson.Understanding these distinctions helps teachers apply the most effective behaviour management strategies in modern classrooms.

| Psychologist | Theory Type | Key Focus | Learning Mechanism | Classroom Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B.F. Skinner | Operant Conditioning | Voluntary behaviour shaped by consequences | Reinforcement and punishment following active responses | Reward systems, behaviour charts, immediate feedback for student actions |

| Ivan Pavlov | Classical Conditioning | Involuntary responses to stimuli | Association between neutral and unconditioned stimuli | Creating positive classroom environment associations, routine-based learning |

| John B. Watson | Methodological Behaviorism | Observable behaviour only | Environmental conditioning, rejected internal states | Structured environments, consistent responses to behaviours |

| Edward Thorndike | Law of Effect | Satisfying vs. annoying outcomes | Trial and error learning with pleasurable consequences | Practise exercises with corrective feedback, formative assessment |

| Albert Bandura | Social Learning Theory | Observational learning and modelling | Learning through observation, imitation, and vicarious reinforcement | Teacher modelling, peer demonstrations, role-playing activities |

Teachers apply operant conditioning by immediately reinforcing desired behaviours with specific praise, points, or privileges while ignoring or redirecting unwanted behaviours (Presson et al., 2025). Create a clear behaviour management system where students understand exactly which actions lead to positive outcomes (Kibaya et al., 2025). Use variable ratio reinforcement schedules to maintain behaviours once established, rewarding students unpredictably to keep them engaged (Tariq & Habib, 2024).

B.F. Skinner suggested the following 5 steps to implement behaviour change:

It is necessary to first define the behaviour a teacher wants to see in students. For instance, a teacher's students may be perpetually rowdy at the start of class and the teacher wants students to get focused and settle down more quickly.

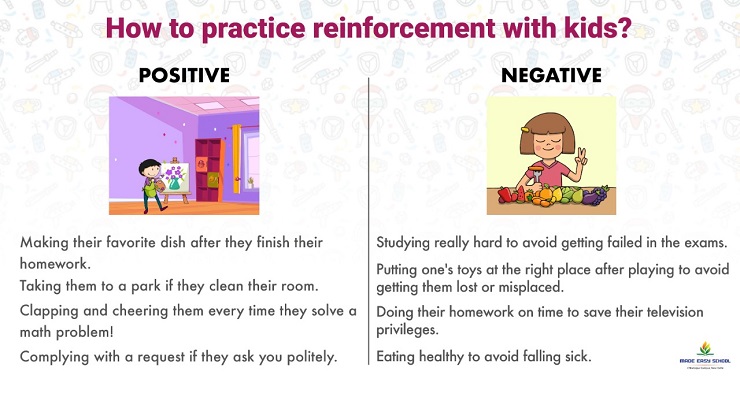

Of course, no teacher wants to give punishments or yell at the start of each class. Therefore, a teacher must think about how to give incentives or reward students for behaving appropriately (positive reinforcement ) or for refraining from negative behaviour (negative reinforcers).

After deciding which positive and negative reinforcers a teacher would apply, decide how to apply them. For instance, if a teacher wants to reward high-performing students with gold stars or points (positive reinforcement or strengthening of behaviour ), one must define what it means to be "a high-performer" and how students may demonstrate that behaviour to earn the reward. Or if the teacher wants to apply a negative reinforcer such as allowing high-performing students to skip a test in the next week, the teacher must find a way to keep record of how students performed each day of the current week.

Apply the selected techniques and record the results. According to behaviour Science experts, not every reinforcement brings results on each student. After introducing a different reinforcement technique, a teacher needs to assess how quickly the class improves performance and how many learners demonstrate the desired behaviour without additional reinforcements or reminders from the teacher.

If a reinforcement technique does not bring results, it is better to change it. A teacher may try something new the following week and repeat the technique until finding the most effective one that works for the type.

There is very little evidence to show the positive effects of punishment on individuals. Skinner B.F. Explained many negative effects of punishment in his operant conditioning theory. First of the many effects of punishment is, punishment mostly fails to create a permanent impact.

It may even increase the occurrence of the undesirable behaviour. The last of many effects of punishment is the attention gained by the offender, which may even serve as a reward for the offender more than the punishment.

Skinner believed that all human behaviour could be explained through environmental conditioning without considering internal mental states or consciousness. He argued that free will is an illusion and that all actions are determined by past reinforcements and punishments. His radical behaviorism focused exclusively on observable, measurable behaviours that could be scientifically studied and predicted.

According to behavioural Psychologist B. F. Skinner's theory, a learned response and its outcomes motivate human behaviour. This is called external motivation as it involves things outside one's personal thoughts and experiences reinforcing it. It is something one may observe.

Burrhus Frederic Skinner or B.F Skinner thought that human behaviour is determined by the environment. In B. F. Skinner's viewpoint, individuals have uniform behaviour patterns depending on their particular kind of Response Tendencies. Hence, individuals learn to behave in different ways with the passage of time. behaviour Science experts believe that behaviours with negative consequences are likely to decrease, whereas behaviours with positive outcomes tend to increase.

Skinner did not think that people's personalities are affected by their life or that childhood played an especially important role in shaping personality. Rather, he believed that personality of an individual continues to develop throughout life.

Skinner B.F. Has explained negative reinforcement to be interchangeable with an aversive stimulus as a negative reinforcement strengthens the behaviour by removing an aversive stimulus or through punishment.

Skinner's theories transformed psychology by establishing behaviorism as a dominant approach and introducing rigorous experimental methods for studying behaviour. His work led to practical applications in education, therapy, and behaviour modification programmes that are still used today. The emphasis on measurable outcomes and environmental factors shifted psychology towards more scientific, data-driven approaches.

B.F. Skinner's theory of operant conditioning has had a significant influence on understanding child development, particularly in how a child's behaviour can be shaped through reinforcement. According to Skinner, behaviour can be modified by the use of positive reinforcement, which involves strengthening a behaviour by providing a desirable outcome, or negative reinforcement, which strengthens behaviour by removing an unpleasant stimulus. Skinner's work contributed to the broader behavioural theory of personality, suggesting that individuals learn to respond in specific ways based on their history of interactions and learned experiences.

Like John B. Watson, Skinner was a committed behaviorist, focusing on how behaviour is shaped by its consequences. He developed what he termed "radical behaviorism," a perspective that seeks to explain behaviour as a product of the individual's history of reinforcement and environmental factors. Skinner's radical behaviorism holds that even private events, such as emotions, perceptions, and thoughts, which cannot be observed directly, are behaviours influenced by the environment, though they do not provide causal explanations for behaviour.

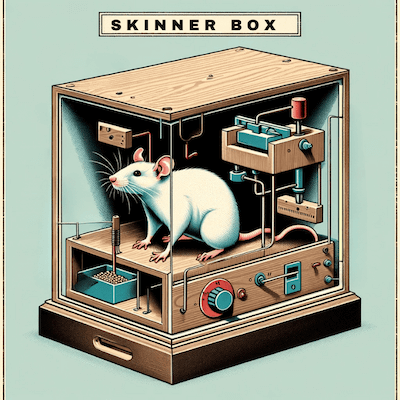

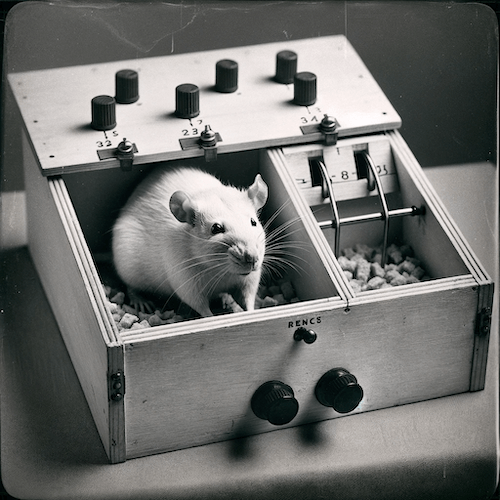

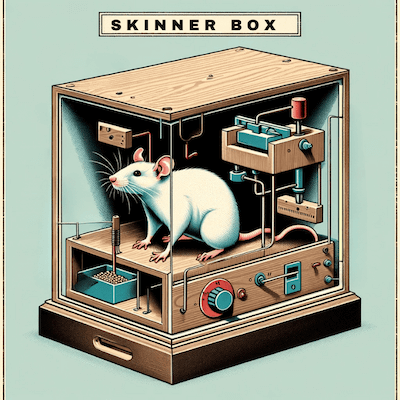

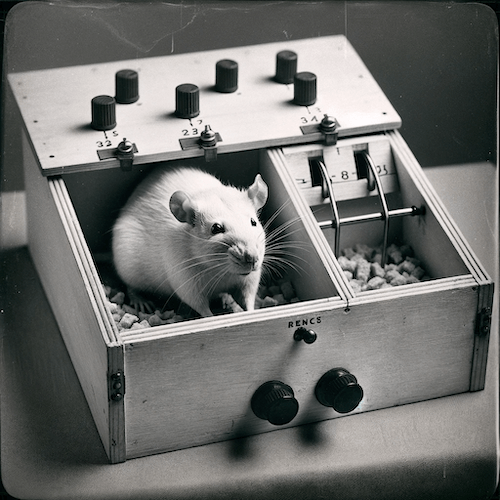

During his time at Harvard University, Skinner invented the operant conditioning chamber, more commonly known as the "Skinner Box." This apparatus allowed Skinner to study animal behaviour in a controlled environment. The Skinner Box typically contained a lever, a food tray, and a means to dispense food pellets. In one experiment, a rat was placed in the box, and, through exploration, it would eventually press the lever, leading to the delivery of a food pellet.

Initially, pressing the lever occurred by chance, but as the rat learned the association between pressing the lever and receiving food, the behaviour became more frequent. This process demonstrated operant conditioning, in which the rat's behaviour was shaped and reinforced by its consequences. The rat continued pressing the lever until it was satiated, illustrating how behaviour can be conditioned through reinforcement.

The Skinner Box and Skinner's research have been pivotal in shaping the field of psychology, particularly in understanding behaviour modification. The principle of reinforcement that emerged from this work states that the probability of a behaviour recurring depends on the consequences it produces. Reinforcement theory asserts that: (a) When a behaviour is followed by a rewarding stimulus, the likelihood of that behaviour increases.

(b) When individuals have the opportunity to avoid or escape an adverse situation, they are motivated to act accordingly. (c) If a behaviour is not reinforced, it is less likely to be repeated in the future.

Skinner's contributions emphasised both positive and negative reinforcement in shaping behaviour, and his work has influenced everything from education techniques to behaviour therapy, providing practical approaches to change and modify behaviour effectively.

Skinner's theories are applied through token economies, behaviour charts, and immediate feedback systems in modern classrooms. Teachers use programmed instruction and educational technology that breaks learning into small steps with immediate reinforcement for correct responses. Positive behaviour supp ort systems in schools directly stem from Skinner's principles of reinforcement rather than punishment.

Drawing from the principles of B.F. Skinner's theory, here are seven key applications that can be utilised in an educational setting:

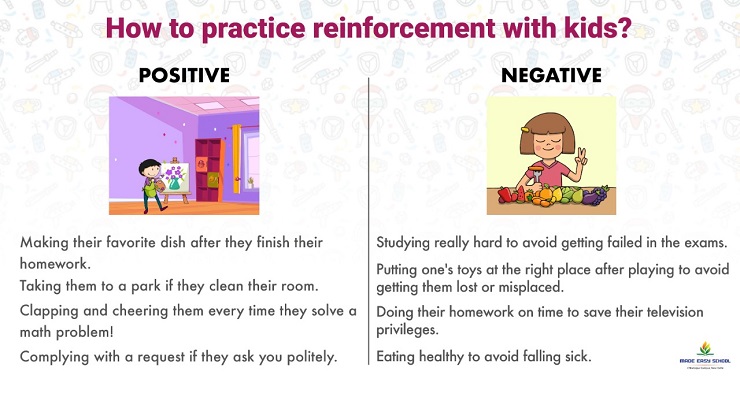

In the classroom, teachers can use positive reinforcement to increase the likelihood of desirable behaviours. For instance, praising a student for their active participation in class can encourage them to continue participating. This application is supported by the concept of 'Primary Reinforcer' in Skinner's theory, which refers to the use of naturally reinforcing stimuli, such as food or water. In the educational context, praise, recognition, or rewards can serve as primary reinforcers.

Negative reinforcement involves the removal of an unpleasant stimulus to increase a behaviour. For example, if students complete their homework on time, they might be exempt from a less desirable task. This strategy can motivate students to engage in positive behaviours to avoid negative outcomes.

Both positive and negative punishment can be used to decrease undesirable behaviours. Positive punishment involves adding an unpleasant consequence after a behaviour, while negative punishment involves taking away something desirable. For instance, a teacher might give extra homework (positive punishment) or take away free time (negative punishment) if a student misbehaves.

Skinner's theory suggests that complex behaviours can be learned through the process of shaping, which involves reinforcing successive approximations of the desired behaviour. For example, a teacher might first praise a student for simply raising their hand, then only reinforce when the student raises their hand and waits to be called on, and finally only reinforce when the student raises their hand, waits to be called on, and provides a correct answer.

Continuous reinforcement involves providing a reinforcement every time a specific behaviour occurs. This can be particularly effective in the initial stages of learning a new behaviour. For example, a teacher might provide praise every time a student uses a new vocabulary word correctly.

Once a behaviour has been established, intermittent reinforcement (reinforcing the behaviour only some of the time) can be used to maintain the behaviour over time. This can help to prevent 'satiation' to the reinforcer, making the behaviour more resistant to extinction.

Secondary reinforcers are stimuli that have become reinforcing through their association with primary reinforcers. In a classroom, grades, tokens, or points can serve as secondary reinforcers. For example, a teacher might use a token economy system, where students earn tokens for positive behaviours that they can later exchange for rewards.

As an example, a study conducted by Al-Rawi (2020) found that the use of social media applications (SMAs) in learning design in higher education may offer diverse educational advantages. The study found that the perceived ease of use (PEOU) and perceived usefulness (PU) of SMAs help learners to become more understanding, active, and engage with peers and lecturers.

As Skinner once said, "Education is what survives when what has been learned has been forgotten." This quote emphasises the lasting impact of education and using effective teaching strategies, such as those derived from Skinner's theory, to creates learning.

Skinner's most influential works include 'The behaviour of Organisms' (1938) which introduced operant conditioning, and 'Science and Human behaviour' (1953) which applied behavioural principles to human society. 'Verbal behaviour' (1957) explained language acquisition through reinforcement, while 'Beyond Freedom and Dignity' (1971) controversially argued against free will. His article 'The Science of Learning and the Art of Teaching' (1954) outlined programmed instruction principles.

These papers collectively provide a comprehensive overview of Skinner's contribution to education, exploring how his work on operant conditioning, schedules of reinforcement, and observable behaviour has shaped modern educational practices.

1) A Science for e-Learning: Understanding B.F. Skinner's Work in Today's Education" by J. Vargas (2010)

Summary: This paper highlights how B.F. Skinner's principles can enhance online teaching quality, incorporating his operant conditioning concepts into e-learning platforms.

2) The Contributions of B. F. Skinner's Work to my Life" by S. Axelrod (2004)

Summary: Axelrod reflects on how Skinner's work, particularly principles of operant conditioning, has shaped his academic career and effective child-rearing strategies.

3) B. F. Skinner: A Life" by J. H. Capshew, Daniel W. Bjork (1993)

Summary: This biography of B.F. Skinner explores how his work transformed education and child-rearing, emphasising his role as a key element in the development of observable behaviour analysis.

4) B. F. Skinner: Myth and Misperception" by C. Debell, Debra K. Harless (1992)

Summary: The paper addresses common myths about Skinner's work, especially in the context of classical conditioning and its application in education.

5) The impact of B. F. Skinner's science of operant learning on early childhood research, theory, treatment, and care" by H. Schlinger (2021)

Summary: Schlinger discusses Skinner's significant influence on early childhood education, highlighting operant learning as a fundamental aspect of desirable stimulus and reinforcement schedules.

6) ANÁLISE DE UMA POLÍTICA NACIONAL DE EDUCAÇÃO SEGUNDO SKINNER" by N. Matheus, Maria Eliza Mazzilli Pereira (2019)

Summary: This study evaluates how a Brazilian education decree, inspired by Skinner's propositions, may contribute to behaviour analysis in public policy, emphasising schedules of reinforcement and discriminative stimuli.

7) SKINNER'S PROGRAMMED LEARNING VERSUS CONVENTIONAL TEACHING METHOD IN MEDICAL EDUCATION: A COMPARATIVE STUDY" by P. Mukadam, S. Vyas, H. Nayak (2014)

Summary: This research compares Skinner's programmed learning method to conventional teaching in medical education, highlighting the effectiveness of operant conditioning principles and the role of aversive and unconditioned stimuli.

These papers collectively provide a comprehensive overview of Skinner's contribution to education, exploring how his work on operant conditioning, schedules of reinforcement, and observable behaviour has shaped modern educational practices.

The B.F. Skinner Foundation is a nonprofit organisation dedicated to promoting the ideas and work of B.F. Skinner, a renowned psychologist and behaviorist who developed the reinforcement theory mentioned in the previous paragraph. The foundation was established in 1987, and its mission is to advance the science of behaviour and to promote the principles of behaviorism.

The foundation offers a variety of resources, including books, articles, and videos, to help individuals better understand Skinner's theories and how they can be applied in various settings. Additionally, the foundation provides funding for research and education related to behaviorism and Skinner's work.

behaviour therapists are among the professionals who can benefit from the resources and funding provided by the B.F. Skinner Foundation. Skinner's theories and principles have been widely applied in the field of psychology, particularly in the treatment of various behavioural disorders.

By utilising the foundation's resources, behaviour therapists can gain a deeper understanding of Skinner's work and how it can be applied in their practise. The foundation also offers grants and scholarships to support research and education in behaviorism, which can further advance the field of behavioural therapy.

Positive reinforcement increases desired behaviour by adding pleasant consequences like praise or rewards immediately after the behaviour occurs. Negative reinforcement strengthens behaviour by removing unpleasant stimuli, such as allowing high-performing students to skip a test or removing classroom stressors when students demonstrate desired behaviours.

Teachers should first define specific behavioural goals, then determine appropriate reinforcement methods and select techniques to implement them systematically. The process involves applying these techniques whilst recording results, then evaluating effectiveness and adjusting the approach based on how students respond to the reinforcement strategies.

Skinner's research demonstrates that positive reinforcement creates lasting behaviour change by encouraging repetition of desired actions, whilst punishment only temporarily suppresses unwanted behaviour without teaching alternatives. Positive reinforcement builds intrinsic motivation and creates a more supportive learning environment that focuses on success rather than failure.

Skinner believed that behaviour change occurs through external stimuli and environmental factors rather than internal motivation or willpower. Teachers should focus on creating the right environmental conditions, rewards, and reinforcement schedules rather than assuming students are internally motivated to learn or behave appropriately.

Teachers should systematically observe students to identify what specifically motivates each individual, as reinforcers vary from person to person. This involves noting which rewards, privileges, or types of recognition actually increase desired behaviours for specific students, then tailoring reinforcement strategies accordingly.

Teachers can use specific verbal praise, point systems, or privileges immediately following desired behaviours, whilst implementing variable ratio reinforcement schedules to maintain engagement. Examples include giving gold stars for completed work, allowing students to skip certain tasks when they demonstrate consistent good behaviour, or providing recognition for students who settle down quickly at the start of class.

Skinner transformed psychological research by developing rigorous experimental methods that produced measurable, repeatable results, setting him apart from the introspective approaches dominating psychology at the time. His most famous innovation, the operant conditioning chamber (commonly called the Skinner Box), allowed precise control over environmental variables whilst automatically recording subject responses. This apparatus typically featured a lever or button that animals could press to receive food pellets, water, or other reinforcers, with every response meticulously tracked through cumulative recording devices. Morris and Smith (2004) highlight how Skinner's cumulative record methodology became fundamental to behavioural analysis, providing visual representations of response rates that revealed patterns invisible through traditional observation methods.

His landmark experiments with pigeons and rats demonstrated principles that transformed educational practise. In his pigeon studies, Skinner trained birds to discriminate between different shapes, colours, and even artistic styles by reinforcing correct pecking responses. More remarkably, he taught pigeons to play table tennis and guide missiles during World War II, though the latter project never saw military deployment.

His rat experiments established foundational schedules of reinforcement: continuous (reinforcing every correct response), fixed-ratio (reinforcing after a set number of responses), variable-ratio (reinforcing after an unpredictable number of responses), and interval schedules. Variable-ratio schedules proved most resistant to extinction, explaining why gambling and social learning notifications remain so compelling.

These experimental findings translate directly into classroom practise. Teachers can implement variable-ratio reinforcement by randomly checking homework assignments rather than collecting every piece, maintaining high completion rates whilst reducing marking load. Similarly, Skinner's discovery that immediate reinforcement proves more effective than delayed rewards suggests teachers should provide instant feedback through digital tools or peer assessment rather than waiting days to return marked work.

Recent research by Chakawodza et al. (2024) demonstrates how technology-mediated approaches, such as flipped classroom pedagogy, align with Skinnerian principles by providing immediate feedback loops and individualised pacing, significantly improving engagement in complex subjects like organic chemistry.

Skinner's experimental rigour extended to educational technology through his teaching machines, mechanical devices that presented material in small steps and required correct responses before advancing. Unlike modern multiple-choice formats, these machines demanded constructed responses, preventing guessing and ensuring genuine understanding. Watson et al.

(2023) argue that nursing and midwifery education particularly benefits from adopting Skinner's experimental approach, using controlled trials to evaluate teaching methods rather than relying on tradition or intuition. For today's educators, this means systematically testing interventions: measuring baseline behaviour, implementing changes, and tracking outcomes through data collection tools like behaviour tracking apps or simple tally charts. This scientific approach transforms teaching from guesswork into evidence-based practise, ensuring strategies that genuinely work for specific pupil populations.

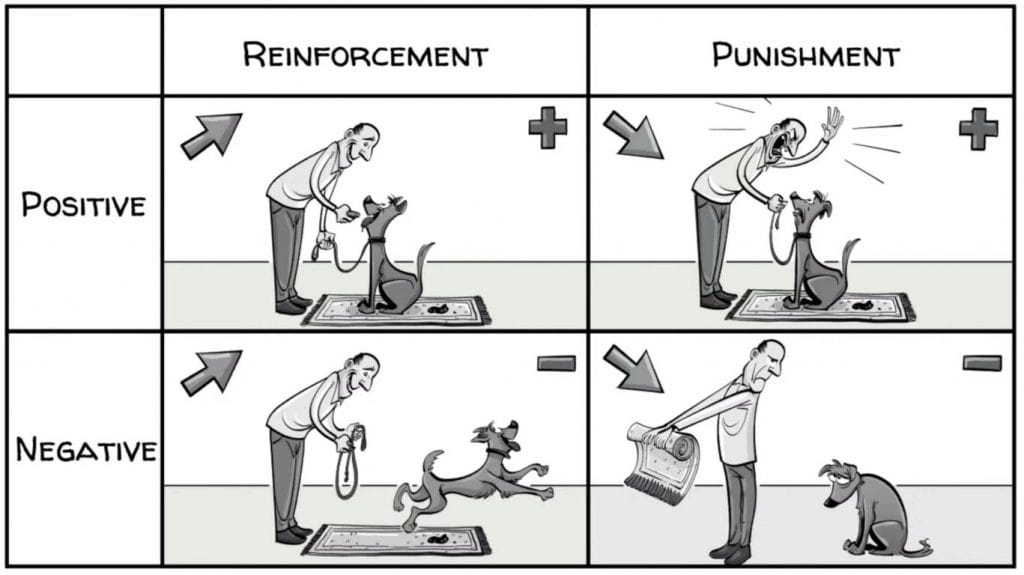

Understanding Skinner's four types of consequences helps teachers shape pupil behaviour more effectively. Each type serves a distinct purpose in classroom management, though their effectiveness varies considerably.

Positive reinforcement adds something pleasant to increase behaviour. When Year 3 pupils receive house points for completing homework, they're more likely to submit work consistently. Similarly, displaying exceptional work on the classroom wall motivates pupils to produce quality assignments. Research consistently shows this approach yields the strongest, most lasting behavioural changes.

Negative reinforcement removes something unpleasant to increase behaviour. Despite common misconceptions, this isn't punishment. For instance, allowing pupils who finish their maths problems correctly to skip the final question removes an unwanted task, encouraging accuracy and speed. Another example: permitting students who arrive punctually all week to leave five minutes early on Friday.

Positive punishment adds something unpleasant to decrease behaviour. This might include extra homework for talking during lessons or writing lines for repeated lateness. Whilst sometimes necessary, Skinner's research demonstrated that punishment often produces only temporary behavioural changes and can damage teacher-pupil relationships.

Negative punishment removes something pleasant to decrease behaviour. Examples include losing break time privileges or being excluded from a favourite classroom activity. Like positive punishment, this approach shows limited long-term effectiveness.

Skinner's experiments revealed that reinforcement schedules matter as much as reinforcement types. Variable ratio schedules, where rewards come after unpredictable numbers of correct responses, create the most persistent behaviours. Teachers can apply this by randomly checking homework or unexpectedly praising good behaviour, keeping pupils consistently engaged without creating dependency on constant rewards.

At the heart of Skinner's revolutionary work lies operant conditioning, a process where behaviours are shaped through consequences. Unlike classical conditioning, which deals with automatic responses, operant conditioning focuses on voluntary behaviours that 'operate' on the environment. When a pupil raises their hand and receives praise, they're more likely to repeat this behaviour; conversely, when talking out of turn leads to lost break time, this behaviour typically decreases.

Skinner identified three core components that drive behavioural change: the antecedent (what happens before), the behaviour itself, and the consequence (what follows). This ABC model provides teachers with a practical framework for understanding classroom dynamics. For instance, when the lunch bell rings (antecedent), pupils pack away materials quickly (behaviour), and those who finish first get to line up first (consequence). This simple sequence demonstrates how environmental cues and outcomes shape student actions.

The timing of consequences proves crucial for effective learning. Skinner's research showed that immediate reinforcement produces stronger behavioural changes than delayed responses. In practise, this means praising a struggling reader immediately after they sound out a difficult word, rather than waiting until the end of the lesson. Similarly, using a token system where pupils earn points instantly for positive behaviours creates clearer connections between actions and outcomes.

Teachers can harness operant conditioning through systematic observation and adjustment. Start by identifying specific behaviours you want to increase or decrease, then experiment with different consequences. A Year 3 teacher might notice that pupils complete maths problems more accurately when allowed to use coloured pens (positive reinforcement) or when freed from copying corrections (negative reinforcement). The key lies in discovering what genuinely motivates each individual pupil, as Skinner emphasised that reinforcers vary significantly between learners.

Understanding the distinction between positive and negative reinforcement remains one of Skinner's most misunderstood contributions to education. Positive reinforcement involves adding something pleasant after a desired behaviour, whilst negative reinforcement involves removing something unpleasant. Both types increase the likelihood of behaviour repetition, which sets them apart from punishment entirely.

In classroom practise, positive reinforcement might include awarding house points when pupils complete homework on time, displaying excellent work on a 'star board', or allowing extra computer time for meeting reading targets. These tangible rewards create clear connections between effort and outcome. Research by Cameron and Pierce (1994) demonstrated that such external rewards, when used appropriately, actually enhance intrinsic motivation rather than diminish it.

Negative reinforcement operates differently but proves equally valuable. Consider allowing pupils who finish their work accurately to skip a review exercise, or permitting those who arrive punctually all week to leave class two minutes early on Friday. You're removing something pupils find tedious or restrictive, thereby reinforcing the positive behaviour. This approach particularly benefits pupils who struggle with traditional reward systems.

Skinner's framework emphasises timing and consistency above all else. Reinforcement must occur immediately after the desired behaviour, and teachers must apply it consistently across similar situations. A Year 3 teacher might use a marble jar system where positive behaviours earn marbles immediately, with a class reward when the jar fills. Meanwhile, negative reinforcement could involve removing assigned seats once pupils demonstrate they can choose appropriate working partners independently.

Skinner's research revealed that when we reinforce behaviour matters just as much as how we reinforce it. His experiments with pigeons and rats demonstrated that different reinforcement schedules produce dramatically different learning outcomes. For teachers, understanding these schedules transforms how we plan rewards, feedback, and recognition in our classrooms.

The most straightforward approach is continuous reinforcement, where every correct response receives a reward. This works brilliantly when teaching new skills; for instance, praising every correct phonics sound a Reception pupil makes accelerates initial learning. However, continuous reinforcement can quickly become unsustainable and may lead to pupils becoming dependent on constant praise.

Skinner discovered that intermittent reinforcement schedules create more persistent behaviours. A fixed ratio schedule, such as rewarding every fifth completed maths problem, maintains motivation whilst reducing teacher workload. Variable ratio schedules prove even more powerful; randomly checking and praising homework completion keeps pupils consistently engaged, as they never know when recognition might come.

Fixed interval schedules, like weekly spelling tests, can produce uneven effort, with pupils cramming just before the test. Variable interval schedules work better for sustained engagement. Try conducting surprise checks of reading journals or randomly selecting days to award house points for good behaviour. This uncertainty keeps pupils consistently prepared.

Research shows that behaviours learned through intermittent reinforcement resist extinction far better than those learned through continuous reinforcement. Start new behaviours with frequent reinforcement, then gradually thin the schedule. For example, initially praise a disruptive pupil every time they raise their hand, then shift to praising every third or fourth time, maintaining the behaviour with less effort whilst building independence.

Operant conditioning forms the foundation of Skinner's behavioural psychology, explaining how consequences shape future behaviour. Unlike Pavlov's classical conditioning, which deals with automatic responses, operant conditioning focuses on voluntary actions that pupils choose to repeat or avoid based on their outcomes. This principle revolutionised classroom management by showing teachers how to influence student behaviour through systematic reinforcement.

The theory operates on a simple premise: behaviours followed by pleasant consequences increase in frequency, whilst those followed by unpleasant consequences decrease. Skinner identified four key consequences: positive reinforcement (adding something pleasant), negative reinforcement (removing something unpleasant), positive punishment (adding something unpleasant), and negative punishment (removing something pleasant). Research consistently shows that the two reinforcement strategies prove far more effective than punishment in educational settings.

In practise, operant conditioning appears constantly in classrooms, often without teachers realising it. When a teacher displays excellent student work on the wall, they're using positive reinforcement to encourage similar effort from others. Similarly, allowing pupils who complete their work early to choose a free-reading book demonstrates negative reinforcement; the reward is removing the constraint of assigned tasks.

Understanding these principles helps teachers design more effective behaviour management systems. For instance, rather than giving detention for late homework (positive punishment), teachers might require students to complete assignments during break time until they establish better habits, then gradually return break privileges as homework improves (negative reinforcement). This approach builds positive associations with completing work on time, creating lasting behavioural change that punishment alone rarely achieves.

The Skinner Box, formally known as the operant conditioning chamber, transformed how we understand learning through its elegant simplicity. This controlled environment allowed Skinner to observe how animals, typically rats or pigeons, modified their behaviour based on consequences. The apparatus contained a lever or button that, when pressed, delivered food pellets or other rewards, demonstrating how behaviour could be shaped through systematic reinforcement.

What made Skinner's experimental design revolutionary was its ability to produce measurable, repeatable results. Animals quickly learned to press the lever more frequently when rewarded, providing concrete evidence that behaviour could be modified through environmental factors rather than internal drives. The box also revealed how different reinforcement schedules affected learning rates; continuous reinforcement led to rapid learning but quick extinction, whilst variable schedules created more persistent behaviours.

For teachers, the Skinner Box principles translate directly into classroom practise. Consider creating a 'behaviour tracking chart' where pupils earn stamps for completing homework promptly. Start with consistent rewards (continuous reinforcement) then gradually shift to unpredictable rewards (variable reinforcement) to maintain the behaviour long-term. Similarly, design classroom activities with clear cause-and-effect relationships: when pupils demonstrate good listening during story time, they earn extra choice time afterwards.

The experimental findings also explain why some classroom reward systems fail. Just as Skinner's animals stopped pressing levers when rewards ceased, pupils may abandon positive behaviours if reinforcement disappears too quickly. Instead, teachers should gradually reduce rewards whilst the behaviour becomes habitual, a process Skinner termed 'fading'. This scientific approach to behaviour modification remains one of education's most practical psychological tools.

Pupils' Perceptions on Token Economy in ESL Classroom View study ↗

(2021)

This case study examines how English language students in Malaysia responded to a token economy system, where students earn tokens or points for positive behaviours and academic achievements. The research focuses specifically on improving student participation in speaking activities, one of the most challenging aspects of language learning. Teachers working with reluctant speakers or seeking to increase classroom participation will find practical insights into how students actually experience these reward systems.

Enhancing Discipline Through Operant Conditioning in Islamic Education at Elementary School Purnama 1 View study ↗

Agus Sulthoni Imami et al. (2025)

This study demonstrates how elementary teachers successfully used Skinner's reinforcement techniques to improve student discipline while integrating Islamic educational values. The research shows how operant conditioning can be adapted to different cultural and religious contexts without losing its effectiveness. Educators in diverse school settings will appreciate seeing how behavioural management techniques can respect and incorporate students' cultural backgrounds while still achieving discipline goals.

Bridging Theory and Classroom Practise: Examining the Influence of Behaviorist Learning Theory on Student Conduct and Teaching Strategy View study ↗

Ulin Nuha & Nur Nafisatul Fithriyah (2025)

This research examines how behaviorist principles translate into real classroom situations, focusing on measurable improvements in student behaviour and learning outcomes. The study bridges the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application, showing teachers exactly how to implement Skinner's ideas in their daily instruction. Classroom teachers will find this particularly valuable for understanding how to move from reading about behaviorism to actually using these strategies effectively with their students.

THE ROLE OF TEACHER PRAISE AND POSITIVE REINFORCEMENT IN IMPROVING STUDENT MOTIVATION IN MIDDLE SCHOOL View study ↗

1 citations

Xiao Yuhe & A. Bhaumik (2025)

This study reveals how different types of teacher praise and rewards specifically impact middle school students' motivation during the challenging adolescent years. The research distinguishes between verbal praise, recognition, and tangible rewards, showing which approaches work best for maintaining student engagement when traditional motivators often fail. Middle school teachers will gain practical understanding of how to adjust their reinforcement strategies for this unique age group, where peer influence and developing independence make motivation particularly complex.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the evidence base for the strategies discussed above.

The Influence of School’s Reward Systems on Students’ Development View study ↗

18 citations

Chen (2023)

This research examines how school reward systems affect student development across different age groups, drawing on Skinner's operant conditioning principles. Teachers can use these findings to design more effective reward strategies that consider students' developmental stages and understand the psychological mechanisms behind behavioural reinforcement.

Introducing project-based learning steps to the preschool teachers in Bandung, Indonesia View study ↗

15 citations

Pratami et al. (2024)

This study introduces project-based learning methods to Indonesian preschool teachers as part of curriculum reform. Teachers can learn structured approaches to implementing project-based learning that aligns with modern educational standards whilst enhancing educational quality through hands-on, collaborative learning experiences.

Exploring autonomy support and learning preference in higher education: introducing a flexible and personalised learning environment with technology View study ↗

Fujii (2024)

This research explores how technology can support student autonomy and personalised learning in higher education settings. Teachers can apply these insights to create more flexible learning environments that accommodate individual student preferences whilst promoting self-directed learning and greater learner independence.

Verbal behaviour development theory and relational frame theory: Reflecting on similarities and differences. View study ↗

31 citations

Sivaraman et al. (2023)

This theoretical paper compares two behaviour-analytic approaches to understanding human language and cognition, both rooted in Skinner's verbal behaviour analysis. Teachers can gain deeper insights into how language develops and how different theoretical frameworks might inform their approaches to language instruction.

Adopting Theories Underlying Directed Technology Integration Strategies: Study Objectivist Learning Theories View study ↗

Asshdiqi (2024)

This study examines objectivist learning theories, including Skinner's behaviourism, in the context of technology integration strategies. Teachers can better understand how behavioural principles and information processing theories can guide effective use of educational technology in structured learning environments.

Pupils' Perceptions on Token Economy in ESL Classroom View study ↗

(2021)

Malaysian ESL students shared their experiences with token economy systems, where they earned points or rewards for participating in speaking activities based on Skinner's operant conditioning principles. The research reveals how students actually feel about these reward systems and whether they find them motivating or frustrating when learning to speak English. This student perspective research helps teachers understand if their token-based motivation strategies are truly effective from the learner's point of view.

Administration of behaviour modification as a psychological technique for effective classroom management in teaching and learning of chemistry among senior secondary school students in Zonal Education Quality Assurance, Kankia, Katsina State. View study ↗

Sa'adatu Atiku et al. (2022)

This Nigerian study tested whether systematic behaviour modification techniques could improve both classroom management and chemistry educational results among high school students. Researchers compared classes using structured reward and consequence systems against traditional teaching methods, measuring changes in student behaviour and academic performance. The findings provide concrete evidence for chemistry teachers about whether investing time in formal behaviour management systems actually pays off in terms of better learning and fewer classroom disruptions.

Enhancing Discipline Through Operant Conditioning in Islamic Education at Elementary School Purnama 1 View study ↗

Agus Sulthoni Imami et al. (2025)

Teachers at an Indonesian Islamic elementary school successfully used Skinner's operant conditioning principles to build student discipline while respecting religious and cultural values. The study shows how reward and consequence systems can be adapted to different cultural contexts without losing their effectiveness in shaping positive student behaviour. This research offers valuable insights for educators working in faith-based or culturally specific settings who want to apply behavioural psychology while honoring their community's values and traditions.

Bridging Theory and Classroom Practise: Examining the Influence of Behaviorist Learning Theory on Student Conduct and Teaching Strategy View study ↗

Ulin Nuha & Nur Nafisatul Fithriyah (2025)

This comprehensive study examines how behaviorist principles actually work when teachers apply them in real classroom situations, focusing on measurable changes in student behaviour and learning gains. The researchers found that while newer educational theories emphasise thinking processes, Skinner's approach remains highly effective for establishing clear expectations and consistent consequences. For practising teachers, this research validates the continued value of structured behavioural approaches, especially when dealing with classroom management challenges or when clear, observable learning goals are priorities.

The American psychologist and social scientist B.F. Skinner was one the most influential psychologists of the 20th century. Skinner pioneered the science of behaviorism, discovered the power of positive reinforcement in education, invented the Skinner Box, as well as designed the foremost psychological experiments that gave predictable and quantitatively repeatable outcomes.

| Component/Concept | Type | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Reinforcement | Primary Reinforcer | Increases likelihood of desired behaviour through classroom rewards like praise, good grades, or sense of accomplishment | Use verbal praise, rewards, and recognition to encourage repetition of desired behaviours |

| Negative Reinforcement | Secondary Reinforcer | Increases behaviour by removing unpleasant stimulus (not punishment) | Remove obstacles or stressors when students demonstrate desired behaviours |

| Punishment | behaviour Reducer | Decreases likelihood of behaviour through negative consequences | Less effective than positive reinforcement; avoid overuse in classroom management |

| behaviour Analysis | Assessment Tool | Systematic observation and identification of reinforcers that influence specific behaviours | Observe students to identify what motivates them individually |

| External Motivation | behavioural Driver | behaviour change occurs through external stimuli and reinforcement, not internal factors | Focus on environmental factors and rewards rather than assuming internal student motivation |

During the 1930s, B. F. Skinner proposed the theory of operant conditioning, which states that behaviour change and learning occur as the outcomes or effects of punishment and reinforcement. A response is strengthened by reinforcement, as it increases the likelihood that a desired behaviour will be repeated again in the future.

B. F. Skinner believes that learning involves shift in overt behaviour. A change in human behaviour occurs as the outcome of an person's response to stimuli (events) that take place in the surrounding. A response creates an outcome such as solving a mathematical problem, or explaining a word.

When an individual is rewarded for a specific Stimulus-Response pattern, he is conditioned to react. The unique aspect of operant conditioning by Frederic Skinner compared to previous types of behaviorism (for example: or connectionism) is that the individual may emit responses rather than only eliciting a reaction because of an external stimulus.

Skinner's positive reinforcement theory states that behaviours followed by pleasant consequences are more likely to be repeated (Fujii, 2024). This involves adding a desirable stimulus immediately after a behaviour occurs, such as giving praise, rewards, or privileges when students demonstrate desired behaviours. The key is that the reinforcement must be meaningful to the individual and delivered consistently to strengthen the behaviour.

Reinforcement is the main component of B. F. Skinner's Stimulus-Response theory. Anything that reinforces the a specific response is a reinforcer.

It might be in the form of a good percentage, verbal praise, or satisfaction or accomplishment. The operant conditioning theory by Frederic Skinner also includes negative reinforcers, any impulse that leads to the high occurrence of a reaction after its withdrawal (unlike negative stimulus, punishment, that leads to a decreased response).

behaviour analysis is a key component of Skinner's theory of positive reinforcement. By analysing the behaviour of individuals, Skinner believed that it was possible to identify the positive reinforcers that would lead to increased occurrence of that behaviour (Sivaraman et al., 2023).

This analysis can be used to develop effective strategies for shaping behaviour in individuals, as well as in groups and organisations (Asshdiqi, 2024). By focusing on positive reinforcement and identifying the behaviours that lead to success, Skinner's theory can be a powerful tool for creating positive change in a wide range of contexts.

One unique aspect of B.F. Skinner's theory is that it explains behavioural science and explanations for cognitive development and phenomena. For instance, Skinner described drive (motivation) with respect to reinforcement and deprivation schedules (Li et al., 2025).

Skinner (1957) explained language and verbal learning in terms of the operant conditioning approach, but his explanations were strongly criticised by psycholinguists and linguists. B. F. Skinner (1971) also explained the issues of social control and free will.

While Skinner built upon earlier behaviorist work, his approach differed significantly from predecessors like Pavlov and Watson.Understanding these distinctions helps teachers apply the most effective behaviour management strategies in modern classrooms.

| Psychologist | Theory Type | Key Focus | Learning Mechanism | Classroom Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B.F. Skinner | Operant Conditioning | Voluntary behaviour shaped by consequences | Reinforcement and punishment following active responses | Reward systems, behaviour charts, immediate feedback for student actions |

| Ivan Pavlov | Classical Conditioning | Involuntary responses to stimuli | Association between neutral and unconditioned stimuli | Creating positive classroom environment associations, routine-based learning |

| John B. Watson | Methodological Behaviorism | Observable behaviour only | Environmental conditioning, rejected internal states | Structured environments, consistent responses to behaviours |

| Edward Thorndike | Law of Effect | Satisfying vs. annoying outcomes | Trial and error learning with pleasurable consequences | Practise exercises with corrective feedback, formative assessment |

| Albert Bandura | Social Learning Theory | Observational learning and modelling | Learning through observation, imitation, and vicarious reinforcement | Teacher modelling, peer demonstrations, role-playing activities |

Teachers apply operant conditioning by immediately reinforcing desired behaviours with specific praise, points, or privileges while ignoring or redirecting unwanted behaviours (Presson et al., 2025). Create a clear behaviour management system where students understand exactly which actions lead to positive outcomes (Kibaya et al., 2025). Use variable ratio reinforcement schedules to maintain behaviours once established, rewarding students unpredictably to keep them engaged (Tariq & Habib, 2024).

B.F. Skinner suggested the following 5 steps to implement behaviour change:

It is necessary to first define the behaviour a teacher wants to see in students. For instance, a teacher's students may be perpetually rowdy at the start of class and the teacher wants students to get focused and settle down more quickly.

Of course, no teacher wants to give punishments or yell at the start of each class. Therefore, a teacher must think about how to give incentives or reward students for behaving appropriately (positive reinforcement ) or for refraining from negative behaviour (negative reinforcers).

After deciding which positive and negative reinforcers a teacher would apply, decide how to apply them. For instance, if a teacher wants to reward high-performing students with gold stars or points (positive reinforcement or strengthening of behaviour ), one must define what it means to be "a high-performer" and how students may demonstrate that behaviour to earn the reward. Or if the teacher wants to apply a negative reinforcer such as allowing high-performing students to skip a test in the next week, the teacher must find a way to keep record of how students performed each day of the current week.

Apply the selected techniques and record the results. According to behaviour Science experts, not every reinforcement brings results on each student. After introducing a different reinforcement technique, a teacher needs to assess how quickly the class improves performance and how many learners demonstrate the desired behaviour without additional reinforcements or reminders from the teacher.

If a reinforcement technique does not bring results, it is better to change it. A teacher may try something new the following week and repeat the technique until finding the most effective one that works for the type.

There is very little evidence to show the positive effects of punishment on individuals. Skinner B.F. Explained many negative effects of punishment in his operant conditioning theory. First of the many effects of punishment is, punishment mostly fails to create a permanent impact.

It may even increase the occurrence of the undesirable behaviour. The last of many effects of punishment is the attention gained by the offender, which may even serve as a reward for the offender more than the punishment.

Skinner believed that all human behaviour could be explained through environmental conditioning without considering internal mental states or consciousness. He argued that free will is an illusion and that all actions are determined by past reinforcements and punishments. His radical behaviorism focused exclusively on observable, measurable behaviours that could be scientifically studied and predicted.

According to behavioural Psychologist B. F. Skinner's theory, a learned response and its outcomes motivate human behaviour. This is called external motivation as it involves things outside one's personal thoughts and experiences reinforcing it. It is something one may observe.

Burrhus Frederic Skinner or B.F Skinner thought that human behaviour is determined by the environment. In B. F. Skinner's viewpoint, individuals have uniform behaviour patterns depending on their particular kind of Response Tendencies. Hence, individuals learn to behave in different ways with the passage of time. behaviour Science experts believe that behaviours with negative consequences are likely to decrease, whereas behaviours with positive outcomes tend to increase.

Skinner did not think that people's personalities are affected by their life or that childhood played an especially important role in shaping personality. Rather, he believed that personality of an individual continues to develop throughout life.

Skinner B.F. Has explained negative reinforcement to be interchangeable with an aversive stimulus as a negative reinforcement strengthens the behaviour by removing an aversive stimulus or through punishment.

Skinner's theories transformed psychology by establishing behaviorism as a dominant approach and introducing rigorous experimental methods for studying behaviour. His work led to practical applications in education, therapy, and behaviour modification programmes that are still used today. The emphasis on measurable outcomes and environmental factors shifted psychology towards more scientific, data-driven approaches.

B.F. Skinner's theory of operant conditioning has had a significant influence on understanding child development, particularly in how a child's behaviour can be shaped through reinforcement. According to Skinner, behaviour can be modified by the use of positive reinforcement, which involves strengthening a behaviour by providing a desirable outcome, or negative reinforcement, which strengthens behaviour by removing an unpleasant stimulus. Skinner's work contributed to the broader behavioural theory of personality, suggesting that individuals learn to respond in specific ways based on their history of interactions and learned experiences.

Like John B. Watson, Skinner was a committed behaviorist, focusing on how behaviour is shaped by its consequences. He developed what he termed "radical behaviorism," a perspective that seeks to explain behaviour as a product of the individual's history of reinforcement and environmental factors. Skinner's radical behaviorism holds that even private events, such as emotions, perceptions, and thoughts, which cannot be observed directly, are behaviours influenced by the environment, though they do not provide causal explanations for behaviour.

During his time at Harvard University, Skinner invented the operant conditioning chamber, more commonly known as the "Skinner Box." This apparatus allowed Skinner to study animal behaviour in a controlled environment. The Skinner Box typically contained a lever, a food tray, and a means to dispense food pellets. In one experiment, a rat was placed in the box, and, through exploration, it would eventually press the lever, leading to the delivery of a food pellet.

Initially, pressing the lever occurred by chance, but as the rat learned the association between pressing the lever and receiving food, the behaviour became more frequent. This process demonstrated operant conditioning, in which the rat's behaviour was shaped and reinforced by its consequences. The rat continued pressing the lever until it was satiated, illustrating how behaviour can be conditioned through reinforcement.

The Skinner Box and Skinner's research have been pivotal in shaping the field of psychology, particularly in understanding behaviour modification. The principle of reinforcement that emerged from this work states that the probability of a behaviour recurring depends on the consequences it produces. Reinforcement theory asserts that: (a) When a behaviour is followed by a rewarding stimulus, the likelihood of that behaviour increases.

(b) When individuals have the opportunity to avoid or escape an adverse situation, they are motivated to act accordingly. (c) If a behaviour is not reinforced, it is less likely to be repeated in the future.

Skinner's contributions emphasised both positive and negative reinforcement in shaping behaviour, and his work has influenced everything from education techniques to behaviour therapy, providing practical approaches to change and modify behaviour effectively.

Skinner's theories are applied through token economies, behaviour charts, and immediate feedback systems in modern classrooms. Teachers use programmed instruction and educational technology that breaks learning into small steps with immediate reinforcement for correct responses. Positive behaviour supp ort systems in schools directly stem from Skinner's principles of reinforcement rather than punishment.

Drawing from the principles of B.F. Skinner's theory, here are seven key applications that can be utilised in an educational setting:

In the classroom, teachers can use positive reinforcement to increase the likelihood of desirable behaviours. For instance, praising a student for their active participation in class can encourage them to continue participating. This application is supported by the concept of 'Primary Reinforcer' in Skinner's theory, which refers to the use of naturally reinforcing stimuli, such as food or water. In the educational context, praise, recognition, or rewards can serve as primary reinforcers.

Negative reinforcement involves the removal of an unpleasant stimulus to increase a behaviour. For example, if students complete their homework on time, they might be exempt from a less desirable task. This strategy can motivate students to engage in positive behaviours to avoid negative outcomes.

Both positive and negative punishment can be used to decrease undesirable behaviours. Positive punishment involves adding an unpleasant consequence after a behaviour, while negative punishment involves taking away something desirable. For instance, a teacher might give extra homework (positive punishment) or take away free time (negative punishment) if a student misbehaves.

Skinner's theory suggests that complex behaviours can be learned through the process of shaping, which involves reinforcing successive approximations of the desired behaviour. For example, a teacher might first praise a student for simply raising their hand, then only reinforce when the student raises their hand and waits to be called on, and finally only reinforce when the student raises their hand, waits to be called on, and provides a correct answer.

Continuous reinforcement involves providing a reinforcement every time a specific behaviour occurs. This can be particularly effective in the initial stages of learning a new behaviour. For example, a teacher might provide praise every time a student uses a new vocabulary word correctly.

Once a behaviour has been established, intermittent reinforcement (reinforcing the behaviour only some of the time) can be used to maintain the behaviour over time. This can help to prevent 'satiation' to the reinforcer, making the behaviour more resistant to extinction.

Secondary reinforcers are stimuli that have become reinforcing through their association with primary reinforcers. In a classroom, grades, tokens, or points can serve as secondary reinforcers. For example, a teacher might use a token economy system, where students earn tokens for positive behaviours that they can later exchange for rewards.

As an example, a study conducted by Al-Rawi (2020) found that the use of social media applications (SMAs) in learning design in higher education may offer diverse educational advantages. The study found that the perceived ease of use (PEOU) and perceived usefulness (PU) of SMAs help learners to become more understanding, active, and engage with peers and lecturers.

As Skinner once said, "Education is what survives when what has been learned has been forgotten." This quote emphasises the lasting impact of education and using effective teaching strategies, such as those derived from Skinner's theory, to creates learning.

Skinner's most influential works include 'The behaviour of Organisms' (1938) which introduced operant conditioning, and 'Science and Human behaviour' (1953) which applied behavioural principles to human society. 'Verbal behaviour' (1957) explained language acquisition through reinforcement, while 'Beyond Freedom and Dignity' (1971) controversially argued against free will. His article 'The Science of Learning and the Art of Teaching' (1954) outlined programmed instruction principles.

These papers collectively provide a comprehensive overview of Skinner's contribution to education, exploring how his work on operant conditioning, schedules of reinforcement, and observable behaviour has shaped modern educational practices.

1) A Science for e-Learning: Understanding B.F. Skinner's Work in Today's Education" by J. Vargas (2010)

Summary: This paper highlights how B.F. Skinner's principles can enhance online teaching quality, incorporating his operant conditioning concepts into e-learning platforms.

2) The Contributions of B. F. Skinner's Work to my Life" by S. Axelrod (2004)

Summary: Axelrod reflects on how Skinner's work, particularly principles of operant conditioning, has shaped his academic career and effective child-rearing strategies.

3) B. F. Skinner: A Life" by J. H. Capshew, Daniel W. Bjork (1993)

Summary: This biography of B.F. Skinner explores how his work transformed education and child-rearing, emphasising his role as a key element in the development of observable behaviour analysis.

4) B. F. Skinner: Myth and Misperception" by C. Debell, Debra K. Harless (1992)

Summary: The paper addresses common myths about Skinner's work, especially in the context of classical conditioning and its application in education.

5) The impact of B. F. Skinner's science of operant learning on early childhood research, theory, treatment, and care" by H. Schlinger (2021)

Summary: Schlinger discusses Skinner's significant influence on early childhood education, highlighting operant learning as a fundamental aspect of desirable stimulus and reinforcement schedules.

6) ANÁLISE DE UMA POLÍTICA NACIONAL DE EDUCAÇÃO SEGUNDO SKINNER" by N. Matheus, Maria Eliza Mazzilli Pereira (2019)

Summary: This study evaluates how a Brazilian education decree, inspired by Skinner's propositions, may contribute to behaviour analysis in public policy, emphasising schedules of reinforcement and discriminative stimuli.

7) SKINNER'S PROGRAMMED LEARNING VERSUS CONVENTIONAL TEACHING METHOD IN MEDICAL EDUCATION: A COMPARATIVE STUDY" by P. Mukadam, S. Vyas, H. Nayak (2014)

Summary: This research compares Skinner's programmed learning method to conventional teaching in medical education, highlighting the effectiveness of operant conditioning principles and the role of aversive and unconditioned stimuli.

These papers collectively provide a comprehensive overview of Skinner's contribution to education, exploring how his work on operant conditioning, schedules of reinforcement, and observable behaviour has shaped modern educational practices.

The B.F. Skinner Foundation is a nonprofit organisation dedicated to promoting the ideas and work of B.F. Skinner, a renowned psychologist and behaviorist who developed the reinforcement theory mentioned in the previous paragraph. The foundation was established in 1987, and its mission is to advance the science of behaviour and to promote the principles of behaviorism.

The foundation offers a variety of resources, including books, articles, and videos, to help individuals better understand Skinner's theories and how they can be applied in various settings. Additionally, the foundation provides funding for research and education related to behaviorism and Skinner's work.

behaviour therapists are among the professionals who can benefit from the resources and funding provided by the B.F. Skinner Foundation. Skinner's theories and principles have been widely applied in the field of psychology, particularly in the treatment of various behavioural disorders.

By utilising the foundation's resources, behaviour therapists can gain a deeper understanding of Skinner's work and how it can be applied in their practise. The foundation also offers grants and scholarships to support research and education in behaviorism, which can further advance the field of behavioural therapy.

Positive reinforcement increases desired behaviour by adding pleasant consequences like praise or rewards immediately after the behaviour occurs. Negative reinforcement strengthens behaviour by removing unpleasant stimuli, such as allowing high-performing students to skip a test or removing classroom stressors when students demonstrate desired behaviours.

Teachers should first define specific behavioural goals, then determine appropriate reinforcement methods and select techniques to implement them systematically. The process involves applying these techniques whilst recording results, then evaluating effectiveness and adjusting the approach based on how students respond to the reinforcement strategies.

Skinner's research demonstrates that positive reinforcement creates lasting behaviour change by encouraging repetition of desired actions, whilst punishment only temporarily suppresses unwanted behaviour without teaching alternatives. Positive reinforcement builds intrinsic motivation and creates a more supportive learning environment that focuses on success rather than failure.

Skinner believed that behaviour change occurs through external stimuli and environmental factors rather than internal motivation or willpower. Teachers should focus on creating the right environmental conditions, rewards, and reinforcement schedules rather than assuming students are internally motivated to learn or behave appropriately.

Teachers should systematically observe students to identify what specifically motivates each individual, as reinforcers vary from person to person. This involves noting which rewards, privileges, or types of recognition actually increase desired behaviours for specific students, then tailoring reinforcement strategies accordingly.

Teachers can use specific verbal praise, point systems, or privileges immediately following desired behaviours, whilst implementing variable ratio reinforcement schedules to maintain engagement. Examples include giving gold stars for completed work, allowing students to skip certain tasks when they demonstrate consistent good behaviour, or providing recognition for students who settle down quickly at the start of class.

Skinner transformed psychological research by developing rigorous experimental methods that produced measurable, repeatable results, setting him apart from the introspective approaches dominating psychology at the time. His most famous innovation, the operant conditioning chamber (commonly called the Skinner Box), allowed precise control over environmental variables whilst automatically recording subject responses. This apparatus typically featured a lever or button that animals could press to receive food pellets, water, or other reinforcers, with every response meticulously tracked through cumulative recording devices. Morris and Smith (2004) highlight how Skinner's cumulative record methodology became fundamental to behavioural analysis, providing visual representations of response rates that revealed patterns invisible through traditional observation methods.

His landmark experiments with pigeons and rats demonstrated principles that transformed educational practise. In his pigeon studies, Skinner trained birds to discriminate between different shapes, colours, and even artistic styles by reinforcing correct pecking responses. More remarkably, he taught pigeons to play table tennis and guide missiles during World War II, though the latter project never saw military deployment.

His rat experiments established foundational schedules of reinforcement: continuous (reinforcing every correct response), fixed-ratio (reinforcing after a set number of responses), variable-ratio (reinforcing after an unpredictable number of responses), and interval schedules. Variable-ratio schedules proved most resistant to extinction, explaining why gambling and social learning notifications remain so compelling.

These experimental findings translate directly into classroom practise. Teachers can implement variable-ratio reinforcement by randomly checking homework assignments rather than collecting every piece, maintaining high completion rates whilst reducing marking load. Similarly, Skinner's discovery that immediate reinforcement proves more effective than delayed rewards suggests teachers should provide instant feedback through digital tools or peer assessment rather than waiting days to return marked work.

Recent research by Chakawodza et al. (2024) demonstrates how technology-mediated approaches, such as flipped classroom pedagogy, align with Skinnerian principles by providing immediate feedback loops and individualised pacing, significantly improving engagement in complex subjects like organic chemistry.

Skinner's experimental rigour extended to educational technology through his teaching machines, mechanical devices that presented material in small steps and required correct responses before advancing. Unlike modern multiple-choice formats, these machines demanded constructed responses, preventing guessing and ensuring genuine understanding. Watson et al.

(2023) argue that nursing and midwifery education particularly benefits from adopting Skinner's experimental approach, using controlled trials to evaluate teaching methods rather than relying on tradition or intuition. For today's educators, this means systematically testing interventions: measuring baseline behaviour, implementing changes, and tracking outcomes through data collection tools like behaviour tracking apps or simple tally charts. This scientific approach transforms teaching from guesswork into evidence-based practise, ensuring strategies that genuinely work for specific pupil populations.

Understanding Skinner's four types of consequences helps teachers shape pupil behaviour more effectively. Each type serves a distinct purpose in classroom management, though their effectiveness varies considerably.

Positive reinforcement adds something pleasant to increase behaviour. When Year 3 pupils receive house points for completing homework, they're more likely to submit work consistently. Similarly, displaying exceptional work on the classroom wall motivates pupils to produce quality assignments. Research consistently shows this approach yields the strongest, most lasting behavioural changes.

Negative reinforcement removes something unpleasant to increase behaviour. Despite common misconceptions, this isn't punishment. For instance, allowing pupils who finish their maths problems correctly to skip the final question removes an unwanted task, encouraging accuracy and speed. Another example: permitting students who arrive punctually all week to leave five minutes early on Friday.

Positive punishment adds something unpleasant to decrease behaviour. This might include extra homework for talking during lessons or writing lines for repeated lateness. Whilst sometimes necessary, Skinner's research demonstrated that punishment often produces only temporary behavioural changes and can damage teacher-pupil relationships.

Negative punishment removes something pleasant to decrease behaviour. Examples include losing break time privileges or being excluded from a favourite classroom activity. Like positive punishment, this approach shows limited long-term effectiveness.

Skinner's experiments revealed that reinforcement schedules matter as much as reinforcement types. Variable ratio schedules, where rewards come after unpredictable numbers of correct responses, create the most persistent behaviours. Teachers can apply this by randomly checking homework or unexpectedly praising good behaviour, keeping pupils consistently engaged without creating dependency on constant rewards.

At the heart of Skinner's revolutionary work lies operant conditioning, a process where behaviours are shaped through consequences. Unlike classical conditioning, which deals with automatic responses, operant conditioning focuses on voluntary behaviours that 'operate' on the environment. When a pupil raises their hand and receives praise, they're more likely to repeat this behaviour; conversely, when talking out of turn leads to lost break time, this behaviour typically decreases.