Developing Behaviours for Learning

Master the Learning Behaviours Framework to transform your classroom culture, boost pupil engagement by 20%, and develop self-regulated learners who thrive.

Master the Learning Behaviours Framework to transform your classroom culture, boost pupil engagement by 20%, and develop self-regulated learners who thrive.

Every lesson is a tug-of-war between time and attention. When pupils arrive with the right habits, listening actively, tackling tasks with curiosity, reflecting on mistakes, the rope moves effortlessly in your favour. These habits are what we call Learning Behaviours: observable actions that help children take charge of their own progress and work productively with others.

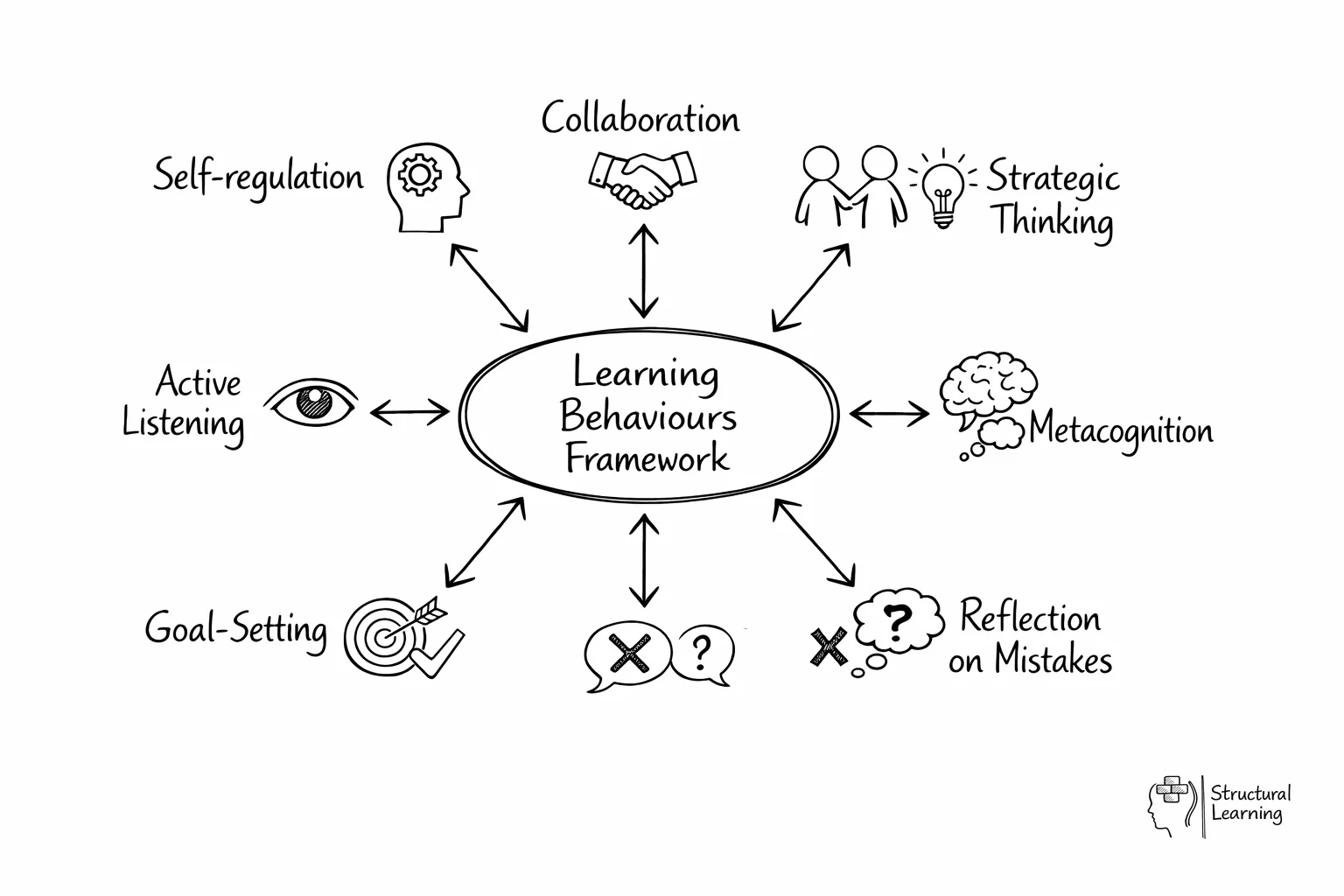

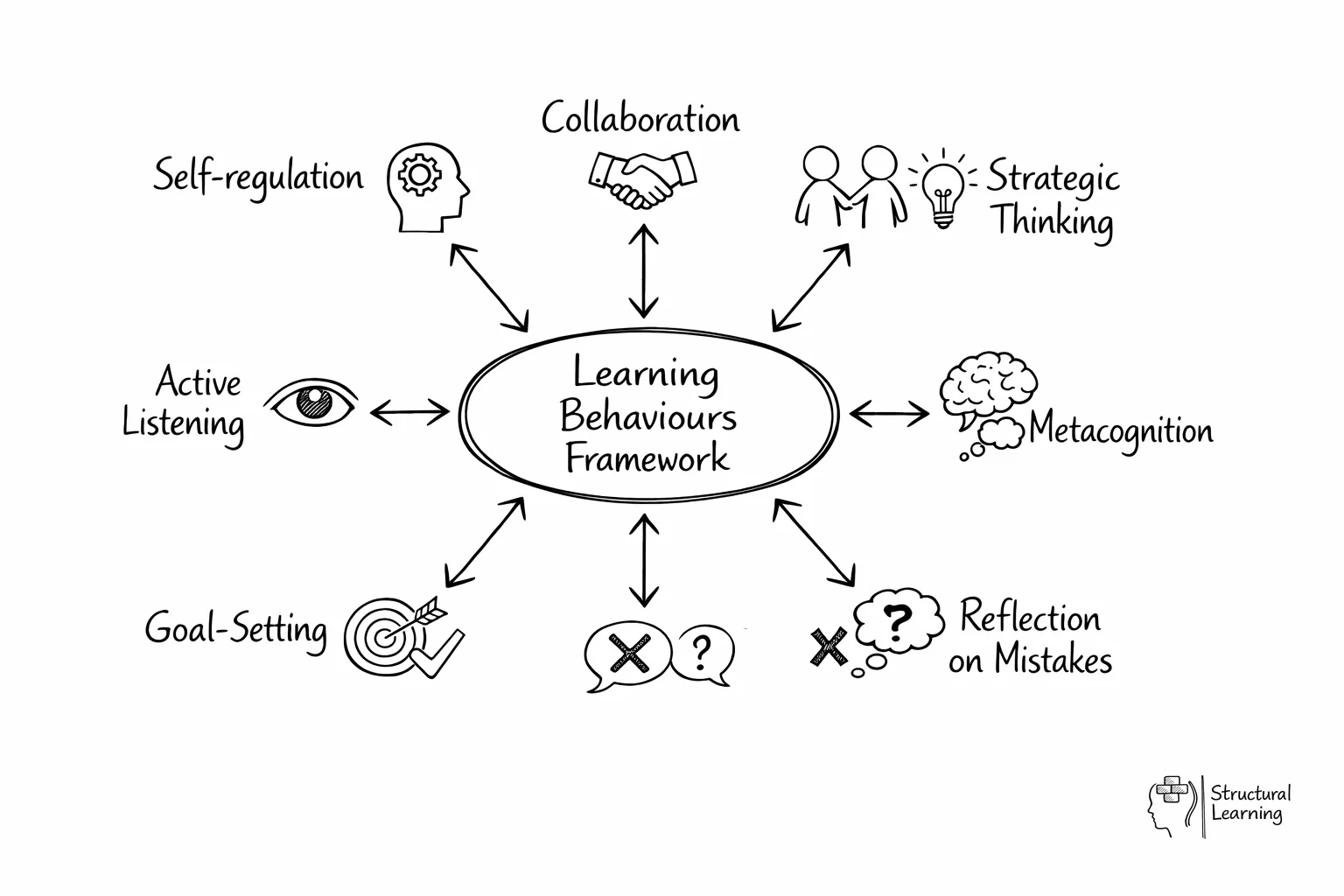

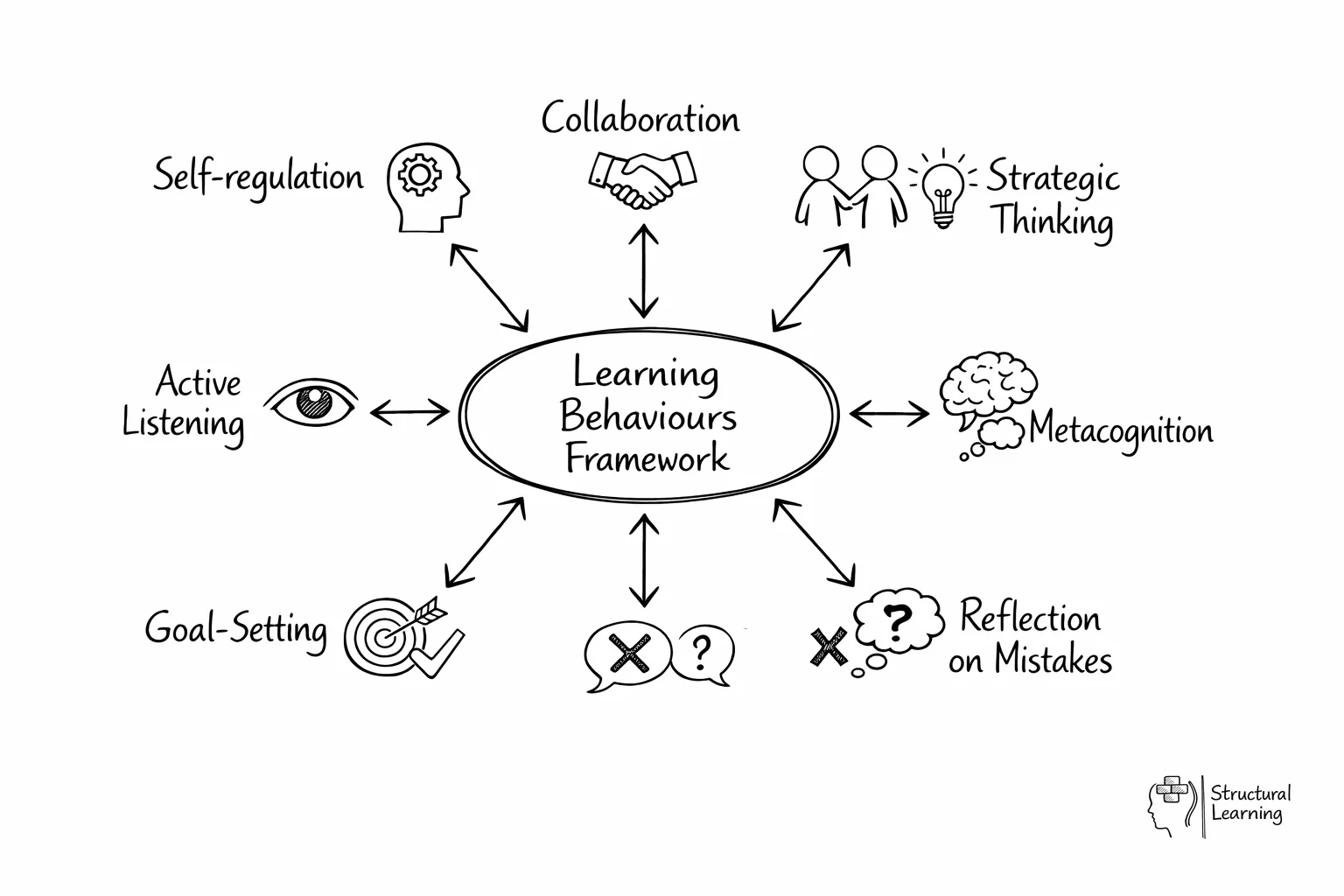

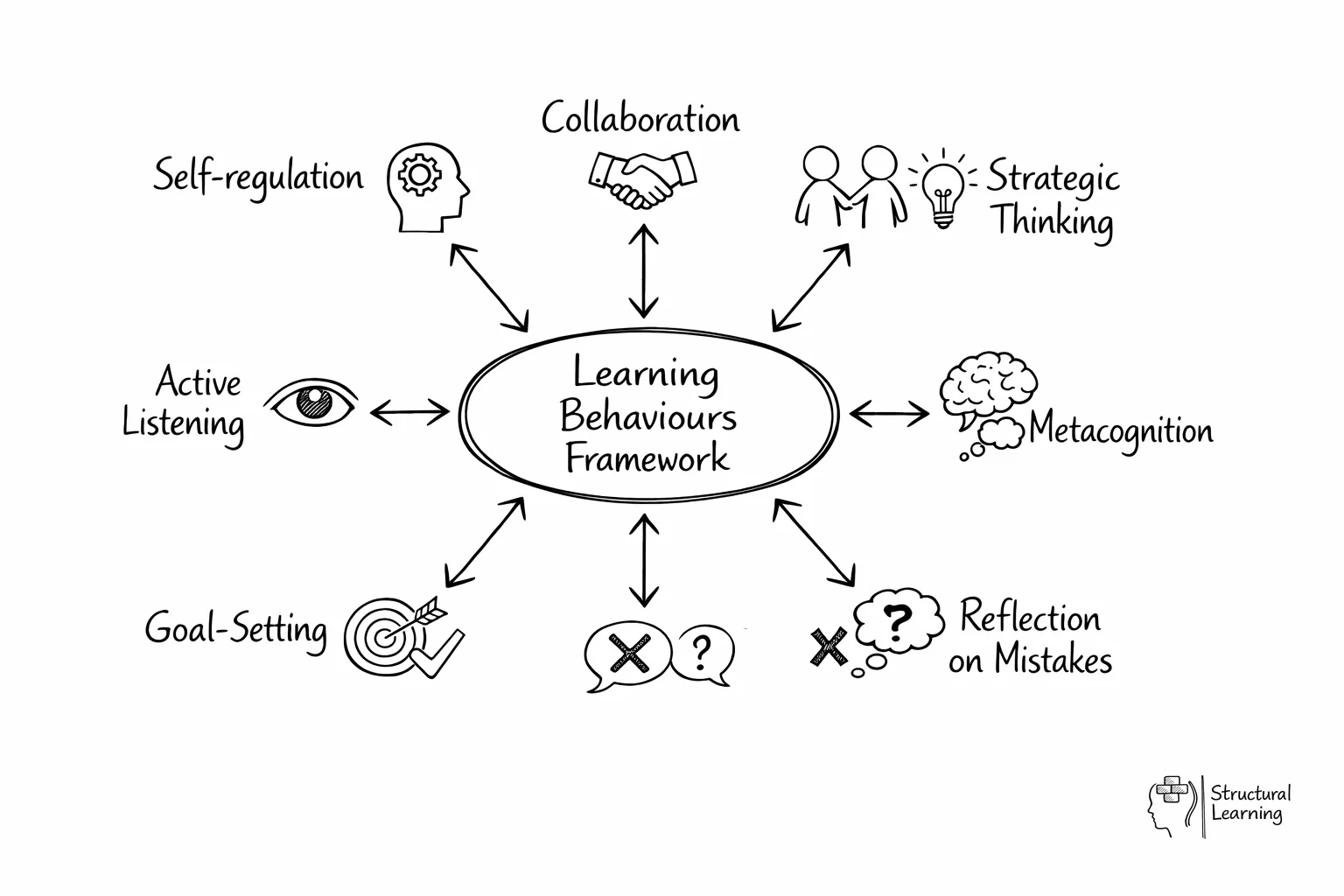

Research shows that such behaviours are not fixed traits; they can be taught, practised, and strengthened just like reading fluency or number sense. That's why the Structural Learning team built a Learning Behaviours Framework, a clear roadmap that tracks how from "novice" to "expert" in areas such as self-regulation, collaboration, and strategic thinking. When teachers have shared language for these behaviours, classroom routines become sharper, feedback gets more precise, and pupils see exactly what "good learning" looks and feels like.

But the benefits reach beyond tidy lessons. Schools that embed learning behaviours report calmer corridors, richer dialogue, and higher-quality work because every adult is reinforcing the same expectations. Effective pedagogy and strong relationships still matter, of course, yet those elements thrive when students arrive ready to listen, grapple with ideas, and support one another.

This article unpacks practical ways to cultivate the positives (e.g., goal-setting, ) and curb the negatives (e.g., task avoidance, low-level disruption). Use the ideas to fine-tune your classroom management, align whole-school culture, and give every learner the tools to succeed both now and in the years ahead.

Teachers implement learning behaviours by using the Learning Behaviours Framework to identify specific skills like self-regulation and collaboration that need development. Start by modelling these behaviours explicitly, then provide structured practice opportunities with clear feedback. Track student progress from novice to expert levels using observable actions and shared language across all lessons.

Why do some pupils thrive when others switch off? The answer sits at the crossroads of . A handful of classic theories offer practical clues:

- Skinner's Operant Conditioning reminds us that what gets reinforced gets repeated. Praise, feedback tokens, or simple acknowledgement can lock in positive learning behaviours far more effectively than reprimands alone.

- Attribution Theory warns that if children blame setbacks on luck or teacher bias, they can slide into "why bother?" mode. Reframing success and failure around effort helps nurture a growth mindset.

- Social Loafing shows that group tasks sometimes hide passengers. Establishing clear individual roles, and celebrating each one, keeps every learner accountable.

Beyond behaviourism, personality lenses matter too. highlight neurodiversity: a "Thinker" may crave logic and clear criteria, while an "Explorer" thrives on open- ended challenge. Matching task style to learner preference can prevent frustration before it starts.

Context also shapes conduct. , along with , remind us that family expectations, peer norms, and community values spill into the classroom daily. A behaviour plan that ignores those wider forces rarely sticks.

Finally, motivation research, especially, flags three universal drivers: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When lessons offer choice, achievable stretch, and a sense of belonging, pro-social behaviours rise and disruption falls.

A recent review by the Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation found that classrooms using structured behaviour-for-learning strategies enjoyed a 20 % boost in academic engagement. Theory, in other words, isn't ivory-tower garnish; it's a toolkit for developing potential.

Developing learning behaviours involves teaching observable actions like active listening, goal-setting, and reflecting on mistakes through modelling, practice, and structured cooperative learning. Students need to see these behaviours demonstrated, practice them with support, and receive specific feedback to develop metacognition about their learning processes. This approach helps learners become more independent a nd develop critical thinking skills while building confidence in their ability to learn effectively.

Developing learning behaviours requires a systematic approach that builds skills progressively. Research by Carol Dweck emphasises the importance of starting with mindset development, helping students understand that abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work.

Model the behaviours explicitly - Demonstrate specific learning behaviours during lessons, thinking aloud as you work through problems or approach new concepts. Students need to see what effective learning looks like in practice. For instance, show how you approach a challenging text by asking questions, making connections, or revisiting difficult sections. Practice behaviours in low-stakes situations - Introduce new learning behaviours during familiar activities before applying them to challenging content. This allows students to focus on the behaviour itself rather than being overwhelmed by difficult material.

Provide consistent feedback and recognition - Acknowledge when students demonstrate positive learning behaviours, being specific about what they did well. Paul Black's research on formative assessment shows that targeted feedback accelerates behaviour development. Create opportunities for reflection - Build in regular moments for students to evaluate their own learning behaviours and set goals for improvement. This develops metacognitive awareness and personal ownership of the learning process. Remember that behaviour chan ge takes time and patience, with some students requiring additional scaffolding or individualised approaches.

Effective assessment of learning behaviours requires systematic observation and data collection rather than relying on subjective impressions. Teachers should establish clear, observable indicators for each target behaviour, such as "maintains focus for 10-minute intervals" or "seeks help appropriately when stuck." Regular tracking through simple charts, checklists, or brief anecdotal notes enables educators to identify patterns and measure progress objectively. Frequency and duration are particularly useful metrics, as they provide concrete evidence of improvement over time.

Carol Dweck's research on growth mindset emphasises the importance of monitoring both behavioural changes and students' underlying attitudes towards learning. Teachers can gather this information through brief student self-assessments, peer observations, or structured conversations about learning experiences. Weekly reflection sessions allow students to articulate their own progress, developing metacognitive awareness whilst providing valuable insights into their developing learning behaviours.

Implementation should focus on manageable data collection that fits naturally into classroom routines. A simple traffic light system, where students self-assess their engagement levels at lesson transitions, can provide immediate feedback without disrupting learning flow. Similarly, brief exit tickets asking students to identify one successful learning behaviour from the session create accountability whilst building self-awareness. This ongoing monitoring enables teachers to adjust interventions promptly and celebrate incremental improvements with students.

Learning behaviours evolve significantly as students mature, requiring educators to adapt their approaches to match developmental stages. Primary school children typically respond well to concrete, structured routines with clear visual cues and immediate feedback, as their executive function skills are still developing. In contrast, secondary students benefit from greater autonomy and can engage with more abstract behavioural expectations, though they require different support systems to navigate increased social complexities and academic pressures.

John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates why age-appropriate scaffolding is crucial for developing effective learning behaviours. Younger learners need explicit modelling of behaviours such as active listening and turn-taking, with frequent practice opportunities built into daily routines. Secondary students, however, can handle more sophisticated metacognitive strategies, learning to self-regulate their attention and monitor their own engagement levels during extended learning activities.

Successful classroom implementation requires recognising these developmental differences in practice. Primary teachers might use movement breaks, visual behaviour charts, and peer partnerships to support attention and collaboration, whilst secondary educators can introduce goal-setting frameworks, reflection journals, and student-led discussions about learning strategies. Both approaches should maintain high expectations whilst providing developmentally appropriate support structures that help students internalise positive learning behaviours over time.

Even the most carefully planned behaviour programmes face predictable hurdles that can discourage educators from maintaining their efforts. Inconsistent implementation across different staff members often undermines progress, whilst student resistance to new expectations can feel overwhelming in the initial weeks. Research by John Hattie consistently shows that programmes abandoned too early miss the crucial consolidation phase where learning behaviours become genuinely embedded.

The most effective troubleshooting approach involves systematic problem-solving rather than wholesale programme changes. When students struggle with specific learning behaviours, examine whether the expectations are developmentally appropriate and clearly communicated. Daniel Willingham's cognitive research suggests that many behaviour challenges stem from unclear instructions rather than defiance, particularly when students face high cognitive load from competing demands.

Address resistance by involving students in reviewing and refining behaviour expectations, creating ownership rather than compliance. Celebrate small wins publicly whilst addressing setbacks privately, maintaining the positive classroom environment essential for sustained change. Remember that embedding new learning behaviours typically requires 6-8 weeks of consistent practice, so persistence through the inevitable dips in progress separates successful programmes from abandoned ones.

Every lesson is a tug-of-war between time and attention. When pupils arrive with the right habits, listening actively, tackling tasks with curiosity, reflecting on mistakes, the rope moves effortlessly in your favour. These habits are what we call Learning Behaviours: observable actions that help children take charge of their own progress and work productively with others.

Research shows that such behaviours are not fixed traits; they can be taught, practised, and strengthened just like reading fluency or number sense. That's why the Structural Learning team built a Learning Behaviours Framework, a clear roadmap that tracks how from "novice" to "expert" in areas such as self-regulation, collaboration, and strategic thinking. When teachers have shared language for these behaviours, classroom routines become sharper, feedback gets more precise, and pupils see exactly what "good learning" looks and feels like.

But the benefits reach beyond tidy lessons. Schools that embed learning behaviours report calmer corridors, richer dialogue, and higher-quality work because every adult is reinforcing the same expectations. Effective pedagogy and strong relationships still matter, of course, yet those elements thrive when students arrive ready to listen, grapple with ideas, and support one another.

This article unpacks practical ways to cultivate the positives (e.g., goal-setting, ) and curb the negatives (e.g., task avoidance, low-level disruption). Use the ideas to fine-tune your classroom management, align whole-school culture, and give every learner the tools to succeed both now and in the years ahead.

Teachers implement learning behaviours by using the Learning Behaviours Framework to identify specific skills like self-regulation and collaboration that need development. Start by modelling these behaviours explicitly, then provide structured practice opportunities with clear feedback. Track student progress from novice to expert levels using observable actions and shared language across all lessons.

Why do some pupils thrive when others switch off? The answer sits at the crossroads of . A handful of classic theories offer practical clues:

- Skinner's Operant Conditioning reminds us that what gets reinforced gets repeated. Praise, feedback tokens, or simple acknowledgement can lock in positive learning behaviours far more effectively than reprimands alone.

- Attribution Theory warns that if children blame setbacks on luck or teacher bias, they can slide into "why bother?" mode. Reframing success and failure around effort helps nurture a growth mindset.

- Social Loafing shows that group tasks sometimes hide passengers. Establishing clear individual roles, and celebrating each one, keeps every learner accountable.

Beyond behaviourism, personality lenses matter too. highlight neurodiversity: a "Thinker" may crave logic and clear criteria, while an "Explorer" thrives on open- ended challenge. Matching task style to learner preference can prevent frustration before it starts.

Context also shapes conduct. , along with , remind us that family expectations, peer norms, and community values spill into the classroom daily. A behaviour plan that ignores those wider forces rarely sticks.

Finally, motivation research, especially, flags three universal drivers: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When lessons offer choice, achievable stretch, and a sense of belonging, pro-social behaviours rise and disruption falls.

A recent review by the Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation found that classrooms using structured behaviour-for-learning strategies enjoyed a 20 % boost in academic engagement. Theory, in other words, isn't ivory-tower garnish; it's a toolkit for developing potential.

Developing learning behaviours involves teaching observable actions like active listening, goal-setting, and reflecting on mistakes through modelling, practice, and structured cooperative learning. Students need to see these behaviours demonstrated, practice them with support, and receive specific feedback to develop metacognition about their learning processes. This approach helps learners become more independent a nd develop critical thinking skills while building confidence in their ability to learn effectively.

Developing learning behaviours requires a systematic approach that builds skills progressively. Research by Carol Dweck emphasises the importance of starting with mindset development, helping students understand that abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work.

Model the behaviours explicitly - Demonstrate specific learning behaviours during lessons, thinking aloud as you work through problems or approach new concepts. Students need to see what effective learning looks like in practice. For instance, show how you approach a challenging text by asking questions, making connections, or revisiting difficult sections. Practice behaviours in low-stakes situations - Introduce new learning behaviours during familiar activities before applying them to challenging content. This allows students to focus on the behaviour itself rather than being overwhelmed by difficult material.

Provide consistent feedback and recognition - Acknowledge when students demonstrate positive learning behaviours, being specific about what they did well. Paul Black's research on formative assessment shows that targeted feedback accelerates behaviour development. Create opportunities for reflection - Build in regular moments for students to evaluate their own learning behaviours and set goals for improvement. This develops metacognitive awareness and personal ownership of the learning process. Remember that behaviour chan ge takes time and patience, with some students requiring additional scaffolding or individualised approaches.

Effective assessment of learning behaviours requires systematic observation and data collection rather than relying on subjective impressions. Teachers should establish clear, observable indicators for each target behaviour, such as "maintains focus for 10-minute intervals" or "seeks help appropriately when stuck." Regular tracking through simple charts, checklists, or brief anecdotal notes enables educators to identify patterns and measure progress objectively. Frequency and duration are particularly useful metrics, as they provide concrete evidence of improvement over time.

Carol Dweck's research on growth mindset emphasises the importance of monitoring both behavioural changes and students' underlying attitudes towards learning. Teachers can gather this information through brief student self-assessments, peer observations, or structured conversations about learning experiences. Weekly reflection sessions allow students to articulate their own progress, developing metacognitive awareness whilst providing valuable insights into their developing learning behaviours.

Implementation should focus on manageable data collection that fits naturally into classroom routines. A simple traffic light system, where students self-assess their engagement levels at lesson transitions, can provide immediate feedback without disrupting learning flow. Similarly, brief exit tickets asking students to identify one successful learning behaviour from the session create accountability whilst building self-awareness. This ongoing monitoring enables teachers to adjust interventions promptly and celebrate incremental improvements with students.

Learning behaviours evolve significantly as students mature, requiring educators to adapt their approaches to match developmental stages. Primary school children typically respond well to concrete, structured routines with clear visual cues and immediate feedback, as their executive function skills are still developing. In contrast, secondary students benefit from greater autonomy and can engage with more abstract behavioural expectations, though they require different support systems to navigate increased social complexities and academic pressures.

John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates why age-appropriate scaffolding is crucial for developing effective learning behaviours. Younger learners need explicit modelling of behaviours such as active listening and turn-taking, with frequent practice opportunities built into daily routines. Secondary students, however, can handle more sophisticated metacognitive strategies, learning to self-regulate their attention and monitor their own engagement levels during extended learning activities.

Successful classroom implementation requires recognising these developmental differences in practice. Primary teachers might use movement breaks, visual behaviour charts, and peer partnerships to support attention and collaboration, whilst secondary educators can introduce goal-setting frameworks, reflection journals, and student-led discussions about learning strategies. Both approaches should maintain high expectations whilst providing developmentally appropriate support structures that help students internalise positive learning behaviours over time.

Even the most carefully planned behaviour programmes face predictable hurdles that can discourage educators from maintaining their efforts. Inconsistent implementation across different staff members often undermines progress, whilst student resistance to new expectations can feel overwhelming in the initial weeks. Research by John Hattie consistently shows that programmes abandoned too early miss the crucial consolidation phase where learning behaviours become genuinely embedded.

The most effective troubleshooting approach involves systematic problem-solving rather than wholesale programme changes. When students struggle with specific learning behaviours, examine whether the expectations are developmentally appropriate and clearly communicated. Daniel Willingham's cognitive research suggests that many behaviour challenges stem from unclear instructions rather than defiance, particularly when students face high cognitive load from competing demands.

Address resistance by involving students in reviewing and refining behaviour expectations, creating ownership rather than compliance. Celebrate small wins publicly whilst addressing setbacks privately, maintaining the positive classroom environment essential for sustained change. Remember that embedding new learning behaviours typically requires 6-8 weeks of consistent practice, so persistence through the inevitable dips in progress separates successful programmes from abandoned ones.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/developing-behaviours-for-learning#article","headline":"Developing Behaviours for Learning","description":"Behaviour for Learning: A teacher's guide to building the academic skills of a life-long learner.","datePublished":"2021-07-30T16:30:47.113Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/developing-behaviours-for-learning"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a40a43fa1eb65bdc0041f_696a409f426ee673941cd90a_developing-behaviours-for-learning-illustration.webp","wordCount":3552},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/developing-behaviours-for-learning#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Developing Behaviours for Learning","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/developing-behaviours-for-learning"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What Are Behaviours for Learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Every lesson is a tug-of-war between time and attention. When pupils arrive with the right habits, listening actively, tackling tasks with curiosity, reflecting on mistakes, the rope moves effortlessly in your favour. These habits are what we call Learning Behaviours : observable actions that help children take charge of their own progress and work productively with others."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Do You Implement Learning Behaviours in the Classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers implement learning behaviours by using the Learning Behaviours Framework to identify specific skills like self-regulation and collaboration that need development. Start by modelling these behaviours explicitly, then provide structured practice opportunities with clear feedback. Track student progress from novice to expert levels using observable actions and shared language across all lessons."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Are the Steps to Develop Learning Behaviours in Students?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Developing learning behaviours involves teaching observable actions like active listening, goal-setting, and reflecting on mistakes through modelling , practice, and structured cooperative learning. Students need to see these behaviours demonstrated, practice them with support, and receive specific feedback to develop metacognition about their learning processes. This approach helps learners become more independent a nd develop critical thinking skills while building confidence in their ability "}}]}]}