Bandura's Social Learning Theory: Observational Learning and the Bobo Doll Study

Explore Bandura's Social Learning Theory and the famous Bobo doll experiment. Discover how children learn through observation and imitation.

Explore Bandura's Social Learning Theory and the famous Bobo doll experiment. Discover how children learn through observation and imitation.

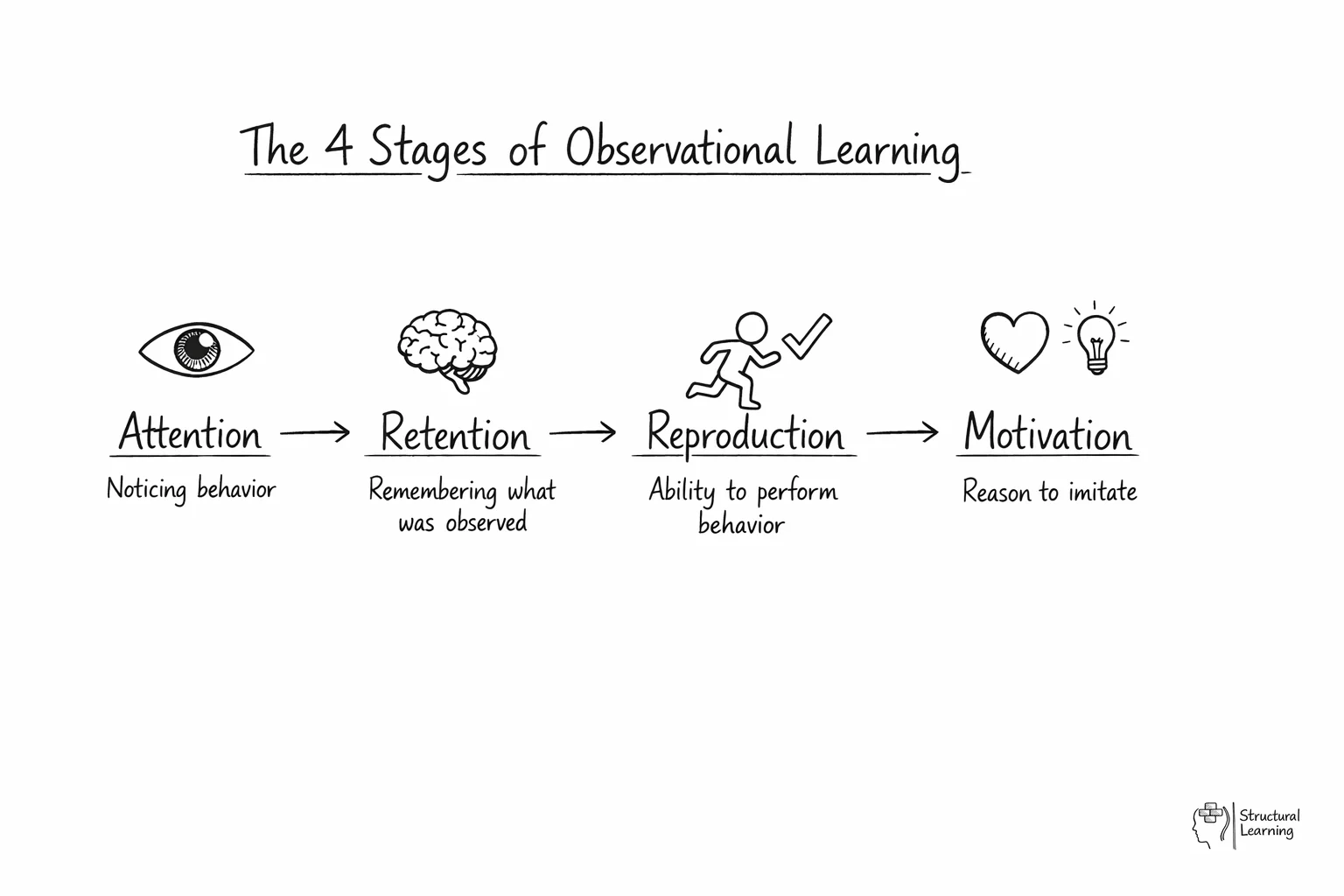

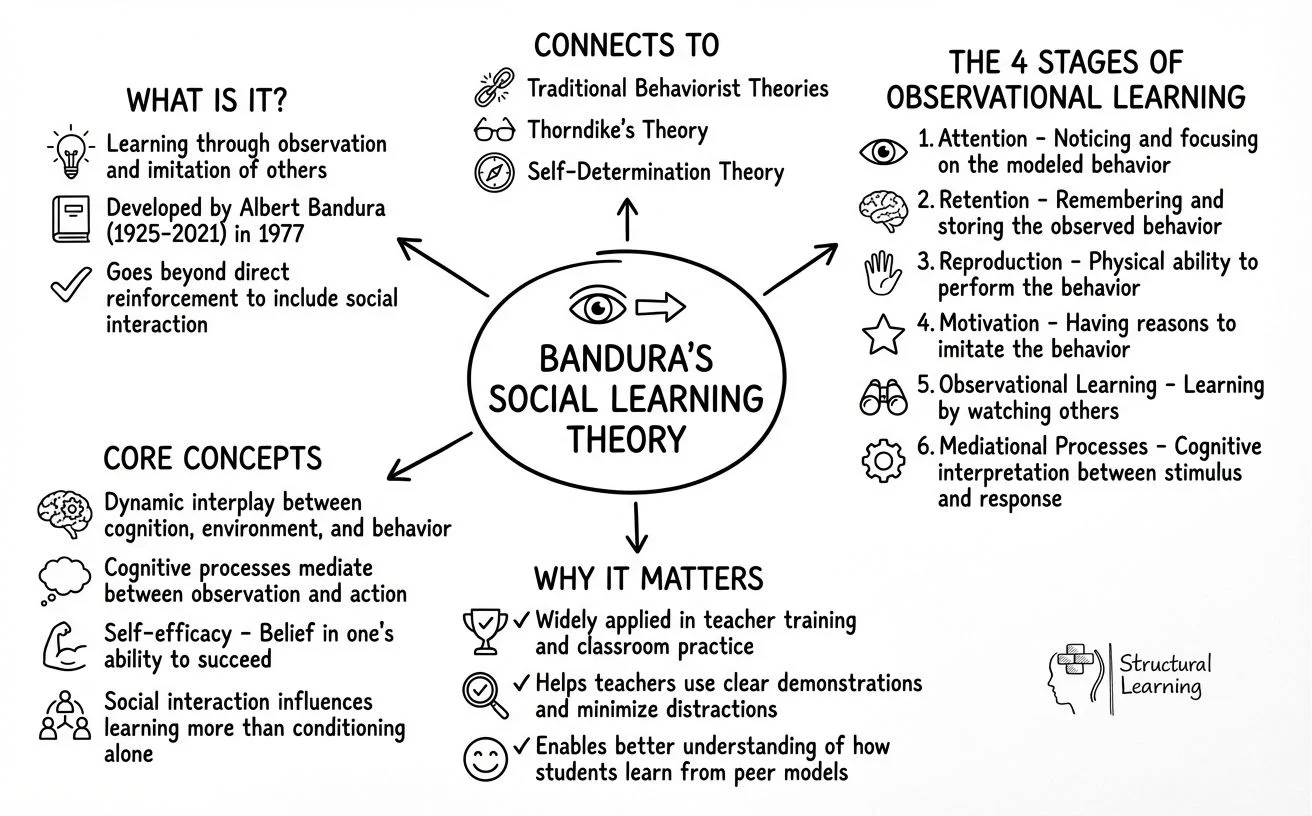

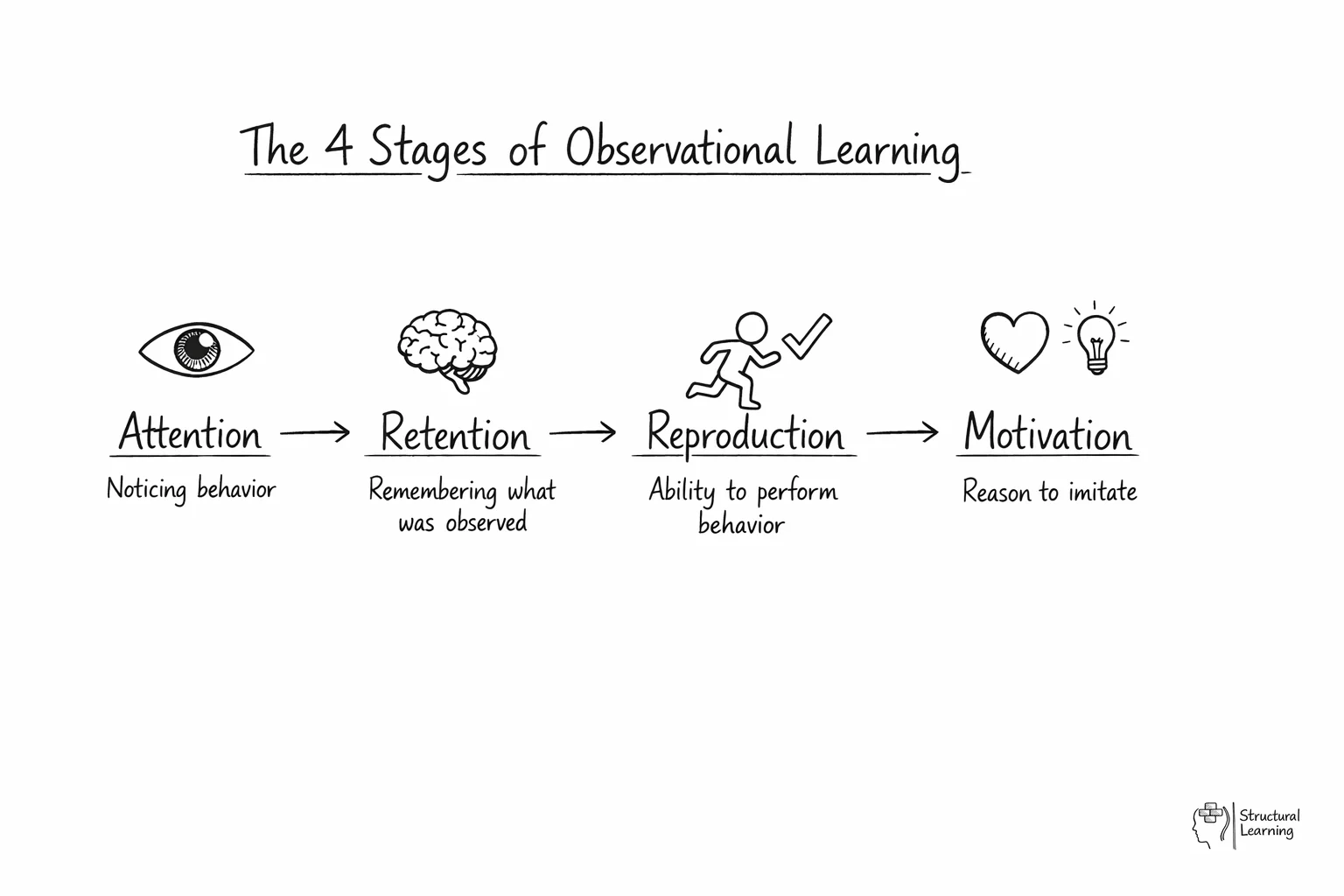

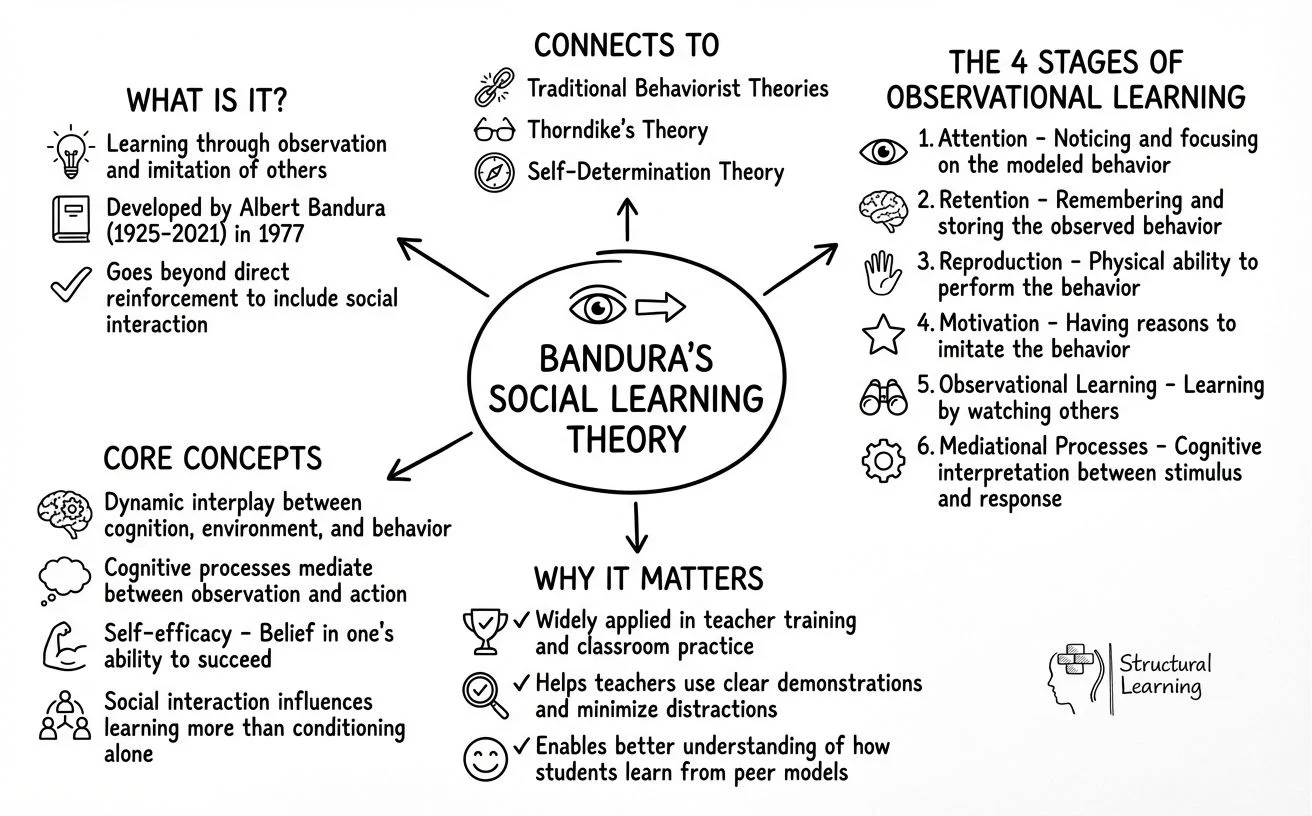

Albert Bandura's Social Learning Theory revolutionised our understanding of how people learn by demonstrating that we acquire new behaviours simply by watching others, rather than needing direct rewards or punishments. This groundbreaking concept was famously proven through Bandura's iconic Bobo Doll experiment in the 1960s, where children who observed adults attacking an inflatable doll later mimicked the same aggressive behaviours. The theory centres on four key cognitive processes: paying attention to the behaviour, remembering what was observed, having the ability to reproduce it, and being motivated to imitate it. But what made those children in the laboratory so quick to copy violence, and what does this reveal about how we all learn throughout our lives?

Albert Bandura (1925-2021) transformed our understanding of how people learn by proposing that individuals acquire new behaviours through observing and imitating the actions of others. Unlike earlier behaviourist models, which emphasised direct reinforcement, Bandura introduced the idea that learning can occur through social interaction and observation alone. His theory provided an alternative to the work of earlier education theorists, who focused on direct reinforcement, and expanded on existing theories of learning by incorporating cognitive and environmental influences. In 2025, Bandura's framework remains one of the most widely applied theories in teacher training and classroom practise.

According to Bandura, learning isn't solely the result of conditioning but involves a active interplay between cognition, environment, and behaviour. He identified two key processes that differentiate social learning from traditional behaviourist theories:

| Stage/Level | Age Range | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention | All ages | Noticing and focusing on the modelled behaviour, selective observation of relevant features | Teachers should ensure behaviours are distinctive, use clear demonstrations, minimise distractions |

| Retention | All ages | Remembering and storing the observed behaviour through mental images or verbal descriptions | Use repetition, provide opportunities for mental rehearsal, connect to prior knowledge |

| Reproduction | All ages | Physical and cognitive ability to perform the observed behaviour, converting memory into action | Break complex behaviours into steps, provide guided practise, ensure developmental readiness |

| Motivation | All ages | Having reasons to imitate the behaviour, influenced by reinforcement and consequences observed | Highlight positive outcomes, use peer models, create meaningful rewards for learning |

Born in 1925 in Canada, Bandura earned his PhD at the University of Iowa in 1952 and later became one of the most influential psychologists of the 20th century. His 1977 book, Social Learning Theory, formalised his ideas and demonstrated how children and adults learn from modelled behaviours. One of his most well-known experiments, the Bobo doll study, showed how children imitate aggression after witnessing it in adults, reinforcing his argument that learning is largely influenced by social exposure.

Beyond education, Bandura's theory has been applied in parenting, workplace training, media studies, and behavioural therapy. His work also led to the development of self-efficacy, the belief in one's ability to succeed. Bandura argued that higher self-efficacy leads to greater achievement, shaping how individuals approach learning, challe nges, and personal growth.

The Bobo doll experiment, conducted in 1961 at Stanford University, stands as one of the most influential studies in the history of psychology. Albert Bandura designed this groundbreaking research to test a fundamental question: Can children learn aggressive behaviours simply by observing adults, without any direct reinforcement? The study challenged the dominant behaviourist theories of the time, which insisted that learning required direct experience of rewards or punishments.

Bandura's experimental design was methodical and carefully controlled. He recruited 72 children (36 boys and 36 girls) aged between 3 and 6 years from the Stanford University Nursery School. The children were divided into three main experimental groups, with equal numbers of boys and girls in each condition to control for potential gender differences in aggressive behaviour.

The first group observed an adult model behaving aggressively towards a five-foot inflatable Bobo doll. The adult model entered a playroom and, after a brief period of play with other toys, began a sustained physical and verbal assault on the Bobo doll. The aggressive behaviours were highly distinctive and included punching the doll, hitting it with a mallet, throwing it in the air, and kicking it around the room. Crucially, the adult also used specific verbal aggression, shouting phrases such as "Sock him in the nose!" and "Pow!" These distinctive verbal and physical behaviours made it easy to identify clear copying when children were later observed.

The second group observed a non-aggressive adult model who completely ignored the Bobo doll and played quietly with other toys in the room for the same duration. This condition served as a control to demonstrate that mere exposure to the doll and playroom environment didn't automatically trigger aggression.

The third group was a control group that had no exposure to any adult model. These children simply played in the room without witnessing any modelled behaviour, providing a baseline measure of children's natural aggression levels towards the Bobo doll.

An additional experimental condition examined the effect of model gender. Some children observed same-sex models whilst others observed opposite-sex models, allowing Bandura to investigate whether children were more likely to imitate models of their owngender, a hypothesis supported by social learning theory.

After exposure to the model, each child was individually taken to a different room filled with attractive toys. To create mild frustration and increase the likelihood of aggressive responses, the experimenter told the children after two minutes that these toys were reserved for other children. The children were then taken to a third room containing both aggressive toys (such as mallets and dart guns) and non-aggressive toys, along with the Bobo doll. Observers behind a one-way mirror recorded the children's behaviour for 20 minutes.

The results were striking and unambiguous. Children who had observed the aggressive model reproduced a significant amount of the physically and verbally aggressive behaviour they had witnessed. They didn't simply show more general aggression; they performed precise imitations of the specific actions and words used by the adult model. Children who had observed the aggressive model were statistically far more aggressive than those in either the non-aggressive or control conditions.

Bandura found that boys were significantly more aggressive than girls overall, but girls who had observed aggressive female models showed aggression levels comparable to boys. This suggested that whilst biological factors might predispose boys to higher baseline aggression, observational learning could powerfully override these tendencies. The study also revealed that children were more likely to imitate same-sex models, particularly for physical aggression, supporting the role of identification in observational learning.

Perhaps most concerning from an applied perspective, children often exhibited novel aggressive behaviours that went beyond mere imitation. They improvised new ways to attack the doll, demonstrating that observational learning didn't just produce rote copying but could inspire creative variations on observed themes.

The Bobo doll experiment had profound implications that extended far beyond the psychology laboratory. It provided compelling evidence that children are highly susceptible to social influences and can acquire complex behaviours through observation alone, without needing direct reinforcement. This finding transformed understanding of child development and had immediate practical applications.

For educators, the study underscored the critical importance of teacher modelling. Children in classrooms don't just learn academic content; they constantly observe and absorb behavioural patterns demonstrated by adults and peers. Teachers who model respectful communication, problem-solving strategies, and emotional regulation effectively teach these behaviours to their students through observational learning. Conversely, displays of frustration, sarcasm, or dismissive behaviour can be equally readily acquired.

The experiment also raised significant concerns about media violence and its impact on children. Children could learn and copy aggressive behaviours after just a few minutes of observation in a laboratory setting. What might be the combined effect of hours of exposure to violence in television programmes, films, and video games? This question sparked decades of subsequent research and continues to inform debates about media regulation and parental guidance.

From a classroom management perspective, the Bobo doll study highlighted the need for consistent modelling of positive behaviours. Children learn not just from what teachers explicitly teach but from everything they observe, including how teachers handle stress, resolve conflicts, and interact with different students. The study suggested that creating a positive classroom culture requires deliberate attention to the behaviours being modelled throughout the school day.

Bandura identified four essential processes that determine whether observational learning occurs effectively: attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation. These sequential stages must all function successfully for learners to acquire new behaviours through modelling. Understanding each process in depth enables educators to design learning experiences that maximise the power of observational learning.

The attention process represents the first critical stage of observational learning. Learners cannot acquire behaviours they haven't noticed, making attention the gateway through which all observational learning must pass. However, attention isn't a simple on-off switch; it involves selective focus on relevant aspects of the model's behaviour whilst filtering out irrelevant details.

Several factors influence whether learners attend to a model's behaviour. The distinctiveness of the behaviour plays a important role; unusual, vivid, or clearly demonstrated actions capture attention more effectively than subtle or commonplace behaviours. This explains why teachers often exaggerate certain aspects of demonstrations, using dramatic gestures or emphatic language to ensure students notice critical features.

The characteristics of the model also significantly affect attention. Learners pay more attention to models they perceive as competent, attractive, powerful, or similar to themselves. In classroom settings, this means peer models can be particularly effective, especially when students perceive the demonstrating peer as comparable in ability rather than exceptionally talented. A struggling student who successfully masters a technique may provide a more compelling model than the highest-achieving student in the class.

Functional value influences attention as well. Learners are more likely to attend carefully to behaviours they believe will be useful or valuable to them. Teachers can improve attention by explicitly explaining why a particular strategy or skill matters, connecting it to students' goals or interests. When students understand that a demonstrated study technique will help them remember content more effectively, they attend more carefully to the demonstration.

Environmental factors also matter enormously. Distractions, competing stimuli, and poor visibility all undermine attention. Effective modelling requires minimising distractions, ensuring clear sight lines, and creating an environment where the demonstrated behaviour stands out clearly from the background. This is why many teachers instinctively call for silence and direct visual attention before beginning demonstrations.

Attention alone cannot produce learning; observed behaviours must be encoded into memory in a form that permits later retrieval and reproduction. The retention process involves transforming observed actions into mental representations that can be stored and accessed when needed. Bandura identified two primary coding systems through which retention occurs: imaginal and verbal.

Imaginal coding involves creating vivid mental images of the observed behaviour. When a student watches a teacher demonstrate how to conduct a science experiment, they form visual memories of each step, the equipment arrangement, and the movements involved. These mental images serve as internal models that can be mentally rehearsed and later retrieved during actual performance.

Verbal coding involves describing the observed behaviour in words, creating a linguistic representation that can be more easily stored and recalled than pure imagery. A student might internally narrate "First, measure 50ml of water, then add three drops of indicator, swirl gently, and observe the colour change." This verbal encoding complements visual representation and often lasts longer in long-term memory.

Teachers can significantly improve retention through several strategies. Repetition of demonstrations allows multiple encoding opportunities, strengthening memory traces. Encouraging mental rehearsal, where students mentally walk through the observed behaviour whilst seated, reinforces retention without requiring physical practise. Connecting new observations to existing knowledge schemas creates retrieval paths that make memories more accessible.

The use of verbal labelling during demonstrations proves particularly powerful. When teachers simultaneously demonstrate and describe their actions, they provide both imaginal and verbal coding opportunities, supporting dual encoding. Research on Allan Paivio's dual coding theory confirms that information encoded in multiple formats is remembered more effectively than single-format encoding.

Time delays between observation and performance opportunity affect retention significantly. Without rehearsal, memory traces decay rapidly. Teachers should provide opportunities for relatively prompt practise after demonstrations, whilst the memory remains fresh and accessible. Alternatively, structured review sessions help students reactivate and consolidate memories before they fade completely.

Even with perfect attention and retention, learning remains incomplete until the learner can physically or cognitively reproduce the observed behaviour. The reproduction process requires translating mental representations into actual performance, a stage that depends heavily on the learner's existing capabilities and developmental readiness.

Physical capabilities constrain what behaviours can be reproduced. A young child who observes an adult performing a complex motor skill may attend perfectly and retain a clear memory yet lack the physical coordination, strength, or fine motorcontrol to execute the action. Teachers must ensure that demonstrated behaviours match students' developmental capabilities or provide scaffolded approaches that break complex actions into achievable components.

Cognitive capabilities similarly affect reproduction. Understanding the principles underlying a demonstrated problem-solving strategy requires sufficient cognitive development and background knowledge. A student who observes a teacher using algebraic manipulation may lack the conceptual understanding to reproduce the steps meaningfully, even with perfect memory of the procedure.

Feedback during initial reproduction attempts proves important. Learners rarely execute observed behaviours perfectly on the first attempt; they need corrective information to align their performance with the observed model. This feedback can come from teachers, peers, or self-monitoring against remembered images of the model's performance. The quality and timing of feedback significantly influence how quickly learners achieve accurate reproduction.

Practise plays an essential role in moving from approximate to precise reproduction. Initial attempts typically capture the general form of the behaviour, but refinement requires repeated practise with attention to details. Teachers help this process by breaking complex behaviours into manageable components, allowing students to master each element before combining them into the complete performance.

Self-efficacy beliefs powerfully influence reproduction attempts. Students who doubt their capability to perform an observed behaviour may not attempt reproduction at all, despite perfect attention and retention. Building confidence through graduated difficulty, ensuring early successes, and highlighting progress all support students' willingness to attempt reproduction of observed behaviours.

The motivation process represents the final stage of observational learning and addresses a important distinction Bandura made between acquisition and performance. Students may successfully attend to, retain, and possess the capability to reproduce an observed behaviour yet choose not to perform it. Motivation determines whether learned behaviours are actually enacted.

Bandura identified three types of reinforcement that influence motivation: direct reinforcement, vicarious reinforcement, and self-reinforcement. Direct reinforcement occurs when learners personally experience positive consequences for performing the behaviour. A student who receives praise after using a problem-solving strategy observed from a teacher becomes more motivated to use that strategy again.

Vicarious reinforcement operates through observation of consequences experienced by others. When students observe peers being praised, rewarded, or successful after performing particular behaviours, they become more motivated to attempt those behaviours themselves. This process proves particularly powerful in classroom settings where teachers can strategically highlight and reward desired behaviours, allowing the entire class to vicariously experience the positive consequences.

Conversely, vicarious punishment occurs when students observe others experiencing negative consequences for behaviours. Watching a peer receive criticism for calling out answers without raising their hand reduces other students' motivation to engage in the same behaviour, even if they had previously considered it.

Self-reinforcement involves learners' internal evaluation of their own performance against personal standards. Students who observe expert performance develop internal standards for quality, and they experience satisfaction (self-reinforcement) when their own performance meets these standards. This self-evaluative process becomes increasingly important as learners develop greater autonomy and self-regulation.

The anticipated consequences of behaviour, based on observed outcomes for others and past personal experience, critically influence motivation. Students engage in cognitive evaluation, mentally weighing the likely benefits and costs of performing an observed behaviour before deciding whether to attempt it. Teachers can influence this calculation by ensuring that positive behaviours consistently lead to valued outcomes whilst negative behaviours reliably produce undesirable consequences.

Intrinsic interest in the behaviour itself also motivates performance. When observed behaviours appear engaging, enjoyable, or intellectually satisfying, students feel motivated to attempt them regardless of external reinforcement. Teachers who demonstrate genuine enthusiasm and interest in their subject matter model intrinsic motivation, potentially inspiring similar attitudes in students.

Whilst Bandura's social learning theory gained widespread recognition through the Bobo doll experiments, his development of self-efficacy theory arguably represents his most enduring contribution to educational psychology. Self-efficacy refers to an individual's belief in their capacity to execute behaviours necessary to produce specific performance attainments. It represents not what people can objectively do, but what they believe they can do, and this belief profoundly influences their actual performance.

Bandura identified four primary sources through which self-efficacy beliefs develop, each carrying different weight in shaping individuals' confidence in their abilities.

1. Mastery Experiences: The most powerful source of self-efficacy comes from direct experiences of successfully completing challenging tasks. When students work hard and succeed, they develop strong beliefs in their capabilities. Critically, success on easy tasks provides little efficacy information; it's overcoming difficulties through persistent effort that builds genuine confidence. Teachers who provide appropriately challenging tasks that students can master through sustained effort create the optimal conditions for self-efficacy development. Conversely, repeated failures, especially early in learning, severely undermine efficacy beliefs, making students hesitant to attempt challenging work.

2. Vicarious Experiences: Observing others successfully complete tasks provides efficacy information, especially when the observed models are similar to the observer. When students see peers they consider comparable to themselves succeed, they think, "If they can do it, so can I." The perceived similarity between model and observer determines the power of vicarious experience. A struggling student gains more efficacy from watching another struggling student succeed through effort than from observing a naturally talented student succeed effortlessly. This explains why peer modelling often proves more effective than teacher modelling for building student confidence, particularly when the teacher is perceived as exceptionally competent.

3. Verbal Persuasion: Encouragement and positive feedback from trusted others can strengthen self-efficacy, though this source proves weaker than mastery or vicarious experiences. Effective persuasion must be realistic and credible; hollow praise or encouragement to attempt tasks clearly beyond current capabilities damages credibility and can actually undermine efficacy. Teachers who provide specific, process-focused feedback ("You used effective strategies and worked systematically through the problem") build efficacy more effectively than vague praise ("You're so clever"). The persuader's credibility and expertise significantly influence the impact of verbal persuasion.

4. Physiological and Emotional States: People interpret their emotional and physical reactions as indicators of capability. Anxiety, stress, fatigue, and negative mood can be interpreted as signs of inadequacy, undermining efficacy. Conversely, calm confidence and positive emotional states support efficacy beliefs. Teachers can influence this source by helping students reinterpret physiological arousal (a racing heart before a test) as excitement and readiness rather than anxiety and inadequacy. Creating calm, supportive classroom environmentsreduces the negative physiological states that undermine confidence.

Self-efficacy beliefs exert powerful influence on academic achievement through several mechanisms. Students with high self-efficacy approach difficult tasks as challenges to master rather than threats to avoid. They set challenging goals, maintain strong commitment, and persist through setbacks. When faced with failure, high-efficacy students attribute it to insufficient effort or inadequate strategies, both factors they can control and change. They approach threatening situations with confidence that they can exercise control.

In contrast, students with low self-efficacy avoid challenging tasks, give up quickly when encountering difficulties, and attribute failure to low ability, a stable factor they believe they cannot change. They dwell on personal deficiencies and potential difficulties rather than concentrating on how to perform successfully. This creates self-fulfilling prophecies: low efficacy leads to reduced effort and persistence, producing poor performance that confirms the initial negative belief.

Domain-specific nature of self-efficacy proves important for teachers to understand. A student might possess high self-efficacy for mathematics but low self-efficacy for writing. Generic confidence-building proves less effective than developing specific self-efficacy in particular academic domains through targeted mastery experiences and appropriate modelling.

Teachers can systematically build student self-efficacy through careful instructional design. Providing graduated difficulty ensures early successes that build confidence before increasing challenge. Using peer models effectively showcases that success comes through effort rather than innate ability. Offering specific, strategy-focused feedback helps students recognise their growing competence. Teaching students to set proximal, specific goals rather than distant, vague ones provides more frequent mastery experiences. Finally, helping students develop effective metacognitive strategies gives them tools they can reliably employ across different tasks, strengthening efficacy beliefs.

Central to Bandura's social learning theory is the concept of reciprocal determinism, which fundamentally distinguishes his approach from traditional behaviourist models. Rather than viewing behaviour as simply a response to environmental stimuli, Bandura proposed that behaviour, cognitive factors, and environmental influences operate as interlocking determinants that continuously influence each other bidirectionally. This three-way interaction means that whilst our environment shapes our behaviour, our behaviour simultaneously modifies our environment, and our thoughts and beliefs influence both processes.

In Bandura's model, personal factors (cognitive, affective, and biological), behaviour, and environmental influences all function as interacting determinants. Personal factors include beliefs, expectations, attitudes, and knowledge. Environmental factors encompass social influences, physical surroundings, and situational constraints. Behaviour refers to actions, choices, and verbal statements.

These three factors don't operate in a simple linear chain (environment → thoughts → behaviour) but in a complex network of bidirectional influences. A student's self-efficacy beliefs (personal factor) influence their study behaviour (behaviour), which affects their academic achievement and teacher responses (environment), which in turn further shapes their self-efficacy beliefs. The cycle continues in an ongoing process of reciprocal influence.

The relative influence of each factor varies across situations and individuals. In some circumstances, environmental factors dominate; a fire alarm immediately influences everyone's behaviour regardless of personal beliefs. In other situations, personal factors exert stronger influence; two students in identical environments may behave completely differently based on their beliefs and expectations. Understanding this active interplay enables more sophisticated interventions than simple behaviourist or purely cognitive approaches.

Reciprocal determinism explains why identical teaching methods produce vastly different outcomes across students. A student's prior knowledge and self-efficacy beliefs (cognitive factors) influence how they respond to classroom activities (behaviour), which affects teacher feedback and peer interactions (environment). For instance, a confident student may actively participate in discussions, leading to positive reinforcement that further enhances their self-belief and engagement, creating an upwards spiral of success.

Conversely, a student with low self-efficacy may remain passive during lessons, missing learning opportunities and receiving less teacher attention, which confirms their belief that they cannot succeed, creating a downwards spiral. The same classroom environment produces dramatically different experiences based on the reciprocal interactions between personal factors, behaviour, and environmental responses.

Understanding reciprocal determinism enables educators to intervene strategically across all three domains rather than focusing narrowly on one aspect. Teachers can modify environmental factors through thoughtful classroom organisation, strategic peer groupings, and structured learning activities. They can address cognitive factors by building students' self-efficacy, teaching effective learning strategies, and helping students develop positive attitudes towards learning. They can shape behaviour through targeted modelling, clear expectations, and consistent feedback.

Multifaceted interventions that address all three elements simultaneously prove most effective. For example, when working with a disengaged student, a teacher might change the environment by providing one-to-one support. They might address personal factors by highlighting past successes and building confidence. They can also shape behaviour through clear teaching of engagement strategies. This thorough approach recognises that sustainable change requires attention to the complex interplay between thinking, acting, and environmental context.

Bandura's social learning theory emerged as a bridge between traditional behaviourism and purely cognitive theories of learning, incorporating elements of both whilst addressing limitations of each approach. Understanding these relationships clarifies what makes social learning theory distinctive and valuable.

Classical behaviourist theories, exemplified by the work of B.F. Skinner and John Watson, proposed that all learning occurs through direct interaction with the environment via reinforcement and punishment. Behaviourists argued that internal mental states were irrelevant to understanding behaviour; observable stimulus-response connections were sufficient for explaining learning.

Bandura challenged this purely mechanistic view by demonstrating that learning can occur without direct reinforcement. The Bobo doll experiments showed conclusively that children learned aggressive behaviours simply through observation, without personally experiencing any rewards or punishments. This finding directly contradicted behaviourist predictions and necessitated incorporating cognitive processes into learning theory.

Social learning theory retains behaviourism's emphasis on environmental influences and the role of consequences in shaping behaviour. Bandura acknowledged that reinforcement and punishment matter; they simply aren't necessary for learning to occur, though they significantly influence whether learned behaviours are performed. This nuanced position allowed social learning theory to account for a wider range of learning phenomena than strict behaviourism whilst retaining insights about the power of consequences.

Behaviourism views learners as passive recipients of environmental conditioning. However, social learning theory shows them as active processors. They selectively focus on models, mentally encode observed behaviours, and make deliberate decisions about what to copy based on expected consequences. This active, cognitive dimension represents a fundamental departure from behaviourist assumptions.

Whilst social learning theory incorporates cognitive processes, it differs from purely cognitive approaches to learning in its emphasis on social and environmental factors. Cognitive theories often focus on internal mental processes, memory structures, and information processing whilst paying less attention to the social context in which learning occurs.

Social learning theory brings the social dimension into sharp focus, arguing that much human learning occurs through social interaction and observation of others. It emphasises that we don't learn in isolation; we are constantly influenced by models in our environment, and our cognitive processes operate in response to social stimuli and produce behaviours that influence our social world.

The concept of reciprocal determinism particularly distinguishes social learning theory from both behaviourism and purely cognitive approaches. Rather than viewing cognition and environment as separate domains, Bandura proposed their continuous interaction. This integrated perspective proves more thorough than theories that emphasise either environmental or cognitive factors whilst neglecting their interplay.

Bandura's social learning theory, developed in the 1960s and 1970s, remains remarkably relevant in contemporary educational contexts, particularly as digital technology creates new forms of observational learning opportunities and challenges.

The proliferation of social media platforms has exponentially increased children's exposure to potential role models, both positive and negative. Young people now observe and potentially imitate behaviours demonstrated by influencers, content creators, and peers through YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and similar platforms. This digital modelling operates through the same four processes Bandura identified: attention (capturing views through engaging content), retention (memorable, often repeated content), reproduction (copying dances, catchphrases, or attitudes), and motivation (pursuing likes, shares, and social status).

Teachers must recognise that classroom modelling now competes with constant exposure to online models, some of whom demonstrate values and behaviours inconsistent with educational goals. This reality necessitates explicit discussion of media literacy, critical evaluation of online role models, and deliberate cultivation of positive influences. Schools might incorporate analysis of social media influences into PSHE education, helping students develop awareness of how observational learning shapes their attitudes and behaviours online.

Online learning environments create new opportunities for peer modelling. Discussion forums, collaborative documents, and video conferencing enable students to observe peer problem-solving processes that might be invisible in traditional classrooms. Teachers can strategically use these tools to showcase effective learning strategies, sharing recorded examples of students working through challenging problems or collaborating productively.

However, virtual environments also reduce some observational learning opportunities. Students cannot casually observe classmates' study habits, note-taking strategies, or self-regulation techniques as readily in remote learning contexts. Teachers must deliberately create opportunities for these observations through screen sharing, think-aloud protocols during video lessons, and structured peer observation activities.

Digital technology enables sophisticated forms of modelling previously impossible in traditional classrooms. Teachers can record demonstrations that students review repeatedly, supporting both attention and retention processes. Slow-motion video allows detailed observation of complex procedures. Multiple camera angles provide perspectives unavailable in live demonstrations. Pause and replay functions give learners control over the observational learning pace.

Video libraries of worked examples enable students to observe expert problem-solving across numerous scenarios, accelerating the pattern recognition and strategy acquisition that would require extensive direct experience. This approach proves particularly valuable in mathematics and sciences, where observing multiple solution paths helps students develop flexible thinking.

Effective implementation of social learning theory requires deliberate attention to how teachers model desired behaviours and create opportunities for peer observation. The following strategies translate Bandura's principles into practical classroom applications.

Teachers should regularly verbalise their cognitive processes whilst demonstrating academic tasks. Rather than simply showing the final product, articulate the thinking behind each decision. "I'm reading this paragraph again because I wasn't sure about the author's main point" models metacognitive monitoring. "I'll start by identifying what the question is actually asking before I attempt to solve it" demonstrates strategic planning. This dual modelling of both behaviour and cognition provides students with observable access to usually invisible mental processes.

Systematically showcase student work and strategies to create peer models. Rather than only highlighting exceptional achievement, deliberately select examples from students whose abilities approximate those of the observing audience. When struggling students observe comparable peers succeeding through effort and strategy use, they develop stronger self-efficacy than when observing only high-achieving students. Ensure diverse students serve as models across different contexts, avoiding repeatedly featuring the same individuals.

Don't assume students automatically notice critical features of demonstrated behaviours. Explicitly direct attention: "Watch carefully how I organise my working to keep track of the steps" or "Notice that I reread the instructions before beginning." This explicit guidance helps students focus on relevant aspects rather than superficial or irrelevant features of the demonstration.

Demonstrate important procedures multiple times across varied contexts. Repetition strengthens retention, whilst variation helps students identify essential features that remain constant across situations. For instance, model problem-solving in mathematics across different problem types so students recognise underlying strategies that transfer across contexts.

After demonstrations, provide time for students to mentally rehearse observed behaviours before attempting physical reproduction. "Close your eyes and visualise yourself completing the experiment following the steps we just observed" supports retention and prepares students for successful reproduction. This brief mental practise significantly enhances subsequent performance.

Begin with simplified demonstrations that students can readily reproduce, gradually increasing complexity as confidence and competence develop. Early success experiences build self-efficacy that supports persistence when facing more challenging applications. Breaking complex procedures into teachable components allows students to master elements sequentially before combining them.

When showcasing success stories, emphasise the effort and strategies employed rather than innate ability. "Look how Maya persisted through three different approaches before finding one that worked" proves more instructionally valuable than "Maya is naturally good at this." The former attributes success to controllable factors students can emulate; the latter suggests success depends on fixed abilities students may believe they lack.

Deliberately demonstrate making mistakes and productively responding to errors. "Oops, that approach isn't working. Let me think about what went wrong and try a different strategy" models resilience and self-regulation. Students who only observe flawless performance may develop fragile self-efficacy that crumbles when they inevitably encounter difficulties.

Design activities specifically for peer observation and feedback. Partner students to observe each other practising skills, using observation checklists to focus attention on key features. This structured observation serves multiple purposes: observers strengthen retention through focused attention, whilst performers receive feedback and gain experience with being observed, reducing performance anxiety.

Record students successfully performing skills, then have them review their own successful performance. This technique proves particularly powerful for building self-efficacy, as students cannot dismiss their own capability when viewing evidence of their success. Video self-modelling has shown remarkable effectiveness with students who have disabilities or learning difficulties, providing them with concrete evidence of their abilities.

Regularly demonstrate how you monitor your own understanding, recognise confusion, and employ fix-up strategies. "I've read this three times and I'm still confused, so I'm going to try looking at the diagram to see if that helps" models metacognitive awareness and adaptive strategy use. These demonstrations help students develop the self-regulation skills essential for independent learning.

Create classroom routines where desired behaviours are regularly demonstrated and discussed. Morning meetings might showcase students demonstrating effective organisation strategies. Transition times can feature students modelling efficient materials management. These repeated observations, combined with recognition of the positive outcomes, create powerful vicarious reinforcement for the entire class.

The central premise of Bandura's social learning theory is that people learn new behaviours by observing and imitating others, without necessarily requiring direct personal experience of reinforcement or punishment. Unlike traditional behaviourist theories that emphasised learning through direct consequences, Bandura demonstrated that observational learning allows individuals to acquire complex behaviours simply by watching role models. The theory identifies four essential processes, attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation, that must occur for observational learning to be effective. Bandura's framework also emphasises the reciprocal interaction between personal cognitive factors, behaviour, and environmental influences, proposing that these elements constantly influence each other in a active process called reciprocal determinism.

The Bobo doll experiment provided empirical evidence that children learn aggressive behaviours through observation alone, without direct reinforcement. In the study, children who observed an adult behaving aggressively towards an inflatable doll subsequently imitated those specific aggressive actions when given the opportunity to play with the doll themselves. Critically, these children had received no rewards or punishments for their imitative behaviour; they simply reproduced what they had observed. This finding directly challenged behaviourist theories that insisted learning required direct experience of consequences. The experiment demonstrated all four processes of observational learning: children attended to the model's distinctive actions, retained memories of the behaviour, possessed the physical capability to reproduce it, and were motivated to imitate what they had seen. The study's profound implications extended to concerns about media violence and the importance of positive role models in child development.

Self-efficacy refers to an individual's belief in their capacity to successfully execute the behaviours required to achieve specific outcomes. In educational contexts, self-efficacy profoundly influences student achievement because it determines which challenges students undertake, how much effort they invest, how long they persist when facing difficulties, and how they respond to setbacks. Students with high self-efficacy approach challenging tasks with confidence, set ambitious goals, persist through obstacles, and attribute failures to insufficient effort or inadequate strategies, factors they can control and modify. Conversely, students with low self-efficacy avoid challenging tasks, give up quickly, and attribute failure to lack of ability, creating self-fulfilling prophecies of poor performance. Teachers can build student self-efficacy through four primary sources: providing appropriately challenging tasks that students can master through effort (mastery experiences), using peer models to demonstrate that success is achievable (vicarious experiences), offering credible encouragement and process-focused feedback (verbal persuasion), and creating supportive environments that reduce anxiety (managing physiological states).

Whilst social learning theory shares behaviourism's interest in how environmental factors shape behaviour, it differs in several fundamental ways. Behaviourism proposes that learning occurs only through direct experience of reinforcement and punishment; social learning theory demonstrates that learning can occur through observation without direct personal consequences. Behaviourism treats learners as passive recipients of environmental conditioning; social learning theory portrays learners as active processors who selectively attend to models, cognitively encode information, and deliberately decide what to imitate based on anticipated outcomes. Behaviourism dismisses internal mental states as irrelevant to explaining behaviour; social learning theory emphasises cognitive mediational processes that occur between observing a behaviour and deciding whether to reproduce it. Bandura's concept of reciprocal determinism represents a fundamental departure from behaviourism's unidirectional environmental determinism, proposing instead that behaviour, cognition, and environment continuously influence each other in a complex, bidirectional manner. This integrated perspective allows social learning theory to explain a wider range of learning phenomena whilst retaining insights about the role of consequences in shaping behaviour.

The four processes of observational learning are attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation. Attention involves noticing and focusing on the model's behaviour; without attending to relevant features, learning cannot occur. Factors affecting attention include the distinctiveness of the behaviour, characteristics of the model, functional value of the behaviour, and environmental conditions. Retention requires encoding the observed behaviour into memory through imaginal and verbal coding systems. Teachers improve retention through repetition, mental rehearsal, verbal labelling during demonstrations, and connecting new observations to existing knowledge. Reproduction involves translating mental representations into actual performance, which depends on the learner possessing necessary physical and cognitive capabilities. Feedback, practise, and graduated complexity support the reproduction process. Motivation determines whether learned behaviours are actually performed and involves anticipated consequences based on direct reinforcement, vicarious reinforcement from observing others' outcomes, and self-reinforcement from meeting personal standards. All four processes must function effectively for observational learning to produce behaviour change.

Teachers can apply social learning theory through numerous practical strategies. Think-aloud modelling involves verbalising cognitive processes whilst demonstrating tasks, making invisible thinking observable to students. Strategic peer modelling showcases students of varied ability levels, allowing observers to see comparable peers succeed through effort rather than only observing exceptional talent. Teachers should explicitly direct attention to critical features of demonstrations rather than assuming students automatically notice important aspects. Repetition with variation strengthens retention whilst helping students identify transferable strategies. Providing time for mental rehearsal after demonstrations supports memory consolidation before physical practise. Teachers should highlight effort and strategy in successful models rather than attributing success to innate ability, and deliberately model error correction and resilience to demonstrate productive responses to difficulties. Creating structured peer observation activities provides focused learning opportunities, whilst video self-modelling allows students to observe their own successes, building self-efficacy. Throughout all instruction, teachers should model self-regulation and metacognition, demonstrating how expert learners monitor understanding and employ adaptive strategies. Finally, establishing positive behaviour modelling routines creates regular opportunities for observational learning of desired classroom behaviours.

Vicarious reinforcement occurs when learners modify their behaviour based on observing the consequences experienced by others rather than through direct personal experience of rewards or punishments. When students observe a peer receiving praise for a particular behaviour, they vicariously experience that positive reinforcement and become more likely to exhibit the same behaviour themselves, anticipating similar positive outcomes. This process operates through cognitive evaluation; students actively assess the relationship between observed behaviours and their consequences, forming expectations about likely outcomes if they were to perform similar actions. Vicarious reinforcement proves particularly powerful in classroom management, as teachers can influence entire groups by ensuring that positive consequences for appropriate behaviour are publicly visible. Rather than quietly acknowledging good work, effective teachers publicly recognise effort and achievement, allowing all students to witness the connection between positive behaviour and rewarding outcomes. Similarly, vicarious punishment occurs when students observe others experiencing negative consequences, which decreases their likelihood of imitating the behaviour. Understanding vicarious reinforcement enables educators to create classroom cultures where desired behaviours spread through observation and anticipated consequences rather than requiring each student to be individually reinforced.

Social learning theory remains highly relevant for understanding learning in digital and online environments, though these contexts create both enhanced opportunities and new challenges for observational learning. Online platforms exponentially increase exposure to potential role models through social media influencers, content creators, and peer-generated content. Young people observe and copy behaviours shown on YouTube, TikTok, and similar platforms. This happens through Bandura's four processes: engaging content captures attention, memorable material supports retention, demonstrated behaviours can be copied, and motivation comes from wanting social status and approval. In educational contexts, digital technology enables sophisticated modelling through recorded demonstrations students can review repeatedly, supporting both attention and retention. Video allows multiple perspectives, slow-motion analysis of complex procedures, and pause-replay functionality that gives learners control over the observation pace. However, virtual environments can reduce casual observational learning of study habits and self-regulation strategies visible in physical classrooms. Understanding social learning theory helps educators work through digital learning by strategically designing opportunities for positive modelling whilst recognising how online environments influence the observational learning processes.

Bandura's Social Learning Theory offers profound insights into how individuals acquire new behaviours and the critical role of observational learning. By moving beyond traditional behaviourist models, Bandura highlighted the importance of cognitive processes, social interactions, and the influence of role models. The four key processes, attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation, provide a framework for understanding how learning occurs through observation, imitation, and modelling.

For educators, Bandura's theory offers practical strategies for enhancing teaching and learning. By serving as positive role models, providing clear demonstrations, and developing a supportive learning environment, teachers can help observational learning in the classroom. Understanding the impact of social influences and the importance of self-efficacy helps educators to create engaging and effective educational journeys that promote student success. Bandura's legacy continues to shape educational practices, reminding us of the power of social learning in shaping behaviour and developing lifelong growth.

In today's digital age, Bandura's insights have gained renewed significance as educators work through the challenges of online learning and social media influence. Teachers must now consider not only their direct modelling within physical classrooms but also how their digital presence and virtual interactions serve as learning models for students. The principles of observational learning apply equally to video conferences, recorded lessons, and online collaborative spaces, where students continue to absorb social cues and behavioural patterns from their educators and peers.

Practical application of social learning theory requires educators to strategically design opportunities for positive peer modelling and collaborative learning. This might involve pairing struggling students with successful role models, creating demonstration opportunities for students to showcase appropriate academic behaviours, or establishing classroom cultures where positive social interactions are consistently modelled and reinforced. By understanding that learning is fundamentally a social process, teachers can use the natural tendency for observational learning to create more engaging and effective educational experiences that extend well beyond traditional instruction methods.

The enduring relevance of social learning theory across more than six decades demonstrates the fundamental truth Bandura identified: humans are profoundly social creatures who learn continuously from observing others. Whether in traditional classrooms, digital learning environments, or everyday social interactions, the principles of attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation continue to shape how we acquire new knowledge, skills, and behaviours. For teachers committed to maximising student learning, understanding and strategically applying these principles represents one of the most powerful pedagogical tools available.

The Bobo Doll experiment revealed striking patterns in how children learn aggressive behaviours through observation. Children who watched adults behaving aggressively towards the inflatable doll were significantly more likely to reproduce these violent actions, often mimicking the exact phrases and movements they had witnessed. Most notably, children didn't just copy physical aggression; they also imitated the verbal hostility and even invented new aggressive acts beyond what they had observed.

Bandura's research uncovered several crucial findings that transform how we understand classroom behaviour. First, children were more likely to imitate same-sex models, suggesting that pupils pay closer attention to role models they perceive as similar to themselves. Second, the study showed that consequences matter: when children saw the adult model being rewarded for aggression, imitation rates increased dramatically. Conversely, when the model was punished, fewer children copied the behaviour.

These findings carry profound implications for teaching practise. Teachers should be acutely aware that pupils constantly observe and potentially imitate their reactions to frustration or conflict. For instance, a teacher who responds calmly to disruption models emotional regulation, whilst one who shouts inadvertently teaches that volume equals authority. Additionally, peer behaviour significantly influences classroom dynamics; when popular students display positive behaviours like helping others or participating enthusiastically, their classmates often follow suit.

The research also highlighted that learning occurred even when children didn't immediately display the behaviour, a phenomenon Bandura termed 'latent learning'. This suggests that pupils absorb far more from their environment than they initially demonstrate, making the classroom atmosphere and teacher modelling even more critical for long-term behavioural development.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

How Students' Motivation and Learning Experience Affect Their Service-Learning Outcomes: A Structural Equation Modelling Analysis View study ↗

63 citations

K. Lo et al. (2022)

This study of over 2,000 college students reveals that student motivation and positive learning experiences are the strongest predictors of academic success in service-learning programmes. The research provides concrete evidence that when teachers focus on creating engaging experiences and building student motivation, they directly improve learning outcomes. For educators implementing community service components in their curriculum, this study confirms that the quality of the learning experience matters just as much as the service activity itself.

Factors affecting students' learning performance through collaborative learning and engagement View study ↗

470 citations

M. A. Qureshi et al. (2021)

This research demonstrates that social factors play a crucial role in making collaborative learning effective, directly impacting student performance and engagement levels. The study provides valuable insights for teachers looking to move beyond traditional lecture formats towards more interactive, group-based learning approaches. Understanding how social dynamics influence collaboration can help educators design more effective group activities and create classroom environments where students learn better together.

Modelling Chinese Secondary School Students' Behavioural Intentions to Learn Artificial Intelligence with the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Self-Determination Theory View study ↗

58 citations

C. Chai et al. (2022)

This study explores what motivates secondary students to want to learn about artificial intelligence, finding that student attitudes, perceived control, and personal autonomy significantly influence their willingness to engage with AI topics. For teachers introducing technology and AI concepts into their curriculum, this research offers insights into how to present these subjects in ways that genuinely interest students. The findings suggest that giving students choice and helping them see the relevance of AI to their lives increases their motivation to learn these increasingly important skills.

IMITATION AND GAME STEM TECHNOLOGIES AND PRACTICES IN LESSONS OF NATURAL AND MATHEMATICAL CYCLE View study ↗

Malchykova D.S. et al. (2021)

This research examines how game-based and imitation technologies can transform traditional math and science lessons into more engaging, interactive experiences. The study emphasizes that successful STEM education requires moving beyond conventional teaching methods to include hands-on, innovative approaches that develop critical thinking skills. For math and science teachers, this work provides practical evidence that incorporating game elements and simulation activities can make abstract concepts more accessible and motivating for students.

Myth of English teaching and learning: a study of practices in the low-cost schools in Pakistan View study ↗

46 citations

Syed Abdul Manan (2018)

This study reveals significant challenges in English language instruction at low-cost schools in Pakistan, showing gaps between policy intentions and actual classroom practise. The research highlights how resource constraints and teaching methods can impact the effectiveness of English language programmes, offering lessons for educators working in under-resourced environments. For teachers facing similar challenges, this study provides realistic insights into adapting language instruction when ideal conditions and materials are not available.

Albert Bandura's Social Learning Theory revolutionised our understanding of how people learn by demonstrating that we acquire new behaviours simply by watching others, rather than needing direct rewards or punishments. This groundbreaking concept was famously proven through Bandura's iconic Bobo Doll experiment in the 1960s, where children who observed adults attacking an inflatable doll later mimicked the same aggressive behaviours. The theory centres on four key cognitive processes: paying attention to the behaviour, remembering what was observed, having the ability to reproduce it, and being motivated to imitate it. But what made those children in the laboratory so quick to copy violence, and what does this reveal about how we all learn throughout our lives?

Albert Bandura (1925-2021) transformed our understanding of how people learn by proposing that individuals acquire new behaviours through observing and imitating the actions of others. Unlike earlier behaviourist models, which emphasised direct reinforcement, Bandura introduced the idea that learning can occur through social interaction and observation alone. His theory provided an alternative to the work of earlier education theorists, who focused on direct reinforcement, and expanded on existing theories of learning by incorporating cognitive and environmental influences. In 2025, Bandura's framework remains one of the most widely applied theories in teacher training and classroom practise.

According to Bandura, learning isn't solely the result of conditioning but involves a active interplay between cognition, environment, and behaviour. He identified two key processes that differentiate social learning from traditional behaviourist theories:

| Stage/Level | Age Range | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention | All ages | Noticing and focusing on the modelled behaviour, selective observation of relevant features | Teachers should ensure behaviours are distinctive, use clear demonstrations, minimise distractions |

| Retention | All ages | Remembering and storing the observed behaviour through mental images or verbal descriptions | Use repetition, provide opportunities for mental rehearsal, connect to prior knowledge |

| Reproduction | All ages | Physical and cognitive ability to perform the observed behaviour, converting memory into action | Break complex behaviours into steps, provide guided practise, ensure developmental readiness |

| Motivation | All ages | Having reasons to imitate the behaviour, influenced by reinforcement and consequences observed | Highlight positive outcomes, use peer models, create meaningful rewards for learning |

Born in 1925 in Canada, Bandura earned his PhD at the University of Iowa in 1952 and later became one of the most influential psychologists of the 20th century. His 1977 book, Social Learning Theory, formalised his ideas and demonstrated how children and adults learn from modelled behaviours. One of his most well-known experiments, the Bobo doll study, showed how children imitate aggression after witnessing it in adults, reinforcing his argument that learning is largely influenced by social exposure.

Beyond education, Bandura's theory has been applied in parenting, workplace training, media studies, and behavioural therapy. His work also led to the development of self-efficacy, the belief in one's ability to succeed. Bandura argued that higher self-efficacy leads to greater achievement, shaping how individuals approach learning, challe nges, and personal growth.

The Bobo doll experiment, conducted in 1961 at Stanford University, stands as one of the most influential studies in the history of psychology. Albert Bandura designed this groundbreaking research to test a fundamental question: Can children learn aggressive behaviours simply by observing adults, without any direct reinforcement? The study challenged the dominant behaviourist theories of the time, which insisted that learning required direct experience of rewards or punishments.

Bandura's experimental design was methodical and carefully controlled. He recruited 72 children (36 boys and 36 girls) aged between 3 and 6 years from the Stanford University Nursery School. The children were divided into three main experimental groups, with equal numbers of boys and girls in each condition to control for potential gender differences in aggressive behaviour.

The first group observed an adult model behaving aggressively towards a five-foot inflatable Bobo doll. The adult model entered a playroom and, after a brief period of play with other toys, began a sustained physical and verbal assault on the Bobo doll. The aggressive behaviours were highly distinctive and included punching the doll, hitting it with a mallet, throwing it in the air, and kicking it around the room. Crucially, the adult also used specific verbal aggression, shouting phrases such as "Sock him in the nose!" and "Pow!" These distinctive verbal and physical behaviours made it easy to identify clear copying when children were later observed.

The second group observed a non-aggressive adult model who completely ignored the Bobo doll and played quietly with other toys in the room for the same duration. This condition served as a control to demonstrate that mere exposure to the doll and playroom environment didn't automatically trigger aggression.

The third group was a control group that had no exposure to any adult model. These children simply played in the room without witnessing any modelled behaviour, providing a baseline measure of children's natural aggression levels towards the Bobo doll.

An additional experimental condition examined the effect of model gender. Some children observed same-sex models whilst others observed opposite-sex models, allowing Bandura to investigate whether children were more likely to imitate models of their owngender, a hypothesis supported by social learning theory.

After exposure to the model, each child was individually taken to a different room filled with attractive toys. To create mild frustration and increase the likelihood of aggressive responses, the experimenter told the children after two minutes that these toys were reserved for other children. The children were then taken to a third room containing both aggressive toys (such as mallets and dart guns) and non-aggressive toys, along with the Bobo doll. Observers behind a one-way mirror recorded the children's behaviour for 20 minutes.

The results were striking and unambiguous. Children who had observed the aggressive model reproduced a significant amount of the physically and verbally aggressive behaviour they had witnessed. They didn't simply show more general aggression; they performed precise imitations of the specific actions and words used by the adult model. Children who had observed the aggressive model were statistically far more aggressive than those in either the non-aggressive or control conditions.

Bandura found that boys were significantly more aggressive than girls overall, but girls who had observed aggressive female models showed aggression levels comparable to boys. This suggested that whilst biological factors might predispose boys to higher baseline aggression, observational learning could powerfully override these tendencies. The study also revealed that children were more likely to imitate same-sex models, particularly for physical aggression, supporting the role of identification in observational learning.

Perhaps most concerning from an applied perspective, children often exhibited novel aggressive behaviours that went beyond mere imitation. They improvised new ways to attack the doll, demonstrating that observational learning didn't just produce rote copying but could inspire creative variations on observed themes.

The Bobo doll experiment had profound implications that extended far beyond the psychology laboratory. It provided compelling evidence that children are highly susceptible to social influences and can acquire complex behaviours through observation alone, without needing direct reinforcement. This finding transformed understanding of child development and had immediate practical applications.

For educators, the study underscored the critical importance of teacher modelling. Children in classrooms don't just learn academic content; they constantly observe and absorb behavioural patterns demonstrated by adults and peers. Teachers who model respectful communication, problem-solving strategies, and emotional regulation effectively teach these behaviours to their students through observational learning. Conversely, displays of frustration, sarcasm, or dismissive behaviour can be equally readily acquired.

The experiment also raised significant concerns about media violence and its impact on children. Children could learn and copy aggressive behaviours after just a few minutes of observation in a laboratory setting. What might be the combined effect of hours of exposure to violence in television programmes, films, and video games? This question sparked decades of subsequent research and continues to inform debates about media regulation and parental guidance.

From a classroom management perspective, the Bobo doll study highlighted the need for consistent modelling of positive behaviours. Children learn not just from what teachers explicitly teach but from everything they observe, including how teachers handle stress, resolve conflicts, and interact with different students. The study suggested that creating a positive classroom culture requires deliberate attention to the behaviours being modelled throughout the school day.

Bandura identified four essential processes that determine whether observational learning occurs effectively: attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation. These sequential stages must all function successfully for learners to acquire new behaviours through modelling. Understanding each process in depth enables educators to design learning experiences that maximise the power of observational learning.

The attention process represents the first critical stage of observational learning. Learners cannot acquire behaviours they haven't noticed, making attention the gateway through which all observational learning must pass. However, attention isn't a simple on-off switch; it involves selective focus on relevant aspects of the model's behaviour whilst filtering out irrelevant details.

Several factors influence whether learners attend to a model's behaviour. The distinctiveness of the behaviour plays a important role; unusual, vivid, or clearly demonstrated actions capture attention more effectively than subtle or commonplace behaviours. This explains why teachers often exaggerate certain aspects of demonstrations, using dramatic gestures or emphatic language to ensure students notice critical features.

The characteristics of the model also significantly affect attention. Learners pay more attention to models they perceive as competent, attractive, powerful, or similar to themselves. In classroom settings, this means peer models can be particularly effective, especially when students perceive the demonstrating peer as comparable in ability rather than exceptionally talented. A struggling student who successfully masters a technique may provide a more compelling model than the highest-achieving student in the class.

Functional value influences attention as well. Learners are more likely to attend carefully to behaviours they believe will be useful or valuable to them. Teachers can improve attention by explicitly explaining why a particular strategy or skill matters, connecting it to students' goals or interests. When students understand that a demonstrated study technique will help them remember content more effectively, they attend more carefully to the demonstration.

Environmental factors also matter enormously. Distractions, competing stimuli, and poor visibility all undermine attention. Effective modelling requires minimising distractions, ensuring clear sight lines, and creating an environment where the demonstrated behaviour stands out clearly from the background. This is why many teachers instinctively call for silence and direct visual attention before beginning demonstrations.

Attention alone cannot produce learning; observed behaviours must be encoded into memory in a form that permits later retrieval and reproduction. The retention process involves transforming observed actions into mental representations that can be stored and accessed when needed. Bandura identified two primary coding systems through which retention occurs: imaginal and verbal.

Imaginal coding involves creating vivid mental images of the observed behaviour. When a student watches a teacher demonstrate how to conduct a science experiment, they form visual memories of each step, the equipment arrangement, and the movements involved. These mental images serve as internal models that can be mentally rehearsed and later retrieved during actual performance.

Verbal coding involves describing the observed behaviour in words, creating a linguistic representation that can be more easily stored and recalled than pure imagery. A student might internally narrate "First, measure 50ml of water, then add three drops of indicator, swirl gently, and observe the colour change." This verbal encoding complements visual representation and often lasts longer in long-term memory.

Teachers can significantly improve retention through several strategies. Repetition of demonstrations allows multiple encoding opportunities, strengthening memory traces. Encouraging mental rehearsal, where students mentally walk through the observed behaviour whilst seated, reinforces retention without requiring physical practise. Connecting new observations to existing knowledge schemas creates retrieval paths that make memories more accessible.

The use of verbal labelling during demonstrations proves particularly powerful. When teachers simultaneously demonstrate and describe their actions, they provide both imaginal and verbal coding opportunities, supporting dual encoding. Research on Allan Paivio's dual coding theory confirms that information encoded in multiple formats is remembered more effectively than single-format encoding.

Time delays between observation and performance opportunity affect retention significantly. Without rehearsal, memory traces decay rapidly. Teachers should provide opportunities for relatively prompt practise after demonstrations, whilst the memory remains fresh and accessible. Alternatively, structured review sessions help students reactivate and consolidate memories before they fade completely.

Even with perfect attention and retention, learning remains incomplete until the learner can physically or cognitively reproduce the observed behaviour. The reproduction process requires translating mental representations into actual performance, a stage that depends heavily on the learner's existing capabilities and developmental readiness.

Physical capabilities constrain what behaviours can be reproduced. A young child who observes an adult performing a complex motor skill may attend perfectly and retain a clear memory yet lack the physical coordination, strength, or fine motorcontrol to execute the action. Teachers must ensure that demonstrated behaviours match students' developmental capabilities or provide scaffolded approaches that break complex actions into achievable components.

Cognitive capabilities similarly affect reproduction. Understanding the principles underlying a demonstrated problem-solving strategy requires sufficient cognitive development and background knowledge. A student who observes a teacher using algebraic manipulation may lack the conceptual understanding to reproduce the steps meaningfully, even with perfect memory of the procedure.

Feedback during initial reproduction attempts proves important. Learners rarely execute observed behaviours perfectly on the first attempt; they need corrective information to align their performance with the observed model. This feedback can come from teachers, peers, or self-monitoring against remembered images of the model's performance. The quality and timing of feedback significantly influence how quickly learners achieve accurate reproduction.

Practise plays an essential role in moving from approximate to precise reproduction. Initial attempts typically capture the general form of the behaviour, but refinement requires repeated practise with attention to details. Teachers help this process by breaking complex behaviours into manageable components, allowing students to master each element before combining them into the complete performance.

Self-efficacy beliefs powerfully influence reproduction attempts. Students who doubt their capability to perform an observed behaviour may not attempt reproduction at all, despite perfect attention and retention. Building confidence through graduated difficulty, ensuring early successes, and highlighting progress all support students' willingness to attempt reproduction of observed behaviours.

The motivation process represents the final stage of observational learning and addresses a important distinction Bandura made between acquisition and performance. Students may successfully attend to, retain, and possess the capability to reproduce an observed behaviour yet choose not to perform it. Motivation determines whether learned behaviours are actually enacted.

Bandura identified three types of reinforcement that influence motivation: direct reinforcement, vicarious reinforcement, and self-reinforcement. Direct reinforcement occurs when learners personally experience positive consequences for performing the behaviour. A student who receives praise after using a problem-solving strategy observed from a teacher becomes more motivated to use that strategy again.

Vicarious reinforcement operates through observation of consequences experienced by others. When students observe peers being praised, rewarded, or successful after performing particular behaviours, they become more motivated to attempt those behaviours themselves. This process proves particularly powerful in classroom settings where teachers can strategically highlight and reward desired behaviours, allowing the entire class to vicariously experience the positive consequences.