Emotion Regulation

Explore emotion regulation's role in children's learning. Discover practical strategies teachers can use to foster emotional wellbeing and academic success.

Explore emotion regulation's role in children's learning. Discover practical strategies teachers can use to foster emotional wellbeing and academic success.

A revolution in has occurred in the past two decades, transforming how we view the connections between learning, emotions, and the brain. A growing body of evidence suggests that emotions and learning are inevitably linked.

We all know that 'we feel, therefore we learn'. Emotional learningis a key aspect of teaching children, so in this blog post, we will be exploring different strategies in which to support it within the school context.

Teachers often disregard a child's emotions in favour of expecting him or her to give their best effort to the task at hand because they believe that emotion is separate from cognition. We've also heard the distinction before, differentiated as matters of the heart and matters of the mind, but there is no truth to this at all and it is a complete misconception for emotion and cognition to be considered as two separate entities. Rather, both emotion and cognition are interlinked and equally contribute to the control of thought and behaviour.

Emotional regulation is the process of managing and controlling emotions in order to create an optimal learning environment. It involves recognising and understanding feelings, constructively expressing them, moderating emotional responses through strategies such as self-regulation or calming activities, and using appropriate problem-solving methods.

The goal of emotional regulation is to help individuals manage their emotions so that they are better able to think logically and engage productively in learning tasks without disruption.

Emotions and cognition are deeply interconnected, not separate systems as traditionally believed. When students experience strong emotions, these feelings directly impact their ability to process information, concentrate, and retain new knowledge. Research shows that emotional states can either enhance or block cognitive functions, making emotional awareness crucial for effective learning.

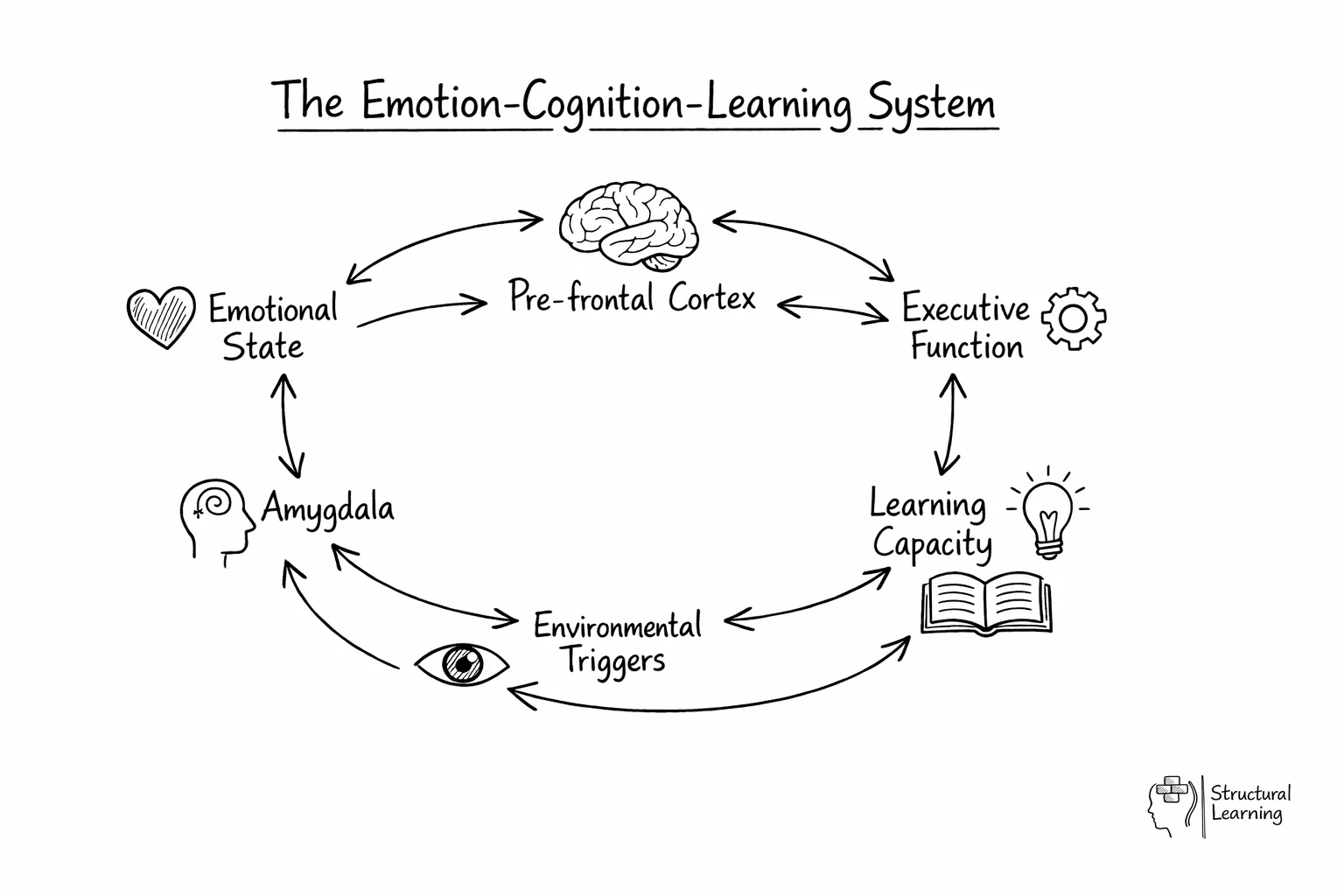

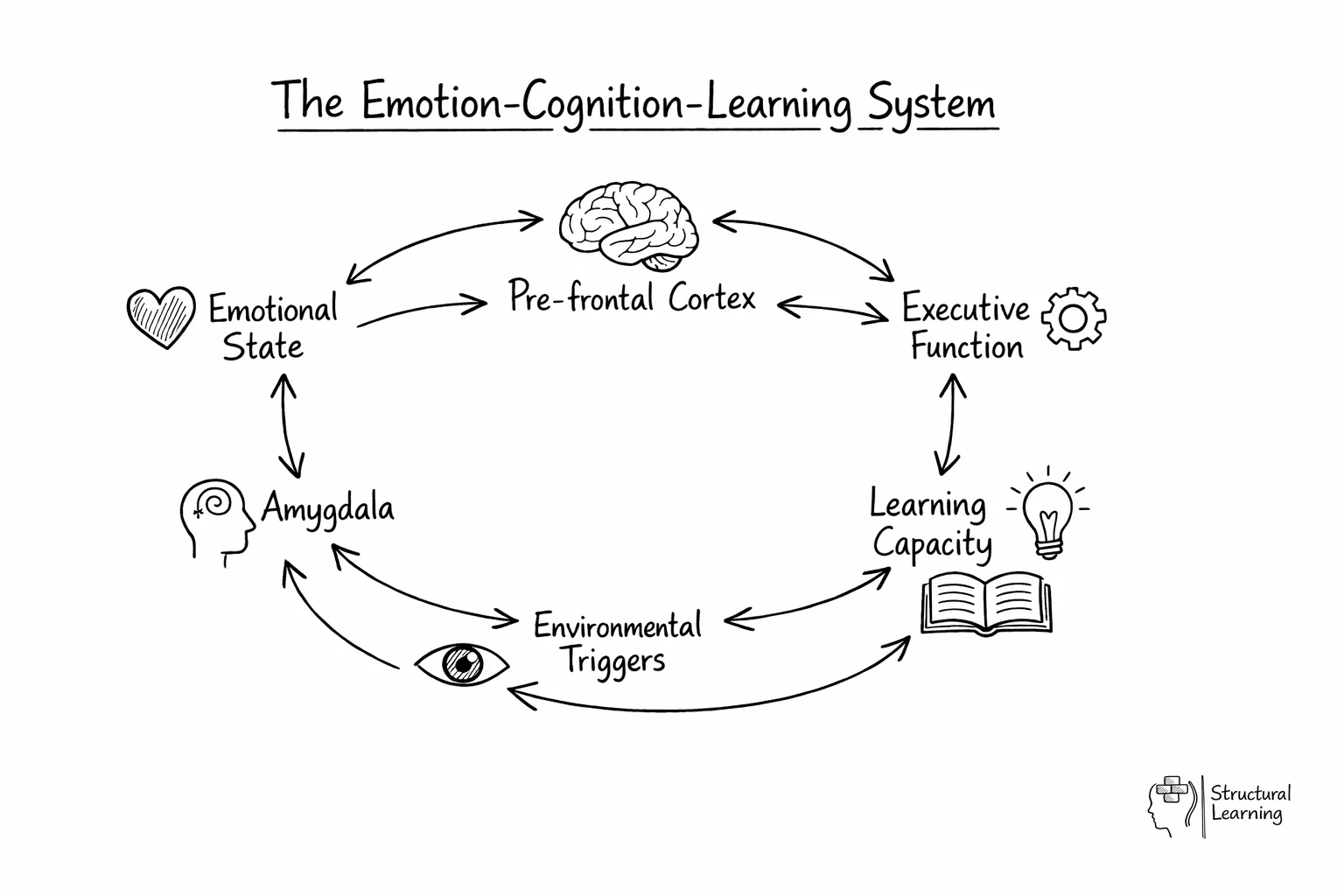

A key area in the field of neuroscience is the interaction between emotion and cognition and it is this interaction which is essential for the adaptation of individuals to the environment. Emotion and cognition work together to activate particular brain areas, systems, and behaviours that seek adaptable responses to the event.

feedback loops" loading="lazy">

feedback loops" loading="lazy">This interaction plays a significant role in the attentional deployment as well as the processes and regulation of emotion and cognition, which are integrated very early in development and have a great impact on later development too. In fact, emotions serve as an influential medium for increasing or impeding learning, therefore, they are critical in students' academic development.

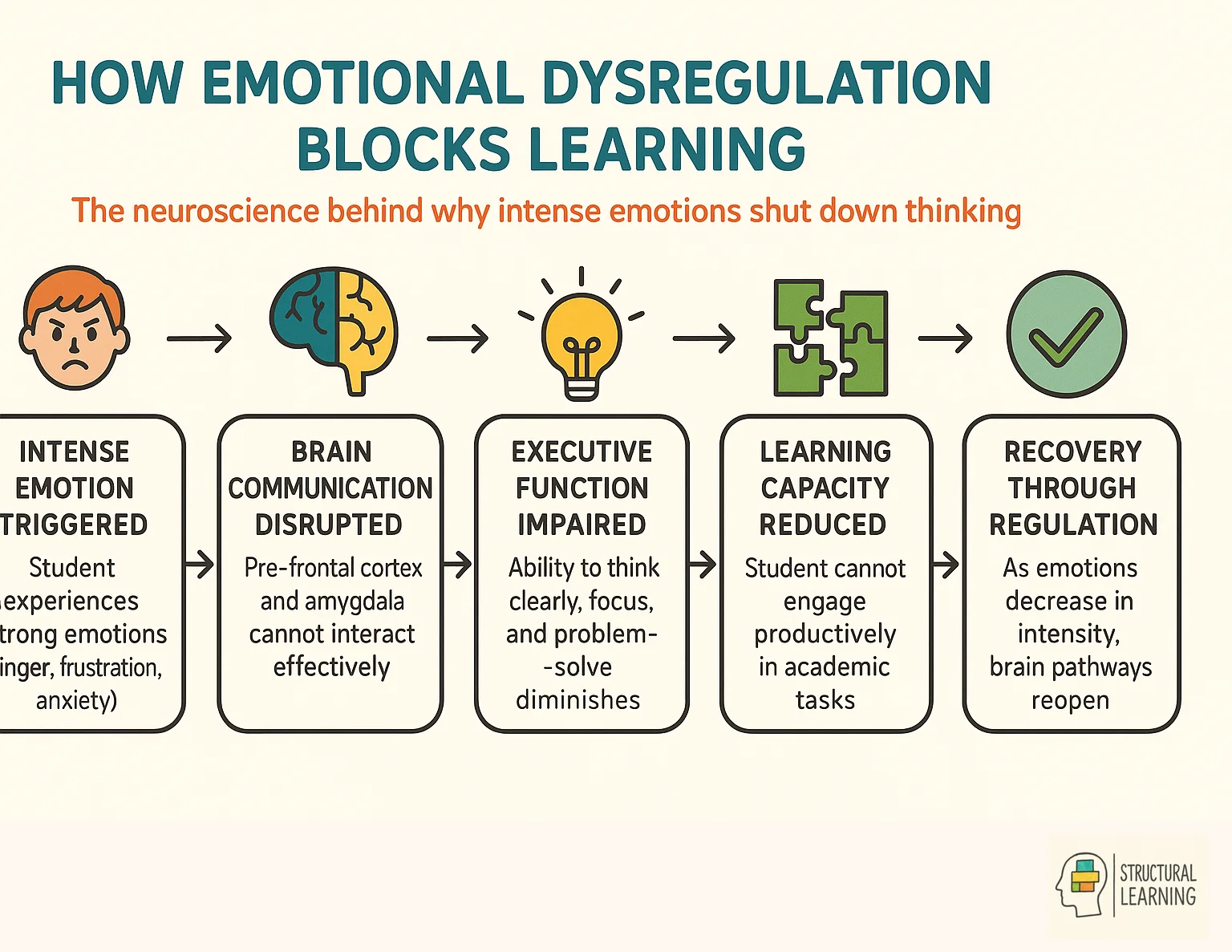

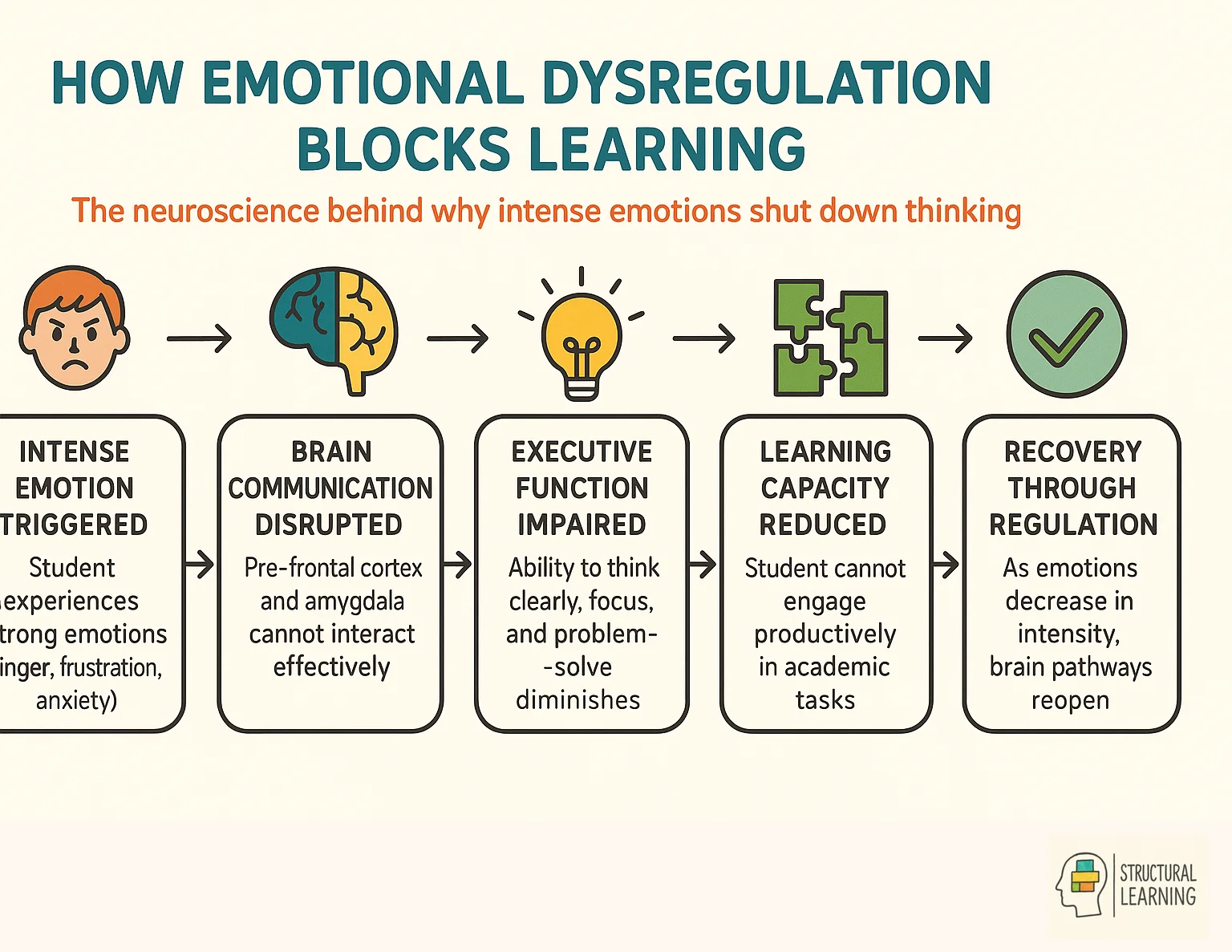

When our emotions are so intense that we become dysregulated, our executive function (the management system of our brain) does not work at full capacity. Our ability to think clearly and put the executive function into action is directly related to what we feel and how intensely we feel it.

The two key brain areas for emotion regulation, the pre-frontal cortex, and the amygdala, would be unable to interact with one another in a dysregulated state, leaving our emotions in charge (emotional dysregulation).

As the emotions decrease in their intensity, they become easier to manage. When emotions are well-managed, the pathways in the brain re-open, freeing up space for the executive function to mobilise. Therefore, emotion and cognition are working in tandem in order to function well.

Children with poor emotion regulation experience increased conflicts with teachers, struggle academically, and have difficulty forming positive peer relationships. These early regulation challenges often predict long-term academic difficulties and behavioural problems throughout their school years. Without intervention, dysregulated emotions can shut down a child's ability to think clearly and engage in classroom activities.

Research (Rudasill & RimmKaufman, 2009) shows that in educational settings, preschool children with low emotion regulation skills have more conflict with their teachers. Poor emotion regulation has a detrimental effect on academic performance and social emotional learning. It can also result in internalising and externalising disorders, which add to societal issues.

Therefore, integrating knowledge about cognitive emotion regulation strategies within the education system is crucial to enable a decrease in educational problems, such as absenteeism, poor school performance, early school leavers, poor interpersonal skills, and deficits in higher-order cognitive processes.

Teachers should also watch for academic performance indicators that may signal emotional regulation difficulties. Children experiencing emotional challenges often show decreased concentration spans, increased errors in familiar tasks, or reluctance to participate in activities they previously enjoyed. These academic red flags frequently appear before more obvious behavioural disruptions, making them valuable early intervention opportunities.

The classroom-wide impact becomes particularly evident during transitions, group activities, and high-pressure situations such as assessments. When children cannot regulate their emotions effectively, these moments can trigger widespread dysregulation throughout the class. Teachers may notice increased noise levels, difficulty maintaining focus during lessons, or peer conflicts becoming more frequent and intense. Understanding these patterns helps educators anticipate challenging periods and prepare appropriate support strategies.

Effective classroom management for emotional regulation involves creating predictable routines, establishing clear emotional vocabulary, and implementing consistent calming strategies. Simple techniques such as designated quiet spaces, visual emotion charts, and regular check-ins can significantly reduce the likelihood of emotional escalation affecting the broader classroom environment whilst supporting individual children's developmental needs.

Teachers can significantly enhance children's emotion regulation through structured modelling and explicit instruction. Research by Marc Brackett demonstrates that when educators consistently name and discuss emotions in real-time classroom situations, children develop stronger emotional vocabulary and self-awareness. Begin by narrating your own emotional responses: "I notice I'm feeling frustrated because the projector isn't working, so I'm going to take three deep breaths before we continue." This transparent approach helps children understand that all emotions are normal and manageable.

Creating predictable classroom routines supports emotional regulation by reducing cognitive load, as Daniel Siegel's research on the developing brain shows. Implement transition signals, visual schedules, and consistent response patterns to help children anticipate changes and prepare emotionally. When disruptions occur, guide children through problem-solving steps rather than simply correcting behaviour: "What are you feeling right now? What might help you feel calmer?"

Establish a dedicated calm-down space equipped with sensory tools like stress balls, breathing prompt cards, or noise-reducing headphones. Teach specific techniques such as the "balloon breathing" method or progressive muscle relaxation during neutral moments, so children can access these strategies when emotions run high. Remember that emotion regulation develops gradually; consistent practice and patience yield the strongest educational impact.

Emotion regulation develops predictably across childhood, with distinct milestones that directly impact classroom behaviour and learning. In early years (ages 3-6), children rely heavily on external support from adults to manage their emotions, as their prefrontal cortex is still developing. Ross Thompson's research demonstrates that young children need co-regulation from teachers, who serve as emotional scaffolds through calming presence, predictable routines, and explicit emotional vocabulary instruction.

Middle childhood (ages 7-11) marks a crucial transition period where children begin developing internal regulation strategies. During this phase, children can start learning cognitive techniques like counting to ten or identifying physical signs of emotional arousal. However, they still benefit enormously from structured practice and clear expectations. Consistent classroom frameworks become essential, as children at this age are building their emotional toolkit but cannot yet reliably access these skills under stress.

Adolescents (ages 12-18) possess more sophisticated cognitive abilities but face unique neurological challenges, as the emotional centres of their brains develop faster than areas responsible for impulse control. Practical classroom strategies should focus on teaching metacognitive awareness, helping students recognise their emotional patterns and develop personalise d regulation strategies. Creating opportunities for reflection and peer support proves particularly effective during this developmental stage.

The physical and emotional atmosphere of a classroom profoundly influences children's capacity for emotion regulation and subsequent learning outcomes. Research by Patricia Jennings demonstrates that emotionally supportive environments reduce cortisol levels in students, creating optimal conditions for cognitive processing and emotional development. When teachers establish predictable routines, clear expectations, and warm interpersonal relationships, children develop the psychological safety necessary to practice and refine their emotion regulation skills throughout the school day.

Creating such environments requires deliberate attention to both structural and relational elements. Consistent daily routines provide the predictability that helps anxious or dysregulated children feel secure, while designated quiet spaces offer opportunities for emotional reset when needed. Equally important is the teacher's own emotional presence; when educators model calm responses to classroom challenges and acknowledge children's feelings without judgement, they demonstrate effective emotion regulation strategies in real-time.

Practical implementation begins with simple environmental modifications: establishing clear visual cues for different activities, maintaining organised learning spaces that reduce sensory overwhelm, and incorporating regular check-ins that normalise emotional awareness. Teachers who proactively teach emotion vocabulary and provide scaffolded opportunities for children to express their feelings create classrooms where emotion regulation becomes an integral part of the learning process rather than a barrier to it.

Some children require additional support beyond universal classroom strategies to develop effective emotion regulation skills. These students may display persistent emotional outbursts, withdrawal behaviours, or difficulty recovering from distressing situations. Research by Bruce Perry demonstrates that children who have experienced trauma or chronic stress often have heightened stress response systems, making emotional self-regulation particularly challenging in busy classroom environments.

Creating individualised support plans becomes essential for these learners. Start by identifying specific triggers and early warning signs, then collaborate with the child to develop personalised coping strategies they can access independently. Consider environmental modifications such as providing a quiet retreat space, reducing sensory overload, or adjusting academic demands during emotionally challenging periods. Mona Delahooke's work emphasises the importance of understanding behaviour as communication, encouraging educators to look beyond surface reactions to identify underlying needs.

Consistent, predictable responses from adults help children feel safe whilst learning new regulatory skills. When emotional dysregulation occurs, focus on co-regulation first, offering your calm presence before attempting to teach or redirect behaviour. Simple phrases like "I can see this is really hard for you" validate their experience whilst maintaining connection. Remember that building emotional regulation skills takes time, with progress often occurring in small, incremental steps rather than dramatic breakthroughs.

A revolution in has occurred in the past two decades, transforming how we view the connections between learning, emotions, and the brain. A growing body of evidence suggests that emotions and learning are inevitably linked.

We all know that 'we feel, therefore we learn'. Emotional learningis a key aspect of teaching children, so in this blog post, we will be exploring different strategies in which to support it within the school context.

Teachers often disregard a child's emotions in favour of expecting him or her to give their best effort to the task at hand because they believe that emotion is separate from cognition. We've also heard the distinction before, differentiated as matters of the heart and matters of the mind, but there is no truth to this at all and it is a complete misconception for emotion and cognition to be considered as two separate entities. Rather, both emotion and cognition are interlinked and equally contribute to the control of thought and behaviour.

Emotional regulation is the process of managing and controlling emotions in order to create an optimal learning environment. It involves recognising and understanding feelings, constructively expressing them, moderating emotional responses through strategies such as self-regulation or calming activities, and using appropriate problem-solving methods.

The goal of emotional regulation is to help individuals manage their emotions so that they are better able to think logically and engage productively in learning tasks without disruption.

Emotions and cognition are deeply interconnected, not separate systems as traditionally believed. When students experience strong emotions, these feelings directly impact their ability to process information, concentrate, and retain new knowledge. Research shows that emotional states can either enhance or block cognitive functions, making emotional awareness crucial for effective learning.

A key area in the field of neuroscience is the interaction between emotion and cognition and it is this interaction which is essential for the adaptation of individuals to the environment. Emotion and cognition work together to activate particular brain areas, systems, and behaviours that seek adaptable responses to the event.

feedback loops" loading="lazy">

feedback loops" loading="lazy">This interaction plays a significant role in the attentional deployment as well as the processes and regulation of emotion and cognition, which are integrated very early in development and have a great impact on later development too. In fact, emotions serve as an influential medium for increasing or impeding learning, therefore, they are critical in students' academic development.

When our emotions are so intense that we become dysregulated, our executive function (the management system of our brain) does not work at full capacity. Our ability to think clearly and put the executive function into action is directly related to what we feel and how intensely we feel it.

The two key brain areas for emotion regulation, the pre-frontal cortex, and the amygdala, would be unable to interact with one another in a dysregulated state, leaving our emotions in charge (emotional dysregulation).

As the emotions decrease in their intensity, they become easier to manage. When emotions are well-managed, the pathways in the brain re-open, freeing up space for the executive function to mobilise. Therefore, emotion and cognition are working in tandem in order to function well.

Children with poor emotion regulation experience increased conflicts with teachers, struggle academically, and have difficulty forming positive peer relationships. These early regulation challenges often predict long-term academic difficulties and behavioural problems throughout their school years. Without intervention, dysregulated emotions can shut down a child's ability to think clearly and engage in classroom activities.

Research (Rudasill & RimmKaufman, 2009) shows that in educational settings, preschool children with low emotion regulation skills have more conflict with their teachers. Poor emotion regulation has a detrimental effect on academic performance and social emotional learning. It can also result in internalising and externalising disorders, which add to societal issues.

Therefore, integrating knowledge about cognitive emotion regulation strategies within the education system is crucial to enable a decrease in educational problems, such as absenteeism, poor school performance, early school leavers, poor interpersonal skills, and deficits in higher-order cognitive processes.

Teachers should also watch for academic performance indicators that may signal emotional regulation difficulties. Children experiencing emotional challenges often show decreased concentration spans, increased errors in familiar tasks, or reluctance to participate in activities they previously enjoyed. These academic red flags frequently appear before more obvious behavioural disruptions, making them valuable early intervention opportunities.

The classroom-wide impact becomes particularly evident during transitions, group activities, and high-pressure situations such as assessments. When children cannot regulate their emotions effectively, these moments can trigger widespread dysregulation throughout the class. Teachers may notice increased noise levels, difficulty maintaining focus during lessons, or peer conflicts becoming more frequent and intense. Understanding these patterns helps educators anticipate challenging periods and prepare appropriate support strategies.

Effective classroom management for emotional regulation involves creating predictable routines, establishing clear emotional vocabulary, and implementing consistent calming strategies. Simple techniques such as designated quiet spaces, visual emotion charts, and regular check-ins can significantly reduce the likelihood of emotional escalation affecting the broader classroom environment whilst supporting individual children's developmental needs.

Teachers can significantly enhance children's emotion regulation through structured modelling and explicit instruction. Research by Marc Brackett demonstrates that when educators consistently name and discuss emotions in real-time classroom situations, children develop stronger emotional vocabulary and self-awareness. Begin by narrating your own emotional responses: "I notice I'm feeling frustrated because the projector isn't working, so I'm going to take three deep breaths before we continue." This transparent approach helps children understand that all emotions are normal and manageable.

Creating predictable classroom routines supports emotional regulation by reducing cognitive load, as Daniel Siegel's research on the developing brain shows. Implement transition signals, visual schedules, and consistent response patterns to help children anticipate changes and prepare emotionally. When disruptions occur, guide children through problem-solving steps rather than simply correcting behaviour: "What are you feeling right now? What might help you feel calmer?"

Establish a dedicated calm-down space equipped with sensory tools like stress balls, breathing prompt cards, or noise-reducing headphones. Teach specific techniques such as the "balloon breathing" method or progressive muscle relaxation during neutral moments, so children can access these strategies when emotions run high. Remember that emotion regulation develops gradually; consistent practice and patience yield the strongest educational impact.

Emotion regulation develops predictably across childhood, with distinct milestones that directly impact classroom behaviour and learning. In early years (ages 3-6), children rely heavily on external support from adults to manage their emotions, as their prefrontal cortex is still developing. Ross Thompson's research demonstrates that young children need co-regulation from teachers, who serve as emotional scaffolds through calming presence, predictable routines, and explicit emotional vocabulary instruction.

Middle childhood (ages 7-11) marks a crucial transition period where children begin developing internal regulation strategies. During this phase, children can start learning cognitive techniques like counting to ten or identifying physical signs of emotional arousal. However, they still benefit enormously from structured practice and clear expectations. Consistent classroom frameworks become essential, as children at this age are building their emotional toolkit but cannot yet reliably access these skills under stress.

Adolescents (ages 12-18) possess more sophisticated cognitive abilities but face unique neurological challenges, as the emotional centres of their brains develop faster than areas responsible for impulse control. Practical classroom strategies should focus on teaching metacognitive awareness, helping students recognise their emotional patterns and develop personalise d regulation strategies. Creating opportunities for reflection and peer support proves particularly effective during this developmental stage.

The physical and emotional atmosphere of a classroom profoundly influences children's capacity for emotion regulation and subsequent learning outcomes. Research by Patricia Jennings demonstrates that emotionally supportive environments reduce cortisol levels in students, creating optimal conditions for cognitive processing and emotional development. When teachers establish predictable routines, clear expectations, and warm interpersonal relationships, children develop the psychological safety necessary to practice and refine their emotion regulation skills throughout the school day.

Creating such environments requires deliberate attention to both structural and relational elements. Consistent daily routines provide the predictability that helps anxious or dysregulated children feel secure, while designated quiet spaces offer opportunities for emotional reset when needed. Equally important is the teacher's own emotional presence; when educators model calm responses to classroom challenges and acknowledge children's feelings without judgement, they demonstrate effective emotion regulation strategies in real-time.

Practical implementation begins with simple environmental modifications: establishing clear visual cues for different activities, maintaining organised learning spaces that reduce sensory overwhelm, and incorporating regular check-ins that normalise emotional awareness. Teachers who proactively teach emotion vocabulary and provide scaffolded opportunities for children to express their feelings create classrooms where emotion regulation becomes an integral part of the learning process rather than a barrier to it.

Some children require additional support beyond universal classroom strategies to develop effective emotion regulation skills. These students may display persistent emotional outbursts, withdrawal behaviours, or difficulty recovering from distressing situations. Research by Bruce Perry demonstrates that children who have experienced trauma or chronic stress often have heightened stress response systems, making emotional self-regulation particularly challenging in busy classroom environments.

Creating individualised support plans becomes essential for these learners. Start by identifying specific triggers and early warning signs, then collaborate with the child to develop personalised coping strategies they can access independently. Consider environmental modifications such as providing a quiet retreat space, reducing sensory overload, or adjusting academic demands during emotionally challenging periods. Mona Delahooke's work emphasises the importance of understanding behaviour as communication, encouraging educators to look beyond surface reactions to identify underlying needs.

Consistent, predictable responses from adults help children feel safe whilst learning new regulatory skills. When emotional dysregulation occurs, focus on co-regulation first, offering your calm presence before attempting to teach or redirect behaviour. Simple phrases like "I can see this is really hard for you" validate their experience whilst maintaining connection. Remember that building emotional regulation skills takes time, with progress often occurring in small, incremental steps rather than dramatic breakthroughs.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/emotion-regulation#article","headline":"Emotion Regulation","description":"Explore the importance of emotion regulation in children's learning and development. Discover strategies teachers can use to encourage emotional well-being and...","datePublished":"2023-03-10T17:15:48.584Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/emotion-regulation"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69525b45ce83d2b1303d5055_69525b43ff04fe1ab3a3972c_emotion-regulation-infographic.webp","wordCount":3565},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/emotion-regulation#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Emotion Regulation","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/emotion-regulation"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is Emotion Regulation?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"A revolution in has occurred in the past two decades, transforming how we view the connections between learning, emotions, and the brain. A growing body of evidence suggests that emotions and learning are inevitably linked."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Do Emotions Affect Learning in the Classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Emotions and cognition are deeply interconnected, not separate systems as traditionally believed. When students experience strong emotions, these feelings directly impact their ability to process information, concentrate, and retain new knowledge. Research shows that emotional states can either enhance or block cognitive functions, making emotional awareness crucial for effective learning."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Happens When Children Can't Regulate Their Emotions?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Children with poor emotion regulation experience increased conflicts with teachers, struggle academically, and have difficulty forming positive peer relationships. These early regulation challenges often predict long-term academic difficulties and behavioural problems throughout their school years. Without intervention, dysregulated emotions can shut down a child's ability to think clearly and engage in classroom activities."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Can Teachers Help Children Develop Emotion Regulation Skills?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can significantly enhance children's emotion regulation through structured modelling and explicit instruction . Research by Marc Brackett demonstrates that when educators consistently name and discuss emotions in real-time classroom situations, children develop stronger emotional vocabulary and self-awareness. Begin by narrating your own emotional responses: \"I notice I'm feeling frustrated because the projector isn't working, so I'm going to take three deep breaths before we continue.\""}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Does Emotion Regulation Develop Across Different Ages?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Emotion regulation develops predictably across childhood, with distinct milestones that directly impact classroom behaviour and learning. In early years (ages 3-6), children rely heavily on external support from adults to manage their emotions, as their prefrontal cortex is still developing. Ross Thompson's research demonstrates that young children need co-regulation from teachers, who serve as emotional scaffolds through calming presence, predictable routines, and explicit emotional vocabulary "}}]}]}