ATL Skills: A teacher's guide

Explore how ATL skills can be embedded in the classroom to enhance learning, foster critical thinking, and develop lifelong learners across IB programs.

Explore how ATL skills can be embedded in the classroom to enhance learning, foster critical thinking, and develop lifelong learners across IB programs.

The Approaches to Learning Skills (ATL Skills) are a foundational component of the , spanning its four distinct pathways: the Primary Years Program (PYP), Middle Years Program (MYP), Diploma Program (DP), and Career Path (CP). These skills are carefully designed to teach students "how to learn," equipping them with strategies to succeed across disciplines while developing a shared language between teachers and learners to support reflection and growth throughout the learning process.

| Skill Category | PYP Focus | MYP/DP Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Thinking Skills | Critical and creative thinking foundations | Advanced analysis and evaluation |

| Social Skills | Collaboration and teamwork basics | Complex group dynamics and leadership |

| Communication | Expressing ideas clearly | Formal presentations and academic writing |

| Self-Management | Organisation and time management | Independent learning and goal-setting |

| Research Skills | Finding and organising information | Academic research and citations |

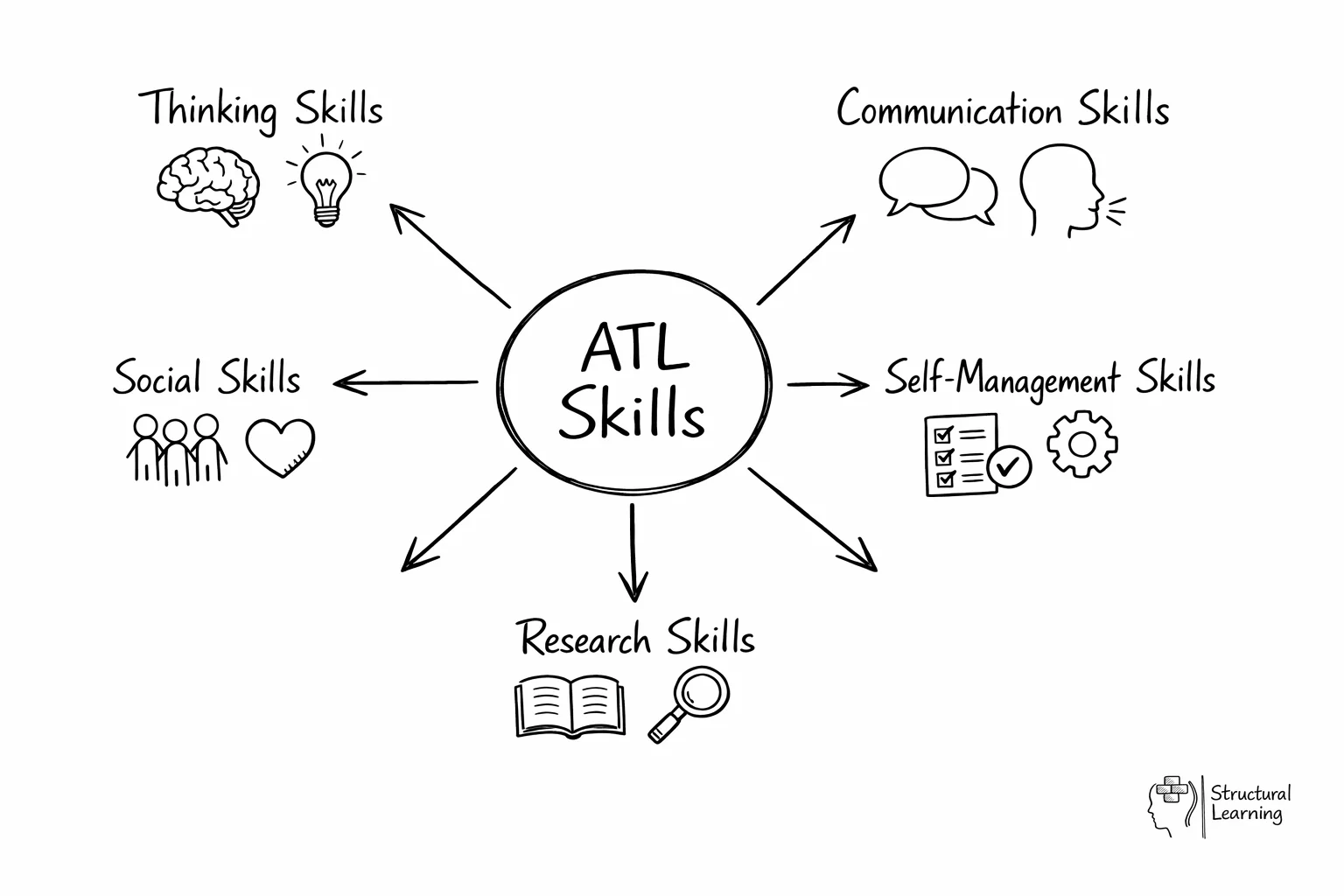

The ATL Skills framework emphasises the development of five broad skill categories:

Within these categories, skills are further refined into sub-skills, aligning intentionally with the goals of inquiry-based learning and transdisciplinary education. For example, research skills encompass information literacy and media literacy, critical for navigating today's complex information landscape.

In recent years, education has shifted from focusing solely on generic skills to embracing approaches that integrate both individual skill development and subject-specific knowledge. This balance ensures that learning remains complete, developing not just academic achievement but also the attributes of the Learner Profile, qualities that prepare students to engage meaningfully with local, national, and global communities.

In this article, we will explore the ATL Skills within the Primary Years Program (PYP), delving into how these skills, paired with the Learner Profile, helps students to thrive in inquiry-based learning environments. By adopting the ATL Skills framework, schools can create enriched activities that guide students in becoming adaptable, reflective, and lifelong learners.

Approaches to Learning Skills are foundational to the IB's focus on equipping students with transferable learning strategies that transcend individual disciplines. For teachers new to the IB, understanding how to teach ATLs effectively involves recognising their cross-disciplinary nature and embedding them smoothly into lesson design.

Take research skills as an example: students might learn to identify relevant information using techniques like skimming, scanning, or pinpointing keywords. These same skills could be applied during a social studies project analysing primary sources or a literacy session reading non-fiction texts. The key lies in explicitly teaching these skills and modeling their application in varied contexts, ensuring students grasp how to transfer them across subjects.

Explicit teaching means going beyond telling students what to do, it involves showing them how. For instance, when teaching critical thinking, illustrate your own thought process by thinking aloud as you evaluate a source. Describe the steps you take to assess credibility, identify biases, and draw reasoned conclusions. By making your thinking visible, you provide students with a concrete model to emulate.

Another vital aspect of integrating ATLs is co-constructing success criteria. Instead of simply handing out a rubric, engage students in a conversation about what effective application of a particular skill looks like. For example, if the focus is on collaboration, ask students: "What behaviours demonstrate effective teamwork?" or "How can we ensure everyone's voice is heard?" By involving students in defining success, you creates ownership and create a shared understanding of expectations.

Use effective questioning to stimulate self-reflection and metacognitive awareness. Asking ‘how’ questions (such as ‘How did you approach this problem?’ or ‘How could you improve your communication in group work?’) can prompt learners to actively consider their strategies and approaches. Using techniques like MISO (Mistake, Insight, Surprise, and Overall) can help make this reflection meaningful. Rather than focusing solely on the final product, the emphasis shifts to the learning process itself. Encourage your students to articulate what they found challenging, what they learned, and how they might adjust their approach in the future.

To make ATL skills tangible, consider these examples of classroom activities designed to develop specific skills:

Effective ATL implementation requires carefully designed activities that explicitly develop specific skills whilst engaging with subject content. For developing critical thinking skills, teachers might use the 'Claim-Evidence-Reasoning' framework where students analyse historical sources, evaluate scientific data, or critique literary arguments. This approach helps students understand that critical thinking follows a systematic process rather than being an innate ability.

Self-management skills can be developed through project-based learning that incorporates reflection journals and goal-setting templates. Students track their progress, identify obstacles, and adjust their strategies accordingly. Research by Zimmerman and Moylan shows that such self-regulated learning strategies significantly improve academic outcomes. Communication skills benefit from structured peer feedback protocols and presentation frameworks that provide scaffolding for effective expression and active listening.

Social skills develop naturally through collaborative inquiry projects where students must negotiate roles, resolve conflicts, and build consensus. These activities should include explicit discussion about group dynamics and communication strategies, making the invisible processes of collaboration visible to students.

While ATL skills are not typically assessed through traditional tests, they can be evaluated using a variety of methods that provide insight into a student’s growth and proficiency. Observations, self-assessments, peer feedback, and portfolios are valuable tools for gauging skill development. Create rubrics that clearly outline the criteria for each skill, allowing students to understand expectations and track their progress. Regularly provide targeted feedback that highlights areas of strength and areas for improvement, helping students to take ownership of their learning journey.

The five ATL skill categories form a comprehensive framework that mirrors how students naturally engage with learning across all IB programmes. Thinking skills encompass critical and creative thinking, transfer, and metacognition, whilst communication skills include reading, writing, speaking, listening, and viewing. Social skills focus on collaboration and managing relationships, self-management skills address organisation, affective states, and reflection, and research skills involve information literacy, media literacy, and ethical use of knowledge.

Each category operates interdependently rather than in isolation, reflecting Daniel Willingham's research on cognitive science which demonstrates that skills develop most effectively when embedded within meaningful contexts. For instance, when students collaborate on a research project, they simultaneously develop social skills through teamwork, research skills through information gathering, and self-management skills through time organisation. This interconnected approach aligns with constructivist learning theory, where students build understanding through active engagement with multiple skill sets.

Effective classroom implementation requires teachers to identify natural convergence points where multiple ATL categories intersect within existing curriculum content. Rather than teaching skills in isolation, design learning experiences where students might use thinking skills to analyse sources, communication skills to present findings, and social skills to collaborate effectively. This integrated approach ensures skill development feels purposeful and authentic to students whilst maintaining curricular focus.

Assessing ATL skills requires a fundamental shift from traditional summative evaluation towards formative, process-focused methods that capture skill development over time. Portfolio-based assessment emerges as particularly effective, allowing students to document their learning journey whilst developing reflection and self-management capabilities. Research by Black and Wiliam on formative assessment demonstrates that when students actively participate in evaluating their own progress, learning outcomes improve significantly across all skill areas.

Effective ATL assessment combines multiple data sources, including peer feedback, learning journals, and structured observation rubrics that focus on skill application rather than content mastery alone. Self-assessment tools such as learning logs and metacognitive questionnaires enable students to identify their strengths and areas for growth, developing the very reflection skills that ATL development seeks to nurture. Teachers should establish clear success criteria for each skill category, ensuring students understand what progression looks like in practical terms.

Implementation begins with selecting 2-3 ATL skills per unit, creating simple tracking systems that students can manage independently. Consider introducing skill-focused conferences where students present evidence of their development, supported by specific examples from their work. This approach transforms assessment from external judgement to collaborative dialogue, reinforcing the student agency that lies at the heart of successful ATL implementation.

The developmental readiness of students fundamentally shapes how ATL skills should be introduced and practised across IB programmes. In the Primary Years Programme, concrete experiences and scaffolded practice form the foundation for skill acquisition. Young learners benefit from explicit modelling of thinking processes, such as teachers verbalising their decision-making during problem-solving tasks. As Vygotsky's zone of proximal development suggests, students require guided support before independent application becomes possible.

Middle Years Programme students demonstrate increased capacity for abstract thinking and self-regulation, allowing for more sophisticated metacognitive strategies. This developmental shift enables teachers to introduce reflection journals, peer assessment protocols, and goal-setting frameworks that would overwhelm younger learners. Research by Zimmerman on self-regulated learning indicates that adolescents can effectively monitor their own progress when provided with appropriate tools and structures.

Diploma Programme implementation should emphasise student ownership and transfer of ATL skills across subject boundaries. At this level, teachers become facilitators rather than direct instructors of skill development. Students can analyse their own learning patterns, evaluate the effectiveness of different strategies, and adapt their approaches based on task demands. Practical implementation might include cross-curricular projects where students explicitly document which ATL skills they employ and reflect on their effectiveness in different contexts.

Despite widespread recognition of ATL skills' importance, many educators encounter predictable obstacles during implementation. Time constraints consistently emerge as the primary challenge, with teachers feeling pressure to cover curriculum content whilst simultaneously developing transferable skills. Research by Dylan Wiliam on formative assessment reveals that successful skill integration requires explicit modelling and frequent practice, yet these elements often compete with perceived content delivery demands.

Student resistance represents another significant hurdle, particularly when learners expect traditional teacher-directed instruction. Cognitive load theory, as developed by John Sweller, suggests that introducing metacognitive strategies alongside complex content can overwhelm students initially. However, this challenge diminishes when teachers scaffold skill development systematically, beginning with simple reflection techniques before progressing to sophisticated self-regulation strategies.

The most effective solution involves embedding ATL skills within existing curriculum activities rather than treating them as additional requirements. For instance, developing thinking skills through subject-specific problem-solving tasks simultaneously addresses content objectives and skill development. Teachers report greater success when they focus on two or three core ATL skills per term, allowing sufficient time for students to internalise these competencies before introducing additional elements.

Approaches to Learning Skills form the bedrock of effective, student-centred education. By integrating these skills into your teaching practice, you are not just preparing students for academic success; you are equipping them with the tools they need to thrive in an ever-changing world. The explicit teaching of ATLs, combined with reflective practice and meaningful assessment, helps students to become self-directed, lifelong learners who are ready to embrace the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century.

As educators, our role extends beyond the transmission of knowledge; we are facilitators of learning. By developing a classroom culture that values inquiry, collaboration, and reflection, we can create an environment where ATL skills flourish. Embrace the ATL framework as a powerful tool for transforming your teaching and helping your students to become active, engaged, and successful learners.

Approaches to learning research

The Approaches to Learning Skills (ATL Skills) are a foundational component of the , spanning its four distinct pathways: the Primary Years Program (PYP), Middle Years Program (MYP), Diploma Program (DP), and Career Path (CP). These skills are carefully designed to teach students "how to learn," equipping them with strategies to succeed across disciplines while developing a shared language between teachers and learners to support reflection and growth throughout the learning process.

| Skill Category | PYP Focus | MYP/DP Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Thinking Skills | Critical and creative thinking foundations | Advanced analysis and evaluation |

| Social Skills | Collaboration and teamwork basics | Complex group dynamics and leadership |

| Communication | Expressing ideas clearly | Formal presentations and academic writing |

| Self-Management | Organisation and time management | Independent learning and goal-setting |

| Research Skills | Finding and organising information | Academic research and citations |

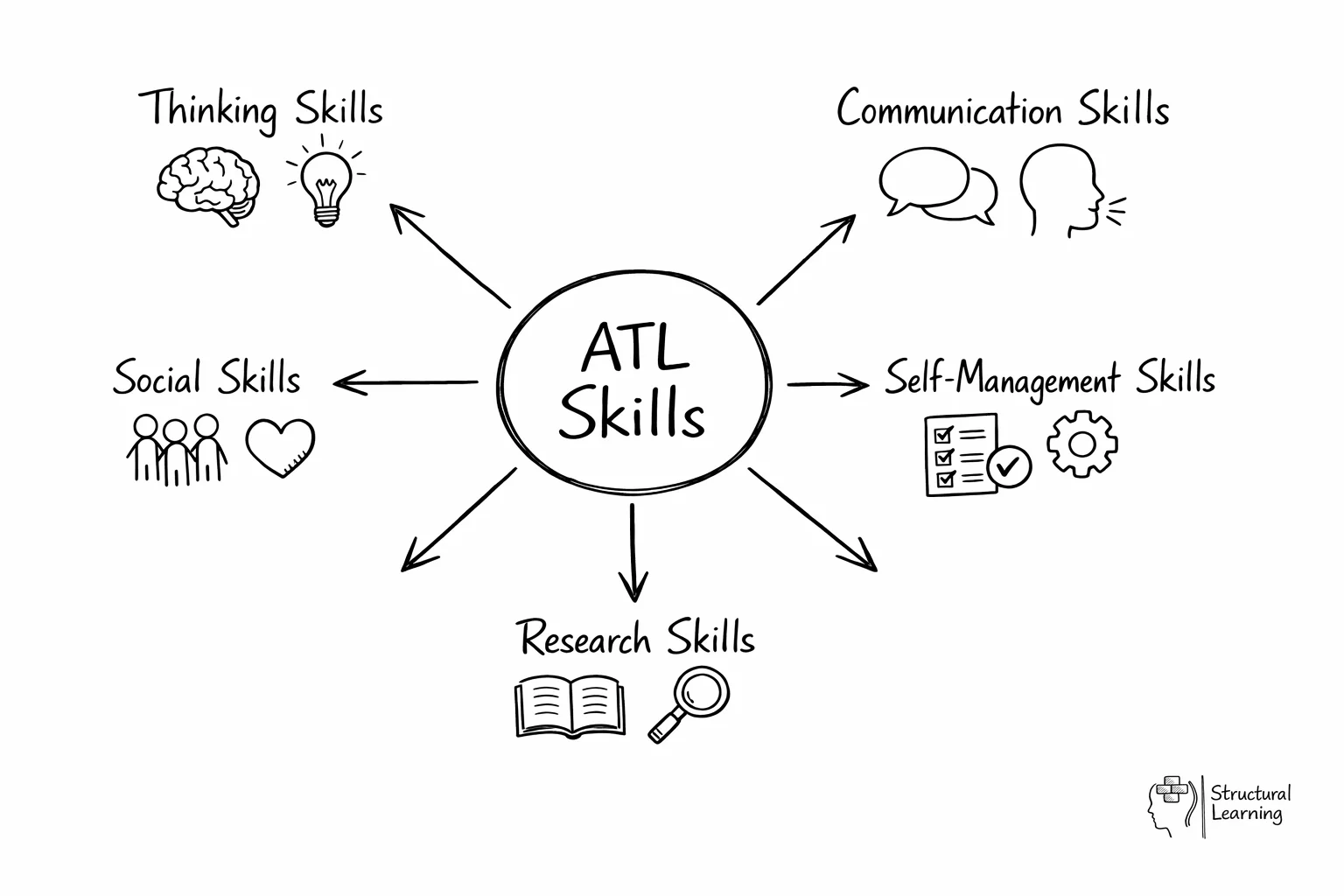

The ATL Skills framework emphasises the development of five broad skill categories:

Within these categories, skills are further refined into sub-skills, aligning intentionally with the goals of inquiry-based learning and transdisciplinary education. For example, research skills encompass information literacy and media literacy, critical for navigating today's complex information landscape.

In recent years, education has shifted from focusing solely on generic skills to embracing approaches that integrate both individual skill development and subject-specific knowledge. This balance ensures that learning remains complete, developing not just academic achievement but also the attributes of the Learner Profile, qualities that prepare students to engage meaningfully with local, national, and global communities.

In this article, we will explore the ATL Skills within the Primary Years Program (PYP), delving into how these skills, paired with the Learner Profile, helps students to thrive in inquiry-based learning environments. By adopting the ATL Skills framework, schools can create enriched activities that guide students in becoming adaptable, reflective, and lifelong learners.

Approaches to Learning Skills are foundational to the IB's focus on equipping students with transferable learning strategies that transcend individual disciplines. For teachers new to the IB, understanding how to teach ATLs effectively involves recognising their cross-disciplinary nature and embedding them smoothly into lesson design.

Take research skills as an example: students might learn to identify relevant information using techniques like skimming, scanning, or pinpointing keywords. These same skills could be applied during a social studies project analysing primary sources or a literacy session reading non-fiction texts. The key lies in explicitly teaching these skills and modeling their application in varied contexts, ensuring students grasp how to transfer them across subjects.

Explicit teaching means going beyond telling students what to do, it involves showing them how. For instance, when teaching critical thinking, illustrate your own thought process by thinking aloud as you evaluate a source. Describe the steps you take to assess credibility, identify biases, and draw reasoned conclusions. By making your thinking visible, you provide students with a concrete model to emulate.

Another vital aspect of integrating ATLs is co-constructing success criteria. Instead of simply handing out a rubric, engage students in a conversation about what effective application of a particular skill looks like. For example, if the focus is on collaboration, ask students: "What behaviours demonstrate effective teamwork?" or "How can we ensure everyone's voice is heard?" By involving students in defining success, you creates ownership and create a shared understanding of expectations.

Use effective questioning to stimulate self-reflection and metacognitive awareness. Asking ‘how’ questions (such as ‘How did you approach this problem?’ or ‘How could you improve your communication in group work?’) can prompt learners to actively consider their strategies and approaches. Using techniques like MISO (Mistake, Insight, Surprise, and Overall) can help make this reflection meaningful. Rather than focusing solely on the final product, the emphasis shifts to the learning process itself. Encourage your students to articulate what they found challenging, what they learned, and how they might adjust their approach in the future.

To make ATL skills tangible, consider these examples of classroom activities designed to develop specific skills:

Effective ATL implementation requires carefully designed activities that explicitly develop specific skills whilst engaging with subject content. For developing critical thinking skills, teachers might use the 'Claim-Evidence-Reasoning' framework where students analyse historical sources, evaluate scientific data, or critique literary arguments. This approach helps students understand that critical thinking follows a systematic process rather than being an innate ability.

Self-management skills can be developed through project-based learning that incorporates reflection journals and goal-setting templates. Students track their progress, identify obstacles, and adjust their strategies accordingly. Research by Zimmerman and Moylan shows that such self-regulated learning strategies significantly improve academic outcomes. Communication skills benefit from structured peer feedback protocols and presentation frameworks that provide scaffolding for effective expression and active listening.

Social skills develop naturally through collaborative inquiry projects where students must negotiate roles, resolve conflicts, and build consensus. These activities should include explicit discussion about group dynamics and communication strategies, making the invisible processes of collaboration visible to students.

While ATL skills are not typically assessed through traditional tests, they can be evaluated using a variety of methods that provide insight into a student’s growth and proficiency. Observations, self-assessments, peer feedback, and portfolios are valuable tools for gauging skill development. Create rubrics that clearly outline the criteria for each skill, allowing students to understand expectations and track their progress. Regularly provide targeted feedback that highlights areas of strength and areas for improvement, helping students to take ownership of their learning journey.

The five ATL skill categories form a comprehensive framework that mirrors how students naturally engage with learning across all IB programmes. Thinking skills encompass critical and creative thinking, transfer, and metacognition, whilst communication skills include reading, writing, speaking, listening, and viewing. Social skills focus on collaboration and managing relationships, self-management skills address organisation, affective states, and reflection, and research skills involve information literacy, media literacy, and ethical use of knowledge.

Each category operates interdependently rather than in isolation, reflecting Daniel Willingham's research on cognitive science which demonstrates that skills develop most effectively when embedded within meaningful contexts. For instance, when students collaborate on a research project, they simultaneously develop social skills through teamwork, research skills through information gathering, and self-management skills through time organisation. This interconnected approach aligns with constructivist learning theory, where students build understanding through active engagement with multiple skill sets.

Effective classroom implementation requires teachers to identify natural convergence points where multiple ATL categories intersect within existing curriculum content. Rather than teaching skills in isolation, design learning experiences where students might use thinking skills to analyse sources, communication skills to present findings, and social skills to collaborate effectively. This integrated approach ensures skill development feels purposeful and authentic to students whilst maintaining curricular focus.

Assessing ATL skills requires a fundamental shift from traditional summative evaluation towards formative, process-focused methods that capture skill development over time. Portfolio-based assessment emerges as particularly effective, allowing students to document their learning journey whilst developing reflection and self-management capabilities. Research by Black and Wiliam on formative assessment demonstrates that when students actively participate in evaluating their own progress, learning outcomes improve significantly across all skill areas.

Effective ATL assessment combines multiple data sources, including peer feedback, learning journals, and structured observation rubrics that focus on skill application rather than content mastery alone. Self-assessment tools such as learning logs and metacognitive questionnaires enable students to identify their strengths and areas for growth, developing the very reflection skills that ATL development seeks to nurture. Teachers should establish clear success criteria for each skill category, ensuring students understand what progression looks like in practical terms.

Implementation begins with selecting 2-3 ATL skills per unit, creating simple tracking systems that students can manage independently. Consider introducing skill-focused conferences where students present evidence of their development, supported by specific examples from their work. This approach transforms assessment from external judgement to collaborative dialogue, reinforcing the student agency that lies at the heart of successful ATL implementation.

The developmental readiness of students fundamentally shapes how ATL skills should be introduced and practised across IB programmes. In the Primary Years Programme, concrete experiences and scaffolded practice form the foundation for skill acquisition. Young learners benefit from explicit modelling of thinking processes, such as teachers verbalising their decision-making during problem-solving tasks. As Vygotsky's zone of proximal development suggests, students require guided support before independent application becomes possible.

Middle Years Programme students demonstrate increased capacity for abstract thinking and self-regulation, allowing for more sophisticated metacognitive strategies. This developmental shift enables teachers to introduce reflection journals, peer assessment protocols, and goal-setting frameworks that would overwhelm younger learners. Research by Zimmerman on self-regulated learning indicates that adolescents can effectively monitor their own progress when provided with appropriate tools and structures.

Diploma Programme implementation should emphasise student ownership and transfer of ATL skills across subject boundaries. At this level, teachers become facilitators rather than direct instructors of skill development. Students can analyse their own learning patterns, evaluate the effectiveness of different strategies, and adapt their approaches based on task demands. Practical implementation might include cross-curricular projects where students explicitly document which ATL skills they employ and reflect on their effectiveness in different contexts.

Despite widespread recognition of ATL skills' importance, many educators encounter predictable obstacles during implementation. Time constraints consistently emerge as the primary challenge, with teachers feeling pressure to cover curriculum content whilst simultaneously developing transferable skills. Research by Dylan Wiliam on formative assessment reveals that successful skill integration requires explicit modelling and frequent practice, yet these elements often compete with perceived content delivery demands.

Student resistance represents another significant hurdle, particularly when learners expect traditional teacher-directed instruction. Cognitive load theory, as developed by John Sweller, suggests that introducing metacognitive strategies alongside complex content can overwhelm students initially. However, this challenge diminishes when teachers scaffold skill development systematically, beginning with simple reflection techniques before progressing to sophisticated self-regulation strategies.

The most effective solution involves embedding ATL skills within existing curriculum activities rather than treating them as additional requirements. For instance, developing thinking skills through subject-specific problem-solving tasks simultaneously addresses content objectives and skill development. Teachers report greater success when they focus on two or three core ATL skills per term, allowing sufficient time for students to internalise these competencies before introducing additional elements.

Approaches to Learning Skills form the bedrock of effective, student-centred education. By integrating these skills into your teaching practice, you are not just preparing students for academic success; you are equipping them with the tools they need to thrive in an ever-changing world. The explicit teaching of ATLs, combined with reflective practice and meaningful assessment, helps students to become self-directed, lifelong learners who are ready to embrace the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century.

As educators, our role extends beyond the transmission of knowledge; we are facilitators of learning. By developing a classroom culture that values inquiry, collaboration, and reflection, we can create an environment where ATL skills flourish. Embrace the ATL framework as a powerful tool for transforming your teaching and helping your students to become active, engaged, and successful learners.

Approaches to learning research

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/atl-skills-a-teachers-guide#article","headline":"ATL Skills: A teacher's guide","description":"Explore how ATL skills can be embedded in the classroom to enhance learning, foster critical thinking, and develop lifelong learners across IB programs.","datePublished":"2022-03-22T16:54:15.944Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/atl-skills-a-teachers-guide"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a1477cc16d20aa4fba6f2_696a1470cd5bc3816a6167c5_atl-skills-a-teachers-guide-illustration.webp","wordCount":4263},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/atl-skills-a-teachers-guide#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"ATL Skills: A teacher's guide","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/atl-skills-a-teachers-guide"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/atl-skills-a-teachers-guide#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What exactly are ATL Skills and how do they differ from traditional subject-specific skills?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"ATL Skills (Approaches to Learning Skills) are five foundational skill categories that teach students 'how to learn' rather than just subject content: thinking, communication, social, self-management, and research skills. Unlike traditional skills that remain within subject silos, ATL Skills are tra"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers effectively integrate ATL Skills into their daily lessons without it feeling like an add-on?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers should explicitly model ATL Skills during lessons rather than just telling students about them, such as demonstrating how to skim a text for specific details or breaking down complex skills into actionable steps. The key is to co-construct success criteria with students that clarify what su"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What does 'explicit teaching' of ATL Skills look like in practice?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Explicit teaching involves"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How do ATL Skills support transdisciplinary learning across different subjects?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"ATL Skills act as transferable strategies that create connections between disciplines, transforming fragmented lessons into cohesive transdisciplinary activities. For example, research skills like information literacy can be applied whether students are investigating a science inquiry or exploring g"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Which ATL Skills should teachers prioritise when planning a transdisciplinary unit?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers should intentionally select ATL Skills that align most closely with the unit's purpose and objectives rather than trying to cover all skills equally. For instance, a sustainability unit might emphasise self-management skills like goal-setting and organisation, whilst a collaborative unit re"}}]}]}