Ivan Pavlov's Theory

Explore Ivan Pavlov's groundbreaking theory on conditioned reflexes, a cornerstone in understanding human behavior and learning processes.

Explore Ivan Pavlov's groundbreaking theory on conditioned reflexes, a cornerstone in understanding human behavior and learning processes.

| Component/Phase | Timing | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditioned Stimulus (US) | Pre-existing | Naturally triggers a response without prior learning (e.g., food causing salivation) | Identify natural motivators like praise, rewards, or enjoyable activities |

| Unconditioned Response (UR) | Pre-existing | Natural, automatic response to the unconditioned stimulus | Recognize students' natural responses to build upon them |

| Neutral Stimulus | Before conditioning | Does not initially trigger the desired response (e.g., bell sound) | Choose classroom cues like bells, music, or visual signals |

| Acquisition Phase | During conditioning | Repeated pairing of neutral stimulus with unconditioned stimulus | Consistently pair classroom routines with positive experiences |

| Conditioned Stimulus (CS) | After conditioning | Former neutral stimulus now triggers response alone | Use established cues to manage transitions and behaviours |

| Conditioned Response (CR) | After conditioning | Learned response to the conditioned stimulus | Students respond automatically to classroom management signals |

| Extinction | Variable | Gradual weakening of conditioned response when CS presented without US | Maintain consistency to prevent loss of established routines |

| Spontaneous Recovery | After extinction | Return of conditioned response after a rest period | Be aware that old behaviours may resurface after breaks |

| Generalization | Post-conditioning | Response occurs to stimuli similar to the conditioned stimulus | Students may apply learned behaviours across different contexts |

| Discrimination | Post-conditioning | Ability to distinguish between similar stimuli | Teach students to differentiate between specific classroom cues |

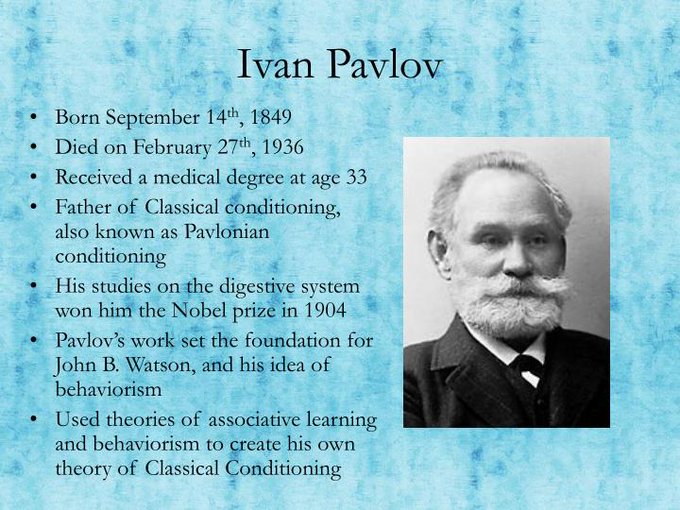

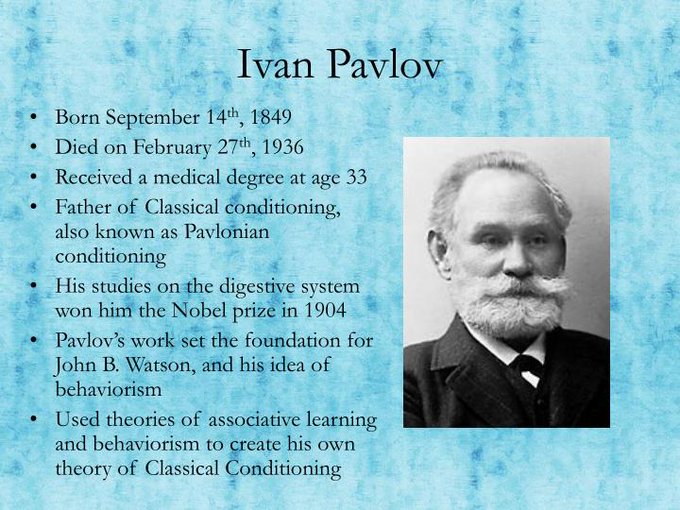

Ivan Pavlov, a prominent figure in the field of psychology, introduced a theory that transformed our understanding of . Should use present tense without specific year reference, or use the current year to how we understand human and animal learning processes. Born in 1849 in Russia, Pavlov initially pursued a career in medicine before turning his attention to the fascinating . He's widely recognised for his groundbreaking research on classical conditioning, which has left an indelible mark on the field.

Pavlov's theory, often referred to as Pavlovian conditioning, centres around the concept of associative learning. He sought to explore how organisms, including humans, and responses through repeated associations between stimuli.

His experiments primarily involved dogs, but the principles he discovered have far-reaching implications for as well.

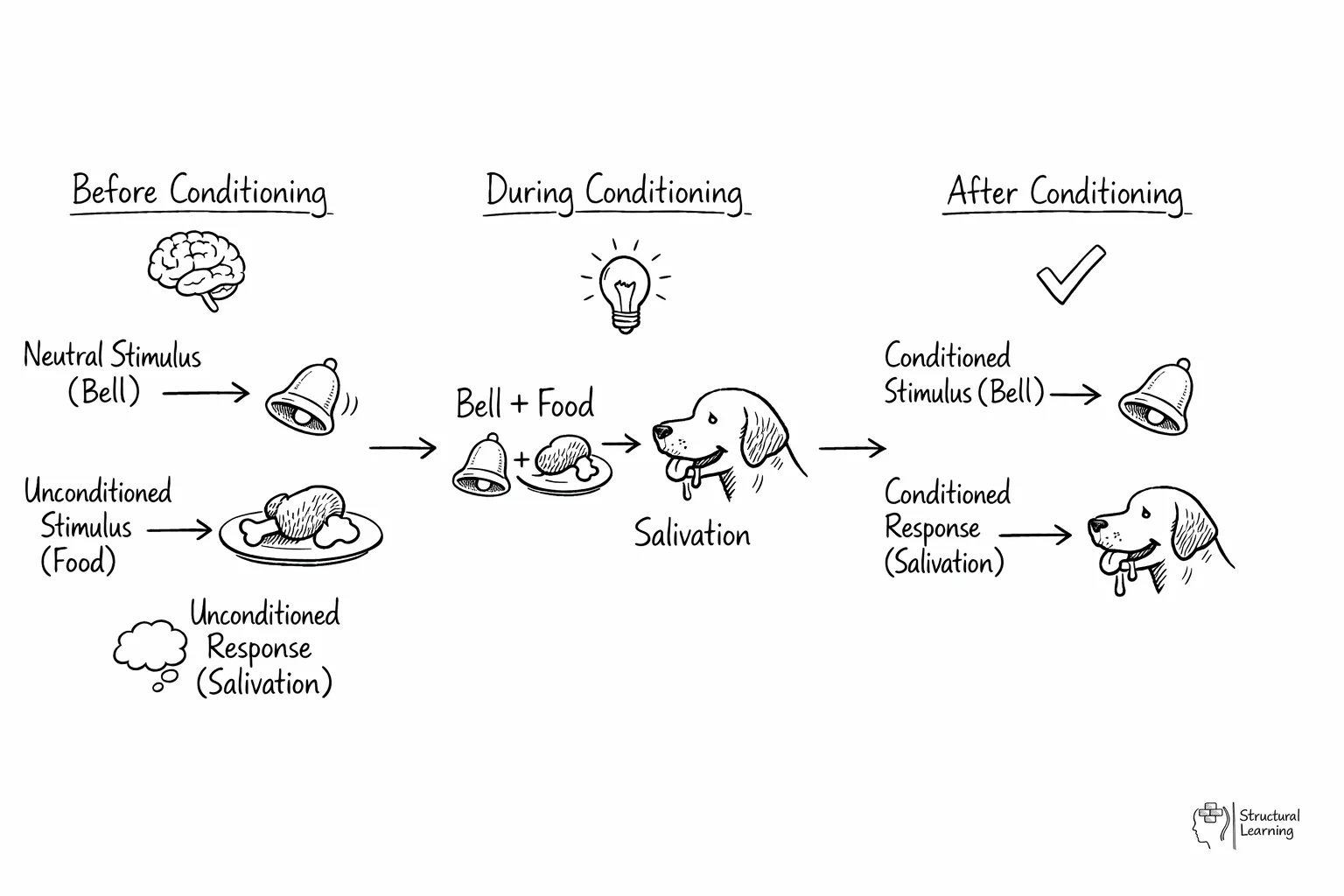

Classical conditioning, the foundation of Pavlov's theory, involves pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus to elicit a conditioned response. In one of his famous experiments, Pavlov observed that dogs naturally salivated when presented with food, an unconditioned stimulus. However, through repeated pairings of a neutral stimulus, such as a bell, with the food, the dogs eventually began to associate the bell with the arrival of food.

As a result, they started salivating at the sound of the bell alone, even in the absence of the food. This conditioned response demonstrated the formation of a new association between the neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus.

Pavlov's research on classical conditioning shed light on the underlying mechanisms of learning and provided a framework to understand how environmental stimuli can and responses. This theory has implications not only in psychology but also in various fields, including education, marketing, and therapy.

Contemporary perspectives have expanded upon his work, acknowledging the and individual . Nonetheless, Pavlov's contributions remain foundational to the study of learning and behaviour, and his theory continues to be an integral part of the curriculum for most students studying psychology. By understanding the basics of Pavlov's theory, we can examine deeper into the intricate workings of human and animal behaviour and gain valuable insights into the complex nature of our .

"Should include a relevant quote about classical conditioning with proper citation, or remove the quote.", Ivan Pavlov

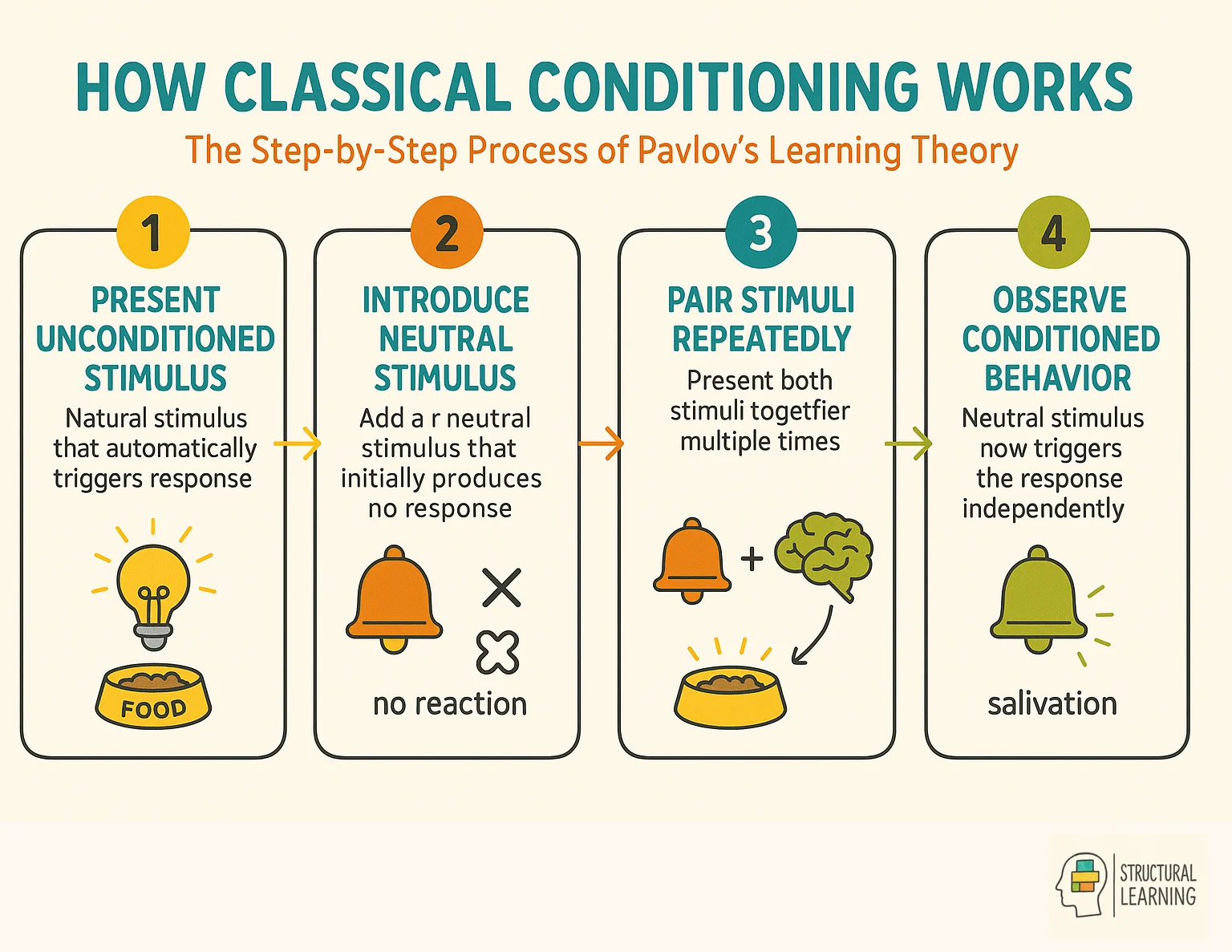

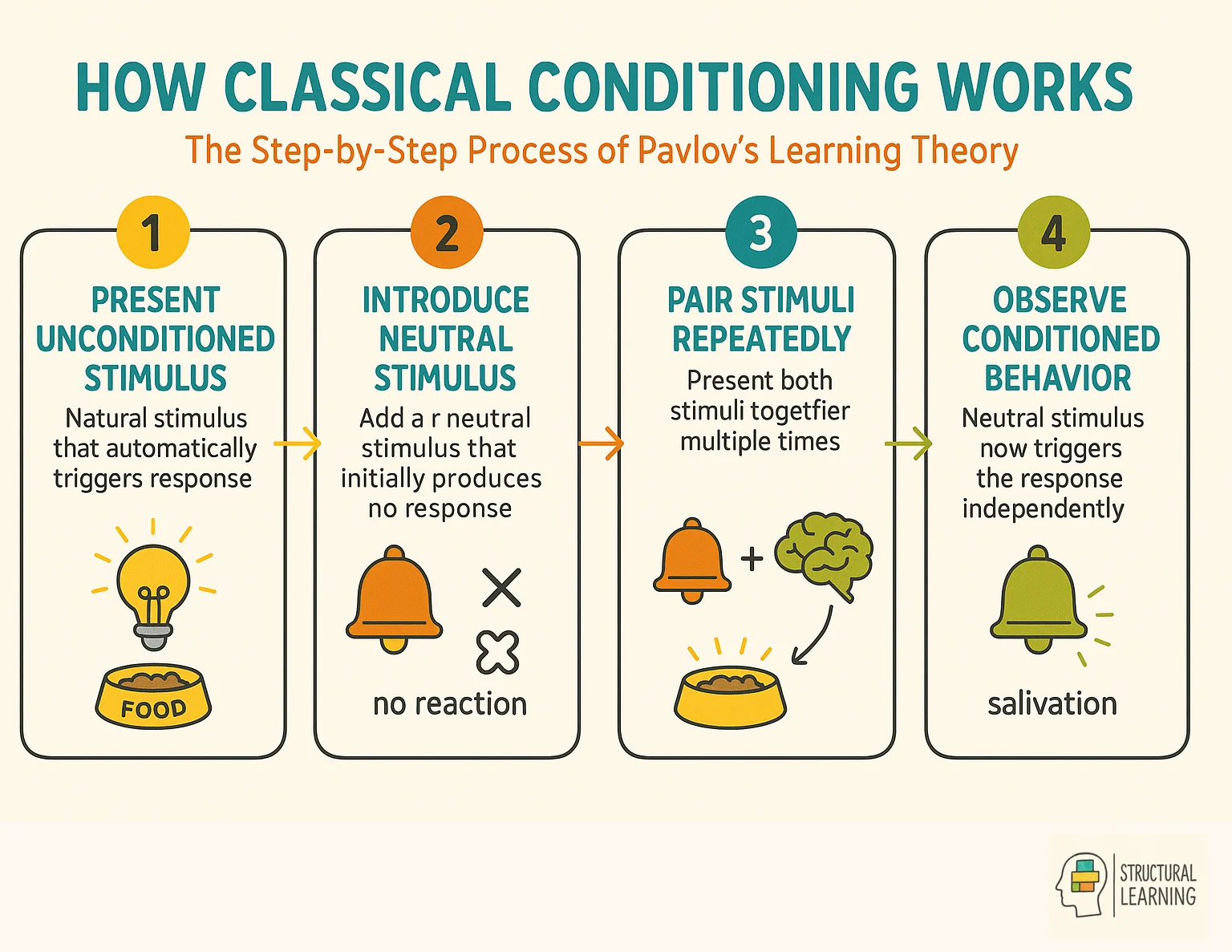

Classical conditioning works by pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus repeatedly until the neutral stimulus alone triggers a response. The process creates learned associations between environmental cues and automatic responses. This learning mechanism forms the foundation of Pavlov's behavioural theory.

Classical conditioning works by repeatedly pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus until the neutral stimulus alone triggers the desired response. The process involves presenting a stimulus that naturally causes a response (like food causing salivation) alongside a neutral stimulus (like a bell sound) until the neutral stimulus alone produces the response. This learning occurs automatically without conscious effort and forms the basis for many learned behaviours and emotional responses.

Classical conditioning stands as the bedrock of Pavlov's pioneering theory, which has profoundly impacted the field of psychology. This fundamental concept revolves around the process of learning through associations between stimuli, shedding light on how organisms, including humans, acquire new behaviours and responses. Pavlov's extensive research on classical conditioning, often referred to as Pavlovian conditioning, has left an indelible mark on our understanding of human and animal behaviour.

At its core, classical conditioning involves pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus to elicit a conditioned response. To comprehend this process, consider one of Pavlov's notable experiments with dogs. He observed that dogs naturally salivated in response to food, an unconditioned stimulus.

However, through repeated pairings of a , such as the sound of a bell, with the presentation of food, the dogs began to associate the bell with the imminent arrival of food. Consequently, they developed a conditioned response, salivating at the mere sound of the bell, even in the absence of the food itself. This conditioned response demonstrated the formation of a new association between the initially neutral stimulus (the bell) and the unconditioned stimulus (the food).

Classical conditioning, as established by Pavlov, reveals the profound influence of environmental stimuli on our behaviours and responses. The theory's significance extends beyond the , permeating diverse fields such as education, marketing, and therapy. By understanding the foundations of classical conditioning, we can gain valuable insights into the intricate processes that underlie learning and behaviour.

It's worth noting that while Pavlov's theory of classical conditioning has made remarkable contributions to psychology, it isn't without its critiques and limitations. Contemporary perspectives have further expanded upon his work, emphasising the role of cognitive processes and individual differences in conditioning.

Nonetheless, the core principles of classical conditioning remain pivotal to the study of human and animal behaviour, serving as a crucial component of most psychology curricula. By grasping the essence of classical conditioning, students embark on a journey of comprehension, enabling them to unravel the complexities of learning processes and uncover the profound mechanisms that shape our behaviours and responses.

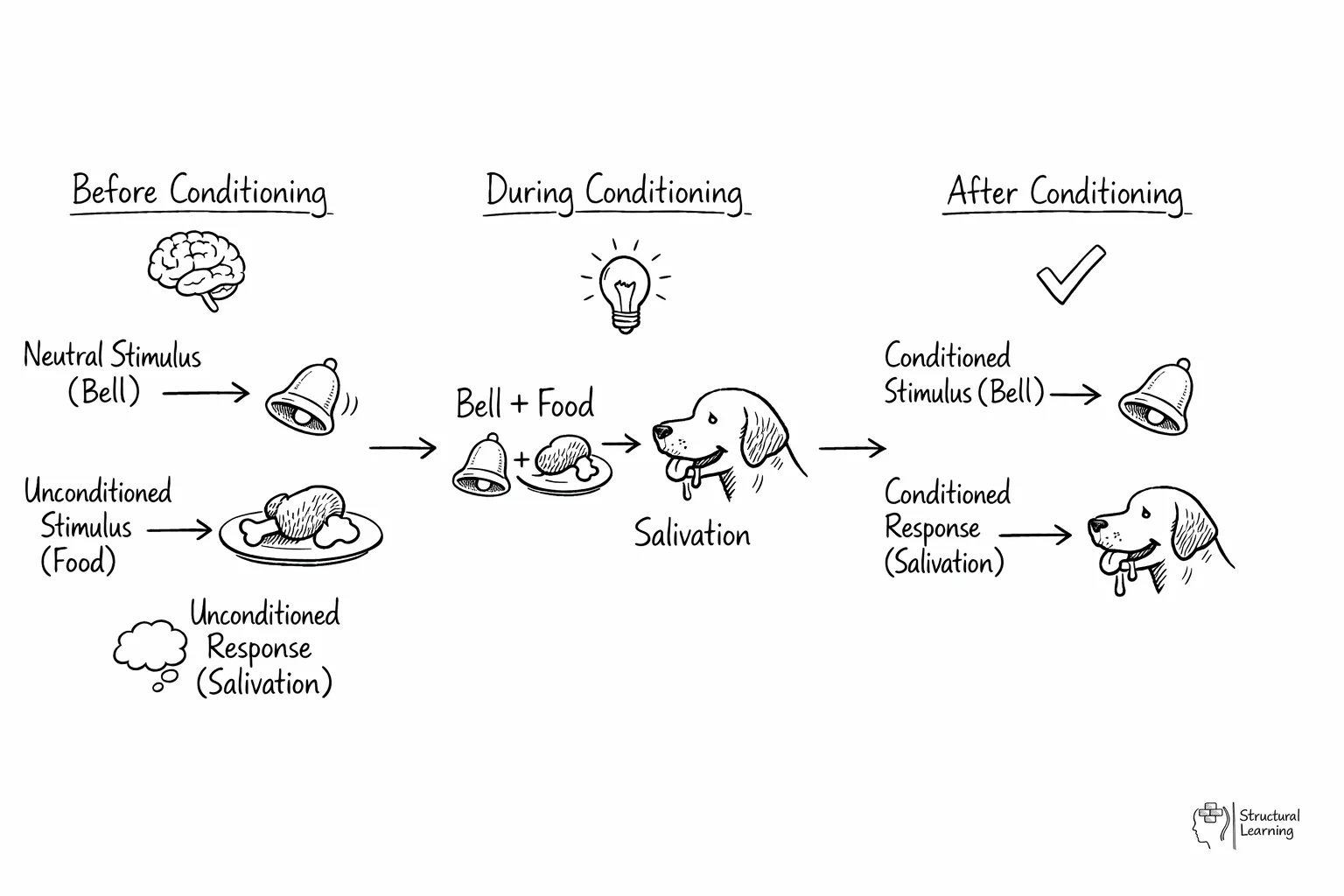

Pavlov's dog experiment demonstrated that dogs naturally salivated when presented with food, then learned to salivate when hearing a bell after repeated pairings. The bell became a conditioned stimulus that triggered salivation without food present. This experiment established the principles of classical conditioning.

In Pavlov's dog experiment, he rang a bell before feeding dogs, and after repeated pairings, the dogs began salivating at the sound of the bell alone. The experiment demonstrated that dogs could learn to associate the neutral stimulus (bell) with food, producing a conditioned response (salivation) even without food present. This groundbreaking study provided the first scientific evidence of how learning through association works in living organisms.

One of the pivotal experiments that laid the foundation for classical conditioning was conducted by a renowned researcher in the field of psychology. This groundbreaking study, often cited as a quintessential example of classical conditioning, revealed key insights into how organisms learn through associations between stimuli. The experiment involved dogs as the subjects, and its findings shed light on the fundamental principles that underpin Pavlov's theory.

In this seminal experiment, the researcher presented a neutral stimulus, such as the sound of a bell, to the dogs and simultaneously introduced an unconditioned stimulus, food. Naturally, the dogs responded by salivating in the presence of the food, a response known as the unconditioned response.

Through repeated pairings of the bell and the food, the researcher aimed to establish an association between the two stimuli.

Over time, a remarkable transformation occurred. The dogs began to associate the bell, initially a neutral stimulus, with the imminent arrival of food. As a result, the sound of the bell alone started to evoke a response similar to the original salivation triggered by the food.

This learned response, known as the conditioned response, demonstrated the formation of an association between the previously neutral stimulus (the bell) and the unconditioned stimulus (the food).

Pavlov's experiment provided a clear illustration of classical conditioning in action. It showcased how a neutral stimulus can acquire the capacity to elicit a response through repeated pairings with a biologically significant stimulus.

The study highlighted the significance of temporal contiguity, the close proximity in time between the neutral and unconditioned stimuli, for successful conditioning to take place.

This experiment serves as a pivotal example of behavioural psychology, as it encapsulates the core principles of classical conditioning. By understanding the basics of Pavlov's experiment, students gain valuable insights into the intricate process of learning through associative associations. It paves the way for further exploration of the complexities of classical conditioning and its application in diverse areas of psychology.

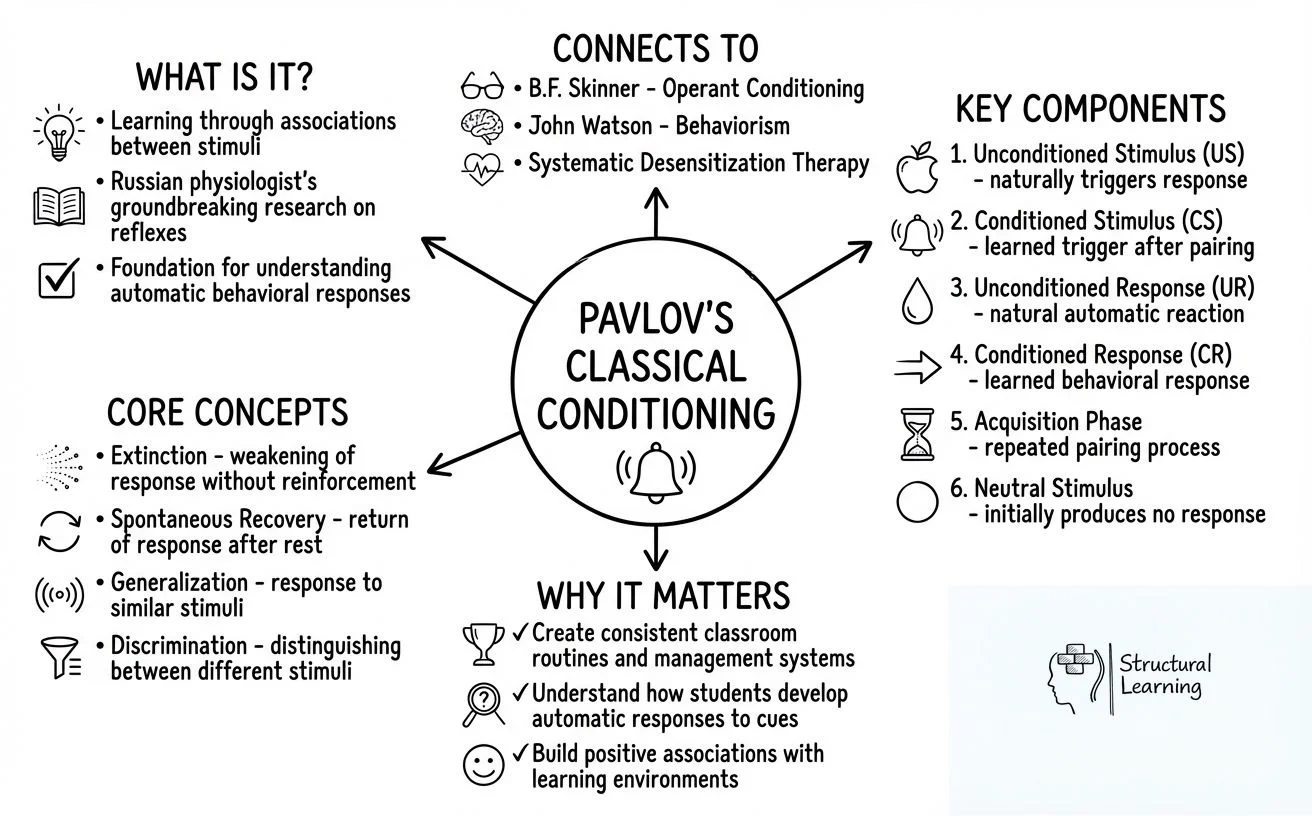

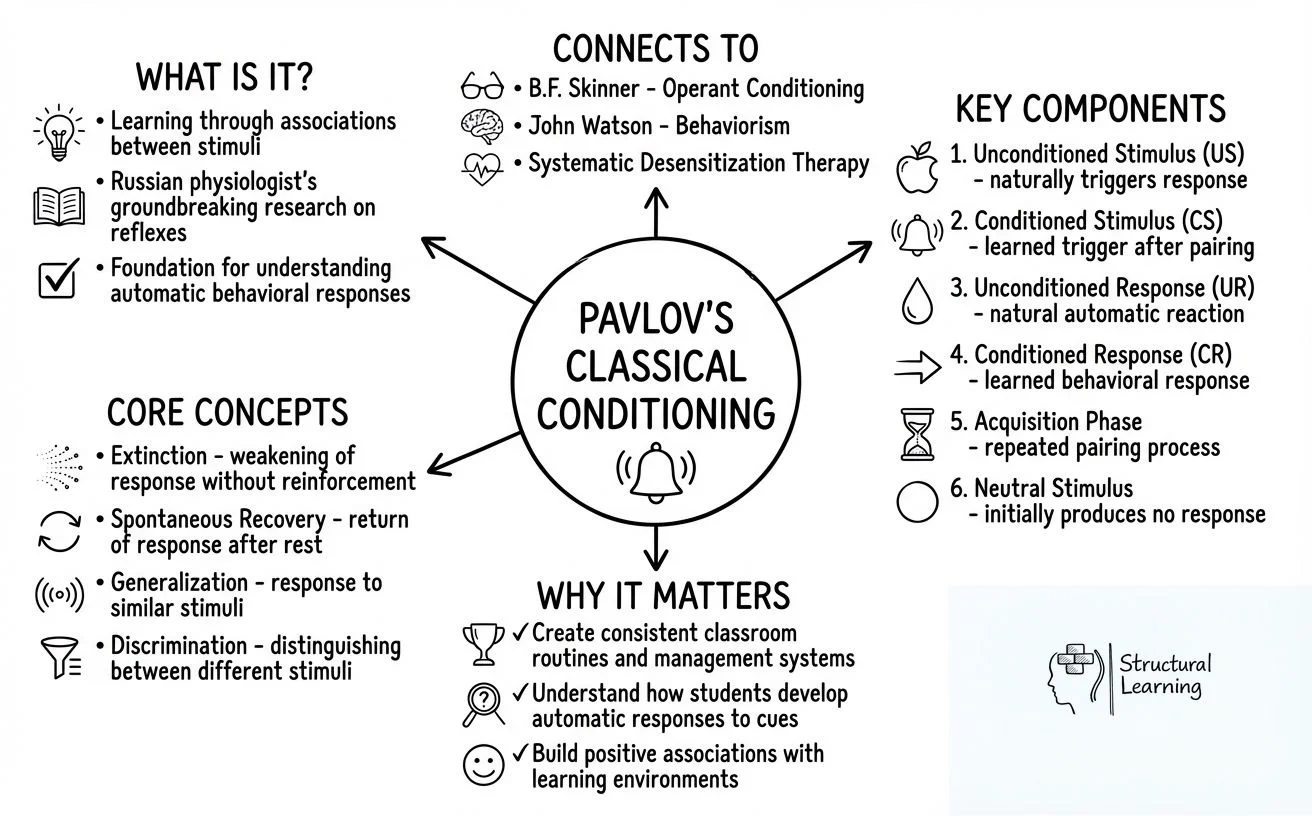

The four components of classical conditioning are the unconditioned stimulus (naturally triggers response), unconditioned response (natural reaction), conditioned stimulus (learned trigger), and conditioned response (learned reaction). These elements work together to create associative learning patterns in Pavlov's theoretical framework.

The four components are the unconditioned stimulus (US) which naturally triggers a response, the unconditioned response (UR) which occurs naturally, the conditioned stimulus (CS) which is initially neutral, and the conditioned response (CR) which is learned. For example, food (US) naturally causes salivation (UR), while a bell (CS) paired with food eventually causes salivation (CR) on its own. These components work together to create new learned associations between stimuli and responses.

To grasp the intricacies of classical conditioning, understand its key components: the unconditioned stimulus (US), the conditioned stimulus (CS), and the conditioned response (CR). These components form the building blocks of Pavlov's influential theory, illuminating the mechanisms by which organisms learn through associations between stimuli.

The unconditioned stimulus (US) refers to a stimulus that naturally and automatically triggers a response without prior conditioning. In Pavlov's experiments, the US was typically a biologically significant stimulus, such as food, that elicited an unconditioned response (UR) from the subjects. The unconditioned response is an innate and reflexive reaction that occurs without any prior learning.

The conditioned stimulus (CS), on the other hand, begins as a neutral stimulus that doesn't elicit a particular response. However, through repeated pairings with the unconditioned stimulus, the neutral stimulus acquires the capacity to evoke a response. This learned association between the conditioned stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus is the foundation of classical conditioning.

When the conditioned stimulus reliably predicts the presentation of the unconditioned stimulus, it elicits a response similar to the unconditioned response. This acquired response is known as the conditioned response (CR).

The conditioned response is a learned reaction that occurs in anticipation of the conditioned stimulus, even in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus.

For example, imagine a dog experiment where a bell (CS) is repeatedly paired with the presentation of food (US). Initially, the bell doesn't elicit any particular response. However, through repeated pairings, the dog begins to associate the bell with the food.

Eventually, the dog starts to salivate (CR) in response to the bell alone, even when food isn't present. Understanding the components of classical conditioning enables us to comprehend the intricate process of learning through associations.

By recognising the roles of the unconditioned stimulus, conditioned stimulus, and conditioned response, students gain insights into how new behaviours and responses are acquired and shaped through conditioning. These components serve as fundamental pillars in the study of classical conditioning and provide a solid foundation for further exploration into the complexities of learning and behaviour.

Extinction in classical conditioning occurs when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus, causing the conditioned response to weaken and eventually disappear. This process demonstrates that learned associations can be unlearned through lack of reinforcement.

Extinction in classical conditioning occurs when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus, causing the conditioned response to gradually weaken and disappear. However, spontaneous recovery can occur when the conditioned response suddenly reappears after a rest period, even without further conditioning. This shows that extinction doesn't completely erase the learned association but rather suppresses it temporarily.

In the field of classical conditioning, two important phenomena shed light on the dynamics of learning and behaviour: extinction and spontaneous recovery. Understanding these components enhances our comprehension of how conditioned responses can be weakened and potentially reappear over time.

Extinction occurs when a conditioned response gradually diminishes and ultimately disappears due to the absence of the unconditioned stimulus. In other words, when the conditioned stimulus (CS) is repeatedly presented without being followed by the unconditioned stimulus (US), the learned association weakens, and the conditioned response (CR) gradually fades away.

This process of extinction reveals the mutable nature of conditioned responses, indicating that they aren't permanent but can be subject to change and eventual disappearance.

However, even after extinction has occurred, there remains the possibility of spontaneous recovery.

Spontaneous recovery refers to the reappearance of a previously extinguished conditioned response, albeit at a weaker magnitude, following a period of rest or time delay. This phenomenon suggests that the learned association, though weakened, isn't entirely erased but rather lies dormant.

It implies that the original connection between the conditioned stimulus and the conditioned response can be reactivated under certain circumstances.

Exploring the dynamics of extinction and spontaneous recovery within classical conditioning reveals the intricate nature of learning and behaviour. These phenomena demonstrate that conditioned responses are subject to change and that the process of acquiring and modifying associations is dynamic and ongoing.

By recognising that conditioned responses can be weakened through extinction but may resurface through spontaneous recovery, we gain valuable insights into the intricacies of learning processes and the adaptive nature of behaviour.

The exploration of these dynamics expands our understanding of classical conditioning and its implications in various real-world scenarios.

Generalisation occurs when organisms respond to stimuli similar to the conditioned stimulus, whilst discrimination involves distinguishing between different stimuli and responding only to specific ones. These opposing processes determine how broadly or narrowly conditioned responses are applied in classical conditioning.

Generalization occurs when similar stimuli to the conditioned stimulus also trigger the conditioned response, like a dog salivating to different bell tones. Discrimination happens when the organism learns to respond only to the specific conditioned stimulus and not to similar ones, showing refined learning. These processes help organisms adapt by either broadening or narrowing their responses based on environmental cues.

In the intricate domain of classical conditioning, two key concepts, generalisation and discrimination, play a crucial role in understanding the boundaries of learned responses. These components shed light on the delicate balance between expanding conditioned responses to similar stimuli and differentiating between specific stimuli.

Generalisation occurs when a conditioned response, initially elicited by a specific conditioned stimulus (CS), is also produced in the presence of similar stimuli that share certain features with the original CS. This generalisation occurs because the organism has learned to associate the original CS with the unconditioned stimulus (US) and subsequently transfers that association to similar stimuli.

The broader the generalisation, the more similar the stimuli are perceived to be by the organism. Generalisation allows for adaptive behaviour, as it enables the transfer of learned responses to novel situations.

On the other hand, discrimination involves the ability to differentiate between stimuli and respond selectively to a specific conditioned stimulus. Discrimination occurs when an organism learns to respond to one particular stimulus while withholding the response in the presence of other stimuli that differ in some way. Discrimination reflects the ability to detect subtle differences in stimuli and respond in a targeted manner.

Understanding the fine line between generalisation and discrimination is crucial in Pavlovian conditioning. While generalisation allows for flexibility in responding to similar stimuli, discrimination helps organisms refine their responses and respond selectively to specific cues. Striking the right balance between generalisation and discrimination is vital for adaptive behaviour and efficient learning.

Anyone studying psychology can benefit from comprehending the components of generalisation and discrimination within classical conditioning. By understanding how organisms generalise responses to similar stimuli and discriminate between different stimuli, students gain insights into the complexities of Pavlovian conditioning.

These components illuminate the delicate dynamics of learning and behaviour, highlighting the nuanced interplay between broadening associations and honing selective responses. The exploration of this fine line contributes to our understanding of how organisms navigate their environments and adapt to varying stimuli.

Classical conditioning is used in systematic desensitization to treat phobias by gradually pairing relaxation with feared stimuli until the fear response is reduced. Aversion therapy uses conditioning to create negative associations with unwanted behaviours like addiction by pairing them with unpleasant stimuli. These therapeutic applications help modify problematic behaviours and emotional responses through controlled conditioning processes.

The components of classical conditioning extend beyond theoretical constructs, finding practical applications in various domains, both within the field of psychology and beyond. Pavlov's groundbreaking theory has sparked effective ideas and applications that have permeated numerous fields, making it a cornerstone of scientific understanding and practical implementation.

In the field of psychology, classical conditioning has been utilised in therapeutic interventions. Through a process known as systematic desensitisation, individuals with phobias or anxiety disorders can gradually overcome their fears.

This therapeutic approach involves exposing individuals to a hierarchy of fear-inducing stimuli while simultaneously engaging in relaxation techniques. By pairing the feared stimuli with a state of relaxation, a new conditioned response can be formed, leading to reduced anxiety or phobic reactions.

Marketing and advertising professionals have also capitalised on classical conditioning principles. By pairing products or brands with positive stimuli, such as attractive models, captivating music, or appealing environments, they aim to create positive associations and elicit desirable responses from consumers.

This strategic use of classical conditioning can shape consumers' preferences, increase brand recognition, and influence purchasing decisions.

Furthermore, classical conditioning has found applications in education. Teachers employ various techniques to facilitate learning by creating associations between neutral stimuli and meaningful content. For instance, using mnemonic devices, such as acronyms or vivid imagery, can aid in memory retention and recall. These techniques use the power of conditioning to enhance learning outcomes and promote knowledge acquisition.

Beyond psychology, classical conditioning principles have permeated diverse fields, including animal training, sports, and even politics. Animal trainers use conditioning techniques to teach animals new behaviours or modify existing ones. In sports, coaches employ conditioning methods to associate specific stimuli, such as a whistle or a particular gesture, with desired athlete responses.

Politicians often use classical conditioning strategies to associate themselves with positive stimuli, such as patriotic symbols or memorable slogans, aiming to evoke favourable responses from voters.

Understanding the practical applications of Pavlov's theory in psychology and beyond helps students to appreciate the wide-ranging impact of classical conditioning. By recognising how this theory is utilised in therapeutic settings, marketing strategies, educational approaches, and various other domains, students gain a complete understanding of the relevance and versatility of classical conditioning principles.

This knowledge equips them to critically analyse and apply these concepts in real-world scenarios, paving the way for effective problem-solving and further advancements in multiple fields.

Pavlov's theory faces criticism for oversimplifying human behaviour, focusing primarily on reflexive responses rather than cognitive processes. Critics argue that classical conditioning cannot fully explain complex learning, voluntary behaviour, or individual differences in learning capacity and motivation.

Critics argue that classical conditioning oversimplifies learning by focusing only on observable behaviours while ignoring cognitive processes and individual differences. The theory also cannot fully explain complex human behaviours, voluntary actions, or the role of consciousness in learning. Modern perspectives incorporate cognitive and biological factors, recognising that learning involves more than simple stimulus-response associations.

While Pavlov's theory of classical conditioning has made significant contributions to the field of psychology, it isn't without its fair share of criticisms and evolving perspectives. As with any scientific theory, critical evaluation and ongoing research have prompted the emergence of alternative viewpoints and refinements to the original framework.

One criticism directed at Pavlov's theory pertains to its emphasis on the passive nature of the organism in the learning process. Some argue that classical conditioning overlooks the active role of cognitive processes, such as attention, memory, and expectation, in shaping behaviour.

Contemporary perspectives, such as cognitive-behavioural approaches, highlight the interplay between cognitive factors and conditioning processes, providing a more comprehensive understanding of how learning occurs.

Another criticism revolves around the generalisability of classical conditioning principles across different species and contexts. Critics argue that animals and humans may exhibit unique learning patterns and preferences that can't be entirely explained by Pavlov's theory.

The study of individual differences and cultural influences has shed light on the complexities of learning and behaviour, challenging the notion of a one-size-fits-all approach to conditioning.

Furthermore, contemporary perspectives have expanded upon Pavlov's theory by introducing concepts such as higher-order conditioning and biological constraints.

Higher-order conditioning refers to the process where a conditioned stimulus becomes associated with a new neutral stimulus, further expanding the range of stimuli that can elicit conditioned responses. Biological constraints emphasise the idea that certain associations are more easily formed due to inherent predispositions or limitations imposed by an organism's biology.

recognise that scientific theories, including Pavlov's, are subject to scrutiny and revision. By acknowledging criticisms and considering contemporary perspectives, we can develop a more nuanced understanding of the strengths and limitations of classical conditioning as a framework for explaining learning and behaviour.

This critical evaluation encourages further exploration and the development of new theories that encompass a broader range of factors and account for the complexities inherent in the study of psychology.

Pavlov's theory remains important because it provides foundational understanding of associative learning used in therapy, education, and behavioural modification. Modern applications include treating phobias, developing teaching methods, and understanding consumer behaviour patterns across multiple disciplines.

Pavlov's theory remains crucial because it explains fundamental learning processes that apply to education, therapy, marketing, and everyday behaviour modification. The principles of classical conditioning help therapists treat phobias and addictions, educators design effective teaching strategies, and marketers create brand associations. Understanding these basic learning mechanisms provides insights into both adaptive and maladaptive behaviours across all areas of human experience.

Q1: Who is Ivan Pavlov?

Ivan Pavlov was a renowned Russian psychologist who made significant contributions to the field of psychology through his work on conditioned reflexes.

Q2: What are conditioned reflexes?

Conditioned reflexes are learned responses. Pavlov demonstrated through his experiments that these responses are developed when a neutral stimulus is consistently paired with a stimulus that naturally triggers a response.

Q3: What is an unconditioned reflex?

An unconditioned reflex is a natural, automatic response to a stimulus. In Pavlov's experiments, the unconditioned reflex was the dogs' salivation in response to the sight or smell of food.

Q4: How do emotional responses fit into Pavlov's theory?

Pavlov's theory suggests that emotional responses can also be conditioned. This means that our emotional reactions to certain stimuli can be shaped and influenced by our past experiences and associations.

Q5: Can you explain the classical conditioning process?

The classical conditioning process, as described by Pavlov, involves pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus that naturally triggers a response. Over time, the neutral stimulus alone can trigger the same response. This was demonstrated in Pavlov's experiments with dogs, where the sound of a bell (neutral stimulus) was paired with the presentation of food (unconditioned stimulus). Eventually, the dogs began to salivate (response) just at the sound of the bell.

Q6: What was Pavlov's work on the digestive glands?

Pavlov's work on the digestive glands of dogs was what led him to his discovery of the conditioned reflex. He noticed that dogs would begin to salivate not only at the sight of food but also at the sight of the person who usually fed them. This observation formed the basis of his experiments on conditioned reflexes.

Q7: How did Pavlov demonstrate salivation in dogs?

Pavlov demonstrated salivation in dogs through a series of experiments where he paired the sound of a bell with the presentation of food. Over time, the dogs began to associate the bell with food and would start to salivate at the sound of the bell, even when no food was presented.

Pavlov's work established psychology as an experimental science and laid the foundation for behaviourism, influencing major psychologists like Watson and Skinner. His Nobel Prize in 1904 recognised the scientific rigor of his methods, which transformed psychology from philosophical speculation to empirical research. The principles he discovered continue to inform neuroscience, learning theory, and therapeutic practices worldwide.

Building on Pavlov's groundbreaking work on classical conditioning theory, a series of experiments that explored the association of stimuli with reflexive responses, several authors and areas of psychology have been influenced. Here's a seven-point list that highlights these influences:

1. John B. Watson:

Influence: Applied classical conditioning to human behaviour. Implication: Led to the development of Behaviourism, focusing on observable behaviours.

2. B.F. Skinner:

Influence: Extended conditioning principles to operant conditioning. Implication: Developed understanding of how consequences shape behaviour.

3. Joseph Wolpe:

Influence: Applied classical conditioning to therapy. Implication: Developed systematic desensitisation for treating phobias and anxiety.

4. Albert Bandura:

Influence: Integrated conditioning with observational learning. Implication: Developed social learning theory, expanding understanding of behaviour acquisition.

5. Robert Rescorla and Allan Wagner:

Influence: Refined understanding of conditioning mechanisms. Implication: Developed the Rescorla-Wagner model explaining associative learning.

6. John Garcia:

Influence: Discovered biological constraints on conditioning. Implication: Demonstrated that some associations are learned more easily than others due to evolutionary factors.

7. Contemporary Neuroscience:

Influence: Explores the neural basis of conditioning. Implication: Identifies brain regions and mechanisms underlying associative learning.

Essential readings include Pavlov's original work 'Conditioned Reflexes' and modern textbooks on learning psychology that expand on his theories. Academic journals in behavioural neuroscience and learning psychology regularly publish research applying and extending Pavlovian principles. Online courses and university psychology programs offer comprehensive coverage of classical conditioning within broader learning theory contexts.

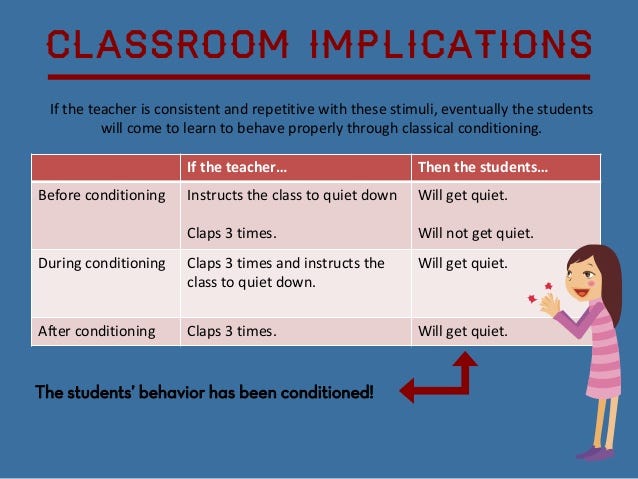

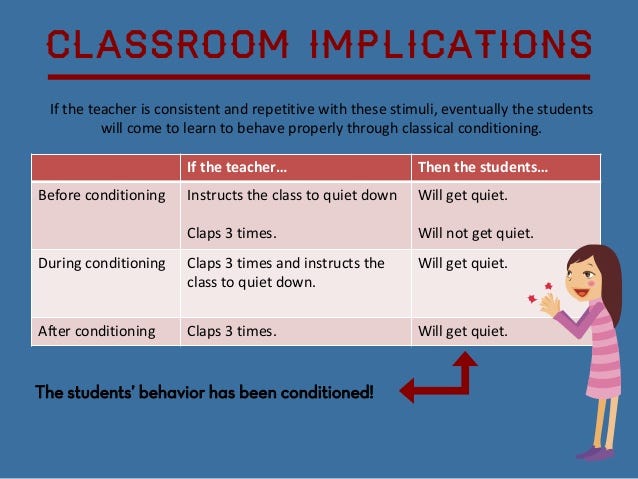

Classical conditioning is Ivan Pavlov's theory that demonstrates how organisms learn through associations between stimuli, where a neutral stimulus becomes paired with an unconditioned stimulus to produce a conditioned response. In the classroom, this means teachers can pair routine cues like bells or music with positive experiences, so students eventually respond automatically to these signals for behaviour managementand transitions.

Teachers should consistently pair classroom routines and cues with positive experiences during the acquisition phase, such as using specific sounds or visual signals alongside enjoyable activities or praise. Maintain consistency to prevent extinction of established routines, and teachers should choose clear, distinct cues that students can easily differentiate between different contexts.

The essential components include the unconditioned stimulus (natural motivators like praise), unconditioned response (students' natural reactions), neutral stimulus (classroom cues before conditioning), and the resulting conditioned stimulus and response after successful pairing. Educators should also understand phenomena like extinction, spontaneous recovery, generalisation, and discrimination to effectively manage learned behaviours over time.

Teachers can establish automatic student responses to classroom management signals, making transitions smoother and reducing disruptions. Students will naturally generalise these learned behaviours across different contexts, and teachers can use established positive associations to create a more conducive learning environment with less conscious effort required for behaviour management.

The main challenge is extinction, where conditioned responses weaken if cues are presented without the positive reinforcement, so teachers must maintain consistency in their approach. Additionally, spontaneous recovery means that old, unwanted behaviours may resurface after breaks or holidays, requiring teachers to be prepared to re-establish positive associations and routines.

A common example is pairing a specific piece of music with enjoyable group activities until students automatically feel positive and cooperative when they hear that music. Another example is consistently using a particular bell sound before rewarding activities, so eventually the bell alone creates anticipation and improved attention from students, even without the reward immediately following.

Parents can reinforce the same cues and signals used in school by maintaining consistent routines and positive associations with learning activities at home. They should be aware of generalisation, where children may apply classroom-conditioned responses in the home environment, and support this by using similar positive reinforcement strategies for homework and study time.

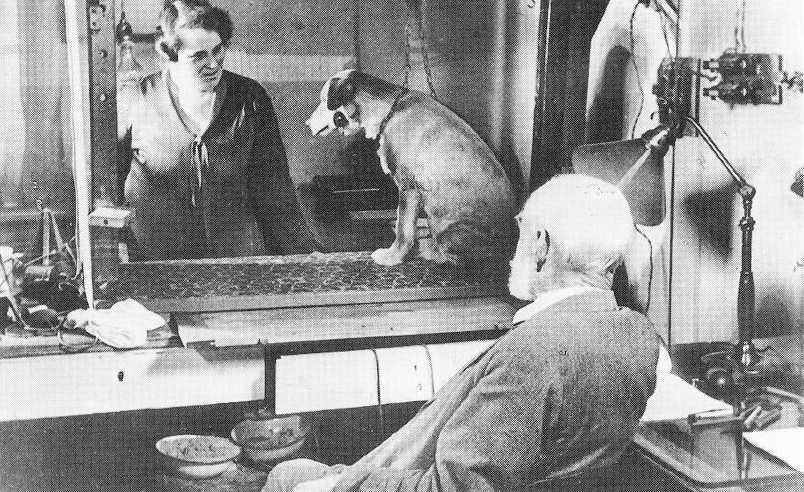

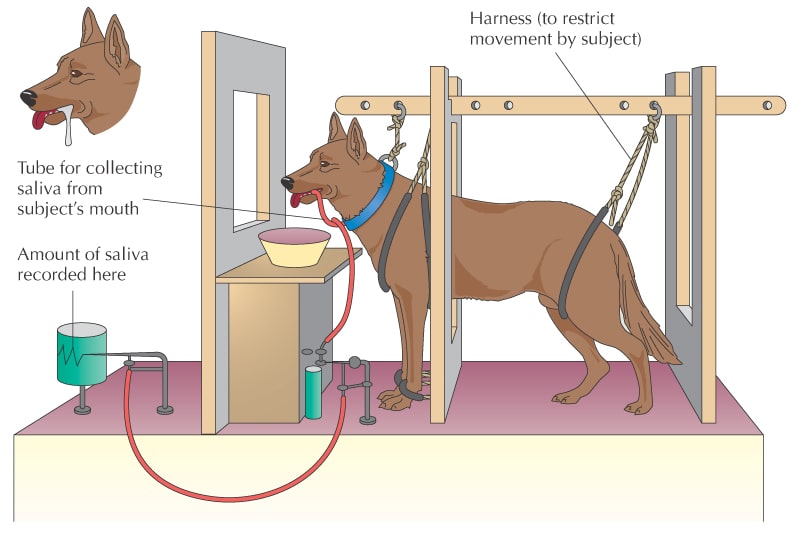

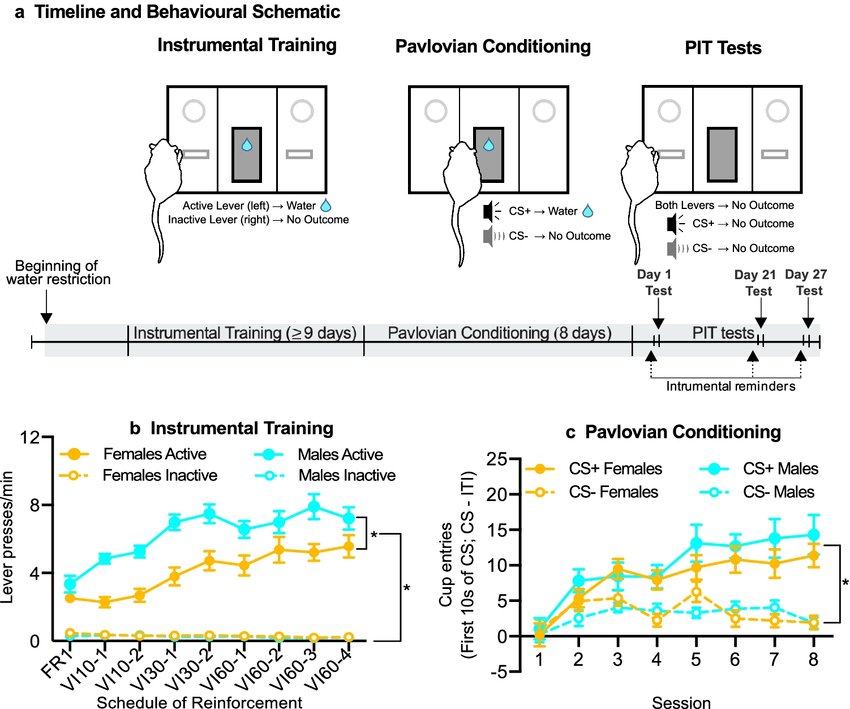

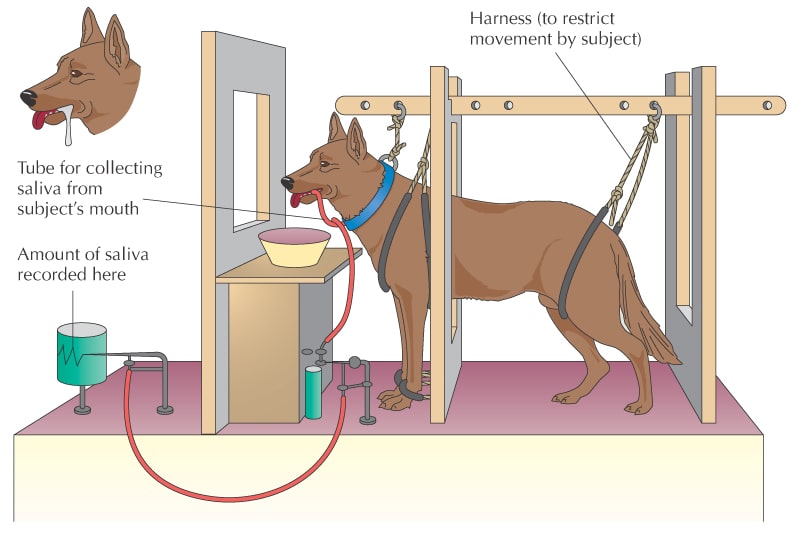

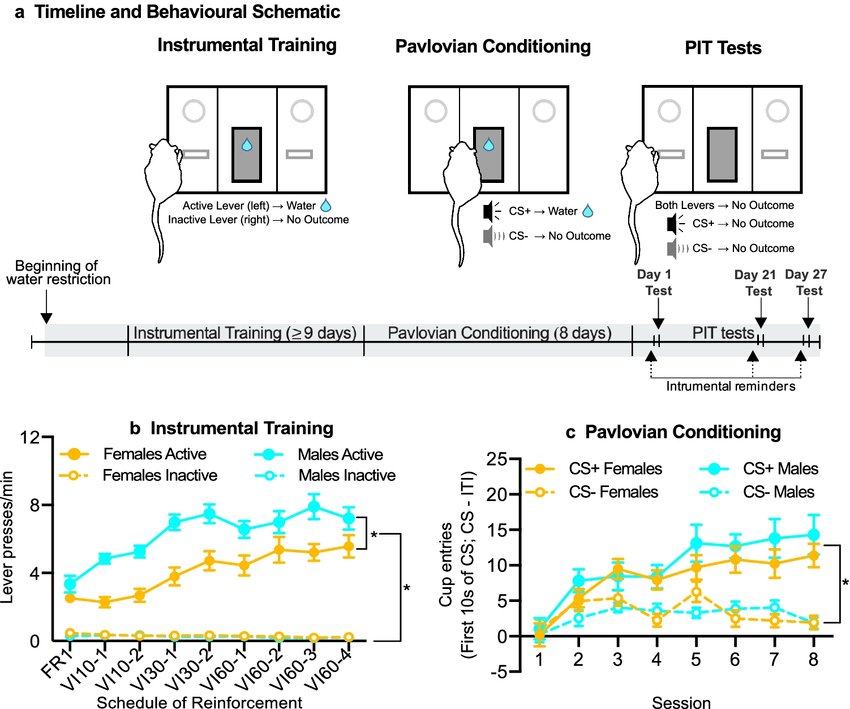

Whilst studying digestive processes in dogs at the Imperial Institute of Experimental Medicine in St Petersburg, Ivan Pavlov noticed something peculiar: his laboratory dogs began salivating before food reached their mouths, triggered merely by the sound of approaching footsteps. This observation in the 1890s sparked a series of systematic experiments that would transform our understanding of learningand behaviour. Pavlov's laboratory, described by historian Daniel Todes as a "physiology factory", employed over 100 researchers who conducted thousands of trials with surgical precision, transforming a chance observation into one of psychology's most fundamental theories.

The experimental procedure involved surgically implanting a fistula in each dog's cheek to collect and measure saliva output precisely. Pavlov then introduced a metronome (not a bell, as commonly misreported) that clicked at specific intervals. Initially, this neutral stimulus produced no salivation. However, when Pavlov repeatedly paired the metronome's clicking with the presentation of meat powder, the dogs began associating the two stimuli. After multiple pairings, typically 20 to 40 trials, the metronome alone triggered salivation, demonstrating that a previously meaningless stimulus could acquire the power to elicit a physiological response through association.

Pavlov's experiments revealed complexities beyond simple stimulus-response connections. He discovered that dogs could learn temporal conditioning, salivating at regular intervals when food was presented every 30 minutes, even without external cues. His team also documented "experimental neurosis" when dogs were forced to discriminate between increasingly similar stimuli, such as a circle (paired with food) and an ellipse (no food). As the ellipse became more circular, dogs exhibited signs of distress, barking, trembling, and refusing to participate, revealing the psychological strain of impossible discrimination tasks.

Recent neuroscience research has validated Pavlov's observations at the cellular level. Bichler and colleagues demonstrated Pavlovian conditioning using organic transistors that mimic synaptic behaviour, showing that the association between stimuli creates measurable changes in synaptic strength, just as Pavlov hypothesised over a century ago. This biological basis explains why conditioned responses persist: they represent actual physical changes in neural pathways.

For educators, understanding Pavlov's complete methodology offers crucial insights. Just as Pavlov's dogs developed "experimental neurosis" from conflicting signals, students can experience anxiety when classroom cues are inconsistent or contradictory. Teachers should ensure that their conditioned stimuli, whether a specific hand signal for silence or a musical cue for transitions, remain distinct and unambiguous. Additionally, Pavlov's discovery of temporal conditioning suggests that maintaining consistent lesson timing can help students automatically prepare for transitions, reducing the need for explicit cues and creating a more fluid learning environment.

While Pavlov's classical conditioning explains how we learn through stimulus associations, B.F. Skinner's operant conditioning reveals how consequences shape voluntary behaviours. Understanding both theories provides educators with a comprehensive toolkit for classroom management and student learning. Recent research by Orbán (2025) emphasises that these two forms of associative learning, though distinct in their mechanisms, often work together in real-world educational settings to create complex learning patterns.

Classical conditioning involves involuntary, reflexive responses to paired stimuli, where learning occurs before the behaviour. A student automatically feeling anxious when entering a maths classroom after repeated negative experiences exemplifies this process. In contrast, operant conditioning deals with voluntary behaviours modified by their consequences, where learning happens after the behaviour. When a student raises their hand more frequently because the teacher consistently praises participation, operant conditioning is at work. The timing difference is crucial: classical conditioning creates associations between stimuli that predict outcomes, whilst operant conditioning strengthens or weakens behaviours based on what happens afterwards.

Research by Garren et al. (2013) found that circadian rhythms affect these two types of learning differently, suggesting that classical conditioning may be more robust during morning hours whilst operant conditioning shows less time-of-day variation. This finding has practical implications for lesson planning. Teachers might schedule activities requiring emotional associations or automatic responses, such as memorising multiplication tables through rhythmic chanting, during morning sessions. Meanwhile, behaviour modification strategies using rewards and consequences can be effectively implemented throughout the day.

The neural mechanisms also differ significantly. Cataldi et al. (2024) demonstrated that whilst classical conditioning primarily involves subcortical structures processing automatic responses, operant conditioning engages striatal pathways associated with goal-directed actions. This distinction helps explain why classically conditioned responses, like a student's automatic anxiety response to tests, can be harder to modify than operantly learned behaviours, such as homework completion habits. Teachers can use this knowledge by using classical conditioning to establish positive emotional associations with learning environments through consistent pairing of classroom spaces with enjoyable activities, whilst simultaneously employing operant conditioning principles through structured reward systems for academic behaviours.

In practice, successful classroom managementoften requires combining both approaches. A teacher might use classical conditioning by consistently playing calming music (neutral stimulus) during enjoyable reading time (unconditioned stimulus) until the music alone creates a relaxed learning state. Simultaneously, they employ operant conditioning by providing immediate positive feedback for on-task behaviour, increasing the likelihood of future engagement. Understanding when to apply each type of conditioning, recognising their different strengths, and knowing how they interact enables educators to create more effective learning environments that address both emotional responses and voluntary behaviours.

Whilst Pavlov's classical conditioning emerged from laboratory experiments with dogs, its principles have profoundly shaped modern therapeutic practices. Clinical psychologists routinely apply conditioning principles to treat phobias, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress through systematic desensitisation and exposure therapy. These treatments work by gradually pairing feared stimuli with relaxation responses, essentially reconditioning the patient's automatic reactions. For educators, understanding these therapeutic applications provides valuable insights into managing classroom anxiety and creating positive learning associations.

Recent technological advances have expanded conditioning-based therapies beyond traditional clinical settings. Research by Koffel et al. (2018) demonstrated how mobile applications can deliver cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), showing that conditioned sleep associations can be effectively modified through digital platforms. Similarly, Craig et al. (2021) found that telehealth adaptations of affirmative cognitive-behavioural therapy successfully addressed anxiety and depression in LGBTQ+ youth, proving that conditioning principles translate effectively to virtual environments. These findings suggest that educators can use digital tools to reinforce positive classroom behaviours and emotional associations, even in remote learning contexts.

Teachers can adopt several evidence-based techniques from behavioural therapy to address common classroom challenges. For students with test anxiety, progressive muscle relaxation paired with exam-related stimuli can reduce physiological stress responses, mirroring clinical anxiety treatments. The systematic approach used in exposure therapy, where patients gradually confront feared stimuli in controlled doses, translates directly to helping students overcome presentation anxiety or maths phobia through incremental practice sessions paired with supportive feedback.

Friedberg et al. (2012) highlighted how lifestyle-oriented interventions for chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia incorporate conditioning principles to establish healthy behavioural patterns. This approach offers valuable lessons for classroom management: teachers can create "behavioural chains" where positive activities become conditioned stimuli for subsequent learning tasks. For instance, a brief mindfulness exercise (initially paired with a reward) can become a conditioned stimulus that automatically triggers focused attention, similar to how therapeutic interventions establish new pain management responses. By understanding how therapists use classical conditioning to modify deeply ingrained responses, educators gain powerful tools for addressing learning barriers, emotional regulation challenges, and establishing classroom environmentswhere positive associations enhance academic achievement.

Classical conditioning principles extend far beyond the classroom into clinical settings, where they form the foundation of numerous therapeutic interventions. Modern behavioural therapy uses Pavlovian concepts to treat anxiety disorders, phobias, and maladaptive behaviours through systematic desensitisation and exposure therapy. The mechanism works by gradually re-associating feared stimuli with neutral or positive responses, effectively rewiring the conditioned fear response that patients have developed.

Recent technological advances have transformed how these classical conditioning principles are applied therapeutically. Research by Koffel et al. (2018) demonstrated the effectiveness of mobile applications in delivering cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia, showing how conditioned sleep associations can be modified through consistent digital interventions. Similarly, Friedberg et al. (2012) found that home-based technologies could successfully implement conditioning-based treatments for fibromyalgia patients, using repeated pairings of relaxation techniques with pain management strategies to create new, healthier conditioned responses to pain triggers.

Educators can adapt these clinical applications to address classroom challenges, particularly for students with anxiety or behavioural difficulties. For instance, systematic desensitisation techniques can help students overcome test anxiety by gradually pairing examination environments with relaxation exercises and positive experiences. Teachers might start by having students practise breathing exercises whilst sitting at their desks, then progress to doing these exercises whilst looking at blank test papers, eventually building up to mock exam conditions whilst maintaining the conditioned calm response.

The telehealth revolution has particular relevance for modern educational settings. Craig et al. (2021) highlighted how affirmative cognitive behavioural therapy techniques adapted for online delivery proved especially effective with marginalised youth populations. This research suggests that classical conditioning principles can be successfully implemented in hybrid or remote learning environments, where teachers can establish conditioned responses through consistent virtual cues, such as specific background music for focused work time or visual signals for transitioning between activities. These digital conditioning tools become particularly valuable for supporting students who may struggle with traditional classroom management approaches, offering alternative pathways to establishing productive learning behaviours through carefully designed stimulus-response pairings that transcend physical classroom boundaries.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Implementation of The Classical Conditioning in PAI Learning

5 citations

Baharuddin Baharuddin & S. Suyadi (2020)

This study examines how an Indonesian high school applies Pavlov's classical conditioning theory to teach Islamic education. Teachers can learn from this case study how behaviourist principles can be adapted to religious education contexts, including what environmental and institutional factors support or hinder this approach in real classrooms.

Implementasi Classical Conditioning dalam Pembelajaran PAI

3 citations

Baharuddin Baharuddin (2020)

This research investigates the use of classical conditioning techniques in Islamic religious education at a school in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Teachers interested in behaviourist approaches will find practical examples of how stimulus-response learning can be implemented in faith-based education settings, along with insights into the contextual factors that affect success.

The Application of Classical Conditioning Theory in Elementary Education

1 citations

Mengqi Xiong (2024)

This paper explores how classical conditioning can improve teaching quality and help elementary students in China develop good learning habits. Teachers working with young learners will find relevant strategies for using behaviourist principles to build foundational skills and promote positive academic development during the critical early years of compulsory education.

Dwi Novita Sari et al. (2025)

This classroom action research demonstrates how cooperative learning using the Student Team Achievement Divisions model improved achievement among accounting students at an Indonesian vocational school. Teachers can gain practical insights into implementing team-based learning strategies that have been tested and refined through action research in a real classroom setting.

Online Collaborative Learning to Enhance Educational Outcomes of English Language Courses

Iwona Mokwa-Tarnowska (2020)

This paper discusses how behaviourist principles can guide the design of online and blended English language courses for university students. Teachers moving to digital or hybrid instruction will find useful connections between traditional behaviourist theory and modern collaborative online tools, helping them structure effective e-learning experiences.

| Component/Phase | Timing | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditioned Stimulus (US) | Pre-existing | Naturally triggers a response without prior learning (e.g., food causing salivation) | Identify natural motivators like praise, rewards, or enjoyable activities |

| Unconditioned Response (UR) | Pre-existing | Natural, automatic response to the unconditioned stimulus | Recognize students' natural responses to build upon them |

| Neutral Stimulus | Before conditioning | Does not initially trigger the desired response (e.g., bell sound) | Choose classroom cues like bells, music, or visual signals |

| Acquisition Phase | During conditioning | Repeated pairing of neutral stimulus with unconditioned stimulus | Consistently pair classroom routines with positive experiences |

| Conditioned Stimulus (CS) | After conditioning | Former neutral stimulus now triggers response alone | Use established cues to manage transitions and behaviours |

| Conditioned Response (CR) | After conditioning | Learned response to the conditioned stimulus | Students respond automatically to classroom management signals |

| Extinction | Variable | Gradual weakening of conditioned response when CS presented without US | Maintain consistency to prevent loss of established routines |

| Spontaneous Recovery | After extinction | Return of conditioned response after a rest period | Be aware that old behaviours may resurface after breaks |

| Generalization | Post-conditioning | Response occurs to stimuli similar to the conditioned stimulus | Students may apply learned behaviours across different contexts |

| Discrimination | Post-conditioning | Ability to distinguish between similar stimuli | Teach students to differentiate between specific classroom cues |

Ivan Pavlov, a prominent figure in the field of psychology, introduced a theory that transformed our understanding of . Should use present tense without specific year reference, or use the current year to how we understand human and animal learning processes. Born in 1849 in Russia, Pavlov initially pursued a career in medicine before turning his attention to the fascinating . He's widely recognised for his groundbreaking research on classical conditioning, which has left an indelible mark on the field.

Pavlov's theory, often referred to as Pavlovian conditioning, centres around the concept of associative learning. He sought to explore how organisms, including humans, and responses through repeated associations between stimuli.

His experiments primarily involved dogs, but the principles he discovered have far-reaching implications for as well.

Classical conditioning, the foundation of Pavlov's theory, involves pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus to elicit a conditioned response. In one of his famous experiments, Pavlov observed that dogs naturally salivated when presented with food, an unconditioned stimulus. However, through repeated pairings of a neutral stimulus, such as a bell, with the food, the dogs eventually began to associate the bell with the arrival of food.

As a result, they started salivating at the sound of the bell alone, even in the absence of the food. This conditioned response demonstrated the formation of a new association between the neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus.

Pavlov's research on classical conditioning shed light on the underlying mechanisms of learning and provided a framework to understand how environmental stimuli can and responses. This theory has implications not only in psychology but also in various fields, including education, marketing, and therapy.

Contemporary perspectives have expanded upon his work, acknowledging the and individual . Nonetheless, Pavlov's contributions remain foundational to the study of learning and behaviour, and his theory continues to be an integral part of the curriculum for most students studying psychology. By understanding the basics of Pavlov's theory, we can examine deeper into the intricate workings of human and animal behaviour and gain valuable insights into the complex nature of our .

"Should include a relevant quote about classical conditioning with proper citation, or remove the quote.", Ivan Pavlov

Classical conditioning works by pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus repeatedly until the neutral stimulus alone triggers a response. The process creates learned associations between environmental cues and automatic responses. This learning mechanism forms the foundation of Pavlov's behavioural theory.

Classical conditioning works by repeatedly pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus until the neutral stimulus alone triggers the desired response. The process involves presenting a stimulus that naturally causes a response (like food causing salivation) alongside a neutral stimulus (like a bell sound) until the neutral stimulus alone produces the response. This learning occurs automatically without conscious effort and forms the basis for many learned behaviours and emotional responses.

Classical conditioning stands as the bedrock of Pavlov's pioneering theory, which has profoundly impacted the field of psychology. This fundamental concept revolves around the process of learning through associations between stimuli, shedding light on how organisms, including humans, acquire new behaviours and responses. Pavlov's extensive research on classical conditioning, often referred to as Pavlovian conditioning, has left an indelible mark on our understanding of human and animal behaviour.

At its core, classical conditioning involves pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus to elicit a conditioned response. To comprehend this process, consider one of Pavlov's notable experiments with dogs. He observed that dogs naturally salivated in response to food, an unconditioned stimulus.

However, through repeated pairings of a , such as the sound of a bell, with the presentation of food, the dogs began to associate the bell with the imminent arrival of food. Consequently, they developed a conditioned response, salivating at the mere sound of the bell, even in the absence of the food itself. This conditioned response demonstrated the formation of a new association between the initially neutral stimulus (the bell) and the unconditioned stimulus (the food).

Classical conditioning, as established by Pavlov, reveals the profound influence of environmental stimuli on our behaviours and responses. The theory's significance extends beyond the , permeating diverse fields such as education, marketing, and therapy. By understanding the foundations of classical conditioning, we can gain valuable insights into the intricate processes that underlie learning and behaviour.

It's worth noting that while Pavlov's theory of classical conditioning has made remarkable contributions to psychology, it isn't without its critiques and limitations. Contemporary perspectives have further expanded upon his work, emphasising the role of cognitive processes and individual differences in conditioning.

Nonetheless, the core principles of classical conditioning remain pivotal to the study of human and animal behaviour, serving as a crucial component of most psychology curricula. By grasping the essence of classical conditioning, students embark on a journey of comprehension, enabling them to unravel the complexities of learning processes and uncover the profound mechanisms that shape our behaviours and responses.

Pavlov's dog experiment demonstrated that dogs naturally salivated when presented with food, then learned to salivate when hearing a bell after repeated pairings. The bell became a conditioned stimulus that triggered salivation without food present. This experiment established the principles of classical conditioning.

In Pavlov's dog experiment, he rang a bell before feeding dogs, and after repeated pairings, the dogs began salivating at the sound of the bell alone. The experiment demonstrated that dogs could learn to associate the neutral stimulus (bell) with food, producing a conditioned response (salivation) even without food present. This groundbreaking study provided the first scientific evidence of how learning through association works in living organisms.

One of the pivotal experiments that laid the foundation for classical conditioning was conducted by a renowned researcher in the field of psychology. This groundbreaking study, often cited as a quintessential example of classical conditioning, revealed key insights into how organisms learn through associations between stimuli. The experiment involved dogs as the subjects, and its findings shed light on the fundamental principles that underpin Pavlov's theory.

In this seminal experiment, the researcher presented a neutral stimulus, such as the sound of a bell, to the dogs and simultaneously introduced an unconditioned stimulus, food. Naturally, the dogs responded by salivating in the presence of the food, a response known as the unconditioned response.

Through repeated pairings of the bell and the food, the researcher aimed to establish an association between the two stimuli.

Over time, a remarkable transformation occurred. The dogs began to associate the bell, initially a neutral stimulus, with the imminent arrival of food. As a result, the sound of the bell alone started to evoke a response similar to the original salivation triggered by the food.

This learned response, known as the conditioned response, demonstrated the formation of an association between the previously neutral stimulus (the bell) and the unconditioned stimulus (the food).

Pavlov's experiment provided a clear illustration of classical conditioning in action. It showcased how a neutral stimulus can acquire the capacity to elicit a response through repeated pairings with a biologically significant stimulus.

The study highlighted the significance of temporal contiguity, the close proximity in time between the neutral and unconditioned stimuli, for successful conditioning to take place.

This experiment serves as a pivotal example of behavioural psychology, as it encapsulates the core principles of classical conditioning. By understanding the basics of Pavlov's experiment, students gain valuable insights into the intricate process of learning through associative associations. It paves the way for further exploration of the complexities of classical conditioning and its application in diverse areas of psychology.

The four components of classical conditioning are the unconditioned stimulus (naturally triggers response), unconditioned response (natural reaction), conditioned stimulus (learned trigger), and conditioned response (learned reaction). These elements work together to create associative learning patterns in Pavlov's theoretical framework.

The four components are the unconditioned stimulus (US) which naturally triggers a response, the unconditioned response (UR) which occurs naturally, the conditioned stimulus (CS) which is initially neutral, and the conditioned response (CR) which is learned. For example, food (US) naturally causes salivation (UR), while a bell (CS) paired with food eventually causes salivation (CR) on its own. These components work together to create new learned associations between stimuli and responses.

To grasp the intricacies of classical conditioning, understand its key components: the unconditioned stimulus (US), the conditioned stimulus (CS), and the conditioned response (CR). These components form the building blocks of Pavlov's influential theory, illuminating the mechanisms by which organisms learn through associations between stimuli.

The unconditioned stimulus (US) refers to a stimulus that naturally and automatically triggers a response without prior conditioning. In Pavlov's experiments, the US was typically a biologically significant stimulus, such as food, that elicited an unconditioned response (UR) from the subjects. The unconditioned response is an innate and reflexive reaction that occurs without any prior learning.

The conditioned stimulus (CS), on the other hand, begins as a neutral stimulus that doesn't elicit a particular response. However, through repeated pairings with the unconditioned stimulus, the neutral stimulus acquires the capacity to evoke a response. This learned association between the conditioned stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus is the foundation of classical conditioning.

When the conditioned stimulus reliably predicts the presentation of the unconditioned stimulus, it elicits a response similar to the unconditioned response. This acquired response is known as the conditioned response (CR).

The conditioned response is a learned reaction that occurs in anticipation of the conditioned stimulus, even in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus.

For example, imagine a dog experiment where a bell (CS) is repeatedly paired with the presentation of food (US). Initially, the bell doesn't elicit any particular response. However, through repeated pairings, the dog begins to associate the bell with the food.

Eventually, the dog starts to salivate (CR) in response to the bell alone, even when food isn't present. Understanding the components of classical conditioning enables us to comprehend the intricate process of learning through associations.

By recognising the roles of the unconditioned stimulus, conditioned stimulus, and conditioned response, students gain insights into how new behaviours and responses are acquired and shaped through conditioning. These components serve as fundamental pillars in the study of classical conditioning and provide a solid foundation for further exploration into the complexities of learning and behaviour.

Extinction in classical conditioning occurs when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus, causing the conditioned response to weaken and eventually disappear. This process demonstrates that learned associations can be unlearned through lack of reinforcement.

Extinction in classical conditioning occurs when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus, causing the conditioned response to gradually weaken and disappear. However, spontaneous recovery can occur when the conditioned response suddenly reappears after a rest period, even without further conditioning. This shows that extinction doesn't completely erase the learned association but rather suppresses it temporarily.

In the field of classical conditioning, two important phenomena shed light on the dynamics of learning and behaviour: extinction and spontaneous recovery. Understanding these components enhances our comprehension of how conditioned responses can be weakened and potentially reappear over time.

Extinction occurs when a conditioned response gradually diminishes and ultimately disappears due to the absence of the unconditioned stimulus. In other words, when the conditioned stimulus (CS) is repeatedly presented without being followed by the unconditioned stimulus (US), the learned association weakens, and the conditioned response (CR) gradually fades away.

This process of extinction reveals the mutable nature of conditioned responses, indicating that they aren't permanent but can be subject to change and eventual disappearance.

However, even after extinction has occurred, there remains the possibility of spontaneous recovery.

Spontaneous recovery refers to the reappearance of a previously extinguished conditioned response, albeit at a weaker magnitude, following a period of rest or time delay. This phenomenon suggests that the learned association, though weakened, isn't entirely erased but rather lies dormant.

It implies that the original connection between the conditioned stimulus and the conditioned response can be reactivated under certain circumstances.

Exploring the dynamics of extinction and spontaneous recovery within classical conditioning reveals the intricate nature of learning and behaviour. These phenomena demonstrate that conditioned responses are subject to change and that the process of acquiring and modifying associations is dynamic and ongoing.

By recognising that conditioned responses can be weakened through extinction but may resurface through spontaneous recovery, we gain valuable insights into the intricacies of learning processes and the adaptive nature of behaviour.

The exploration of these dynamics expands our understanding of classical conditioning and its implications in various real-world scenarios.

Generalisation occurs when organisms respond to stimuli similar to the conditioned stimulus, whilst discrimination involves distinguishing between different stimuli and responding only to specific ones. These opposing processes determine how broadly or narrowly conditioned responses are applied in classical conditioning.

Generalization occurs when similar stimuli to the conditioned stimulus also trigger the conditioned response, like a dog salivating to different bell tones. Discrimination happens when the organism learns to respond only to the specific conditioned stimulus and not to similar ones, showing refined learning. These processes help organisms adapt by either broadening or narrowing their responses based on environmental cues.

In the intricate domain of classical conditioning, two key concepts, generalisation and discrimination, play a crucial role in understanding the boundaries of learned responses. These components shed light on the delicate balance between expanding conditioned responses to similar stimuli and differentiating between specific stimuli.

Generalisation occurs when a conditioned response, initially elicited by a specific conditioned stimulus (CS), is also produced in the presence of similar stimuli that share certain features with the original CS. This generalisation occurs because the organism has learned to associate the original CS with the unconditioned stimulus (US) and subsequently transfers that association to similar stimuli.

The broader the generalisation, the more similar the stimuli are perceived to be by the organism. Generalisation allows for adaptive behaviour, as it enables the transfer of learned responses to novel situations.

On the other hand, discrimination involves the ability to differentiate between stimuli and respond selectively to a specific conditioned stimulus. Discrimination occurs when an organism learns to respond to one particular stimulus while withholding the response in the presence of other stimuli that differ in some way. Discrimination reflects the ability to detect subtle differences in stimuli and respond in a targeted manner.

Understanding the fine line between generalisation and discrimination is crucial in Pavlovian conditioning. While generalisation allows for flexibility in responding to similar stimuli, discrimination helps organisms refine their responses and respond selectively to specific cues. Striking the right balance between generalisation and discrimination is vital for adaptive behaviour and efficient learning.

Anyone studying psychology can benefit from comprehending the components of generalisation and discrimination within classical conditioning. By understanding how organisms generalise responses to similar stimuli and discriminate between different stimuli, students gain insights into the complexities of Pavlovian conditioning.

These components illuminate the delicate dynamics of learning and behaviour, highlighting the nuanced interplay between broadening associations and honing selective responses. The exploration of this fine line contributes to our understanding of how organisms navigate their environments and adapt to varying stimuli.

Classical conditioning is used in systematic desensitization to treat phobias by gradually pairing relaxation with feared stimuli until the fear response is reduced. Aversion therapy uses conditioning to create negative associations with unwanted behaviours like addiction by pairing them with unpleasant stimuli. These therapeutic applications help modify problematic behaviours and emotional responses through controlled conditioning processes.

The components of classical conditioning extend beyond theoretical constructs, finding practical applications in various domains, both within the field of psychology and beyond. Pavlov's groundbreaking theory has sparked effective ideas and applications that have permeated numerous fields, making it a cornerstone of scientific understanding and practical implementation.

In the field of psychology, classical conditioning has been utilised in therapeutic interventions. Through a process known as systematic desensitisation, individuals with phobias or anxiety disorders can gradually overcome their fears.

This therapeutic approach involves exposing individuals to a hierarchy of fear-inducing stimuli while simultaneously engaging in relaxation techniques. By pairing the feared stimuli with a state of relaxation, a new conditioned response can be formed, leading to reduced anxiety or phobic reactions.

Marketing and advertising professionals have also capitalised on classical conditioning principles. By pairing products or brands with positive stimuli, such as attractive models, captivating music, or appealing environments, they aim to create positive associations and elicit desirable responses from consumers.

This strategic use of classical conditioning can shape consumers' preferences, increase brand recognition, and influence purchasing decisions.

Furthermore, classical conditioning has found applications in education. Teachers employ various techniques to facilitate learning by creating associations between neutral stimuli and meaningful content. For instance, using mnemonic devices, such as acronyms or vivid imagery, can aid in memory retention and recall. These techniques use the power of conditioning to enhance learning outcomes and promote knowledge acquisition.

Beyond psychology, classical conditioning principles have permeated diverse fields, including animal training, sports, and even politics. Animal trainers use conditioning techniques to teach animals new behaviours or modify existing ones. In sports, coaches employ conditioning methods to associate specific stimuli, such as a whistle or a particular gesture, with desired athlete responses.

Politicians often use classical conditioning strategies to associate themselves with positive stimuli, such as patriotic symbols or memorable slogans, aiming to evoke favourable responses from voters.

Understanding the practical applications of Pavlov's theory in psychology and beyond helps students to appreciate the wide-ranging impact of classical conditioning. By recognising how this theory is utilised in therapeutic settings, marketing strategies, educational approaches, and various other domains, students gain a complete understanding of the relevance and versatility of classical conditioning principles.

This knowledge equips them to critically analyse and apply these concepts in real-world scenarios, paving the way for effective problem-solving and further advancements in multiple fields.

Pavlov's theory faces criticism for oversimplifying human behaviour, focusing primarily on reflexive responses rather than cognitive processes. Critics argue that classical conditioning cannot fully explain complex learning, voluntary behaviour, or individual differences in learning capacity and motivation.

Critics argue that classical conditioning oversimplifies learning by focusing only on observable behaviours while ignoring cognitive processes and individual differences. The theory also cannot fully explain complex human behaviours, voluntary actions, or the role of consciousness in learning. Modern perspectives incorporate cognitive and biological factors, recognising that learning involves more than simple stimulus-response associations.

While Pavlov's theory of classical conditioning has made significant contributions to the field of psychology, it isn't without its fair share of criticisms and evolving perspectives. As with any scientific theory, critical evaluation and ongoing research have prompted the emergence of alternative viewpoints and refinements to the original framework.

One criticism directed at Pavlov's theory pertains to its emphasis on the passive nature of the organism in the learning process. Some argue that classical conditioning overlooks the active role of cognitive processes, such as attention, memory, and expectation, in shaping behaviour.

Contemporary perspectives, such as cognitive-behavioural approaches, highlight the interplay between cognitive factors and conditioning processes, providing a more comprehensive understanding of how learning occurs.

Another criticism revolves around the generalisability of classical conditioning principles across different species and contexts. Critics argue that animals and humans may exhibit unique learning patterns and preferences that can't be entirely explained by Pavlov's theory.

The study of individual differences and cultural influences has shed light on the complexities of learning and behaviour, challenging the notion of a one-size-fits-all approach to conditioning.

Furthermore, contemporary perspectives have expanded upon Pavlov's theory by introducing concepts such as higher-order conditioning and biological constraints.

Higher-order conditioning refers to the process where a conditioned stimulus becomes associated with a new neutral stimulus, further expanding the range of stimuli that can elicit conditioned responses. Biological constraints emphasise the idea that certain associations are more easily formed due to inherent predispositions or limitations imposed by an organism's biology.

recognise that scientific theories, including Pavlov's, are subject to scrutiny and revision. By acknowledging criticisms and considering contemporary perspectives, we can develop a more nuanced understanding of the strengths and limitations of classical conditioning as a framework for explaining learning and behaviour.

This critical evaluation encourages further exploration and the development of new theories that encompass a broader range of factors and account for the complexities inherent in the study of psychology.

Pavlov's theory remains important because it provides foundational understanding of associative learning used in therapy, education, and behavioural modification. Modern applications include treating phobias, developing teaching methods, and understanding consumer behaviour patterns across multiple disciplines.

Pavlov's theory remains crucial because it explains fundamental learning processes that apply to education, therapy, marketing, and everyday behaviour modification. The principles of classical conditioning help therapists treat phobias and addictions, educators design effective teaching strategies, and marketers create brand associations. Understanding these basic learning mechanisms provides insights into both adaptive and maladaptive behaviours across all areas of human experience.

Q1: Who is Ivan Pavlov?

Ivan Pavlov was a renowned Russian psychologist who made significant contributions to the field of psychology through his work on conditioned reflexes.

Q2: What are conditioned reflexes?

Conditioned reflexes are learned responses. Pavlov demonstrated through his experiments that these responses are developed when a neutral stimulus is consistently paired with a stimulus that naturally triggers a response.

Q3: What is an unconditioned reflex?

An unconditioned reflex is a natural, automatic response to a stimulus. In Pavlov's experiments, the unconditioned reflex was the dogs' salivation in response to the sight or smell of food.

Q4: How do emotional responses fit into Pavlov's theory?

Pavlov's theory suggests that emotional responses can also be conditioned. This means that our emotional reactions to certain stimuli can be shaped and influenced by our past experiences and associations.

Q5: Can you explain the classical conditioning process?

The classical conditioning process, as described by Pavlov, involves pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus that naturally triggers a response. Over time, the neutral stimulus alone can trigger the same response. This was demonstrated in Pavlov's experiments with dogs, where the sound of a bell (neutral stimulus) was paired with the presentation of food (unconditioned stimulus). Eventually, the dogs began to salivate (response) just at the sound of the bell.

Q6: What was Pavlov's work on the digestive glands?

Pavlov's work on the digestive glands of dogs was what led him to his discovery of the conditioned reflex. He noticed that dogs would begin to salivate not only at the sight of food but also at the sight of the person who usually fed them. This observation formed the basis of his experiments on conditioned reflexes.

Q7: How did Pavlov demonstrate salivation in dogs?