Thinking Routines for Deeper Understanding

Discover thinking routines: simple question sequences that reveal student thinking and deepen learning, with practical tips for embedding them across subjects.

Discover thinking routines: simple question sequences that reveal student thinking and deepen learning, with practical tips for embedding them across subjects.

It all started with Project Zero's Visible Thinking initiative at Harvard's Graduate School of Education. These routines have proven remarkably effective in developing student cognitive skillsacross different backgrounds and subjects.

While they may sound complex, these routines are simply sets of questions or short sequences. They . Over time, they become part of classroom culture. Their purpose is clear: create spaces where thinking is visible, celebrated, and woven into learning. As metacognition develops through these thinking routines in mathematics and other subjects, students become more aware of their own thought processes - getting started with these routines helps teachers scaffold this development.

The thinking routines toolbox defines these routines as sequences of questions or steps that guide students in their thought processes. It groups them into Core Thinking and Possibilities, along with other methods for organising and combining ideas.

With over 80 routines available, teachers can adapt them to fit different settings. Think of it as a toolkit designed to make thinking skill development more visible. This encourages a stronger connection with the content being learned.

The journey began with Project Zero researchers at Harvard, driven by a desire to support student thinking. By using a set of questions or a sequence of steps, these routines make invisible thinking processes visible. This strengthens students' memory and cognitive abilities.

The Thinking Routines Toolbox offers different types like Core Thinking Routines and systems for concept mapping. Teachers play a key role here. These routines help them see how students think, enabling learners to spot and use specific thinking moves across different contexts.

These routines work across subjects, not just English. They build understanding and help communication across all areas of study.

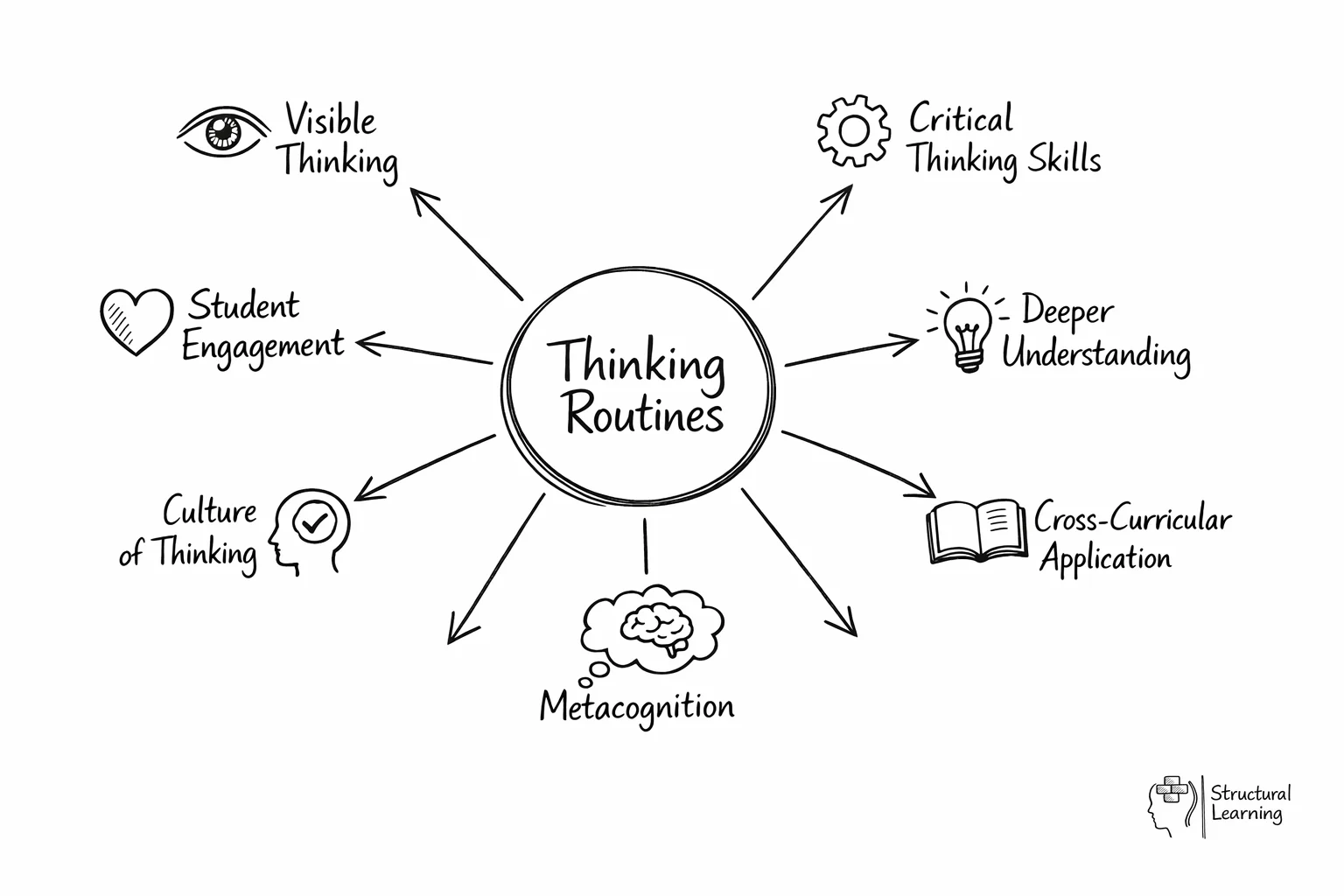

Thinking routines work as a useful tool in schools, especially when building a culture of inquiry-based learning among students. They structure student thinking, creating ways for learners to explore and share their thoughts in meaningful ways.

By using these routines, teachers can show the thinking processes happening in their classrooms. This allows for a more inclusive and interactive learning space. The routines can be adapted across different subjects and year groups, offering the flexibility needed to meet diverse student needs.

Their structured yet flexible nature helps students from all backgrounds engage in open discussions. This builds a culture where thinking becomes a visible and key part of learning.

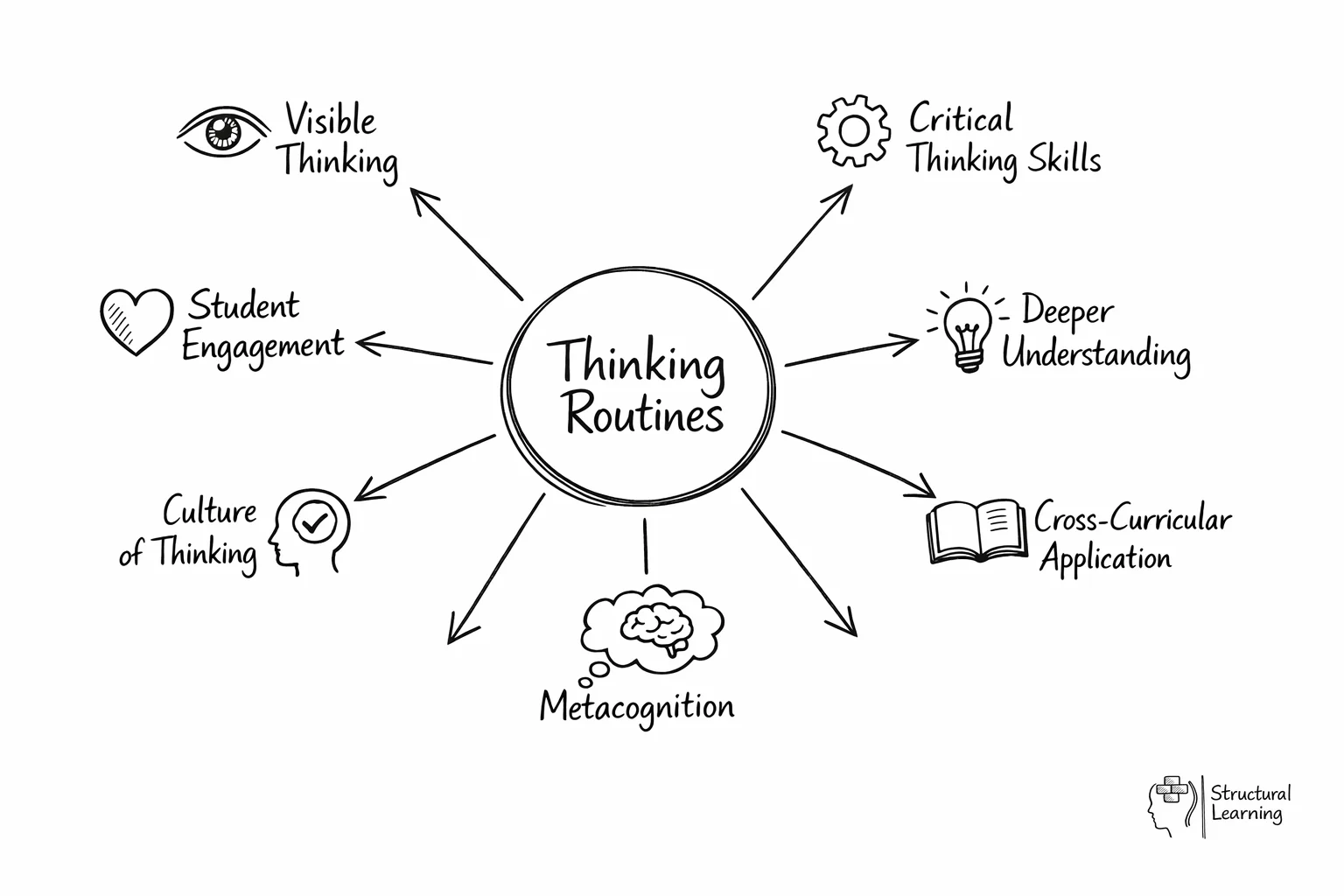

When we talk about building critical thinking in education, thinking routines play a significant role. These routines are carefully designed to make thinking processes clear and visible to students as they work through learning challenges.

By taking part in these routines, students build critical thinking skills. These skills are essential for analysing complex ideas and making informed decisions. Over time, thinking routines grow with the student, guiding them toward deeper levels of thinking.

They give teachers a framework to create a classroom atmosphere that welcomes questioning and intellectual engagement. The flexibility of these routines means they can work across different subjects, ensuring critical thinking runs through project-based learning experiences.

Students who feel engaged can explore and reflect on ideas more deeply. Through engagement with thinking routines, students develop stronger motivation to learn. These routines provide a clear structure that helps students see their progress and builds their confidence in sharing ideas.

Beyond immediate classroom benefits, thinking routines contribute to long-term metacognitive development. Research by John Flavell demonstrates that students who regularly engage with structured thinking processes become more aware of their own learning strategies. This metacognitive awareness translates into improved self-regulation and academic autonomy.

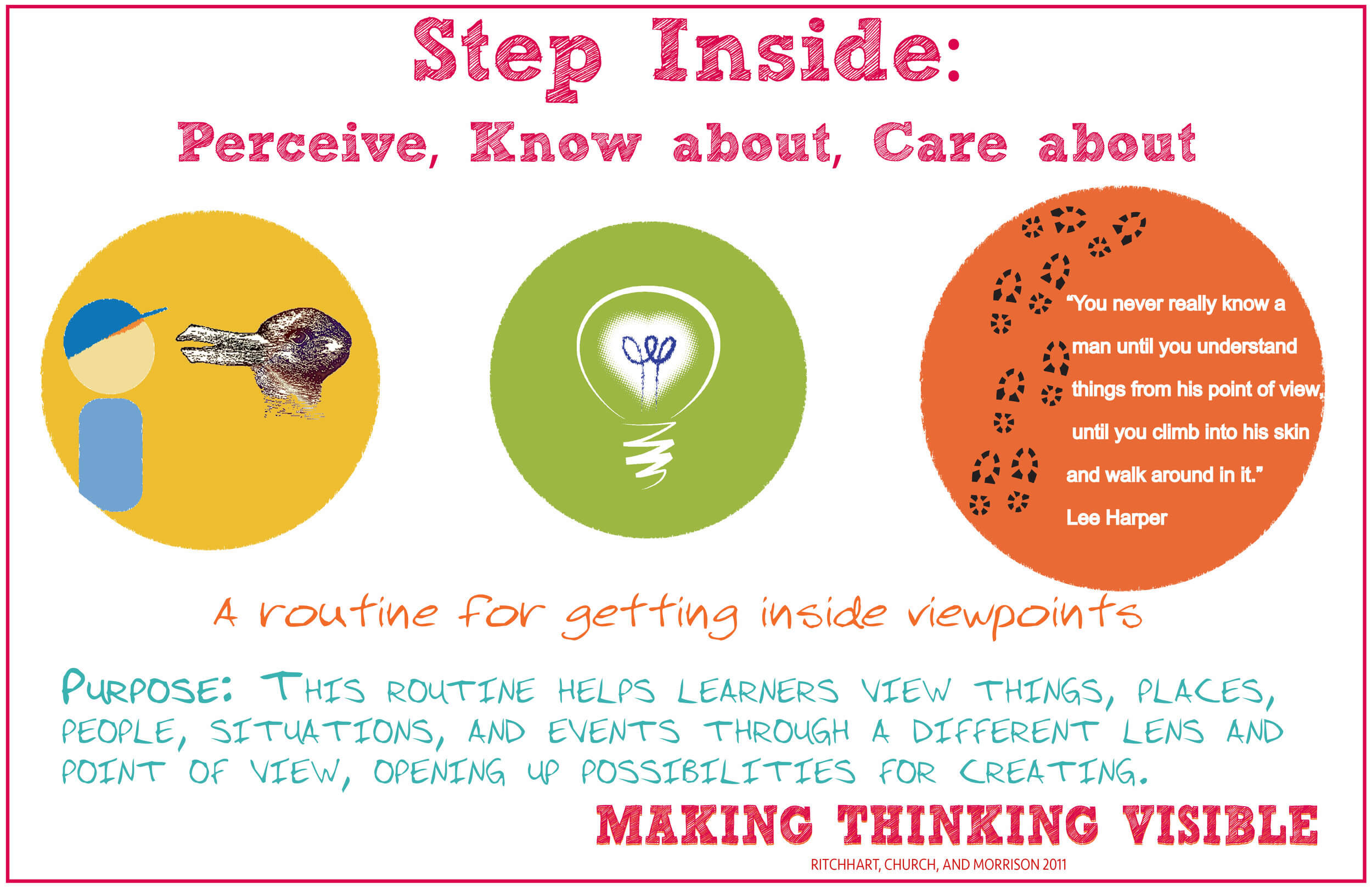

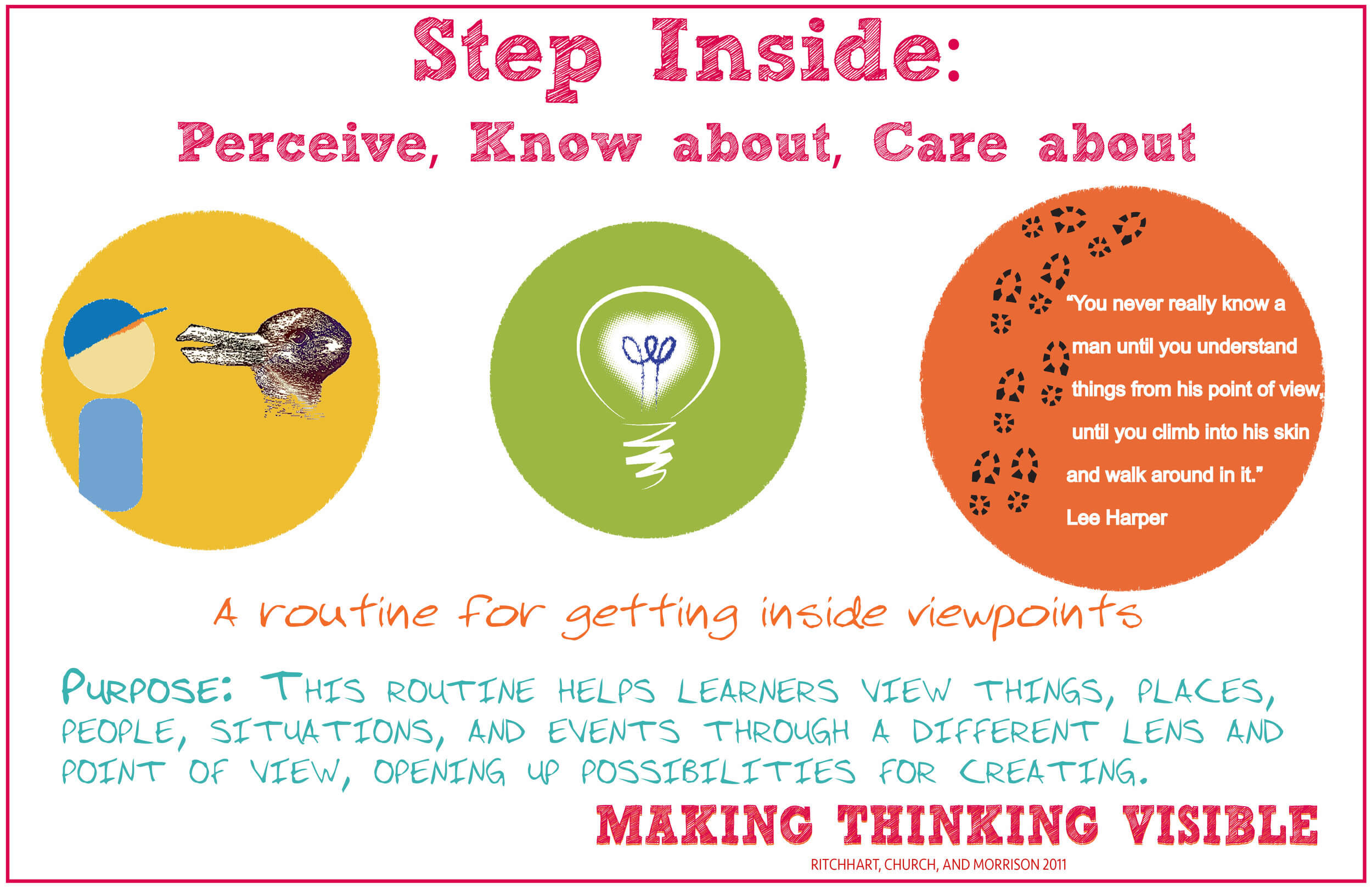

The social dimension of thinking routines cannot be overlooked. When students engage in routines like 'Circle of Viewpoints' or 'Step Inside', they develop empathy and perspective-taking skills essential for collaborative learning. These routines create a classroom culture where diverse viewpoints are valued and intellectual risk-taking is encouraged.

Furthermore, thinking routines support differentiated instruction by providing multiple entry points for learners. Visual learners benefit from routines incorporating diagrams and concept maps, whilst kinesthetic learners engage through movement-based reflection activities. This flexibility ensures that thinking routines can accommodate various learning preferences and abilities within a single classroom.

Thinking routines are structured patterns of thinking that help students approach learning tasks more systematically and thoughtfully. Developed by researchers at Harvard's Project Zero, these cognitive frameworks provide students with explicit steps to analyse information, make connections, and reflect on their understanding. Rather than leaving thinking to chance, routines offer a scaffolded approach that makes invisible thinking visible, transforming abstract cognitive processes into concrete, observable actions that teachers can guide and students can master.

These routines work by breaking down complex thinking into manageable components, aligning with Daniel Willingham's research on cognitive science which shows that explicit instruction in thinking processes enhances learning outcomes. When students repeatedly practice structured approaches like "Think-Pair-Share" or "What Makes You Say That?", they internalise these patterns and begin applying them independently across different subjects and contexts. This metacognitive development enables learners to become more aware of their own thinking processes.

In classroom practice, thinking routines serve as powerful tools for deepening student engagement and understanding. They create predictable structures that reduce cognitive load whilst simultaneously challenging students to think more rigorously about content, developing both academic growth and critical thinking skills that extend far beyond individual lessons.

The cognitive science behind thinking routines reveals why they are so effective in educational settings. When students repeatedly engage with structured thinking processes, they develop what psychologists call 'procedural fluency' - the ability to carry out thinking strategies efficiently and accurately. This automaticity allows students to focus their mental energy on the content and concepts being explored rather than on remembering how to think about them. Neuroscientific research supports this, showing that repeated use of thinking patterns strengthens neural pathways, making complex reasoning more accessible to learners of all abilities.

In practical terms, this means that a Year 3 student using 'Think-Pair-Share' for the tenth time can concentrate fully on their mathematical reasoning, whilst a Year 10 student applying 'What Makes You Say That?' can examine deeper into textual analysis without cognitive overload. Teachers consistently report that after just a few weeks of regular implementation, students begin to use these thinking moves independently, asking themselves probing questions and seeking evidence for their ideas even when not prompted to do so.

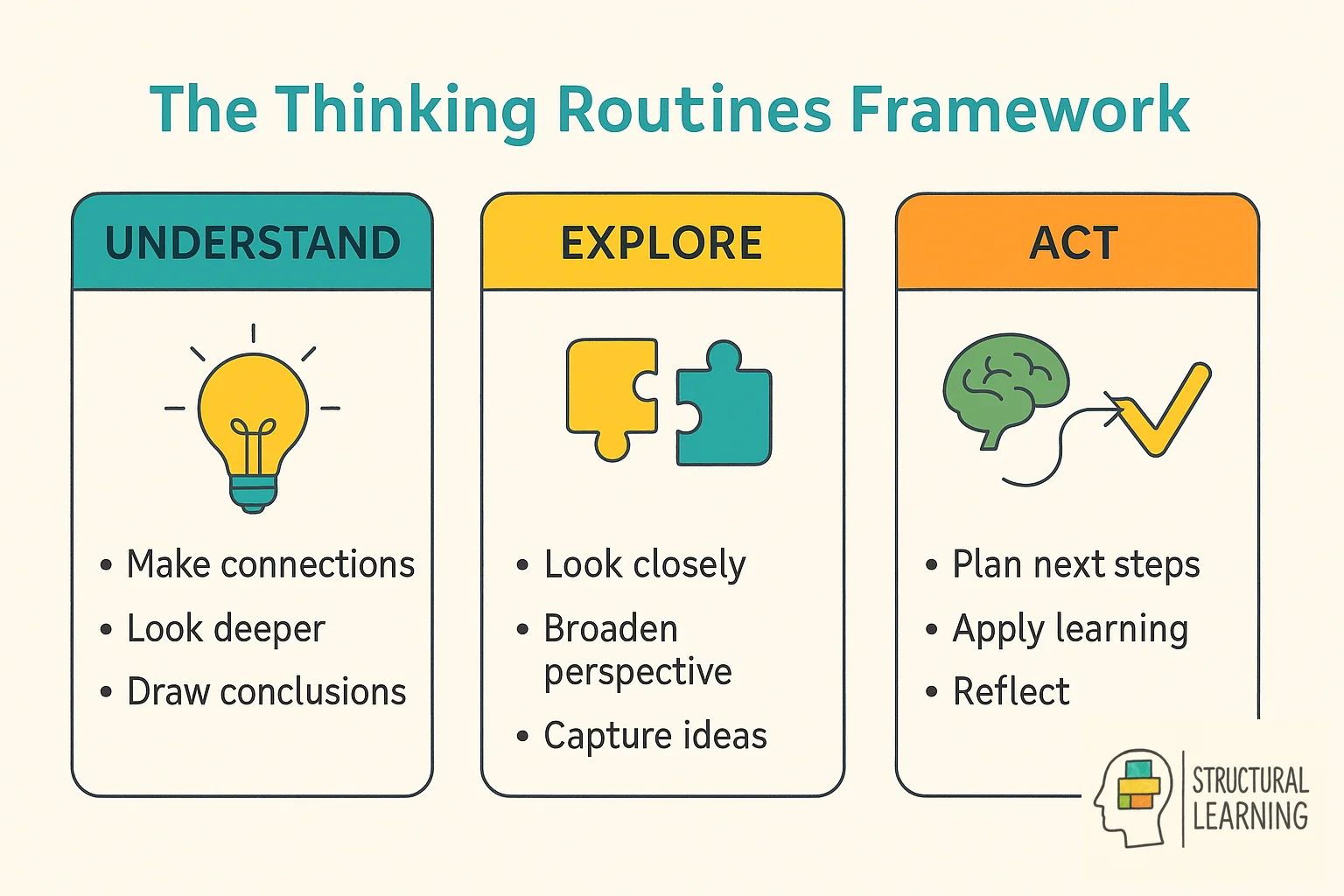

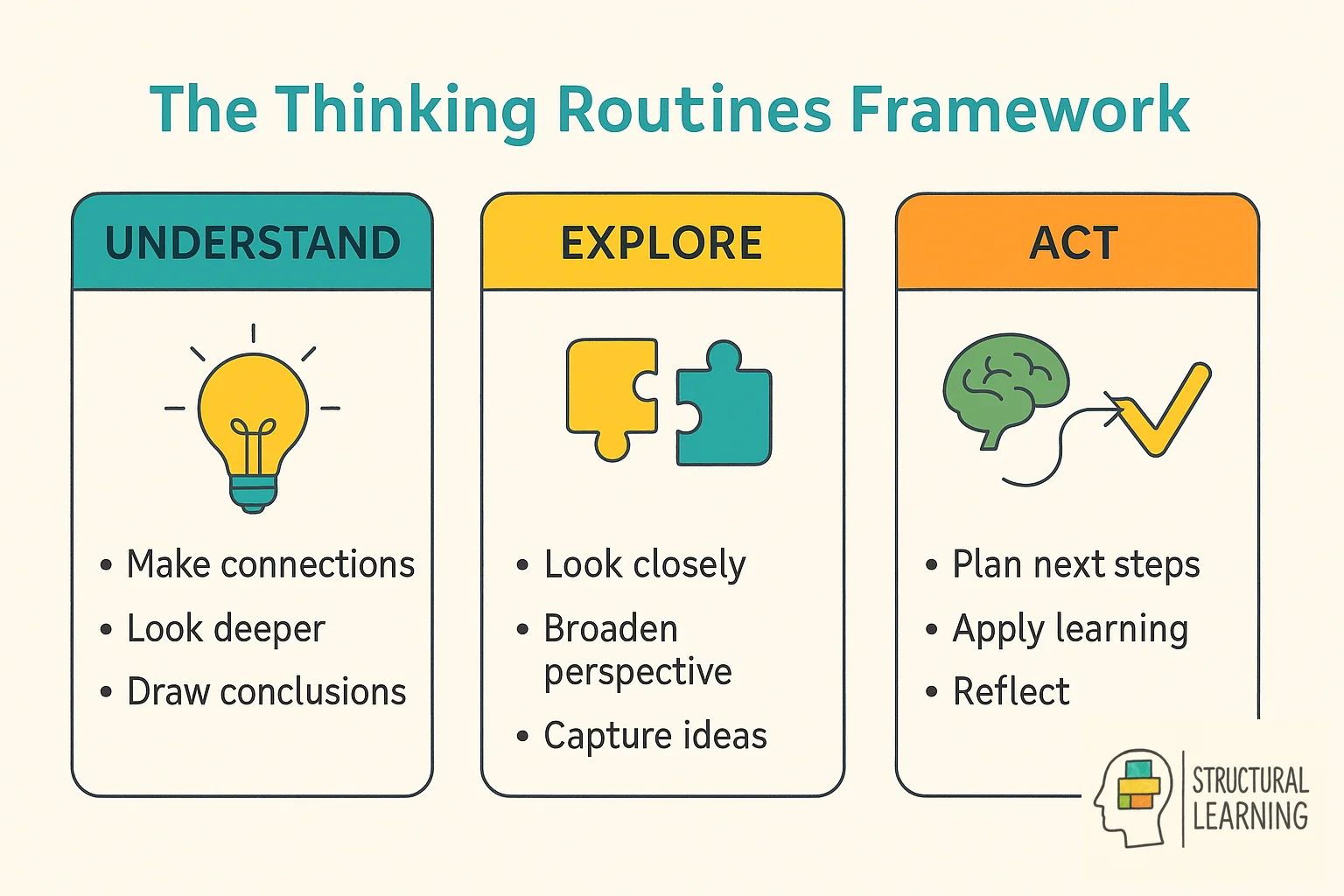

Thinking routines fall into distinct categories, each designed to cultivate specific cognitive processes and deepen student understanding. Understanding routines help learners explore ideas, uncover assumptions, and make thinking visible through structured inquiry. Meanwhile, truth and fairness routines develop critical evaluation skills, encouraging students to examine evidence, consider multiple perspectives, and assess the reliability of sources.

Creative thinking routines creates innovation and original thought by providing scaffolds for brainstorming, generating alternatives, and exploring possibilities. These complement dilemma routines, which guide students through complex decision-making processes and ethical considerations. Ron Ritchhart's research demonstrates that this categorisation helps educators select appropriate routines based on their learning objectives, whether developing analytical skills, creative problem-solving, or metacognitive awareness.

Effective classroom practice involves matching routine types to curriculum goals and student needs. For instance, understanding routines like "See-Think-Wonder" work particularly well when introducing new concepts, whilst truth and fairness routines such as "Circle of Viewpoints" enhance critical analysis of historical events or literary texts. By deliberately choosing routines from different categories throughout a unit, teachers create a comprehensive thinking framework that supports both content mastery and cognitive development.

Understanding routines focus on building comprehension and encouraging careful observation. Beyond the basic 'See-Think-Wonder', routines like 'Zoom In' help students examine details methodically, whilst 'Circle of Viewpoints' encourages perspective-taking. These routines are particularly effective in humanities subjects where interpretation and multiple perspectives are crucial.

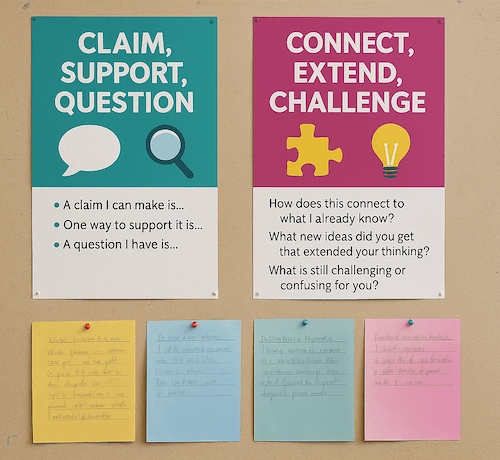

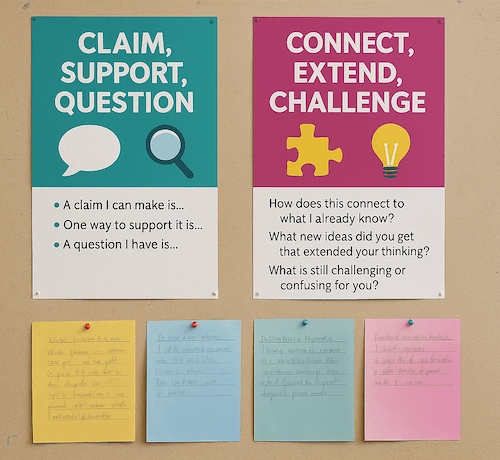

Synthesis routines help students connect ideas and identify patterns. 'Connect-Extend-Challenge' pushes learners to link new information with prior knowledge, extend their thinking, and identify points of confusion or disagreement. The '3-2-1 Bridge' routine captures thinking before and after learning, making knowledge construction visible to both teacher and student.

Creative thinking routines like 'What Makes You Say That?' demand evidence-based reasoning, whilst 'Step Inside' encourages empathetic thinking. Truth and fairness routines, including 'Tug of War' and 'Options-Explode', help students examine multiple sides of complex issues and consider various solutions to problems.

When selecting thinking routines for classroom implementation, consider your learning objectives and the cognitive skills you want to develop. Understanding routines work exceptionally well as lesson openers, creating curiosity and engagement from the start. For instance, 'Think-Puzzle-Explore' can transform a potentially mundane topic introduction into an investigation, with students generating their own questions to guide learning.

Synthesis routines prove most valuable during and after learning experiences, helping students consolidate understanding and make meaningful connections. The key to successful implementation lies in consistent use rather than variety, students develop deeper metacognitive awareness when they become familiar with routine structures, allowing them to focus entirely on the thinking process rather than procedural confusion.

See-Think-Wonder stands as one of the most versatile thinking routines, developed by Harvard's Project Zero team. This three-step process encourages students to observe carefully (See), make interpretations based on evidence (Think), and generate questions for further inquiry (Wonder). Research by Ron Ritchhart demonstrates how this routine develops both critical thinking skills and curiosity, making it particularly effective across subjects from analysing historical photographs to examining scientific phenomena.

Think-Pair-Share uses collaborative learning to deepen individual understanding. Students first process information independently, then discuss their thoughts with a partner before sharing with the larger group. This scaffolded approach aligns with Lev Vygotsky's zone of proximal development, allowing learners to refine their thinking through peer interaction whilst building confidence before contributing to whole-class discussions.

In practice, these routines work best when teachers model the thinking process explicitly and provide adequate wait time for reflection. Begin with simpler content to establish the routine's structure, then gradually apply it to more complex material. The key lies in consistency: regular use transforms these frameworks from novel activities into natural habits of mind that students apply independently across learning contexts.

These routines prove essential because they transform abstract thinking processes into concrete, repeatable structures that students can internalise and apply independently. Unlike traditional questioning approaches that often favour confident speakers, thinking routines create equitable participation opportunities. The predictable frameworks reduce cognitive load, allowing students to focus on content rather than process, which particularly benefits learners with additional needs or those developing English proficiency.

Successful classroom implementation requires consistent modelling and gradual release of responsibility. Teachers might begin by posting visual prompts for each routine, explicitly narrating their own thinking during demonstrations, and celebrating when students use the structures spontaneously in discussions. The key lies in patience - students need multiple exposures before routines become automatic thinking tools rather than teacher-directed activities.

When embedded systematically, these routines cultivate a classroom culture where thinking becomes visible and valued. Students begin questioning each other's reasoning constructively, building on ideas collectively, and reflecting on their learning journey without prompting. This metacognitive awareness transforms passive recipients into active thinkers who can articulate what they know and how they came to know it.

Successful implementation of thinking routines requires gradual introduction and consistent practice rather than overwhelming students with multiple new frameworks simultaneously. Begin with one routine that aligns naturally with your existing curriculum, modelling the process explicitly whilst thinking aloud to demonstrate metacognitive reasoning. As Harvard's Project Zero research suggests, routines become most effective when students internalise the underlying thinking patterns, transforming what initially feels structured into fluid intellectual habits.

The key to embedding routines lies in creating a classroom culture that values thinking processes as much as final answers. Establish clear expectations by displaying routine steps visually, allowing adequate processing time, and celebrating thoughtful reasoning over quick responses. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that students need sufficient mental capacity to engage deeply with content, so reduce extraneous cognitive burden by maintaining consistent routine structures whilst varying the subject matter.

Monitor implementation success through observation of student discourse and self-reflection. When routines are working effectively, you'll notice students naturally using the language and questioning patterns independently, asking follow-up questions that extend beyond surface-level responses. Document these moments of transfer, as they indicate that thinking routines are achieving their ultimate purpose: developing students' capacity for autonomous, critical thinking across diverse contexts.

Successful implementation requires careful attention to classroom culture and student preparation. Begin by explicitly teaching the routine steps, modelling your own thinking process, and providing sentence starters or thinking stems to support student responses. For example, when introducing 'See-Think-Wonder', offer phrases like 'I notice..', 'This makes me think..', or 'I wonder why..' to help students articulate their thoughts.

Timing and pacing are crucial for success. Allow sufficient think time, particularly for understanding routines where rushed responses undermine the purpose. Research by cognitive scientist Mary Budd Rowe shows that increasing wait time from three to seven seconds dramatically improves response quality and participation rates. Build in processing breaks during longer routines to prevent cognitive overload.

Documentation enhances the impact of thinking routines significantly. Use visible thinking strategies like anchor charts to record student thinking, creating a classroom environment where ideas are valued and revisited. Digital tools can capture thinking for reflection and assessment, but avoid letting technology overshadow the thinking process itself.

Assessing learning through thinking routines requires a shift from traditional content-focused evaluation to process-oriented observation that captures students' developing cognitive abilities. Rather than simply measuring what students know, educators must examine how students think, reason, and apply their understanding across diverse contexts. This approach aligns with Dylan Wiliam's research on formative assessment, which emphasises the importance of gathering evidence about student thinking to inform instructional decisions.

Effective assessment strategies include documenting students' verbal contributions during routine discussions, analysing written reflections that reveal metacognitive development, and observing collaborative problem-solving processes. Teachers can create simple rubrics that focus on the quality of questions students ask, their ability to build upon others' ideas, and their willingness to revise thinking based on new evidence. Portfolio collections of student work over time provide particularly valuable insights into growth patterns.

The most powerful assessment occurs when students become partners in evaluating their own learning journey. Encourage learners to maintain thinking journals, conduct peer feedback sessions, and regularly reflect on which routines enhance their understanding most effectively. This self-assessment approach not only provides authentic evidence of growth but also strengthens students' metacognitive awareness, creating a sustainable cycle of reflective learning that extends far beyond individual classroom activities.

Successful implementation of thinking routines requires careful consideration of students' cognitive development and processing capabilities. Jerome Bruner's developmental theory suggests that learners progress through distinct stages, from concrete operational thinking in primary years to abstract reasoning in secondary education. This progression directly impacts which thinking routines will be most effective: younger learners benefit from visual and tactile approaches like "See-Think-Wonder" or "Chalk Talk," whilst older students can engage with more complex metacognitive strategies such as "What Makes You Say That?" or "Circle of Viewpoints."

Primary educators should focus on routines that scaffold thinking through concrete representations and collaborative discussion. Simple structures like "I Used to Think.. Now I Think" work effectively when supported by drawings, manipulatives, or shared experiences. Secondary practitioners can introduce routines requiring greater abstraction and independent reflection, building students' capacity for autonomous critical thinking. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates why age-appropriate selection matters: overwhelming young learners with complex thinking processes can actually inhibit deeper understanding rather than promote it.

The key lies in gradual progression and responsive adaptation. Begin each academic year assessing students' comfort with metacognitive language, then systematically introduce routines that stretch their thinking whilst remaining accessible. This developmental approach ensures thinking routines become genuine tools for learning rather than merely procedural exercises.

The research foundation for thinking routines is robust and spans over two decades of educational investigation. Ron Ritchhart and David Perkins from Harvard's Project Zero have conducted extensive studies demonstrating that structured thinking routines significantly enhance students' metacognitive awareness and critical thinking capabilities. Their longitudinal research across diverse classroom settings shows that students who regularly engage with thinking routines develop stronger analytical skills and demonstrate improved ability to transfer learning across subjects.

Neurocognitive research further supports these findings, with studies indicating that thinking routines create optimal conditions for deep learning by reducing extraneous cognitive load whilst focusing attention on essential thinking processes. Research by Swartz and Parks reveals that students using thinking routines show measurable gains in reasoning quality and demonstrate increased confidence in expressing complex ideas. Particularly significant is evidence showing that these benefits persist over time, suggesting that thinking routines establish lasting cognitive habits rather than temporary skill improvements.

Classroom-based research consistently demonstrates that thinking routines enhance student engagement across all ability levels. Teachers report that previously reluctant learners become more willing to contribute when provided with structured thinking frameworks, whilst high-achieving students develop greater depth in their reasoning. This evidence base provides compelling justification for systematic implementation of thinking routines as a core pedagogical strategy.

In a Year 5 science lesson exploring states of matter, teacher Sarah Mitchell implemented the See-Think-Wonder routine with remarkable results. Students observed ice melting in different conditions, systematically recording what they noticed, their initial hypotheses, and questions that emerged. Rather than rushing to explanations, this structured approach allowed pupils to develop genuine curiosity about molecular behaviour and heat transfer, with many spontaneously connecting observations to previous learning about particles.

Meanwhile, secondary English teacher James Chen uses Connect-Extend-Challenge to deepen literary analysis. After reading Macbeth, students connect themes to contemporary issues, extend Shakespeare's ideas to modern contexts, and challenge assumptions about power and ambition. This routine transforms passive reading into active meaning-making, with pupils demonstrating sophisticated critical thinking that extends well beyond plot comprehension.

Mathematics presents equally powerful opportunities, as demonstrated by Year 8 teacher Priya Patel's implementation of What Makes You Say That? during problem-solving sessions. When students propose solutions to complex word problems, peers respectfully probe their reasoning using this routine's framework. David Perkins' research on visible thinking confirms that such structured questioning develops both mathematical reasoning and metacognitive awareness, helping students recognise and articulate their thought processes.

Even the most well-intentioned thinking routines can falter when predictable implementation challenges arise. Student resistance often emerges when learners feel uncertain about open-ended questioning or fear giving 'wrong' answers. To counter this, establish psychological safety by celebrating partial thinking and modelling your own thought processes aloud. When students observe teachers genuinely wrestling with complex ideas, they become more willing to engage in visible thinking themselves.

Time constraints represent another common obstacle, particularly when curriculum pressures mount. However, John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that investing time in metacognitive awareness actually accelerates learning by helping students process information more efficiently. Start with brief, two-minute routines like 'Think-Pair-Share' before progressing to more elaborate structures. Remember that thinking routines replace rather than add to existing activities.

Maintaining consistent engagement requires strategic variety and purposeful implementation. Rotate between different routines to prevent staleness, but avoid overwhelming students with too many new structures simultaneously. Focus on mastering two or three routines thoroughly before introducing additional approaches. Most importantly, make thinking visible by capturing student responses on wall displays, learning journals, or digital platforms, creating a classroom culture where deeper understanding becomes the expected norm rather than an occasional occurrence.

It all started with Project Zero's Visible Thinking initiative at Harvard's Graduate School of Education. These routines have proven remarkably effective in developing student cognitive skillsacross different backgrounds and subjects.

While they may sound complex, these routines are simply sets of questions or short sequences. They . Over time, they become part of classroom culture. Their purpose is clear: create spaces where thinking is visible, celebrated, and woven into learning. As metacognition develops through these thinking routines in mathematics and other subjects, students become more aware of their own thought processes - getting started with these routines helps teachers scaffold this development.

The thinking routines toolbox defines these routines as sequences of questions or steps that guide students in their thought processes. It groups them into Core Thinking and Possibilities, along with other methods for organising and combining ideas.

With over 80 routines available, teachers can adapt them to fit different settings. Think of it as a toolkit designed to make thinking skill development more visible. This encourages a stronger connection with the content being learned.

The journey began with Project Zero researchers at Harvard, driven by a desire to support student thinking. By using a set of questions or a sequence of steps, these routines make invisible thinking processes visible. This strengthens students' memory and cognitive abilities.

The Thinking Routines Toolbox offers different types like Core Thinking Routines and systems for concept mapping. Teachers play a key role here. These routines help them see how students think, enabling learners to spot and use specific thinking moves across different contexts.

These routines work across subjects, not just English. They build understanding and help communication across all areas of study.

Thinking routines work as a useful tool in schools, especially when building a culture of inquiry-based learning among students. They structure student thinking, creating ways for learners to explore and share their thoughts in meaningful ways.

By using these routines, teachers can show the thinking processes happening in their classrooms. This allows for a more inclusive and interactive learning space. The routines can be adapted across different subjects and year groups, offering the flexibility needed to meet diverse student needs.

Their structured yet flexible nature helps students from all backgrounds engage in open discussions. This builds a culture where thinking becomes a visible and key part of learning.

When we talk about building critical thinking in education, thinking routines play a significant role. These routines are carefully designed to make thinking processes clear and visible to students as they work through learning challenges.

By taking part in these routines, students build critical thinking skills. These skills are essential for analysing complex ideas and making informed decisions. Over time, thinking routines grow with the student, guiding them toward deeper levels of thinking.

They give teachers a framework to create a classroom atmosphere that welcomes questioning and intellectual engagement. The flexibility of these routines means they can work across different subjects, ensuring critical thinking runs through project-based learning experiences.

Students who feel engaged can explore and reflect on ideas more deeply. Through engagement with thinking routines, students develop stronger motivation to learn. These routines provide a clear structure that helps students see their progress and builds their confidence in sharing ideas.

Beyond immediate classroom benefits, thinking routines contribute to long-term metacognitive development. Research by John Flavell demonstrates that students who regularly engage with structured thinking processes become more aware of their own learning strategies. This metacognitive awareness translates into improved self-regulation and academic autonomy.

The social dimension of thinking routines cannot be overlooked. When students engage in routines like 'Circle of Viewpoints' or 'Step Inside', they develop empathy and perspective-taking skills essential for collaborative learning. These routines create a classroom culture where diverse viewpoints are valued and intellectual risk-taking is encouraged.

Furthermore, thinking routines support differentiated instruction by providing multiple entry points for learners. Visual learners benefit from routines incorporating diagrams and concept maps, whilst kinesthetic learners engage through movement-based reflection activities. This flexibility ensures that thinking routines can accommodate various learning preferences and abilities within a single classroom.

Thinking routines are structured patterns of thinking that help students approach learning tasks more systematically and thoughtfully. Developed by researchers at Harvard's Project Zero, these cognitive frameworks provide students with explicit steps to analyse information, make connections, and reflect on their understanding. Rather than leaving thinking to chance, routines offer a scaffolded approach that makes invisible thinking visible, transforming abstract cognitive processes into concrete, observable actions that teachers can guide and students can master.

These routines work by breaking down complex thinking into manageable components, aligning with Daniel Willingham's research on cognitive science which shows that explicit instruction in thinking processes enhances learning outcomes. When students repeatedly practice structured approaches like "Think-Pair-Share" or "What Makes You Say That?", they internalise these patterns and begin applying them independently across different subjects and contexts. This metacognitive development enables learners to become more aware of their own thinking processes.

In classroom practice, thinking routines serve as powerful tools for deepening student engagement and understanding. They create predictable structures that reduce cognitive load whilst simultaneously challenging students to think more rigorously about content, developing both academic growth and critical thinking skills that extend far beyond individual lessons.

The cognitive science behind thinking routines reveals why they are so effective in educational settings. When students repeatedly engage with structured thinking processes, they develop what psychologists call 'procedural fluency' - the ability to carry out thinking strategies efficiently and accurately. This automaticity allows students to focus their mental energy on the content and concepts being explored rather than on remembering how to think about them. Neuroscientific research supports this, showing that repeated use of thinking patterns strengthens neural pathways, making complex reasoning more accessible to learners of all abilities.

In practical terms, this means that a Year 3 student using 'Think-Pair-Share' for the tenth time can concentrate fully on their mathematical reasoning, whilst a Year 10 student applying 'What Makes You Say That?' can examine deeper into textual analysis without cognitive overload. Teachers consistently report that after just a few weeks of regular implementation, students begin to use these thinking moves independently, asking themselves probing questions and seeking evidence for their ideas even when not prompted to do so.

Thinking routines fall into distinct categories, each designed to cultivate specific cognitive processes and deepen student understanding. Understanding routines help learners explore ideas, uncover assumptions, and make thinking visible through structured inquiry. Meanwhile, truth and fairness routines develop critical evaluation skills, encouraging students to examine evidence, consider multiple perspectives, and assess the reliability of sources.

Creative thinking routines creates innovation and original thought by providing scaffolds for brainstorming, generating alternatives, and exploring possibilities. These complement dilemma routines, which guide students through complex decision-making processes and ethical considerations. Ron Ritchhart's research demonstrates that this categorisation helps educators select appropriate routines based on their learning objectives, whether developing analytical skills, creative problem-solving, or metacognitive awareness.

Effective classroom practice involves matching routine types to curriculum goals and student needs. For instance, understanding routines like "See-Think-Wonder" work particularly well when introducing new concepts, whilst truth and fairness routines such as "Circle of Viewpoints" enhance critical analysis of historical events or literary texts. By deliberately choosing routines from different categories throughout a unit, teachers create a comprehensive thinking framework that supports both content mastery and cognitive development.

Understanding routines focus on building comprehension and encouraging careful observation. Beyond the basic 'See-Think-Wonder', routines like 'Zoom In' help students examine details methodically, whilst 'Circle of Viewpoints' encourages perspective-taking. These routines are particularly effective in humanities subjects where interpretation and multiple perspectives are crucial.

Synthesis routines help students connect ideas and identify patterns. 'Connect-Extend-Challenge' pushes learners to link new information with prior knowledge, extend their thinking, and identify points of confusion or disagreement. The '3-2-1 Bridge' routine captures thinking before and after learning, making knowledge construction visible to both teacher and student.

Creative thinking routines like 'What Makes You Say That?' demand evidence-based reasoning, whilst 'Step Inside' encourages empathetic thinking. Truth and fairness routines, including 'Tug of War' and 'Options-Explode', help students examine multiple sides of complex issues and consider various solutions to problems.

When selecting thinking routines for classroom implementation, consider your learning objectives and the cognitive skills you want to develop. Understanding routines work exceptionally well as lesson openers, creating curiosity and engagement from the start. For instance, 'Think-Puzzle-Explore' can transform a potentially mundane topic introduction into an investigation, with students generating their own questions to guide learning.

Synthesis routines prove most valuable during and after learning experiences, helping students consolidate understanding and make meaningful connections. The key to successful implementation lies in consistent use rather than variety, students develop deeper metacognitive awareness when they become familiar with routine structures, allowing them to focus entirely on the thinking process rather than procedural confusion.

See-Think-Wonder stands as one of the most versatile thinking routines, developed by Harvard's Project Zero team. This three-step process encourages students to observe carefully (See), make interpretations based on evidence (Think), and generate questions for further inquiry (Wonder). Research by Ron Ritchhart demonstrates how this routine develops both critical thinking skills and curiosity, making it particularly effective across subjects from analysing historical photographs to examining scientific phenomena.

Think-Pair-Share uses collaborative learning to deepen individual understanding. Students first process information independently, then discuss their thoughts with a partner before sharing with the larger group. This scaffolded approach aligns with Lev Vygotsky's zone of proximal development, allowing learners to refine their thinking through peer interaction whilst building confidence before contributing to whole-class discussions.

In practice, these routines work best when teachers model the thinking process explicitly and provide adequate wait time for reflection. Begin with simpler content to establish the routine's structure, then gradually apply it to more complex material. The key lies in consistency: regular use transforms these frameworks from novel activities into natural habits of mind that students apply independently across learning contexts.

These routines prove essential because they transform abstract thinking processes into concrete, repeatable structures that students can internalise and apply independently. Unlike traditional questioning approaches that often favour confident speakers, thinking routines create equitable participation opportunities. The predictable frameworks reduce cognitive load, allowing students to focus on content rather than process, which particularly benefits learners with additional needs or those developing English proficiency.

Successful classroom implementation requires consistent modelling and gradual release of responsibility. Teachers might begin by posting visual prompts for each routine, explicitly narrating their own thinking during demonstrations, and celebrating when students use the structures spontaneously in discussions. The key lies in patience - students need multiple exposures before routines become automatic thinking tools rather than teacher-directed activities.

When embedded systematically, these routines cultivate a classroom culture where thinking becomes visible and valued. Students begin questioning each other's reasoning constructively, building on ideas collectively, and reflecting on their learning journey without prompting. This metacognitive awareness transforms passive recipients into active thinkers who can articulate what they know and how they came to know it.

Successful implementation of thinking routines requires gradual introduction and consistent practice rather than overwhelming students with multiple new frameworks simultaneously. Begin with one routine that aligns naturally with your existing curriculum, modelling the process explicitly whilst thinking aloud to demonstrate metacognitive reasoning. As Harvard's Project Zero research suggests, routines become most effective when students internalise the underlying thinking patterns, transforming what initially feels structured into fluid intellectual habits.

The key to embedding routines lies in creating a classroom culture that values thinking processes as much as final answers. Establish clear expectations by displaying routine steps visually, allowing adequate processing time, and celebrating thoughtful reasoning over quick responses. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that students need sufficient mental capacity to engage deeply with content, so reduce extraneous cognitive burden by maintaining consistent routine structures whilst varying the subject matter.

Monitor implementation success through observation of student discourse and self-reflection. When routines are working effectively, you'll notice students naturally using the language and questioning patterns independently, asking follow-up questions that extend beyond surface-level responses. Document these moments of transfer, as they indicate that thinking routines are achieving their ultimate purpose: developing students' capacity for autonomous, critical thinking across diverse contexts.

Successful implementation requires careful attention to classroom culture and student preparation. Begin by explicitly teaching the routine steps, modelling your own thinking process, and providing sentence starters or thinking stems to support student responses. For example, when introducing 'See-Think-Wonder', offer phrases like 'I notice..', 'This makes me think..', or 'I wonder why..' to help students articulate their thoughts.

Timing and pacing are crucial for success. Allow sufficient think time, particularly for understanding routines where rushed responses undermine the purpose. Research by cognitive scientist Mary Budd Rowe shows that increasing wait time from three to seven seconds dramatically improves response quality and participation rates. Build in processing breaks during longer routines to prevent cognitive overload.

Documentation enhances the impact of thinking routines significantly. Use visible thinking strategies like anchor charts to record student thinking, creating a classroom environment where ideas are valued and revisited. Digital tools can capture thinking for reflection and assessment, but avoid letting technology overshadow the thinking process itself.

Assessing learning through thinking routines requires a shift from traditional content-focused evaluation to process-oriented observation that captures students' developing cognitive abilities. Rather than simply measuring what students know, educators must examine how students think, reason, and apply their understanding across diverse contexts. This approach aligns with Dylan Wiliam's research on formative assessment, which emphasises the importance of gathering evidence about student thinking to inform instructional decisions.

Effective assessment strategies include documenting students' verbal contributions during routine discussions, analysing written reflections that reveal metacognitive development, and observing collaborative problem-solving processes. Teachers can create simple rubrics that focus on the quality of questions students ask, their ability to build upon others' ideas, and their willingness to revise thinking based on new evidence. Portfolio collections of student work over time provide particularly valuable insights into growth patterns.

The most powerful assessment occurs when students become partners in evaluating their own learning journey. Encourage learners to maintain thinking journals, conduct peer feedback sessions, and regularly reflect on which routines enhance their understanding most effectively. This self-assessment approach not only provides authentic evidence of growth but also strengthens students' metacognitive awareness, creating a sustainable cycle of reflective learning that extends far beyond individual classroom activities.

Successful implementation of thinking routines requires careful consideration of students' cognitive development and processing capabilities. Jerome Bruner's developmental theory suggests that learners progress through distinct stages, from concrete operational thinking in primary years to abstract reasoning in secondary education. This progression directly impacts which thinking routines will be most effective: younger learners benefit from visual and tactile approaches like "See-Think-Wonder" or "Chalk Talk," whilst older students can engage with more complex metacognitive strategies such as "What Makes You Say That?" or "Circle of Viewpoints."

Primary educators should focus on routines that scaffold thinking through concrete representations and collaborative discussion. Simple structures like "I Used to Think.. Now I Think" work effectively when supported by drawings, manipulatives, or shared experiences. Secondary practitioners can introduce routines requiring greater abstraction and independent reflection, building students' capacity for autonomous critical thinking. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates why age-appropriate selection matters: overwhelming young learners with complex thinking processes can actually inhibit deeper understanding rather than promote it.

The key lies in gradual progression and responsive adaptation. Begin each academic year assessing students' comfort with metacognitive language, then systematically introduce routines that stretch their thinking whilst remaining accessible. This developmental approach ensures thinking routines become genuine tools for learning rather than merely procedural exercises.

The research foundation for thinking routines is robust and spans over two decades of educational investigation. Ron Ritchhart and David Perkins from Harvard's Project Zero have conducted extensive studies demonstrating that structured thinking routines significantly enhance students' metacognitive awareness and critical thinking capabilities. Their longitudinal research across diverse classroom settings shows that students who regularly engage with thinking routines develop stronger analytical skills and demonstrate improved ability to transfer learning across subjects.

Neurocognitive research further supports these findings, with studies indicating that thinking routines create optimal conditions for deep learning by reducing extraneous cognitive load whilst focusing attention on essential thinking processes. Research by Swartz and Parks reveals that students using thinking routines show measurable gains in reasoning quality and demonstrate increased confidence in expressing complex ideas. Particularly significant is evidence showing that these benefits persist over time, suggesting that thinking routines establish lasting cognitive habits rather than temporary skill improvements.

Classroom-based research consistently demonstrates that thinking routines enhance student engagement across all ability levels. Teachers report that previously reluctant learners become more willing to contribute when provided with structured thinking frameworks, whilst high-achieving students develop greater depth in their reasoning. This evidence base provides compelling justification for systematic implementation of thinking routines as a core pedagogical strategy.

In a Year 5 science lesson exploring states of matter, teacher Sarah Mitchell implemented the See-Think-Wonder routine with remarkable results. Students observed ice melting in different conditions, systematically recording what they noticed, their initial hypotheses, and questions that emerged. Rather than rushing to explanations, this structured approach allowed pupils to develop genuine curiosity about molecular behaviour and heat transfer, with many spontaneously connecting observations to previous learning about particles.

Meanwhile, secondary English teacher James Chen uses Connect-Extend-Challenge to deepen literary analysis. After reading Macbeth, students connect themes to contemporary issues, extend Shakespeare's ideas to modern contexts, and challenge assumptions about power and ambition. This routine transforms passive reading into active meaning-making, with pupils demonstrating sophisticated critical thinking that extends well beyond plot comprehension.

Mathematics presents equally powerful opportunities, as demonstrated by Year 8 teacher Priya Patel's implementation of What Makes You Say That? during problem-solving sessions. When students propose solutions to complex word problems, peers respectfully probe their reasoning using this routine's framework. David Perkins' research on visible thinking confirms that such structured questioning develops both mathematical reasoning and metacognitive awareness, helping students recognise and articulate their thought processes.

Even the most well-intentioned thinking routines can falter when predictable implementation challenges arise. Student resistance often emerges when learners feel uncertain about open-ended questioning or fear giving 'wrong' answers. To counter this, establish psychological safety by celebrating partial thinking and modelling your own thought processes aloud. When students observe teachers genuinely wrestling with complex ideas, they become more willing to engage in visible thinking themselves.

Time constraints represent another common obstacle, particularly when curriculum pressures mount. However, John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that investing time in metacognitive awareness actually accelerates learning by helping students process information more efficiently. Start with brief, two-minute routines like 'Think-Pair-Share' before progressing to more elaborate structures. Remember that thinking routines replace rather than add to existing activities.

Maintaining consistent engagement requires strategic variety and purposeful implementation. Rotate between different routines to prevent staleness, but avoid overwhelming students with too many new structures simultaneously. Focus on mastering two or three routines thoroughly before introducing additional approaches. Most importantly, make thinking visible by capturing student responses on wall displays, learning journals, or digital platforms, creating a classroom culture where deeper understanding becomes the expected norm rather than an occasional occurrence.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-routines-for-deeper-understanding#article","headline":"Thinking Routines for Deeper Understanding","description":"Discover thinking routines: simple question sequences that reveal student thinking and deepen learning, with practical tips for embedding them across subjects.","datePublished":"2025-06-13T15:25:45.605Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-routines-for-deeper-understanding"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/695021267c71dd684b83c301_9c84ku.webp","wordCount":2676},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-routines-for-deeper-understanding#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Thinking Routines for Deeper Understanding","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-routines-for-deeper-understanding"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-routines-for-deeper-understanding#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is Project Zero's Thinking Routines Toolbox?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The thinking routines toolbox defines these routines as sequences of questions or steps that guide students in their thought processes. It groups them into Core Thinking and Possibilities, along with other methods for organising and combining ideas."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are thinking routines and how do they differ from traditional question-and-answer methods?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Thinking routines are structured sequences of questions or steps developed by Harvard's Project Zero that guide"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers begin implementing thinking routines in their classrooms without feeling overwhelmed?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Start with one or two core routines like See-Think-Wonder or Think-Puzzle-Explore, which can be adapted to any subject or year group. These simple sequences become part of classroom culture over time, and teachers can gradually expand their toolkit as they become more comfortable with making student"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What specific benefits do thinking routines provide for student engagement and learning outcomes?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Thinking routines build critical thinking skills, develop"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Can you provide practical examples of how thinking routines work in different subjects?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"See-Think-Wonder works brilliantly when introducing new content in any subject, whilst Step Inside helps students adopt different perspectives in history or literature. Claim-Support-Question strengthens argumentation in English or science, and Compass Points helps evaluate proposals or ideas by lis"}}]}]}