Cognitive Biases

Explore practical steps to identify and overcome common cognitive biases, enhancing decision-making and critical thinking.

Explore practical steps to identify and overcome common cognitive biases, enhancing decision-making and critical thinking.

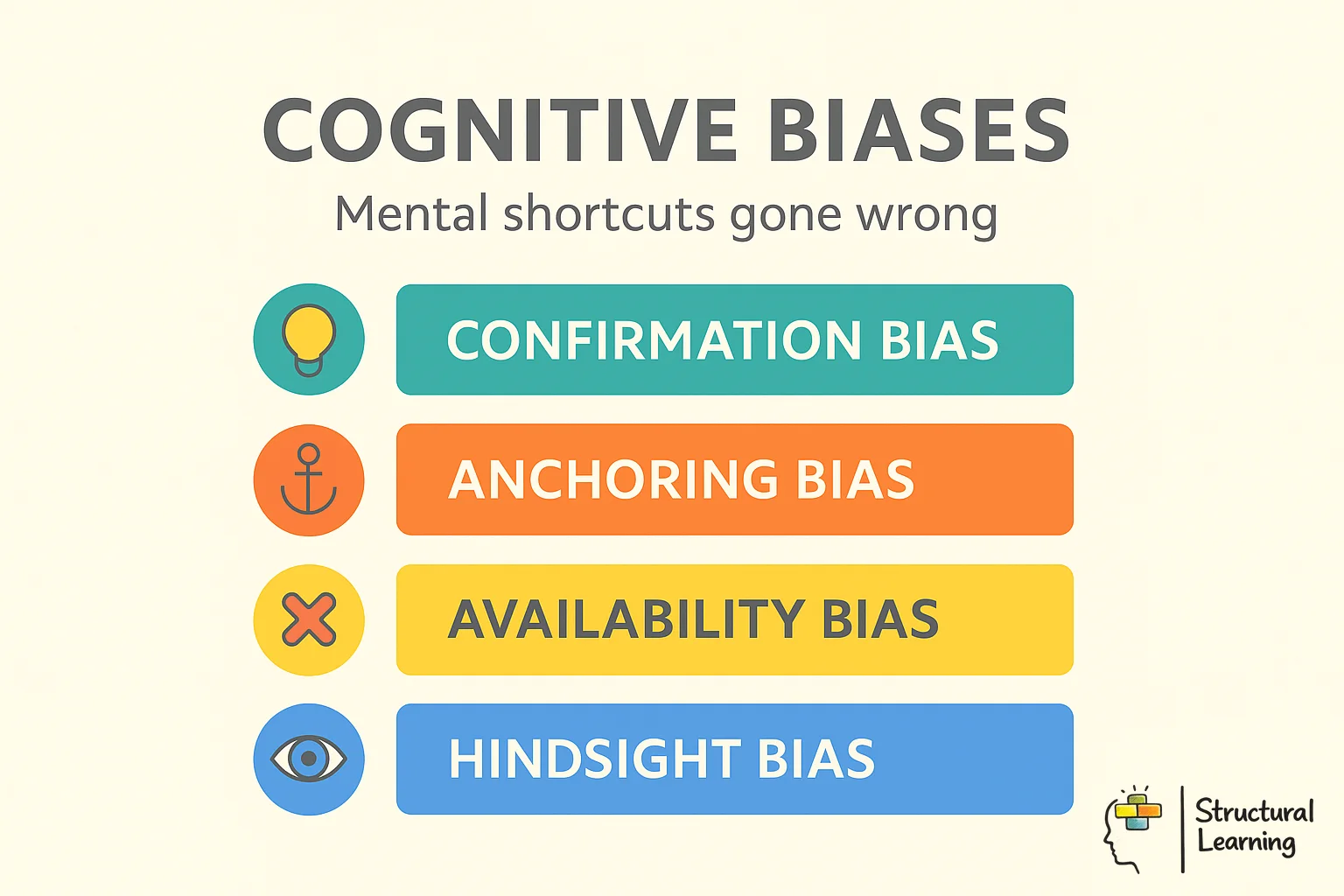

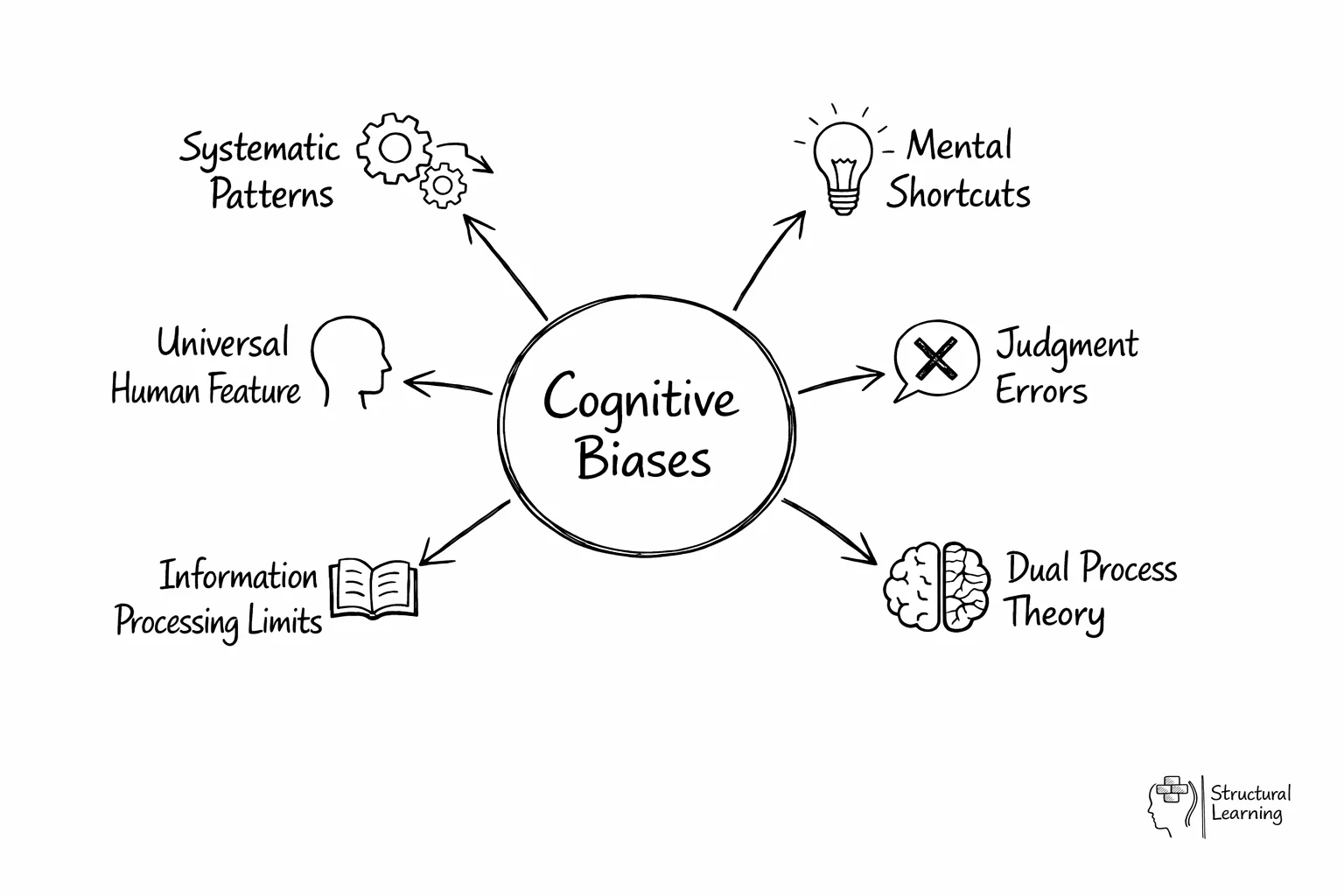

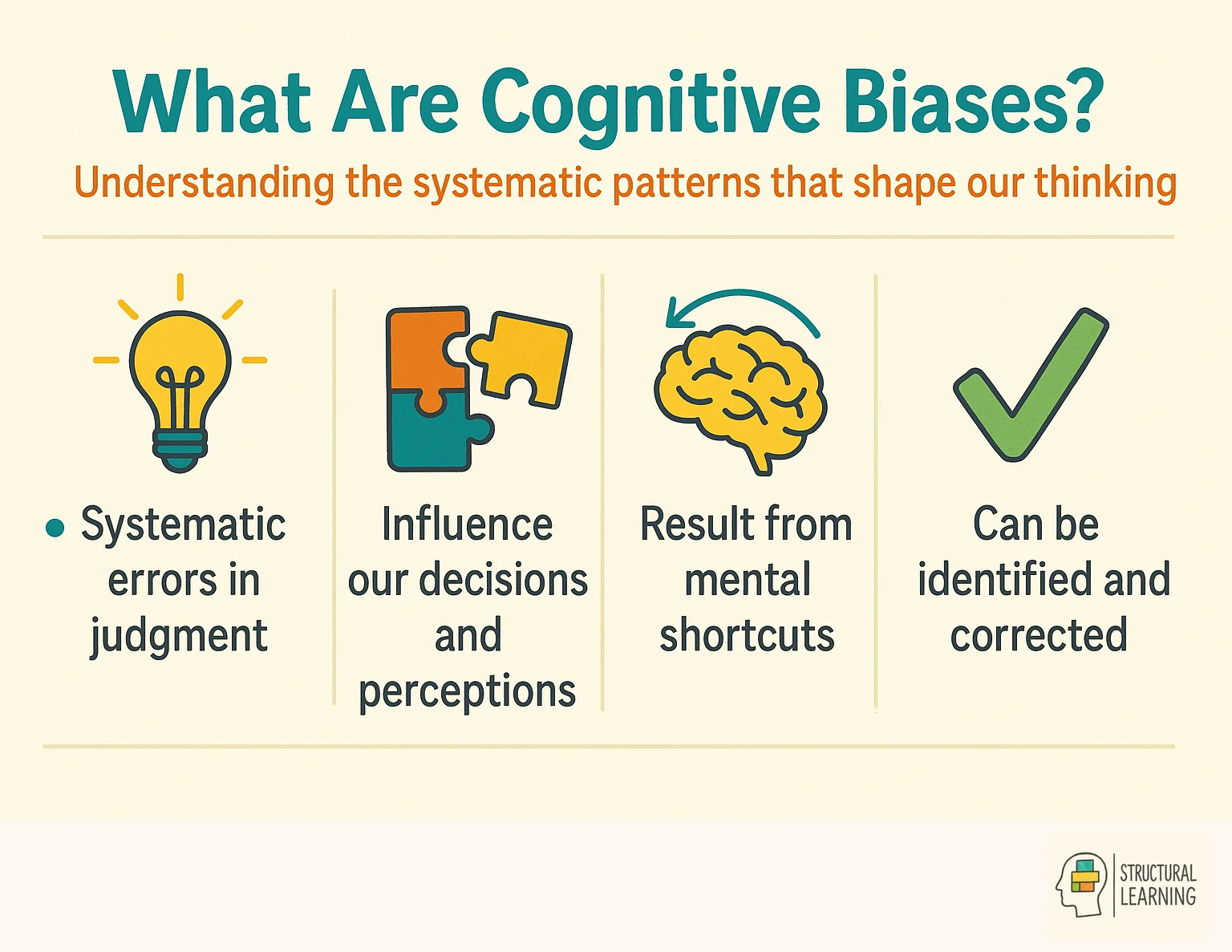

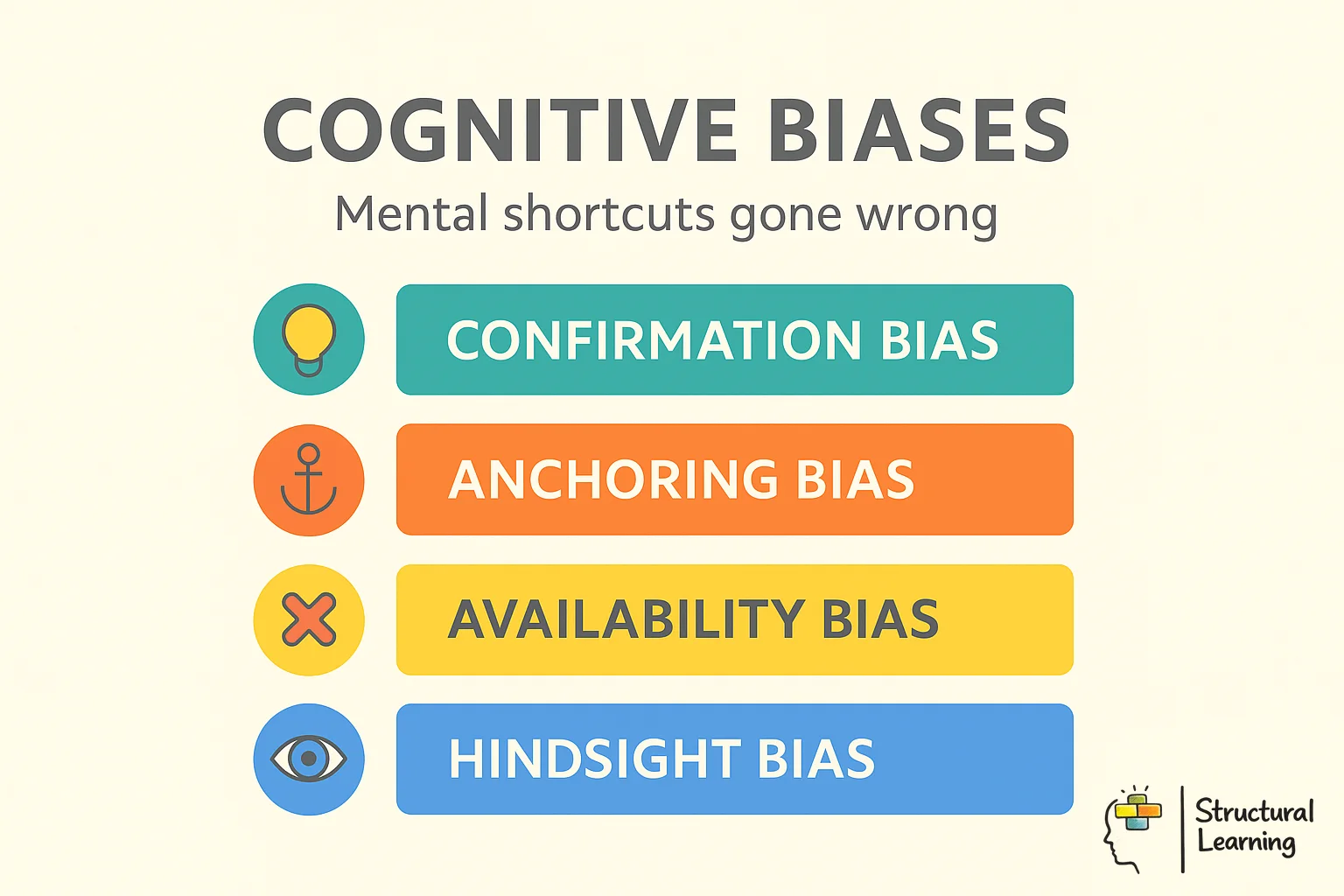

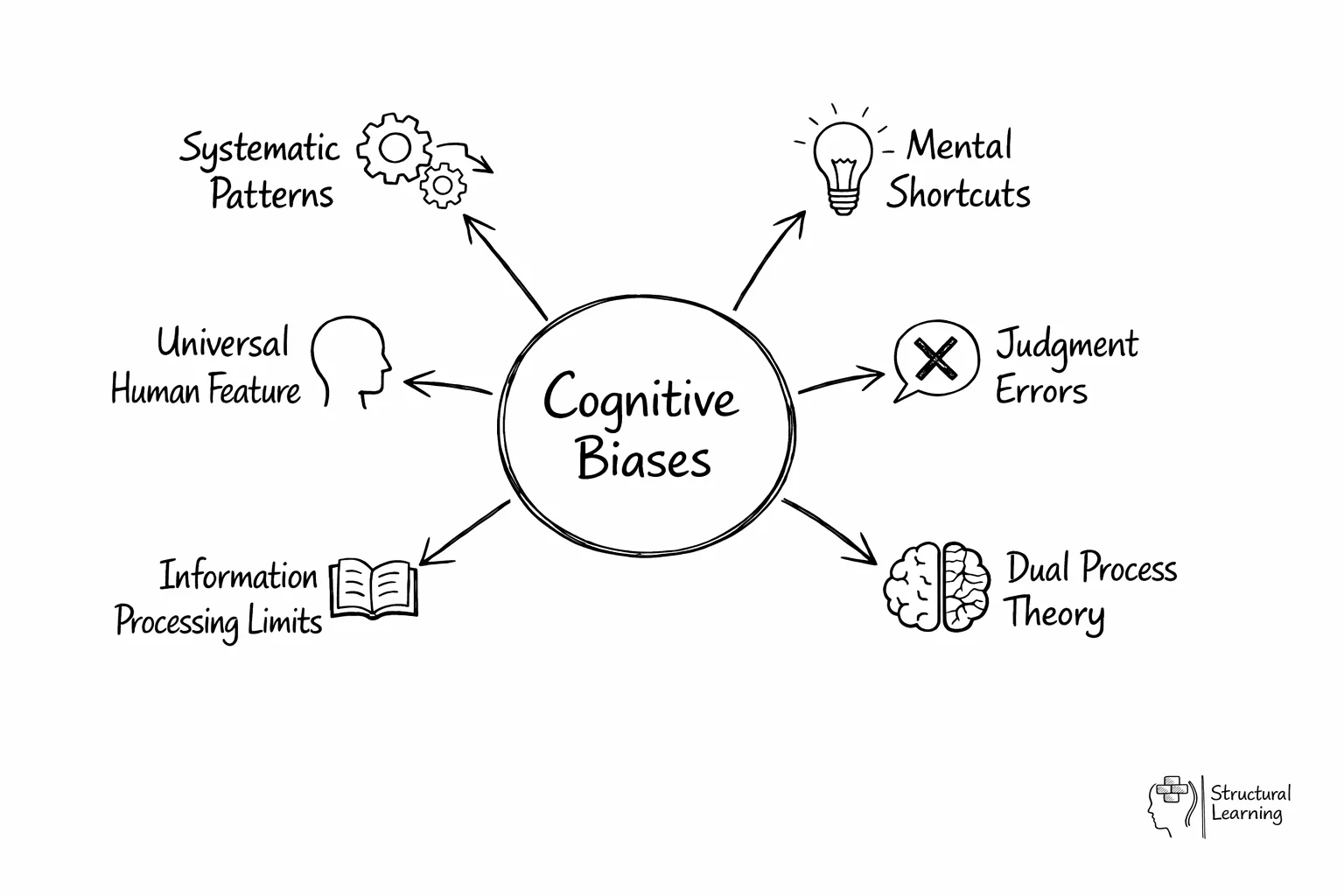

Cognitive biases are systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, where inferences about other people and situations may be drawn in an illogical fashion. Individuals create their own "subjective reality" from their perception of the input.

An individual's construction of social reality, not the objective input, may dictate their behaviour in the social world. Thus, cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, or what is broadly called irrationality.

Although cognitive biases are a pervasive aspect of human cognition, they are not necessarily all maladaptive. They can be seen as a byproduct of the brain's attempt to simplify information processing.

They are often a result of the brain's limited information processing capacity and can be seen as mental shortcuts that usually get us where we need to go, but sometimes lead us astray. This phenomenon is well explained by dual process theory, which distinguishes between fast, automatic thinking and slower, more deliberate cognitive processes.

Here are three key points that summarise what cognitive biases are:

Throughout this article, we will examine into various biases, such as the self-serving bias, which describes our tendency to attribute successes to internal factors and failures to external ones, and the actor-observer bias, where we tend to attribute other people's actions to their character but our own actions to our circumstances.

We will also explore how these biases influence our view of rationality and how common biases can lead to a blind spot in our own self-awareness. From the fundamental attribution error outlined in social psychology to the insights from positive psychology on optimism bias, we'll provide a deeper understanding of these concepts, informed by sources like the APA Dictionary of Psychology and experimental social psychology research.

The implications of cognitive biases extend beyond individual interactions to influence broader educational practices and policies. For example, the availability heuristic might lead educators to overemphasise recent events or vivid examples when designing curricula, potentially skewing students' understanding of historical patterns or scientific principles. Meanwhile, anchoring bias can affect assessment practices, where teachers' initial impressions of student ability influence subsequent marking and feedback, creating self-fulfiling prophecies that impact long-term academic progress.

Practical strategies for addressing cognitive biases in educational settings include implementing structured reflection practices, using rubrics to standardise assessment criteria, and encouraging peer review processes. Teachers can model metacognitivethinking by explicitly discussing their own decision-making processes and potential biases with students. Additionally, incorporating diverse perspectives into lesson planning and actively seeking disconfirming evidence when evaluating student work can help counteract the natural tendency towards biased thinking whilst promoting more inclusive and accurate educational practices.

Psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky pioneered the study of cognitive biases in the 1970s through their groundbreaking research on judgment and decision-making. Their work revealed that humans consistently make predictable errors in thinking, which earned Kahneman the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002. This research fundamentally changed how we understand human rationality and decision-making processes.

Cognitive biases were first identified and studied by a number of influential psychologists, each of whom made significant contributions to the field. This list showcases key researchers from the field of cognitive biases, each contributing a building block to our current understanding of the topic.

As the article progresses, we will examine deeper into each bias, exploring its origins, implications, and real-world applications, solidifying the reader's comprehension of this complex field.

1. Peter Wason (1924-2003): A cognitive psychologist at University College London, Wason was instrumental in identifying various logical fallacies and cognitive biases, notably the confirmation bias through his eponymous Wason selection task. His research in the 1960s demonstrated the human tendency to seek information that confirms pre-existing beliefs.

2. Robert H. Thouless (1894-1984): Thouless contributed to the early exploration of cognitive biases with his work on wishful thinking and the distortion of evidence. He was a psychologist at Cambridge University Press, and his research in the 1950s examined into the psychology of judgment and decision-making.

3. Amos Tversky (1937-1996) & Daniel Kahneman (b. 1934): Tversky and Kahneman, through their work published by Oxford University Press and the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, transformed the understanding of human judgment. In the 1970s, they developed prospect theory and uncovered heuristics such as the availability and representativeness biases, fundamentally shaping the field of cognitive science.

4. Gerd Gigerenzer (b. 1947): Gigerenzer's research focuses on the role of heuristics in decision-making. He has contributed to the understanding of how people make decisions under uncertainty and is known for his critique of the work of Kahneman and Tversky, emphasising the adaptive nature of heuristics.

5. Daniel L. Schacter (b. 1952): Schacter's work at Harvard University has been pivotal in exploring memory biases, especially false memories. His research in cognitive psychology and cognitive neuroscience has shed light on the mechanisms of memory distortion and their implications for cognitive biases.

6. Keith E. Stanovich (b. 1950): Stanovich's work on the Rationality Quotient has been significant in understanding how critical thinkingabilities relate to cognitive bias susceptibility. His research explores the connection between cognitive abilities and rational decision-making, showing how enhanced thinking skills can help mitigate the effects of certain biases. This understanding has important implications for questioning techniques in educational settings, where teachers can help students recognise and overcome their own cognitive limitations. Additionally, his work connects to broader concepts in social cognitive theories that examine how individuals process information in social contexts.

7. Richard Nisbett: Nisbett's contributions to understanding cultural differences in cognition have revealed how cognitive biases can vary across different cultural contexts. His work demonstrates that while some biases appear universal, others are influenced by cultural background and educational experiences. This research has implications for inclusive educationpractices, as educators must consider how students from diverse backgrounds may approach problems differently. Understanding these differences is also crucial for feedback delivery, as teachers need to adapt their communication styles to be effective across cultural boundaries.

8. Carol Dweck: Though primarily known for her work on mindset theory, Dweck's research intersects with cognitive biases, particularly around how people interpret success and failure. Her findings relate to social-emotional learning frameworks, as understanding one's own cognitive tendencies can improve emotional regulation and social interactions. This understanding becomes especially important when working with students who have special educational needs, as cognitive biases can affect how both teachers and students perceive learning challenges and capabilities.

The study of cognitive biases continues to evolve, with researchers exploring how these mental shortcuts affect everything from classroom attention patterns to teacher expectations. Modern research increasingly examines the relationship between cognitive biases and cognitive dissonance, particularly in educational contexts where students must confront information that challenges their existing beliefs. This research also connects to therapeutic approaches like Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy and understanding Cognitive Distortions, which help individuals recognise and address problematic thinking patterns. Furthermore, the developmental aspect of cognitive biases is being studied in relation to Cognitive Development in Infancy, helping researchers understand when and how these thinking patterns emerge in human development.

In educational contexts, several cognitive biases significantly impact both teaching effectiveness and student learning outcomes. The confirmation bias leads educators to favour information that supports their existing beliefs about student capabilities, potentially creating self-fulfiling prophecies. Daniel Kahneman's research on the availability heuristic reveals how teachers often judge student performance based on the most memorable recent examples rather than comprehensive assessment data. Meanwhile, the anchoring bias causes educators to rely too heavily on initial impressions or test scores when evaluating ongoing student progress.

The halo effect represents another critical bias in educational settings, where a student's performance in one area inappropriately influences judgements about their abilities in unrelated subjects. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates how the overconfidence bias can lead teachers to present information too quickly, assuming students have absorbed previous concepts more thoroughly than they actually have. Additionally, attribution bias affects how educators interpret student struggles, sometimes attributing difficulties to laziness rather than genuine learning barriers.

Recognising these systematic errors enables more objective decision-making in classroom management and assessment. Practical strategies include maintaining detailed records to counter availability bias, using structured rubrics to minimise halo effects, and regularly questioning initial assumptions about student capabilities. By developing awareness of these mental shortcuts, educators can create more equitable learning environments and make evidence-based instructional decisions.

Cognitive biases significantly shape both learning outcomes and teaching effectiveness in educational contexts, often operating below the threshold of conscious awareness. Students frequently fall victim to the confirmation bias, seeking information that supports their existing beliefs whilst dismissing contradictory evidence. This tendency can impede critical thinking development and create resistance to new concepts that challenge preconceived notions. Similarly, the Dunning-Kruger effect leads students with limited knowledge to overestimate their competence, whilst more capable learners may underestimate their abilities.

Educators themselves are not immune to these systematic errors in thinking. The halo effect can cause teachers to let one positive or negative student characteristic influence their overall assessment, whilst anchoring bias may lead to unfair grading based on initial impressions or previous performance. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates how confirmation bias in lesson planning can result in teachers overlooking students' actual learning needs in favour of familiar instructional methods.

Recognising these biases enables educators to implement targeted strategies that promote more objective learning environments. Encouraging students to actively seek disconfirming evidence, using anonymous peer assessment, and implementing structured reflection protocols can help mitigate bias effects. Regular self-reflection on grading patterns and seeking colleague feedback on assessment decisions further supports fair, evidence-based educational practices.

Cognitive biases manifest daily in classroom environments, influencing both teaching decisions and student learning. Teachers often fall victim to confirmation bias when they form early impressions of students' abilities, subsequently noticing evidence that confirms these expectations whilst overlooking contradictory information. Similarly, the halo effect leads educators to judge a student's work more favourably if they performed well previously, creating systematic errors in assessment that can significantly impact educational outcomes.

Students themselves demonstrate predictable cognitive shortcuts that affect their learning. The availability heuristic causes them to overestimate the importance of recently studied topics when revising, leading to imbalanced preparation. Additionally, overconfidence bias frequently emerges when students mistake familiarity with material for genuine understanding, particularly after re-reading notes without active recall practice.

Recognising these patterns enables more effective educational practices. Teachers can combat confirmation bias by deliberately seeking evidence that challenges their initial student assessments, whilst implementing anonymous marking reduces halo effects. For students, educators can introduce metacognitive strategies that help learners identify when they're using mental shortcuts inappropriately, such as teaching them to distinguish between recognition and recall when self-assessing their knowledge.

Reducing cognitive bias in educational contexts requires deliberate intervention strategies that acknowledge our mental shortcuts whilst promoting more objective decision-making. Daniel Kahneman's research on System 1 and System 2 thinking suggests that slowing down our automatic responses allows for more considered judgements. Teachers can implement this by establishing reflection protocols before making significant decisions about student assessment, grouping, or intervention strategies.

Structured evaluation frameworks prove particularly effective in combating confirmation bias and the halo effect. Create standardised rubrics that focus on specific, observable behaviours rather than general impressions. When assessing student work, consider reviewing submissions anonymously where possible, or evaluate one criterion across all students before moving to the next. Collaborative decision-making with colleagues also helps counteract individual biases, as diverse perspectives challenge assumptions and highlight blind spots.

Regular self-monitoring strengthens bias awareness over time. Keep brief records of your initial impressions of new students, then revisit these notes periodically to identify patterns in your thinking. Professional learning communities can establish 'bias checks' during team meetings, where educators explicitly question whether cognitive shortcuts might be influencing their judgements. This systematic approach transforms bias recognition from an abstract concept into practical classroom wisdom.

Assessment and grading represent perhaps the most consequential areas where cognitive biases can influence student outcomes. The halo effect leads teachers to allow one positive trait or previous performance to colour their evaluation of subsequent work, whilst the contrast effect causes the same piece of work to be graded differently depending on what was marked immediately before it. Research by Rosenthal and Jacobson's landmark study on teacher expectations demonstrates how preconceived notions about student ability become self-fulfiling prophecies, systematically affecting both assessment practices and student achievement.

The anchoring bias proves particularly problematic in educational contexts, where teachers unconsciously use irrelevant information as reference points for grading decisions. Previous grades, knowledge of family circumstances, or even a student's physical appearance can serve as anchors that skew objective evaluation. Additionally, the confirmation bias leads educators to interpret ambiguous responses in ways that confirm their existing beliefs about a student's capabilities, potentially overlooking genuine improvement or misinterpreting creative thinking.

To combat these systematic errors, implement blind marking where feasible, removing student names and identifying information during assessment. Establish clear rubrics before marking begins, and consider marking all responses to question one before moving to question two, rather than completing entire papers sequentially. Regular calibration exercises with colleagues help maintain consistency and reveal unconscious biases in your grading patterns.

Cognitive biases are systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, where inferences about other people and situations may be drawn in an illogical fashion. Individuals create their own "subjective reality" from their perception of the input.

An individual's construction of social reality, not the objective input, may dictate their behaviour in the social world. Thus, cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, or what is broadly called irrationality.

Although cognitive biases are a pervasive aspect of human cognition, they are not necessarily all maladaptive. They can be seen as a byproduct of the brain's attempt to simplify information processing.

They are often a result of the brain's limited information processing capacity and can be seen as mental shortcuts that usually get us where we need to go, but sometimes lead us astray. This phenomenon is well explained by dual process theory, which distinguishes between fast, automatic thinking and slower, more deliberate cognitive processes.

Here are three key points that summarise what cognitive biases are:

Throughout this article, we will examine into various biases, such as the self-serving bias, which describes our tendency to attribute successes to internal factors and failures to external ones, and the actor-observer bias, where we tend to attribute other people's actions to their character but our own actions to our circumstances.

We will also explore how these biases influence our view of rationality and how common biases can lead to a blind spot in our own self-awareness. From the fundamental attribution error outlined in social psychology to the insights from positive psychology on optimism bias, we'll provide a deeper understanding of these concepts, informed by sources like the APA Dictionary of Psychology and experimental social psychology research.

The implications of cognitive biases extend beyond individual interactions to influence broader educational practices and policies. For example, the availability heuristic might lead educators to overemphasise recent events or vivid examples when designing curricula, potentially skewing students' understanding of historical patterns or scientific principles. Meanwhile, anchoring bias can affect assessment practices, where teachers' initial impressions of student ability influence subsequent marking and feedback, creating self-fulfiling prophecies that impact long-term academic progress.

Practical strategies for addressing cognitive biases in educational settings include implementing structured reflection practices, using rubrics to standardise assessment criteria, and encouraging peer review processes. Teachers can model metacognitivethinking by explicitly discussing their own decision-making processes and potential biases with students. Additionally, incorporating diverse perspectives into lesson planning and actively seeking disconfirming evidence when evaluating student work can help counteract the natural tendency towards biased thinking whilst promoting more inclusive and accurate educational practices.

Psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky pioneered the study of cognitive biases in the 1970s through their groundbreaking research on judgment and decision-making. Their work revealed that humans consistently make predictable errors in thinking, which earned Kahneman the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002. This research fundamentally changed how we understand human rationality and decision-making processes.

Cognitive biases were first identified and studied by a number of influential psychologists, each of whom made significant contributions to the field. This list showcases key researchers from the field of cognitive biases, each contributing a building block to our current understanding of the topic.

As the article progresses, we will examine deeper into each bias, exploring its origins, implications, and real-world applications, solidifying the reader's comprehension of this complex field.

1. Peter Wason (1924-2003): A cognitive psychologist at University College London, Wason was instrumental in identifying various logical fallacies and cognitive biases, notably the confirmation bias through his eponymous Wason selection task. His research in the 1960s demonstrated the human tendency to seek information that confirms pre-existing beliefs.

2. Robert H. Thouless (1894-1984): Thouless contributed to the early exploration of cognitive biases with his work on wishful thinking and the distortion of evidence. He was a psychologist at Cambridge University Press, and his research in the 1950s examined into the psychology of judgment and decision-making.

3. Amos Tversky (1937-1996) & Daniel Kahneman (b. 1934): Tversky and Kahneman, through their work published by Oxford University Press and the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, transformed the understanding of human judgment. In the 1970s, they developed prospect theory and uncovered heuristics such as the availability and representativeness biases, fundamentally shaping the field of cognitive science.

4. Gerd Gigerenzer (b. 1947): Gigerenzer's research focuses on the role of heuristics in decision-making. He has contributed to the understanding of how people make decisions under uncertainty and is known for his critique of the work of Kahneman and Tversky, emphasising the adaptive nature of heuristics.

5. Daniel L. Schacter (b. 1952): Schacter's work at Harvard University has been pivotal in exploring memory biases, especially false memories. His research in cognitive psychology and cognitive neuroscience has shed light on the mechanisms of memory distortion and their implications for cognitive biases.

6. Keith E. Stanovich (b. 1950): Stanovich's work on the Rationality Quotient has been significant in understanding how critical thinkingabilities relate to cognitive bias susceptibility. His research explores the connection between cognitive abilities and rational decision-making, showing how enhanced thinking skills can help mitigate the effects of certain biases. This understanding has important implications for questioning techniques in educational settings, where teachers can help students recognise and overcome their own cognitive limitations. Additionally, his work connects to broader concepts in social cognitive theories that examine how individuals process information in social contexts.

7. Richard Nisbett: Nisbett's contributions to understanding cultural differences in cognition have revealed how cognitive biases can vary across different cultural contexts. His work demonstrates that while some biases appear universal, others are influenced by cultural background and educational experiences. This research has implications for inclusive educationpractices, as educators must consider how students from diverse backgrounds may approach problems differently. Understanding these differences is also crucial for feedback delivery, as teachers need to adapt their communication styles to be effective across cultural boundaries.

8. Carol Dweck: Though primarily known for her work on mindset theory, Dweck's research intersects with cognitive biases, particularly around how people interpret success and failure. Her findings relate to social-emotional learning frameworks, as understanding one's own cognitive tendencies can improve emotional regulation and social interactions. This understanding becomes especially important when working with students who have special educational needs, as cognitive biases can affect how both teachers and students perceive learning challenges and capabilities.

The study of cognitive biases continues to evolve, with researchers exploring how these mental shortcuts affect everything from classroom attention patterns to teacher expectations. Modern research increasingly examines the relationship between cognitive biases and cognitive dissonance, particularly in educational contexts where students must confront information that challenges their existing beliefs. This research also connects to therapeutic approaches like Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy and understanding Cognitive Distortions, which help individuals recognise and address problematic thinking patterns. Furthermore, the developmental aspect of cognitive biases is being studied in relation to Cognitive Development in Infancy, helping researchers understand when and how these thinking patterns emerge in human development.

In educational contexts, several cognitive biases significantly impact both teaching effectiveness and student learning outcomes. The confirmation bias leads educators to favour information that supports their existing beliefs about student capabilities, potentially creating self-fulfiling prophecies. Daniel Kahneman's research on the availability heuristic reveals how teachers often judge student performance based on the most memorable recent examples rather than comprehensive assessment data. Meanwhile, the anchoring bias causes educators to rely too heavily on initial impressions or test scores when evaluating ongoing student progress.

The halo effect represents another critical bias in educational settings, where a student's performance in one area inappropriately influences judgements about their abilities in unrelated subjects. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates how the overconfidence bias can lead teachers to present information too quickly, assuming students have absorbed previous concepts more thoroughly than they actually have. Additionally, attribution bias affects how educators interpret student struggles, sometimes attributing difficulties to laziness rather than genuine learning barriers.

Recognising these systematic errors enables more objective decision-making in classroom management and assessment. Practical strategies include maintaining detailed records to counter availability bias, using structured rubrics to minimise halo effects, and regularly questioning initial assumptions about student capabilities. By developing awareness of these mental shortcuts, educators can create more equitable learning environments and make evidence-based instructional decisions.

Cognitive biases significantly shape both learning outcomes and teaching effectiveness in educational contexts, often operating below the threshold of conscious awareness. Students frequently fall victim to the confirmation bias, seeking information that supports their existing beliefs whilst dismissing contradictory evidence. This tendency can impede critical thinking development and create resistance to new concepts that challenge preconceived notions. Similarly, the Dunning-Kruger effect leads students with limited knowledge to overestimate their competence, whilst more capable learners may underestimate their abilities.

Educators themselves are not immune to these systematic errors in thinking. The halo effect can cause teachers to let one positive or negative student characteristic influence their overall assessment, whilst anchoring bias may lead to unfair grading based on initial impressions or previous performance. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates how confirmation bias in lesson planning can result in teachers overlooking students' actual learning needs in favour of familiar instructional methods.

Recognising these biases enables educators to implement targeted strategies that promote more objective learning environments. Encouraging students to actively seek disconfirming evidence, using anonymous peer assessment, and implementing structured reflection protocols can help mitigate bias effects. Regular self-reflection on grading patterns and seeking colleague feedback on assessment decisions further supports fair, evidence-based educational practices.

Cognitive biases manifest daily in classroom environments, influencing both teaching decisions and student learning. Teachers often fall victim to confirmation bias when they form early impressions of students' abilities, subsequently noticing evidence that confirms these expectations whilst overlooking contradictory information. Similarly, the halo effect leads educators to judge a student's work more favourably if they performed well previously, creating systematic errors in assessment that can significantly impact educational outcomes.

Students themselves demonstrate predictable cognitive shortcuts that affect their learning. The availability heuristic causes them to overestimate the importance of recently studied topics when revising, leading to imbalanced preparation. Additionally, overconfidence bias frequently emerges when students mistake familiarity with material for genuine understanding, particularly after re-reading notes without active recall practice.

Recognising these patterns enables more effective educational practices. Teachers can combat confirmation bias by deliberately seeking evidence that challenges their initial student assessments, whilst implementing anonymous marking reduces halo effects. For students, educators can introduce metacognitive strategies that help learners identify when they're using mental shortcuts inappropriately, such as teaching them to distinguish between recognition and recall when self-assessing their knowledge.

Reducing cognitive bias in educational contexts requires deliberate intervention strategies that acknowledge our mental shortcuts whilst promoting more objective decision-making. Daniel Kahneman's research on System 1 and System 2 thinking suggests that slowing down our automatic responses allows for more considered judgements. Teachers can implement this by establishing reflection protocols before making significant decisions about student assessment, grouping, or intervention strategies.

Structured evaluation frameworks prove particularly effective in combating confirmation bias and the halo effect. Create standardised rubrics that focus on specific, observable behaviours rather than general impressions. When assessing student work, consider reviewing submissions anonymously where possible, or evaluate one criterion across all students before moving to the next. Collaborative decision-making with colleagues also helps counteract individual biases, as diverse perspectives challenge assumptions and highlight blind spots.

Regular self-monitoring strengthens bias awareness over time. Keep brief records of your initial impressions of new students, then revisit these notes periodically to identify patterns in your thinking. Professional learning communities can establish 'bias checks' during team meetings, where educators explicitly question whether cognitive shortcuts might be influencing their judgements. This systematic approach transforms bias recognition from an abstract concept into practical classroom wisdom.

Assessment and grading represent perhaps the most consequential areas where cognitive biases can influence student outcomes. The halo effect leads teachers to allow one positive trait or previous performance to colour their evaluation of subsequent work, whilst the contrast effect causes the same piece of work to be graded differently depending on what was marked immediately before it. Research by Rosenthal and Jacobson's landmark study on teacher expectations demonstrates how preconceived notions about student ability become self-fulfiling prophecies, systematically affecting both assessment practices and student achievement.

The anchoring bias proves particularly problematic in educational contexts, where teachers unconsciously use irrelevant information as reference points for grading decisions. Previous grades, knowledge of family circumstances, or even a student's physical appearance can serve as anchors that skew objective evaluation. Additionally, the confirmation bias leads educators to interpret ambiguous responses in ways that confirm their existing beliefs about a student's capabilities, potentially overlooking genuine improvement or misinterpreting creative thinking.

To combat these systematic errors, implement blind marking where feasible, removing student names and identifying information during assessment. Establish clear rubrics before marking begins, and consider marking all responses to question one before moving to question two, rather than completing entire papers sequentially. Regular calibration exercises with colleagues help maintain consistency and reveal unconscious biases in your grading patterns.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cognitive-biases#article","headline":"Cognitive Biases","description":"Explore practical steps to identify and overcome common cognitive biases, enhancing decision-making and critical thinking.","datePublished":"2024-02-06T15:19:19.099Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cognitive-biases"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a35870fde7ce744d97c54_696a35853dd12120d962ea8f_cognitive-biases-infographic.webp","wordCount":4734},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cognitive-biases#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Cognitive Biases","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cognitive-biases"}]}]}