Bystander Effect

Explore the bystander effect, a psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to help in an emergency when others are present.

Explore the bystander effect, a psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to help in an emergency when others are present.

The bystander effect, a term deeply embedded in social psychology, captures the puzzling human tendency to become an unresponsive bystander during emergencies when others are present.

| Increases Intervention | Example | Decreases Intervention | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small group size | One or two witnesses present | Large group size | Many people observing the incident |

| Clear emergency | Obvious signs of distress or danger | Ambiguous situation | Unclear if help is needed |

| Personal responsibility | Being the only witness or directly addressed | Diffusion of responsibility | Assuming someone else will help |

| Competence/training | First aid training or relevant expertise | Lack of skills | Unsure how to help effectively |

| Personal connection | Knowing the victim or shared identity | Anonymity | Being a stranger in a crowd |

This phenomenon, often attributed to a diffusion of responsibility, leads to a decreased likelihood of intervention, as individuals unconsciously assume that someone else will take action (Sun, 2024).

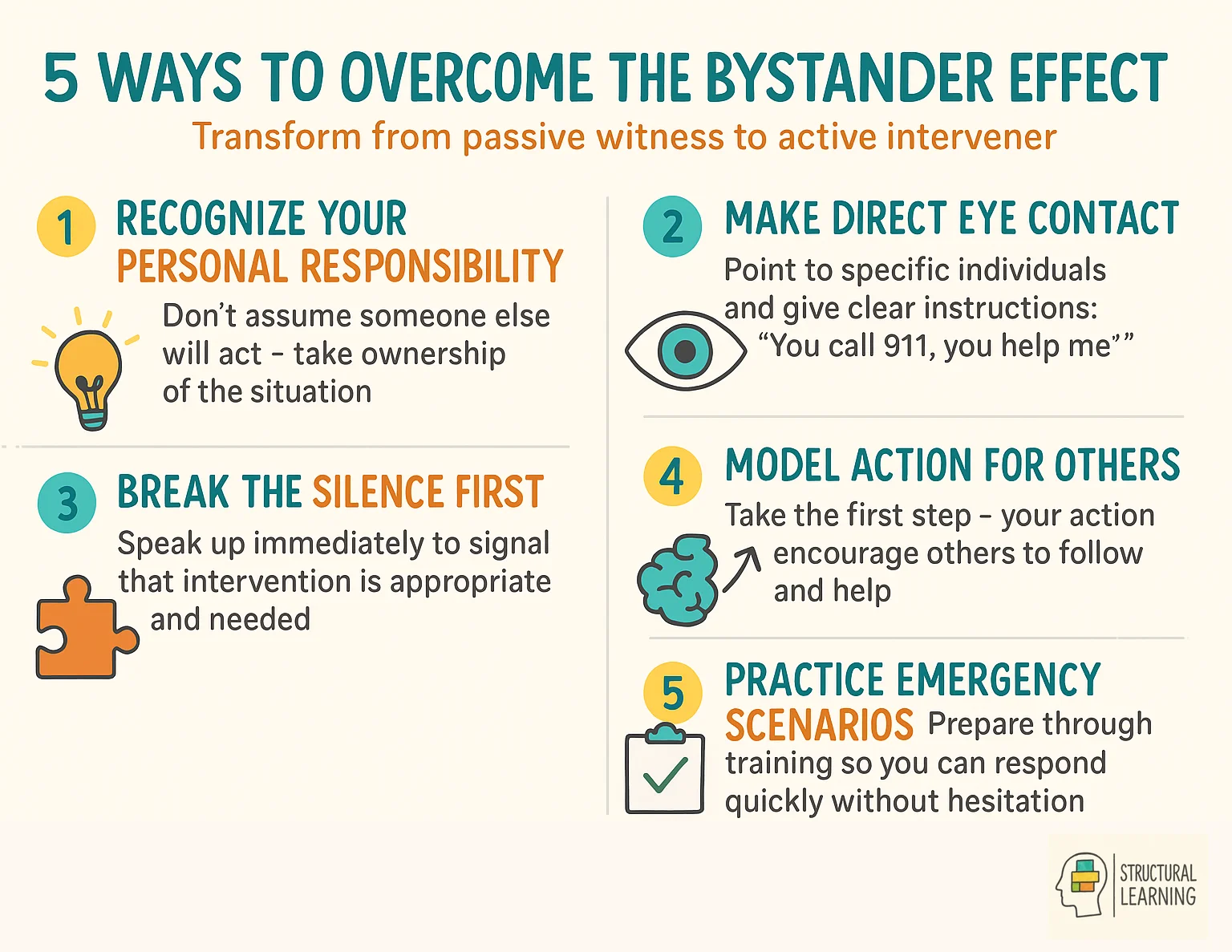

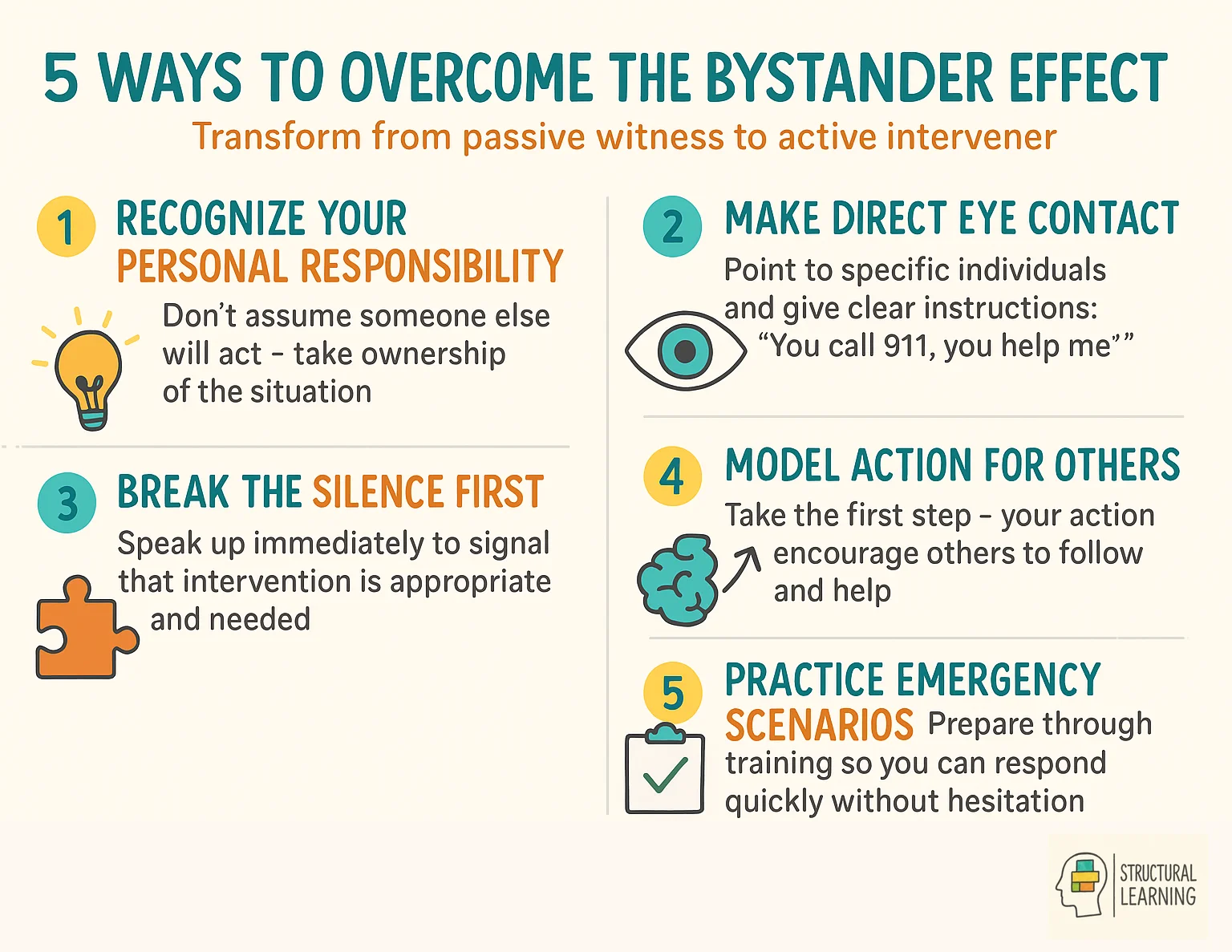

practical strategies to overcome bystander effect and become an active intervener in emergencies" loading="lazy">

practical strategies to overcome bystander effect and become an active intervener in emergencies" loading="lazy">For instance, in a crowded school hallway where bullying is occurring, bystanders may overlook the situation, believing that another person will step in, thereby contributing to a collective inaction (Liu et al., 2022). This highlights implementing targeted classroom management strategies that enable pupils to become active participants rather than passive observers.

This effect was tragically illustrated in the case of Kitty Genovese in 1964, where her brutal attack was witnessed by several individuals who failed to intervene or call for help. This incident not only shocked the public but also ignited a spark in the field of social psychology, leading to extensive research, including studies published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

One relevant statistic that underscores the gravity of this issue is that in situations with more th an five bystanders, the likelihood of intervention drops by over 50%. The bystander effect is not merely a curiosity; it's a profound insight into human behaviour that has real emergency implications in our crowded minds.

Understanding bystander behaviour is crucial in today's interconnected world. It's not just about public self-awareness but about encouraging a sense of res ponsibility on bystander intervention.

Through targeted modelling strategies and targeted education and bystander training, we can challenge the implicit bystander theory that often governs our reactions, enabling individuals to transcend passivity and actively assist those in distress.

Key Insights and Important Facts:

Social influences create the bystander effect through diffusion of responsibility, where individuals assume others will take action, and pluralistic ignorance, where people misinterpret others' inaction as appropriate behaviour. The presence of more people actually reduces individual responsibility and increases conformity to perceived group norms (Jiang, 2023). These psychological mechanisms explain why crowded environments often see less intervention during emergencies or incidents.

The bystander effect, a phenomenon in which individuals are less likely to intervene in emergency situations when other people are present, can be attributed in part to social influences. One key factor contributing to the bystander effect is the diffusion of responsibility.

When faced with an emergency situation, individuals may feel less personally responsible to take action because they assume that someone else will step in and help. This diffusion of responsibility can lead to inaction and a lack of intervention, which is similar to patterns observed in the Dunning-Kruger Effect where cognitive biases affect decision-making.

Social influence also plays a role in the bystander effect. According to social comparison theory, individuals tend to look to others for cues on how to behave in ambiguous situations.

In emergency situations, if bystanders observe others not taking action, they may interpret this as a signal that help is not needed or that it is not their responsibility to intervene. This phenomenon, known as pluralistic ignorance, further inhibits bystander intervention and is particularly relevant when considering social-emotional learning in educational contexts.

These social influences contribute to the bystander effect by creating a sense of shared responsibility that paradoxically reduces individual action. Understanding these mechanisms can help educators develop strategies that promote student wellbeing and encourage intervention when peers need support. This understanding also relates to how attention is directed and how motivation to help others can be enhanced through proper training and awareness. Additionally, providing appropriate scaffolding can help students develop the confidence to act when they witness concerning situations, while feedback mechanisms can reinforce positive intervention behaviours.

To counteract these psychological barriers, educators can implement specific strategies that prepare students to overcome bystander inaction. Pre-commitment techniques involve helping students mentally rehearse scenarios and decide in advance how they would respond, reducing the cognitive load during actual incidents (Anwer et al., 2024). Role-playing exercises allow students to practise intervention skills in safe environments, building confidence and familiarity with appropriate responses.

Pluralistic ignorance training teaches students to recognise when their interpretation of others' calm behaviour may be incorrect (Julinar et al., 2024). Educators can demonstrate how people often mask their concern or uncertainty, helping students understand that apparent indifference doesn't necessarily indicate that intervention is unnecessary. Additionally, teaching students about graduated response options, from seeking adult help to direct intervention, provides them with a toolkit of actions that vary in personal risk and commitment.

Creating classroom discussions around these psychological mechanisms helps normalise the experience of feeling uncertain or hesitant in challenging situations (Hamamura et al., 2024). When students understand that bystander behaviour stems from predictable psychological processes rather than moral failings, they become more equipped to recognise these patterns in themselves and develop strategies to overcome them in educational settings and beyond.

The bystander effect gained widespread attention following the 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese in New York City, where numerous witnesses allegedly failed to intervene or call for help. While later investigations revealed inaccuracies in initial reports, this case prompted psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latané to conduct groundbreaking experiments in the late 1960s. Their research demonstrated that individuals are less likely to help when other bystanders are present, revealing key factors such as diffusion of responsibility and pluralistic ignorance that inhibit prosocial behaviour.

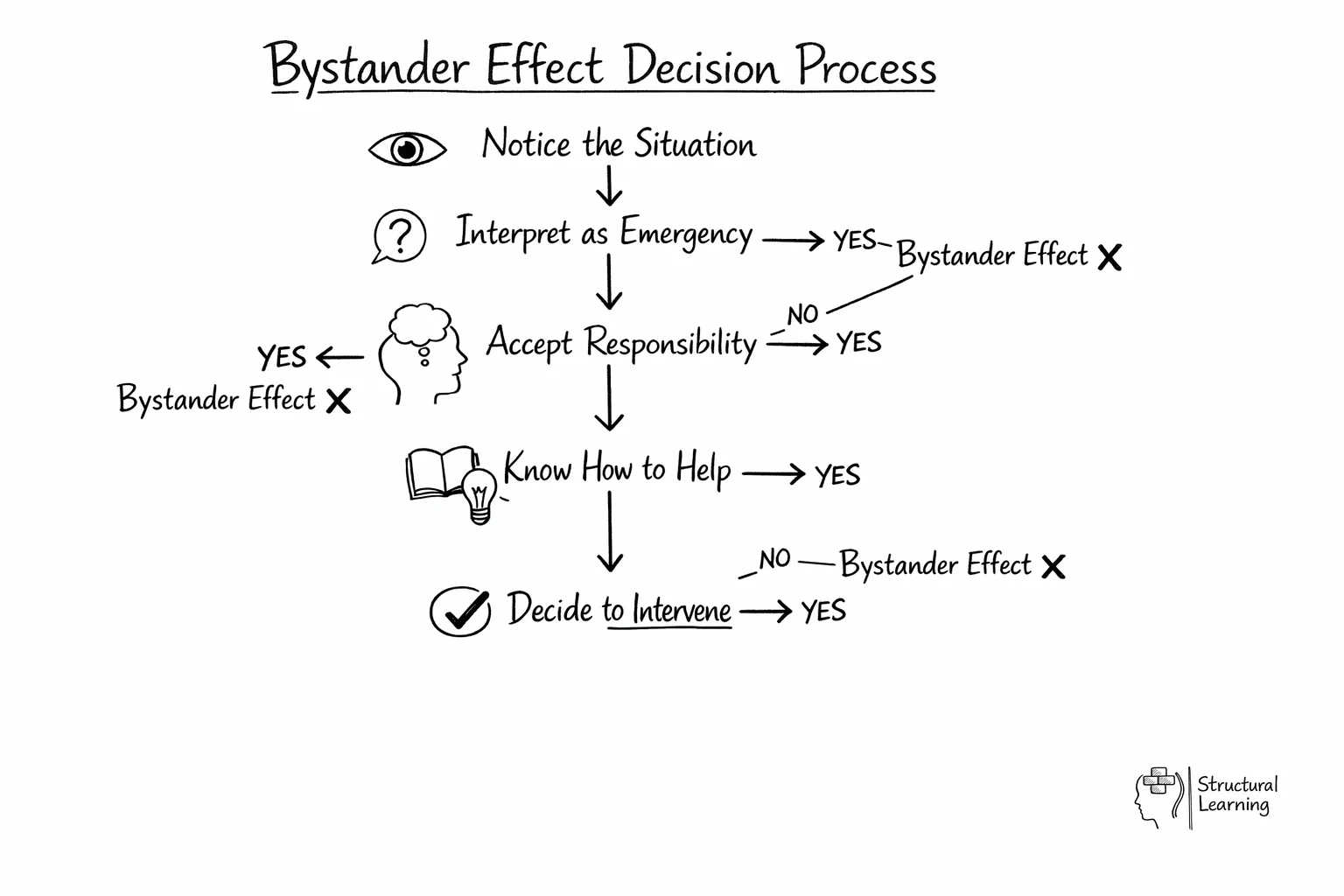

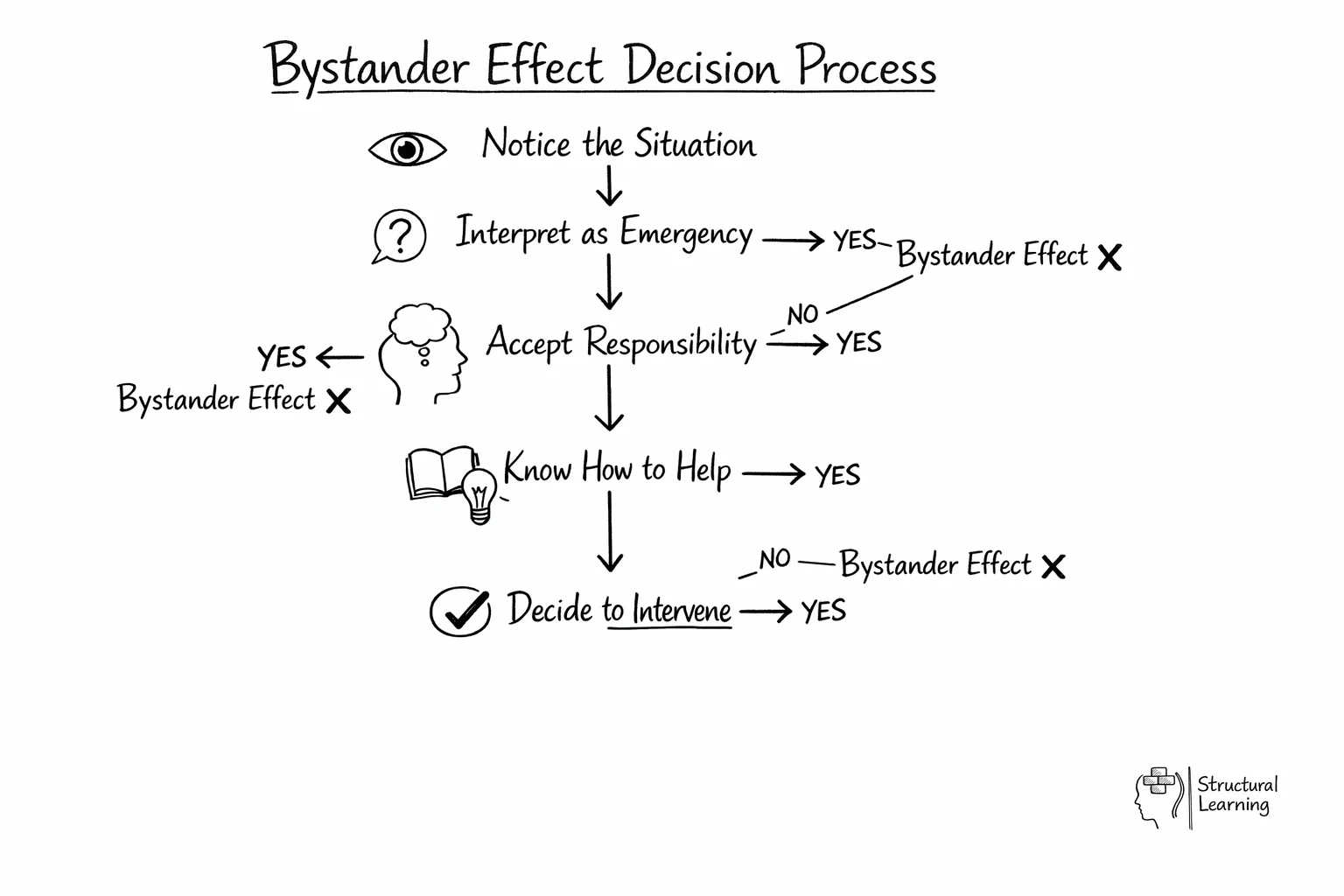

Darley and Latané's seminal studies included staged emergencies where participants believed they were either alone or with others when witnessing someone in distress. Results consistently showed that help-seeking behaviour decreased as the number of perceived bystanders increased. Their work established that bystander intervention follows a cognitive process involving noticing the event, interpreting it as an emergency, accepting responsibility, and possessing the skills to help (Amelia & Amna, 2025).

For educators, these findings highlight explicitly teaching intervention strategies and creating classroom cultures where individual responsibility is emphasised. When addressing bullying or peer conflicts, teachers can reference specific students by name rather than making general appeals to the class, thereby reducing diffusion of responsibility and encouraging active bystander behaviour in educational settings.

Research by social psychologists Darley and Latané reveals that the bystander effect can be significantly reduced through targeted educational interventions. Direct instruction about the phenomenon itself proves particularly effective, as awareness o f diffusion of responsibility helps individuals recognise when they might be falling into passive bystander behaviour. Students who understand the psychological mechanisms behind inaction are more likely to take appropriate action when witnessing concerning situations.

Practical strategies for overcoming the bystander effect centre on specific action planning and role clarification. Teaching students to mentally rehearse intervention scenarios, identify clear steps for seeking help, and understand their personal responsibility creates cognitive pathways that bypass the paralysis often associated with emergency situations. Bandura's social learning theory supports the use of modelled behaviour and peer observation to normalise helpful intervention.

In educational settings, establishing clear reporting procedures and creating a culture of shared responsibility proves essential. Students benefit from understanding exactly whom to approach, when to intervene directly, and how to access appropriate support systems. Regular discussion of scenarios relevant to school environments, combined with explicit teaching about upstander behaviour, transforms theoretical knowledge into practical action. This approach effectively counters the diffusion of responsibility that characterises bystander behaviour in group settings.

The bystander effect manifests prominently in educational settings, where students frequently witness incidents requiring intervention but fail to act due to diffusion of responsibility amongst peers. Research by Latané and Darley demonstrates that this psychological phenomenon occurs when individuals assume others will take action, particularly in situations involving bullying, academic dishonesty, or students experiencing distress. In classroom environments, this behaviour pattern can perpetuate harmful dynamics and undermine the supportive learning community educators strive to create.

Educational settings present unique challenges for addressing bystander behaviour, as students often fear social repercussions, lack confidence in their ability to help effectively, or misinterpret situations as less serious than they actually are. When witnessing cyberbullying, cheating, or peer exclusion, students may rationalise their inaction by believing teachers should handle such matters or that their intervention might worsen the situation.

Educators can combat the bystander effect by implementing explicit instruction about prosocial behaviour and creating clear protocols for reporting concerns. Establishing classroom norms that emphasise collective responsibility for maintaining a positive learning environment helps students to act. Role-playing exercises and discussing real scenarios help students recognise situations requiring intervention whilst building their confidence to respond appropriately, whether through direct action or seeking adult assistance.

The tragic murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964 New York sparked decades of research into why people fail to help during emergencies. Initial reports claimed 38 witnesses watched her attack without intervening, though later investigations revealed this number was exaggerated. Nevertheless, the case prompted psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latané to conduct groundbreaking experiments that established the bystander effect as a recognised psychological phenomenon.

Their research revealed that the probability of helping decreases as the number of bystanders increases, a finding with profound implications for school environments. In classrooms and playgrounds, this translates to situations where pupils witness bullying or distress but remain passive, each assuming others will act. Understanding this historical context helps teachers recognise that pupil inaction isn't necessarily apathy; it's often a predictable psychological response.

For classroom practise, teachers can apply these insights through specific strategies. First, assign explicit roles during group activities, such as "safety monitor" or "wellbeing checker," which counteracts diffusion of responsibility. When discussing school values, use the Genovese case (age-appropriately) to illustrate why personal responsibility matters, helping pupils understand that waiting for others to act can have serious consequences.

Additionally, create "intervention practise" scenarios during PSHE lessons where pupils rehearse stepping forwards to help. Research shows that mental rehearsal significantly increases real-world intervention rates. Consider establishing a "See Something, Say Something" protocol with clear, simple steps pupils can follow when witnessing concerning behaviour, removing the ambiguity that often paralyses potential helpers.

The bystander effect refers to the phenomenon where individuals are less likely to intervene in an emergency situation when other people are present. This happens because they assume that someone else will help, leading to a diffusion of responsibility.

To implement bystander training, start by educating students about the bystander effect and its consequences. Encourage them to take responsibility for their actions and provide training on how to safely intervene in emergency situations.

Bystander intervention can prevent emergencies from worsening, reduce bullying incidents, and promote a culture of responsibility. It also helps in building social bonds and encouraging students to support one another.

Common mistakes include assuming that simply providing information is enough, not addressing personal responsibility, and failing to practice intervention scenarios. It's crucial to ensure active engagement and role-playing.

Evaluate the effectiveness of bystander training by observing changes in student behaviour, conducting surveys to assess knowledge and attitudes, and using incident reports to track any reduction in bullying or emergencies.

Understanding the psychological mechanisms behind the bystander effect equips teachers with crucial insights for creating responsive classroom environments. Three primary factors drive this phenomenon, each with direct implications for school settings.

Diffusion of responsibility occurs when pupils unconsciously distribute the obligation to act across everyone present. In a classroom where several students witness cyberbullying on a shared device, each assumes another will report it. This mental calculation happens within seconds; the more witnesses, the less personal responsibility each feels. Teachers can counter this by establishing clear reporting protocols, such as designated 'digital safety monitors' who rotate weekly, ensuring specific pupils hold explicit responsibility.

Pluralistic ignorance emerges when students misread social cues, believing others' inaction signals the situation isn't serious. During a playground incident, pupils scan their peers' faces for guidance. When everyone appears calm, they conclude intervention isn't necessary, creating a collective misinterpretation. Combat this through regular role-play activities where students practise recognising subtle distress signals and responding appropriately, regardless of peer reactions.

Audience inhibition reflects pupils' fear of embarrassment or social judgement when considering intervention. Students worry about misreading situations, appearing foolish, or facing retaliation. This paralysis intensifies in adolescence when peer perception peaks. Address this by celebrating 'false alarm' interventions in assembly, reinforcing that checking on others demonstrates maturity rather than overreaction.

Research by Latané and Darley (1970) established these mechanisms through controlled experiments, findings consistently replicated in educational contexts. By explicitly teaching these concepts during PSHE lessons and modelling intervention behaviours, teachers transform passive observers into confident responders, creating safer learning environments where pupils understand their psychological tendencies and actively work to overcome them.

The digital age has fundamentally transformed how bystander behaviour manifests in educational environments, extending the psychological phenomenon beyond physical spaces into online platforms where students spend increasing amounts of time. Research by Kowalski and Limber demonstrates that cyberbullying incidents often involve numerous silent observers who witness harmful content but fail to intervene, mirroring the diffusion of responsibility seen in traditional bystander situations. However, digital contexts present unique challenges: the perceived anonymity of online spaces, the asynchronous nature of digital communication, and the broader potential audience all amplify both the harm and the bystander effect.

Social psychology research indicates that online bystanders face additional barriers to intervention, including technological distance from the victim and uncertainty about appropriate digital responses. The permanence of digital content means that harmful material can circulate indefinitely, yet this same permanence creates opportunities for positive bystander intervention through reporting mechanisms and supportive comments.

Educators must therefore expand traditional bystander intervention training to include digital literacy and online citizenship skills. Practical approaches include teaching students to recognise cyberbullying, demonstrating how to safely report incidents through platform-specific tools, and encouraging supportive private messaging to victims. Creating classroom discussions about digital bystander scenarios helps students develop confidence in online intervention strategies.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the evidence base for the strategies discussed above.

The application of VR in studying the bystander effect in school bullying View study ↗

21 citations

Liu et al. (2022)

This study explores using virtual reality technology to research bystander behaviour in school bullying scenarios. For teachers, this could provide innovative ways to train students in intervention strategies and help them understand the psychological factors that prevent peers from helping victims of bullying.

Hubungan Antara Bystander Effect dengan Perilaku Prososial pada Mahasiswa Pekanbaru View study ↗

Julinar et al. (2024)

This research examines how bystander effect influences prosocial behaviour amongst university students in Pekanbaru. Teachers can apply these findings to encourage more active intervention in classroom situations, helping students overcome the tendency to avoid helping others when multiple witnesses are present.

Influence Bystander Effect and Whistleblowing to Fraud Billing Receivables View study ↗

Amelia et al. (2025)

This study investigates bystander effect and whistleblowing in financial fraud contexts. While not directly educational, teachers can use these concepts to help students understand ethical decision-making, encouraging them to speak up against wrongdoing rather than remaining passive observers.

A Brief Review of Conformity: Bandwagon Effect and Bystander Effect View study ↗

Sun (2024)

This paper reviews conformity behaviours including bandwagon and bystander effects in social situations. Teachers can use this research to help students recognise when they're following the crowd inappropriately or failing to help others, promoting more independent thinking and prosocial behaviour.

Bystander Effect: Workplace Harassment of Women at Educational Institutes: A Case Study of the University of Okara View study ↗

Anwer et al. (2024)

This research examines why workplace harassment goes unreported at educational institutions, focusing on bystander effect. Teachers and educational administrators can use these findings to create safer environments where staff feel empowered to report misconduct and support colleagues facing harassment.

THE EFFECT OF FLIPPED CLASSROOM PRACTICES ON STUDENTS' ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT AND RESPONSIBILITY LEVELS IN SOCIAL STUDIES COURSE View study ↗

20 citations

Sercan Bursa & Tuba Cengelci Kose (2020)

Researchers found that flipped classroom methods, where students learn content at home and apply it in class, significantly increased both academic achievement and student responsibility in social studies. Students who experienced flipped learning took more ownership of their education and performed better academically compared to traditional lecture-based classes. This approach offers teachers a practical way to encourage both learning outcomes and character development, particularly important for developing engaged citizens.

The Comparison of the Efficiency of the Lecture Method and Flipped Classroom Instruction Method on EFL Students' Academic Passion and Responsibility View study ↗

20 citations

Fei Liu et al. (2023)

This study comparing traditional lectures to flipped classroom methods in English language learning found that students taught with flipped approaches showed greater passion for learning and took more responsibility for their progress. The flipped method, where students engage with material before class and use class time for active practise, created more motivated and self-directed learners. Language teachers can use these findings to redesign their courses for better student engagement and autonomy.

The Sohanjana Antibullying Intervention: Pilot Results of a Peer-Training Module in Pakistan View study ↗

9 citations

Sohni Siddiqui & Anja Schultze‐Krumbholz (2023)

This pilot programme in Pakistan successfully trained students to become peer advocates who intervene in bullying situations, offering a cost-effective alternative to expensive whole-school programmes. Students learned to recognise bullying and take action to help victims, creating a network of young defenders throughout the school. For teachers in schools with limited resources, this peer-training model provides a practical approach to reducing bullying by enabling students to become part of the solution.

Defending behaviour in school bullying: The role of empathic self-efficacy, social preference, and student-teacher relationship View study ↗

4 citations

Valentina Levantini et al. (2024)

Research with 249 middle school students revealed that students who believe in their ability to understand and help others are more likely to defend bullying victims, especially when they have strong relationships with teachers. The study shows that building empathy skills and positive teacher-student connections creates natural defenders against bullying. Teachers can reduce bullying by focusing on empathy development and cultivating supportive relationships that encourage students to stand up for their peers.

Cooperative learning in basic education: a theoretical review View study ↗

5 citations

Lucas Néstor Pérez Salgado et al. (2022)

This comprehensive review confirms that cooperative learning strategies significantly boost student achievement and social skills when implemented effectively in secondary classrooms. The research emphasises that successful cooperative learning requires careful structuring, including face-to-face interaction, positive interdependence, and shared responsibility among group members. Teachers will find this valuable as it provides evidence-based guidance for moving beyond traditional group work to create truly collaborative learning experiences that develop both academic and interpersonal competencies.

El Future Classroom Lab de Bruselas: View study ↗

1 citations

Miranda Zamberlan Nedel & Miguel Antonio Buzzar (2020)

This case study examines Brussels' Future Classroom Lab, an effective learning space design that has inspired over 200 similar laboratories worldwide and represents a model for 21st-century education environments. The research provides critical insights into how physical classroom spaces can be redesigned to support modern pedagogical approaches and student collaboration. Educators and school leaders will appreciate this analysis as they consider how their own classroom layouts and learning environments might be reimagined to better support contemporary teaching methods and student engagement.

Integrating the Values of Silih Asah, Silih Asih, and Silih Asuh in Primary School Character Education: Cultural Implications and Prosocial Behaviour View study ↗

Yoyo Zakaria Ansori et al. (2025)

This study explores how traditional Sundanese values of mutual learning, caring, and support can be effectively integrated into elementary character education programmes to build prosocial behaviour in students. The research demonstrates that incorporating local cultural wisdom into classroom practices strengthens students' moral development across cognitive, emotional, and behavioural dimensions. Primary teachers will find this particularly relevant as it shows how honoring students' cultural backgrounds while teaching universal values like cooperation and empathy can create more meaningful and effective character education experiences.

PENYELESAIAN PERMASALAHAN SANTRI MELALUI PEER HELPING INDIGENOUS View study ↗

2 citations

Reni Yunita (2023)

This research examines how peer helping programmes can address the unique challenges faced by adolescent students who are navigating the tension between childhood dependence and emerging independence. The study shows that when young people are trained to provide support to their peers, it creates powerful opportunities for both helpers and those receiving help to develop maturity and social skills. Teachers working with adolescents will find this valuable as it demonstrates how structured peer support systems can address behavioural challenges while promoting positive youth development and reducing reliance on adult authority figures.

The bystander effect, a term deeply embedded in social psychology, captures the puzzling human tendency to become an unresponsive bystander during emergencies when others are present.

| Increases Intervention | Example | Decreases Intervention | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small group size | One or two witnesses present | Large group size | Many people observing the incident |

| Clear emergency | Obvious signs of distress or danger | Ambiguous situation | Unclear if help is needed |

| Personal responsibility | Being the only witness or directly addressed | Diffusion of responsibility | Assuming someone else will help |

| Competence/training | First aid training or relevant expertise | Lack of skills | Unsure how to help effectively |

| Personal connection | Knowing the victim or shared identity | Anonymity | Being a stranger in a crowd |

This phenomenon, often attributed to a diffusion of responsibility, leads to a decreased likelihood of intervention, as individuals unconsciously assume that someone else will take action (Sun, 2024).

practical strategies to overcome bystander effect and become an active intervener in emergencies" loading="lazy">

practical strategies to overcome bystander effect and become an active intervener in emergencies" loading="lazy">For instance, in a crowded school hallway where bullying is occurring, bystanders may overlook the situation, believing that another person will step in, thereby contributing to a collective inaction (Liu et al., 2022). This highlights implementing targeted classroom management strategies that enable pupils to become active participants rather than passive observers.

This effect was tragically illustrated in the case of Kitty Genovese in 1964, where her brutal attack was witnessed by several individuals who failed to intervene or call for help. This incident not only shocked the public but also ignited a spark in the field of social psychology, leading to extensive research, including studies published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

One relevant statistic that underscores the gravity of this issue is that in situations with more th an five bystanders, the likelihood of intervention drops by over 50%. The bystander effect is not merely a curiosity; it's a profound insight into human behaviour that has real emergency implications in our crowded minds.

Understanding bystander behaviour is crucial in today's interconnected world. It's not just about public self-awareness but about encouraging a sense of res ponsibility on bystander intervention.

Through targeted modelling strategies and targeted education and bystander training, we can challenge the implicit bystander theory that often governs our reactions, enabling individuals to transcend passivity and actively assist those in distress.

Key Insights and Important Facts:

Social influences create the bystander effect through diffusion of responsibility, where individuals assume others will take action, and pluralistic ignorance, where people misinterpret others' inaction as appropriate behaviour. The presence of more people actually reduces individual responsibility and increases conformity to perceived group norms (Jiang, 2023). These psychological mechanisms explain why crowded environments often see less intervention during emergencies or incidents.

The bystander effect, a phenomenon in which individuals are less likely to intervene in emergency situations when other people are present, can be attributed in part to social influences. One key factor contributing to the bystander effect is the diffusion of responsibility.

When faced with an emergency situation, individuals may feel less personally responsible to take action because they assume that someone else will step in and help. This diffusion of responsibility can lead to inaction and a lack of intervention, which is similar to patterns observed in the Dunning-Kruger Effect where cognitive biases affect decision-making.

Social influence also plays a role in the bystander effect. According to social comparison theory, individuals tend to look to others for cues on how to behave in ambiguous situations.

In emergency situations, if bystanders observe others not taking action, they may interpret this as a signal that help is not needed or that it is not their responsibility to intervene. This phenomenon, known as pluralistic ignorance, further inhibits bystander intervention and is particularly relevant when considering social-emotional learning in educational contexts.

These social influences contribute to the bystander effect by creating a sense of shared responsibility that paradoxically reduces individual action. Understanding these mechanisms can help educators develop strategies that promote student wellbeing and encourage intervention when peers need support. This understanding also relates to how attention is directed and how motivation to help others can be enhanced through proper training and awareness. Additionally, providing appropriate scaffolding can help students develop the confidence to act when they witness concerning situations, while feedback mechanisms can reinforce positive intervention behaviours.

To counteract these psychological barriers, educators can implement specific strategies that prepare students to overcome bystander inaction. Pre-commitment techniques involve helping students mentally rehearse scenarios and decide in advance how they would respond, reducing the cognitive load during actual incidents (Anwer et al., 2024). Role-playing exercises allow students to practise intervention skills in safe environments, building confidence and familiarity with appropriate responses.

Pluralistic ignorance training teaches students to recognise when their interpretation of others' calm behaviour may be incorrect (Julinar et al., 2024). Educators can demonstrate how people often mask their concern or uncertainty, helping students understand that apparent indifference doesn't necessarily indicate that intervention is unnecessary. Additionally, teaching students about graduated response options, from seeking adult help to direct intervention, provides them with a toolkit of actions that vary in personal risk and commitment.

Creating classroom discussions around these psychological mechanisms helps normalise the experience of feeling uncertain or hesitant in challenging situations (Hamamura et al., 2024). When students understand that bystander behaviour stems from predictable psychological processes rather than moral failings, they become more equipped to recognise these patterns in themselves and develop strategies to overcome them in educational settings and beyond.

The bystander effect gained widespread attention following the 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese in New York City, where numerous witnesses allegedly failed to intervene or call for help. While later investigations revealed inaccuracies in initial reports, this case prompted psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latané to conduct groundbreaking experiments in the late 1960s. Their research demonstrated that individuals are less likely to help when other bystanders are present, revealing key factors such as diffusion of responsibility and pluralistic ignorance that inhibit prosocial behaviour.

Darley and Latané's seminal studies included staged emergencies where participants believed they were either alone or with others when witnessing someone in distress. Results consistently showed that help-seeking behaviour decreased as the number of perceived bystanders increased. Their work established that bystander intervention follows a cognitive process involving noticing the event, interpreting it as an emergency, accepting responsibility, and possessing the skills to help (Amelia & Amna, 2025).

For educators, these findings highlight explicitly teaching intervention strategies and creating classroom cultures where individual responsibility is emphasised. When addressing bullying or peer conflicts, teachers can reference specific students by name rather than making general appeals to the class, thereby reducing diffusion of responsibility and encouraging active bystander behaviour in educational settings.

Research by social psychologists Darley and Latané reveals that the bystander effect can be significantly reduced through targeted educational interventions. Direct instruction about the phenomenon itself proves particularly effective, as awareness o f diffusion of responsibility helps individuals recognise when they might be falling into passive bystander behaviour. Students who understand the psychological mechanisms behind inaction are more likely to take appropriate action when witnessing concerning situations.

Practical strategies for overcoming the bystander effect centre on specific action planning and role clarification. Teaching students to mentally rehearse intervention scenarios, identify clear steps for seeking help, and understand their personal responsibility creates cognitive pathways that bypass the paralysis often associated with emergency situations. Bandura's social learning theory supports the use of modelled behaviour and peer observation to normalise helpful intervention.

In educational settings, establishing clear reporting procedures and creating a culture of shared responsibility proves essential. Students benefit from understanding exactly whom to approach, when to intervene directly, and how to access appropriate support systems. Regular discussion of scenarios relevant to school environments, combined with explicit teaching about upstander behaviour, transforms theoretical knowledge into practical action. This approach effectively counters the diffusion of responsibility that characterises bystander behaviour in group settings.

The bystander effect manifests prominently in educational settings, where students frequently witness incidents requiring intervention but fail to act due to diffusion of responsibility amongst peers. Research by Latané and Darley demonstrates that this psychological phenomenon occurs when individuals assume others will take action, particularly in situations involving bullying, academic dishonesty, or students experiencing distress. In classroom environments, this behaviour pattern can perpetuate harmful dynamics and undermine the supportive learning community educators strive to create.

Educational settings present unique challenges for addressing bystander behaviour, as students often fear social repercussions, lack confidence in their ability to help effectively, or misinterpret situations as less serious than they actually are. When witnessing cyberbullying, cheating, or peer exclusion, students may rationalise their inaction by believing teachers should handle such matters or that their intervention might worsen the situation.

Educators can combat the bystander effect by implementing explicit instruction about prosocial behaviour and creating clear protocols for reporting concerns. Establishing classroom norms that emphasise collective responsibility for maintaining a positive learning environment helps students to act. Role-playing exercises and discussing real scenarios help students recognise situations requiring intervention whilst building their confidence to respond appropriately, whether through direct action or seeking adult assistance.

The tragic murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964 New York sparked decades of research into why people fail to help during emergencies. Initial reports claimed 38 witnesses watched her attack without intervening, though later investigations revealed this number was exaggerated. Nevertheless, the case prompted psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latané to conduct groundbreaking experiments that established the bystander effect as a recognised psychological phenomenon.

Their research revealed that the probability of helping decreases as the number of bystanders increases, a finding with profound implications for school environments. In classrooms and playgrounds, this translates to situations where pupils witness bullying or distress but remain passive, each assuming others will act. Understanding this historical context helps teachers recognise that pupil inaction isn't necessarily apathy; it's often a predictable psychological response.

For classroom practise, teachers can apply these insights through specific strategies. First, assign explicit roles during group activities, such as "safety monitor" or "wellbeing checker," which counteracts diffusion of responsibility. When discussing school values, use the Genovese case (age-appropriately) to illustrate why personal responsibility matters, helping pupils understand that waiting for others to act can have serious consequences.

Additionally, create "intervention practise" scenarios during PSHE lessons where pupils rehearse stepping forwards to help. Research shows that mental rehearsal significantly increases real-world intervention rates. Consider establishing a "See Something, Say Something" protocol with clear, simple steps pupils can follow when witnessing concerning behaviour, removing the ambiguity that often paralyses potential helpers.

The bystander effect refers to the phenomenon where individuals are less likely to intervene in an emergency situation when other people are present. This happens because they assume that someone else will help, leading to a diffusion of responsibility.

To implement bystander training, start by educating students about the bystander effect and its consequences. Encourage them to take responsibility for their actions and provide training on how to safely intervene in emergency situations.

Bystander intervention can prevent emergencies from worsening, reduce bullying incidents, and promote a culture of responsibility. It also helps in building social bonds and encouraging students to support one another.

Common mistakes include assuming that simply providing information is enough, not addressing personal responsibility, and failing to practice intervention scenarios. It's crucial to ensure active engagement and role-playing.

Evaluate the effectiveness of bystander training by observing changes in student behaviour, conducting surveys to assess knowledge and attitudes, and using incident reports to track any reduction in bullying or emergencies.

Understanding the psychological mechanisms behind the bystander effect equips teachers with crucial insights for creating responsive classroom environments. Three primary factors drive this phenomenon, each with direct implications for school settings.

Diffusion of responsibility occurs when pupils unconsciously distribute the obligation to act across everyone present. In a classroom where several students witness cyberbullying on a shared device, each assumes another will report it. This mental calculation happens within seconds; the more witnesses, the less personal responsibility each feels. Teachers can counter this by establishing clear reporting protocols, such as designated 'digital safety monitors' who rotate weekly, ensuring specific pupils hold explicit responsibility.

Pluralistic ignorance emerges when students misread social cues, believing others' inaction signals the situation isn't serious. During a playground incident, pupils scan their peers' faces for guidance. When everyone appears calm, they conclude intervention isn't necessary, creating a collective misinterpretation. Combat this through regular role-play activities where students practise recognising subtle distress signals and responding appropriately, regardless of peer reactions.

Audience inhibition reflects pupils' fear of embarrassment or social judgement when considering intervention. Students worry about misreading situations, appearing foolish, or facing retaliation. This paralysis intensifies in adolescence when peer perception peaks. Address this by celebrating 'false alarm' interventions in assembly, reinforcing that checking on others demonstrates maturity rather than overreaction.

Research by Latané and Darley (1970) established these mechanisms through controlled experiments, findings consistently replicated in educational contexts. By explicitly teaching these concepts during PSHE lessons and modelling intervention behaviours, teachers transform passive observers into confident responders, creating safer learning environments where pupils understand their psychological tendencies and actively work to overcome them.

The digital age has fundamentally transformed how bystander behaviour manifests in educational environments, extending the psychological phenomenon beyond physical spaces into online platforms where students spend increasing amounts of time. Research by Kowalski and Limber demonstrates that cyberbullying incidents often involve numerous silent observers who witness harmful content but fail to intervene, mirroring the diffusion of responsibility seen in traditional bystander situations. However, digital contexts present unique challenges: the perceived anonymity of online spaces, the asynchronous nature of digital communication, and the broader potential audience all amplify both the harm and the bystander effect.

Social psychology research indicates that online bystanders face additional barriers to intervention, including technological distance from the victim and uncertainty about appropriate digital responses. The permanence of digital content means that harmful material can circulate indefinitely, yet this same permanence creates opportunities for positive bystander intervention through reporting mechanisms and supportive comments.

Educators must therefore expand traditional bystander intervention training to include digital literacy and online citizenship skills. Practical approaches include teaching students to recognise cyberbullying, demonstrating how to safely report incidents through platform-specific tools, and encouraging supportive private messaging to victims. Creating classroom discussions about digital bystander scenarios helps students develop confidence in online intervention strategies.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the evidence base for the strategies discussed above.

The application of VR in studying the bystander effect in school bullying View study ↗

21 citations

Liu et al. (2022)

This study explores using virtual reality technology to research bystander behaviour in school bullying scenarios. For teachers, this could provide innovative ways to train students in intervention strategies and help them understand the psychological factors that prevent peers from helping victims of bullying.

Hubungan Antara Bystander Effect dengan Perilaku Prososial pada Mahasiswa Pekanbaru View study ↗

Julinar et al. (2024)

This research examines how bystander effect influences prosocial behaviour amongst university students in Pekanbaru. Teachers can apply these findings to encourage more active intervention in classroom situations, helping students overcome the tendency to avoid helping others when multiple witnesses are present.

Influence Bystander Effect and Whistleblowing to Fraud Billing Receivables View study ↗

Amelia et al. (2025)

This study investigates bystander effect and whistleblowing in financial fraud contexts. While not directly educational, teachers can use these concepts to help students understand ethical decision-making, encouraging them to speak up against wrongdoing rather than remaining passive observers.

A Brief Review of Conformity: Bandwagon Effect and Bystander Effect View study ↗

Sun (2024)

This paper reviews conformity behaviours including bandwagon and bystander effects in social situations. Teachers can use this research to help students recognise when they're following the crowd inappropriately or failing to help others, promoting more independent thinking and prosocial behaviour.

Bystander Effect: Workplace Harassment of Women at Educational Institutes: A Case Study of the University of Okara View study ↗

Anwer et al. (2024)

This research examines why workplace harassment goes unreported at educational institutions, focusing on bystander effect. Teachers and educational administrators can use these findings to create safer environments where staff feel empowered to report misconduct and support colleagues facing harassment.

THE EFFECT OF FLIPPED CLASSROOM PRACTICES ON STUDENTS' ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT AND RESPONSIBILITY LEVELS IN SOCIAL STUDIES COURSE View study ↗

20 citations

Sercan Bursa & Tuba Cengelci Kose (2020)

Researchers found that flipped classroom methods, where students learn content at home and apply it in class, significantly increased both academic achievement and student responsibility in social studies. Students who experienced flipped learning took more ownership of their education and performed better academically compared to traditional lecture-based classes. This approach offers teachers a practical way to encourage both learning outcomes and character development, particularly important for developing engaged citizens.

The Comparison of the Efficiency of the Lecture Method and Flipped Classroom Instruction Method on EFL Students' Academic Passion and Responsibility View study ↗

20 citations

Fei Liu et al. (2023)

This study comparing traditional lectures to flipped classroom methods in English language learning found that students taught with flipped approaches showed greater passion for learning and took more responsibility for their progress. The flipped method, where students engage with material before class and use class time for active practise, created more motivated and self-directed learners. Language teachers can use these findings to redesign their courses for better student engagement and autonomy.

The Sohanjana Antibullying Intervention: Pilot Results of a Peer-Training Module in Pakistan View study ↗

9 citations

Sohni Siddiqui & Anja Schultze‐Krumbholz (2023)

This pilot programme in Pakistan successfully trained students to become peer advocates who intervene in bullying situations, offering a cost-effective alternative to expensive whole-school programmes. Students learned to recognise bullying and take action to help victims, creating a network of young defenders throughout the school. For teachers in schools with limited resources, this peer-training model provides a practical approach to reducing bullying by enabling students to become part of the solution.

Defending behaviour in school bullying: The role of empathic self-efficacy, social preference, and student-teacher relationship View study ↗

4 citations

Valentina Levantini et al. (2024)

Research with 249 middle school students revealed that students who believe in their ability to understand and help others are more likely to defend bullying victims, especially when they have strong relationships with teachers. The study shows that building empathy skills and positive teacher-student connections creates natural defenders against bullying. Teachers can reduce bullying by focusing on empathy development and cultivating supportive relationships that encourage students to stand up for their peers.

Cooperative learning in basic education: a theoretical review View study ↗

5 citations

Lucas Néstor Pérez Salgado et al. (2022)

This comprehensive review confirms that cooperative learning strategies significantly boost student achievement and social skills when implemented effectively in secondary classrooms. The research emphasises that successful cooperative learning requires careful structuring, including face-to-face interaction, positive interdependence, and shared responsibility among group members. Teachers will find this valuable as it provides evidence-based guidance for moving beyond traditional group work to create truly collaborative learning experiences that develop both academic and interpersonal competencies.

El Future Classroom Lab de Bruselas: View study ↗

1 citations

Miranda Zamberlan Nedel & Miguel Antonio Buzzar (2020)

This case study examines Brussels' Future Classroom Lab, an effective learning space design that has inspired over 200 similar laboratories worldwide and represents a model for 21st-century education environments. The research provides critical insights into how physical classroom spaces can be redesigned to support modern pedagogical approaches and student collaboration. Educators and school leaders will appreciate this analysis as they consider how their own classroom layouts and learning environments might be reimagined to better support contemporary teaching methods and student engagement.

Integrating the Values of Silih Asah, Silih Asih, and Silih Asuh in Primary School Character Education: Cultural Implications and Prosocial Behaviour View study ↗

Yoyo Zakaria Ansori et al. (2025)

This study explores how traditional Sundanese values of mutual learning, caring, and support can be effectively integrated into elementary character education programmes to build prosocial behaviour in students. The research demonstrates that incorporating local cultural wisdom into classroom practices strengthens students' moral development across cognitive, emotional, and behavioural dimensions. Primary teachers will find this particularly relevant as it shows how honoring students' cultural backgrounds while teaching universal values like cooperation and empathy can create more meaningful and effective character education experiences.

PENYELESAIAN PERMASALAHAN SANTRI MELALUI PEER HELPING INDIGENOUS View study ↗

2 citations

Reni Yunita (2023)

This research examines how peer helping programmes can address the unique challenges faced by adolescent students who are navigating the tension between childhood dependence and emerging independence. The study shows that when young people are trained to provide support to their peers, it creates powerful opportunities for both helpers and those receiving help to develop maturity and social skills. Teachers working with adolescents will find this valuable as it demonstrates how structured peer support systems can address behavioural challenges while promoting positive youth development and reducing reliance on adult authority figures.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/bystander-effect#article","headline":"Bystander Effect","description":"Explore the bystander effect, a psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to help in an emergency when others are present.","datePublished":"2023-08-01T11:15:03.859Z","dateModified":"2026-02-09T16:57:51.252Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/bystander-effect"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69523c5000ac2e1d5eb40bdb_69523c4e5f6e68c050310d5f_bystander-effect-infographic.webp","wordCount":4551},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/bystander-effect#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Bystander Effect","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/bystander-effect"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is the Bystander Effect?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The bystander effect refers to the phenomenon where individuals are less likely to intervene in an emergency situation when other people are present. This happens because they assume that someone else will help, leading to a diffusion of responsibility."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How do I implement bystander training in the classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"To implement bystander training, start by educating students about the bystander effect and its consequences. Encourage them to take responsibility for their actions and provide training on how to safely intervene in emergency situations."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the benefits of bystander intervention?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Bystander intervention can prevent emergencies from worsening, reduce bullying incidents, and promote a culture of responsibility. It also helps in building social bonds and encouraging students to support one another."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are common mistakes when using bystander training?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Common mistakes include assuming that simply providing information is enough, not addressing personal responsibility, and failing to practice intervention scenarios. It's crucial to ensure active engagement and role-playing."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How do I know if bystander training is working?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Evaluate the effectiveness of bystander training by observing changes in student behaviour, conducting surveys to assess knowledge and attitudes, and using incident reports to track any reduction in bullying or emergencies."}}]}]}