Transference of Learning

Explore transference of learning: its types, theories, and strategies to promote it in students. Plus, discover the challenges and key research studies.

Explore transference of learning: its types, theories, and strategies to promote it in students. Plus, discover the challenges and key research studies.

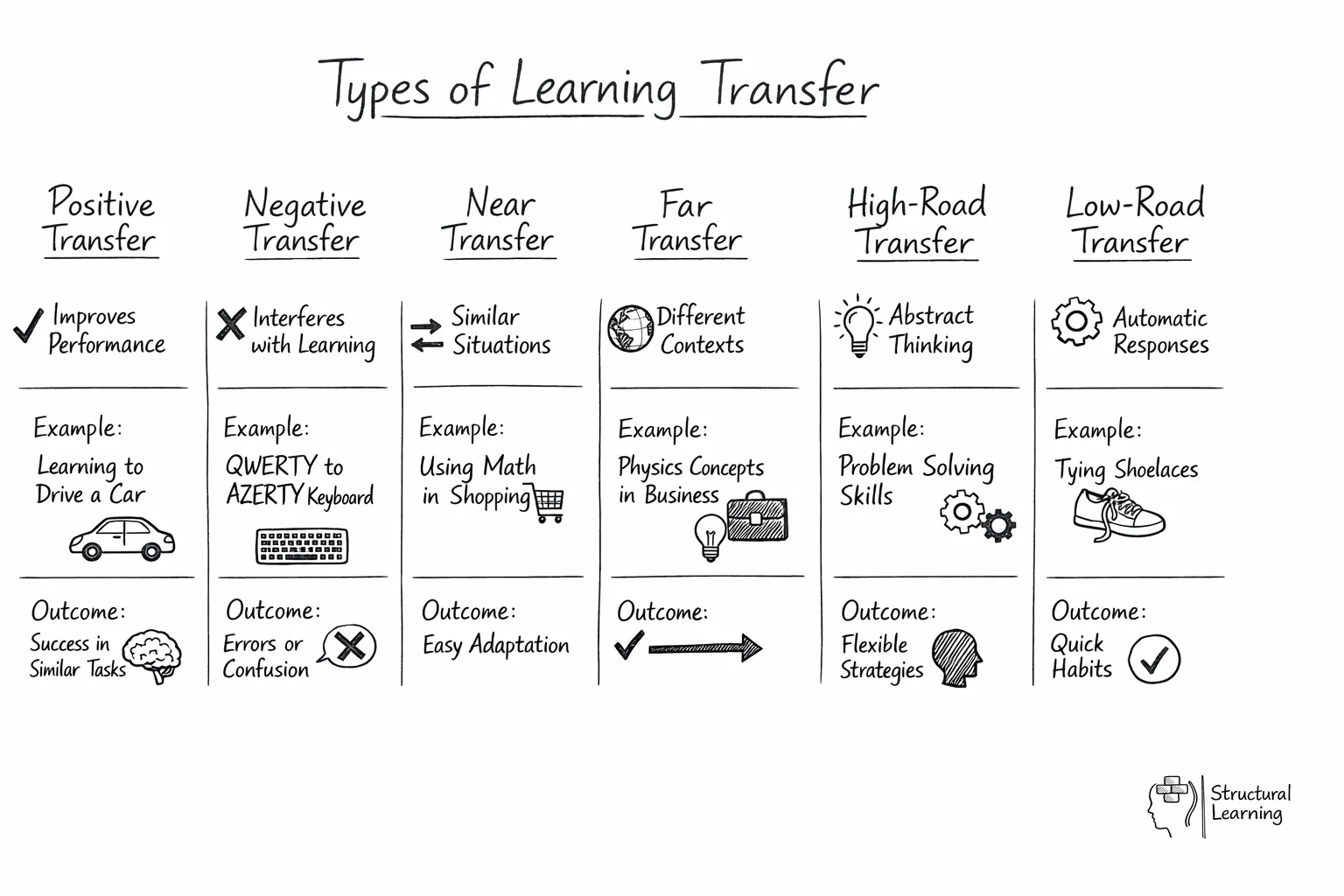

| Transfer Type | Description | Example | Teaching Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Near Transfer | Similar contexts | Using addition in different word problems | Practice with variations |

| Far Transfer | Different contexts | Applying scientific method to daily decisions | Explicit bridging |

| Positive Transfer | Prior learning helps | Spanish helping with Italian | Highlight connections |

| Negative Transfer | Prior learning interferes | Driving on opposite side abroad | Address misconceptions |

| Vertical Transfer | Building complexity | Fractions to algebra | Scaffold progression |

Transfer of learning is the cognitive process where students apply knowledge, skills, or strategies learned in one context to new situations. It represents a key educational goal because it shows that learning has taken root and can be used flexibly across different domains. Successful transfer requires learners to recognise connections between their prior knowledge and new challenges.

Transference of learning refers to the process by which learners , skills, declarative memory, or strategies learned in one situation to a different context. Far from being a passive outcome, this cognitive shift represents an essential educational goal, helping learners make meaningful connections between past experiences and new challenges. Whether applying retrieval practice or spaced practice in real-world scenarios or adapting communication strategies across subjects, transf erence shows that learning has not only occurred but has also taken root.

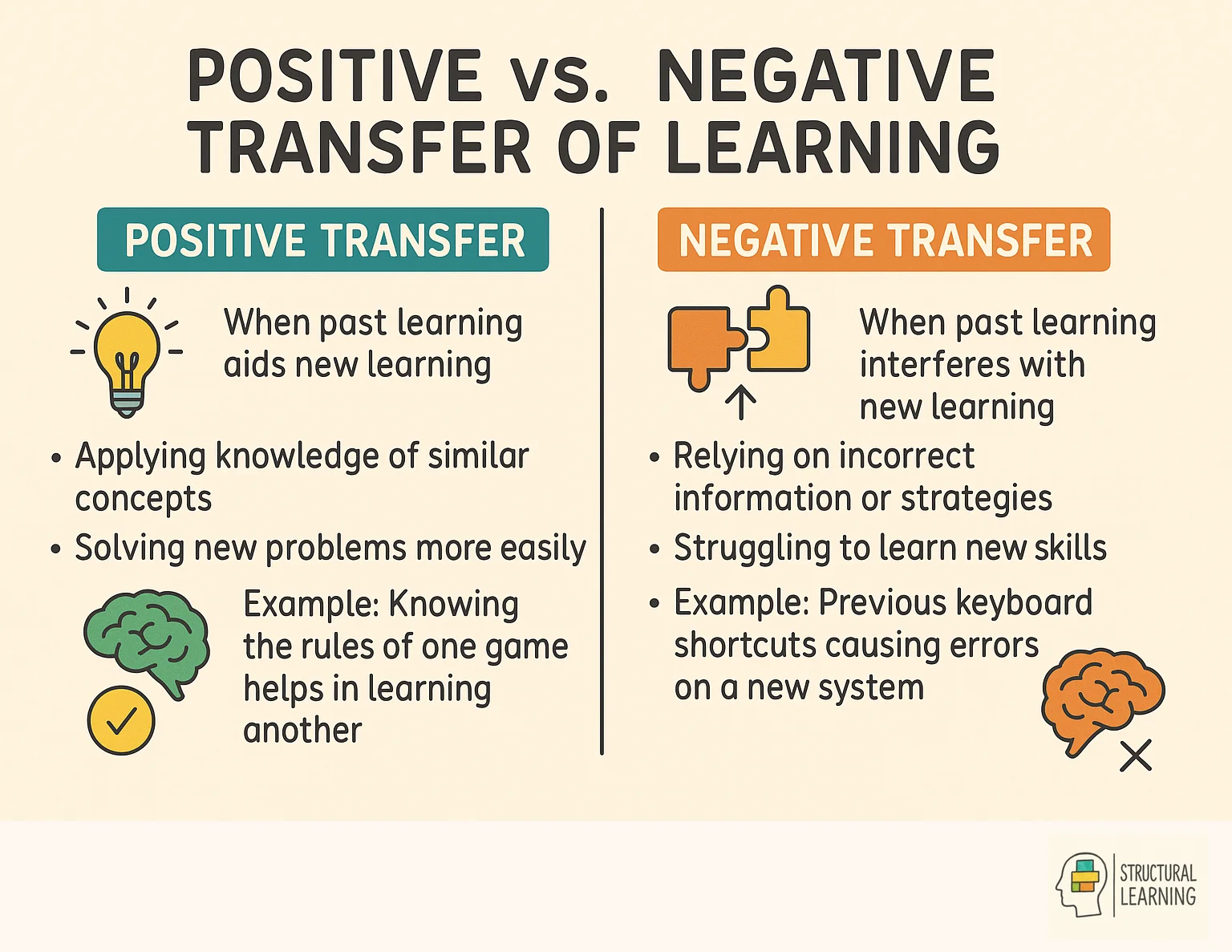

In education, transference can be either positive or negative. Positive transference supports learning by reinforcing useful habits and knowledge across domains, for example, using an understanding of geometry to approach architectural design. Negative transference, on the other hand, occurs when prior knowledge interferes with new learning, such as applying a familiar rule in an unfamiliar or inappropriate context.

Successful transference doesn't happen automatically. It depends on several key factors: the similarity between learning contexts, the learner's depth of understanding, and the extent to which instruction creates flexible thinking. When teaching is designed with these in mind, learners are better equipped to transfer what they know across subjects and into real-world settings.

The main theories include near vs. Far transfer (based on context similarity), low-road vs. High-road transfer (automatic vs. Deliberate application), and positive vs. Negative transfer (helpful vs. Interfering effects). Near transfer occurs between similar contexts while far transfer bridges different domains. High-road transfer requires conscious abstraction and metacognitive awareness, while low-road transfer happens automatically through extensive practice.

Transfer of learning theories play a crucial role in understanding how knowledge and skills can be applied and transferred to different contexts. Two prominent theories in this domain are the theory of identical elements and the theory of generalisation of experience.

The theory of identical elements suggests that transfer occurs when there are similar or identical elements between the original learning context and the transfer context. This means that if there are shared features or components between two situations, the learning from one situation can be effectively transferred to another.

For example, if a student has learned in a mathematics class, they can apply these strategies to solve real-world problems that require similar analytical thinking.

In contrast, the theory of generalisation of experience proposes that transfer of learning can happen through the development of general principles. It suggests that what is learned in one task can be applied to another task by extracting and applying underlying principles or concepts.

For instance, if students have learned about the scientific method in a biology class, they can apply this knowledge to conduct experiments in physics or chemistry.

These theories emphasise the importance of identifying the common elements, concepts, or principles across . By understanding these theories, educators can design instruction and learning experiences that promote transfer of learning and enable students to apply their knowledge and skills in diverse contexts.

Teachers can promote transfer by explicitly teaching for connections between topics, using varied examples across contexts, and encouraging students to identify underlying principles. Effective strategies include having students explain how new learning relates to prior knowledge and practicing skills in multiple settings. Regular metacognitive reflection helps students recognise when and how to apply their learning in new situations.

Promoting students' transfer of learning is essential for helping them and skills in different contexts. Here are strategies that can be utilised to promote transfer of learning:

1. Assignments and Learning Experiences: Design assignments and educational journeys that involve transfer practice within and across courses. Provide opportunities for students to apply what they have learned in one subject to solve problems or analyse situations in another subject. This can be done through case studies, simulations, or real-world project-based learning activities.

2. Transfer Maps: Use transfer maps to identify and skills that are relevant across different curriculum areas. Help students build schema by connecting new information to existing knowledge structures. These visual representations can support students with special educational needs by making abstract connections more concrete.

3. Metacognitive Strategies: Teach students self-regulation techniques that help them reflect on their learning process. Encourage students to develop critical thinking skills by analysing when and how their knowledge applies to new situations.

4. Direct Instruction and Practice: Focus student attention on key principles and provide multiple practice opportunities. Use concept mapping activities to help students visualize connections between different topics.

5. Motivation and Engagement: Implement strategies that enhance student motivation to see learning as meaningful and applicable. Use inquiry-based approaches that encourage students to discover connections themselves.

6. Reading and Comprehension: Develop reading comprehension skills that help students extract transferable principles from texts and apply them across different subject areas.

Successful transfer also depends on helping students develop metacognitive awareness of their learning process. Teachers should explicitly discuss when and why certain strategies work, encouraging students to reflect on their problem-solving approaches. For instance, after solving a mathematics word problem, teachers might ask students to identify which previous concepts they applied and explain their reasoning process.

Another powerful approach involves using varied practice contexts. Rather than presenting all examples from the same domain, teachers should introduce problems that require the same underlying principles but appear in different formats or situations. This helps students recognise the deep structure of concepts rather than memorising surface features. Research by cognitive scientists like John Anderson demonstrates that this variability in practice contexts significantly improves transfer to novel situations.

Creating explicit bridging activities can also enhance transfer. These might include comparison exercises where students identify similarities between new and previously learned concepts, or reflection journals where they document connections across different topics. The key is making the transfer process visible and deliberate rather than hoping it will occur naturally.

Learning transfer manifests in several distinct forms that educators must recognise to design effective teaching strategies. Near transfer occurs when students apply knowledge to similar contexts, such as using multiplication skills learnt with whole numbers to solve decimal problems. In contrast, far transfer involves applying learning to vastly different situations, like using scientific reasoning skills developed in biology lessons to analyse historical evidence. Research by Barnett and Ceci demonstrates that far transfer is significantly more challenging to achieve but offers greater educational value.

The direction of transfer also varies considerably. Positive transfer occurs when prior learning facilitates new learning, such as when students' understanding of fractions supports their grasp of percentages. However, negative transfer can hinder progress, as when students incorrectly apply familiar grammatical rules from their first language to a second language. Additionally, Gentner's work highlights the distinction between literal transfer, where surface similarities guide application, and figural transfer, where students recognise deeper structural patterns across different contexts.

Understanding these transfer types enables teachers to scaffold learning more effectively. Promote near transfer by providing varied practice within similar contexts before introducing far transfer challenges. Address potential negative transfer by explicitly discussing when familiar strategies may not apply, and encourage figural transfer by helping students identify underlying principles rather than focusing solely on surface features.

Several cognitive and contextual factors create significant barriers to successful learning transfer in educational settings. Surface-level learning represents one of the most prevalent obstacles, where students memorise facts and procedures without developing deep conceptual understanding. When learners focus solely on reproducing knowledge for assessments rather than grasping underlying principles, they struggle to apply their learning to novel situations or different contexts.

Cognitive load theory, as developed by John Sweller, reveals another critical barrier: cognitive overload during initial learning. When students are overwhelmed with too much information or overly complex tasks, their working memory capacity becomes saturated, preventing the formation of robust mental schemas necessary for transfer. Additionally, inadequate practice with varied examples limits students' ability to recognise when and how their knowledge applies to new problems.

Contextual factors also significantly impede transfer, particularly when there are substantial differences between learning and application environments. Students often develop context-dependent knowledge that remains tied to specific situations, teachers, or classroom arrangements. To overcome these barriers, educators should emphasise conceptual understanding over rote memorisation, provide multiple examples across varied contexts, and explicitly highlight connections between different learning situations to help students recognise transferable principles.

Assessing learning transfer requires teachers to move beyond traditional knowledge-recall tests towards evaluating students' ability to apply learning in novel contexts. Effective assessment strategies should examine whether students can recognise patterns, adapt strategies, and solve problems that differ from their original learning situations. This means designing tasks that present familiar concepts in unfamiliar formats or asking students to apply classroom learning to real-world scenarios.

Performance-based assessments offer particularly valuable insights into transfer effectiveness. Teachers can observe students working through complex, multi-step problems that require drawing connections between different topics or subjects. Portfolio assessments allow educators to track transfer development over time, whilst peer teaching activities reveal whether students can explain concepts in ways that demonstrate deep understanding rather than mere memorisation.

Formative assessment techniques, such as exit tickets asking "How might today's learning connect to yesterday's lesson?" or reflective journals exploring cross-curricular links, provide ongoing evidence of transfer. Teachers should also consider delayed assessments, testing concepts weeks after initial instruction to gauge retention and application. As Dylan Wiliam's research on formative assessment suggests, regular feedback loops help both teachers and students understand when genuine learning transfer has occurred.

Mathematical problem-solving strategies demonstrate powerful learning transfer when students apply algebraic thinking to science investigations. For instance, when pupils learn to identify variables and constants in mathematics, they can transfer this analytical framework to control variables in physics experiments or balance chemical equations. Similarly, the logical reasoning developed through geometric proofs enhances students' ability to construct persuasive arguments in history essays, as both require systematic evidence gathering and sequential reasoning.

Language arts skills transfer effectively across the curriculum when students apply critical reading strategies to interpret data in geography or analyse primary sources in history. The comprehension techniques taught for literary texts, such as identifying main ideas and supporting evidence, prove invaluable when students encounter complex scientific texts or evaluate historical documents. Research by David Perkins suggests that teaching students to recognise these underlying thinking patterns across subjects significantly improves transfer outcomes.

To maximise subject-specific transfer, teachers should explicitly highlight the connections between skills used in different contexts. When introducing a new concept, reference how similar thinking processes apply elsewhere in the curriculum. For example, pattern recognition skills developed in mathematics can be linked to identifying trends in data analysis across science subjects, helping students recognise the transferable nature of their learning.