Higher-Order Thinking Skills

How can we enhance the quality of thinking in our classrooms, and what strategies can we use to promote higher-order thinking?

How can we enhance the quality of thinking in our classrooms, and what strategies can we use to promote higher-order thinking?

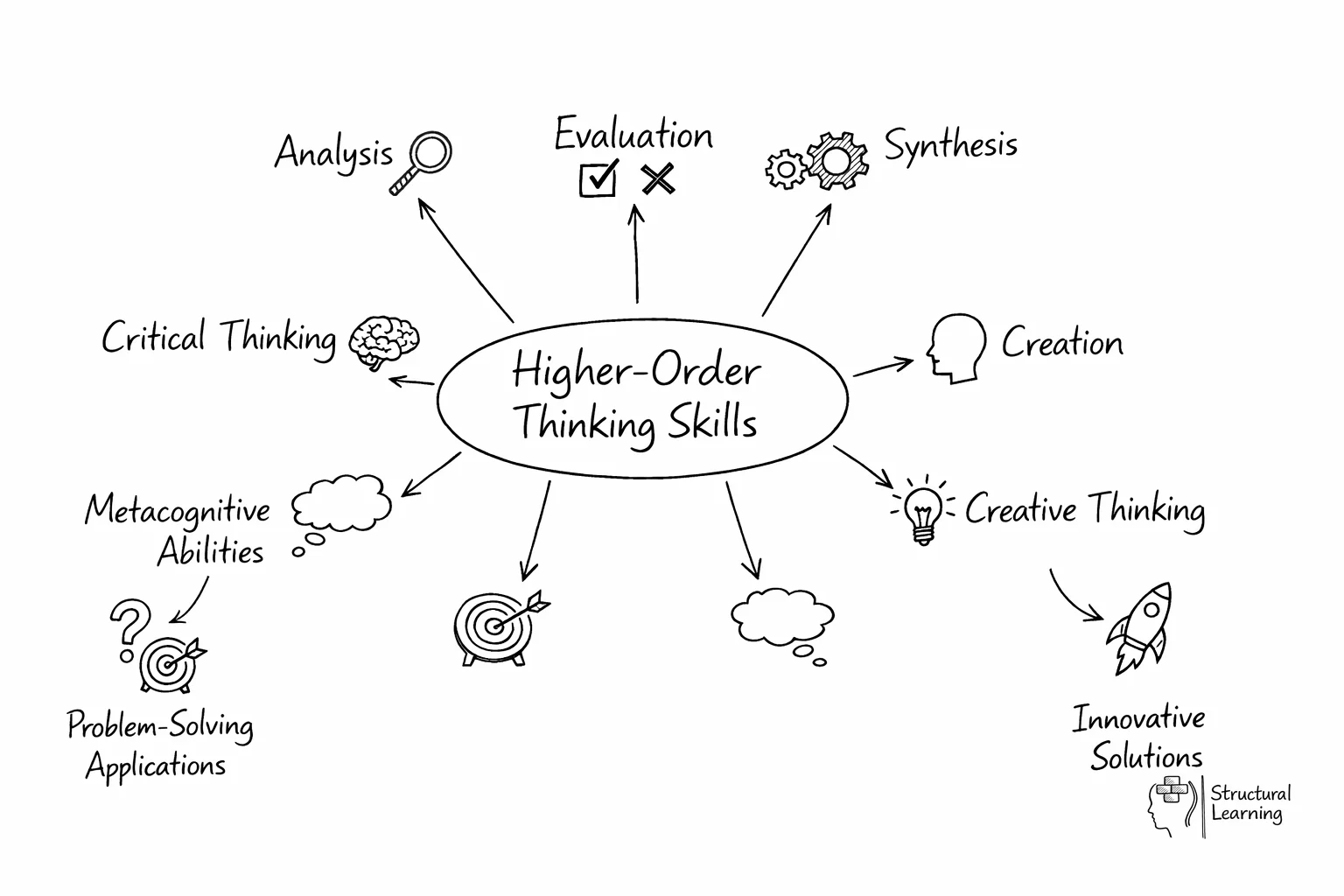

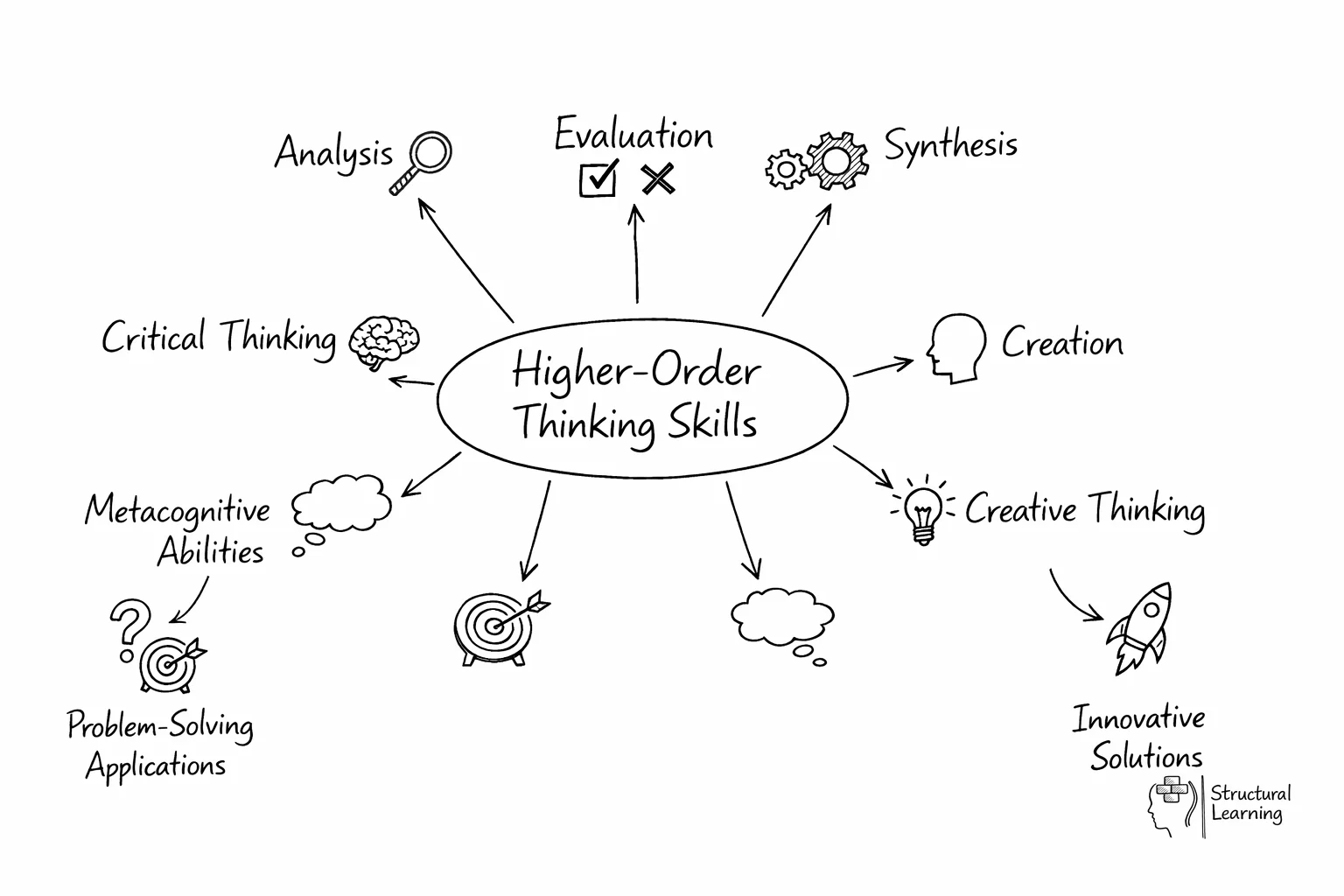

Higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) are cognitive abilities that go beyond basic memorization and comprehension, including analysis, evaluation, synthesis, and creation. These skills enable students to solve complex problems, make connections between ideas, and apply knowledge in new situations. They encompass critical thinking, creative thinking, and metacognitive abilities that help students think deeply about content.

practical strategies for developing higher-order thinking skills in educational settings" loading="lazy">

practical strategies for developing higher-order thinking skills in educational settings" loading="lazy">Higher-order (AI literacy as a higher-order skill) thinking skills can be traced back to Socrates and Plato, when problem-solving was linked to critical thinking. Higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) are something that has been well-researched and is something we are led to aspire to in our classrooms.

Research suggests higher-order thinking skills promote student success and achievement, giving them a wealth of transferable skills. It is often documented and evaluated in observed sessions as the questioning techniques teachers use to support learning.

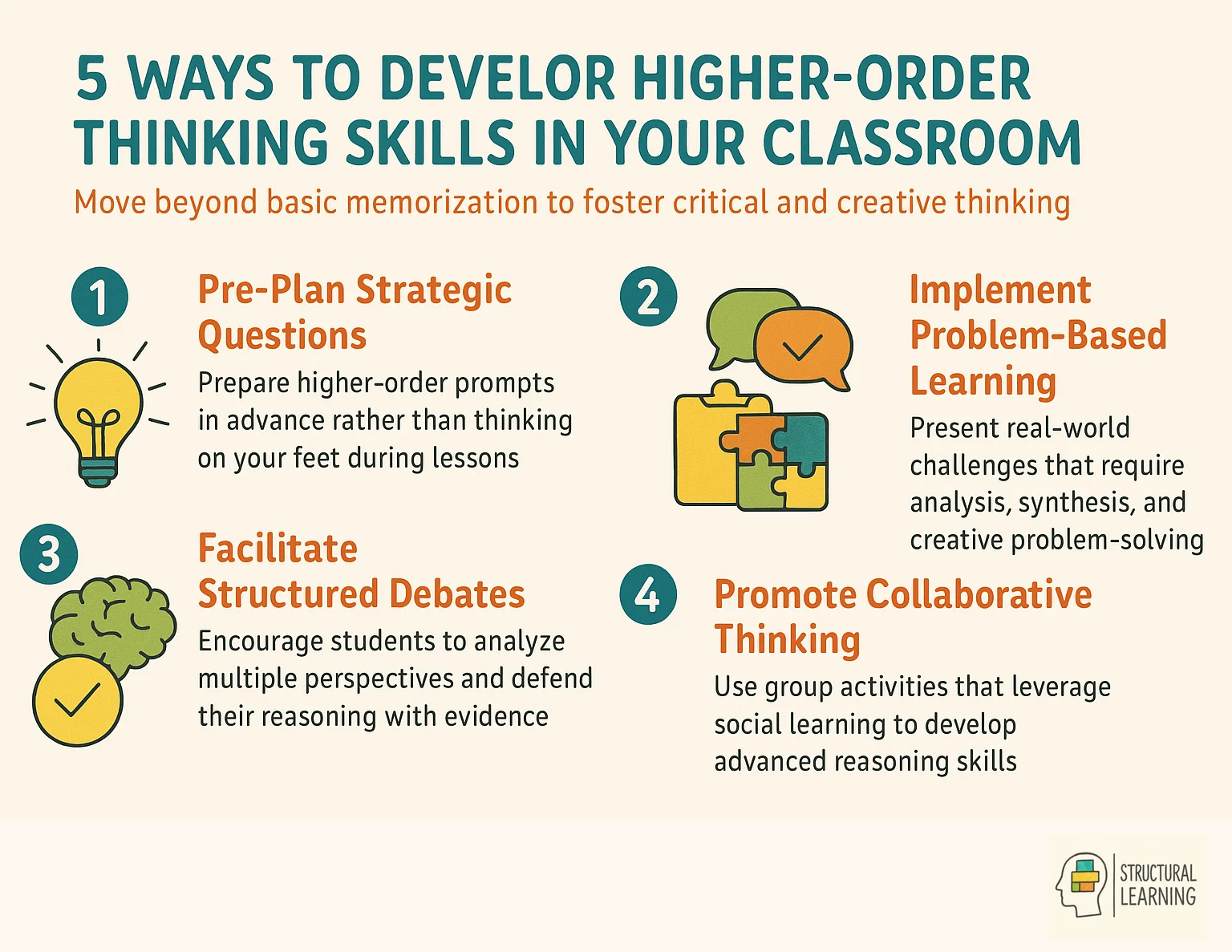

However, questions are only one way to promote higher-order skills. Whether using mathematical thinking questions or other approaches such as debate, problem-based learning and constructing meaning from materials presented, there are many ways to develop these abilities.

Higher-order thinking skills can be used in educational settings as a way to support student learning. Instructors and teachers can design instructional activities that require students to use problem-solving, critical thinking, decision making and evaluation to learn a subject more effectively.

By doing so, they can promote higher-order thinking skills that enable students to think beyond the basics and apply their learning in more meaningful ways. This could help equip students with 21st-century skills they can carry throughout their lives.

Research on higher-order thinking skills is mainly conducted through cross-sectional studies, which compare a specific group of students at different points in time to track the development of their cognitive abilities. These studies have revealed that when given the right opportunity and resources to develop their thinking skills, students demonstrate tremendous growth over a short period of time.

In this article, we will explore how fluid reasoning skills can be used to promote the acquisition of knowledge needed to understand abstract concepts in our curriculum.

Higher-order thinking skills, such as convergent thinking, creative thinking, and analytical thinking, are essential for students to develop in order to succeed . The learning process in classrooms should prioritise the nurturing of these skills, as they allow students to tackle complex problems, understand abstract concepts and synthesize knowledge from various sources.

Exploratory activities that promote creative thinking, especially in problem-solving, can be particularly valuable to students. They help students to think outside the box and to develop original ideas. It encourages them to take risks and experiment with various solutions, which are skills that they can use in everyday life, as well as real-life situations.

Analytical thinking skills are also important, as they enable students to break down complex problems and to understand the underlying process concepts. This makes it easier for students to manage information and make informed decisions. These skills can also help students to better understand and interpret abstract concepts, which can be particularly challenging for some students.

In order to promote higher-order thinking skills, educators can incorporate activities that creates analytical, creative and convergent thinking. Group activities, debates and problem-solving activities are particularly effective in promoting these skills. It is also important for students to have access to a diverse range of resources and to have the opportunity to collaborate with their peers. By nurturing these critical higher-order thinking skills, students will be better prepared to tackle challenges, solve problems, and succeed in the ever-evolving world.

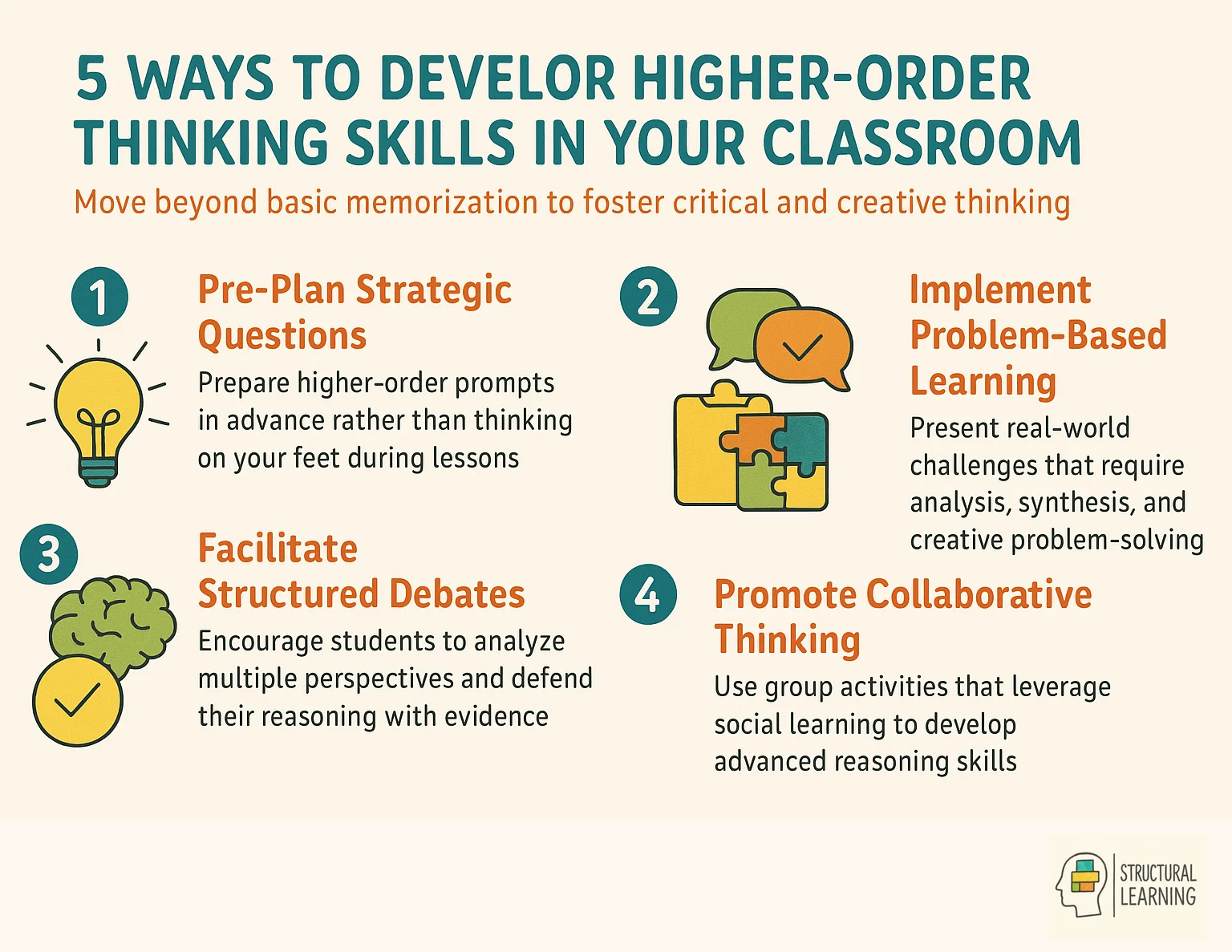

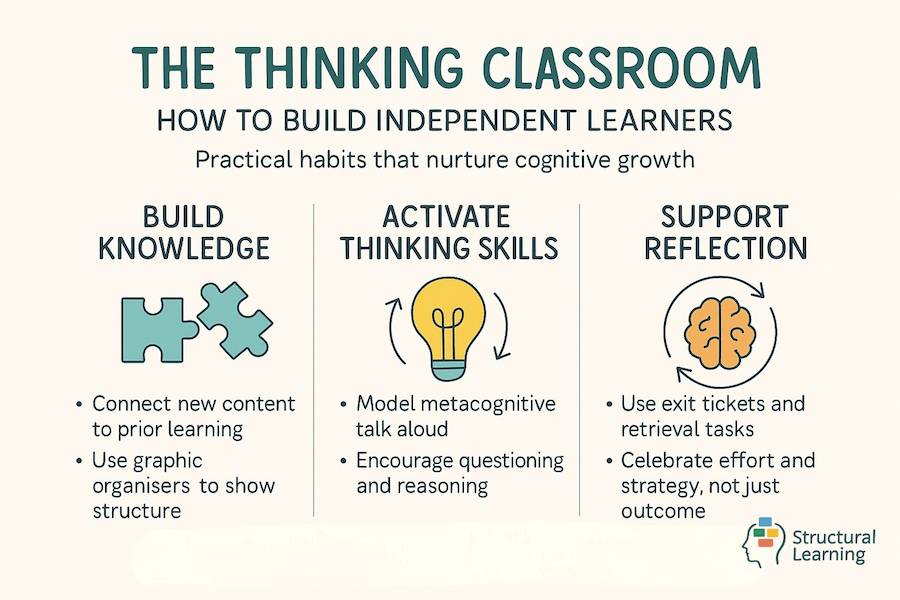

Teachers promote higher-order thinking by using open-ended questions, problem-based learning activities, and collaborative discussions that challenge students to analyse and evaluate information. Pre-planning higher-order questions before lessons ensures more effective questioning than thinking on your feet. Additional strategies include debates, case studies, project-based learning, and activities that require students to create, design, or construct meaning from materials.

We seek to promote higher-order thinking skills that will enable our students to justify their ideas to themselves and others. They are essentially those of evaluation, criticality and justification that students must develop through practice.

This involves the teacher providing opportunities for debate and critical reflection. Teachers, therefore, should look to providing materials before a lesson or sourcing materials before the session to facilitate rather than teach content directly.

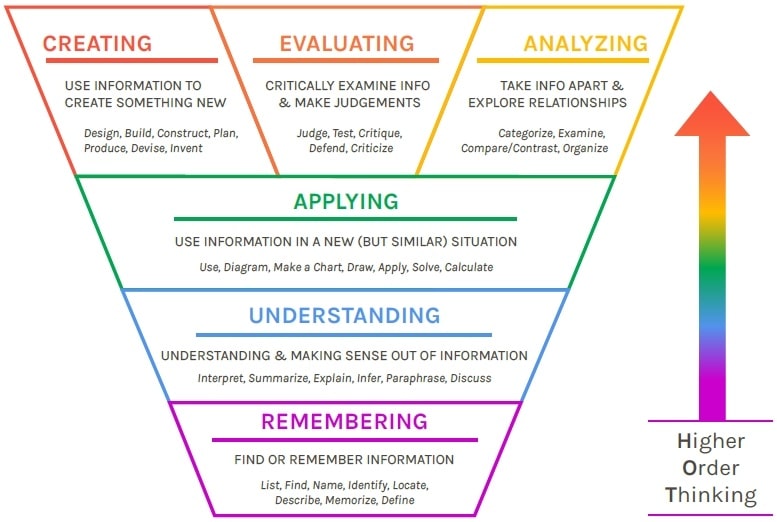

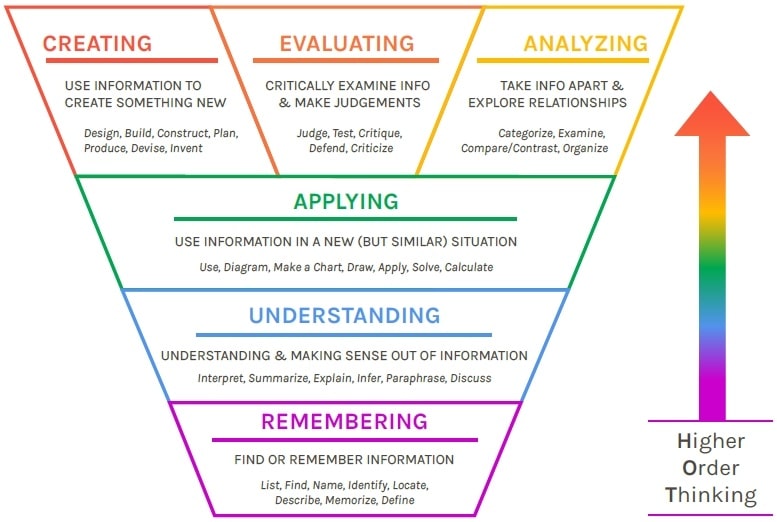

Higher-order thinking skills are linked to stretch, challenge, differentiation, and active learning techniques. They are also associated with Bloom's taxonomy and can therefore be related to supporting children's early development of cognitive skills. Ennis (1987) states that Bloom's analysis, synthesis and evaluation skills should be considered Higher Order skills. This is a valuable idea but can confuse the teacher by applying such categorisation.

Much of the research points to higher-order skills being more incidental in the classroom rather than a thought-out strategy that promotes thinking through a problem to sustain a line of reasoning or justify their ideas.

One way we can encourage questioning that is higher order is to think before our sessions about what questions we want to ask our students based on the pre-planned content. Using this simple strategy will then support teachers to not just think on their feet with questions but think in advance of how to help thinking, allowing them to utilise their pedagogical content knowledge.

Definitions encompass constructivism principles such as fluidity of thought, complex problem solving and interacting with the world around us to develop new concepts, as Dewey (1938) advocates.

Further, Vygotsky argued that higher mental abilities could only develop through interaction with others. He, therefore, proposed that children are born with elementary cognitive skills such as memory and perception and that higher mental functions develop from these through the influence of social interactions.

Higher-order thinking skills give students transferable abilities that promote academic success and prepare them for real-world challenges beyond school. Research shows these skills enable students to think critically, solve complex problems, and make informed decisions throughout their lives. Students with strong HOTS perform better academically and develop the 21st-century competencies needed for future careers.

Having a rich repertoire of thinking skills can help students express themselves more clearly. Possessing a range of thinking skills enables learners to construct deeper meaning and comprehension.

Using such tools as the Frayer model or CREATE can help to support understanding. By engaging in metacognition strategies, students will retain information and be better able to use and apply it to new situations. Developing levels of thinking beyond lower-order thinking skills is something that requires practice. Practitioners should therefore seek to find situations to support collaborative learning as, like everything, requires practice.

Suppose the course is carefully designed around student-learning outcomes, and some of those outcomes have a robust critical-thinking component. In that case, the final assessment of your student's success at achieving the outcomes will be evidence of their critical thinking ability.

Multiple-choice exams are good at detecting the key facts, but they don't go any deeper than that. Students need to use the new knowledge in productive ways to showcase their full breadth of understanding.

As Schulz ( 2016) and Resnick (2001) point out, this may have a detriment on learning as students who have not been taught a demanding, challenging, thinking curriculum do poorly on tests of reasoning or problem. Heong (2012) cautions us that students with weak thinking skills cannot effectively perform cognitive and metacognitive-based tasks. They are therefore placed at a disadvantage in the education system.

Higher-order thinking skills are an approach in education that separates critical thinking techniques from low-order learning approaches, such as rote and memorisation. By promoting higher-order thinking, students are supported to understand, categorise, manipulate, infer, connect and apply information.

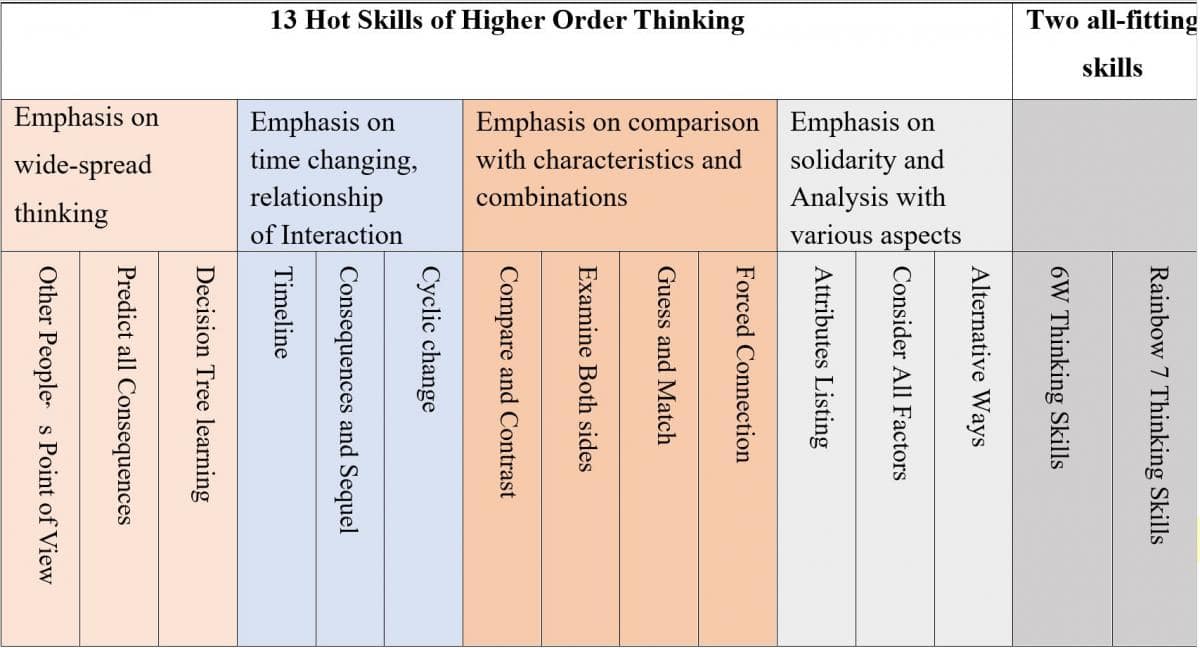

Teachers who plan to teach and extend students' higher-order thinking skills promote growth for their students. Higher-order thinking is promoted through a range of skills :

Transfer of knowledge , the student's ability to apply knowledge and skills to new contexts (for example, a student in learning about fractions applied his/her knowledge to a real-world scenario)

Critical thinking, the ability to reason, reflect, and decide what to believe or do next through analysis of text, reports and debate. Instead of taking things at face value, a critical thinker uses logic and reason to evaluate the information.

Problem-solving, meeting a goal that cannot be met with a memorised solution (Brookhart, 2010, 2011). This will involve planning through cooperative learning techniques. This technique requires a leap of faith in that students should control the planning, direction and organisation of a task or problem.

Create something new, we are going beyond receiving and evaluating knowledge. We move up to generate new knowledge based on our experiences and intellect.

Lateral thinking - Lateral thinkers take alternative routes to develop under-utilised or creative solutions to problems. ‘Lateral’ means to approach from the side rather than head-on.

Divergent thinking - Divergent thinking refers to the process of generating multiple possible ideas from one question. It is common when we engage in brainstorming, and it allows people to find creative solutions to problems.

Convergent thinking - Convergent thinking is about gathering facts to come up with an answer or solution.

Counterfactual thinking - Counterfactual thinking involves asking “what if?” questions in order to think of alternatives that may have happened if there were small changes made here and there. It is useful for reflective thinking and self-improvement.

Synthesizing - When we synthesize information, we gather information from multiple sources, identifying trends and themes and bringing it together into one review or evaluation of the knowledge base.

Invention - Invention occurs when something entirely new is created for the first time. For this to occur, a person must have a thorough understanding of existing knowledge and the critical and creative thinking skills to build upon it.

Metacognition- Metacognition refers to “thinking about thinking”. It’s a thinking skill that involves reflecting on your thinking processes and how you engaged with a task to seek improvements in your own thinking processes.

Evaluation - Evaluation goes beyond reading for understanding. It moves up to the level of assessing the correctness, quality, or merits of information presented to you.

Abstract thinking - Abstraction refers to engaging with ideas in theoretical rather than practical ways. The step up from learning about practical issues to applying practical knowledge to abstract, theoretical, and hypothetical contexts is considered higher-order.

Identifying logical fallacies, students are asked to look at arguments and critique their use of logic.

Open-ended questioning: Instead of asking yes/no questions, teachers try to ask questions requiring full-sentence responses. This can lead students to think through and articulate responses based on critique and analysis rather than simple memorization.

Active learning: By contrast, when students actually complete tasks themselves, they are engaging in active learning.

High expectations: This involves the teacher insisting students try their hardest in all situations. Often, low expectations allow students to ‘coast along’ with simple memorization and understanding and don’t ask them to extend their knowledge.

Scaffolding and modelled instruction: Often, students don’t fully understand how to engage in higher-order thinking. To address this, teachers demonstrate how to think at a high level, then put in place scaffolds like question cards and instruction sheets that direct students toward higher levels of thinking.

Critics argue that rigidly categorising thinking skills through frameworks like Bloom's Taxonomy can actually limit student potential by creating artificial boundaries between cognitive processes. Traditional assessments like multiple-choice tests often fail to measure genuine critical thinking abilities and application of knowledge. Some educators find that focusing too heavily on HOTS classifications can distract from the natural, fluid way students actually develop complex thinking abilities.

There are two central critiques of the concept of higher-order thinking and its applications in education:

It is not linear: Sometimes, lower-order thinking is challenging and requires great skill, while other higher-order tasks can be objectively much easier. For example, the ability to simply follow a piece of logic in a graduate-level physics class (supposedly lower-order) requires much greater cognitive skill than the ability to create something in a grade 7 math class (creativity being higher-order). Thus, simply engaging in higher-order thinking doesn’t tell us everything we should know about someone’s cognitive and intellectual capacity.

Focus on thinking rather than outcomes: John Biggs argues that the use of Bloom’s taxonomy is insufficient for curriculum design because it focuses on often unassessable internal cognitive processes rather than the outcomes of those processes.

Technology enables students to engage with complex problems through simulations, collaborative digital platforms, and access to vast information resources that require evaluation and synthesis. Digital tools allow teachers to create interactive activities that challenge students to analyse data, create multimedia projects, and solve real-world problems. Online collaboration tools particularly support the social learning aspect that Vygotsky's research shows is essential for developing advanced reasoning skills.

The digital revolution has had a profound impact on the development of higher-order thinking skills in the classroom, transforming traditional teaching methods and expanding the horizons of both educators and students.

The introduction of effective platforms such as White Rose Maths, Hegarty Maths, and TTRS has developed a synthesis of knowledge, smoothly merging cognitive processing with student-learning outcomes. These platforms, akin to the interconnected neurons in the brain, enable students to connect the dots between previously unrelated concepts, promoting deeper understanding and critical thinking.

The application of cooperative learning techniques, facilitated by technology, has redefined the way students engage with concrete concepts and navigate the various levels of the solo taxonomy. By encouraging collaboration and the sharing of diverse perspectives, technology helps learners to explore complex ideas in a multidimensional manner.

This process mirrors the construction of a vibrant mosaic, where each individual contributes a unique piece to form a coherent and comprehensive image.

In this new era of digital learning, educators must embrace technology as a powerful tool to enhance higher-order thinking skills. Research by Kozma (1991), Jonassen and Reeves (1996), and Wenglinsky (1998)highlights the potential of technology to improve critical thinking, problem-solving, and communication abilities in students.

By incorporating these dynamic resources into the classroom, teachers can create an enriching environment that creates the growth of cognitive abilities and ensures students are well-equipped to navigate the challenges of the 21st century.

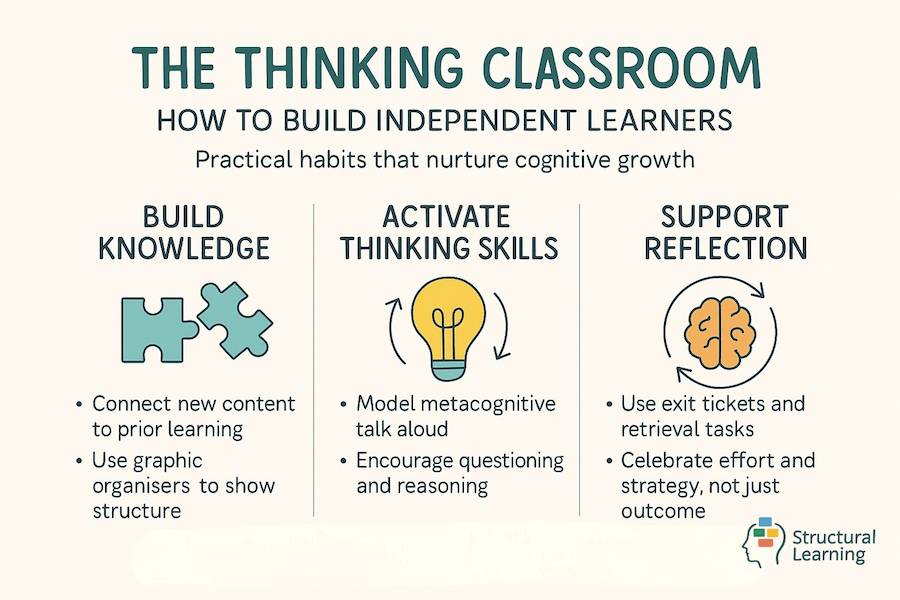

Schools can promote deeper cognition by establishing consistent questioning frameworks across all subjects and grade levels, ensuring teachers pre-plan higher-order prompts. Professional development should focus on moving beyond traditional assessments to alternative evaluation methods that reveal true student understanding. Creating a culture of collaborative learning and problem-based activities across departments helps embed critical thinking as a core educational value.

Strategies that teachers may use in their classes to encourage higher-order and critical thinking skills include:

Posing provocative questions, statements or scenarios to generate discussion (for example, the use of 'what if' questions). The questioning matrix is a very useful tool.

Requiring students to explain concepts using analogies, similes and metaphors. This requires the teacher to unpick words, find alternatives and allow students to construct their own meaning from the content presented.

Posing problems with no single solution or multiple pathways to a solution. This approach involves learners being given the time and space to complete a task and be supported to 'fail' at finding a solution. Developing problem-solving skills requires developing resilience in students to enable them to fail at a task.

Modelling a range of problem-solving strategies using concept mapping to assist students in making connections between and within ideas.

Posing paradoxes for students to consider (for example: In a study of World War 1, students can be presented with the statement: 'War nurses saved lives, but they also contributed to deaths') creating an 'I wonder' wall in your classroom: depth of knowledge table (informed by Webb 2002)

Developing higher-order thinking skills with our students enables them to assess, evaluate, apply and synthesise information. These skills enhance comprehension, which makes communication more effective. Which, in turn, will support students to achieve in the education system.

Key resources include research on Vygotsky's social learning theory, which emphasises collaborative approaches to developing advanced reasoning skills. Teachers should explore alternatives to Bloom's Taxonomy that promote fluid thinking development rather than rigid categorisation. Professional books and journals on problem-based learning, critical thinking pedagogy, and 21st-century skill development provide practical strategies for classroom implementation.

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P. W., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R., Pintrich, P. R., Raths, J. D., & Wittrock, M. C. (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom‘s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain. New York: McKay, 20, 24.

Bloom, B.S. (Ed.), Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., & Krathwohl, D.R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay.

Byrne, R. M. J. (2005). The rational imagination: How people create alternatives to reality. MA: MIT Press.

Cannella, G. S., & Reiff, J. C. (1994). Individual constructivist teacher education: Teachers as helped learners. Teacher education quarterly, 27-38.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Macmillan.

Eber, P. A., & Parker, T. S. (2007). Assessing Student Learning: Applying Bloom’s Taxonomy. Human Service Education, 27(1).

Flinders, D., & Thornton, S. (2013). The curriculum studies reader. (4th Ed.). New York: Routledge.

Golsby-Smith, Tony (1996). Fourth order design: A practical perspective. Design Issues, 12(1), 5-25. Https://doi.org/10.2307/1511742

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212-218.

Additionally, here are five key studies exploring higher order thinking skills (HOTS) and their implications in the classroom, providing diverse perspectives on how researchers have explored this notion and promoted it in educational settings:

These studies collectively underscore the critical role of HOTS in contemporary education, illustrating various strategies for enhancing these skills among students across different subjects and educational levels.

Higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) are cognitive abilities that go beyond basic memorisation and comprehension, including analysis, evaluation, synthesis, and creation. These skills enable students to solve complex problems, make connections between ideas, and apply knowledge in new situations, rather than simply recalling facts.

Teachers should pre-plan higher-order questions before lessons rather than thinking on their feet, and incorporate activities like debates, problem-based learning, and collaborative discussions. Additional effective strategies include case studies, project-based learning, and activities that require students to create, design, or construct meaning from materials.

Traditional multiple-choice assessments typically focus on memorisation and basic comprehension rather than critical thinking abilities. These assessments miss students' capacity for analysis, evaluation, and application of knowledge in new situations, which are the core components of higher-order thinking.

Vygotsky's research demonstrates that higher mental abilities can only develop through interaction with others, making isolated thinking tasks ineffective. Collaborative activities, group discussions, and peer interaction are essential for developing advanced reasoning skills and critical thinking abilities.

Rather than rigidly categorising thinking skills into levels, teachers should adopt a more fluid approach that recognises the interconnected nature of cognitive abilities. This means focusing on activities that require students to justify their ideas, engage in critical reflection, and sustain lines of reasoning across different contexts.

Teachers can organise debates on controversial topics, design problem-solving challenges that require multiple approaches, and create projects where students must synthesise information from various sources. Other effective activities include case study analyses, exploratory tasks that promote creative thinking, and assignments requiring students to evaluate and justify their conclusions.

These skills provide students with transferable abilities that promote academic success and prepare them for real-world challenges beyond school. Research shows that students with well-developed higher-order thinking skills can tackle complex problems, understand abstract concepts, and make informed decisions throughout their lives, equipping them with crucial 21st-century skills.

Higher-order thinking research

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into higher-order thinking skills and its application in educational settings.

Mind Mapping in Learning Models: A Tool to Improve Student Metacognitive Skills View study ↗64 citations

Astriani et al. (2020)

This study examines how mind mapping techniques can be integrated into learning models to enhance students' metacognitive skills, which involve students' awareness and understanding of their own thinking processes. The research demonstrates that mind mapping serves as an effective tool for helping students monitor and regulate their own learning. This is valuable for teachers because metacognitive skills are fundamental to higher-order thinking, enabling students to plan, evaluate, and adjust their problem-solving strategies.

Impact of ePortfolios on Science student-teachers' reflective metacognitive learning and the development of higher-order thinking skills View study ↗16 citations

Jager et al. (2019)

This research investigates how digital portfolios (ePortfolios) can promote reflective thinking and metacognitive learning among science student-teachers while developing their higher-order thinking skills. The study addresses the concern that many students in higher education fail to develop critical thinking abilities and remain passive learners. Teachers will find this relevant as it provides evidence for using digital tools to creates reflection and self- regulated learning, which are essential components of higher-order thinking development.

Artificial Intelligence Supporting Independent Student Learning: An Evaluative Case Study of ChatGPT and Learning to Code View study ↗57 citations

Hartley et al. (2024)

This study explores how ChatGPT and similar AI tools can support students in developing self-regulated learning skills, particularly in learning computer programming. The research examines AI's potential to provide personalized, adaptive learning experiences that help students become more independent learners. This is relevant for teachers as it demonstrates how AI can be used as a tool to develop students' metacognitive abilities and higher-order thinking skills through guided, self-directed learning experiences.

Integrating creative pedagogy into problem-based learning: The effects on higher order thinking skills in science education View study ↗53 citations

Affandy et al. (2024)

This research examines how combining creative teaching methods with problem-based learning approaches can enhance students' higher-order thinking skills in science education. The study demonstrates that integrating creativity into structured problem-solving activities produces measurable improvements in students' analytical and evaluative thinking abilities. Teachers will find this valuable as it provides evidence-based strategies for designing learning experiences that simultaneously engage students' creativity and develop their critical thinking skills.

A Systematic Assessment of OpenAI o1-Preview for Higher Order Thinking in Education View study ↗24 citations

Latif et al. (2024)

This comprehensive study evaluates OpenAI's o1-preview model across 14 different dimensions to assess its capability in performing higher-order cognitive tasks that are typically required in educational settings. The research provides insights into how advanced AI systems can demonstrate complex reasoning abilities comparable to human intelligence in educational contexts. This is relevant for teachers as it helps them understand the current capabilities and limitations of AI tools in supporting or assessing higher-order thinking skills in their classrooms.

Higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) are cognitive abilities that go beyond basic memorization and comprehension, including analysis, evaluation, synthesis, and creation. These skills enable students to solve complex problems, make connections between ideas, and apply knowledge in new situations. They encompass critical thinking, creative thinking, and metacognitive abilities that help students think deeply about content.

practical strategies for developing higher-order thinking skills in educational settings" loading="lazy">

practical strategies for developing higher-order thinking skills in educational settings" loading="lazy">Higher-order (AI literacy as a higher-order skill) thinking skills can be traced back to Socrates and Plato, when problem-solving was linked to critical thinking. Higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) are something that has been well-researched and is something we are led to aspire to in our classrooms.

Research suggests higher-order thinking skills promote student success and achievement, giving them a wealth of transferable skills. It is often documented and evaluated in observed sessions as the questioning techniques teachers use to support learning.

However, questions are only one way to promote higher-order skills. Whether using mathematical thinking questions or other approaches such as debate, problem-based learning and constructing meaning from materials presented, there are many ways to develop these abilities.

Higher-order thinking skills can be used in educational settings as a way to support student learning. Instructors and teachers can design instructional activities that require students to use problem-solving, critical thinking, decision making and evaluation to learn a subject more effectively.

By doing so, they can promote higher-order thinking skills that enable students to think beyond the basics and apply their learning in more meaningful ways. This could help equip students with 21st-century skills they can carry throughout their lives.

Research on higher-order thinking skills is mainly conducted through cross-sectional studies, which compare a specific group of students at different points in time to track the development of their cognitive abilities. These studies have revealed that when given the right opportunity and resources to develop their thinking skills, students demonstrate tremendous growth over a short period of time.

In this article, we will explore how fluid reasoning skills can be used to promote the acquisition of knowledge needed to understand abstract concepts in our curriculum.

Higher-order thinking skills, such as convergent thinking, creative thinking, and analytical thinking, are essential for students to develop in order to succeed . The learning process in classrooms should prioritise the nurturing of these skills, as they allow students to tackle complex problems, understand abstract concepts and synthesize knowledge from various sources.

Exploratory activities that promote creative thinking, especially in problem-solving, can be particularly valuable to students. They help students to think outside the box and to develop original ideas. It encourages them to take risks and experiment with various solutions, which are skills that they can use in everyday life, as well as real-life situations.

Analytical thinking skills are also important, as they enable students to break down complex problems and to understand the underlying process concepts. This makes it easier for students to manage information and make informed decisions. These skills can also help students to better understand and interpret abstract concepts, which can be particularly challenging for some students.

In order to promote higher-order thinking skills, educators can incorporate activities that creates analytical, creative and convergent thinking. Group activities, debates and problem-solving activities are particularly effective in promoting these skills. It is also important for students to have access to a diverse range of resources and to have the opportunity to collaborate with their peers. By nurturing these critical higher-order thinking skills, students will be better prepared to tackle challenges, solve problems, and succeed in the ever-evolving world.

Teachers promote higher-order thinking by using open-ended questions, problem-based learning activities, and collaborative discussions that challenge students to analyse and evaluate information. Pre-planning higher-order questions before lessons ensures more effective questioning than thinking on your feet. Additional strategies include debates, case studies, project-based learning, and activities that require students to create, design, or construct meaning from materials.

We seek to promote higher-order thinking skills that will enable our students to justify their ideas to themselves and others. They are essentially those of evaluation, criticality and justification that students must develop through practice.

This involves the teacher providing opportunities for debate and critical reflection. Teachers, therefore, should look to providing materials before a lesson or sourcing materials before the session to facilitate rather than teach content directly.

Higher-order thinking skills are linked to stretch, challenge, differentiation, and active learning techniques. They are also associated with Bloom's taxonomy and can therefore be related to supporting children's early development of cognitive skills. Ennis (1987) states that Bloom's analysis, synthesis and evaluation skills should be considered Higher Order skills. This is a valuable idea but can confuse the teacher by applying such categorisation.

Much of the research points to higher-order skills being more incidental in the classroom rather than a thought-out strategy that promotes thinking through a problem to sustain a line of reasoning or justify their ideas.

One way we can encourage questioning that is higher order is to think before our sessions about what questions we want to ask our students based on the pre-planned content. Using this simple strategy will then support teachers to not just think on their feet with questions but think in advance of how to help thinking, allowing them to utilise their pedagogical content knowledge.

Definitions encompass constructivism principles such as fluidity of thought, complex problem solving and interacting with the world around us to develop new concepts, as Dewey (1938) advocates.

Further, Vygotsky argued that higher mental abilities could only develop through interaction with others. He, therefore, proposed that children are born with elementary cognitive skills such as memory and perception and that higher mental functions develop from these through the influence of social interactions.

Higher-order thinking skills give students transferable abilities that promote academic success and prepare them for real-world challenges beyond school. Research shows these skills enable students to think critically, solve complex problems, and make informed decisions throughout their lives. Students with strong HOTS perform better academically and develop the 21st-century competencies needed for future careers.

Having a rich repertoire of thinking skills can help students express themselves more clearly. Possessing a range of thinking skills enables learners to construct deeper meaning and comprehension.

Using such tools as the Frayer model or CREATE can help to support understanding. By engaging in metacognition strategies, students will retain information and be better able to use and apply it to new situations. Developing levels of thinking beyond lower-order thinking skills is something that requires practice. Practitioners should therefore seek to find situations to support collaborative learning as, like everything, requires practice.

Suppose the course is carefully designed around student-learning outcomes, and some of those outcomes have a robust critical-thinking component. In that case, the final assessment of your student's success at achieving the outcomes will be evidence of their critical thinking ability.

Multiple-choice exams are good at detecting the key facts, but they don't go any deeper than that. Students need to use the new knowledge in productive ways to showcase their full breadth of understanding.

As Schulz ( 2016) and Resnick (2001) point out, this may have a detriment on learning as students who have not been taught a demanding, challenging, thinking curriculum do poorly on tests of reasoning or problem. Heong (2012) cautions us that students with weak thinking skills cannot effectively perform cognitive and metacognitive-based tasks. They are therefore placed at a disadvantage in the education system.

Higher-order thinking skills are an approach in education that separates critical thinking techniques from low-order learning approaches, such as rote and memorisation. By promoting higher-order thinking, students are supported to understand, categorise, manipulate, infer, connect and apply information.

Teachers who plan to teach and extend students' higher-order thinking skills promote growth for their students. Higher-order thinking is promoted through a range of skills :

Transfer of knowledge , the student's ability to apply knowledge and skills to new contexts (for example, a student in learning about fractions applied his/her knowledge to a real-world scenario)

Critical thinking, the ability to reason, reflect, and decide what to believe or do next through analysis of text, reports and debate. Instead of taking things at face value, a critical thinker uses logic and reason to evaluate the information.

Problem-solving, meeting a goal that cannot be met with a memorised solution (Brookhart, 2010, 2011). This will involve planning through cooperative learning techniques. This technique requires a leap of faith in that students should control the planning, direction and organisation of a task or problem.

Create something new, we are going beyond receiving and evaluating knowledge. We move up to generate new knowledge based on our experiences and intellect.

Lateral thinking - Lateral thinkers take alternative routes to develop under-utilised or creative solutions to problems. ‘Lateral’ means to approach from the side rather than head-on.

Divergent thinking - Divergent thinking refers to the process of generating multiple possible ideas from one question. It is common when we engage in brainstorming, and it allows people to find creative solutions to problems.

Convergent thinking - Convergent thinking is about gathering facts to come up with an answer or solution.

Counterfactual thinking - Counterfactual thinking involves asking “what if?” questions in order to think of alternatives that may have happened if there were small changes made here and there. It is useful for reflective thinking and self-improvement.

Synthesizing - When we synthesize information, we gather information from multiple sources, identifying trends and themes and bringing it together into one review or evaluation of the knowledge base.

Invention - Invention occurs when something entirely new is created for the first time. For this to occur, a person must have a thorough understanding of existing knowledge and the critical and creative thinking skills to build upon it.

Metacognition- Metacognition refers to “thinking about thinking”. It’s a thinking skill that involves reflecting on your thinking processes and how you engaged with a task to seek improvements in your own thinking processes.

Evaluation - Evaluation goes beyond reading for understanding. It moves up to the level of assessing the correctness, quality, or merits of information presented to you.

Abstract thinking - Abstraction refers to engaging with ideas in theoretical rather than practical ways. The step up from learning about practical issues to applying practical knowledge to abstract, theoretical, and hypothetical contexts is considered higher-order.

Identifying logical fallacies, students are asked to look at arguments and critique their use of logic.

Open-ended questioning: Instead of asking yes/no questions, teachers try to ask questions requiring full-sentence responses. This can lead students to think through and articulate responses based on critique and analysis rather than simple memorization.

Active learning: By contrast, when students actually complete tasks themselves, they are engaging in active learning.

High expectations: This involves the teacher insisting students try their hardest in all situations. Often, low expectations allow students to ‘coast along’ with simple memorization and understanding and don’t ask them to extend their knowledge.

Scaffolding and modelled instruction: Often, students don’t fully understand how to engage in higher-order thinking. To address this, teachers demonstrate how to think at a high level, then put in place scaffolds like question cards and instruction sheets that direct students toward higher levels of thinking.

Critics argue that rigidly categorising thinking skills through frameworks like Bloom's Taxonomy can actually limit student potential by creating artificial boundaries between cognitive processes. Traditional assessments like multiple-choice tests often fail to measure genuine critical thinking abilities and application of knowledge. Some educators find that focusing too heavily on HOTS classifications can distract from the natural, fluid way students actually develop complex thinking abilities.

There are two central critiques of the concept of higher-order thinking and its applications in education:

It is not linear: Sometimes, lower-order thinking is challenging and requires great skill, while other higher-order tasks can be objectively much easier. For example, the ability to simply follow a piece of logic in a graduate-level physics class (supposedly lower-order) requires much greater cognitive skill than the ability to create something in a grade 7 math class (creativity being higher-order). Thus, simply engaging in higher-order thinking doesn’t tell us everything we should know about someone’s cognitive and intellectual capacity.

Focus on thinking rather than outcomes: John Biggs argues that the use of Bloom’s taxonomy is insufficient for curriculum design because it focuses on often unassessable internal cognitive processes rather than the outcomes of those processes.

Technology enables students to engage with complex problems through simulations, collaborative digital platforms, and access to vast information resources that require evaluation and synthesis. Digital tools allow teachers to create interactive activities that challenge students to analyse data, create multimedia projects, and solve real-world problems. Online collaboration tools particularly support the social learning aspect that Vygotsky's research shows is essential for developing advanced reasoning skills.

The digital revolution has had a profound impact on the development of higher-order thinking skills in the classroom, transforming traditional teaching methods and expanding the horizons of both educators and students.

The introduction of effective platforms such as White Rose Maths, Hegarty Maths, and TTRS has developed a synthesis of knowledge, smoothly merging cognitive processing with student-learning outcomes. These platforms, akin to the interconnected neurons in the brain, enable students to connect the dots between previously unrelated concepts, promoting deeper understanding and critical thinking.

The application of cooperative learning techniques, facilitated by technology, has redefined the way students engage with concrete concepts and navigate the various levels of the solo taxonomy. By encouraging collaboration and the sharing of diverse perspectives, technology helps learners to explore complex ideas in a multidimensional manner.

This process mirrors the construction of a vibrant mosaic, where each individual contributes a unique piece to form a coherent and comprehensive image.

In this new era of digital learning, educators must embrace technology as a powerful tool to enhance higher-order thinking skills. Research by Kozma (1991), Jonassen and Reeves (1996), and Wenglinsky (1998)highlights the potential of technology to improve critical thinking, problem-solving, and communication abilities in students.

By incorporating these dynamic resources into the classroom, teachers can create an enriching environment that creates the growth of cognitive abilities and ensures students are well-equipped to navigate the challenges of the 21st century.

Schools can promote deeper cognition by establishing consistent questioning frameworks across all subjects and grade levels, ensuring teachers pre-plan higher-order prompts. Professional development should focus on moving beyond traditional assessments to alternative evaluation methods that reveal true student understanding. Creating a culture of collaborative learning and problem-based activities across departments helps embed critical thinking as a core educational value.

Strategies that teachers may use in their classes to encourage higher-order and critical thinking skills include:

Posing provocative questions, statements or scenarios to generate discussion (for example, the use of 'what if' questions). The questioning matrix is a very useful tool.

Requiring students to explain concepts using analogies, similes and metaphors. This requires the teacher to unpick words, find alternatives and allow students to construct their own meaning from the content presented.

Posing problems with no single solution or multiple pathways to a solution. This approach involves learners being given the time and space to complete a task and be supported to 'fail' at finding a solution. Developing problem-solving skills requires developing resilience in students to enable them to fail at a task.

Modelling a range of problem-solving strategies using concept mapping to assist students in making connections between and within ideas.

Posing paradoxes for students to consider (for example: In a study of World War 1, students can be presented with the statement: 'War nurses saved lives, but they also contributed to deaths') creating an 'I wonder' wall in your classroom: depth of knowledge table (informed by Webb 2002)

Developing higher-order thinking skills with our students enables them to assess, evaluate, apply and synthesise information. These skills enhance comprehension, which makes communication more effective. Which, in turn, will support students to achieve in the education system.

Key resources include research on Vygotsky's social learning theory, which emphasises collaborative approaches to developing advanced reasoning skills. Teachers should explore alternatives to Bloom's Taxonomy that promote fluid thinking development rather than rigid categorisation. Professional books and journals on problem-based learning, critical thinking pedagogy, and 21st-century skill development provide practical strategies for classroom implementation.

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P. W., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R., Pintrich, P. R., Raths, J. D., & Wittrock, M. C. (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom‘s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain. New York: McKay, 20, 24.

Bloom, B.S. (Ed.), Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., & Krathwohl, D.R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay.

Byrne, R. M. J. (2005). The rational imagination: How people create alternatives to reality. MA: MIT Press.

Cannella, G. S., & Reiff, J. C. (1994). Individual constructivist teacher education: Teachers as helped learners. Teacher education quarterly, 27-38.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Macmillan.

Eber, P. A., & Parker, T. S. (2007). Assessing Student Learning: Applying Bloom’s Taxonomy. Human Service Education, 27(1).

Flinders, D., & Thornton, S. (2013). The curriculum studies reader. (4th Ed.). New York: Routledge.

Golsby-Smith, Tony (1996). Fourth order design: A practical perspective. Design Issues, 12(1), 5-25. Https://doi.org/10.2307/1511742

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212-218.

Additionally, here are five key studies exploring higher order thinking skills (HOTS) and their implications in the classroom, providing diverse perspectives on how researchers have explored this notion and promoted it in educational settings:

These studies collectively underscore the critical role of HOTS in contemporary education, illustrating various strategies for enhancing these skills among students across different subjects and educational levels.

Higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) are cognitive abilities that go beyond basic memorisation and comprehension, including analysis, evaluation, synthesis, and creation. These skills enable students to solve complex problems, make connections between ideas, and apply knowledge in new situations, rather than simply recalling facts.

Teachers should pre-plan higher-order questions before lessons rather than thinking on their feet, and incorporate activities like debates, problem-based learning, and collaborative discussions. Additional effective strategies include case studies, project-based learning, and activities that require students to create, design, or construct meaning from materials.

Traditional multiple-choice assessments typically focus on memorisation and basic comprehension rather than critical thinking abilities. These assessments miss students' capacity for analysis, evaluation, and application of knowledge in new situations, which are the core components of higher-order thinking.

Vygotsky's research demonstrates that higher mental abilities can only develop through interaction with others, making isolated thinking tasks ineffective. Collaborative activities, group discussions, and peer interaction are essential for developing advanced reasoning skills and critical thinking abilities.

Rather than rigidly categorising thinking skills into levels, teachers should adopt a more fluid approach that recognises the interconnected nature of cognitive abilities. This means focusing on activities that require students to justify their ideas, engage in critical reflection, and sustain lines of reasoning across different contexts.

Teachers can organise debates on controversial topics, design problem-solving challenges that require multiple approaches, and create projects where students must synthesise information from various sources. Other effective activities include case study analyses, exploratory tasks that promote creative thinking, and assignments requiring students to evaluate and justify their conclusions.

These skills provide students with transferable abilities that promote academic success and prepare them for real-world challenges beyond school. Research shows that students with well-developed higher-order thinking skills can tackle complex problems, understand abstract concepts, and make informed decisions throughout their lives, equipping them with crucial 21st-century skills.

Higher-order thinking research

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into higher-order thinking skills and its application in educational settings.

Mind Mapping in Learning Models: A Tool to Improve Student Metacognitive Skills View study ↗64 citations

Astriani et al. (2020)

This study examines how mind mapping techniques can be integrated into learning models to enhance students' metacognitive skills, which involve students' awareness and understanding of their own thinking processes. The research demonstrates that mind mapping serves as an effective tool for helping students monitor and regulate their own learning. This is valuable for teachers because metacognitive skills are fundamental to higher-order thinking, enabling students to plan, evaluate, and adjust their problem-solving strategies.

Impact of ePortfolios on Science student-teachers' reflective metacognitive learning and the development of higher-order thinking skills View study ↗16 citations

Jager et al. (2019)

This research investigates how digital portfolios (ePortfolios) can promote reflective thinking and metacognitive learning among science student-teachers while developing their higher-order thinking skills. The study addresses the concern that many students in higher education fail to develop critical thinking abilities and remain passive learners. Teachers will find this relevant as it provides evidence for using digital tools to creates reflection and self- regulated learning, which are essential components of higher-order thinking development.

Artificial Intelligence Supporting Independent Student Learning: An Evaluative Case Study of ChatGPT and Learning to Code View study ↗57 citations

Hartley et al. (2024)

This study explores how ChatGPT and similar AI tools can support students in developing self-regulated learning skills, particularly in learning computer programming. The research examines AI's potential to provide personalized, adaptive learning experiences that help students become more independent learners. This is relevant for teachers as it demonstrates how AI can be used as a tool to develop students' metacognitive abilities and higher-order thinking skills through guided, self-directed learning experiences.

Integrating creative pedagogy into problem-based learning: The effects on higher order thinking skills in science education View study ↗53 citations

Affandy et al. (2024)

This research examines how combining creative teaching methods with problem-based learning approaches can enhance students' higher-order thinking skills in science education. The study demonstrates that integrating creativity into structured problem-solving activities produces measurable improvements in students' analytical and evaluative thinking abilities. Teachers will find this valuable as it provides evidence-based strategies for designing learning experiences that simultaneously engage students' creativity and develop their critical thinking skills.

A Systematic Assessment of OpenAI o1-Preview for Higher Order Thinking in Education View study ↗24 citations

Latif et al. (2024)

This comprehensive study evaluates OpenAI's o1-preview model across 14 different dimensions to assess its capability in performing higher-order cognitive tasks that are typically required in educational settings. The research provides insights into how advanced AI systems can demonstrate complex reasoning abilities comparable to human intelligence in educational contexts. This is relevant for teachers as it helps them understand the current capabilities and limitations of AI tools in supporting or assessing higher-order thinking skills in their classrooms.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/higher-order-thinking-skills#article","headline":"Higher-Order Thinking Skills","description":"How can we enhance the quality of thinking in our classrooms, and what strategies can we use to promote higher-order thinking?","datePublished":"2023-02-27T16:06:49.907Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/higher-order-thinking-skills"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69525caa35622d3f9ed776d3_69525ca8199d255cfcbbb2c9_higher-order-thinking-skills-infographic.webp","wordCount":3737},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/higher-order-thinking-skills#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Higher-Order Thinking Skills","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/higher-order-thinking-skills"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/higher-order-thinking-skills#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What exactly are higher-order thinking skills and how do they differ from basic learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) are cognitive abilities that go beyond basic memorisation and comprehension, including analysis, evaluation, synthesis, and creation. These skills enable students to solve complex problems, make connections between ideas, and apply knowledge in new situations, rat"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers effectively develop higher-order thinking skills in their classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers should pre-plan higher-order questions before lessons rather than thinking on their feet, and incorporate activities like debates, problem-based learning, and collaborative discussions. Additional effective strategies include case studies, project-based learning, and activities that require"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why do traditional multiple-choice assessments fail to measure higher-order thinking skills?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Traditional multiple-choice assessments typically focus on memorisation and basic comprehension rather than critical thinking abilities. These assessments miss students' capacity for analysis, evaluation, and application of knowledge in new situations, which are the core components of higher-order t"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What role does collaboration play in developing higher-order thinking skills?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Vygotsky's research demonstrates that higher mental abilities can only develop through interaction with others, making isolated thinking tasks ineffective. Collaborative activities, group discussions, and peer interaction are essential for developing advanced reasoning skills and critical thinking a"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers move beyond Bloom's Taxonomy to promote genuine critical thinking?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Rather than rigidly categorising thinking skills into levels, teachers should adopt a more fluid approach that recognises the interconnected nature of cognitive abilities. This means focusing on activities that require students to justify their ideas, engage in critical reflection, and sustain lines"}}]}]}