Erikson's Eight Stages of Psychosocial Development: A Teacher's Guide

Explore Erikson's eight stages of psychosocial development and learn how each stage influences students' growth and behavior at various ages.

Explore Erikson's eight stages of psychosocial development and learn how each stage influences students' growth and behavior at various ages.

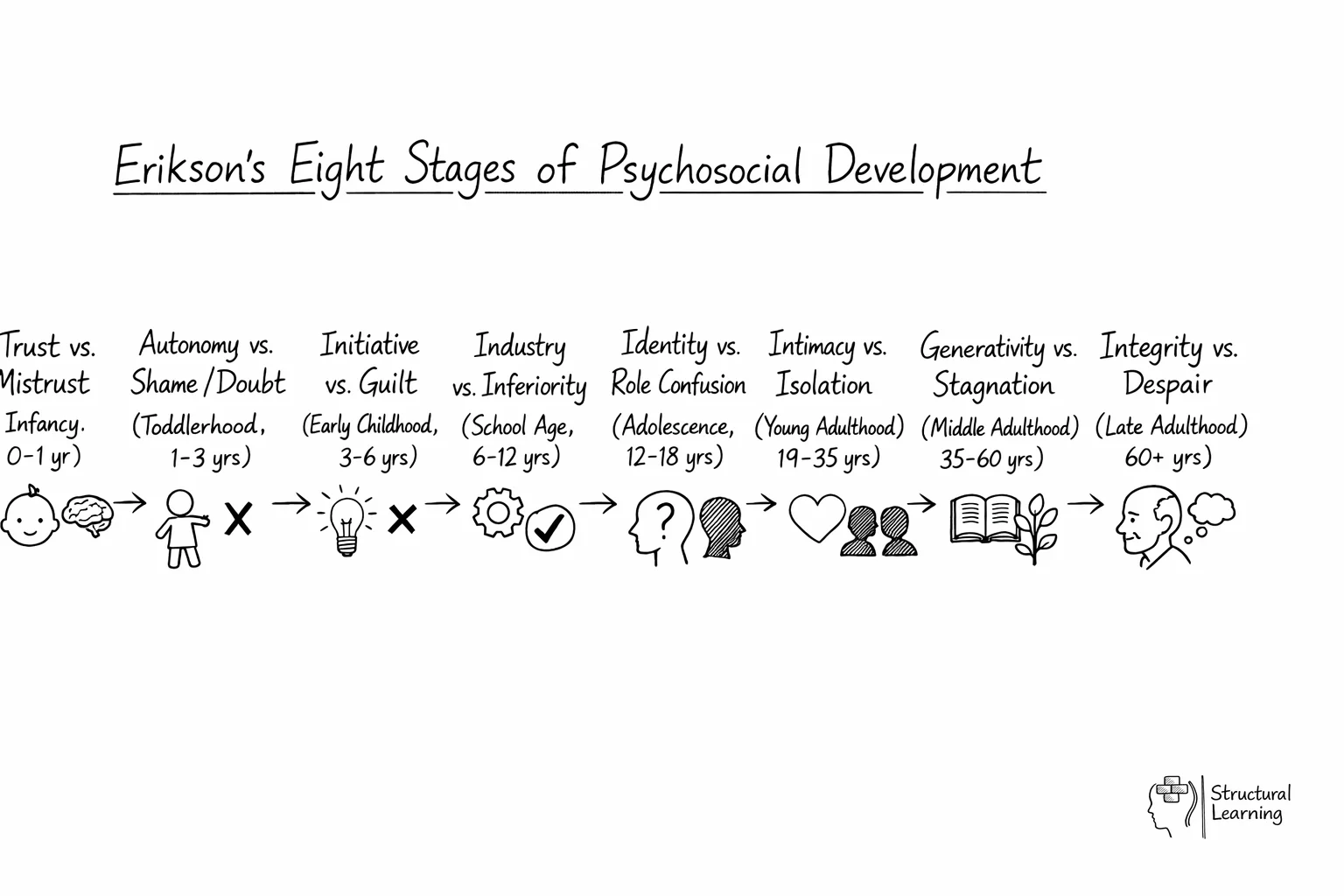

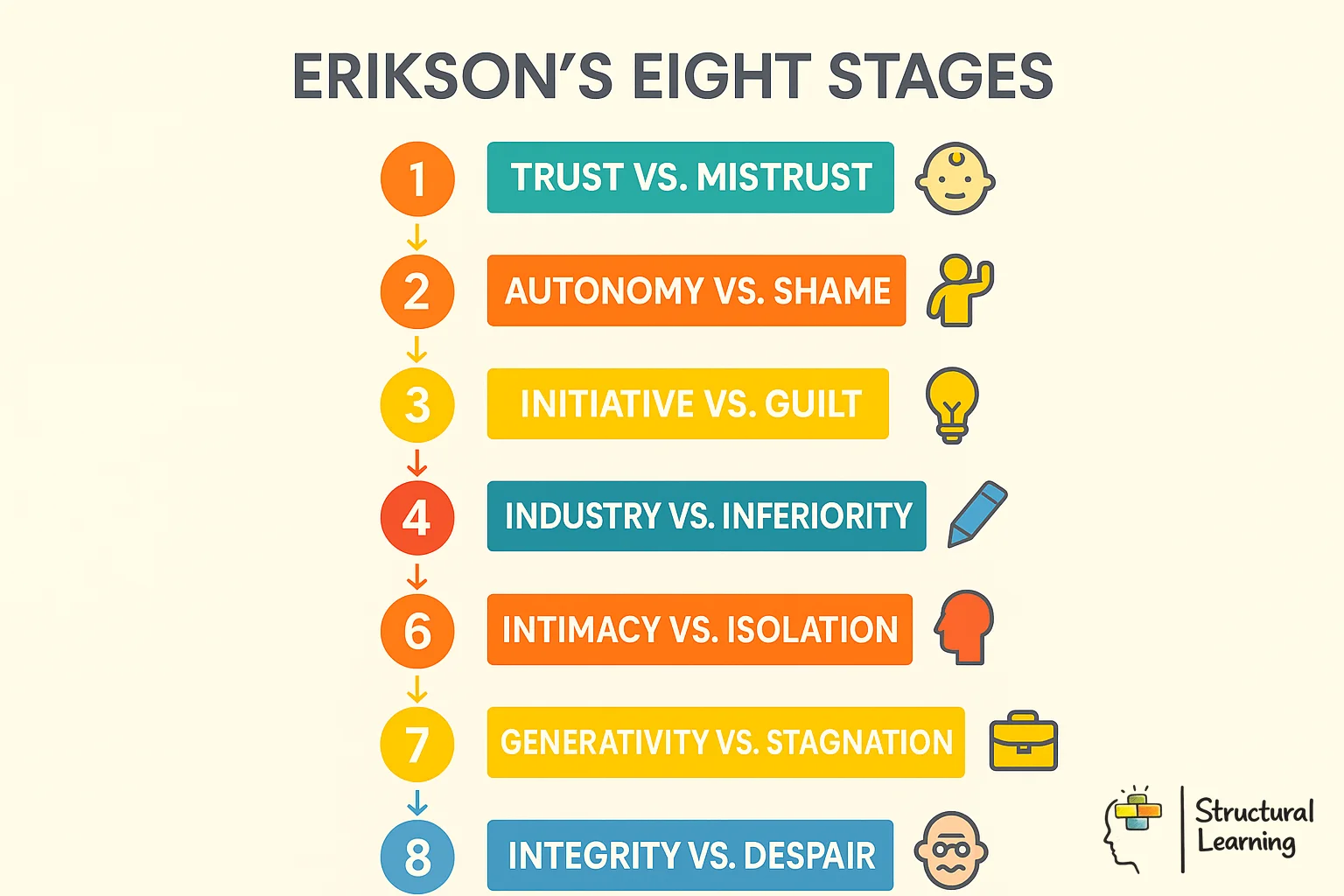

Erik Erikson's theory of psychosocial development provides a valuable framework for understanding student needs at different ages. Unlike Freud's focus on early childhood, Erikson proposed eight stages spanning the entire lifespan, each characterised by a central conflict that shapes personality. For teachers, understanding Erikson's developmental stages helps explain why primary pupils need consistent routines (trust), why adolescents struggle with identity, and how to create environments that support healthy development at each stage.

| Stage/Level | Age Range | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trust vs. Mistrust | Infancy | Development of basic trust through consistent care | Primary pupils need consistent routines and reliable environments |

| Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt | Toddlerhood | Expressing independence while needing support; toilet training experiences | Balance between encouraging independence and providing necessary support |

| Initiative vs. Guilt | Early childhood | Not specified in excerpt | Not specified in excerpt |

| Industry vs. Inferiority | School age | Not specified in excerpt | Confident Year 6 students may struggle when unresolved issues resurface |

| Identity vs. Role Confusion | Adolescence | Identity crisis; experimenting with social roles, groups, and beliefs | Support Year 9s through friendship dramas and academic disengagement |

| Intimacy vs. Isolation | Young adulthood | Relationships remain critical | Not specified in excerpt |

| Generativity vs. Stagnation | Middle adulthood | Not specified in excerpt | Not specified in excerpt |

| Integrity vs. Despair | Late adulthood | Not specified in excerpt | Not specified in excerpt |

These psychosocial stages highlight key conflicts or struggles we all inevitably encounter, from infancy right through late adulthood. Successfully managing these challenges creates healthy personal growth, shaping who we become. For instance, during toddlerhood, experiences around toilet training play a crucial role, with successes and failures potentially influencing the delicate balance between autonomy and feelings of shame and doubt. Teachers can use effective questioning to understand where students are developmentally and emotion coaching to support them through these critical stages.

Erikson's theory is not without its critics. Some argue that the stages are too rigid and do not account for cultural variations. Others suggest that the theory is more descriptive than explanatory. However, its enduring appeal lies in its complete view of development, emphasising the interplay between psychological and social factors.

While Erikson's stages provide a helpful framework, remember that children develop at their own pace. Using this theory effectively in the classroom requires observation, empathy, and flexibility.

Understanding Erikson's theory is only the first step - successful implementation requires targeted strategies for each developmental stage you encounter in your classroom. For primary school teachers working with children navigating the Industry vs. Inferiority stage (ages 6-12), focus on creating opportunities for skill mastery and competence building. Structure lessons with clear, achievable milestones that allow students to experience success whilst developing resilience when facing challenges.

Secondary teachers encounter students grappling with Identity vs. Role Confusion (ages 12-18), requiring a different approach entirely. Provide diverse learning experiences that allow students to explore different interests and perspectives. Encourage self-reflection through journals or discussion groups, and create classroom environments where questioning and identity exploration are welcomed rather than discouraged. Consider implementing project-based learning that allows students to pursue topics aligned with their emerging interests, developing both academic growth and personal identity development.

Regardless of the age group you teach, certain universal principles apply across all stages. Establish consistent routines that provide security whilst allowing flexibility for individual growth. Model the positive resolution of conflicts in your own behaviour, demonstrating how challenges can lead to personal development. Most importantly, recognise that students may be working through multiple stages simultaneously, requiring individualised approaches that meet each learner where they are in their developmental journey. Professional development opportunities focusing on developmental psychology can enhance your ability to recognise and respond appropriately to these varying needs within your classroom.

Each of Erikson's eight stages presents distinct challenges that manifest differently across age groups, requiring teachers to adapt their approaches accordingly. The early stages, particularly Trust vs. Mistrust (infancy) and Autonomy vs. Shame (early childhood), establish foundational patterns that influence how students engage with learning environments. While primary teachers may encounter children working through Initiative vs. Guilt (ages 3-5), where excessive criticism can stifle natural curiosity, secondary educators primarily observe Industry vs. Inferiority (ages 6-12) and Identity vs. Role Confusion (adolescence).

In primary classrooms, Industry vs. Inferiority manifests as students' intense focus on competence and achievement. Children at this stage desperately want to master skills and contribute meaningfully, making differentiated instruction crucial to prevent feelings of inadequacy. Meanwhile, secondary teachers navigate Identity vs. Role Confusion, where adolescents experiment with different personas and challenge authority as part of healthy development. Understanding this helps teachers distinguish between typical identity exploration and concerning behavioural issues.

The remaining stages, though occurring beyond school years, influence adult interactions within educational settings. Teachers experiencing Generativity vs. Stagnation (middle adulthood) often demonstrate heightened commitment to nurturing student growth, whilst those in Integrity vs. Despair may bring valuable wisdom about long-term educational impacts. Recognising these developmental patterns enables more empathetic, developmentally appropriate teaching strategies that support both immediate learning objectives and long-term psychosocial development.

Effective teaching requires matching instructional strategies to students' developmental stages, as each of Erikson's phases presents unique classroom challenges and opportunities. During the industry versus inferiority stage (ages 6-12), teachers should emphasise skill mastery through scaffolded learning experiences, breaking complex tasks into manageable components. Celebration of effort over outcome becomes crucial here, as students are forming their sense of academic competence. Bandura's self-efficacy research supports providing multiple pathways to success, ensuring all learners can experience the satisfaction of meaningful achievement.

For secondary students navigating identity versus role confusion (ages 12-18), classroom strategies must accommodate their need for exploration whilst maintaining clear boundaries. Offering choices in learning activities, encouraging critical thinking about diverse perspectives, and creating opportunities for self-reflection help students develop their emerging sense of self. Consistent, fair classroom management provides the security adolescents need whilst exploring their independence.

Practical implementation involves adapting assessment strategies to developmental needs: younger students benefit from frequent, formative feedback that builds confidence, whilst older students require opportunities to demonstrate learning through varied formats that align with their developing identities. Regular observation of student behaviour patterns helps teachers identify when developmental conflicts are impacting learning, enabling timely intervention and support.

Recognising developmental conflicts in students requires careful observation of behaviour patterns rather than isolated incidents. Students struggling with industry versus inferiority may consistently avoid challenging tasks, express frequent self-doubt about their abilities, or become withdrawn during group activities. Adolescents grappling with identity versus role confusion often display seemingly contradictory behaviours, experimenting with different personas or becoming overly concerned with peer approval. As Marcia's identity status research demonstrates, this exploration is developmentally appropriate but can manifest as academic inconsistency or social anxiety.

Key indicators include sudden changes in academic performance, social withdrawal or aggressive behaviour, and verbal expressions of inadequacy or confusion about future goals. Students may also exhibit regression behaviours, returning to earlier developmental patterns when facing unresolved conflicts. For instance, a typically independent Year 6 student might suddenly require excessive teacher reassurance, suggesting unresolved trust or autonomy issues impacting their sense of industry.

Effective classroom responses involve creating supportive environments that address specific developmental needs. Provide multiple opportunities for success through differentiated tasks, establish consistent routines that build trust, and encourage healthy identity exploration through diverse role models and career discussions. Document concerning patterns and collaborate with pastoral care teams when behaviours persist, ensuring students receive appropriate developmental support during these critical psychosocial transitions.

When students encounter developmental crises, teachers often observe changes in behaviour, academic performance, or peer relationships that signal underlying psychosocial conflicts. Early recognition is crucial, as Erikson's framework suggests these periods represent critical opportunities for growth rather than simply transformative phases. Teachers who understand that a struggling Year 7 student may be grappling with identity versus role confusion, or that a primary pupil's sudden withdrawal might reflect trust versus mistrust conflicts, can respond with appropriate developmental sensitivity rather than purely disciplinary measures.

Effective support strategies must align with the specific developmental stage whilst maintaining classroom structure and learning objectives. For younger pupils experiencing autonomy versus shame conflicts, providing controlled choices within clear boundaries helps build confidence without compromising classroom management. Scaffolded independence opportunities, such as selecting from predetermined activities or choosing presentation formats, allow students to exercise developing autonomy safely. Meanwhile, adolescents facing identity crises benefit from diverse role models, opportunities for self-expression through curriculum content, and patient guidance as they explore different aspects of their emerging identities.

Professional collaboration becomes essential when developmental crises significantly impact learning or wellbeing. Teachers should document behavioural patterns, communicate observations clearly with pastoral teams, and adjust classroom approaches accordingly. Consistent, predictable responses across the school community help students navigate developmental challenges whilst maintaining academic progress and positive peer relationships.

Erikson's theory reminds us that development is a continuous process, shaped by both individual experiences and social interactions. By understanding the key challenges and opportunities associated with each stage, teachers can create more supportive and effective learning environments.

Ultimately, the goal is to help students navigate these stages successfully, developing resilience, self-awareness, and a sense of purpose. By embracing a lifespan perspective on learning, educators can helps students to reach their full potential, both academically and personally.

Understanding developmental stages transforms how we approach classroom management and student support. When a Year 7 student struggles with peer relationships, we can recognise this as part of their identity formation rather than simply transformative behaviour. Similarly, when older students question authority or challenge established ideas, we can frame this as healthy exploration of their emerging autonomy. These insights help us respond with patience and targeted strategies that support growth rather than suppress natural developmental processes.

Practical applications of Erikson's theory extend into curriculum design and assessment practices. For younger pupils developing industry versus inferiority, we might emphasise skill-building activities that provide clear markers of progress and celebrate incremental achievements. For adolescents navigating identity formation, we can incorporate opportunities for self-expression, choice in learning pathways, and reflection on personal values. Even our feedback becomes more meaningful when it acknowledges both academic progress and psychosocial development.

The beauty of adopting a lifespan perspective lies in recognising that every interaction matters. Whether supporting a Foundation Stage child's developing trust or helping a Year 11 student prepare for adult responsibilities, we contribute to their ongoing psychological development. This understanding improves teaching from mere content delivery to genuine mentorship, creating classrooms where students feel truly seen, supported, and helped to become their best selves.