Bowlby's Attachment Theory: How Early Bonds Shape Classroom Behaviour

Understand Bowlby's attachment theory and its four stages. Learn how attachment styles affect pupil behaviour, relationships and learning, with practical strategies for teachers.

Understand Bowlby's attachment theory and its four stages. Learn how attachment styles affect pupil behaviour, relationships and learning, with practical strategies for teachers.

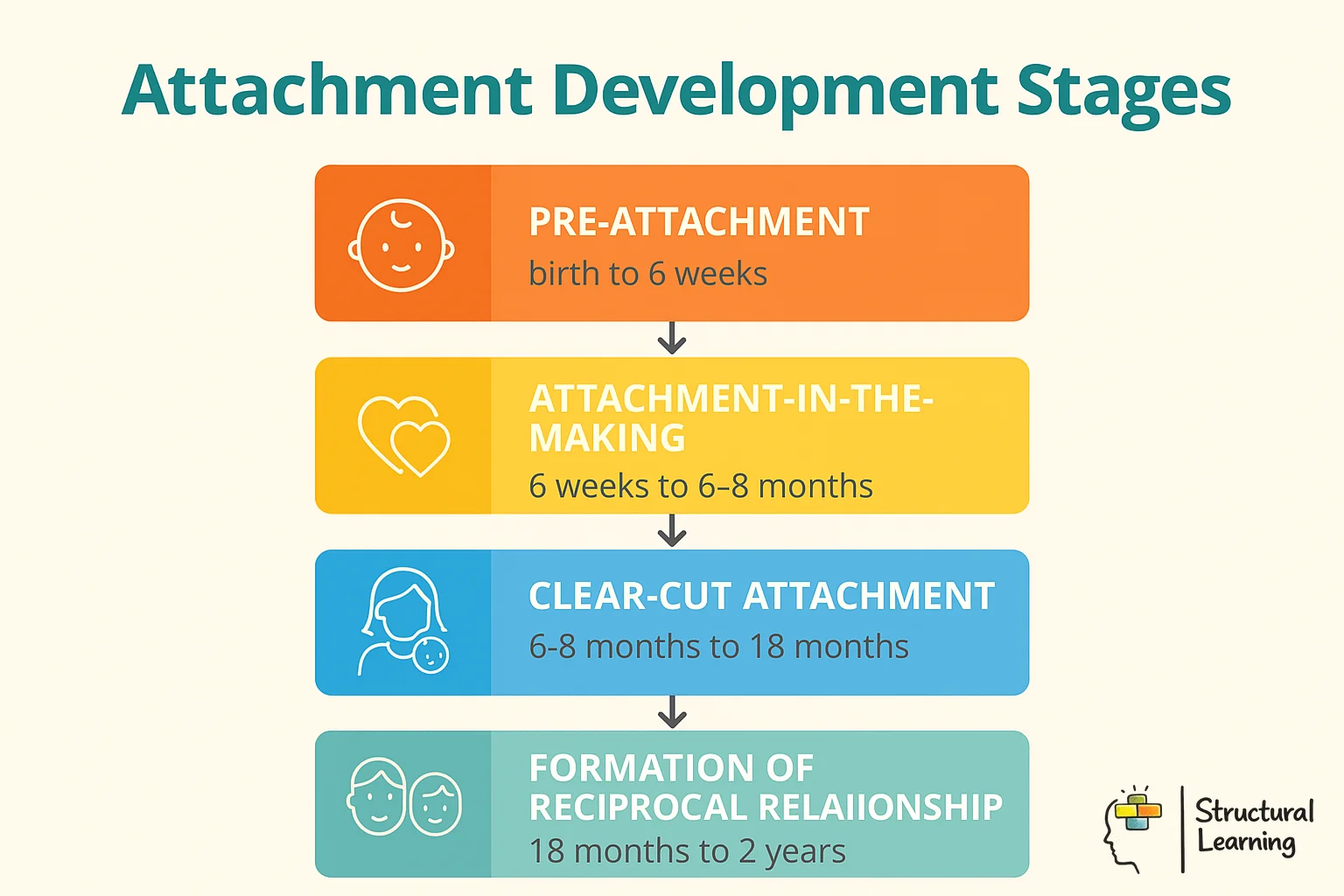

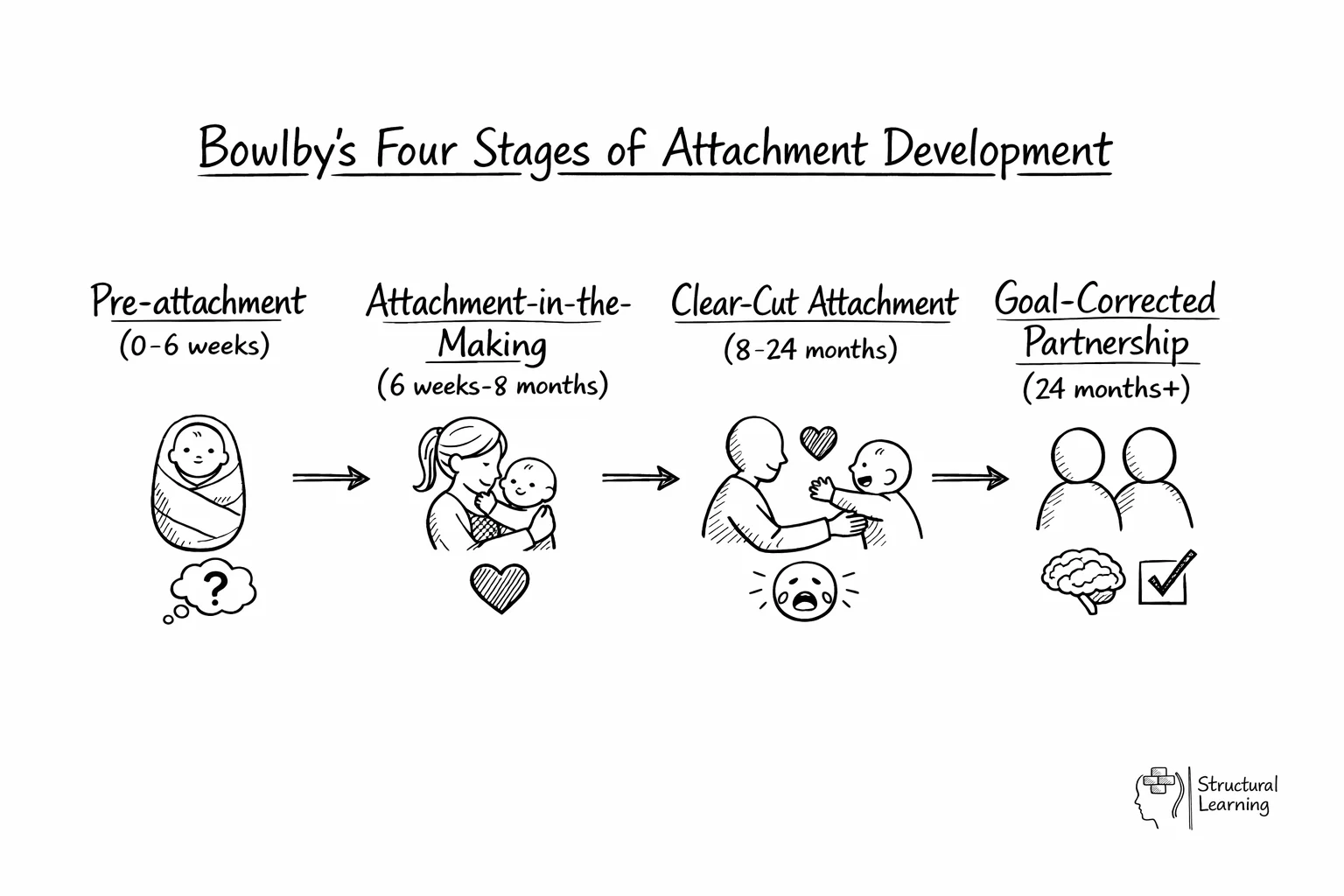

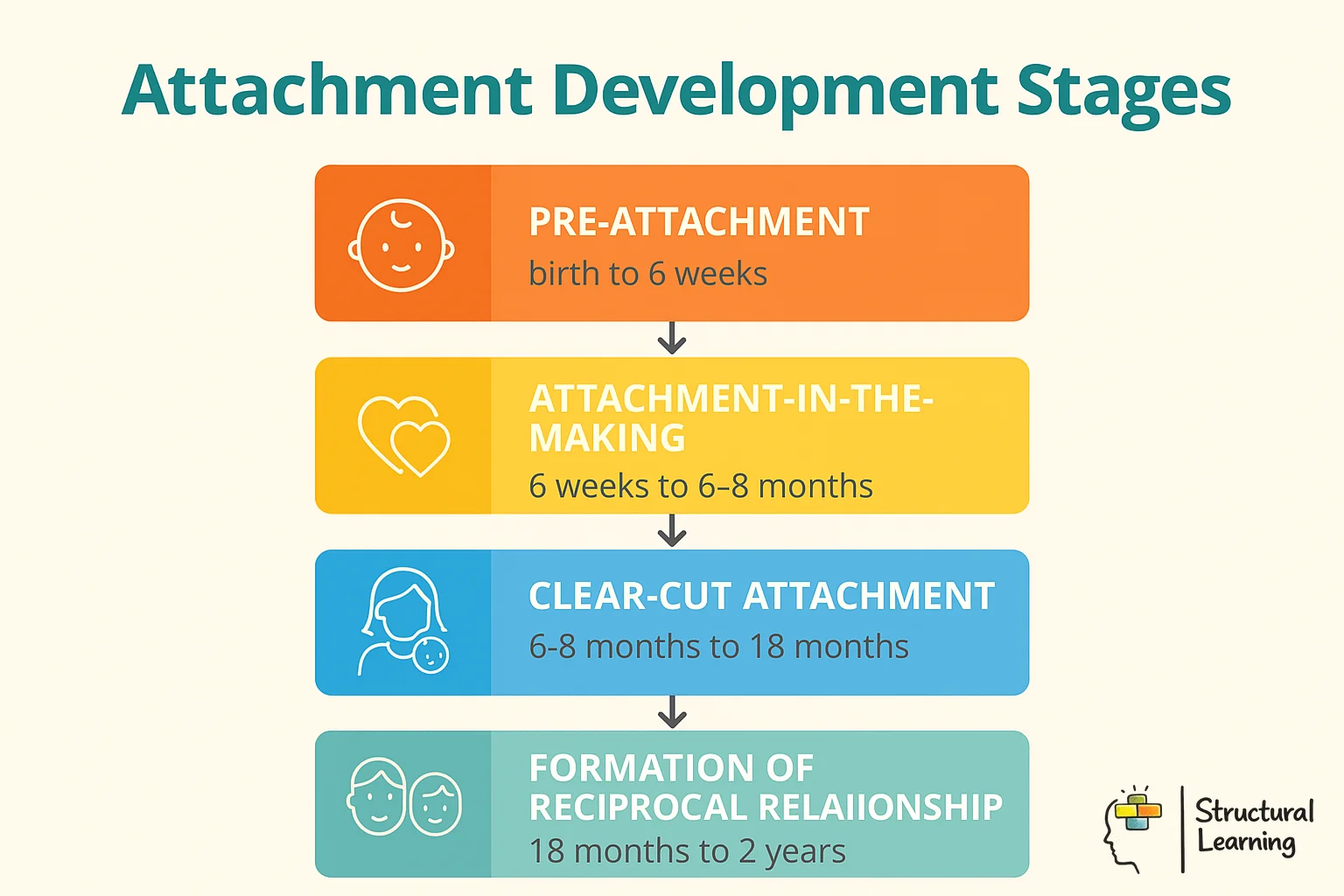

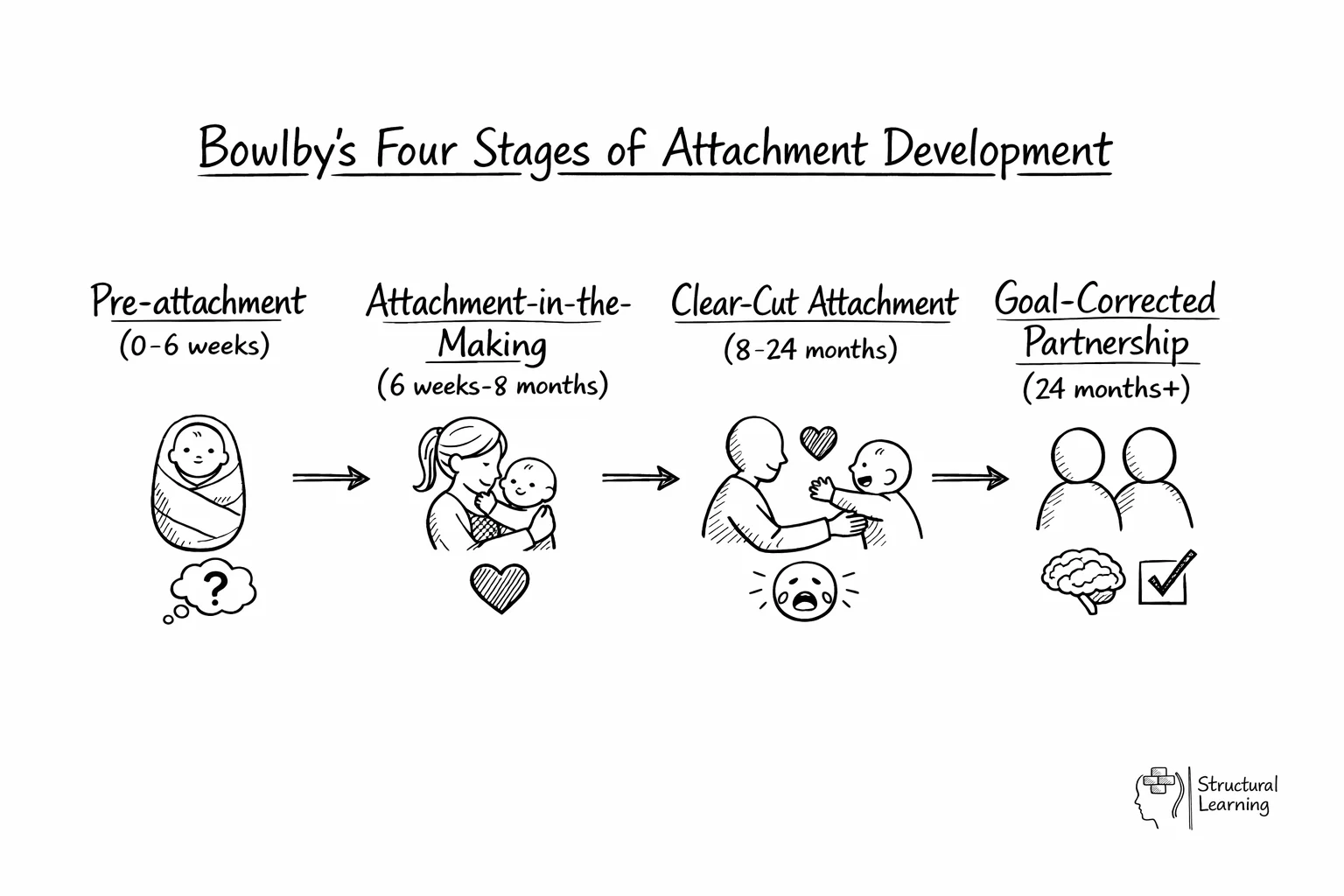

Bowlby's Attachment Theory explains how emotional bonds between infants and caregivers shape psychological development throughout life, demonstrating the important connection between attachment and development. The theory proposes that children are biologically programmed to form attachments as a survival mechanism, with these early bonds influencing future relationships and emotional health. John Bowlby identified four developmental stages: Pre-attachment (0-6 weeks), Attachment-in-the-making (6 weeks-8 months), Clear-cut attachment (8-24 months), and Goal-corrected partnership (24 months onwards).

Bowlby's Attachment Theory describes how the emotional bonds formed between infants and their primary caregivers shape psychological development throughout life. British psychiatrist John Bowlby (1907-1990) developed this groundbreaking framework, which proposes that children are genetically predisposed to form attachments as a survival mechanism. His work has transformed our understanding of child development, influencing everything from parenting approaches to therapeutic interventions. In 2025, Bowlby's insights remain central to how educators and psychologists support children's development, working alongside social learning theories to understand how children grow and learn.

Comparing attachment theories? This article focuses on Bowlby's original theory. For a comparison of multiple attachment theories including Ainsworth's Strange Situation and modern perspectives, see our broader guide to theories of attachment.

Bowlby's theory is rooted in the belief that infants are biologically wired to form attachments, a survival mechanism that ensures protection and care during vulnerability. These early attachments, formed during the initial years of life, are not just transient bonds but play a important role in shaping the child's future wellbeing and relationships. This understanding mirrors how educators approach building knowledge progressively throughout a child's learning process.

Bowlby's Attachment Theory underscores the significance of a secure and consistent attachment to the primary caregiver. Bowlby postulated that disruptions or inconsistencies in these early attachments could potentially lead to a spectrum of mental health and social-emotional learning difficulties in later life.

This perspective marked a significant shift from the dominant theories of his era, which often attributed mental health issues to innate or genetic factors. Instead, Bowlby's theory emphasised the impact of early childhood experiences and their enduring influence on an individual's life trajectory, drawing from psychodynamic perspectives.

Bowlby's theory also introduced the concept of individual differences in attachment patterns. His colleague Mary Ainsworth later expanded on this in her important work on attachment styles. Ainsworth's research further validated Bowlby's theory and provided a framework for understanding the different attachment styles that emerge from the quality of early interactions with caregivers.

John Bowlby's Attachment Theory, developed by British psychiatrist John Bowlby (1907-1990), explains how emotional bonds between infants and caregivers shape psychological development throughout life. Bowlby proposed that children have an innate tendency to form attachments as a survival mechanism, with these early bonds influencing future relationships and emotional health.

Bowlby trained as a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, but his groundbreaking work challenged many existing psychoanalytic assumptions. His clinical observations of children separated from their parents, particularly during World War II, led him to develop his revolutionary theory. Unlike previous theorists who focused on feeding as the primary driver of attachment, Bowlby recognised that emotional connection and responsiveness were the true foundations of secure bonds.

John Bowlby's theory proposes that children are biologically predestined to form emotional attachments with caregivers as a survival mechanism. His attachment theory identifies four developmental stages and explains how these early bonds create internal working models that influence all future relationships and emotional development throughout life.

The theory suggests that attachment behaviours are adaptive strategies that evolved over time. These behaviours, such as crying, smiling, and following, help maintain closeness to caregivers who provide protection and care. These behaviours activate caregiving responses in adults, creating a reciprocal system that ensures infant survival. This biological basis for attachment distinguishes Bowlby's work from earlier psychoanalytic theories.

Attachment theory by John Bowlby explains that infants are biologically wired to form emotional bonds with primary caregivers for survival. This groundbreaking theory describes how these early attachments shape psychological development and influence future relationships throughout an individual's life.

Central to Bowlby's theory is the concept of the "internal working model", a mental representation of oneself, others, and relationships formed through early attachment experiences. Children who experience responsive, consistent caregiving develop positive internal working models, viewing themselves as worthy of love and others as trustworthy. These models become templates for navigating relationships throughout life.

The four stages are: Pre-attachment (0-6 weeks) where infants show no specific attachment; Attachment-in-the-making (6 weeks-8 months) where babies begin recognising familiar caregivers; Clear-cut attachment (8-24 months) where separation anxiety emerges; and Goal-corrected partnership (24 months onwards) where children understand caregiver needs. Each stage builds on the previous one, creating increasingly complex attachment behaviours and emotional bonds.

Bowlby proposed that attachment develops through four distinct stages during early years development. Understanding these stages helps educators and parents recognise normal developmental patterns and identify when children might need additional support. Each stage builds upon the previous one, creating increasingly sophisticated emotional bonds that impact engagement and learning throughout development.

Let's explore each of Bowlby's stages, understanding the emotional milestones and their implications for educators working with young children.

During this initial phase, infants display indiscriminate social responsiveness. They don't show a preference for a primary caregiver and accept comfort from anyone. Newborns use innate behaviours like crying, grasping, and looking to signal their needs and attract adult attention. However, they lack the cognitive ability to distinguish between caregivers.

Teachers working with very young children should understand this lack of specific attachment and focus on providing consistent, responsive care to all infants. Multiple caregivers can meet the infant's needs during this stage without causing distress. The key is ensuring that all interactions are sensitive and responsive, laying the groundwork for later attachment formation.

Infants begin to show preferences for familiar caregivers during this stage. They smile more at those caregivers and are easily calmed by them, though they still accept care from others. This period marks the beginning of genuine attachment as infants develop expectations about caregiver behaviour based on repeated interactions.

This is a important time for educators to build strong bonds with the children in their care by being attentive, responsive, and engaging in positive interactions. Consistent routines help infants develop trust and security. Early years practitioners should aim to provide predictable, warm responses to infant cues, helping children feel safe and understood.

This stage is marked by separation anxiety when the primary caregiver leaves. Infants actively seek closeness and proximity to their preferred caregiver and may show wariness or distress around strangers. The attachment bond is now clearly established, and children use their caregiver as a "secure base" from which to explore the environment.

Teachers can support children experiencing separation anxiety by providing a safe and predictable environment, offering comfort, and encouraging gradual acclimatisation to the classroom. Understanding that separation anxiety is a normal and healthy sign of attachment helps educators respond with patience and empathy rather than frustration.

Children develop a more sophisticated understanding of their caregiver's needs and goals. They can tolerate brief separations and understand that the caregiver will return. Language development enables children to negotiate with caregivers and plan for separations, making transitions less distressing.

Educators can develop this understanding by explaining routines, providing clear expectations, and helping children develop strategies for coping with separation. At this stage, children benefit from discussions about feelings and reassurance about reunion, helping them build confidence in the reliability of important relationships.

Attachment styles are individual patterns of relating to others that develop as a result of early interactions with primary caregivers. These styles influence how people approach relationships, manage emotions, and cope with stress. Mary Ainsworth's "Strange Situation" experiment identified three primary attachment styles: secure, anxious-avoidant (also called anxious-resistant), and anxious-ambivalent. A fourth style, disorganised attachment, was later identified by Main and Solomon.

Understanding these attachment styles is important for educators because they directly impact how children behave in classroom settings, form relationships with teachers and peers, and respond to academic challenges. Each style reflects different adaptations to caregiving experiences and requires tailored support strategies.

Children with secure attachment have caregivers who are consistently responsive and sensitive to their needs. These children feel safe and secure, and they trust that their caregivers will be there for them. They use their caregiver as a secure base for exploration, showing distress when separated but greeting the caregiver warmly upon reunion and quickly returning to play.

In the classroom, securely attached children are typically confident, curious, and able to form positive relationships with teachers and peers. They regulate emotions effectively, seek help when needed, and demonstrate resilience when facing challenges. These children often show higher academic achievement and better social skills compared to children with insecure attachment styles.

Children with anxious-avoidant attachment have caregivers who are emotionally unavailable or consistently rejecting of the child's bids for comfort. These children learn to suppress their emotions and avoid seeking comfort from others as a protective strategy. During separations, they show little distress and actively avoid or ignore the caregiver upon reunion.

In the classroom, these children may appear independent and self-reliant, but they may also struggle to form close relationships with teachers and peers. They often minimise emotional expression and may reject offers of help or support. Teachers might misinterpret their behaviour as maturity or self-sufficiency when actually these children need support in learning to trust and connect with others.

Children with anxious-ambivalent (or anxious-resistant) attachment have caregivers who are inconsistent in their responses, sometimes being responsive and other times being neglectful or intrusive. These children are often anxious and clingy, unable to predict whether their needs will be met. They show intense distress during separations and difficulty being comforted upon reunion, often displaying anger alongside proximity-seeking.

In the classroom, they may seek constant reassurance from teachers and struggle to regulate their emotions. These children often have difficulty concentrating on learning tasks because they're preoccupied with monitoring the teacher's availability and attention. They may exhibit controlling or demanding behaviours as attempts to ensure adult responsiveness.

Children with disorganised attachment have caregivers who are frightening, frightened, or severely inconsistent, often due to trauma, mental illness, or substance abuse. These children display contradictory behaviours, such as seeking comfort from a caregiver while simultaneously avoiding eye contact or showing frozen, dazed expressions. This attachment style represents a breakdown in attachment strategies when the caregiver is both the source of fear and the solution to fear.

In the classroom, they may exhibit behavioural problems, difficulty regulating emotions, and challenges in forming trusting relationships. These children often require specialised support through trauma- informed practise and may benefit from consistent, predictable routines and patient, non-threatening adult interactions.

| Attachment Style | Caregiver Behaviour | Child Response | Classroom Behaviour |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | Consistently responsive and sensitive | Uses caregiver as secure base; distressed at separation but easily comforted | Confident, curious, forms positive relationships, emotionally regulated |

| Anxious-Avoidant | Emotionally unavailable, rejecting | Minimal distress at separation; avoids caregiver at reunion | Appears independent, struggles with close relationships, suppresses emotions |

| Anxious-Ambivalent | Inconsistent, unpredictable | Extreme distress at separation; difficult to comfort, shows anger | Clingy, seeks constant reassurance, poor emotional regulation |

| Disorganised | Frightening, frightened, severely inconsistent | Contradictory behaviours, frozen/dazed responses | Behavioural problems, difficulty trusting, challenges with emotion regulation |

Mary Ainsworth, a developmental psychologist who worked with Bowlby, developed the Strange Situation procedure in the 1970s to empirically measure attachment quality in children aged 12-18 months. This laboratory-based assessment became the gold standard for attachment research and provided important evidence supporting Bowlby's theoretical framework.

The Strange Situation is a structured observation lasting approximately 20 minutes, consisting of eight episodes that progressively increase stress for the infant. The procedure takes place in a comfortable room with toys, and researchers observe the infant's responses to separations and reunions with the caregiver and encounters with a friendly stranger.

The procedure follows a specific sequence designed to activate the attachment system through the stress of separation:

Researchers focus particularly on the reunion episodes, as these most clearly reveal the child's attachment style. Secure children seek proximity and comfort, quickly settling and returning to play. Avoidant children actively avoid or ignore the caregiver. Ambivalent children display anger and resistance alongside proximity-seeking, remaining distressed even after reunion. Disorganised children show contradictory or confused behaviours, reflecting their inability to develop a consistent attachment strategy.

While educators don't conduct formal Strange Situation assessments, understanding this research helps them recognise attachment patterns in everyday classroom situations. Drop-off time, for instance, often mirrors the Strange Situation's separation episodes, revealing how children cope with caregiver absence and whether they use teachers as alternative secure bases.

Ainsworth's work demonstrated that attachment is measurable, observable, and directly linked to caregiver sensitivity, the ability to perceive and interpret infant signals accurately and respond promptly and appropriately. This finding reinforces the importance of teacher responsiveness in educational settings.

The principles of attachment theory extend far beyond infancy, profoundly influencing children's experiences throughout their educational process. Classrooms function as secondary attachment environments where teachers can serve as alternative secure bases, particularly for children who may lack secure attachments at home.

Research consistently demonstrates that positive teacher-student relationships predict academic achievement, school engagement, and social-emotional development. Children who feel securely attached to their teachers show greater academic motivation, better behaviour regulation, and more positive peer relationships. This is especially true for vulnerable children who may be experiencing adversity at home.

Just as infants use caregivers as a secure base for exploration, students use teachers as secure bases for academic and social exploration. A secure classroom base has several key features:

When teachers provide this secure base, children feel confident to take academic risks, ask questions, make mistakes, and engage deeply with learning challenges. They develop what researchers call "academic resilience", the ability to persevere through difficulties because they trust support is available when needed.

Attachment security directly influences learning engagement through several mechanisms. Secure children allocate cognitive resources to learning rather than monitoring adult availability or managing anxiety. They're more likely to seek help appropriately when stuck, rather than giving up (anxious-ambivalent pattern) or refusing assistance (avoidant pattern).

Children with insecure attachment often display learning difficulties that stem not from cognitive limitations but from emotional preoccupations. An anxious-ambivalent child's constant reassurance-seeking interrupts sustained attention to tasks. An avoidant child's reluctance to seek help means they miss opportunities for scaffolding. Understanding these patterns helps teachers recognise when learning difficulties have a ttachment-related roots.

Teachers can intentionally structure classroom environments to support healthy attachment patterns:

The quality of teacher-student relationships serves as a powerful protective factor, particularly for children facing adversity. Research shows that even one secure relationship with a non-parental adult can significantly improve outcomes for at-risk children. Teachers are uniquely positioned to provide this relationship.

Developing secure teacher-student relationships requires intentional effort and specific relational skills. Building relationships starts with teachers reflecting on their own attachment histories and recognising how these influence their interactions with students.

Key relationship-building strategies include:

Some children are more susceptible to relationship quality than others, a phenomenon called "differential susceptibility." Children with difficult temperaments or insecure attachment histories may show the poorest outcomes in unsupportive environments but the best outcomes in highly supportive environments. This means teacher relationship quality matters most for the most vulnerable children.

This research has profound implications: the children who appear most difficult to connect with often benefit most from relationship investment. Teachers who persist in building relationships with resistant or challenging students can achieve significant results.

Attachment theory was developed primarily through research with Western, middle-class families, but attachment needs are universal across cultures. However, the specific behaviours that communicate security vary culturally. Teachers must understand that:

Culturally responsive practise requires teachers to learn about students' cultural backgrounds and adapt relationship-building approaches accordingly, while maintaining the core principles of availability, sensitivity, and responsiveness.

Children with insecure or disorganised attachment require thoughtful, informed support to develop security in educational settings. Understanding attachment patterns allows teachers to interpret challenging behaviours as adaptations rather than defiance, fundamentally shifting the teacher's emotional response and intervention approach.

Teachers may notice various signs suggesting attachment difficulties:

Remember that attachment difficulties exist on a continuum, and many children show mild attachment-related challenges without meeting criteria for attachment disorders. All children benefit from attachment-informed teaching practices.

Children with avoidant patterns have learned that emotional needs go unmet, so they suppress them. Support strategies include:

Children with ambivalent patterns struggle with uncertainty about adult availability. Support strategies include:

Children with disorganised attachment require the most intensive and specialised support, often benefiting from collaboration with mental health professionals. Classroom strategies include:

The most effective support occurs when entire schools adopt attachment-informed practices rather than individual teachers working in isolation. This includes:

Understanding Bowlby's Attachment Theory and the different attachment styles can help educators create a supportive and nurturing learning environment for all children. By being responsive, consistent, and empathetic, teachers can develop secure attachments and promote healthy social-emotional development.

The application of attachment principles in educational settings doesn't require formal assessment or diagnosis. Instead, it involves creating classroom cultures characterised by safety, predictability, and responsive relationships, conditions that benefit all children regardless of attachment history.

Here are research-backed strategies for creating attachment-informed classrooms:

Teachers' own attachment histories influence how they relate to students. Those with secure attachment histories may naturally provide responsive, attuned care. However, teachers with insecure attachment may struggle with specific student behaviours that trigger their own attachment patterns.

For example, a teacher with avoidant attachment might feel uncomfortable with a clingy, anxious-ambivalent child's constant bids for attention. A teacher with anxious attachment might over-identify with an avoidant child's emotional distance. Becoming aware of these patterns through reflection and supervision helps teachers respond to students' needs rather than their own triggered reactions.

While teacher relationships are powerful, recognise their limits. Teachers are not therapists or substitute parents. Children with significant attachment trauma often require specialised therapeutic intervention beyond what classroom relationships can provide.

Teachers should know when to seek support from school counsellors, educational psychologists, or external mental health services. Red flags requiring referral include severe aggression, extreme withdrawal, self-harm, or behaviours suggesting abuse or neglect. Collaborative working with families and specialists ensures children receive thorough support.

Bowlby's maternal deprivation hypothesis proposes that continuous emotional care from a mother or mother substitute is essential for normal psychological development. He argued that prolonged separation from the primary caregiver during the critical period (first 2.5 years) could lead to serious and irreversible developmental consequences. This hypothesis emerged from his observations of children separated from their mothers during World War II evacuations and his work with young offenders.

The hypothesis identifies several potential effects of maternal deprivation, including intellectual development delays, increased aggression, delinquency, and affectionless psychopathy. Bowlby's research with 44 juvenile thieves found that those who experienced early separations were more likely to show emotional detachment and struggle with forming relationships. While later research has refined these ideas, recognising that multiple caregivers can provide adequate emotional support, the core principle remains influential.

For teachers, understanding maternal deprivation helps explain certain behavioural patterns in the classroom. Children who have experienced early separations or inconsistent caregiving may display attention-seeking behaviours, struggle with emotional regulation, or find it difficult to trust adults. Teachers can support these pupils by providing consistent routines and clear expectations, which help create the predictability these children often missed in early development.

Practical strategies include establishing a key person system where vulnerable children have a designated adult they can build trust with, similar to nursery settings. Creating visual timetables and maintaining classroom rituals provides the structure these children need. When children display challenging behaviour, responding with patience rather than punishment acknowledges that their actions may stem from early attachment disruptions rather than deliberate defiance.

Internal working models are mental representations that children develop based on their early attachment experiences. These cognitive frameworks shape how children view themselves, their relationships with others, and the world around them. Bowlby proposed that these models become templates for all future relationships, influencing behaviour and emotional responses throughout life.

When children experience consistent, responsive caregiving, they develop positive internal working models. They come to see themselves as worthy of love and others as trustworthy and reliable. Conversely, inconsistent or neglectful care leads to negative models where children may view themselves as unlovable or others as unpredictable. These models operate largely outside conscious awareness, guiding expectations and interpretations of social interactions.

In the classroom, understanding internal working models helps teachers recognise why certain pupils struggle with trust or seek excessive reassurance. A child with insecure attachment might interpret a teacher's busy moment as rejection, whilst a securely attached child understands the teacher will return their attention when possible. Teachers can support positive model development by providing predictable routines, clear expectations, and consistent emotional availability.

Practical strategies include creating visual timetables that reduce anxiety about transitions, establishing regular one-to-one check-ins with vulnerable pupils, and using consistent language when giving feedback. For instance, rather than saying 'you're being difficult', try 'I can see you're finding this challenging; let's work through it together'. This approach helps reshape negative internal models by demonstrating that adults can be supportive even during struggles.

Research by Main and Goldwyn (1984) showed that internal working models can change through positive relationships, offering hope for children with difficult early experiences. Teachers play a crucial role in this process, potentially serving as corrective attachment figures who challenge negative assumptions about relationships.

Bowlby's Attachment Theory provides a valuable framework for understanding the importance of early relationships in shaping psychological development. By understanding attachment stages and styles, we can create better learning environments. These environments develop secure attachments and promote healthy social-emotional development for all children.

The theory reminds us that children's capacity to learn is fundamentally connected to their sense of safety and security in relationships. Academic achievement doesn't occur in isolation from emotional development, they're intimately intertwined. Children learn best when they feel secure enough to take intellectual risks, knowing that supportive adults will be there to guide them through challenges.

For educators working with children who have experienced attachment disruptions, understanding this framework transforms challenging behaviours from frustrating obstacles into meaningful communications about unmet needs. An anxious-ambivalent child's clinginess becomes understandable as a strategy developed to manage unpredictable caregiving. An avoidant child's rejection of help makes sense as protection against further disappointment.

The early years are formative, and a nurturing educational environment can mitigate the effects of insecure attachment patterns and build resilience. While teachers cannot replace primary caregivers, they can serve as important secondary attachment figures, particularly for vulnerable children. Research consistently shows that even one secure relationship with a caring adult can significantly improve outcomes for children experiencing adversity.

Ultimately, educators who understand and apply the principles of Attachment Theory can make a profound difference in the lives of their students. By developing secure relationships and providing a supportive learning environment, we help children to thrive academically, socially, and emotionally. Creating this secure base allows children to explore the world with confidence and build positive relationships throughout their lives.

As we progress in education, integrating attachment principles with research-informed pedagogical approaches offers a thorough framework for supporting every child's development. This integration recognises that effective teaching addresses the whole child, their emotional needs, relational capacities, and cognitive development- rather than focusing narrowly on academic skills alone.

Teachers should look for signs such as excessive clinginess or withdrawal, difficulty regulating emotions, aggression when separated from caregivers, or struggles with peer relationships. Children with attachment difficulties may also show hypervigilance, difficulty concentrating, or regression in previously mastered skills. Observing these behaviours consistently over time, rather than isolated incidents, can help identify pupils who may benefit from additional support.

Create predictable routines and clear expectations to provide security, and establish yourself as a consistent, reliable adult presence. Use warm but professional interactions, validate emotions, and provide safe spaces for emotional regulation. Implement visual schedules, offer choices when possible, and avoid sudden changes that might trigger anxiety in vulnerable pupils.

Whilst attachment patterns are established early, they continue to influence teenagers' relationships with teachers and peers. Secondary teachers can support students by maintaining consistent boundaries, showing genuine interest in their wellbeing, and understanding that challenging behaviours may stem from earlier attachment difficulties. Building trust through reliable, respectful interactions remains crucial for academic and social success.

Teachers cannot replace primary caregivers but can provide corrective emotional experiences through consistent, supportive relationships. By offering security, predictability, and emotional attunement within the school environment, teachers can help children develop more positive internal working models. However, severe attachment trauma typically requires specialist intervention alongside educational support.

Approach conversations with sensitivity and focus on observable behaviours rather than making judgements about parenting. Share specific examples of classroom behaviours and frame discussions around supporting the child's success at school. Collaborate with parents to understand the child's needs and work together on consistent strategies, whilst following safeguarding procedures if necessary.

Attachment theory in education

Secure relationships in school

Bowlby and Ainsworth identified four attachment patterns that influence how children behave in school. For each classroom behaviour, identify the most likely underlying attachment pattern: Secure, Anxious-Ambivalent, Avoidant or Disorganised.

These peer-reviewed studies examine how Bowlby's attachment theory applies to educational settings, from early years through to secondary school teacher-pupil relationships.

A Secure Base from Which to Regulate: Attachment Security in Toddlerhood as a Predictor of Executive Functioning at School Entry View study ↗

130 citations

Bernier & Beauchamp (2015)

This longitudinal study tracked children from toddlerhood to school entry, finding that securely attached children developed stronger executive functioning skills. Secure attachment provided the emotional safety needed for children to practise self-regulation, attention control and cognitive flexibility. The research directly supports Bowlby's secure base hypothesis: emotional security frees cognitive resources for learning.

Essentials When Studying Child-Father Attachment: A Fundamental View on Safe Haven and Secure Base Phenomena View study ↗

62 citations

Grossmann & Grossmann (2020)

This paper distinguishes between Bowlby's two core attachment functions: the safe haven (comfort when distressed) and the secure base (confidence to explore). The authors demonstrate that fathers and mothers often specialise in different functions. For teachers, the distinction is significant: a classroom needs to serve as both a safe haven during difficulty and a secure base that encourages intellectual risk-taking and exploration.

Three Decades of Research on Individual Teacher-Child Relationships: A Chronological Review View study ↗

61 citations

Spilt & Koomen (2022)

This comprehensive review traces 30 years of research on teacher-child relationships through an attachment lens. It shows that warm, secure teacher-pupil relationships predict academic motivation, behavioural regulation and social competence across age groups. The review identifies specific teacher behaviours, including sensitivity, predictability and emotional availability, that create attachment-like security in the classroom.

The Relationship Between Preschool Teacher Trait Mindfulness and Teacher-Child Relationship Quality View study ↗

33 citations

Wang & Pan (2023)

This study found that teachers with higher trait mindfulness formed closer, less conflictual relationships with young children. Mindful teachers were more attuned to children's emotional signals and responded with greater sensitivity, mirroring the responsive caregiving that Bowlby identified as essential for secure attachment. The findings suggest that mindfulness training for teachers could improve the attachment quality of classroom relationships.

An Attachment Perspective on Dyadic Teacher-Child Relationships: Implications for Effective Classroom Practices View study ↗

3 citations

Spilt & Borremans (2025)

This recent paper provides the most up-to-date application of attachment theory to classroom relationships. It explains how insecure attachment patterns manifest as specific classroom behaviours, including avoidance of help-seeking, attention-seeking disruption and emotional withdrawal. The authors offer concrete strategies for teachers to build secure relational foundations with pupils who have experienced insecure early attachments.

Bowlby's Attachment Theory explains how emotional bonds between infants and caregivers shape psychological development throughout life, demonstrating the important connection between attachment and development. The theory proposes that children are biologically programmed to form attachments as a survival mechanism, with these early bonds influencing future relationships and emotional health. John Bowlby identified four developmental stages: Pre-attachment (0-6 weeks), Attachment-in-the-making (6 weeks-8 months), Clear-cut attachment (8-24 months), and Goal-corrected partnership (24 months onwards).

Bowlby's Attachment Theory describes how the emotional bonds formed between infants and their primary caregivers shape psychological development throughout life. British psychiatrist John Bowlby (1907-1990) developed this groundbreaking framework, which proposes that children are genetically predisposed to form attachments as a survival mechanism. His work has transformed our understanding of child development, influencing everything from parenting approaches to therapeutic interventions. In 2025, Bowlby's insights remain central to how educators and psychologists support children's development, working alongside social learning theories to understand how children grow and learn.

Comparing attachment theories? This article focuses on Bowlby's original theory. For a comparison of multiple attachment theories including Ainsworth's Strange Situation and modern perspectives, see our broader guide to theories of attachment.

Bowlby's theory is rooted in the belief that infants are biologically wired to form attachments, a survival mechanism that ensures protection and care during vulnerability. These early attachments, formed during the initial years of life, are not just transient bonds but play a important role in shaping the child's future wellbeing and relationships. This understanding mirrors how educators approach building knowledge progressively throughout a child's learning process.

Bowlby's Attachment Theory underscores the significance of a secure and consistent attachment to the primary caregiver. Bowlby postulated that disruptions or inconsistencies in these early attachments could potentially lead to a spectrum of mental health and social-emotional learning difficulties in later life.

This perspective marked a significant shift from the dominant theories of his era, which often attributed mental health issues to innate or genetic factors. Instead, Bowlby's theory emphasised the impact of early childhood experiences and their enduring influence on an individual's life trajectory, drawing from psychodynamic perspectives.

Bowlby's theory also introduced the concept of individual differences in attachment patterns. His colleague Mary Ainsworth later expanded on this in her important work on attachment styles. Ainsworth's research further validated Bowlby's theory and provided a framework for understanding the different attachment styles that emerge from the quality of early interactions with caregivers.

John Bowlby's Attachment Theory, developed by British psychiatrist John Bowlby (1907-1990), explains how emotional bonds between infants and caregivers shape psychological development throughout life. Bowlby proposed that children have an innate tendency to form attachments as a survival mechanism, with these early bonds influencing future relationships and emotional health.

Bowlby trained as a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, but his groundbreaking work challenged many existing psychoanalytic assumptions. His clinical observations of children separated from their parents, particularly during World War II, led him to develop his revolutionary theory. Unlike previous theorists who focused on feeding as the primary driver of attachment, Bowlby recognised that emotional connection and responsiveness were the true foundations of secure bonds.

John Bowlby's theory proposes that children are biologically predestined to form emotional attachments with caregivers as a survival mechanism. His attachment theory identifies four developmental stages and explains how these early bonds create internal working models that influence all future relationships and emotional development throughout life.

The theory suggests that attachment behaviours are adaptive strategies that evolved over time. These behaviours, such as crying, smiling, and following, help maintain closeness to caregivers who provide protection and care. These behaviours activate caregiving responses in adults, creating a reciprocal system that ensures infant survival. This biological basis for attachment distinguishes Bowlby's work from earlier psychoanalytic theories.

Attachment theory by John Bowlby explains that infants are biologically wired to form emotional bonds with primary caregivers for survival. This groundbreaking theory describes how these early attachments shape psychological development and influence future relationships throughout an individual's life.

Central to Bowlby's theory is the concept of the "internal working model", a mental representation of oneself, others, and relationships formed through early attachment experiences. Children who experience responsive, consistent caregiving develop positive internal working models, viewing themselves as worthy of love and others as trustworthy. These models become templates for navigating relationships throughout life.

The four stages are: Pre-attachment (0-6 weeks) where infants show no specific attachment; Attachment-in-the-making (6 weeks-8 months) where babies begin recognising familiar caregivers; Clear-cut attachment (8-24 months) where separation anxiety emerges; and Goal-corrected partnership (24 months onwards) where children understand caregiver needs. Each stage builds on the previous one, creating increasingly complex attachment behaviours and emotional bonds.

Bowlby proposed that attachment develops through four distinct stages during early years development. Understanding these stages helps educators and parents recognise normal developmental patterns and identify when children might need additional support. Each stage builds upon the previous one, creating increasingly sophisticated emotional bonds that impact engagement and learning throughout development.

Let's explore each of Bowlby's stages, understanding the emotional milestones and their implications for educators working with young children.

During this initial phase, infants display indiscriminate social responsiveness. They don't show a preference for a primary caregiver and accept comfort from anyone. Newborns use innate behaviours like crying, grasping, and looking to signal their needs and attract adult attention. However, they lack the cognitive ability to distinguish between caregivers.

Teachers working with very young children should understand this lack of specific attachment and focus on providing consistent, responsive care to all infants. Multiple caregivers can meet the infant's needs during this stage without causing distress. The key is ensuring that all interactions are sensitive and responsive, laying the groundwork for later attachment formation.

Infants begin to show preferences for familiar caregivers during this stage. They smile more at those caregivers and are easily calmed by them, though they still accept care from others. This period marks the beginning of genuine attachment as infants develop expectations about caregiver behaviour based on repeated interactions.

This is a important time for educators to build strong bonds with the children in their care by being attentive, responsive, and engaging in positive interactions. Consistent routines help infants develop trust and security. Early years practitioners should aim to provide predictable, warm responses to infant cues, helping children feel safe and understood.

This stage is marked by separation anxiety when the primary caregiver leaves. Infants actively seek closeness and proximity to their preferred caregiver and may show wariness or distress around strangers. The attachment bond is now clearly established, and children use their caregiver as a "secure base" from which to explore the environment.

Teachers can support children experiencing separation anxiety by providing a safe and predictable environment, offering comfort, and encouraging gradual acclimatisation to the classroom. Understanding that separation anxiety is a normal and healthy sign of attachment helps educators respond with patience and empathy rather than frustration.

Children develop a more sophisticated understanding of their caregiver's needs and goals. They can tolerate brief separations and understand that the caregiver will return. Language development enables children to negotiate with caregivers and plan for separations, making transitions less distressing.

Educators can develop this understanding by explaining routines, providing clear expectations, and helping children develop strategies for coping with separation. At this stage, children benefit from discussions about feelings and reassurance about reunion, helping them build confidence in the reliability of important relationships.

Attachment styles are individual patterns of relating to others that develop as a result of early interactions with primary caregivers. These styles influence how people approach relationships, manage emotions, and cope with stress. Mary Ainsworth's "Strange Situation" experiment identified three primary attachment styles: secure, anxious-avoidant (also called anxious-resistant), and anxious-ambivalent. A fourth style, disorganised attachment, was later identified by Main and Solomon.

Understanding these attachment styles is important for educators because they directly impact how children behave in classroom settings, form relationships with teachers and peers, and respond to academic challenges. Each style reflects different adaptations to caregiving experiences and requires tailored support strategies.

Children with secure attachment have caregivers who are consistently responsive and sensitive to their needs. These children feel safe and secure, and they trust that their caregivers will be there for them. They use their caregiver as a secure base for exploration, showing distress when separated but greeting the caregiver warmly upon reunion and quickly returning to play.

In the classroom, securely attached children are typically confident, curious, and able to form positive relationships with teachers and peers. They regulate emotions effectively, seek help when needed, and demonstrate resilience when facing challenges. These children often show higher academic achievement and better social skills compared to children with insecure attachment styles.

Children with anxious-avoidant attachment have caregivers who are emotionally unavailable or consistently rejecting of the child's bids for comfort. These children learn to suppress their emotions and avoid seeking comfort from others as a protective strategy. During separations, they show little distress and actively avoid or ignore the caregiver upon reunion.

In the classroom, these children may appear independent and self-reliant, but they may also struggle to form close relationships with teachers and peers. They often minimise emotional expression and may reject offers of help or support. Teachers might misinterpret their behaviour as maturity or self-sufficiency when actually these children need support in learning to trust and connect with others.

Children with anxious-ambivalent (or anxious-resistant) attachment have caregivers who are inconsistent in their responses, sometimes being responsive and other times being neglectful or intrusive. These children are often anxious and clingy, unable to predict whether their needs will be met. They show intense distress during separations and difficulty being comforted upon reunion, often displaying anger alongside proximity-seeking.

In the classroom, they may seek constant reassurance from teachers and struggle to regulate their emotions. These children often have difficulty concentrating on learning tasks because they're preoccupied with monitoring the teacher's availability and attention. They may exhibit controlling or demanding behaviours as attempts to ensure adult responsiveness.

Children with disorganised attachment have caregivers who are frightening, frightened, or severely inconsistent, often due to trauma, mental illness, or substance abuse. These children display contradictory behaviours, such as seeking comfort from a caregiver while simultaneously avoiding eye contact or showing frozen, dazed expressions. This attachment style represents a breakdown in attachment strategies when the caregiver is both the source of fear and the solution to fear.

In the classroom, they may exhibit behavioural problems, difficulty regulating emotions, and challenges in forming trusting relationships. These children often require specialised support through trauma- informed practise and may benefit from consistent, predictable routines and patient, non-threatening adult interactions.

| Attachment Style | Caregiver Behaviour | Child Response | Classroom Behaviour |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | Consistently responsive and sensitive | Uses caregiver as secure base; distressed at separation but easily comforted | Confident, curious, forms positive relationships, emotionally regulated |

| Anxious-Avoidant | Emotionally unavailable, rejecting | Minimal distress at separation; avoids caregiver at reunion | Appears independent, struggles with close relationships, suppresses emotions |

| Anxious-Ambivalent | Inconsistent, unpredictable | Extreme distress at separation; difficult to comfort, shows anger | Clingy, seeks constant reassurance, poor emotional regulation |

| Disorganised | Frightening, frightened, severely inconsistent | Contradictory behaviours, frozen/dazed responses | Behavioural problems, difficulty trusting, challenges with emotion regulation |

Mary Ainsworth, a developmental psychologist who worked with Bowlby, developed the Strange Situation procedure in the 1970s to empirically measure attachment quality in children aged 12-18 months. This laboratory-based assessment became the gold standard for attachment research and provided important evidence supporting Bowlby's theoretical framework.

The Strange Situation is a structured observation lasting approximately 20 minutes, consisting of eight episodes that progressively increase stress for the infant. The procedure takes place in a comfortable room with toys, and researchers observe the infant's responses to separations and reunions with the caregiver and encounters with a friendly stranger.

The procedure follows a specific sequence designed to activate the attachment system through the stress of separation:

Researchers focus particularly on the reunion episodes, as these most clearly reveal the child's attachment style. Secure children seek proximity and comfort, quickly settling and returning to play. Avoidant children actively avoid or ignore the caregiver. Ambivalent children display anger and resistance alongside proximity-seeking, remaining distressed even after reunion. Disorganised children show contradictory or confused behaviours, reflecting their inability to develop a consistent attachment strategy.

While educators don't conduct formal Strange Situation assessments, understanding this research helps them recognise attachment patterns in everyday classroom situations. Drop-off time, for instance, often mirrors the Strange Situation's separation episodes, revealing how children cope with caregiver absence and whether they use teachers as alternative secure bases.

Ainsworth's work demonstrated that attachment is measurable, observable, and directly linked to caregiver sensitivity, the ability to perceive and interpret infant signals accurately and respond promptly and appropriately. This finding reinforces the importance of teacher responsiveness in educational settings.

The principles of attachment theory extend far beyond infancy, profoundly influencing children's experiences throughout their educational process. Classrooms function as secondary attachment environments where teachers can serve as alternative secure bases, particularly for children who may lack secure attachments at home.

Research consistently demonstrates that positive teacher-student relationships predict academic achievement, school engagement, and social-emotional development. Children who feel securely attached to their teachers show greater academic motivation, better behaviour regulation, and more positive peer relationships. This is especially true for vulnerable children who may be experiencing adversity at home.

Just as infants use caregivers as a secure base for exploration, students use teachers as secure bases for academic and social exploration. A secure classroom base has several key features:

When teachers provide this secure base, children feel confident to take academic risks, ask questions, make mistakes, and engage deeply with learning challenges. They develop what researchers call "academic resilience", the ability to persevere through difficulties because they trust support is available when needed.

Attachment security directly influences learning engagement through several mechanisms. Secure children allocate cognitive resources to learning rather than monitoring adult availability or managing anxiety. They're more likely to seek help appropriately when stuck, rather than giving up (anxious-ambivalent pattern) or refusing assistance (avoidant pattern).

Children with insecure attachment often display learning difficulties that stem not from cognitive limitations but from emotional preoccupations. An anxious-ambivalent child's constant reassurance-seeking interrupts sustained attention to tasks. An avoidant child's reluctance to seek help means they miss opportunities for scaffolding. Understanding these patterns helps teachers recognise when learning difficulties have a ttachment-related roots.

Teachers can intentionally structure classroom environments to support healthy attachment patterns:

The quality of teacher-student relationships serves as a powerful protective factor, particularly for children facing adversity. Research shows that even one secure relationship with a non-parental adult can significantly improve outcomes for at-risk children. Teachers are uniquely positioned to provide this relationship.

Developing secure teacher-student relationships requires intentional effort and specific relational skills. Building relationships starts with teachers reflecting on their own attachment histories and recognising how these influence their interactions with students.

Key relationship-building strategies include:

Some children are more susceptible to relationship quality than others, a phenomenon called "differential susceptibility." Children with difficult temperaments or insecure attachment histories may show the poorest outcomes in unsupportive environments but the best outcomes in highly supportive environments. This means teacher relationship quality matters most for the most vulnerable children.

This research has profound implications: the children who appear most difficult to connect with often benefit most from relationship investment. Teachers who persist in building relationships with resistant or challenging students can achieve significant results.

Attachment theory was developed primarily through research with Western, middle-class families, but attachment needs are universal across cultures. However, the specific behaviours that communicate security vary culturally. Teachers must understand that:

Culturally responsive practise requires teachers to learn about students' cultural backgrounds and adapt relationship-building approaches accordingly, while maintaining the core principles of availability, sensitivity, and responsiveness.

Children with insecure or disorganised attachment require thoughtful, informed support to develop security in educational settings. Understanding attachment patterns allows teachers to interpret challenging behaviours as adaptations rather than defiance, fundamentally shifting the teacher's emotional response and intervention approach.

Teachers may notice various signs suggesting attachment difficulties:

Remember that attachment difficulties exist on a continuum, and many children show mild attachment-related challenges without meeting criteria for attachment disorders. All children benefit from attachment-informed teaching practices.

Children with avoidant patterns have learned that emotional needs go unmet, so they suppress them. Support strategies include:

Children with ambivalent patterns struggle with uncertainty about adult availability. Support strategies include:

Children with disorganised attachment require the most intensive and specialised support, often benefiting from collaboration with mental health professionals. Classroom strategies include:

The most effective support occurs when entire schools adopt attachment-informed practices rather than individual teachers working in isolation. This includes:

Understanding Bowlby's Attachment Theory and the different attachment styles can help educators create a supportive and nurturing learning environment for all children. By being responsive, consistent, and empathetic, teachers can develop secure attachments and promote healthy social-emotional development.

The application of attachment principles in educational settings doesn't require formal assessment or diagnosis. Instead, it involves creating classroom cultures characterised by safety, predictability, and responsive relationships, conditions that benefit all children regardless of attachment history.

Here are research-backed strategies for creating attachment-informed classrooms:

Teachers' own attachment histories influence how they relate to students. Those with secure attachment histories may naturally provide responsive, attuned care. However, teachers with insecure attachment may struggle with specific student behaviours that trigger their own attachment patterns.

For example, a teacher with avoidant attachment might feel uncomfortable with a clingy, anxious-ambivalent child's constant bids for attention. A teacher with anxious attachment might over-identify with an avoidant child's emotional distance. Becoming aware of these patterns through reflection and supervision helps teachers respond to students' needs rather than their own triggered reactions.

While teacher relationships are powerful, recognise their limits. Teachers are not therapists or substitute parents. Children with significant attachment trauma often require specialised therapeutic intervention beyond what classroom relationships can provide.

Teachers should know when to seek support from school counsellors, educational psychologists, or external mental health services. Red flags requiring referral include severe aggression, extreme withdrawal, self-harm, or behaviours suggesting abuse or neglect. Collaborative working with families and specialists ensures children receive thorough support.

Bowlby's maternal deprivation hypothesis proposes that continuous emotional care from a mother or mother substitute is essential for normal psychological development. He argued that prolonged separation from the primary caregiver during the critical period (first 2.5 years) could lead to serious and irreversible developmental consequences. This hypothesis emerged from his observations of children separated from their mothers during World War II evacuations and his work with young offenders.

The hypothesis identifies several potential effects of maternal deprivation, including intellectual development delays, increased aggression, delinquency, and affectionless psychopathy. Bowlby's research with 44 juvenile thieves found that those who experienced early separations were more likely to show emotional detachment and struggle with forming relationships. While later research has refined these ideas, recognising that multiple caregivers can provide adequate emotional support, the core principle remains influential.

For teachers, understanding maternal deprivation helps explain certain behavioural patterns in the classroom. Children who have experienced early separations or inconsistent caregiving may display attention-seeking behaviours, struggle with emotional regulation, or find it difficult to trust adults. Teachers can support these pupils by providing consistent routines and clear expectations, which help create the predictability these children often missed in early development.

Practical strategies include establishing a key person system where vulnerable children have a designated adult they can build trust with, similar to nursery settings. Creating visual timetables and maintaining classroom rituals provides the structure these children need. When children display challenging behaviour, responding with patience rather than punishment acknowledges that their actions may stem from early attachment disruptions rather than deliberate defiance.

Internal working models are mental representations that children develop based on their early attachment experiences. These cognitive frameworks shape how children view themselves, their relationships with others, and the world around them. Bowlby proposed that these models become templates for all future relationships, influencing behaviour and emotional responses throughout life.

When children experience consistent, responsive caregiving, they develop positive internal working models. They come to see themselves as worthy of love and others as trustworthy and reliable. Conversely, inconsistent or neglectful care leads to negative models where children may view themselves as unlovable or others as unpredictable. These models operate largely outside conscious awareness, guiding expectations and interpretations of social interactions.

In the classroom, understanding internal working models helps teachers recognise why certain pupils struggle with trust or seek excessive reassurance. A child with insecure attachment might interpret a teacher's busy moment as rejection, whilst a securely attached child understands the teacher will return their attention when possible. Teachers can support positive model development by providing predictable routines, clear expectations, and consistent emotional availability.

Practical strategies include creating visual timetables that reduce anxiety about transitions, establishing regular one-to-one check-ins with vulnerable pupils, and using consistent language when giving feedback. For instance, rather than saying 'you're being difficult', try 'I can see you're finding this challenging; let's work through it together'. This approach helps reshape negative internal models by demonstrating that adults can be supportive even during struggles.

Research by Main and Goldwyn (1984) showed that internal working models can change through positive relationships, offering hope for children with difficult early experiences. Teachers play a crucial role in this process, potentially serving as corrective attachment figures who challenge negative assumptions about relationships.

Bowlby's Attachment Theory provides a valuable framework for understanding the importance of early relationships in shaping psychological development. By understanding attachment stages and styles, we can create better learning environments. These environments develop secure attachments and promote healthy social-emotional development for all children.

The theory reminds us that children's capacity to learn is fundamentally connected to their sense of safety and security in relationships. Academic achievement doesn't occur in isolation from emotional development, they're intimately intertwined. Children learn best when they feel secure enough to take intellectual risks, knowing that supportive adults will be there to guide them through challenges.

For educators working with children who have experienced attachment disruptions, understanding this framework transforms challenging behaviours from frustrating obstacles into meaningful communications about unmet needs. An anxious-ambivalent child's clinginess becomes understandable as a strategy developed to manage unpredictable caregiving. An avoidant child's rejection of help makes sense as protection against further disappointment.

The early years are formative, and a nurturing educational environment can mitigate the effects of insecure attachment patterns and build resilience. While teachers cannot replace primary caregivers, they can serve as important secondary attachment figures, particularly for vulnerable children. Research consistently shows that even one secure relationship with a caring adult can significantly improve outcomes for children experiencing adversity.

Ultimately, educators who understand and apply the principles of Attachment Theory can make a profound difference in the lives of their students. By developing secure relationships and providing a supportive learning environment, we help children to thrive academically, socially, and emotionally. Creating this secure base allows children to explore the world with confidence and build positive relationships throughout their lives.

As we progress in education, integrating attachment principles with research-informed pedagogical approaches offers a thorough framework for supporting every child's development. This integration recognises that effective teaching addresses the whole child, their emotional needs, relational capacities, and cognitive development- rather than focusing narrowly on academic skills alone.

Teachers should look for signs such as excessive clinginess or withdrawal, difficulty regulating emotions, aggression when separated from caregivers, or struggles with peer relationships. Children with attachment difficulties may also show hypervigilance, difficulty concentrating, or regression in previously mastered skills. Observing these behaviours consistently over time, rather than isolated incidents, can help identify pupils who may benefit from additional support.

Create predictable routines and clear expectations to provide security, and establish yourself as a consistent, reliable adult presence. Use warm but professional interactions, validate emotions, and provide safe spaces for emotional regulation. Implement visual schedules, offer choices when possible, and avoid sudden changes that might trigger anxiety in vulnerable pupils.

Whilst attachment patterns are established early, they continue to influence teenagers' relationships with teachers and peers. Secondary teachers can support students by maintaining consistent boundaries, showing genuine interest in their wellbeing, and understanding that challenging behaviours may stem from earlier attachment difficulties. Building trust through reliable, respectful interactions remains crucial for academic and social success.

Teachers cannot replace primary caregivers but can provide corrective emotional experiences through consistent, supportive relationships. By offering security, predictability, and emotional attunement within the school environment, teachers can help children develop more positive internal working models. However, severe attachment trauma typically requires specialist intervention alongside educational support.

Approach conversations with sensitivity and focus on observable behaviours rather than making judgements about parenting. Share specific examples of classroom behaviours and frame discussions around supporting the child's success at school. Collaborate with parents to understand the child's needs and work together on consistent strategies, whilst following safeguarding procedures if necessary.

Attachment theory in education

Secure relationships in school

Bowlby and Ainsworth identified four attachment patterns that influence how children behave in school. For each classroom behaviour, identify the most likely underlying attachment pattern: Secure, Anxious-Ambivalent, Avoidant or Disorganised.

These peer-reviewed studies examine how Bowlby's attachment theory applies to educational settings, from early years through to secondary school teacher-pupil relationships.

A Secure Base from Which to Regulate: Attachment Security in Toddlerhood as a Predictor of Executive Functioning at School Entry View study ↗

130 citations

Bernier & Beauchamp (2015)

This longitudinal study tracked children from toddlerhood to school entry, finding that securely attached children developed stronger executive functioning skills. Secure attachment provided the emotional safety needed for children to practise self-regulation, attention control and cognitive flexibility. The research directly supports Bowlby's secure base hypothesis: emotional security frees cognitive resources for learning.

Essentials When Studying Child-Father Attachment: A Fundamental View on Safe Haven and Secure Base Phenomena View study ↗

62 citations

Grossmann & Grossmann (2020)

This paper distinguishes between Bowlby's two core attachment functions: the safe haven (comfort when distressed) and the secure base (confidence to explore). The authors demonstrate that fathers and mothers often specialise in different functions. For teachers, the distinction is significant: a classroom needs to serve as both a safe haven during difficulty and a secure base that encourages intellectual risk-taking and exploration.

Three Decades of Research on Individual Teacher-Child Relationships: A Chronological Review View study ↗

61 citations

Spilt & Koomen (2022)

This comprehensive review traces 30 years of research on teacher-child relationships through an attachment lens. It shows that warm, secure teacher-pupil relationships predict academic motivation, behavioural regulation and social competence across age groups. The review identifies specific teacher behaviours, including sensitivity, predictability and emotional availability, that create attachment-like security in the classroom.

The Relationship Between Preschool Teacher Trait Mindfulness and Teacher-Child Relationship Quality View study ↗

33 citations

Wang & Pan (2023)

This study found that teachers with higher trait mindfulness formed closer, less conflictual relationships with young children. Mindful teachers were more attuned to children's emotional signals and responded with greater sensitivity, mirroring the responsive caregiving that Bowlby identified as essential for secure attachment. The findings suggest that mindfulness training for teachers could improve the attachment quality of classroom relationships.

An Attachment Perspective on Dyadic Teacher-Child Relationships: Implications for Effective Classroom Practices View study ↗

3 citations

Spilt & Borremans (2025)

This recent paper provides the most up-to-date application of attachment theory to classroom relationships. It explains how insecure attachment patterns manifest as specific classroom behaviours, including avoidance of help-seeking, attention-seeking disruption and emotional withdrawal. The authors offer concrete strategies for teachers to build secure relational foundations with pupils who have experienced insecure early attachments.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/bowlbys-attachment-theory#article","headline":"Bowlby's Attachment Theory","description":"Explore Bowlby's Attachment Theory: understand its stages, impact on child development, mental health, and its application in therapeutic settings.","datePublished":"2023-06-30T15:40:11.885Z","dateModified":"2026-02-11T12:13:20.871Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/bowlbys-attachment-theory"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a5bb997eb80857c4d759b_696a5bb8fb69181f97fa4ca7_bowlbys-attachment-theory-infographic.webp","wordCount":5603},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/bowlbys-attachment-theory#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Bowlby's Attachment Theory","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/bowlbys-attachment-theory"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers recognise attachment difficulties in their pupils?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers should look for signs such as excessive clinginess or withdrawal, difficulty regulating emotions, aggression when separated from caregivers, or struggles with peer relationships. Children with attachment difficulties may also show hypervigilance, difficulty concentrating, or regression in previously mastered skills. Observing these behaviours consistently over time, rather than isolated incidents, can help identify pupils who may benefit from additional support."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What classroom strategies support children with insecure attachment?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Create predictable routines and clear expectations to provide security, and establish yourself as a consistent, reliable adult presence. Use warm but professional interactions, validate emotions, and provide safe spaces for emotional regulation. Implement visual schedules, offer choices when possible, and avoid sudden changes that might trigger anxiety in vulnerable pupils."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How does attachment theory apply to secondary school students?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Whilst attachment patterns are established early, they continue to influence teenagers' relationships with teachers and peers. Secondary teachers can support students by maintaining consistent boundaries, showing genuine interest in their wellbeing, and understanding that challenging behaviours may stem from earlier attachment difficulties. Building trust through reliable, respectful interactions remains crucial for academic and social success."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Can teachers help repair damaged attachment patterns?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers cannot replace primary caregivers but can provide corrective emotional experiences through consistent, supportive relationships. By offering security, predictability, and emotional attunement within the school environment, teachers can help children develop more positive internal working models. However, severe attachment trauma typically requires specialist intervention alongside educational support."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How should teachers communicate with parents about attachment concerns?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Approach conversations with sensitivity and focus on observable behaviours rather than making judgements about parenting. Share specific examples of classroom behaviours and frame discussions around supporting the child's success at school. Collaborate with parents to understand the child's needs and work together on consistent strategies, whilst following safeguarding procedures if necessary."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Further Reading","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Attachment theory research"}}]}]}