Jerome Bruner's Theories

Explore Jerome Bruner's revolutionary educational theories including spiral curriculum and discovery learning to transform your teaching and boost student engagement.

Jerome Bruner (1915-2016) was a Harvard psychologist who transformed how we understand learning and cognitive development. He pioneered discovery learning, the spiral curriculum, and scaffolding, fundamentally changing how teachers approach instruction. His theories shifted education from passive reception to active construction of knowledge.

Jerome Seymour Bruner, a highly influential psychologist, made groundbreaking contributions to the fields of cognitive development, educational psychology, and developmental psychology. Born in New York City in 1915, Bruner pursued his degree in psychology at Duke University before obtaining his doctorate at Harvard University.

| Stage/Level | Age Range | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enactive Mode | 0-1 years | Learning through physical manipulation and action | Use hands-on materials, manipulatives, and physical activities |

| Iconic Mode | 1-6 years | Learning through visual representations and mental images | Incorporate pictures, diagrams, videos, and visual demonstrations |

| Symbolic Mode | 7 years and up | Learning through abstract symbols, language, and logic | Use written text, mathematical symbols, and abstract reasoning activities |

| Discovery Learning | All ages | Active exploration, experiential learning, trial and error | Create exploration opportunities, student-centered activities, minimal direct instruction |

| Spiral Curriculum | All ages | Revisiting topics at increasing levels of complexity | Design curriculum that returns to key concepts with greater depth over time |

Throughout his illustrious career, he worked alongside eminent psychologists, shaping our understanding of the human mind and its development.

Bruner's work at Harvard University led to a series of groundbreaking discoveries in cognitive development. His theories have had a lasting impact on educational thinking, transforming the way educators approach teaching and learning. Like other pioneering theorists such as Piaget and Vygotsky, Bruner emphasised the active role students play in constructing their own understanding.

As an advocate for understanding the intricacies of the human mind, Bruner examined deep into the processes that influence cognitive development, paving the way for new perspectives in educational psychology. His work aligns closely with constructivist approaches to learning, where students build knowledge through direct experience and exploration.

One of Bruner's most significant contributions to the field of developmental psychology was his theory of instruction, which emphasised the importance of discovery learning and the active engagement of learners in the educational process. This approach contrasts with more structured methods like direct instruction, instead promoting inquiry-based exploration.

This revolutionary approach to teaching has inspired countless educators to adopt more student-centered methods, developing creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills in their classrooms. Modern applications include project-based learning environments that encourage students to investigate and create.

Jerome Bruner's work also extended to the field of language acquisition and its connection to cognitive development. His research revealed the crucial role that language plays in shaping our thoughts and understanding of the world, highlighting the importance of oracy in educational settings. This insight has been instrumental in helping educators develop more effective strategies for teaching language and communication skills to students, while also providing meaningful feedback to support their learning progress.

As a testament to his impact on the field of psychology, Bruner received numerous accolades, similar to other influential theorists like Bandura whose work on social learning complemented Bruner's theories. Understanding how memory functions in learning has become crucial for implementing Bruner's ideas effectively in modern classrooms.

Bruner's influence extends far beyond academic psychology into practical classroom applications. His work bridges the gap between cognitive development theory and educational practice, making complex psychological concepts accessible to educators. Unlike purely theoretical frameworks, Bruner's approaches offer concrete strategies that teachers can implement immediately.

What sets Bruner apart from other educational theorists is his emphasis on the learner as an active participant in knowledge construction. Rather than viewing students as passive recipients of information, he positioned them as curious investigators capable of discovering principles through guided exploration. This perspective fundamentally shifted how educators approach curriculum design and instructional methods.

His collaboration with other prominent psychologists, including Jean Piagetand Lev Vygotsky, helped synthesise different streams of cognitive development theory. However, Bruner's unique contribution lies in his practical translation of these theories into educational frameworks that remain relevant from primary schools to universities.

Modern educators continue to draw upon Bruner's insights when designing inquiry-based learning experiences and scaffolded instruction. His concept of spiral curriculum - where complex ideas are introduced simply and then revisited with increasing sophistication - has become fundamental to contemporary teaching strategies. This approach ensures that learning builds progressively, allowing students to develop deeper understanding over time rather than encountering concepts in isolation.

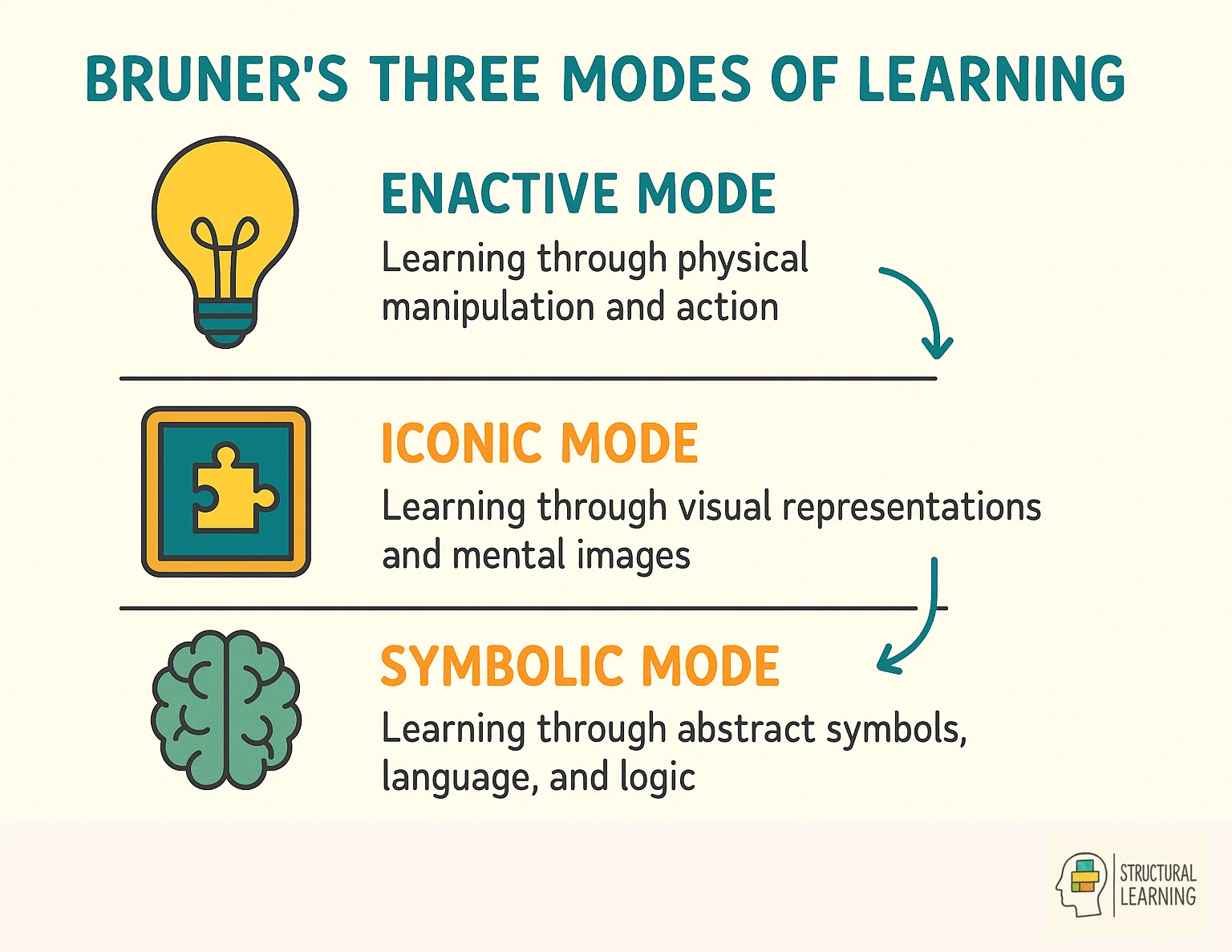

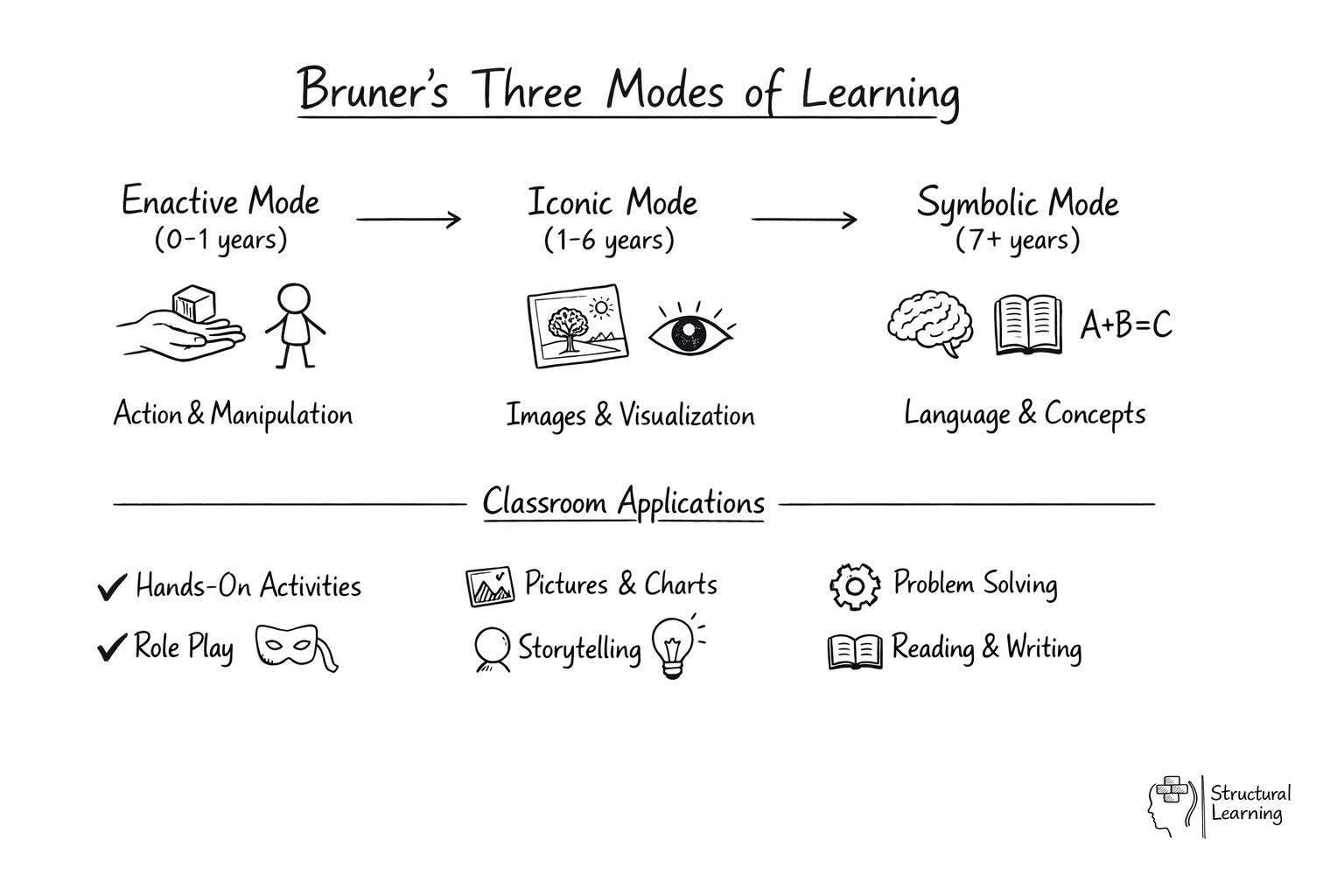

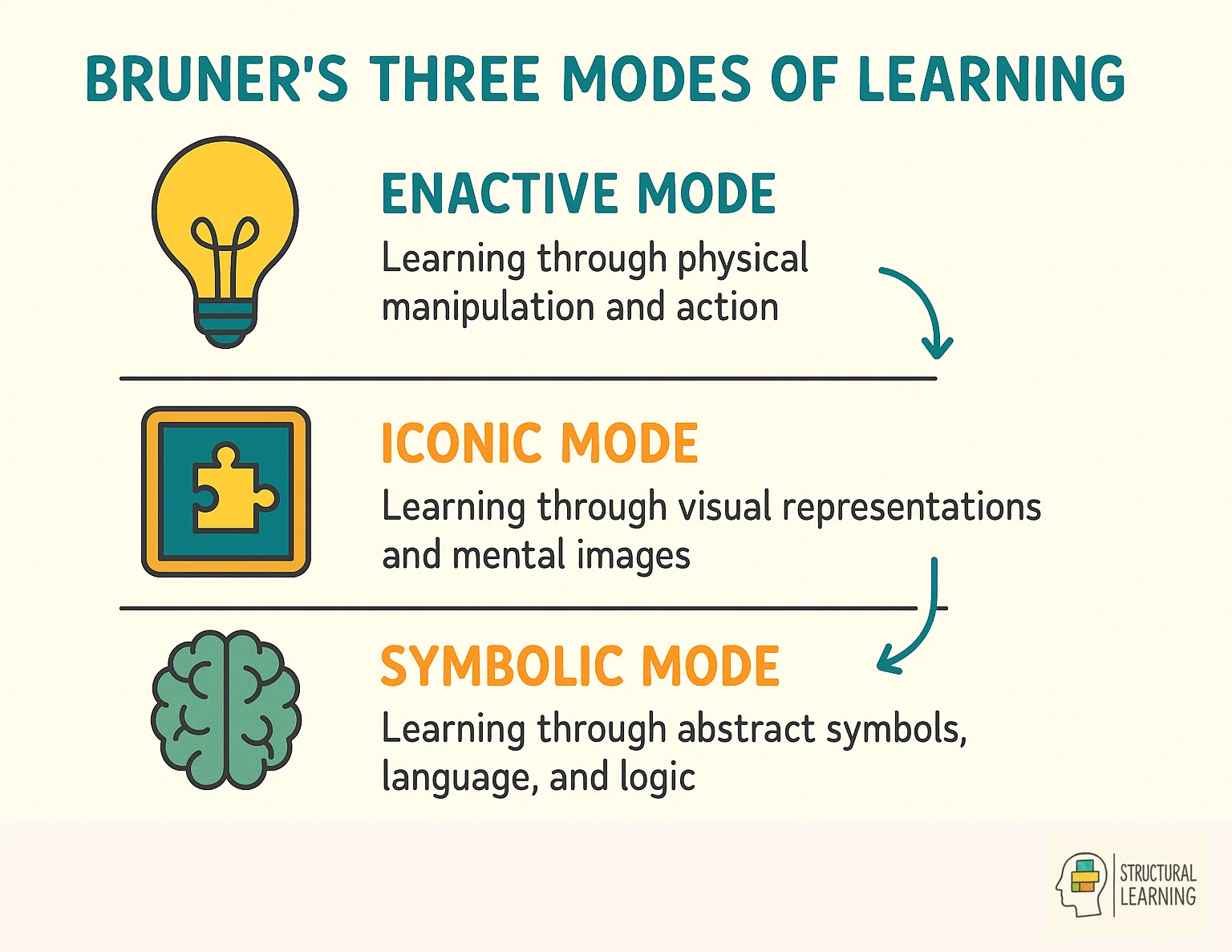

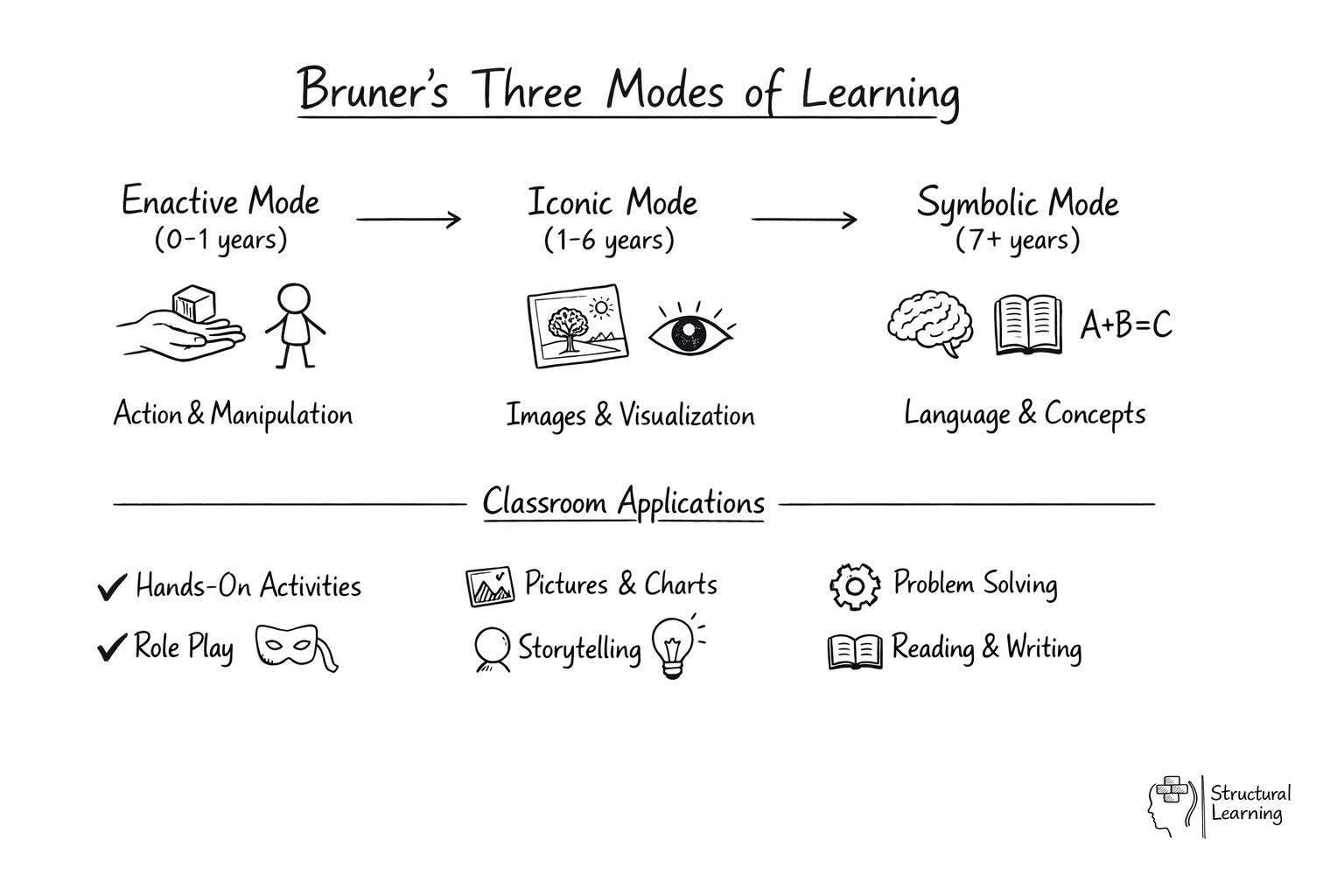

Jerome Bruner's three modes of representation form the cornerstone of his cognitive development theory, proposing that learners progress through distinct stages of understanding. The enactive mode involves learning through direct physical manipulation and motor activities, the iconic mode relies on visual imagery and mental pictures, whilst the symbolic mode employs abstract symbols such as language and mathematical notation. Unlike Piaget's rigid developmental stages, Bruner argued that these modes remain accessible throughout life, with effective learning often requiring movement between all three representations.

In classroom practice, this theory suggests that optimal learning sequences should begin with concrete, hands-on experiences before progressing to visual representations and finally abstract concepts. For instance, when teaching fractions, pupils might first physically divide objects (enactive), then work with visual diagrams and pie charts (iconic), before manipulating algebraic expressions (symbolic). This progression aligns with research from cognitive scientists like John Sweller, whose cognitive load theory demonstrates that concrete experiences reduce mental burden when processing new information.

Successful implementation requires teachers to recognise that learners may need to revisit earlier modes when encountering difficulty with abstract concepts. Rather than viewing this as regression, educators should embrace the spiral curriculum approach, allowing pupils to strengthen their understanding through multiple representational pathways whilst building towards increasingly sophisticated symbolic thinking.

Jerome Bruner's Discovery Learning Theory transformed classroom practice by positioning learners as active investigators rather than passive recipients of knowledge. This pedagogical approach encourages students to explore concepts, identify patterns, and construct understanding through guided investigation. Unlike traditional direct instruction, discovery learning emphasises the process of inquiry itself, allowing students to develop critical thinking skills alongside subject-specific knowledge.

The theory operates on three fundamental principles: students learn best when they actively engage with material, prior knowledge serves as a foundation for new discoveries, and social interaction enhances the learning process. Vygotsky's zone of proximal development complements Bruner's approach, suggesting that strategic teacher guidance during discovery activities maximises learning potential. However, John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates the importance of providing sufficient scaffolding to prevent students from becoming overwhelmed by complex problem-solving tasks.

In classroom practice, effective discovery learning requires careful planning and strategic intervention. Teachers might present students with intriguing phenomena, pose thought-provoking questions, or provide manipulative materials that encourage exploration. The key lies in balancing freedom with structure, ensuring students have sufficient support to make meaningful discoveries whilst maintaining the autonomy that makes learning personally significant and memorable.

Bruner's spiral curriculum represents one of his most enduring contributions to educational theory, proposing that any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development. This approach involves revisiting core concepts repeatedly throughout a learner's educational journey, with each encounter building greater complexity and sophistication upon previous understanding. Rather than presenting topics as discrete, one-time events, the spiral curriculum ensures that fundamental ideas are continuously reinforced and expanded, allowing students to develop increasingly nuanced comprehension over time.

The spiral approach aligns smoothly with Bruner's three modes of representation, as learners encounter concepts first through enactive experiences, progress to iconic representations, and eventually master symbolic understanding. For instance, mathematical concepts like fractions might begin with physical manipulation of objects in primary school, advance to visual diagrams in middle years, and culminate in abstract algebraic expressions. This progression honours cognitive development whilst maintaining intellectual rigour at every stage.

In classroom practice, educators implementing spiral curriculum design should identify the core concepts within their subject area that warrant repeated exploration. Each revisit should deepen understanding rather than merely repeat previous learning, incorporating new contexts, applications, and connections. This approach particularly benefits learners who may not grasp concepts immediately, providing multiple opportunities for mastery whilst continuously challenging those ready for advanced thinking.

Bruner's approach to scaffolding extends beyond Vygotsky's foundational concept by emphasising the gradual transfer of responsibility from teacher to learner through carefully structured discovery experiences. Unlike direct instruction, Bruner's scaffolding model encourages educators to provide just enough support to enable students to explore concepts independently, then systematically withdraw assistance as competence develops. This process requires teachers to continuously assess learners' understanding and adjust their guidance accordingly, creating what Bruner termed "episodes of joint problem-solving" between educator and student.

The effectiveness of Bruner's scaffolding approach aligns with John Sweller's cognitive load theory, as it prevents learners from becoming overwhelmed whilst maintaining intellectual challenge. Teachers implement this through techniques such as questioning sequences that guide discovery, providing conceptual frameworks before detailed exploration, and offering procedural prompts that fade over time. Research by Wood, Bruner, and Ross demonstrates that effective scaffolding involves maintaining learner motivation, highlighting critical features of tasks, and controlling frustration levels through appropriate challenge.

In classroom practice, educators can apply Bruner's scaffolding principles by beginning lessons with familiar contexts before introducing new concepts, using visual aids and manipulatives as temporary supports, and encouraging peer collaboration where more capable students naturally provide scaffolding for others. The key lies in recognising when to step back, allowing learners to construct their own understanding whilst remaining available to provide targeted support when needed.

Bruner's spiral curriculum concept transforms classroom practice by encouraging teachers to revisit key concepts at increasing levels of complexity throughout the academic year. Rather than treating topics as discrete units, educators can introduce fundamental principles early through concrete, hands-on activities, then systematically deepen understanding through more abstract representations. For instance, mathematical concepts like fractions can begin with physical manipulatives in early years, progress to visual diagrams, and finally advance to algebraic expressions as students mature cognitively.

The three modes of representation, enactive, iconic, and symbolic, provide a practical framework for lesson planning across all subject areas. Effective teachers sequence learning experiences to move students through these stages naturally. In science lessons, students might first conduct physical experiments (enactive), then examine diagrams and charts (iconic), before engaging with formulae and theoretical models (symbolic). This progression ensures that abstract concepts are anchored in concrete experience, reducing cognitive load and improving retention.

Discovery learning, when properly scaffolded, encourages students to construct their own understanding whilst maintaining clear learning objectives. Teachers can design guided investigations where students explore predetermined concepts through structured inquiry, rather than completely unstructured exploration. This approach develops critical thinking skills whilst ensuring curriculum coverage, striking the essential balance between student agency and educational outcomes.

Jerome Bruner (1915-2016) was a Harvard psychologist who transformed how we understand learning and cognitive development. He pioneered discovery learning, the spiral curriculum, and scaffolding, fundamentally changing how teachers approach instruction. His theories shifted education from passive reception to active construction of knowledge.

Jerome Seymour Bruner, a highly influential psychologist, made groundbreaking contributions to the fields of cognitive development, educational psychology, and developmental psychology. Born in New York City in 1915, Bruner pursued his degree in psychology at Duke University before obtaining his doctorate at Harvard University.

| Stage/Level | Age Range | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enactive Mode | 0-1 years | Learning through physical manipulation and action | Use hands-on materials, manipulatives, and physical activities |

| Iconic Mode | 1-6 years | Learning through visual representations and mental images | Incorporate pictures, diagrams, videos, and visual demonstrations |

| Symbolic Mode | 7 years and up | Learning through abstract symbols, language, and logic | Use written text, mathematical symbols, and abstract reasoning activities |

| Discovery Learning | All ages | Active exploration, experiential learning, trial and error | Create exploration opportunities, student-centered activities, minimal direct instruction |

| Spiral Curriculum | All ages | Revisiting topics at increasing levels of complexity | Design curriculum that returns to key concepts with greater depth over time |

Throughout his illustrious career, he worked alongside eminent psychologists, shaping our understanding of the human mind and its development.

Bruner's work at Harvard University led to a series of groundbreaking discoveries in cognitive development. His theories have had a lasting impact on educational thinking, transforming the way educators approach teaching and learning. Like other pioneering theorists such as Piaget and Vygotsky, Bruner emphasised the active role students play in constructing their own understanding.

As an advocate for understanding the intricacies of the human mind, Bruner examined deep into the processes that influence cognitive development, paving the way for new perspectives in educational psychology. His work aligns closely with constructivist approaches to learning, where students build knowledge through direct experience and exploration.

One of Bruner's most significant contributions to the field of developmental psychology was his theory of instruction, which emphasised the importance of discovery learning and the active engagement of learners in the educational process. This approach contrasts with more structured methods like direct instruction, instead promoting inquiry-based exploration.

This revolutionary approach to teaching has inspired countless educators to adopt more student-centered methods, developing creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills in their classrooms. Modern applications include project-based learning environments that encourage students to investigate and create.

Jerome Bruner's work also extended to the field of language acquisition and its connection to cognitive development. His research revealed the crucial role that language plays in shaping our thoughts and understanding of the world, highlighting the importance of oracy in educational settings. This insight has been instrumental in helping educators develop more effective strategies for teaching language and communication skills to students, while also providing meaningful feedback to support their learning progress.

As a testament to his impact on the field of psychology, Bruner received numerous accolades, similar to other influential theorists like Bandura whose work on social learning complemented Bruner's theories. Understanding how memory functions in learning has become crucial for implementing Bruner's ideas effectively in modern classrooms.

Bruner's influence extends far beyond academic psychology into practical classroom applications. His work bridges the gap between cognitive development theory and educational practice, making complex psychological concepts accessible to educators. Unlike purely theoretical frameworks, Bruner's approaches offer concrete strategies that teachers can implement immediately.

What sets Bruner apart from other educational theorists is his emphasis on the learner as an active participant in knowledge construction. Rather than viewing students as passive recipients of information, he positioned them as curious investigators capable of discovering principles through guided exploration. This perspective fundamentally shifted how educators approach curriculum design and instructional methods.

His collaboration with other prominent psychologists, including Jean Piagetand Lev Vygotsky, helped synthesise different streams of cognitive development theory. However, Bruner's unique contribution lies in his practical translation of these theories into educational frameworks that remain relevant from primary schools to universities.

Modern educators continue to draw upon Bruner's insights when designing inquiry-based learning experiences and scaffolded instruction. His concept of spiral curriculum - where complex ideas are introduced simply and then revisited with increasing sophistication - has become fundamental to contemporary teaching strategies. This approach ensures that learning builds progressively, allowing students to develop deeper understanding over time rather than encountering concepts in isolation.

Jerome Bruner's three modes of representation form the cornerstone of his cognitive development theory, proposing that learners progress through distinct stages of understanding. The enactive mode involves learning through direct physical manipulation and motor activities, the iconic mode relies on visual imagery and mental pictures, whilst the symbolic mode employs abstract symbols such as language and mathematical notation. Unlike Piaget's rigid developmental stages, Bruner argued that these modes remain accessible throughout life, with effective learning often requiring movement between all three representations.

In classroom practice, this theory suggests that optimal learning sequences should begin with concrete, hands-on experiences before progressing to visual representations and finally abstract concepts. For instance, when teaching fractions, pupils might first physically divide objects (enactive), then work with visual diagrams and pie charts (iconic), before manipulating algebraic expressions (symbolic). This progression aligns with research from cognitive scientists like John Sweller, whose cognitive load theory demonstrates that concrete experiences reduce mental burden when processing new information.

Successful implementation requires teachers to recognise that learners may need to revisit earlier modes when encountering difficulty with abstract concepts. Rather than viewing this as regression, educators should embrace the spiral curriculum approach, allowing pupils to strengthen their understanding through multiple representational pathways whilst building towards increasingly sophisticated symbolic thinking.

Jerome Bruner's Discovery Learning Theory transformed classroom practice by positioning learners as active investigators rather than passive recipients of knowledge. This pedagogical approach encourages students to explore concepts, identify patterns, and construct understanding through guided investigation. Unlike traditional direct instruction, discovery learning emphasises the process of inquiry itself, allowing students to develop critical thinking skills alongside subject-specific knowledge.

The theory operates on three fundamental principles: students learn best when they actively engage with material, prior knowledge serves as a foundation for new discoveries, and social interaction enhances the learning process. Vygotsky's zone of proximal development complements Bruner's approach, suggesting that strategic teacher guidance during discovery activities maximises learning potential. However, John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates the importance of providing sufficient scaffolding to prevent students from becoming overwhelmed by complex problem-solving tasks.

In classroom practice, effective discovery learning requires careful planning and strategic intervention. Teachers might present students with intriguing phenomena, pose thought-provoking questions, or provide manipulative materials that encourage exploration. The key lies in balancing freedom with structure, ensuring students have sufficient support to make meaningful discoveries whilst maintaining the autonomy that makes learning personally significant and memorable.

Bruner's spiral curriculum represents one of his most enduring contributions to educational theory, proposing that any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development. This approach involves revisiting core concepts repeatedly throughout a learner's educational journey, with each encounter building greater complexity and sophistication upon previous understanding. Rather than presenting topics as discrete, one-time events, the spiral curriculum ensures that fundamental ideas are continuously reinforced and expanded, allowing students to develop increasingly nuanced comprehension over time.

The spiral approach aligns smoothly with Bruner's three modes of representation, as learners encounter concepts first through enactive experiences, progress to iconic representations, and eventually master symbolic understanding. For instance, mathematical concepts like fractions might begin with physical manipulation of objects in primary school, advance to visual diagrams in middle years, and culminate in abstract algebraic expressions. This progression honours cognitive development whilst maintaining intellectual rigour at every stage.

In classroom practice, educators implementing spiral curriculum design should identify the core concepts within their subject area that warrant repeated exploration. Each revisit should deepen understanding rather than merely repeat previous learning, incorporating new contexts, applications, and connections. This approach particularly benefits learners who may not grasp concepts immediately, providing multiple opportunities for mastery whilst continuously challenging those ready for advanced thinking.

Bruner's approach to scaffolding extends beyond Vygotsky's foundational concept by emphasising the gradual transfer of responsibility from teacher to learner through carefully structured discovery experiences. Unlike direct instruction, Bruner's scaffolding model encourages educators to provide just enough support to enable students to explore concepts independently, then systematically withdraw assistance as competence develops. This process requires teachers to continuously assess learners' understanding and adjust their guidance accordingly, creating what Bruner termed "episodes of joint problem-solving" between educator and student.

The effectiveness of Bruner's scaffolding approach aligns with John Sweller's cognitive load theory, as it prevents learners from becoming overwhelmed whilst maintaining intellectual challenge. Teachers implement this through techniques such as questioning sequences that guide discovery, providing conceptual frameworks before detailed exploration, and offering procedural prompts that fade over time. Research by Wood, Bruner, and Ross demonstrates that effective scaffolding involves maintaining learner motivation, highlighting critical features of tasks, and controlling frustration levels through appropriate challenge.

In classroom practice, educators can apply Bruner's scaffolding principles by beginning lessons with familiar contexts before introducing new concepts, using visual aids and manipulatives as temporary supports, and encouraging peer collaboration where more capable students naturally provide scaffolding for others. The key lies in recognising when to step back, allowing learners to construct their own understanding whilst remaining available to provide targeted support when needed.

Bruner's spiral curriculum concept transforms classroom practice by encouraging teachers to revisit key concepts at increasing levels of complexity throughout the academic year. Rather than treating topics as discrete units, educators can introduce fundamental principles early through concrete, hands-on activities, then systematically deepen understanding through more abstract representations. For instance, mathematical concepts like fractions can begin with physical manipulatives in early years, progress to visual diagrams, and finally advance to algebraic expressions as students mature cognitively.

The three modes of representation, enactive, iconic, and symbolic, provide a practical framework for lesson planning across all subject areas. Effective teachers sequence learning experiences to move students through these stages naturally. In science lessons, students might first conduct physical experiments (enactive), then examine diagrams and charts (iconic), before engaging with formulae and theoretical models (symbolic). This progression ensures that abstract concepts are anchored in concrete experience, reducing cognitive load and improving retention.

Discovery learning, when properly scaffolded, encourages students to construct their own understanding whilst maintaining clear learning objectives. Teachers can design guided investigations where students explore predetermined concepts through structured inquiry, rather than completely unstructured exploration. This approach develops critical thinking skills whilst ensuring curriculum coverage, striking the essential balance between student agency and educational outcomes.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/jerome-bruners-theories#article","headline":"Jerome Bruner's Theories","description":"Discover Jerome Bruner's transformative educational theories, from the spiral curriculum to narrative learning.","datePublished":"2023-05-03T10:09:41.838Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/jerome-bruners-theories"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69525696614bbe7fdd4f3946_6952569386144ff04bab7ead_jerome-bruners-theories-infographic.webp","wordCount":3984},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/jerome-bruners-theories#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Jerome Bruner's Theories","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/jerome-bruners-theories"}]}]}