Developing emotional intelligence in the classroom

Discover proven strategies for teachers to develop student emotional intelligence, building empathy and social skills for classroom and life success.

Discover proven strategies for teachers to develop student emotional intelligence, building empathy and social skills for classroom and life success.

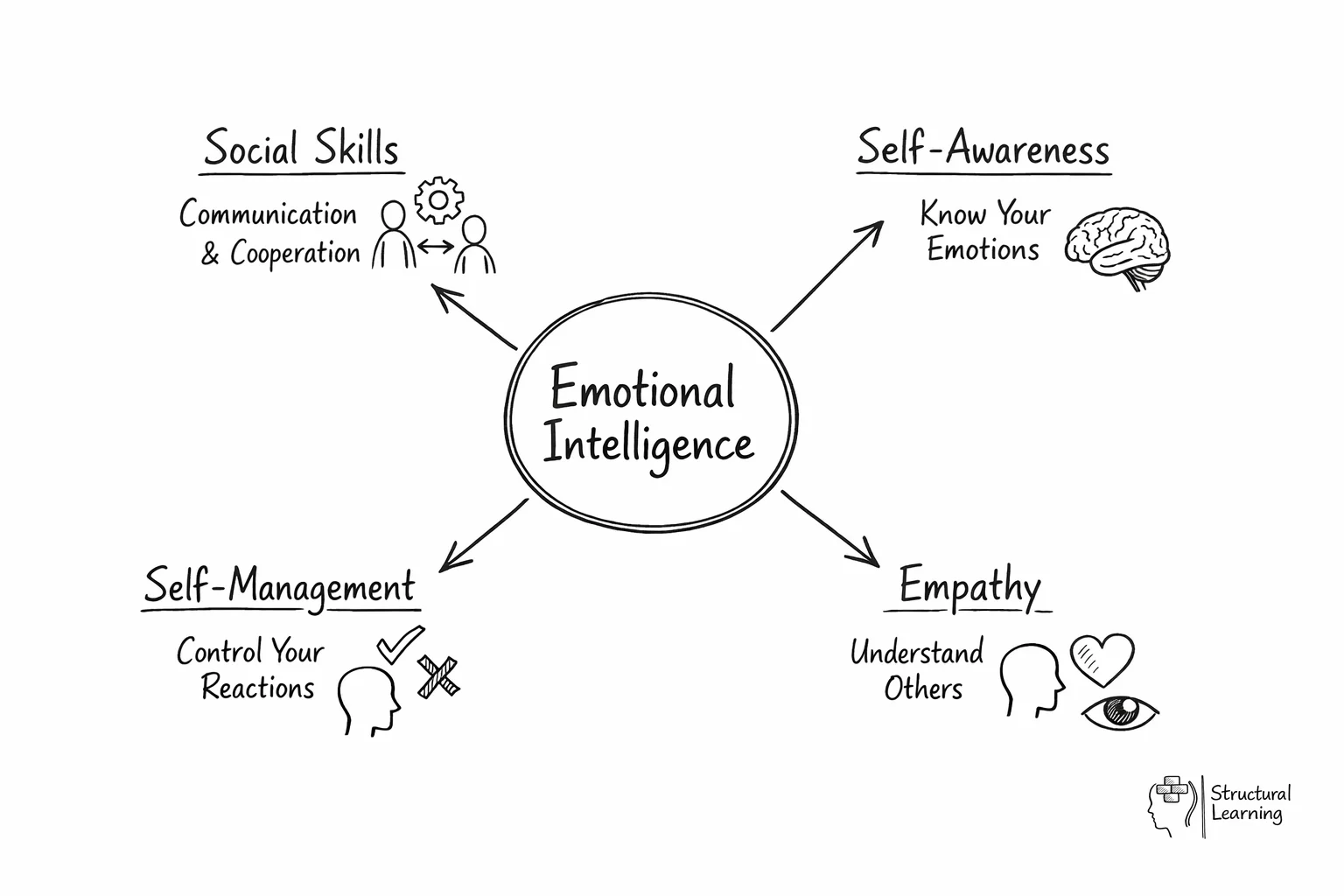

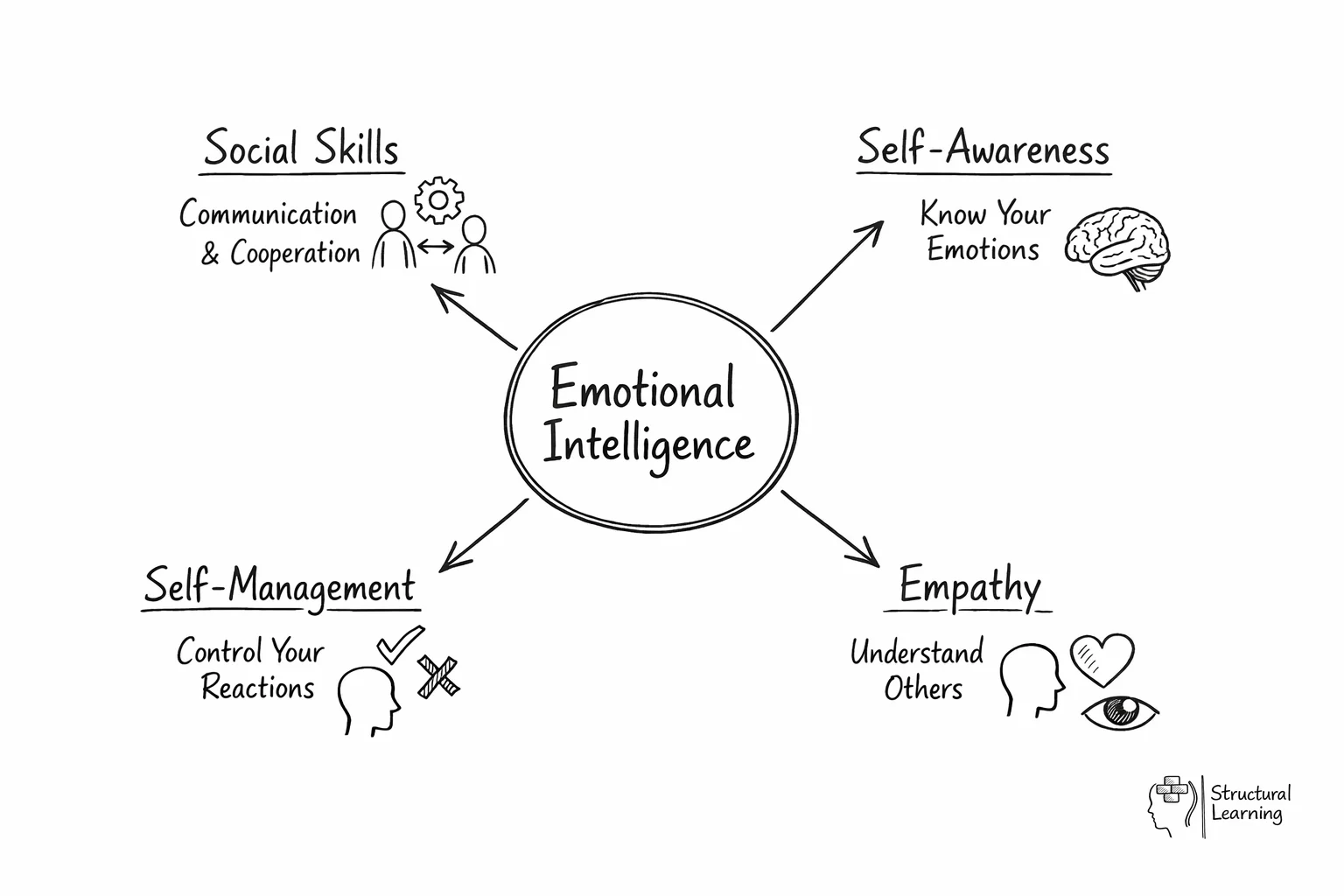

Emotional Intelligence (EI) is a facet of human ability that goes beyond cognitive intelligence and cognitive abilities. It encompasses the skills necessary to manage one's emotions, comprehend others' feelings, and navigate social relationships.

EI is pivotal in building stronger relationships and is particularly beneficial in difficult situations where interpersonal skills and active listening are key. It includes the ability to recognise one's own and others' emotions using tools like an emotion wheel(Emotion Recognition Ability), the capacity for active emotional understanding, and the aptitude to communicate affect effectively through nonverbal communication and movement and relationship play.

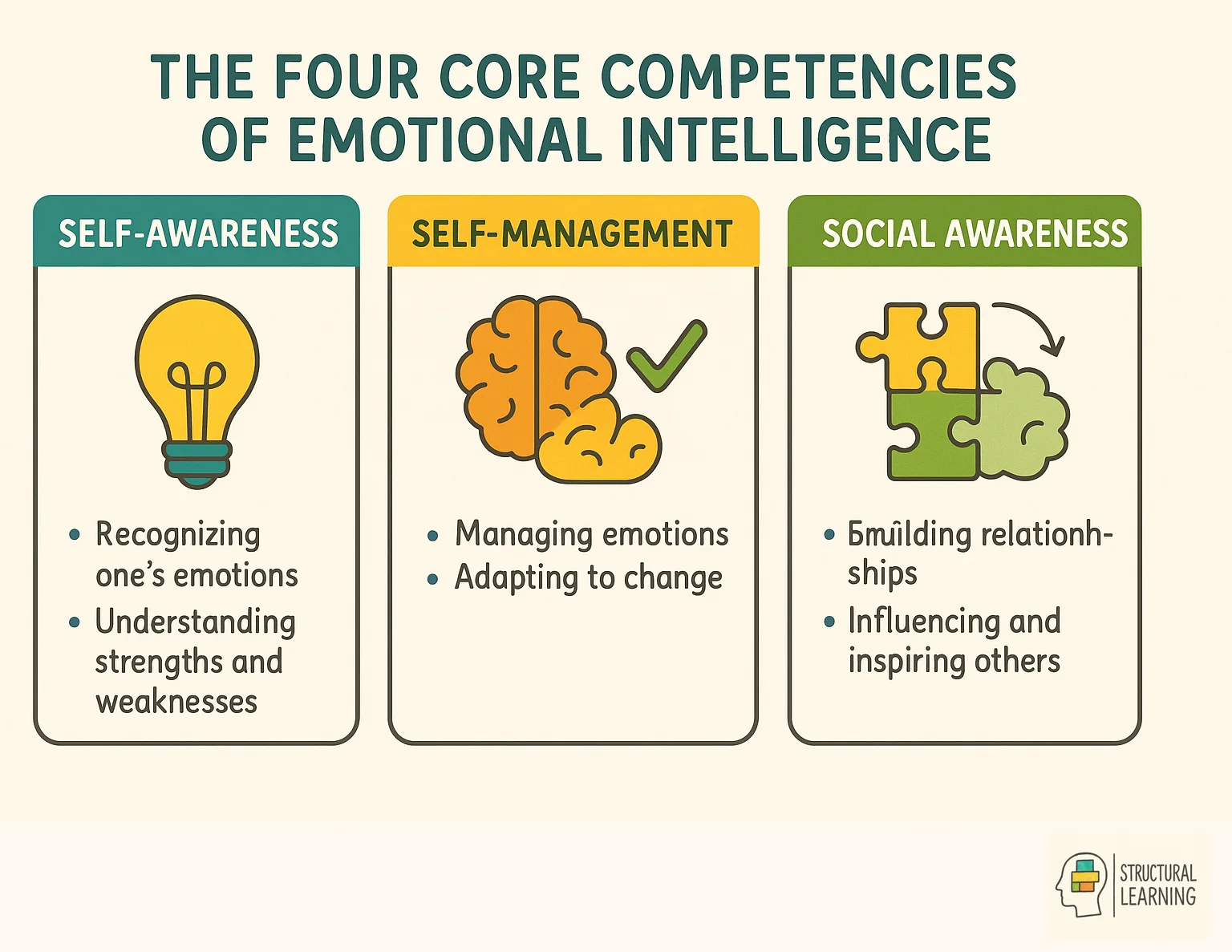

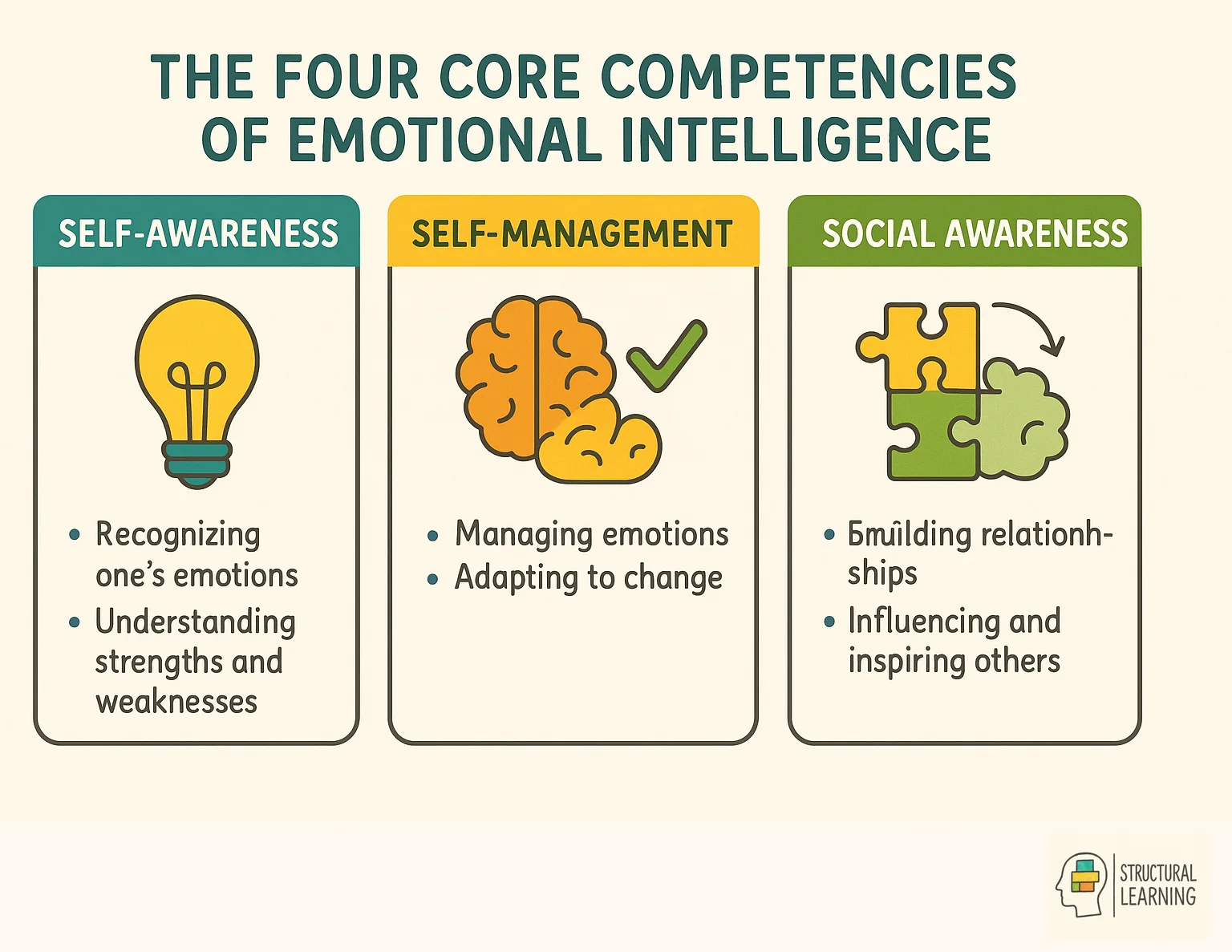

It's a set of emotional abilities that, when harnessed, can lead to improved job satisfaction and conflict management. Unlike the more static measure of IQ, EI skills can be developed and refined with practice and mindfulness. The essence of EI lies in four core competencies:

Through the cultivation of these competencies, individuals can achieve a harmony between heart and mind, ultimately enhancing both personal and professional spheres of life.

Post-Covid evidence indicates significantly more pupils now require mental health support, highlighting a significant decline in emotional wellbeing and resilience. The pandemic disrupted normal social development and created widespread anxiety that continues to impact classroom behaviour and learning. Students are displaying increased emotional dysregulation and reduced capacity to manage social relationships effectively.

If we consider the impact of the Covid pandemic, evidence suggests that children's and young people's mental well-being has been significantly impacted. For example, referrals for mental health support increased substantially during 2021 for children and young people's mental and physical health services compared with the same period in 2019.

A relationship can also be found between well-being and pupils' experiences of transformative social behaviour whilst at school, with students showing poorer happiness and anxiousness because of peers' classroom behaviour. (GOV 2021)

Between March and June 2020, a period when schools were closed to most pupils, symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder were found to have significantly increased in children and young people aged between 7.5 and 12 years old compared to immediately before the pandemic. The effects of lockdown and a decline in well-being can be seen in data collected across 2020 and 2021, showing students could concentrate very (25%) or quite (59%) well in lessons in their classroom (84% very/quite well), whilst 16% said they could not concentrate very or well at all. Further, 39% of pupils were very worried about catching up on their learning.

As a practitioner being able to use emotionally intelligent strategies with students by talking about experiences, developing confidence, and supporting them to develop mindfulness strategies has and can support a positive classroom experience. By September 2020, relative to the March to June 2020 lockdown, reported behavioural, attention, and emotional difficulties in children had returned to, and stabilized at, a lower level. (Gov 2021).

As a result of the pandemic, emotional intelligence, therefore, has never been more important as a tool in the practitioners' toolbox. As understanding a pupil's feelings and emotions and being empathetic can increase engagement and well-being.

The amygdala triggers fight-or-flight responses when students feel threatened, which can appear as emotional outbursts, particularly in neurodivergent pupils. Negative experiences create stronger neural pathways than positive ones, making fear-based memory more persistent and impactful on learning. Understanding these brain mechanisms helps teachers create emotionally safe learning environments that support both growth mindset and academic achievement through effective scaffolding techniques.

Students with special educational needs may require additional support to develop emotional regulation skills. Teachers can use effective questioning strategies to help students reflect on their emotional responses and develop better self-awareness. Providing regular feedback about emotional progress helps maintain motivation throughout the learning process. These approaches support active learning by creating emotionally safe environments where students feel supported to take intellectual risks., facilitating greater engagement and success in their educational journeys.

Implement emotion check-ins as regular activities using tools like the Zones of Regulation, conduct role-playing exercises that simulate real-world social situations, and encourage mindfulness through activities like deep breathing or visualisation. Encourage regular self-reflection through journaling.

To actively creates emotional intelligence, educators can employ several strategies:

By consistently implementing these strategies, teachers can create a classroom culture that values and supports emotional intelligence, ultimately enhancing student well-being and academic performance.

Teaching emotional intelligence requires intentional and structured approaches that move beyond incidental learning to explicit skill development. The most effective method is through emotion coaching, where teachers model emotional awareness by verbalising their own emotional processes. For instance, a Year 3 teacher might say, "I'm feeling frustrated because the projector isn't working, but I'm going to take three deep breaths and ask for help rather than getting angry." This demonstrates emotional recognition, regulation strategies, and appropriate help-seeking behaviour in real-time.

Implementing daily emotion check-ins creates systematic opportunities for pupils to develop emotional vocabulary and self-awareness. Primary teachers can use emotion wheels or feeling thermometers during morning registration, whilst secondary teachers might incorporate brief mindfulness moments at lesson starts. The key is consistency and scaffolding - beginning with basic emotions (happy, sad, angry, worried) in early years and progressively introducing more nuanced emotional states (frustrated, overwhelmed, determined, apprehensive) as pupils mature.

Circle time and restorative practices provide structured forums for developing empathy and social skills. During these sessions, teachers can use scenario-based discussions where pupils explore different perspectives: "How might Jamie have felt when his work was knocked over?" or "What could we do differently next time?" These conversations, particularly when linked to real classroom incidents, help pupils understand the connection between actions, emotions, and consequences.

For secondary pupils, emotion journals and reflection activities encourage deeper self-analysis. Teachers can provide prompts such as "Describe a challenging moment today and the emotions you experienced" or "What strategies helped you manage stress during the assessment?" This approach aligns with PSHE curriculum objectives around self-awareness and emotional wellbeing, whilst building metacognitive skills that enhance both emotional and academic learning.

Teacher emotional intelligence significantly impacts classroom climate and pupil outcomes more than many educators realise. Research consistently shows that teachers with higher EI create more positive learning environments, experience less burnout, and achieve better pupil engagement. When teachers demonstrate emotional awareness and regulation, they model these skills for their pupils whilst creating the psychological safety necessary for effective learning. A teacher who can recognise their own stress signals and respond calmly to challenging behaviour teaches pupils far more about emotional regulation than any worksheet or poster ever could.

The emotional contagion effect means that teacher emotions directly influence classroom atmosphere. A teacher's anxiety about an Ofsted inspection or frustration with workload can unconsciously transfer to pupils, creating tension and reducing learning effectiveness. Conversely, teachers who maintain emotional equilibrium help pupils feel secure and ready to take learning risks. This is particularly crucial when working with vulnerable pupils or those with special educational needs, who may be more sensitive to adult emotional states and require additional emotional scaffolding.

In behaviour management, emotionally intelligent teachers distinguish between the pupil and the behaviour, responding to underlying emotional needs rather than simply addressing surface-level disruption. For example, recognising that a pupil's aggressive outburst might stem from anxiety about home circumstances allows for a more compassionate and effective response. This approach aligns with trauma-informed practice and helps build the positive relationships that underpin effective classroom management.

Furthermore, teacher EI directly supports professional development and collaboration. Emotionally intelligent teachers navigate staff meetings more effectively, build stronger partnerships with parents, and contribute to positive whole-school culture. They're better equipped to give and receive feedback, manage the emotional demands of the profession, and maintain the resilience necessary for long-term career success. This professional emotional competence ultimately benefits pupils through more stable, effective teaching relationships.

Assessing emotional intelligence requires observational and qualitative approaches rather than traditional testing methods. The most effective assessment strategy involves systematic observation of pupils' emotional responses and social interactions across different contexts. Teachers can use simple observation frameworks that track specific behaviours: How does the child respond to frustration during independent work? Can they identify their emotional state when asked? Do they show empathy when classmates are upset? These observations, recorded regularly, provide meaningful insight into emotional development over time.

Self-reflection tools adapted for different age groups offer valuable assessment data whilst promoting self-awareness. Primary pupils might complete simple emotion tracking sheets with pictures and basic questions: "How did I feel when..?" or "What helped me feel better today?" Secondary pupils can engage with more sophisticated reflection frameworks, including emotional intelligence self-assessment questionnaires that explore their perceived competence in areas such as emotion recognition, empathy, and relationship management. These tools should be used formatively rather than for high-stakes evaluation.

The importance of contextual assessment cannot be overstated when evaluating emotional intelligence. A pupil might demonstrate excellent emotional regulation during structured lessons but struggle during unstructured break times, or show strong empathy with peers but difficulty managing emotions when frustrated by academic challenges. Teachers need to observe across multiple settings and situations, considering factors such as cultural background, developmental stage, and individual circumstances that might influence emotional expression and regulation.

Linking EI assessment to broader personal development frameworks ensures systematic tracking and supports Ofsted requirements for monitoring pupils' personal development. Many schools incorporate emotional intelligence indicators into their PSHE assessment or personal development tracking systems. This might include progression statements such as "can identify basic emotions in self and others" progressing to "can explain the impact of emotions on behaviour and suggest appropriate responses." Regular pupil voice activities, peer feedback opportunities, and family input also provide valuable assessment information whilst reinforcing the collaborative nature of emotional intelligence development.

The Zones of Regulation is a cognitive-behavioural framework that helps students recognise and name emotional states through four colour-coded 'zones': Blue (low energy), Green (ready to learn), Yellow (heightened emotions), and Red (intense emotions). With over 300,000 copies sold and implementation across 40+ countries, this approach provides practical strategies for emotional self-regulation.

Students learn to identify which zone they are in at any given moment and select appropriate strategies to maintain or change their emotional state. The Blue Zone represents low energy states (tired, sad, bored), the Green Zone indicates optimal learning readiness (calm, focused, happy), the Yellow Zone signals heightened alertness (frustrated, anxious, excited), and the Red Zone involves intense emotions (angry, terrified, elated, out of control). Crucially, no zone is inherently good or bad; all emotions serve valid purposes.

Teachers implement the Zones through daily check-ins where students identify their current zone through journals, cards, or verbal sharing. This routine builds emotional vocabulary and self-awareness. Classroom displays show the four zones with associated feelings and strategies, creating shared language for discussing emotions. When a teacher says, 'I notice you're in the Yellow Zone; would a movement break help?', students understand immediately rather than feeling judged or misunderstood.

Calm-down corners provide dedicated spaces where students can access regulation tools: fidget items, breathing exercise cards, noise-cancelling headphones, or weighted lap pads. These spaces normalise emotional regulation as necessary skill practice rather than punishment. Students learn which strategies work best for them personally, developing meta-cognitive awareness about their own emotional patterns. Research shows schools implementing the Zones consistently report reduced office referrals, increased student mindfulness, and improved academic scores.

The framework supports both individual regulation and co-regulation, where adults help students manage emotions. Teachers model by naming their own zones ('I'm feeling Yellow right now because we have a tight deadline'), validating students' feelings ('It's okay to be in the Red Zone; I'm here with you'), and offering tools ('Let's take some deep breaths together'). This co-regulation builds trust and teaches students that emotional support is available, gradually enabling independent regulation as skills develop.

Daniel Goleman's model identifies five key emotional intelligence components: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills. Research suggests emotional intelligence proves twice as important as cognitive intelligence for predicting career success, with particular relevance for teachers and school leaders managing complex interpersonal dynamics daily.

Self-awareness, the foundation of emotional intelligence, involves recognising and understanding one's own emotions, strengths, weaknesses, and motivations. Teachers with strong self-awareness notice when frustration builds during challenging lessons, recognise personal triggers, and understand how their emotional state affects students. They can distinguish between reasonable responses and reactions driven by stress, tiredness, or personal issues. This awareness allows intentional choice rather than automatic reaction when faced with transformative behaviour or difficult conversations.

Self-regulation enables controlling and managing emotions effectively. Teachers face constant emotional demands: managing disappointment when lessons fail, staying calm during conflicts, responding patiently to repeated questions, and maintaining enthusiasm despite fatigue. Self-regulation does not mean suppressing emotions but rather expressing them appropriately. A self-regulated teacher might feel angry about a student's behaviour but chooses to address it calmly after taking a brief pause rather than reacting immediately with raised voice.

Motivation in Goleman's model refers to intrinsic drive beyond external rewards. Teachers motivated by genuine passion for helping students learn demonstrate sustained energy, resilience through setbacks, and clear decision-making aligned with educational purposes. This intrinsic motivation proves particularly crucial during challenging periods when external validation is scarce. Students sense authentic passion, responding with greater engagement than to teachers merely going through motions.

Empathy, the ability to understand and share others' feelings, enhances all teaching relationships. Empathetic teachers consider what lies behind misbehaviour (Is the student hungry? Struggling at home? Feeling overwhelmed?), recognise when quiet students need extra support, and respond to cultural differences with curiosity rather than judgment. This component proves vital for inclusive practice, as it enables teachers to perceive learning barriers students face and adjust accordingly. Research consistently links teacher empathy to improved student outcomes across academic and social-emotional domains.

Social skills encompass effective communication, conflict resolution, collaboration, and relationship-building. Teachers with strong social skills build rapport quickly, navigate difficult conversations with parents, work productively with colleagues despite differences, and create classroom communities where students feel valued. These skills extend beyond pleasantness; they involve strategic relationship management that advances educational goals. Importantly, Goleman emphasises that unlike IQ, emotional intelligence can be learned and developed, making these components accessible teaching priorities rather than fixed personality traits.

Social-emotional learning integration does not require separate curriculum time; instead, effective SEL weaves emotional skill development into existing academic content through thoughtful instructional design. Meta-analysis of 213 rigorous studies found students receiving quality SEL programming demonstrated 11 percentile point gains in achievement, with effects lasting up to 18 years after programme completion.

Literature lessons provide natural opportunities for exploring emotions and perspectives. When discussing characters' motivations, teachers develop empathy and perspective-taking. Questions such as 'How might this character feel?', 'Why did they make that choice?', 'What would you have done differently?' prompt emotional reasoning. Students can create emotion timelines tracking characters' feelings throughout stories, identify moments when characters demonstrated self-regulation or poor emotional choices, and discuss how emotional decisions shaped plot outcomes. This approach simultaneously builds literary analysis skills and emotional intelligence.

History and social studies naturally address social awareness and relationship skills. Studying historical conflicts, teachers can prompt students to consider multiple perspectives, analyse how emotions influenced decisions, and discuss communication breakdowns that escalated tensions. Current events lessons provide opportunities for practising civil discourse about disagreements, recognising bias, and considering how social identities shape experiences. These discussions develop critical thinking alongside social-emotional competencies.

Mathematics offers opportunities for self-management and growth mindset development. When students struggle with problems, teachers can prompt reflection on frustration management: 'What strategy can you try when stuck?', 'How can you break this into smaller steps?', 'Who could you ask for help?'. Celebrating perseverance and problem-solving processes rather than only correct answers develops motivation and resilience. Group problem-solving activities build collaboration skills as students negotiate approaches, explain reasoning, and resolve disagreements about methods.

Science investigations develop self-management through procedures requiring careful attention, patience, and error analysis. When experiments fail, teachers can frame these as learning opportunities, prompting students to regulate disappointment, analyse what went wrong, and try again with modifications. Collaborative investigations require negotiation, role assignment, and conflict resolution. Science discussions about ethical issues (climate change, medical research, technology impacts) develop social awareness and responsible decision-making.

Physical education provides particularly rich SEL opportunities through teamwork, competition management, and physical regulation skills. Teachers can explicitly connect physical sensations to emotions (noticing racing heart, tight muscles, shallow breathing when anxious) and teach calming strategies. Competitive situations offer practice managing winning graciously and losing with dignity. Team activities develop communication, cooperation, and conflict resolution under pressure, with immediate feedback about what works and what does not.

Emotional intelligence development accelerates when schools and families use consistent language and strategies across environments. Teachers who partner with families through regular communication about SEL curriculum, shared tools and resources, and collaborative problem-solving create coherent support systems rather than fragmented efforts.

Begin family partnerships by explaining the purpose and components of your SEL approach early in the year. Share the emotional vocabulary you use (whether Zones colours, feeling words charts, or Goleman's components) through newsletters, parent meetings, or orientation sessions. Provide families with the same visual resources used in class so home environments mirror school language. When students hear consistent terminology about emotions and regulation across settings, concepts consolidate more quickly.

Offer practical strategies families can implement at home. Share regulation techniques students are learning (breathing exercises, counting strategies, movement breaks) with guidance about when and how to use them. Provide conversation starters for discussing emotions at dinner or bedtime: 'What zone were you in today?', 'When did you feel proud of yourself?', 'What was challenging emotionally?'. These routines normalise emotional discussion and provide low-pressure practice identifying feelings.

Communicate regularly about specific emotional challenges students face and coordinate responses. When a student struggles with frustration during homework, collaborate with families about breaking tasks into smaller chunks, taking breaks, and celebrating effort. When anxiety about tests emerges, share calming strategies school uses and discuss how families can support practice at home. This coordination prevents mixed messages and reinforces that emotional skills matter in all contexts.

Invite families to model emotional intelligence themselves. Share research about how children learn emotional skills primarily through observation, encouraging parents to name their own feelings, demonstrate self-regulation when frustrated, show empathy in family interactions, and repair relationships after conflicts. Some teachers send home 'family SEL challenges' suggesting activities such as practising gratitude together, doing random acts of kindness, or having screen-free conversation time.

Recognise cultural differences in emotional expression and socialisation. Different cultures hold varying norms about which emotions to express, how openly to discuss feelings, and what emotional skills to prioritise. Invite families to share their values and practices, incorporating diverse perspectives into classroom discussions. This inclusion validates students' home experiences whilst broadening all students' understanding of emotional expression across cultures. When families feel their values are respected rather than contradicted, they become partners rather than sceptics in emotional learning efforts.

Emotional intelligence is not just a beneficial skill but a crucial component of a well-rounded education. By prioritising the development of self-awareness, self-management, social skills, and empathy, educators can equip students with the tools they need to navigate the complexities of social interactions, manage their emotions effectively, and build strong, positive relationships.

In the wake of the challenges posed by recent global events, emotional intelligence has become even more critical. As educators, it is our responsibility to create learning environments that nurture emotional growth and resilience, helping students to thrive both academically and personally. By embedding EI strategies into our teaching practices, we can creates a generation of compassionate, empathetic, and emotionally intelligent individuals who are well-prepared to contribute positively to society.

Emotional intelligence research

Emotional Intelligence (EI) is a facet of human ability that goes beyond cognitive intelligence and cognitive abilities. It encompasses the skills necessary to manage one's emotions, comprehend others' feelings, and navigate social relationships.

EI is pivotal in building stronger relationships and is particularly beneficial in difficult situations where interpersonal skills and active listening are key. It includes the ability to recognise one's own and others' emotions using tools like an emotion wheel(Emotion Recognition Ability), the capacity for active emotional understanding, and the aptitude to communicate affect effectively through nonverbal communication and movement and relationship play.

It's a set of emotional abilities that, when harnessed, can lead to improved job satisfaction and conflict management. Unlike the more static measure of IQ, EI skills can be developed and refined with practice and mindfulness. The essence of EI lies in four core competencies:

Through the cultivation of these competencies, individuals can achieve a harmony between heart and mind, ultimately enhancing both personal and professional spheres of life.

Post-Covid evidence indicates significantly more pupils now require mental health support, highlighting a significant decline in emotional wellbeing and resilience. The pandemic disrupted normal social development and created widespread anxiety that continues to impact classroom behaviour and learning. Students are displaying increased emotional dysregulation and reduced capacity to manage social relationships effectively.

If we consider the impact of the Covid pandemic, evidence suggests that children's and young people's mental well-being has been significantly impacted. For example, referrals for mental health support increased substantially during 2021 for children and young people's mental and physical health services compared with the same period in 2019.

A relationship can also be found between well-being and pupils' experiences of transformative social behaviour whilst at school, with students showing poorer happiness and anxiousness because of peers' classroom behaviour. (GOV 2021)

Between March and June 2020, a period when schools were closed to most pupils, symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder were found to have significantly increased in children and young people aged between 7.5 and 12 years old compared to immediately before the pandemic. The effects of lockdown and a decline in well-being can be seen in data collected across 2020 and 2021, showing students could concentrate very (25%) or quite (59%) well in lessons in their classroom (84% very/quite well), whilst 16% said they could not concentrate very or well at all. Further, 39% of pupils were very worried about catching up on their learning.

As a practitioner being able to use emotionally intelligent strategies with students by talking about experiences, developing confidence, and supporting them to develop mindfulness strategies has and can support a positive classroom experience. By September 2020, relative to the March to June 2020 lockdown, reported behavioural, attention, and emotional difficulties in children had returned to, and stabilized at, a lower level. (Gov 2021).

As a result of the pandemic, emotional intelligence, therefore, has never been more important as a tool in the practitioners' toolbox. As understanding a pupil's feelings and emotions and being empathetic can increase engagement and well-being.

The amygdala triggers fight-or-flight responses when students feel threatened, which can appear as emotional outbursts, particularly in neurodivergent pupils. Negative experiences create stronger neural pathways than positive ones, making fear-based memory more persistent and impactful on learning. Understanding these brain mechanisms helps teachers create emotionally safe learning environments that support both growth mindset and academic achievement through effective scaffolding techniques.

Students with special educational needs may require additional support to develop emotional regulation skills. Teachers can use effective questioning strategies to help students reflect on their emotional responses and develop better self-awareness. Providing regular feedback about emotional progress helps maintain motivation throughout the learning process. These approaches support active learning by creating emotionally safe environments where students feel supported to take intellectual risks., facilitating greater engagement and success in their educational journeys.

Implement emotion check-ins as regular activities using tools like the Zones of Regulation, conduct role-playing exercises that simulate real-world social situations, and encourage mindfulness through activities like deep breathing or visualisation. Encourage regular self-reflection through journaling.

To actively creates emotional intelligence, educators can employ several strategies:

By consistently implementing these strategies, teachers can create a classroom culture that values and supports emotional intelligence, ultimately enhancing student well-being and academic performance.

Teaching emotional intelligence requires intentional and structured approaches that move beyond incidental learning to explicit skill development. The most effective method is through emotion coaching, where teachers model emotional awareness by verbalising their own emotional processes. For instance, a Year 3 teacher might say, "I'm feeling frustrated because the projector isn't working, but I'm going to take three deep breaths and ask for help rather than getting angry." This demonstrates emotional recognition, regulation strategies, and appropriate help-seeking behaviour in real-time.

Implementing daily emotion check-ins creates systematic opportunities for pupils to develop emotional vocabulary and self-awareness. Primary teachers can use emotion wheels or feeling thermometers during morning registration, whilst secondary teachers might incorporate brief mindfulness moments at lesson starts. The key is consistency and scaffolding - beginning with basic emotions (happy, sad, angry, worried) in early years and progressively introducing more nuanced emotional states (frustrated, overwhelmed, determined, apprehensive) as pupils mature.

Circle time and restorative practices provide structured forums for developing empathy and social skills. During these sessions, teachers can use scenario-based discussions where pupils explore different perspectives: "How might Jamie have felt when his work was knocked over?" or "What could we do differently next time?" These conversations, particularly when linked to real classroom incidents, help pupils understand the connection between actions, emotions, and consequences.

For secondary pupils, emotion journals and reflection activities encourage deeper self-analysis. Teachers can provide prompts such as "Describe a challenging moment today and the emotions you experienced" or "What strategies helped you manage stress during the assessment?" This approach aligns with PSHE curriculum objectives around self-awareness and emotional wellbeing, whilst building metacognitive skills that enhance both emotional and academic learning.

Teacher emotional intelligence significantly impacts classroom climate and pupil outcomes more than many educators realise. Research consistently shows that teachers with higher EI create more positive learning environments, experience less burnout, and achieve better pupil engagement. When teachers demonstrate emotional awareness and regulation, they model these skills for their pupils whilst creating the psychological safety necessary for effective learning. A teacher who can recognise their own stress signals and respond calmly to challenging behaviour teaches pupils far more about emotional regulation than any worksheet or poster ever could.

The emotional contagion effect means that teacher emotions directly influence classroom atmosphere. A teacher's anxiety about an Ofsted inspection or frustration with workload can unconsciously transfer to pupils, creating tension and reducing learning effectiveness. Conversely, teachers who maintain emotional equilibrium help pupils feel secure and ready to take learning risks. This is particularly crucial when working with vulnerable pupils or those with special educational needs, who may be more sensitive to adult emotional states and require additional emotional scaffolding.

In behaviour management, emotionally intelligent teachers distinguish between the pupil and the behaviour, responding to underlying emotional needs rather than simply addressing surface-level disruption. For example, recognising that a pupil's aggressive outburst might stem from anxiety about home circumstances allows for a more compassionate and effective response. This approach aligns with trauma-informed practice and helps build the positive relationships that underpin effective classroom management.

Furthermore, teacher EI directly supports professional development and collaboration. Emotionally intelligent teachers navigate staff meetings more effectively, build stronger partnerships with parents, and contribute to positive whole-school culture. They're better equipped to give and receive feedback, manage the emotional demands of the profession, and maintain the resilience necessary for long-term career success. This professional emotional competence ultimately benefits pupils through more stable, effective teaching relationships.

Assessing emotional intelligence requires observational and qualitative approaches rather than traditional testing methods. The most effective assessment strategy involves systematic observation of pupils' emotional responses and social interactions across different contexts. Teachers can use simple observation frameworks that track specific behaviours: How does the child respond to frustration during independent work? Can they identify their emotional state when asked? Do they show empathy when classmates are upset? These observations, recorded regularly, provide meaningful insight into emotional development over time.

Self-reflection tools adapted for different age groups offer valuable assessment data whilst promoting self-awareness. Primary pupils might complete simple emotion tracking sheets with pictures and basic questions: "How did I feel when..?" or "What helped me feel better today?" Secondary pupils can engage with more sophisticated reflection frameworks, including emotional intelligence self-assessment questionnaires that explore their perceived competence in areas such as emotion recognition, empathy, and relationship management. These tools should be used formatively rather than for high-stakes evaluation.

The importance of contextual assessment cannot be overstated when evaluating emotional intelligence. A pupil might demonstrate excellent emotional regulation during structured lessons but struggle during unstructured break times, or show strong empathy with peers but difficulty managing emotions when frustrated by academic challenges. Teachers need to observe across multiple settings and situations, considering factors such as cultural background, developmental stage, and individual circumstances that might influence emotional expression and regulation.

Linking EI assessment to broader personal development frameworks ensures systematic tracking and supports Ofsted requirements for monitoring pupils' personal development. Many schools incorporate emotional intelligence indicators into their PSHE assessment or personal development tracking systems. This might include progression statements such as "can identify basic emotions in self and others" progressing to "can explain the impact of emotions on behaviour and suggest appropriate responses." Regular pupil voice activities, peer feedback opportunities, and family input also provide valuable assessment information whilst reinforcing the collaborative nature of emotional intelligence development.

The Zones of Regulation is a cognitive-behavioural framework that helps students recognise and name emotional states through four colour-coded 'zones': Blue (low energy), Green (ready to learn), Yellow (heightened emotions), and Red (intense emotions). With over 300,000 copies sold and implementation across 40+ countries, this approach provides practical strategies for emotional self-regulation.

Students learn to identify which zone they are in at any given moment and select appropriate strategies to maintain or change their emotional state. The Blue Zone represents low energy states (tired, sad, bored), the Green Zone indicates optimal learning readiness (calm, focused, happy), the Yellow Zone signals heightened alertness (frustrated, anxious, excited), and the Red Zone involves intense emotions (angry, terrified, elated, out of control). Crucially, no zone is inherently good or bad; all emotions serve valid purposes.

Teachers implement the Zones through daily check-ins where students identify their current zone through journals, cards, or verbal sharing. This routine builds emotional vocabulary and self-awareness. Classroom displays show the four zones with associated feelings and strategies, creating shared language for discussing emotions. When a teacher says, 'I notice you're in the Yellow Zone; would a movement break help?', students understand immediately rather than feeling judged or misunderstood.

Calm-down corners provide dedicated spaces where students can access regulation tools: fidget items, breathing exercise cards, noise-cancelling headphones, or weighted lap pads. These spaces normalise emotional regulation as necessary skill practice rather than punishment. Students learn which strategies work best for them personally, developing meta-cognitive awareness about their own emotional patterns. Research shows schools implementing the Zones consistently report reduced office referrals, increased student mindfulness, and improved academic scores.

The framework supports both individual regulation and co-regulation, where adults help students manage emotions. Teachers model by naming their own zones ('I'm feeling Yellow right now because we have a tight deadline'), validating students' feelings ('It's okay to be in the Red Zone; I'm here with you'), and offering tools ('Let's take some deep breaths together'). This co-regulation builds trust and teaches students that emotional support is available, gradually enabling independent regulation as skills develop.

Daniel Goleman's model identifies five key emotional intelligence components: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills. Research suggests emotional intelligence proves twice as important as cognitive intelligence for predicting career success, with particular relevance for teachers and school leaders managing complex interpersonal dynamics daily.

Self-awareness, the foundation of emotional intelligence, involves recognising and understanding one's own emotions, strengths, weaknesses, and motivations. Teachers with strong self-awareness notice when frustration builds during challenging lessons, recognise personal triggers, and understand how their emotional state affects students. They can distinguish between reasonable responses and reactions driven by stress, tiredness, or personal issues. This awareness allows intentional choice rather than automatic reaction when faced with transformative behaviour or difficult conversations.

Self-regulation enables controlling and managing emotions effectively. Teachers face constant emotional demands: managing disappointment when lessons fail, staying calm during conflicts, responding patiently to repeated questions, and maintaining enthusiasm despite fatigue. Self-regulation does not mean suppressing emotions but rather expressing them appropriately. A self-regulated teacher might feel angry about a student's behaviour but chooses to address it calmly after taking a brief pause rather than reacting immediately with raised voice.

Motivation in Goleman's model refers to intrinsic drive beyond external rewards. Teachers motivated by genuine passion for helping students learn demonstrate sustained energy, resilience through setbacks, and clear decision-making aligned with educational purposes. This intrinsic motivation proves particularly crucial during challenging periods when external validation is scarce. Students sense authentic passion, responding with greater engagement than to teachers merely going through motions.

Empathy, the ability to understand and share others' feelings, enhances all teaching relationships. Empathetic teachers consider what lies behind misbehaviour (Is the student hungry? Struggling at home? Feeling overwhelmed?), recognise when quiet students need extra support, and respond to cultural differences with curiosity rather than judgment. This component proves vital for inclusive practice, as it enables teachers to perceive learning barriers students face and adjust accordingly. Research consistently links teacher empathy to improved student outcomes across academic and social-emotional domains.

Social skills encompass effective communication, conflict resolution, collaboration, and relationship-building. Teachers with strong social skills build rapport quickly, navigate difficult conversations with parents, work productively with colleagues despite differences, and create classroom communities where students feel valued. These skills extend beyond pleasantness; they involve strategic relationship management that advances educational goals. Importantly, Goleman emphasises that unlike IQ, emotional intelligence can be learned and developed, making these components accessible teaching priorities rather than fixed personality traits.

Social-emotional learning integration does not require separate curriculum time; instead, effective SEL weaves emotional skill development into existing academic content through thoughtful instructional design. Meta-analysis of 213 rigorous studies found students receiving quality SEL programming demonstrated 11 percentile point gains in achievement, with effects lasting up to 18 years after programme completion.

Literature lessons provide natural opportunities for exploring emotions and perspectives. When discussing characters' motivations, teachers develop empathy and perspective-taking. Questions such as 'How might this character feel?', 'Why did they make that choice?', 'What would you have done differently?' prompt emotional reasoning. Students can create emotion timelines tracking characters' feelings throughout stories, identify moments when characters demonstrated self-regulation or poor emotional choices, and discuss how emotional decisions shaped plot outcomes. This approach simultaneously builds literary analysis skills and emotional intelligence.

History and social studies naturally address social awareness and relationship skills. Studying historical conflicts, teachers can prompt students to consider multiple perspectives, analyse how emotions influenced decisions, and discuss communication breakdowns that escalated tensions. Current events lessons provide opportunities for practising civil discourse about disagreements, recognising bias, and considering how social identities shape experiences. These discussions develop critical thinking alongside social-emotional competencies.

Mathematics offers opportunities for self-management and growth mindset development. When students struggle with problems, teachers can prompt reflection on frustration management: 'What strategy can you try when stuck?', 'How can you break this into smaller steps?', 'Who could you ask for help?'. Celebrating perseverance and problem-solving processes rather than only correct answers develops motivation and resilience. Group problem-solving activities build collaboration skills as students negotiate approaches, explain reasoning, and resolve disagreements about methods.

Science investigations develop self-management through procedures requiring careful attention, patience, and error analysis. When experiments fail, teachers can frame these as learning opportunities, prompting students to regulate disappointment, analyse what went wrong, and try again with modifications. Collaborative investigations require negotiation, role assignment, and conflict resolution. Science discussions about ethical issues (climate change, medical research, technology impacts) develop social awareness and responsible decision-making.

Physical education provides particularly rich SEL opportunities through teamwork, competition management, and physical regulation skills. Teachers can explicitly connect physical sensations to emotions (noticing racing heart, tight muscles, shallow breathing when anxious) and teach calming strategies. Competitive situations offer practice managing winning graciously and losing with dignity. Team activities develop communication, cooperation, and conflict resolution under pressure, with immediate feedback about what works and what does not.

Emotional intelligence development accelerates when schools and families use consistent language and strategies across environments. Teachers who partner with families through regular communication about SEL curriculum, shared tools and resources, and collaborative problem-solving create coherent support systems rather than fragmented efforts.

Begin family partnerships by explaining the purpose and components of your SEL approach early in the year. Share the emotional vocabulary you use (whether Zones colours, feeling words charts, or Goleman's components) through newsletters, parent meetings, or orientation sessions. Provide families with the same visual resources used in class so home environments mirror school language. When students hear consistent terminology about emotions and regulation across settings, concepts consolidate more quickly.

Offer practical strategies families can implement at home. Share regulation techniques students are learning (breathing exercises, counting strategies, movement breaks) with guidance about when and how to use them. Provide conversation starters for discussing emotions at dinner or bedtime: 'What zone were you in today?', 'When did you feel proud of yourself?', 'What was challenging emotionally?'. These routines normalise emotional discussion and provide low-pressure practice identifying feelings.

Communicate regularly about specific emotional challenges students face and coordinate responses. When a student struggles with frustration during homework, collaborate with families about breaking tasks into smaller chunks, taking breaks, and celebrating effort. When anxiety about tests emerges, share calming strategies school uses and discuss how families can support practice at home. This coordination prevents mixed messages and reinforces that emotional skills matter in all contexts.

Invite families to model emotional intelligence themselves. Share research about how children learn emotional skills primarily through observation, encouraging parents to name their own feelings, demonstrate self-regulation when frustrated, show empathy in family interactions, and repair relationships after conflicts. Some teachers send home 'family SEL challenges' suggesting activities such as practising gratitude together, doing random acts of kindness, or having screen-free conversation time.

Recognise cultural differences in emotional expression and socialisation. Different cultures hold varying norms about which emotions to express, how openly to discuss feelings, and what emotional skills to prioritise. Invite families to share their values and practices, incorporating diverse perspectives into classroom discussions. This inclusion validates students' home experiences whilst broadening all students' understanding of emotional expression across cultures. When families feel their values are respected rather than contradicted, they become partners rather than sceptics in emotional learning efforts.

Emotional intelligence is not just a beneficial skill but a crucial component of a well-rounded education. By prioritising the development of self-awareness, self-management, social skills, and empathy, educators can equip students with the tools they need to navigate the complexities of social interactions, manage their emotions effectively, and build strong, positive relationships.

In the wake of the challenges posed by recent global events, emotional intelligence has become even more critical. As educators, it is our responsibility to create learning environments that nurture emotional growth and resilience, helping students to thrive both academically and personally. By embedding EI strategies into our teaching practices, we can creates a generation of compassionate, empathetic, and emotionally intelligent individuals who are well-prepared to contribute positively to society.

Emotional intelligence research

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/emotional-intelligence#article","headline":" Developing emotional intelligence in the classroom","description":"Explore effective strategies for teachers to enhance student emotional intelligence, fostering empathy and social skills for success in and out of the...","datePublished":"2022-11-21T16:50:09.680Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/emotional-intelligence"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6952640033187119872e4c66_695263fe90d2e510250a97bd_emotional-intelligence-infographic.webp","wordCount":3998},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/emotional-intelligence#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":" Developing emotional intelligence in the classroom","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/emotional-intelligence"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/emotional-intelligence#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is emotional intelligence and why is it particularly important in classrooms today?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Emotional intelligence (EI) encompasses the skills necessary to manage one's emotions, comprehend others' feelings, and navigate social relationships through four core competencies: social skills, self-awareness, self-management, and empathy. Post-Covid evidence indicates significantly more pupils n"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How does the brain's emotional processing affect student behaviour, especially in neurodivergent learners?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The amygdala triggers fight-or-flight responses when students feel threatened, which can appear as emotional outbursts, particularly in neurodivergent pupils whose amygdala may respond to situations that others don't find threatening. Negative experiences create stronger neural pathways than positiv"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What practical strategies can teachers use to develop emotional intelligence in their students?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can implement 'safe to fail' techniques, scaffolding, and convey the message that students don't just have one attempt at task performance to create positive learning memories. Practitioners should talk about experiences with students, develop their confidence, and support them to develop m"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can understanding emotional intelligence help teachers manage classroom disruptions more effectively?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"By recognising that emotional outbursts often stem from the amygdala's fight-or-flight response rather than deliberate defiance, teachers can respond with empathy and appropriate support strategies like coaching and mentoring. Understanding that these displays of emotion often express frustrations a"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the four core competencies of emotional intelligence that teachers should focus on developing?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The four core competencies are: social skills (managing relationships and building networks), self-awareness (recognising emotional reactions and understanding their effects), self-management (regulating emotions and adapting to change), and empathy (understanding and sharing others' feelings). Thes"}}]}]}