Solomon Asch Theory

Solomon Asch's theory explores how group pressure shapes conformity, revealing the tension between truth, trust, and belonging.

Solomon Asch's theory explores how group pressure shapes conformity, revealing the tension between truth, trust, and belonging.

Solomon E. Asch is one of the most influential social psychologists whose theories have continued to shape the psychology landscape. Into the intricate studies that positioned Asch as a seminal figure in understanding the nuanced forces of peer pressure and the compelling sway of group dynamics.

Asch's experimental forays into conformity not only unveiled the often-unseen influence of the group over the individual but also how compliance weaves into the fabric of societal interactions. We will explore the depths of Asch's insights and examine the experiments that have significantly shaped the field's grasp on social behaviour. So, who exactly was Solomon Asch?

Key Insights

Solomon E. Asch, born on September 14, 1907, in Warsaw, Poland, would go on to become one of the most prominent psychologists of the 20th century, leaving an enduring legacy that continues to shape how we understand social behaviour today.

Asch was raised in a close-knit Jewish family that deeply valued education, intellectual exploration, and cultural tradition. His father, a merchant, and his mother, who managed the household, were both committed to giving their children the best opportunities possible, even amid the challenges of early 20th-century Europe. Books, spirited discussion, and an appreciation for learning were woven into the fabric of daily life, a foundation that would inspire Asch's lifelong dedication to scholarship.

In the early 1920s, seeking safety and greater possibility, the Asch family immigrated to the United States and settled in New York City. This move was transformative for young Solomon, exposing him to a vibrant mix of cultures, languages, and ideas that would later inform his fascination with conformity and group dynamics. Arriving as a teenager with limited English, Asch persevered, teaching himself the language by reading Charles Dickens novels alongside their Yiddish translations.

His early experiences of cultural adjustment and finding belonging in a new country may have planted the seeds for his later research into how social environments shape perception and behaviour. From these modest beginnings, he embarked on a remarkable academic journey that would take him to Swarthmore College, the Institute for Cognitive Studies, the University of Pennsylvania, and Rutgers University, institutions where he refined the theories that still resonate in psychology classrooms and research labs today.

Solomon Eliot Asch's intellectual journey began earnestly when he attended the City College of New York. His passion for understanding the intricacies of human cognition and behaviour led him to pursue further studies at Columbia University, where he was deeply influenced by the teachings of Max Wertheimer, a founder of Gestalt psychology.

Asch's commitment to academic excellence soon earned him a prestigious role as a professor of psychology at Brooklyn College. Here, Asch began to cultivate his interest in the phenomena of social conformity and normative influence.

His scholarly work caught the attention of the psychology department at Harvard University, where Asch continued to explore the powerful impact of social forces on individual judgment. Through meticulous research, Asch sought to unravel the complexities of social conformity, which he believed played a crucial role in everyday life, influencing the decisions and beliefs of individuals within a group setting.

An eminent psychologist, Asch's rigorous studies of independence in perception made significant contributions to the field of social psychology, particularly through his experiments that demonstrated the distortion of judgment under group pressure.

Solomon Asch's most groundbreaking contribution to psychology emerged through his ingeniously designed conformity experiments, conducted primarily in the 1950s. These studies would forever change our understanding of how social pressure influences individual judgment and decision-making.

The experimental design was deceptively simple yet profoundly revealing. Participants were asked to complete what they believed was a straightforward visual perception task: comparing the length of lines. Each participant was seated in a room with seven to nine other people, who were actually confederates (actors working with the researcher). The group was shown a standard line and then asked to identify which of three comparison lines matched its length.

The correct answer was always obvious, with differences between the lines clearly visible to anyone with normal vision. However, the confederates had been instructed to give incorrect answers on 12 of the 18 trials. The real participant, unaware of this deception, typically answered after hearing most of the group's responses.

The results were startling. In the control condition, where participants answered privately, less than 1% made errors. However, when faced with unanimous incorrect responses from the group, approximately 37% of participants conformed to the group's wrong answer at least once. Even more remarkably, about 75% of participants conformed on at least one trial during the experiment.

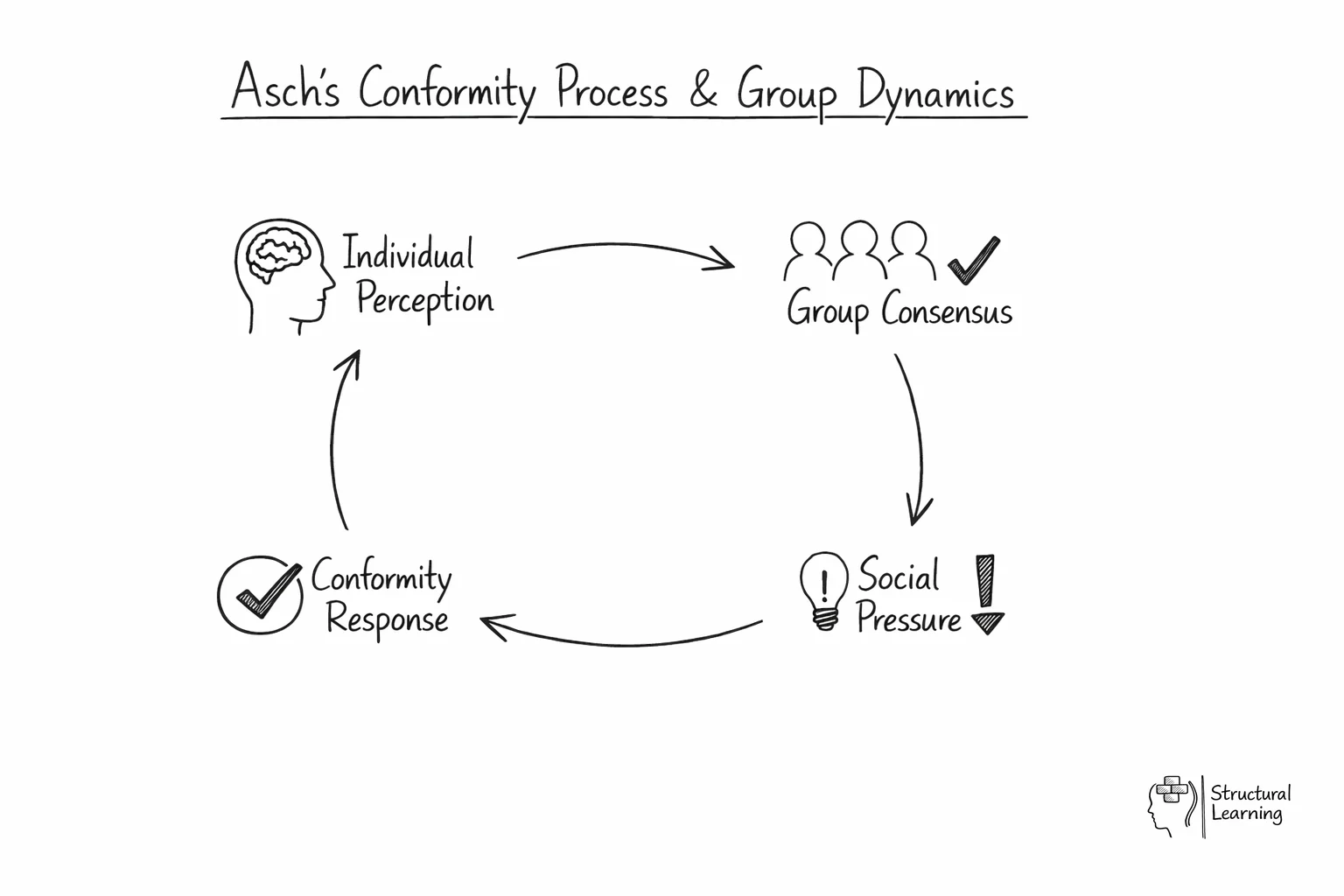

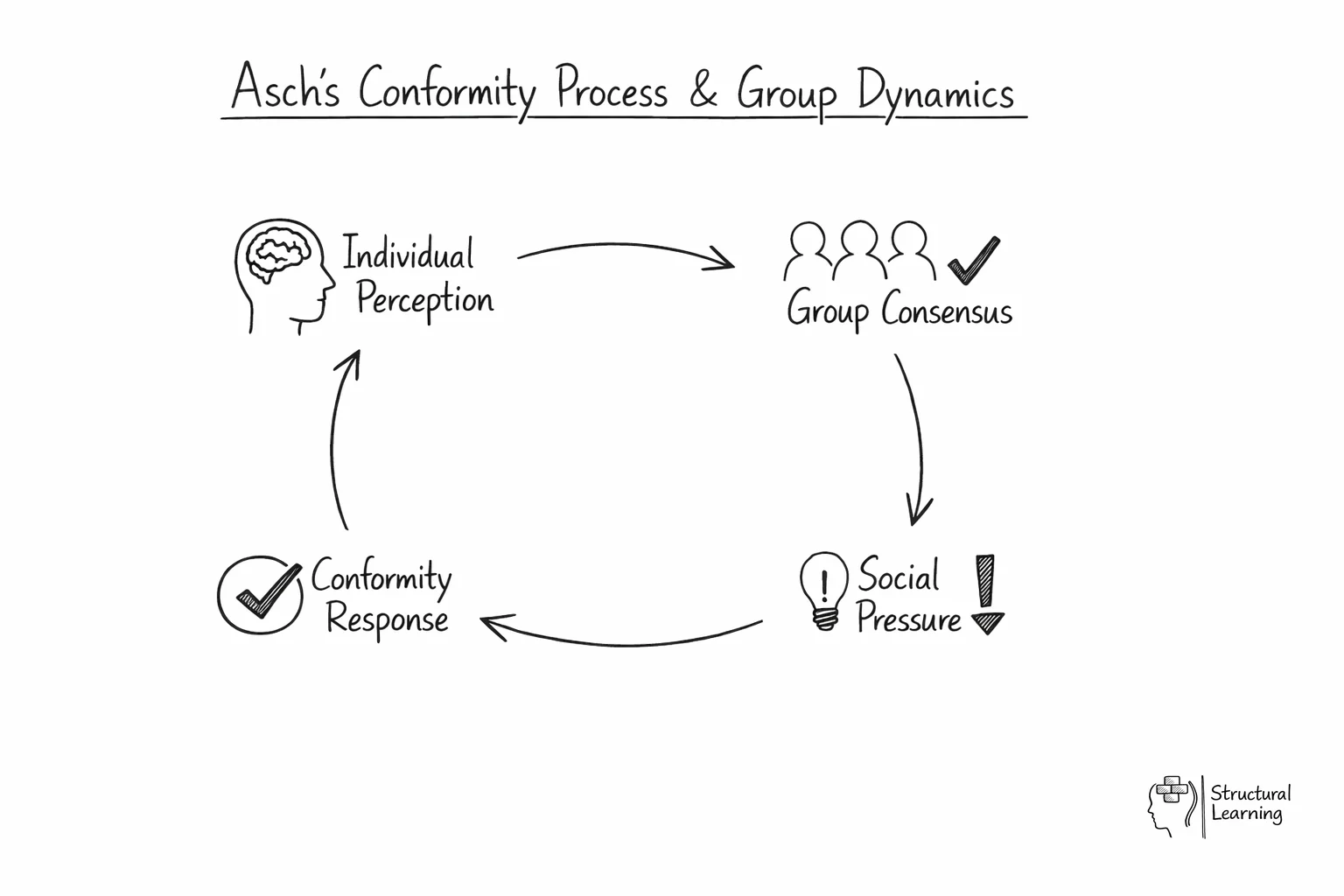

These findings revealed the profound impact of social pressure on individual perception and judgment. Asch's experiments demonstrated that people would deny the evidence of their own senses to avoid standing out from the group, highlighting the powerful psychological need for social acceptance and belonging.

Through variations of his original experiment, Asch identified several critical factors that influence the likelihood of conformity. Understanding these variables provides valuable insights for educators seeking to create learning environments that encourage independent thinking.

Group size proved to be a significant factor, though not in the way one might expect. Asch found that conformity rates increased as group size grew from one to three or four confederates, but beyond this point, additional group members had little impact. This suggests that a relatively small number of peers can exert substantial influence over an individual's decisions.

Unanimity emerged as perhaps the most crucial factor. When all confederates gave the same incorrect answer, conformity rates were highest. However, when just one confederate broke ranks and gave the correct answer, conformity dropped dramatically to about 5-10%. This finding highlights the powerful effect of having even a single ally who validates one's perceptions.

Task difficulty also played a role. When Asch made the line judgments more challenging by making the differences less obvious, conformity rates increased. This suggests that people are more likely to rely on others' opinions when they feel uncertain about their own judgment.

Individual differences in personality, cultural background, and self-confidence also influenced susceptibility to conformity. Participants with higher self-esteem and those from more individualistic cultural backgrounds showed greater resistance to group pressure.

Asch's findings have profound implications for classroom practice and educational design. Understanding conformity dynamics can help teachers create environments that creates genuine learning rather than mere compliance with group thinking.

One key application involves structuring group discussions to encourage diverse perspectives. Rather than allowing unanimous opinions to develop unchallenged, teachers can deliberately introduce alternative viewpoints or play devil's advocate to break the conformity effect. This approach helps students develop critical thinking skills and confidence in expressing dissenting views.

Assessment strategies can also benefit from Asch's insights. Anonymous voting systems or private reflection time before group discussions can help students form independent opinions before being influenced by peer responses. This mirrors Asch's control condition, where individual judgment remained largely accurate.

The classroom physical environment and seating arrangements can either promote or discourage conformity. Circle arrangements that make all students visible to each other may increase conformity pressure, while arrangements that allow for more privacy during initial thinking can support independent thought.

Teachers can also explicitly teach students about conformity pressures and help them develop strategies for maintaining independent thinking. This metacognitive awareness can serve as a protective factor against unwanted social influence whilst st ill allowing students to benefit from collaborative learning experiences.

Asch's conformity research remains strikingly relevant in today's educational landscape, particularly as digital technologies and social media create new forms of peer pressure and conformity. Modern classrooms must navigate both traditional face-to-face group dynamics and virtual learning environments where conformity pressures can be equally powerful.

In online learning contexts, the phenomenon of 'digital conformity' mirrors many of Asch's original findings. Students may conform to prevailing opinions in discussion forums or collaborative platforms, particularly when they can see others' responses before contributing their own thoughts. Understanding these dynamics helps educators design digital learning experiences that promote authentic engagement rather than mere echo chambers.

The research also illuminates important considerations for inclusive education. Students from minority backgrounds or those with diverse perspectives may face additional conformity pressures to fit in with mainstream classroom culture. Asch's findings about the power of even one dissenting voice highlight the importance of creating space for multiple perspectives and ensuring that all students feel safe to express their authentic thoughts and experiences.

Beyond the classroom, Asch's work provides a foundation for understanding broader educational phenomena such as academic dishonesty, peer pressure around achievement, and the development of school cultures. Schools that understand conformity dynamics can better address issues like cheating scandals, bullying, and the creation of positive learning communities that celebrate both collaboration and independent thinking.

Solomon Asch's pioneering research into conformity has provided educators with invaluable insights into the subtle yet powerful forces that shape student behaviour and learning in group settings. His elegant experiments revealed the delicate balance between social cohesion and individual autonomy that exists in every classroom, offering practical guidance for creating learning environments that honour both collaborative learning and independent thinking.

The enduring relevance of Asch's work lies not only in its demonstration of conformity's power but also in its revelation of the conditions that promote intellectual courage and authentic learning. By understanding how group size, unanimity, and task difficulty influence conformity, educators can structure learning experiences that harness the benefits of peer interaction whilst protecting students' capacity for original thought and creative expression.

As we continue to navigate evolving educational landscapes, from traditional classrooms to digital learning environments, Asch's insights remain a crucial compass for maintaining the integrity of the learning process. His legacy reminds us that true education must cultivate both the social skills necessary for collaboration and the intellectual independence required for genuine understanding and innovation.

For educators interested in exploring Solomon Asch's work and its applications in greater depth, the following research papers and studies provide valuable insights:

These foundational texts provide educators with both theoretical grounding and practical strategies for applying Asch's insights in contemporary educational settings, helping to create learning environments that balance social connection with intellectual independence.

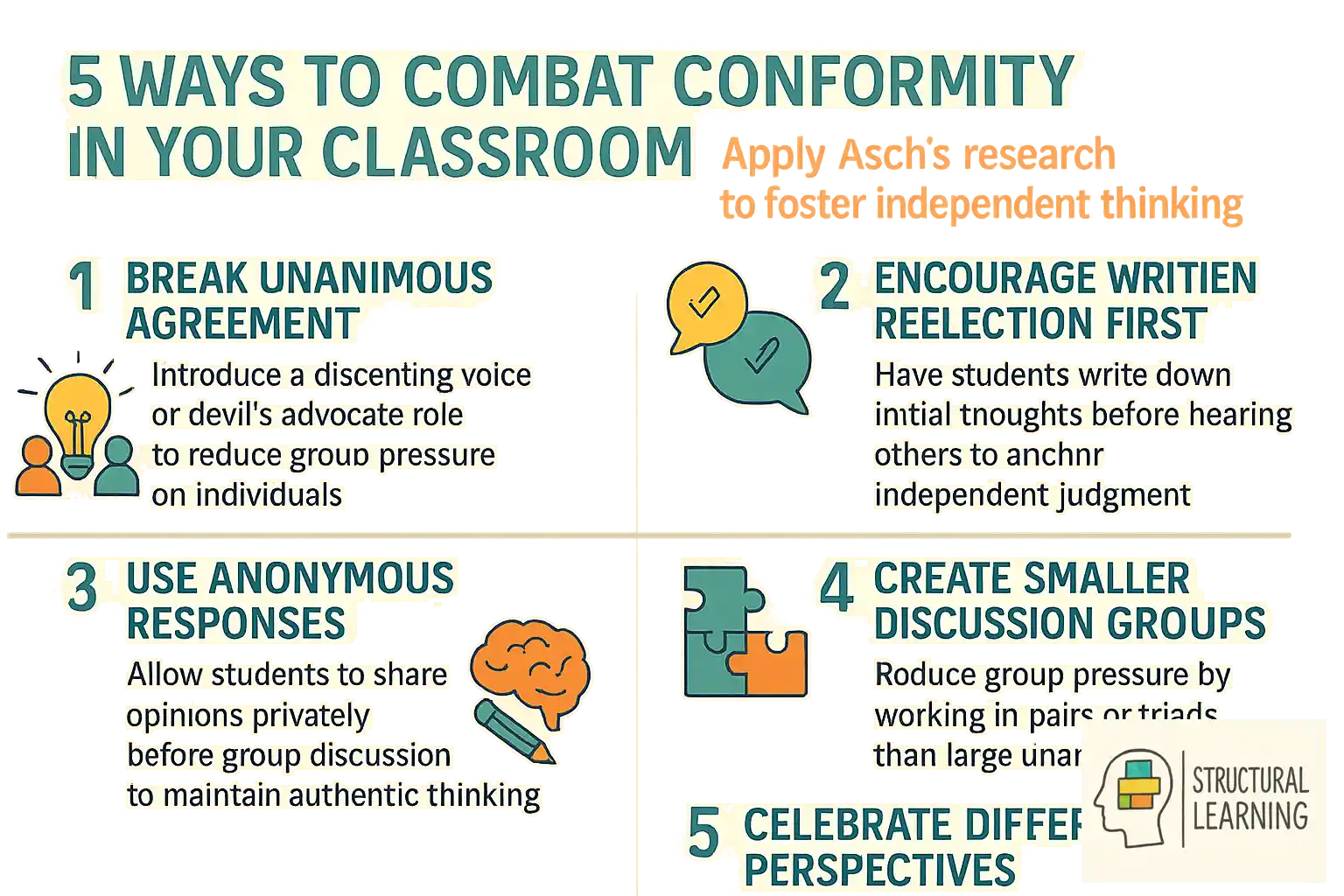

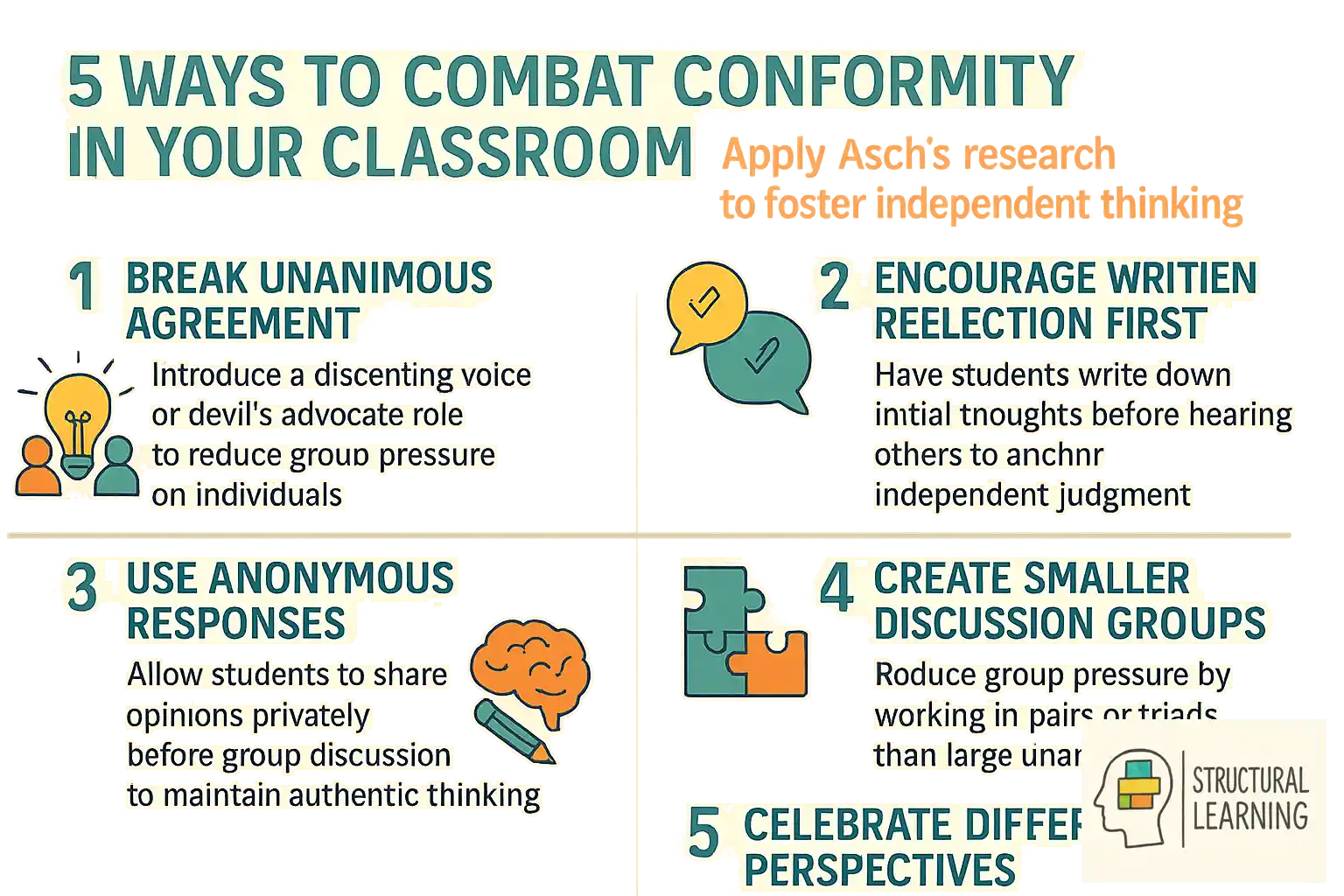

Building on Asch's research findings, educators can implement specific strategies to combat unhelpful conformity whilst maintaining the benefits of collaborative learning. These evidence-based approaches help create classroom environments where students feel confident to express genuine thoughts and engage in authentic intellectual exploration.

Anonymous Response Systems can be particularly effective in reducing conformity pressure. Using digital polling tools, index cards, or exit tickets allows students to share initial thoughts without fear of immediate peer judgment. This mirrors Asch's control conditions where individual accuracy remained high when responses were private.

Think-Pair-Share with a Twist modifies traditional collaborative structures by ensuring students have adequate individual thinking time before group discussion. By requiring written reflections before sharing, teachers can help students commit to their initial thoughts, making them less susceptible to immediate group influence.

Devil's Advocate Protocols deliberately introduce dissenting perspectives into group discussions. Teachers can assign rotating roles where students must argue alternative viewpoints, ensuring that unanimous consensus doesn't develop unchallenged. This strategy directly applies Asch's finding that even one dissenting voice dramatically reduces conformity.

Gallery Walks and Silent Discussions allow students to engage with multiple perspectives simultaneously rather than being influenced by the first few vocal responses. Students can move around the classroom, reading and responding to various prompts before verbal discussion begins, creating a richer foundation for authentic dialogue.

Metacognitive Reflection on Group Dynamics involves explicitly teaching students about conformity research and encouraging them to notice when they feel pressure to agree with others. This awareness-building approach helps students develop internal strategies for maintaining intellectual independence whilst still benefiting from peer collaboration.

Solomon E. Asch is one of the most influential social psychologists whose theories have continued to shape the psychology landscape. Into the intricate studies that positioned Asch as a seminal figure in understanding the nuanced forces of peer pressure and the compelling sway of group dynamics.

Asch's experimental forays into conformity not only unveiled the often-unseen influence of the group over the individual but also how compliance weaves into the fabric of societal interactions. We will explore the depths of Asch's insights and examine the experiments that have significantly shaped the field's grasp on social behaviour. So, who exactly was Solomon Asch?

Key Insights

Solomon E. Asch, born on September 14, 1907, in Warsaw, Poland, would go on to become one of the most prominent psychologists of the 20th century, leaving an enduring legacy that continues to shape how we understand social behaviour today.

Asch was raised in a close-knit Jewish family that deeply valued education, intellectual exploration, and cultural tradition. His father, a merchant, and his mother, who managed the household, were both committed to giving their children the best opportunities possible, even amid the challenges of early 20th-century Europe. Books, spirited discussion, and an appreciation for learning were woven into the fabric of daily life, a foundation that would inspire Asch's lifelong dedication to scholarship.

In the early 1920s, seeking safety and greater possibility, the Asch family immigrated to the United States and settled in New York City. This move was transformative for young Solomon, exposing him to a vibrant mix of cultures, languages, and ideas that would later inform his fascination with conformity and group dynamics. Arriving as a teenager with limited English, Asch persevered, teaching himself the language by reading Charles Dickens novels alongside their Yiddish translations.

His early experiences of cultural adjustment and finding belonging in a new country may have planted the seeds for his later research into how social environments shape perception and behaviour. From these modest beginnings, he embarked on a remarkable academic journey that would take him to Swarthmore College, the Institute for Cognitive Studies, the University of Pennsylvania, and Rutgers University, institutions where he refined the theories that still resonate in psychology classrooms and research labs today.

Solomon Eliot Asch's intellectual journey began earnestly when he attended the City College of New York. His passion for understanding the intricacies of human cognition and behaviour led him to pursue further studies at Columbia University, where he was deeply influenced by the teachings of Max Wertheimer, a founder of Gestalt psychology.

Asch's commitment to academic excellence soon earned him a prestigious role as a professor of psychology at Brooklyn College. Here, Asch began to cultivate his interest in the phenomena of social conformity and normative influence.

His scholarly work caught the attention of the psychology department at Harvard University, where Asch continued to explore the powerful impact of social forces on individual judgment. Through meticulous research, Asch sought to unravel the complexities of social conformity, which he believed played a crucial role in everyday life, influencing the decisions and beliefs of individuals within a group setting.

An eminent psychologist, Asch's rigorous studies of independence in perception made significant contributions to the field of social psychology, particularly through his experiments that demonstrated the distortion of judgment under group pressure.

Solomon Asch's most groundbreaking contribution to psychology emerged through his ingeniously designed conformity experiments, conducted primarily in the 1950s. These studies would forever change our understanding of how social pressure influences individual judgment and decision-making.

The experimental design was deceptively simple yet profoundly revealing. Participants were asked to complete what they believed was a straightforward visual perception task: comparing the length of lines. Each participant was seated in a room with seven to nine other people, who were actually confederates (actors working with the researcher). The group was shown a standard line and then asked to identify which of three comparison lines matched its length.

The correct answer was always obvious, with differences between the lines clearly visible to anyone with normal vision. However, the confederates had been instructed to give incorrect answers on 12 of the 18 trials. The real participant, unaware of this deception, typically answered after hearing most of the group's responses.

The results were startling. In the control condition, where participants answered privately, less than 1% made errors. However, when faced with unanimous incorrect responses from the group, approximately 37% of participants conformed to the group's wrong answer at least once. Even more remarkably, about 75% of participants conformed on at least one trial during the experiment.

These findings revealed the profound impact of social pressure on individual perception and judgment. Asch's experiments demonstrated that people would deny the evidence of their own senses to avoid standing out from the group, highlighting the powerful psychological need for social acceptance and belonging.

Through variations of his original experiment, Asch identified several critical factors that influence the likelihood of conformity. Understanding these variables provides valuable insights for educators seeking to create learning environments that encourage independent thinking.

Group size proved to be a significant factor, though not in the way one might expect. Asch found that conformity rates increased as group size grew from one to three or four confederates, but beyond this point, additional group members had little impact. This suggests that a relatively small number of peers can exert substantial influence over an individual's decisions.

Unanimity emerged as perhaps the most crucial factor. When all confederates gave the same incorrect answer, conformity rates were highest. However, when just one confederate broke ranks and gave the correct answer, conformity dropped dramatically to about 5-10%. This finding highlights the powerful effect of having even a single ally who validates one's perceptions.

Task difficulty also played a role. When Asch made the line judgments more challenging by making the differences less obvious, conformity rates increased. This suggests that people are more likely to rely on others' opinions when they feel uncertain about their own judgment.

Individual differences in personality, cultural background, and self-confidence also influenced susceptibility to conformity. Participants with higher self-esteem and those from more individualistic cultural backgrounds showed greater resistance to group pressure.

Asch's findings have profound implications for classroom practice and educational design. Understanding conformity dynamics can help teachers create environments that creates genuine learning rather than mere compliance with group thinking.

One key application involves structuring group discussions to encourage diverse perspectives. Rather than allowing unanimous opinions to develop unchallenged, teachers can deliberately introduce alternative viewpoints or play devil's advocate to break the conformity effect. This approach helps students develop critical thinking skills and confidence in expressing dissenting views.

Assessment strategies can also benefit from Asch's insights. Anonymous voting systems or private reflection time before group discussions can help students form independent opinions before being influenced by peer responses. This mirrors Asch's control condition, where individual judgment remained largely accurate.

The classroom physical environment and seating arrangements can either promote or discourage conformity. Circle arrangements that make all students visible to each other may increase conformity pressure, while arrangements that allow for more privacy during initial thinking can support independent thought.

Teachers can also explicitly teach students about conformity pressures and help them develop strategies for maintaining independent thinking. This metacognitive awareness can serve as a protective factor against unwanted social influence whilst st ill allowing students to benefit from collaborative learning experiences.

Asch's conformity research remains strikingly relevant in today's educational landscape, particularly as digital technologies and social media create new forms of peer pressure and conformity. Modern classrooms must navigate both traditional face-to-face group dynamics and virtual learning environments where conformity pressures can be equally powerful.

In online learning contexts, the phenomenon of 'digital conformity' mirrors many of Asch's original findings. Students may conform to prevailing opinions in discussion forums or collaborative platforms, particularly when they can see others' responses before contributing their own thoughts. Understanding these dynamics helps educators design digital learning experiences that promote authentic engagement rather than mere echo chambers.

The research also illuminates important considerations for inclusive education. Students from minority backgrounds or those with diverse perspectives may face additional conformity pressures to fit in with mainstream classroom culture. Asch's findings about the power of even one dissenting voice highlight the importance of creating space for multiple perspectives and ensuring that all students feel safe to express their authentic thoughts and experiences.

Beyond the classroom, Asch's work provides a foundation for understanding broader educational phenomena such as academic dishonesty, peer pressure around achievement, and the development of school cultures. Schools that understand conformity dynamics can better address issues like cheating scandals, bullying, and the creation of positive learning communities that celebrate both collaboration and independent thinking.

Solomon Asch's pioneering research into conformity has provided educators with invaluable insights into the subtle yet powerful forces that shape student behaviour and learning in group settings. His elegant experiments revealed the delicate balance between social cohesion and individual autonomy that exists in every classroom, offering practical guidance for creating learning environments that honour both collaborative learning and independent thinking.

The enduring relevance of Asch's work lies not only in its demonstration of conformity's power but also in its revelation of the conditions that promote intellectual courage and authentic learning. By understanding how group size, unanimity, and task difficulty influence conformity, educators can structure learning experiences that harness the benefits of peer interaction whilst protecting students' capacity for original thought and creative expression.

As we continue to navigate evolving educational landscapes, from traditional classrooms to digital learning environments, Asch's insights remain a crucial compass for maintaining the integrity of the learning process. His legacy reminds us that true education must cultivate both the social skills necessary for collaboration and the intellectual independence required for genuine understanding and innovation.

For educators interested in exploring Solomon Asch's work and its applications in greater depth, the following research papers and studies provide valuable insights:

These foundational texts provide educators with both theoretical grounding and practical strategies for applying Asch's insights in contemporary educational settings, helping to create learning environments that balance social connection with intellectual independence.

Building on Asch's research findings, educators can implement specific strategies to combat unhelpful conformity whilst maintaining the benefits of collaborative learning. These evidence-based approaches help create classroom environments where students feel confident to express genuine thoughts and engage in authentic intellectual exploration.

Anonymous Response Systems can be particularly effective in reducing conformity pressure. Using digital polling tools, index cards, or exit tickets allows students to share initial thoughts without fear of immediate peer judgment. This mirrors Asch's control conditions where individual accuracy remained high when responses were private.

Think-Pair-Share with a Twist modifies traditional collaborative structures by ensuring students have adequate individual thinking time before group discussion. By requiring written reflections before sharing, teachers can help students commit to their initial thoughts, making them less susceptible to immediate group influence.

Devil's Advocate Protocols deliberately introduce dissenting perspectives into group discussions. Teachers can assign rotating roles where students must argue alternative viewpoints, ensuring that unanimous consensus doesn't develop unchallenged. This strategy directly applies Asch's finding that even one dissenting voice dramatically reduces conformity.

Gallery Walks and Silent Discussions allow students to engage with multiple perspectives simultaneously rather than being influenced by the first few vocal responses. Students can move around the classroom, reading and responding to various prompts before verbal discussion begins, creating a richer foundation for authentic dialogue.

Metacognitive Reflection on Group Dynamics involves explicitly teaching students about conformity research and encouraging them to notice when they feel pressure to agree with others. This awareness-building approach helps students develop internal strategies for maintaining intellectual independence whilst still benefiting from peer collaboration.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/solomon-asch-theory#article","headline":"Solomon Asch Theory","description":"Solomon Asch's theory explores how group pressure shapes conformity, revealing the tension between truth, trust, and belonging.","datePublished":"2023-11-30T12:38:11.102Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/solomon-asch-theory"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/695035f25b99b9825ece912c_ktroz5.webp","wordCount":3375},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/solomon-asch-theory#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Solomon Asch Theory","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/solomon-asch-theory"}]}]}