Theories of Motivation

Explore the complex landscape of human motivation through key theories. Uncover how our needs, beliefs, and desires shape our behaviors.

Explore the complex landscape of human motivation through key theories. Uncover how our needs, beliefs, and desires shape our behaviors.

| Theory | Key Theorist | Core Principle | Classroom Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Determination | Deci & Ryan | Autonomy, competence, relatedness | Offer choices, optimal challenge |

| Achievement Goal | Dweck, Ames | Mastery vs performance goals | Focus on learning, not grades |

| Expectancy-Value | Eccles, Wigfield | Expectation × value = motivation | Build confidence and relevance |

| Attribution | Weiner | Causal beliefs affect motivation | Attribute success to effort |

| Flow | Csikszentmihalyi | Optimal challenge-skill balance | Match difficulty to ability |

The main theories of motivation in education include Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, Self- Determination Theory, Incentive Theory, Drive Theory, Expectancy Theory, and Achievement Motivation Theory. These frameworks explain different aspects of what drives student behaviour, from basic needs to intrinsic desires for competence and autonomy. Teachers use these theories to design engaging lessons and understand why students may struggle or excel in different situations.

Understanding the intricate dynamics of human behaviour and human motivation is a pivotal part of effective teaching. Diverse theories of motivation, each with its own unique perspectives, offer a variety of insights into what drives individuals to act, engage, and learn. In our exploration, we'll examine deep into these theories, shedding light on both the commonalities and distinctive elements that make each one unique.

Motivational theories provide comprehensive frameworks for understanding human behaviour, from simple daily habits to complex life decisions. These frameworks help explain why people pursue certain goals, how they respond to challenges, and what drives sustained effort over time

One notable example that illustrates the power of motivation is the impact of rewards on student engagement. As an educator, you might have noticed that when students are promised rewards for completing tasks, their participation often significantly increases. This is rooted in the Incentive Theory of Motivation, which postulates that rewards are potent motivators of behaviour.

As Albert Bandura, an eminent psychologist and motivational theorist, once remarked, "People not only gain understanding through reflection, they evaluate and alter their ownthinking." This introspective nature of motivation allows for an exciting dynamic wherein motivation is passively experienced and can be actively managed and enhanced.

However, remember that motivation can fuel not just positive but also negative behaviour. The Journal of Educational Psychology has highlighted instances where motivation, if misdirected, can lead to counterproductive outcomes such as cheating or avoidance. This underscores the need to understand and apply motivational theories judiciously to promote positive learning outcomes.

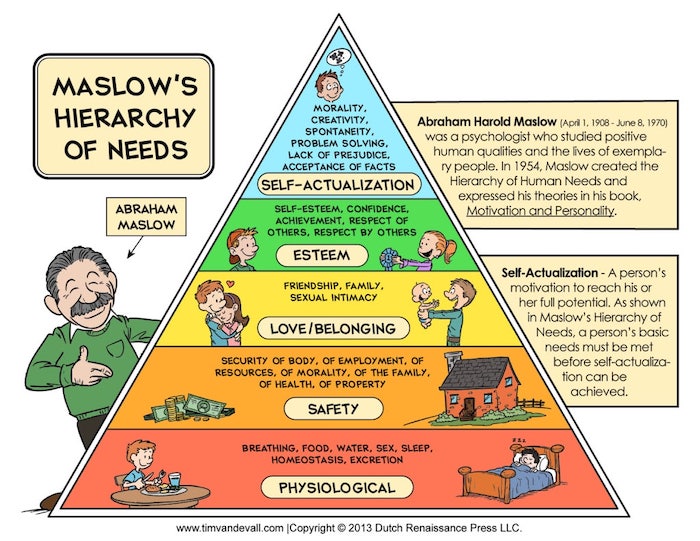

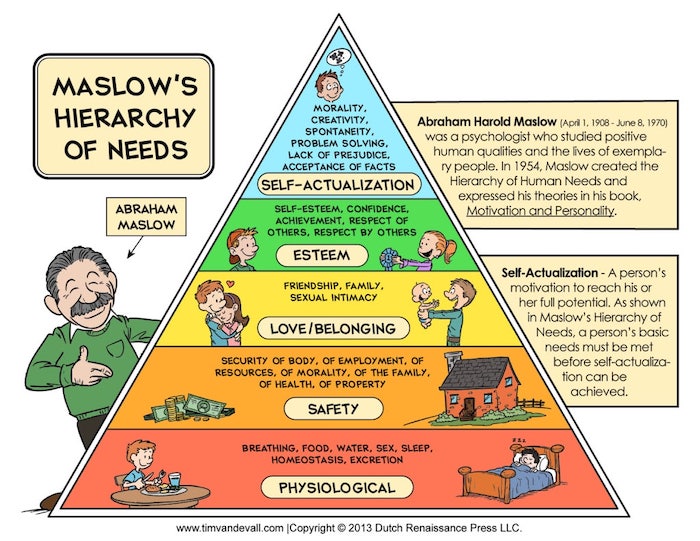

Maslow's hierarchy shows that students must have their basic physiological and safety needs met before they can focus on learning and self-actualization. When students are hungry, tired, or feel unsafe, their brains prioritise survival over academic achievement, making it nearly impossible to concentrate on lessons. Teachers can support learning by ensuring classroom environmentsfeel safe and by being aware of students' basic needs through programs like free breakfast or creating predictable routines.

Drawing from the point made earlier about the potential for motivated behaviours to incite both positive and negative actions, let's consider Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, a foundational theory in the motivational landscape. This theory, one of the earliest cognitive theories, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the wide array of human motivations.

Abraham Maslow proposed this hierarchy theory in the mid-20th century, postulating that human needs are organised in a pyramid-like structure. At the base of the pyramid are physiological needs like food and shelter, while at the apex, we find self-actualization needs, which relate to achieving one's full potential. The theory suggests that individuals must satisfy lower-level needs before they can address the needs higher up.

An interesting aspect of Maslow's theory is its explanation for the pattern of behaviour observed when certain needs are unmet. When a lower-level need isn't fulfiled, the individual's motivation to meet that need becomes predominant, often overshadowing other motivations.

This aspect aligns with our earlier discussion about motivation influencing both positive and negative behaviours.

Maslow's research consistently demonstrates that when basic physiological and safety needs remain unmet, individuals struggle to pursue higher-order goals like learning, belonging, or self-actualisation. This hierarchical relationship between needs remains one of the most influential frameworks in understanding human motivation.

This understanding of the hierarchy of needs underscores the complexity of motivation and the care we as educators must take to address and encourage it appropriately in our students.

Drive Theory suggests that student motivation stems from internal tensions or "drives" that create discomfort until satisfied. In education, this means students are motivated to learn when they experience curiosity gaps, knowledge deficits, or achievement tensions that require resolution. Teachers can harness Drive Theory by creating productive cognitive dissonance through challenging questions, knowledge gaps, and problems that students feel compelled to solve.

Drive Theory, originally developed by Clark Hull in the 1940s, offers a unique perspective on motivation that focuses on the concept of biological drives and psychological tensions. According to this theory, motivation arises from internal states of tension or imbalance that individuals feel compelled to reduce or eliminate.

The theory operates on a simple but powerful principle: when we experience a drive (such as hunger, thirst, or in educational contexts, curiosity or the need for competence), we're motivated to take action that will reduce that drive. This creates what Hull termed the "drive-reduction cycle," where tension leads to behaviour aimed at restoring balance.

In classroom settings, Drive Theory manifests in several fascinating ways. Students often experience cognitive drives when they encounter intriguing problems or knowledge gaps that create mental tension. This discomfort motivates them to seek information, ask questions, or persist with challenging tasks until the tension is resolved.

Research has shown that effective teachers can deliberately create productive drives by presenting students with puzzling phenomena, contradictory information, or challenging problems that generate curiosity. This approach aligns with what educational psychologists call "desirable difficulties" - challenges that initially create tension but ultimately enhance learning.

Self-Determination Theory identifies three basic psychological needs - autonomy, competence, and relatedness - that must be satisfied for students to develop intrinsic motivation. When students feel they have choice in their learning (autonomy), can master skills successfully (competence), and belong to their learning community (relatedness), they engage more deeply and persistently. This theory explains why student-centred approaches often outperform teacher-directed methods in promoting lasting motivation.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT), developed by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, represents one of the most influential contemporary approaches to understanding motivation in educational settings. This theory distinguishes between different types of motivation and identifies the conditions necessary for developing the most beneficial forms.

The theory's central premise is that humans have three innate psychological needs: autonomy (feeling volitional and self-directed), competence (experiencing mastery and effectiveness), and relatedness (connecting meaningfully with others). When these needs are satisfied, individuals naturally develop intrinsic motivation - the drive to engage in activities for their inherent satisfaction.

In classroom practice, SDT has profound implications for how teachers structure learning experiences. Research consistently shows that students demonstrate higher engagement, better academic outcomes, and increased well-being when their learning environments support these three basic needs.

Autonomy support might involve offering students choices in topics, methods, or pacing. Competence support includes providing optimal challenges, clear feedback, and scaffolding for success. Relatedness support encompasses creating inclusive classroom communities where students feel valued and connected to their peers and teachers.

Expectancy Theory explains student motivation through three key components: expectancy (belief they can succeed), instrumentality (belief that success leads to valued outcomes), and valence (how much they value those outcomes). Students are most motivated when they believe they can succeed, see clear connections between effort and rewards, and genuinely value what they're working towards. This theory helps teachers understand why some students disengage despite having ability.

Victor Vroom's Expectancy Theory provides a mathematical approach to understanding motivation, proposing that motivation is the product of three factors: expectancy, instrumentality, and valence. This cognitive approach treats individuals as rational decision-makers who weigh these factors when determining how much effort to invest.

Expectancy refers to an individual's belief about whether their effort will lead to successful performance. In educational contexts, this translates to students' confidence in their ability to master material or complete tasks successfully. Students with low expectancy beliefs often exhibit learned helplessness or avoidance behaviours.

Instrumentality represents the belief that good performance will lead to desired outcomes. Students need to see clear connections between their academic efforts and meaningful results, whether these are grades, learning goals, future opportunities, or personal satisfaction.

Valence concerns the value individuals place on potential outcomes. Even if students believe they can succeed and see the connection between effort and results, they won't be motivated unless they genuinely value what they're working towards.

Understanding Expectancy Theory helps teachers diagnose motivation problems more precisely. A student who isn't engaged might lack confidence (low expectancy), might not see how their work connects to meaningful outcomes (low instrumentality), or might not value the goals being pursued (low valence).

Achievement Motivation Theory focuses on students' need for achievement versus their fear of failure, suggesting that motivation depends on which drive is stronger. Students with high achievement motivation seek challenging tasks and persist through difficulties, while those with high fear of failure avoid risks and give up easily. Teachers can creates achievement motivation by celebrating effort over ability, providing appropriate challenges, and creating psychologically safe environments where failure is viewed as learning.

Achievement Motivation Theory, primarily developed by David McClelland and John Atkinson, examines the psychological factors that drive individuals to strive for success and excellence. This theory is particularly relevant in educational settings where students constantly face achievement-related decisions and challenges.

The theory identifies three key motives that influence behaviour: the need for achievement (nAch), the need for affiliation (nAff), and the need for power (nPow). In educational contexts, the need for achievement typically receives the most attention, as it directly relates to academic performance and learning outcomes.

Students with high achievement motivation demonstrate several characteristic behaviours: they prefer tasks of moderate difficulty that provide meaningful challenges without being overwhelming, they value feedback that helps them improve, and they tend to attribute success to their own efforts rather than external factors.

Conversely, students dominated by fear of failure often choose tasks that are either very easy (guaranteeing success) or impossibly difficult (where failure can be attributed to task difficulty rather than personal inadequacy). This pattern severely limits learning opportunities and academic growth.

Teachers can cultivate achievement motivation by establishing growth mindset environments where mistakes are treated as learning opportunities, providing tasks that offer optimal challenge levels, and helping students develop realistic goal-setting and self-evaluation skills.

Successfully applying motivation theories requires teachers to understand that different students may be driven by different factors at different times. A comprehensive approach involves creating classroom environments that address multiple motivational frameworks simultaneously.

For instance, teachers might begin by ensuring that Maslow's basic needs are met through consistent routines, safe learning spaces, and awareness of students' physical and emotional well-being. They can then incorporate Self-Determination Theory by offering meaningful choices, providing appropriate challenges that build competence, and developing positive relationships within the learning community.

Drive Theory can be harnessed through carefully crafted questions and problems that create productive cognitive tension, while Expectancy Theory suggests the importance of helping students build confidence, see clear pathways to success, and connect their learning to personally meaningful outcomes.

Achievement Motivation Theory reminds us to create environments where students feel safe to take intellectual risks, where effort is recognised alongside achievement, and where failure is reframed as an essential component of the learning process.

The most effective educational approaches often combine insights from multiple theories, recognising that motivation is complex and multifaceted. By understanding these various frameworks, teachers can develop more nuanced and effective strategies for engaging all students in meaningful learning.

Student motivation research

Motivation and learning

| Theory | Key Theorist | Core Principle | Classroom Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Determination | Deci & Ryan | Autonomy, competence, relatedness | Offer choices, optimal challenge |

| Achievement Goal | Dweck, Ames | Mastery vs performance goals | Focus on learning, not grades |

| Expectancy-Value | Eccles, Wigfield | Expectation × value = motivation | Build confidence and relevance |

| Attribution | Weiner | Causal beliefs affect motivation | Attribute success to effort |

| Flow | Csikszentmihalyi | Optimal challenge-skill balance | Match difficulty to ability |

The main theories of motivation in education include Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, Self- Determination Theory, Incentive Theory, Drive Theory, Expectancy Theory, and Achievement Motivation Theory. These frameworks explain different aspects of what drives student behaviour, from basic needs to intrinsic desires for competence and autonomy. Teachers use these theories to design engaging lessons and understand why students may struggle or excel in different situations.

Understanding the intricate dynamics of human behaviour and human motivation is a pivotal part of effective teaching. Diverse theories of motivation, each with its own unique perspectives, offer a variety of insights into what drives individuals to act, engage, and learn. In our exploration, we'll examine deep into these theories, shedding light on both the commonalities and distinctive elements that make each one unique.

Motivational theories provide comprehensive frameworks for understanding human behaviour, from simple daily habits to complex life decisions. These frameworks help explain why people pursue certain goals, how they respond to challenges, and what drives sustained effort over time

One notable example that illustrates the power of motivation is the impact of rewards on student engagement. As an educator, you might have noticed that when students are promised rewards for completing tasks, their participation often significantly increases. This is rooted in the Incentive Theory of Motivation, which postulates that rewards are potent motivators of behaviour.

As Albert Bandura, an eminent psychologist and motivational theorist, once remarked, "People not only gain understanding through reflection, they evaluate and alter their ownthinking." This introspective nature of motivation allows for an exciting dynamic wherein motivation is passively experienced and can be actively managed and enhanced.

However, remember that motivation can fuel not just positive but also negative behaviour. The Journal of Educational Psychology has highlighted instances where motivation, if misdirected, can lead to counterproductive outcomes such as cheating or avoidance. This underscores the need to understand and apply motivational theories judiciously to promote positive learning outcomes.

Maslow's hierarchy shows that students must have their basic physiological and safety needs met before they can focus on learning and self-actualization. When students are hungry, tired, or feel unsafe, their brains prioritise survival over academic achievement, making it nearly impossible to concentrate on lessons. Teachers can support learning by ensuring classroom environmentsfeel safe and by being aware of students' basic needs through programs like free breakfast or creating predictable routines.

Drawing from the point made earlier about the potential for motivated behaviours to incite both positive and negative actions, let's consider Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, a foundational theory in the motivational landscape. This theory, one of the earliest cognitive theories, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the wide array of human motivations.

Abraham Maslow proposed this hierarchy theory in the mid-20th century, postulating that human needs are organised in a pyramid-like structure. At the base of the pyramid are physiological needs like food and shelter, while at the apex, we find self-actualization needs, which relate to achieving one's full potential. The theory suggests that individuals must satisfy lower-level needs before they can address the needs higher up.

An interesting aspect of Maslow's theory is its explanation for the pattern of behaviour observed when certain needs are unmet. When a lower-level need isn't fulfiled, the individual's motivation to meet that need becomes predominant, often overshadowing other motivations.

This aspect aligns with our earlier discussion about motivation influencing both positive and negative behaviours.

Maslow's research consistently demonstrates that when basic physiological and safety needs remain unmet, individuals struggle to pursue higher-order goals like learning, belonging, or self-actualisation. This hierarchical relationship between needs remains one of the most influential frameworks in understanding human motivation.

This understanding of the hierarchy of needs underscores the complexity of motivation and the care we as educators must take to address and encourage it appropriately in our students.

Drive Theory suggests that student motivation stems from internal tensions or "drives" that create discomfort until satisfied. In education, this means students are motivated to learn when they experience curiosity gaps, knowledge deficits, or achievement tensions that require resolution. Teachers can harness Drive Theory by creating productive cognitive dissonance through challenging questions, knowledge gaps, and problems that students feel compelled to solve.

Drive Theory, originally developed by Clark Hull in the 1940s, offers a unique perspective on motivation that focuses on the concept of biological drives and psychological tensions. According to this theory, motivation arises from internal states of tension or imbalance that individuals feel compelled to reduce or eliminate.

The theory operates on a simple but powerful principle: when we experience a drive (such as hunger, thirst, or in educational contexts, curiosity or the need for competence), we're motivated to take action that will reduce that drive. This creates what Hull termed the "drive-reduction cycle," where tension leads to behaviour aimed at restoring balance.

In classroom settings, Drive Theory manifests in several fascinating ways. Students often experience cognitive drives when they encounter intriguing problems or knowledge gaps that create mental tension. This discomfort motivates them to seek information, ask questions, or persist with challenging tasks until the tension is resolved.

Research has shown that effective teachers can deliberately create productive drives by presenting students with puzzling phenomena, contradictory information, or challenging problems that generate curiosity. This approach aligns with what educational psychologists call "desirable difficulties" - challenges that initially create tension but ultimately enhance learning.

Self-Determination Theory identifies three basic psychological needs - autonomy, competence, and relatedness - that must be satisfied for students to develop intrinsic motivation. When students feel they have choice in their learning (autonomy), can master skills successfully (competence), and belong to their learning community (relatedness), they engage more deeply and persistently. This theory explains why student-centred approaches often outperform teacher-directed methods in promoting lasting motivation.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT), developed by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, represents one of the most influential contemporary approaches to understanding motivation in educational settings. This theory distinguishes between different types of motivation and identifies the conditions necessary for developing the most beneficial forms.

The theory's central premise is that humans have three innate psychological needs: autonomy (feeling volitional and self-directed), competence (experiencing mastery and effectiveness), and relatedness (connecting meaningfully with others). When these needs are satisfied, individuals naturally develop intrinsic motivation - the drive to engage in activities for their inherent satisfaction.

In classroom practice, SDT has profound implications for how teachers structure learning experiences. Research consistently shows that students demonstrate higher engagement, better academic outcomes, and increased well-being when their learning environments support these three basic needs.

Autonomy support might involve offering students choices in topics, methods, or pacing. Competence support includes providing optimal challenges, clear feedback, and scaffolding for success. Relatedness support encompasses creating inclusive classroom communities where students feel valued and connected to their peers and teachers.

Expectancy Theory explains student motivation through three key components: expectancy (belief they can succeed), instrumentality (belief that success leads to valued outcomes), and valence (how much they value those outcomes). Students are most motivated when they believe they can succeed, see clear connections between effort and rewards, and genuinely value what they're working towards. This theory helps teachers understand why some students disengage despite having ability.

Victor Vroom's Expectancy Theory provides a mathematical approach to understanding motivation, proposing that motivation is the product of three factors: expectancy, instrumentality, and valence. This cognitive approach treats individuals as rational decision-makers who weigh these factors when determining how much effort to invest.

Expectancy refers to an individual's belief about whether their effort will lead to successful performance. In educational contexts, this translates to students' confidence in their ability to master material or complete tasks successfully. Students with low expectancy beliefs often exhibit learned helplessness or avoidance behaviours.

Instrumentality represents the belief that good performance will lead to desired outcomes. Students need to see clear connections between their academic efforts and meaningful results, whether these are grades, learning goals, future opportunities, or personal satisfaction.

Valence concerns the value individuals place on potential outcomes. Even if students believe they can succeed and see the connection between effort and results, they won't be motivated unless they genuinely value what they're working towards.

Understanding Expectancy Theory helps teachers diagnose motivation problems more precisely. A student who isn't engaged might lack confidence (low expectancy), might not see how their work connects to meaningful outcomes (low instrumentality), or might not value the goals being pursued (low valence).

Achievement Motivation Theory focuses on students' need for achievement versus their fear of failure, suggesting that motivation depends on which drive is stronger. Students with high achievement motivation seek challenging tasks and persist through difficulties, while those with high fear of failure avoid risks and give up easily. Teachers can creates achievement motivation by celebrating effort over ability, providing appropriate challenges, and creating psychologically safe environments where failure is viewed as learning.

Achievement Motivation Theory, primarily developed by David McClelland and John Atkinson, examines the psychological factors that drive individuals to strive for success and excellence. This theory is particularly relevant in educational settings where students constantly face achievement-related decisions and challenges.

The theory identifies three key motives that influence behaviour: the need for achievement (nAch), the need for affiliation (nAff), and the need for power (nPow). In educational contexts, the need for achievement typically receives the most attention, as it directly relates to academic performance and learning outcomes.

Students with high achievement motivation demonstrate several characteristic behaviours: they prefer tasks of moderate difficulty that provide meaningful challenges without being overwhelming, they value feedback that helps them improve, and they tend to attribute success to their own efforts rather than external factors.

Conversely, students dominated by fear of failure often choose tasks that are either very easy (guaranteeing success) or impossibly difficult (where failure can be attributed to task difficulty rather than personal inadequacy). This pattern severely limits learning opportunities and academic growth.

Teachers can cultivate achievement motivation by establishing growth mindset environments where mistakes are treated as learning opportunities, providing tasks that offer optimal challenge levels, and helping students develop realistic goal-setting and self-evaluation skills.

Successfully applying motivation theories requires teachers to understand that different students may be driven by different factors at different times. A comprehensive approach involves creating classroom environments that address multiple motivational frameworks simultaneously.

For instance, teachers might begin by ensuring that Maslow's basic needs are met through consistent routines, safe learning spaces, and awareness of students' physical and emotional well-being. They can then incorporate Self-Determination Theory by offering meaningful choices, providing appropriate challenges that build competence, and developing positive relationships within the learning community.

Drive Theory can be harnessed through carefully crafted questions and problems that create productive cognitive tension, while Expectancy Theory suggests the importance of helping students build confidence, see clear pathways to success, and connect their learning to personally meaningful outcomes.

Achievement Motivation Theory reminds us to create environments where students feel safe to take intellectual risks, where effort is recognised alongside achievement, and where failure is reframed as an essential component of the learning process.

The most effective educational approaches often combine insights from multiple theories, recognising that motivation is complex and multifaceted. By understanding these various frameworks, teachers can develop more nuanced and effective strategies for engaging all students in meaningful learning.

Student motivation research

Motivation and learning

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/theories-of-motivation#article","headline":"Theories of Motivation","description":"Explore the complex landscape of human motivation through key theories. Uncover how our needs, beliefs, and desires shape our behaviors.","datePublished":"2023-05-09T10:18:57.902Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/theories-of-motivation"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6952551506d131adfe5028c4_69525511c5ec85309f5c7264_theories-of-motivation-infographic.webp","wordCount":3677},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/theories-of-motivation#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Theories of Motivation","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/theories-of-motivation"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"How Does Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Affect Student Learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Maslow's hierarchy shows that students must have their basic physiological and safety needs met before they can focus on learning and self-actualization. When students are hungry, tired, or feel unsafe, their brains prioritise survival over academic achievement, making it nearly impossible to concentrate on lessons. Teachers can support learning by ensuring classroom environmentsfeel safe and by being aware of students' basic needs through programs like free breakfast or creating predictable rou"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Is Drive Theory and How Does It Explain Student Motivation?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Drive Theory suggests that student motivation stems from internal tensions or \"drives\" that create discomfort until satisfied. In education, this means students are motivated to learn when they experience curiosity gaps, knowledge deficits, or achievement tensions that require resolution. Teachers can harness Drive Theory by creating productive cognitive dissonance through challenging questions, knowledge gaps, and problems that students feel compelled to solve."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Does Self-Determination Theory Impact Classroom Engagement?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Self-Determination Theory identifies three basic psychological needs - autonomy, competence, and relatedness - that must be satisfied for students to develop intrinsic motivation. When students feel they have choice in their learning (autonomy), can master skills successfully (competence), and belong to their learning community (relatedness), they engage more deeply and persistently. This theory explains why student-centred approaches often outperform teacher-directed methods in promoting lastin"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Role Does Expectancy Theory Play in Student Achievement?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Expectancy Theory explains student motivation through three key components: expectancy (belief they can succeed), instrumentality (belief that success leads to valued outcomes), and valence (how much they value those outcomes). Students are most motivated when they believe they can succeed, see clear connections between effort and rewards, and genuinely value what they're working towards. This theory helps teachers understand why some students disengage despite having ability."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Can Teachers Apply Achievement Motivation Theory?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Achievement Motivation Theory focuses on students' need for achievement versus their fear of failure, suggesting that motivation depends on which drive is stronger. Students with high achievement motivation seek challenging tasks and persist through difficulties, while those with high fear of failure avoid risks and give up easily. Teachers can creates achievement motivation by celebrating effort over ability, providing appropriate challenges, and creating psychologically safe environments where"}}]}]}