Experiential Learning

Explore experiential learning: its definition, Kolb's model, classroom implementation, key stages, and the roles of instructors and students in the process.

Explore experiential learning: its definition, Kolb's model, classroom implementation, key stages, and the roles of instructors and students in the process.

Experiential learning is an educational approach where students learn through direct experience, active involvement, and reflection on real-world activities. Rather than passively receiving information, learners engage in hands-on tasks like building prototypes, role-playing, or solving problems, then reflect on what they discovered. This method connects abstract concepts to tangible experiences, making learning more relevant and memorable.

Experiential learning is an educational approach built around active involvement, reflection, and personal meaning-making. Rather than positioning students as passive recipients of information, it invites them to engage directly with the world, solving problems, working collaboratively, and drawing conclusions from their own experiences.

This learner-centered model places doing and reflecting at the core of the learning process. Whether it's through building a prototype, participating in a role-play, or contributing to a community project, the emphasis is on exploration with purpose. Learners immerse themselves in an activity, encounter real challenges, and then pause to consider what the experience revealed, about the content, the context, and themselves.

Unlike more traditional methods that often prioritise explanation before action, experiential learning begins with a lived moment and works outward. It allows learners to connect abstract concepts with tangible encounters, bridging theory and practice in a way that feels relevant and immediate.

It's also remarkably versatile. A science lesson might involve designing a water filtration system. A history unit might ask students to simulate a town hall debate. Even a simple outdoor maths task can become an experiential moment when learners estimate distances and then test them physically. These aren't just activities, they're opportunities to think critically, collaborate meaningfully, and see learning in motion.

A saying commonly (though perhaps incorrectly) attributed to Benjamin Franklin captures this well: "Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn." Experiential learning honours that principle. It's not a supplement to learning; it's a powerful route into deeper understanding, where participation leads to ownership, and reflection turns experience into insight.

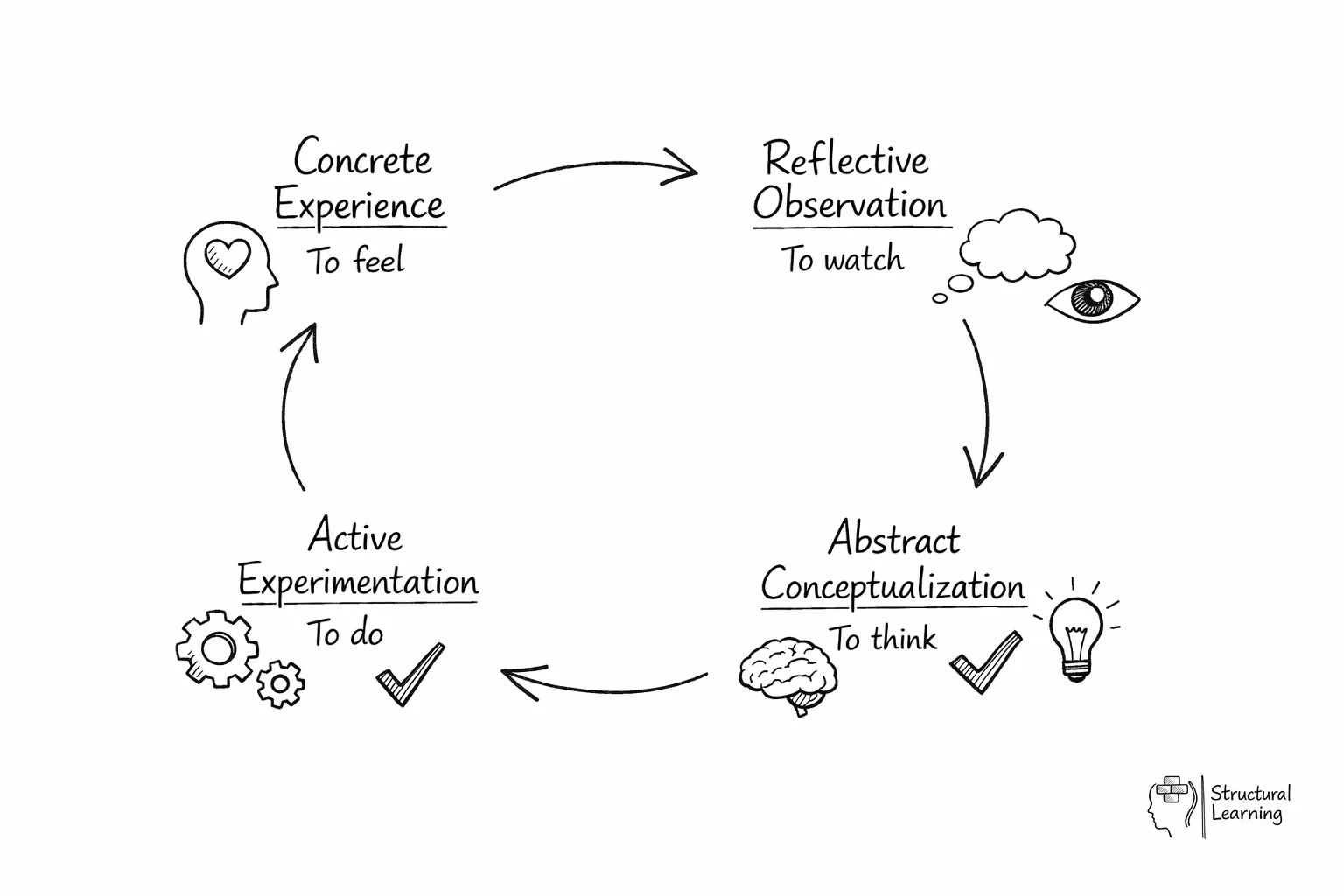

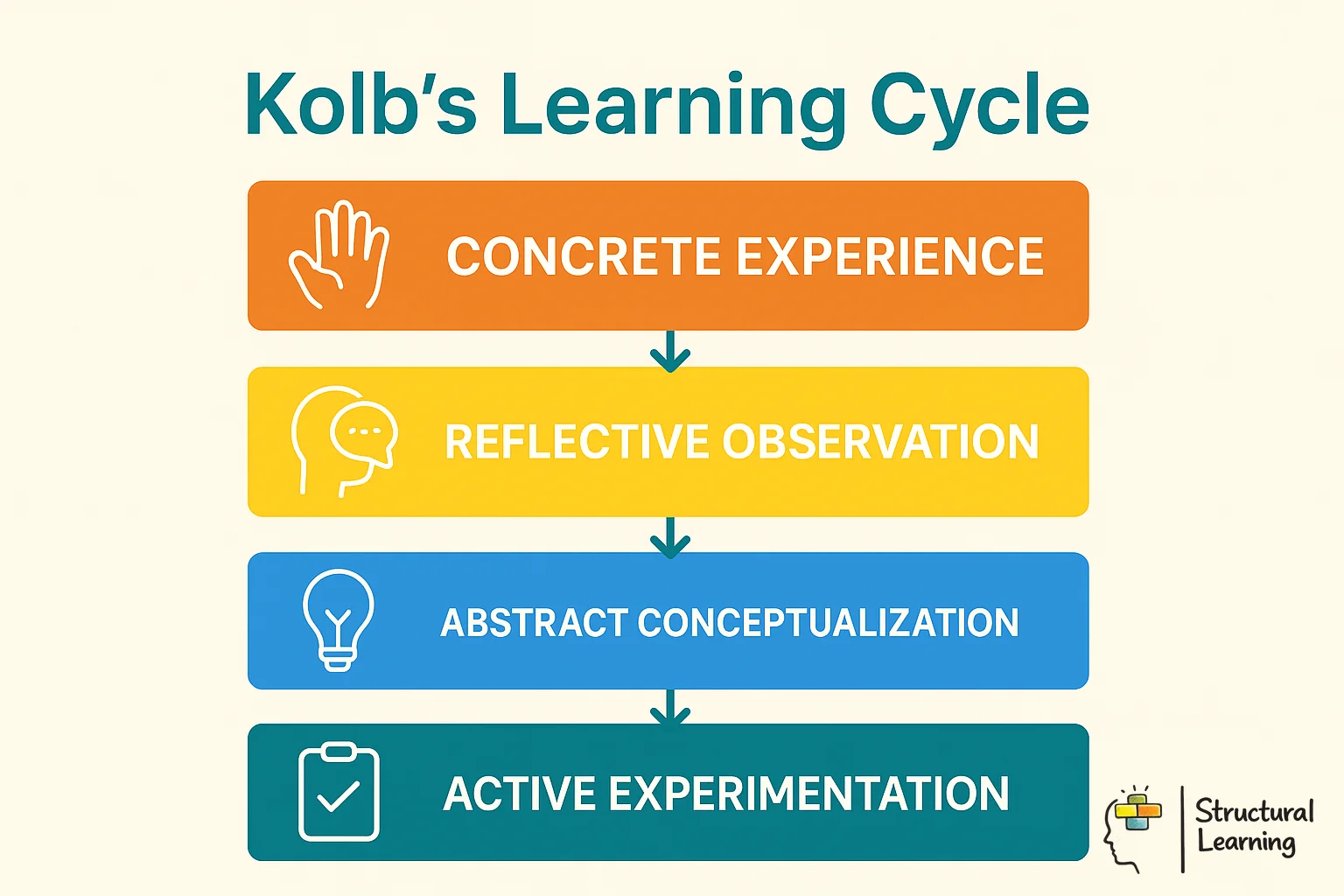

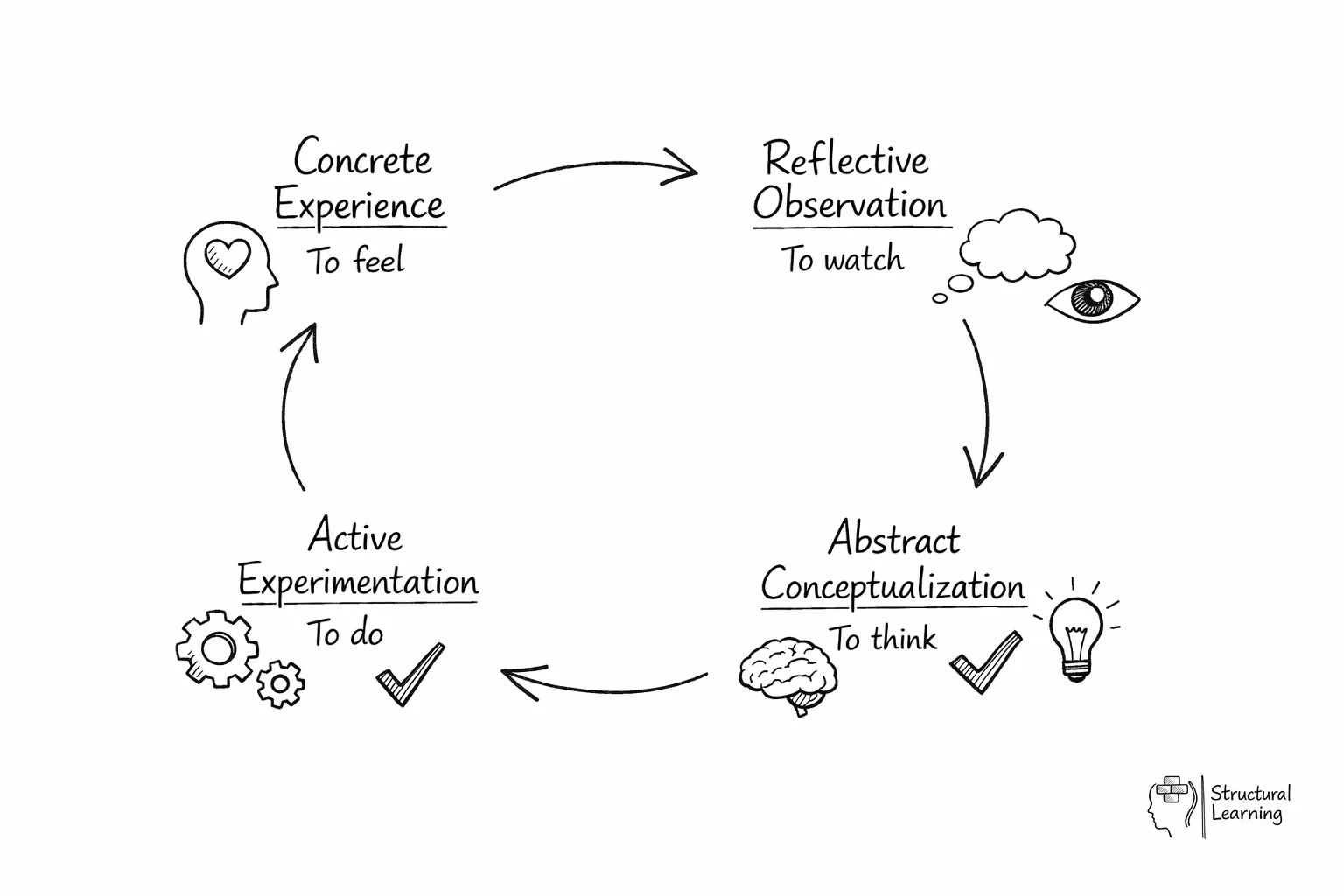

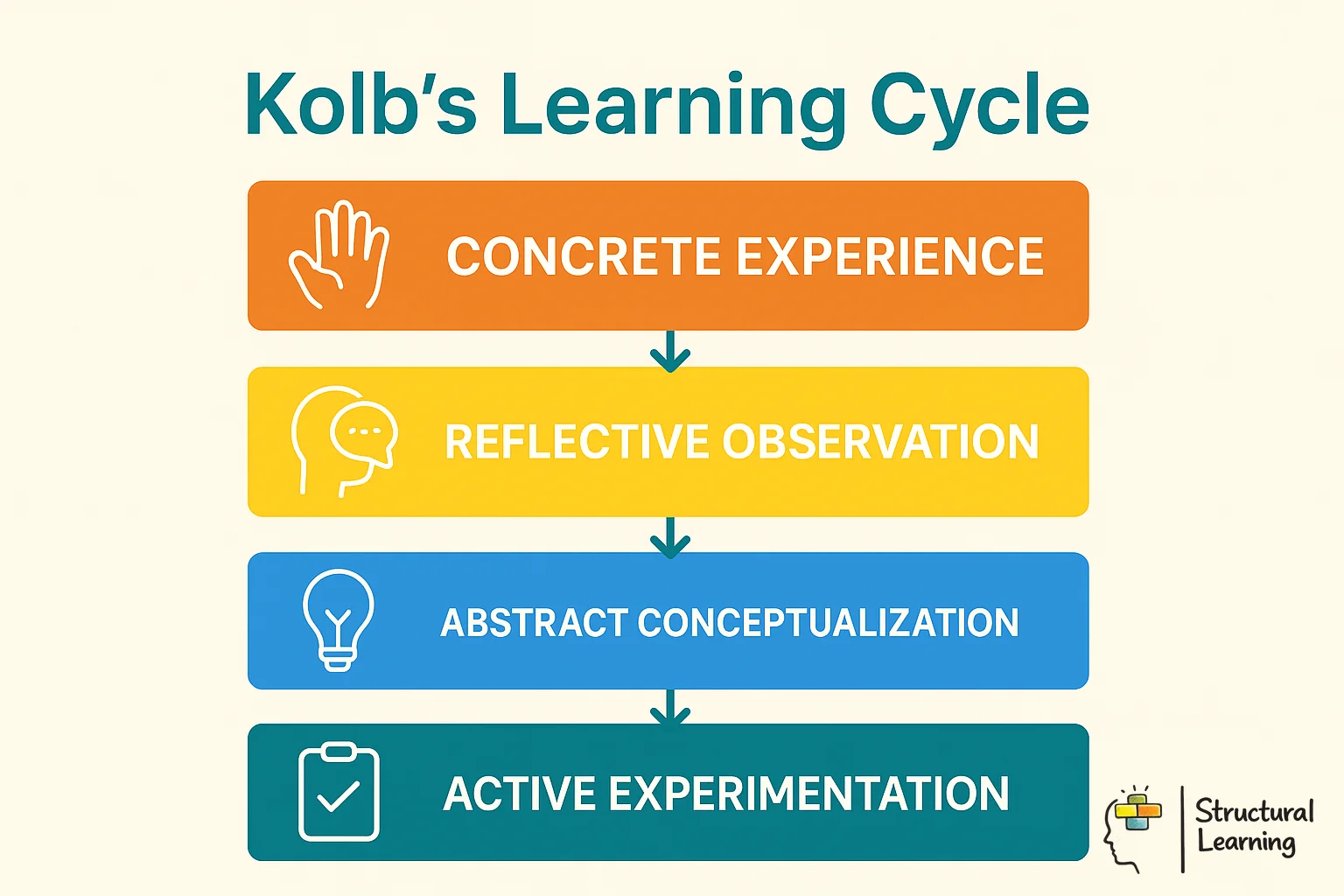

Kolb's cycle consists of four stages: concrete experience (doing), reflective observation (reviewing), abstract conceptualization (concluding), and active experimentation (planning). Students move through these stages in order, starting with a hands-on activity, reflecting on what happened, forming new ideas based on their observations, then testing those ideas in new situations. This cyclical process ensures learning is both practical and theoretical.

In 1974, David Kolb created his Experiential Learning Cycle. Kolb's four-stage Experiential Learning Theory model perceives education as an integrated process. All of these four stages are mutually supportive as David Kolb's Philosophy Of Education demonstrates that effective learning is cyclic involving experience, reflection, critical thinkingprocess and action.

According to David Kolb's Experiential Learning Theory learning is a process in which knowledge is developed through the modification of experience. Kolb's Experiential Learning Model has four stages:

Concrete Experience (CE): To feel

Reflective Observation (RO): To watch

Abstract Conceptualization (AC): To think

Active Experimentation (AE): To do

The above four steps or stages, of learning frequently move in the form of a cycle that starts with a learner having a concrete experience and finishes with their active experimentation on learning.

Teachers can implement experiential learning by designing activities that require students to actively engage with content, such as science experiments, historical simulations, or community projects. Start with a concrete experience like building a water filtration system, then guide students through reflection questions about what worked, what didn't, and why. Follow up by helping students connect their observations to broader concepts and plan how to apply their learning in new contexts.

Experiential learning doesn't rely on the idea that each student has a fixed learning style -visual, auditory, kinaesthetic, or otherwise. In fact, the research now tells us that the popular learning styles theorytheory is not supported by evidence. What matters is the cyclical process of active participation, thoughtful reflection, and iterative action.

So, how can teachers put this into practice?

Here are some tried-and-tested techniques:

Project-based learning: Engage students in complex, real-world projects that require them to apply their knowledge and skills over an extended period.

Simulations and role-playing: Create immersive experiences that allow students to step into different roles and perspectives, making abstract concepts more tangible.

Field trips and outdoor activities: Take learning outside the classroom to provide direct, hands-on experiences in real-world settings.

Experiments and investigations: Design experiments that allow students to explore scientific principles through direct observation and manipulation.

Community-based projects: Involve students in addressing local issues and contributing to their communities, developing a sense of social responsibility.

Experiential learning offers a wealth of benefits for students, developing deeper understanding, critical thinking, and a lifelong love of learning. By actively engaging with content, students are more likely to retain information and apply it in new contexts. The emphasis on reflection encourages them to think critically about their experiences, make connections between theory and practice, and develop problem-solving skills. Moreover, experiential learning cultivates a sense of ownership and agency, helping students to take control of their own learning journey.

Ultimately, experiential learning is about creating meaningful and memorable learning experiences that extend beyond the classroom. By embracing this approach, educators can equip students with the skills, knowledge, and mindset they need to thrive in an ever-changing world. It's a shift from passive consumption to active creation, from rote memorisation to genuine understanding.

Research by educational psychologist David Kolb demonstrates that experiential learning leads to better retention rates compared to traditional lecture-based methods. Students who engage in hands-on learning show improved problem-solving abilities and can transfer knowledge more effectively to new situations.

Beyond academic gains, experiential learning develops crucial life skills including collaboration, communication, and resilience. When students work through real challenges together, they naturally practise negotiation, compromise, and leadership. These social and emotional benefits often prove as valuable as subject-specific learning outcomes, preparing students for future workplace demands and civic participation.

For classroom implementation, consider projects that mirror real-world scenarios relevant to your learning objectives. Science teachers might establish classroom ecosystems where students monitor environmental changes, whilst history educators could organise mock trials or debates about historical events. These practical applications ensure student engagement remains high because learners can see immediate relevance to their own lives. The key is designing experiences that challenge students appropriately whilst providing clear frameworks for reflection and assessment.

examine deeper into the theory and practice of experiential learning with these research papers:

Kolb, D. A. (1984). *Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development*. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Beard, C., & Wilson, J. P. (2006). *Experiential learning: A best practice handbook for educators and trainers*. Kogan Page.

Dewey, J. (1938). *Experience and education*. Kappa Delta Pi.

Roberts, T. G. (2006). Beyond reflection: Models and frameworks to support critical reflection in higher education. *Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 3*(2), 1-16.

Yardley, S., Teunissen, P. W., & Dornan, T. (2012). Experiential learning: AMEE Guide No. 63. *Medical Teacher, 34*(2), e102-e115.

Assessing experiential learning requires a fundamental shift from traditional testing methods towards performance-based evaluation that captures the process of learning alongside the final outcomes. David Kolb's experiential learning theory emphasises reflection as a critical component, suggesting that assessment should evaluate what students produce and how they engage with the cyclical process of experiencing, reflecting, conceptualising, and experimenting. This approach demands multiple assessment touchpoints throughout the learning journey rather than relying solely on end-point evaluation.

Effective assessment strategies combine formative and summative approaches that align with hands-on learning objectives. Portfolio assessments work particularly well, allowing students to document their learning process through photographs, reflective journals, peer feedback forms, and project iterations. Rubrics should focus on observable behaviours such as collaboration skills, problem-solving approaches, and adaptability when facing challenges, rather than purely academic knowledge recall.

Practical classroom implementation involves creating authentic assessment opportunities that mirror real-world applications. Consider using peer assessment protocols where students evaluate each other's contributions during group projects, self-reflection templates that guide metacognitive thinking, and presentation formats that require students to demonstrate both their final solutions and their learning process. This multi-faceted approach ensures comprehensive evaluation whilst maintaining student engagement throughout the experiential learning cycle.

Despite its proven benefits, experiential learning presents several significant challenges that educators must carefully consider. Resource intensity stands as perhaps the most immediate barrier, as hands-on learning often requires specialised materials, extended time periods, and smaller class sizes than traditional instruction methods. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that poorly structured experiential activities can overwhelm students with extraneous information, particularly when learners lack sufficient prior knowledge to process complex, real-world scenarios effectively.

Assessment difficulties compound these implementation challenges, as traditional evaluation methods often fail to capture the nuanced learning that occurs through experiential activities. Unlike standardised tests that measure discrete knowledge points, hands-on learning generates diverse outcomes that resist simple measurement. Furthermore, not all learning objectives align well with experiential approaches; abstract concepts or foundational knowledge may require direct instruction before students can meaningfully engage in practical application.

Successful classroom implementation requires honest evaluation of when experiential learning serves your specific learning objectives. Consider beginning with hybrid approaches that combine direct instruction with targeted hands-on activities, allowing you to manage resources whilst building student confidence. Remember that experiential learning works best as part of a varied pedagogical toolkit rather than a complete replacement for other proven teaching methods.

Mathematics transforms from abstract concepts to tangible understanding when students manipulate physical objects to explore algebraic relationships. Rather than simply memorising formulas, learners can use algebra tiles to visualise polynomial multiplication or employ measuring tools to discover geometric principles through direct observation. This hands-on learning approach aligns with Piaget's constructivist theory, demonstrating how students build mathematical knowledge through active manipulation of their environment.

Science classrooms naturally lend themselves to experiential methods, moving beyond textbook descriptions to authentic investigation. Students designing experiments to test water quality in local streams not only master scientific methodology but also develop genuine ownership of their learning. Similarly, history comes alive when pupils role-play historical debates or analyse primary source documents, transforming passive consumption of facts into active historical thinking that mirrors real historians' work.

Language arts benefits tremendously from experiential approaches that connect reading and writing to real-world purposes. Students publishing newsletters for their community or conducting interviews with local residents engage with authentic audiences whilst developing essential literacy skills. These practical applications ensure that learning objectives extend beyond academic achievement to include genuine communication skills that serve students throughout their lives.

Experiential learning is an educational approach where students learn through direct experience, active involvement, and reflection on real-world activities. Rather than passively receiving information, learners engage in hands-on tasks like building prototypes, role-playing, or solving problems, then reflect on what they discovered. This method connects abstract concepts to tangible experiences, making learning more relevant and memorable.

Experiential learning is an educational approach built around active involvement, reflection, and personal meaning-making. Rather than positioning students as passive recipients of information, it invites them to engage directly with the world, solving problems, working collaboratively, and drawing conclusions from their own experiences.

This learner-centered model places doing and reflecting at the core of the learning process. Whether it's through building a prototype, participating in a role-play, or contributing to a community project, the emphasis is on exploration with purpose. Learners immerse themselves in an activity, encounter real challenges, and then pause to consider what the experience revealed, about the content, the context, and themselves.

Unlike more traditional methods that often prioritise explanation before action, experiential learning begins with a lived moment and works outward. It allows learners to connect abstract concepts with tangible encounters, bridging theory and practice in a way that feels relevant and immediate.

It's also remarkably versatile. A science lesson might involve designing a water filtration system. A history unit might ask students to simulate a town hall debate. Even a simple outdoor maths task can become an experiential moment when learners estimate distances and then test them physically. These aren't just activities, they're opportunities to think critically, collaborate meaningfully, and see learning in motion.

A saying commonly (though perhaps incorrectly) attributed to Benjamin Franklin captures this well: "Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn." Experiential learning honours that principle. It's not a supplement to learning; it's a powerful route into deeper understanding, where participation leads to ownership, and reflection turns experience into insight.

Kolb's cycle consists of four stages: concrete experience (doing), reflective observation (reviewing), abstract conceptualization (concluding), and active experimentation (planning). Students move through these stages in order, starting with a hands-on activity, reflecting on what happened, forming new ideas based on their observations, then testing those ideas in new situations. This cyclical process ensures learning is both practical and theoretical.

In 1974, David Kolb created his Experiential Learning Cycle. Kolb's four-stage Experiential Learning Theory model perceives education as an integrated process. All of these four stages are mutually supportive as David Kolb's Philosophy Of Education demonstrates that effective learning is cyclic involving experience, reflection, critical thinkingprocess and action.

According to David Kolb's Experiential Learning Theory learning is a process in which knowledge is developed through the modification of experience. Kolb's Experiential Learning Model has four stages:

Concrete Experience (CE): To feel

Reflective Observation (RO): To watch

Abstract Conceptualization (AC): To think

Active Experimentation (AE): To do

The above four steps or stages, of learning frequently move in the form of a cycle that starts with a learner having a concrete experience and finishes with their active experimentation on learning.

Teachers can implement experiential learning by designing activities that require students to actively engage with content, such as science experiments, historical simulations, or community projects. Start with a concrete experience like building a water filtration system, then guide students through reflection questions about what worked, what didn't, and why. Follow up by helping students connect their observations to broader concepts and plan how to apply their learning in new contexts.

Experiential learning doesn't rely on the idea that each student has a fixed learning style -visual, auditory, kinaesthetic, or otherwise. In fact, the research now tells us that the popular learning styles theorytheory is not supported by evidence. What matters is the cyclical process of active participation, thoughtful reflection, and iterative action.

So, how can teachers put this into practice?

Here are some tried-and-tested techniques:

Project-based learning: Engage students in complex, real-world projects that require them to apply their knowledge and skills over an extended period.

Simulations and role-playing: Create immersive experiences that allow students to step into different roles and perspectives, making abstract concepts more tangible.

Field trips and outdoor activities: Take learning outside the classroom to provide direct, hands-on experiences in real-world settings.

Experiments and investigations: Design experiments that allow students to explore scientific principles through direct observation and manipulation.

Community-based projects: Involve students in addressing local issues and contributing to their communities, developing a sense of social responsibility.

Experiential learning offers a wealth of benefits for students, developing deeper understanding, critical thinking, and a lifelong love of learning. By actively engaging with content, students are more likely to retain information and apply it in new contexts. The emphasis on reflection encourages them to think critically about their experiences, make connections between theory and practice, and develop problem-solving skills. Moreover, experiential learning cultivates a sense of ownership and agency, helping students to take control of their own learning journey.

Ultimately, experiential learning is about creating meaningful and memorable learning experiences that extend beyond the classroom. By embracing this approach, educators can equip students with the skills, knowledge, and mindset they need to thrive in an ever-changing world. It's a shift from passive consumption to active creation, from rote memorisation to genuine understanding.

Research by educational psychologist David Kolb demonstrates that experiential learning leads to better retention rates compared to traditional lecture-based methods. Students who engage in hands-on learning show improved problem-solving abilities and can transfer knowledge more effectively to new situations.

Beyond academic gains, experiential learning develops crucial life skills including collaboration, communication, and resilience. When students work through real challenges together, they naturally practise negotiation, compromise, and leadership. These social and emotional benefits often prove as valuable as subject-specific learning outcomes, preparing students for future workplace demands and civic participation.

For classroom implementation, consider projects that mirror real-world scenarios relevant to your learning objectives. Science teachers might establish classroom ecosystems where students monitor environmental changes, whilst history educators could organise mock trials or debates about historical events. These practical applications ensure student engagement remains high because learners can see immediate relevance to their own lives. The key is designing experiences that challenge students appropriately whilst providing clear frameworks for reflection and assessment.

examine deeper into the theory and practice of experiential learning with these research papers:

Kolb, D. A. (1984). *Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development*. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Beard, C., & Wilson, J. P. (2006). *Experiential learning: A best practice handbook for educators and trainers*. Kogan Page.

Dewey, J. (1938). *Experience and education*. Kappa Delta Pi.

Roberts, T. G. (2006). Beyond reflection: Models and frameworks to support critical reflection in higher education. *Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 3*(2), 1-16.

Yardley, S., Teunissen, P. W., & Dornan, T. (2012). Experiential learning: AMEE Guide No. 63. *Medical Teacher, 34*(2), e102-e115.

Assessing experiential learning requires a fundamental shift from traditional testing methods towards performance-based evaluation that captures the process of learning alongside the final outcomes. David Kolb's experiential learning theory emphasises reflection as a critical component, suggesting that assessment should evaluate what students produce and how they engage with the cyclical process of experiencing, reflecting, conceptualising, and experimenting. This approach demands multiple assessment touchpoints throughout the learning journey rather than relying solely on end-point evaluation.

Effective assessment strategies combine formative and summative approaches that align with hands-on learning objectives. Portfolio assessments work particularly well, allowing students to document their learning process through photographs, reflective journals, peer feedback forms, and project iterations. Rubrics should focus on observable behaviours such as collaboration skills, problem-solving approaches, and adaptability when facing challenges, rather than purely academic knowledge recall.

Practical classroom implementation involves creating authentic assessment opportunities that mirror real-world applications. Consider using peer assessment protocols where students evaluate each other's contributions during group projects, self-reflection templates that guide metacognitive thinking, and presentation formats that require students to demonstrate both their final solutions and their learning process. This multi-faceted approach ensures comprehensive evaluation whilst maintaining student engagement throughout the experiential learning cycle.

Despite its proven benefits, experiential learning presents several significant challenges that educators must carefully consider. Resource intensity stands as perhaps the most immediate barrier, as hands-on learning often requires specialised materials, extended time periods, and smaller class sizes than traditional instruction methods. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that poorly structured experiential activities can overwhelm students with extraneous information, particularly when learners lack sufficient prior knowledge to process complex, real-world scenarios effectively.

Assessment difficulties compound these implementation challenges, as traditional evaluation methods often fail to capture the nuanced learning that occurs through experiential activities. Unlike standardised tests that measure discrete knowledge points, hands-on learning generates diverse outcomes that resist simple measurement. Furthermore, not all learning objectives align well with experiential approaches; abstract concepts or foundational knowledge may require direct instruction before students can meaningfully engage in practical application.

Successful classroom implementation requires honest evaluation of when experiential learning serves your specific learning objectives. Consider beginning with hybrid approaches that combine direct instruction with targeted hands-on activities, allowing you to manage resources whilst building student confidence. Remember that experiential learning works best as part of a varied pedagogical toolkit rather than a complete replacement for other proven teaching methods.

Mathematics transforms from abstract concepts to tangible understanding when students manipulate physical objects to explore algebraic relationships. Rather than simply memorising formulas, learners can use algebra tiles to visualise polynomial multiplication or employ measuring tools to discover geometric principles through direct observation. This hands-on learning approach aligns with Piaget's constructivist theory, demonstrating how students build mathematical knowledge through active manipulation of their environment.

Science classrooms naturally lend themselves to experiential methods, moving beyond textbook descriptions to authentic investigation. Students designing experiments to test water quality in local streams not only master scientific methodology but also develop genuine ownership of their learning. Similarly, history comes alive when pupils role-play historical debates or analyse primary source documents, transforming passive consumption of facts into active historical thinking that mirrors real historians' work.

Language arts benefits tremendously from experiential approaches that connect reading and writing to real-world purposes. Students publishing newsletters for their community or conducting interviews with local residents engage with authentic audiences whilst developing essential literacy skills. These practical applications ensure that learning objectives extend beyond academic achievement to include genuine communication skills that serve students throughout their lives.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/experiential-learning#article","headline":"Experiential Learning","description":"Explore experiential learning: its definition, Kolb's model, classroom implementation, key stages, and the roles of instructors and students in the process.","datePublished":"2023-01-26T15:42:16.874Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/experiential-learning"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a3f1cfcb2bc95a5f1b5b0_696a3f1641bb877236469019_experiential-learning-illustration.webp","wordCount":3826},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/experiential-learning#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Experiential Learning","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/experiential-learning"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/experiential-learning#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What exactly is experiential learning and how does it differ from traditional teaching methods?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Experiential learning is an educational approach where students learn through direct experience, active involvement, and reflection on real-world activities rather than passively receiving information. Unlike traditional methods that prioritise explanation before action, experiential learning begins"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers practically implement Kolb's four-stage learning cycle in their classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can start with a concrete experience like a science experiment or historical simulation, then guide students through reflection questions about what worked and why. They should help students connect their observations to broader concepts during the abstract conceptualisation stage, then enc"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are some specific examples of experiential learning activities across different subjects?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"In science, students might design a water filtration system to explore concepts of materials and processes. History lessons could involve simulating town hall debates or role-playing historical scenarios to understand different perspectives and decision-making processes. Even maths can become experi"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why is experiential learning considered more effective than the traditional learning styles approach?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Research shows that the popular learning styles theory is oversimplified, as people don't learn better because content matches a preferred style, but when they engage with ideas in varied and meaningful ways. Experiential learning offers a flexible structure that supports all learners through active"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What challenges might teachers face when implementing experiential learning, and how can they overcome them?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers may struggle with moving from traditional explanation-first methods to experience-first approaches, requiring careful planning to structure meaningful activities. The key challenge is ensuring that hands-on activities aren't just tasks but genuine opportunities for critical thinking and ref"}}]}]}