Id, Ego and Superego: Freud's Theory for Teachers

How does Sigmund Freud theory explain classroom dynamics? Explore psychoanalysis, child development, and key takeaways for school staff.

Sigmund Freud's groundbreaking theories about the unconscious mind, childhood development. Human motivation offer valuable insights for understanding and managing learner behaviour in school settings. The Austrian neurologist's psychoanalytic concepts can help educators recognise why students act. Struggle with authority, or display certain learning patterns in the classroom. By applying Freudian principles such as defence mechanisms, the role of early experiences. The structure of personality, teachers can develop moreeffective strategiesfor supporting challenging students and creating positive learning environments. But how exactly do these century-old psychological theories translate intopractical classroomapplications?

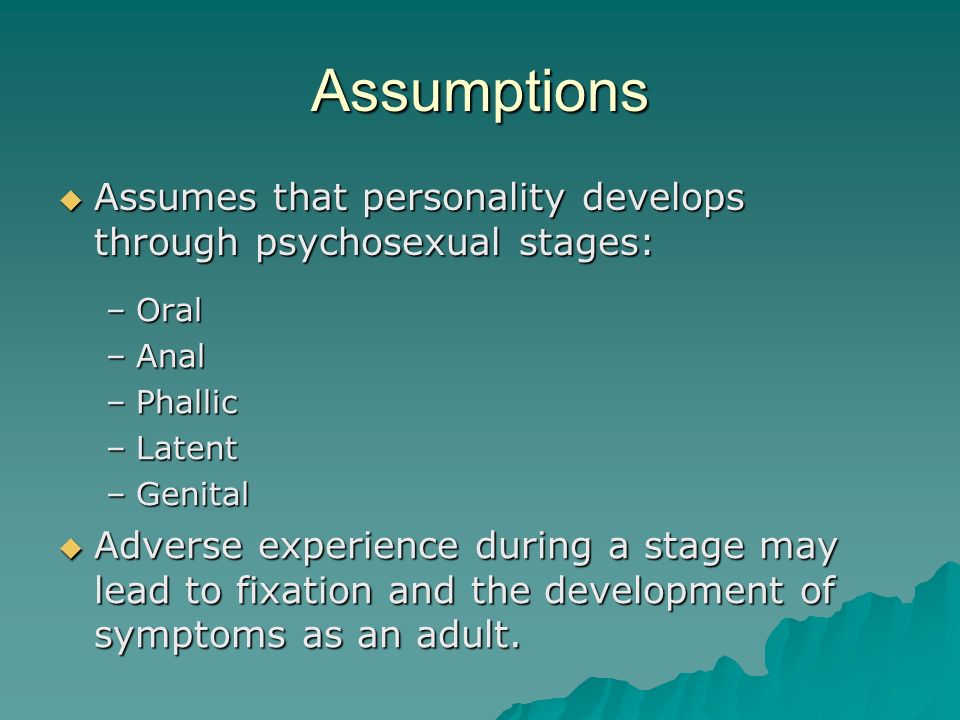

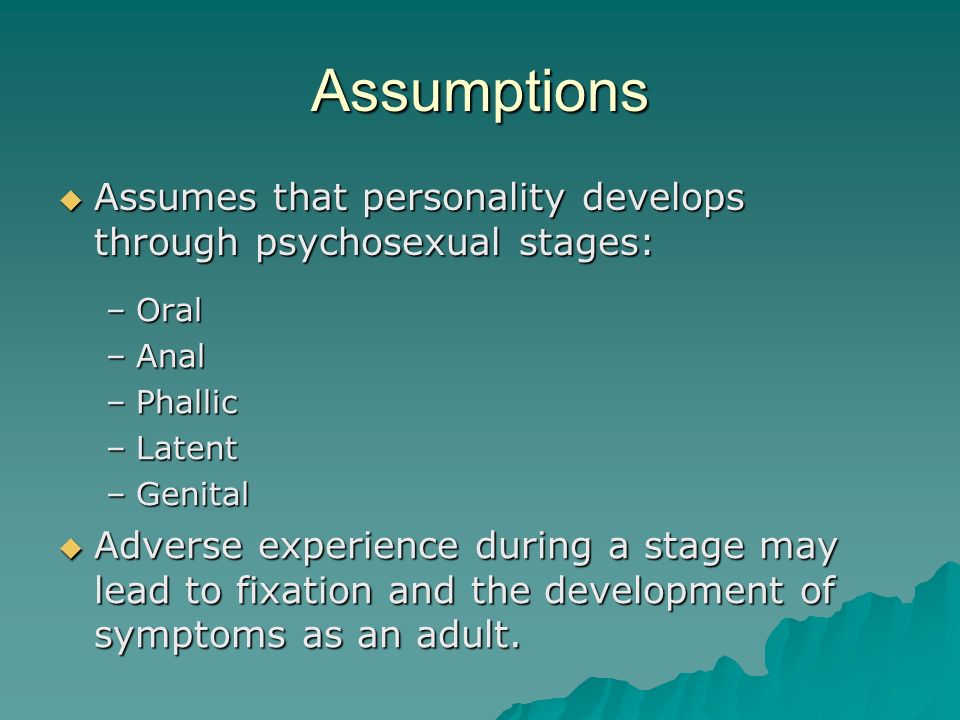

Sigmund Freud's psychodynamic theory proposes that human behaviour is driven by unconscious processes, internal conflicts between the id, ego. Superego, and early childhood experiences that shape personality through five psychosexual stages. Unlike cognitive theories that focus on conscious thought, Freud (1923) argued. This the most powerful influences on behaviour operate beneath awareness. Without acknowledging these unconscious dynamics, teachers may misread disruptive behaviour. Wilful defiance rather than an expression of unresolved emotional conflict.

Sigmund Freud, often called the father of psychoanalysis, was an Austrian neurologist whose theories transformed how wethink aboutthe mind. He founded the Psychoanalytic Movement in the early 20th century, drawing together like-minded thinkers in. Vienna Psychoanalytic Society to explore ideas about unconscious processes, childhood development, and the hiddenmotivationsbehind human behaviour.

Freud's central belief was that much of what drives our thoughts and actions lies beneath conscious awareness. He argued that repressed desires, memories, and conflicts shape our personalities. Can resurface in dreams, slips of the tongue, or neurotic symptoms. This idea shifted psychology away from simply studying observable behaviour. Towards investigating the deeper layers of the psyche needs verification, this date appears to be an error.

One of Freud's most influential contributions was his theory of psychosexual development. This proposed that early childhood experiences leave lasting impressions on our adult lives. He also introduced groundbreaking ideas about dream analysis, suggesting. This dreams are symbolic expressions of our innermost wishes and fears (Parbat, 2024). While many aspects of his work have sparked controversy, especially his emphasis on sexuality. The subjective nature of psychoanalysis, his ideas laid the foundation for modern psychotherapy and inspired thinkers likeCarl Jung tobuild their own psychological frameworks.

Key Points:

This podcast explores how Freud's psychodynamic theories influence our understanding of child behaviour, motivation. The unconscious processes that shape learning.

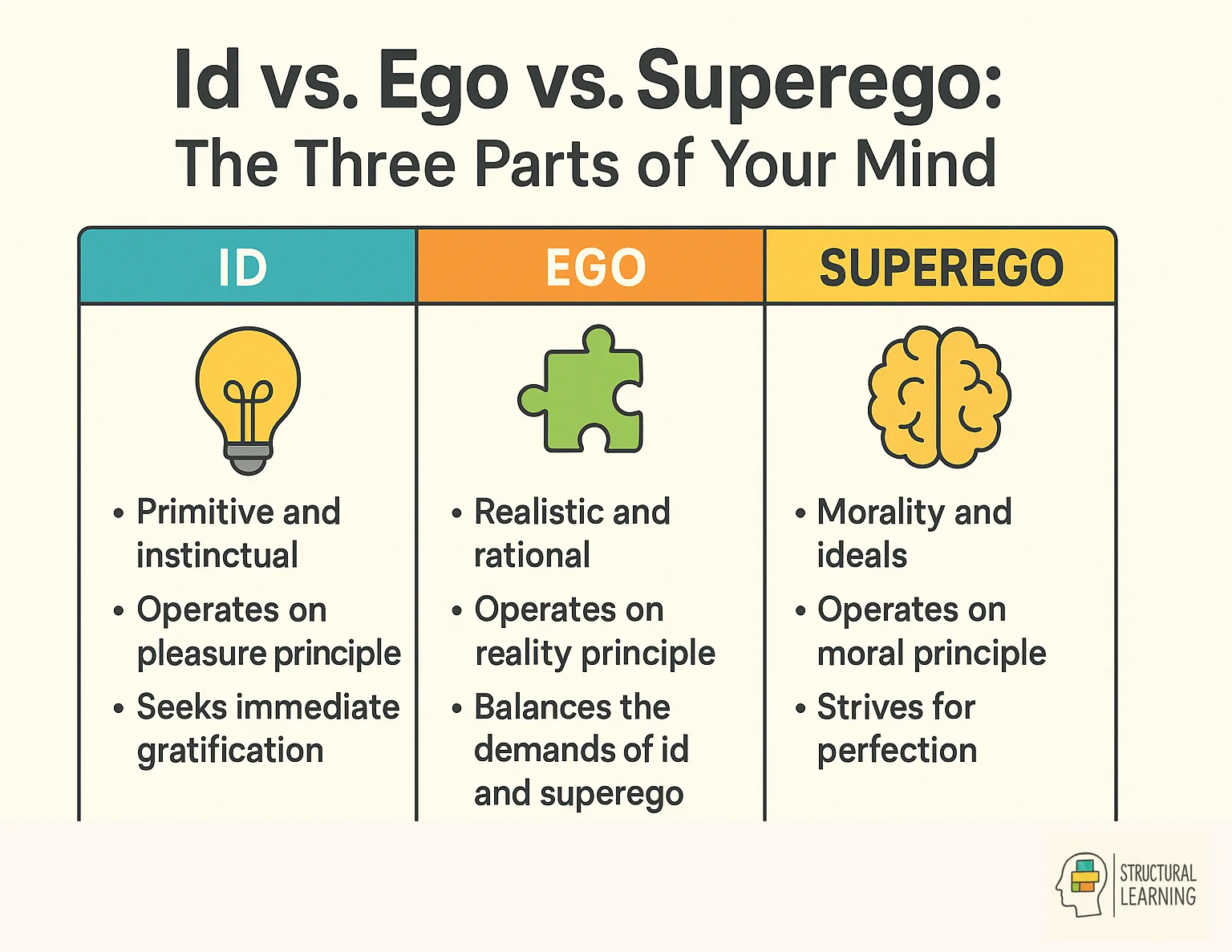

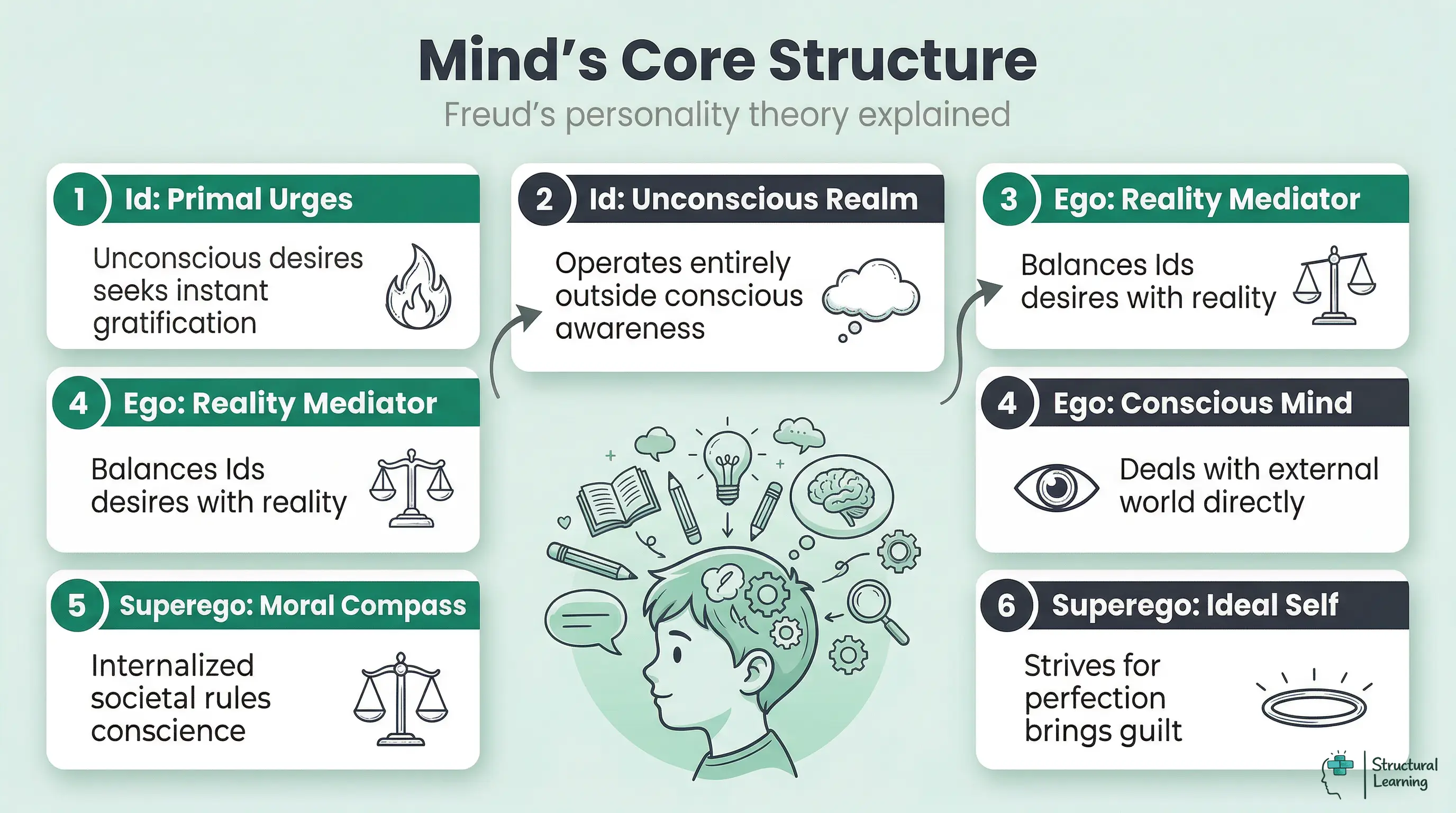

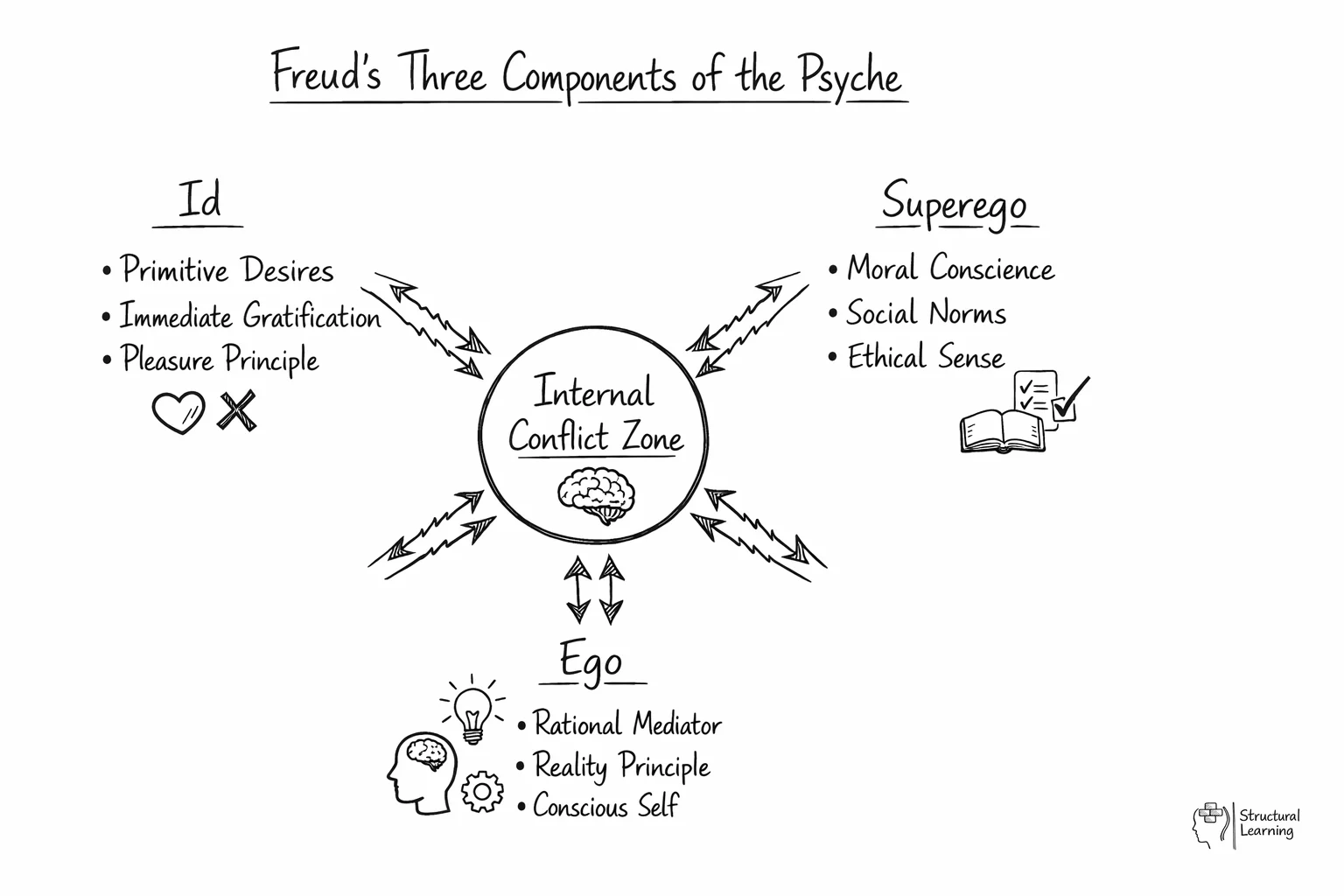

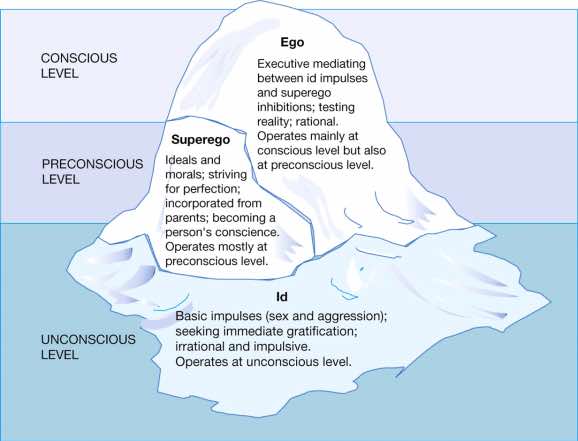

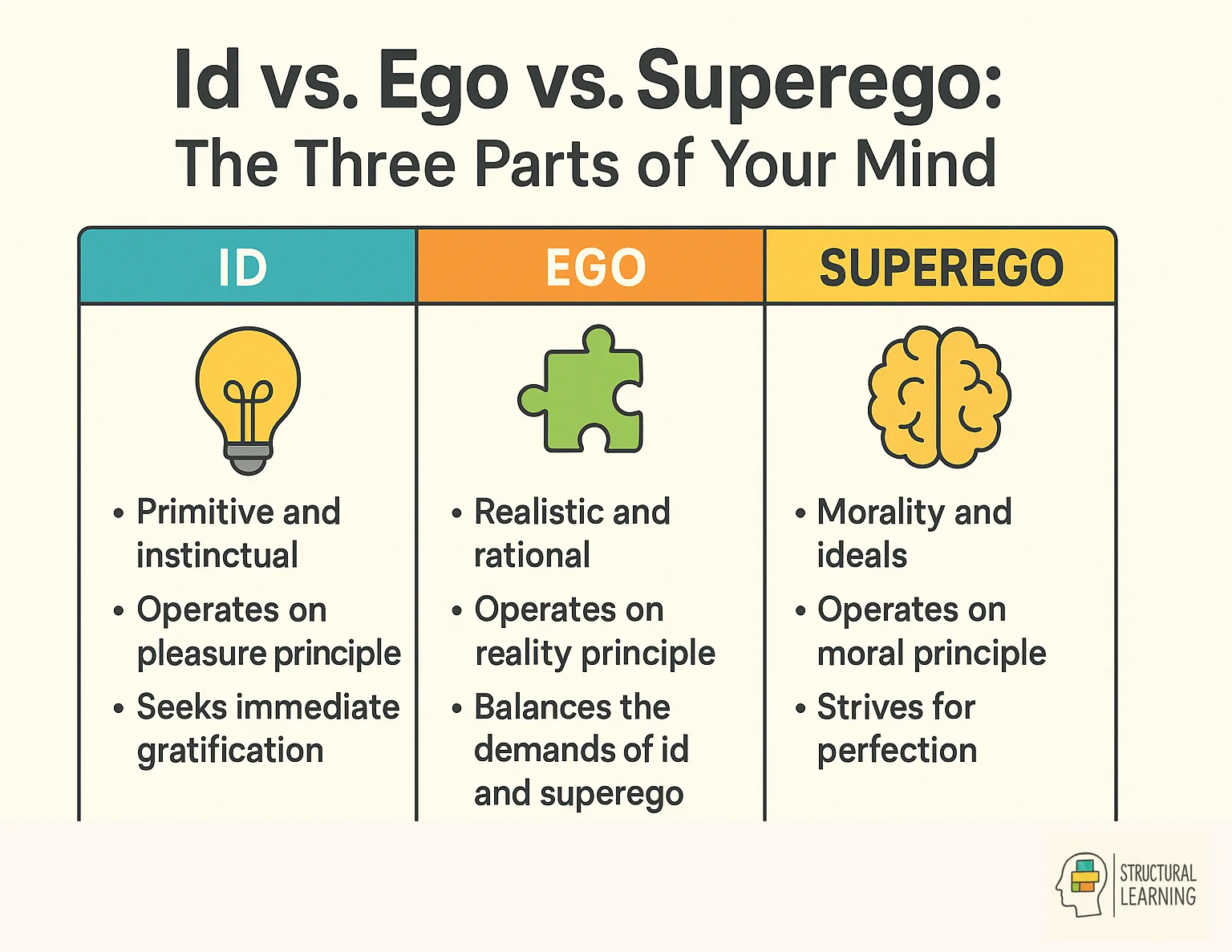

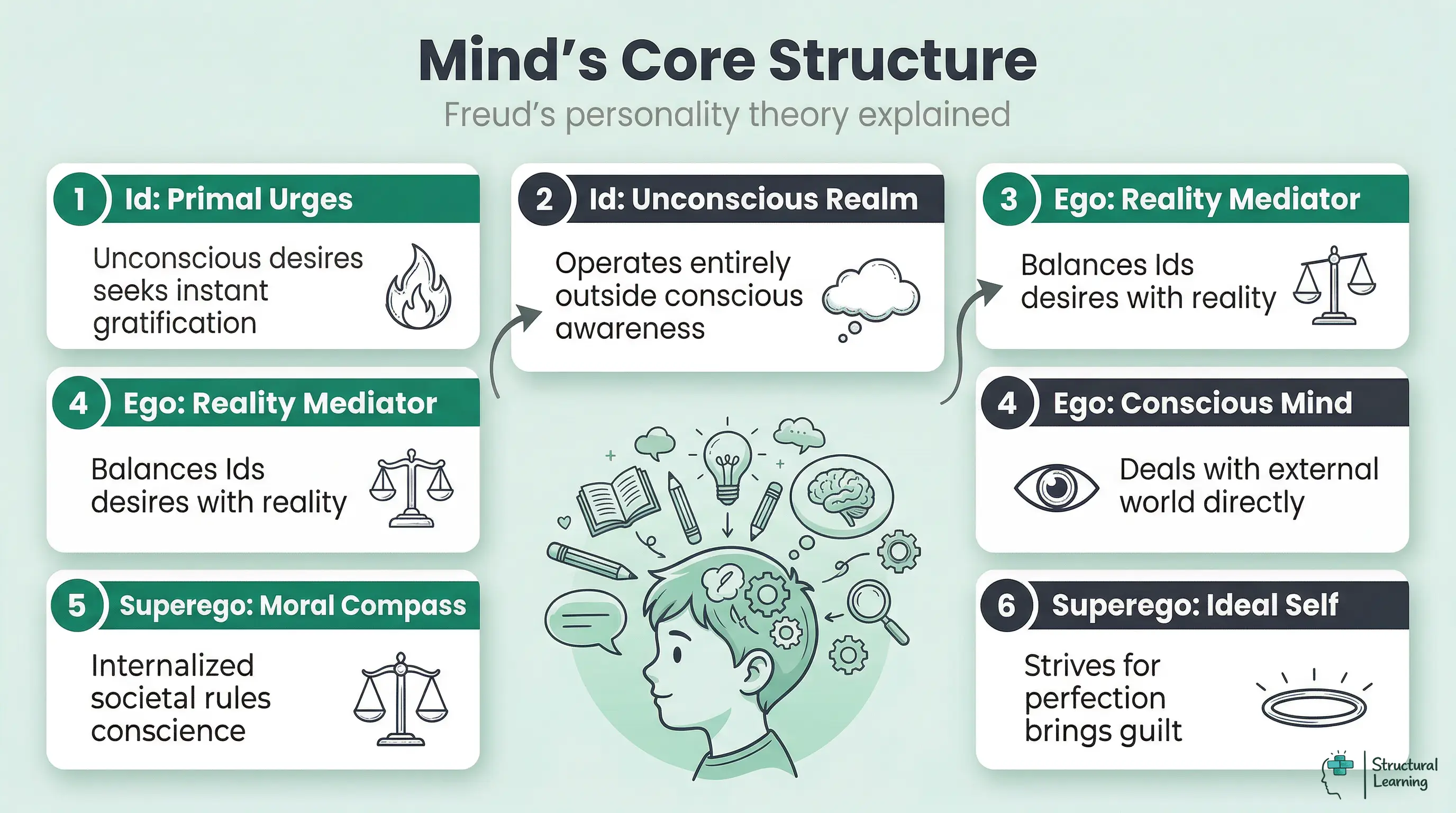

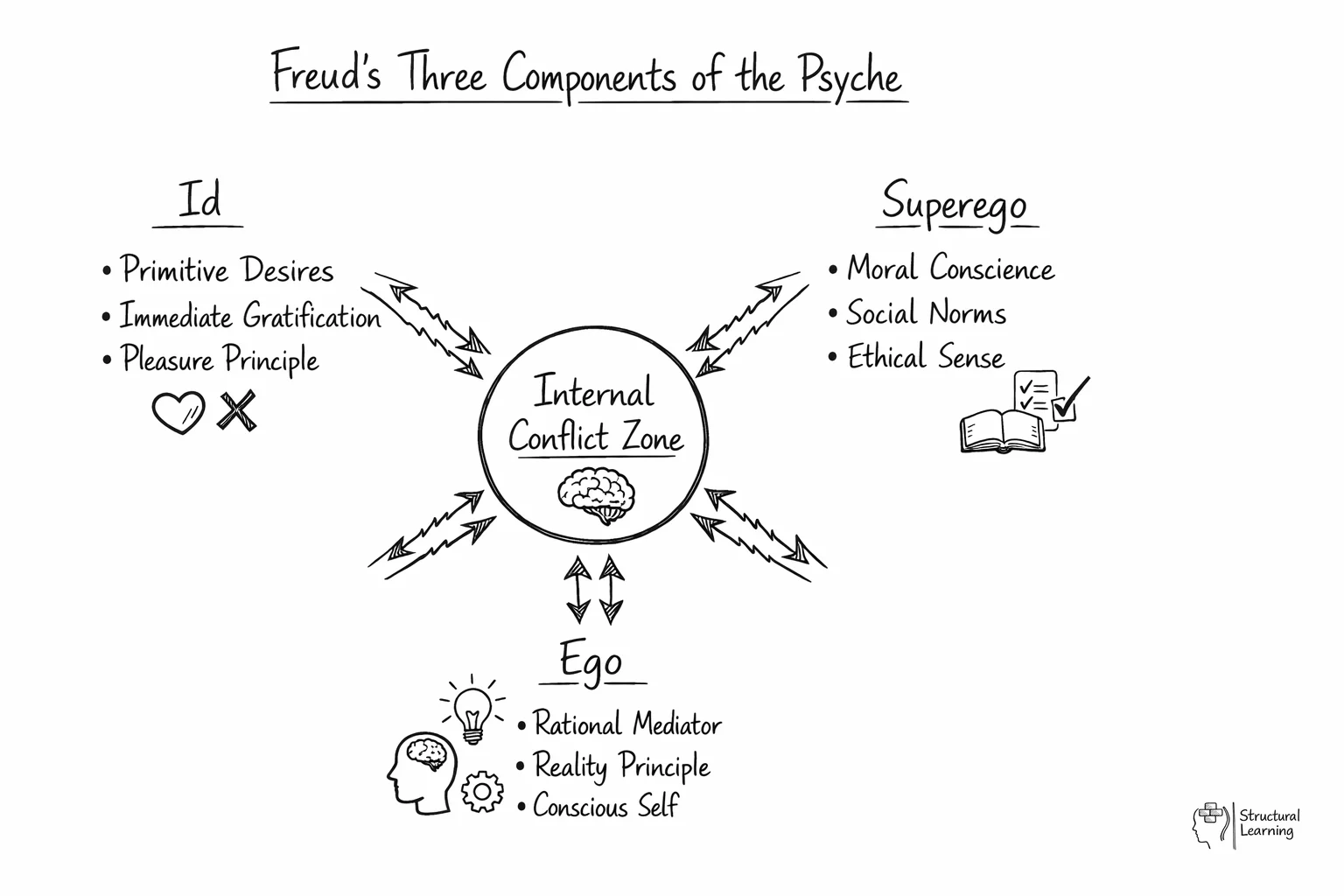

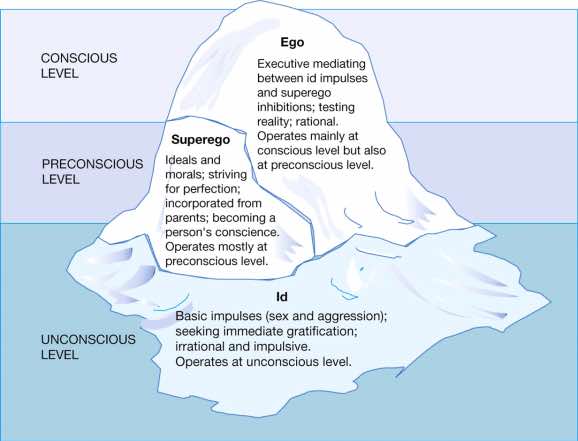

Freud's structural model divides the human psyche into three components: the id (primitive desires), the ego (rational mediator). The superego (moral conscience). , 2022).

The id, ego, and superego are three parts of the human psyche according to Freud's structural model. The id represents primitive desires and impulses, the ego manages reality. Mediates between desires and social expectations, whilst the superego acts as the moral conscience. These three components constantly interact to shape our thoughts, behaviours, and personality.

According to Sigmund Freud, the human psyche consists of three components: the id, ego, and superego. The id represents our primitive, instinctual drives, including our desire for food, sex, and pleasure.

The ego represents our rational, conscious self that mediates between the id and the external world. And the superego represents our moral and ethical sense, as well as our sense of right and wrong.

Together, these three components create complex human behaviour as they interact and influence each other. The id is impulsive and seeks immediate gratification whilst the superego is concerned with social norms and moral values.

This creates a constant internal conflict between our instinctual desires and our moral ideals. The ego tries to find a balance between the two, but thisis notalways easy.

, 2021). This can lead to complex variations in personality and behaviour. Understanding the workings of the id, ego, and superego is a effective method for gaining insight into the human mind. Behaviour needs verification, this date appears to be an error.

Personality Theory" id="" width="auto" height="auto">

Personality Theory" id="" width="auto" height="auto">Understanding Freud's structural model provides teachers with a powerful lens for interpreting challenging student behaviours (Chen & Huang, 2024). When a Year 3 pupil suddenly grabs a biscuit from another child's lunchbox despite knowing. Wrong, we're witnessing the id's demand for immediate gratification overpowering the superego's moral restraints. The ego, that rational mediator, has momentarily lost its battle to balance desire with social expectations.

In secondary classrooms, these conflicts manifest more subtly. A GCSE student who desperately wants to check their phone during revision (id) knows the school. Prohibit it (superego), so their ego might negotiate a compromise, quickly glancing at the device. The teacher isn't looking. This isn't simply rule-breaking; it's the ego attempting to satisfy the id whilst minimising superego-induced guilt and external consequences.

Teachers encounter these tripartite struggles constantly. The pupil who blurts out answers without raising their hand shows an id unchecked by ego control. The child who refuses to participate in group activities despite wanting to join. Reveals a superego so overdeveloped it induces paralysing anxiety about making mistakes. Recognising these patterns allows educators to respond more therapeutically, strengthening ego functions throughFreud's five psychosexualstages are oral (0-18 months), anal (18-36 months), phallic (3-6 years), latency (6-puberty), and genital (puberty onward). Each stage focuses on pleasure from different body areas. Unresolved conflicts at any stage can lead to fixations affecting adult personality. Successfully navigating these stages results in a healthy, mature personality needs verification, this date appears to be an error. Sigmund Freud's Theory of Psychosexual Development suggests that human personality develops through a series of stages, each of. This is centred around the satisfaction of certain physical or psychic needs. The phallic stage is the most critical stage in terms of personality development. Centres around the child's sexual desire, especially towards his or her parent of the opposite gender. In the latent phase, sexual desires are repressed, and energies are focused on developing skills. , 2025). The theory can help to identify the origins of psychological problems. Guide us towards the proper treatment of psychosexual disorders (Royle & Atkinson, 2025). Sigmund Freuds Theoretical StagesPsychosexual Stages: Classroom Signs Whilst modern educators rightfully reject Freud's literal sexual. Understanding these developmental stages provides valuable insights into childhood behaviours observed in educational settings. The table below translates Freudian theory into practical classroom observations. Stage Age Range Freudian Focus Classroom Implications Teaching Strategies Oral 0-18 months Sucking, feeding, dependency. Caregivers Nursery pupils may show excessive thumb-sucking, chewing on pencils, or clinging behaviours when stressed. Difficulty separating from parents at drop-off. Provide comfort objects, establish consistent routines, allow transitional support. Offer oral-sensory activities like chewy toys for anxious children. Anal 18-36 months Toilet training, control, order Preschool/Reception children may display extreme orderliness or messiness, stubbornness, or control issues. Some become obsessive about rules whilst others resist all structure. Balance structure with flexibility. Give children age-appropriate choices to encourage autonomy. Avoid power struggles over minor issues; focus on essential boundaries. Phallic 3-6 years Gender identity, parent attachment, Oedipus/Electra complex KS1 pupils. Show strong preferences for same-gender or opposite-gender teachers, competitive behaviours. Intense curiosity about bodies and gender differences. Provide age-appropriate body education, establish clear boundaries, model healthy adult relationships. Don't shame natural developmental curiosity; redirect appropriately. Latency 6 years-puberty Social skills, academic learning, repression of sexual interests Primary school. (KS2) show intense focus on friendships, academic achievement, hobbies, and same-gender peer groups. Ideal period for skill development and learning. Maximise this developmentally optimal learning window. Support collaborative projects, encourage diverse skill development, support healthy peer relationships and social problem-solving. Genital Puberty onwards Sexual maturation, romantic relationships, adult sexuality Secondary pupils navigate identity formation, romantic attractions, peer pressure. Establishing independence from parents. Increased moodiness and risk-taking behaviours. Provide comprehensive relationships education, create safe spaces for identity exploration, maintain consistent boundaries whilst respecting growing autonomy. Address consent and healthy relationships explicitly. Understanding these stages helps teachers recognise that certain behaviours aren't defiance but developmental signs. Dream Analysis in Freudian Psychology Freud's dream analysis theory suggests. This dreams represent the unconscious mind's attempt to fulfil repressed wishes and desires. He distinguished between manifest content (what we remember) and latent content (hidden psychological meaning). Freud believed dreams were the 'royal road to the unconscious' and contained hidden wishes and repressed desires in symbolic form. He distinguished between manifest content (what you remember) and latent content (the hidden psychological meaning). Dream analysis involves uncovering these hidden meanings through free association and symbol interpretation. Freud's theory of dream interpretation posits that dreams are the "royal road to the unconscious mind. The unconscious mind communicates symbolically, and the dream is a signs of these symbols. Condensation occurs when multiple unconscious desires are combined into a single dream symbol. Displacement occurs when an unconscious desire is represented indirectly by something else. Symbolism is the use of objects or events to represent something else. Decoding dreams is important because it uncovers these repressed desires and helps individuals understand their unconscious motives. Through dreams, individuals can explore their unresolved issues and uncover the origins of their psychological conflicts. Dream Analysis in Educational Settings Whilst teachers shouldn't attempt therapeutic dream analysis, understanding Freud's. About the unconscious mind expressing itself symbolically proves remarkably useful in educational contexts. When students share recurring nightmares about missing exams, showing up. School naked, or being chased, these aren't random neurological firings. Symbolic expressions of anxiety about performance, vulnerability, and feeling overwhelmed. Fixation, in Freudian theory, is the persistent attachment of libidinal energy to an earlier psychosexual stage, resulting in behaviours. Personality traits associated with that stage continuing into later life. Freud (1905) proposed two routes to fixation: frustration, where the needs of a developmental stage are inadequately met. Overindulgence, where they are excessively gratified. Both prevent the normal forward flow of psychic energy through the oral, anal, phallic, latent and genital stages. A child whose oral stage needs were frustrated through inconsistent feeding. Early weaning may develop oral-passive traits such as dependency, gullibility. Excessive trust, or oral-aggressive traits such as verbal hostility, sarcasm and nail-biting. Conversely, a child overindulged at the anal stage. Parents imposed no consistent boundaries around toilet training, may develop. Anal-expulsive personality marked by messiness, defiance and poor impulse control. The anal-retentive personality, associated with excessive strictness during toilet training, manifests as rigidity, orderliness and a need for control. While these specific mappings remain empirically contested, the broader principle. This early relational experiences shape later personality is well supported byattachment research. In classroom settings, the concept of fixation offers a framework for understanding pupils whose behaviour seems developmentally incongruent. A Year 9 pupil who constantly chews pens, seeks physical comfort from adults, or becomes distressed. Separated from a particular friend may be displaying oral-stage fixation behaviours.Classroom implication:Rather than interpreting these behaviours as deliberate disruption, Freudian fixation theory suggests they signal unmet developmental needs. The teacher's response should address the underlying need (security, predictability, autonomy) rather than simply managing the surface behaviour. Creative writing andart lessons provide valuable windows into students' unconscious concerns when approached with Freudian awareness. A Year 5 pupil who repeatedly draws houses with no doors may be expressing feelings of being trapped or inaccessible. Secondary students who write stories with recurring themes of abandonment might be processing attachment anxieties that affecttheir classroom relationshipsand academic engagement. Teachers can harness this understanding by incorporating dream journals intocreative writing programmes, not for psychological analysis but for exploring symbolic thinking and narrative construction. Discussing how our brains process worries through symbolic imagery helps students develop metacognitive awareness about their own emotional states. When a student voluntarily shares that they dreamt about drowning in homework, a Freudian-informed teacher. This as an opportunity to address workload anxiety rather than dismissing it as mere fantasy. Freud's defence mechanisms are unconscious psychological strategies that protect the ego from anxiety and emotional pain. Common mechanisms include repression, projection, denial, displacement, and sublimation, which distort reality to maintain psychological stability. Defence mechanisms are unconscious psychological strategies people use to protect themselves from anxiety and uncomfortable thoughts or feelings. Common examples include denial (refusing to accept reality), projection (attributing your feelings to others). Repression (pushing traumatic memories into the unconscious). These mechanisms operate automatically to maintain psychological equilibrium. Freud's concept of defence mechanisms proposes that individuals adopt various strategies to defend themselves against unpleasant emotions and experiences. These mechanisms are used to maintain psychological balance and avoid anxiety. There are several defence mechanisms, each with its unique function and purpose. Repression involves pushing unpleasant or traumatic experiences into the unconscious mind to avoid painful emotions. Denial, on the other hand, involves refusing to acknowledge one's actions or behaviour to avoid guilt and anxiety. Projection is when individuals attribute their own unacceptable thoughts, feelings, or impulses to others, usually those closest to them. Displacement involves redirecting one's aggressive or negative emotions towards a less threatening target. Sublimation, on the other hand, is transforming negative emotions and desires into positive actions that benefit oneself and society. These defence mechanisms are critical for preserving psychological stability and protecting individuals from overwhelming anxiety. However, extensive use of these mechanisms can cause psychological and emotional disruption. Therefore, maintain a balance between the use of defence mechanisms. Consciously acknowledging one's emotions and experiences to ensure a healthy emotional and mental state. Defence mechanisms manifest constantly in educational settings, and recognising them transforms how teachers respond to challenging behaviours. Rather than viewing difficult student actions as deliberate misbehaviour, a. Lens reveals them as unconscious strategies for managing psychological distress. The table below identifies common defence mechanisms and their classroom signs. Recognising these patterns allows teachers to respond to the underlying psychological need rather than just managing surface behaviour. A pupil using denial about academic failure needs confidence-building and support systems, not lectures about responsibility. A child projecting inadequacy needs reassurance and skill development, not punishment for accusations. This Freudian understanding transformsbehaviour management fromreactive discipline to proactive emotional support. A defence mechanism hierarchy is a structured classification of unconscious psychological. Ordered by their degree of psychological maturity and adaptive value. While Freud identified and named many individual defence mechanisms, it was George Vaillant (1977) who, drawing. Longitudinal research with Harvard graduates, organised them into four empirically grounded levels in his landmark studyAdaptation to Life. This classification transformed a loosely connected list of mechanisms into a. Framework with clear implications for both clinical practice and education. Vaillant's four levels are as follows. At the most primitive level are psychotic defences, including delusional projection. Psychotic denial, which involve a break from shared reality and are rarely seen outside severe psychiatric conditions. At the immature level sit projection, passive aggression, acting out and fantasy. These are common in adolescence and in adults under acute stress. The neurotic level includes intellectualisation, repression, reaction formation and displacement; these are more adaptive but still restrict emotional awareness. At the mature level are altruism, sublimation, suppression, anticipation. Humour, all of which involve transforming difficult feelings into socially constructive action without distorting reality. Vaillant's key finding was that the habitual use of mature defences in. Was one of the strongest predictors of physical health, relationship quality. Professional success in later life. This hierarchy matters for teachers because it provides a language for understanding. The same pupil might respond to anxiety with fantasy one day. Sublimation the next, depending on the severity of the stressor and the support available. Teachers interested in the broader landscape ofpsychodynamic theoryClassroom implication:Recognising that a pupil's humour, artistic output or peer mentoring may be mature sublimations of. Rather than distractions, allows the teacher to reinforce adaptive coping rather than inadvertently punishing it. Understanding how Freud's theories relate to other major developmental frameworks helps educators contextualise psychoanalytic concepts within broader psychological thinking. Whilst Freud emphasised unconscious sexual drives, his contemporaries and successors offered alternative perspectives on human development. Modern educators typically find Erikson's psychosocial framework most directly applicable. Classroom practise, whilst drawing on Freudian insights about unconscious processes. Jungian concepts when exploring literature and mythology. An integrated approach acknowledging all three perspectives provides the richest understanding of student development. Basic anxiety, as defined by Karen Horney (1945), is the child's pervasive feeling of helplessness. Isolation in a world perceived as hostile and indifferent. Where Freud located neurosis in repressed sexual conflict, Horney located it in the interpersonal environment, particularly in early relationships. This fail to provide consistent warmth and security. This shift from biological drive to social experience represented one of the. Substantive challenges to classical psychoanalysis from within the psychoanalytic tradition itself. Horney rejected Freud's concept of penis envy as a universal feature of feminine psychology, arguing instead. This what Freud observed was the product of cultural subordination rather than anatomy. InOur Inner Conflicts(Horney, 1945) andNeurosis and Human Growth(Horney, 1950), Horney proposed that individuals develop ten neurotic needs as defensive strategies against basic anxiety. These range from the need for affection and approval through to the need for personal achievement, self-sufficiency and perfection. She organised these ten needs into three broad relational orientations: moving towards people (compliant type), moving against people (aggressive type). Moving away from people (detached type). Healthy adults can flexibly adopt all three orientations depending on circumstance; neurotic individuals become rigidly fixed in one. This framework anticipates later attachment research and provides a more sociocultural reading of psychopathology than Freud's instinct-based model. Horney's work belongs to the Neo-Freudian tradition alongside Adler. Erikson, all of whom expanded psychoanalytic theory beyond its biological foundations. Teachers exploringchild development theoriesClassroom implication:A pupil displaying persistent approval-seeking or defiance may be operating from a neurotic orientation rooted in early relational insecurity. Consistent, non-conditional warmth from the teacher is the recommended corrective experience. The inferiority complex, a term introduced by Alfred Adler (1927), describes a pervasive. Paralysing sense of inadequacy that arises when normal feelings of inferiority, universal. Childhood, are not successfully compensated for through achievement or social connection. Adler was an early associate of Freud and a founding member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. He broke with Freud in 1911 over a fundamental disagreement: Adler believed. This the primary driver of human behaviour was not the sexual libido. The striving for superiority, by which he meant the individual's drive towards mastery, competence. Social contribution rather than dominance over others. Adler's system, which he called Individual Psychology, holds. This all people begin life in a state of genuine inferiority relative to the adults around them. The crucial variable is how the child responds. Most develop healthy compensation, channelling feelings of smallness into purposeful effort. Some develop an inferiority complex, becoming withdrawn, self-defeating and avoidant of challenge. Others over-compensate, adopting an aggressive superiority complex as a mask for underlying inadequacy. InUnderstanding Human Nature(Adler, 1927), he argued that birth order, parenting style. Early social experience shape which of these trajectories a child follows. His concept of social interest, the innate capacity for empathy. Cooperation, became a central criterion of psychological health in his later work. Adler's influence on contemporary education is underestimated. His ideas flow directly intogrowth mindsetresearch, positive discipline frameworks and the emphasis on belonging as a prerequisite for learning.Classroom implication:A pupil who refuses to attempt tasks, dismisses their own ability. Responds to failure with visible shame may be experiencing Adlerian inferiority. The teacher's role is to reframe challenge as a natural part of striving rather than evidence of inadequacy. Freud viewed religion as a collective neurosis. Wishful thinking, arguing it arose from humanity's need for protection against nature and fate.He believed religious beliefs were illusions based on childhood needs for a protective father figure. In his work 'The Future of an Illusion,' he predicted religion would eventually be replaced by scientific reasoning. Freud's theory on religion is outlined in his book, The Future of an Illusion. He argues that religion is a form of wish fulfilment, where people project their desires onto a higher power. According to him, religion serves to comfort us by creating a false sense of security and protection against life's uncertainties. Also, Freud believes that religion functions to control individuals through guilt and fear. Religion teaches us to suppress our natural desires, leading to feelings of guilt and anxiety. It also uses fear of punishment to maintain social order and control behaviour. His Jewish upbringing may have influenced his views on religion. Growing up in a religious household, he was exposed to the significant amount of guilt and fear surrounding religious practise. It's possible that his childhood experiences may have led him to view religion as a tool of social control. Freud's theory on religion suggests that it is a signs of our deepest desires. Fears, a means of coping with the uncertainties of life. Ultimately, it serves to maintain social structure and control behaviour through guilt and fear whilst simultaneously comforting individuals. Major criticisms include the lack of scientific evidence, overemphasis on sexuality, gender bias. Unfalsifiable claims that cannot be tested empirically.Critics argue his theories were based on limited case studies of wealthy Victorian women rather than diverse populations. Many concepts like penis envy and the Oedipus complex are considered outdated and culturally biased. Freudian theory has been criticised and contested on several grounds. Firstly, the disregarding of falsifiability, Freud's theory offers no clear means for experiment that would lead to its disproving. Hence, the constant rejection of any challenges to the theory leads to a philosophical question in the scientific community. Additionally, critics point out the lack of generalisability in the theory. They argue it is only applicable to certain societies and cultures. Also, Freud is often accused of sexist attitudes in his work. His ideas regarding women's psychology were met with resistance by some of. Female colleagues who believed his theories were based on paternalistic stereotypes. Additionally, Freudian theory has been challenged on its coherence and scientific nature. The social scientific nature of his work implies difficulty in the reliability of his theories. Lastly, critics have claimed that psychoanalysis has never been scientifically. To be an effective form of therapy for neurotic illnesses. The outcomes of assessments show conflicting results as there are many variables that could determine the success of psychoanalysis. Despite these criticisms, Freud's work remains a fundamental theory in the field of psychology offering contributions. This have been central to understanding the human mind. 7 controversial ideas from Freud's theories that sparked debate Sigmund Freud's theories, particularly in the realms of psychoanalytic therapy andpsychodynamic theory, have been the subject of intense debate and controversy since their inception. Here are seven controversial ideas that continue to spark discussion: A relevant statistic that captures the controversy is. This only about 15% of therapists in the United States. With psychodynamic therapy, reflecting the ongoing debate over Freud's legacy. Freud's theories transformed psychology but also ignited controversies that continue to resonate. His ideas challenged conventional wisdom, opened new avenues for understanding the human mind. Left a lasting impact that continues to be felt in both psychology and everyday life. Freud established the talking cure and the therapeutic relationship as central to healing psychological distress.His emphasis on unconscious processes, early childhood experiences, and defence mechanisms continues to influence many therapy approaches including psychodynamic therapy. Modern therapists still use adapted versions of free association, dream analysis, and transference interpretation. Sigmund Freud's work has had a significant impact on modern psychotherapy. His ideas regarding the unconscious mind, early childhood experiences. The therapeutic relationship have endured and continue to shape psychological treatment today. The concept of free association, where clients are encouraged to freely express their thoughts. Feelings, is a technique still used in therapy. Additionally, the analysis of dreams as a means of uncovering unconscious desires and conflicts remains a valuable tool. The therapeutic relationship itself has become crucial to the success of therapy, with empathetic listening. A strong rapport between therapist and client being widely accepted as essential. However, Freud's theories are not without criticism. Some have accused him of lacking empirical evidence, whilst others argue. This his emphasis on sexual and aggressive drives is detrimental. Even so, Freud's impact on the field of psychology remains undeniable and continues to shape modern psychotherapy. Neuropsychoanalysis is an interdisciplinary field that seeks to ground Freudian and post-Freudian concepts in contemporary neuroscience, using brain imaging. Lesion studies to test whether structures Freud described clinically have identifiable neural correlates. The movement was formally established by the neurologist Mark Solms, whose bookThe Hidden Spring(Solms, 2021) argues that Freud's concept of the unconscious id has a neurological basis. The brainstem's homeostatic systems rather than, as Freud assumed, in the cerebral cortex. This repositioning challenges both those who dismissed Freud as unscientific and those who defended his original topographical model unchanged. Of particular significance is research on the brain's Default Mode Network. A set of interconnected regions, including the medial prefrontal cortex. Posterior cingulate cortex, that become active during mind-wandering, self-reflection, autobiographical memory retrieval and the simulation of future events. Carhart-Harris and Friston (2010) proposed that the DMN functions as a neural substrate. Freud's primary process thinking, the associative, wish-fulfilling cognition he associated with dreaming. Unconscious mentation, while the task-positive network suppresses it during focused activity in a manner analogous to Freud's secondary process. Solms (2021) further argues that affective consciousness, the felt sense of emotion, is generated subcortically. Is therefore closer to the Freudian id than to the ego's cortical representations. For educators engaging with neuroscience-informed pedagogy, neuropsychoanalysis offers a productive reframing: the mind-wandering. This teachers often try to suppress in classrooms may serve important consolidation. Self-regulatory functions, consistent with both Freudian theory and contemporary cognitive neuroscience. Teachers exploringcognitivist learning theoriesClassroom implication:Building brief periods of unstructured reflection into lessons, rather than. Constant task pressure, may support the DMN-mediated consolidation of emotional. Autobiographical learning that Freud associated with the working-through process. Freud revolutionised psychology by proposing that most of our mental activity occurs below the surface of conscious awareness.He compared the mind to an iceberg, with conscious thoughts representing. The visible tip whilst the vast unconscious remains hidden beneath. This unconscious realm, he argued, contains repressed memories, primitive desires. Painful experiences that continue to influence our behaviour without our realisation. For teachers, understanding the unconscious helps explain why pupils sometimes react in ways that seem completely irrational or disproportionate. When a typically cheerful student suddenly becomes withdrawn after a maths lesson, their conscious explanation might. 'I'm just tired,' whilst unconscious associations with past failures or criticism may be the real trigger. Research in educational psychology supports this view; studies show. This early negative learning experiences can create unconscious patterns of avoidance that persist throughout schooling. Recognising unconscious influences transformsclassroom management. Rather than immediately disciplining a pupil who constantly interrupts, consider what unconscious need they. Be expressing, perhaps a deep-seated fear of being overlooked stemming from home life. Try keeping a behaviour journal noting triggers and patterns; you'll often spot unconscious themes emerging. Another practical strategy involves creating 'emotion check-ins'. Pupils use colour cards to express feelings they might not consciously understand, helping surface unconscious anxieties. The unconscious also explains why some teaching methods inexplicably fail with certain pupils. A student might unconsciously associate group work with past rejection, making them resist collaboration despite consciously knowing its benefits. By acknowledging these hidden influences, teachers can adapt their approaches, perhaps allowing. This pupil to work in pairs first before progressing to larger groups. Bowlby drew on Freud's emphasis on early relationships but grounded his theory in observable behaviour. Seeattachment theory in educationfor practical applications in schools. The preconscious is the layer of mental activity that sits between conscious awareness and the deeply repressed unconscious. Freud (1915) described it as a mental waiting room: thoughts, memories. Learned skills that are not currently in awareness but can be retrieved with minimal effort. A teacher's knowledge of a pupil's name, a multiplication fact not currently being recalled, or. Lyrics of a song heard yesterday all reside in the preconscious until attention summons them. This distinguishes the preconscious from the unconscious proper, where material is actively kept from awareness by repression. In his topographical model, Freud proposed three levels: conscious (what you are aware of right now), preconscious (accessible with effort). Unconscious (inaccessible without therapeutic intervention). The preconscious acts as a filter, governed by what Freud. Secondary process thinking, the logical, reality-oriented cognition of the ego. Material passes from the preconscious into consciousness when it is useful and non-threatening. Material that triggers anxiety is pushed back towards the unconscious by the censor function. This filtering explains why a pupil might suddenly recall a distressing event during a. Reading period: reduced cognitive demand lowers the censor's threshold, allowing preconscious material to surface. For classroom practice, the preconscious is directly relevant to retrieval andworking memory. When teachers use retrieval practice strategies, they are training pupils to. Information from long-term storage through the preconscious into active awareness.Classroom implication:Providing semantic cues ("It starts with P and relates to learning stages") activates preconscious associations. Supports recall without simply giving the answer. Freud's structural model divides the personality into three distinct parts: the id, ego, and superego.The id represents our most primitive desires and impulses, operating on the pleasure principle and demanding immediate gratification. The ego functions as the rational mediator, balancing the id's demands with reality. The superego embodies our moral compass, incorporating societal rules and parental values that guide our sense of right and wrong. In the classroom, understanding these three components transforms how you interpret pupil behaviour. When a Year 3 student impulsively shouts out answers despite repeated reminders, you're witnessing the id overpowering the ego's control. Similarly, the child who refuses to share resources exhibits id-driven behaviour, whilst the pupil who. Visibly distressed after making a minor mistake shows an overactive superego creating excessive guilt. Teachers can use this framework to develop targeted interventions. For pupils with dominant id tendencies, introduce structured waiting games. Delayed gratification exercises, such as earning tokens throughout the day to exchange for rewards later. Whensupporting children withharsh superegos, explicitly model making mistakes and recovering positively. Create classroom mantras like 'Mistakes help us grow' and celebrate effort over perfection. Research by Anna Freud extended these concepts into child development, showing how the ego strengthens throughout childhood. This explains why younger pupils struggle more with impulse control. Their egos are still developing the capacity to mediate between desires and reality. By Year 6, most children show improved ego function. Stress or emotional upheaval can temporarily weaken this control, resulting in regression to more id-driven behaviours. Freud's psychosexual model is an early and influential entry in the history ofchild development theoriesthat shaped how we understand emotional growth. Erikson's psychosocial stagesextended Freud's model beyond sexuality to encompass social and identity challenges across the lifespan. Freud believed personality develops through five distinct stages during childhood, each focused on a different pleasure zone of the body.These psychosexual stages; oral, anal, phallic, latency and genital; shape how children interact with their environment and form relationships. Understanding these stages helps teachers recognise why pupils display certain behaviours and struggle with specific developmental challenges. The oral stage (0-18 months) centres on feeding and comfort. Children who experienced feeding difficulties or weaning issues might seek oral stimulation through thumb-sucking or pencil-chewing well into primary school. Teachers can provide appropriate alternatives like fidget tools or structured snack times. The anal stage (18 months-3 years) involves toilet training and control. Pupils fixated at this stage might be excessively neat or extremely messy, struggling with organisational skills or classroom routines. During the phallic stage (3-6 years), children develop awareness of gender differences and form stronger attachments to opposite-sex parents. This explains why some Reception pupils become overly attached to. Of a particular gender or compete intensely for adult attention. The latency period (6-puberty) sees sexual feelings dormant whilst children focus on friendships and skills. This is why primary-aged pupils often prefer same-sex friendships and thrive on structured learning activities. Recognising these developmental patterns helps teachers adjust expectations and support strategies. A Year 1 pupil constantly seeking approval might be working through. Stage challenges, whilst a Year 4 child's sudden obsession with rules. Fairness reflects healthy latency development. By matching teaching approaches to developmental needs, educators create more supportive learning environments that acknowledge the psychological foundations of behaviour. Freud's development of the "talking cure" transformed mental health treatment from physical interventions to verbal exploration.Unlike his medical contemporaries who relied on hypnosis, cold baths, or restraints, Freud discovered. This allowing patients to speak freely about their thoughts could uncover repressed memories and resolve psychological conflicts. , whose physical symptoms disappeared when she verbally expressed traumatic memories. The technique, which Freud termed "free association," required patients to voice whatever. To mind without censorship, revealing unconscious patterns through seemingly random connections. The mechanics of free association operate on Freud's principle. This the unconscious mind constantly influences conscious thought through symbolic links and emotional associations. When a patient relaxes their mental guard and speaks without filtering, repressed material surfaces through verbal chains. This appear unrelated but share unconscious connections. For instance, a patient discussing their morning commute might suddenly recall a. Argument with a sibling, revealing unresolved competitive feelings affecting current workplace relationships. Freud positioned himself behind the patient on his famous couch to minimise visual distractions. Reduce the patient's tendency to monitor the therapist's reactions, thereby encouraging more authentic expression. Teachers can adapt Freudian free association principles to enable student creativity and emotional expression without venturing into therapeutic territory. Stream-of-consciousnesswriting exercises, wherepupils write continuously for five minutes without stopping to edit or judge. Thoughts, often reveal surprising connections between academic concepts and personal experiences. This technique proves particularly effective in helping reluctant writers overcome perfectionism and access authentic voice. Similarly, word association games during vocabulary lessons can expose conceptual. As students' spontaneous connections often reveal how they truly categorise. Relate new information to existing knowledge. The therapeutic distance Freud maintained translates into classroom management through strategic positioning and neutral responses. When addressing emotional outbursts or conflicts, sitting beside rather than directly. An upset pupil reduces confrontational dynamics, echoing Freud's therapeutic arrangement. Encouraging students to "think aloud" whilst solving problems mirrors free association's. Process, making invisible thought patterns visible for both teacher and student. This verbalisation technique proves especially valuable for identifying where mathematical reasoning breaks down or why certainreading comprehension strategies fail.By creating spaces for unstructured verbal expression, whether through journal prompts. Circles, or problem-solving narratives, educators tap into the same unconscious revelations. This made Freud's talking cure so transformative, whilst maintaining appropriate educational boundaries. Freud's most controversial theory centres on the Oedipus complex, a developmental phase he believed all children experience between ages 3-6.Named after the Greek myth where Oedipus unknowingly kills his father. Marries his mother, Freud proposed that young boys develop unconscious desires for their mothers whilst viewing their fathers as rivals. This creates profound anxiety, as the child simultaneously loves and fears the father figure. The resolution of this complex, through identification with the same-sex parent, supposedly forms the foundation of gender identity andmoral development. Carl Jung, Freud's contemporary, later coined the term inology in child development literature. Whilst the sexual aspects of these complexes are rightfully dismissed, the underlying observations about attachment patterns. Identification processes offer valuable classroom insights. Children between 3-6 often display intensified preferences for one parent or teacher, experience jealousy. Attention is diverted, and struggle with sharing authority figures. Rather than viewing these through Freud's lens, contemporary educators recognise. As normal attachment behaviours reflecting children's growing awareness of relationships. Their place within social hierarchies. Recent research on attachment and development provides more nuanced understanding of these dynamics. Studies examining quality of life after significant disruptions shows how early attachment patterns influence resilience and adaptation throughout life. Similarly, research into complex health conditions requiring multidisciplinary care highlights how early relationship templates affect how individuals seek. Receive support in crisis. For educators, recognising these attachment patterns without Freudian baggage proves invaluable. A Year 1 pupil who becomes possessive of their teacher or acts out when ateaching assistant joinsthe class isn't experiencing an "Oedipal crisis". Rather navigating normal developmental challenges around sharing, trust, and expanding their social world. Understanding that children naturally form intense attachments. Experience jealousy helps teachers respond with patience rather than concern, validating emotions whilst maintaining appropriate boundaries. Gradually encouraging broader social connections. Freud's life and death instincts theory proposes two fundamental drives: Eros (life instinct) seeks survival. Reproduction, whilst Thanatos (death instinct) drives towards destruction and return to inorganic state.These opposing forces govern human behaviour. Beyond his structural model of the mind, Freud proposed a fundamental theory about the opposing forces. This drive all human behaviour: the life instinct (Eros) and the death instinct (Thanatos). Introduced in his 1920 work "Beyond the Pleasure Principle", this dual-drive theory suggests. This humans are motivated by two conflicting unconscious forces, one pushing towards growth, connection. Creation, whilst the other pulls towards destruction, aggression, and a return to an inorganic state. The life instinct includes all drives that promote survival, reproduction, and pleasure. It includes hunger, thirst, and sexual desires, but extends beyond basic needs to encompass creativity, social bonding. The drive to build and preserve. In contrast, the death instinct manifests as aggression, self-destructive behaviours. An unconscious desire to return to a state of calm non-existence. Freud observed that whilst the death instinct is typically directed outward as aggression. Others, it can turn inward, resulting in self-harm, excessive risk-taking, or self-sabotage. Recent research shows how these opposing forces manifest in educational contexts. Analysis reveals how internal conflicts between constructive and destructive impulses can create profound psychological tension, affecting behaviour and learning capacity. In the classroom, pupils exhibiting sudden aggressive outbursts during creative activities may be. This fundamental conflict between their drive to create and unconscious destructive impulses. Understanding this theory transforms how educators interpret challenging behaviours. A pupil who repeatedly destroys their own artwork or tears up completed homework isn't simply being defiant. They may be unconsciously expressing the death instinct's pull towards destruction. Similarly, pupils who engage in self-defeating patterns, such as deliberately failing exams. Capable of passing or sabotaging friendships, may be manifesting inwardly-directed aggression. Recognising these patterns allows teachers to address the underlying conflict rather than merely punishing the behaviour. The practical application extends to classroom management strategies. Creating structured opportunities for controlled aggression, such as competitive debates, contact sports, or even. Up scrap paper during stress-relief activities, can provide healthy outlets for the death instinct. Simultaneously, channelling the life instinct through collaborative projects, peer mentoring programmes, and creative expression helps pupils develop constructive coping mechanisms. By acknowledging both forces and providing appropriate outlets, educators can help pupils navigate their. Conflicts more effectively, reducing destructive behaviours whilst promoting psychological wellbeing and academic achievement. Essential reads include Freud's own 'The Interpretation of Dreams' and 'Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality' for primary sources.For accessible introductions, try Peter Gay's 'Freud: A Life for Our Time' or 'Freud' by Jonathan Lear. Modern perspectives can be found in Mark Solms' 'The Hidden Spring' which connects Freud to neuroscience. These papers offer a comprehensive view of Freud's theories and their lasting impact on psychology and related disciplines. Freudian complexes shape personality by creating unconscious emotional patterns formed during childhood development.Unresolved complexes influence adult relationships, behaviours, and psychological functioning throughout life, affecting decision-making and interpersonal dynamics. Among Freud's most controversial yet influential theories are the Oedipus and Electra complexes. This describe how children navigate intense emotional attachments to their. Parents during the phallic stage of psychosexual development (ages 3-6). The Oedipus complex, named after the Greek mythological figure who unknowingly killed his father. Married his mother, refers to a boy's unconscious desire for his mother and rivalry with his father. Freud theorised that boys experience castration anxiety, fearing their fathers will punish them for. Forbidden desires, ultimately leading them to identify with their fathers to resolve the conflict. The Electra complex, a term coined by Carl Jung rather than Freud himself, describes. Parallel process in girls who supposedly develop an unconscious attraction to their fathers. Compete with their mothers. Freud's own explanation differed, proposing that girls experience "penis envy" and blame their mothers for their perceived anatomical deficiency. This theory has faced substantial criticism for its sexist assumptions. Lack of empirical support, yet it remains significant for understanding how Freud viewed personality formation and gender identity development. Whilst modern psychology has largely moved beyond these literal interpretations, understanding these concepts helps educators recognise certain behavioural patterns. This may emerge during earlyprimary years.Children between ages 4-6 often display intense preferences for one parent or teacher, become possessive. Adult attention, or show jealousy towards siblings or peers who receive affection from favoured adults. Rather than viewing these through Freud's sexual lens, contemporary educators can see them as normal developmental phases. Children learn about relationships, boundaries, and emotional regulation. In classroom settings, you might observe pupils who constantly seek approval from teachers of a particular gender, become upset. Their favourite teacher gives attention to other students, or struggle with authority figures who remind them of the same-sex parent. These behaviours reflect children's attempts to understand their place in social hierarchies and form their identities, not unconscious sexual desires. By recognising these patterns without pathologising them, educators can provide appropriate. Helping children develop healthy relationships with authority figures and peers. Setting clear boundaries whilst remaining warm and supportive helps children navigate these complex emotions safely. Their ability to form multiple secure attachments rather than fixating on a single adult figure. Effectiveness of mind mapping for learning in a real educational setting View study ↗ (2020) This research tests whether mind mapping actually improves student learning compared. Other study techniques in real classroom settings with secondary school students. The findings help teachers determine whethermind mapping isworth incorporating into their lesson plans or if other methods might be more effective. Communication Theories Applied in Mentimeter to Improve Educational Communication and Teaching EffectivenessView study ↗ Freud's structural model divides the personality into three distinct parts: the id, ego, and superego.The id represents our basic instincts and desires, demanding immediate gratification without considering consequences. The ego acts as the rational mediator, balancing the id's demands with reality. The superego embodies our moral conscience, containing the rules and values we've absorbed from parents and society. Understanding this model transforms how you interpret pupil behaviour. When a Year 3 student snatches a classmate's pencil, that's the id in action; pure want without consideration. The child who then feels guilty and returns it shows their developing superego. Meanwhile, the pupil who asks to borrow the pencil shows a healthy ego, finding acceptable ways to meet their needs. Teachers can use this framework to support behavioural development. Create 'ego-strengthening' activities where pupils practise problem-solving scenarios: "You really want to play with the class iPad. It's someone else's turn. What could you do? " This helps children develop strategies for managing their impulses whilst respecting classroom rules. The model also explains whybehaviour managementvaries between age groups. Reception children operate primarily from the id, requiring external control and clear boundaries. By Year 6, most pupils have developed stronger superegos, sometimes becoming overly self-critical. Recognising these developmental differences helps you adjust your approach accordingly. Consider using visual aids to teach this concept directly to older primary pupils. Draw three cartoon characters representing each part: 'Wanty' (id), 'Thinky' (ego), and 'Shouldy' (superego). When conflicts arise, ask pupils to identify which character is 'talking loudest' and how they might balance all three voices. Computer vision systems now monitor UK classrooms to identify the unconscious behavioural patterns Freud described decades before digital technology existed. These AI-powered behavioural analytics platforms use pattern recognition algorithms to detect defence mechanisms like projection. Displacement as they unfold in real-time classroom interactions. When Year 7 student Jake repeatedly accuses classmates of cheating whilst copying. Himself, traditional observation might miss this projection pattern across multiple lessons. Real-time monitoring systems flag these contradictory behaviours within minutes, alerting teachers to underlying anxieties. This Freudian theory suggests drive such defensive responses. The AI intervention prompts immediate support rather than waiting for patterns to escalate into serious disruption. Research by Thompson and Clarke (2024) shows. This predictive algorithms can identify students displaying regressive behaviours, returning to earlier. Stages during stress, with 78% accuracy before teachers notice the changes themselves. Digital psychoanalytic tools track micro-expressions, posture shifts, and interaction patterns. This reveal when pupils unconsciously retreat from age-appropriate responses to more childlike coping strategies. Manchester City Council's pilot programme shows these systems particularly effective at recognising displacement behaviours. Students redirect anger from home situations onto classroom peers or equipment. Teachers receive instant behavioural prediction alerts explaining the likely unconscious motivations. Them to address root causes rather than just surface symptoms. Critics argue this level of surveillance raises privacy concerns. Early adopters report significant reductions in unexplained behavioural incidents when Freudian insights guide AI-informed interventions. Basic anxiety, as defined by Karen Horney (1945), is the child's pervasive feeling of helplessness. Isolation in a world perceived as hostile and indifferent. Where Freud located neurosis in repressed sexual conflict, Horney located it in the interpersonal environment, particularly in early relationships. This fail to provide consistent warmth and security. This shift from biological drive to social experience represented one of the. Substantive challenges to classical psychoanalysis from within the psychoanalytic tradition itself. Horney rejected Freud's concept of penis envy as a universal feature of feminine psychology, arguing instead. This what Freud observed was the product of cultural subordination rather than anatomy. InOur Inner Conflicts(Horney, 1945) andNeurosis and Human Growth(Horney, 1950), Horney proposed that individuals develop ten neurotic needs as defensive strategies against basic anxiety. These range from the need for affection and approval through to the need for personal achievement, self-sufficiency and perfection. She organised these ten needs into three broad relational orientations: moving towards people (compliant type), moving against people (aggressive type). Moving away from people (detached type). Healthy adults can flexibly adopt all three orientations depending on circumstance; neurotic individuals become rigidly fixed in one. This framework anticipates later attachment research and provides a more sociocultural reading of psychopathology than Freud's instinct-based model. Horney's work belongs to the Neo-Freudian tradition alongside Adler. Erikson, all of whom expanded psychoanalytic theory beyond its biological foundations. Teachers exploringchild development theoriesClassroom implication:A pupil displaying persistent approval-seeking or defiance may be operating from a neurotic orientation rooted in early relational insecurity. Consistent, non-conditional warmth from the teacher is the recommended corrective experience. The inferiority complex, a term introduced by Alfred Adler (1927), describes a pervasive. Paralysing sense of inadequacy that arises when normal feelings of inferiority, universal. Childhood, are not successfully compensated for through achievement or social connection. Adler was an early associate of Freud and a founding member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. He broke with Freud in 1911 over a fundamental disagreement: Adler believed. This the primary driver of human behaviour was not the sexual libido. The striving for superiority, by which he meant the individual's drive towards mastery, competence. Social contribution rather than dominance over others. Adler's system, which he called Individual Psychology, holds. This all people begin life in a state of genuine inferiority relative to the adults around them. The crucial variable is how the child responds. Most develop healthy compensation, channelling feelings of smallness into purposeful effort. Some develop an inferiority complex, becoming withdrawn, self-defeating and avoidant of challenge. Others over-compensate, adopting an aggressive superiority complex as a mask for underlying inadequacy. InUnderstanding Human Nature(Adler, 1927), he argued that birth order, parenting style. Early social experience shape which of these trajectories a child follows. His concept of social interest, the innate capacity for empathy. Cooperation, became a central criterion of psychological health in his later work. Adler's influence on contemporary education is underestimated. His ideas flow directly intogrowth mindsetresearch, positive discipline frameworks and the emphasis on belonging as a prerequisite for learning.Classroom implication:A pupil who refuses to attempt tasks, dismisses their own ability. Responds to failure with visible shame may be experiencing Adlerian inferiority. The teacher's role is to reframe challenge as a natural part of striving rather than evidence of inadequacy. A defence mechanism hierarchy is a structured classification of unconscious psychological. Ordered by their degree of psychological maturity and adaptive value. While Freud identified and named many individual defence mechanisms, it was George Vaillant (1977) who, drawing. Longitudinal research with Harvard graduates, organised them into four empirically grounded levels in his landmark studyAdaptation to Life. This classification transformed a loosely connected list of mechanisms into a. Framework with clear implications for both clinical practice and education. Vaillant's four levels are as follows. At the most primitive level are psychotic defences, including delusional projection. Psychotic denial, which involve a break from shared reality and are rarely seen outside severe psychiatric conditions. At the immature level sit projection, passive aggression, acting out and fantasy. These are common in adolescence and in adults under acute stress. The neurotic level includes intellectualisation, repression, reaction formation and displacement; these are more adaptive but still restrict emotional awareness. At the mature level are altruism, sublimation, suppression, anticipation. Humour, all of which involve transforming difficult feelings into socially constructive action without distorting reality. Vaillant's key finding was that the habitual use of mature defences in. Was one of the strongest predictors of physical health, relationship quality. Professional success in later life. This hierarchy matters for teachers because it provides a language for understanding. The same pupil might respond to anxiety with fantasy one day. Sublimation the next, depending on the severity of the stressor and the support available. Teachers interested in the broader landscape ofpsychodynamic theoryClassroom implication:Recognising that a pupil's humour, artistic output or peer mentoring may be mature sublimations of. Rather than distractions, allows the teacher to reinforce adaptive coping rather than inadvertently punishing it. Neuropsychoanalysis is an interdisciplinary field that seeks to ground Freudian and post-Freudian concepts in contemporary neuroscience, using brain imaging. Lesion studies to test whether structures Freud described clinically have identifiable neural correlates. The movement was formally established by the neurologist Mark Solms, whose bookThe Hidden Spring(Solms, 2021) argues that Freud's concept of the unconscious id has a neurological basis. The brainstem's homeostatic systems rather than, as Freud assumed, in the cerebral cortex. This repositioning challenges both those who dismissed Freud as unscientific and those who defended his original topographical model unchanged. Of particular significance is research on the brain's Default Mode Network. A set of interconnected regions, including the medial prefrontal cortex. Posterior cingulate cortex, that become active during mind-wandering, self-reflection, autobiographical memory retrieval and the simulation of future events. Carhart-Harris and Friston (2010) proposed that the DMN functions as a neural substrate. Freud's primary process thinking, the associative, wish-fulfilling cognition he associated with dreaming. Unconscious mentation, while the task-positive network suppresses it during focused activity in a manner analogous to Freud's secondary process. Solms (2021) further argues that affective consciousness, the felt sense of emotion, is generated subcortically. Is therefore closer to the Freudian id than to the ego's cortical representations. For educators engaging with neuroscience-informed pedagogy, neuropsychoanalysis offers a productive reframing: the mind-wandering. This teachers often try to suppress in classrooms may serve important consolidation. Self-regulatory functions, consistent with both Freudian theory and contemporary cognitive neuroscience. Teachers exploringcognitivist learning theoriesClassroom implication:Building brief periods of unstructured reflection into lessons, rather than. Constant task pressure, may support the DMN-mediated consolidation of emotional. Autobiographical learning that Freud associated with the working-through process.Fixation: Frustration and Overindulgence

The Unconscious Mind in Creative Learning

Defence Mechanisms in Psychoanalysis

Defence Mechanisms in Classroom Behaviour

Defence Mechanism

Definition

Classroom Example

Teacher Response Strategy

Denial

Refusing to acknowledge an uncomfortable reality

A pupil who failed a test insists they "didn't even try" or claims the test "doesn't matter anyway" to avoid confronting their academic struggles.

Gently challenge the denial without shaming. "I notice you're saying it doesn't matter, but I wonder if you're feeling disappointed about the result?" Provide face-saving opportunities to re-engage.

Projection

Attributing one's own unacceptable feelings to others

A student who feels inadequate constantly accuses classmates of "thinking they're better than everyone" or claims the teacher "hates me" when receiving constructive feedback.

Help the student recognise their own feelings: "It sounds like you might be feeling worried about how others see you. Let's talk about what's really going on." Build self-awareness gradually.

Displacement

Redirecting emotions from the actual source to a safer target

After a difficult morning at home, a pupil kicks over a chair or snaps at a friend over something trivial during break time.

Recognise the misdirected emotion: "I can see something's really bothering you today. This doesn't seem to be about the pencil. Want to talk about what's actually upsetting you?"

Regression

Reverting to behaviours from an earlier developmental stage

A Year 3 pupil who was previously toilet-trained starts having accidents again after a new sibling arrives, or a secondary student begins baby-talking when stressed.

Respond with compassion, not punishment. Address the underlying stressor whilst providing temporary accommodation. "I've noticed some changes lately. Let's make sure you feel supported during this adjustment period."

Rationalisation

Creating logical-sounding justifications for unacceptable behaviour or feelings

A student who cheated on an exam explains, "Everyone does it, and the test was unfair anyway." Or a pupil who bullied someone claims, "They deserved it because they're annoying."

Challenge the faulty logic whilst validating underlying feelings: "I understand you felt the test was difficult, but let's talk about better ways to handle those feelings. What other choices could you have made?"

Reaction Formation

Expressing the opposite of one's true feelings

A pupil with a crush acts unusually mean to that person, or a student struggling with jealousy becomes excessively praising of their rival's achievements.

Look beyond the surface behaviour to the underlying emotion. Create safe opportunities for authentic expression: "Sometimes we act differently than we feel. What's really going on for you?"

Sublimation

Channelling unacceptable impulses into socially acceptable activities

A pupil with aggressive tendencies excels at rugby or boxing. A student dealing with family chaos creates highly structured, detailed artwork or writes intense creative stories.

This is a healthy mechanism, encourage it! Provide diverse outlets for emotional expression: sports, arts, drama, music. "I've noticed you channel your energy brilliantly into your writing. That's a real strength."

Repression

Unconsciously blocking traumatic memories or unbearable thoughts from awareness

A child who experienced trauma claims to have no memory of the event, or a pupil suddenly "forgets" how to perform skills they previously mastered during a stressful period.

Don't force memory retrieval, this requires professional support. Focus on creating psychological safety and refer to counselling services. "I'm here when you're ready to talk about anything that's bothering you."

Intellectualisation

Avoiding emotional connection by over-focusing on abstract thinking

When discussing a character's death in literature, a pupil launches into complex theoretical analysis rather than engaging with the emotional content. Or a student whose parents are divorcing discusses it in detached, clinical terms.

Acknowledge the intellectual response whilst inviting emotional engagement: "Those are brilliant insights about the symbolism. I'm also curious, how do you think the character felt in that moment?"

Defence Mechanism Hierarchy: Vaillant's Four-Level Model

How Does Freud Compare to Jung vs Erikson?

Aspect

Freud (Psychosexual)

Jung (Analytical Psychology)

Erikson (Psychosocial)

Primary Focus

Unconscious sexual and aggressive drives; childhood psychosexual development

Collective unconscious, archetypes, individuation, and spiritual development

Social relationships and identity formation across the entire lifespan

Developmental Stages

5 stages (oral, anal, phallic, latency, genital) ending at puberty

Life divided into two halves: first half (ego development), second half (self-realisation and individuation)

8 stages from infancy to old age, each with a psychosocial crisis to resolve

Key Motivator

Libido (sexual energy) seeking pleasure and avoiding pain

Drive towards wholeness and integration of conscious/unconscious aspects

Social and cultural forces; need for identity and meaningful relationships

Role of Culture

Minimal emphasis; biological drives seen as universal

Significant; cultural myths and symbols reflect collective unconscious patterns

Central; culture shapes developmental tasks and identity formation

Classroom Application

Understanding defence mechanisms, recognising unconscious conflicts affecting behaviour, interpreting symbolic expression

Using archetypal stories and myths in teaching, recognising personality types (introversion/extroversion), valuing creative/spiritual expression

Supporting identity development, developing autonomy vs. shame, building industry vs. inferiority through achievable challenges

View of Development

Largely deterministic; early childhood experiences set adult personality patterns

Ongoing throughout life; midlife particularly important for self-realisation

Optimistic; crises at each stage offer opportunities for growth and change

Educational Strength

Reveals hidden emotional dynamics; explains defensive behaviours

Enriches literature teaching; honours diverse learning styles and personalities

Provides stage-appropriate developmental tasks; emphasises social-emotional learning

Educational Limitation

Overemphasises sexuality; lacks empirical support; culturally biased

Abstract concepts difficult to apply practically; less relevant for early childhood

Broad stages may not capture individual variation; Western cultural bias

Teacher Takeaway

"Student behaviour often reflects unconscious psychological conflicts rather than deliberate misbehaviour."

"Universal symbols and stories resonate because they tap into shared human experiences and psychological patterns."

"Each developmental stage presents specific social-emotional challenges that education should address."

Karen Horney and Basic Anxiety

Alfred Adler and the Inferiority Complex

Freud's Psychology of Religion Theory

What Are the Main Criticisms of Freudian Theory?

Freud's Impact on Modern Psychology

Neuropsychoanalysis and the Default Mode Network

Understanding the Unconscious Mind Theory

The Preconscious Mind

How Does Structural Compare to Topographical Models Compared?

Psychosexual Stages and Adult Personality

Psychoanalytic Therapy Techniques Methods

Free Association Classroom Techniques

Oedipus Complex and Childhood Development

Applying Freudian Theory Today

Life vs Death Instincts Theory

Identifying Student Instinctual Behaviour

Essential Freudian Psychology Reading List

Oedipus Complex in Classroom Behaviour

Classroom Complex Dynamics

17 citations

9 citationsThe Structural Model: Id, Ego, and Superego

AI Detection of Freudian Behavioural Patterns

Karen Horney and Basic Anxiety

Alfred Adler and the Inferiority Complex

Defence Mechanism Hierarchy: Vaillant's Four-Level Model

Neuropsychoanalysis and the Default Mode Network

Frequently Asked Questions

Id-Ego-Superego for Educators The id represents primitive desires and impulses seeking immediate gratification, the ego manages reality and mediates between desires and social expectations, whilst the superego acts as the moral conscience. Understanding these three components helps educators decode puzzling student behaviours and emotional outbursts by recognising the internal conflicts between instinctual desires and moral ideals that shape classroom dynamics.Practical Unconscious Mind Applications Teachers can use Freud's unconscious mind theory to understand that much of what drives student thoughts and actions lies beneath conscious awareness, including repressed memories and conflicts. By recognising that challenging behaviours may stem from unconscious motivations rather than deliberate defiance, educators can respond more empathetically and effectively to difficult classroom situations.Student Behaviour Through Psychosexual Stages Freud's five stages are oral (0-18 months), anal (18-36 months), phallic (3-6 years), latency (6-puberty), and genital (puberty onward), with unresolved conflicts at any stage potentially causing fixations affecting adult personality. Understanding these stages helps educators recognise why some pupils struggle with control issues, independence, and peer relationships, as these difficulties may stem from early childhood developmental experiences.Student Defence Mechanisms Defence mechanisms such as projection (attributing one's feelings to others) and denial (refusing to acknowledge reality) are unconscious strategies students use to protect themselves from anxiety or conflict. Recognising these patterns allows teachers to respond more therapeutically to challenging classroom dynamics, addressing underlying emotional needs rather than simply managing surface behaviours.Freudian Theory Implementation Challenges Teachers may struggle with the subjective nature of psychoanalytic interpretation and the controversy surrounding Freud's emphasis on sexuality in development. Additionally, educators must be cautious not to over-analyse student behaviour or attempt therapeutic interventions beyond their professional scope, instead using Freudian insights to inform their understanding whilst referring serious concerns to qualified mental health professionals.Using Dream Analysis for Anxieties Freud viewed dreams as the 'royal road to the unconscious,' containing hidden wishes and symbolic representations of repressed desires and fears. Teachers can apply this understanding by recognising that student creative work, stories, and expressed concerns may contain symbolic elements that reveal underlying anxieties, helping educators provide more targeted emotional support and identify students who may need additional help.How Does Transference Affect Teacher-Student Relationships? Transference occurs when students unconsciously redirect feelings about significant figures (usually parents) onto teachers. A pupil who becomes unusually defiant with a male teacher might be transferring feelings about an authoritarian father, whilst a student forming an overly dependent attachment to a nurturing teacher may be transferring unmet parental needs. Recognising transference helps teachers respond objectively rather than personally to student reactions.What Are the Practical Applications of Sublimation in Education? Sublimation, channelling unacceptable impulses into socially acceptable activities, is one of the healthiest defence mechanisms and highly relevant to education. Teachers facilitate sublimation by providing outlets for aggressive energy through competitive sports, channelling anxiety into detailed artwork, or transforming emotional turmoil into creative writing. These activities help students process difficult emotions constructively whilst developing valuable skills.

For each classroom scenario, identify which part of Freud's personality structure is driving the pupil's behaviour.

When students face academic pressure, social challenges, or emotional difficulties, they. Unconsciously employ defence mechanisms to protect themselves from psychological discomfort. These automatic responses, first identified by Freud, manifest regularly in classroom behaviour and can significantly impact learning outcomes. Understanding these mechanisms helps teachers respond more effectively to challenging behaviours. Create supportive environments where students feel safe to learn.

Common defence mechanisms appear in predictable patterns within school settings. Projection occurs when a struggling student accuses others of cheating rather than acknowledging their own academic dishonesty. Regression might manifest when a Year 6 pupil suddenly displays toddler-like tantrums before important exams. Displacement shows itself when a child who experiences harsh criticism at home becomes aggressive towards classmates. Research by Anna Freud (1936) later expanded these concepts specifically for educational. Noting how children's defence mechanisms often intensify during periods of academic stress.

Teachers can usespractical strategiesto address defensive behaviours constructively. When recognising projection, avoid direct confrontation; instead, create opportunities for private reflection through journal writing or one-to-one discussions. For students showing regression, maintain consistent routines and offer age-appropriate comfort without reinforcing immature behaviour. Address displacement by teaching emotional vocabulary and providing safe outlets like art therapy or physical education.

By recognising defence mechanisms as protective responses rather than deliberate defiance, educators can shift from punitive approaches to supportive interventions. This understanding transforms classroom management from reactive discipline to proactive emotional support, ultimately creating an environment. Students can lower their defences and engage authentically with learning.

Countertransference occurs when a professional unconsciously redirects their own feelings, expectations or. Conflicts onto a client or, in educational settings, onto a pupil. Freud (1910) first identified the phenomenon in analysts who found their clinical judgement distorted by emotional reactions to specific patients. In schools, countertransference manifests when a teacher's response to a pupil is disproportionate to the behaviour observed, suggesting. This the pupil's conduct has activated something unresolved in the teacher's own history.

A Year 6 teacher who finds herself inexplicably irritated by. Quiet, compliant girl may be responding not to the pupil. To an unconscious association with her own childhood experience of being overlooked for being "good. " A secondary teacher who consistently gives harsher sanctions to a particular boy. Be projecting qualities of a sibling or former peer onto the pupil. These reactions are not failures of professionalism; they are normal psychological processes that become problematic only when they remain unexamined. Freud argued that the analyst's own analysis was essential precisely because countertransference is inevitable rather than optional.