Unconditional Positive Regard

Explore Unconditional Positive Regard, a key concept in person-centered therapy. Learn its role in fostering growth, self-esteem, and healthy relationships.

Explore Unconditional Positive Regard, a key concept in person-centered therapy. Learn its role in fostering growth, self-esteem, and healthy relationships.

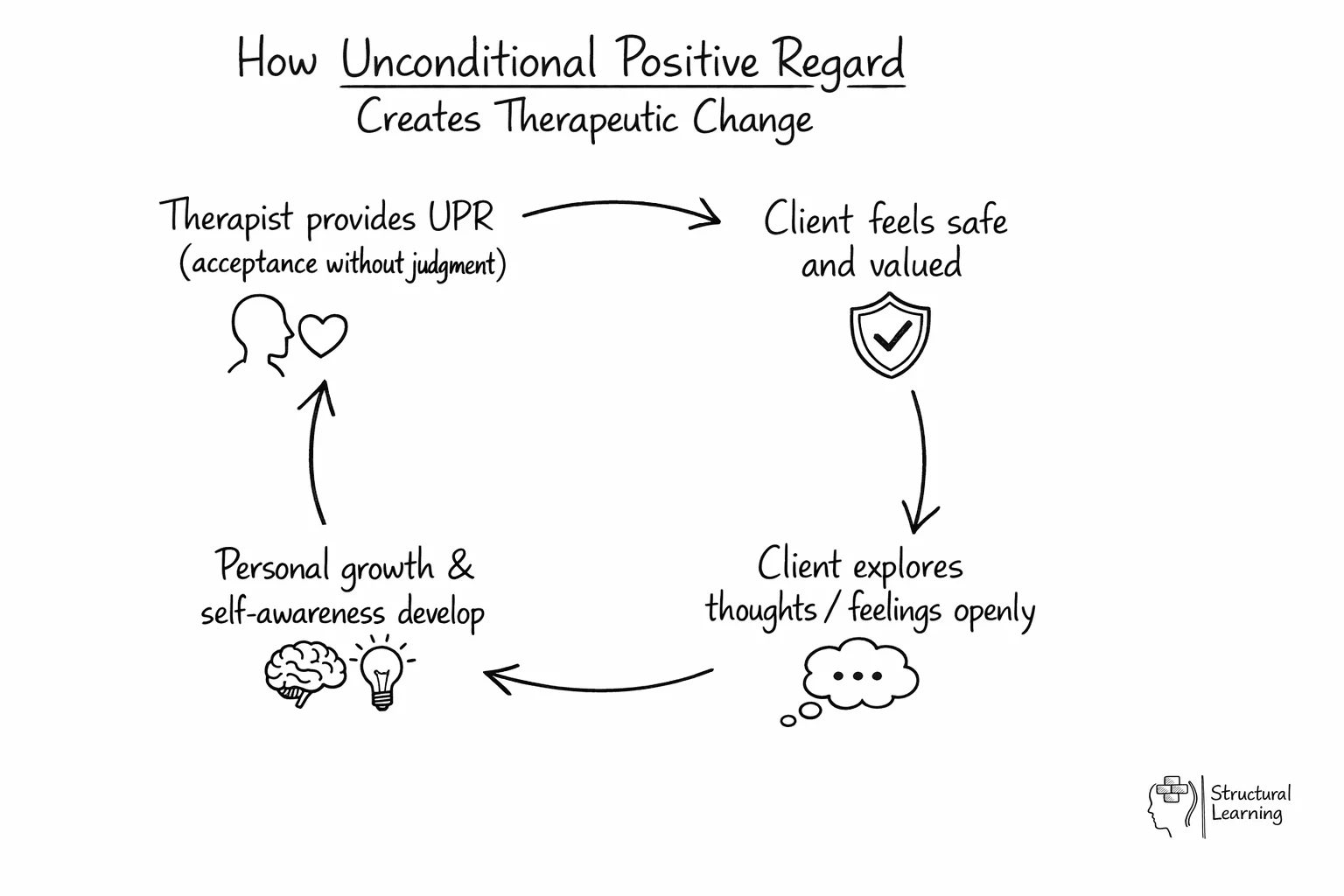

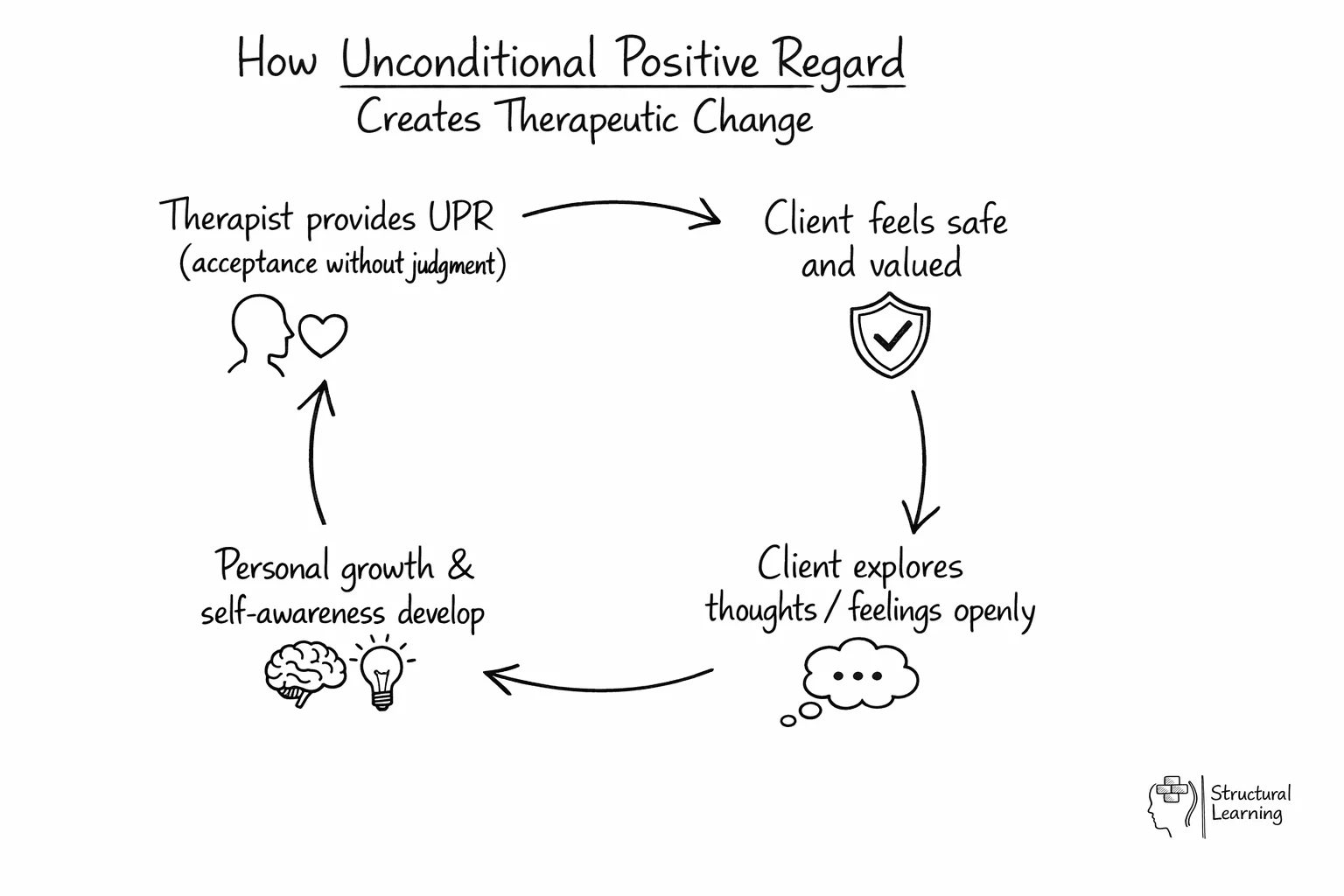

Unconditional Positive Regard (UPR) is a therapeutic approach where therapists accept and support clients without judgment, regardless of what they say or do. This concept, developed by Carl Rogers, creates a safe environment where clients feel valued and understood, enabling them to explore their thoughts and feelings openly. UPR forms the foundation of person-centered therapyand is considered essential for effective therapeutic relationships.

| Aspect | Conditional Positive Regard | Unconditional Positive Regard |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Acceptance and approval given only when certain conditions are met | Acceptance and approval given freely, regardless of behaviour or achievement |

| Message to Student | "I value you when you meet my expectations" | "I value you as a person, always" |

| Example Phrase | "I'm proud of you when you get good grades" | "I'm proud of the person you are and the effort you make" |

| Impact on Self-Worth | Student's self-worth depends on performance or behaviour | Student develops stable, internalized self-worth |

| Response to Mistakes | Mistakes threaten acceptance, causing anxiety and fear | Mistakes seen as learning opportunities, acceptance remains |

| Long-term Effects | Anxiety, perfectionism, fear of failure, external validation-seeking | Resilience, self-acceptance, intrinsic motivation, emotional security |

| In Classroom | Praise tied to results, conditional approval based on behaviour | Separate behaviour from person, consistent respect and warmth |

In the field of therapy and counselling, the concept of Unconditional Positive Regard (UPR) is a cornerstone, particularly within the framework of person-centered therapy.

This concept is a testament to the therapist's wholehearted attention and nonjudgmental attitude towards the client, which in turn, cultivates a therapeutic relationship that nurtures growth and personal development.

UPR is a vital element in therapy sessions, as it enables clients to feel understood, valued, and accepted for who they are. It signifies that irrespective of their actions, thoughts, or feelings, clients are inherently deserving of respect and compassion.

This acceptance paves the way for a safe and supportive environment where clients can explore and express themselves without any reservations.

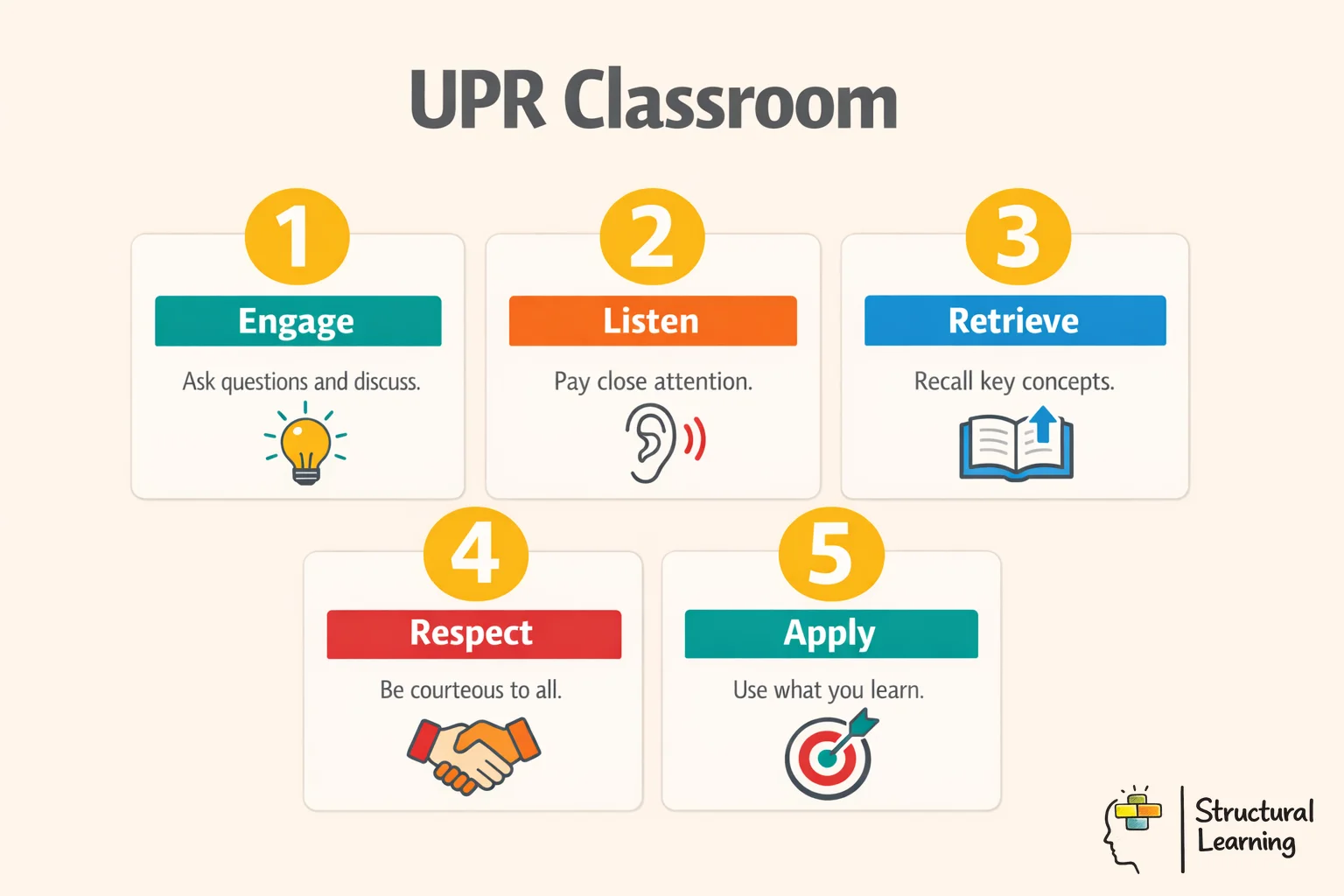

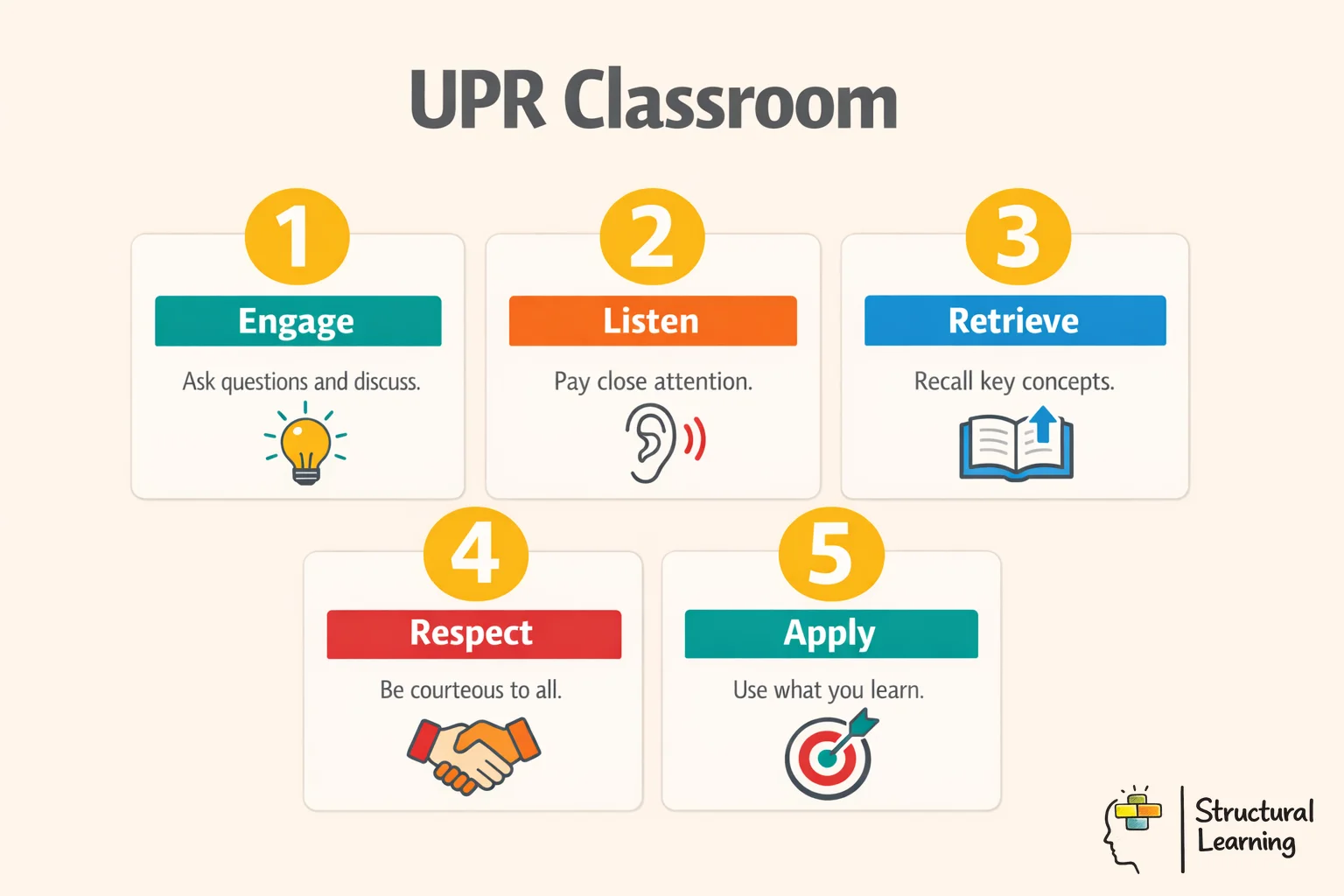

The principles of UPR extend beyond the confines of therapy and find application in various other settings, such as teaching. As educators, the practice of UPR allows us to offer unconditional acceptance to our students, regardless of their achievements or mistakes.

This approach creates a strong bond based on trust and emotional support, thereby enhancing social emotional learning in the classroom.

In a study titled "The positive psychology of relational depth and its association with unconditional positive self-regard and authenticity", it was found that higher scores on the relational depth inventory were associated with higher scores on the unconditional positive self-regard scale and the authenticity scale. This provides initial evidence for the growth-promoting effects of positive psychology approaches.

As educators, when we demonstrate UPR, we create an environment where students feel comfortable expressing themselves, asking questions, and taking risks.

By accepting individuals for who they are, without judgment or criticism, we can creates personal growth, encourage constructive behaviour, and create meaningful relationships that contribute to a positive school culture.

Key insights and important facts:

As the famous psychologist Carl Rogers once said, "The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change." This quote encapsulates the essence of UPR, reminding us of the transformative power of acceptance and the role it plays in personal development.

Carl Rogers developed the theory of Unconditional Positive Regard as a core component of his person-centered approach to therapy in the 1950s. Rogers believed that accepting clients without conditions or judgment was essentialfor creating a therapeutic environment where genuine healing and personal growth could occur. As a humanistic psychologist, Rogers challenged the dominant behavioural and psychoanalytic approaches of his time by emphasising the inherent worth and potential of every individual.

Rogers' groundbreaking work emerged from his belief that humans possess an innate tendency towards self-actualisation and positive growth, provided they experience the right conditions. He identified three core conditions necessary for therapeutic change: empathy, congruence (genuineness), and unconditional positive regard. Of these, UPR was considered fundamental because it creates the psychological safety needed for clients to explore their authentic selves without fear of rejection or judgment.

The development of Rogers' theory was influenced by his early experiences working with children and families, where he observed that clients seemed to flourish when treated with respect and acceptance rather than directive interpretation or behavioural modification. His approach transformed therapy by shifting focus from the therapist as expert to the client as the authority on their own experience.

Rogers' influence extended far beyond clinical practice. His person-centred principles have been applied across education, organisational development, and social work. In educational settings, teachers who embrace Rogers' philosophy create classrooms where students feel psychologically safe to take risks, make mistakes, and engage authentically with learning. This approach has proven particularly beneficial for supporting students with trauma histories or those who have experienced repeated academic failure.

Modern research in neuroscience and attachment theory has validated many of Rogers' intuitive insights about the importance of acceptance and safety in human development. Studies show that when individuals feel unconditionally accepted, their stress responses decrease, allowing higher-order thinking and emotional regulation to function more effectively. This neurobiological evidence supports Rogers' assertion that acceptance precedes change.

Implementing unconditional positive regard in educational settings requires a fundamental shift in how we view student behaviour and academic performance. Rather than seeing challenging behaviour as something to eliminate, UPR encourages educators to understand it as communication about unmet needs or underlying distress. This perspective transforms discipline from punitive to supportive, focusing on understanding rather than punishment.

Practical application begins with separating the person from the behaviour. When addressing inappropriate conduct, effective educators might say, "I care about you as a person, and I'm concerned about this choice you've made," rather than labelling the student as "naughty" or "transformative." This distinction helps maintain the student's sense of self-worth whilst addressing the behaviour that needs to change.

Creating classroom environments that embody UPR involves establishing routines and practices that consistently communicate acceptance. This includes greeting each student warmly regardless of previous day's behaviour, showing interest in their lives outside school, and responding to mistakes with curiosity rather than criticism. Teachers practicing UPR often use phrases like "Help me understand what happened" or "What do you think you need right now?" which invite collaboration rather than defensiveness.

For students with additional needs or those from disadvantaged backgrounds, UPR can be particularly transformative. These students often arrive at school having experienced conditional acceptance elsewhere, making them hypersensitive to signs of rejection or judgment. When teachers consistently demonstrate acceptance regardless of academic performance or social skills, these students can begin to develop the psychological safety necessary for learning and growth.

Assessment and feedback practices also require adjustment when implementing UPR. Rather than focusing solely on what students did wrong, feedback emphasises effort, progress, and learning process. Comments like "I can see you've been thinking deeply about this problem" or "Your willingness to try different approaches shows real growth" reinforce the student's worth whilst providing constructive guidance for improvement.

Despite its proven benefits, implementing unconditional positive regard often faces resistance due to common misconceptions. Many educators worry that accepting students unconditionally means lowering expectations or failing to address inappropriate behaviour. However, UPR does not mean permissiveness or avoiding accountability. Instead, it involves maintaining high expectations whilst providing unwavering support and acceptance of the individual.

One significant challenge is the natural human tendency to withdraw acceptance when faced with persistent challenging behaviour. Teachers may find themselves feeling frustrated or rejected by students who seem to resist their efforts. Practicing UPR requires emotional regulation and professional support, as educators must continue offering acceptance even when feeling personally challenged or triggered by student behaviour.

Cultural considerations also play a role in how UPR is understood and implemented. Some cultures emphasise collective harmony and conformity, which can create tension with the individualistic acceptance promoted by Rogers' approach. Effective implementation requires sensitivity to family values whilst maintaining core principles of respect and acceptance for each student's unique needs and personality.

Systemic barriers within educational institutions can also impede UPR implementation. Pressure for test scores, standardised curricula, and behaviour management policies based on punishment can conflict with person-centred approaches. School leaders who wish to creates UPR must examine policies and practices to ensure they align with principles of acceptance and support rather than conditional approval based solely on performance.

Training and ongoing professional development are essential for successful implementation. Teachers need opportunities to reflect on their own experiences of conditional and unconditional acceptance, understand the theoretical foundation of UPR, and practice specific techniques for maintaining acceptance during challenging moments. Reflective practice and peer support help educators develop the skills and mindset necessary for consistent implementation.

Unconditional positive regard represents more than just a therapeutic technique; it embodies a fundamental belief in human worth and potential that can transform educational relationships. When teachers consistently demonstrate acceptance and respect for students regardless of their behaviour or academic performance, they create conditions that facilitate genuine learning, emotional growth, and the development of healthy self-concept.

The evidence supporting UPR's effectiveness continues to grow, with research demonstrating its particular value for vulnerable students who have experienced trauma, rejection, or repeated failure. By providing the psychological safety that unconditional acceptance creates, educators enable students to take risks, engage authentically with learning, and develop the resilience necessary for lifelong success. As Carl Rogers recognised decades ago, the paradox remains true: when we accept students exactly as they are, we create the conditions that allow them to become who they're meant to be.

For educators committed to implementing UPR, the journey requires patience, self-reflection, and ongoing support. However, the transformation that occurs when students experience genuine acceptance makes this effort worthwhile. In a world where young people often face conditional approval based on performance and conformity, classrooms practicing unconditional positive regard become sanctuaries of acceptance that can fundamentally alter students' relationship with learning and their sense of self-worth.

For educators interested in exploring the research foundation behind unconditional positive regard and its applications in educational settings, the following academic sources provide valuable insights:

Unconditional Positive Regard (UPR) is a therapeutic approach where therapists accept and support clients without judgment, regardless of what they say or do. This concept, developed by Carl Rogers, creates a safe environment where clients feel valued and understood, enabling them to explore their thoughts and feelings openly. UPR forms the foundation of person-centered therapyand is considered essential for effective therapeutic relationships.

| Aspect | Conditional Positive Regard | Unconditional Positive Regard |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Acceptance and approval given only when certain conditions are met | Acceptance and approval given freely, regardless of behaviour or achievement |

| Message to Student | "I value you when you meet my expectations" | "I value you as a person, always" |

| Example Phrase | "I'm proud of you when you get good grades" | "I'm proud of the person you are and the effort you make" |

| Impact on Self-Worth | Student's self-worth depends on performance or behaviour | Student develops stable, internalized self-worth |

| Response to Mistakes | Mistakes threaten acceptance, causing anxiety and fear | Mistakes seen as learning opportunities, acceptance remains |

| Long-term Effects | Anxiety, perfectionism, fear of failure, external validation-seeking | Resilience, self-acceptance, intrinsic motivation, emotional security |

| In Classroom | Praise tied to results, conditional approval based on behaviour | Separate behaviour from person, consistent respect and warmth |

In the field of therapy and counselling, the concept of Unconditional Positive Regard (UPR) is a cornerstone, particularly within the framework of person-centered therapy.

This concept is a testament to the therapist's wholehearted attention and nonjudgmental attitude towards the client, which in turn, cultivates a therapeutic relationship that nurtures growth and personal development.

UPR is a vital element in therapy sessions, as it enables clients to feel understood, valued, and accepted for who they are. It signifies that irrespective of their actions, thoughts, or feelings, clients are inherently deserving of respect and compassion.

This acceptance paves the way for a safe and supportive environment where clients can explore and express themselves without any reservations.

The principles of UPR extend beyond the confines of therapy and find application in various other settings, such as teaching. As educators, the practice of UPR allows us to offer unconditional acceptance to our students, regardless of their achievements or mistakes.

This approach creates a strong bond based on trust and emotional support, thereby enhancing social emotional learning in the classroom.

In a study titled "The positive psychology of relational depth and its association with unconditional positive self-regard and authenticity", it was found that higher scores on the relational depth inventory were associated with higher scores on the unconditional positive self-regard scale and the authenticity scale. This provides initial evidence for the growth-promoting effects of positive psychology approaches.

As educators, when we demonstrate UPR, we create an environment where students feel comfortable expressing themselves, asking questions, and taking risks.

By accepting individuals for who they are, without judgment or criticism, we can creates personal growth, encourage constructive behaviour, and create meaningful relationships that contribute to a positive school culture.

Key insights and important facts:

As the famous psychologist Carl Rogers once said, "The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change." This quote encapsulates the essence of UPR, reminding us of the transformative power of acceptance and the role it plays in personal development.

Carl Rogers developed the theory of Unconditional Positive Regard as a core component of his person-centered approach to therapy in the 1950s. Rogers believed that accepting clients without conditions or judgment was essentialfor creating a therapeutic environment where genuine healing and personal growth could occur. As a humanistic psychologist, Rogers challenged the dominant behavioural and psychoanalytic approaches of his time by emphasising the inherent worth and potential of every individual.

Rogers' groundbreaking work emerged from his belief that humans possess an innate tendency towards self-actualisation and positive growth, provided they experience the right conditions. He identified three core conditions necessary for therapeutic change: empathy, congruence (genuineness), and unconditional positive regard. Of these, UPR was considered fundamental because it creates the psychological safety needed for clients to explore their authentic selves without fear of rejection or judgment.

The development of Rogers' theory was influenced by his early experiences working with children and families, where he observed that clients seemed to flourish when treated with respect and acceptance rather than directive interpretation or behavioural modification. His approach transformed therapy by shifting focus from the therapist as expert to the client as the authority on their own experience.

Rogers' influence extended far beyond clinical practice. His person-centred principles have been applied across education, organisational development, and social work. In educational settings, teachers who embrace Rogers' philosophy create classrooms where students feel psychologically safe to take risks, make mistakes, and engage authentically with learning. This approach has proven particularly beneficial for supporting students with trauma histories or those who have experienced repeated academic failure.

Modern research in neuroscience and attachment theory has validated many of Rogers' intuitive insights about the importance of acceptance and safety in human development. Studies show that when individuals feel unconditionally accepted, their stress responses decrease, allowing higher-order thinking and emotional regulation to function more effectively. This neurobiological evidence supports Rogers' assertion that acceptance precedes change.

Implementing unconditional positive regard in educational settings requires a fundamental shift in how we view student behaviour and academic performance. Rather than seeing challenging behaviour as something to eliminate, UPR encourages educators to understand it as communication about unmet needs or underlying distress. This perspective transforms discipline from punitive to supportive, focusing on understanding rather than punishment.

Practical application begins with separating the person from the behaviour. When addressing inappropriate conduct, effective educators might say, "I care about you as a person, and I'm concerned about this choice you've made," rather than labelling the student as "naughty" or "transformative." This distinction helps maintain the student's sense of self-worth whilst addressing the behaviour that needs to change.

Creating classroom environments that embody UPR involves establishing routines and practices that consistently communicate acceptance. This includes greeting each student warmly regardless of previous day's behaviour, showing interest in their lives outside school, and responding to mistakes with curiosity rather than criticism. Teachers practicing UPR often use phrases like "Help me understand what happened" or "What do you think you need right now?" which invite collaboration rather than defensiveness.

For students with additional needs or those from disadvantaged backgrounds, UPR can be particularly transformative. These students often arrive at school having experienced conditional acceptance elsewhere, making them hypersensitive to signs of rejection or judgment. When teachers consistently demonstrate acceptance regardless of academic performance or social skills, these students can begin to develop the psychological safety necessary for learning and growth.

Assessment and feedback practices also require adjustment when implementing UPR. Rather than focusing solely on what students did wrong, feedback emphasises effort, progress, and learning process. Comments like "I can see you've been thinking deeply about this problem" or "Your willingness to try different approaches shows real growth" reinforce the student's worth whilst providing constructive guidance for improvement.

Despite its proven benefits, implementing unconditional positive regard often faces resistance due to common misconceptions. Many educators worry that accepting students unconditionally means lowering expectations or failing to address inappropriate behaviour. However, UPR does not mean permissiveness or avoiding accountability. Instead, it involves maintaining high expectations whilst providing unwavering support and acceptance of the individual.

One significant challenge is the natural human tendency to withdraw acceptance when faced with persistent challenging behaviour. Teachers may find themselves feeling frustrated or rejected by students who seem to resist their efforts. Practicing UPR requires emotional regulation and professional support, as educators must continue offering acceptance even when feeling personally challenged or triggered by student behaviour.

Cultural considerations also play a role in how UPR is understood and implemented. Some cultures emphasise collective harmony and conformity, which can create tension with the individualistic acceptance promoted by Rogers' approach. Effective implementation requires sensitivity to family values whilst maintaining core principles of respect and acceptance for each student's unique needs and personality.

Systemic barriers within educational institutions can also impede UPR implementation. Pressure for test scores, standardised curricula, and behaviour management policies based on punishment can conflict with person-centred approaches. School leaders who wish to creates UPR must examine policies and practices to ensure they align with principles of acceptance and support rather than conditional approval based solely on performance.

Training and ongoing professional development are essential for successful implementation. Teachers need opportunities to reflect on their own experiences of conditional and unconditional acceptance, understand the theoretical foundation of UPR, and practice specific techniques for maintaining acceptance during challenging moments. Reflective practice and peer support help educators develop the skills and mindset necessary for consistent implementation.

Unconditional positive regard represents more than just a therapeutic technique; it embodies a fundamental belief in human worth and potential that can transform educational relationships. When teachers consistently demonstrate acceptance and respect for students regardless of their behaviour or academic performance, they create conditions that facilitate genuine learning, emotional growth, and the development of healthy self-concept.

The evidence supporting UPR's effectiveness continues to grow, with research demonstrating its particular value for vulnerable students who have experienced trauma, rejection, or repeated failure. By providing the psychological safety that unconditional acceptance creates, educators enable students to take risks, engage authentically with learning, and develop the resilience necessary for lifelong success. As Carl Rogers recognised decades ago, the paradox remains true: when we accept students exactly as they are, we create the conditions that allow them to become who they're meant to be.

For educators committed to implementing UPR, the journey requires patience, self-reflection, and ongoing support. However, the transformation that occurs when students experience genuine acceptance makes this effort worthwhile. In a world where young people often face conditional approval based on performance and conformity, classrooms practicing unconditional positive regard become sanctuaries of acceptance that can fundamentally alter students' relationship with learning and their sense of self-worth.

For educators interested in exploring the research foundation behind unconditional positive regard and its applications in educational settings, the following academic sources provide valuable insights:

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/unconditional-positive-regard#article","headline":"Unconditional Positive Regard","description":"Explore Unconditional Positive Regard, a key concept in person-centered therapy. Learn its role in encouraging growth, self-esteem, and healthy relationships.","datePublished":"2023-07-24T09:56:16.097Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/unconditional-positive-regard"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a27853e3da96360b97b2c_696a2781ee4adaeb0cd59ea2_unconditional-positive-regard-illustration.webp","wordCount":3212},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/unconditional-positive-regard#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Unconditional Positive Regard","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/unconditional-positive-regard"}]}]}