Executive Function in the Classroom

Explore how executive functioning skills impact classroom learning, with strategies to boost focus, organization, and student success.

Explore how executive functioning skills impact classroom learning, with strategies to boost focus, organization, and student success.

| Skill | Description | Classroom Challenge | Support Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Memory | Holding and manipulating information | Following multi-step instructions | Chunk information, provide reminders |

| Inhibitory Control | Suppressing impulses | Waiting turn, ignoring distractions | Teach self-talk, clear routines |

| Cognitive Flexibility | Shifting between tasks/perspectives | Transitioning, problem-solving | Prepare for transitions, model flexibility |

| Planning | Sequencing steps to goals | Long-term projects, time management | Break down tasks, use planners |

| Organisation | Managing materials and information | Keeping track of belongings, notes | Systems, checklists, designated spaces |

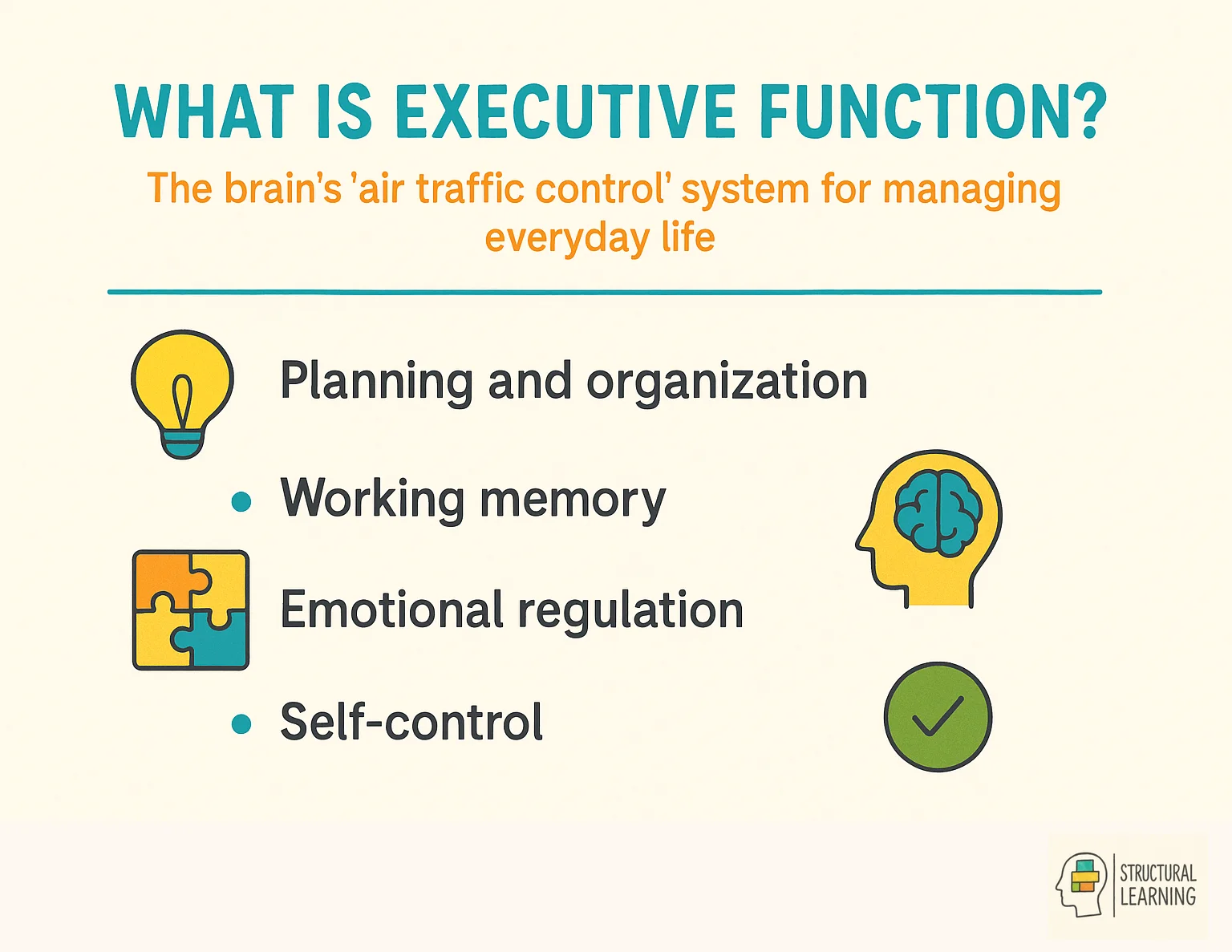

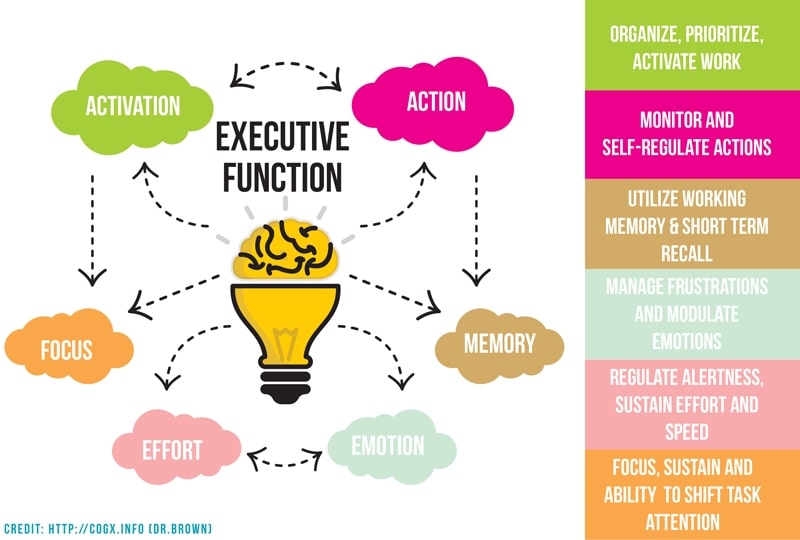

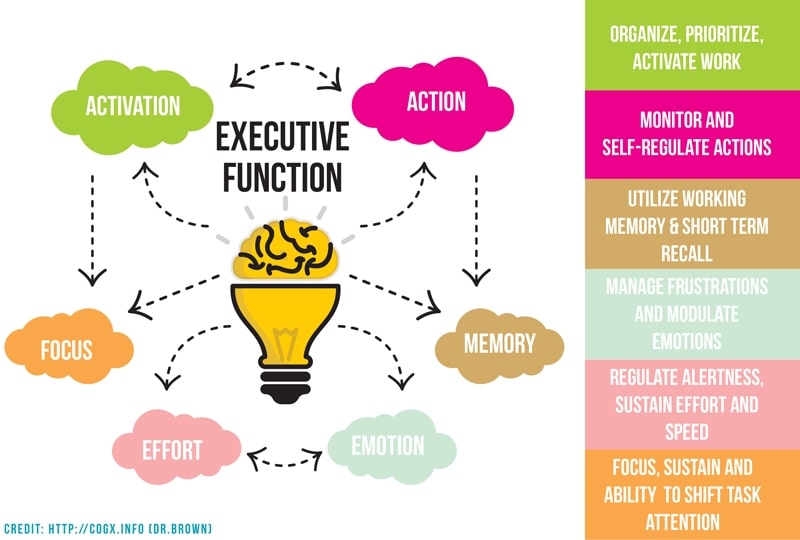

Executive Function (EF) consists of a number of different processes that help individuals to manage everyday life. The Harvard Center for the Developing Child likens EF to the body's 'air traffic control' system, where we plan, organise and manage ourselves.

Another way of looking at Executive Functioning is to compare it with a conductor and orchestra. The conductor of the orchestra or the air traffic controller organise and manage the musicians or the aeroplanes.

working memory, self-regulation, cognitive flexibility, and goal-oriented focus" loading="lazy">

working memory, self-regulation, cognitive flexibility, and goal-oriented focus" loading="lazy">

They both have a future goal: for the musicians to play the piece of music or for the aeroplanes to take off or land at a particular time and on a particular runway. The idea of Executive Functioning relates to carrying out a task where simply replying on intuition or gut instinct is not enough. Executive Function skills are needed when you have to concentrate and pay attention.

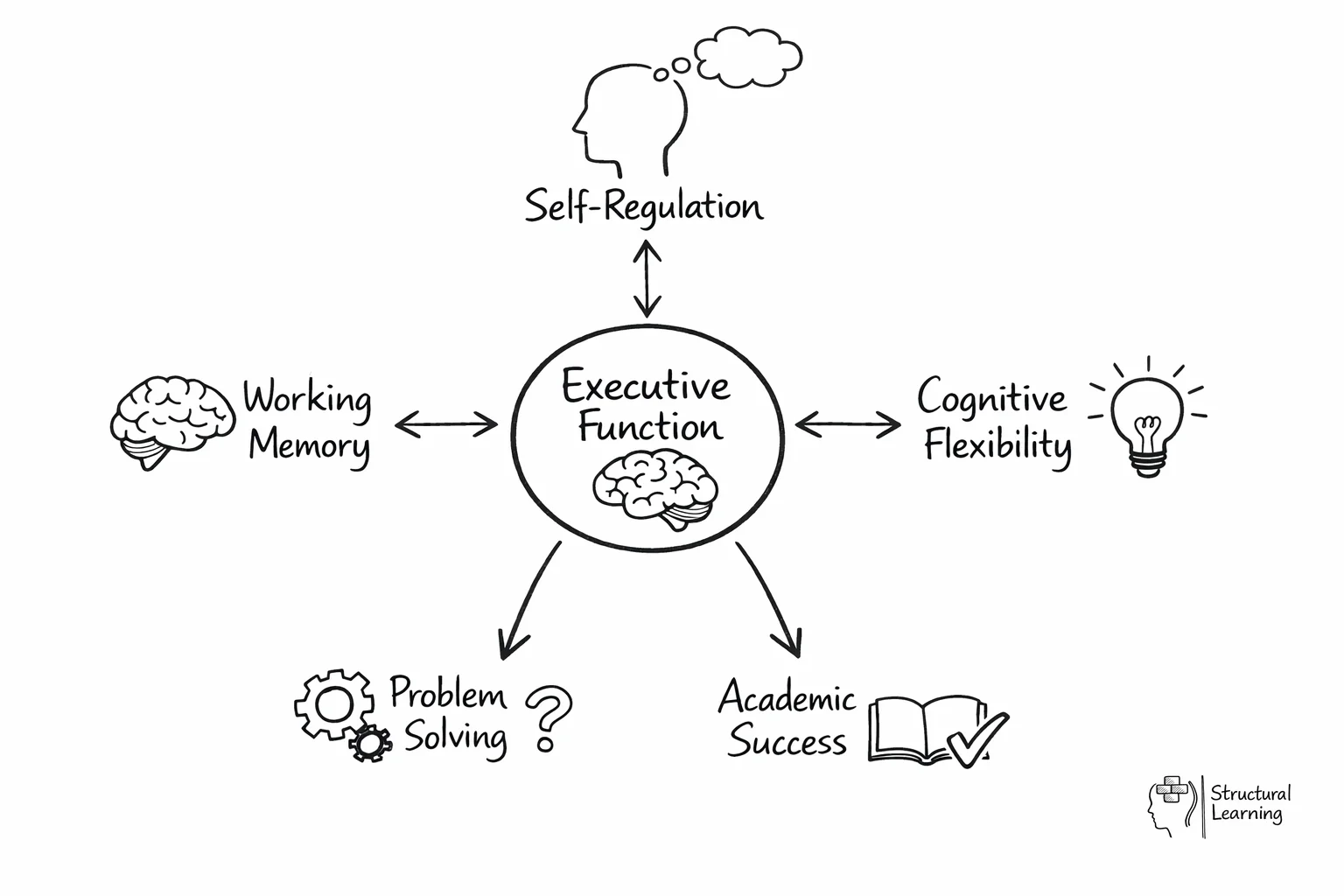

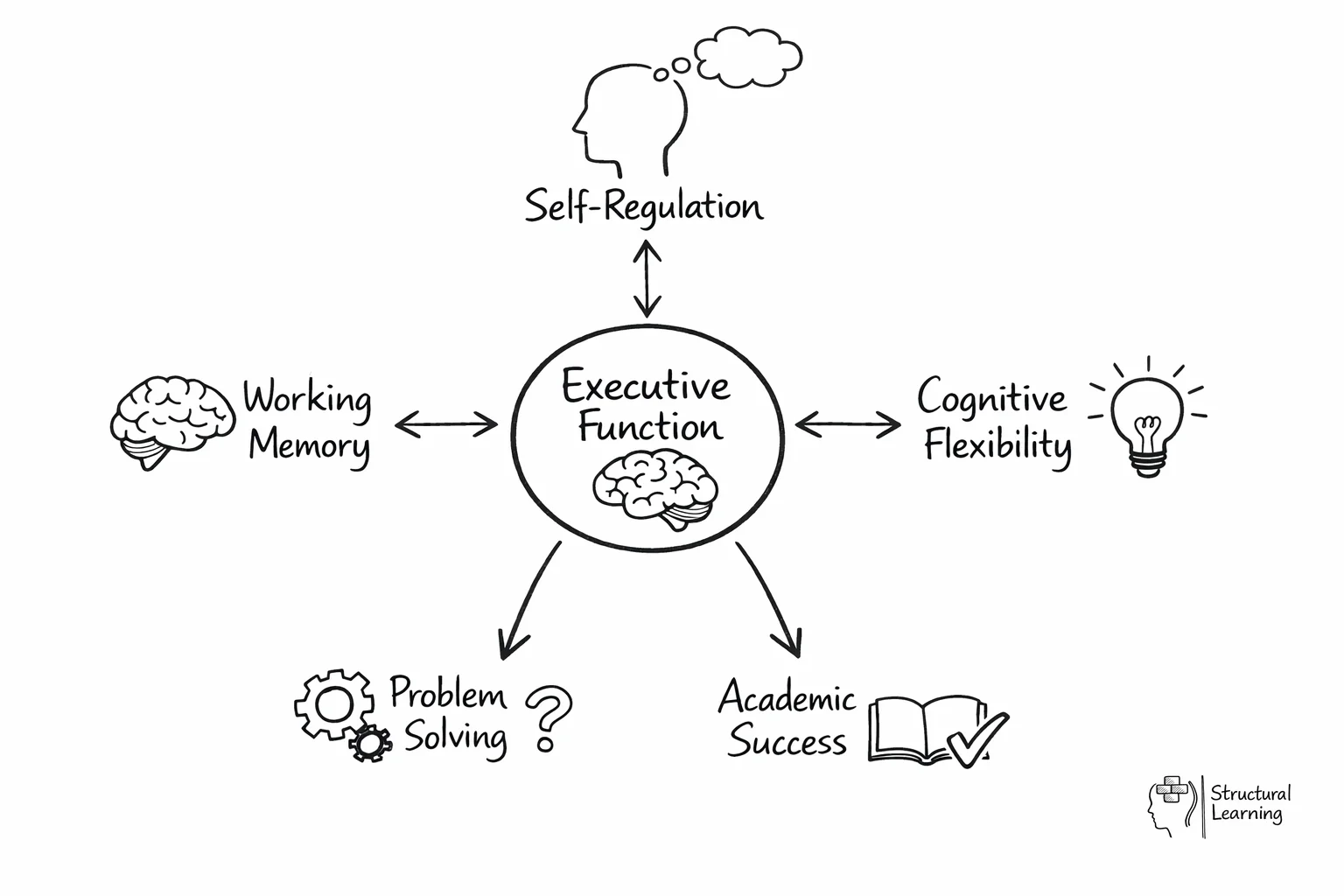

There is no one agreed definition of EF, but there is agreement about the three core areas that make up EF. Understanding executive function developmenthelps educators recognise how these skills emerge over time. These are working memory, self-regulation and cognitive flexibility. Working memory is about being able to hold information your head and manipulate that information.

Cognitive flexibility involves being able to adjust what you do, find another way to solve a problem or look at a problem. Seeing something from another's perspective involves cognitive flexibility. Thinking outside the box is another example. Cognitive flexibility involves using thinking skill in order to reason and solve problems.

Executive function includes several different types of cognitive functions, including attention, memory, planning, organisation, decision-making, self-control, and emotional regulation. These functions allow us to think logically and creatively while solving problems.

Cognitive flexibility manifests in the classroom when students successfully transition between different subjects, adapt their problem-solving approaches when initial strategies don't work, or adjust their behaviour based on changing classroom expectations. For instance, a student demonstrating strong cognitive flexibility might switch from using manipulatives in mathematics to mental calculation when the situation demands it, or adapt their writing style when moving from creative writing to formal essay composition.

Research by Dr Adele Diamond suggests that cognitive flexibility develops gradually throughout childhood and adolescence, with significant improvements occurring around ages 7-9 and again during the teenage years. Students with well-developed cognitive flexibility tend to be more resilient learners, better able to recover from mistakes, and more capable of seeing problems from multiple perspectives. They're also more likely to engage successfully with creative tasks and collaborative learning experiences.

Teachers can support cognitive flexibility development through classroom strategies that encourage mental shifting and adaptability. This includes providing opportunities for students to approach problems using different methods, introducing activities that require perspective-taking, and creating learning environments where mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities rather than failures. Simple practices such as asking students to explain their thinking in multiple ways or encouraging them to consider alternative solutions can significantly strengthen this crucial cognitive skill.

Self-regulation involves controlling your attention, behaviour, and thoughts. It is also sometimes referred to as inhibitory control. Can you press the override button or put the brakes on? Resisting temptation, delaying gratification.

The infamous Marshmallow test is a well-known experiment in Psychology that looked at self-regulation in children. It was carried out in 1972 at Stamford University with nursery-aged children. A child was put in room with a favourite treat (a marshmallow).

The child was told if they waited 15 minutes without eating the treat they could have a second treat. The researchers found that children who could wait for longer (so could delay gratification) had better outcomes in later life.

Later studies found more subtle differences, where the socio-economic status of the child was a factor. Self-regulation is a pre-requisite for cognitive flexibility since the individual has to attend to the task or problem and inhibit impulsive trial and error responding. Similarly, working memory would be challenged if the individual jumped in with an ill-thought-out response.

Teachers can promote executive function development by incorporating working memory exercises, self-regulation activities, and cognitive flexibility tasks into daily lessons. Strategies include using visual schedules, teaching students to break down complex tasks into steps, and practicing switching between different types of activities. Consistent routines and explicit instruction in planning and organisation skills are particularly effective. Effective classroom management supports these developmental processes.

think about EF as a set of skills. It is not a single concept such as the notion of g or general ability. However, there is some correlation between fluid intelligence and EF because fluid intelligence and EF involve similar abilities and processes: deductive anductive reasoning, problem-solving, and abstract thinking. Improving a child's executive function can have a huge impact on all aspects of their lives.

Specific classroom strategies can significantly enhance executive function development across all year groups. Break large assignments into smaller, manageable chunks with clear deadlines for each component. Provide students with planning templates and graphic organisers to scaffold their organisational skills. Research from the Harvard Center on the Developing Child demonstrates that these scaffolding techniques gradually build students' independent planning capabilities. Additionally, incorporate regular reflection activities where students evaluate their learning strategies and identify areas for improvement.

Working memory support is particularly crucial for academic success. Reduce cognitive loadby providing written instructions alongside verbal ones, and encourage students to use tools such as checklists and reminder systems. Educational research by Dr Tracey Alloway shows that targeted working memory interventions can improve academic outcomes across subjects. Teachers should also build in regular movement breaks and mindfulness activities, as these practices strengthen attention regulation and cognitive flexibility - core components of executive function that directly impact classroom learning and behaviour management.

Here are some practical strategies teachers can implement to support executive function development in the classroom:

By creating a structured and supportive learning environment, teachers can significantly enhance students' executive function skills, leading to improved academic performance and overall well-being.

Creating Supportive Classroom Environments: The physical and procedural environment plays a crucial role in supporting executive function development. Establish clear routines and consistent expectations that students can internalise over time. Use visual cues such as colour-coded folders for different subjects, designated spaces for materials, and posted daily schedules. Research demonstrates that predictable environments reduce cognitive load, allowing students to focus mental energy on learning rather than navigating uncertainty.

Scaffolding Independence: Gradually transfer responsibility from teacher to student through systematic scaffolding. Begin with high levels of support, such as providing completed examples and guided practice, then progressively reduce assistance as students demonstrate competence. This might involve moving from teacher-led checklists to student-created monitoring tools, or from structured group work to independent project management. The goal is building students' confidence in their own executive function abilities whilst ensuring they experience success throughout the learning process.

Assessment and Feedback Integration: Incorporate executive function assessment into regular classroom practice through observation checklists and student self-evaluations. Provide specific feedback about strategy use rather than just academic outcomes. For example, acknowledge when students successfully break down tasks or demonstrate improved time management, helping them recognise their growing executive function capabilities and understand the connection between strategy use and academic success.

Working memory serves as the mental workspace where students actively hold and manipulate information whilst completing learning tasks. Unlike long-term memory, which stores vast amounts of information indefinitely, working memory has limited capacity and duration, typically holding just three to five pieces of information for 15-30 seconds without rehearsal. This cognitive bottleneck significantly impacts how students process new material, follow multi-step instructions, and engage in complex reasoning tasks across all subject areas.

John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that when working memory becomes overloaded, learning effectiveness diminishes rapidly. Students may appear inattentive or struggle to follow directions, but often the real issue lies in overwhelming their working memory capacity. This is particularly evident during tasks requiring simultaneous processing, such as mental arithmetic whilst listening to instructions, or note-taking during lectures where students must listen, comprehend, summarise, and write concurrently.

Teachers can support working memory through strategic classroom modifications: breaking complex instructions into smaller chunks, providing visual aids to supplement verbal information, and allowing adequate processing time between steps. Simple adjustments like writing key points on the board whilst speaking, or using graphic organisers to structure information, can dramatically improve student comprehension and task completion across diverse learning needs.

Inhibitory control serves as the cognitive 'brake system' that enables students to resist impulses, maintain focus, and regulate their behaviour in classroom settings. This executive function allows learners to suppress automatic responses in favour of more thoughtful, goal-directed actions. Barkley's research demonstrates that students with well-developed inhibitory control can better resist distractions, wait their turn during discussions, and persist with challenging tasks rather than abandoning them when frustration mounts.

The classroom applications of inhibitory control extend far beyond basic behaviour management. Students must constantly inhibit competing responses: stopping themselves from calling out answers, resisting the urge to fidget during instruction, and suppressing irrelevant thoughts during focused work time. Diamond's work highlights how inhibitory control underpins academic skills such as proofreading, where students must override their natural tendency to read what they intended to write rather than what actually appears on the page.

Teachers can strengthen students' inhibitory control through structured practice and environmental design. Simple strategies include implementing clear stop-and-think routines, using visual cues to remind students to pause before responding, and creating 'impulse control challenges' such as the classic marshmallow test adapted for classroom contexts. Reducing environmental distractions and establishing predictable routines further supports students whose inhibitory control systems are still developing.

Executive function skills develop along a predictable trajectory, with significant variations in timing and capacity across different age groups. Research by Adele Diamond demonstrates that whilst basic inhibitory control emerges in early childhood, complex executive functions like cognitive flexibility and working memory continue developing well into the mid-twenties. Understanding these developmental milestones helps teachers set realistic expectations and avoid frustration when students struggle with age-inappropriate demands.

In primary years (ages 5-11), children typically develop foundational skills such as following simple multi-step instructions and basic self-regulation, though they still require substantial scaffolding. Secondary students (ages 11-16) show improved planning abilities and can handle more complex tasks, yet still benefit from explicit organisation strategies and regular check-ins. Russell Barkley's research emphasises that adolescents' executive functions remain vulnerable under stress, making supportive classroom environments particularly crucial during this period.

Effective classroom practice involves graduated responsibility, where teachers initially provide extensive support before gradually transferring ownership to students. For younger learners, this might mean visual schedules and frequent reminders, whilst older students benefit from goal-setting frameworks and reflection opportunities. Teachers should celebrate incremental progress rather than expecting immediate mastery, recognising that executive function development requires consistent practice within appropriately challenging contexts.

Students with executive function challenges require targeted accommodations that address their specific cognitive processing needs. Research by Russell Barkley demonstrates that traditional classroom expectations often exceed the developmental capacity of students with conditions such as ADHD, requiring educators to modify both instruction and assessment methods. These learners benefit from explicit teaching of organisational strategies, including visual schedules, task breakdowns, and regular check-in points throughout lessons.

Effective classroom support involves reducing cognitive load whilst building executive skills gradually. Working memory limitations mean these students struggle with multi-step instructions, making it essential to present information in smaller, sequential chunks with visual supports. Simple accommodations such as providing written instructions alongside verbal ones, offering movement breaks, and using timers for transitions can significantly improve academic outcomes without compromising learning objectives.

The most successful interventions focus on scaffolding independence rather than creating dependency. Teachers should explicitly model planning strategies, provide structured templates for organising work, and establish predictable routines that reduce anxiety. Regular collaboration with support staff and families ensures consistent approaches across environments, helping students generalise executive function skills beyond the classroom setting.

Executive function skills are fundamental for academic success and life-long learning. By understanding the core components of executive function, working memory, self-regulation, and cognitive flexibility, teachers can implement targeted strategies to support students' development in these crucial areas.

Creating a classroom environment that promotes planning, organisation, and self-awareness will helps students to become more effective and independent learners. Remember that executive function skills develop over time, and consistent support and practice are key to developing these abilities in all students.

The evidence clearly demonstrates that investing in executive function development yields significant benefits for student achievement and wellbeing. Schools that prioritise these cognitive skills report improved academic outcomes, reduced behavioural incidents, and enhanced student engagement across all key stages. However, successful implementation requires sustained commitment from leadership teams, adequate professional development for staff, and regular monitoring of student progress through appropriate assessment tools.

Going forward, educational professionals must advocate for executive function support to become embedded within curriculum planning and school policies. This means allocating time for explicit strategy teaching, creating classroom environments that reduce cognitive load, and establishing clear routines that scaffold student independence. Consider starting with small-scale interventions in specific subjects before expanding successful approaches across the whole school community.

The imperative is clear: executive function skills are not optional extras but essential foundations for lifelong learning. By taking action today to implement research-informed strategies, educators can transform their students' capacity to learn, adapt, and thrive in an increasingly complex world.

Here are some relevant research papers for further exploration of executive function:

| Skill | Description | Classroom Challenge | Support Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Memory | Holding and manipulating information | Following multi-step instructions | Chunk information, provide reminders |

| Inhibitory Control | Suppressing impulses | Waiting turn, ignoring distractions | Teach self-talk, clear routines |

| Cognitive Flexibility | Shifting between tasks/perspectives | Transitioning, problem-solving | Prepare for transitions, model flexibility |

| Planning | Sequencing steps to goals | Long-term projects, time management | Break down tasks, use planners |

| Organisation | Managing materials and information | Keeping track of belongings, notes | Systems, checklists, designated spaces |

Executive Function (EF) consists of a number of different processes that help individuals to manage everyday life. The Harvard Center for the Developing Child likens EF to the body's 'air traffic control' system, where we plan, organise and manage ourselves.

Another way of looking at Executive Functioning is to compare it with a conductor and orchestra. The conductor of the orchestra or the air traffic controller organise and manage the musicians or the aeroplanes.

working memory, self-regulation, cognitive flexibility, and goal-oriented focus" loading="lazy">

working memory, self-regulation, cognitive flexibility, and goal-oriented focus" loading="lazy">

They both have a future goal: for the musicians to play the piece of music or for the aeroplanes to take off or land at a particular time and on a particular runway. The idea of Executive Functioning relates to carrying out a task where simply replying on intuition or gut instinct is not enough. Executive Function skills are needed when you have to concentrate and pay attention.

There is no one agreed definition of EF, but there is agreement about the three core areas that make up EF. Understanding executive function developmenthelps educators recognise how these skills emerge over time. These are working memory, self-regulation and cognitive flexibility. Working memory is about being able to hold information your head and manipulate that information.

Cognitive flexibility involves being able to adjust what you do, find another way to solve a problem or look at a problem. Seeing something from another's perspective involves cognitive flexibility. Thinking outside the box is another example. Cognitive flexibility involves using thinking skill in order to reason and solve problems.

Executive function includes several different types of cognitive functions, including attention, memory, planning, organisation, decision-making, self-control, and emotional regulation. These functions allow us to think logically and creatively while solving problems.

Cognitive flexibility manifests in the classroom when students successfully transition between different subjects, adapt their problem-solving approaches when initial strategies don't work, or adjust their behaviour based on changing classroom expectations. For instance, a student demonstrating strong cognitive flexibility might switch from using manipulatives in mathematics to mental calculation when the situation demands it, or adapt their writing style when moving from creative writing to formal essay composition.

Research by Dr Adele Diamond suggests that cognitive flexibility develops gradually throughout childhood and adolescence, with significant improvements occurring around ages 7-9 and again during the teenage years. Students with well-developed cognitive flexibility tend to be more resilient learners, better able to recover from mistakes, and more capable of seeing problems from multiple perspectives. They're also more likely to engage successfully with creative tasks and collaborative learning experiences.

Teachers can support cognitive flexibility development through classroom strategies that encourage mental shifting and adaptability. This includes providing opportunities for students to approach problems using different methods, introducing activities that require perspective-taking, and creating learning environments where mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities rather than failures. Simple practices such as asking students to explain their thinking in multiple ways or encouraging them to consider alternative solutions can significantly strengthen this crucial cognitive skill.

Self-regulation involves controlling your attention, behaviour, and thoughts. It is also sometimes referred to as inhibitory control. Can you press the override button or put the brakes on? Resisting temptation, delaying gratification.

The infamous Marshmallow test is a well-known experiment in Psychology that looked at self-regulation in children. It was carried out in 1972 at Stamford University with nursery-aged children. A child was put in room with a favourite treat (a marshmallow).

The child was told if they waited 15 minutes without eating the treat they could have a second treat. The researchers found that children who could wait for longer (so could delay gratification) had better outcomes in later life.

Later studies found more subtle differences, where the socio-economic status of the child was a factor. Self-regulation is a pre-requisite for cognitive flexibility since the individual has to attend to the task or problem and inhibit impulsive trial and error responding. Similarly, working memory would be challenged if the individual jumped in with an ill-thought-out response.

Teachers can promote executive function development by incorporating working memory exercises, self-regulation activities, and cognitive flexibility tasks into daily lessons. Strategies include using visual schedules, teaching students to break down complex tasks into steps, and practicing switching between different types of activities. Consistent routines and explicit instruction in planning and organisation skills are particularly effective. Effective classroom management supports these developmental processes.

think about EF as a set of skills. It is not a single concept such as the notion of g or general ability. However, there is some correlation between fluid intelligence and EF because fluid intelligence and EF involve similar abilities and processes: deductive anductive reasoning, problem-solving, and abstract thinking. Improving a child's executive function can have a huge impact on all aspects of their lives.

Specific classroom strategies can significantly enhance executive function development across all year groups. Break large assignments into smaller, manageable chunks with clear deadlines for each component. Provide students with planning templates and graphic organisers to scaffold their organisational skills. Research from the Harvard Center on the Developing Child demonstrates that these scaffolding techniques gradually build students' independent planning capabilities. Additionally, incorporate regular reflection activities where students evaluate their learning strategies and identify areas for improvement.

Working memory support is particularly crucial for academic success. Reduce cognitive loadby providing written instructions alongside verbal ones, and encourage students to use tools such as checklists and reminder systems. Educational research by Dr Tracey Alloway shows that targeted working memory interventions can improve academic outcomes across subjects. Teachers should also build in regular movement breaks and mindfulness activities, as these practices strengthen attention regulation and cognitive flexibility - core components of executive function that directly impact classroom learning and behaviour management.

Here are some practical strategies teachers can implement to support executive function development in the classroom:

By creating a structured and supportive learning environment, teachers can significantly enhance students' executive function skills, leading to improved academic performance and overall well-being.

Creating Supportive Classroom Environments: The physical and procedural environment plays a crucial role in supporting executive function development. Establish clear routines and consistent expectations that students can internalise over time. Use visual cues such as colour-coded folders for different subjects, designated spaces for materials, and posted daily schedules. Research demonstrates that predictable environments reduce cognitive load, allowing students to focus mental energy on learning rather than navigating uncertainty.

Scaffolding Independence: Gradually transfer responsibility from teacher to student through systematic scaffolding. Begin with high levels of support, such as providing completed examples and guided practice, then progressively reduce assistance as students demonstrate competence. This might involve moving from teacher-led checklists to student-created monitoring tools, or from structured group work to independent project management. The goal is building students' confidence in their own executive function abilities whilst ensuring they experience success throughout the learning process.

Assessment and Feedback Integration: Incorporate executive function assessment into regular classroom practice through observation checklists and student self-evaluations. Provide specific feedback about strategy use rather than just academic outcomes. For example, acknowledge when students successfully break down tasks or demonstrate improved time management, helping them recognise their growing executive function capabilities and understand the connection between strategy use and academic success.

Working memory serves as the mental workspace where students actively hold and manipulate information whilst completing learning tasks. Unlike long-term memory, which stores vast amounts of information indefinitely, working memory has limited capacity and duration, typically holding just three to five pieces of information for 15-30 seconds without rehearsal. This cognitive bottleneck significantly impacts how students process new material, follow multi-step instructions, and engage in complex reasoning tasks across all subject areas.

John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that when working memory becomes overloaded, learning effectiveness diminishes rapidly. Students may appear inattentive or struggle to follow directions, but often the real issue lies in overwhelming their working memory capacity. This is particularly evident during tasks requiring simultaneous processing, such as mental arithmetic whilst listening to instructions, or note-taking during lectures where students must listen, comprehend, summarise, and write concurrently.

Teachers can support working memory through strategic classroom modifications: breaking complex instructions into smaller chunks, providing visual aids to supplement verbal information, and allowing adequate processing time between steps. Simple adjustments like writing key points on the board whilst speaking, or using graphic organisers to structure information, can dramatically improve student comprehension and task completion across diverse learning needs.

Inhibitory control serves as the cognitive 'brake system' that enables students to resist impulses, maintain focus, and regulate their behaviour in classroom settings. This executive function allows learners to suppress automatic responses in favour of more thoughtful, goal-directed actions. Barkley's research demonstrates that students with well-developed inhibitory control can better resist distractions, wait their turn during discussions, and persist with challenging tasks rather than abandoning them when frustration mounts.

The classroom applications of inhibitory control extend far beyond basic behaviour management. Students must constantly inhibit competing responses: stopping themselves from calling out answers, resisting the urge to fidget during instruction, and suppressing irrelevant thoughts during focused work time. Diamond's work highlights how inhibitory control underpins academic skills such as proofreading, where students must override their natural tendency to read what they intended to write rather than what actually appears on the page.

Teachers can strengthen students' inhibitory control through structured practice and environmental design. Simple strategies include implementing clear stop-and-think routines, using visual cues to remind students to pause before responding, and creating 'impulse control challenges' such as the classic marshmallow test adapted for classroom contexts. Reducing environmental distractions and establishing predictable routines further supports students whose inhibitory control systems are still developing.

Executive function skills develop along a predictable trajectory, with significant variations in timing and capacity across different age groups. Research by Adele Diamond demonstrates that whilst basic inhibitory control emerges in early childhood, complex executive functions like cognitive flexibility and working memory continue developing well into the mid-twenties. Understanding these developmental milestones helps teachers set realistic expectations and avoid frustration when students struggle with age-inappropriate demands.

In primary years (ages 5-11), children typically develop foundational skills such as following simple multi-step instructions and basic self-regulation, though they still require substantial scaffolding. Secondary students (ages 11-16) show improved planning abilities and can handle more complex tasks, yet still benefit from explicit organisation strategies and regular check-ins. Russell Barkley's research emphasises that adolescents' executive functions remain vulnerable under stress, making supportive classroom environments particularly crucial during this period.

Effective classroom practice involves graduated responsibility, where teachers initially provide extensive support before gradually transferring ownership to students. For younger learners, this might mean visual schedules and frequent reminders, whilst older students benefit from goal-setting frameworks and reflection opportunities. Teachers should celebrate incremental progress rather than expecting immediate mastery, recognising that executive function development requires consistent practice within appropriately challenging contexts.

Students with executive function challenges require targeted accommodations that address their specific cognitive processing needs. Research by Russell Barkley demonstrates that traditional classroom expectations often exceed the developmental capacity of students with conditions such as ADHD, requiring educators to modify both instruction and assessment methods. These learners benefit from explicit teaching of organisational strategies, including visual schedules, task breakdowns, and regular check-in points throughout lessons.

Effective classroom support involves reducing cognitive load whilst building executive skills gradually. Working memory limitations mean these students struggle with multi-step instructions, making it essential to present information in smaller, sequential chunks with visual supports. Simple accommodations such as providing written instructions alongside verbal ones, offering movement breaks, and using timers for transitions can significantly improve academic outcomes without compromising learning objectives.

The most successful interventions focus on scaffolding independence rather than creating dependency. Teachers should explicitly model planning strategies, provide structured templates for organising work, and establish predictable routines that reduce anxiety. Regular collaboration with support staff and families ensures consistent approaches across environments, helping students generalise executive function skills beyond the classroom setting.

Executive function skills are fundamental for academic success and life-long learning. By understanding the core components of executive function, working memory, self-regulation, and cognitive flexibility, teachers can implement targeted strategies to support students' development in these crucial areas.

Creating a classroom environment that promotes planning, organisation, and self-awareness will helps students to become more effective and independent learners. Remember that executive function skills develop over time, and consistent support and practice are key to developing these abilities in all students.

The evidence clearly demonstrates that investing in executive function development yields significant benefits for student achievement and wellbeing. Schools that prioritise these cognitive skills report improved academic outcomes, reduced behavioural incidents, and enhanced student engagement across all key stages. However, successful implementation requires sustained commitment from leadership teams, adequate professional development for staff, and regular monitoring of student progress through appropriate assessment tools.

Going forward, educational professionals must advocate for executive function support to become embedded within curriculum planning and school policies. This means allocating time for explicit strategy teaching, creating classroom environments that reduce cognitive load, and establishing clear routines that scaffold student independence. Consider starting with small-scale interventions in specific subjects before expanding successful approaches across the whole school community.

The imperative is clear: executive function skills are not optional extras but essential foundations for lifelong learning. By taking action today to implement research-informed strategies, educators can transform their students' capacity to learn, adapt, and thrive in an increasingly complex world.

Here are some relevant research papers for further exploration of executive function:

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/executive-function#article","headline":"Executive Function in the Classroom","description":"Explore how executive functioning skills impact classroom learning, with strategies to boost focus, organization, and student success.","datePublished":"2022-12-12T11:59:28.408Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/executive-function"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/695261d1840063529d718d61_695261cfb4e8a5bbe26d725f_executive-function-infographic.webp","wordCount":3083},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/executive-function#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Executive Function in the Classroom","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/executive-function"}]}]}