The Attainment Gap: Understanding and Closing

Examine the factors contributing to the attainment gap and implement evidence-based strategies to enhance educational equity for all students.

The attainment gap represents one of education's most persistent challenges. Understanding its causes and implementing evidence-based strategies can help schools support all learners effectively.

| Examples (This IS the Attainment Gap) | Non-Examples (This is NOT the Attainment Gap) |

|---|---|

| Students on free school meals achieving significantly lower GCSE grades than their peers, a measurable difference between demographic groups | Individual students performing differently due to personal effort or interest, not systematic group differences |

| Children from low-income areas reading at significantly lower levels than peers from affluent areas, showing systematic educational disparities | A single school having varying test scores across different subjects, this is curriculum variation, not demographic disparity |

| SEND students consistently scoring substantially below school averages across multiple schools, pattern-based inequality | One student struggling with math while excelling in English, individual learning differences, not group-based gaps |

| Schools in deprived areas having substantially fewer students achieving university entry requirements compared to affluent areas, systemic achievement differences | Teachers having different teaching styles that students respond to differently, pedagogical preferences, not educational inequality |

The attainment gap describes the difference in educational achievement between subgroups of students. These disparities typically emerge along lines of socioeconomic status, ethnicity, gender, and special educational needs. For UK state schools, this metric has become central to accountability frameworks.

Schools receiving funding must demonstrate how specific activities help disadvantaged pupil progress. Education providers need clear evidence showing how they advance opportunities for society's most vulnerable learners. The Education Endowment Foundation provides schools with research-backed approaches, including active learning approaches, that can significantly impact children's educational trajectories.

The pandemic amplified existing inequalities. Learning loss during school closures hit children from disadvantaged backgrounds hardest, revealing schools' transformative potential. Academic activities coordinated in school settings, supported by effective curriculum design, help students overcome barriers they would otherwise face without targeted support. Differences in cultural capital between families also contribute to these educational disparities.

The attainment gap manifests differently across educational stages and subjects. In primary schools, gaps often emerge early in literacy and numeracy, with some children entering Year 1 already 19 months behind their peers in language development. These early disparities tend to compound over time, creating what researchers call the 'Matthew effect' - where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer academically.

At secondary level, the gap becomes particularly pronounced in GCSE outcomes. For instance, pupils eligible for free school meals achieve grade 4 or above in English and maths at rates consistently 20-30 percentage points lower than their more advantaged peers. The gap extends beyond academic subjects, affecting participation in enrichment activities, university applications, and career aspirations. Understanding these nuances helps educators recognise that closing the attainment gap requires sustained, targeted intervention throughout a child's educational journey.

Recognising the attainment gap in practice requires looking beyond headline data to examine patterns within your own setting. Teachers might notice that disadvantaged pupils are more likely to arrive at school without breakfast, have fewer opportunities for homework support at home, or show reluctance to participate in class discussions. School leaders often observe these pupils are underrepresented in higher sets, extracurricular activities, or leadership roles. By identifying these everyday manifestations of educational inequality, educators can implement evidence-based approaches such as quality-first teaching, strategic use of pupil premium funding, and partnerships with families to create meaningful change.

The Department for Education defines the attainment gap as the persistent difference in educational outcomes between pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds and their peers. In practice, 'disadvantaged' is most commonly operationalised through eligibility for free school meals (FSM): a proxy measure that captures household income below a threshold tied to benefits entitlement. The FSM proxy is administratively convenient and widely used, but it has known limitations. It captures a snapshot of current poverty rather than a history of deprivation, and it excludes many pupils who are in low-income households but do not qualify. Researchers routinely note that the gap between FSM and non-FSM pupils represents the lower bound of the true disadvantage gap.

The Education Policy Institute tracks attainment differences across key stages using the Disadvantage Gap Index (DGI), a composite measure that combines attainment data from Early Years through to the end of secondary school. Hutchinson et al. (2019) published a landmark EPI analysis showing that, at age 16, disadvantaged pupils in England were on average 18.1 months of learning behind their peers. The gap was not uniform: it was widest in coastal towns and post-industrial areas of the North and Midlands, and narrowest in Inner London, where decades of sustained investment and a high density of high-performing schools had made measurable inroads. At Key Stage 2, the gap was smaller but still substantial, with disadvantaged pupils around nine months behind by the end of primary school.

Regional variation matters because it complicates any single national policy response. A school in a deprived coastal community faces a different combination of challenges from a school in an urban area with high immigration and strong community networks. The EPI analysis also tracks the gap over time. Progress was made between 2007 and 2017, with the gap at age 16 narrowing by roughly five months over a decade. That progress stalled after 2017, and the disruption caused by school closures during 2020 and 2021 reversed gains made at every key stage. By 2022, the gap at age 16 had widened to levels not seen since 2012.

For teachers, the measurement debate has a practical implication. When schools use FSM as their sole identifier of disadvantage, they risk missing a substantial group of pupils who are quietly falling behind. The Pupil Premium funding mechanism is tied to FSM eligibility and looked-after children status, but good practice goes further. Schools that track attainment by postcode, family mobility, and prior attainment history tend to identify a wider range of pupils who would benefit from targeted support. The DGI is useful for benchmarking; the harder work is building the classroom-level picture that the national index cannot provide.

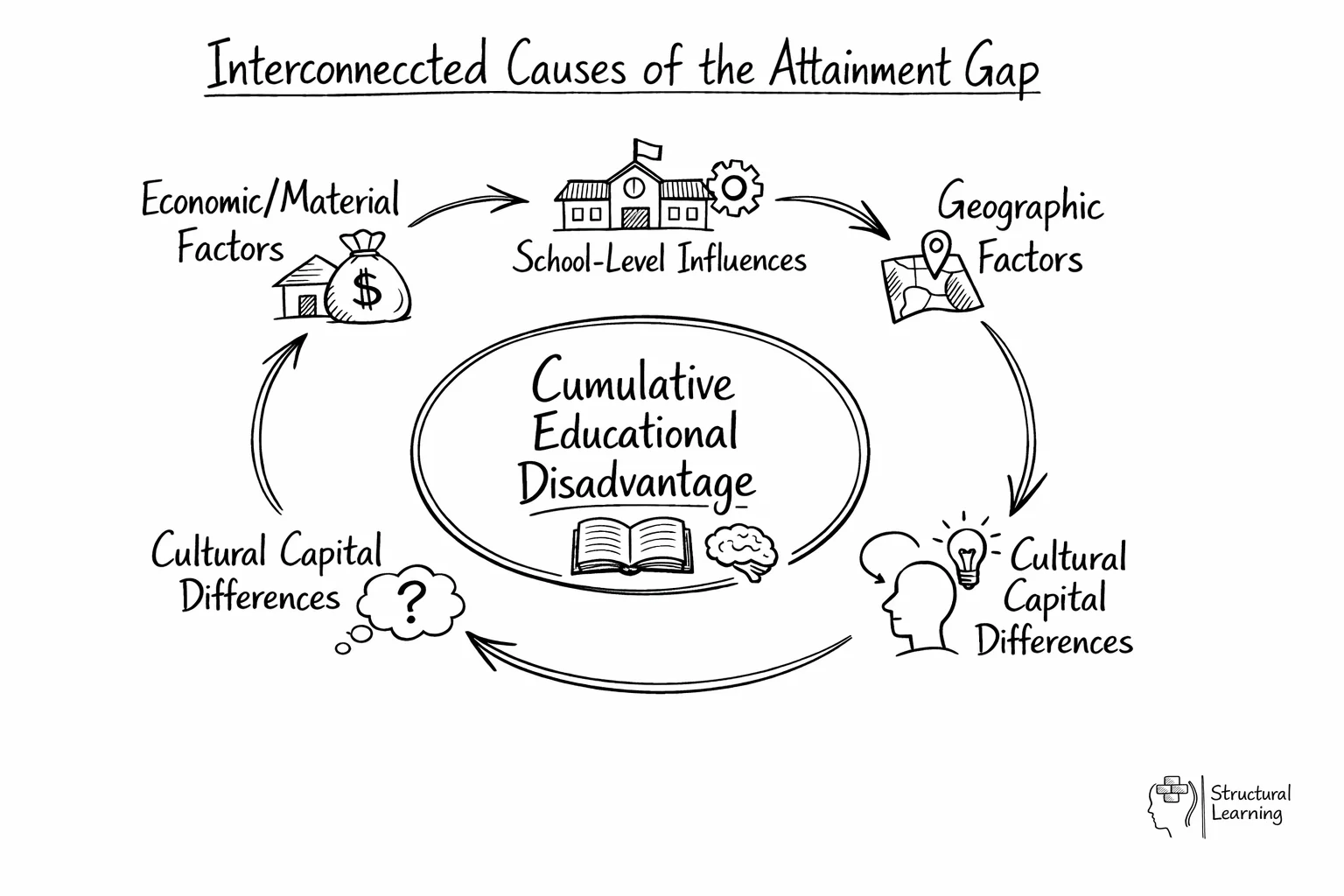

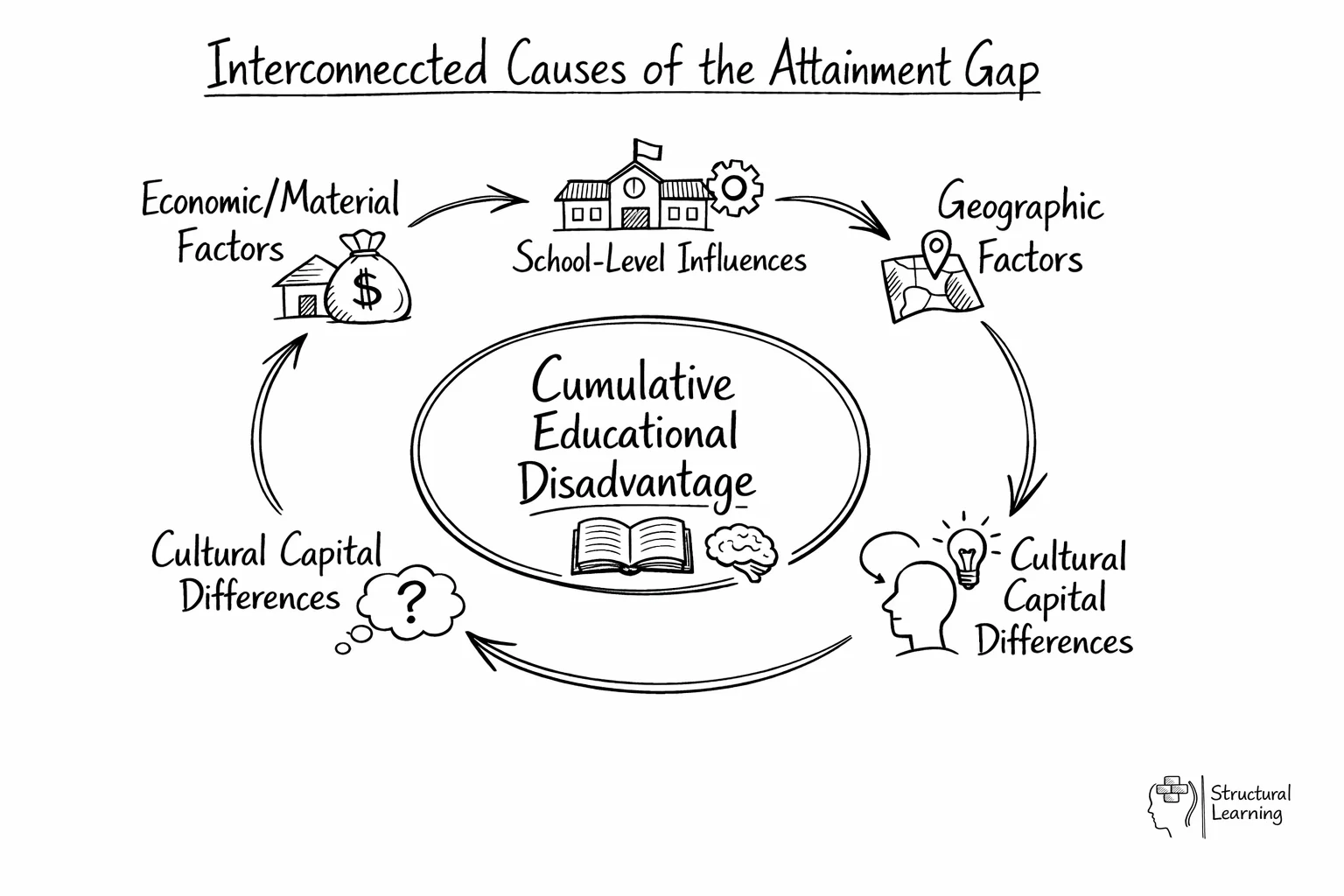

The primary causes include socioeconomic disadvantage (measured by free school meals eligibility), differences in cultural capital between families, and varying levels of parental engagement with education. Additional factors include attention patterns, access to learning resources outside school, and the quality of teaching students receive. Research shows that students from disadvantaged backgrounds often face multiple overlapping barriers that compound educational inequalities.

Multiple interconnected factors, including social learning factors, influence student achievement across different demographic groups.

Basic necessities affect learning capacity. Issues with nutrition, housing, clothing, and transport create immediate barriers to education access. Additional costs for resources, school trips, uniforms, and technology deepen inequalities. Students without reliable internet or devices face compounded disadvantages in today's digital learning environment.

School funding disparities mean students in deprived areas often learn from less experienced teachers with fewer resources. These structural inequalities create cumulative disadvantages that affect long-term outcomes.

Teacher decisions about class leadership, streaming arrangements, and grouping strategies directly impact attainment patterns. Class size affects individual feedback and support available to struggling learners. Even peer composition within classrooms shapes achievement through collaborative learning dynamics and behavioural expectations.

The largest gaps exist between students eligible for free school meals and those with higher socioeconomic status. Free school meals serve as the primary indicator of economic disadvantage in UK education data. Achievement gaps emerge early, becoming measurable bythe end of primary school and widening through secondary education. Schools showing consistent improvements in narrowing these divides prioritise targeted support for disadvantaged pupils.

Parental involvement, support with homework, and access to enrichment activities all boost student success. Differences in cultural capital, such as familiarity with literature, art, and music, also influence academic advantage. Children from more affluent homes often have access to resources, like tutors or educational software, unavailable to disadvantaged peers. These disparities create uneven playing fields that reinforce attainment gaps.

Community-level factors also play a role. Schools in deprived areas may face challenges relating to safety, community engagement, and resources. These combined pressures impact student motivation and achievement.

The attainment gap does not have a single cause, and research makes clear that it operates at multiple levels simultaneously. Basil Bernstein's (1971) work on language codes remains one of the most influential accounts of how social class shapes educational performance. Bernstein argued that middle-class families typically use an 'elaborated code': language that is context-independent, syntactically complex, and oriented towards abstract reasoning. Working-class families more commonly use a 'restricted code': language that is context-dependent, assumes shared understanding, and is more oriented towards concrete, practical meaning. Neither code is linguistically inferior, but the elaborated code is the dominant medium of schooling. Pupils who arrive in Reception using restricted code face an immediate and continuous mismatch between their linguistic resources and the demands of classroom discourse, examination questions, and written tasks.

James Coleman's landmark 1966 report, Equality of Educational Opportunity, used data from 600,000 pupils across 3,000 schools in the United States to reach a conclusion that was politically contentious then and remains contested now: family background was a stronger predictor of attainment than school quality. Coleman found that variation in attainment between schools was substantially smaller than variation within schools, suggesting that what pupils brought to school mattered more than what schools did. His findings were widely cited in debates about whether school improvement could compensate for social inequality. The Coleman Report did not argue that schools were irrelevant; it argued that the effect of school quality was modest relative to the cumulative effects of socioeconomic background on vocabulary, prior knowledge, and motivation.

Eric Hanushek and Ludger Woessmann (2011) subsequently challenged the 'schools don't matter' reading of Coleman by analysing PISA data across 50 countries. They found that the quality of teaching, measured by pupil learning gains rather than input measures such as spending per pupil, had substantial effects on attainment independent of family background. Countries with the highest rates of teacher effectiveness showed significantly smaller socioeconomic gradients in attainment. The implication is not that home factors can be ignored, but that teacher quality is a lever available to policy. A teacher in the top quartile of effectiveness produces, on average, roughly six months more learning per year than a teacher in the bottom quartile, and this effect is largest for pupils from the most disadvantaged backgrounds.

The practical conclusion from this body of research is that home and school factors are both real and both addressable, but they are not equally addressable by schools. Schools cannot directly change a pupil's housing stability, parental employment, or access to books at home. They can, however, influence the quality of instruction, the richness of vocabulary exposure, the consistency of high expectations, and the availability of targeted support. Understanding the multi-level nature of the gap matters because it prevents the misattribution of failure: a school that assumes the gap is entirely caused by home factors will invest less in instruction; a school that assumes the gap is entirely within its control will set unrealistic targets that demoralise staff and pupils alike. The research points towards a third position: school factors are the most tractable lever, and high-quality teaching is where the leverage is greatest.

Addressing the attainment gap requires a multi-faceted approach. Effective strategies include quality-first teaching, targeted interventions, parental engagement initiatives, and culturally responsive practices. Schools must also address systemic inequalities through equitable resource allocation.

Providing additional resources and personalised support to disadvantaged students is essential. This support may include small group tutoring, mentoring programmes, and access to technology. Schools should also work to create inclusive environments that celebrate diversity and promote a sense of belonging for all students.

Implementing evidence-based teaching practices, such as dialogic teaching and formative assessment, helps accelerate learning for all students. Professional development focused o n inclusive pedagogy enables teachers to better meet the needs of diverse learners. Creating a positive classroom climate that creates student engagement and motivation is also key to closing achievement gaps.

Schools should also consider implementing trauma-informed practices to support students who have experienced adversity. These practices create safe, supportive learning environments that promote resilience and academic success.

Building strong relationships with parents and community stakeholders is critical to supporting student success. Schools can offer workshops and resources to help parents support their children's learning at home. Collaborating with community organisations can also provide students with access to additional resources and support services.

Additionally, schools can implement programmes that promote parental involvement in school activities. These programmes may include volunteering opportunities, parent-teacher conferences, and family events. By developing strong partnerships with parents and the community, schools can create a network of support that helps all students thrive.

One mechanism through which the attainment gap widens year on year is summer learning loss: the measurable decline in academic skills that occurs during the long summer holiday. Harris Cooper and colleagues (1996) published a meta-analysis of 39 studies and found that, on average, pupils lost roughly one month of learning during the summer break. The loss was not evenly distributed. In mathematics, disadvantaged pupils lost up to two months of progress while their more affluent peers made small gains. In reading, disadvantaged pupils lost ground while higher-income pupils held steady or improved, often because they had access to books, structured activities, and intellectually stimulating environments during the holiday. When the new school year began, teachers faced a class in which the gap had silently widened over six weeks in which they had no contact with pupils.

Karl Alexander and colleagues (2007) tracked 800 Baltimore pupils from first grade through to young adulthood in their Beginning School Study. Their analysis found that the cumulative effect of unequal summer experiences was the primary driver of the attainment gap by the end of primary school. When they looked at learning rates during the school year, disadvantaged and advantaged pupils learned at broadly similar rates. The gap widened almost exclusively during summers, compounding year after year. By the end of primary school, the cumulative gap in reading and mathematics was almost entirely explained by differential summer learning, not by differences in the rate of school-term progress. This finding has significant implications: it shifts the question from "what are schools doing wrong?" to "what happens when schools are not there?"

Keith Stanovich (1986) described a related mechanism at the individual level: the Matthew Effect in reading, named after the biblical principle that those who have will receive more. Stanovich showed that early reading fluency creates a virtuous cycle. Pupils who read well in Year 1 read more, encounter more vocabulary, build more background knowledge, and develop broader comprehension skills. Pupils who struggle in Year 1 read less, encounter fewer words, and find reading increasingly aversive. The gap between early readers and late readers does not merely persist; it accelerates. By Year 6, the vocabulary and comprehension gap between pupils who had been strong readers at age five and those who had not was far greater than any Year 1 test would have predicted. When summer learning loss compounds the Matthew Effect over seven years of primary school, the attainment gap at age 11 reflects not one summer of lost ground but the cumulative interaction of small advantages and disadvantages repeated across hundreds of school holidays, evenings, and weekends.

For teachers returning in September, this has a concrete implication. Assessment in the first two weeks of term is not merely an administrative exercise; it is the moment at which the summer gap becomes visible and addressable before it becomes embedded in the year's trajectory. Schools that run structured summer programmes, boosted reading access schemes, or September catch-up interventions are working directly against the mechanism Cooper, Alexander, and Stanovich identified. The evidence does not suggest that one summer programme fixes the gap permanently. It suggests that consistent, cumulative effort to maintain learning over summer holidays and across school transitions is one of the few levers that addresses the gap at the point where it is actively growing. Reading comprehension strategies applied consistently from Year 1 onwards are, on this account, one of the highest-leverage investments a school can make.

The attainment gap is typically measured by comparing academic outcomes between disadvantaged pupils and their more advantaged peers across standardised assessments, qualifications, and progression rates. In England, the Department for Education tracks this through the disadvantaged pupils index, which compares pupils eligible for free school meals or in care with the national average. However, effective measurement extends beyond headline statistics to include reading ages, phonics screening results, and subject-specific progress measures that reveal where gaps emerge and widen throughout a child's educational journey.

Schools can implement robust tracking systems by collecting baseline data early and monitoring progress at regular intervals throughout the academic year. Research by John Hattie demonstrates that frequent formative assessment has significant impact on learning outcomes, particularly for disadvantaged groups. Key metrics include termly reading assessments, mathematical reasoning tests, and curriculum-specific checkpoints that allow teachers to identify pupils falling behind before gaps become entrenched. Disaggregated data analysis is essential, examining performance by different characteristics including ethnicity, special educational needs, and English as an additional language status.

Practical measurement strategies include using assessment data to create targeted intervention groups, tracking pupils' confidence and engagement alongside academic progress, and establishing clear success criteria for gap-closing initiatives. Teachers should focus on both summative outcomes and leading indicators such as homework completion rates, attendance patterns, and participation in enrichment activities that correlate with improved attainment.

The attainment gap affects different demographic groups with varying intensity, creating a complex landscape of educational inequality that requires nuanced understanding. Pupils from Black Caribbean and Gypsy, Roma and Traveller backgrounds consistently show the largest gaps compared to their white British peers, whilst students with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) face persistent barriers regardless of ethnicity. However, these categories intersect in crucial ways: a Black Caribbean pupil with SEND experiences compounded disadvantage that cannot be addressed through single-focus interventions.

Gender patterns reveal further complexity, with boys typically underperforming in literacy whilst girls lag behind in mathematics and physics participation. English as an Additional Language (EAL) learners present a particularly interesting case, as recent arrivals often struggle initially but may outperform monolingual peers once language barriers are overcome. Research by Strand and Hessel demonstrates that these intersectional effects mean a white British pupil eligible for free school meals may have different support needs than a Pakistani heritage pupil with similar economic circumstances.

Effective practice recognises these intersectional realities by avoiding blanket approaches. Rather than implementing generic 'disadvantaged pupil' strategies, successful schools analyse their specific cohorts and tailor interventions accordingly. This might involve culturally responsive teaching methods for certain ethnic groups, differentiated language support for EAL learners, or addressing unconscious bias that affects expectations for different demographic combinations.

Finland's remarkable success in reducing educational inequality offers compelling evidence that systemic change can dramatically narrow attainment gaps. The Finnish model prioritises equity over excellence, implementing comprehensive schools that eliminate early streaming and provide extensive support for struggling learners. Research by Pasi Sahlberg demonstrates that Finland's focus on collaborative learning, minimal standardised testing, and highly qualified teachers has created one of the world's most equitable education systems, where socioeconomic background has minimal impact on student outcomes.

Similarly, Canada's provincial approaches, particularly in Ontario, showcase how targeted interventions combined with strong leadership can close gaps effectively. Ontario's literacy and numeracy strategies involved systematic professional development, early identification systems, and sustained funding for disadvantaged schools. These evidence-based approaches resulted in significant improvements for marginalised groups whilst maintaining high overall performance standards.

Classroom practitioners can adapt these international insights by implementing collaborative learning structures, reducing competitive ranking systems, and focusing on formative assessment rather than high-stakes testing. The key lesson from successful international models is that closing attainment gaps requires both individual classroom strategies and whole-school commitment to equity, supported by consistent policy frameworks that prioritise inclusive education over selective practices.

The attainment gap represents a significant challenge for educators. By understanding the underlying causes and implementing evidence-based strategies, schools can work to create more equitable learning environments for all students. Addressing socioeconomic disparities, improving teaching quality, and developing parental engagement are key components of this effort.

Ultimately, closing the attainment gap requires a commitment from all stakeholders including educators, policymakers, and communities. By working together, we can ensure that all students have the opportunity to reach their full potential, regardless of their background or circumstances. This commitment will not only benefit individual students but will also contribute to a more just and equitable society.

Going forward, schools must prioritise evidence-based approaches that have demonstrated measurable impact on disadvantaged pupils. This includes implementing high-quality tutoring programmes, enhancing early literacy and numeracy interventions, and ensuring teaching assistants are deployed effectively to support learning rather than simply providing care. School leaders should establish robust systems for tracking the progress of disadvantaged pupils, using this data to identify gaps early and adjust interventions accordingly. Professional development must equip teachers with the skills to adapt their practice for pupils facing additional barriers to learning.

The path to closing the attainment gap requires sustained commitment and realistic expectations about timescales. Schools that succeed in narrowing gaps typically maintain focus on this agenda for several years, embedding equity considerations into all aspects of school planning and resource allocation. Collaboration between schools, sharing effective practices and learning from challenges, can accelerate progress across entire communities. While individual educators may feel the scale of educational inequality is overwhelming, collective action and evidence-informed practice can create meaningful change that transforms pupils' educational trajectories and life outcomes.

The attainment gap refers to the measurable difference in academic performance between specific groups of students. It is most often used to describe the disparity between pupils from low income families and their more affluent peers. These gaps can be identified through test scores, literacy levels, and overall progress throughout school.

Teachers can narrow the gap by focusing on high quality classroom instruction and inclusive pedagogical methods. Using scaffolding and providing clear feedback helps students who might lack academic support at home. Regularly checking for understanding ensures that all learners can access the curriculum regardless of their starting point.

Evidence from organisations like the Education Endowment Foundation suggests that metacognition and self regulation strategies have a high impact on progress. Research indicates that targeted small group tuition and oral language interventions are particularly effective for younger children. Successful schools combine these approaches with a consistent focus on attendance and wellbeing.

Many children from disadvantaged backgrounds are already behind their peers before they enter primary school. If these initial differences are not addressed quickly, they tend to increase as the curriculum becomes more complex. Early support helps to stop these disparities from becoming permanent obstacles to success at GCSE and beyond.

A frequent mistake is assuming that every student eligible for free school meals faces the same challenges. Some schools rely too heavily on one to one support from staff who are not fully qualified teachers. It is also a mistake to focus only on academic data while ignoring the material barriers that affect a child ability to learn.

This funding provides schools with additional resources to improve the outcomes of students who face economic disadvantage. It can be used to pay for professional development, school trips, or specific technology that helps children learn more effectively. When used for evidence based strategies, this money helps to provide more equal opportunities for every pupil.

Specify your gap type, key stage, and subject to receive ranked strategies with expected impact and implementation guidance.

Enter your budget, select strategies, and instantly see which approaches deliver the most progress per pound spent.

Enter your PP budget, select evidence-ranked strategies across three tiers, and generate a complete strategy plan with ROI analysis.

The attainment gap represents one of education's most persistent challenges. Understanding its causes and implementing evidence-based strategies can help schools support all learners effectively.

| Examples (This IS the Attainment Gap) | Non-Examples (This is NOT the Attainment Gap) |

|---|---|

| Students on free school meals achieving significantly lower GCSE grades than their peers, a measurable difference between demographic groups | Individual students performing differently due to personal effort or interest, not systematic group differences |

| Children from low-income areas reading at significantly lower levels than peers from affluent areas, showing systematic educational disparities | A single school having varying test scores across different subjects, this is curriculum variation, not demographic disparity |

| SEND students consistently scoring substantially below school averages across multiple schools, pattern-based inequality | One student struggling with math while excelling in English, individual learning differences, not group-based gaps |

| Schools in deprived areas having substantially fewer students achieving university entry requirements compared to affluent areas, systemic achievement differences | Teachers having different teaching styles that students respond to differently, pedagogical preferences, not educational inequality |

The attainment gap describes the difference in educational achievement between subgroups of students. These disparities typically emerge along lines of socioeconomic status, ethnicity, gender, and special educational needs. For UK state schools, this metric has become central to accountability frameworks.

Schools receiving funding must demonstrate how specific activities help disadvantaged pupil progress. Education providers need clear evidence showing how they advance opportunities for society's most vulnerable learners. The Education Endowment Foundation provides schools with research-backed approaches, including active learning approaches, that can significantly impact children's educational trajectories.

The pandemic amplified existing inequalities. Learning loss during school closures hit children from disadvantaged backgrounds hardest, revealing schools' transformative potential. Academic activities coordinated in school settings, supported by effective curriculum design, help students overcome barriers they would otherwise face without targeted support. Differences in cultural capital between families also contribute to these educational disparities.

The attainment gap manifests differently across educational stages and subjects. In primary schools, gaps often emerge early in literacy and numeracy, with some children entering Year 1 already 19 months behind their peers in language development. These early disparities tend to compound over time, creating what researchers call the 'Matthew effect' - where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer academically.

At secondary level, the gap becomes particularly pronounced in GCSE outcomes. For instance, pupils eligible for free school meals achieve grade 4 or above in English and maths at rates consistently 20-30 percentage points lower than their more advantaged peers. The gap extends beyond academic subjects, affecting participation in enrichment activities, university applications, and career aspirations. Understanding these nuances helps educators recognise that closing the attainment gap requires sustained, targeted intervention throughout a child's educational journey.

Recognising the attainment gap in practice requires looking beyond headline data to examine patterns within your own setting. Teachers might notice that disadvantaged pupils are more likely to arrive at school without breakfast, have fewer opportunities for homework support at home, or show reluctance to participate in class discussions. School leaders often observe these pupils are underrepresented in higher sets, extracurricular activities, or leadership roles. By identifying these everyday manifestations of educational inequality, educators can implement evidence-based approaches such as quality-first teaching, strategic use of pupil premium funding, and partnerships with families to create meaningful change.

The Department for Education defines the attainment gap as the persistent difference in educational outcomes between pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds and their peers. In practice, 'disadvantaged' is most commonly operationalised through eligibility for free school meals (FSM): a proxy measure that captures household income below a threshold tied to benefits entitlement. The FSM proxy is administratively convenient and widely used, but it has known limitations. It captures a snapshot of current poverty rather than a history of deprivation, and it excludes many pupils who are in low-income households but do not qualify. Researchers routinely note that the gap between FSM and non-FSM pupils represents the lower bound of the true disadvantage gap.

The Education Policy Institute tracks attainment differences across key stages using the Disadvantage Gap Index (DGI), a composite measure that combines attainment data from Early Years through to the end of secondary school. Hutchinson et al. (2019) published a landmark EPI analysis showing that, at age 16, disadvantaged pupils in England were on average 18.1 months of learning behind their peers. The gap was not uniform: it was widest in coastal towns and post-industrial areas of the North and Midlands, and narrowest in Inner London, where decades of sustained investment and a high density of high-performing schools had made measurable inroads. At Key Stage 2, the gap was smaller but still substantial, with disadvantaged pupils around nine months behind by the end of primary school.

Regional variation matters because it complicates any single national policy response. A school in a deprived coastal community faces a different combination of challenges from a school in an urban area with high immigration and strong community networks. The EPI analysis also tracks the gap over time. Progress was made between 2007 and 2017, with the gap at age 16 narrowing by roughly five months over a decade. That progress stalled after 2017, and the disruption caused by school closures during 2020 and 2021 reversed gains made at every key stage. By 2022, the gap at age 16 had widened to levels not seen since 2012.

For teachers, the measurement debate has a practical implication. When schools use FSM as their sole identifier of disadvantage, they risk missing a substantial group of pupils who are quietly falling behind. The Pupil Premium funding mechanism is tied to FSM eligibility and looked-after children status, but good practice goes further. Schools that track attainment by postcode, family mobility, and prior attainment history tend to identify a wider range of pupils who would benefit from targeted support. The DGI is useful for benchmarking; the harder work is building the classroom-level picture that the national index cannot provide.

The primary causes include socioeconomic disadvantage (measured by free school meals eligibility), differences in cultural capital between families, and varying levels of parental engagement with education. Additional factors include attention patterns, access to learning resources outside school, and the quality of teaching students receive. Research shows that students from disadvantaged backgrounds often face multiple overlapping barriers that compound educational inequalities.

Multiple interconnected factors, including social learning factors, influence student achievement across different demographic groups.

Basic necessities affect learning capacity. Issues with nutrition, housing, clothing, and transport create immediate barriers to education access. Additional costs for resources, school trips, uniforms, and technology deepen inequalities. Students without reliable internet or devices face compounded disadvantages in today's digital learning environment.

School funding disparities mean students in deprived areas often learn from less experienced teachers with fewer resources. These structural inequalities create cumulative disadvantages that affect long-term outcomes.

Teacher decisions about class leadership, streaming arrangements, and grouping strategies directly impact attainment patterns. Class size affects individual feedback and support available to struggling learners. Even peer composition within classrooms shapes achievement through collaborative learning dynamics and behavioural expectations.

The largest gaps exist between students eligible for free school meals and those with higher socioeconomic status. Free school meals serve as the primary indicator of economic disadvantage in UK education data. Achievement gaps emerge early, becoming measurable bythe end of primary school and widening through secondary education. Schools showing consistent improvements in narrowing these divides prioritise targeted support for disadvantaged pupils.

Parental involvement, support with homework, and access to enrichment activities all boost student success. Differences in cultural capital, such as familiarity with literature, art, and music, also influence academic advantage. Children from more affluent homes often have access to resources, like tutors or educational software, unavailable to disadvantaged peers. These disparities create uneven playing fields that reinforce attainment gaps.

Community-level factors also play a role. Schools in deprived areas may face challenges relating to safety, community engagement, and resources. These combined pressures impact student motivation and achievement.

The attainment gap does not have a single cause, and research makes clear that it operates at multiple levels simultaneously. Basil Bernstein's (1971) work on language codes remains one of the most influential accounts of how social class shapes educational performance. Bernstein argued that middle-class families typically use an 'elaborated code': language that is context-independent, syntactically complex, and oriented towards abstract reasoning. Working-class families more commonly use a 'restricted code': language that is context-dependent, assumes shared understanding, and is more oriented towards concrete, practical meaning. Neither code is linguistically inferior, but the elaborated code is the dominant medium of schooling. Pupils who arrive in Reception using restricted code face an immediate and continuous mismatch between their linguistic resources and the demands of classroom discourse, examination questions, and written tasks.

James Coleman's landmark 1966 report, Equality of Educational Opportunity, used data from 600,000 pupils across 3,000 schools in the United States to reach a conclusion that was politically contentious then and remains contested now: family background was a stronger predictor of attainment than school quality. Coleman found that variation in attainment between schools was substantially smaller than variation within schools, suggesting that what pupils brought to school mattered more than what schools did. His findings were widely cited in debates about whether school improvement could compensate for social inequality. The Coleman Report did not argue that schools were irrelevant; it argued that the effect of school quality was modest relative to the cumulative effects of socioeconomic background on vocabulary, prior knowledge, and motivation.

Eric Hanushek and Ludger Woessmann (2011) subsequently challenged the 'schools don't matter' reading of Coleman by analysing PISA data across 50 countries. They found that the quality of teaching, measured by pupil learning gains rather than input measures such as spending per pupil, had substantial effects on attainment independent of family background. Countries with the highest rates of teacher effectiveness showed significantly smaller socioeconomic gradients in attainment. The implication is not that home factors can be ignored, but that teacher quality is a lever available to policy. A teacher in the top quartile of effectiveness produces, on average, roughly six months more learning per year than a teacher in the bottom quartile, and this effect is largest for pupils from the most disadvantaged backgrounds.

The practical conclusion from this body of research is that home and school factors are both real and both addressable, but they are not equally addressable by schools. Schools cannot directly change a pupil's housing stability, parental employment, or access to books at home. They can, however, influence the quality of instruction, the richness of vocabulary exposure, the consistency of high expectations, and the availability of targeted support. Understanding the multi-level nature of the gap matters because it prevents the misattribution of failure: a school that assumes the gap is entirely caused by home factors will invest less in instruction; a school that assumes the gap is entirely within its control will set unrealistic targets that demoralise staff and pupils alike. The research points towards a third position: school factors are the most tractable lever, and high-quality teaching is where the leverage is greatest.

Addressing the attainment gap requires a multi-faceted approach. Effective strategies include quality-first teaching, targeted interventions, parental engagement initiatives, and culturally responsive practices. Schools must also address systemic inequalities through equitable resource allocation.

Providing additional resources and personalised support to disadvantaged students is essential. This support may include small group tutoring, mentoring programmes, and access to technology. Schools should also work to create inclusive environments that celebrate diversity and promote a sense of belonging for all students.

Implementing evidence-based teaching practices, such as dialogic teaching and formative assessment, helps accelerate learning for all students. Professional development focused o n inclusive pedagogy enables teachers to better meet the needs of diverse learners. Creating a positive classroom climate that creates student engagement and motivation is also key to closing achievement gaps.

Schools should also consider implementing trauma-informed practices to support students who have experienced adversity. These practices create safe, supportive learning environments that promote resilience and academic success.

Building strong relationships with parents and community stakeholders is critical to supporting student success. Schools can offer workshops and resources to help parents support their children's learning at home. Collaborating with community organisations can also provide students with access to additional resources and support services.

Additionally, schools can implement programmes that promote parental involvement in school activities. These programmes may include volunteering opportunities, parent-teacher conferences, and family events. By developing strong partnerships with parents and the community, schools can create a network of support that helps all students thrive.

One mechanism through which the attainment gap widens year on year is summer learning loss: the measurable decline in academic skills that occurs during the long summer holiday. Harris Cooper and colleagues (1996) published a meta-analysis of 39 studies and found that, on average, pupils lost roughly one month of learning during the summer break. The loss was not evenly distributed. In mathematics, disadvantaged pupils lost up to two months of progress while their more affluent peers made small gains. In reading, disadvantaged pupils lost ground while higher-income pupils held steady or improved, often because they had access to books, structured activities, and intellectually stimulating environments during the holiday. When the new school year began, teachers faced a class in which the gap had silently widened over six weeks in which they had no contact with pupils.

Karl Alexander and colleagues (2007) tracked 800 Baltimore pupils from first grade through to young adulthood in their Beginning School Study. Their analysis found that the cumulative effect of unequal summer experiences was the primary driver of the attainment gap by the end of primary school. When they looked at learning rates during the school year, disadvantaged and advantaged pupils learned at broadly similar rates. The gap widened almost exclusively during summers, compounding year after year. By the end of primary school, the cumulative gap in reading and mathematics was almost entirely explained by differential summer learning, not by differences in the rate of school-term progress. This finding has significant implications: it shifts the question from "what are schools doing wrong?" to "what happens when schools are not there?"

Keith Stanovich (1986) described a related mechanism at the individual level: the Matthew Effect in reading, named after the biblical principle that those who have will receive more. Stanovich showed that early reading fluency creates a virtuous cycle. Pupils who read well in Year 1 read more, encounter more vocabulary, build more background knowledge, and develop broader comprehension skills. Pupils who struggle in Year 1 read less, encounter fewer words, and find reading increasingly aversive. The gap between early readers and late readers does not merely persist; it accelerates. By Year 6, the vocabulary and comprehension gap between pupils who had been strong readers at age five and those who had not was far greater than any Year 1 test would have predicted. When summer learning loss compounds the Matthew Effect over seven years of primary school, the attainment gap at age 11 reflects not one summer of lost ground but the cumulative interaction of small advantages and disadvantages repeated across hundreds of school holidays, evenings, and weekends.

For teachers returning in September, this has a concrete implication. Assessment in the first two weeks of term is not merely an administrative exercise; it is the moment at which the summer gap becomes visible and addressable before it becomes embedded in the year's trajectory. Schools that run structured summer programmes, boosted reading access schemes, or September catch-up interventions are working directly against the mechanism Cooper, Alexander, and Stanovich identified. The evidence does not suggest that one summer programme fixes the gap permanently. It suggests that consistent, cumulative effort to maintain learning over summer holidays and across school transitions is one of the few levers that addresses the gap at the point where it is actively growing. Reading comprehension strategies applied consistently from Year 1 onwards are, on this account, one of the highest-leverage investments a school can make.

The attainment gap is typically measured by comparing academic outcomes between disadvantaged pupils and their more advantaged peers across standardised assessments, qualifications, and progression rates. In England, the Department for Education tracks this through the disadvantaged pupils index, which compares pupils eligible for free school meals or in care with the national average. However, effective measurement extends beyond headline statistics to include reading ages, phonics screening results, and subject-specific progress measures that reveal where gaps emerge and widen throughout a child's educational journey.

Schools can implement robust tracking systems by collecting baseline data early and monitoring progress at regular intervals throughout the academic year. Research by John Hattie demonstrates that frequent formative assessment has significant impact on learning outcomes, particularly for disadvantaged groups. Key metrics include termly reading assessments, mathematical reasoning tests, and curriculum-specific checkpoints that allow teachers to identify pupils falling behind before gaps become entrenched. Disaggregated data analysis is essential, examining performance by different characteristics including ethnicity, special educational needs, and English as an additional language status.

Practical measurement strategies include using assessment data to create targeted intervention groups, tracking pupils' confidence and engagement alongside academic progress, and establishing clear success criteria for gap-closing initiatives. Teachers should focus on both summative outcomes and leading indicators such as homework completion rates, attendance patterns, and participation in enrichment activities that correlate with improved attainment.

The attainment gap affects different demographic groups with varying intensity, creating a complex landscape of educational inequality that requires nuanced understanding. Pupils from Black Caribbean and Gypsy, Roma and Traveller backgrounds consistently show the largest gaps compared to their white British peers, whilst students with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) face persistent barriers regardless of ethnicity. However, these categories intersect in crucial ways: a Black Caribbean pupil with SEND experiences compounded disadvantage that cannot be addressed through single-focus interventions.

Gender patterns reveal further complexity, with boys typically underperforming in literacy whilst girls lag behind in mathematics and physics participation. English as an Additional Language (EAL) learners present a particularly interesting case, as recent arrivals often struggle initially but may outperform monolingual peers once language barriers are overcome. Research by Strand and Hessel demonstrates that these intersectional effects mean a white British pupil eligible for free school meals may have different support needs than a Pakistani heritage pupil with similar economic circumstances.

Effective practice recognises these intersectional realities by avoiding blanket approaches. Rather than implementing generic 'disadvantaged pupil' strategies, successful schools analyse their specific cohorts and tailor interventions accordingly. This might involve culturally responsive teaching methods for certain ethnic groups, differentiated language support for EAL learners, or addressing unconscious bias that affects expectations for different demographic combinations.

Finland's remarkable success in reducing educational inequality offers compelling evidence that systemic change can dramatically narrow attainment gaps. The Finnish model prioritises equity over excellence, implementing comprehensive schools that eliminate early streaming and provide extensive support for struggling learners. Research by Pasi Sahlberg demonstrates that Finland's focus on collaborative learning, minimal standardised testing, and highly qualified teachers has created one of the world's most equitable education systems, where socioeconomic background has minimal impact on student outcomes.

Similarly, Canada's provincial approaches, particularly in Ontario, showcase how targeted interventions combined with strong leadership can close gaps effectively. Ontario's literacy and numeracy strategies involved systematic professional development, early identification systems, and sustained funding for disadvantaged schools. These evidence-based approaches resulted in significant improvements for marginalised groups whilst maintaining high overall performance standards.

Classroom practitioners can adapt these international insights by implementing collaborative learning structures, reducing competitive ranking systems, and focusing on formative assessment rather than high-stakes testing. The key lesson from successful international models is that closing attainment gaps requires both individual classroom strategies and whole-school commitment to equity, supported by consistent policy frameworks that prioritise inclusive education over selective practices.

The attainment gap represents a significant challenge for educators. By understanding the underlying causes and implementing evidence-based strategies, schools can work to create more equitable learning environments for all students. Addressing socioeconomic disparities, improving teaching quality, and developing parental engagement are key components of this effort.

Ultimately, closing the attainment gap requires a commitment from all stakeholders including educators, policymakers, and communities. By working together, we can ensure that all students have the opportunity to reach their full potential, regardless of their background or circumstances. This commitment will not only benefit individual students but will also contribute to a more just and equitable society.

Going forward, schools must prioritise evidence-based approaches that have demonstrated measurable impact on disadvantaged pupils. This includes implementing high-quality tutoring programmes, enhancing early literacy and numeracy interventions, and ensuring teaching assistants are deployed effectively to support learning rather than simply providing care. School leaders should establish robust systems for tracking the progress of disadvantaged pupils, using this data to identify gaps early and adjust interventions accordingly. Professional development must equip teachers with the skills to adapt their practice for pupils facing additional barriers to learning.

The path to closing the attainment gap requires sustained commitment and realistic expectations about timescales. Schools that succeed in narrowing gaps typically maintain focus on this agenda for several years, embedding equity considerations into all aspects of school planning and resource allocation. Collaboration between schools, sharing effective practices and learning from challenges, can accelerate progress across entire communities. While individual educators may feel the scale of educational inequality is overwhelming, collective action and evidence-informed practice can create meaningful change that transforms pupils' educational trajectories and life outcomes.

The attainment gap refers to the measurable difference in academic performance between specific groups of students. It is most often used to describe the disparity between pupils from low income families and their more affluent peers. These gaps can be identified through test scores, literacy levels, and overall progress throughout school.

Teachers can narrow the gap by focusing on high quality classroom instruction and inclusive pedagogical methods. Using scaffolding and providing clear feedback helps students who might lack academic support at home. Regularly checking for understanding ensures that all learners can access the curriculum regardless of their starting point.

Evidence from organisations like the Education Endowment Foundation suggests that metacognition and self regulation strategies have a high impact on progress. Research indicates that targeted small group tuition and oral language interventions are particularly effective for younger children. Successful schools combine these approaches with a consistent focus on attendance and wellbeing.

Many children from disadvantaged backgrounds are already behind their peers before they enter primary school. If these initial differences are not addressed quickly, they tend to increase as the curriculum becomes more complex. Early support helps to stop these disparities from becoming permanent obstacles to success at GCSE and beyond.

A frequent mistake is assuming that every student eligible for free school meals faces the same challenges. Some schools rely too heavily on one to one support from staff who are not fully qualified teachers. It is also a mistake to focus only on academic data while ignoring the material barriers that affect a child ability to learn.

This funding provides schools with additional resources to improve the outcomes of students who face economic disadvantage. It can be used to pay for professional development, school trips, or specific technology that helps children learn more effectively. When used for evidence based strategies, this money helps to provide more equal opportunities for every pupil.

Specify your gap type, key stage, and subject to receive ranked strategies with expected impact and implementation guidance.

Enter your budget, select strategies, and instantly see which approaches deliver the most progress per pound spent.

Enter your PP budget, select evidence-ranked strategies across three tiers, and generate a complete strategy plan with ROI analysis.

<script type="application/ld+json">{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/attainment-gap-a-teachers-guide#article","headline":"The Attainment Gap: Understanding and Closing","description":"Examine the factors contributing to the attainment gap and implement evidence-based strategies to enhance educational equity for all students.","datePublished":"2022-03-13T19:29:41.127Z","dateModified":"2026-03-02T11:01:26.200Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/attainment-gap-a-teachers-guide"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6973351be04d553853f36209_6973351526231c6a047666b9_attainment-gap-a-teachers-guide-illustration.webp","wordCount":2296},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/attainment-gap-a-teachers-guide#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"The Attainment Gap: Understanding and Closing","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/attainment-gap-a-teachers-guide"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is the attainment gap in UK schools?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The attainment gap refers to the measurable difference in academic performance between specific groups of students. It is most often used to describe the disparity between pupils from low income families and their more affluent peers. These gaps can be identified through test scores, literacy levels, and overall progress throughout school."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers reduce the attainment gap in the classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can narrow the gap by focusing on high quality classroom instruction and inclusive pedagogical methods. Using scaffolding and providing clear feedback helps students who might lack academic support at home. Regularly checking for understanding ensures that all learners can access the curriculum regardless of their starting point."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What does the research say about closing the attainment gap?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Evidence from organisations like the Education Endowment Foundation suggests that metacognition and self regulation strategies have a high impact on progress. Research indicates that targeted small group tuition and oral language interventions are particularly effective for younger children. Successful schools combine these approaches with a consistent focus on attendance and wellbeing."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why is it important to address the attainment gap early?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Many children from disadvantaged backgrounds are already behind their peers before they enter primary school. If these initial differences are not addressed quickly, they tend to increase as the curriculum becomes more complex. Early support helps to stop these disparities from becoming permanent obstacles to success at GCSE and beyond."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are common mistakes when trying to close the attainment gap?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"A frequent mistake is assuming that every student eligible for free school meals faces the same challenges. Some schools rely too heavily on one to one support from staff who are not fully qualified teachers. It is also a mistake to focus only on academic data while ignoring the material barriers that affect a child ability to learn."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How does pupil premium funding support disadvantaged learners?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"This funding provides schools with additional resources to improve the outcomes of students who face economic disadvantage. It can be used to pay for professional development, school trips, or specific technology that helps children learn more effectively. When used for evidence based strategies, this money helps to provide more equal opportunities for every pupil."}}]}]}</script>