The Zone of Proximal Development: A teacher's guide

Discover how to use the Zone of Proximal Development to transform struggling pupils into confident learners through strategic scaffolding and peer learning.

Every day in your classroom, you witness the perfect teaching moment: a student struggles with a concept independently but grasps it immediately with just the right hint or guidance. This is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) in action, and learning to recognise and harness these moments can transform your teaching effectiveness. Rather than guessing when to step in or step back, you can use specific strategies to identify each student's ZPD and create targeted learning experiences that challenge without overwhelming. The key lies in knowing exactly what to look for and how to respond.

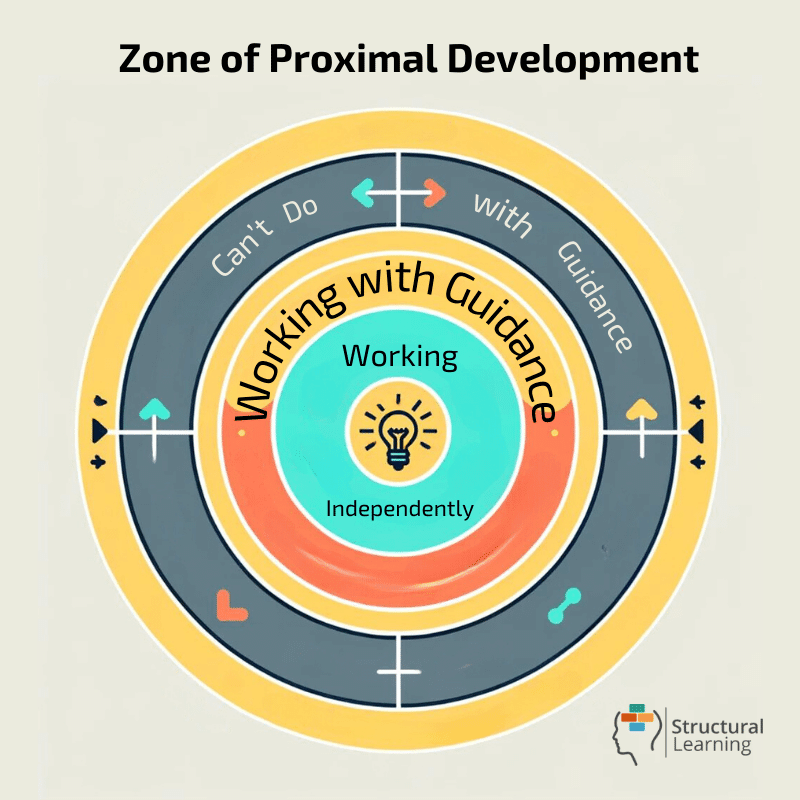

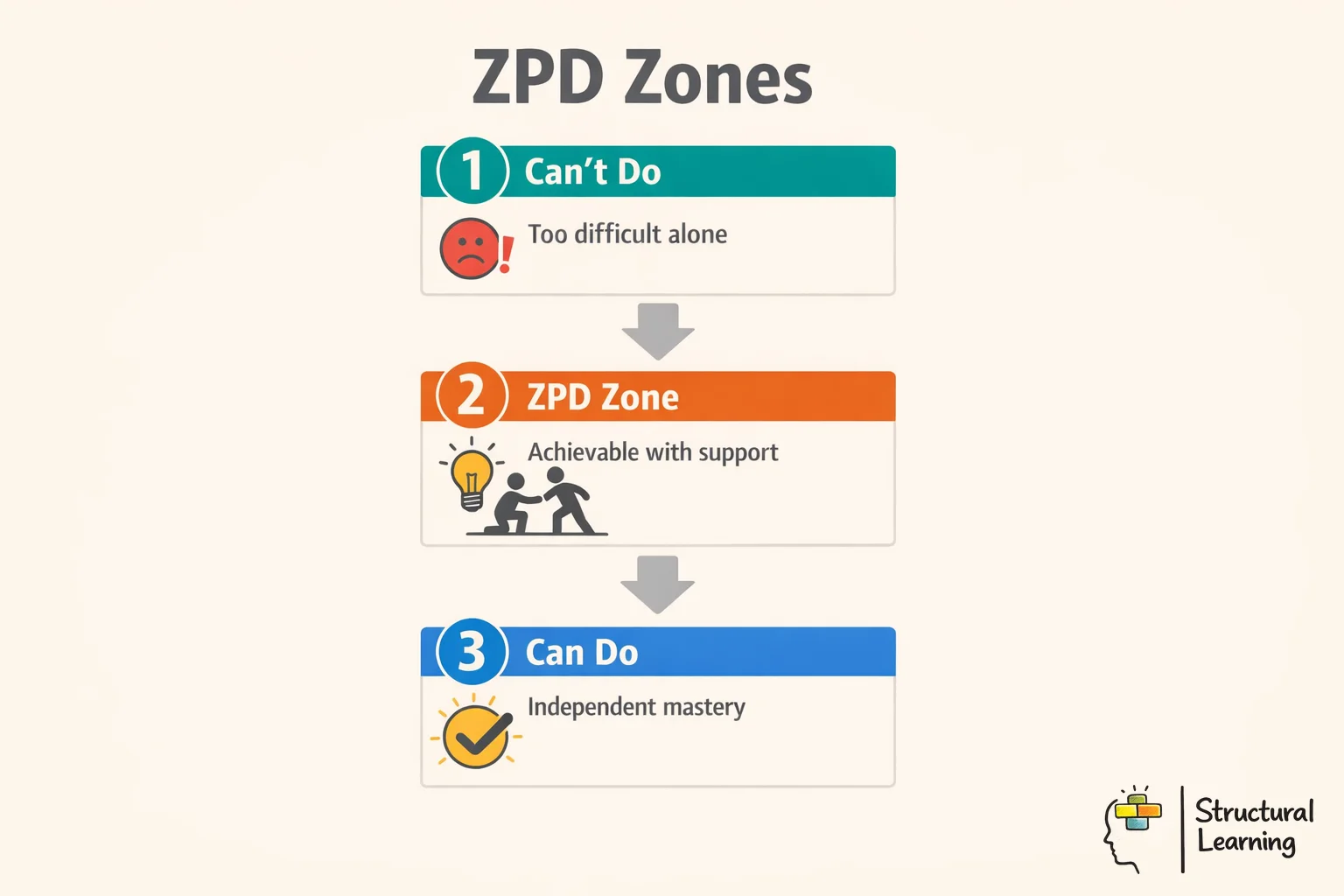

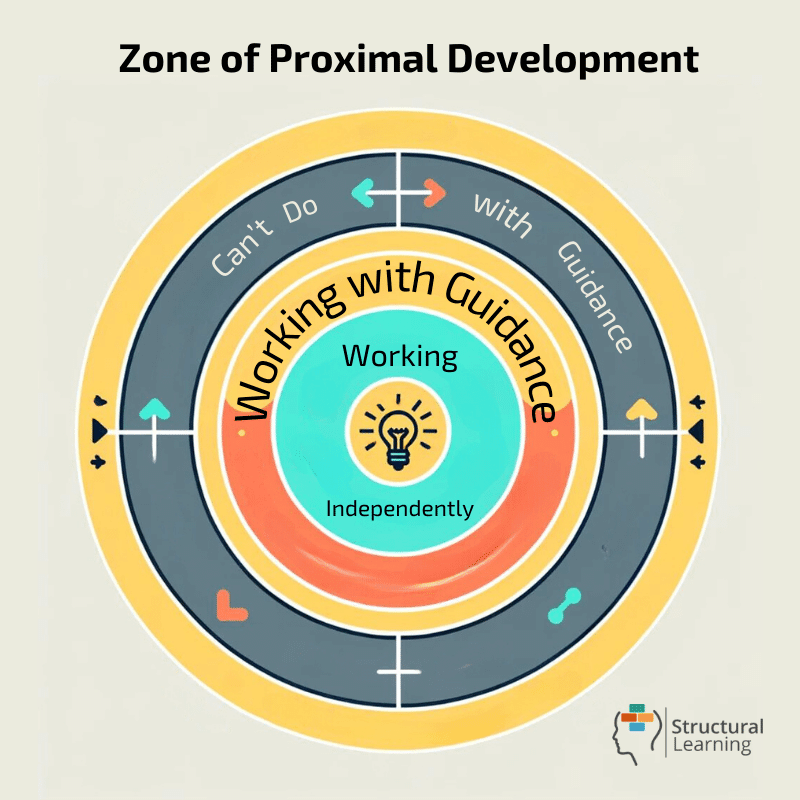

At its core, the ZPD represents the difference between what learners can do independently, which is their level of development, and what they can achieve with guidance, their potential level. This concept is essential in designing supportive activities that stretch a student's capabilities just beyond their current capacity, building on supportive relationshipsto promote cognitive growth.

Within the ZPD, learning is neither too easy nor too challenging; it's in this 'zone' that the most effective learning takes place. It acknowledges the dynamic nature of learning, advocating for tailored support that considers cultural contexts and individual learner differences. By providing optimal challenges and scaffolding, educators can help students build upon their existing knowledge and skills.

As we examine deeper into this article, we will explore how educators can identify a student's ZPD and use it to facilitate learning that is both engaging and transformative. We will also consider how the application of the ZPD can be adapted to various cultural contexts, ensuring that the potential level of cognitive development can be reached through culturally responsive teachingmethods.

The zone of proximal development indicates the difference between what a student can do without guidance and what he can achieve with the encouragement and guidance of a skilled partner. Therefore, the term “proximal” relates to those skills that the student is “close” to mastering. This theory of learning can be useful for teachers.

Reflective Questions

1. How does ZPD relate to other concepts such as scaffolding or peer tutoring?

2. Why are some students better at using this approach than others?

3. Can you think of any situations where it would be useful for teachers to use this strategy?

4. Is there anything else we should know about ZPD?

5. Do you have any ideas on how to implement this strategy into your own teaching practise?

The Zone of Proximal Development was developed by Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky in the 1930s as part of his sociocultural theory of cognitive development. Vygotsky introduced the concept to explain how children learn best through social interaction with more knowledgeable others, contrasting with Piaget's view that development precedes learning. The theory gained widespread recognition in Western education during the 1970s and 1980s.

The historical development of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is anchored in the work of Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky, whose ideas transformed educational theory and child psychology. Vygotsky, in the early 20th century, proposed the ZPD against the backdrop of a burgeoning interest in the analysis of learning and cognitive ability.

His theory suggested that children's development is profoundly influenced by their cultural context and the skilled partners in their learning environment.

Vygotsky's pioneering work was largely conducted at the Institute of Psychology in Moscow, where he posited that learning precedes development, a concept that stood in contrast to the prevailing views of the time.

This perspective underscored the importance of social interaction in the development of cognition. Vygotsky observed that through collaborative dialogue and problem-solving with more knowledgeable others, whether teachers, peers, or parents, children could achieve a higher level of understanding and skill than they could independently.

The legacy of Vygotsky's work, particularly the ZPD, has been widely disseminated through a range of universities worldwide. Scholars have expanded on his concepts, exploring the intricacies of how social factors contribute to cognitive development in children.

Western universities have often been the site of rich academic discourse on the subject, with researchers in the United States and Europe analysing and applying Vygotsky's theories within diverse educational settings.

As part of the broad spectrum of child development theories, the ZPD remains a cornerstone of contemporary educational psychology. It has inspired a wide range of instructional strategies that aim to improve learning by matching challenges to a child's current capabilities while also stretching them into the field of potential development.

The historical and ongoing research into the ZPD underscores its significance as a tool for understanding how to effectively support the cognitive and academic growth of children across various cultural and educational landscapes.

How Does It Work?

When a learner needs assistance, they ask their peers or instructors for advice. The instructor provides feedback based on the learner's performance. This helps them learn new strategies and techniques. As the learner masters these new skills, the instructor gradually reduces her involvement until she no longer offers direct instruction. At this point, the learner is capable of performing the activity independently.

Teachers use ZPD by first assessing what students can do independently, then designing activities slightly beyond their current ability level that require guidance. They provide support through modelling, questioning, and collaborative work, gradually reducing assistance as students become more capable. This approach ensures students are challenged but not overwhelmed, maximising learning potential.

To help a student to move through the zone of proximal development, teachers must focus on three essential components that facilitate the learning process:

The zone of proximal development (ZPD), is an educational notion constantly restated by the professors in the lecture halls. However, why is it so crucial in a classroom setting for a childs mental development? The crux of the zone of proximal development is that a child with more skills and mastery (the skilled partner), can be used to enhance the potential level of knowledge and another individual.

These type of social interactions can be used to enhance educational outcomes in problem-based learning activities. The level of challenge can be incrementally increased with appropriate levels of scaffolding in a way that neither individual feels overwhelmed by the complexity of the task.

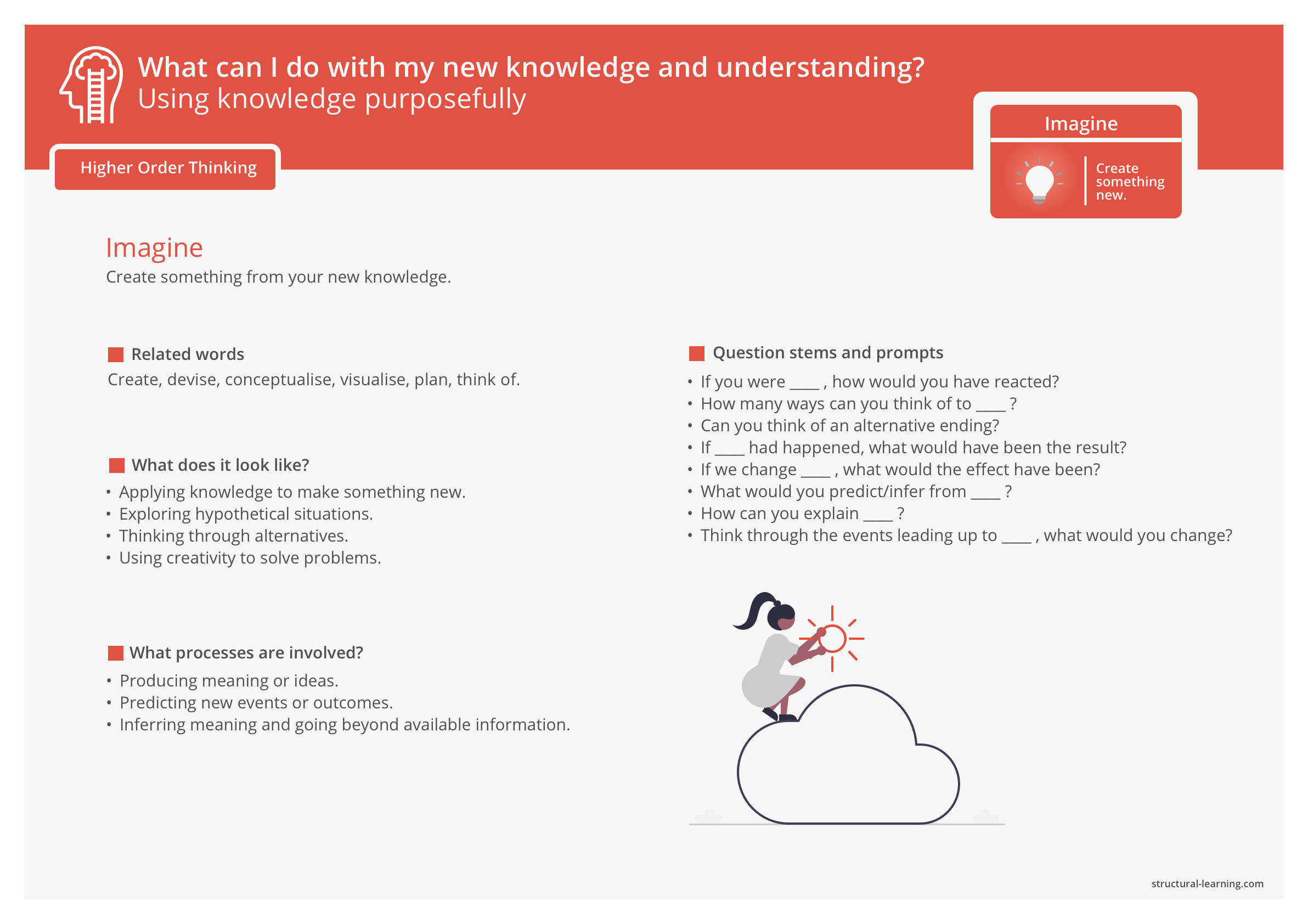

This type of social interaction can be used as a catalyst for critical thinking. The interaction with peers enables children to engage cognitively at much higher levels.

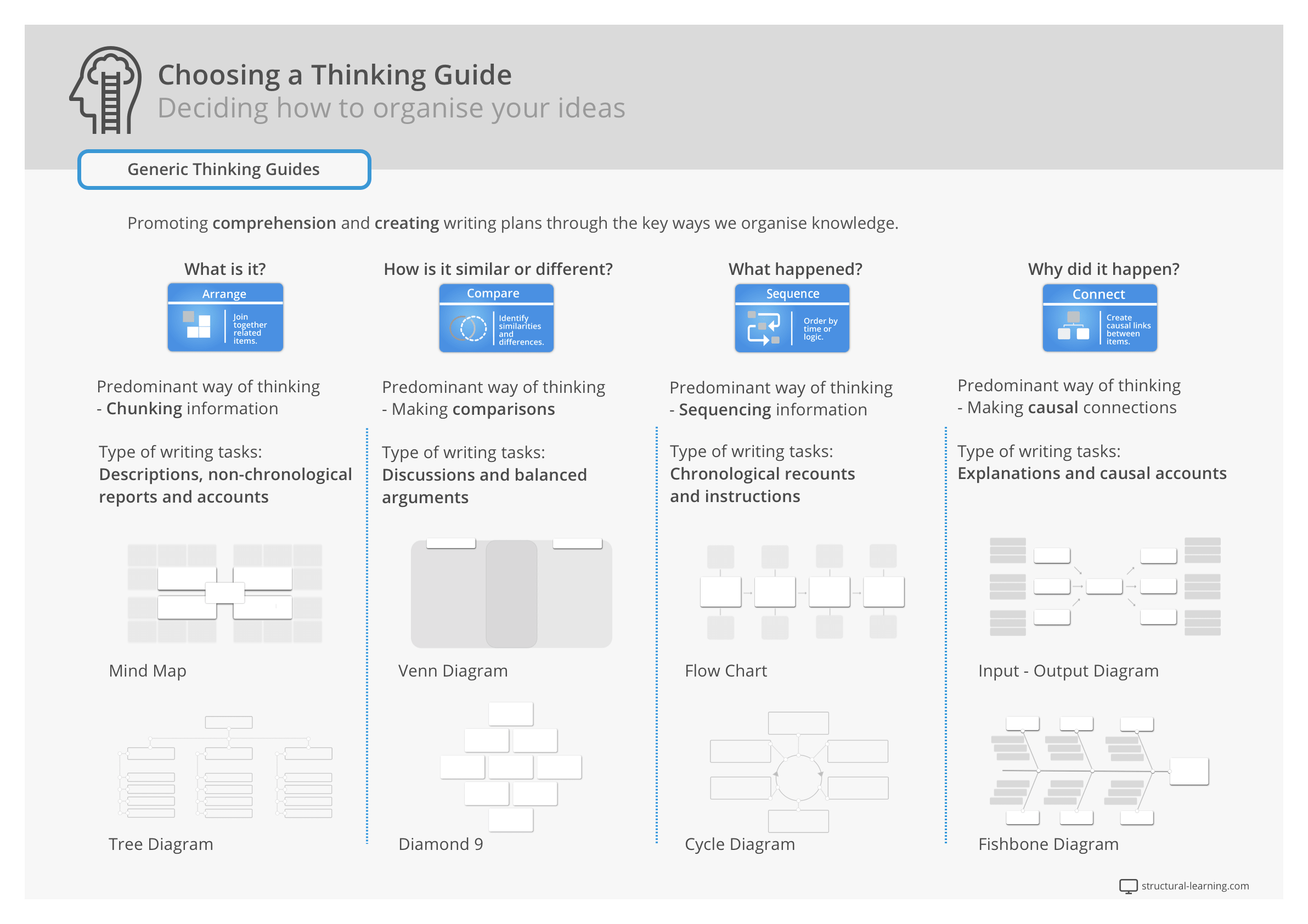

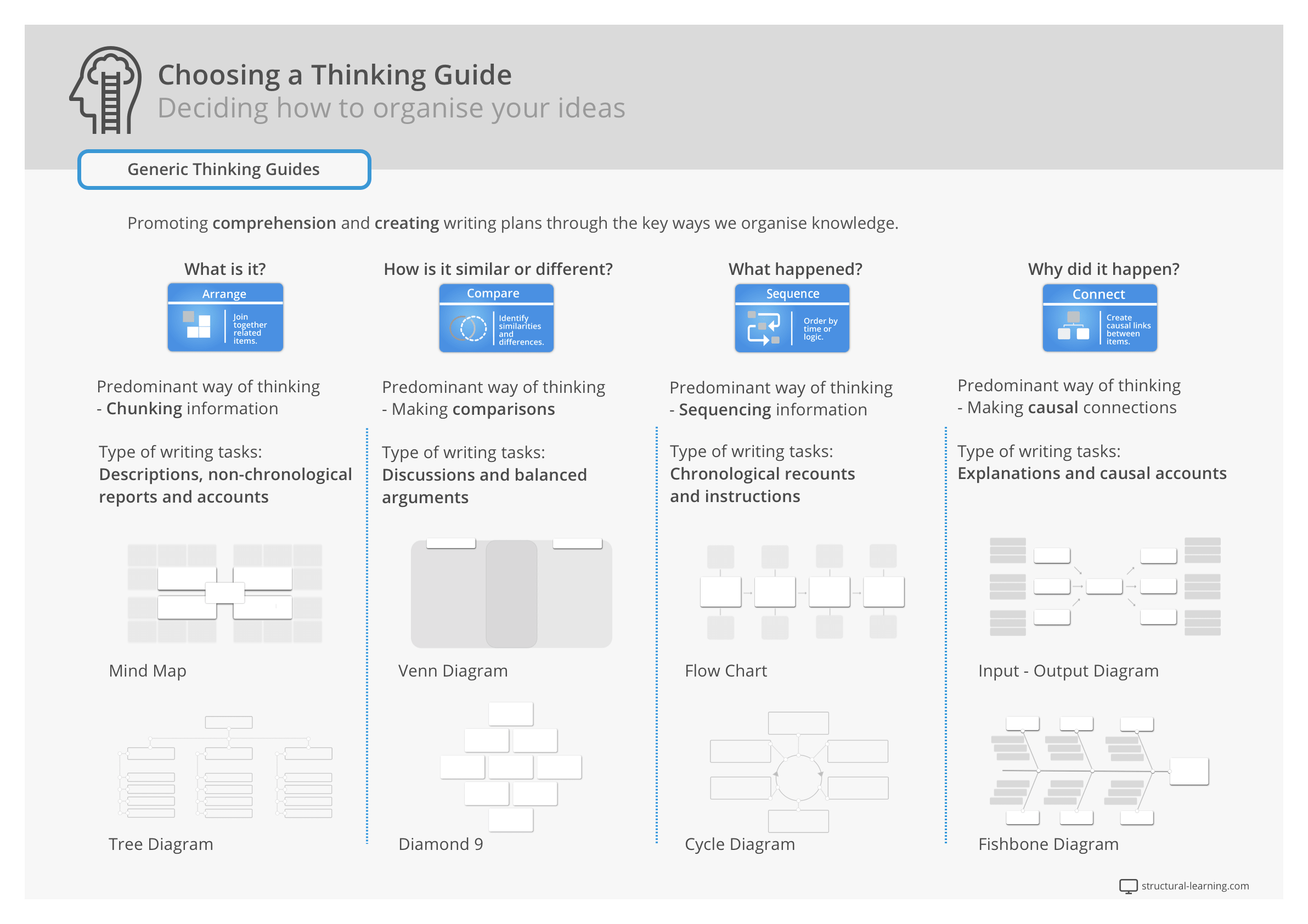

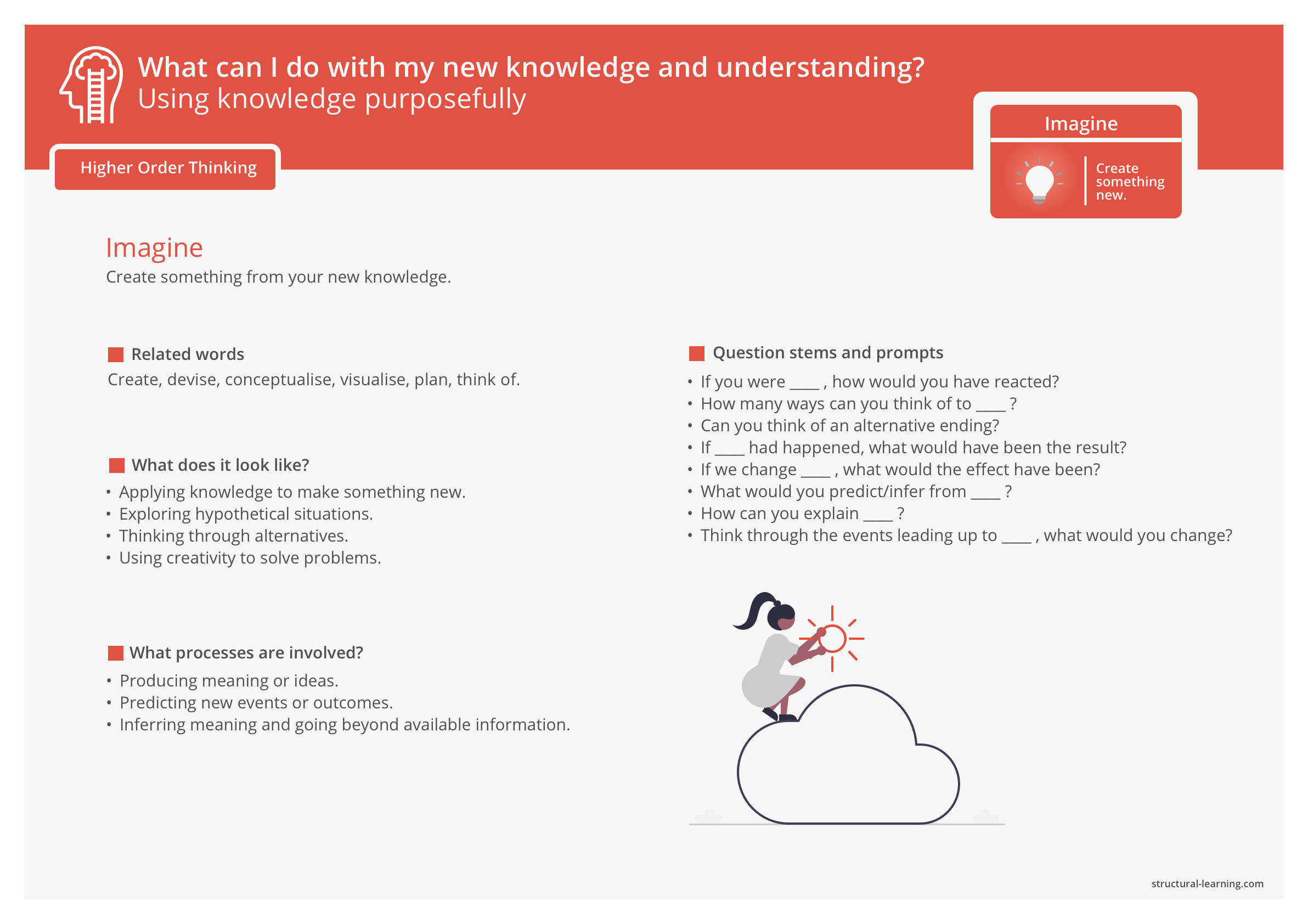

The implications for classroom practise are profound. If we can scaffold the cognitive function of a child at an appropriate level, we can enable them to advance their learning and develop new skills. In a classroom setting, we want to improve both access to the curriculum and the level of challenge. Our alternative approach to lesson planning and delivery using the universal thinking framework enables educators to fully embrace this philosophy.

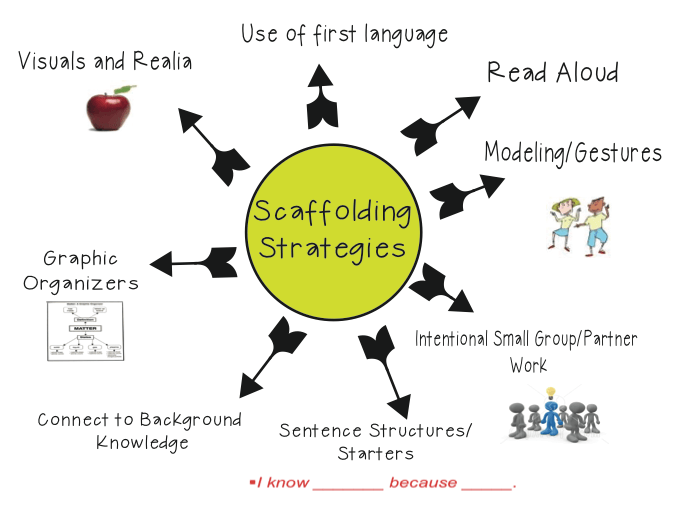

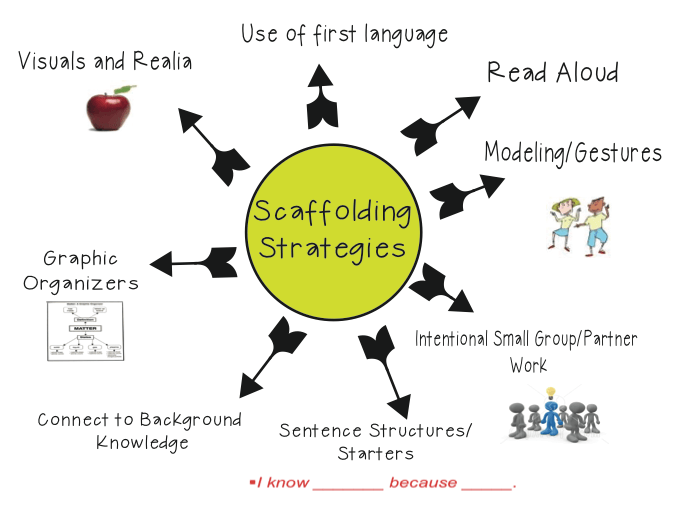

Scaffolding is the instructional technique used to support students working within their ZPD, providing temporary assistance that is gradually removed as competence increases. Teachers scaffold by breaking complex tasks into manageable steps, offering prompts, and modelling strategies while students develop independence. The key is matching support level to the student's current ZPD to prevent over-reliance on help.

The concept of pairing guidance with a student is termed scaffolding. The ZPD is frequently used in the literature as the term scaffolding. But, it is must be remembered that Vygotsky never used this word in his writing, and it was first used by Wood, Brunerand Ross (1976). The individual performing the scaffolding can be a peer, a teacher, or even a parent. To help students gain independence, Wood, Bruner and Ross (1976) defined support and supervision offered by a more capable or knowledgeable person (instructor or parent) to perform a task that the child would not be able to perform independently.

Students take easy and manageable steps to achieve a goal. Working in partnership with more knowledgeable peers or a skilled instructor will help learners in making connections between different concepts.

As students thrive within their zone of proximal development and come to be more confident, they perform new tasks using the social support that exists around them. Vygotsky proposed that learning takes place using meaningful and purposeful interactions with others. We have been embracing this learning theory within our concept of mental modelling. This collaborative learning approach enables students to take their thinking out of their head where they have more capacity.

Using brightly coloured blocks, students organise their thoughts and develop new ideas.Uses of this methodology take their current knowledge and build on it with others (quite literally). Their previous knowledge acts as a foundation for increasing their conceptual understanding of the topic in question. The students level of knowledge is reflected within the sophistication of the structure of their build. When students are in the 'zone', their learning potential is significantly increased.

Graphic organisers as a scaffolding tool" width="auto" height="auto" id="">

Graphic organisers as a scaffolding tool" width="auto" height="auto" id="">This approach to classroom learning makes activities such as language learning more engaging and at the same time more challenging. The incremental nature of block building means that a student working memory is rarely overloaded. The level of flexibility within the strategy means that it can be used for discovery learning or at the other end of the spectrum, direct instruction approaches.

The blocks can be used to make abstract concepts more concrete. The connections between concepts can be illustrated using the connections between the blocks. This visual queue acts as a 'memory anchor' that serves as a retrieval aid. This process is a perfect example of the concept of scaffolding.

Teachers plan ZPD-based lessons by first conducting pre-assessments to identify each student's current independent level and potential with support. They then design differentiated activities that target the space between these levels, incorporating peer collaboration and teacher guidance. Lesson objectives should stretch students just beyond comfort while providing clear scaffolds for success.

Classroom learning should be challenging enough to be engaging and the concept of proximal development comes in very useful when thinking about activities such as lesson planning. If we can break classroom tasks down into manageable chunks, with the correct adult assistance, we can enable a pupil to think their way through most challenges. Improving access to education is a global goal we all share.

Our community of practise has demonstrated how this can be achieved by utilising the latest thinking in cognitive science. You don't need to be a professor of education to embrace powerful psychological p rinciples of the mind. Instructional concepts such as dual coding, mind-mapping and oracy all enable children to push the boundaries of what they are capable of. The adult becomes the facilitator instead of the deliverer of knowledge construction.

Assisted problem solving occurs when a more knowledgeable person guides a learner through challenges they cannot solve independently but can master with help. This process involves strategic questioning, hints, and demonstrations that help learners discover solutions rather than providing direct answers. The assistance gradually decreases as the learner internalizes problem-solving strategies and moves towards independence.

Wood and Middleton (1975) examined the interaction between 4-year-old children and their mothers in a problem-solving situation. The children had to use a set of pegs and blocks to create a3D model using a picture. The task was too difficult for these children to complete on their own.

Wood and Middleton (1975) evaluated how mothers assisted their children to create the 3D model. Different kinds of support included:

This study revealed that no single strategy was sufficient to help each child to progress. Mothers, who modified their help according to their children's performance were found to be the most successful. When these mothers saw their children doing well, they reduced their level of help. When they saw their child began to struggle, they increased their level of help by providing specific instructions until the child showed progress again.

This study illustrates Vygotsky's concept of the ZPD and scaffolding. Scaffolding (or guidance) is most beneficial when the support is according to the specific needs of a child. This puts a child in a position to gain success in an activity that he would not have been able to do in the past.

Wood et al. (1976) mentioned some processes that help effective scaffolding:

ZPD theory implies teachers must continuously assess individual student capabilities and adjust instruction to match their changing developmental needs. It emphasises the importance of collaborative learning, peer tutoring, and flexible grouping based on skill levels rather than age. Teachers must also recognise that effective learning requires social interaction and cannot occur through passive reception of information.

Vygotsky argues that the role of education is to provide those experiences to children which are in their ZPD, thereby advancing and encouraging their knowledge. Vygotsky believes that the teachers are like a mediator in the children's learning activity as they share information through social interaction.

Vygotsky perceived interaction with peers as a helpful way to build skills. He implies that for children with low competence teachers need to use cooperative learning strategies and they must seek help from more competent peers in the zone of proximal development.

Scaffolding is a significant component of effective teaching, in which the more competent individual continually modifies the level of his help according to the learner's performance level. Scaffolding in the classroom may include modelling a talent, providing cues or hints, and adapting activity or material. Teachers need to consider the following guidelines for scaffolding instruction.

A current application of Vygotsky's concepts is "reciprocal teaching," used to enhance students' ability to memorize from the text. In this type of teaching, educator and learners collaborate to memorize and practise four major skills: predicting, clarifying, questioning, and summarising. The role of a teacher in this process is decreased over time.

Vygotsky's theories also address the recent interest in collaborative learning, implying that group members mostly have different levels of talent so more advanced peers must help less advanced students within their zone of proximal development.

Practical ZPD applications include reciprocal teaching where students take turns leading discussions, think-aloud protocols where teachers model cognitive processes, and peer tutoring with strategic pairing. Other examples involve using manipulatives in maths that students gradually abandon, providing sentence starters that fade over time, and implementing collaborative problem-solving tasks. Each strategy targets the space between independent and potential achievement levels.

In the field of educational psychology, the area in which a learner can achieve with guidance a concept that has been embraced by educatorsand learners alike. It's a theoretical space where learners can achieve more with guidance and support than they could independently. Here are nine fictional examples of how ZPD can be utilised to advance the learning process:

These examples demonstrate the power of the ZPD in facilitating learning across a range of contexts. By providing the right level of support at the right time, educators can guide learners to new levels of achievement.

Key Insights:

Teachers assess ZPD progress through dynamic assessment, observing what students can achieve with varying levels of support rather than just independent performance. They use formative assessments, learning journals, and scaffolded tasks to track movement from assisted to independent performance. Regular observation of peer interactions and the amount of support needed provides insight into each student's developmental trajectory.

Assessing learners' progress through the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) requires a nuanced understanding of each student's developmental level, taking into account their potential development as well as their current level of competence. Rooted in sociocultural theory, the ZPD concept emphasises the dynamic interplay between a child's individual mental development and their social environment, particularly in a classroom setting.

To effectively evaluate childhood learning and growth within the ZPD, teachers must first determine a student's level of knowledge and skill in relation to the learning task at hand. This assessment should consider the level of difficulty a student can manage independently, as well as their potential level when guided by a knowledgeable peer or adult. By identifying this range, educators can design learning tasks and scaffold instruction to maximise each student's potential development.

recognise that the ZPD is not static; rather, it evolves as a student's learning outcomes and level of competence change. Therefore, ongoing assessments should be implemented to monitor progress and adjust instructional strategies accordingly. Teachers can utilise a variety of assessment methods, such as formative assessments, observation, and student self-assessments, to gauge a student's current level and potential within the ZPD.

By thoughtfully assessing learners' progress within the Zone of Proximal Development, teachers can create a classroom environment that creates optimal mental development, helping students to thrive as they navigate new challenges and acquire increasingly complex skills.

Key resources include Vygotsky's original work 'Mind in Society' and contemporary texts like 'Scaffolding Children's Learning' by Berk and Winsler. Educational psychology journals regularly publish ZPD research, while practical guides like Wood's 'How Children Think and Learn' offer classroom applications. Online platforms including educational research databases provide access to current studies and implementation strategies.

Here are five key research papers on the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). These studies provide comprehensive insights into ZPD, highlighting its impact on educational processes, teacher development, and child learning.

1. Re/Thinking the Zone of Proximal Development by Wolff‐Michael Roth and L. Radford (2011)

This paper revisits the ZPD, emphasising its application in understanding and promoting child development through interaction with skilled partners and adult guidance. It highlights the significance of ZPD in both theoretical and practical aspects of education.

2. The Zone of Proximal Teacher Development by Mark K. Warford (2011)

Warford's study integrates Vygotskyan theory into Western education models, creating the Zone of Proximal Teacher Development (ZPTD). It offers curriculum recommendations to enhance teacher development, aligning with the principles of ZPD and focusing on individual student's learning outcomes.

3. Current Activity for the Future: The Zo‐ped by P. Griffin and M. Cole (1984)

Griffin and Cole explore ZPD in the context of childhood learning activities, highlighting how it aids in the development of cognitive and social skills. The study discusses the reciprocal teaching and learning processes within ZPD.

4. The Cultural-Historical Foundations of the Zone of Proximal Development by E. Kravtsova (2009)

This paper examines into the cultural-historical roots of ZPD, discussing its influence on developmental education. Kravtsova emp hasises the use of neoformations and leading activity as key indicators in child development assessments.

5. Proximity as a Window into the Zone of Proximal Development by Brendan Jacobs and A. Usher (2018)

Jacobs and Usher illustrate how digital technologies can enhance project-based learning within the ZPD. Their study shows the effective use of proximity technology in primary education to facilitate conceptual consolidation and collaborative learning.

These studies provide comprehensive insights into ZPD, highlighting its impact on educational processes, teacher development, and child learning.

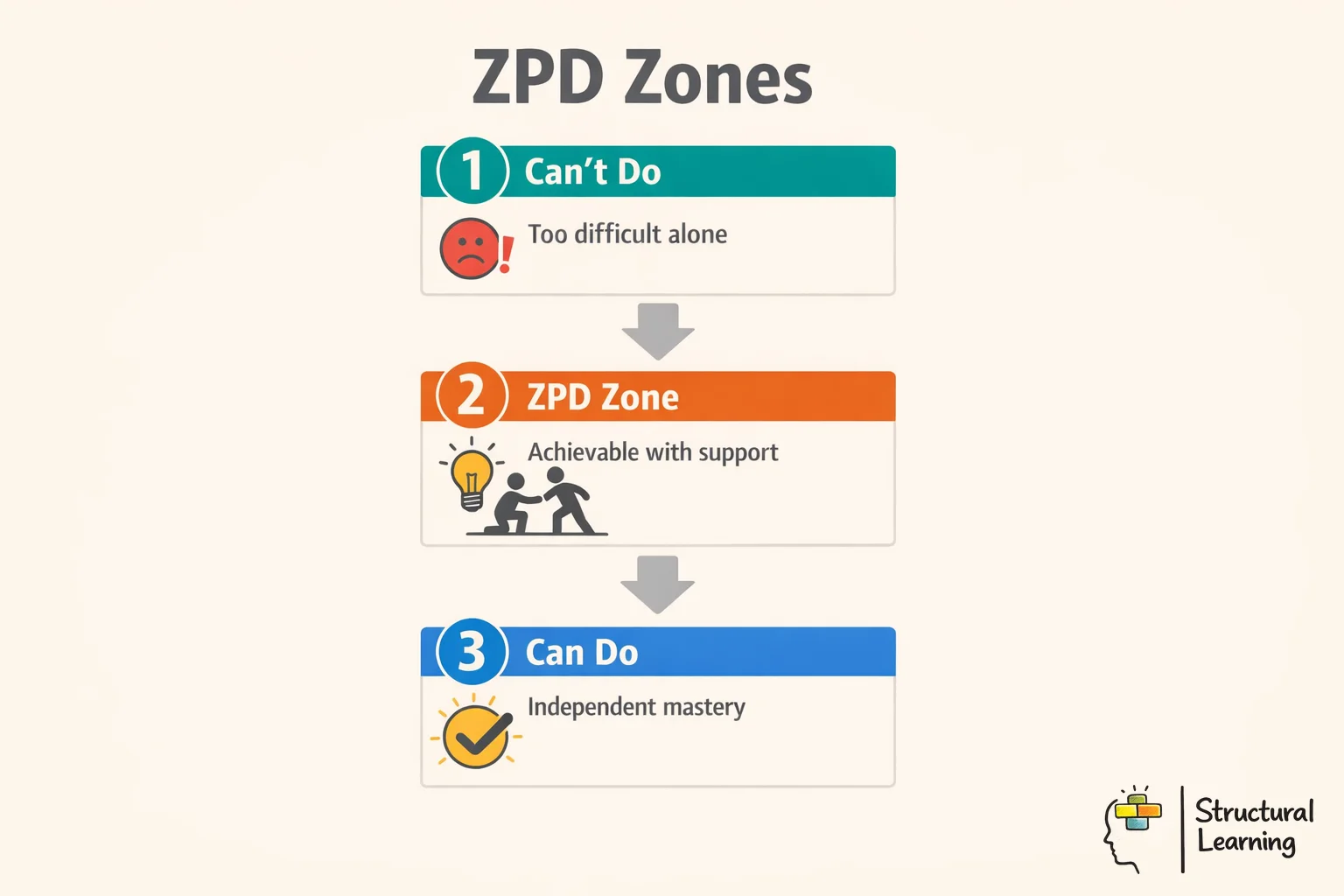

| Zone | Definition | Student Experience | Teacher Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zone of Actual Development | What the learner can do independently without any assistance | Confident, automatic, may become bored if work stays here too long | Use for warm-ups, confidence building, fluency practise; don't over-rely on this zone |

| Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) | What the learner can achieve with guidance from a more knowledgeable other (MKO) | Challenged but capable with support; productive struggle; "I can do this with help" | Provide scaffolding, model thinking, use guided practise, peer collaboration, timely feedback |

| Zone of Frustration | What the learner cannot do even with maximum assistance, beyond current reach | Anxious, overwhelmed, may shut down or act out; "This is impossible" | Reduce task complexity, backfill prerequisite skills, break into smaller steps, reassess readiness |

Based on Vygotsky's sociocultural theory of cognitive development (1978). The ZPD represents the optimal zone for learning, where tasks are challenging enough to promote growth but achievable with appropriate support.

These evidence-based ZPD strategies help teachers identify each student's optimal challenge level and provide the right support at the right time. When teaching targets the zone of proximal development, students experience productive struggle that builds competence, confidence, and independence.

The zone of proximal development reframes teaching as the art of finding the "Goldilocks zone", tasks that are neither too easy (boring, no growth) nor too hard (frustrating, no success). When students consistently work within their ZPD with appropriate support that is gradually withdrawn, they develop both competence and confidence. The ultimate goal is expanding what students can do independently, moving yesterday's ZPD into today's zone of actual development.

The range within which a learner can develop further the difference between what learners can do independently and what they can achieve with guidance from a more knowledgeable person. It represents the optimal learning space where tasks are neither too easy nor too challenging, making it crucial for teachers to design activities that stretch students' capabilities just beyond their current capacity. Understanding ZPD helps educators provide the right level of support to promote cognitive growth and transform struggling learners into confident achievers.

Teachers can identify a student's ZPD by first assessing what the student can do independently, then observing what they can accomplish with minimal guidance or support. This involves designing activities slightly beyond the student's current ability level and noting where they need assistance. The key is finding that sweet spot where students are challenged but not overwhelmed, requiring some scaffolding to succeed.

The scaffolding trap occurs when teachers accidentally provide too much support, which can actually stunt student growth rather than promote it. Teachers fall into this trap by not withdrawing help at the right moment, keeping students dependent on guidance rather than developing independence. To avoid this, educators must gradually reduce their assistance as students become more capable, timing the withdrawal of support precisely to encourage autonomous learning.

Teachers can strategically pair students based on their ZPD levels, allowing more knowledgeable peers to act as skilled partners for those who need support. This peer power approach can create learning breakthroughs that teacher instruction alone cannot achieve, as students often relate well to explanations from classmates. The key is thoughtful pairing that ensures the more capable student can provide appropriate guidance whilst both learners benefit from the collaborative experience.

Cultural context significantly influences how students respond to ZPD approaches because learning is deeply rooted in social and cultural interactions. For English as an Additional Language (EAL) pupils, standard ZPD approaches might miss the mark if they don't consider cultural learning styles, communication patterns, and background knowledge. Teachers need to adapt their scaffolding and support strategies to be culturally responsive, ensuring that the guidance provided aligns with students' cultural contexts and experiences.

Practical ZPD activities include collaborative problem-solving tasks where students work with more capable peers, guided reading sessions where teachers provide decreasing levels of support, and modelling techniques followed by independent practise. Teachers might also use questioning strategies that prompt thinking just beyond students' current level, or create learning stations with varying difficulty levels. The key is ensuring each activity requires some guidance initially but allows students to gradually work towards independence.

Teachers should reduce scaffolding when students begin to demonstrate increased confidence and accuracy in their attempts, showing signs they can apply the skills or knowledge with minimal prompts. The timing is crucial, support should be withdrawn gradually as students show they can self-regulate and use the internalised knowledge to improve their performance. Educators need to carefully observe student behaviour and responses to determine the precise moment when less guidance will promote rather than hinder learning progress.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into the zone of proximal development: a teacher's guide and its application in educational settings.

This comprehensive literature review of online teaching during COVID-19 759 citations (Author, Year) examines how teacher education programmes adapted to remote learning practices, analysing the effectiveness of digital pedagogical approaches and identifying key challenges faced by educators transitioning to virtual classroom environments during the pandemic.

Carrillo et al. (2020)

This paper reviews how COVID-19 forced teacher education programmes to rapidly transition from face-to-face to online teaching methods. It examines the challenges and adaptations made in preparing student teachers through remote learning environments. Teachers can apply insights about scaffolding and support strategies used during this transition to better understand how to adjust their zone of proximal development approaches when working with students in different learning contexts.

An autoethnographic study exploring language transitions in science education (Author, Year) traces the process from learning biology as a student to teaching biology as an educator, examining how language use and understanding evolves throughout this professional development process.

Fernando et al. (2021)

This autoethnographic study explores one educator's process from being an English as Additional Language student to becoming a science teacher and researcher. It examines how language learning experiences shaped the author's identity and teaching practices across multiple cultural contexts. Teachers working with EAL students can gain insights into how to recognise and build upon students' diverse linguistic backgrounds when establishing appropriate zones of proximal development.

Teachers’ perceptions about their work with EAL/D students in a standards-based educational context. 5 citations

Nguyen et al. (2023)

This research investigates teachers' perspectives on working with English as Additional Language or Dialect students within Australia's standards-based education system. It explores how teachers navigate the challenges of supporting linguistically diverse learners while meeting curriculum requirements. The findings help teachers understand how to appropriately assess and scaffold learning for EAL/D students by considering their unique starting points when determining their zone of proximal development.

This editorial examining teaching EAL/D learners across subjects 2 citations (Author, Year) explores pedagogical approaches and strategies for supporting English as an Additional Language or Dialect students in mainstream curriculum areas, highlighting the importance of integrated language and content instruction.

This editorial introduces a special issue focusing on teaching English as Additional Language or Dialect learners across different subject areas in Australian schools. It brings together various perspectives on supporting EAL/D students in mainstream educational environments. Teachers can use these insights to better understand how to adapt their instructional approaches and identify appropriate zones of proximal development for linguistically diverse students across all curriculum areas.Research on preparing mainstream teachers for diverse classrooms 3 citations (Author, Year) examines the implications for Initial Teacher Education programmes in developing educators' capacity to effectively support culturally and linguistically diverse student populations in mainstream educational settings.

Smith et al. (2023)

This paper examines how Initial Teacher Education programmes can better prepare mainstream teachers to work effectively with culturally and linguistically diverse students. It addresses the gap between teacher preparation and the reality of supporting EAL/D learners without specialised language support. The research provides valuable guidance for teachers on recognising and responding to the diverse learning needs and starting points of EAL/D students when establishing their zones of proximal development.

Every day in your classroom, you witness the perfect teaching moment: a student struggles with a concept independently but grasps it immediately with just the right hint or guidance. This is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) in action, and learning to recognise and harness these moments can transform your teaching effectiveness. Rather than guessing when to step in or step back, you can use specific strategies to identify each student's ZPD and create targeted learning experiences that challenge without overwhelming. The key lies in knowing exactly what to look for and how to respond.

At its core, the ZPD represents the difference between what learners can do independently, which is their level of development, and what they can achieve with guidance, their potential level. This concept is essential in designing supportive activities that stretch a student's capabilities just beyond their current capacity, building on supportive relationshipsto promote cognitive growth.

Within the ZPD, learning is neither too easy nor too challenging; it's in this 'zone' that the most effective learning takes place. It acknowledges the dynamic nature of learning, advocating for tailored support that considers cultural contexts and individual learner differences. By providing optimal challenges and scaffolding, educators can help students build upon their existing knowledge and skills.

As we examine deeper into this article, we will explore how educators can identify a student's ZPD and use it to facilitate learning that is both engaging and transformative. We will also consider how the application of the ZPD can be adapted to various cultural contexts, ensuring that the potential level of cognitive development can be reached through culturally responsive teachingmethods.

The zone of proximal development indicates the difference between what a student can do without guidance and what he can achieve with the encouragement and guidance of a skilled partner. Therefore, the term “proximal” relates to those skills that the student is “close” to mastering. This theory of learning can be useful for teachers.

Reflective Questions

1. How does ZPD relate to other concepts such as scaffolding or peer tutoring?

2. Why are some students better at using this approach than others?

3. Can you think of any situations where it would be useful for teachers to use this strategy?

4. Is there anything else we should know about ZPD?

5. Do you have any ideas on how to implement this strategy into your own teaching practise?

The Zone of Proximal Development was developed by Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky in the 1930s as part of his sociocultural theory of cognitive development. Vygotsky introduced the concept to explain how children learn best through social interaction with more knowledgeable others, contrasting with Piaget's view that development precedes learning. The theory gained widespread recognition in Western education during the 1970s and 1980s.

The historical development of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is anchored in the work of Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky, whose ideas transformed educational theory and child psychology. Vygotsky, in the early 20th century, proposed the ZPD against the backdrop of a burgeoning interest in the analysis of learning and cognitive ability.

His theory suggested that children's development is profoundly influenced by their cultural context and the skilled partners in their learning environment.

Vygotsky's pioneering work was largely conducted at the Institute of Psychology in Moscow, where he posited that learning precedes development, a concept that stood in contrast to the prevailing views of the time.

This perspective underscored the importance of social interaction in the development of cognition. Vygotsky observed that through collaborative dialogue and problem-solving with more knowledgeable others, whether teachers, peers, or parents, children could achieve a higher level of understanding and skill than they could independently.

The legacy of Vygotsky's work, particularly the ZPD, has been widely disseminated through a range of universities worldwide. Scholars have expanded on his concepts, exploring the intricacies of how social factors contribute to cognitive development in children.

Western universities have often been the site of rich academic discourse on the subject, with researchers in the United States and Europe analysing and applying Vygotsky's theories within diverse educational settings.

As part of the broad spectrum of child development theories, the ZPD remains a cornerstone of contemporary educational psychology. It has inspired a wide range of instructional strategies that aim to improve learning by matching challenges to a child's current capabilities while also stretching them into the field of potential development.

The historical and ongoing research into the ZPD underscores its significance as a tool for understanding how to effectively support the cognitive and academic growth of children across various cultural and educational landscapes.

How Does It Work?

When a learner needs assistance, they ask their peers or instructors for advice. The instructor provides feedback based on the learner's performance. This helps them learn new strategies and techniques. As the learner masters these new skills, the instructor gradually reduces her involvement until she no longer offers direct instruction. At this point, the learner is capable of performing the activity independently.

Teachers use ZPD by first assessing what students can do independently, then designing activities slightly beyond their current ability level that require guidance. They provide support through modelling, questioning, and collaborative work, gradually reducing assistance as students become more capable. This approach ensures students are challenged but not overwhelmed, maximising learning potential.

To help a student to move through the zone of proximal development, teachers must focus on three essential components that facilitate the learning process:

The zone of proximal development (ZPD), is an educational notion constantly restated by the professors in the lecture halls. However, why is it so crucial in a classroom setting for a childs mental development? The crux of the zone of proximal development is that a child with more skills and mastery (the skilled partner), can be used to enhance the potential level of knowledge and another individual.

These type of social interactions can be used to enhance educational outcomes in problem-based learning activities. The level of challenge can be incrementally increased with appropriate levels of scaffolding in a way that neither individual feels overwhelmed by the complexity of the task.

This type of social interaction can be used as a catalyst for critical thinking. The interaction with peers enables children to engage cognitively at much higher levels.

The implications for classroom practise are profound. If we can scaffold the cognitive function of a child at an appropriate level, we can enable them to advance their learning and develop new skills. In a classroom setting, we want to improve both access to the curriculum and the level of challenge. Our alternative approach to lesson planning and delivery using the universal thinking framework enables educators to fully embrace this philosophy.

Scaffolding is the instructional technique used to support students working within their ZPD, providing temporary assistance that is gradually removed as competence increases. Teachers scaffold by breaking complex tasks into manageable steps, offering prompts, and modelling strategies while students develop independence. The key is matching support level to the student's current ZPD to prevent over-reliance on help.

The concept of pairing guidance with a student is termed scaffolding. The ZPD is frequently used in the literature as the term scaffolding. But, it is must be remembered that Vygotsky never used this word in his writing, and it was first used by Wood, Brunerand Ross (1976). The individual performing the scaffolding can be a peer, a teacher, or even a parent. To help students gain independence, Wood, Bruner and Ross (1976) defined support and supervision offered by a more capable or knowledgeable person (instructor or parent) to perform a task that the child would not be able to perform independently.

Students take easy and manageable steps to achieve a goal. Working in partnership with more knowledgeable peers or a skilled instructor will help learners in making connections between different concepts.

As students thrive within their zone of proximal development and come to be more confident, they perform new tasks using the social support that exists around them. Vygotsky proposed that learning takes place using meaningful and purposeful interactions with others. We have been embracing this learning theory within our concept of mental modelling. This collaborative learning approach enables students to take their thinking out of their head where they have more capacity.

Using brightly coloured blocks, students organise their thoughts and develop new ideas.Uses of this methodology take their current knowledge and build on it with others (quite literally). Their previous knowledge acts as a foundation for increasing their conceptual understanding of the topic in question. The students level of knowledge is reflected within the sophistication of the structure of their build. When students are in the 'zone', their learning potential is significantly increased.

Graphic organisers as a scaffolding tool" width="auto" height="auto" id="">

Graphic organisers as a scaffolding tool" width="auto" height="auto" id="">This approach to classroom learning makes activities such as language learning more engaging and at the same time more challenging. The incremental nature of block building means that a student working memory is rarely overloaded. The level of flexibility within the strategy means that it can be used for discovery learning or at the other end of the spectrum, direct instruction approaches.

The blocks can be used to make abstract concepts more concrete. The connections between concepts can be illustrated using the connections between the blocks. This visual queue acts as a 'memory anchor' that serves as a retrieval aid. This process is a perfect example of the concept of scaffolding.

Teachers plan ZPD-based lessons by first conducting pre-assessments to identify each student's current independent level and potential with support. They then design differentiated activities that target the space between these levels, incorporating peer collaboration and teacher guidance. Lesson objectives should stretch students just beyond comfort while providing clear scaffolds for success.

Classroom learning should be challenging enough to be engaging and the concept of proximal development comes in very useful when thinking about activities such as lesson planning. If we can break classroom tasks down into manageable chunks, with the correct adult assistance, we can enable a pupil to think their way through most challenges. Improving access to education is a global goal we all share.

Our community of practise has demonstrated how this can be achieved by utilising the latest thinking in cognitive science. You don't need to be a professor of education to embrace powerful psychological p rinciples of the mind. Instructional concepts such as dual coding, mind-mapping and oracy all enable children to push the boundaries of what they are capable of. The adult becomes the facilitator instead of the deliverer of knowledge construction.

Assisted problem solving occurs when a more knowledgeable person guides a learner through challenges they cannot solve independently but can master with help. This process involves strategic questioning, hints, and demonstrations that help learners discover solutions rather than providing direct answers. The assistance gradually decreases as the learner internalizes problem-solving strategies and moves towards independence.

Wood and Middleton (1975) examined the interaction between 4-year-old children and their mothers in a problem-solving situation. The children had to use a set of pegs and blocks to create a3D model using a picture. The task was too difficult for these children to complete on their own.

Wood and Middleton (1975) evaluated how mothers assisted their children to create the 3D model. Different kinds of support included:

This study revealed that no single strategy was sufficient to help each child to progress. Mothers, who modified their help according to their children's performance were found to be the most successful. When these mothers saw their children doing well, they reduced their level of help. When they saw their child began to struggle, they increased their level of help by providing specific instructions until the child showed progress again.

This study illustrates Vygotsky's concept of the ZPD and scaffolding. Scaffolding (or guidance) is most beneficial when the support is according to the specific needs of a child. This puts a child in a position to gain success in an activity that he would not have been able to do in the past.

Wood et al. (1976) mentioned some processes that help effective scaffolding:

ZPD theory implies teachers must continuously assess individual student capabilities and adjust instruction to match their changing developmental needs. It emphasises the importance of collaborative learning, peer tutoring, and flexible grouping based on skill levels rather than age. Teachers must also recognise that effective learning requires social interaction and cannot occur through passive reception of information.

Vygotsky argues that the role of education is to provide those experiences to children which are in their ZPD, thereby advancing and encouraging their knowledge. Vygotsky believes that the teachers are like a mediator in the children's learning activity as they share information through social interaction.

Vygotsky perceived interaction with peers as a helpful way to build skills. He implies that for children with low competence teachers need to use cooperative learning strategies and they must seek help from more competent peers in the zone of proximal development.

Scaffolding is a significant component of effective teaching, in which the more competent individual continually modifies the level of his help according to the learner's performance level. Scaffolding in the classroom may include modelling a talent, providing cues or hints, and adapting activity or material. Teachers need to consider the following guidelines for scaffolding instruction.

A current application of Vygotsky's concepts is "reciprocal teaching," used to enhance students' ability to memorize from the text. In this type of teaching, educator and learners collaborate to memorize and practise four major skills: predicting, clarifying, questioning, and summarising. The role of a teacher in this process is decreased over time.

Vygotsky's theories also address the recent interest in collaborative learning, implying that group members mostly have different levels of talent so more advanced peers must help less advanced students within their zone of proximal development.

Practical ZPD applications include reciprocal teaching where students take turns leading discussions, think-aloud protocols where teachers model cognitive processes, and peer tutoring with strategic pairing. Other examples involve using manipulatives in maths that students gradually abandon, providing sentence starters that fade over time, and implementing collaborative problem-solving tasks. Each strategy targets the space between independent and potential achievement levels.

In the field of educational psychology, the area in which a learner can achieve with guidance a concept that has been embraced by educatorsand learners alike. It's a theoretical space where learners can achieve more with guidance and support than they could independently. Here are nine fictional examples of how ZPD can be utilised to advance the learning process:

These examples demonstrate the power of the ZPD in facilitating learning across a range of contexts. By providing the right level of support at the right time, educators can guide learners to new levels of achievement.

Key Insights:

Teachers assess ZPD progress through dynamic assessment, observing what students can achieve with varying levels of support rather than just independent performance. They use formative assessments, learning journals, and scaffolded tasks to track movement from assisted to independent performance. Regular observation of peer interactions and the amount of support needed provides insight into each student's developmental trajectory.

Assessing learners' progress through the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) requires a nuanced understanding of each student's developmental level, taking into account their potential development as well as their current level of competence. Rooted in sociocultural theory, the ZPD concept emphasises the dynamic interplay between a child's individual mental development and their social environment, particularly in a classroom setting.

To effectively evaluate childhood learning and growth within the ZPD, teachers must first determine a student's level of knowledge and skill in relation to the learning task at hand. This assessment should consider the level of difficulty a student can manage independently, as well as their potential level when guided by a knowledgeable peer or adult. By identifying this range, educators can design learning tasks and scaffold instruction to maximise each student's potential development.

recognise that the ZPD is not static; rather, it evolves as a student's learning outcomes and level of competence change. Therefore, ongoing assessments should be implemented to monitor progress and adjust instructional strategies accordingly. Teachers can utilise a variety of assessment methods, such as formative assessments, observation, and student self-assessments, to gauge a student's current level and potential within the ZPD.

By thoughtfully assessing learners' progress within the Zone of Proximal Development, teachers can create a classroom environment that creates optimal mental development, helping students to thrive as they navigate new challenges and acquire increasingly complex skills.

Key resources include Vygotsky's original work 'Mind in Society' and contemporary texts like 'Scaffolding Children's Learning' by Berk and Winsler. Educational psychology journals regularly publish ZPD research, while practical guides like Wood's 'How Children Think and Learn' offer classroom applications. Online platforms including educational research databases provide access to current studies and implementation strategies.

Here are five key research papers on the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). These studies provide comprehensive insights into ZPD, highlighting its impact on educational processes, teacher development, and child learning.

1. Re/Thinking the Zone of Proximal Development by Wolff‐Michael Roth and L. Radford (2011)

This paper revisits the ZPD, emphasising its application in understanding and promoting child development through interaction with skilled partners and adult guidance. It highlights the significance of ZPD in both theoretical and practical aspects of education.

2. The Zone of Proximal Teacher Development by Mark K. Warford (2011)

Warford's study integrates Vygotskyan theory into Western education models, creating the Zone of Proximal Teacher Development (ZPTD). It offers curriculum recommendations to enhance teacher development, aligning with the principles of ZPD and focusing on individual student's learning outcomes.

3. Current Activity for the Future: The Zo‐ped by P. Griffin and M. Cole (1984)

Griffin and Cole explore ZPD in the context of childhood learning activities, highlighting how it aids in the development of cognitive and social skills. The study discusses the reciprocal teaching and learning processes within ZPD.

4. The Cultural-Historical Foundations of the Zone of Proximal Development by E. Kravtsova (2009)

This paper examines into the cultural-historical roots of ZPD, discussing its influence on developmental education. Kravtsova emp hasises the use of neoformations and leading activity as key indicators in child development assessments.

5. Proximity as a Window into the Zone of Proximal Development by Brendan Jacobs and A. Usher (2018)

Jacobs and Usher illustrate how digital technologies can enhance project-based learning within the ZPD. Their study shows the effective use of proximity technology in primary education to facilitate conceptual consolidation and collaborative learning.

These studies provide comprehensive insights into ZPD, highlighting its impact on educational processes, teacher development, and child learning.

| Zone | Definition | Student Experience | Teacher Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zone of Actual Development | What the learner can do independently without any assistance | Confident, automatic, may become bored if work stays here too long | Use for warm-ups, confidence building, fluency practise; don't over-rely on this zone |

| Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) | What the learner can achieve with guidance from a more knowledgeable other (MKO) | Challenged but capable with support; productive struggle; "I can do this with help" | Provide scaffolding, model thinking, use guided practise, peer collaboration, timely feedback |

| Zone of Frustration | What the learner cannot do even with maximum assistance, beyond current reach | Anxious, overwhelmed, may shut down or act out; "This is impossible" | Reduce task complexity, backfill prerequisite skills, break into smaller steps, reassess readiness |

Based on Vygotsky's sociocultural theory of cognitive development (1978). The ZPD represents the optimal zone for learning, where tasks are challenging enough to promote growth but achievable with appropriate support.

These evidence-based ZPD strategies help teachers identify each student's optimal challenge level and provide the right support at the right time. When teaching targets the zone of proximal development, students experience productive struggle that builds competence, confidence, and independence.

The zone of proximal development reframes teaching as the art of finding the "Goldilocks zone", tasks that are neither too easy (boring, no growth) nor too hard (frustrating, no success). When students consistently work within their ZPD with appropriate support that is gradually withdrawn, they develop both competence and confidence. The ultimate goal is expanding what students can do independently, moving yesterday's ZPD into today's zone of actual development.

The range within which a learner can develop further the difference between what learners can do independently and what they can achieve with guidance from a more knowledgeable person. It represents the optimal learning space where tasks are neither too easy nor too challenging, making it crucial for teachers to design activities that stretch students' capabilities just beyond their current capacity. Understanding ZPD helps educators provide the right level of support to promote cognitive growth and transform struggling learners into confident achievers.

Teachers can identify a student's ZPD by first assessing what the student can do independently, then observing what they can accomplish with minimal guidance or support. This involves designing activities slightly beyond the student's current ability level and noting where they need assistance. The key is finding that sweet spot where students are challenged but not overwhelmed, requiring some scaffolding to succeed.

The scaffolding trap occurs when teachers accidentally provide too much support, which can actually stunt student growth rather than promote it. Teachers fall into this trap by not withdrawing help at the right moment, keeping students dependent on guidance rather than developing independence. To avoid this, educators must gradually reduce their assistance as students become more capable, timing the withdrawal of support precisely to encourage autonomous learning.

Teachers can strategically pair students based on their ZPD levels, allowing more knowledgeable peers to act as skilled partners for those who need support. This peer power approach can create learning breakthroughs that teacher instruction alone cannot achieve, as students often relate well to explanations from classmates. The key is thoughtful pairing that ensures the more capable student can provide appropriate guidance whilst both learners benefit from the collaborative experience.

Cultural context significantly influences how students respond to ZPD approaches because learning is deeply rooted in social and cultural interactions. For English as an Additional Language (EAL) pupils, standard ZPD approaches might miss the mark if they don't consider cultural learning styles, communication patterns, and background knowledge. Teachers need to adapt their scaffolding and support strategies to be culturally responsive, ensuring that the guidance provided aligns with students' cultural contexts and experiences.

Practical ZPD activities include collaborative problem-solving tasks where students work with more capable peers, guided reading sessions where teachers provide decreasing levels of support, and modelling techniques followed by independent practise. Teachers might also use questioning strategies that prompt thinking just beyond students' current level, or create learning stations with varying difficulty levels. The key is ensuring each activity requires some guidance initially but allows students to gradually work towards independence.

Teachers should reduce scaffolding when students begin to demonstrate increased confidence and accuracy in their attempts, showing signs they can apply the skills or knowledge with minimal prompts. The timing is crucial, support should be withdrawn gradually as students show they can self-regulate and use the internalised knowledge to improve their performance. Educators need to carefully observe student behaviour and responses to determine the precise moment when less guidance will promote rather than hinder learning progress.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into the zone of proximal development: a teacher's guide and its application in educational settings.

This comprehensive literature review of online teaching during COVID-19 759 citations (Author, Year) examines how teacher education programmes adapted to remote learning practices, analysing the effectiveness of digital pedagogical approaches and identifying key challenges faced by educators transitioning to virtual classroom environments during the pandemic.

Carrillo et al. (2020)

This paper reviews how COVID-19 forced teacher education programmes to rapidly transition from face-to-face to online teaching methods. It examines the challenges and adaptations made in preparing student teachers through remote learning environments. Teachers can apply insights about scaffolding and support strategies used during this transition to better understand how to adjust their zone of proximal development approaches when working with students in different learning contexts.

An autoethnographic study exploring language transitions in science education (Author, Year) traces the process from learning biology as a student to teaching biology as an educator, examining how language use and understanding evolves throughout this professional development process.

Fernando et al. (2021)

This autoethnographic study explores one educator's process from being an English as Additional Language student to becoming a science teacher and researcher. It examines how language learning experiences shaped the author's identity and teaching practices across multiple cultural contexts. Teachers working with EAL students can gain insights into how to recognise and build upon students' diverse linguistic backgrounds when establishing appropriate zones of proximal development.

Teachers’ perceptions about their work with EAL/D students in a standards-based educational context. 5 citations

Nguyen et al. (2023)

This research investigates teachers' perspectives on working with English as Additional Language or Dialect students within Australia's standards-based education system. It explores how teachers navigate the challenges of supporting linguistically diverse learners while meeting curriculum requirements. The findings help teachers understand how to appropriately assess and scaffold learning for EAL/D students by considering their unique starting points when determining their zone of proximal development.

This editorial examining teaching EAL/D learners across subjects 2 citations (Author, Year) explores pedagogical approaches and strategies for supporting English as an Additional Language or Dialect students in mainstream curriculum areas, highlighting the importance of integrated language and content instruction.

This editorial introduces a special issue focusing on teaching English as Additional Language or Dialect learners across different subject areas in Australian schools. It brings together various perspectives on supporting EAL/D students in mainstream educational environments. Teachers can use these insights to better understand how to adapt their instructional approaches and identify appropriate zones of proximal development for linguistically diverse students across all curriculum areas.Research on preparing mainstream teachers for diverse classrooms 3 citations (Author, Year) examines the implications for Initial Teacher Education programmes in developing educators' capacity to effectively support culturally and linguistically diverse student populations in mainstream educational settings.

Smith et al. (2023)

This paper examines how Initial Teacher Education programmes can better prepare mainstream teachers to work effectively with culturally and linguistically diverse students. It addresses the gap between teacher preparation and the reality of supporting EAL/D learners without specialised language support. The research provides valuable guidance for teachers on recognising and responding to the diverse learning needs and starting points of EAL/D students when establishing their zones of proximal development.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/the-zone-of-proximal-development-a-teachers-guide#article","headline":"The Zone of Proximal Development: A teacher's guide","description":"Discover how to use the Zone of Proximal Development to transform struggling pupils into confident learners through strategic scaffolding and peer learning.","datePublished":"2021-08-16T14:34:38.947Z","dateModified":"2026-02-12T14:50:26.524Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/the-zone-of-proximal-development-a-teachers-guide"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69690f4b6431fe651bd06965_69690f44bb3d2042283b3a0a_the-zone-of-proximal-development-a-teachers-guide-illustration.webp","wordCount":6407},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/the-zone-of-proximal-development-a-teachers-guide#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"The Zone of Proximal Development: A teacher's guide","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/the-zone-of-proximal-development-a-teachers-guide"}]}]}