Getting Started with Metacognition: A Beginner's Guide for Teachers

Explore metacognition and its importance in education. This guide offers strategies for teachers to cultivate metacognitive skills in their classrooms.

Explore metacognition and its importance in education. This guide offers strategies for teachers to cultivate metacognitive skills in their classrooms.

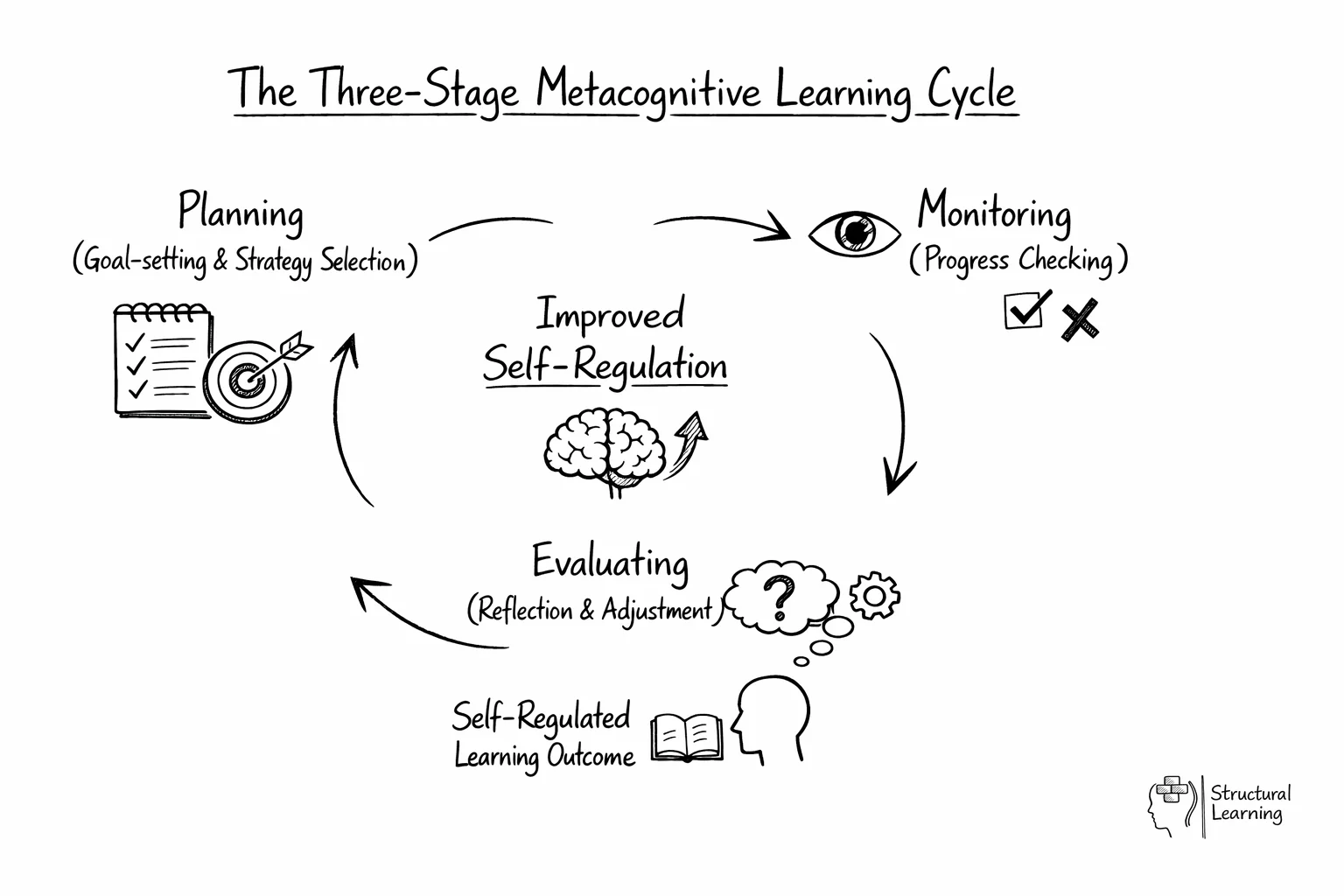

| Metacognitive Phase | Key Questions | Student Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Planning | What do I need to do? What do I already know? | Set goals, activate prior knowledge, choose strategies |

| Monitoring | Is this working? Do I understand? | Check comprehension, adjust strategies, identify difficulties |

| Evaluating | Did I achieve my goal? What worked well? | Review outcomes, reflect on strategies, plan improvements |

Metacognitionis simply thinking about your own thinking, it's when students become aware of how they learn and what strategies work for them. Students with metacognitive skills can identify when they're struggling and know specific strategies to help themselves improve. Research shows this awareness can lead to up to one full GCSE grade improvement in student performance.

Metacognition can sound like complex educational jargon, but the concept is straightforward: it means thinking about your own thinking. When students develop metacognitive (AI tools that support metacognitive development) skills, they become more aware of how they learn, can identify when they are struggling, and know strategies to help themselves. This guide introduces metacognition in accessible terms and provides simple starting points for any classroom. For those ready to implement these concepts, getting started with metacognitive teaching requires understanding these foundational principles.

Reflection is a key component of metacognition. When students engage in reflective practices, they enhance their cognitive processes and deepen their understanding of the material. Teachers who integrate reflection into their instructional strategies can creates a more insightful and purposeful learning experience for their students. This approach not only aids instruction but also encourages students to take ownership of their learning journey.

Strategic planning for student success involves using metacognitive strategies to guide instruction and support students in developing their self-regulation skills. Goal-oriented learning and teaching can transform the educational experience, making it more engaging and effective. Educational researchers have shown that students who are aware of their cognitive processes and actively reflect on their learning are more likely to achieve academic success.

metacognition is a powerful tool in education that benefits teachers, school leaders, and students alike. By developing awareness, reflection, and self-regulation, educators can create a supportive learning environment that promotes continuous improvement and academic excellence. Understanding metacognition and its applications can significantly enhance teaching practices and lead to better learning outcomes for students.

Metacognition is the awareness and understanding of your own thought processes, while self-regulated learning is the ability to control and direct your learning behaviours. Metacognition provides the knowledge about how you learn, and self-regulation uses that knowledge to actively manage learning through goal-setting and strategy adjustment. Understanding this distinction is crucial because confusing the two can undermine teaching effectiveness.

Self-regulation and metacognition are often used interchangeably but understand the difference between them.

Self-regulation refers to the ability to control thoughts, behaviours, and feelings when working towards a learning goal.

Metacognition plays a critical role in determining whether someone can become a self-regulated learner; accurately plan, monitor, and evaluate our own learning if we want to regulate our behaviours appropriately to achieve our goals.

The other key strategies that contribute to self-regulation are:

Self-regulated learners will have the pedagogical knowledge and self-awareness to develop good study habits. When completing assignments, it is likely that they will identify similar tasks that they have completed in the past, adopt the techniques that were successful for those tasks, and meet self-imposed deadlines.

The most effective metacognitive strategies follow a three-stage framework: planning (setting goals and choosing strategies), monitoring (checking progress during learning), and evaluating (reflecting on what worked and what didn't). Students learn to ask themselves questions like 'Do I understand this?' and 'What should I do differently next time?' These strategies transform struggling students into self-regulated learners who know when and how to seek help.

Each of the metacognitive processes (planning, monitoring, and evaluating) is associated with a different set of metacognitive strategies.

In the planning stage, metacognitive learners will set themselves goals before completing the learning task, identify priorities and organise their resources.

They will use the metacognitive knowledge they have developed during previous learning experiences to determine the most appropriate plan for the task they are faced with.

For example, they may have learnt that reading before class is an effective strategy for them to absorb new material during the lesson.

As the teacher is talking, they may start to form a mental model of the new topic and make associations with previous learning. In turn, this helps them to identify which techniques may be most useful to them during the lesson based on what techniques worked well when they were learning the related topics.

If the subject matter is especially challenging they are likely to employ metacognitive questioning before constructing a plan. Metacognitive learners will often ask themselves:

This type of questioning helps students to identify the priorities for the activity and plan how to use their time most effectively.

When completing extended writing tasks, metacognitive learners will set themselves deadlines for each section (e.g. Introduction, literature review, conclusion).

They will also have the self-awareness to know what time of the day they work most efficiently and utilise this knowledge to make the most effective use of their time.

For memory tasks, metacognitive learners will draw upon their knowledge of cognitive processes and are more likely to use retrieval practice techniques than rereading or highlighting when learning new vocabulary.

While students are completing a learning task they will continually monitor their performance with the intention of adapting their approach if they are not on track to achieve their learning goals. They will use the following metacognitive strategies to monitor their performance:

In response to the ongoing monitoring, students are likely to revisit and modify their plan quite regularly. They may decide to change the cognitive processes they are using or adjust the time limit assigned to each stage of their plan.

If they were working independently, they may realise that they need a period of explicit instructionfrom their teacher before they can move forward in their learning. When students have the metacognitive knowledge to identify when they need additional help, they will feel helped in their learning even when they are finding it difficult.

Once a learning task, assignment or assessment is complete, metacognitive learners will reflect on their performance.

Most importantly, they will reflect on the mental processes and study strategies they used as well as what the overall outcome was.

As part of this reflection, they will make a plan for how they will approach similar tasks in the future and may choose to write this down in a learning journal to provide quick access to their new plan when they need it.

Students will add to their metacognitive knowledge by identifying the strengths and weaknesses to the approach they used and consider whether these would apply to different learning contexts.

For example, they will want to determine whether the same strategy would have the same strengths with different subject matter.

Research consistently shows that metacognitive strategies can improve student achievement by up to one full GCSE grade level. Studies demonstrate that students who develop metacognitive awareness become more effective learners across all subject areas. The evidence is so strong that metacognition is now recognised as one of the most cost-effective educational interventions available to schools.

The study strategies of metacognitive learners have been shown to significantly increase academic achievement by as much as one full GCSE grade (Hattie, 2016).

Veenman and Beishuizen (2004) reported that metacognitive regulation, having the self-control to carry out metacognitive processes, accounts for 17% of students' cognitive achievement. This is significantly higher than the 10% that is attributed to students' innate cognitive ability.

Daniel et al. (2016) also advocates the use of metacognitive strategies to improve attainment; they concluded that the skills of planning, monitoring, and evaluating play a critical role in determining academic performance and the ability to become successful lifelong learners.

Bond and Ellis (2013) showed that student learningsignificantly improves when teachers respond to the metacognitive knowledge generated by students during the evaluation phase of learning. Students were provided with the following metacognitive prompts at the end of each lesson:

Compared to a control group who were given a lesson summary in place of the metacognitive prompts, the experimental group performed significantly higher on the two subsequent assessments that tested the knowledge learnt during the experiment.

The importance of teacher feedback to enhance the attainment of metacognitive learners has also been shown by Guo and Wei (2019). They found that students' metacognitive processes increased when teachers provided regular verification feedback (telling students if their answers were right or wrong), scaffolding (breaking complex tasks into small and manageable steps), and praise.

It has been necessary to develop reliable measures of metacognition to support researchers like those described above.

Pintrich and De Groot (1990) designed the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) which is still widely used today to measure students' metacognitive abilities.

Jackson (2018) recently reviewed the validity of the questionnaire and concluded that it still provides an accurate measurement of students' metacognitive awareness. The questionnaire consists of 55 statements which students indicate their agreement to using a Likert scale, including:

Students who develop metacognitive practices experience improved learning and problem-solving abilities and greater academic achievement.

They are better at making decisions, managing stress during learning, and using their time effectively. These skills persist outside of their educational settings and support the students to become lifelong learners.

Metacognition helps students to articulate their learning needs and actively participate in their education. When students understand how they learn best, they can communicate more effectively with teachers about what support they need. This leads to increased engagement because students feel heard and take ownership of their learning journey.

Student voice refers to any opportunity that students are given to express their opinions. This could be done formally through a school council, focus group, plenary activity or questionnaire, or informally by giving feedback to teachers during a lesson or at the end of a series of lessons.

Metacognitive learners find it easier to engage with student voice initiatives because they are familiar with the reflective thinking required to give constructive feedback about the learning task and the impact it has had on their cognitive achievement.

Students are often able to provide valuable insights to teachers about student learning, which allows teachers to adapt their teaching to best meet the needs of their students.

Conversely, by encouraging students to engage with student voice opportunities, teachers can support students to develop their metacognitive thinking and range of metacognitive activities.

Asking students to reflect on a lesson, describe their mental model of how a new topic fits in with previous learning, or which activities had the greatest impact on their understanding provides teachers with useful feedback and also increases students' metacognitive awareness.

Teachers can develop metacognitive skills by regularly reflecting on their instructional practices and asking 'What worked well and why?' School leaders can create environments that support continuous improvement by encouraging reflective practices during professional development sessions. When teachers model metacognitive thinking, they become more effective at teaching these skills to their students.

Bond and Ellis showed that students' metacognitive approaches can be used to influence teachers' practice, while Guo and Wei showed how teachers' feedback can encourage student metacognition and enhance the learning process.

These research findings, along with many others, highlight the importance of including the role of metacognition in teachers' professional development programmes.

for teachers to be educated about metacognition, including what it is and how to support students to develop the skills of planning, monitoring and evaluating their own learning.

The nature of these skills is determined by the subject matter and learning context, which means that subject specialists are best suited to teach students the cognitive tasks associated with their subject.

Research has shown that when teachers develop and use metacognitive skills in their teaching, their students' academic achievement improves.

This is partly because teachers begin modelling metacognitive strategies to their students, but also because they become more reflective about their own practice and more confident adapting their teaching during a lesson as they monitor its effectiveness.

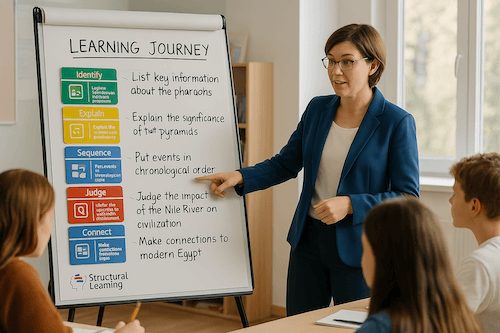

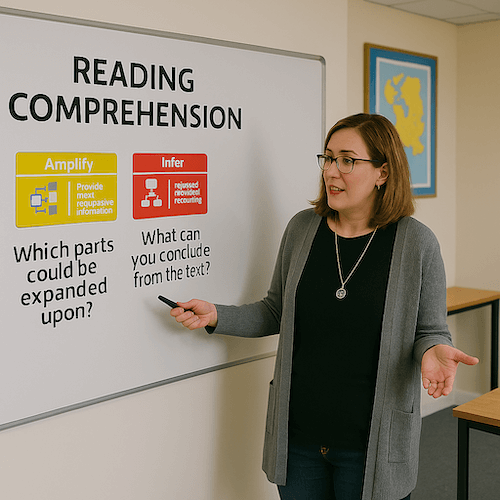

Teachers should start by modeling metacognitive thinking out loud, showing studentshow to plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning. Integrate regular reflection activities into lessons where students assess their understanding and identify next steps. The key is consistent practice with feedback, gradually releasing responsibility so students internalize these thinking processes.

As mentioned above, metacognition can be taught implicitly during lessons by teachers modelling planning, monitoring and evaluating as part of the teaching process. The simplest way to do this is for teachers to verbalise their thought process to the class:

Alternatively, metacognitive thinking can be taught explicitly by subject specialists. In this case, teachers would introduce the concept of metacognition to their students and explain how each of the three strategies can be applied to their subject.

The learning context is very important; planning an essay in English will require very different skills to planning the answer to exam question in Mathematics.

To complement the explicit teaching of metacognitive activities, students may be encouraged to keep a learning journal, complete an exam wrapper, or use metacognitive prompts at key points during a lesson.

A document for students to record their thoughts and reflections following a lesson or series of lessons.

It is normally used to reflect on the process of learning rather than specific learning outcomes, but it may be useful to highlight links between topics or to draw parallels between the current tasks and ones they have completed before.

Students should also identify their strengths and weaknesses and what they would do the same or differently for a similar task in the future.

A set of questions that can be completed before and after an assessment to reflect on the revision strategies (before) and the outcome of the assessment (after).

The purpose of an exam wrapper is to help students identify which revision techniques were most helpful to them and whether their exam technique was effective.

If a student struggled with time-management during the exam, they would record this on the wrapper and formulate a plan to help manage their time better in future assessments.

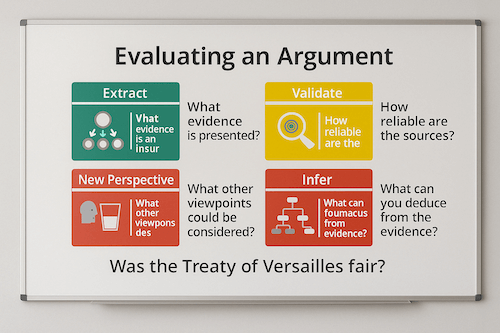

These are questions or question starters that are designed to help students improve their metacognitive awareness. The purpose of the prompts is to teach students to spontaneously question themselves before, during, and after completing a learning task. The following examples can be applied to most lesson and learning contexts.

How much time should I spend on this task?

How can I ensure that I stay on track?

Have I completed a task like this before?

What do I know that will help me do this task?

2. Monitoring:

Am I on track to complete the task on time?

Have I understood what is required? How can I be sure?

Is there a more effective way for me to complete this task?

3. Evaluating:

Did I achieve what I wanted to achieve?

What approach will I take if I need to do a similar task in the future?

What do I want to learn more about?

Teachers can find evidence-based resources through educational organisations like the Education Endowment Foundation, which provides practical guidance on metacognitive strategies. Academic journals and professional development courses offer deeper insights into implementing metacognitive approaches effectively. Many schools also share successful case studies and practical examples through educational networks and online communities.

Here are five studies on metacognition and their implications, accompanied by a 50-word summary for each. Whilst this is not an extensive list, these studies should be useful for teachers who are doing research in the area of metacognition.

1. Perry, J., Lundie, D., & Golder, G. (2018). Metacognition in schools: what does the literature suggest about the effectiveness of teaching metacognition in schools? Educational Review, 71, 483-500.

Summary: The study provides strong evidence that effective teaching of metacognition in schools has a positive impact on student outcomes, including academic performance and well-being.

2. Kuhn, D., & Dean, Jr., D. (2004). Metacognition: A Bridge Between Cognitive Psychology and Educational Practice. Theory Into Practice, 43, 268-273.

Summary: This study proposes that metacognition serves as a bridge between cognitive psychology and educational practice, particularly in the development of skilled thinking.

3. Gunstone, R., & Northfield, J. (1994). Metacognition and learning to teach. International Journal of Science Education, 16, 523-537.

Summary: The authors argue for an approach where developing greater metacognition is central to changes appropriate for teacher development.

4. Wall, K., & Hall, E. (2016). Teachers as metacognitive role models. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39, 403-418.

Summary: The study shows a catalytic relationship between the pedagogies used by teachers to develop their students’ metacognition and the teachers’ own learning and metacognitive knowledge.

5. Lippmann Kung, R., & Linder, C. (2007). Metacognitive activityin the physics student laboratory: is increased metacognition necessarily better? Metacognition and Learning, 2, 41-56.

Metacognition is simply thinking about your own thinking, where students become aware of how they learn and what strategies work for them. Research shows that students with metacognitive skills can achieve up to one full GCSE grade improvement in performance, making it one of the most powerful tools for educational success.

Metacognition is the awareness and understanding of your own thought processes, while self-regulated learning is the ability to control and direct your learning behaviours. Metacognition provides the knowledge about how you learn, and self-regulation uses that knowledge to actively manage learning through goal-setting and strategy adjustment.

Teachers can begin by introducing the three-stage framework of planning, monitoring, and evaluating to their students. Start by teaching students to ask themselves questions like 'Do I understand this?' during lessons and 'What should I do differently next time?' after completing tasks.

The most effective strategies follow the planning-monitoring-evaluating cycle, where students set goals and choose strategies, check their progress during learning, and reflect on what worked. This includes metacognitive questioning such as 'What do I already know about this topic?' and 'What has worked well for me in the past?'

Metacognitive skills transform struggling students into self-regulated learners who can identify when they're having difficulties and know specific strategies to help themselves improve. Students with these skills feel helped even when struggling because they know exactly when and how to seek help.

Reflection is a key component of metacognition that enhances students' cognitive processes and deepens their understanding of material. When teachers integrate reflective practices into their instructional strategies, they creates a more insightful and purposeful learning experience that encourages students to take ownership of their learning journey.

Understanding this distinction is crucial because confusing the two can undermine teaching effectiveness. While metacognition provides the self-awareness needed for learning, self-regulation also requires cognitive strategies like retrieval practice and social-emotional strategies such as motivation control and knowing when to seek help.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into getting started with metacognition: a beginner's guide for teachers and its application in educational settings.

8 Pillars X 8 Layers Model of Metacognition: Educational Strategies, Exercises &Trainings 106 citations

Drigas et al. (2021)

This paper presents a comprehensive framework called the '8 Pillars X 8 Layers Model' that breaks down metacognition into specific components and provides concrete educational strategies and training exercises for developing metacognitive skills. The model offers teachers a structured approach to understanding the multifaceted nature of metacognition and practical methods to cultivate these skills in their students. This framework is particularly valuable for beginner teachers as it provides a clear roadmap for implementing metacognitive strategies in the classroom.

Beliefs about the self-regulation of learning predict cognitive and metacognitive strategies and academic performance in pre-service teachers 61 citations

Vosniadou et al. (2021)

This research examines how pre-service teachers' beliefs about their ability to regulate their own learning influence their use of cognitive and metacognitive strategies, as well as their academic performance. The study provides insights into the connection between teachers' self-regulation beliefs and their actual strategic learning behaviours. For teachers beginning to explore metacognition, this paper highlights the importance of developing their own metacognitive awareness before they can effectively teach these skills to students.

Relationship between technology acceptance model, self-regulation strategies, and academic self-efficacy with academic performance and perceived learning among college students during remote education 23 citations

Navarro et al. (2023)

This study investigates how college students' acceptance of technology, self-regulation strategies, and academic self-efficacy relate to their academic performance during remote learning. While focused on higher education and remote learning contexts, the research provides insights into how self-regulation and metacognitive strategies impact student success in technology-enhanced environments. Teachers interested in metacognition can benefit from understanding how these skills translate across different learning modalities and age groups.

Metacognition: An Overview. 663 citations

Livingston et al. (2003)

This foundational paper provides a comprehensive overview of metacognition, covering its definition, components, and importance in learning. Livingston breaks down the concept into accessible terms and explains how metacognitive awareness and regulation contribute to student success. As an introductory resource with extensive citations, this paper serves as an essential starting point for teachers who want to understand the theoretical foundations of metacognition before implementing it in their classrooms.

Scott et al. (2021)

This paper focuses on climate change adaptation planning by local governments in Australia, examining how they monitor and evaluate their adaptation efforts. This research is not directly relevant to teachers learning about metacognition, as it deals with environmental policy and government planning rather than educational psychology or classroom instruction. Teachers seeking information about metacognitive strategies would find limited value in this climate change adaptation study.