Embodied Cognition: Thinking with the Body

Explore how embodied cognition enhances learning through physical interaction, multisensory experiences, and hands-on activities in the classroom.

Have you ever considered how your physical experiences influence your thoughts and decisions? This question leads us into the fascinating domain of embodied cognition, a field that explores the interconnectedness of mind and body. Understanding this relationship can reshape how we view cognitive processes and even our interactions with the environment.

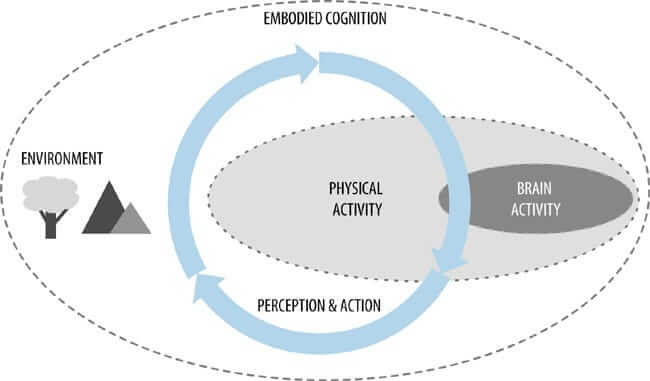

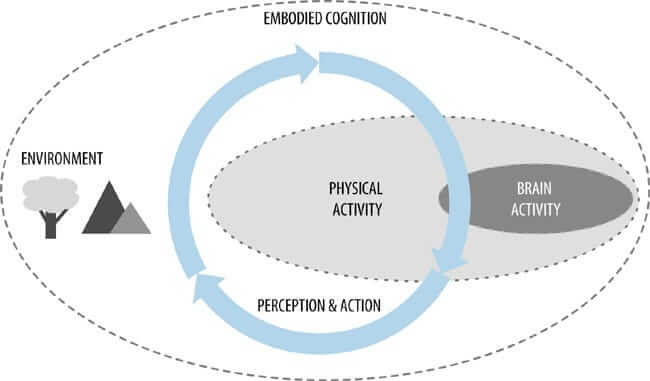

Embodied cognition proposes that our mental activities are deeply rooted in our bodily experiences. Key concepts such as ecological psychology, connectionism, and phenomenology provide a framework for exploring how cognition is not just an isolated mental activity but is closely linked to physicality. Additionally, various models of embodied cognition, including embedded, extended, and enactive cognition, offer insights into how our actions and surroundings shape our understanding of the world.

into the intricate relationship between the mind and body, examine practical applications in areas such as education and robotics, and address philosophical questions that arise within this field. By exploring current research and trends, we will uncover how embodied cognition can provide a more comprehensive understanding of human behaviour and thought processes.

Embodied cognition includes ecological psychology (how environment shapesthinking), connectionism (neural networks and physical experience), and phenomenology (lived bodily experience). These concepts explain how physical experiences like movement, sensory input, and environmental interaction directly influence cognitive processes. The theory challenges traditional views that separate mind from body in understanding human thought.

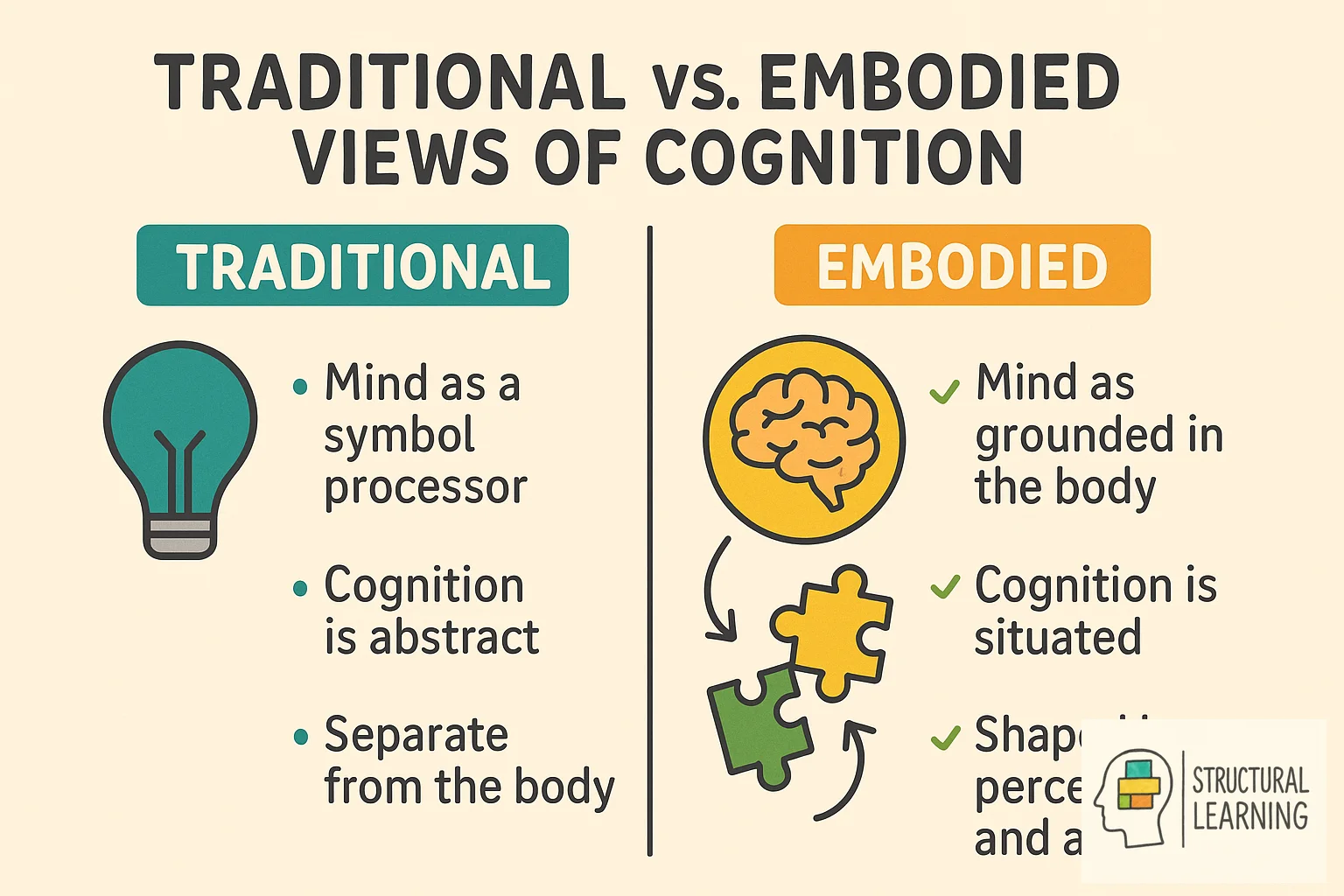

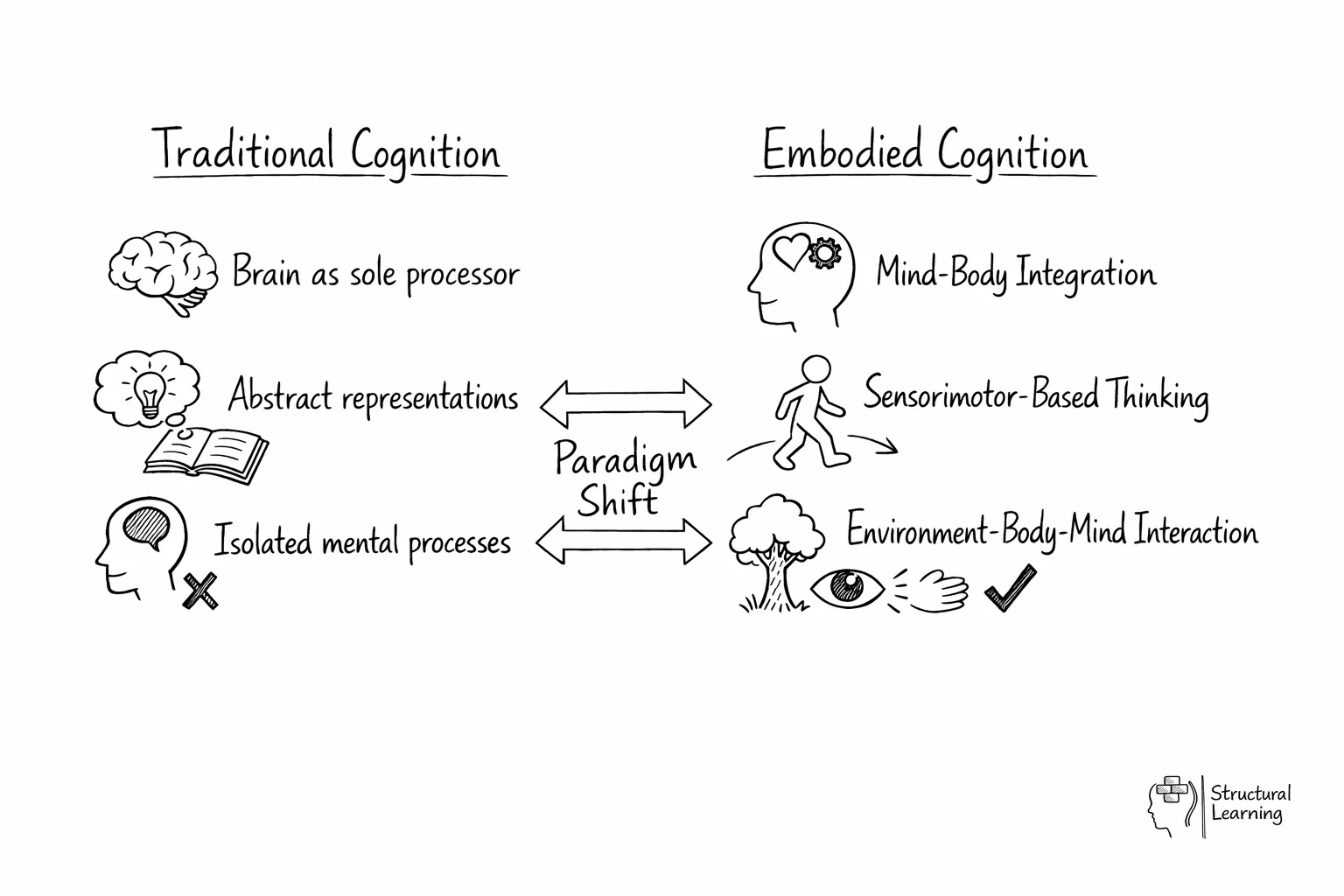

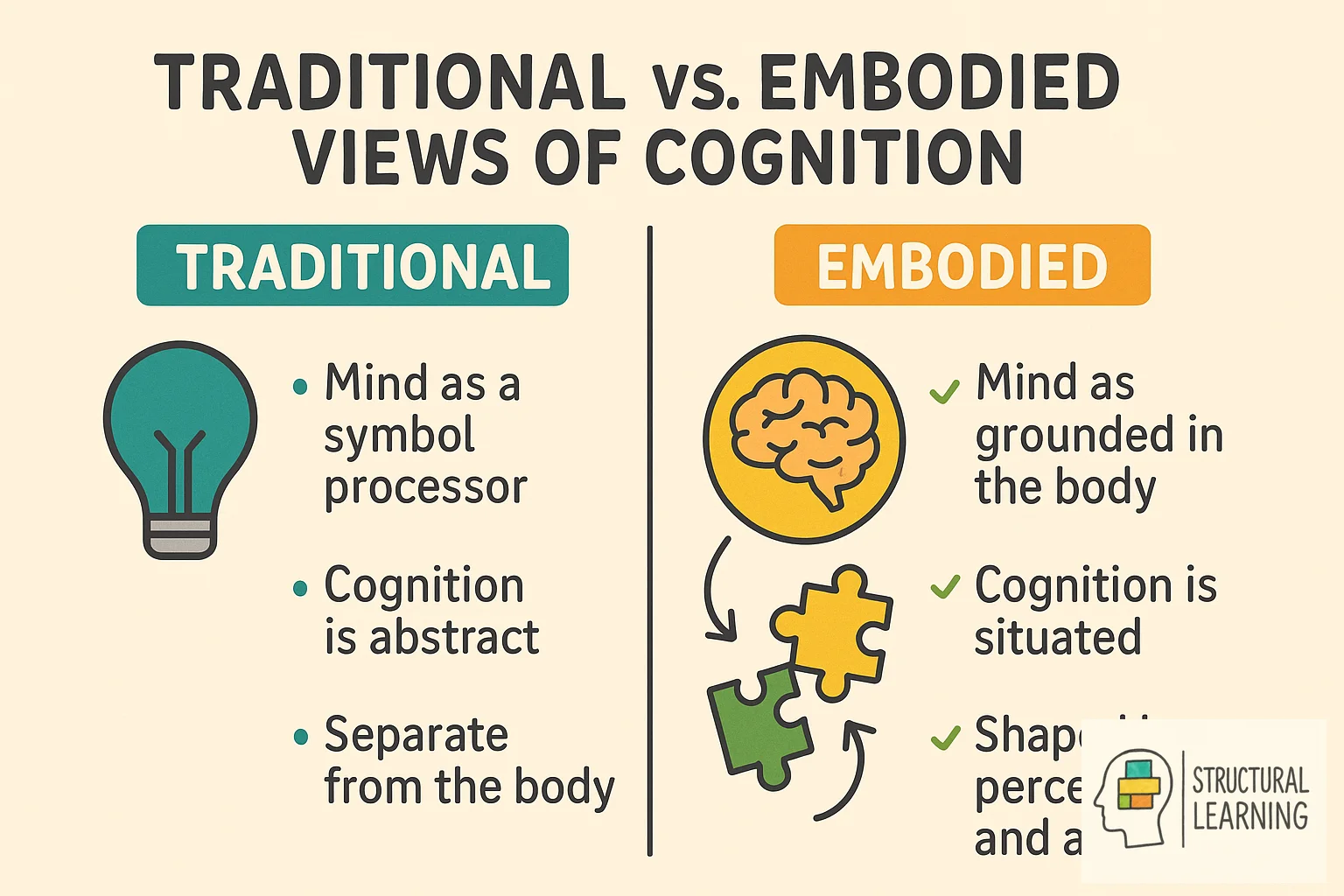

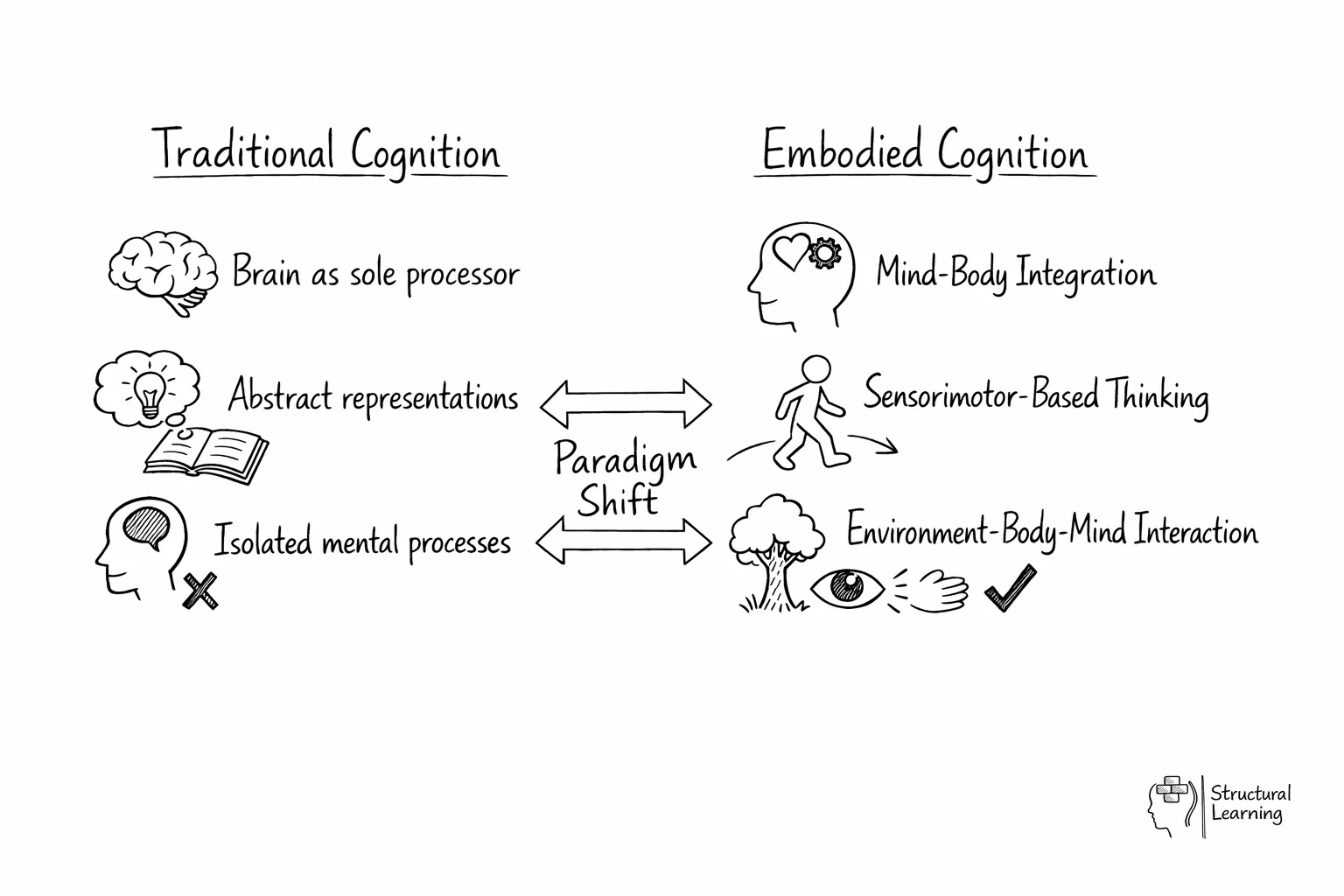

Embodied cognition is a concept in cognitive science suggesting our cognitive processes are deeply rooted in the body's interactions with the environment. Traditional views of human cognition often depict mental faculties as computations performed by a brain in isolation from bodily experiences. However, the embodied cognition hypothesis challenges this notion. It proposes that cognitive functions cannot be entirely separated from physical embodiment and that our sensorimotor systems play a constitutive role in shaping the mind.

According to embodied cognition, the brain is not the sole contributor to cognitive abilities. Instead, cognition emerges from the interplay between an organism's perceptual experiences and its bodily actions. This means that physical actions are not simply outputs of cognitive processes but are fundamentally intertwined with our mental faculties.

Cognitive representations, as embodied cognition theorists argue, are not abstract but rather are tied to sensorimotor systems. This denotes that humans think and perceive through modality-specific systems utilising perceptual symbols that arise from sensorimotor experiences. Our ability to reason, remember, and imagine stems from, and is limited by, our physical form and capabilities. Therefore, cognitive science must consider not only the brain but also the body and environment to fully comprehend the nature of thought and intelligence.

Ecological psychology, devised by James Gibson, views perception as a direct interaction with the environment. Affordances, which are opportunities for action that objects or environments provide, enable this interaction. For instance, a chair affords sitting, and a staircase affords climbing. These affordances are perceived directly, without the need for complex cognitive representations.

In ecological psychology, rather than cognition solely occurring as internal mental processes, thinking largely happens through implicit actions, sometimes without conscious deliberation. This perspective underlines that cognition is better understood through the lens of how organisms operate within their specific ecological niches.

Moreover, evidence suggests that sensory and motor systems influence cognitive load and memory formation. This creates opportunities for educators to develop scaffolding strategies that support learners, particularly those with special educational needs. Understanding how physical movement enhances engagement can transform classroom practices and promote more inclusive learning environments. Additionally, embodied approaches can strengthen critical thinking skills through hands-on exploration and help students develop better self-regulation. These methods can be integrated across the curriculum to support comprehension, including reading comprehension through gesture and movement.In ecological psychology, rather than cognition solely occurring as internal mental processes, thinking largely happens through implicit actions, sometimes without conscious deliberation. This perspective underlines that cognition is better understood through the lens of how organisms operate within their specific ecological niches.

Moreover, evidence suggests that sensory and motor systems influence cognitive load and memory formation. This creates opportunities for educators to develop scaffolding strategies that support learners, particularly those with special educational needs. Understanding how physical movement enhances engagement can transform classroom practices and promote more inclusive learning environments. Additionally, embodied approaches can strengthen critical thinking skills through hands-on exploration and help students develop better self-regulation. These methods can be integrated across the curriculum to support comprehension, including reading comprehension through gesture and movement.

Embodied cognition has broad applications, notably in education and robotics. In education, it prompts a shift from passive learning to active, physically engaged learning. In robotics, it inspires the creation of robots that learn and adapt through physical interaction.

Traditional educational methods often rely on abstract, disembodied instruction, but embodied learning emphasises the importance of physical activity and sensory experiences. Strategies such as movement-based lessons, hands-on activities, and role-playing exercises enhance student engagement and understanding. This approach is particularly beneficial for students who struggle with traditional teaching methods, including those with learning disabilities or sensory processing issues.

Incorporating embodied learning can transform classroom management by redirecting students' energy into constructive actions. By allowing students to move and interact physically with learning materials, educators can cultivate a more dynamic and inclusive learning environment.

The integration of embodied cognition extends powerfully into science education, where abstract concepts become accessible through physical demonstration. Students exploring molecular behaviour can move their bodies to simulate particle motion in different states of matter, whilst those studying wave properties benefit from creating waves with rope or their arms. Research demonstrates that learners who physically model scientific processes show significantly improved conceptual understanding compared to those receiving traditional instruction alone.

Literature and humanities subjects equally benefit from embodied approaches to learning. Students analysing dramatic texts gain deeper comprehension through physical interpretation of characters' emotions and motivations. Historical events become more memorable when learners recreate key moments or walk through timeline activities. Educational practice shows that incorporating movement into essay planning, such as physically organising ideas around the classroom, enhances students' ability to structure arguments coherently.

Implementation of embodied cognition requires minimal resources but maximum creativity. Teachers can transform learning environments by encouraging gesture use during explanations, incorporating brief movement breaks between cognitive tasks, and designing activities where students manipulate physical objects to represent abstract ideas. These strategies prove particularly effective for kinesthetic learners whilst benefiting all students through multi-sensory engagement.

The scientific foundations of embodied cognition emerged from groundbreaking studies in the 1980s and 1990s that challenged traditional cognitive science. Lakoff and Johnson's seminal work on conceptual metaphors revealed how physical experiences shape abstract thinking, while neuroscientist Antonio Damasio's research demonstrated the inseparable connection between emotion, body, and rational thought. These findings fundamentally shifted our understanding of how learning occurs, moving beyond the mind as a computer metaphor to recognise cognition as a whole-body phenomenon.

Recent educational research has validated these principles in classroom settings. Studies by Susan Goldin-Meadow show that children who use gestures while learning mathematical concepts demonstrate significantly better retention and transfer than those who remain physically static. Similarly, research in embodied mathematics education reveals that pupils who physically manipulate objects or use bodily movements to represent numerical relationships develop stronger conceptual understanding than those relying solely on abstract symbols.

For educators, this research translates into immediate classroom applications. Simple strategies such as encouraging gesture during explanation, incorporating movement-based learning activities, and creating opportunities for physical manipulation of concepts can enhance student engagement and comprehension. The evidence consistently demonstrates that when we honour the body's role in thinking, we create more effective and inclusive learning environments.

Successful implementation of embodied cognition principles requires deliberate integration of physical movement into existing curriculum structures rather than treating it as an additional burden. Research demonstrates that even brief movement breaks, strategically positioned between cognitive tasks, can significantly enhance subsequent learning outcomes. Teachers should begin by identifying natural connection points where physical experience can reinforce abstract concepts, such as using hand gestures to represent mathematical operations or encouraging students to physically model scientific processes.

The key lies in creating purposeful movement that directly supports learning objectives rather than arbitrary physical activity. For instance, when teaching fractions, students might physically divide into groups to represent denominators, or use their bodies to form geometric shapes during mathematics lessons. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that such embodied approaches can actually reduce mental effort b y providing additional processing channels, making complex concepts more accessible to diverse learners.

Practical implementation begins with small, manageable changes to established routines. Teachers can incorporate simple gestures during vocabulary instruction, encourage students to trace letters in the air whilst learning spelling patterns, or use classroom space for timeline activities in history lessons. These strategies require minimal preparation whilst maximising the natural learning benefits that emerge when mind and body work in harmony.

Mathematics education benefits profoundly from embodied approaches that transform abstract concepts into physical experiences. Research demonstrates that students who use their bodies to explore geometric relationships, such as walking around shapes or using hand gestures to represent mathematical operations, show significantly improved understanding and retention. Number lines become walking paths, fractions transform into pizza slices students can physically manipulate, and algebraic equations come alive through balance activities where students literally embody mathematical equilibrium.

Language arts instruction gains particular power when students physically experience narrative elements and linguistic structures. Drama-based activities allow learners to inhabit characters and explore plot developments through movement, whilst phonics instruction becomes more effective when children associate sounds with specific gestures or movements. Writing workshops that incorporate physical planning activities, such as story mapping through classroom movement or using body positions to understand sentence structure, create stronger neural pathways between physical experience and linguistic comprehension.

Science education naturally aligns with embodied cognition principles, as students can model molecular behaviour through dance, simulate gravitational forces through playground activities, and explore ecosystems by physically representing different organisms and their interactions. Teachers can implement these approaches immediately by replacing traditional demonstrations with student-centred physical explorations, ensuring that complex scientific concepts become memorable through lived experience rather than passive observation.

Research demonstrates that embodied cognition strategies must be carefully calibrated to match learners' developmental stages, as children's capacity for abstract thinking and motor coordination evolves significantly from early years through secondary education. Young children naturally learn through their bodies, making embodied approaches particularly powerful in primary settings where concrete manipulation of objects supports mathematical concepts and gross motor movements reinforce literacy skills. However, Piaget's developmental theory reminds us that younger learners require more direct physical engagement, whilst older students can benefit from subtler embodied techniques that complement their growing abstract reasoning abilities.

In early years and primary settings, embodied learning should emphasise full-body engagement through activities like hopscotch for number sequences or acting out story elements. Secondary educators can adapt these principles by incorporating gesture-based learning, where students use hand movements to represent mathematical functions or historical timelines. Jean Piaget's work on cognitive development suggests that even adolescents benefit from physical representation of abstract concepts, though the approach becomes more sophisticated and less overtly physical.

Practical implementation requires teachers to assess their students' developmental readiness and adjust embodied strategies accordingly. Primary teachers might use floor mats for fraction work, whilst secondary colleagues could employ standing discussions or kinesthetic problem-solving activities that honour students' need for movement without appearing childish.

Embodied cognition offers a powerful lens through which to understand the interconnectedness of mind, body, and environment. Its principles challenge traditional views of cognition as solely brain-based, highlighting the crucial role of physical experiences in shaping our thoughts and actions.

By embracing embodied approaches in education and technology, we can create more effective learning environments and develop more adaptable and intelligent systems. Further research in this field promises to deepen our understanding of human cognition and enable new possibilities for enhancing learning and interaction.

For educators ready to embrace this approach, begin by auditing existing lessons to identify opportunities for physical engagement. Mathematics concepts can be explored through spatial reasoning activities, whilst literacy skills develop through dramatic interpretation and storytelling with movement. Science investigations naturally lend themselves to hands-on experimentation, and even abstract subjects benefit when students can manipulate materials or use gesture to represent complex ideas.

Professional development in embodied learning principles should focus on practical implementation strategies rather than theoretical frameworks alone. Research demonstrates that when teachers experience embodied learning themselves, they become more confident advocates for its classroom application. Collaboration with colleagues allows for shared resources and peer observation, creating supportive networks that sustain long-term change in educational practice.

The transformation toward embodied cognition in education is not merely pedagogical innovation but an essential evolution responding to our deeper understanding of how humans learn. As we continue to recognise the artificial separation between mind and body in traditional education, embracing physical experience as integral to learning becomes both an evidence-based imperative and a pathway to more engaging, effective, and equitable educational outcomes for all learners.

Have you ever considered how your physical experiences influence your thoughts and decisions? This question leads us into the fascinating domain of embodied cognition, a field that explores the interconnectedness of mind and body. Understanding this relationship can reshape how we view cognitive processes and even our interactions with the environment.

Embodied cognition proposes that our mental activities are deeply rooted in our bodily experiences. Key concepts such as ecological psychology, connectionism, and phenomenology provide a framework for exploring how cognition is not just an isolated mental activity but is closely linked to physicality. Additionally, various models of embodied cognition, including embedded, extended, and enactive cognition, offer insights into how our actions and surroundings shape our understanding of the world.

into the intricate relationship between the mind and body, examine practical applications in areas such as education and robotics, and address philosophical questions that arise within this field. By exploring current research and trends, we will uncover how embodied cognition can provide a more comprehensive understanding of human behaviour and thought processes.

Embodied cognition includes ecological psychology (how environment shapesthinking), connectionism (neural networks and physical experience), and phenomenology (lived bodily experience). These concepts explain how physical experiences like movement, sensory input, and environmental interaction directly influence cognitive processes. The theory challenges traditional views that separate mind from body in understanding human thought.

Embodied cognition is a concept in cognitive science suggesting our cognitive processes are deeply rooted in the body's interactions with the environment. Traditional views of human cognition often depict mental faculties as computations performed by a brain in isolation from bodily experiences. However, the embodied cognition hypothesis challenges this notion. It proposes that cognitive functions cannot be entirely separated from physical embodiment and that our sensorimotor systems play a constitutive role in shaping the mind.

According to embodied cognition, the brain is not the sole contributor to cognitive abilities. Instead, cognition emerges from the interplay between an organism's perceptual experiences and its bodily actions. This means that physical actions are not simply outputs of cognitive processes but are fundamentally intertwined with our mental faculties.

Cognitive representations, as embodied cognition theorists argue, are not abstract but rather are tied to sensorimotor systems. This denotes that humans think and perceive through modality-specific systems utilising perceptual symbols that arise from sensorimotor experiences. Our ability to reason, remember, and imagine stems from, and is limited by, our physical form and capabilities. Therefore, cognitive science must consider not only the brain but also the body and environment to fully comprehend the nature of thought and intelligence.

Ecological psychology, devised by James Gibson, views perception as a direct interaction with the environment. Affordances, which are opportunities for action that objects or environments provide, enable this interaction. For instance, a chair affords sitting, and a staircase affords climbing. These affordances are perceived directly, without the need for complex cognitive representations.

In ecological psychology, rather than cognition solely occurring as internal mental processes, thinking largely happens through implicit actions, sometimes without conscious deliberation. This perspective underlines that cognition is better understood through the lens of how organisms operate within their specific ecological niches.

Moreover, evidence suggests that sensory and motor systems influence cognitive load and memory formation. This creates opportunities for educators to develop scaffolding strategies that support learners, particularly those with special educational needs. Understanding how physical movement enhances engagement can transform classroom practices and promote more inclusive learning environments. Additionally, embodied approaches can strengthen critical thinking skills through hands-on exploration and help students develop better self-regulation. These methods can be integrated across the curriculum to support comprehension, including reading comprehension through gesture and movement.In ecological psychology, rather than cognition solely occurring as internal mental processes, thinking largely happens through implicit actions, sometimes without conscious deliberation. This perspective underlines that cognition is better understood through the lens of how organisms operate within their specific ecological niches.

Moreover, evidence suggests that sensory and motor systems influence cognitive load and memory formation. This creates opportunities for educators to develop scaffolding strategies that support learners, particularly those with special educational needs. Understanding how physical movement enhances engagement can transform classroom practices and promote more inclusive learning environments. Additionally, embodied approaches can strengthen critical thinking skills through hands-on exploration and help students develop better self-regulation. These methods can be integrated across the curriculum to support comprehension, including reading comprehension through gesture and movement.

Embodied cognition has broad applications, notably in education and robotics. In education, it prompts a shift from passive learning to active, physically engaged learning. In robotics, it inspires the creation of robots that learn and adapt through physical interaction.

Traditional educational methods often rely on abstract, disembodied instruction, but embodied learning emphasises the importance of physical activity and sensory experiences. Strategies such as movement-based lessons, hands-on activities, and role-playing exercises enhance student engagement and understanding. This approach is particularly beneficial for students who struggle with traditional teaching methods, including those with learning disabilities or sensory processing issues.

Incorporating embodied learning can transform classroom management by redirecting students' energy into constructive actions. By allowing students to move and interact physically with learning materials, educators can cultivate a more dynamic and inclusive learning environment.

The integration of embodied cognition extends powerfully into science education, where abstract concepts become accessible through physical demonstration. Students exploring molecular behaviour can move their bodies to simulate particle motion in different states of matter, whilst those studying wave properties benefit from creating waves with rope or their arms. Research demonstrates that learners who physically model scientific processes show significantly improved conceptual understanding compared to those receiving traditional instruction alone.

Literature and humanities subjects equally benefit from embodied approaches to learning. Students analysing dramatic texts gain deeper comprehension through physical interpretation of characters' emotions and motivations. Historical events become more memorable when learners recreate key moments or walk through timeline activities. Educational practice shows that incorporating movement into essay planning, such as physically organising ideas around the classroom, enhances students' ability to structure arguments coherently.

Implementation of embodied cognition requires minimal resources but maximum creativity. Teachers can transform learning environments by encouraging gesture use during explanations, incorporating brief movement breaks between cognitive tasks, and designing activities where students manipulate physical objects to represent abstract ideas. These strategies prove particularly effective for kinesthetic learners whilst benefiting all students through multi-sensory engagement.

The scientific foundations of embodied cognition emerged from groundbreaking studies in the 1980s and 1990s that challenged traditional cognitive science. Lakoff and Johnson's seminal work on conceptual metaphors revealed how physical experiences shape abstract thinking, while neuroscientist Antonio Damasio's research demonstrated the inseparable connection between emotion, body, and rational thought. These findings fundamentally shifted our understanding of how learning occurs, moving beyond the mind as a computer metaphor to recognise cognition as a whole-body phenomenon.

Recent educational research has validated these principles in classroom settings. Studies by Susan Goldin-Meadow show that children who use gestures while learning mathematical concepts demonstrate significantly better retention and transfer than those who remain physically static. Similarly, research in embodied mathematics education reveals that pupils who physically manipulate objects or use bodily movements to represent numerical relationships develop stronger conceptual understanding than those relying solely on abstract symbols.

For educators, this research translates into immediate classroom applications. Simple strategies such as encouraging gesture during explanation, incorporating movement-based learning activities, and creating opportunities for physical manipulation of concepts can enhance student engagement and comprehension. The evidence consistently demonstrates that when we honour the body's role in thinking, we create more effective and inclusive learning environments.

Successful implementation of embodied cognition principles requires deliberate integration of physical movement into existing curriculum structures rather than treating it as an additional burden. Research demonstrates that even brief movement breaks, strategically positioned between cognitive tasks, can significantly enhance subsequent learning outcomes. Teachers should begin by identifying natural connection points where physical experience can reinforce abstract concepts, such as using hand gestures to represent mathematical operations or encouraging students to physically model scientific processes.

The key lies in creating purposeful movement that directly supports learning objectives rather than arbitrary physical activity. For instance, when teaching fractions, students might physically divide into groups to represent denominators, or use their bodies to form geometric shapes during mathematics lessons. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that such embodied approaches can actually reduce mental effort b y providing additional processing channels, making complex concepts more accessible to diverse learners.

Practical implementation begins with small, manageable changes to established routines. Teachers can incorporate simple gestures during vocabulary instruction, encourage students to trace letters in the air whilst learning spelling patterns, or use classroom space for timeline activities in history lessons. These strategies require minimal preparation whilst maximising the natural learning benefits that emerge when mind and body work in harmony.

Mathematics education benefits profoundly from embodied approaches that transform abstract concepts into physical experiences. Research demonstrates that students who use their bodies to explore geometric relationships, such as walking around shapes or using hand gestures to represent mathematical operations, show significantly improved understanding and retention. Number lines become walking paths, fractions transform into pizza slices students can physically manipulate, and algebraic equations come alive through balance activities where students literally embody mathematical equilibrium.

Language arts instruction gains particular power when students physically experience narrative elements and linguistic structures. Drama-based activities allow learners to inhabit characters and explore plot developments through movement, whilst phonics instruction becomes more effective when children associate sounds with specific gestures or movements. Writing workshops that incorporate physical planning activities, such as story mapping through classroom movement or using body positions to understand sentence structure, create stronger neural pathways between physical experience and linguistic comprehension.

Science education naturally aligns with embodied cognition principles, as students can model molecular behaviour through dance, simulate gravitational forces through playground activities, and explore ecosystems by physically representing different organisms and their interactions. Teachers can implement these approaches immediately by replacing traditional demonstrations with student-centred physical explorations, ensuring that complex scientific concepts become memorable through lived experience rather than passive observation.

Research demonstrates that embodied cognition strategies must be carefully calibrated to match learners' developmental stages, as children's capacity for abstract thinking and motor coordination evolves significantly from early years through secondary education. Young children naturally learn through their bodies, making embodied approaches particularly powerful in primary settings where concrete manipulation of objects supports mathematical concepts and gross motor movements reinforce literacy skills. However, Piaget's developmental theory reminds us that younger learners require more direct physical engagement, whilst older students can benefit from subtler embodied techniques that complement their growing abstract reasoning abilities.

In early years and primary settings, embodied learning should emphasise full-body engagement through activities like hopscotch for number sequences or acting out story elements. Secondary educators can adapt these principles by incorporating gesture-based learning, where students use hand movements to represent mathematical functions or historical timelines. Jean Piaget's work on cognitive development suggests that even adolescents benefit from physical representation of abstract concepts, though the approach becomes more sophisticated and less overtly physical.

Practical implementation requires teachers to assess their students' developmental readiness and adjust embodied strategies accordingly. Primary teachers might use floor mats for fraction work, whilst secondary colleagues could employ standing discussions or kinesthetic problem-solving activities that honour students' need for movement without appearing childish.

Embodied cognition offers a powerful lens through which to understand the interconnectedness of mind, body, and environment. Its principles challenge traditional views of cognition as solely brain-based, highlighting the crucial role of physical experiences in shaping our thoughts and actions.

By embracing embodied approaches in education and technology, we can create more effective learning environments and develop more adaptable and intelligent systems. Further research in this field promises to deepen our understanding of human cognition and enable new possibilities for enhancing learning and interaction.

For educators ready to embrace this approach, begin by auditing existing lessons to identify opportunities for physical engagement. Mathematics concepts can be explored through spatial reasoning activities, whilst literacy skills develop through dramatic interpretation and storytelling with movement. Science investigations naturally lend themselves to hands-on experimentation, and even abstract subjects benefit when students can manipulate materials or use gesture to represent complex ideas.

Professional development in embodied learning principles should focus on practical implementation strategies rather than theoretical frameworks alone. Research demonstrates that when teachers experience embodied learning themselves, they become more confident advocates for its classroom application. Collaboration with colleagues allows for shared resources and peer observation, creating supportive networks that sustain long-term change in educational practice.

The transformation toward embodied cognition in education is not merely pedagogical innovation but an essential evolution responding to our deeper understanding of how humans learn. As we continue to recognise the artificial separation between mind and body in traditional education, embracing physical experience as integral to learning becomes both an evidence-based imperative and a pathway to more engaging, effective, and equitable educational outcomes for all learners.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/embodied-cognition#article","headline":"Embodied Cognition: Thinking with the Body","description":"Explore how embodied cognition enhances learning through physical interaction, multisensory experiences, and hands-on activities in the classroom.","datePublished":"2024-09-27T15:59:52.975Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/embodied-cognition"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/695027329393e1d5d648301c_9lfzw3.webp","wordCount":5279},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/embodied-cognition#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Embodied Cognition: Thinking with the Body","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/embodied-cognition"}]}]}