Attribution Theory

Explore attribution theory and how it shapes motivation, behaviour and relationships. Learn how attributions impact communication and personal growth.

Explore attribution theory and how it shapes motivation, behaviour and relationships. Learn how attributions impact communication and personal growth.

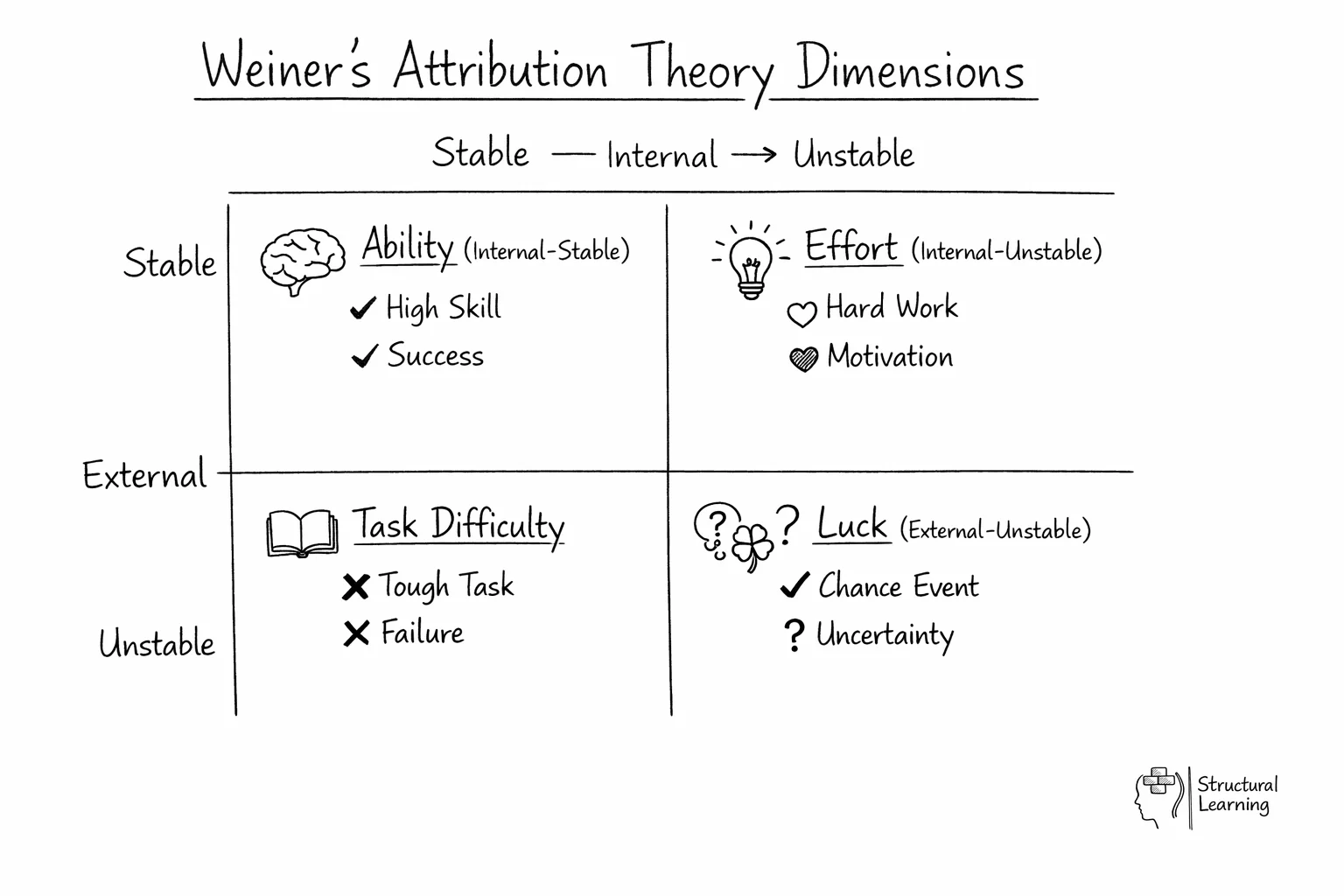

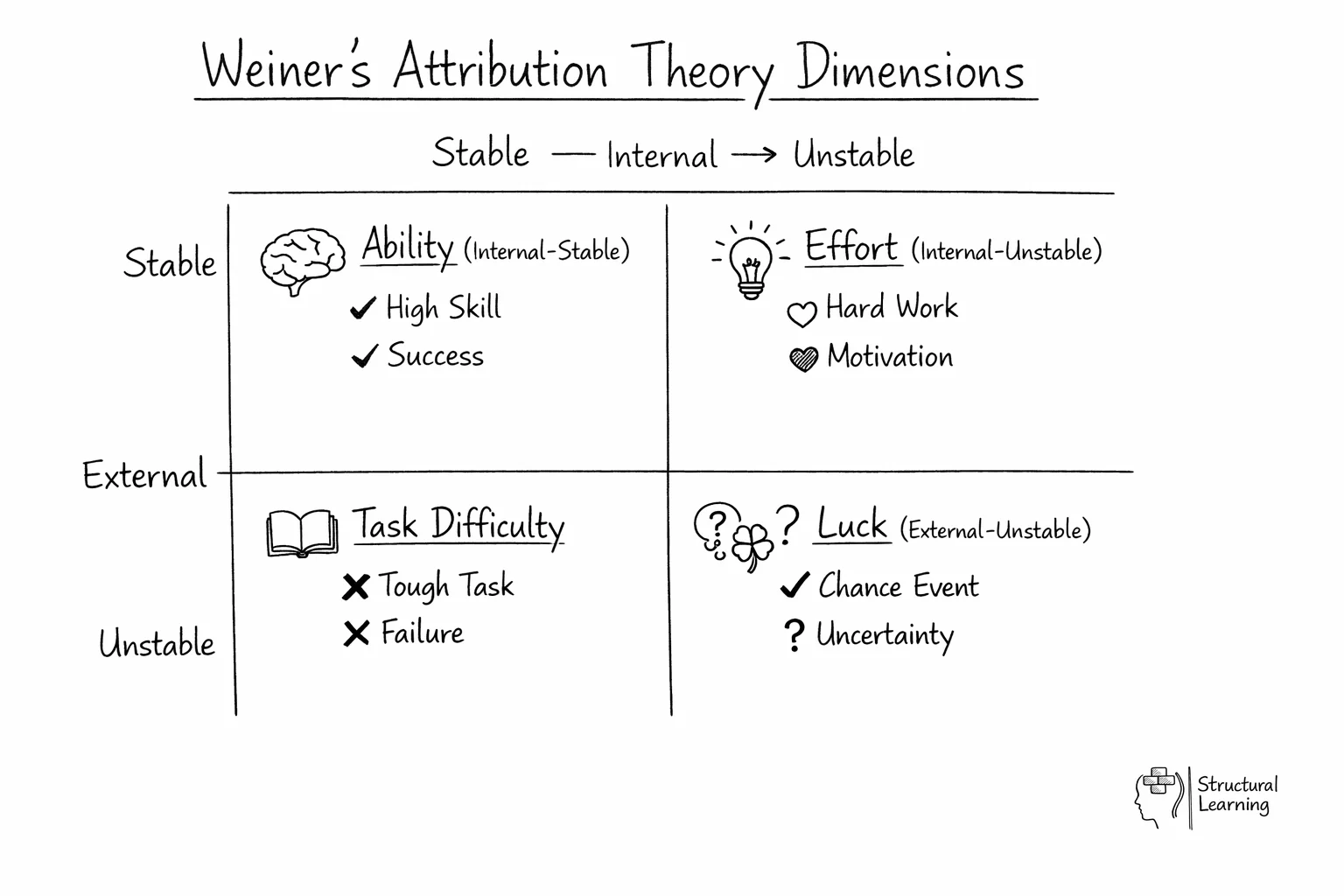

Attribution theory is a social psychology framework that explains how people interpret and assign causes to events and behaviours they observe. It examines whether people attribute outcomes to internal factors (like ability or effort) or external factors (like luck or task difficulty). This process significantly influences attitudes, motivation, and future behaviour.

| Attribution Type | Stable | Unstable |

|---|---|---|

| Internal (within the person) | Ability: "I'm naturally good/bad at this subject" Impact: Affects self-esteem and future expectations | Effort: "I studied hard/didn't try" Impact: Controllable; affects motivation and persistence |

| External (outside the person) | Task Difficulty: "This test is always hard/easy" Impact: Affects expectations but not self-worth | Luck: "I was lucky/unlucky today" Impact: Uncontrollable; minimal impact on future motivation |

Attribution theory, rooted in social psychology, examines the that underlie the attribution process. When individuals encounter events or behaviours, they naturally engage in causal attributions to make sense of them. These attributions can be categorised as dispositional (internal) or situational (external) and can have a significant influence on an , attitudes, and future behaviour. In 2025, understanding how students explain their successes and failures remains central to effective classroom practise.

The way people attribute causes to positive and negative events can greatly affect their motivation and . For instance, attributing success to personal effort rather than task difficulty or external sources can lead to increased self-esteem and a stronger sense of self-efficacy (Zhang & Huang, 2021). Conversely, consistently attributing failures to personal shortcomings can result in decreased self-esteem and a sense of helplessness (Maymon et al., 2018).

Understanding the complexities of human behaviour and the attributions people make is essential for teachers and parents, as it allows them to better support . By recognising the aspects of person perception that contribute to attribution processes, adults can guide children towards more balanced and accurate attributions. This can promote healthier self-perceptions and encourage resilience in the face of challenges.

In the field of education, understanding the attribution process can inform instructional strategies and classroom managementtechniques (Putten, 2017). Educators can emphasise effort and persistence in overcoming challenges, while also acknowledging the role of external factors in shaping outcomes. This approach can help children develop a more nuanced understanding of their own abilities and the factors that contribute to their successes and failures.

Ultimately, by exploring deeper into attribution theory, teachers and parents can better understand the , emotions, and behaviours. This understanding can inform more effective communication, support strategies, and ultimately lead to a more positive and inclusive learning environment for children.

Fritz Heider founded attribution theory in 1958, introducing the concept of internal versus external attributions. Harold Kelley expanded the theory with his covariation model, while Bernard Weiner developed the three-dimensional model adding stability and controllability dimensions. These pioneers established attribution theory as a cornerstone of social psychology.

As part of Bernard Weiner's contribution to attribution theory, he explored the concept of internal attribution, which refers to the belief that an individual's behaviour is driven by personal characteristics, effort, or personality traits (Russen et al., 2025). This perspective highlights the role of in shaping attributions, as individuals often rely on their observations and evaluations of others to make judgments about the causes of behaviour.

Weiner's work on attribution theory also sheds light on the phenomenon of self-serving attributions. Self-serving attributions occur when individuals attribute their successes to their own personal characteristics, while attributing failures to external factors. This bias can serve to protect self-esteem and maintain a positive self-image, even in the face of poor performance or setbacks.

Understanding the nuances of attribution theory, particularly the role of internal attributions and self-serving biases, can have significant implications for educators and parents (Amerstorfer & Münster-Kistner, 2021). By being aware of the potential for these biases to influence children's self-perceptions and emotional responses, adults can help guide them towards more balanced and accurate attributions.

For instance, by encouraging children to consider both internal and external factors when evaluating their performance, adults can encourage a more realistic understanding of their abilities and the factors that contribute to success and failure.

Moreover, Weiner's work on stability and controllability offers valuable insights for supporting children's emotional well-being and motivation. By promoting a focus on controllable factors, such as effort and strategy, adults can help to develop growth mindset and responsibility for their actions. This, in turn, can contribute to a more adaptiv e attribution style and greater resilience in the face of challenges.

The pioneering work of Heider, Kelley, and Weiner in attribution theory provides a strong foundation for understanding the complex interplay between social perception, attributions, and human behaviour. By applying these insights to educational and parenting contexts, adults can create more supportive and effective learning environments that promote positive attributional patterns and enhance children's overall well-being and academic success.

Attribution theory has profound implications for classroom practise, influencing how teachers provide feedback, structure learning experiences, and support student motivation. Understanding student attributions helps educators develop more effective strategies for promoting academic success and emotional well-being.

In educational settings, teachers can apply attribution theory by carefully crafting their feedback to encourage adaptive attributional patterns (Meccawy & Sebai, 2024). When students succeed, educators should highlight the role of effort and effective strategies whilst also acknowledging natural ability. This approach helps students understand that success results from multiple factors, many of which are within their control.

For students experiencing failure, attribution retraining becomes particularly important. Rather than allowing students to attribute poor performance solely to lack of ability (internal, stable, uncontrollable), teachers can guide them to consider factors such as insufficient effort, inappropriate study strategies, or external circumstances (Wang et al., 2022). This shift in perspective can prevent the development of learned helplessness and maintain motivation for future learning attempts.

The concept of self-efficacy closely connects to attribution theory in educational contexts. When students consistently attribute their successes to controllable factors like effort and persistence, they develop stronger beliefs in their ability to achieve future success (Liu et al., 2025). This positive cycle enhances their willingness to tackle challenging tasks and persevere through difficulties.

Teachers can also use attribution theory to address the fundamental attribution error in peer relationships. By helping students understand that behaviour often results from situational factors rather than fixed personality traits, educators can promote more empathetic and understanding classroom communities. This approach is particularly valuable in behaviour management situations where students may quickly judge their classmates.

Furthermore, attribution theory informs differentiated instruction approaches (Alkhateeb & Abushihab, 2025). Understanding that students may have varying attributional styles allows teachers to tailor their support accordingly. Some students may need encouragement to take credit for their successes, whilst others may require support in accepting responsibility for areas requiring improvement.

Bernard Weiner's foundational research identified four distinct types of attributions that students make about their academic performance, each with profound implications for motivation and future learning behaviour. These attributions fall along two key dimensions: locus of control (internal versus external) and stability (stable versus unstable). Internal attributions locate the cause within the student themselves, such as ability or effort, whilst external attributions point to factors outside their control, like task difficulty or teacher behaviour. The stability dimension determines whether students view causes as changeable over time or relatively fixed.

Understanding these attribution patterns proves invaluable in educational settings. When students attribute success to internal, unstable factors like effort ("I worked hard on this essay"), they maintain both confidence and motivation for future tasks. Conversely, attributing failure to internal, stable factors such as lack of ability ("I'm just not good at mathematics") can lead to learned helplessness and academic disengagement. Teachers can recognise these patterns through student language and responses to feedback.

Effective classroom applications involve actively reshaping student attributions through strategic feedback. Rather than praising ability ("You're naturally gifted at science"), focus on effort and strategy ("Your systematic approach to this experiment led to excellent results"). This approach encourages students to view academic performance as controllable and improvable, developing resilience and continued engagement with challenging material.

Extensive research evidence supports the practical application of attribution theory in educational settings. Weiner's seminal studies in the 1980s demonstrated that students who attribute academic success to effort and effective strategies show greater persistence and improved performance compared to those who attribute outcomes to fixed ability. More recent longitudinal research by Carol Dweck and her colleagues has consistently shown that teaching students to make effort-based attributions leads to measurable improvements in academic achievement, particularly during challenging transitions such as moving to secondary school.

Classroom-based intervention studies provide compelling evidence for attribution retraining programmes. Research by Wilson and Linville found that students who received brief attribution training, learning to attribute academic difficulties to unstable factors like insufficient study techniques rather than low ability, showed significant improvements in subsequent performance. Similarly, Perry and Penner's work with university students revealed that attribution retraining combined with strategy instruction produced the most substantial gains in both academic performance and student motivation.

For practising educators, these findings translate into evidence-based teaching strategies. The research consistently indicates that providing process-focused feedback, explicitly teaching students to recognise the role of effort and strategy in learning outcomes, and helping students reframe failures as learning opportunities can significantly enhance student engagement and achievement in educational settings.

Effective attribution training in educational settings begins with how teachers frame feedback and respond to student performance. When students struggle, educators should emphasise effort and strategy rather than ability, helping learners understand that academic challenges reflect opportunities for growth rather than fixed limitations. Research by Carol Dweck demonstrates that praising process over intelligence cultivates resilience and sustained motivation, whilst comments focusing on innate ability can inadvertently discourage students from tackling difficult tasks.

Teachers can systematically reshape classroom discourse by modelling appropriate attributions during instruction. Instead of saying "You're naturally good at mathematics," educators might observe "Your systematic approach to solving these problems is paying off." Similarly, when addressing setbacks, teachers should guide students towards controllable factors: "What strategies might work better next time?" rather than accepting explanations like "I'm just bad at writing." This consistent reframing helps students develop internal attributional patterns that support academic persistence.

Practical implementation involves establishing classroom routines that reinforce growth-oriented thinking. Weekly reflection activities where students identify specific strategies that contributed to their learning, alongside regular discussions about overcoming challenges, normalise the connection between effort and achievement. These approaches, grounded in attribution theory principles, create learning environments where students view setbacks as temporary and surmountable rather than indicative of personal inadequacy.

The attributions students make about their academic successes and failures directly influence their motivation to engage with learning tasks. When students attribute their achievements to controllable factors such as effort and strategy use, they demonstrate higher levels of intrinsic motivation and persistence in the face of challenges. Conversely, students who consistently attribute outcomes to uncontrollable factors like ability or luck often exhibit learned helplessness behaviours, reducing their willingness to tackle difficult problems or persevere through setbacks.

When students explain why events happen, they typically point to either dispositional (internal) or situational (external) causes. Dispositional attributions relate to personal characteristics, traits, or abilities within the individual. Situational attributions focus on environmental factors, circumstances, or influences outside the person's control. Understanding this distinction helps teachers recognise how students interpret their academic experiences and shape their learning mindsets.

Consider a student who fails a maths test. A dispositional attribution might be "I'm terrible at maths" (ability) or "I didn't study enough" (effort). A situational attribution could be "The test was unfair" (task difficulty) or "The classroom was too noisy" (environmental factors). These different explanations profoundly affect how students approach future challenges.

Teachers can guide students towards healthier attribution patterns through specific strategies. First, when providing feedback, explicitly highlight the role of effort and strategy rather than fixed ability. Instead of saying "You're naturally gifted at writing," try "Your careful planning and revision really improved this essay." This reinforces the controllable nature of success.

Second, help students analyse their attributions through reflection activities. After assessments, ask students to complete attribution questionnaires identifying whether they believe their performance resulted from effort, ability, luck, or task difficulty. This awareness allows students to recognise unhelpful patterns, such as attributing all failures to lack of ability whilst dismissing successes as luck.

Research by Dweck (2006) demonstrates that students who attribute outcomes to controllable factors like effort show greater resilience and improved performance over time. By teaching students to distinguish between dispositional and situational factors, and encouraging appropriate attributions, teachers can build more confident, motivated learners who view challenges as opportunities rather than threats.

Attribution biases shape how students and teachers interpret classroom experiences, often leading to misunderstandings that affect learning outcomes. The fundamental attribution error, perhaps the most pervasive bias, occurs when we attribute others' behaviour to their personality whilst overlooking situational factors. In classrooms, this manifests when teachers assume a student's poor performance stems from laziness rather than considering external circumstances like family stress or inadequate resources.

Beyond this primary bias, several others influence educational settings. The self-serving bias leads students to attribute success to internal factors ("I'm clever") but failures to external ones ("The test was unfair"). Conversely, students with low self-esteem may exhibit a self-defeating bias, attributing failures internally and successes externally. The actor-observer bias creates another layer of complexity; students judge their own actions by situational factors whilst judging peers' actions by personality traits.

Teachers can address these biases through specific strategies. First, implement structured reflection activities where students analyse both internal and external factors contributing to their outcomes. For instance, after assessments, ask students to complete attribution charts listing all possible causes for their performance.

Second, model balanced attributions in your feedback. Rather than saying "You're naturally gifted at maths," try "Your consistent practise and problem-solving approach led to this success." This helps students recognise controllable factors in their achievements.

Research by Dweck (2006) demonstrates that awareness of attribution biases significantly improves student resilience and academic performance. By explicitly teaching students about these biases and providing tools to recognise them, educators can help develop more accurate self-perceptions and healthier responses to both success and failure.

Harold Kelley's covariation model provides teachers with a structured framework for understanding how students make attributions about their own and others' behaviour. The model identifies three key factors that influence attribution: consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency. By recognising these patterns, educators can better interpret student responses and guide more accurate self-assessments.

Consensus refers to whether other people behave similarly in the same situation. For instance, if most students struggle with a particular maths problem, a student is more likely to attribute their difficulty to external factors like task complexity rather than personal inadequacy. Teachers can use this insight by sharing class-wide performance data, helping struggling students recognise when challenges are common rather than individual.

Distinctiveness examines whether the behaviour occurs across different situations. A student who excels only in science but struggles elsewhere shows high distinctiveness, suggesting their success relates to subject-specific factors. Teachers might explore what makes science different for this student; perhaps hands-on experiments suit their learning style, information that could inform approaches in other subjects.

Consistency looks at whether the behaviour repeats over time. A student who consistently arrives late to morning lessons but is punctual after lunch demonstrates a pattern worth investigating. Rather than attributing this to laziness (internal attribution), teachers might discover external factors like unreliable transport or caring responsibilities.

Practical application involves teaching students to analyse their own attributions systematically. When reviewing test results, guide students through these three questions: Did others find it difficult? Do I struggle only with this subject?

Is this a recurring pattern? This structured reflection helps students develop more accurate and helpful explanations for their academic experiences, moving beyond simplistic "I'm just bad at this" attributions.

Carol Dweck's research on mindset theory illustrates how attribution patterns can be reshaped through targeted interventions. Students with a growth mindset naturally attribute performance to effort and learning processes, whilst those with a fixed mindset focus on innate ability. In educational settings, this translates to measurable differences in academic resilience and achievement over time.

Effective classroom applications include teaching students to recognise and reframe their attributional thinking. Educators can model appropriate attributions by highlighting the connection between specific strategies and successful outcomes, avoiding praise that emphasises innate talent. Encouraging students to reflect on their learning processes and celebrate improvement rather than just final grades helps establish productive attribution patterns that sustain long-term academic motivation.

Attribution theory provides educators and parents with a powerful framework for understanding how children interpret their experiences and develop beliefs about their capabilities. By recognising the profound impact that attributional patterns have on motivation, self-esteem, and future behaviour, adults can create more supportive learning environments that promote healthy psychological development.

The practical applications of attribution theory extend far beyond academic achievement, influencing how children approach challenges, interact with peers, and develop resilience. When educators consciously apply attribution theory principles in their feedback, instruction, and classroom management, they help students develop more balanced and adaptive ways of understanding their world. This foundation supports not only immediate learning outcomes but also lifelong patterns of thinking and responding to both success and failure.

As educational practise continues to evolve, attribution theory remains a cornerstone for understanding student motivation and behaviour. By integrating these insights into daily practise, teachers can creates environments where all students develop healthy attributional styles, enhanced self-efficacy, and the confidence to pursue their learning goals with persistence and optimism.

Understanding the difference between dispositional and situational attribution forms the foundation of attribution theory in educational settings. Dispositional attribution occurs when we explain behaviour through personal characteristics, traits, or internal factors. Situational attribution, conversely, attributes behaviour to external circumstances, environmental factors, or specific contexts.

Consider a Year 9 student who fails a maths test. A dispositional attribution might be "Sarah is lazy" or "She lacks mathematical ability." A situational attribution would consider external factors: "The test covered material taught whilst Sarah was ill" or "The classroom was noisy during the exam." This distinction profoundly affects how teachers respond to student performance and behaviour.

Research by Ross (1977) demonstrated that people consistently overestimate dispositional factors when judging others, a phenomenon known as the fundamental attribution error. In classrooms, this bias can lead teachers to label students as "disruptive" or "unmotivated" without considering situational factors like family stress, peer conflicts, or unclear instructions.

To counter this bias, effective teachers employ several strategies. First, they gather context before making judgements; a behaviour tracking sheet that includes time of day, subject, and recent events helps identify patterns. Second, they use neutral language when discussing student behaviour, focusing on specific actions rather than character traits. Instead of "Tom is aggressive," they might note "Tom pushed another student during PE after losing a game."

Training students to recognise these attribution patterns also proves valuable. When reviewing test results, teachers can guide students to identify both dispositional factors (effort, preparation) and situational factors (test anxiety, distractions) that influenced their performance. This balanced perspective helps students develop more accurate self-assessments and adaptive learning strategies.

The Correspondent Inference Theory, developed by Edward Jones and Keith Davis in 1965, offers teachers valuable insights into how students form judgements about each other's behaviour. This theory explores how we infer someone's personality traits or dispositions from their actions, particularly in classroom settings where social dynamics play a crucial role.

According to Jones and Davis, people are more likely to make correspondent inferences (assuming behaviour reflects personality) when certain conditions are met. First, the behaviour must appear intentional rather than accidental. Second, the action should produce non-common effects; unique outcomes that wouldn't result from alternative behaviours. Finally, the behaviour should violate social expectations or norms, making it more noticeable and informative about the person's character.

In classroom contexts, this theory helps explain common attribution patterns. When a typically quiet student suddenly speaks out passionately about a topic, teachers and peers are likely to infer genuine interest or strong personal values, as this behaviour deviates from expectations. Similarly, if a student chooses to work alone on a group project despite social pressure to collaborate, observers might conclude they are independently minded or antisocial, depending on the context.

Teachers can apply this understanding in several practical ways. First, encourage students to consider multiple explanations for their peers' behaviour before making personality judgements. For instance, a student arriving late might be dealing with transport issues rather than being irresponsible.

Second, create opportunities for students to display various behaviours across different contexts, helping classmates form more accurate impressions. Finally, explicitly teach about attribution biases during PSHE lessons, using real classroom scenarios to illustrate how quick judgements can lead to misunderstandings and conflict.

Harold Kelley's covariation model (1967) provides teachers with a systematic framework for understanding how students make causal attributions. The model identifies three key factors that influence whether we attribute behaviour to internal or external causes: consensus, consistency, and distinctiveness.

Consensus refers to whether other people behave similarly in the same situation. If Emma struggles with fractions whilst most classmates understand them easily (low consensus), students are likely to make internal attributions about Emma's ability. However, if the entire class finds fractions challenging (high consensus), they'll attribute the difficulty to external factors like teaching methods or topic complexity.

Consistency examines whether the behaviour occurs regularly over time. When Tom consistently arrives late to maths lessons, students and teachers make internal attributions about his punctuality or motivation. Conversely, if Tom is late just once, external attributions like traffic or family circumstances become more likely.

Distinctiveness considers whether the behaviour is specific to one situation or occurs across multiple contexts. If Sarah only misbehaves in science lessons (high distinctiveness), attributions focus on external factors specific to that class. If she disrupts all lessons (low distinctiveness), internal attributions about her behaviour patterns emerge.

Teachers can apply this model practically by helping students analyse their own attribution patterns. When a student claims "I'm terrible at languages," encourage them to consider: Do others find French difficult? (consensus) Have they always struggled, or is this new?

(consistency) Do they excel in other subjects requiring similar skills? (distinctiveness). This structured reflection helps students develop more balanced, accurate attributions that support learning rather than create limiting beliefs.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the evidence base for the strategies discussed above.

Entrepreneurship education of college students and entrepreneurial psychology of new entrepreneurs under causal attribution theory View study ↗

Xie et al. (2022)

This study examines how attribution theory can optimise entrepreneurship education teaching strategies for university students. Teachers can apply these findings to better understand how students attribute their entrepreneurial successes and failures, helping develop more effective pedagogical approaches that foster entrepreneurial mindset and innovation skills.

The Path of College Students’ Entrepreneurship Education Under Causal Attribution Theory From the Perspective of Entrepreneurial Psychology View study ↗

Wang et al. (2022)

This research explores using attribution theory to enhance university entrepreneurship education from a psychological perspective. Teachers can utilise these insights to understand student motivations and psychological barriers to entrepreneurship, enabling them to design curricula that better support student engagement with entrepreneurial learning opportunities.

The Role of Taxpayer Awareness in Enhancing Vehicle Tax Compliance in Indonesia: An Attribution Theory Approach View study ↗

11 citations

Erasashanti et al. (2024)

This study applies attribution theory to examine taxpayer compliance behaviour in Indonesia. Whilst not directly classroom-focused, it demonstrates how attribution theory can explain compliance behaviours, offering teachers insights into understanding student adherence to academic rules and institutional expectations.

Attribution Analysis of English Learning Anxiety for Master’s Degree Graduates of Physical Education and Examination Relief Countermeasures —— From the perspective of Weiner’s attribution theory View study ↗

Zhang et al. (2021)

This research uses Weiner's attribution theory to analyse English learning anxiety among physical education graduates. Teachers can apply these findings to identify how students attribute their language learning difficulties, enabling more targeted interventions to reduce anxiety and improve English learning outcomes.

Third Language Learning: Insights from MA Students Through the L2 Motivational Self-System & Attribution Theory Lenses View study ↗

Meccawy et al. (2024)

This qualitative study examines why students discontinue third language learning using attribution theory and motivational frameworks. Teachers can use these insights to understand student attrition in language programmes and develop strategies to maintain student motivation and engagement in multilingual education.

Attribution theory is a social psychology framework that explains how people interpret and assign causes to events and behaviours they observe. It examines whether people attribute outcomes to internal factors (like ability or effort) or external factors (like luck or task difficulty). This process significantly influences attitudes, motivation, and future behaviour.

| Attribution Type | Stable | Unstable |

|---|---|---|

| Internal (within the person) | Ability: "I'm naturally good/bad at this subject" Impact: Affects self-esteem and future expectations | Effort: "I studied hard/didn't try" Impact: Controllable; affects motivation and persistence |

| External (outside the person) | Task Difficulty: "This test is always hard/easy" Impact: Affects expectations but not self-worth | Luck: "I was lucky/unlucky today" Impact: Uncontrollable; minimal impact on future motivation |

Attribution theory, rooted in social psychology, examines the that underlie the attribution process. When individuals encounter events or behaviours, they naturally engage in causal attributions to make sense of them. These attributions can be categorised as dispositional (internal) or situational (external) and can have a significant influence on an , attitudes, and future behaviour. In 2025, understanding how students explain their successes and failures remains central to effective classroom practise.

The way people attribute causes to positive and negative events can greatly affect their motivation and . For instance, attributing success to personal effort rather than task difficulty or external sources can lead to increased self-esteem and a stronger sense of self-efficacy (Zhang & Huang, 2021). Conversely, consistently attributing failures to personal shortcomings can result in decreased self-esteem and a sense of helplessness (Maymon et al., 2018).

Understanding the complexities of human behaviour and the attributions people make is essential for teachers and parents, as it allows them to better support . By recognising the aspects of person perception that contribute to attribution processes, adults can guide children towards more balanced and accurate attributions. This can promote healthier self-perceptions and encourage resilience in the face of challenges.

In the field of education, understanding the attribution process can inform instructional strategies and classroom managementtechniques (Putten, 2017). Educators can emphasise effort and persistence in overcoming challenges, while also acknowledging the role of external factors in shaping outcomes. This approach can help children develop a more nuanced understanding of their own abilities and the factors that contribute to their successes and failures.

Ultimately, by exploring deeper into attribution theory, teachers and parents can better understand the , emotions, and behaviours. This understanding can inform more effective communication, support strategies, and ultimately lead to a more positive and inclusive learning environment for children.

Fritz Heider founded attribution theory in 1958, introducing the concept of internal versus external attributions. Harold Kelley expanded the theory with his covariation model, while Bernard Weiner developed the three-dimensional model adding stability and controllability dimensions. These pioneers established attribution theory as a cornerstone of social psychology.

As part of Bernard Weiner's contribution to attribution theory, he explored the concept of internal attribution, which refers to the belief that an individual's behaviour is driven by personal characteristics, effort, or personality traits (Russen et al., 2025). This perspective highlights the role of in shaping attributions, as individuals often rely on their observations and evaluations of others to make judgments about the causes of behaviour.

Weiner's work on attribution theory also sheds light on the phenomenon of self-serving attributions. Self-serving attributions occur when individuals attribute their successes to their own personal characteristics, while attributing failures to external factors. This bias can serve to protect self-esteem and maintain a positive self-image, even in the face of poor performance or setbacks.

Understanding the nuances of attribution theory, particularly the role of internal attributions and self-serving biases, can have significant implications for educators and parents (Amerstorfer & Münster-Kistner, 2021). By being aware of the potential for these biases to influence children's self-perceptions and emotional responses, adults can help guide them towards more balanced and accurate attributions.

For instance, by encouraging children to consider both internal and external factors when evaluating their performance, adults can encourage a more realistic understanding of their abilities and the factors that contribute to success and failure.

Moreover, Weiner's work on stability and controllability offers valuable insights for supporting children's emotional well-being and motivation. By promoting a focus on controllable factors, such as effort and strategy, adults can help to develop growth mindset and responsibility for their actions. This, in turn, can contribute to a more adaptiv e attribution style and greater resilience in the face of challenges.

The pioneering work of Heider, Kelley, and Weiner in attribution theory provides a strong foundation for understanding the complex interplay between social perception, attributions, and human behaviour. By applying these insights to educational and parenting contexts, adults can create more supportive and effective learning environments that promote positive attributional patterns and enhance children's overall well-being and academic success.

Attribution theory has profound implications for classroom practise, influencing how teachers provide feedback, structure learning experiences, and support student motivation. Understanding student attributions helps educators develop more effective strategies for promoting academic success and emotional well-being.

In educational settings, teachers can apply attribution theory by carefully crafting their feedback to encourage adaptive attributional patterns (Meccawy & Sebai, 2024). When students succeed, educators should highlight the role of effort and effective strategies whilst also acknowledging natural ability. This approach helps students understand that success results from multiple factors, many of which are within their control.

For students experiencing failure, attribution retraining becomes particularly important. Rather than allowing students to attribute poor performance solely to lack of ability (internal, stable, uncontrollable), teachers can guide them to consider factors such as insufficient effort, inappropriate study strategies, or external circumstances (Wang et al., 2022). This shift in perspective can prevent the development of learned helplessness and maintain motivation for future learning attempts.

The concept of self-efficacy closely connects to attribution theory in educational contexts. When students consistently attribute their successes to controllable factors like effort and persistence, they develop stronger beliefs in their ability to achieve future success (Liu et al., 2025). This positive cycle enhances their willingness to tackle challenging tasks and persevere through difficulties.

Teachers can also use attribution theory to address the fundamental attribution error in peer relationships. By helping students understand that behaviour often results from situational factors rather than fixed personality traits, educators can promote more empathetic and understanding classroom communities. This approach is particularly valuable in behaviour management situations where students may quickly judge their classmates.

Furthermore, attribution theory informs differentiated instruction approaches (Alkhateeb & Abushihab, 2025). Understanding that students may have varying attributional styles allows teachers to tailor their support accordingly. Some students may need encouragement to take credit for their successes, whilst others may require support in accepting responsibility for areas requiring improvement.

Bernard Weiner's foundational research identified four distinct types of attributions that students make about their academic performance, each with profound implications for motivation and future learning behaviour. These attributions fall along two key dimensions: locus of control (internal versus external) and stability (stable versus unstable). Internal attributions locate the cause within the student themselves, such as ability or effort, whilst external attributions point to factors outside their control, like task difficulty or teacher behaviour. The stability dimension determines whether students view causes as changeable over time or relatively fixed.

Understanding these attribution patterns proves invaluable in educational settings. When students attribute success to internal, unstable factors like effort ("I worked hard on this essay"), they maintain both confidence and motivation for future tasks. Conversely, attributing failure to internal, stable factors such as lack of ability ("I'm just not good at mathematics") can lead to learned helplessness and academic disengagement. Teachers can recognise these patterns through student language and responses to feedback.

Effective classroom applications involve actively reshaping student attributions through strategic feedback. Rather than praising ability ("You're naturally gifted at science"), focus on effort and strategy ("Your systematic approach to this experiment led to excellent results"). This approach encourages students to view academic performance as controllable and improvable, developing resilience and continued engagement with challenging material.

Extensive research evidence supports the practical application of attribution theory in educational settings. Weiner's seminal studies in the 1980s demonstrated that students who attribute academic success to effort and effective strategies show greater persistence and improved performance compared to those who attribute outcomes to fixed ability. More recent longitudinal research by Carol Dweck and her colleagues has consistently shown that teaching students to make effort-based attributions leads to measurable improvements in academic achievement, particularly during challenging transitions such as moving to secondary school.

Classroom-based intervention studies provide compelling evidence for attribution retraining programmes. Research by Wilson and Linville found that students who received brief attribution training, learning to attribute academic difficulties to unstable factors like insufficient study techniques rather than low ability, showed significant improvements in subsequent performance. Similarly, Perry and Penner's work with university students revealed that attribution retraining combined with strategy instruction produced the most substantial gains in both academic performance and student motivation.

For practising educators, these findings translate into evidence-based teaching strategies. The research consistently indicates that providing process-focused feedback, explicitly teaching students to recognise the role of effort and strategy in learning outcomes, and helping students reframe failures as learning opportunities can significantly enhance student engagement and achievement in educational settings.

Effective attribution training in educational settings begins with how teachers frame feedback and respond to student performance. When students struggle, educators should emphasise effort and strategy rather than ability, helping learners understand that academic challenges reflect opportunities for growth rather than fixed limitations. Research by Carol Dweck demonstrates that praising process over intelligence cultivates resilience and sustained motivation, whilst comments focusing on innate ability can inadvertently discourage students from tackling difficult tasks.

Teachers can systematically reshape classroom discourse by modelling appropriate attributions during instruction. Instead of saying "You're naturally good at mathematics," educators might observe "Your systematic approach to solving these problems is paying off." Similarly, when addressing setbacks, teachers should guide students towards controllable factors: "What strategies might work better next time?" rather than accepting explanations like "I'm just bad at writing." This consistent reframing helps students develop internal attributional patterns that support academic persistence.

Practical implementation involves establishing classroom routines that reinforce growth-oriented thinking. Weekly reflection activities where students identify specific strategies that contributed to their learning, alongside regular discussions about overcoming challenges, normalise the connection between effort and achievement. These approaches, grounded in attribution theory principles, create learning environments where students view setbacks as temporary and surmountable rather than indicative of personal inadequacy.

The attributions students make about their academic successes and failures directly influence their motivation to engage with learning tasks. When students attribute their achievements to controllable factors such as effort and strategy use, they demonstrate higher levels of intrinsic motivation and persistence in the face of challenges. Conversely, students who consistently attribute outcomes to uncontrollable factors like ability or luck often exhibit learned helplessness behaviours, reducing their willingness to tackle difficult problems or persevere through setbacks.

When students explain why events happen, they typically point to either dispositional (internal) or situational (external) causes. Dispositional attributions relate to personal characteristics, traits, or abilities within the individual. Situational attributions focus on environmental factors, circumstances, or influences outside the person's control. Understanding this distinction helps teachers recognise how students interpret their academic experiences and shape their learning mindsets.

Consider a student who fails a maths test. A dispositional attribution might be "I'm terrible at maths" (ability) or "I didn't study enough" (effort). A situational attribution could be "The test was unfair" (task difficulty) or "The classroom was too noisy" (environmental factors). These different explanations profoundly affect how students approach future challenges.

Teachers can guide students towards healthier attribution patterns through specific strategies. First, when providing feedback, explicitly highlight the role of effort and strategy rather than fixed ability. Instead of saying "You're naturally gifted at writing," try "Your careful planning and revision really improved this essay." This reinforces the controllable nature of success.

Second, help students analyse their attributions through reflection activities. After assessments, ask students to complete attribution questionnaires identifying whether they believe their performance resulted from effort, ability, luck, or task difficulty. This awareness allows students to recognise unhelpful patterns, such as attributing all failures to lack of ability whilst dismissing successes as luck.

Research by Dweck (2006) demonstrates that students who attribute outcomes to controllable factors like effort show greater resilience and improved performance over time. By teaching students to distinguish between dispositional and situational factors, and encouraging appropriate attributions, teachers can build more confident, motivated learners who view challenges as opportunities rather than threats.

Attribution biases shape how students and teachers interpret classroom experiences, often leading to misunderstandings that affect learning outcomes. The fundamental attribution error, perhaps the most pervasive bias, occurs when we attribute others' behaviour to their personality whilst overlooking situational factors. In classrooms, this manifests when teachers assume a student's poor performance stems from laziness rather than considering external circumstances like family stress or inadequate resources.

Beyond this primary bias, several others influence educational settings. The self-serving bias leads students to attribute success to internal factors ("I'm clever") but failures to external ones ("The test was unfair"). Conversely, students with low self-esteem may exhibit a self-defeating bias, attributing failures internally and successes externally. The actor-observer bias creates another layer of complexity; students judge their own actions by situational factors whilst judging peers' actions by personality traits.

Teachers can address these biases through specific strategies. First, implement structured reflection activities where students analyse both internal and external factors contributing to their outcomes. For instance, after assessments, ask students to complete attribution charts listing all possible causes for their performance.

Second, model balanced attributions in your feedback. Rather than saying "You're naturally gifted at maths," try "Your consistent practise and problem-solving approach led to this success." This helps students recognise controllable factors in their achievements.

Research by Dweck (2006) demonstrates that awareness of attribution biases significantly improves student resilience and academic performance. By explicitly teaching students about these biases and providing tools to recognise them, educators can help develop more accurate self-perceptions and healthier responses to both success and failure.

Harold Kelley's covariation model provides teachers with a structured framework for understanding how students make attributions about their own and others' behaviour. The model identifies three key factors that influence attribution: consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency. By recognising these patterns, educators can better interpret student responses and guide more accurate self-assessments.

Consensus refers to whether other people behave similarly in the same situation. For instance, if most students struggle with a particular maths problem, a student is more likely to attribute their difficulty to external factors like task complexity rather than personal inadequacy. Teachers can use this insight by sharing class-wide performance data, helping struggling students recognise when challenges are common rather than individual.

Distinctiveness examines whether the behaviour occurs across different situations. A student who excels only in science but struggles elsewhere shows high distinctiveness, suggesting their success relates to subject-specific factors. Teachers might explore what makes science different for this student; perhaps hands-on experiments suit their learning style, information that could inform approaches in other subjects.

Consistency looks at whether the behaviour repeats over time. A student who consistently arrives late to morning lessons but is punctual after lunch demonstrates a pattern worth investigating. Rather than attributing this to laziness (internal attribution), teachers might discover external factors like unreliable transport or caring responsibilities.

Practical application involves teaching students to analyse their own attributions systematically. When reviewing test results, guide students through these three questions: Did others find it difficult? Do I struggle only with this subject?

Is this a recurring pattern? This structured reflection helps students develop more accurate and helpful explanations for their academic experiences, moving beyond simplistic "I'm just bad at this" attributions.

Carol Dweck's research on mindset theory illustrates how attribution patterns can be reshaped through targeted interventions. Students with a growth mindset naturally attribute performance to effort and learning processes, whilst those with a fixed mindset focus on innate ability. In educational settings, this translates to measurable differences in academic resilience and achievement over time.

Effective classroom applications include teaching students to recognise and reframe their attributional thinking. Educators can model appropriate attributions by highlighting the connection between specific strategies and successful outcomes, avoiding praise that emphasises innate talent. Encouraging students to reflect on their learning processes and celebrate improvement rather than just final grades helps establish productive attribution patterns that sustain long-term academic motivation.

Attribution theory provides educators and parents with a powerful framework for understanding how children interpret their experiences and develop beliefs about their capabilities. By recognising the profound impact that attributional patterns have on motivation, self-esteem, and future behaviour, adults can create more supportive learning environments that promote healthy psychological development.

The practical applications of attribution theory extend far beyond academic achievement, influencing how children approach challenges, interact with peers, and develop resilience. When educators consciously apply attribution theory principles in their feedback, instruction, and classroom management, they help students develop more balanced and adaptive ways of understanding their world. This foundation supports not only immediate learning outcomes but also lifelong patterns of thinking and responding to both success and failure.

As educational practise continues to evolve, attribution theory remains a cornerstone for understanding student motivation and behaviour. By integrating these insights into daily practise, teachers can creates environments where all students develop healthy attributional styles, enhanced self-efficacy, and the confidence to pursue their learning goals with persistence and optimism.

Understanding the difference between dispositional and situational attribution forms the foundation of attribution theory in educational settings. Dispositional attribution occurs when we explain behaviour through personal characteristics, traits, or internal factors. Situational attribution, conversely, attributes behaviour to external circumstances, environmental factors, or specific contexts.

Consider a Year 9 student who fails a maths test. A dispositional attribution might be "Sarah is lazy" or "She lacks mathematical ability." A situational attribution would consider external factors: "The test covered material taught whilst Sarah was ill" or "The classroom was noisy during the exam." This distinction profoundly affects how teachers respond to student performance and behaviour.

Research by Ross (1977) demonstrated that people consistently overestimate dispositional factors when judging others, a phenomenon known as the fundamental attribution error. In classrooms, this bias can lead teachers to label students as "disruptive" or "unmotivated" without considering situational factors like family stress, peer conflicts, or unclear instructions.

To counter this bias, effective teachers employ several strategies. First, they gather context before making judgements; a behaviour tracking sheet that includes time of day, subject, and recent events helps identify patterns. Second, they use neutral language when discussing student behaviour, focusing on specific actions rather than character traits. Instead of "Tom is aggressive," they might note "Tom pushed another student during PE after losing a game."

Training students to recognise these attribution patterns also proves valuable. When reviewing test results, teachers can guide students to identify both dispositional factors (effort, preparation) and situational factors (test anxiety, distractions) that influenced their performance. This balanced perspective helps students develop more accurate self-assessments and adaptive learning strategies.

The Correspondent Inference Theory, developed by Edward Jones and Keith Davis in 1965, offers teachers valuable insights into how students form judgements about each other's behaviour. This theory explores how we infer someone's personality traits or dispositions from their actions, particularly in classroom settings where social dynamics play a crucial role.

According to Jones and Davis, people are more likely to make correspondent inferences (assuming behaviour reflects personality) when certain conditions are met. First, the behaviour must appear intentional rather than accidental. Second, the action should produce non-common effects; unique outcomes that wouldn't result from alternative behaviours. Finally, the behaviour should violate social expectations or norms, making it more noticeable and informative about the person's character.

In classroom contexts, this theory helps explain common attribution patterns. When a typically quiet student suddenly speaks out passionately about a topic, teachers and peers are likely to infer genuine interest or strong personal values, as this behaviour deviates from expectations. Similarly, if a student chooses to work alone on a group project despite social pressure to collaborate, observers might conclude they are independently minded or antisocial, depending on the context.

Teachers can apply this understanding in several practical ways. First, encourage students to consider multiple explanations for their peers' behaviour before making personality judgements. For instance, a student arriving late might be dealing with transport issues rather than being irresponsible.

Second, create opportunities for students to display various behaviours across different contexts, helping classmates form more accurate impressions. Finally, explicitly teach about attribution biases during PSHE lessons, using real classroom scenarios to illustrate how quick judgements can lead to misunderstandings and conflict.

Harold Kelley's covariation model (1967) provides teachers with a systematic framework for understanding how students make causal attributions. The model identifies three key factors that influence whether we attribute behaviour to internal or external causes: consensus, consistency, and distinctiveness.

Consensus refers to whether other people behave similarly in the same situation. If Emma struggles with fractions whilst most classmates understand them easily (low consensus), students are likely to make internal attributions about Emma's ability. However, if the entire class finds fractions challenging (high consensus), they'll attribute the difficulty to external factors like teaching methods or topic complexity.

Consistency examines whether the behaviour occurs regularly over time. When Tom consistently arrives late to maths lessons, students and teachers make internal attributions about his punctuality or motivation. Conversely, if Tom is late just once, external attributions like traffic or family circumstances become more likely.

Distinctiveness considers whether the behaviour is specific to one situation or occurs across multiple contexts. If Sarah only misbehaves in science lessons (high distinctiveness), attributions focus on external factors specific to that class. If she disrupts all lessons (low distinctiveness), internal attributions about her behaviour patterns emerge.

Teachers can apply this model practically by helping students analyse their own attribution patterns. When a student claims "I'm terrible at languages," encourage them to consider: Do others find French difficult? (consensus) Have they always struggled, or is this new?

(consistency) Do they excel in other subjects requiring similar skills? (distinctiveness). This structured reflection helps students develop more balanced, accurate attributions that support learning rather than create limiting beliefs.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the evidence base for the strategies discussed above.

Entrepreneurship education of college students and entrepreneurial psychology of new entrepreneurs under causal attribution theory View study ↗

Xie et al. (2022)

This study examines how attribution theory can optimise entrepreneurship education teaching strategies for university students. Teachers can apply these findings to better understand how students attribute their entrepreneurial successes and failures, helping develop more effective pedagogical approaches that foster entrepreneurial mindset and innovation skills.

The Path of College Students’ Entrepreneurship Education Under Causal Attribution Theory From the Perspective of Entrepreneurial Psychology View study ↗

Wang et al. (2022)

This research explores using attribution theory to enhance university entrepreneurship education from a psychological perspective. Teachers can utilise these insights to understand student motivations and psychological barriers to entrepreneurship, enabling them to design curricula that better support student engagement with entrepreneurial learning opportunities.

The Role of Taxpayer Awareness in Enhancing Vehicle Tax Compliance in Indonesia: An Attribution Theory Approach View study ↗

11 citations

Erasashanti et al. (2024)

This study applies attribution theory to examine taxpayer compliance behaviour in Indonesia. Whilst not directly classroom-focused, it demonstrates how attribution theory can explain compliance behaviours, offering teachers insights into understanding student adherence to academic rules and institutional expectations.

Attribution Analysis of English Learning Anxiety for Master’s Degree Graduates of Physical Education and Examination Relief Countermeasures —— From the perspective of Weiner’s attribution theory View study ↗

Zhang et al. (2021)

This research uses Weiner's attribution theory to analyse English learning anxiety among physical education graduates. Teachers can apply these findings to identify how students attribute their language learning difficulties, enabling more targeted interventions to reduce anxiety and improve English learning outcomes.

Third Language Learning: Insights from MA Students Through the L2 Motivational Self-System & Attribution Theory Lenses View study ↗

Meccawy et al. (2024)

This qualitative study examines why students discontinue third language learning using attribution theory and motivational frameworks. Teachers can use these insights to understand student attrition in language programmes and develop strategies to maintain student motivation and engagement in multilingual education.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/attribution-theory#article","headline":"Attribution Theory","description":"Explore attribution theory and how it shapes motivation, behaviour and relationships. Learn how attributions impact communication and personal growth.","datePublished":"2023-05-02T18:35:30.094Z","dateModified":"2026-02-09T16:38:47.534Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/attribution-theory"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6952572c5afeea6398543f55_6952572ae33217ec9419553d_attribution-theory-infographic.webp","wordCount":4041},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/attribution-theory#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Attribution Theory","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/attribution-theory"}]}]}