Sociocultural Theory: Vygotsky's Approach to Learning and Development

Explore Vygotsky's sociocultural theory and how social interaction, language, and culture shape cognitive development and transform classroom practice.

Explore Vygotsky's sociocultural theory and how social interaction, language, and culture shape cognitive development and transform classroom practice.

Sociocultural theory, developed by Lev Vygotsky, transformed our understanding of how learning happens. Among education theorists, Vygotsky stands out for his focus on social interaction. Unlike theories that focus on individual cognitive development, sociocultural theory emphasises that learning is fundamentally social: we develop higher mental func tions through interaction with more knowledgeable others and cultural tools, especially language. This perspective has profound implications for classroom practise, highlighting the importance of collaborative learning and representing one of the key sociocultural approaches to learning, dialogue, and the cultural context of education.

According to this perspective, children develop through meaningful dialogue and collaborative activity, especially with more knowledgeable individuals such as parents, teachers, or peers. These interactions help learners build knowledge, language, and problem-solving strategies in real time, often through shared experiences.

Vygotsky emphasised the importance of culture, arguing that every society passes down tools for thinking, such as language, values, and customs, that influence how people learn and behave. This makes learning context-dependent, varying across different cultures and communities.

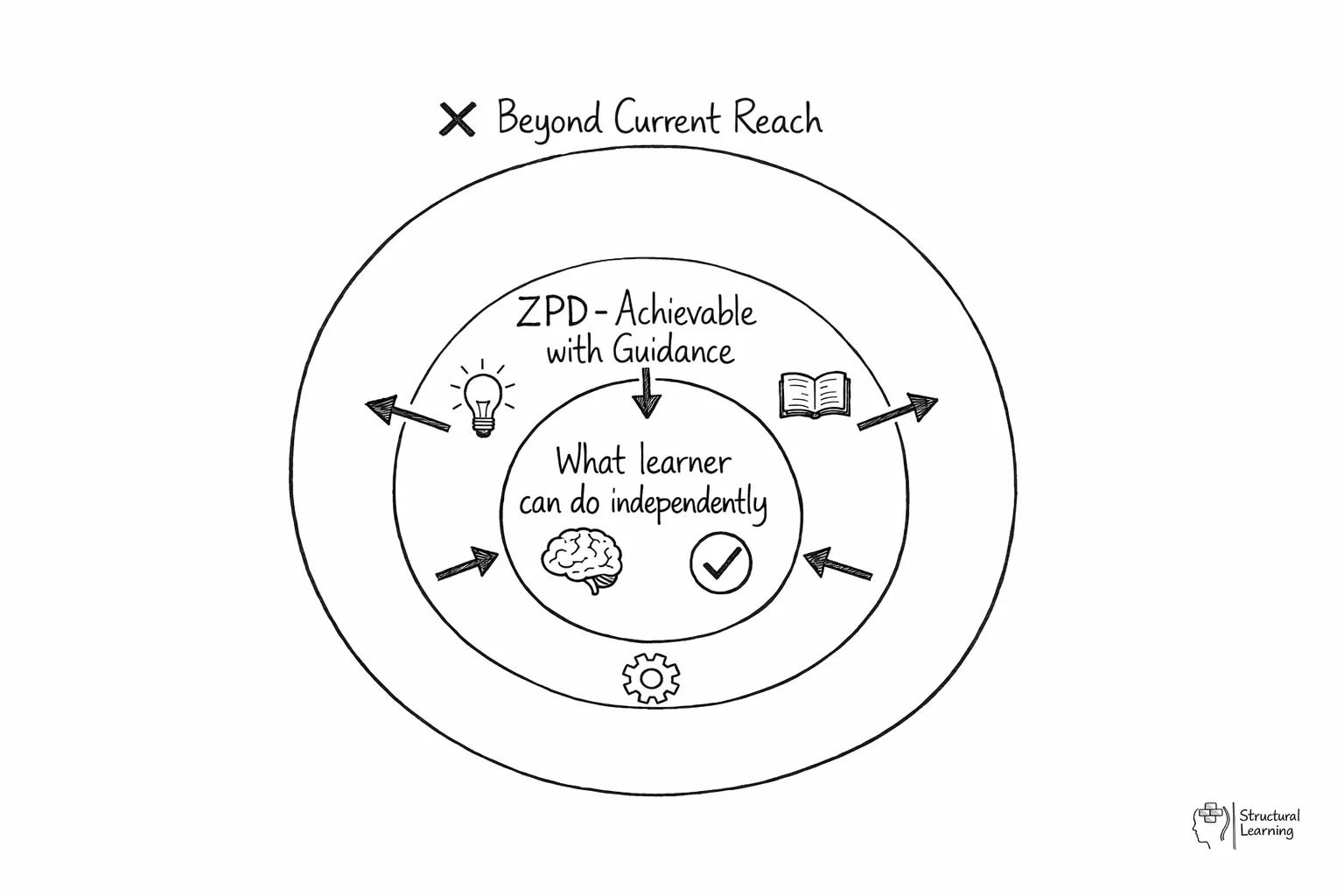

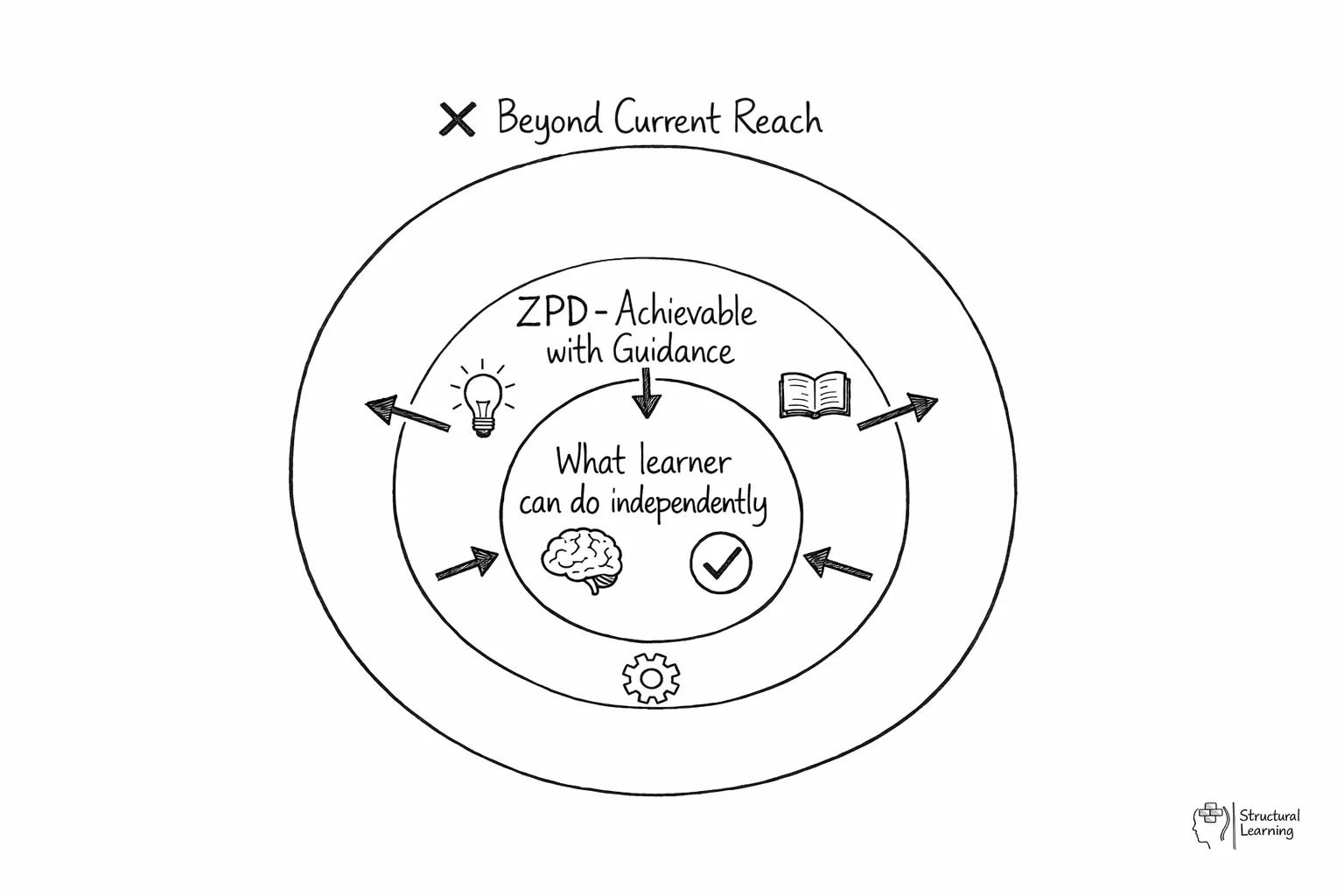

The theory also introduces the concept of the " Zone of Proximal Development ", which refers to the gap between what a learner can do independently and what they can achieve with guidance. By engaging in socially supported activities, learners stretch their abilities and internalize new knowledge.

Sociocultural Theory has wide application in education, early yearssettings, and special educational needs, offering a powerful framework for understanding how relationships, environments, and cultural norms influence the learning process.

| Stage/Level | Age Range | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ZPD Level | Early childhood | Child operates at actual developmental level, performing tasks independently without assistance | Assess baseline abilities, provide age-appropriate independent activities |

| Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) | All ages | Gap between independent performance and potential achievement with guidance from more knowledgeable others | Provide scaffolded support, collaborative learning opportunities, peer tutoring |

| Social Interaction Phase | All ages | Learning occurs through meaningful dialogue and collaborative activities with parents, teachers, or peers | Facilitate group work, encourage discussion, create opportunities for meaningful dialogue |

| Internalization Phase | All ages | After social interaction, learning is integrated at the personal level and becomes part of individual knowledge | Allow time for reflection, provide opportunities to practise independently after guided instruction |

| Cultural Tools Integration | All ages | Use of culture-specific tools like language, note-taking, or memorization techniques to support learning | Incorporate culturally relevant materials, respect diverse learning strategies, teach various cognitive tools using differentiation strategies |

bottom: 56.25%; position: relative; overflow: hidden;">

Central to sociocultural theory is the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which describes the gap between what learners can accomplish on their own and what they can accomplish with guidance. In classroom practise, this translates to teachers providing scaffolded support that gradually diminishes as students gain competence. For instance, during group discussions, educators might initially model questioning techniques before encouraging students to facilitate their own collaborative inquiries.

Cultural tools and language serve as mediating instruments in this learning process. These range from physical resources like graphic organisers and mathematical manipulatives to symbolic systems such as subject-specific terminology and discourse patterns. Educational settings that embrace sociocultural principles deliberately integrate these tools whilst encouraging peer-to-peer interaction, recognising that students often learn effectively from one another's explanations and diverse problem-solving approaches.

Unlike behaviourist or purely cognitive approaches, sociocultural theory views the social environment not merely as a context for learning, but as its fundamental source, making collaborative classroom structures essential rather than optional.

Sociocultural theory offers teachers practical strategies to creates a more engaging and effective learning environment. Here are some actionable methods:

While sociocultural theory provides valuable insights, educators should be mindful of its challenges:

The Zone of Proximal Development represents the dynamic space between what a learner can accomplish without reliance and what they can achieve with guidance from a more knowledgeable other. Vygotsky conceptualised this zone as the optimal learning environment where cognitive development occurs most effectively. Unlike traditional approaches that focus on measuring existing capabilities, ZPD emphasises potential development, recognising that learning precedes and drives development rather than simply following it.

Within the ZPD, social interaction becomes the primary mechanism for learning. Wood, Bruner, and Ross later developed the concept of scaffolding to describe how support is gradually withdrawn as learners gain competence. This temporary assistance might include verbal prompts, visual aids, collaborative problem-solving, or structured activities that bridge the gap between current and potential ability levels.

In classroom practise, identifying each student's ZPD requires careful observation and formative assessment to understand their individual learning trajectories. Teachers can create optimal learning conditions by pairing students strategically, providing differentiated support, and designing tasks that challenge without overwhelming. Group work becomes particularly powerful when learners with complementary strengths collaborate, as peer interaction within the ZPD often proves more effective than traditional teacher-directed instruction for promoting genuine understanding and skill development.

Scaffolding represents the cornerstone of Vygotsky-inspired pedagogy, providing temporary support structures that enable learners to achieve tasks beyond their independent capability. Jerome Bruner, who coined the term, described scaffolding as the process of adjusting support levels based on learners' evolving competence within their zone of proximal development. Effective scaffolding involves three critical phases: demonstrating the task while thinking aloud, providing guided practise with decreasing assistance, and finally withdrawing support as students achieve independence.

Research by Annemarie Palincsar demonstrates that successful scaffolding techniques include strategic questioning, cognitive modelling, and collaborative problem-solving approaches. Teachers must carefully diagnose learners' current understanding to provide appropriately challenging tasks that stretch thinking without overwhelming cognitive capacity. This diagnostic sensitivity ensures that support remains within the zone of proximal development, promoting genuine learning rather than mere task completion.

In classroom practise, scaffolding manifests through varied techniques such as graphic organisers, peer collaboration protocols, and graduated prompting systems. Teachers might begin complex writing tasks with structured templates, gradually removing elements as students internalise the process. Similarly, mathematical problem-solving benefits from worked examples that transition to partially completed problems before students tackle independent challenges. The key lies in systematic withdrawal of support rather than permanent assistance, developing genuine competence development.

Cultural tools represent the mediating instruments through which learners engage with knowledge and develop higher-order thinking skills. Vygotsky emphasised that human learning is fundamentally mediated by these tools, which include language, symbols, diagrams, mathematical notation, and technological resources. Rather than directly encountering raw information, learners interact with content through these cultural mediators, which shape both the learning process and the knowledge constructed. This mediation transforms basic mental functions into sophisticated cognitive abilities, enabling abstract thinking and complex problem-solving.

Language stands as the most powerful cultural tool in educational settings, serving simultaneously as a means of communication and a vehicle for thought development. When teachers model thinking aloud or students engage in collaborative dialogue, language mediates their understanding and facilitates cognitive growth. Similarly, visual tools such as concept maps, diagrams, and graphic organisers provide alternative pathways for knowledge construction, particularly supporting learners who benefit from multimodal approaches.

Effective classroom practise involves deliberately selecting and introducing cultural tools that match learning objectives and student needs. Teachers should model how to use these mediating instruments, gradually transferring responsibility to learners as they develop proficiency. For instance, introducing mathematical representations alongside verbal explanations enables students to access content through multiple channels, whilst collaborative tools like peer discussion protocols help learners internalise new concepts through social interaction before independent application.

Collaborative learning represents one of the most direct applications of Vygotsky's sociocultural theory in educational settings. When students work together on shared tasks, they naturally create zones of proximal development for one another, with more capable peers serving as mediators who scaffold learning through social interaction. Research by Marlene Scardamalia and Carl Bereiter demonstrates that collaborative knowledge building not only enhances individual understanding but also develops students' ability to engage in meaningful dialogue about complex concepts.

Effective implementation requires careful attention to group composition and task design. Heterogeneous groupings typically prove most beneficial, as they provide natural opportunities for peer tutoring whilst ensuring that all students can contribute meaningfully to the collaborative process. The tasks themselves should be sufficiently complex to necessitate genuine collaboration rather than simple task division, encouraging students to engage in what Vygotsky termed "thinking together" through shared cultural tools such as academic language and disciplinary practices.

In practise, teachers can facilitate collaborative learning by establishing clear protocols for group interaction, providing structured roles that rotate amongst group members, and creating opportunities for groups to share their collective thinking with the broader classroom community. This approach transforms the classroom into a genuine community of practise where learning emerges through sustained social interaction rather than isolated individual effort.

For Vygotsky, language represents far more than communication; it serves as the primary tool for organising thought and regulating behaviour. Unlike Piaget, who viewed language as following cognitive development, Vygotsky argued that language actually shapes and drives thinking processes. This perspective transforms how we understand children's self-talk and classroom dialogue.

Vygotsky identified three key stages in language development. First, social speech occurs when children use language purely for communication with others. Next, private speech emerges around ages 3-7, where children talk aloud to themselves whilst solving problems or completing tasks. Finally, this evolves into inner speech, the silent internal dialogue that guides adult thinking. Teachers often observe private speech when pupils work through maths problems, muttering calculations under their breath, or when reception children narrate their play activities.

Understanding these stages offers practical classroom applications. Rather than discouraging self-talk, teachers can recognise it as vital cognitive processing. During problem-solving activities, encourage pupils to 'think aloud' in pairs, making their reasoning visible to partners. This technique, supported by research from Winsler et al. (2009), shows that children who use more private speech demonstrate better task performance and self-regulation.

Teachers can scaffold language development through structured talk activities. The 'Think-Pair-Share' method allows pupils to rehearse ideas privately before sharing, whilst 'Talk Partners' provide regular opportunities for academic dialogue. In Key Stage 1, using sentence stems like 'I noticed that...' or 'This reminds me of...' helps children internalise academic language patterns. These strategies recognise that classroom talk isn't merely sharing ideas; it's actively constructing understanding through language.

Sociocultural theory provides a powerful lens through which to view learning and development, emphasising the critical roles of social interaction, cultural context, and guided support. By integrating Vygotsky's ideas into classroom practise, educators can create dynamic learning environments that helps students to reach their full potential.

Vygotsky’s work provides a framework for understanding how children learn through social interaction and cultural experiences, which offers valuable tools and considerations for educators. Embracing this perspective transforms classrooms into hubs of collaboration, dialogue, and culturally responsive teaching.

Teachers can identify a student's ZPD by observing what they can do independently, then gradually introducing more challenging tasks with support. Use formative assessments, one-to-one questioning, and collaborative activities to see where students struggle without help but succeed with guidance. Regular observation during group work and scaffolded activities reveals the sweet spot between too easy and too difficult.

Effective scaffolding techniques include think-alouds where you verbalise problem-solving steps, providing sentence starters or writing frames, and using visual prompts or graphic organisers. Gradually reduce support by moving from demonstrating, to doing together, to guided practise, and finally independent work. Peer partnerships and strategic grouping also provide natural scaffolding opportunities.

In mixed-ability settings, sociocultural theory supports flexible grouping where more capable students can act as peer tutors for others. This benefits both learners as explaining concepts reinforces understanding for the tutor whilst providing appropriate support for the learner. Use collaborative projects that allow students to contribute at different levels whilst working towards shared goals.

Classroom dialogue is central to sociocultural learning as students develop thinking skills through meaningful conversation. Encourage exploratory talk where students can voice half-formed ideas, ask questions, and build on each other's contributions. Teacher questioning should prompt deeper thinking rather than simply seeking correct answers, creating opportunities for collaborative meaning-making.

Recognise that students bring different cultural tools and ways of knowing to the classroom, which should be valued and incorporated into learning. Use culturally responsive teaching by connecting new concepts to students' home experiences and inviting families to share their expertise. Create opportunities for students to share different perspectives and problem-solving approaches from their cultural backgrounds.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Practical Application of Piaget's Cognitive Theory and Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory in Classroom Pedagogy View study ↗

4 citations

Michael Kwarteng (2025)

This study examines how teachers can effectively combine Piaget's developmental stages with Vygotsky's social learning principles in their daily instruction. The research shows that when teachers align their classroom environment and teaching strategies with both theories, students demonstrate improved understanding and motivation. This practical guide helps educators bridge the gap between educational theory and real classroom application.

Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory: Raising Reading Comprehension in Elementary Learners through the ARAL Programme and Its Implications for Administration and Governance in Contemporary Education View study ↗

Lovelle M. Arguido, MAEd et al. (2025)

This research demonstrates how Vygotsky's emphasis on social interaction and collaborative learning significantly improved reading comprehension among elementary students in Philippine schools recovering from pandemic learning losses. The study provides concrete evidence that structured peer interaction and community-based learning approaches can help young readers catch up after educational disruptions. Elementary teachers will find valuable strategies for creating supportive reading environments that use social learning.

Revisiting the Significance of ZDP and Scaffolding in English Language Teaching View study ↗

11 citations

Muntasir Muntasir & Indra Akbar (2023)

This comprehensive review clarifies how the Zone of Proximal Development and scaffolding techniques can transform English language instruction by meeting students exactly where they are in their learning process. The authors provide practical guidance for structuring curriculum materials and teaching approaches that gradually build student independence while maintaining appropriate support. English teachers will discover how to identify the sweet spot between too easy and too difficult when designing lessons and activities.

Applying the Concepts of "Community" and "Social Interaction" from Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development in Math Teaching to Develop Learner's Math Communication Competencies View study ↗

11 citations

P. Luong (2022)

This study reveals how creating a classroom community focused on mathematical discussion and peer interaction significantly improves students' ability to communicate mathematical ideas clearly. The research shows that when high school math teachers prioritize student-to-student dialogue and collaborative problem-solving, students develop stronger reasoning skills alongside computational abilities. Math educators will learn specific techniques for building mathematical conversations that deepen understanding.

Is There a Teacher in This Classroom? Rethinking Second Language Instruction in a Low-Tech Environment View study ↗

Anahit Hakoupian, Ph.D. (2025)

Drawing on three decades of teaching experience, this educator argues that human connection and spontaneous interaction are irreplaceable elements in second language learning that technology cannot replicate. The article demonstrates how teacher-centred, relationship-based instruction creates authentic communication opportunities that digital tools often miss. Language teachers seeking to balance technology use with meaningful human interaction will find compelling reasons to prioritize face-to-face engagement in their classrooms.

Sociocultural theory, developed by Lev Vygotsky, transformed our understanding of how learning happens. Among education theorists, Vygotsky stands out for his focus on social interaction. Unlike theories that focus on individual cognitive development, sociocultural theory emphasises that learning is fundamentally social: we develop higher mental func tions through interaction with more knowledgeable others and cultural tools, especially language. This perspective has profound implications for classroom practise, highlighting the importance of collaborative learning and representing one of the key sociocultural approaches to learning, dialogue, and the cultural context of education.

According to this perspective, children develop through meaningful dialogue and collaborative activity, especially with more knowledgeable individuals such as parents, teachers, or peers. These interactions help learners build knowledge, language, and problem-solving strategies in real time, often through shared experiences.

Vygotsky emphasised the importance of culture, arguing that every society passes down tools for thinking, such as language, values, and customs, that influence how people learn and behave. This makes learning context-dependent, varying across different cultures and communities.

The theory also introduces the concept of the " Zone of Proximal Development ", which refers to the gap between what a learner can do independently and what they can achieve with guidance. By engaging in socially supported activities, learners stretch their abilities and internalize new knowledge.

Sociocultural Theory has wide application in education, early yearssettings, and special educational needs, offering a powerful framework for understanding how relationships, environments, and cultural norms influence the learning process.

| Stage/Level | Age Range | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ZPD Level | Early childhood | Child operates at actual developmental level, performing tasks independently without assistance | Assess baseline abilities, provide age-appropriate independent activities |

| Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) | All ages | Gap between independent performance and potential achievement with guidance from more knowledgeable others | Provide scaffolded support, collaborative learning opportunities, peer tutoring |

| Social Interaction Phase | All ages | Learning occurs through meaningful dialogue and collaborative activities with parents, teachers, or peers | Facilitate group work, encourage discussion, create opportunities for meaningful dialogue |

| Internalization Phase | All ages | After social interaction, learning is integrated at the personal level and becomes part of individual knowledge | Allow time for reflection, provide opportunities to practise independently after guided instruction |

| Cultural Tools Integration | All ages | Use of culture-specific tools like language, note-taking, or memorization techniques to support learning | Incorporate culturally relevant materials, respect diverse learning strategies, teach various cognitive tools using differentiation strategies |

bottom: 56.25%; position: relative; overflow: hidden;">

Central to sociocultural theory is the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which describes the gap between what learners can accomplish on their own and what they can accomplish with guidance. In classroom practise, this translates to teachers providing scaffolded support that gradually diminishes as students gain competence. For instance, during group discussions, educators might initially model questioning techniques before encouraging students to facilitate their own collaborative inquiries.

Cultural tools and language serve as mediating instruments in this learning process. These range from physical resources like graphic organisers and mathematical manipulatives to symbolic systems such as subject-specific terminology and discourse patterns. Educational settings that embrace sociocultural principles deliberately integrate these tools whilst encouraging peer-to-peer interaction, recognising that students often learn effectively from one another's explanations and diverse problem-solving approaches.

Unlike behaviourist or purely cognitive approaches, sociocultural theory views the social environment not merely as a context for learning, but as its fundamental source, making collaborative classroom structures essential rather than optional.

Sociocultural theory offers teachers practical strategies to creates a more engaging and effective learning environment. Here are some actionable methods:

While sociocultural theory provides valuable insights, educators should be mindful of its challenges:

The Zone of Proximal Development represents the dynamic space between what a learner can accomplish without reliance and what they can achieve with guidance from a more knowledgeable other. Vygotsky conceptualised this zone as the optimal learning environment where cognitive development occurs most effectively. Unlike traditional approaches that focus on measuring existing capabilities, ZPD emphasises potential development, recognising that learning precedes and drives development rather than simply following it.

Within the ZPD, social interaction becomes the primary mechanism for learning. Wood, Bruner, and Ross later developed the concept of scaffolding to describe how support is gradually withdrawn as learners gain competence. This temporary assistance might include verbal prompts, visual aids, collaborative problem-solving, or structured activities that bridge the gap between current and potential ability levels.

In classroom practise, identifying each student's ZPD requires careful observation and formative assessment to understand their individual learning trajectories. Teachers can create optimal learning conditions by pairing students strategically, providing differentiated support, and designing tasks that challenge without overwhelming. Group work becomes particularly powerful when learners with complementary strengths collaborate, as peer interaction within the ZPD often proves more effective than traditional teacher-directed instruction for promoting genuine understanding and skill development.

Scaffolding represents the cornerstone of Vygotsky-inspired pedagogy, providing temporary support structures that enable learners to achieve tasks beyond their independent capability. Jerome Bruner, who coined the term, described scaffolding as the process of adjusting support levels based on learners' evolving competence within their zone of proximal development. Effective scaffolding involves three critical phases: demonstrating the task while thinking aloud, providing guided practise with decreasing assistance, and finally withdrawing support as students achieve independence.

Research by Annemarie Palincsar demonstrates that successful scaffolding techniques include strategic questioning, cognitive modelling, and collaborative problem-solving approaches. Teachers must carefully diagnose learners' current understanding to provide appropriately challenging tasks that stretch thinking without overwhelming cognitive capacity. This diagnostic sensitivity ensures that support remains within the zone of proximal development, promoting genuine learning rather than mere task completion.

In classroom practise, scaffolding manifests through varied techniques such as graphic organisers, peer collaboration protocols, and graduated prompting systems. Teachers might begin complex writing tasks with structured templates, gradually removing elements as students internalise the process. Similarly, mathematical problem-solving benefits from worked examples that transition to partially completed problems before students tackle independent challenges. The key lies in systematic withdrawal of support rather than permanent assistance, developing genuine competence development.

Cultural tools represent the mediating instruments through which learners engage with knowledge and develop higher-order thinking skills. Vygotsky emphasised that human learning is fundamentally mediated by these tools, which include language, symbols, diagrams, mathematical notation, and technological resources. Rather than directly encountering raw information, learners interact with content through these cultural mediators, which shape both the learning process and the knowledge constructed. This mediation transforms basic mental functions into sophisticated cognitive abilities, enabling abstract thinking and complex problem-solving.

Language stands as the most powerful cultural tool in educational settings, serving simultaneously as a means of communication and a vehicle for thought development. When teachers model thinking aloud or students engage in collaborative dialogue, language mediates their understanding and facilitates cognitive growth. Similarly, visual tools such as concept maps, diagrams, and graphic organisers provide alternative pathways for knowledge construction, particularly supporting learners who benefit from multimodal approaches.

Effective classroom practise involves deliberately selecting and introducing cultural tools that match learning objectives and student needs. Teachers should model how to use these mediating instruments, gradually transferring responsibility to learners as they develop proficiency. For instance, introducing mathematical representations alongside verbal explanations enables students to access content through multiple channels, whilst collaborative tools like peer discussion protocols help learners internalise new concepts through social interaction before independent application.

Collaborative learning represents one of the most direct applications of Vygotsky's sociocultural theory in educational settings. When students work together on shared tasks, they naturally create zones of proximal development for one another, with more capable peers serving as mediators who scaffold learning through social interaction. Research by Marlene Scardamalia and Carl Bereiter demonstrates that collaborative knowledge building not only enhances individual understanding but also develops students' ability to engage in meaningful dialogue about complex concepts.

Effective implementation requires careful attention to group composition and task design. Heterogeneous groupings typically prove most beneficial, as they provide natural opportunities for peer tutoring whilst ensuring that all students can contribute meaningfully to the collaborative process. The tasks themselves should be sufficiently complex to necessitate genuine collaboration rather than simple task division, encouraging students to engage in what Vygotsky termed "thinking together" through shared cultural tools such as academic language and disciplinary practices.

In practise, teachers can facilitate collaborative learning by establishing clear protocols for group interaction, providing structured roles that rotate amongst group members, and creating opportunities for groups to share their collective thinking with the broader classroom community. This approach transforms the classroom into a genuine community of practise where learning emerges through sustained social interaction rather than isolated individual effort.

For Vygotsky, language represents far more than communication; it serves as the primary tool for organising thought and regulating behaviour. Unlike Piaget, who viewed language as following cognitive development, Vygotsky argued that language actually shapes and drives thinking processes. This perspective transforms how we understand children's self-talk and classroom dialogue.

Vygotsky identified three key stages in language development. First, social speech occurs when children use language purely for communication with others. Next, private speech emerges around ages 3-7, where children talk aloud to themselves whilst solving problems or completing tasks. Finally, this evolves into inner speech, the silent internal dialogue that guides adult thinking. Teachers often observe private speech when pupils work through maths problems, muttering calculations under their breath, or when reception children narrate their play activities.

Understanding these stages offers practical classroom applications. Rather than discouraging self-talk, teachers can recognise it as vital cognitive processing. During problem-solving activities, encourage pupils to 'think aloud' in pairs, making their reasoning visible to partners. This technique, supported by research from Winsler et al. (2009), shows that children who use more private speech demonstrate better task performance and self-regulation.

Teachers can scaffold language development through structured talk activities. The 'Think-Pair-Share' method allows pupils to rehearse ideas privately before sharing, whilst 'Talk Partners' provide regular opportunities for academic dialogue. In Key Stage 1, using sentence stems like 'I noticed that...' or 'This reminds me of...' helps children internalise academic language patterns. These strategies recognise that classroom talk isn't merely sharing ideas; it's actively constructing understanding through language.

Sociocultural theory provides a powerful lens through which to view learning and development, emphasising the critical roles of social interaction, cultural context, and guided support. By integrating Vygotsky's ideas into classroom practise, educators can create dynamic learning environments that helps students to reach their full potential.

Vygotsky’s work provides a framework for understanding how children learn through social interaction and cultural experiences, which offers valuable tools and considerations for educators. Embracing this perspective transforms classrooms into hubs of collaboration, dialogue, and culturally responsive teaching.

Teachers can identify a student's ZPD by observing what they can do independently, then gradually introducing more challenging tasks with support. Use formative assessments, one-to-one questioning, and collaborative activities to see where students struggle without help but succeed with guidance. Regular observation during group work and scaffolded activities reveals the sweet spot between too easy and too difficult.

Effective scaffolding techniques include think-alouds where you verbalise problem-solving steps, providing sentence starters or writing frames, and using visual prompts or graphic organisers. Gradually reduce support by moving from demonstrating, to doing together, to guided practise, and finally independent work. Peer partnerships and strategic grouping also provide natural scaffolding opportunities.

In mixed-ability settings, sociocultural theory supports flexible grouping where more capable students can act as peer tutors for others. This benefits both learners as explaining concepts reinforces understanding for the tutor whilst providing appropriate support for the learner. Use collaborative projects that allow students to contribute at different levels whilst working towards shared goals.

Classroom dialogue is central to sociocultural learning as students develop thinking skills through meaningful conversation. Encourage exploratory talk where students can voice half-formed ideas, ask questions, and build on each other's contributions. Teacher questioning should prompt deeper thinking rather than simply seeking correct answers, creating opportunities for collaborative meaning-making.

Recognise that students bring different cultural tools and ways of knowing to the classroom, which should be valued and incorporated into learning. Use culturally responsive teaching by connecting new concepts to students' home experiences and inviting families to share their expertise. Create opportunities for students to share different perspectives and problem-solving approaches from their cultural backgrounds.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Practical Application of Piaget's Cognitive Theory and Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory in Classroom Pedagogy View study ↗

4 citations

Michael Kwarteng (2025)

This study examines how teachers can effectively combine Piaget's developmental stages with Vygotsky's social learning principles in their daily instruction. The research shows that when teachers align their classroom environment and teaching strategies with both theories, students demonstrate improved understanding and motivation. This practical guide helps educators bridge the gap between educational theory and real classroom application.

Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory: Raising Reading Comprehension in Elementary Learners through the ARAL Programme and Its Implications for Administration and Governance in Contemporary Education View study ↗

Lovelle M. Arguido, MAEd et al. (2025)

This research demonstrates how Vygotsky's emphasis on social interaction and collaborative learning significantly improved reading comprehension among elementary students in Philippine schools recovering from pandemic learning losses. The study provides concrete evidence that structured peer interaction and community-based learning approaches can help young readers catch up after educational disruptions. Elementary teachers will find valuable strategies for creating supportive reading environments that use social learning.

Revisiting the Significance of ZDP and Scaffolding in English Language Teaching View study ↗

11 citations

Muntasir Muntasir & Indra Akbar (2023)

This comprehensive review clarifies how the Zone of Proximal Development and scaffolding techniques can transform English language instruction by meeting students exactly where they are in their learning process. The authors provide practical guidance for structuring curriculum materials and teaching approaches that gradually build student independence while maintaining appropriate support. English teachers will discover how to identify the sweet spot between too easy and too difficult when designing lessons and activities.

Applying the Concepts of "Community" and "Social Interaction" from Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development in Math Teaching to Develop Learner's Math Communication Competencies View study ↗

11 citations

P. Luong (2022)

This study reveals how creating a classroom community focused on mathematical discussion and peer interaction significantly improves students' ability to communicate mathematical ideas clearly. The research shows that when high school math teachers prioritize student-to-student dialogue and collaborative problem-solving, students develop stronger reasoning skills alongside computational abilities. Math educators will learn specific techniques for building mathematical conversations that deepen understanding.

Is There a Teacher in This Classroom? Rethinking Second Language Instruction in a Low-Tech Environment View study ↗

Anahit Hakoupian, Ph.D. (2025)

Drawing on three decades of teaching experience, this educator argues that human connection and spontaneous interaction are irreplaceable elements in second language learning that technology cannot replicate. The article demonstrates how teacher-centred, relationship-based instruction creates authentic communication opportunities that digital tools often miss. Language teachers seeking to balance technology use with meaningful human interaction will find compelling reasons to prioritize face-to-face engagement in their classrooms.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/sociocultural-theory#article","headline":"Sociocultural Theory: Vygotsky's Approach to Learning and Development","description":"Explore Vygotsky's sociocultural theory and how social interaction, language, and culture shape cognitive development and transform classroom practice.","datePublished":"2023-03-06T18:08:44.767Z","dateModified":"2026-02-12T10:27:02.026Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/sociocultural-theory"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69525be343ac9a07f311baca_69525be0614bbe7fdd516af1_sociocultural-theory-infographic.webp","wordCount":2936},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/sociocultural-theory#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Sociocultural Theory: Vygotsky's Approach to Learning and Development","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/sociocultural-theory"}]}]}