Inquiry-Based Learning: A Complete Guide for Teachers

Explore practical strategies for implementing inquiry-based learning, designing effective inquiries, and fostering genuine curiosity in your students.

Explore practical strategies for implementing inquiry-based learning, designing effective inquiries, and fostering genuine curiosity in your students.

Inquiry-based learning is a process of learning that engages learners by creating real-world connections through high-level questioning and exploration. The inquiry-based learning approach encourages learners to engage in experiential learning and problem-based learning.

Inquiry-based learning is about triggering curiosity in students and initiating a student's curiosity achieves far more complex goalsthan information delivery. Despite its complex nature, inquiry-based learning is considered easier for teachers because it does not only shift responsibility from the educators to students, but also it is engaging for students.

Inquiry-based learning is important for creating excitement in students. It motivates students to become specialists of their learning process. However, this type of learning requires a certain level of independent learning skills. Children need to have developed the information-processing skills needed for working with minimal guidance. This guide will argue that there is a place for this type of learning but it does need to be supported with appropriate teacher training and balanced with more traditional curriculum delivery.

Inquiry-based learning puts the student at the center of the learning process. Instead of simply absorbing information, students are encouraged to explore and discover knowledge on their own. This approach allows students to develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills, as well as a deeper understanding of the subject matter. The learning process becomes more engaging and meaningful, as students take ownership of their education and develop a sense of curiosity and wonder. However, remember that inquiry-based learning is just one approach to education and should be balanced with other teaching methods to ensure a well-rounded education.

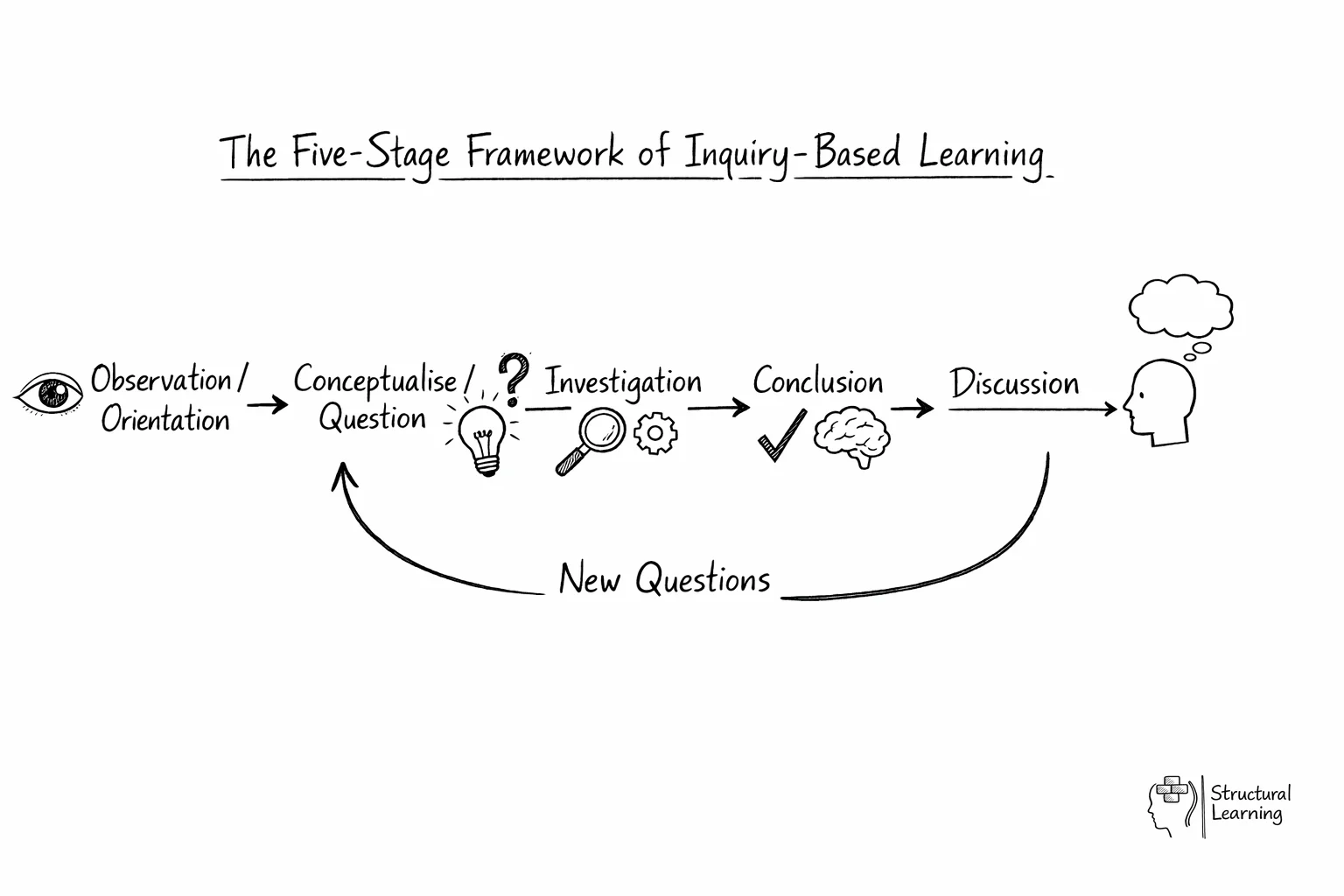

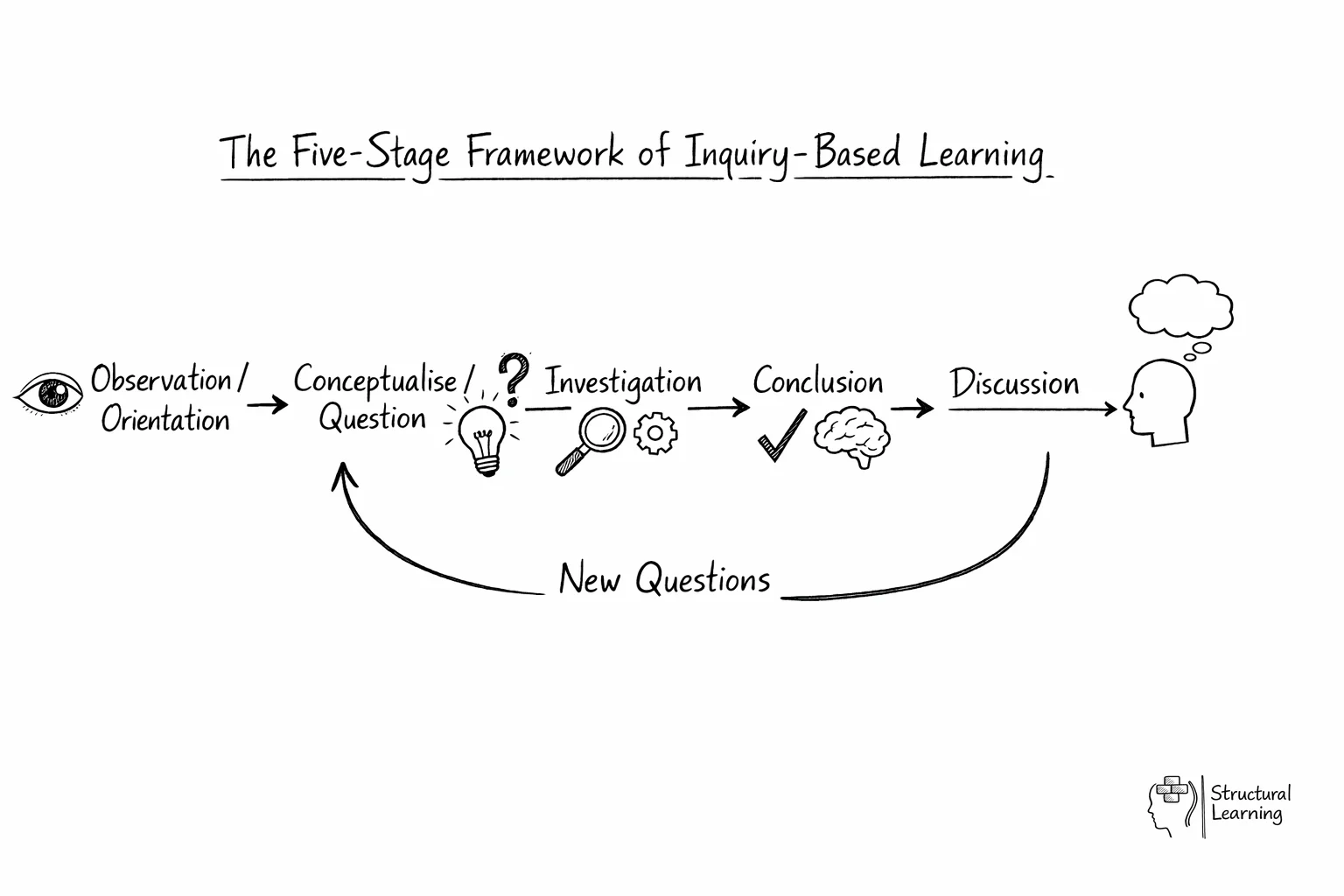

| Stage | Student Actions | Teacher Role | Key Questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Wonder/Question | Generate questions from curiosity and observations | Provoke curiosity; model questioning | What do I wonder about? What don't I understand? |

| 2. Investigate/Explore | Gather information, conduct experiments, collect data | Provide resources; teach research skills | How can I find out? What evidence do I need? |

| 3. Create/Synthesise | Analyse findings, draw conclusions, build understanding | Prompt deeper thinking; challenge assumptions | What does this mean? How does it fit together? |

| 4. Discuss/Share | Present findings, explain reasoning, engage with others | Facilitate discussion; connect ideas | How can I explain this? What do others think? |

| 5. Reflect/Refine | Evaluate learning process, identify gaps, generate new questions | Prompt metacognition; launch next inquiry | What worked well? What new questions do I have? |

Based on inquiry models from Dewey (1910) and the 5E Model (Bybee, 1997).

Teachers can apply inquiry-based instruction in many ways, but some of its basic components include:

The inquiry-based structure of learning has a lot of flexibility. Teachers frequently begin from inquiry-based science lessons, but the inquiry-based learning IB methodology can be implemented into student learning to any lesson and subject. These transferable skills can be used to help pupils become more effective learners in the long run. In higher education, students are required to manage their own time and do their own research. This approach to teaching is a way of building thinking skills for the long term.

In a world history class, the COVID-19 pandemic can be used to compare, study and examine the history of pandemics. A group inquiry lesson may have the following components:

Through this inquiry-based learning activity, students actively engage with historical material, develop research and presentation skills, and improve their understanding of global health issues.

These practical IBL strategies help teachers create environments where curiosity drives learning.

While inquiry-based learning offers numerous benefits, it also presents several challenges for educators. One significant obstacle is the time and effort required to plan and implement inquiry-based activities. Teachers need to carefully design open-ended questions, gather resources, and provide ongoing support to students as they navigate their investigations. This can be particularly demanding for teachers who are accustomed to more traditional, teacher-centred approaches.

Another challenge is the potential for uneven student engagement. In inquiry-based learning, students have a greater degree of autonomy, which can lead to some students feeling overwhelmed or disengaged. For teachers to provide appropriate scaffolding and support to ensure that all students are able to participate meaningfully in the inqu iry process. This may involve breaking down complex tasks into smaller, more manageable steps, providing regular feedback, and offering opportunities for students to collaborate and learn from one another.

Assessment can also be a challenge in inquiry-based learning. Traditional assessment methods, such as standardised tests, may not accurately capture the depth of understanding and skills that students develop through inquiry-based activities. Teachers need to use a variety of assessment strategies, such as observations, portfolios, and student presentations, to evaluate student learning and provide meaningful feedback. It is also important to involve students in the assessment process, encouraging them to reflect on their own learning and identify areas for improvement.

Inquiry-based learning transforms students from passive recipients of information into active investigators, developing deep conceptual understanding that extends far beyond traditional memorisation. Research by Jerome Bruner demonstrates that when students construct knowledge through guided discovery, they develop stronger neural pathways and retain information significantly longer than through direct instruction alone. This student-centred approach naturally cultivates critical thinking skills as learners formulate hypotheses, analyse evidence, and draw conclusions from their investigations.

The collaborative nature of inquiry-based learning develops essential 21st-century skills including communication, teamwork, and digital literacy. Students learn to articulate their thinking, challenge assumptions respectfully, and synthesise multiple perspectives to reach informed conclusions. John Dewey's experiential learning theory supports this approach, showing that authentic learning experiences create stronger motivation and engagement than abstract theoretical content.

In practice, teachers observe increased student ownership of learning as pupils become genuinely curious about outcomes rather than simply completing tasks for grades. This intrinsic motivation leads to sustained engagement and willingness to persevere through challenging problems. The scaffolding inherent in well-designed inquiry activities ensures that students of varying abilities can access learning at appropriate levels whilst developing independence and confidence in their analytical capabilities.

Inquiry-based learning exists along a continuum of teacher guidance, with four primary models offering different levels of student autonomy. Structured inquiry provides students with a specific question and procedure, allowing them to focus on developing investigation skills whilst ensuring meaningful outcomes. Guided inquiry offers more freedom by presenting the research question but leaving methodology choices to learners, whilst open inquiry represents the most student-centred approach, where pupils generate their own questions and design complete investigations.

The choice between these models depends critically on your students' prior knowledge and inquiry experience. Kirschner and Sweller's research on cognitive load theory demonstrates that novice learners benefit significantly from structured approa ches that provide clear scaffolding, whilst more experienced students thrive with greater independence. Confirmation inquiry, though sometimes overlooked, serves as an excellent starting point for younger pupils or those new to investigative learning, as they follow established procedures to verify known results.

Successful implementation requires matching the inquiry type to both learning objectives and student readiness. Begin with structured approaches to build confidence and procedural knowledge, then gradually reduce scaffolding as pupils develop critical thinking skills. Consider hybrid models that combine elements, such as providing a research question but allowing methodological choice, to create authentic learning experiences whilst maintaining appropriate support for your specific classroom context.

Successfully implementing inquiry-based learning requires a gradual shift from teacher-centred to student-centred instruction, beginning with structured inquiry before progressing to open-ended investigations. Start by introducing essential questions that connect to your curriculum objectives, ensuring these questions are authentic and meaningful to students' lives. John Dewey's research on experiential learning demonstrates that students engage more deeply when they can relate new knowledge to their existing experiences and interests.

Effective scaffolding remains crucial throughout the implementation process, as John Sweller's cognitive load theory shows that students can become overwhelmed without proper support structures. Begin each inquiry cycle with clear learning intentions and success criteria, then provide thinking frameworks, research templates, and reflection prompts to guide student exploration. Gradually remove these supports as students develop confidence in their inquiry skills, whilst maintaining regular check-ins to monitor progress and provide targeted feedback.

Transform your classroom environment to support collaborative investigation by creating flexible learning spaces and establishing clear protocols for group work and resource sharing. Build in regular opportunities for students to present findings, debate conclusions, and reflect on their learning processes. This approach develops critical thinking skills whilst ensuring evidence-based reasoning becomes second nature to your students.

Assessment in inquiry-based learning requires a fundamental shift from traditional testing towards authentic, process-focused evaluation that captures both student thinking and learning outcomes. Rather than relying solely on end-of-unit examinations, effective assessment strategies must document the journey of discovery, including hypothesis formation, evidence gathering, and reflection processes that define genuine inquiry.

Formative assessment techniques such as learning journals, peer feedback sessions, and teacher obser vation protocols provide rich evidence of student progress throughout the inquiry cycle. As Dylan Wiliam's research demonstrates, frequent formative feedback significantly enhances student achievement when it focuses on specific learning goals and next steps. Portfolio-based assessment allows students to curate their learning journey, showcasing initial questions, research findings, revised thinking, and final conclusions whilst developing crucial self-evaluation skills.

Practical classroom implementation might include structured reflection templates that prompt students to articulate their thinking processes, collaborative assessment rubrics co-created with students, and regular conferencing sessions where teachers guide students through self-assessment. These approaches honour the student-centred nature of inquiry whilst providing teachers with comprehensive evidence of critical thinking development and conceptual understanding that traditional assessments often miss.

Inquiry-based learning transforms differently across curriculum areas, yet the underlying principles of student-centred investigation remain constant. In science, students might explore "Why do some materials float whilst others sink?" through hands-on experimentation, moving beyond memorising density facts to developing genuine scientific reasoning. History lessons become detective work when pupils investigate "What really happened during the Great Fire of London?" using primary sources, maps, and contemporary accounts to construct evidence-based narratives.

Mathematics inquiry shifts from procedural practice to genuine problem-solving. Rather than teaching fraction algorithms directly, teachers might present real-world scenarios: "How can we fairly share three pizzas among four friends?" This approach, supported by Jo Boaler's research on mathematical mindsets, encourages students to discover multiple solution pathways whilst developing deeper conceptual understanding. Similarly, English literature transforms when students investigate character motivations through textual evidence rather than accepting teacher interpretations.

Effective cross-curricular implementation requires careful scaffolding to prevent cognitive overload. Begin with structured inquiries providing clear frameworks, gradually releasing responsibility as students develop investigation skills. Consider your subject's unique demands: science requires hypothesis formation, history demands source evaluation, whilst mathematics needs pattern recognition. This differentiated approach ensures authentic learning experiences whilst maintaining rigorous academic standards across all disciplines.

Effective inquiry-based lesson planning begins with crafting a compelling question that genuinely puzzles students and connects to their lived experiences. Your central inquiry should be open-ended enough to allow multiple pathways of investigation whilst remaining focused on specific learning objectives. Consider John Dewey's emphasis on authentic problems: the most powerful inquiries emerge from real-world dilemmas that students can meaningfully explore through available resources and evidence.

Structure your lessons using a gradual release framework that balances cognitive load with student agency. Begin with shared investigation where you model inquiry processes, then transition to guided practice where small groups tackle related sub-questions with scaffolding. Jerome Bruner's spiral curriculum theory supports this approach, as students build investigative confidence through repeated exposure to inquiry methods across different contexts. Plan specific checkpoints where students can share emerging theories and receive feedback before proceeding independently.

Design flexible assessment opportunities that capture both content learning and inquiry skills development. Rather than traditional end-of-unit tests, consider evidence portfolios where students document their investigation process, peer evaluation of research methods, or presentation formats that mirror authentic professional practices. This approach honours the student-centred nature of inquiry whilst providing you with rich data about both conceptual understanding and critical thinking development.

inquiry-based learning represents a powerful approach to education that can creates critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and a lifelong love of learning. By shifting the focus from rote memorisation to active exploration and discovery, inquiry-based learning helps students to become active participants in their own education. While it presents challenges, these can be overcome with careful planning, appropriate support, and a willingness to embrace new approaches to teaching and assessment.

Ultimately, the goal of education is to prepare students for success in a rapidly changing world. Inquiry-based learning provides students with the skills and knowledge they need to thrive in the 21st century, developing creativity, collaboration, and a deep understanding of the world around them. By embracing inquiry-based learning, educators can helps students to become lifelong learners and active, engaged citizens.

Inquiry-based learning research

Discovery learning meta-analysis

For those who wish to examine deeper into the theory and practice of inquiry-based learning, the following research papers offer valuable insights:

Inquiry-based learning is a process of learning that engages learners by creating real-world connections through high-level questioning and exploration. The inquiry-based learning approach encourages learners to engage in experiential learning and problem-based learning.

Inquiry-based learning is about triggering curiosity in students and initiating a student's curiosity achieves far more complex goalsthan information delivery. Despite its complex nature, inquiry-based learning is considered easier for teachers because it does not only shift responsibility from the educators to students, but also it is engaging for students.

Inquiry-based learning is important for creating excitement in students. It motivates students to become specialists of their learning process. However, this type of learning requires a certain level of independent learning skills. Children need to have developed the information-processing skills needed for working with minimal guidance. This guide will argue that there is a place for this type of learning but it does need to be supported with appropriate teacher training and balanced with more traditional curriculum delivery.

Inquiry-based learning puts the student at the center of the learning process. Instead of simply absorbing information, students are encouraged to explore and discover knowledge on their own. This approach allows students to develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills, as well as a deeper understanding of the subject matter. The learning process becomes more engaging and meaningful, as students take ownership of their education and develop a sense of curiosity and wonder. However, remember that inquiry-based learning is just one approach to education and should be balanced with other teaching methods to ensure a well-rounded education.

| Stage | Student Actions | Teacher Role | Key Questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Wonder/Question | Generate questions from curiosity and observations | Provoke curiosity; model questioning | What do I wonder about? What don't I understand? |

| 2. Investigate/Explore | Gather information, conduct experiments, collect data | Provide resources; teach research skills | How can I find out? What evidence do I need? |

| 3. Create/Synthesise | Analyse findings, draw conclusions, build understanding | Prompt deeper thinking; challenge assumptions | What does this mean? How does it fit together? |

| 4. Discuss/Share | Present findings, explain reasoning, engage with others | Facilitate discussion; connect ideas | How can I explain this? What do others think? |

| 5. Reflect/Refine | Evaluate learning process, identify gaps, generate new questions | Prompt metacognition; launch next inquiry | What worked well? What new questions do I have? |

Based on inquiry models from Dewey (1910) and the 5E Model (Bybee, 1997).

Teachers can apply inquiry-based instruction in many ways, but some of its basic components include:

The inquiry-based structure of learning has a lot of flexibility. Teachers frequently begin from inquiry-based science lessons, but the inquiry-based learning IB methodology can be implemented into student learning to any lesson and subject. These transferable skills can be used to help pupils become more effective learners in the long run. In higher education, students are required to manage their own time and do their own research. This approach to teaching is a way of building thinking skills for the long term.

In a world history class, the COVID-19 pandemic can be used to compare, study and examine the history of pandemics. A group inquiry lesson may have the following components:

Through this inquiry-based learning activity, students actively engage with historical material, develop research and presentation skills, and improve their understanding of global health issues.

These practical IBL strategies help teachers create environments where curiosity drives learning.

While inquiry-based learning offers numerous benefits, it also presents several challenges for educators. One significant obstacle is the time and effort required to plan and implement inquiry-based activities. Teachers need to carefully design open-ended questions, gather resources, and provide ongoing support to students as they navigate their investigations. This can be particularly demanding for teachers who are accustomed to more traditional, teacher-centred approaches.

Another challenge is the potential for uneven student engagement. In inquiry-based learning, students have a greater degree of autonomy, which can lead to some students feeling overwhelmed or disengaged. For teachers to provide appropriate scaffolding and support to ensure that all students are able to participate meaningfully in the inqu iry process. This may involve breaking down complex tasks into smaller, more manageable steps, providing regular feedback, and offering opportunities for students to collaborate and learn from one another.

Assessment can also be a challenge in inquiry-based learning. Traditional assessment methods, such as standardised tests, may not accurately capture the depth of understanding and skills that students develop through inquiry-based activities. Teachers need to use a variety of assessment strategies, such as observations, portfolios, and student presentations, to evaluate student learning and provide meaningful feedback. It is also important to involve students in the assessment process, encouraging them to reflect on their own learning and identify areas for improvement.

Inquiry-based learning transforms students from passive recipients of information into active investigators, developing deep conceptual understanding that extends far beyond traditional memorisation. Research by Jerome Bruner demonstrates that when students construct knowledge through guided discovery, they develop stronger neural pathways and retain information significantly longer than through direct instruction alone. This student-centred approach naturally cultivates critical thinking skills as learners formulate hypotheses, analyse evidence, and draw conclusions from their investigations.

The collaborative nature of inquiry-based learning develops essential 21st-century skills including communication, teamwork, and digital literacy. Students learn to articulate their thinking, challenge assumptions respectfully, and synthesise multiple perspectives to reach informed conclusions. John Dewey's experiential learning theory supports this approach, showing that authentic learning experiences create stronger motivation and engagement than abstract theoretical content.

In practice, teachers observe increased student ownership of learning as pupils become genuinely curious about outcomes rather than simply completing tasks for grades. This intrinsic motivation leads to sustained engagement and willingness to persevere through challenging problems. The scaffolding inherent in well-designed inquiry activities ensures that students of varying abilities can access learning at appropriate levels whilst developing independence and confidence in their analytical capabilities.

Inquiry-based learning exists along a continuum of teacher guidance, with four primary models offering different levels of student autonomy. Structured inquiry provides students with a specific question and procedure, allowing them to focus on developing investigation skills whilst ensuring meaningful outcomes. Guided inquiry offers more freedom by presenting the research question but leaving methodology choices to learners, whilst open inquiry represents the most student-centred approach, where pupils generate their own questions and design complete investigations.

The choice between these models depends critically on your students' prior knowledge and inquiry experience. Kirschner and Sweller's research on cognitive load theory demonstrates that novice learners benefit significantly from structured approa ches that provide clear scaffolding, whilst more experienced students thrive with greater independence. Confirmation inquiry, though sometimes overlooked, serves as an excellent starting point for younger pupils or those new to investigative learning, as they follow established procedures to verify known results.

Successful implementation requires matching the inquiry type to both learning objectives and student readiness. Begin with structured approaches to build confidence and procedural knowledge, then gradually reduce scaffolding as pupils develop critical thinking skills. Consider hybrid models that combine elements, such as providing a research question but allowing methodological choice, to create authentic learning experiences whilst maintaining appropriate support for your specific classroom context.

Successfully implementing inquiry-based learning requires a gradual shift from teacher-centred to student-centred instruction, beginning with structured inquiry before progressing to open-ended investigations. Start by introducing essential questions that connect to your curriculum objectives, ensuring these questions are authentic and meaningful to students' lives. John Dewey's research on experiential learning demonstrates that students engage more deeply when they can relate new knowledge to their existing experiences and interests.

Effective scaffolding remains crucial throughout the implementation process, as John Sweller's cognitive load theory shows that students can become overwhelmed without proper support structures. Begin each inquiry cycle with clear learning intentions and success criteria, then provide thinking frameworks, research templates, and reflection prompts to guide student exploration. Gradually remove these supports as students develop confidence in their inquiry skills, whilst maintaining regular check-ins to monitor progress and provide targeted feedback.

Transform your classroom environment to support collaborative investigation by creating flexible learning spaces and establishing clear protocols for group work and resource sharing. Build in regular opportunities for students to present findings, debate conclusions, and reflect on their learning processes. This approach develops critical thinking skills whilst ensuring evidence-based reasoning becomes second nature to your students.

Assessment in inquiry-based learning requires a fundamental shift from traditional testing towards authentic, process-focused evaluation that captures both student thinking and learning outcomes. Rather than relying solely on end-of-unit examinations, effective assessment strategies must document the journey of discovery, including hypothesis formation, evidence gathering, and reflection processes that define genuine inquiry.

Formative assessment techniques such as learning journals, peer feedback sessions, and teacher obser vation protocols provide rich evidence of student progress throughout the inquiry cycle. As Dylan Wiliam's research demonstrates, frequent formative feedback significantly enhances student achievement when it focuses on specific learning goals and next steps. Portfolio-based assessment allows students to curate their learning journey, showcasing initial questions, research findings, revised thinking, and final conclusions whilst developing crucial self-evaluation skills.

Practical classroom implementation might include structured reflection templates that prompt students to articulate their thinking processes, collaborative assessment rubrics co-created with students, and regular conferencing sessions where teachers guide students through self-assessment. These approaches honour the student-centred nature of inquiry whilst providing teachers with comprehensive evidence of critical thinking development and conceptual understanding that traditional assessments often miss.

Inquiry-based learning transforms differently across curriculum areas, yet the underlying principles of student-centred investigation remain constant. In science, students might explore "Why do some materials float whilst others sink?" through hands-on experimentation, moving beyond memorising density facts to developing genuine scientific reasoning. History lessons become detective work when pupils investigate "What really happened during the Great Fire of London?" using primary sources, maps, and contemporary accounts to construct evidence-based narratives.

Mathematics inquiry shifts from procedural practice to genuine problem-solving. Rather than teaching fraction algorithms directly, teachers might present real-world scenarios: "How can we fairly share three pizzas among four friends?" This approach, supported by Jo Boaler's research on mathematical mindsets, encourages students to discover multiple solution pathways whilst developing deeper conceptual understanding. Similarly, English literature transforms when students investigate character motivations through textual evidence rather than accepting teacher interpretations.

Effective cross-curricular implementation requires careful scaffolding to prevent cognitive overload. Begin with structured inquiries providing clear frameworks, gradually releasing responsibility as students develop investigation skills. Consider your subject's unique demands: science requires hypothesis formation, history demands source evaluation, whilst mathematics needs pattern recognition. This differentiated approach ensures authentic learning experiences whilst maintaining rigorous academic standards across all disciplines.

Effective inquiry-based lesson planning begins with crafting a compelling question that genuinely puzzles students and connects to their lived experiences. Your central inquiry should be open-ended enough to allow multiple pathways of investigation whilst remaining focused on specific learning objectives. Consider John Dewey's emphasis on authentic problems: the most powerful inquiries emerge from real-world dilemmas that students can meaningfully explore through available resources and evidence.

Structure your lessons using a gradual release framework that balances cognitive load with student agency. Begin with shared investigation where you model inquiry processes, then transition to guided practice where small groups tackle related sub-questions with scaffolding. Jerome Bruner's spiral curriculum theory supports this approach, as students build investigative confidence through repeated exposure to inquiry methods across different contexts. Plan specific checkpoints where students can share emerging theories and receive feedback before proceeding independently.

Design flexible assessment opportunities that capture both content learning and inquiry skills development. Rather than traditional end-of-unit tests, consider evidence portfolios where students document their investigation process, peer evaluation of research methods, or presentation formats that mirror authentic professional practices. This approach honours the student-centred nature of inquiry whilst providing you with rich data about both conceptual understanding and critical thinking development.

inquiry-based learning represents a powerful approach to education that can creates critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and a lifelong love of learning. By shifting the focus from rote memorisation to active exploration and discovery, inquiry-based learning helps students to become active participants in their own education. While it presents challenges, these can be overcome with careful planning, appropriate support, and a willingness to embrace new approaches to teaching and assessment.

Ultimately, the goal of education is to prepare students for success in a rapidly changing world. Inquiry-based learning provides students with the skills and knowledge they need to thrive in the 21st century, developing creativity, collaboration, and a deep understanding of the world around them. By embracing inquiry-based learning, educators can helps students to become lifelong learners and active, engaged citizens.

Inquiry-based learning research

Discovery learning meta-analysis

For those who wish to examine deeper into the theory and practice of inquiry-based learning, the following research papers offer valuable insights:

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/a-teachers-guide-to-inquiry-based-learning#article","headline":"Inquiry-Based Learning: A Complete Guide for Teachers","description":"Master inquiry-based learning with practical strategies for implementation. Understand how to design inquiries, scaffold student investigation, and develop...","datePublished":"2021-11-26T16:03:46.231Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/a-teachers-guide-to-inquiry-based-learning"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69441afbfa543482cd0631ca_61a104ee7b1c5ec4e0df188a_Group%2520work%2520skills%2520using%2520inquiry-based%2520learning.jpeg","wordCount":2771},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/a-teachers-guide-to-inquiry-based-learning#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Inquiry-Based Learning: A Complete Guide for Teachers","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/a-teachers-guide-to-inquiry-based-learning"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is Inquiry-based learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Inquiry-based learning is a process of learning that engages learners by creating real-world connections through high-level questioning and exploration . The inquiry-based learning approach encourages learners to engage in experiential learning and problem-based learning."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the components of Inquiry-Based Learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can apply inquiry-based instruction in many ways, but some of its basic components include:"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What is an example of inquiry-based strategies in classroom learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"In a world history class, the COVID-19 pandemic can be used to compare, study and examine the history of pandemics. A group inquiry lesson may have the following components:"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the Challenges of Inquiry-Based Learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"While inquiry-based learning offers numerous benefits, it also presents several challenges for educators. One significant obstacle is the time and effort required to plan and implement inquiry-based activities. Teachers need to carefully design open-ended questions, gather resources, and provide ongoing support to students as they navigate their investigations. This can be particularly demanding for teachers who are accustomed to more traditional, teacher-centred approaches."}}]}]}