Scaffolding in Education: Strategies for Supporting Student Learning

Explore effective scaffolding strategies that empower educators to support student learning, guiding them from dependence to independence in their.

Explore effective scaffolding strategies that empower educators to support student learning, guiding them from dependence to independence in their.

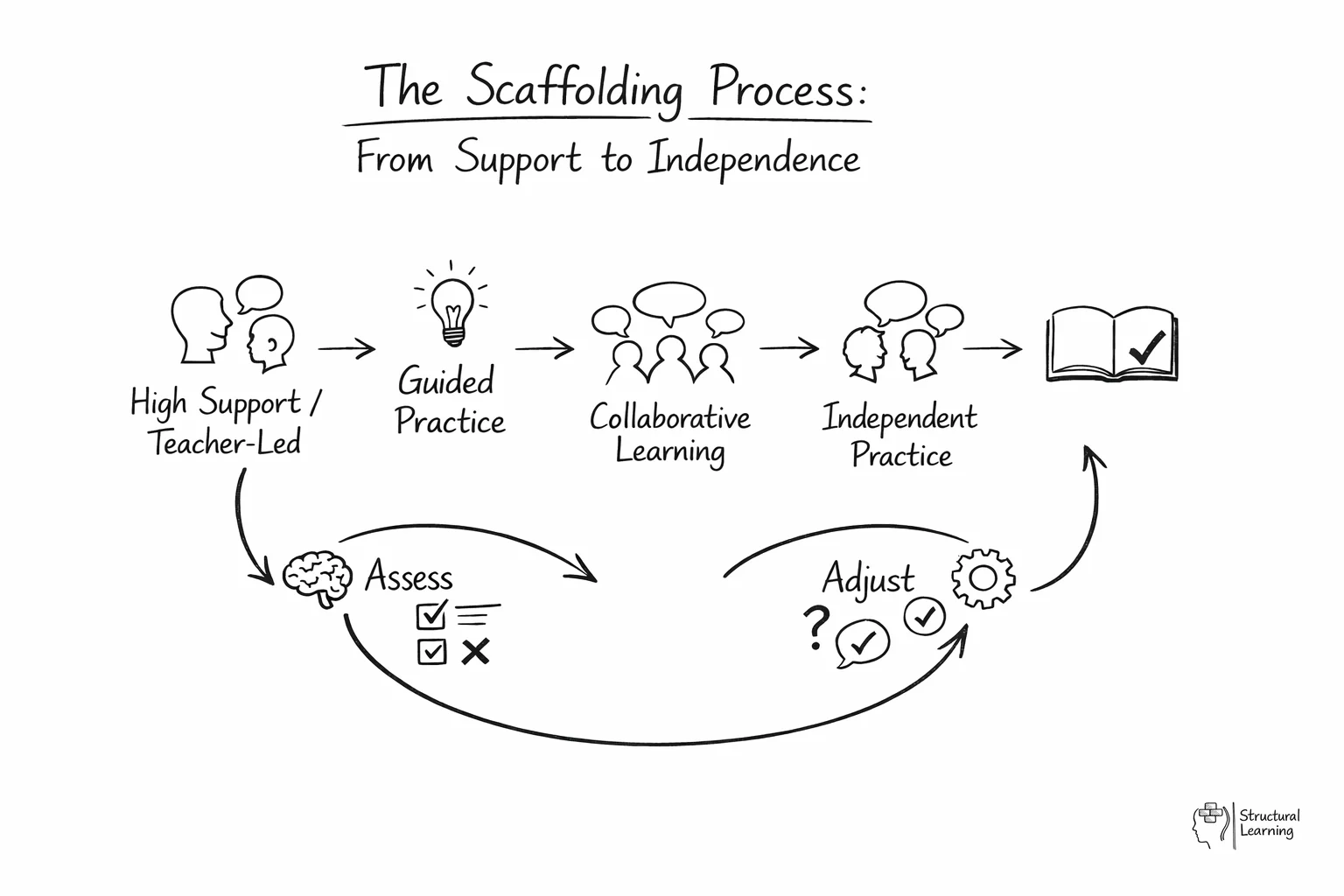

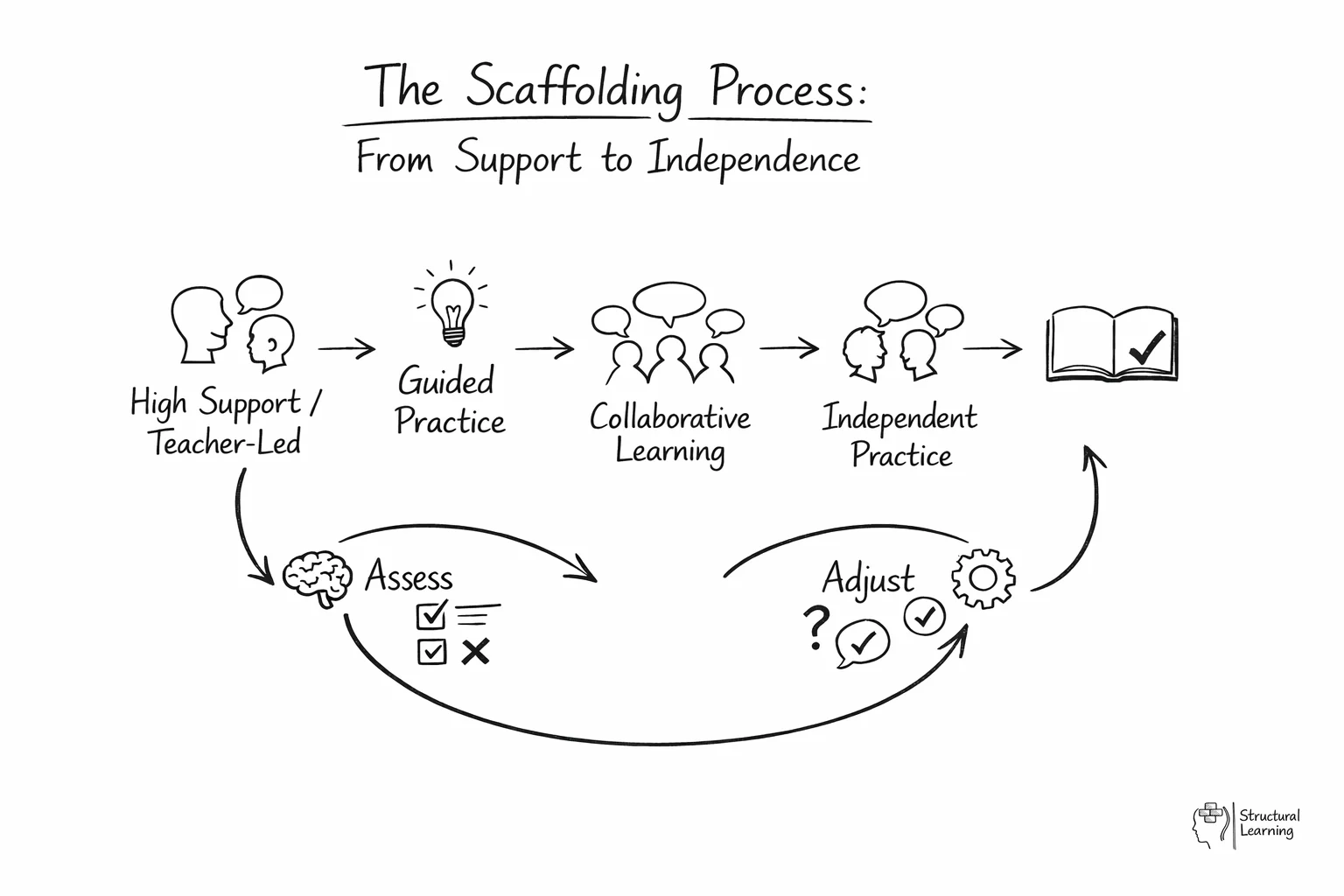

Scaffolding is one of the most powerful instructional strategies available to teachers. Based on Vygotsky's concept of the Zone of Proximal Development, scaffolding involves providing temporary support that enables students to complete tasks they could not manage independently. The key is gradually removing this support as competence develops, moving learners towards independence. This guide explains different scaffolding techniques and how to implement them effectively in your classroom.

Instructional scaffolding is strategically executed by setting clear learning objectives and offering a levelof guidance that is adjusted to the academic level of the student. Teachers might employ scaffolding techniques in both traditional and online learning environments to bolster successful learning. These techniques can include breaking down tasks into smaller, more manageable parts, using structured questioning approaches and inquiry-based learninglike the GROW Model for Coaching, or demonstrating tasks to guide students through the learning experiences.

Conceptual scaffolding is vital, particularly in problem-based and inquiry-based learning, where students engage in discovery learning. This approach aligns with constructivist methodologies like scaffolding in Rosenshine's instructional principles. It helps students to navigate complex concepts by connecting new information with existing knowledge, considering various learning styles in the process. This key concept ensures that the learning experiences are meaningful and that the transition towards independent learning is smooth and effective.

An expert in educational psychology, Jerome Bruner, once remarked, "We begin with the hypothesis that any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development." This underscores the benefits of scaffolding (AI-powered adaptive scaffolding), teachers can adjust the academic content to suit the learner's cognitive abilities, leading to successful learning outcomes.

As the teacher's level of expertise and understanding of the students' needs shape the level of guidance provided, scaffolding remains an adaptable approach. Online courses, with their diverse and broad reach, stand to benefit significantly from this approach, as it allows for personalized learning paths that can be adjusted in real-time.

In essence, scaffolding is about helping students to build upon their existing knowledge base and to encourage self-reliance in the learning process. It is a testament to the belief that with the right support, students can achieve higher levels of understanding and skill than they would independently.

| Scaffolding Type | Purpose | Example Techniques | When to Fade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural Scaffolding | Supports HOW to complete tasks; provides process guidance | Step-by-step checklists, worked examples, procedure posters, flowcharts, task cards | When students can recall steps independently and self-monitor progress |

| Conceptual Scaffolding | Supports WHAT to learn; helps organise knowledge structures | Graphic organisers, concept maps, advance organisers, analogies, visual representations | When students can generate their own connections and categorisations |

| Metacognitive Scaffolding | Supports thinking about thinking; develops self-regulation | Think-alouds, self-questioning prompts, reflection templates, planning frameworks | When students naturally self-monitor, plan, and evaluate their learning |

| Strategic Scaffolding | Supports WHEN to use specific strategies; builds conditional knowledge | Strategy menus, decision trees, worked examples showing strategy choice, think-alouds | When students independently select appropriate strategies for new situations |

| Verbal Scaffolding | Supports through language; guides understanding in dialogue | Questioning, recasting, prompting, cueing, elaborating, confirming | When students can explain concepts and justify reasoning without prompts |

| Social Scaffolding | Supports learning through peer interaction and collaboration | Peer tutoring, collaborative groups, reciprocal teaching, think-pair-share | When students can work productively with peers and seek help appropriately |

Based on Wood, Bruner & Ross (1976) and subsequent research. Effective scaffolding is temporary support that is gradually removed (faded) as learner competence increases - the goal is always independence.

Scaffolding techniques improve learning outcomes by providing temporary support that helps students complete tasks beyond their current ability level. As students gain competence, teachers gradually reduce support, leading to increased independence and deeper understanding. Research shows this approach significantly enhances retention and skill transfer across subject areas.

Learning is a complicated process but in recent years several researchers and writers have helped draw our attention to some simple evidence informed principles that are easy to understand and implement. Placing these principles at the centre of classroom practice gives educators a strong direction when developing their instructional practice.

At Structural Learning, we encourage students to break their learning tasks into chunks. Using the universal thinking framework, learning goals can be broken down into bite-size chunks. This makes the learning process manageable for everyone. A learning task will have several different components to it. For example, a learning task might include 1) research 2) Planning 3) Drafting 4) Writing. Each of these separate stages can be scaffolded with templates and graphic organisers.

Student student achievement can be improved quite drastically if we demonstrate how any given learning task can be approached in this way. Instead of seeing the learning process as an overwhelming task that cannot be undertaken, breaking learning into chunks using our frameworks command words quickly dissolves any anxiety or negative feelings towards the task in hand. Whether you are working in an online learning environment or a classroom, this student-centered learning approach enables students to take more ownership and control of their learning.

Learning goals don't need to be seen as these distant destinations that only the chosen few arrive at. Break the journey down so all the students can come with you. Effectively, a learning task can be broken down into a series of mini, lessons.

Another example of using scaffolding to improve educational results is our concept of mental modelling. Using writers block, educators around the globe have been breaking learning tasks into bite-size chunks that are easy to manage and engaging to participate in. The brightly coloured blocks can be used to scaffold learning in a variety of different environments.

At its essence, the strategy enables children to process abstract ideas and develop critical thinking. Whether you are working with whole class of 30 or a small group of four, organising your ideas and making connections using the blocks puts children on a pathway to success and independence. Having a community of learners who are working together to complete a learning task building on a shared foundation can improve learning outcomes for everyone.

Let's explore some concrete examples of how scaffolding techniques can be implemented across different subject areas:

By providing appropriate scaffolding, teachers can help students to overcome challenges and achieve success in all subject areas. Remember that the key is to gradually reduce support as students become more competent, supporting independence and self-reliance.

The benefits of scaffolding are numerous and far-reaching:

scaffolding is a powerful instructional strategy that can transform the learning experiences for students. By providing temporary support that is tailored to their individual needs, teachers can help students to achieve their full potential.

By continually assessing students' understanding and adapting your scaffolding strategies accordingly, you can create a dynamic and supportive learning environment where all students can thrive.

While scaffolding offers tremendous potential for supporting student learning, teachers frequently encounter three significant challenges that can undermine its effectiveness. Managing diverse ability levels within mixed-attainment classes, avoiding the creation of learned dependency through over-scaffolding, and determining the optimal timing for scaffold removal require careful consideration and strategic planning. Understanding these common pitfalls and implementing targeted solutions can transform scaffolding from a well-intentioned but ineffective practice into a powerful tool for genuine learning progression.

In mixed-attainment classrooms, differentiated scaffolding becomes essential for meeting varied student needs simultaneously. Rather than providing uniform support, teachers can implement tiered scaffolding systems where different groups receive appropriately matched assistance. For example, when teaching persuasive writing, some students might receive sentence starters and vocabulary banks, whilst others work with structural frameworks, and advanced learners focus on rhetorical techniques. Using flexible grouping strategies allows teachers to adjust support levels dynamically, moving students between groups as their competence develops. Digital tools can also facilitate this approach, enabling students to access different levels of guidance through adaptive platforms or choice boards.

Consider implementing a "scaffold withdrawal chart" where you systematically track when to remove support for individual students. Begin by identifying three key support elements in your lesson, then observe which students no longer require each type of assistance. This visual tool helps prevent over-scaffolding whilst ensuring timely independence, creating a personalised learning journey that adapts to each pupil's developing capabilities and confidence levels.

The risk of over-scaffolding presents another critical challenge, as excessive support can create dependency rather than independence. Warning signs include students consistently seeking permission before proceeding, reluctance to attempt tasks without immediate teacher presence, or diminished problem-solving attempts. To combat this, teachers should implement gradual release strategies that systematically reduce support whilst maintaining student confidence. This might involve moving from teacher demonstration to guided practice with prompts, then to collaborative work with peer support, and finally to independent application. Setting clear expectations that scaffolds are temporary learning tools, not permanent crutches, helps establish the appropriate mindset.

Determining when to remove scaffolds requires ongoing formative assessment and individualised decision-making. Teachers should look for evidence of student automaticity in applying skills, successful transfer to new contexts, and confident self-regulation. Rather than removing all support simultaneously, a phased withdrawal approach works more effectively, where elements of scaffolding are gradually eliminated whilst monitoring student performance. Regular check-ins and student self-reflection can inform these timing decisions, ensuring that scaffold removal promotes growth rather than frustration.

These practical scaffolding techniques help teachers provide the right level of support at the right time, enabling all students to access challenging content whilst developing toward independence. Effective scaffolding is responsive, temporary, and always aimed at the goal of student autonomy.

The art of scaffolding lies in finding the "just right" level of support - enough to enable success, but not so much that students aren't doing the cognitive work themselves. Watch for signs that scaffolds should be faded: when students consistently succeed, when they stop referring to supports, or when they can articulate the process themselves. The ultimate goal is always to work yourself out of a job as the scaffold, building learners who can stand on their own.

Effective scaffolding must be carefully tailored to students' developmental stages and curriculum expectations. In the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) and Key Stage 1, scaffolding emphasises concrete, multi-sensory approaches that support emerging literacy and numeracy skills. Teachers might use visual prompts, manipulatives, and guided questioning to help children build foundational understanding. For instance, when teaching phonics, teachers can provide picture cards alongside letter sounds, gradually removing visual supports as children develop automaticity.

As students progress to Key Stage 2, scaffolding shifts towards developing independent learning strategies whilst maintaining appropriate support structures. This might include providing writing frames for extended pieces, offering choice in how students demonstrate understanding, or using peer collaboration as a scaffold. For mathematics, teachers might introduce problem-solving strategies through worked examples before encouraging students to tackle similar problems independently. Graphic organisers become particularly valuable at this stage, helping students structure their thinking across subjects whilst building metacognitive awareness.

In secondary education, scaffolding must prepare students for the analytical demands of GCSE and A-Level assessments. This involves explicitly teaching subject-specific skills such as essay structure, scientific method, or historical source analysis. Teachers should provide assessment criteria breakdowns, model exemplar responses, and gradually increase task complexity. For example, English teachers might scaffold analytical writing by first providing topic sentences, then paragraph starters, before expecting fully independent essays. Similarly, science teachers can scaffold practical work by moving from structured experiments to open investigations.

Research by Wood, Bruner, and Ross demonstrates that effective scaffolding involves the gradual release of responsibility, moving from teacher demonstration through guided practice to independent application. Successful implementation requires continuous assessment of student understanding and flexible adjustment of support levels. Teachers should regularly evaluate whether scaffolds are appropriately challenging, ensuring they promote growth rather than creating dependency whilst building students' confidence and competence across all key stages.

Scaffolding in education is a teaching strategy that provides temporary support to help students complete tasks they cannot manage independently. Based on Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development, teachers gradually remove this support as students develop competence. The goal is to guide learners towards independence whilst building their confidence and understanding.

Start by breaking complex tasks into smaller, manageable parts and provide templates or graphic organisers to guide student work. Use structured questioning techniques to prompt thinking, demonstrate processes before asking students to attempt them independently, and adjust your level of support based on individual student needs. Gradually reduce assistance as students show increased competence and confidence.

Scaffolding significantly improves student learning outcomes by increasing retention and skill transfer across subject areas. It builds student confidence by making challenging tasks feel manageable, reduces anxiety about learning, and helps students develop independent learning skills. Research shows that scaffolded instruction leads to deeper understanding and better academic achievement compared to unsupported learning.

The most common mistake is providing too much support for too long, preventing students from developing independence. Teachers also sometimes fail to adjust scaffolding to individual student needs, using a one-size-fits-all approach. Another frequent error is removing support too quickly before students are ready, which can lead to frustration and decreased confidence.

Effective scaffolding shows students gradually requiring less support whilst maintaining or improving their performance quality. Look for increased student confidence, willingness to attempt tasks independently, and improved problem-solving skills. Students should be able to transfer learned strategies to new, similar tasks without prompting from you.

Scaffolding works effectively across all subject areas, from literacy and numeracy to science and humanities. It is particularly valuable in complex subjects requiring multiple steps, such as essay writing, mathematical problem-solving, and scientific investigations. Any subject involving skill development or conceptual understanding benefits from scaffolded instruction approaches.

Here are practical steps to implement effective scaffolding strategies that support student progression towards independence.

A Year 5 teacher introducing persuasive writing starts by showing a complete example letter, then creates one collaboratively with the class, provides a paragraph frame for students to complete in pairs, and finally asks them to write independently using only a simple checklist. Each stage removes one layer of support while maintaining student success.

Instructional scaffolding research

Scaffolding is one of the most powerful instructional strategies available to teachers. Based on Vygotsky's concept of the Zone of Proximal Development, scaffolding involves providing temporary support that enables students to complete tasks they could not manage independently. The key is gradually removing this support as competence develops, moving learners towards independence. This guide explains different scaffolding techniques and how to implement them effectively in your classroom.

Instructional scaffolding is strategically executed by setting clear learning objectives and offering a levelof guidance that is adjusted to the academic level of the student. Teachers might employ scaffolding techniques in both traditional and online learning environments to bolster successful learning. These techniques can include breaking down tasks into smaller, more manageable parts, using structured questioning approaches and inquiry-based learninglike the GROW Model for Coaching, or demonstrating tasks to guide students through the learning experiences.

Conceptual scaffolding is vital, particularly in problem-based and inquiry-based learning, where students engage in discovery learning. This approach aligns with constructivist methodologies like scaffolding in Rosenshine's instructional principles. It helps students to navigate complex concepts by connecting new information with existing knowledge, considering various learning styles in the process. This key concept ensures that the learning experiences are meaningful and that the transition towards independent learning is smooth and effective.

An expert in educational psychology, Jerome Bruner, once remarked, "We begin with the hypothesis that any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development." This underscores the benefits of scaffolding (AI-powered adaptive scaffolding), teachers can adjust the academic content to suit the learner's cognitive abilities, leading to successful learning outcomes.

As the teacher's level of expertise and understanding of the students' needs shape the level of guidance provided, scaffolding remains an adaptable approach. Online courses, with their diverse and broad reach, stand to benefit significantly from this approach, as it allows for personalized learning paths that can be adjusted in real-time.

In essence, scaffolding is about helping students to build upon their existing knowledge base and to encourage self-reliance in the learning process. It is a testament to the belief that with the right support, students can achieve higher levels of understanding and skill than they would independently.

| Scaffolding Type | Purpose | Example Techniques | When to Fade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural Scaffolding | Supports HOW to complete tasks; provides process guidance | Step-by-step checklists, worked examples, procedure posters, flowcharts, task cards | When students can recall steps independently and self-monitor progress |

| Conceptual Scaffolding | Supports WHAT to learn; helps organise knowledge structures | Graphic organisers, concept maps, advance organisers, analogies, visual representations | When students can generate their own connections and categorisations |

| Metacognitive Scaffolding | Supports thinking about thinking; develops self-regulation | Think-alouds, self-questioning prompts, reflection templates, planning frameworks | When students naturally self-monitor, plan, and evaluate their learning |

| Strategic Scaffolding | Supports WHEN to use specific strategies; builds conditional knowledge | Strategy menus, decision trees, worked examples showing strategy choice, think-alouds | When students independently select appropriate strategies for new situations |

| Verbal Scaffolding | Supports through language; guides understanding in dialogue | Questioning, recasting, prompting, cueing, elaborating, confirming | When students can explain concepts and justify reasoning without prompts |

| Social Scaffolding | Supports learning through peer interaction and collaboration | Peer tutoring, collaborative groups, reciprocal teaching, think-pair-share | When students can work productively with peers and seek help appropriately |

Based on Wood, Bruner & Ross (1976) and subsequent research. Effective scaffolding is temporary support that is gradually removed (faded) as learner competence increases - the goal is always independence.

Scaffolding techniques improve learning outcomes by providing temporary support that helps students complete tasks beyond their current ability level. As students gain competence, teachers gradually reduce support, leading to increased independence and deeper understanding. Research shows this approach significantly enhances retention and skill transfer across subject areas.

Learning is a complicated process but in recent years several researchers and writers have helped draw our attention to some simple evidence informed principles that are easy to understand and implement. Placing these principles at the centre of classroom practice gives educators a strong direction when developing their instructional practice.

At Structural Learning, we encourage students to break their learning tasks into chunks. Using the universal thinking framework, learning goals can be broken down into bite-size chunks. This makes the learning process manageable for everyone. A learning task will have several different components to it. For example, a learning task might include 1) research 2) Planning 3) Drafting 4) Writing. Each of these separate stages can be scaffolded with templates and graphic organisers.

Student student achievement can be improved quite drastically if we demonstrate how any given learning task can be approached in this way. Instead of seeing the learning process as an overwhelming task that cannot be undertaken, breaking learning into chunks using our frameworks command words quickly dissolves any anxiety or negative feelings towards the task in hand. Whether you are working in an online learning environment or a classroom, this student-centered learning approach enables students to take more ownership and control of their learning.

Learning goals don't need to be seen as these distant destinations that only the chosen few arrive at. Break the journey down so all the students can come with you. Effectively, a learning task can be broken down into a series of mini, lessons.

Another example of using scaffolding to improve educational results is our concept of mental modelling. Using writers block, educators around the globe have been breaking learning tasks into bite-size chunks that are easy to manage and engaging to participate in. The brightly coloured blocks can be used to scaffold learning in a variety of different environments.

At its essence, the strategy enables children to process abstract ideas and develop critical thinking. Whether you are working with whole class of 30 or a small group of four, organising your ideas and making connections using the blocks puts children on a pathway to success and independence. Having a community of learners who are working together to complete a learning task building on a shared foundation can improve learning outcomes for everyone.

Let's explore some concrete examples of how scaffolding techniques can be implemented across different subject areas:

By providing appropriate scaffolding, teachers can help students to overcome challenges and achieve success in all subject areas. Remember that the key is to gradually reduce support as students become more competent, supporting independence and self-reliance.

The benefits of scaffolding are numerous and far-reaching:

scaffolding is a powerful instructional strategy that can transform the learning experiences for students. By providing temporary support that is tailored to their individual needs, teachers can help students to achieve their full potential.

By continually assessing students' understanding and adapting your scaffolding strategies accordingly, you can create a dynamic and supportive learning environment where all students can thrive.

While scaffolding offers tremendous potential for supporting student learning, teachers frequently encounter three significant challenges that can undermine its effectiveness. Managing diverse ability levels within mixed-attainment classes, avoiding the creation of learned dependency through over-scaffolding, and determining the optimal timing for scaffold removal require careful consideration and strategic planning. Understanding these common pitfalls and implementing targeted solutions can transform scaffolding from a well-intentioned but ineffective practice into a powerful tool for genuine learning progression.

In mixed-attainment classrooms, differentiated scaffolding becomes essential for meeting varied student needs simultaneously. Rather than providing uniform support, teachers can implement tiered scaffolding systems where different groups receive appropriately matched assistance. For example, when teaching persuasive writing, some students might receive sentence starters and vocabulary banks, whilst others work with structural frameworks, and advanced learners focus on rhetorical techniques. Using flexible grouping strategies allows teachers to adjust support levels dynamically, moving students between groups as their competence develops. Digital tools can also facilitate this approach, enabling students to access different levels of guidance through adaptive platforms or choice boards.

Consider implementing a "scaffold withdrawal chart" where you systematically track when to remove support for individual students. Begin by identifying three key support elements in your lesson, then observe which students no longer require each type of assistance. This visual tool helps prevent over-scaffolding whilst ensuring timely independence, creating a personalised learning journey that adapts to each pupil's developing capabilities and confidence levels.

The risk of over-scaffolding presents another critical challenge, as excessive support can create dependency rather than independence. Warning signs include students consistently seeking permission before proceeding, reluctance to attempt tasks without immediate teacher presence, or diminished problem-solving attempts. To combat this, teachers should implement gradual release strategies that systematically reduce support whilst maintaining student confidence. This might involve moving from teacher demonstration to guided practice with prompts, then to collaborative work with peer support, and finally to independent application. Setting clear expectations that scaffolds are temporary learning tools, not permanent crutches, helps establish the appropriate mindset.

Determining when to remove scaffolds requires ongoing formative assessment and individualised decision-making. Teachers should look for evidence of student automaticity in applying skills, successful transfer to new contexts, and confident self-regulation. Rather than removing all support simultaneously, a phased withdrawal approach works more effectively, where elements of scaffolding are gradually eliminated whilst monitoring student performance. Regular check-ins and student self-reflection can inform these timing decisions, ensuring that scaffold removal promotes growth rather than frustration.

These practical scaffolding techniques help teachers provide the right level of support at the right time, enabling all students to access challenging content whilst developing toward independence. Effective scaffolding is responsive, temporary, and always aimed at the goal of student autonomy.

The art of scaffolding lies in finding the "just right" level of support - enough to enable success, but not so much that students aren't doing the cognitive work themselves. Watch for signs that scaffolds should be faded: when students consistently succeed, when they stop referring to supports, or when they can articulate the process themselves. The ultimate goal is always to work yourself out of a job as the scaffold, building learners who can stand on their own.

Effective scaffolding must be carefully tailored to students' developmental stages and curriculum expectations. In the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) and Key Stage 1, scaffolding emphasises concrete, multi-sensory approaches that support emerging literacy and numeracy skills. Teachers might use visual prompts, manipulatives, and guided questioning to help children build foundational understanding. For instance, when teaching phonics, teachers can provide picture cards alongside letter sounds, gradually removing visual supports as children develop automaticity.

As students progress to Key Stage 2, scaffolding shifts towards developing independent learning strategies whilst maintaining appropriate support structures. This might include providing writing frames for extended pieces, offering choice in how students demonstrate understanding, or using peer collaboration as a scaffold. For mathematics, teachers might introduce problem-solving strategies through worked examples before encouraging students to tackle similar problems independently. Graphic organisers become particularly valuable at this stage, helping students structure their thinking across subjects whilst building metacognitive awareness.

In secondary education, scaffolding must prepare students for the analytical demands of GCSE and A-Level assessments. This involves explicitly teaching subject-specific skills such as essay structure, scientific method, or historical source analysis. Teachers should provide assessment criteria breakdowns, model exemplar responses, and gradually increase task complexity. For example, English teachers might scaffold analytical writing by first providing topic sentences, then paragraph starters, before expecting fully independent essays. Similarly, science teachers can scaffold practical work by moving from structured experiments to open investigations.

Research by Wood, Bruner, and Ross demonstrates that effective scaffolding involves the gradual release of responsibility, moving from teacher demonstration through guided practice to independent application. Successful implementation requires continuous assessment of student understanding and flexible adjustment of support levels. Teachers should regularly evaluate whether scaffolds are appropriately challenging, ensuring they promote growth rather than creating dependency whilst building students' confidence and competence across all key stages.

Scaffolding in education is a teaching strategy that provides temporary support to help students complete tasks they cannot manage independently. Based on Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development, teachers gradually remove this support as students develop competence. The goal is to guide learners towards independence whilst building their confidence and understanding.

Start by breaking complex tasks into smaller, manageable parts and provide templates or graphic organisers to guide student work. Use structured questioning techniques to prompt thinking, demonstrate processes before asking students to attempt them independently, and adjust your level of support based on individual student needs. Gradually reduce assistance as students show increased competence and confidence.

Scaffolding significantly improves student learning outcomes by increasing retention and skill transfer across subject areas. It builds student confidence by making challenging tasks feel manageable, reduces anxiety about learning, and helps students develop independent learning skills. Research shows that scaffolded instruction leads to deeper understanding and better academic achievement compared to unsupported learning.

The most common mistake is providing too much support for too long, preventing students from developing independence. Teachers also sometimes fail to adjust scaffolding to individual student needs, using a one-size-fits-all approach. Another frequent error is removing support too quickly before students are ready, which can lead to frustration and decreased confidence.

Effective scaffolding shows students gradually requiring less support whilst maintaining or improving their performance quality. Look for increased student confidence, willingness to attempt tasks independently, and improved problem-solving skills. Students should be able to transfer learned strategies to new, similar tasks without prompting from you.

Scaffolding works effectively across all subject areas, from literacy and numeracy to science and humanities. It is particularly valuable in complex subjects requiring multiple steps, such as essay writing, mathematical problem-solving, and scientific investigations. Any subject involving skill development or conceptual understanding benefits from scaffolded instruction approaches.

Here are practical steps to implement effective scaffolding strategies that support student progression towards independence.

A Year 5 teacher introducing persuasive writing starts by showing a complete example letter, then creates one collaboratively with the class, provides a paragraph frame for students to complete in pairs, and finally asks them to write independently using only a simple checklist. Each stage removes one layer of support while maintaining student success.

Instructional scaffolding research

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/scaffolding-in-education-a-teachers-guide#article","headline":"Scaffolding in Education: Strategies for Supporting Student Learning","description":"Master the art of scaffolding in education. Learn practical strategies for providing temporary support that helps students progress from dependence to...","datePublished":"2021-08-16T10:33:45.683Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/scaffolding-in-education-a-teachers-guide"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6969001a0c96bd17bb2aa859_69690011f4cbd26b8a64166a_scaffolding-in-education-a-teachers-guide-illustration.webp","wordCount":3793},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/scaffolding-in-education-a-teachers-guide#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Scaffolding in Education: Strategies for Supporting Student Learning","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/scaffolding-in-education-a-teachers-guide"}]}]}