Revision Techniques That Work: Evidence-Based Strategies for Students

Discover evidence-based revision strategies that actually work. Learn effective techniques backed by cognitive science to help students succeed in exams.

Discover evidence-based revision strategies that actually work. Learn effective techniques backed by cognitive science to help students succeed in exams.

| Feature | Popular Methods (Re-reading, Highlighting) | Retrieval Practice | Spaced Learning | Interleaving& Elaboration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best For | Initial familiarity with content | Strengthening memory cues and exam performance | Long-term retention of information | Deep understanding and application |

| Key Strength | Feels productive and enjoyable | Actively strengthens memory through testing | Prevents forgetting over time | Builds connections between concepts |

| Limitation | Produces minimal lasting learning | More effortful than passive review | Requires planning and discipline | Can be cognitively demanding |

| Age Range | All ages (commonly misused) | GCSE and A-Level students | Secondary school and above | Advanced secondary and higher education |

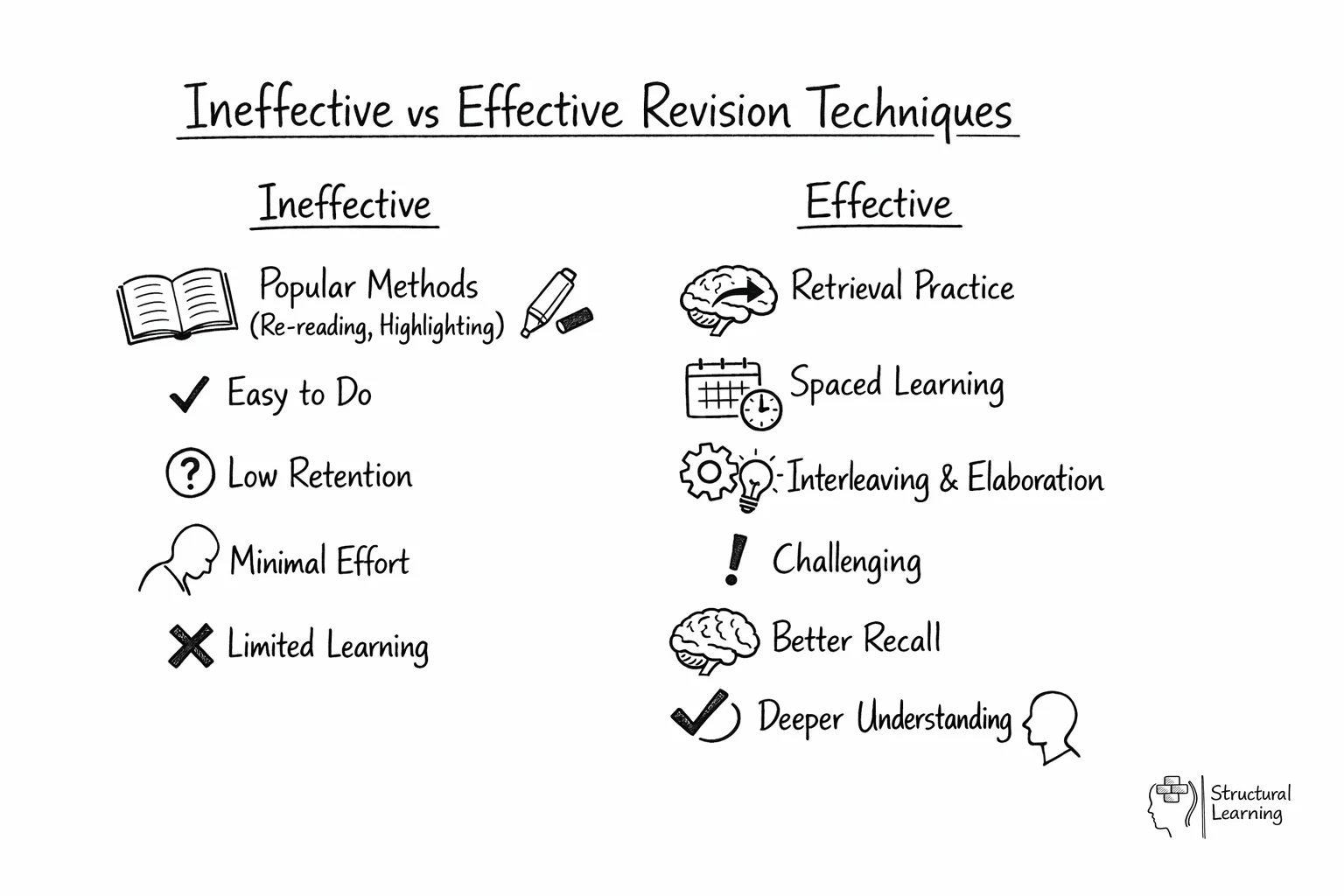

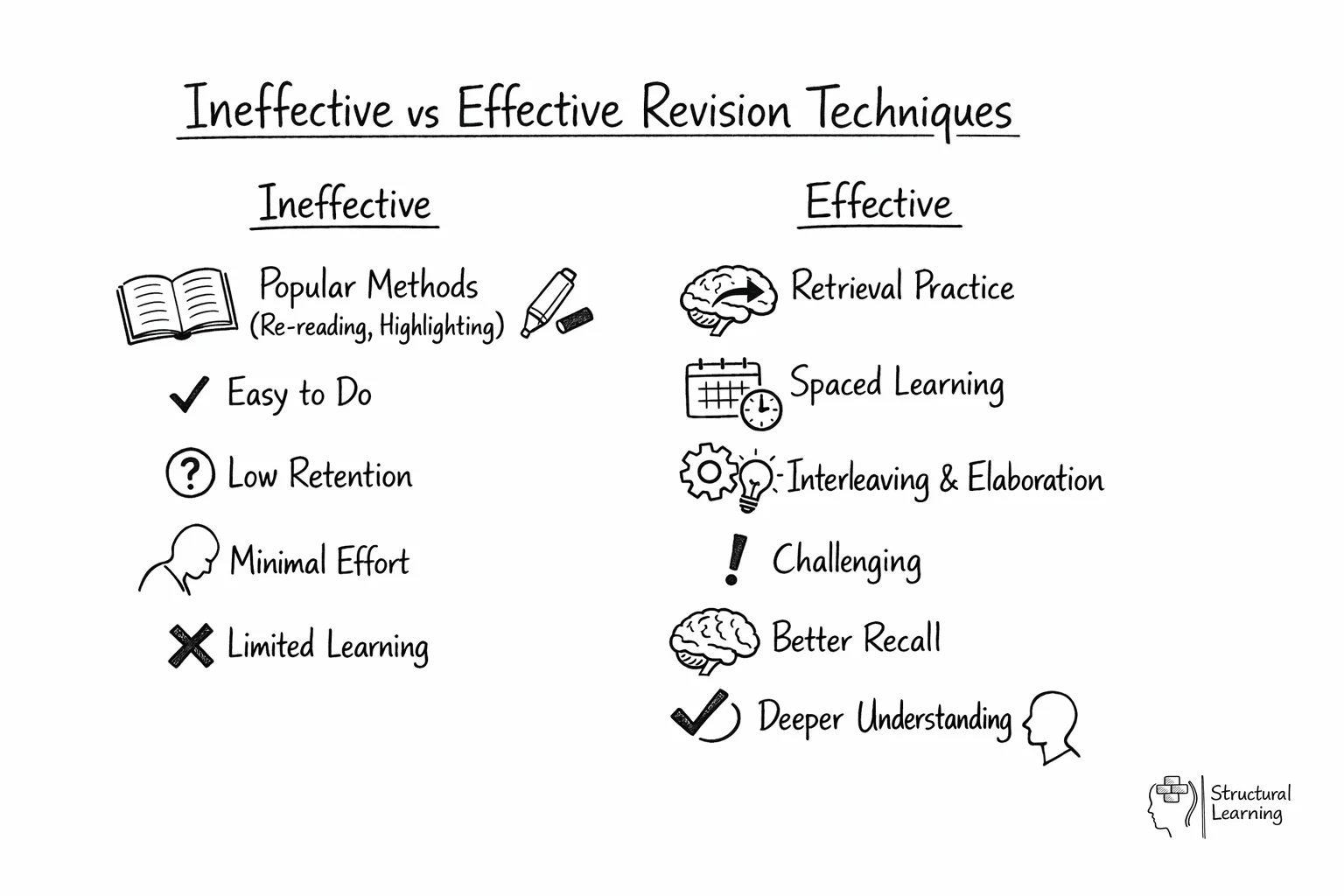

Most students revise ineffectively, relying on techniques like re-reading and highlighting that feel productive but produce little lasting learning. Cognitive science has identified revision strategies that genuinely work: retrieval practice, spaced learning, interleaving, and elaboration. These techniques are more effort ful than passive review but far more effective. This guide explains why common revision approaches fail, what the evidence says works, and how teachers can help students adopt more effective revision habits before examinations.

The art and science of studying independently has helped us understand what activities enable students to effectively understand and recall important information. Within all of our articles on this site, we have tried to explain the fundamental principles of how we all think and learn. This article focuses in on the specific activities that students participate in when trying to prepare themselves for summative assessments.

For some of us, it has been three years since we last prepared students for public exams set by the exam boards. For those newer to the profession, this may be the first time you've been asked to deliver a four-hour study session the day before the GCSE Maths exam or experienced the marking that follows May half term, otherwise known as the essay-writing practice marathon. Do not worry: this article is here to help! In this post, we will move away from passive revision tactics and look at making the most out of revision periods with a more effective mix of learning techniques.

The most effective revision techniques according to cognitive science are recollection exercises, scheduled复习, 换底学习, 和 精要化思维 These active strategies require more effort than passive methods like re-reading but produce significantly better retention and exam performance. Students who use these evidence-based techniques consistently outperform those using traditional highlighting and note-taking methods.

Scientific studies have shown that if a revision strategy is enjoyable and rated effective by students, it is probably one of the least effective strategies they could be using! Focusing on quality rather than quantity will make a real difference to the amount of productive study time students can achieve, increase their motivation for revision, and reduce teachers' workload.

While students' motivation for revision is likely to be at its highest as they prepare for GCSEs and A-Levels, their method of revision may be letting them down. They are probably already doing short periods of revision, taking regular breaks, splitting large topics into bite-sized chunks, and using memory tricks such as mnemonics. These are all good approaches, but what they do with the manageable chunks of information during their short bursts of revision will make the difference between plateauing and exam success.

If a student uses a one-hour revision session to complete a short exam question, write an essay and then checks their understanding using the mark scheme, they will have gained far more that one hour than a student who spends two hours writing revision notes with a personal tutor or highlighting their way through revision guides.

how the theories and findings from cognitive science can improve our understanding of how students learn and therefore which revision techniques will be most effective for them.

Cognitive research shows that effective revision methods work by forcing the brain to actively retrieve information rather than passively review it. Methods like retrieval practice strengthen memory pathways and create multiple cues for accessing information during exams. Passive techniques like re-reading create an illusion of knowledge but fail to build the neural connections needed for long-term retention.

Learning results in a permanent change to a student's long-term memory. Information must first be processed by the short-term memory and then encoded into the long-term memory. Our short-term memory has a very limited capacity and duration, which means it can become overloaded quickly.

Common (and hopefully less common!) causes of cognitive overload:

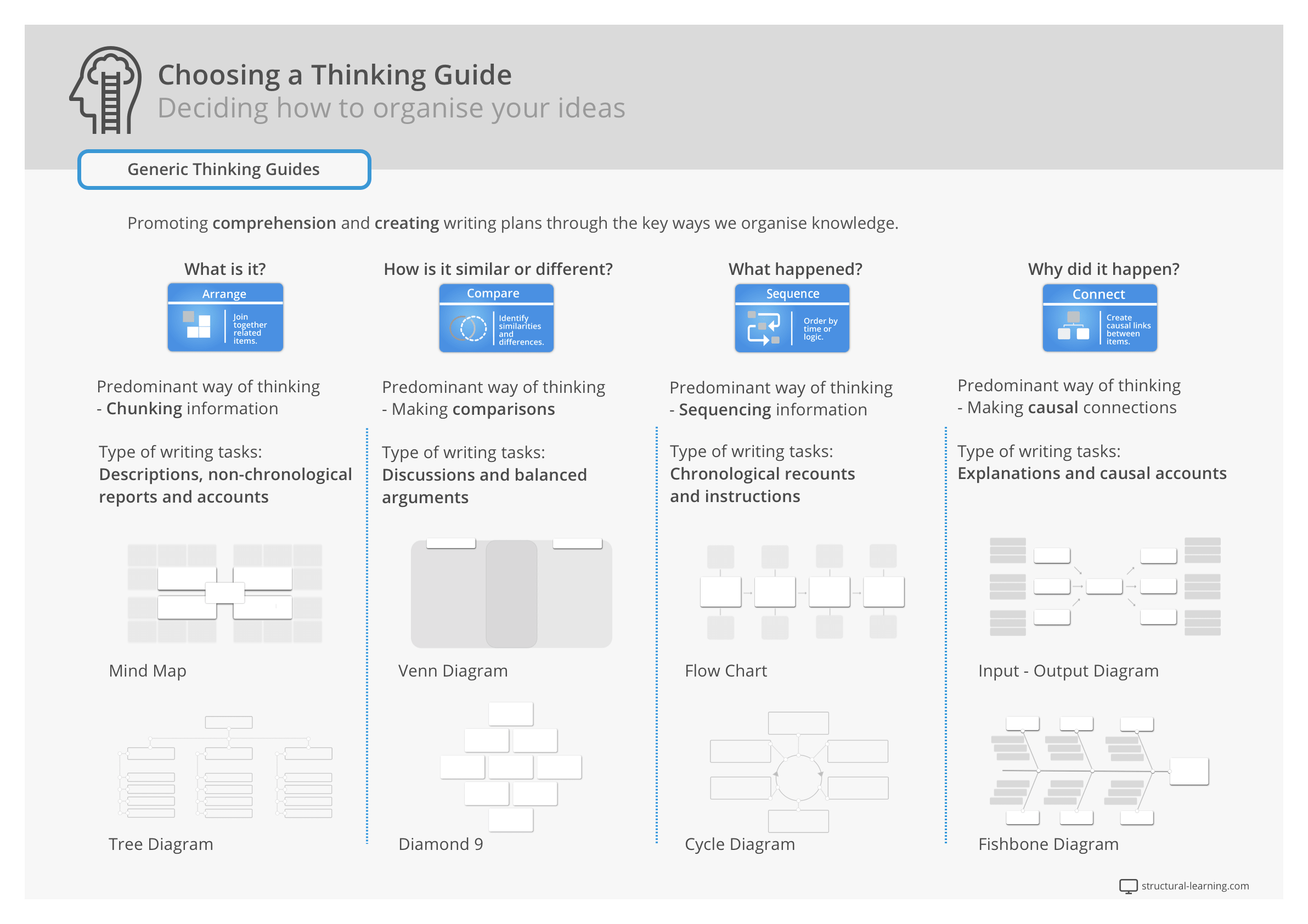

Relieving pressure on the short-term memory, by either reducing exposure to redundant information or by presenting the same information to two different stores ( dual coding), we increase the likelihood of the information being successfully encoded to the long-term memory. This process requires repetition (e.g. Rote learning) or interacting with the new information in a meaningful way using a mix of learning techniques. Examples of this can include:

When new information is successfully encoded into the long-term memory, the next challenge is being able to retrieve this new knowledge when it is needed. Our long-term memory may have unlimited capacity and duration but this means that it can be difficult or impossible to remember a precise skill or fact when it is required. The long-term memory relies on cues to access the information we need; the more cues associated with a memory, the easier it is to retrieve it.

The purpose of revision is to strengthen memory retrieval pathways and ensure information can be accessed under exam conditions. Effective revision transforms surface-level recognition into deep understanding that students can apply in different contexts. Rather than simply refreshing memory, revision should actively reconstruct knowledge and identify gaps in understanding.

The goal of revision is to increase and strengthen the cues associated with prior learning so that the information can be readily available and retrieved when needed. This can include information about exam techniques, subject-specific key words, essay plans, dates, skills or facts. Every time we retrieve a piece of information from our long-term memory, we strengthen a cue associated with that piece of information as well as the cues associated with related pieces of information. Revision time can be used to increase the number of cues by completing activities that require prior learning to be used in multiple ways.

If revision techniques do not strengthen cues or increase the number of cues, they should be replaced by ones that do. Rereading or highlighting notes, copying out a mind map, using a text book to complete exam papers or study notes to support essay writing are unlikely to have a great impact on the cues used by the long-term memory. Active rather than passive retrieval is a factor in determining how successful a revision technique will be. A poor revision style might include simply rereading a page or rewriting (word for word) answers to an essay question.

Active revision strategies require students to do a lot of thinking. Learning anything new is hard work and students will need to be in the right frame of mind. The human brain requires information to be organised and structured in such a way that it's easier to retrieve. This is the result of hard thinking and there are no shortcuts or real memory tricks we can use for this.

Keep in mind that the goal of revision is to strengthen and increase the cues used by the long-term memory. Revision time should be focused on retrieving, and ideally using, the content that needs revision; this will build a deeper understanding of the topic being studied and make it easier to retrieve the information when it is needed.

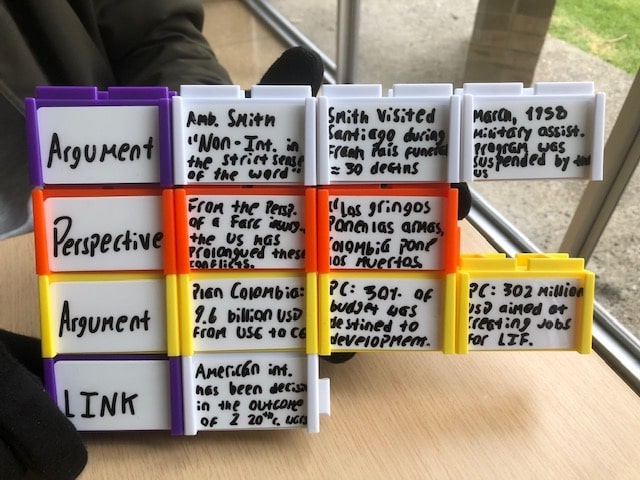

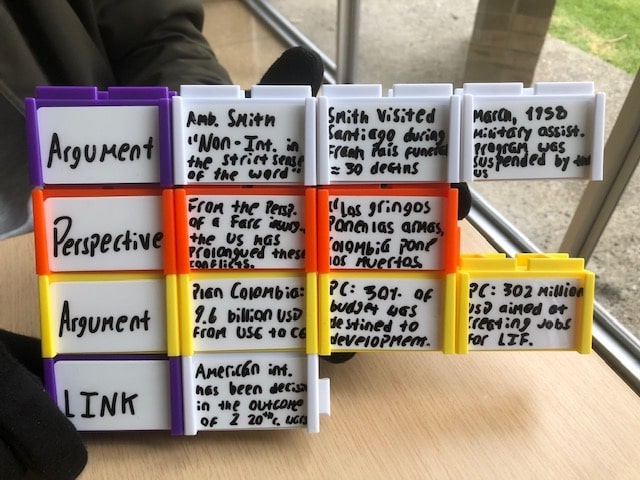

Flash cards can be a great revision tool when used correctly: reading the question and then either speaking aloud or writing down their answer before turning the card over to reveal the answer. The danger of flash cards comes when students read the question and turn it over to read the answer and think 'I knew that'. They have not practiced retrieving the information and the process may also give them a false sense of confidence.

For GCSEs and A-Levels that are essay based subjects, there is no such thing as too much essay-writing practice, although the students may disagree! Open book essays are fine if the students need exam technique practice without worrying about the content, but in all other cases, closed book essay-writing practice will be more beneficial. It's fine for them to have study time beforehand to read through their notes or revision guides, but these should then be put away for students to practice retrieving the information while they complete the essay question.

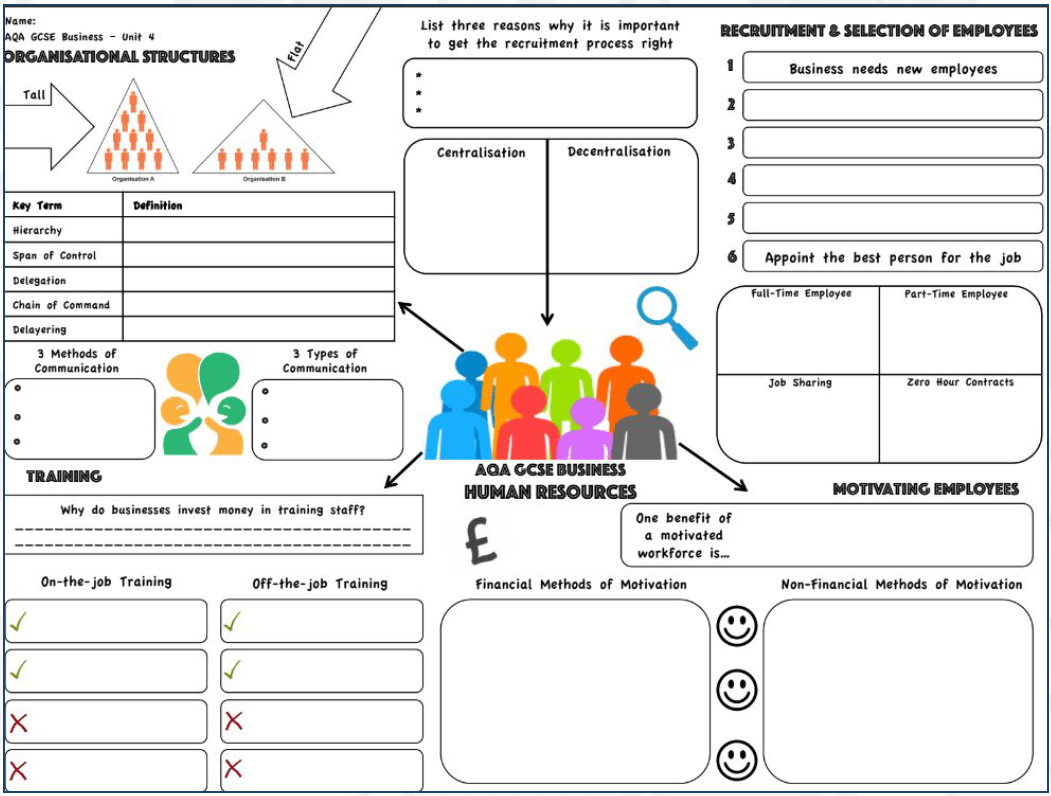

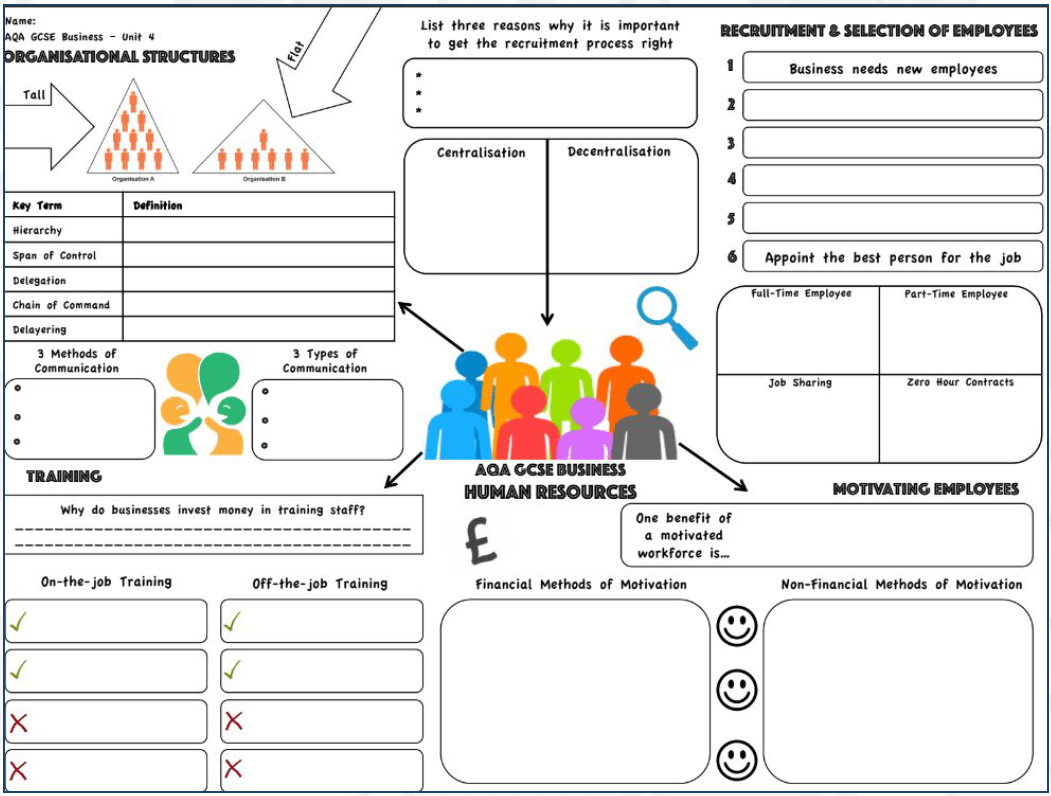

Completing exam papers without notes, recreating mind maps or a list of key words from memory, having plenty of essay practice and spending 5-minute periods of free recall are all valid and effective revision techniques. And the best part: even if the information they recall isn't quite correct and the work isn't marked by a teacher, their memory for the correct information and related information will improve!

There are plenty of effective revision techniques available to students. To ensure their study time is most productive, they must be retrieving information. Scientific studies have shown that students prefer revision techniques that reconfirm their prior understanding, such as reading through revision notes, using flash cards incorrectly, or highlighting text. Retrieval can be uncomfortable, especially if students are revising a topic they find difficult, but reassure them that this means their revision technique is working.

What revision techniques might work for your students? We'll go into more detail shortly but you might want to consider:

Students should prioritise topics by identifying areas of weakness through practice tests and self-assessment rather than focusing on topics they find easiest. The most effective approach combines high-value topics that appear frequently in exams with personal knowledge gaps identified through retrieval practice. Teachers can help by providing topic weightings and diagnostic assessments to guide student choices.

The perfect revision timetable doesn't exist. I have created many revision timetables for my students over the years, but all they really need is periods of dedicated revision time and to spend that time revising the right topics. Students often need help identifying which topics they know well enough to revise less frequently and which topics require constant revision. Providing students with plenty of opportunities to show you their current understanding, probably through completing past papers, will allow you to focus their revision on the topics that need the most attention.

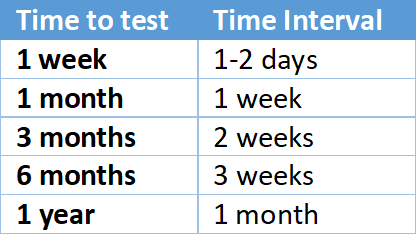

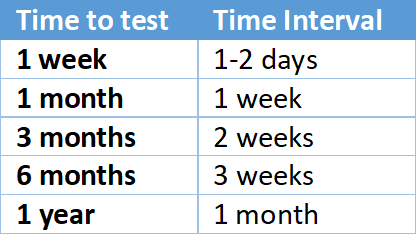

If students are using flash cards or study notes during their revision sessions, encourage them to organise the cards into three piles: topics that need revision every two or three days, topics that need revision once a week, and topics that need revision less frequently than once a fortnight. This will enable their revision time each day to be focused on the topics that need the most attention. For related approaches, explore Characteristics of Effective Learning: A Complete..

Teachers can implement evidence-based revision by building regular retrieval practice into lessons through low-stakes quizzing and spaced review of previous topics. Start by teaching students how to create effective flashcards and use techniques like the Leitner system for spaced repetition. Model these techniques explicitly and provide structured revision timetables that incorporate spacing and interleaving principles.

This is my favourite section of any article! I love thinking about how the findings from research can be applied to classroom practices.

How can cognitive science help our students to achieve exam success? There are so many ways, but I've narrowed it down to six revision techniques that are all supported by research and made them fit into a useful acronym for students: REVISE!

This should be the first consideration of any revision session. Encourage students to ask themselves 'does this method of revision require me to retrieve information from my long-term memory?' There are so many ways that students can retrieve information, even during a short period of independent study:

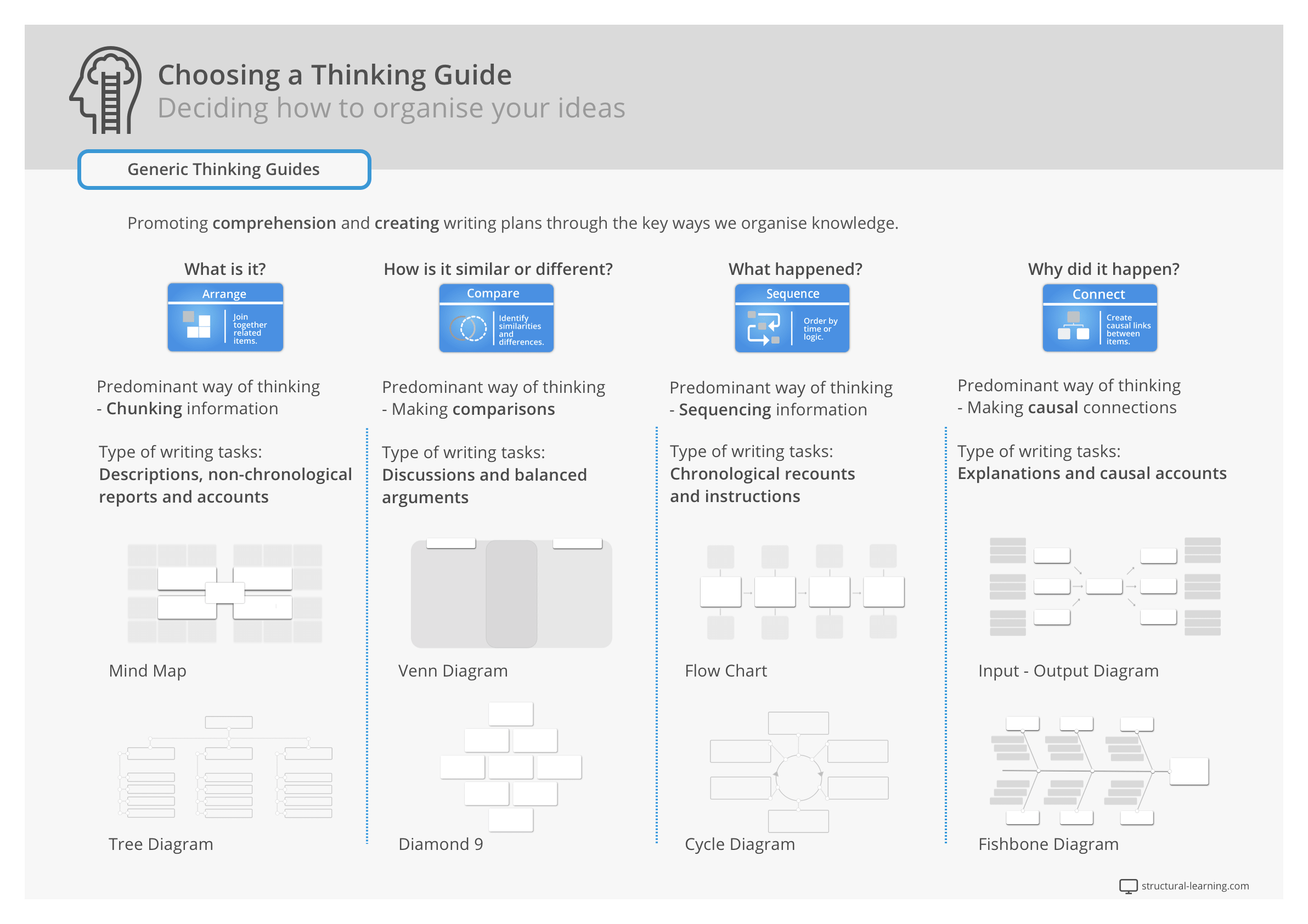

This revision technique is designed to strengthen the connections between different concepts in the long-term memory. Students should read through their study notes for one or two topics, put these notes away and try listing the similarities and differences between the two passages they have just read. This could also be done to compare two or more of the subjects they are studying.

Encourage students to gain a deeper understanding by asking themselves questions such as 'what if..?', 'why does..?' or 'how do we know..?'.

This refers to dual coding, but the acronym wouldn't work as well if it was REDISE!

Encourage students to use images and text to represent information in their study notes or flash cards. This will give them additional cues to help their long-term memory retrieve the content when they need it. You can also use this technique when you are presenting new information for the first time to make it more memorable.

Interleaving means moving between different topics during a revision session. Students will be more productive if they spend 20-30 minutes (at GCSE) or 30-40 minutes (at A-Level) revising a topic before moving on to a different one. They can alternate between two different topics during one revision session or work through topics from each of their subjects. Interleaving can also be used in the classroom by combining two topics together in a question or inserting a question from a previous topic into a low-stakes quiz.

Spacing revision sessions for one topic over two weeks is far more beneficial than spending the same amount of time revisingin just one day. Ideally, students should be revising (retrieving) new information soon after it has been learnt and then increasing the length of time between each subsequent retrieval.

A colleague in my school (who is exceptionally organised!) places each new topic she teaches into her planner one week and one month after she has taught it. She looks at the topics written in her planner each week and includes them in a low-stakes quiz, ensuring that every topic is revised in class at least twice.

Examples provide additional cues for our long-term memory. They can be used in class to improve students' understanding of abstract concepts and the list of examples can be added to for homework and revision. Encourage students to use some of their revision time to recreate lists of these examples.

Teachers should advise students to replace passive revision with active techniques: test yourself frequently, space out revision sessions, and mix different topics rather than blocking similar content. Emphasize that effective revision feels harder than re-reading but produces better results. Provide specific strategies like creating practice questions, teaching concepts to others, and using retrieval practice apps or flashcards.

The advice I will be giving my students during this revision season is simple: REVISE!

I will be reminding them about how our memory works and encouraging them to use the six techniques above to ensure that every minute they spend revising is time well spent.

I will also be telling them that revision should be deliberately difficult.

And finally: retrieve, retrieve, retrieve!

Key research includes Roediger and Butler's work on the testing effect, Bjork's studies on desirable difficulties, and Dunlosky's comprehensive review ranking revision techniques by effectiveness. These studies consistently show retrieval practice and distributed practice outperform massed practice and re-reading. The evidence base spans decades of cognitive psychology research across different age groups and subject areas.

The studies reviewed indicate that various active revision techniques, such as team-based learning, online practice tests, integrated revision and assessment methods, test question templates, and interactive computer-based systems, can significantly enhance student performance and learning efficiency during exam periods.

1. Adapting Team‐Based Learning Concepts Into an Effective Anatomy Revision Session

This study discusses the adaptation of team-based learning concepts into anatomy revision sessions. It emphasises the use of quizzes for retrieval practice and peer learning, which helps students understand topics better and reveals knowledge gaps through many questions in a short timeframe (Croker & Burgess, 2020).

2. JUST HOW MUCH PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT? USING AN ONLINE TEST AS A REVISION TOOLFOR STUDENTS

This paper explores the use of online practice tests as a revision tool for undergraduate business students. The study found that unlimited attempts at practice tests can significantly improve examination performance and reduce revision time (Bocij & Gautam, 2017).

3. Integral Revision, In Semester Examination and Evaluation of Content, II Technique

This paper presents the IRSIEC-II technique, which integrates revision, examination, and assessment using Internet of Things tools. The technique enhances active learning by allowing simultaneous revision and evaluation, leading to increased student learn ingrates compared to traditional methods (Mulla et al., 2021).

4. Testing in the Age of Active Learning: Test Question Templates Help to Align Activities and Assessments

This study introduces Test Question Templates (TQTs) to help align active learning activities with traditional exams. TQTs help students prepare for exams by generating various question formats, which enhances their readiness and understanding of the material (Crowther et al., 2020).

5. An interactive computer‐based revision aid

This paper discusses a computer-based revision system using multiple-choice questions. It tracks user performance and has been positively received by medical students, indicating its effectiveness in aiding revision (Stevens & Harris, 1977).

The most effective revision techniques are practice retrieval, timed复习, 分散练习, 和 扩展解释 These evidence-based strategies require more effort than passive methods but produce significantly better retention and exam performance compared to traditional highlighting and note-taking methods.

Highlighting and re-reading create an illusion of knowledge because they feel productive and enjoyable, but they fail to build the neural connections needed for long-term retention. These passive techniques don't force the brain to actively retrieve information, which means they produce minimal lasting learning despite students feeling confident about their progress.

Teachers can encourage students to replace passive review with active testing techniques such as completing practice exam questions, writing essays, and checking understanding using mark schemes. The key is ensuring students actively reconstruct knowledge rather than simply recognising information, which strengthens memory pathways and creates multiple cues for accessing information during exams.

Retrieval practice is most effective for GCSE and A-Level students, whilst spaced learning works well for secondary school students and above. Interleaving and elaboration are best suited for advanced secondary and higher education students, as these techniques can be cognitively demanding and require more sophisticated thinking skills.

The main challenges include students' resistance to more effortful techniques when passive methods feel easier and more enjoyable. Additionally, effective revision strategies like spaced learning require planning and discipline, whilst techniques like interleaving can be cognitively demanding and may initially feel less productive to students.

Students using ineffective techniques typically spend hours highlighting revision guides, writing lengthy notes, or repeatedly re-reading materials whilst feeling productive and confident. If revision methods are enjoyable and rated as effective by students, research suggests they are probably amongst the least effective strategies available.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into revision techniques that work: evidence-based strategies for students and its application in educational settings.

Test‐enhanced learning in medical education 576 citations

Larsen et al. (2008)

This paper examines how testing itself can enhance learning in medical education, demonstrating that the act of retrieving information from memory strengthens retention better than passive review. This research is highly relevant for teachers as it provides evidence that regular testing and quizzes should be viewed as assessment tools and as powerful revision techniques that actively improve student learning and long-term retention.

Research on retrieval practice and spaced learning 18 citations (Author, Year) in Dutch medical sciences students demonstrates effective strategies for preventing knowledge loss in ecologically valid educational settings, providing practical insights for curriculum design in higher education.

Donker et al. (2022)

This study investigated whether including questions from previous material in exams helps Dutch medical students retain knowledge over time through retrieval practice and spaced learning. The research is valuable for teachers because it demonstrates how strategically incorporating review questions into assessments can serve as an effective revision technique, preventing the natural decay of previously learned material while reinforcing long-term retention.

Recent developments in mobile-assisted vocabulary learning: a mini review of published studies focusing on digital flashcards 13 citations

Teymouri et al. (2024)

This review examines recent research on using mobile apps and digital flashcards for vocabulary learning, comparing their effectiveness to traditional study methods. Teachers will find this relevant as it provides evidence-based insights into how digital flashcard tools can be integrated into revision strategies, particularly for language learning and memorization tasks across various subjects.

Suartama et al. (2024)

This study explores how adding game-like elements to online case and project-based learning affects student engagement and academic performance. While focused on gamification, this research is relevant to teachers interested in revision techniques as it demonstrates how interactive and engaging formats can improve learning outcomes, suggesting that making revision activities more game-like could enhance their effectiveness.

Research on feedback in multiple-choice testing 451 citations (Author, Year) demonstrates that providing feedback enhances positive learning effects whilst simultaneously reducing the negative consequences typically associated with multiple-choice assessments, suggesting that strategic feedback implementation can improve the educational benefits of this common evaluation method.

Butler et al. (2008)

This research demonstrates that providing feedback after multiple-choice tests enhances the learning benefits while reducing potential negative effects of guessing incorrectly. This finding is crucial for teachers implementing testing as a revision technique, as it shows that the quality of feedback given after practice tests or quizzes significantly impacts how effective these activities are for student learning.

| Feature | Popular Methods (Re-reading, Highlighting) | Retrieval Practice | Spaced Learning | Interleaving& Elaboration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best For | Initial familiarity with content | Strengthening memory cues and exam performance | Long-term retention of information | Deep understanding and application |

| Key Strength | Feels productive and enjoyable | Actively strengthens memory through testing | Prevents forgetting over time | Builds connections between concepts |

| Limitation | Produces minimal lasting learning | More effortful than passive review | Requires planning and discipline | Can be cognitively demanding |

| Age Range | All ages (commonly misused) | GCSE and A-Level students | Secondary school and above | Advanced secondary and higher education |

Most students revise ineffectively, relying on techniques like re-reading and highlighting that feel productive but produce little lasting learning. Cognitive science has identified revision strategies that genuinely work: retrieval practice, spaced learning, interleaving, and elaboration. These techniques are more effort ful than passive review but far more effective. This guide explains why common revision approaches fail, what the evidence says works, and how teachers can help students adopt more effective revision habits before examinations.

The art and science of studying independently has helped us understand what activities enable students to effectively understand and recall important information. Within all of our articles on this site, we have tried to explain the fundamental principles of how we all think and learn. This article focuses in on the specific activities that students participate in when trying to prepare themselves for summative assessments.

For some of us, it has been three years since we last prepared students for public exams set by the exam boards. For those newer to the profession, this may be the first time you've been asked to deliver a four-hour study session the day before the GCSE Maths exam or experienced the marking that follows May half term, otherwise known as the essay-writing practice marathon. Do not worry: this article is here to help! In this post, we will move away from passive revision tactics and look at making the most out of revision periods with a more effective mix of learning techniques.

The most effective revision techniques according to cognitive science are recollection exercises, scheduled复习, 换底学习, 和 精要化思维 These active strategies require more effort than passive methods like re-reading but produce significantly better retention and exam performance. Students who use these evidence-based techniques consistently outperform those using traditional highlighting and note-taking methods.

Scientific studies have shown that if a revision strategy is enjoyable and rated effective by students, it is probably one of the least effective strategies they could be using! Focusing on quality rather than quantity will make a real difference to the amount of productive study time students can achieve, increase their motivation for revision, and reduce teachers' workload.

While students' motivation for revision is likely to be at its highest as they prepare for GCSEs and A-Levels, their method of revision may be letting them down. They are probably already doing short periods of revision, taking regular breaks, splitting large topics into bite-sized chunks, and using memory tricks such as mnemonics. These are all good approaches, but what they do with the manageable chunks of information during their short bursts of revision will make the difference between plateauing and exam success.

If a student uses a one-hour revision session to complete a short exam question, write an essay and then checks their understanding using the mark scheme, they will have gained far more that one hour than a student who spends two hours writing revision notes with a personal tutor or highlighting their way through revision guides.

how the theories and findings from cognitive science can improve our understanding of how students learn and therefore which revision techniques will be most effective for them.

Cognitive research shows that effective revision methods work by forcing the brain to actively retrieve information rather than passively review it. Methods like retrieval practice strengthen memory pathways and create multiple cues for accessing information during exams. Passive techniques like re-reading create an illusion of knowledge but fail to build the neural connections needed for long-term retention.

Learning results in a permanent change to a student's long-term memory. Information must first be processed by the short-term memory and then encoded into the long-term memory. Our short-term memory has a very limited capacity and duration, which means it can become overloaded quickly.

Common (and hopefully less common!) causes of cognitive overload:

Relieving pressure on the short-term memory, by either reducing exposure to redundant information or by presenting the same information to two different stores ( dual coding), we increase the likelihood of the information being successfully encoded to the long-term memory. This process requires repetition (e.g. Rote learning) or interacting with the new information in a meaningful way using a mix of learning techniques. Examples of this can include:

When new information is successfully encoded into the long-term memory, the next challenge is being able to retrieve this new knowledge when it is needed. Our long-term memory may have unlimited capacity and duration but this means that it can be difficult or impossible to remember a precise skill or fact when it is required. The long-term memory relies on cues to access the information we need; the more cues associated with a memory, the easier it is to retrieve it.

The purpose of revision is to strengthen memory retrieval pathways and ensure information can be accessed under exam conditions. Effective revision transforms surface-level recognition into deep understanding that students can apply in different contexts. Rather than simply refreshing memory, revision should actively reconstruct knowledge and identify gaps in understanding.

The goal of revision is to increase and strengthen the cues associated with prior learning so that the information can be readily available and retrieved when needed. This can include information about exam techniques, subject-specific key words, essay plans, dates, skills or facts. Every time we retrieve a piece of information from our long-term memory, we strengthen a cue associated with that piece of information as well as the cues associated with related pieces of information. Revision time can be used to increase the number of cues by completing activities that require prior learning to be used in multiple ways.

If revision techniques do not strengthen cues or increase the number of cues, they should be replaced by ones that do. Rereading or highlighting notes, copying out a mind map, using a text book to complete exam papers or study notes to support essay writing are unlikely to have a great impact on the cues used by the long-term memory. Active rather than passive retrieval is a factor in determining how successful a revision technique will be. A poor revision style might include simply rereading a page or rewriting (word for word) answers to an essay question.

Active revision strategies require students to do a lot of thinking. Learning anything new is hard work and students will need to be in the right frame of mind. The human brain requires information to be organised and structured in such a way that it's easier to retrieve. This is the result of hard thinking and there are no shortcuts or real memory tricks we can use for this.

Keep in mind that the goal of revision is to strengthen and increase the cues used by the long-term memory. Revision time should be focused on retrieving, and ideally using, the content that needs revision; this will build a deeper understanding of the topic being studied and make it easier to retrieve the information when it is needed.

Flash cards can be a great revision tool when used correctly: reading the question and then either speaking aloud or writing down their answer before turning the card over to reveal the answer. The danger of flash cards comes when students read the question and turn it over to read the answer and think 'I knew that'. They have not practiced retrieving the information and the process may also give them a false sense of confidence.

For GCSEs and A-Levels that are essay based subjects, there is no such thing as too much essay-writing practice, although the students may disagree! Open book essays are fine if the students need exam technique practice without worrying about the content, but in all other cases, closed book essay-writing practice will be more beneficial. It's fine for them to have study time beforehand to read through their notes or revision guides, but these should then be put away for students to practice retrieving the information while they complete the essay question.

Completing exam papers without notes, recreating mind maps or a list of key words from memory, having plenty of essay practice and spending 5-minute periods of free recall are all valid and effective revision techniques. And the best part: even if the information they recall isn't quite correct and the work isn't marked by a teacher, their memory for the correct information and related information will improve!

There are plenty of effective revision techniques available to students. To ensure their study time is most productive, they must be retrieving information. Scientific studies have shown that students prefer revision techniques that reconfirm their prior understanding, such as reading through revision notes, using flash cards incorrectly, or highlighting text. Retrieval can be uncomfortable, especially if students are revising a topic they find difficult, but reassure them that this means their revision technique is working.

What revision techniques might work for your students? We'll go into more detail shortly but you might want to consider:

Students should prioritise topics by identifying areas of weakness through practice tests and self-assessment rather than focusing on topics they find easiest. The most effective approach combines high-value topics that appear frequently in exams with personal knowledge gaps identified through retrieval practice. Teachers can help by providing topic weightings and diagnostic assessments to guide student choices.

The perfect revision timetable doesn't exist. I have created many revision timetables for my students over the years, but all they really need is periods of dedicated revision time and to spend that time revising the right topics. Students often need help identifying which topics they know well enough to revise less frequently and which topics require constant revision. Providing students with plenty of opportunities to show you their current understanding, probably through completing past papers, will allow you to focus their revision on the topics that need the most attention.

If students are using flash cards or study notes during their revision sessions, encourage them to organise the cards into three piles: topics that need revision every two or three days, topics that need revision once a week, and topics that need revision less frequently than once a fortnight. This will enable their revision time each day to be focused on the topics that need the most attention. For related approaches, explore Characteristics of Effective Learning: A Complete..

Teachers can implement evidence-based revision by building regular retrieval practice into lessons through low-stakes quizzing and spaced review of previous topics. Start by teaching students how to create effective flashcards and use techniques like the Leitner system for spaced repetition. Model these techniques explicitly and provide structured revision timetables that incorporate spacing and interleaving principles.

This is my favourite section of any article! I love thinking about how the findings from research can be applied to classroom practices.

How can cognitive science help our students to achieve exam success? There are so many ways, but I've narrowed it down to six revision techniques that are all supported by research and made them fit into a useful acronym for students: REVISE!

This should be the first consideration of any revision session. Encourage students to ask themselves 'does this method of revision require me to retrieve information from my long-term memory?' There are so many ways that students can retrieve information, even during a short period of independent study:

This revision technique is designed to strengthen the connections between different concepts in the long-term memory. Students should read through their study notes for one or two topics, put these notes away and try listing the similarities and differences between the two passages they have just read. This could also be done to compare two or more of the subjects they are studying.

Encourage students to gain a deeper understanding by asking themselves questions such as 'what if..?', 'why does..?' or 'how do we know..?'.

This refers to dual coding, but the acronym wouldn't work as well if it was REDISE!

Encourage students to use images and text to represent information in their study notes or flash cards. This will give them additional cues to help their long-term memory retrieve the content when they need it. You can also use this technique when you are presenting new information for the first time to make it more memorable.

Interleaving means moving between different topics during a revision session. Students will be more productive if they spend 20-30 minutes (at GCSE) or 30-40 minutes (at A-Level) revising a topic before moving on to a different one. They can alternate between two different topics during one revision session or work through topics from each of their subjects. Interleaving can also be used in the classroom by combining two topics together in a question or inserting a question from a previous topic into a low-stakes quiz.

Spacing revision sessions for one topic over two weeks is far more beneficial than spending the same amount of time revisingin just one day. Ideally, students should be revising (retrieving) new information soon after it has been learnt and then increasing the length of time between each subsequent retrieval.

A colleague in my school (who is exceptionally organised!) places each new topic she teaches into her planner one week and one month after she has taught it. She looks at the topics written in her planner each week and includes them in a low-stakes quiz, ensuring that every topic is revised in class at least twice.

Examples provide additional cues for our long-term memory. They can be used in class to improve students' understanding of abstract concepts and the list of examples can be added to for homework and revision. Encourage students to use some of their revision time to recreate lists of these examples.

Teachers should advise students to replace passive revision with active techniques: test yourself frequently, space out revision sessions, and mix different topics rather than blocking similar content. Emphasize that effective revision feels harder than re-reading but produces better results. Provide specific strategies like creating practice questions, teaching concepts to others, and using retrieval practice apps or flashcards.

The advice I will be giving my students during this revision season is simple: REVISE!

I will be reminding them about how our memory works and encouraging them to use the six techniques above to ensure that every minute they spend revising is time well spent.

I will also be telling them that revision should be deliberately difficult.

And finally: retrieve, retrieve, retrieve!

Key research includes Roediger and Butler's work on the testing effect, Bjork's studies on desirable difficulties, and Dunlosky's comprehensive review ranking revision techniques by effectiveness. These studies consistently show retrieval practice and distributed practice outperform massed practice and re-reading. The evidence base spans decades of cognitive psychology research across different age groups and subject areas.

The studies reviewed indicate that various active revision techniques, such as team-based learning, online practice tests, integrated revision and assessment methods, test question templates, and interactive computer-based systems, can significantly enhance student performance and learning efficiency during exam periods.

1. Adapting Team‐Based Learning Concepts Into an Effective Anatomy Revision Session

This study discusses the adaptation of team-based learning concepts into anatomy revision sessions. It emphasises the use of quizzes for retrieval practice and peer learning, which helps students understand topics better and reveals knowledge gaps through many questions in a short timeframe (Croker & Burgess, 2020).

2. JUST HOW MUCH PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT? USING AN ONLINE TEST AS A REVISION TOOLFOR STUDENTS

This paper explores the use of online practice tests as a revision tool for undergraduate business students. The study found that unlimited attempts at practice tests can significantly improve examination performance and reduce revision time (Bocij & Gautam, 2017).

3. Integral Revision, In Semester Examination and Evaluation of Content, II Technique

This paper presents the IRSIEC-II technique, which integrates revision, examination, and assessment using Internet of Things tools. The technique enhances active learning by allowing simultaneous revision and evaluation, leading to increased student learn ingrates compared to traditional methods (Mulla et al., 2021).

4. Testing in the Age of Active Learning: Test Question Templates Help to Align Activities and Assessments

This study introduces Test Question Templates (TQTs) to help align active learning activities with traditional exams. TQTs help students prepare for exams by generating various question formats, which enhances their readiness and understanding of the material (Crowther et al., 2020).

5. An interactive computer‐based revision aid

This paper discusses a computer-based revision system using multiple-choice questions. It tracks user performance and has been positively received by medical students, indicating its effectiveness in aiding revision (Stevens & Harris, 1977).

The most effective revision techniques are practice retrieval, timed复习, 分散练习, 和 扩展解释 These evidence-based strategies require more effort than passive methods but produce significantly better retention and exam performance compared to traditional highlighting and note-taking methods.

Highlighting and re-reading create an illusion of knowledge because they feel productive and enjoyable, but they fail to build the neural connections needed for long-term retention. These passive techniques don't force the brain to actively retrieve information, which means they produce minimal lasting learning despite students feeling confident about their progress.

Teachers can encourage students to replace passive review with active testing techniques such as completing practice exam questions, writing essays, and checking understanding using mark schemes. The key is ensuring students actively reconstruct knowledge rather than simply recognising information, which strengthens memory pathways and creates multiple cues for accessing information during exams.

Retrieval practice is most effective for GCSE and A-Level students, whilst spaced learning works well for secondary school students and above. Interleaving and elaboration are best suited for advanced secondary and higher education students, as these techniques can be cognitively demanding and require more sophisticated thinking skills.

The main challenges include students' resistance to more effortful techniques when passive methods feel easier and more enjoyable. Additionally, effective revision strategies like spaced learning require planning and discipline, whilst techniques like interleaving can be cognitively demanding and may initially feel less productive to students.

Students using ineffective techniques typically spend hours highlighting revision guides, writing lengthy notes, or repeatedly re-reading materials whilst feeling productive and confident. If revision methods are enjoyable and rated as effective by students, research suggests they are probably amongst the least effective strategies available.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into revision techniques that work: evidence-based strategies for students and its application in educational settings.

Test‐enhanced learning in medical education 576 citations

Larsen et al. (2008)

This paper examines how testing itself can enhance learning in medical education, demonstrating that the act of retrieving information from memory strengthens retention better than passive review. This research is highly relevant for teachers as it provides evidence that regular testing and quizzes should be viewed as assessment tools and as powerful revision techniques that actively improve student learning and long-term retention.

Research on retrieval practice and spaced learning 18 citations (Author, Year) in Dutch medical sciences students demonstrates effective strategies for preventing knowledge loss in ecologically valid educational settings, providing practical insights for curriculum design in higher education.

Donker et al. (2022)

This study investigated whether including questions from previous material in exams helps Dutch medical students retain knowledge over time through retrieval practice and spaced learning. The research is valuable for teachers because it demonstrates how strategically incorporating review questions into assessments can serve as an effective revision technique, preventing the natural decay of previously learned material while reinforcing long-term retention.

Recent developments in mobile-assisted vocabulary learning: a mini review of published studies focusing on digital flashcards 13 citations

Teymouri et al. (2024)

This review examines recent research on using mobile apps and digital flashcards for vocabulary learning, comparing their effectiveness to traditional study methods. Teachers will find this relevant as it provides evidence-based insights into how digital flashcard tools can be integrated into revision strategies, particularly for language learning and memorization tasks across various subjects.

Suartama et al. (2024)

This study explores how adding game-like elements to online case and project-based learning affects student engagement and academic performance. While focused on gamification, this research is relevant to teachers interested in revision techniques as it demonstrates how interactive and engaging formats can improve learning outcomes, suggesting that making revision activities more game-like could enhance their effectiveness.

Research on feedback in multiple-choice testing 451 citations (Author, Year) demonstrates that providing feedback enhances positive learning effects whilst simultaneously reducing the negative consequences typically associated with multiple-choice assessments, suggesting that strategic feedback implementation can improve the educational benefits of this common evaluation method.

Butler et al. (2008)

This research demonstrates that providing feedback after multiple-choice tests enhances the learning benefits while reducing potential negative effects of guessing incorrectly. This finding is crucial for teachers implementing testing as a revision technique, as it shows that the quality of feedback given after practice tests or quizzes significantly impacts how effective these activities are for student learning.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/revision-techniques-a-teachers-guide#article","headline":"Revision Techniques That Work: Evidence-Based Strategies for Students","description":"Discover revision strategies backed by cognitive science. Learn why some techniques work better than others and how to teach students effective revision...","datePublished":"2022-04-24T15:34:04.207Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/revision-techniques-a-teachers-guide"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a2574bde78487fd87ec32_696a256ea2d69d276dde220a_revision-techniques-a-teachers-guide-illustration.webp","wordCount":3610},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/revision-techniques-a-teachers-guide#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Revision Techniques That Work: Evidence-Based Strategies for Students","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/revision-techniques-a-teachers-guide"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/revision-techniques-a-teachers-guide#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the most effective revision techniques according to cognitive science research?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The most effective revision techniques are retrieval practice, spaced learning, interleaving, and elaboration. These evidence-based strategies require more effort than passive methods but produce significantly better retention and exam performance compared to traditional highlighting and note-taking"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why do popular revision methods like highlighting and re-reading fail to produce lasting learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Highlighting and re-reading create an illusion of knowledge because they feel productive and enjoyable, but they fail to build the neural connections needed for long-term retention. These passive techniques don't force the brain to actively retrieve information, which means they produce minimal last"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers help students implement retrieval practice effectively in their revision?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can encourage students to replace passive review with active testing techniques such as completing practice exam questions, writing essays, and checking understanding using mark schemes. The key is ensuring students actively reconstruct knowledge rather than simply recognising information, "}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What age groups are these evidence-based revision techniques most suitable for?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Retrieval practice is most effective for GCSE and A-Level students, whilst spaced learning works well for secondary school students and above. Interleaving and elaboration are best suited for advanced secondary and higher education students, as these techniques can be cognitively demanding and requi"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the main challenges teachers face when encouraging students to adopt these evidence-based revision methods?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The main challenges include students' resistance to more effortful techniques when passive methods feel easier and more enjoyable. Additionally, effective revision strategies like spaced learning require planning and discipline, whilst techniques like interleaving can be cognitively demanding and ma"}}]}]}