Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs: Understanding Student Motivation

Explore Maslow's hierarchy of needs in education. Learn how physiological, safety, belonging, esteem, and self-actualisation needs impact student motivation.

Explore Maslow's hierarchy of needs in education. Learn how physiological, safety, belonging, esteem, and self-actualisation needs impact student motivation.

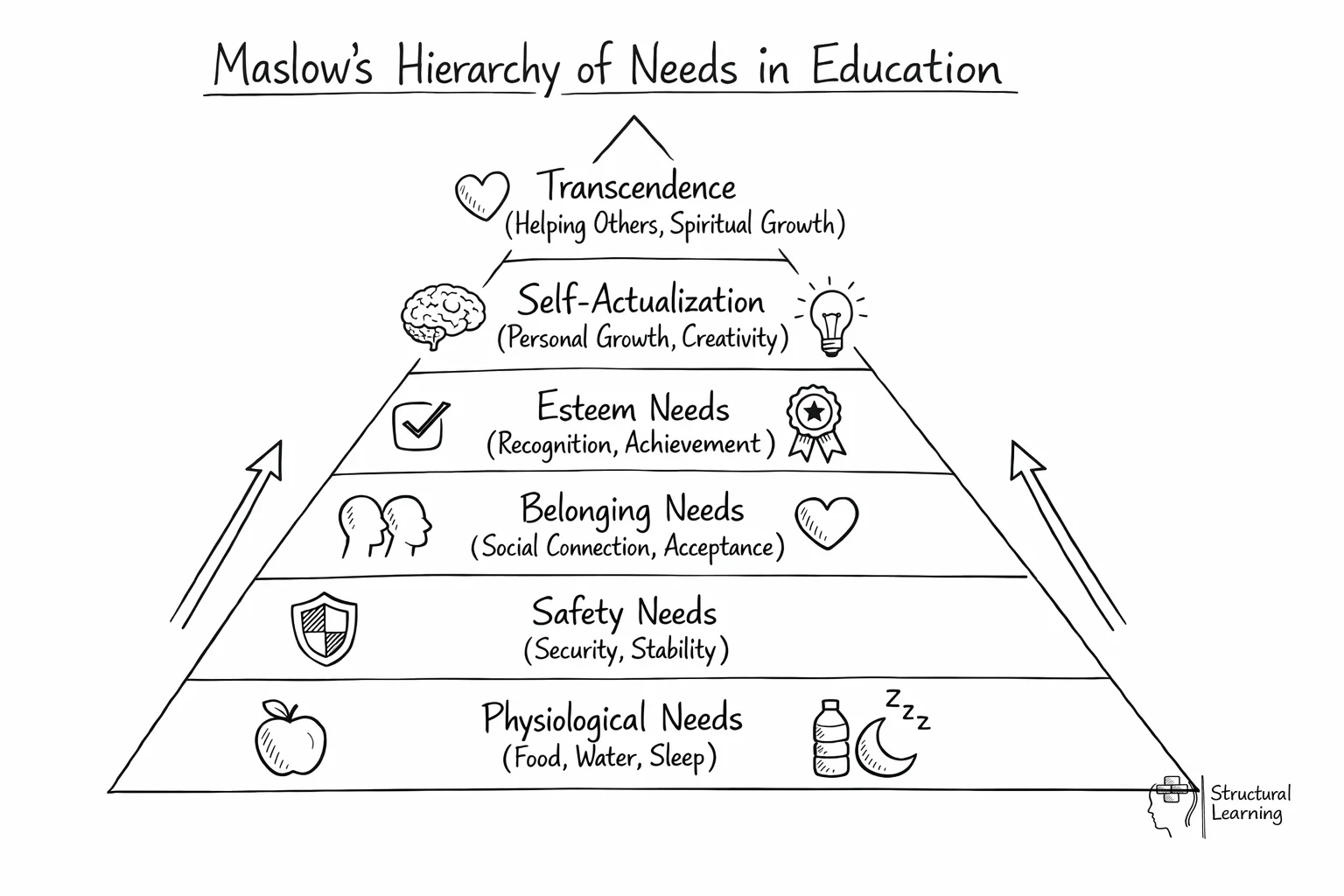

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is a psychological theory that arranges human needs in a pyramid structure, from basic physiological needs at the bottom to self-actualization at the top. The theory suggests that people must satisfy lower-level needs like food and safety before pursuing higher-level needs like belonging and personal growth. This framework helps educators understand why students cannot focus on learning when their basic needs are unmet.

| Stage/Level | Age Range | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Needs | All ages | Basic survival needs: food, water, sleep, shelter | Students cannot focus on learning when hungry, tired, or physically uncomfortable |

| Safety Needs | All ages | Physical and emotional security, stability, protection from harm | Students need safe classroom environments and predictable routines to learn effectively |

| Belonging Needs | All ages | Social connection, friendship, love, acceptance, group membership | Students learn better when they feel includedand connected to peers and teachers |

| Esteem Needs | All ages | Recognition, respect, achievement, confidence, self-worth | Students need positive feedback and opportunities to demonstrate competence |

| Self-Actualization | All ages | Realizing full potential, personal growth, creativity, fulfilment | Students pursue learning for its own sake and seek challenging, meaningful work |

| Transcendence | All ages | Experiences beyond the self, spiritual growth, helping others | Students engage in service learning and seek to make positive contributions |

Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs remains one of the most recognisable theories in psychology. The pyramid model suggests human needs are arranged hierarchically: physiological needs must be met before safety needs, which must be met before belonging needs, and so on to self-actualisation. For educators, Maslow's theory provides a framework for understanding why students cannot focus on learning when hungry, anxious, or excluded. While the rigid hierarchy has been questioned, the core insight that basic needs affect higher-level functioning remains valuable.

The foundational layer of the pyramid addresses our most fundamental physiological requirements, these are the basic human needs like food, water, and sleep. It is at this proximate level where the self-protective goal is paramount, aligning with evolutionary psychology that recognises the urgency of survival and reproductive goals.

As one ascends the hierarchy needs of Maslow, each tier represents a developmental level with corresponding needs. Following the satisfaction of basic necessities, safety needs emerge, followed by social motives, our intrinsic desire for belonging and affection. Esteem needs, the penultimate tier, speak to our need for recognition and self-respect.

At the pinnacle lies self-actualisation needs, which is the drive to realise one's fullest potential, a concept that Maslow later expanded with a sixth level to encompass transcendent experiences.

This hierarchical approach provides a framework for understanding the myriad of factors that motivate behaviour, casting hierarchy in light of both personal growth and the broader spectrum of evolutionary approach. In subsequent sections of this article, we will examine into the historical context and the multifaceted implications of Maslow's hierarchy of motives, exploring how they resonate within educational settings and beyond.

The pyramid of need Maslow created is less about climbing to the top and more about the journey of becoming.

The three key takeaways from this introduction are:

While Maslow's hierarchy offers valuable insights, it is not without its criticisms. One common critique is the rigid hierarchical structure. Research suggests that people may pursue multiple needs simultaneously, rather than strictly adhering to the pyramid's sequential progression. For example, a student facing food insecurity might still strive for academic achievement and social connection.

Another limitation is the theory's cultural bias. Maslow's research primarily focused on Western, individualistic societies. In collectivist cultures, belonging and community needs may take precedence over individual self-actualisation. Despite these criticisms, Maslow's hierarchy remains a useful framework for educators to consider the diverse needs and motivations of their students.

Cultural bias represents another significant limitation of Maslow's framework. The hierarchy was developed primarily through observations of Western, individualistic societies, yet many students come from collectivistic cultures where community belonging might take precedence over individual self-actualisation. Research by Geert Hofstede and others has demonstrated that cultural values significantly influence motivation patterns, suggesting educators should adapt their understanding of student needs accordingly.

Additionally, the linear progression implied by the hierarchy doesn't always reflect reality in educational settings. Students may simultaneously work towards goals at multiple levels, or may temporarily regress when facing new challenges. For instance, a confident Year 10 student might suddenly struggle with belonging needs when transitioning to a new school, even whilst maintaining strong academic performance.

The theory also lacks consideration for neurodivergent learners, whose motivational patterns may differ significantly from neurotypical peers. Students with autism, ADHD, or other conditions might prioritise predictability and routine over social belonging, or require different approaches to building self-esteem. Practical strategies must therefore be flexible and individualised rather than following a prescribed hierarchy, recognising that effective classroom environments support multiple pathways to learning and growth.

So, how can educators apply Maslow's hierarchy in the classroom? Here are some practical strategies:

Self-actualisation in educational settings involves helping students discover their unique potential and pursue meaningful learning experiences. Provide choice in learning topics where possible, encourage creative problem-solving, and support students in setting personal learning goals. Consider implementing project-based learning opportunities that allow students to explore their interests whilst meeting curriculum objectives. Encourage reflection through learning journals or portfolio work that helps students recognise their growth and development.

Creating a hierarchy-aware classroom environment means regularly assessing which level of needs your students are operating from on any given day. A student struggling with food insecurity cannot engage with higher-level learning until their basic needs are acknowledged. Develop simple check-in systems, such as mood meters or brief morning conversations, to gauge where students are emotionally and physically. This awareness allows you to adjust your teaching approach accordingly and connect students with appropriate support services when needed.

Remember that students may move between different levels of the hierarchy throughout a single day or term. Flexibility in your approach and maintaining a toolkit of strategies addressing each level will ensure you can respond effectively to your students' varying needs whilst maintaining focus on learning outcomes.

Maslow's hierarchy manifests distinctly in educational settings, with each level presenting recognisable patterns of student behaviour and engagement. At the physiological level, hungry or tired students struggle to concentrate, often appearing restless or disengaged during lessons. Safety needs emerge when students feel anxious about bullying, academic failure, or unstable home situations, leading to withdrawn behaviour or difficulty taking learning risks. Belongingness becomes evident through students' desire for peer acceptance and teacher connection, whilst esteem needs drive competition for recognition and fear of public mistakes.

The self-actualisation level, though less common in younger learners, appears when students pursue learning for pure curiosity rather than external rewards. Research by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan supports this progression, demonstrating that intrinsic motivation flourishes only when basic psychological needs are satisfied. In practice, a student preoccupied with friendship conflicts (belongingness) cannot fully engage with challenging mathematical concepts, whilst another worried about parental reactions to grades (safety) may avoid participating in class discussions.

Understanding these manifestations enables educators to identify which level individual students are operating from and adjust their approach accordingly. Rather than assuming all students are ready for higher-order thinking, effective teachers first ensure foundational needs are addressed through classroom routines, supportive relationships, and inclusive learning environments.

Recognising when students' fundamental needs remain unmet requires careful observation of both behavioural patterns and academic performance indicators. Students experiencing physiological deprivation may display restlessness, difficulty concentrating, or frequent absence from lessons. Those lacking safety and security often exhibit anxiety, withdrawal from classroom discussions, or reluctance to take academic risks. Meanwhile, students with unmet belonging needs typically demonstrate social isolation, reluctance to participate in group activities, or attention-seeking behaviours that disrupt learning environments.

Academic warning signs frequently manifest alongside behavioural indicators, creating comprehensive patterns that inform teaching practice. Sudden declines in work quality, incomplete assignments, or apparent disengagement from previously enjoyed subjects often signal underlying needs deficits. Chronic underachievement despite apparent ability may indicate that basic needs are consuming cognitive resources required for learning. Educational research consistently demonstrates that stressed students struggle to access higher-order thinking skills when fundamental concerns remain unaddressed.

Effective identification requires systematic observation rather than isolated incident analysis. Maintain brief records of concerning behaviours, noting frequency and context to distinguish between temporary difficulties and persistent needs deficits. Regular check-ins with students, collaborative discussions with colleagues, and communication with families provide essential perspectives for accurate assessment. This comprehensive approach enables targeted interventions that address root causes rather than surface symptoms.

Creating a needs-supportive classroom environment requires deliberate attention to how physical space, social dynamics, and instructional practices address students' hierarchical needs. Physical safety forms the foundation through clear sightlines, accessible exits, and well-organised learning materials that reduce anxiety and cognitive overload. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates how cluttered, chaotic environments can overwhelm working memory, preventing students from engaging with learning content effectively.

The psychological safety that enables higher-order learning emerges through predictable routines, consistent behavioural expectations, and classroom cultures that celebrate mistakes as learning opportunities. Belonging needs flourish when educators create multiple pathways for student connection, from collaborative learning structures to culturally responsive teaching practices that honour diverse backgrounds and experiences.

Supporting esteem and self-actualisation requires balancing challenge with support through differentiated instruction and authentic assessment practices. Provide regular opportunities for student choice and voice in learning activities, whilst maintaining scaffolds that ensure success. Display student work proudly, offer specific feedback that focuses on growth rather than comparison, and create classroom roles that allow every student to contribute meaningfully to the learning community.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs offers a valuable framework for understanding student motivation and creating a supportive learning environment. While the theory is not without its limitations, it reminds educators that students' basic needs must be met before they can fully engage in learning. By addressing students' physiological, safety, belonging, esteem, and self-actualisation needs, educators can helps them to reach their full potential.

Ultimately, understanding and applying Maslow's hierarchy of needs is not just about improving academic outcomes; it's about developing the complete development of each student, supporting them to become confident, compassionate, and contributing members of society.

The practical application of Maslow's hierarchy requires a systematic approach that can be integrated into daily classroom routines. Simple strategies such as maintaining consistent meal times, establishing clear behavioural expectations, and creating opportunities for peer collaboration address multiple levels of the hierarchy simultaneously. For instance, a morning check-in circle not only provides safety and belonging but also builds self-esteem through active listening and validation of each student's contributions.

Professional development in this area benefits from collaborative reflection among teaching staff. Regular team discussions about student needs, sharing of successful interventions, and collective problem-solving strengthen the whole-school approach to student wellbeing. When educators work together to identify students who may be struggling with basic needs, they can implement targeted support strategies more effectively whilst maintaining the learning momentum for all students.

The evidence consistently demonstrates that classrooms grounded in Maslow's principles show improved attendance, reduced behavioural incidents, and enhanced academic progress. These outcomes reinforce the fundamental truth that addressing students' hierarchical needs is not separate from academic instruction but rather the foundation upon which meaningful learning occurs in educational contexts.

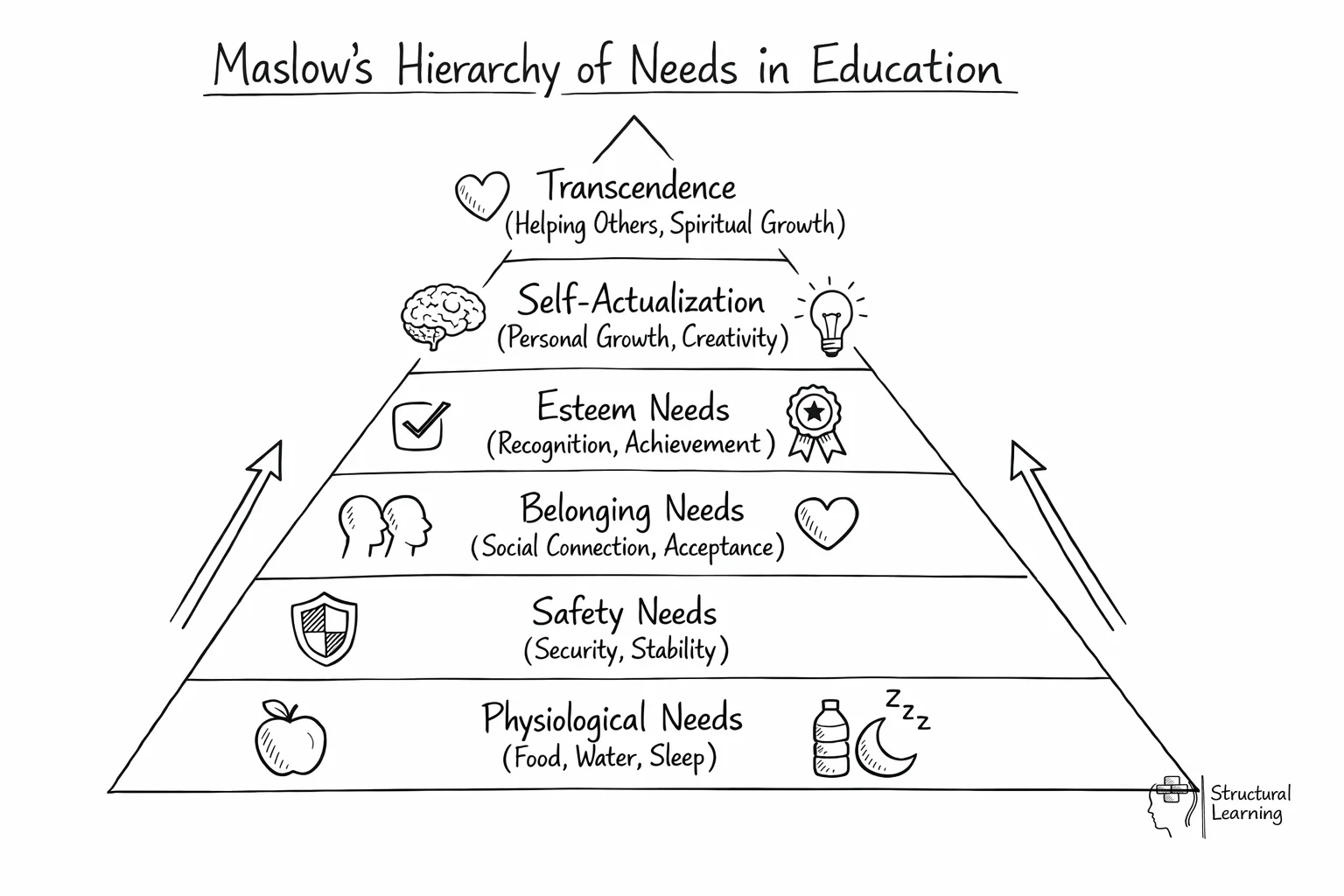

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is a psychological theory that arranges human needs in a pyramid structure, from basic physiological needs at the bottom to self-actualization at the top. The theory suggests that people must satisfy lower-level needs like food and safety before pursuing higher-level needs like belonging and personal growth. This framework helps educators understand why students cannot focus on learning when their basic needs are unmet.

| Stage/Level | Age Range | Key Characteristics | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Needs | All ages | Basic survival needs: food, water, sleep, shelter | Students cannot focus on learning when hungry, tired, or physically uncomfortable |

| Safety Needs | All ages | Physical and emotional security, stability, protection from harm | Students need safe classroom environments and predictable routines to learn effectively |

| Belonging Needs | All ages | Social connection, friendship, love, acceptance, group membership | Students learn better when they feel includedand connected to peers and teachers |

| Esteem Needs | All ages | Recognition, respect, achievement, confidence, self-worth | Students need positive feedback and opportunities to demonstrate competence |

| Self-Actualization | All ages | Realizing full potential, personal growth, creativity, fulfilment | Students pursue learning for its own sake and seek challenging, meaningful work |

| Transcendence | All ages | Experiences beyond the self, spiritual growth, helping others | Students engage in service learning and seek to make positive contributions |

Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs remains one of the most recognisable theories in psychology. The pyramid model suggests human needs are arranged hierarchically: physiological needs must be met before safety needs, which must be met before belonging needs, and so on to self-actualisation. For educators, Maslow's theory provides a framework for understanding why students cannot focus on learning when hungry, anxious, or excluded. While the rigid hierarchy has been questioned, the core insight that basic needs affect higher-level functioning remains valuable.

The foundational layer of the pyramid addresses our most fundamental physiological requirements, these are the basic human needs like food, water, and sleep. It is at this proximate level where the self-protective goal is paramount, aligning with evolutionary psychology that recognises the urgency of survival and reproductive goals.

As one ascends the hierarchy needs of Maslow, each tier represents a developmental level with corresponding needs. Following the satisfaction of basic necessities, safety needs emerge, followed by social motives, our intrinsic desire for belonging and affection. Esteem needs, the penultimate tier, speak to our need for recognition and self-respect.

At the pinnacle lies self-actualisation needs, which is the drive to realise one's fullest potential, a concept that Maslow later expanded with a sixth level to encompass transcendent experiences.

This hierarchical approach provides a framework for understanding the myriad of factors that motivate behaviour, casting hierarchy in light of both personal growth and the broader spectrum of evolutionary approach. In subsequent sections of this article, we will examine into the historical context and the multifaceted implications of Maslow's hierarchy of motives, exploring how they resonate within educational settings and beyond.

The pyramid of need Maslow created is less about climbing to the top and more about the journey of becoming.

The three key takeaways from this introduction are:

While Maslow's hierarchy offers valuable insights, it is not without its criticisms. One common critique is the rigid hierarchical structure. Research suggests that people may pursue multiple needs simultaneously, rather than strictly adhering to the pyramid's sequential progression. For example, a student facing food insecurity might still strive for academic achievement and social connection.

Another limitation is the theory's cultural bias. Maslow's research primarily focused on Western, individualistic societies. In collectivist cultures, belonging and community needs may take precedence over individual self-actualisation. Despite these criticisms, Maslow's hierarchy remains a useful framework for educators to consider the diverse needs and motivations of their students.

Cultural bias represents another significant limitation of Maslow's framework. The hierarchy was developed primarily through observations of Western, individualistic societies, yet many students come from collectivistic cultures where community belonging might take precedence over individual self-actualisation. Research by Geert Hofstede and others has demonstrated that cultural values significantly influence motivation patterns, suggesting educators should adapt their understanding of student needs accordingly.

Additionally, the linear progression implied by the hierarchy doesn't always reflect reality in educational settings. Students may simultaneously work towards goals at multiple levels, or may temporarily regress when facing new challenges. For instance, a confident Year 10 student might suddenly struggle with belonging needs when transitioning to a new school, even whilst maintaining strong academic performance.

The theory also lacks consideration for neurodivergent learners, whose motivational patterns may differ significantly from neurotypical peers. Students with autism, ADHD, or other conditions might prioritise predictability and routine over social belonging, or require different approaches to building self-esteem. Practical strategies must therefore be flexible and individualised rather than following a prescribed hierarchy, recognising that effective classroom environments support multiple pathways to learning and growth.

So, how can educators apply Maslow's hierarchy in the classroom? Here are some practical strategies:

Self-actualisation in educational settings involves helping students discover their unique potential and pursue meaningful learning experiences. Provide choice in learning topics where possible, encourage creative problem-solving, and support students in setting personal learning goals. Consider implementing project-based learning opportunities that allow students to explore their interests whilst meeting curriculum objectives. Encourage reflection through learning journals or portfolio work that helps students recognise their growth and development.

Creating a hierarchy-aware classroom environment means regularly assessing which level of needs your students are operating from on any given day. A student struggling with food insecurity cannot engage with higher-level learning until their basic needs are acknowledged. Develop simple check-in systems, such as mood meters or brief morning conversations, to gauge where students are emotionally and physically. This awareness allows you to adjust your teaching approach accordingly and connect students with appropriate support services when needed.

Remember that students may move between different levels of the hierarchy throughout a single day or term. Flexibility in your approach and maintaining a toolkit of strategies addressing each level will ensure you can respond effectively to your students' varying needs whilst maintaining focus on learning outcomes.

Maslow's hierarchy manifests distinctly in educational settings, with each level presenting recognisable patterns of student behaviour and engagement. At the physiological level, hungry or tired students struggle to concentrate, often appearing restless or disengaged during lessons. Safety needs emerge when students feel anxious about bullying, academic failure, or unstable home situations, leading to withdrawn behaviour or difficulty taking learning risks. Belongingness becomes evident through students' desire for peer acceptance and teacher connection, whilst esteem needs drive competition for recognition and fear of public mistakes.

The self-actualisation level, though less common in younger learners, appears when students pursue learning for pure curiosity rather than external rewards. Research by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan supports this progression, demonstrating that intrinsic motivation flourishes only when basic psychological needs are satisfied. In practice, a student preoccupied with friendship conflicts (belongingness) cannot fully engage with challenging mathematical concepts, whilst another worried about parental reactions to grades (safety) may avoid participating in class discussions.

Understanding these manifestations enables educators to identify which level individual students are operating from and adjust their approach accordingly. Rather than assuming all students are ready for higher-order thinking, effective teachers first ensure foundational needs are addressed through classroom routines, supportive relationships, and inclusive learning environments.

Recognising when students' fundamental needs remain unmet requires careful observation of both behavioural patterns and academic performance indicators. Students experiencing physiological deprivation may display restlessness, difficulty concentrating, or frequent absence from lessons. Those lacking safety and security often exhibit anxiety, withdrawal from classroom discussions, or reluctance to take academic risks. Meanwhile, students with unmet belonging needs typically demonstrate social isolation, reluctance to participate in group activities, or attention-seeking behaviours that disrupt learning environments.

Academic warning signs frequently manifest alongside behavioural indicators, creating comprehensive patterns that inform teaching practice. Sudden declines in work quality, incomplete assignments, or apparent disengagement from previously enjoyed subjects often signal underlying needs deficits. Chronic underachievement despite apparent ability may indicate that basic needs are consuming cognitive resources required for learning. Educational research consistently demonstrates that stressed students struggle to access higher-order thinking skills when fundamental concerns remain unaddressed.

Effective identification requires systematic observation rather than isolated incident analysis. Maintain brief records of concerning behaviours, noting frequency and context to distinguish between temporary difficulties and persistent needs deficits. Regular check-ins with students, collaborative discussions with colleagues, and communication with families provide essential perspectives for accurate assessment. This comprehensive approach enables targeted interventions that address root causes rather than surface symptoms.

Creating a needs-supportive classroom environment requires deliberate attention to how physical space, social dynamics, and instructional practices address students' hierarchical needs. Physical safety forms the foundation through clear sightlines, accessible exits, and well-organised learning materials that reduce anxiety and cognitive overload. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates how cluttered, chaotic environments can overwhelm working memory, preventing students from engaging with learning content effectively.

The psychological safety that enables higher-order learning emerges through predictable routines, consistent behavioural expectations, and classroom cultures that celebrate mistakes as learning opportunities. Belonging needs flourish when educators create multiple pathways for student connection, from collaborative learning structures to culturally responsive teaching practices that honour diverse backgrounds and experiences.

Supporting esteem and self-actualisation requires balancing challenge with support through differentiated instruction and authentic assessment practices. Provide regular opportunities for student choice and voice in learning activities, whilst maintaining scaffolds that ensure success. Display student work proudly, offer specific feedback that focuses on growth rather than comparison, and create classroom roles that allow every student to contribute meaningfully to the learning community.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs offers a valuable framework for understanding student motivation and creating a supportive learning environment. While the theory is not without its limitations, it reminds educators that students' basic needs must be met before they can fully engage in learning. By addressing students' physiological, safety, belonging, esteem, and self-actualisation needs, educators can helps them to reach their full potential.

Ultimately, understanding and applying Maslow's hierarchy of needs is not just about improving academic outcomes; it's about developing the complete development of each student, supporting them to become confident, compassionate, and contributing members of society.

The practical application of Maslow's hierarchy requires a systematic approach that can be integrated into daily classroom routines. Simple strategies such as maintaining consistent meal times, establishing clear behavioural expectations, and creating opportunities for peer collaboration address multiple levels of the hierarchy simultaneously. For instance, a morning check-in circle not only provides safety and belonging but also builds self-esteem through active listening and validation of each student's contributions.

Professional development in this area benefits from collaborative reflection among teaching staff. Regular team discussions about student needs, sharing of successful interventions, and collective problem-solving strengthen the whole-school approach to student wellbeing. When educators work together to identify students who may be struggling with basic needs, they can implement targeted support strategies more effectively whilst maintaining the learning momentum for all students.

The evidence consistently demonstrates that classrooms grounded in Maslow's principles show improved attendance, reduced behavioural incidents, and enhanced academic progress. These outcomes reinforce the fundamental truth that addressing students' hierarchical needs is not separate from academic instruction but rather the foundation upon which meaningful learning occurs in educational contexts.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs#article","headline":"Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs: Understanding Student Motivation","description":"Explore Maslow's hierarchy of needs and its implications for education. Learn how physiological, safety, belonging, esteem, and self-actualisation needs...","datePublished":"2022-11-14T16:39:15.773Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/695266184bcc85b64744eabe_695266166d94861f1e15e3a0_maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-infographic.webp","wordCount":4374},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs: Understanding Student Motivation","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs"}]}]}