Cultural Capital in Education: Understanding and Building Student Advantage

Explore Bourdieu's cultural capital theory and its impact on education. Learn how schools can build cultural capital to reduce inequality and boost achievement.

Explore Bourdieu's cultural capital theory and its impact on education. Learn how schools can build cultural capital to reduce inequality and boost achievement.

| Examples (This IS Cultural Capital) | Non-Examples (This is NOT Cultural Capital) |

|---|---|

| Understanding that "the tube" refers to London's subway system, which helps students comprehend geography texts and travel narratives | Having expensive school supplies or the latest technology (this is economic capital, not cultural knowledge) |

| Knowing what a "dress circle" is in a theatre context, enabling students to solve math problems about ticket pricing | Being naturally intelligent or having high IQ (this is human capital, not culturally acquired knowledge) |

| Familiarity with museums, libraries, and cultural institutions that allows students to navigate these spaces confidently for research | Simply taking students on museum trips without teaching them how to engage with or decode the experience |

| Understanding social codes like how to write formal emails to teachers or participate in academic discussions | Having many friends or social connections (this is social capital, not cultural knowledge and competencies) |

The establishment of a new inspection framework from Ofstedin 2019, provided some major changes to how schools are inspected and how their quality is assured. They included an expectation that ‘cultural capital’ be inspected. Because therefore, schools now have to introduce this term to their whole school policy agenda and implement whole school strategies to address cultural capital gaps.

Recently, I overheard a conversation with a Geography teacher and a student who was questioning why boys are out at sea, 24 hours, 7 days a week. Similarly, a conversation with a Maths teacher and a student about what a dress circle is and how this is related to a theatre and their practice question on prices of seats. In addition, a colleague also explained the confusion of a student when they explained their recent journey on the tube and on the underground, which followed with questions about why their teacher was apparently in a tube, underground and using it to get from place to place.

When referring to cultural capital, there is a wide range of theories. Is it referring to social capital or is it referring to economic capital and human capital? It is more specifically related to forms of capital with reference to economic capital and social mobility or is it, instead, more to do with class differences, class inequalities, someone's social network, forms of knowledge and accumulation of knowledge? Some may say that cultural capital refers to childhood education, arts activities leisure activities affecting cultural competence. However, others may say that the body of knowledge on cultural capital theory is too broad in one definition.

In this article, we aim to establish the range of definitions of cultural capital by considering the idea of capital and cultural capital from different perspectives. We then aim to consider what Ofsted say about cultural capital before considering what this means for senior leaders, middle leaders and classroom practitioners.

Cultural capital was first introduced by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu in the 1970s to explain how social class advantages are passed through families via knowledge, skills, and cultural experiences. The concept gained prominence in UK education after Ofsted's 2019 framework made it a requirement for school inspections. This shift required schools to actively address cultural knowledge gaps that affect student achievement.

Bourdieu? Marx? Arnold? If you were a reader of English Literature or an Historian you might be familiar with the idea of ‘high and low’ culture and the idea of “the best which has been thought and said” (Arnold, 1875, p.10) which often seems to imply, whether right or wrong, that Shakespeare and Mozart and museum visits, not the integration of hip hop culture or vernacular cultures, should be generally written into the curriculum. The idea of cultural capital, however, if you are a sociologist, will be associated with Pierre Bourdieu (1977; 1984; 1986) or Marx (1967) and has more to do with power and the alienation of the working classes through certain types of ‘cultural capital’ than it has to do with maintaining what Matthew Arnold phrased “the best which that has been thought and said” (Arnold, 1875, p.10).

Neither the National Curriculum document (DfE, 2014) nor Ofsted (2019) offer elaboration on this definition in terms of criteria of Ofsted inspections, but simply state that they will be inspecting whether “leaders construct a curriculum [..] designed to give all learners [..] the knowledge and cultural capital they need to s ucceed in life” (Ofsted, 2019, p.9).

Pierre Bourdieu

The term cultural capital originates in the work of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (Bourdieu, 1977; 1984; 1986). For Bourdieu (1977; 1984; 1986), cultural capital is specifically linked to social class and acquisition of cultural capital. Bourdieu (1986) says that it “can be acquired, to a varying extent, depending on the period, the society, and the social class” (p.245). It is, therefore, dependent on the upbringing of an individual and the influence their social class has on this.

Bourdieu (1977) also refers to the development of an individual’s habitus, which has links to both the external wealth of an individual as well as to embodied forms of cultural capital which might arise from grammar schooling, faith-based schooling or independent schooling.

E. D. Hirsch Jr. Views cultural capital as the essential knowledge and vocabulary that all students need to succeed academically, regardless of their background. He argues that schools should explicitly teach this shared cultural literacythrough a knowledge-rich curriculum. This approach focuses on closing achievement gaps by ensuring all students have access to the same foundational cultural references.

Hirsch (1987), too, in his work on cultural literacy, proposed that there are certain kinds of knowledge that all individuals should have access to. In short, he says “To be culturally literate is to possess the basic information needed to thrive in the modern world” (Hirsch, 1987, p.12). This implies the requirement of a bedrock of essential knowledge to succeed in society. Reay (2017) points out that the conflation of Bourdieu’s concept (not necessarily to do with knowledge or, explicitly, the curriculum) and Hirsch’s idea of cultural literacy (which is to do with types of knowledge), is one of the most unhelpful aspects of Ofsted’s mis-definition of the term in their own policy documents (Reay, 2017).

Hirsch’s (1987) United States-based work on cultural literacy suggests that all individuals need to acquire essential, basic knowledge but he also says that “Children also need to understand elements of our literary and mythic heritage that are often alluded to without explanation” (Hirsch 1987, p.30). This means that when individuals hear, or interact with, names of multi-cultural mythic characters, characters in literature, art and music from across the world (Hirsch, 1987) they also need to be given the ‘social codes’ which enable them to read them (Hirsch, 1987). Lacking this, many will engage less well with and comprehend less about and from them. At worst further learning then becomes “increasingly toilsome, unproductive and humiliating” (Hirsch, 1987, p.28) particular if the social codes offered to them open out worlds which contradict the home habitus in which they are embedded from birth. The likelihood is that they will, then, at this point, give up trying at all. Hirsch suggest that “the most straightforward antidote to deprivation is to make the es sen tial information more readily available inside the schools.” (Hirsch, 1987, p.24).

Hirsch (1987), like Arnold, suggests that “literate culture has become the common currency for social and economic exchange in our democracy, and the only available ticket to full citizenship” (p.22) Equality of opportunity, Hirsch(1987) suggests, is available to all if they have this shared cultural literacy because “share d background knowledge [enables them] to communicate effectively with everyone else” (p.32).

Accessing the curriculum has to be the prime motivator in developing cultural capital because, if you cannot access, it how are you ever going to understand it, let alone be socially mobile within its structures?

In more recent terms

Many other academics also see a link between social privilege (Mohr and DiMaggio, 1995) and academic achievement in schools. DiMaggio (1982) was one of the recent academics to consider a possible relationship between cultural capital and educational achievement and Bennett et al. (2009) produced a comprehensive analysis of the work of Bourdieu and cultural capital. In their work, they suggest that “Those parents equipped with cultural capital are able to drill their children in the cultural forms that predispose them to perform well in the educational system” (Bennett et al., 2009, p.13).

For Ofsted, the definition of cultural capital is:

“the essential knowledge that pupils need to be educated citizens, introducing the finest that has been conceived achievement” (DfE, 2014, p.5).

The extent to which classroom teachers, middle or senior leaders are familiar with this idea, in the form it has entered education, would depend on how many had either studied or become in other ways acquainted with the mixture of ideas in this definition, in either first degree, initial teacher or other training.

So, with this working definition of cultural capital from the Department for Education, what are some of the misconceptions surrounding cultural capital and what could this mean for practitioners in the classroom, middle and senior leaders?

This exemplifies two ideas. Firstly, Matthew Arnold’s (1875) idea surrounding “the best which has been thought and said” (p.10) and, secondly, the idea that cultural literacy (Hirsch, 1977), a form of knowledge, is needed to acquire it. This is very different from both Marx and Bourdieu’s socially (semi) deterministic view of cultural capital. It suggests, for instance, that just ‘knowing about’ the idea of cultural literacy (explicit curriculum) is not as important as also ‘learning from’ it (implicit curriculum).

For example, by experiencing so called ‘high culture’ at first hand we validate different cultures (home or family influence) both implicitly and explicitly. Through assemblies, by introducing books or new Information Technology resources, such as iPads, into all schools, we are also both implicitly and explicitly insisting that those from disadvantaged backgrounds should have equal access to all sources of culture, not just the more limited ones they may experience at home.

Cultural knowledge is skewed because middle-class students often arrive at school with experiences and vocabulary that align with academic expectations, while working-class students may lack exposure to these references. Teachers unconsciously assume all students understand concepts like 'the tube' or 'dress circle,' creating hidden barriers to learning. This inequality perpetuates achievement gaps when schools fail to explicitly teach the cultural codes embedded in their curriculum.

It would be reasonable to suggest that many teachers may associate the acquisition of ‘knowing’ with acquiring cultural capital, without deeply understanding how. For Marx and Bourdieu, the ability to know is already skewed, in schools, by the curriculum’s own content and by pupils’ prior experience (habitus). Therefore, as a result, they do not currently understand that more sophisticated targeting, throughout both implicit and explicit curriculum, would be needed to truly implement Ofsted’s idea of ‘cultural capital.’

There is a three-pronged approach here involving:

1. Senior Leaders, Higher-level plan

2. Middle Leaders, Knowing your curriculum and supporting department colleagues

3. Classroom practitioners - Supporting students

It is not sufficient or worthwhile for leadership in a school to refer to cultural capital with the hope that, by the next staff meeting, the cultural capital box is being 'ticked'.

Yes, cultural capital is present as part of the Ofsted inspection framework. However, ensuring that students in schools have access to opportunities to enhance and build their cultural capital is equally, if not more, important, to ensure that the most excellent that has been imagined said to enable them to access the dish, diverse and complex society they are living in.

It would be highly beneficial for senior leaders to have a high-level plan to outline and track the journey for developing cultural capital within their school. Would you know what opportunities, experiences and references to the pinnacle of what has been thought said, for example, a Year 8 student has? Or, a Year 10 student? This higher level plan, then, would be produced in collaboration with middle leaders. It also creates some accountability for middle leaders to ensure that their curriculum are accessible to all, by addressing matters of the finest that has been conceived said, and also culturally enriching.

One point of note, though. It would, of course, be lovely to visit a theatre or a classical music concert or travel on the London Underground. However, cultural capital development does not, and should not, only be limited to visiting physical places in person.

Knowing the curriculum you teach is important, as well as the essential knowledge that students may need to be successful in your subject. What does this mean in reality? It means knowing that students are diverse as is their cultural knowledge. For some, this may be quite limited. So, go through your schemes of learning and question whether there are any ambiguous themes, ideas or words that some may struggle to access. Once these are ascertained, use the opportunity not to fleetingly refer to a broad concept that might be related, but rather, to meaningfully help students to understand what they are learning about.

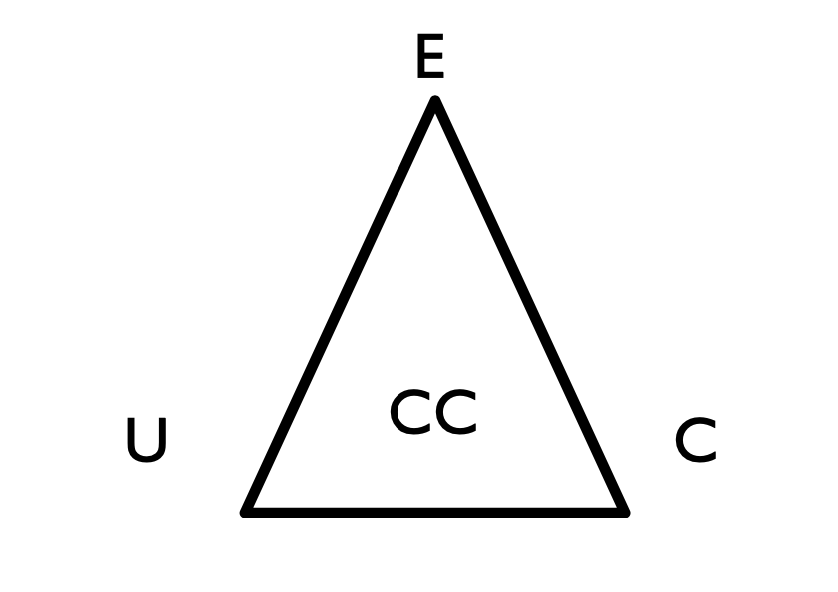

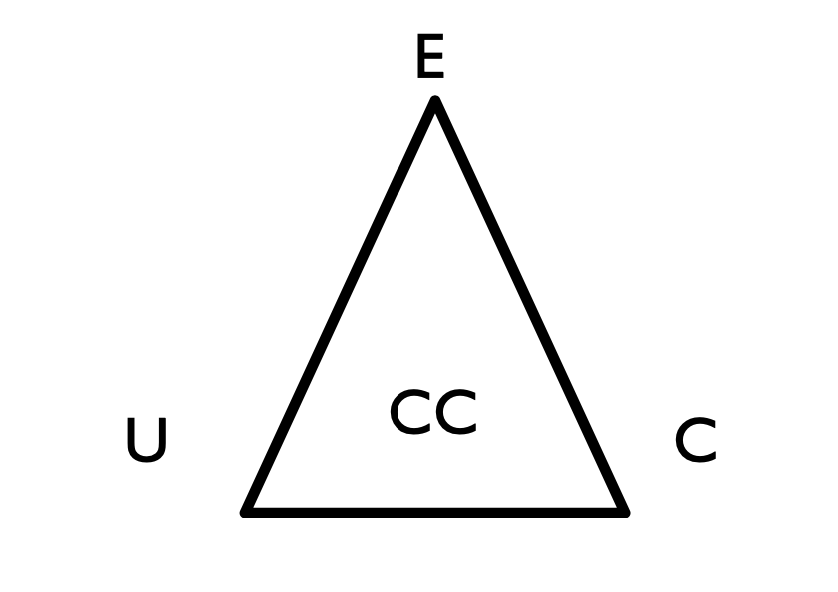

Maybe think of it like this and, if helpful, encourage your colleagues to think like this, too. Cultural capital cannot be successfully developed through merely experiencing something. Similarly, cultural capital cannot be developed through vague reference to an aspect of ‘culture’, without situating it within a wider contextual framework. Consider experience (E), understanding (U) and context (C).

The reference to ‘experience’ within this model does not, necessarily, refer to an experience of engagement with material culture.

It is designed to extend and enrich staff understanding of their task in engaging each student in cultural capital and aims to allow staff to question what it means for students to be a well-rounded citizen in a pluralist society.

Here are some examples that may help contextualise the thinking.

For example: the theatre

(Credit Royal Shakespeare Company)

If, in Drama, you are considering the composition of a theatre, with its range of seating, the concepts of the stalls, dress circle and upper circle may be challenging or unknown to some who have not experienced the theatre.

This is how using the suggested model above may support an enhanced cultural capital development.

Experience - Using an online tour of a theatre, find different seating types, question what the views of the stage are like from different seats. If students have iPads, why not get them to do this themselves?

Understanding - Get into discussions about why different seats are in a theatre, why these are at different prices, why there are boxes?

Context - Within these discussions, refer to the historical background of who would usually sit in the boxes, refer to why some boxes have plaques on and what these mean, give examples of local as well as famous theatres.

For example: the coast

(Credit to Pixabay)

If, in Geography, you are considering features of the coast, there will be a range of vocabulary that some students may not have been aware of before. Such as groynes, buoy and pier.

This is how using the suggested model above may support an enhanced cultural capital development.

Experience - Using your teacher iPad, use the Flyover feature on Apple Maps to visit different coastal locations. Then, give students some suggested locations for them to compare on their iPads.

Understanding - Then, ask Students to screen shot and highlight notable features. They could use their iPads to direct their conversations to certain coastal features and the teacher could use these conversations to address key words for these features.

Context - Teachers may then want why buoy or groynes are used at the coast. They might want to explain why many coastal locations have a pier, including why some now have piers that are not used any more.

Key resources include Bourdieu's 'The Forms of Capital' for theoretical foundations and E. D. Hirsch's 'Cultural Literacy' for practical classroom applications. The Education Endowment Foundation provides evidence-based guidance on addressing cultural capital gaps through explicit teaching strategies. Ofsted's Education Inspection Framework (2019) offers the official UK perspective on how cultural capital should be implemented in schools.

The reviewed studies underscore the importance of cultural capital in educational attainment and success. Promoting cultural capital through family interactions, extracurricular activities, and educational policies can significantly enhance studentoutcomes. Understanding the mechanisms through which cultural capital operates can help in designing effective educational interventions to reduce inequalities.

1. Cultural Capital and Educational Attainment

This paper explores how cultural capital, as theorised by Bourdieu, influences educational attainment. The study finds that cultural capital is transmitted within the home and significantly impacts performance in GCSE examinations. However, social class continues to have a direct effect on educational attainment even when cultural capital is accounted for (Sullivan, 2001).

2. Cultural Capital in East Asian Educational Systems

The authors examine how cultural capital operates within Japan's educational system, which relies heavily on standardised examinations. The study suggests that cultural capital, including extracurricular education, plays a crucial role in educational outcomes, highlighting the need for understanding these dynamics in different cultural contexts (Yamamoto & Brinton, 2010).

3. Cultural Capital and Education

This article reviews various definitions and theoretical contexts of cultural capital, particularly its relationship with schooling and educational outcomes. It provides an overview of empirical research on cultural capital from multiple nations and discusses ongoing controversies and future research directions (Dumais, 2015).

4. Equal Access but Unequal Outcomes: Cultural Capital and Educational Choice in a Meritocratic Society

The study analyses how cultural capital promotes educational success in Denmark, a meritocratic society. It identifies three critical conditions: parents must possess cultural capital, transfer it to their children, and children must absorb and convert it into educational success. The findings underscore the importance of cultural capital in educational choices and success (Jæger, 2009).

5. Cultural Capital and Its Effects on Education Outcomes

This research distinguishes between static and relational forms of cultural capital and examines their effects on students' reading literacy, sense of belonging at school, and occupational aspirations across 28 countries. The study finds that dynamic cultural capital significantly impacts educational outcomes, while static cultural capital has more modest effects (Tramonte & Willms, 2010).

Cultural capital refers to culturally acquired knowledge, skills, and understanding that help students navigate academic and social situations, such as knowing what 'the tube' means or understanding theatre terminology like 'dress circle'. It's distinct from intelligence (human capital) or wealth (economic capital) because it's about specific cultural knowledge and social codes that must be learned through experience or explicit teaching.

Teachers can spot cultural capital gaps when students seem confused by references that seem obvious, such as not understanding what 'the tube' means in geography texts or being puzzled by theatre terms in maths problems. Listen for moments when students struggle not with the academic content it sel f, but with the cultural references or social codes embedded within the learning materials.

Schools need to explicitly teach the social codes and cultural knowledge that help students decode experiences, rather than just providing cultural exposure. This means teaching students how to engage with cultural institutions, explaining cultural references when they appear in texts, and directly instructing students on academic social codes like formal email writing and classroom discussion participation.

Since 2019, Ofsted requires schools to show how their curriculum provides students with the cultural capital they need to succeed in life, making it a key inspection focus. This means schools must now develop whole-school strategies to identify and address cultural knowledge gaps that could disadvantage some students academically.

Bourdieu's approach focuses on how cultural knowledge reflects social class and power structures, whilst Hirsch emphasises teaching essential knowledge and cultural literacy that all students need regardless of background. In practice, teachers can use Hirsch's approach to identify what cultural knowledge to teach explicitly, whilst being mindful of Bourdieu's insights about which students might be disadvantaged by cultural assumptions in their teaching.

Common examples include understanding geographical references like 'the tube' for London's underground system, knowing theatre terminology such as 'dress circle', and being familiar with how to navigate cultural institutions like museums and libraries. Teachers also often assume students know social codes like how to write formal emails or participate appropriately in academic discussions.

Parents can explicitly explain cultural references when they encounter them in daily life, teach social codes for different situations, and help children understand how to engage meaningfully with cultural experiences rather than just providing exposure. The key is making implicit cultural knowledge explicit through direct teaching and explanation, not just hoping children will absorb it through exposure alone.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into cultural capital in education: understanding and building student advantage and its application in educational settings.

Race in the Schoolyard: Negotiating the Color Line in Classrooms and Communities 614 citations

Lewis et al. (2003)

Lewis examines how race intersects with educational experiences in schools and communities, exploring how racial dynamics play out in classroom settings and affect student outcomes. This work is essential for teachers to understand how racial identity and cultural differences impact students' access to and accumulation of cultural capital, particularly for students from marginalized racial backgrounds.

Unequal by Design 410 citations

Au et al. (2008)

Au analyses how standardised testing and neoliberal educational policies create and reinforce educational inequalities through systematic design flaws. This book helps teachers understand how institutional structures and policies can undermine efforts to build cultural capital among disadvantaged students, providing critical context for why some students face greater barriers to educational success.

Digital Capital and Cultural Capital in education: Unravelling intersections and distinctions that shape social differentiation 12 citations

Pitzalis et al. (2024)

Pitzalis and Porcu explore the relationship between digital skills and traditional cultural capital, examining how technology access and digital literacy create new forms of educational advantage. This research is valuable for teachers seeking to understand how digital divides intersect with cultural capital, and how to use technology to build student advantage in increasingly digital learning environments.

Income inequality, cultural capital, and high school students' academic achievement in OECD countries: A moderated mediation analysis. 23 citations

Wang et al. (2023)

Wang and Wu investigate how income inequality at the societal level affects the relationship between cultural capital and student academic achievement across OECD countries. This study provides teachers with important insights into how broader economic contexts shape the effectiveness of cultural capital, helping them understand why building cultural capital may be more challenging in high-inequality settings.

Research on cultural capital's impact on academic achievement 14 citations (Author, Year) explores how cultural resources and social advantages influence the sustainable development and educational outcomes of Chinese high school students, examining the relationship between family background, cultural knowledge, and academic success in secondary education settings.

Jin et al. (2022)

Jin, Ma, and Jiao examine how family cultural capital influences Chinese high school students' academic performance, with a focus on sustainable educational development. This research offers teachers concrete evidence of cultural capital's impact on student achievement and highlights the importance of understanding family cultural resources when working to build student advantage in diverse educational contexts.

| Examples (This IS Cultural Capital) | Non-Examples (This is NOT Cultural Capital) |

|---|---|

| Understanding that "the tube" refers to London's subway system, which helps students comprehend geography texts and travel narratives | Having expensive school supplies or the latest technology (this is economic capital, not cultural knowledge) |

| Knowing what a "dress circle" is in a theatre context, enabling students to solve math problems about ticket pricing | Being naturally intelligent or having high IQ (this is human capital, not culturally acquired knowledge) |

| Familiarity with museums, libraries, and cultural institutions that allows students to navigate these spaces confidently for research | Simply taking students on museum trips without teaching them how to engage with or decode the experience |

| Understanding social codes like how to write formal emails to teachers or participate in academic discussions | Having many friends or social connections (this is social capital, not cultural knowledge and competencies) |

The establishment of a new inspection framework from Ofstedin 2019, provided some major changes to how schools are inspected and how their quality is assured. They included an expectation that ‘cultural capital’ be inspected. Because therefore, schools now have to introduce this term to their whole school policy agenda and implement whole school strategies to address cultural capital gaps.

Recently, I overheard a conversation with a Geography teacher and a student who was questioning why boys are out at sea, 24 hours, 7 days a week. Similarly, a conversation with a Maths teacher and a student about what a dress circle is and how this is related to a theatre and their practice question on prices of seats. In addition, a colleague also explained the confusion of a student when they explained their recent journey on the tube and on the underground, which followed with questions about why their teacher was apparently in a tube, underground and using it to get from place to place.

When referring to cultural capital, there is a wide range of theories. Is it referring to social capital or is it referring to economic capital and human capital? It is more specifically related to forms of capital with reference to economic capital and social mobility or is it, instead, more to do with class differences, class inequalities, someone's social network, forms of knowledge and accumulation of knowledge? Some may say that cultural capital refers to childhood education, arts activities leisure activities affecting cultural competence. However, others may say that the body of knowledge on cultural capital theory is too broad in one definition.

In this article, we aim to establish the range of definitions of cultural capital by considering the idea of capital and cultural capital from different perspectives. We then aim to consider what Ofsted say about cultural capital before considering what this means for senior leaders, middle leaders and classroom practitioners.

Cultural capital was first introduced by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu in the 1970s to explain how social class advantages are passed through families via knowledge, skills, and cultural experiences. The concept gained prominence in UK education after Ofsted's 2019 framework made it a requirement for school inspections. This shift required schools to actively address cultural knowledge gaps that affect student achievement.

Bourdieu? Marx? Arnold? If you were a reader of English Literature or an Historian you might be familiar with the idea of ‘high and low’ culture and the idea of “the best which has been thought and said” (Arnold, 1875, p.10) which often seems to imply, whether right or wrong, that Shakespeare and Mozart and museum visits, not the integration of hip hop culture or vernacular cultures, should be generally written into the curriculum. The idea of cultural capital, however, if you are a sociologist, will be associated with Pierre Bourdieu (1977; 1984; 1986) or Marx (1967) and has more to do with power and the alienation of the working classes through certain types of ‘cultural capital’ than it has to do with maintaining what Matthew Arnold phrased “the best which that has been thought and said” (Arnold, 1875, p.10).

Neither the National Curriculum document (DfE, 2014) nor Ofsted (2019) offer elaboration on this definition in terms of criteria of Ofsted inspections, but simply state that they will be inspecting whether “leaders construct a curriculum [..] designed to give all learners [..] the knowledge and cultural capital they need to s ucceed in life” (Ofsted, 2019, p.9).

Pierre Bourdieu

The term cultural capital originates in the work of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (Bourdieu, 1977; 1984; 1986). For Bourdieu (1977; 1984; 1986), cultural capital is specifically linked to social class and acquisition of cultural capital. Bourdieu (1986) says that it “can be acquired, to a varying extent, depending on the period, the society, and the social class” (p.245). It is, therefore, dependent on the upbringing of an individual and the influence their social class has on this.

Bourdieu (1977) also refers to the development of an individual’s habitus, which has links to both the external wealth of an individual as well as to embodied forms of cultural capital which might arise from grammar schooling, faith-based schooling or independent schooling.

E. D. Hirsch Jr. Views cultural capital as the essential knowledge and vocabulary that all students need to succeed academically, regardless of their background. He argues that schools should explicitly teach this shared cultural literacythrough a knowledge-rich curriculum. This approach focuses on closing achievement gaps by ensuring all students have access to the same foundational cultural references.

Hirsch (1987), too, in his work on cultural literacy, proposed that there are certain kinds of knowledge that all individuals should have access to. In short, he says “To be culturally literate is to possess the basic information needed to thrive in the modern world” (Hirsch, 1987, p.12). This implies the requirement of a bedrock of essential knowledge to succeed in society. Reay (2017) points out that the conflation of Bourdieu’s concept (not necessarily to do with knowledge or, explicitly, the curriculum) and Hirsch’s idea of cultural literacy (which is to do with types of knowledge), is one of the most unhelpful aspects of Ofsted’s mis-definition of the term in their own policy documents (Reay, 2017).

Hirsch’s (1987) United States-based work on cultural literacy suggests that all individuals need to acquire essential, basic knowledge but he also says that “Children also need to understand elements of our literary and mythic heritage that are often alluded to without explanation” (Hirsch 1987, p.30). This means that when individuals hear, or interact with, names of multi-cultural mythic characters, characters in literature, art and music from across the world (Hirsch, 1987) they also need to be given the ‘social codes’ which enable them to read them (Hirsch, 1987). Lacking this, many will engage less well with and comprehend less about and from them. At worst further learning then becomes “increasingly toilsome, unproductive and humiliating” (Hirsch, 1987, p.28) particular if the social codes offered to them open out worlds which contradict the home habitus in which they are embedded from birth. The likelihood is that they will, then, at this point, give up trying at all. Hirsch suggest that “the most straightforward antidote to deprivation is to make the es sen tial information more readily available inside the schools.” (Hirsch, 1987, p.24).

Hirsch (1987), like Arnold, suggests that “literate culture has become the common currency for social and economic exchange in our democracy, and the only available ticket to full citizenship” (p.22) Equality of opportunity, Hirsch(1987) suggests, is available to all if they have this shared cultural literacy because “share d background knowledge [enables them] to communicate effectively with everyone else” (p.32).

Accessing the curriculum has to be the prime motivator in developing cultural capital because, if you cannot access, it how are you ever going to understand it, let alone be socially mobile within its structures?

In more recent terms

Many other academics also see a link between social privilege (Mohr and DiMaggio, 1995) and academic achievement in schools. DiMaggio (1982) was one of the recent academics to consider a possible relationship between cultural capital and educational achievement and Bennett et al. (2009) produced a comprehensive analysis of the work of Bourdieu and cultural capital. In their work, they suggest that “Those parents equipped with cultural capital are able to drill their children in the cultural forms that predispose them to perform well in the educational system” (Bennett et al., 2009, p.13).

For Ofsted, the definition of cultural capital is:

“the essential knowledge that pupils need to be educated citizens, introducing the finest that has been conceived achievement” (DfE, 2014, p.5).

The extent to which classroom teachers, middle or senior leaders are familiar with this idea, in the form it has entered education, would depend on how many had either studied or become in other ways acquainted with the mixture of ideas in this definition, in either first degree, initial teacher or other training.

So, with this working definition of cultural capital from the Department for Education, what are some of the misconceptions surrounding cultural capital and what could this mean for practitioners in the classroom, middle and senior leaders?

This exemplifies two ideas. Firstly, Matthew Arnold’s (1875) idea surrounding “the best which has been thought and said” (p.10) and, secondly, the idea that cultural literacy (Hirsch, 1977), a form of knowledge, is needed to acquire it. This is very different from both Marx and Bourdieu’s socially (semi) deterministic view of cultural capital. It suggests, for instance, that just ‘knowing about’ the idea of cultural literacy (explicit curriculum) is not as important as also ‘learning from’ it (implicit curriculum).

For example, by experiencing so called ‘high culture’ at first hand we validate different cultures (home or family influence) both implicitly and explicitly. Through assemblies, by introducing books or new Information Technology resources, such as iPads, into all schools, we are also both implicitly and explicitly insisting that those from disadvantaged backgrounds should have equal access to all sources of culture, not just the more limited ones they may experience at home.

Cultural knowledge is skewed because middle-class students often arrive at school with experiences and vocabulary that align with academic expectations, while working-class students may lack exposure to these references. Teachers unconsciously assume all students understand concepts like 'the tube' or 'dress circle,' creating hidden barriers to learning. This inequality perpetuates achievement gaps when schools fail to explicitly teach the cultural codes embedded in their curriculum.

It would be reasonable to suggest that many teachers may associate the acquisition of ‘knowing’ with acquiring cultural capital, without deeply understanding how. For Marx and Bourdieu, the ability to know is already skewed, in schools, by the curriculum’s own content and by pupils’ prior experience (habitus). Therefore, as a result, they do not currently understand that more sophisticated targeting, throughout both implicit and explicit curriculum, would be needed to truly implement Ofsted’s idea of ‘cultural capital.’

There is a three-pronged approach here involving:

1. Senior Leaders, Higher-level plan

2. Middle Leaders, Knowing your curriculum and supporting department colleagues

3. Classroom practitioners - Supporting students

It is not sufficient or worthwhile for leadership in a school to refer to cultural capital with the hope that, by the next staff meeting, the cultural capital box is being 'ticked'.

Yes, cultural capital is present as part of the Ofsted inspection framework. However, ensuring that students in schools have access to opportunities to enhance and build their cultural capital is equally, if not more, important, to ensure that the most excellent that has been imagined said to enable them to access the dish, diverse and complex society they are living in.

It would be highly beneficial for senior leaders to have a high-level plan to outline and track the journey for developing cultural capital within their school. Would you know what opportunities, experiences and references to the pinnacle of what has been thought said, for example, a Year 8 student has? Or, a Year 10 student? This higher level plan, then, would be produced in collaboration with middle leaders. It also creates some accountability for middle leaders to ensure that their curriculum are accessible to all, by addressing matters of the finest that has been conceived said, and also culturally enriching.

One point of note, though. It would, of course, be lovely to visit a theatre or a classical music concert or travel on the London Underground. However, cultural capital development does not, and should not, only be limited to visiting physical places in person.

Knowing the curriculum you teach is important, as well as the essential knowledge that students may need to be successful in your subject. What does this mean in reality? It means knowing that students are diverse as is their cultural knowledge. For some, this may be quite limited. So, go through your schemes of learning and question whether there are any ambiguous themes, ideas or words that some may struggle to access. Once these are ascertained, use the opportunity not to fleetingly refer to a broad concept that might be related, but rather, to meaningfully help students to understand what they are learning about.

Maybe think of it like this and, if helpful, encourage your colleagues to think like this, too. Cultural capital cannot be successfully developed through merely experiencing something. Similarly, cultural capital cannot be developed through vague reference to an aspect of ‘culture’, without situating it within a wider contextual framework. Consider experience (E), understanding (U) and context (C).

The reference to ‘experience’ within this model does not, necessarily, refer to an experience of engagement with material culture.

It is designed to extend and enrich staff understanding of their task in engaging each student in cultural capital and aims to allow staff to question what it means for students to be a well-rounded citizen in a pluralist society.

Here are some examples that may help contextualise the thinking.

For example: the theatre

(Credit Royal Shakespeare Company)

If, in Drama, you are considering the composition of a theatre, with its range of seating, the concepts of the stalls, dress circle and upper circle may be challenging or unknown to some who have not experienced the theatre.

This is how using the suggested model above may support an enhanced cultural capital development.

Experience - Using an online tour of a theatre, find different seating types, question what the views of the stage are like from different seats. If students have iPads, why not get them to do this themselves?

Understanding - Get into discussions about why different seats are in a theatre, why these are at different prices, why there are boxes?

Context - Within these discussions, refer to the historical background of who would usually sit in the boxes, refer to why some boxes have plaques on and what these mean, give examples of local as well as famous theatres.

For example: the coast

(Credit to Pixabay)

If, in Geography, you are considering features of the coast, there will be a range of vocabulary that some students may not have been aware of before. Such as groynes, buoy and pier.

This is how using the suggested model above may support an enhanced cultural capital development.

Experience - Using your teacher iPad, use the Flyover feature on Apple Maps to visit different coastal locations. Then, give students some suggested locations for them to compare on their iPads.

Understanding - Then, ask Students to screen shot and highlight notable features. They could use their iPads to direct their conversations to certain coastal features and the teacher could use these conversations to address key words for these features.

Context - Teachers may then want why buoy or groynes are used at the coast. They might want to explain why many coastal locations have a pier, including why some now have piers that are not used any more.

Key resources include Bourdieu's 'The Forms of Capital' for theoretical foundations and E. D. Hirsch's 'Cultural Literacy' for practical classroom applications. The Education Endowment Foundation provides evidence-based guidance on addressing cultural capital gaps through explicit teaching strategies. Ofsted's Education Inspection Framework (2019) offers the official UK perspective on how cultural capital should be implemented in schools.

The reviewed studies underscore the importance of cultural capital in educational attainment and success. Promoting cultural capital through family interactions, extracurricular activities, and educational policies can significantly enhance studentoutcomes. Understanding the mechanisms through which cultural capital operates can help in designing effective educational interventions to reduce inequalities.

1. Cultural Capital and Educational Attainment

This paper explores how cultural capital, as theorised by Bourdieu, influences educational attainment. The study finds that cultural capital is transmitted within the home and significantly impacts performance in GCSE examinations. However, social class continues to have a direct effect on educational attainment even when cultural capital is accounted for (Sullivan, 2001).

2. Cultural Capital in East Asian Educational Systems

The authors examine how cultural capital operates within Japan's educational system, which relies heavily on standardised examinations. The study suggests that cultural capital, including extracurricular education, plays a crucial role in educational outcomes, highlighting the need for understanding these dynamics in different cultural contexts (Yamamoto & Brinton, 2010).

3. Cultural Capital and Education

This article reviews various definitions and theoretical contexts of cultural capital, particularly its relationship with schooling and educational outcomes. It provides an overview of empirical research on cultural capital from multiple nations and discusses ongoing controversies and future research directions (Dumais, 2015).

4. Equal Access but Unequal Outcomes: Cultural Capital and Educational Choice in a Meritocratic Society

The study analyses how cultural capital promotes educational success in Denmark, a meritocratic society. It identifies three critical conditions: parents must possess cultural capital, transfer it to their children, and children must absorb and convert it into educational success. The findings underscore the importance of cultural capital in educational choices and success (Jæger, 2009).

5. Cultural Capital and Its Effects on Education Outcomes

This research distinguishes between static and relational forms of cultural capital and examines their effects on students' reading literacy, sense of belonging at school, and occupational aspirations across 28 countries. The study finds that dynamic cultural capital significantly impacts educational outcomes, while static cultural capital has more modest effects (Tramonte & Willms, 2010).

Cultural capital refers to culturally acquired knowledge, skills, and understanding that help students navigate academic and social situations, such as knowing what 'the tube' means or understanding theatre terminology like 'dress circle'. It's distinct from intelligence (human capital) or wealth (economic capital) because it's about specific cultural knowledge and social codes that must be learned through experience or explicit teaching.

Teachers can spot cultural capital gaps when students seem confused by references that seem obvious, such as not understanding what 'the tube' means in geography texts or being puzzled by theatre terms in maths problems. Listen for moments when students struggle not with the academic content it sel f, but with the cultural references or social codes embedded within the learning materials.

Schools need to explicitly teach the social codes and cultural knowledge that help students decode experiences, rather than just providing cultural exposure. This means teaching students how to engage with cultural institutions, explaining cultural references when they appear in texts, and directly instructing students on academic social codes like formal email writing and classroom discussion participation.

Since 2019, Ofsted requires schools to show how their curriculum provides students with the cultural capital they need to succeed in life, making it a key inspection focus. This means schools must now develop whole-school strategies to identify and address cultural knowledge gaps that could disadvantage some students academically.

Bourdieu's approach focuses on how cultural knowledge reflects social class and power structures, whilst Hirsch emphasises teaching essential knowledge and cultural literacy that all students need regardless of background. In practice, teachers can use Hirsch's approach to identify what cultural knowledge to teach explicitly, whilst being mindful of Bourdieu's insights about which students might be disadvantaged by cultural assumptions in their teaching.

Common examples include understanding geographical references like 'the tube' for London's underground system, knowing theatre terminology such as 'dress circle', and being familiar with how to navigate cultural institutions like museums and libraries. Teachers also often assume students know social codes like how to write formal emails or participate appropriately in academic discussions.

Parents can explicitly explain cultural references when they encounter them in daily life, teach social codes for different situations, and help children understand how to engage meaningfully with cultural experiences rather than just providing exposure. The key is making implicit cultural knowledge explicit through direct teaching and explanation, not just hoping children will absorb it through exposure alone.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into cultural capital in education: understanding and building student advantage and its application in educational settings.

Race in the Schoolyard: Negotiating the Color Line in Classrooms and Communities 614 citations

Lewis et al. (2003)

Lewis examines how race intersects with educational experiences in schools and communities, exploring how racial dynamics play out in classroom settings and affect student outcomes. This work is essential for teachers to understand how racial identity and cultural differences impact students' access to and accumulation of cultural capital, particularly for students from marginalized racial backgrounds.

Unequal by Design 410 citations

Au et al. (2008)

Au analyses how standardised testing and neoliberal educational policies create and reinforce educational inequalities through systematic design flaws. This book helps teachers understand how institutional structures and policies can undermine efforts to build cultural capital among disadvantaged students, providing critical context for why some students face greater barriers to educational success.

Digital Capital and Cultural Capital in education: Unravelling intersections and distinctions that shape social differentiation 12 citations

Pitzalis et al. (2024)

Pitzalis and Porcu explore the relationship between digital skills and traditional cultural capital, examining how technology access and digital literacy create new forms of educational advantage. This research is valuable for teachers seeking to understand how digital divides intersect with cultural capital, and how to use technology to build student advantage in increasingly digital learning environments.

Income inequality, cultural capital, and high school students' academic achievement in OECD countries: A moderated mediation analysis. 23 citations

Wang et al. (2023)

Wang and Wu investigate how income inequality at the societal level affects the relationship between cultural capital and student academic achievement across OECD countries. This study provides teachers with important insights into how broader economic contexts shape the effectiveness of cultural capital, helping them understand why building cultural capital may be more challenging in high-inequality settings.

Research on cultural capital's impact on academic achievement 14 citations (Author, Year) explores how cultural resources and social advantages influence the sustainable development and educational outcomes of Chinese high school students, examining the relationship between family background, cultural knowledge, and academic success in secondary education settings.

Jin et al. (2022)

Jin, Ma, and Jiao examine how family cultural capital influences Chinese high school students' academic performance, with a focus on sustainable educational development. This research offers teachers concrete evidence of cultural capital's impact on student achievement and highlights the importance of understanding family cultural resources when working to build student advantage in diverse educational contexts.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cultural-capital#article","headline":"Cultural Capital in Education: Understanding and Building Student Advantage","description":"Explore Bourdieu's concept of cultural capital and its impact on educational achievement. Learn how schools can recognise and build cultural capital to...","datePublished":"2023-01-26T09:33:21.728Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cultural-capital"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/695260353838f69ad0d010ec_695260337923951d43cdb483_cultural-capital-infographic.webp","wordCount":3735},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cultural-capital#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Cultural Capital in Education: Understanding and Building Student Advantage","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cultural-capital"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cultural-capital#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What exactly is cultural capital and how is it different from just being intelligent or having money?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Cultural capital refers to culturally acquired knowledge, skills, and understanding that help students navigate academic and social situations, such as knowing what 'the tube' means or understanding theatre terminology like 'dress circle'. It's distinct from intelligence (human capital) or wealth (e"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers identify when students are missing cultural capital in their lessons?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can spot cultural capital gaps when students seem confused by references that seem obvious, such as not understanding what 'the tube' means in geography texts or being puzzled by theatre terms in maths problems. Listen for moments when students struggle not with the academic content itself,"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What should schools actually do to build cultural capital beyond taking students on museum trips?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Schools need to explicitly teach the social codes and cultural knowledge that help students decode experiences, rather than just providing cultural exposure. This means teaching students how to engage with cultural institutions, explaining cultural references when they appear in texts, and directly "}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why has Ofsted made cultural capital a requirement, and what does this mean for school inspections?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Since 2019, Ofsted requires schools to show how their curriculum provides students with the cultural capital they need to succeed in life, making it a key inspection focus. This means schools must now develop whole-school strategies to identify and address cultural knowledge gaps that could disadvan"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers distinguish between Bourdieu's and Hirsch's approaches to cultural capital when planning lessons?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Bourdieu's approach focuses on how cultural knowledge reflects social class and power structures, whilst Hirsch emphasises teaching essential knowledge and cultural literacy that all students need regardless of background. In practice, teachers can use Hirsch's approach to identify what cultural kno"}}]}]}