Symbolic Interactionism in Education: How Meaning is Created in Schools

Explore how symbolic interactionism influences education by examining how students and teachers create meaning through social interactions that shape.

Symbolic interactionism is a sociological perspective that examines how people create and negotiate meaning through social interaction. In educational settings, this theory helps explain how students develop their identities, how teacher expectations shape behaviour, and why the same classroom experience can mean different things to different pupils. Understanding symbolic interactionism gives teachers insight into the micro-level processes that profoundly affect learning theories and achievement.

These symbols are crucial in the exchange of meaning and the formation of social identities. From a symbolic interactionism standpoint, social behaviour is not just reacting to the environment but involves active interpretation and meaning-making that affects engagement in the classroom.

One of the key tenets of this theory is that social life is composed of these interactions, which are not static but dynamic and constantly evolving. Social interactionism emphasises that our personal identity and the identity salience, how much a particular identity is relevant in a given situation, are shaped and reshaped through these interactions. This perspective offers a lens to understand various types of behaviours and how individuals navigate their everyday life, constantly negotiating and interpreting social meanings through both constructivisapproaches and direct experiences.

Symbolic interactionists often employ qualitative methods to explore these concepts, focusing on individual experiences and subjective interpretations. This approach allows for a deeper understanding of the complexities of social life and the nuanced ways in which people communicate and construct their realities, particularly when considering sen pupils who may interpret symbols differently.

In the forthcoming sections of this article, we will explore deeper into both the theory and practise of this area, exploring how symbolic interactionist framework informs our understanding of social behaviours and the construction of social identities in the context of education and child development.

The origin of Symbolic Interaction Theory can be traced back to the work of three key contributors: George Herbert Mead, Charles Horton Cooley, and Herbert Blumer. These scholars played a crucial role in developing this theory and shaping the field of sociology.

George Herbert Mead was a philosopher and sociologist who laid the foundation for Symbolic Interaction Theory. He argued that individuals create their sense of self through interactions with others and society. Mead believed that language and symbols are essential tools in shaping human behaviour and that individuals interpret symbols differently based on their social interactions, which influences how they respond to teacherquestioning and classroom discussions.

Following Mead, Charles Horton Cooley expanded on the concept of the "looking-glass self," which posits that individuals develop their self-identity based on how they believe others perceive them. Cooley emphasised the role of socialization and communicationin constructing one's self-concept and argued that individuals use social interactions as mirrors to understand how others view them.

Herbert Blumer, a student of Mead, further developed Symbolic Interaction Theory by formalizing its principles. He coined the term "symbolic interactionism" and emphasised that meaning is created through social interactions and the interpretation of symbols. According to Blumer, humans act towards things based on the meanings they assign to them, and these meanings are derived from social interactions, which differs significantly from behaviouris approaches that focus on stimulus-response patterns.

George Herbert Mead laid the groundwork for Symbolic Interaction Theory in the early 20th century. Charles Horton Cooley expanded on Mead's ideas in the 1920s with his concept of the looking-glass self. Finally, Herbert Blumer solidified and formalized Symbolic Interaction Theory in the mid-20th century.

The development of symbolic interaction theory is a rich tapestry of intellectual progress, marked by significant contributions and milestones. Below is a vertical timeline highlighting key dates and events that have shaped this sociological perspective:

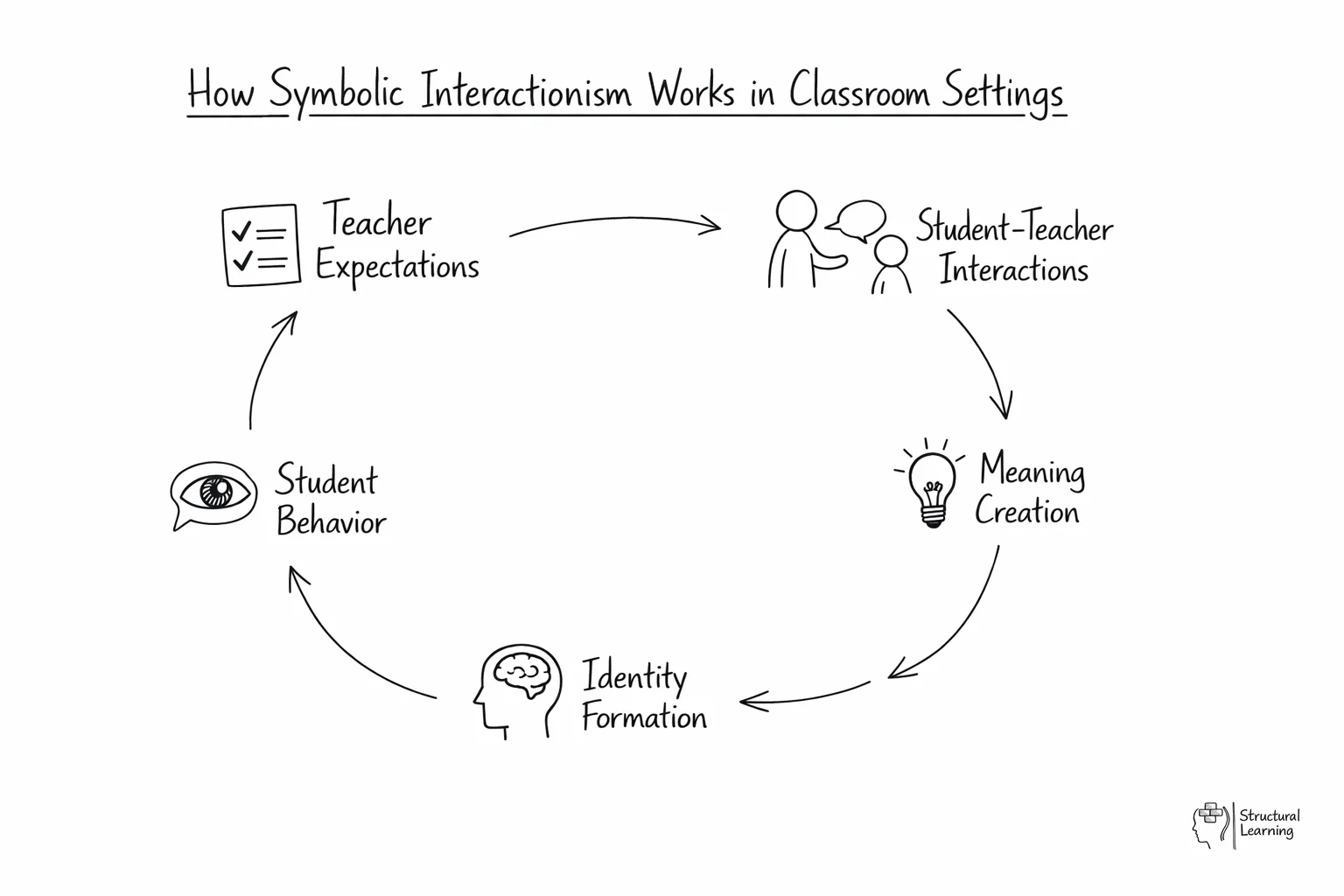

In educational settings, symbolic interactionism takes on particular significance because schools are fundamentally social institutions where meaning is constantly negotiated. Every classroom interaction, from a teacher's raised eyebrow to a student's enthusiastic hand gesture, carries symbolic weight that shapes the learning environment. Consider how a simple phrase like "good effort" can be interpreted differently depending on tone, context, and the relationship between teacher and student. One pupil might hear genuine encouragement, whilst another perceives patronising disappointment, demonstrating how symbolic meaning emerges through individual interpretation rather than objective reality.

The theory also highlights how educational institutions create and maintain their own symbolic systems. School uniforms, achievement certificates, seating arrangements, and even the physical layout of classrooms all function as symbols that communicate values, expectations, and social hierarchies. These symbols don't have inherent meaning but acquire significance through collective agreement and repeated interaction within the school community. For educators, understanding these symbolic dimensions enables more intentional classroom management and helps create inclusive environments where all students can construct positive educational identities through meaningful social interactions.

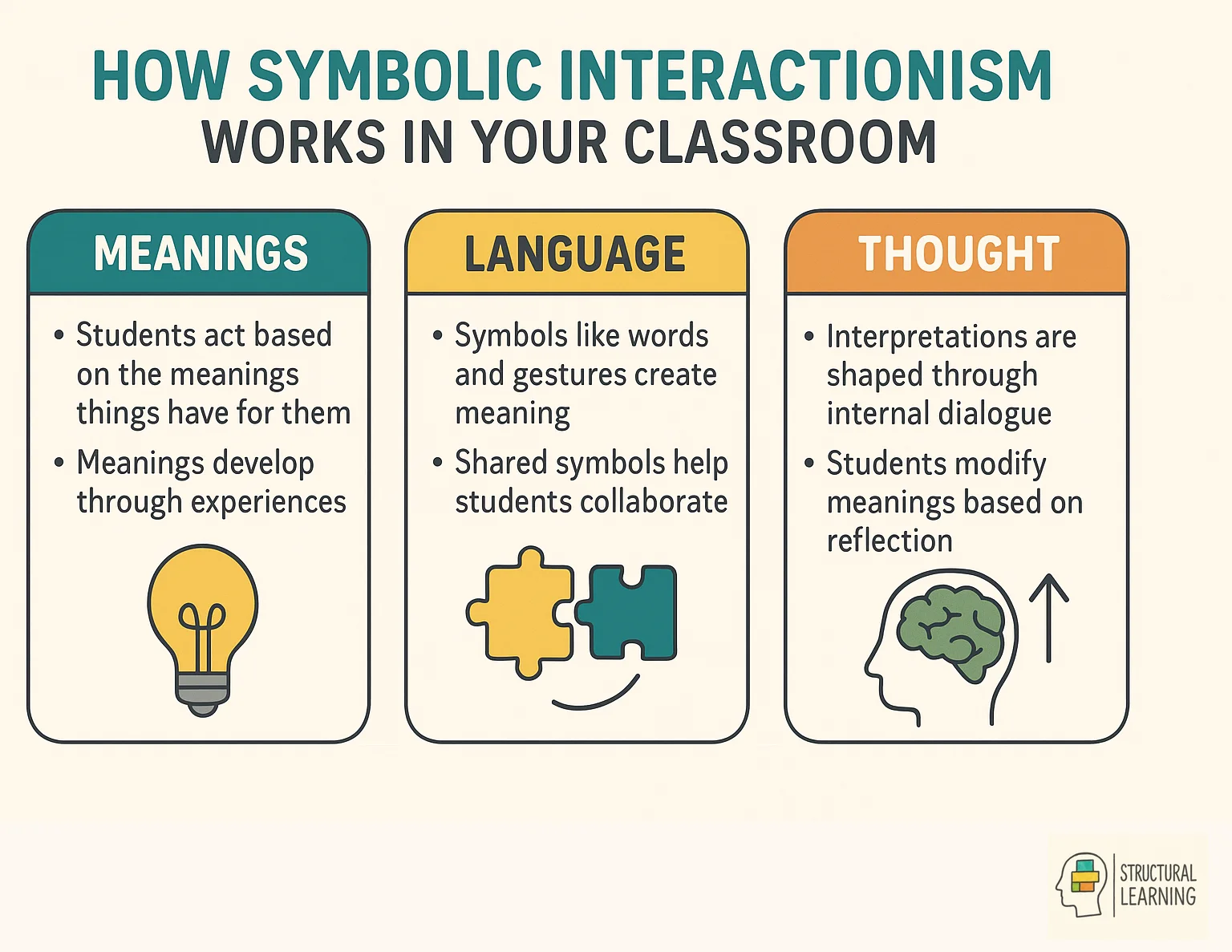

Three fundamental principles of symbolic interactionism shape every educational encounter within schools. First, meaning emerges through social interaction rather than existing independently. In classroom contexts, this means that concepts like 'success', 'intelligence', or 'appropriate behaviour' are not fixed definitions but evolve through ongoing dialogue between teachers and students. Second, individuals interpret and respond to symbols based on their personal and cultural experiences. A raised hand, a particular seating arrangement, or even silence carries different meanings for different participants in the educational process.

The third principle, that meanings are continuously modified through social encounters, proves particularly significant in educational settings. As Mead's foundational work suggests, our understanding of roles and expectations shifts through each interaction. A student's perception of their academic ability, for example, develops through countless micro-interactions: teacher feedback, peer responses, and self-reflection combine to create an evolving sense of academic identity.

Practically, these principles remind educators that learning environments are constructed spaces where meaning is negotiated daily. Teachers who recognise this dynamic can deliberately shape positive interactions, ensuring that classroom symbols and routines promote inclusive learning rather than inadvertently marginalising certain students through unexamined assumptions about behaviour or achievement.

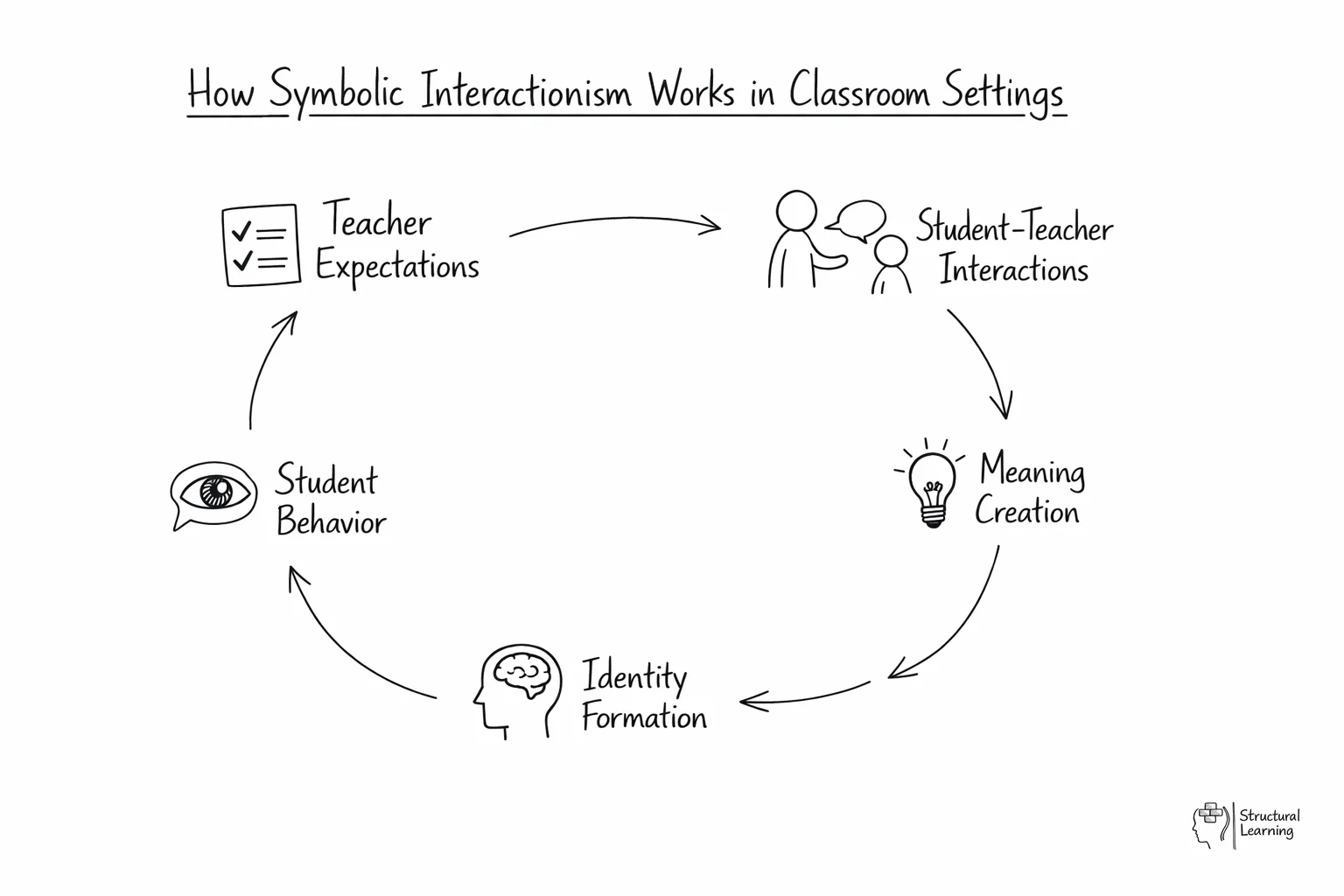

The daily exchanges between teachers and students represent the most fundamental site of meaning-making in educational settings. Every interaction, from a raised eyebrow during a lesson to encouraging feedback on an assignment, contributes to the ongoing construction of what it means to be a learner, teacher, or successful student. These micro-interactions accumulate over time, creating powerful narratives that shape both academic identity and educational outcomes. Mead's concept of the "generalised other" becomes particularly relevant here, as students learn to see themselves through the perceived expectations and reactions of their teachers.

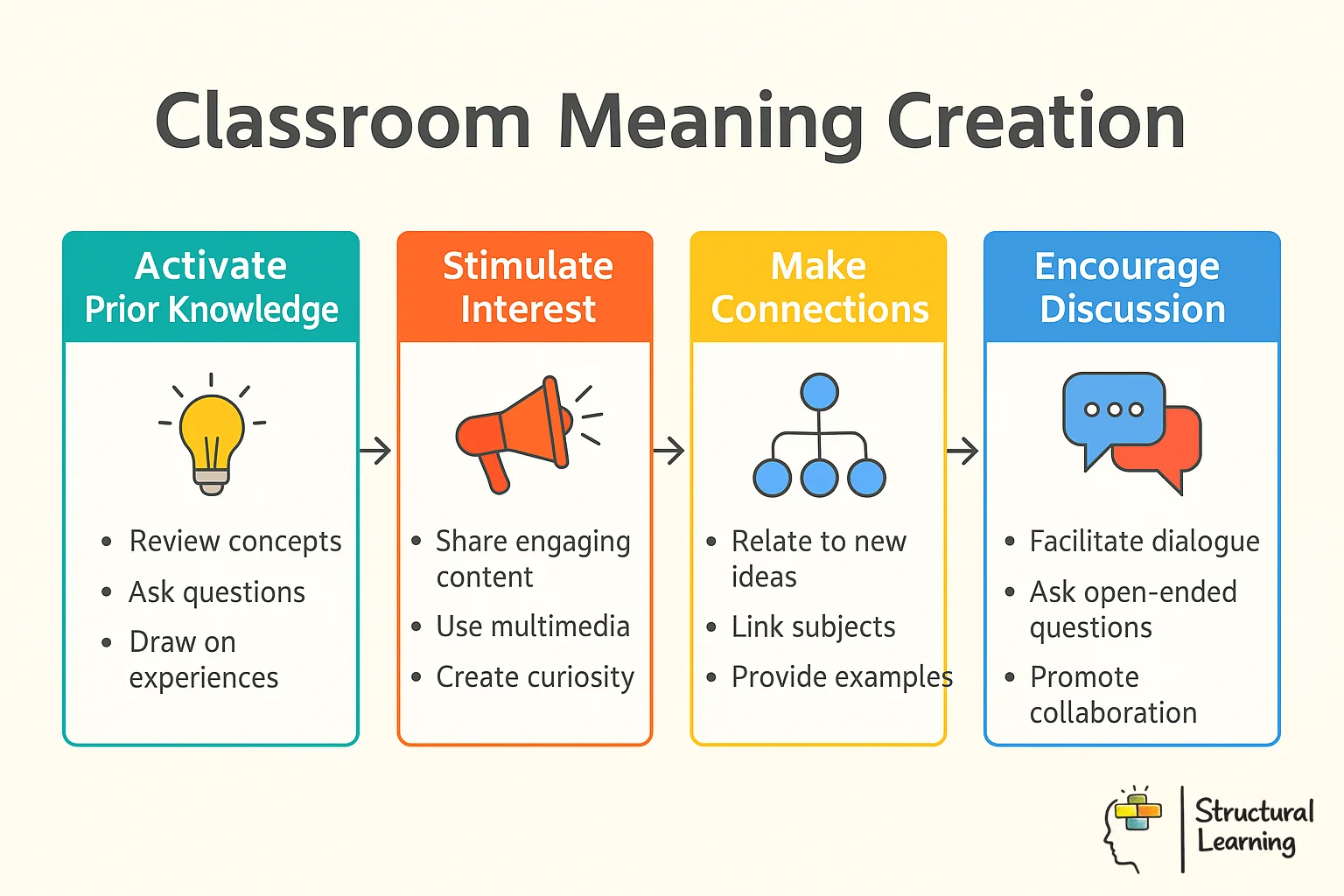

Teachers' verbal and non-verbal communication patterns significantly influence how students interpret their own capabilities and potential. When educators consistently use growth-oriented language ("Let's explore this together" rather than "You've got this wrong"), they co-create meanings around learning as a collaborative process rather than a performance evaluation. Similarly, student responses and engagement levels signal back to teachers, influencing how they adjust their approach and expectations. This reciprocal meaning-making process demonstrates Blumer's principle that people act based on the meanings objects hold for them.

Practically, this understanding encourages teachers to become more conscious of their interpretive frameworks and communication habits. Regular reflection on classroom interactions, coupled with student feedback on their learning experiences, can reveal how meanings are being constructed and potentially reconstructed to support more positive educational outcomes.

Educational labels function as powerful symbolic tools that fundamentally shape how students perceive themselves and how others interact with them within the school environment. When teachers categorise students as 'gifted', 'struggling', or 'transformative', these labels become more than mere descriptors, they transform into social realities that influence every subsequent interaction. Ray Rist's seminal research in American classrooms revealed how teachers' early expectations, often based on socio-economic indicators rather than ability, created distinct educational pathways that persisted throughout students' academic careers.

The self-fulfiling prophecy mechanism operates through subtle but consistent changes in teacher behaviour and student response. Teachers unconsciously adjust their communication patterns, providing more challenging questions and extended wait time to students labelled as 'able', whilst offering simplified tasks and immediate assistance to those deemed 'less capable'. Students, highly attuned to these symbolic messages, gradually internalise these expectations and modify their academic self-concept accordingly. This process exemplifies symbolic interactionism's core principle: meaning emerges through social interaction and becomes the foundation for future behaviour.

Practitioners can interrupt these cycles by adopting growth-oriented language that emphasises progress rather than fixed attributes. Instead of labelling students as 'low ability', frame feedback around specific skills development: 'developing mathematical reasoning' or 'building confidence in written expression'. Regular reflection on communication patterns and conscious efforts to distribute high-expectation interactions equitably across all students can help create more helping classroom narratives.

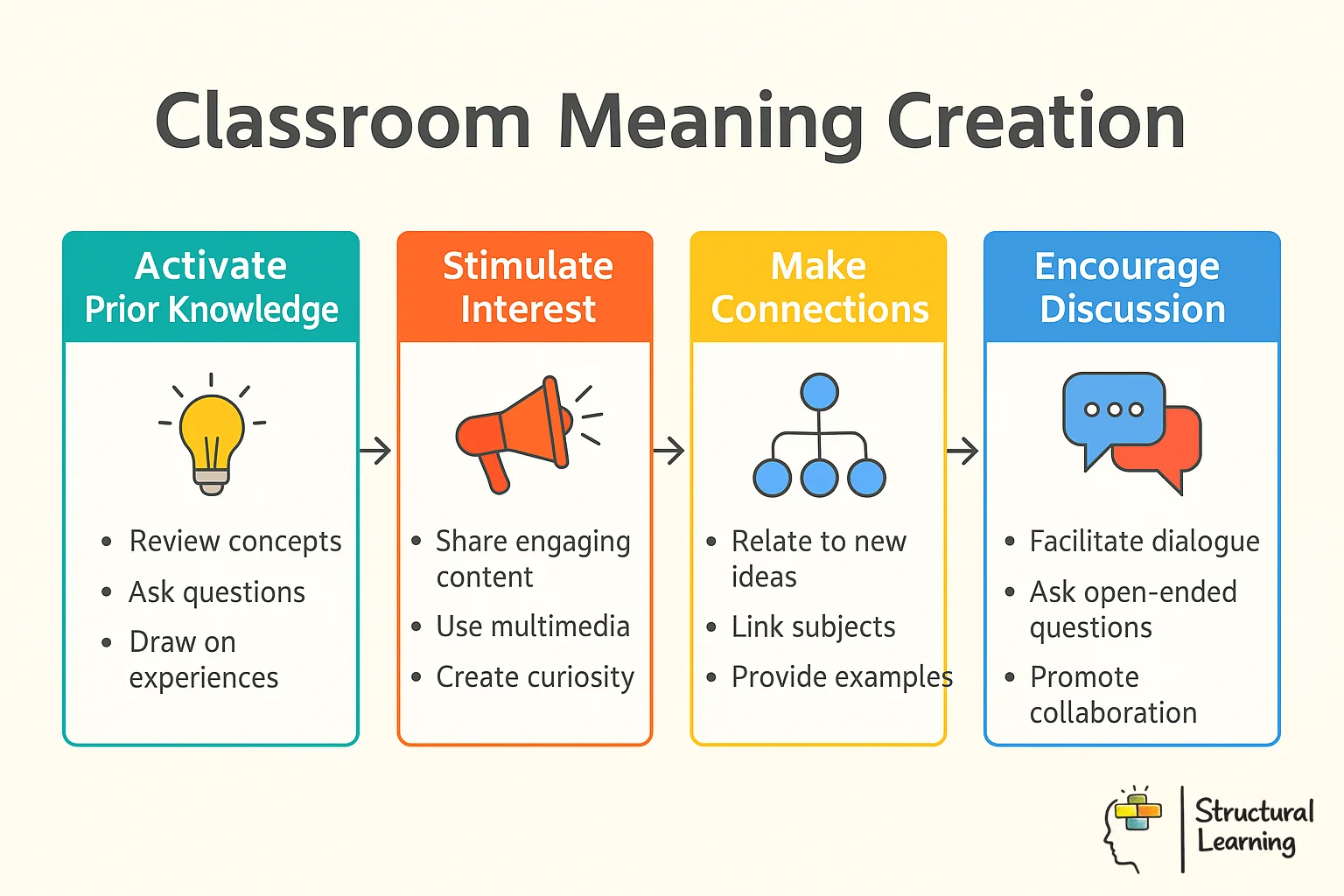

Classroom culture emerges through the deliberate and unconscious creation of symbols, rituals, and shared meanings that define how learning happens in that specific space. Teachers construct these symbolic frameworks through seemingly mundane choices: the arrangement of desks signals whether collaboration or individual focus is valued, whilst morning routines communicate expectations about punctuality, respect, and readiness to learn. Mead's concept of symbolic interactionism reveals how these physical and procedural symbols become powerful meaning-making tools that students interpret and internalise, ultimately shaping their educational identity and engagement.

The most effective classroom cultures develop through consistent symbolic communication that aligns with learning objectives. Consider how a teacher's use of specific praise language creates shared understanding about what constitutes quality work, or how establishing weekly reflection rituals signals that metacognition is valued alongside content mastery. These symbolic practices become the invisible curriculum that students navigate daily, influencing everything from risk-taking in learning to peer relationships and academic self-concept.

Practitioners can harness this symbolic power by intentionally designing classroom rituals that reinforce desired learning behaviours. Simple practices like beginning each lesson with a thinking routine, using consistent visual cues for different types of activities, or creating celebration rituals for growth rather than just achievement help establish a culture where learning processes are as valued as outcomes.

Implementing symbolic interactionist principles begins with conscious attention to language choices and their meaning-making potential. Teachers should regularly audit their verbal and non-verbal communications, recognising that seemingly innocuous phrases like "struggling student" or "bright child" construct powerful identities that students internalise. Mead's concept of the "looking-glass self" reminds us that students develop self-concepts through perceived teacher expectations, making deliberate language use a cornerstone of effective practice.

Creating opportunities for collaborative meaning-making transforms traditional power dynamics within educational contexts. Rather than positioning themselves as sole knowledge authorities, teachers can facilitate student-led discussions where learners negotiate understanding together. This approach aligns with Vygotsky's social constructivist principles whilst honouring symbolic interactionism's emphasis on shared symbol creation. Simple strategies include think-pair-share activities, peer feedback sessions, and collaborative problem-solving tasks that allow students to construct knowledge through social interaction.

Most importantly, teachers must become reflective observers of classroom interactions, noting how different symbols, rituals, and communication patterns influence student behaviour and engagement. Keeping brief interaction logs or conducting periodic self-reflection on classroom dynamics helps educators identify unintentional symbolic messages. This metacognitive approach enables teachers to consciously shape the symbolic environment, ensuring that classroom interactions promote positive identity formation and meaningful learning experiences for all students.

The symbolic interactions that occur daily in educational settings profoundly shape how students perceive themselves as learners, directly influencing their academic motivation and achievement outcomes. When teachers consistently use language that positions students as capable problem-solvers rather than passive recipients of knowledge, students internalise these positive academic identities and demonstrate increased engagement with challenging tasks. Conversely, subtle linguistic choices that emphasise deficits or limitations can create self-fulfiling prophecies, as highlighted in Rosenthal and Jacobson's seminal research on teacher expectations.

The process of meaning-making through classroom interactions extends beyond verbal communication to encompass the symbolic significance of assessment feedback, seating arrangements, and participation opportunities. Students actively interpret these symbols to construct understanding of their place within the academic hierarchy. For instance, being consistently chosen for extension activities communicates high expectations and academic capability, whilst repeated assignment to remedial tasks may inadvertently signal low teacher confidence in student potential.

Practitioners can harness symbolic interactionism by deliberately crafting classroom language and structures that reinforce growth-oriented identities. This involves using process-focused praise rather than ability-based comments, creating diverse pathways for student contribution, and ensuring that all interactions communicate belief in student potential for intellectual development within the educational context.

Symbolic interactionism is a sociological perspective that examines how people create and negotiate meaning through social interaction. In educational settings, this theory helps explain how students develop their identities, how teacher expectations shape behaviour, and why the same classroom experience can mean different things to different pupils. Understanding symbolic interactionism gives teachers insight into the micro-level processes that profoundly affect learning theories and achievement.

These symbols are crucial in the exchange of meaning and the formation of social identities. From a symbolic interactionism standpoint, social behaviour is not just reacting to the environment but involves active interpretation and meaning-making that affects engagement in the classroom.

One of the key tenets of this theory is that social life is composed of these interactions, which are not static but dynamic and constantly evolving. Social interactionism emphasises that our personal identity and the identity salience, how much a particular identity is relevant in a given situation, are shaped and reshaped through these interactions. This perspective offers a lens to understand various types of behaviours and how individuals navigate their everyday life, constantly negotiating and interpreting social meanings through both constructivisapproaches and direct experiences.

Symbolic interactionists often employ qualitative methods to explore these concepts, focusing on individual experiences and subjective interpretations. This approach allows for a deeper understanding of the complexities of social life and the nuanced ways in which people communicate and construct their realities, particularly when considering sen pupils who may interpret symbols differently.

In the forthcoming sections of this article, we will explore deeper into both the theory and practise of this area, exploring how symbolic interactionist framework informs our understanding of social behaviours and the construction of social identities in the context of education and child development.

The origin of Symbolic Interaction Theory can be traced back to the work of three key contributors: George Herbert Mead, Charles Horton Cooley, and Herbert Blumer. These scholars played a crucial role in developing this theory and shaping the field of sociology.

George Herbert Mead was a philosopher and sociologist who laid the foundation for Symbolic Interaction Theory. He argued that individuals create their sense of self through interactions with others and society. Mead believed that language and symbols are essential tools in shaping human behaviour and that individuals interpret symbols differently based on their social interactions, which influences how they respond to teacherquestioning and classroom discussions.

Following Mead, Charles Horton Cooley expanded on the concept of the "looking-glass self," which posits that individuals develop their self-identity based on how they believe others perceive them. Cooley emphasised the role of socialization and communicationin constructing one's self-concept and argued that individuals use social interactions as mirrors to understand how others view them.

Herbert Blumer, a student of Mead, further developed Symbolic Interaction Theory by formalizing its principles. He coined the term "symbolic interactionism" and emphasised that meaning is created through social interactions and the interpretation of symbols. According to Blumer, humans act towards things based on the meanings they assign to them, and these meanings are derived from social interactions, which differs significantly from behaviouris approaches that focus on stimulus-response patterns.

George Herbert Mead laid the groundwork for Symbolic Interaction Theory in the early 20th century. Charles Horton Cooley expanded on Mead's ideas in the 1920s with his concept of the looking-glass self. Finally, Herbert Blumer solidified and formalized Symbolic Interaction Theory in the mid-20th century.

The development of symbolic interaction theory is a rich tapestry of intellectual progress, marked by significant contributions and milestones. Below is a vertical timeline highlighting key dates and events that have shaped this sociological perspective:

In educational settings, symbolic interactionism takes on particular significance because schools are fundamentally social institutions where meaning is constantly negotiated. Every classroom interaction, from a teacher's raised eyebrow to a student's enthusiastic hand gesture, carries symbolic weight that shapes the learning environment. Consider how a simple phrase like "good effort" can be interpreted differently depending on tone, context, and the relationship between teacher and student. One pupil might hear genuine encouragement, whilst another perceives patronising disappointment, demonstrating how symbolic meaning emerges through individual interpretation rather than objective reality.

The theory also highlights how educational institutions create and maintain their own symbolic systems. School uniforms, achievement certificates, seating arrangements, and even the physical layout of classrooms all function as symbols that communicate values, expectations, and social hierarchies. These symbols don't have inherent meaning but acquire significance through collective agreement and repeated interaction within the school community. For educators, understanding these symbolic dimensions enables more intentional classroom management and helps create inclusive environments where all students can construct positive educational identities through meaningful social interactions.

Three fundamental principles of symbolic interactionism shape every educational encounter within schools. First, meaning emerges through social interaction rather than existing independently. In classroom contexts, this means that concepts like 'success', 'intelligence', or 'appropriate behaviour' are not fixed definitions but evolve through ongoing dialogue between teachers and students. Second, individuals interpret and respond to symbols based on their personal and cultural experiences. A raised hand, a particular seating arrangement, or even silence carries different meanings for different participants in the educational process.

The third principle, that meanings are continuously modified through social encounters, proves particularly significant in educational settings. As Mead's foundational work suggests, our understanding of roles and expectations shifts through each interaction. A student's perception of their academic ability, for example, develops through countless micro-interactions: teacher feedback, peer responses, and self-reflection combine to create an evolving sense of academic identity.

Practically, these principles remind educators that learning environments are constructed spaces where meaning is negotiated daily. Teachers who recognise this dynamic can deliberately shape positive interactions, ensuring that classroom symbols and routines promote inclusive learning rather than inadvertently marginalising certain students through unexamined assumptions about behaviour or achievement.

The daily exchanges between teachers and students represent the most fundamental site of meaning-making in educational settings. Every interaction, from a raised eyebrow during a lesson to encouraging feedback on an assignment, contributes to the ongoing construction of what it means to be a learner, teacher, or successful student. These micro-interactions accumulate over time, creating powerful narratives that shape both academic identity and educational outcomes. Mead's concept of the "generalised other" becomes particularly relevant here, as students learn to see themselves through the perceived expectations and reactions of their teachers.

Teachers' verbal and non-verbal communication patterns significantly influence how students interpret their own capabilities and potential. When educators consistently use growth-oriented language ("Let's explore this together" rather than "You've got this wrong"), they co-create meanings around learning as a collaborative process rather than a performance evaluation. Similarly, student responses and engagement levels signal back to teachers, influencing how they adjust their approach and expectations. This reciprocal meaning-making process demonstrates Blumer's principle that people act based on the meanings objects hold for them.

Practically, this understanding encourages teachers to become more conscious of their interpretive frameworks and communication habits. Regular reflection on classroom interactions, coupled with student feedback on their learning experiences, can reveal how meanings are being constructed and potentially reconstructed to support more positive educational outcomes.

Educational labels function as powerful symbolic tools that fundamentally shape how students perceive themselves and how others interact with them within the school environment. When teachers categorise students as 'gifted', 'struggling', or 'transformative', these labels become more than mere descriptors, they transform into social realities that influence every subsequent interaction. Ray Rist's seminal research in American classrooms revealed how teachers' early expectations, often based on socio-economic indicators rather than ability, created distinct educational pathways that persisted throughout students' academic careers.

The self-fulfiling prophecy mechanism operates through subtle but consistent changes in teacher behaviour and student response. Teachers unconsciously adjust their communication patterns, providing more challenging questions and extended wait time to students labelled as 'able', whilst offering simplified tasks and immediate assistance to those deemed 'less capable'. Students, highly attuned to these symbolic messages, gradually internalise these expectations and modify their academic self-concept accordingly. This process exemplifies symbolic interactionism's core principle: meaning emerges through social interaction and becomes the foundation for future behaviour.

Practitioners can interrupt these cycles by adopting growth-oriented language that emphasises progress rather than fixed attributes. Instead of labelling students as 'low ability', frame feedback around specific skills development: 'developing mathematical reasoning' or 'building confidence in written expression'. Regular reflection on communication patterns and conscious efforts to distribute high-expectation interactions equitably across all students can help create more helping classroom narratives.

Classroom culture emerges through the deliberate and unconscious creation of symbols, rituals, and shared meanings that define how learning happens in that specific space. Teachers construct these symbolic frameworks through seemingly mundane choices: the arrangement of desks signals whether collaboration or individual focus is valued, whilst morning routines communicate expectations about punctuality, respect, and readiness to learn. Mead's concept of symbolic interactionism reveals how these physical and procedural symbols become powerful meaning-making tools that students interpret and internalise, ultimately shaping their educational identity and engagement.

The most effective classroom cultures develop through consistent symbolic communication that aligns with learning objectives. Consider how a teacher's use of specific praise language creates shared understanding about what constitutes quality work, or how establishing weekly reflection rituals signals that metacognition is valued alongside content mastery. These symbolic practices become the invisible curriculum that students navigate daily, influencing everything from risk-taking in learning to peer relationships and academic self-concept.

Practitioners can harness this symbolic power by intentionally designing classroom rituals that reinforce desired learning behaviours. Simple practices like beginning each lesson with a thinking routine, using consistent visual cues for different types of activities, or creating celebration rituals for growth rather than just achievement help establish a culture where learning processes are as valued as outcomes.

Implementing symbolic interactionist principles begins with conscious attention to language choices and their meaning-making potential. Teachers should regularly audit their verbal and non-verbal communications, recognising that seemingly innocuous phrases like "struggling student" or "bright child" construct powerful identities that students internalise. Mead's concept of the "looking-glass self" reminds us that students develop self-concepts through perceived teacher expectations, making deliberate language use a cornerstone of effective practice.

Creating opportunities for collaborative meaning-making transforms traditional power dynamics within educational contexts. Rather than positioning themselves as sole knowledge authorities, teachers can facilitate student-led discussions where learners negotiate understanding together. This approach aligns with Vygotsky's social constructivist principles whilst honouring symbolic interactionism's emphasis on shared symbol creation. Simple strategies include think-pair-share activities, peer feedback sessions, and collaborative problem-solving tasks that allow students to construct knowledge through social interaction.

Most importantly, teachers must become reflective observers of classroom interactions, noting how different symbols, rituals, and communication patterns influence student behaviour and engagement. Keeping brief interaction logs or conducting periodic self-reflection on classroom dynamics helps educators identify unintentional symbolic messages. This metacognitive approach enables teachers to consciously shape the symbolic environment, ensuring that classroom interactions promote positive identity formation and meaningful learning experiences for all students.

The symbolic interactions that occur daily in educational settings profoundly shape how students perceive themselves as learners, directly influencing their academic motivation and achievement outcomes. When teachers consistently use language that positions students as capable problem-solvers rather than passive recipients of knowledge, students internalise these positive academic identities and demonstrate increased engagement with challenging tasks. Conversely, subtle linguistic choices that emphasise deficits or limitations can create self-fulfiling prophecies, as highlighted in Rosenthal and Jacobson's seminal research on teacher expectations.

The process of meaning-making through classroom interactions extends beyond verbal communication to encompass the symbolic significance of assessment feedback, seating arrangements, and participation opportunities. Students actively interpret these symbols to construct understanding of their place within the academic hierarchy. For instance, being consistently chosen for extension activities communicates high expectations and academic capability, whilst repeated assignment to remedial tasks may inadvertently signal low teacher confidence in student potential.

Practitioners can harness symbolic interactionism by deliberately crafting classroom language and structures that reinforce growth-oriented identities. This involves using process-focused praise rather than ability-based comments, creating diverse pathways for student contribution, and ensuring that all interactions communicate belief in student potential for intellectual development within the educational context.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/symbolic-interaction-theory#article","headline":"Symbolic Interactionism in Education: How Meaning is Created in Schools","description":"Understand symbolic interactionism and its implications for education. Learn how students and teachers create meaning through social interaction and how...","datePublished":"2023-11-21T12:08:49.500Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/symbolic-interaction-theory"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69513b61790b27deee69d83e_et32mv.webp","wordCount":6551},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/symbolic-interaction-theory#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Symbolic Interactionism in Education: How Meaning is Created in Schools","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/symbolic-interaction-theory"}]}]}