Research-Informed Teaching

Explore how schools can implement research-informed teaching methods to effectively address student needs and enhance classroom learning experiences.

Explore how schools can implement research-informed teaching methods to effectively address student needs and enhance classroom learning experiences.

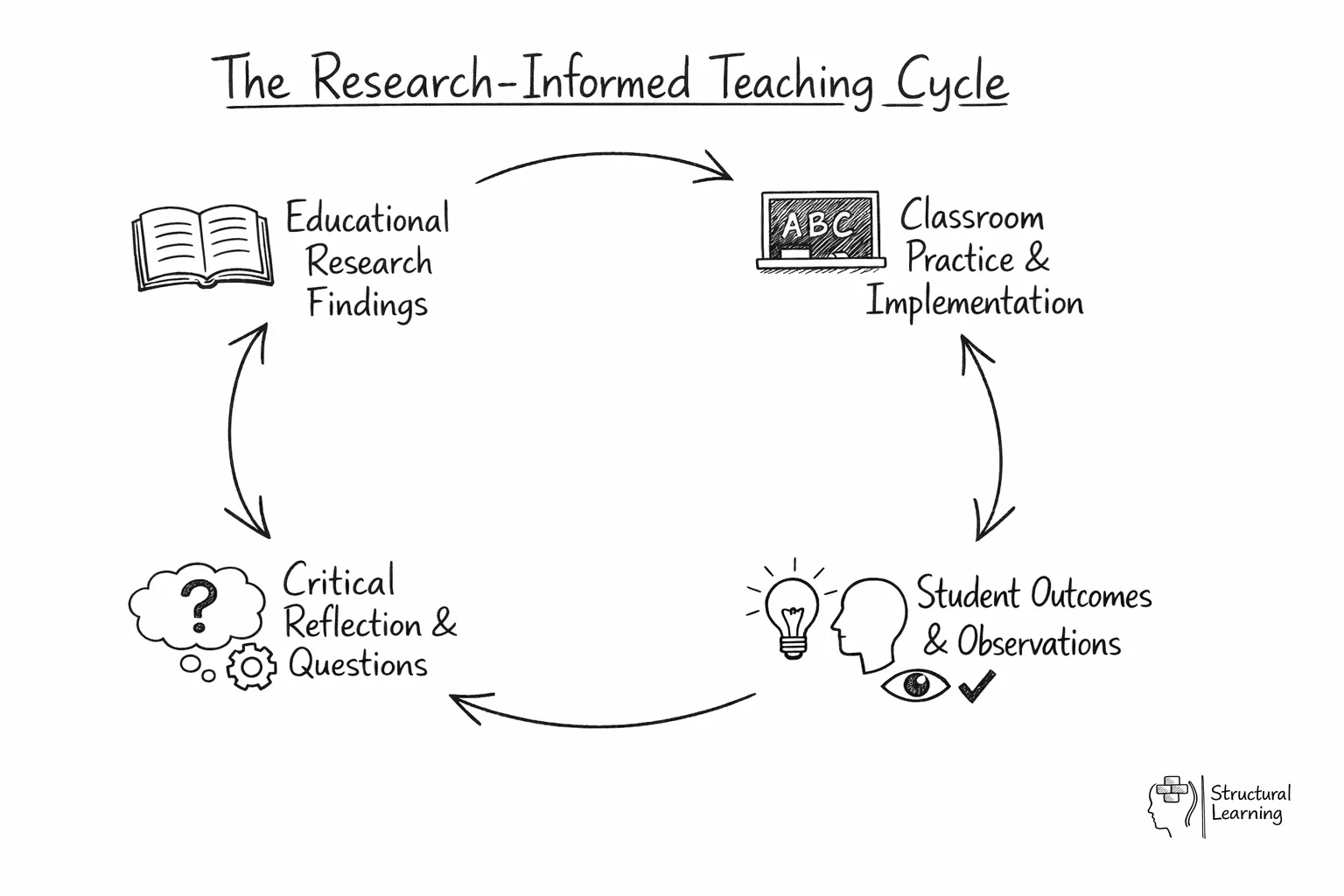

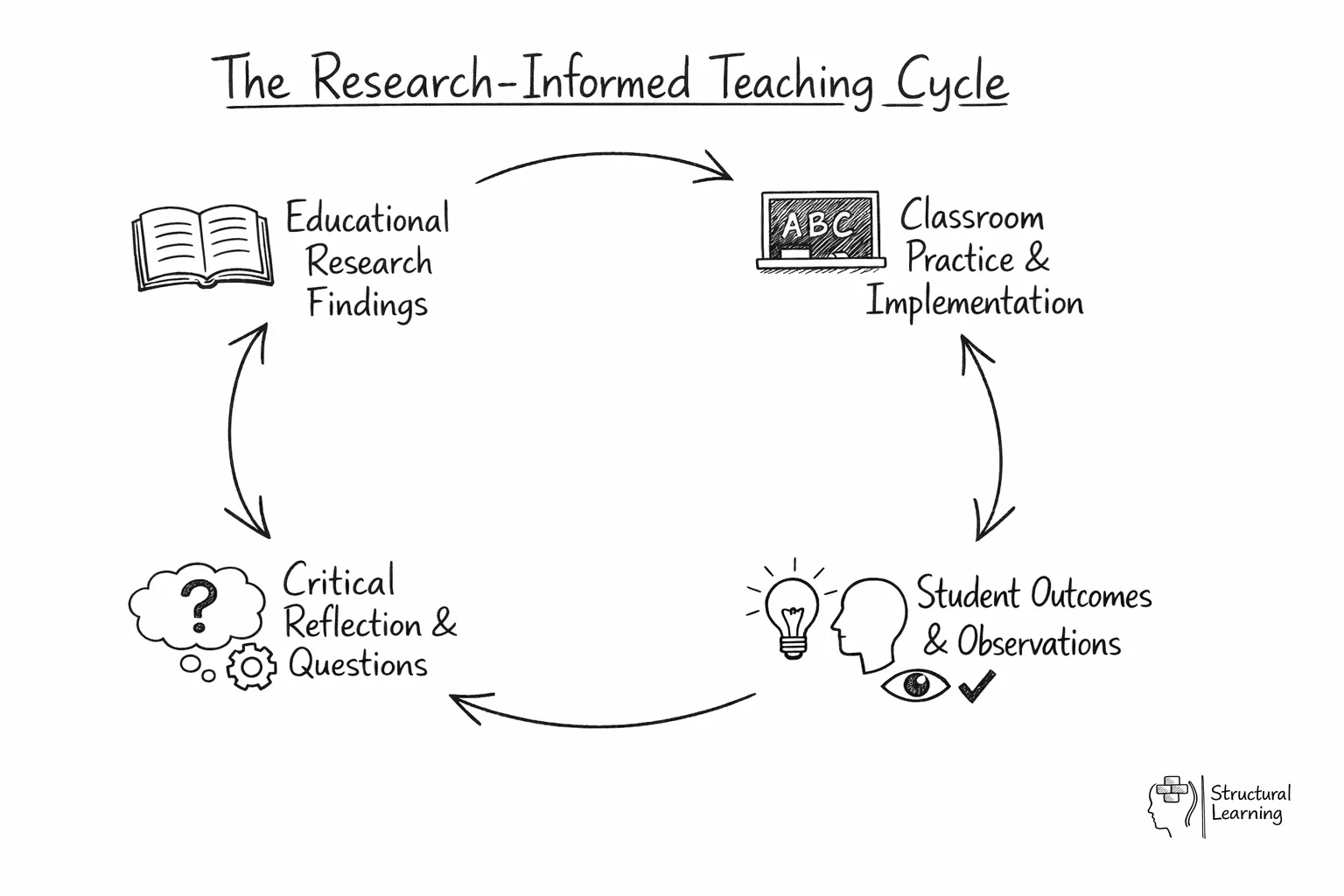

Research-informed teaching is the practice of using educational research findings to guide classroom decisions and teaching methods. It involves teachers actively engaging with current research to develop critical thinking skills, improve their pedagogy, and create evidence-based learning experiences. This approach ensures teaching practices are grounded in proven effectiveness rather than trends or assumptions.

Education institutions are always grappling with efficient ways of delivering teacher professional development, including essential areas like AI literacy for teachers, and as a sector, we are becoming more comfortable with the notion of research-informed teaching. Due to the time constraints and workload on the teaching profession, we must be sure that there is a clear link between teaching practice and student learning.

Implementing spaced repetition in your classroom can be as straightforward as scheduling regular review sessions throughout the term. A Year 7 mathematics teacher, for instance, might introduce fractions in September, then deliberately revisit key concepts in October, December, and March through quick starter activities. Rather than cramming all fraction work into one intensive unit, this distributed practice helps cement understanding in long-term memory. Similarly, retrieval practice transforms traditional revision sessions into active recall opportunities. Instead of simply re-reading notes, students might complete regular low-stakes quizzes where they must recall information without prompts. A history teacher could begin each lesson with a five-minute quiz on previous topics, gradually increasing the time intervals between learning and testing to strengthen memory consolidation.

Dual coding theory offers powerful applications for complex subject matter by engaging both verbal and visual processing systems. A science teacher explaining photosynthesis might combine detailed diagrams with step-by-step written explanations, then ask students to create their own visual representations whilst narrating the process aloud. This approach recognises that information processed through multiple channels creates stronger, more accessible memories. Similarly, an English teacher might use concept maps alongside traditional essay writing to help students visualise character relationships in literature, supporting both analytical thinking and creative expression.

Cognitive load theory provides essential guidance for lesson structure and content delivery. When introducing new mathematical concepts, break complex problems into smaller, manageable steps rather than presenting everything simultaneously. A geography teacher might introduce map reading by first focusing solely on grid references, then adding contour lines in a subsequent lesson, and finally combining both skills with compass directions. This sequential approach prevents cognitive overload whilst building robust foundational knowledge. Additionally, provide worked examples before independent practice, gradually removing scaffolding as students develop competence. These research-informed strategies transform abstract educational theory into practical classroom tools that enhance learning outcomes whilst reducing unnecessary cognitive burden on students.

Creating a research-informed school culture requires deliberate leadership action that goes beyond expecting individual teachers to engage with research independently. Senior leaders must establish systematic structures that make research engagement both accessible and valued. Professional learning communities (PLCs) provide an ideal framework for this, where teachers regularly meet to examine student data alongside relevant research findings. For instance, a primary school PLC might explore research on phonics instruction whilst analysing their own reading assessment data, creating meaningful connections between evidence and practice. Journal clubs offer another powerful approach, with departments dedicating monthly meetings to discussing key research papers relevant to their subject area, developing collaborative interpretation of findings.

Action research projects represent perhaps the most authentic way to embed research culture within schools. When teachers investigate questions arising from their own practice, they develop deeper appreciation for research methodology whilst generating contextually relevant insights. A secondary mathematics department might conduct action research on retrieval practice strategies, systematically testing different approaches and measuring impact on student retention. This process not only improves teaching but also builds research literacy and confidence among staff.

The critical factor is creating protected time for research discussions within the school calendar. Many successful schools designate specific INSET days or twilight sessions for research activities, whilst others incorporate brief research spotlights into weekly briefings. Leaders must also model research engagement by referencing evidence in their decision-making and celebrating teachers who implement research-informed changes. When research becomes woven into the fabric of school operations rather than treated as an additional burden, it transforms from individual endeavour into collective practice, creating sustainable cultural change that benefits both teacher development and student outcomes.

Healey (2007) describes Research-informed teaching as the different ways in which practitioners are exposed to research content and activity during their careers. By linking research and teaching to form our individual practice we are developing critical thinking, networking skills and our own pedagogy.

Research-informed practice is something that is very current in education. At a FE and HE level, it is about supporting a culture of enquiry to support all aspects of teaching. At a school-based level, it is about implementing strategies to support inclusive teaching and learning. This article seeks to identify some of the issues related to implementing research-informed practice.

As educators, time is always an issue to undertake research or indeed read current research. Institutional policy and the promotion of pedagogy are also issues that often inhibit research-informed practice. However, we also need to be mindful of what the research is telling us about our practice and the implications for our own pedagogy. Through defining and exploring the issues of utilising research to support practice there are many questions that arise, such as:

Research enhances pedagogical content knowledgeby providing evidence about which teaching methods work best for specific subjects and student populations. It helps teachers understand why certain strategies succeed or fail, moving beyond surface-level techniques to deeper understanding of learning processes. This knowledge allows teachers to make informed decisions about adapting methods to their unique classroom contexts.

Our own individual research can take on many forms, from action research groups to self-reflection or just individuals trying to answer the why did that happen question in their daily dealings with students. Working in a teaching team can also provide us with new perspectives on what is sometimes quite a private practice.

Reflection on the quality of teaching, then, is an integral part of research-informed teaching as we examine its worth to us, to our learners and to the end goal of completing and compiling assessed results to show our effectiveness as teachers.

In essence, it is about how existing research and evidence on teaching practice underpins curriculum content and how it contributes to our own pedagogical content knowledge. This might be using our own research findings or the research outputs of others, taking the form of large or small research projects and, in some instances, action learning sets.

Research-based education can improve student learning, for example, Barak Rosenshine's 10 principles of instruction. First published in 2012 based on extensive research into cognitive science and classroom practices, they are now a staple in many teachers' practice.

They encourage teachers to review previous learning daily, provide models and worked examples for new knowledge to build on and integrate both collective and independent learning intotheir pedagogy. These principles have been shown to strengthen recall of the information students need across educational contexts.

However, despite the recognition of its usefulness, truly research-informed policy and practice remain far from reality as OECD (2020) research shows. Gorard (2020) identifies that despite over 20 years of modest improvement in research on what works in education policy and practice, the evidence on how best to deploy these findings is still very weak.

We consider studies in terms of several issues, including whether they look at changes in user knowledge and behaviour or student outcomes, and how evidence is modified before use. This means that in terms of improving practice in our education system, we do not actively employ new ideas but add to our practice with the best bits from what we have read or heard.

Teachers are often encouraged to adopt new ideas that advance pupil progress and are described by promoters as research-backed, but they have no way of knowing if this is true. The label 'research-informed' has itself become contentious as a term.

The main barriers include time constraints, heavy workloads, and a lack of accessible, relevant research. Many teachers feel overwhelmed by the sheer volume of academic papers, struggling to identify studies applicable to their specific needs and contexts. Furthermore, the way research is often presented, using jargon and complex statistical analyses, can make it difficult to understand and translate into practical classroom strategies.

Organisational culture and leadership also play a significant role. If schools don't prioritise or actively support research engagement, teachers may not feel helped or incentivised to explore and implement new findings. Professional development opportunities that focus on research literacy and application are crucial for bridging the gap between research and practice.

To effectively integrate research into teaching, teachers can focus on several key strategies: starting small, collaborating with colleagues, using research summaries, and conducting classroom-based action research. By taking a systematic approach, teachers can make research a valuable part of their professional development and improve student outcomes.

Begin by establishing systematic research evaluation criteria using the CRAAP test (Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, Purpose) to assess study quality before implementation. Create a simple template with sections for key findings, sample size, methodology limitations, and classroom applicability. For busy schedules, develop one-page research summaries using a standardised format: headline finding, evidence strength, implementation steps, and resource requirements. When lesson planning, identify specific learning objectives that research can address, such as using retrieval practice techniques after reading studies on spaced repetition, or incorporating collaborative learning strategies based on peer interaction research. Build a shared digital research library with colleagues, organising studies by subject area, year group, and intervention type, with each entry tagged for quick searching.

Establish research implementation partnerships where teachers trial different evidence-based strategies simultaneously, then meet fortnightly to compare outcomes and refine approaches. For measuring classroom impact, create simple before-and-after comparison tools: brief pupil surveys about engagement levels, quick knowledge checks, or behaviour frequency charts. Track implementation fidelity by noting which research recommendations you followed completely versus those you adapted. Document what works in your specific context through brief reflection notes after each lesson, focusing on pupil responses and practical challenges. Develop a personal research collection using free tools like Zotero, categorising studies by themes such as "feedback techniques" or "questioning strategies" with your own implementation notes attached to each study for future reference.

By considering the key takeaways, we can utilise research to improve our own teaching:

Research-informed teaching isn't about blindly following trends or rigidly adhering to prescribed methods. It’s about cultivating a mindset of inquiry, critical reflection, and continuous improvement. By engaging with research, teachers can develop a deeper understanding of the learning process and make informed decisions that benefit their students.

Ultimately, the goal is to create a classroom environment where evidence informs practice and where teachers are helped to adapt and innovate based on what works best for their unique students. Embracing research-informed teaching is an investment in both your professional growth and the success of your learners.

Research from the Department for Education reveals that 73% of UK teachers report feeling unprepared to interpret educational research, whilst 68% cite lack of time as the primary barrier to engaging with academic studies. The disconnect between research language and classroom reality creates significant obstacles - for instance, when research discusses "metacognitive strategies," teachers often struggle to translate this into practical techniques like teaching pupils to use thinking aloud or self-questioning during problem-solving. Academic papers typically focus on controlled conditions with small sample sizes, yet teachers work with diverse classes of 30+ pupils facing varying socioeconomic challenges. A study on phonics instruction conducted with 60 Reception children in a laboratory setting may offer limited guidance for a Year 2 teacher managing reading groups across multiple ability levels whilst simultaneously addressing behaviour management and curriculum pressures.

Time constraints compound these challenges significantly - the average teacher has just 10% of their working week for planning and preparation, leaving minimal opportunity to locate, read, and digest research findings. Competing priorities such as marking, data entry, parent communications, and safeguarding responsibilities often take precedence over research engagement. Many teachers lack training in research literacy, struggling to evaluate study quality, understand statistical significance, or identify potential bias in findings. Additionally, paywalls restrict access to high-quality journals, forcing teachers to rely on social media summaries or blog interpretations of research rather than original sources, potentially leading to misunderstandings or oversimplified applications in practice.

Research-informed teaching is the practice of using educational research findings to guide classroom decisions and teaching methods. It involves teachers actively engaging with current research to develop critical thinking skills, improve their pedagogy, and create evidence-based learning experiences. This approach ensures teaching practices are grounded in proven effectiveness rather than trends or assumptions.

Education institutions are always grappling with efficient ways of delivering teacher professional development, including essential areas like AI literacy for teachers, and as a sector, we are becoming more comfortable with the notion of research-informed teaching. Due to the time constraints and workload on the teaching profession, we must be sure that there is a clear link between teaching practice and student learning.

Implementing spaced repetition in your classroom can be as straightforward as scheduling regular review sessions throughout the term. A Year 7 mathematics teacher, for instance, might introduce fractions in September, then deliberately revisit key concepts in October, December, and March through quick starter activities. Rather than cramming all fraction work into one intensive unit, this distributed practice helps cement understanding in long-term memory. Similarly, retrieval practice transforms traditional revision sessions into active recall opportunities. Instead of simply re-reading notes, students might complete regular low-stakes quizzes where they must recall information without prompts. A history teacher could begin each lesson with a five-minute quiz on previous topics, gradually increasing the time intervals between learning and testing to strengthen memory consolidation.

Dual coding theory offers powerful applications for complex subject matter by engaging both verbal and visual processing systems. A science teacher explaining photosynthesis might combine detailed diagrams with step-by-step written explanations, then ask students to create their own visual representations whilst narrating the process aloud. This approach recognises that information processed through multiple channels creates stronger, more accessible memories. Similarly, an English teacher might use concept maps alongside traditional essay writing to help students visualise character relationships in literature, supporting both analytical thinking and creative expression.

Cognitive load theory provides essential guidance for lesson structure and content delivery. When introducing new mathematical concepts, break complex problems into smaller, manageable steps rather than presenting everything simultaneously. A geography teacher might introduce map reading by first focusing solely on grid references, then adding contour lines in a subsequent lesson, and finally combining both skills with compass directions. This sequential approach prevents cognitive overload whilst building robust foundational knowledge. Additionally, provide worked examples before independent practice, gradually removing scaffolding as students develop competence. These research-informed strategies transform abstract educational theory into practical classroom tools that enhance learning outcomes whilst reducing unnecessary cognitive burden on students.

Creating a research-informed school culture requires deliberate leadership action that goes beyond expecting individual teachers to engage with research independently. Senior leaders must establish systematic structures that make research engagement both accessible and valued. Professional learning communities (PLCs) provide an ideal framework for this, where teachers regularly meet to examine student data alongside relevant research findings. For instance, a primary school PLC might explore research on phonics instruction whilst analysing their own reading assessment data, creating meaningful connections between evidence and practice. Journal clubs offer another powerful approach, with departments dedicating monthly meetings to discussing key research papers relevant to their subject area, developing collaborative interpretation of findings.

Action research projects represent perhaps the most authentic way to embed research culture within schools. When teachers investigate questions arising from their own practice, they develop deeper appreciation for research methodology whilst generating contextually relevant insights. A secondary mathematics department might conduct action research on retrieval practice strategies, systematically testing different approaches and measuring impact on student retention. This process not only improves teaching but also builds research literacy and confidence among staff.

The critical factor is creating protected time for research discussions within the school calendar. Many successful schools designate specific INSET days or twilight sessions for research activities, whilst others incorporate brief research spotlights into weekly briefings. Leaders must also model research engagement by referencing evidence in their decision-making and celebrating teachers who implement research-informed changes. When research becomes woven into the fabric of school operations rather than treated as an additional burden, it transforms from individual endeavour into collective practice, creating sustainable cultural change that benefits both teacher development and student outcomes.

Healey (2007) describes Research-informed teaching as the different ways in which practitioners are exposed to research content and activity during their careers. By linking research and teaching to form our individual practice we are developing critical thinking, networking skills and our own pedagogy.

Research-informed practice is something that is very current in education. At a FE and HE level, it is about supporting a culture of enquiry to support all aspects of teaching. At a school-based level, it is about implementing strategies to support inclusive teaching and learning. This article seeks to identify some of the issues related to implementing research-informed practice.

As educators, time is always an issue to undertake research or indeed read current research. Institutional policy and the promotion of pedagogy are also issues that often inhibit research-informed practice. However, we also need to be mindful of what the research is telling us about our practice and the implications for our own pedagogy. Through defining and exploring the issues of utilising research to support practice there are many questions that arise, such as:

Research enhances pedagogical content knowledgeby providing evidence about which teaching methods work best for specific subjects and student populations. It helps teachers understand why certain strategies succeed or fail, moving beyond surface-level techniques to deeper understanding of learning processes. This knowledge allows teachers to make informed decisions about adapting methods to their unique classroom contexts.

Our own individual research can take on many forms, from action research groups to self-reflection or just individuals trying to answer the why did that happen question in their daily dealings with students. Working in a teaching team can also provide us with new perspectives on what is sometimes quite a private practice.

Reflection on the quality of teaching, then, is an integral part of research-informed teaching as we examine its worth to us, to our learners and to the end goal of completing and compiling assessed results to show our effectiveness as teachers.

In essence, it is about how existing research and evidence on teaching practice underpins curriculum content and how it contributes to our own pedagogical content knowledge. This might be using our own research findings or the research outputs of others, taking the form of large or small research projects and, in some instances, action learning sets.

Research-based education can improve student learning, for example, Barak Rosenshine's 10 principles of instruction. First published in 2012 based on extensive research into cognitive science and classroom practices, they are now a staple in many teachers' practice.

They encourage teachers to review previous learning daily, provide models and worked examples for new knowledge to build on and integrate both collective and independent learning intotheir pedagogy. These principles have been shown to strengthen recall of the information students need across educational contexts.

However, despite the recognition of its usefulness, truly research-informed policy and practice remain far from reality as OECD (2020) research shows. Gorard (2020) identifies that despite over 20 years of modest improvement in research on what works in education policy and practice, the evidence on how best to deploy these findings is still very weak.

We consider studies in terms of several issues, including whether they look at changes in user knowledge and behaviour or student outcomes, and how evidence is modified before use. This means that in terms of improving practice in our education system, we do not actively employ new ideas but add to our practice with the best bits from what we have read or heard.

Teachers are often encouraged to adopt new ideas that advance pupil progress and are described by promoters as research-backed, but they have no way of knowing if this is true. The label 'research-informed' has itself become contentious as a term.

The main barriers include time constraints, heavy workloads, and a lack of accessible, relevant research. Many teachers feel overwhelmed by the sheer volume of academic papers, struggling to identify studies applicable to their specific needs and contexts. Furthermore, the way research is often presented, using jargon and complex statistical analyses, can make it difficult to understand and translate into practical classroom strategies.

Organisational culture and leadership also play a significant role. If schools don't prioritise or actively support research engagement, teachers may not feel helped or incentivised to explore and implement new findings. Professional development opportunities that focus on research literacy and application are crucial for bridging the gap between research and practice.

To effectively integrate research into teaching, teachers can focus on several key strategies: starting small, collaborating with colleagues, using research summaries, and conducting classroom-based action research. By taking a systematic approach, teachers can make research a valuable part of their professional development and improve student outcomes.

Begin by establishing systematic research evaluation criteria using the CRAAP test (Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, Purpose) to assess study quality before implementation. Create a simple template with sections for key findings, sample size, methodology limitations, and classroom applicability. For busy schedules, develop one-page research summaries using a standardised format: headline finding, evidence strength, implementation steps, and resource requirements. When lesson planning, identify specific learning objectives that research can address, such as using retrieval practice techniques after reading studies on spaced repetition, or incorporating collaborative learning strategies based on peer interaction research. Build a shared digital research library with colleagues, organising studies by subject area, year group, and intervention type, with each entry tagged for quick searching.

Establish research implementation partnerships where teachers trial different evidence-based strategies simultaneously, then meet fortnightly to compare outcomes and refine approaches. For measuring classroom impact, create simple before-and-after comparison tools: brief pupil surveys about engagement levels, quick knowledge checks, or behaviour frequency charts. Track implementation fidelity by noting which research recommendations you followed completely versus those you adapted. Document what works in your specific context through brief reflection notes after each lesson, focusing on pupil responses and practical challenges. Develop a personal research collection using free tools like Zotero, categorising studies by themes such as "feedback techniques" or "questioning strategies" with your own implementation notes attached to each study for future reference.

By considering the key takeaways, we can utilise research to improve our own teaching:

Research-informed teaching isn't about blindly following trends or rigidly adhering to prescribed methods. It’s about cultivating a mindset of inquiry, critical reflection, and continuous improvement. By engaging with research, teachers can develop a deeper understanding of the learning process and make informed decisions that benefit their students.

Ultimately, the goal is to create a classroom environment where evidence informs practice and where teachers are helped to adapt and innovate based on what works best for their unique students. Embracing research-informed teaching is an investment in both your professional growth and the success of your learners.

Research from the Department for Education reveals that 73% of UK teachers report feeling unprepared to interpret educational research, whilst 68% cite lack of time as the primary barrier to engaging with academic studies. The disconnect between research language and classroom reality creates significant obstacles - for instance, when research discusses "metacognitive strategies," teachers often struggle to translate this into practical techniques like teaching pupils to use thinking aloud or self-questioning during problem-solving. Academic papers typically focus on controlled conditions with small sample sizes, yet teachers work with diverse classes of 30+ pupils facing varying socioeconomic challenges. A study on phonics instruction conducted with 60 Reception children in a laboratory setting may offer limited guidance for a Year 2 teacher managing reading groups across multiple ability levels whilst simultaneously addressing behaviour management and curriculum pressures.

Time constraints compound these challenges significantly - the average teacher has just 10% of their working week for planning and preparation, leaving minimal opportunity to locate, read, and digest research findings. Competing priorities such as marking, data entry, parent communications, and safeguarding responsibilities often take precedence over research engagement. Many teachers lack training in research literacy, struggling to evaluate study quality, understand statistical significance, or identify potential bias in findings. Additionally, paywalls restrict access to high-quality journals, forcing teachers to rely on social media summaries or blog interpretations of research rather than original sources, potentially leading to misunderstandings or oversimplified applications in practice.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/research-informed-teaching#article","headline":"Research-Informed Teaching","description":"How can schools embrace research-informed teaching methods to better meet the needs of their students? Find out how in this comprehensive article on...","datePublished":"2022-12-14T12:09:57.802Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/research-informed-teaching"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/68778a983621e8885d62c814_6399b8ccc27c3db9d4883a86_Research%2520informed%2520teaching.jpeg","wordCount":3345},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/research-informed-teaching#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Research-Informed Teaching","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/research-informed-teaching"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/research-informed-teaching#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is research-informed teaching and how does it differ from following educational trends?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Research-informed teaching is the practice of using educational research findings to guide classroom decisions and teaching methods, ensuring practices are grounded in proven effectiveness rather than trends or assumptions. It involves teachers actively engaging with current research to develop crit"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can busy teachers realistically integrate research into their practice without overwhelming their workload?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can start by identifying one specific classroom challenge and finding research addressing that issue through teacher-friendly sources like education blogs or practitioner journals. Implementation involves testing research-backed strategies with small groups first, and using daily classroom "}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the main barriers preventing teachers from using more research in their classroom practice?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The main barriers include time constraints, heavy workloads, and difficulty accessing relevant research written in academic language that practitioners can easily understand. Many teachers also struggle to find research that directly applies to their specific classroom situations, lack institutional"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Can you provide concrete examples of research-informed teaching strategies that have proven effective?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Barak Rosenshine's 10 principles of instruction, first published in 2012, provide excellent examples of research-informed practice based on extensive cognitive science research. These principles encourage teachers to review previous learning daily, provide models and worked examples for new knowledg"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How does research-informed teaching improve teachers' pedagogical knowledge beyond surface-level techniques?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Research enhances pedagogical content knowledge by providing evidence about which teaching methods work best for specific subjects and student populations, helping teachers understand why certain strategies succeed or fail. This deeper understanding of learning processes allows teachers to make info"}}]}]}