Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve

Explore the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve and apply evidence-based spacing and retrieval strategies to enhance student retention and learning outcomes.

Explore the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve and apply evidence-based spacing and retrieval strategies to enhance student retention and learning outcomes.

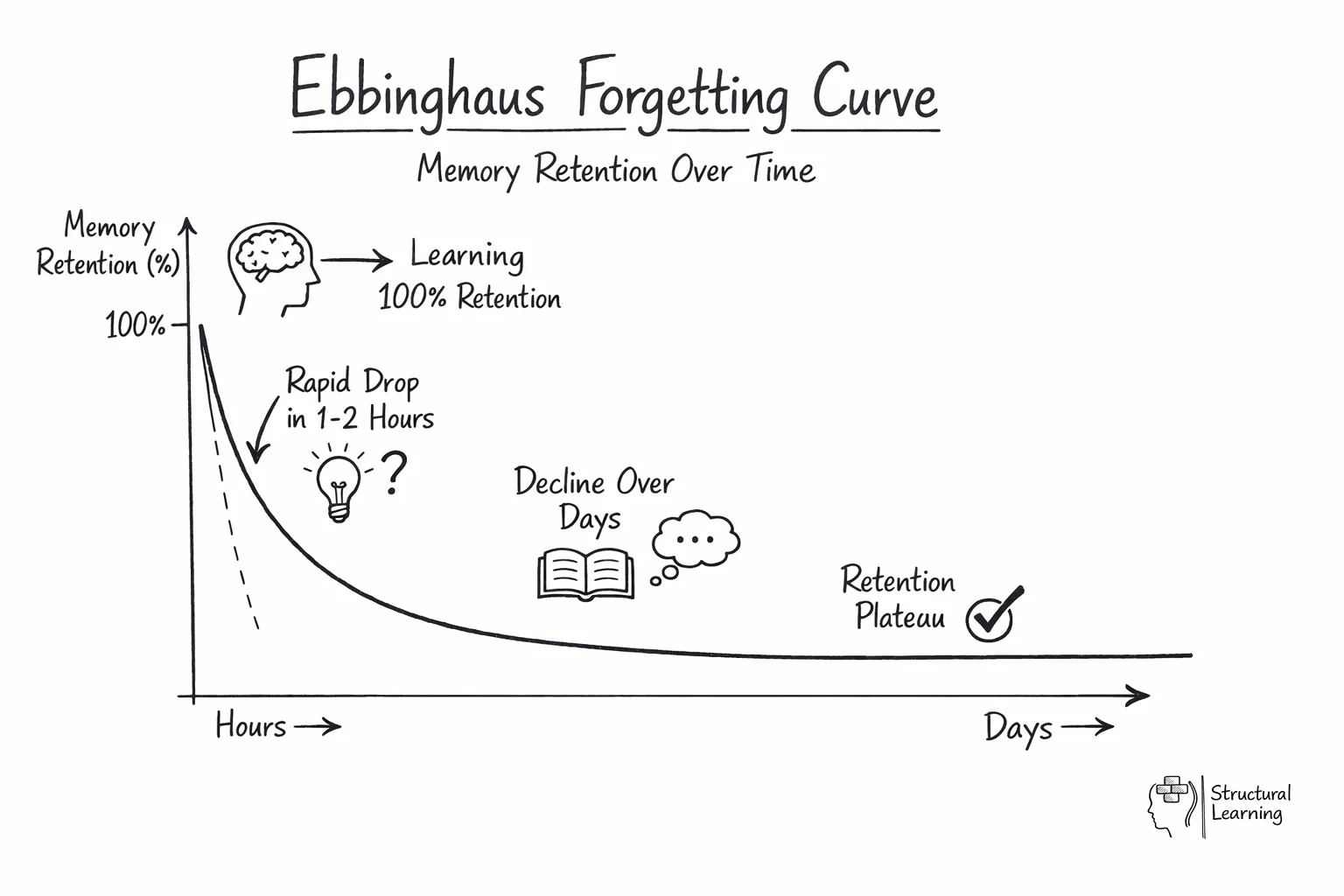

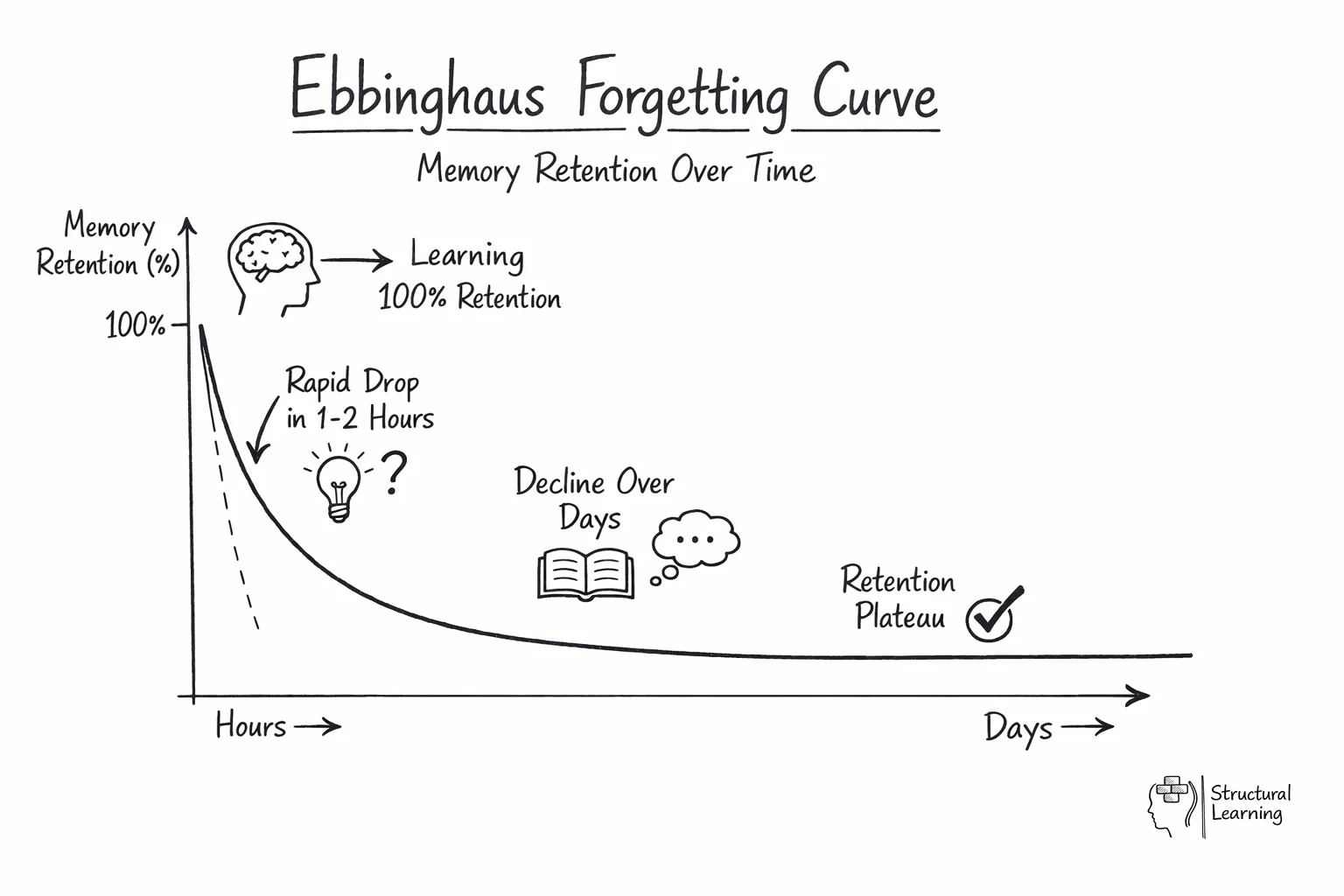

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve is a fundamental concept in the psychology of memory, developed by Hermann Ebbinghaus in the late 19th century. It provides a visual representation of how quickly information fades from our memory over time if it is not actively reinforced.

The curve illustrates that memory retention drops sharply within the first few hours after learning, often dramatically so due to working memory decay. This decline is not linear; instead, it follows an exponential pattern, with rapid initial forgetting that eventually slows down over subsequent days. This phenomenon underscores the critical role of timely review and reinforcement to counteract the natural forgetting process.

For educators, understanding the dynamics of this curve is key to designing effective teaching strategies that help students retain information more effectively. By recognising when memory loss is most pronounced, teachers can implement timely interventions, such as spaced repetition and active recall, that maximise retention and deepen learning.

In this article, we will explore the theoretical foundations of the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve, discuss how it can be practically applied in educational contexts, and offer strategies to help combat forgetting in the classroom.

Key Insights:

The forgetting curve shows that we forget the majority of new information soon after it is initially learnt. Ebbinghaus defined forgetting as an ability to recall information in the absence of any cues.

Our ability to recognise new information does not follow the same pattern; being presented with cues or multiple-choice options increases the accuracy of our memory.

While the curve describes a general trend to forget new information when there is no attempt to retain it, there will be individual variations in the shape of the curve.

New information that is of significant value, is related to a major event, or offers a surprising contradiction to previously learnt material, is less likely to be forgotten at such a rapid rate.

Time has the greatest impact on the decline of memory; memory retention over time is very poor in the absence of any attempt to retain the new information. The total amount of information that is forgotten increases with time, but the majority of this happens soon after learning has occurred.

The quality of learning also has a significant impact on whether the new material will be resistant to the steep decline in memory observed by Ebbinghaus. Information that is fully understood or deeply processed is likely to be forgotten less quickly.

Similarly, if the new information is of personal significance or has a practical application, it is more likely to be remembered well, partly because the person is more motivated to encode it effectively into their long-term memory.

When new information is similar or related to prior learning, it can impact the decline in memory in both directions.

Retention increases if new knowledge is assimilated into a pre-existing schema of related information in the long-term memory because the prior learning offers an abundance of cues for the new information.

However, when information is similar but unrelated to something that has been previously learnt it can increase the decline in memory for the new information (proactive interference) or the previously learnt information (retroactive interference).

Both types of interference can be seen when learning a new foreign language; words from a previously learnt foreign language may be forgotten when the new language is learnt (retroactive) or it can be more difficult to learn new vocabulary if it is too similar to the previously learnt vocabulary.

There will be individual differences in memory strength, even for nonsense syllables (three-letter ‘words’ that have no meaning). Some of the reasons for this variation include:

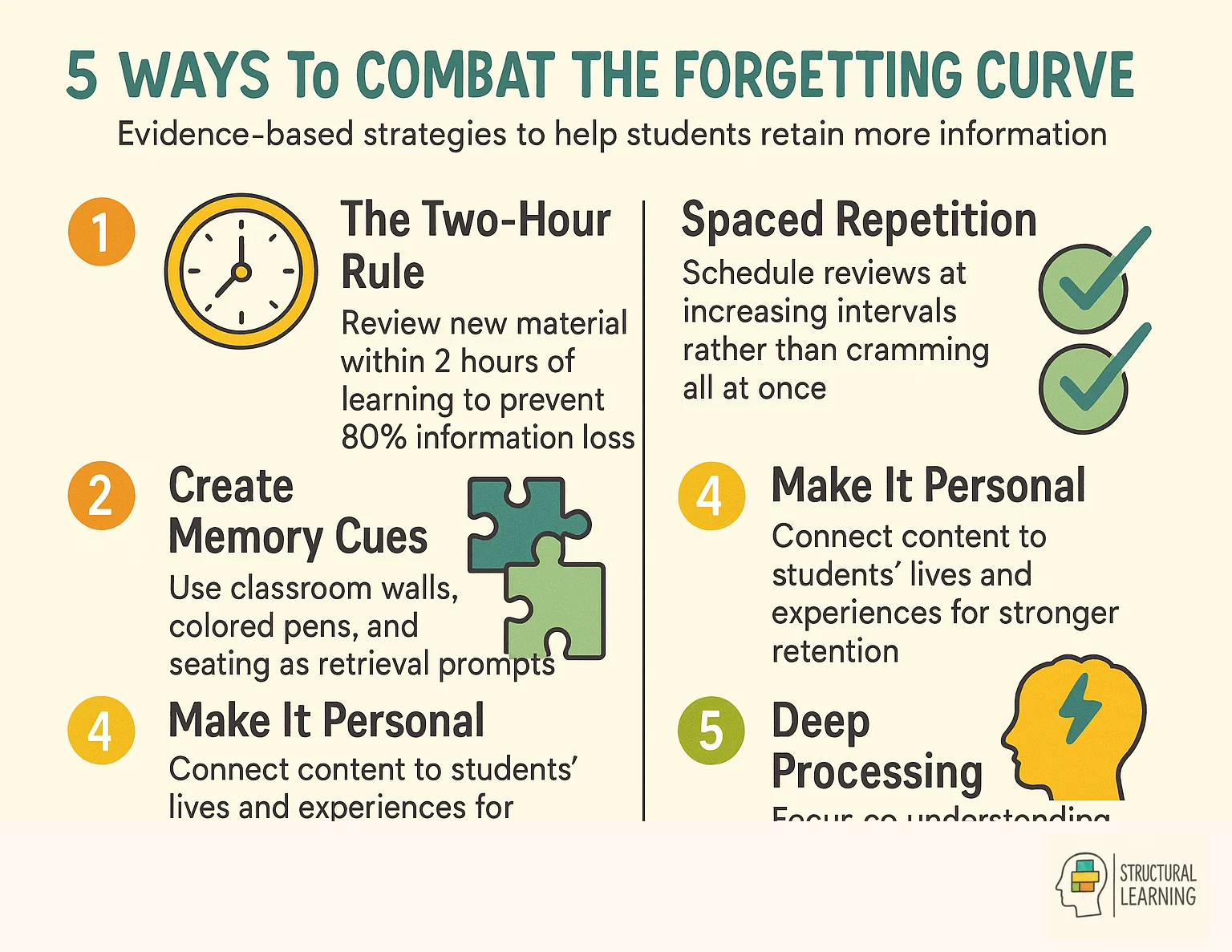

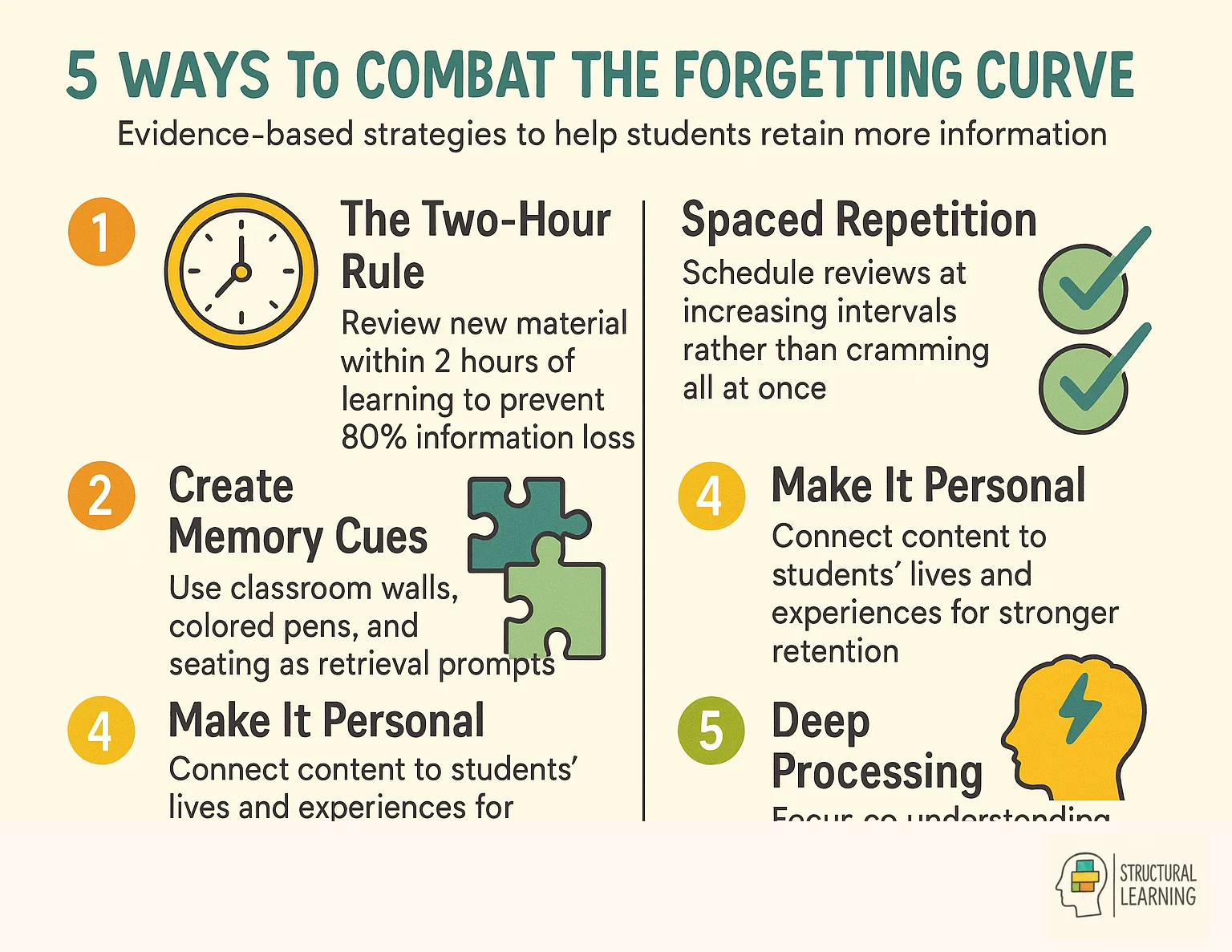

Teachers can combat the forgetting curve through three evidence-based strategies: implementing spaced repetition by reviewing material at increasing intervals, using active recall techniques like frequent low-stakes quizzing, and creating meaningful connections between new information and students' prior knowledge. Research shows that reviewing material within 24 hours can increase retention by up to 80%, while combining these techniques can help students retain information for months or even years.

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve describes the decline in memory when there is no attempt to retain the new information. Any strategy that is designed to increase retention will challenge the decline in memory and flatten the forgetting curve.

Repeated Retrieval Practice

The most effective way to challenge the forgetting curve is through repeated retrieval practice. The first attempt to retrieve the new information should be soon after it was originally learnt, with subsequent retrievals becoming increasingly spread out over longer time periods (spaced repetition).

Each successful retrieval increases the number of cues associated with the information, which flattens the forgetting curve and makes it possible to extend the length of time between future retrievals.

Techniques to Improve Memory

Developing techniques to improve memory will reduce the rate of forgetting, even in the absence of any further attempts to retain the new information.

Mnemonic devices focus on encoding new information in a way that will make it easier to retrieve it in the future. Using acronyms can be very successful when it is necessary to learn the order of a list of words:

Never eat shredded wheat: the clockwise order of the compass points (North, East, South, West).

Richard of York gave battle in vain: the order of colours in a rainbow.

Another popular technique is creating a memory palace. This involves developing a mental image of a real or imaginary location, often a house or palace, that has vivid and distinct locations throughout it.

When trying to memorise a list of words, images, or facts, each one is associated with one of the locations in a vivid or meaningful way. Visualising the memory palace then acts as a prompt to remember the new material.

Memory Prompts During Learning

Having an awareness of memory prompts and incorporating them into the learning process will make it easier to recall the newly learnt information at a later date and slow down the steep decline in memory.

Linking new information to prior learning is one of the most effective ways to achieve this; incorporating the new material into a pre-existing schema will allow it to benefit from all of the existing memory prompts and cues that are already in place.

Alternatively, consider using physical cues or the environment as a memory prompt. For example, writing key terms in a different colour pen, in capital letters, or in a certain position on a piece of paper can act as a memory prompt during subsequent recall attempts.

It can also help to learn new material in the same, or similar, environment to where it will need to be recalled; revising in an exam hall in silence would be more effective than revising in a bedroom with music.

The forgetting curve reveals that without review, students lose up to 70% of new information within 24 hours, making immediate and systematic review essential for effective teaching. Teachers should structure lessons to include brief reviews at the start of each class, schedule spaced practice sessions throughout units, and design homework that reinforces rather than introduces concepts. This understanding transforms lesson planning from linear progression to cyclical reinforcement patterns.

Understanding how students forget can allow teachers to make changes to their practice to challenge the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve and increase their students’ memory retention. The following approaches are recommended to teachers in response to Ebbinghaus’ research:

1. Regular Retrieval Practice

Repeated exposure to information strengthens memory retention and flattens the forgetting curve. Asking students to retrieve information forces them to revisit the information, even if they recall it incorrectly, due to the corrective feedback that they receive.

The first retrieval practice should be soon after the new material has been learnt, preferably the following day or in the next lesson. The period of time between each subsequent retrieval should be longer than the previous one. Using spaced intervals are also recommended in Rosenshine’s principles of instruction:

It is better to interleave two or more topics together during retrieval practice; this allows the material to be revisited more often and spaced practice to be spread out over time.

2. Review Schemes of Work

Schemes of work should be reviewed to ensure they include regular opportunities for spaced retrieval practice and that topics are arranged by increasing level of difficulty to build on prior learning.

Curriculumplans should be designed to promote mastery by using scaffolding and dividing complex information into smaller and more manageable chunks.

By reducing the volume of new material that students need to learn in each part of the lesson, they are more likely to encode it effectively into their long-term memories.

Lesson plans should make the links to prior learning explicit to students as this will help them assimilate the new information into a pre-existing schema.

It is also helpful to list the keywords and related keywords for each topic as this will help students to reorganise the new information, provide more cues to aid recall, and allow them to make links between related topics.

Promote Metacognition

Encourage students to reflect on what they have learned, but also how they learned it. This will help students to understand which strategies are most effective at improving memory retention.

This is particularly important after a test or assessment, and part of the teacher’s feedback should be focussed on the effectiveness of the revision strategies and processes that the student used.

Being able to accurately recall information gives students a distinct advantage in our current educational system and is a precursor to being able to effectively manipulate and evaluate that information.

Practising active recall strategies and using memory-enhancing techniques as often as possible will challenge the decline in memory that occurs in the absence of retrieval attempts and memory retention strategies.

Active recall requires students to access information from their long-term memory in the absence of any memory cues or prompts.

A brain dump is one of the most simple and effective ways to achieve this. It involves writing down everything the student can remember about a given topic within a specified time frame.

There are no restrictions or demands about what information can be recalled, which means that students will often also benefit from hearing what their peers have been able to recall. Answering practice questions, defining or generating a list of keywords, or completing an assessment are other useful examples of active recall.

Activities that involve passive recall are much less effective at improving memory. These include:

Summarising a page of text or using flashcards can be classified as being either active or passive recall depending on how each task is approached.

Summarising a page of text is a passive recall activity if the page of text is available throughout the task. However, it becomes an active recall activity if the student reads the text, puts it away, and then writes a summary from memory.

The latter approach should be used for answering practice questions; always read the text and hide it before attempting to answer a question about it.

Using flashcards to aid revision by reading the question and then turning over to ‘confirm’ you know what the answer was involves passive recall at best. However, writing down the answer or answering the question out loud before turning over the card to check the answer would be an example of active recall.

Mnemonic techniques are an effective way to boost memory, especially when it is necessary to remember a list of words in order. Students may also benefit from using dual codingto memorise key words or definitions; this involves pairing the new material with a particularly vivid image to make it more memorable.

While groundbreaking, Ebbinghaus's original research used nonsense syllables rather than meaningful content, which may not accurately reflect how students learn complex subject matter with personal relevance. The curve also doesn't account for individual differences in learning styles, prior knowledge, or emotional connections to material, all of which can significantly impact retention rates. Modern research suggests that meaningful, contextualized learning can create much flatter forgetting curves than Ebbinghaus originally documented.

While the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve has been a foundational concept in understanding how memory retention declines over time, recognise its limitations. The original research conducted by Hermann Ebbinghaus focused on memorizing nonsensical syllables in a controlled environment, which is far removed from the complexity of real-world learning. Therefore, while the Forgetting Curve provides useful insights into the general pattern of memory loss, several limitations should be acknowledged to apply this theory effectively to different learning contexts. Below, we discuss five potential limitations of Ebbinghaus's theory.

By understanding these limitations, educators can more effectively apply and adapt Ebbinghaus's insights to various learning scenarios, allowing for improved methods to enhance long-term memory retention.

Teachers can deepen their understanding through Hermann Ebbinghaus's original work 'Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology' (1885) and modern applications in books like 'Make It Stick' by Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel. Educational psychology journals regularly publish studies on spaced repetition and memory retention, while organisations like the Learning Scientists provide free, research-based resources for classroom implementation. Many teacher training programs now include modules on cognitive science and memory research.

Subsequent research has supported the concept of an exponential forgetting curve and the conclusions that can be drawn from Ebbinghaus’ research to challenge the decline in memory have been shown to effectively improve memory in real-life settings. To learn more about these studies and the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve, please use the links below.

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve is a visual representation showing how quickly information fades from memory over time without active reinforcement. It demonstrates that memory retention drops sharply within the first few hours after learning, with students potentially losing up to 80% of information. Understanding this curve helps teachers implement timely interventions to maximise student retention and design more effective teaching strategies.

The most critical period is within the first two hours after learning, when the sharpest decline in memory occurs. Research shows that reviewing material within 24 hours can increase retention by up to 80%. This makes immediate review after lessons essential rather than optional for preventing massive information loss.

Teachers should schedule the first retrieval practice soon after initial learning, then gradually increase the intervals between subsequent reviews. Each successful retrieval strengthens memory and allows for longer gaps between future practice sessions. This approach flattens the forgetting curve and helps students retain information for months or even years.

Teachers can transform classroom environments into memory aids by using coloured pens, strategic seating arrangements, and wall displays as retrieval cues. They should also connect new content to students' personal experiences and prior knowledge, as information with personal significance creates stronger memory resistance. Low-stakes quizzing and active recall techniques are more effective than passive review methods.

Individual memory strength varies due to factors including age, cognitive ability, stress levels, sleep quality, and personal significance of the material. Teachers can address these variations by helping students make meaningful connections to prior learning, managing classroom stress levels, and emphasising the practical applications of new information. Creating personally relevant contexts for learning significantly improves retention rates across all students.

Teachers can introduce mnemonic devices like acronyms for remembering sequences, such as 'Never eat shredded wheat' for compass directions or 'Richard of York gave battle in vain' for rainbow colours. The memory palace technique, where students associate information with vivid locations in a familiar setting, can also be highly effective. These encoding strategies make information easier to retrieve and naturally flatten the forgetting curve.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into ebbinghaus forgetting curve and its application in educational settings.

A comparative analysis of traditional versus e-learning teaching strategies 84 citations (Author, Year) explores the effectiveness of digital learning approaches compared to conventional classroom methods, examining student engagement, learning outcomes, and pedagogical implications across different educational contexts.

Tularam et al. (2018)

This paper compares traditional lecture-based teaching methods with modern e-learning approaches, examining how different instructional strategies affect student engagement and learning outcomes. For teachers interested in the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve, this research is relevant because it explores how interactive digital learning methods might help combat memory decay by providing more engaging and memorable learning experiences than passive traditional instruction.

Barriers and Facilitators to Teachers’ Use of Behavioral Classroom Interventions 26 citations

Lawson et al. (2022)

This study investigates what prevents or encourages teachers from implementing behavioral classroom interventions, particularly for students with ADHD or behavioral challenges. The research connects to the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve by highlighting how consistent implementation of behavioral strategies is crucial for long-term retention, as inconsistent or infrequent use of interventions leads to faster forgetting of desired behaviours and academic content.

The impact of an interactive digital learning module on students’ academic performance and memory retention 15 citations

Tarigan et al. (2023)

This research examines how interactive digital learning modules affect student academic performance and memory retention compared to traditional electronic learning methods. The study directly relates to the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve by providing empirical evidence on how interactive digital toolscan slow memory decay and improve information retention over time.

Undergraduate Biology Instructors Still Use Mostly Teacher-Centered Discourse Even When Teaching with Active Learning Strategies 22 citations

Kranzfelder et al. (2020)

This study reveals that biology instructors continue to use teacher-centered communication patterns even when implementing active learning strategies in their classrooms. For educators concerned with memory retention and the forgetting curve, this research suggests that simply adopting active learning techniques may not be enough if the underlying discourse remains passive, potentially limiting the memory-enhancing benefits of student engagement.

Happy Together? On the Relationship Between Research on Retrieval Practice and Generative LearningUsing the Case of Follow-Up Learning Tasks View study ↗30 citations

Roelle et al. (2023)

This paper explores the relationship between retrieval practice and generative learning activities, examining how they work together to support both memory consolidation and the construction of coherent mental representations. The research is highly relevant to understanding the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve because it demonstrates how retrieval practice specifically helps consolidate information in memory, directly addressing the memory decay that Ebbinghaus documented in his forgetting curve research.

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve is a fundamental concept in the psychology of memory, developed by Hermann Ebbinghaus in the late 19th century. It provides a visual representation of how quickly information fades from our memory over time if it is not actively reinforced.

The curve illustrates that memory retention drops sharply within the first few hours after learning, often dramatically so due to working memory decay. This decline is not linear; instead, it follows an exponential pattern, with rapid initial forgetting that eventually slows down over subsequent days. This phenomenon underscores the critical role of timely review and reinforcement to counteract the natural forgetting process.

For educators, understanding the dynamics of this curve is key to designing effective teaching strategies that help students retain information more effectively. By recognising when memory loss is most pronounced, teachers can implement timely interventions, such as spaced repetition and active recall, that maximise retention and deepen learning.

In this article, we will explore the theoretical foundations of the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve, discuss how it can be practically applied in educational contexts, and offer strategies to help combat forgetting in the classroom.

Key Insights:

The forgetting curve shows that we forget the majority of new information soon after it is initially learnt. Ebbinghaus defined forgetting as an ability to recall information in the absence of any cues.

Our ability to recognise new information does not follow the same pattern; being presented with cues or multiple-choice options increases the accuracy of our memory.

While the curve describes a general trend to forget new information when there is no attempt to retain it, there will be individual variations in the shape of the curve.

New information that is of significant value, is related to a major event, or offers a surprising contradiction to previously learnt material, is less likely to be forgotten at such a rapid rate.

Time has the greatest impact on the decline of memory; memory retention over time is very poor in the absence of any attempt to retain the new information. The total amount of information that is forgotten increases with time, but the majority of this happens soon after learning has occurred.

The quality of learning also has a significant impact on whether the new material will be resistant to the steep decline in memory observed by Ebbinghaus. Information that is fully understood or deeply processed is likely to be forgotten less quickly.

Similarly, if the new information is of personal significance or has a practical application, it is more likely to be remembered well, partly because the person is more motivated to encode it effectively into their long-term memory.

When new information is similar or related to prior learning, it can impact the decline in memory in both directions.

Retention increases if new knowledge is assimilated into a pre-existing schema of related information in the long-term memory because the prior learning offers an abundance of cues for the new information.

However, when information is similar but unrelated to something that has been previously learnt it can increase the decline in memory for the new information (proactive interference) or the previously learnt information (retroactive interference).

Both types of interference can be seen when learning a new foreign language; words from a previously learnt foreign language may be forgotten when the new language is learnt (retroactive) or it can be more difficult to learn new vocabulary if it is too similar to the previously learnt vocabulary.

There will be individual differences in memory strength, even for nonsense syllables (three-letter ‘words’ that have no meaning). Some of the reasons for this variation include:

Teachers can combat the forgetting curve through three evidence-based strategies: implementing spaced repetition by reviewing material at increasing intervals, using active recall techniques like frequent low-stakes quizzing, and creating meaningful connections between new information and students' prior knowledge. Research shows that reviewing material within 24 hours can increase retention by up to 80%, while combining these techniques can help students retain information for months or even years.

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve describes the decline in memory when there is no attempt to retain the new information. Any strategy that is designed to increase retention will challenge the decline in memory and flatten the forgetting curve.

Repeated Retrieval Practice

The most effective way to challenge the forgetting curve is through repeated retrieval practice. The first attempt to retrieve the new information should be soon after it was originally learnt, with subsequent retrievals becoming increasingly spread out over longer time periods (spaced repetition).

Each successful retrieval increases the number of cues associated with the information, which flattens the forgetting curve and makes it possible to extend the length of time between future retrievals.

Techniques to Improve Memory

Developing techniques to improve memory will reduce the rate of forgetting, even in the absence of any further attempts to retain the new information.

Mnemonic devices focus on encoding new information in a way that will make it easier to retrieve it in the future. Using acronyms can be very successful when it is necessary to learn the order of a list of words:

Never eat shredded wheat: the clockwise order of the compass points (North, East, South, West).

Richard of York gave battle in vain: the order of colours in a rainbow.

Another popular technique is creating a memory palace. This involves developing a mental image of a real or imaginary location, often a house or palace, that has vivid and distinct locations throughout it.

When trying to memorise a list of words, images, or facts, each one is associated with one of the locations in a vivid or meaningful way. Visualising the memory palace then acts as a prompt to remember the new material.

Memory Prompts During Learning

Having an awareness of memory prompts and incorporating them into the learning process will make it easier to recall the newly learnt information at a later date and slow down the steep decline in memory.

Linking new information to prior learning is one of the most effective ways to achieve this; incorporating the new material into a pre-existing schema will allow it to benefit from all of the existing memory prompts and cues that are already in place.

Alternatively, consider using physical cues or the environment as a memory prompt. For example, writing key terms in a different colour pen, in capital letters, or in a certain position on a piece of paper can act as a memory prompt during subsequent recall attempts.

It can also help to learn new material in the same, or similar, environment to where it will need to be recalled; revising in an exam hall in silence would be more effective than revising in a bedroom with music.

The forgetting curve reveals that without review, students lose up to 70% of new information within 24 hours, making immediate and systematic review essential for effective teaching. Teachers should structure lessons to include brief reviews at the start of each class, schedule spaced practice sessions throughout units, and design homework that reinforces rather than introduces concepts. This understanding transforms lesson planning from linear progression to cyclical reinforcement patterns.

Understanding how students forget can allow teachers to make changes to their practice to challenge the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve and increase their students’ memory retention. The following approaches are recommended to teachers in response to Ebbinghaus’ research:

1. Regular Retrieval Practice

Repeated exposure to information strengthens memory retention and flattens the forgetting curve. Asking students to retrieve information forces them to revisit the information, even if they recall it incorrectly, due to the corrective feedback that they receive.

The first retrieval practice should be soon after the new material has been learnt, preferably the following day or in the next lesson. The period of time between each subsequent retrieval should be longer than the previous one. Using spaced intervals are also recommended in Rosenshine’s principles of instruction:

It is better to interleave two or more topics together during retrieval practice; this allows the material to be revisited more often and spaced practice to be spread out over time.

2. Review Schemes of Work

Schemes of work should be reviewed to ensure they include regular opportunities for spaced retrieval practice and that topics are arranged by increasing level of difficulty to build on prior learning.

Curriculumplans should be designed to promote mastery by using scaffolding and dividing complex information into smaller and more manageable chunks.

By reducing the volume of new material that students need to learn in each part of the lesson, they are more likely to encode it effectively into their long-term memories.

Lesson plans should make the links to prior learning explicit to students as this will help them assimilate the new information into a pre-existing schema.

It is also helpful to list the keywords and related keywords for each topic as this will help students to reorganise the new information, provide more cues to aid recall, and allow them to make links between related topics.

Promote Metacognition

Encourage students to reflect on what they have learned, but also how they learned it. This will help students to understand which strategies are most effective at improving memory retention.

This is particularly important after a test or assessment, and part of the teacher’s feedback should be focussed on the effectiveness of the revision strategies and processes that the student used.

Being able to accurately recall information gives students a distinct advantage in our current educational system and is a precursor to being able to effectively manipulate and evaluate that information.

Practising active recall strategies and using memory-enhancing techniques as often as possible will challenge the decline in memory that occurs in the absence of retrieval attempts and memory retention strategies.

Active recall requires students to access information from their long-term memory in the absence of any memory cues or prompts.

A brain dump is one of the most simple and effective ways to achieve this. It involves writing down everything the student can remember about a given topic within a specified time frame.

There are no restrictions or demands about what information can be recalled, which means that students will often also benefit from hearing what their peers have been able to recall. Answering practice questions, defining or generating a list of keywords, or completing an assessment are other useful examples of active recall.

Activities that involve passive recall are much less effective at improving memory. These include:

Summarising a page of text or using flashcards can be classified as being either active or passive recall depending on how each task is approached.

Summarising a page of text is a passive recall activity if the page of text is available throughout the task. However, it becomes an active recall activity if the student reads the text, puts it away, and then writes a summary from memory.

The latter approach should be used for answering practice questions; always read the text and hide it before attempting to answer a question about it.

Using flashcards to aid revision by reading the question and then turning over to ‘confirm’ you know what the answer was involves passive recall at best. However, writing down the answer or answering the question out loud before turning over the card to check the answer would be an example of active recall.

Mnemonic techniques are an effective way to boost memory, especially when it is necessary to remember a list of words in order. Students may also benefit from using dual codingto memorise key words or definitions; this involves pairing the new material with a particularly vivid image to make it more memorable.

While groundbreaking, Ebbinghaus's original research used nonsense syllables rather than meaningful content, which may not accurately reflect how students learn complex subject matter with personal relevance. The curve also doesn't account for individual differences in learning styles, prior knowledge, or emotional connections to material, all of which can significantly impact retention rates. Modern research suggests that meaningful, contextualized learning can create much flatter forgetting curves than Ebbinghaus originally documented.

While the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve has been a foundational concept in understanding how memory retention declines over time, recognise its limitations. The original research conducted by Hermann Ebbinghaus focused on memorizing nonsensical syllables in a controlled environment, which is far removed from the complexity of real-world learning. Therefore, while the Forgetting Curve provides useful insights into the general pattern of memory loss, several limitations should be acknowledged to apply this theory effectively to different learning contexts. Below, we discuss five potential limitations of Ebbinghaus's theory.

By understanding these limitations, educators can more effectively apply and adapt Ebbinghaus's insights to various learning scenarios, allowing for improved methods to enhance long-term memory retention.

Teachers can deepen their understanding through Hermann Ebbinghaus's original work 'Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology' (1885) and modern applications in books like 'Make It Stick' by Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel. Educational psychology journals regularly publish studies on spaced repetition and memory retention, while organisations like the Learning Scientists provide free, research-based resources for classroom implementation. Many teacher training programs now include modules on cognitive science and memory research.

Subsequent research has supported the concept of an exponential forgetting curve and the conclusions that can be drawn from Ebbinghaus’ research to challenge the decline in memory have been shown to effectively improve memory in real-life settings. To learn more about these studies and the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve, please use the links below.

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve is a visual representation showing how quickly information fades from memory over time without active reinforcement. It demonstrates that memory retention drops sharply within the first few hours after learning, with students potentially losing up to 80% of information. Understanding this curve helps teachers implement timely interventions to maximise student retention and design more effective teaching strategies.

The most critical period is within the first two hours after learning, when the sharpest decline in memory occurs. Research shows that reviewing material within 24 hours can increase retention by up to 80%. This makes immediate review after lessons essential rather than optional for preventing massive information loss.

Teachers should schedule the first retrieval practice soon after initial learning, then gradually increase the intervals between subsequent reviews. Each successful retrieval strengthens memory and allows for longer gaps between future practice sessions. This approach flattens the forgetting curve and helps students retain information for months or even years.

Teachers can transform classroom environments into memory aids by using coloured pens, strategic seating arrangements, and wall displays as retrieval cues. They should also connect new content to students' personal experiences and prior knowledge, as information with personal significance creates stronger memory resistance. Low-stakes quizzing and active recall techniques are more effective than passive review methods.

Individual memory strength varies due to factors including age, cognitive ability, stress levels, sleep quality, and personal significance of the material. Teachers can address these variations by helping students make meaningful connections to prior learning, managing classroom stress levels, and emphasising the practical applications of new information. Creating personally relevant contexts for learning significantly improves retention rates across all students.

Teachers can introduce mnemonic devices like acronyms for remembering sequences, such as 'Never eat shredded wheat' for compass directions or 'Richard of York gave battle in vain' for rainbow colours. The memory palace technique, where students associate information with vivid locations in a familiar setting, can also be highly effective. These encoding strategies make information easier to retrieve and naturally flatten the forgetting curve.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into ebbinghaus forgetting curve and its application in educational settings.

A comparative analysis of traditional versus e-learning teaching strategies 84 citations (Author, Year) explores the effectiveness of digital learning approaches compared to conventional classroom methods, examining student engagement, learning outcomes, and pedagogical implications across different educational contexts.

Tularam et al. (2018)

This paper compares traditional lecture-based teaching methods with modern e-learning approaches, examining how different instructional strategies affect student engagement and learning outcomes. For teachers interested in the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve, this research is relevant because it explores how interactive digital learning methods might help combat memory decay by providing more engaging and memorable learning experiences than passive traditional instruction.

Barriers and Facilitators to Teachers’ Use of Behavioral Classroom Interventions 26 citations

Lawson et al. (2022)

This study investigates what prevents or encourages teachers from implementing behavioral classroom interventions, particularly for students with ADHD or behavioral challenges. The research connects to the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve by highlighting how consistent implementation of behavioral strategies is crucial for long-term retention, as inconsistent or infrequent use of interventions leads to faster forgetting of desired behaviours and academic content.

The impact of an interactive digital learning module on students’ academic performance and memory retention 15 citations

Tarigan et al. (2023)

This research examines how interactive digital learning modules affect student academic performance and memory retention compared to traditional electronic learning methods. The study directly relates to the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve by providing empirical evidence on how interactive digital toolscan slow memory decay and improve information retention over time.

Undergraduate Biology Instructors Still Use Mostly Teacher-Centered Discourse Even When Teaching with Active Learning Strategies 22 citations

Kranzfelder et al. (2020)

This study reveals that biology instructors continue to use teacher-centered communication patterns even when implementing active learning strategies in their classrooms. For educators concerned with memory retention and the forgetting curve, this research suggests that simply adopting active learning techniques may not be enough if the underlying discourse remains passive, potentially limiting the memory-enhancing benefits of student engagement.

Happy Together? On the Relationship Between Research on Retrieval Practice and Generative LearningUsing the Case of Follow-Up Learning Tasks View study ↗30 citations

Roelle et al. (2023)

This paper explores the relationship between retrieval practice and generative learning activities, examining how they work together to support both memory consolidation and the construction of coherent mental representations. The research is highly relevant to understanding the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve because it demonstrates how retrieval practice specifically helps consolidate information in memory, directly addressing the memory decay that Ebbinghaus documented in his forgetting curve research.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/ebbinghaus-forgetting-curve#article","headline":"Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve","description":"Unlock the secrets of memory retention with the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve. Explore its implications for educators and learn strategies to improve learning.","datePublished":"2023-10-30T15:08:42.685Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/ebbinghaus-forgetting-curve"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69518c41b910a03f742964c0_69518c3f42d1b48d20cf82de_ebbinghaus-forgetting-curve-infographic.webp","wordCount":3451},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/ebbinghaus-forgetting-curve#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/ebbinghaus-forgetting-curve"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/ebbinghaus-forgetting-curve#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve and why is it important for educators?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve is a visual representation showing how quickly information fades from memory over time without active reinforcement. It demonstrates that memory retention drops sharply within the first few hours after learning, with students potentially losing up to 80% of informatio"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"When is the most critical time to review material with students according to the forgetting curve?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The most critical period is within the first two hours after learning, when the sharpest decline in memory occurs. Research shows that reviewing material within 24 hours can increase retention by up to 80%. This makes immediate review after lessons essential rather than optional for preventing massi"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers implement spaced repetition effectively in their classroom practice?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers should schedule the first retrieval practice soon after initial learning, then gradually increase the intervals between subsequent reviews. Each successful retrieval strengthens memory and allows for longer gaps between future practice sessions. This approach flattens the forgetting curve a"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What practical strategies can educators use beyond traditional revision to combat forgetting?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can transform"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why do some students remember information better than others, and how can teachers account for these differences?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Individual memory strength varies due to factors including age, cognitive ability, stress levels, sleep quality, and personal significance of the material. Teachers can address these variations by helping students make meaningful connections to prior learning, managing classroom stress levels, and e"}}]}]}